Abstract

Defective interfering (DI) RNAs of tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV) are small, subgenomic, helper-dependent replicons that are believed to be generated primarily by aberrant events during replication of the plus-sense RNA genome. Prototypical TBSV DI RNAs contain four noncontiguous segments (regions I through IV) derived from the 5′ nontranslated region (NTR) (I), an internal section (II), and the 3′-terminal portion (III and IV) of the viral genome. We have studied the formation of these molecules by using engineered precursor DI RNA transcripts and report here the consistent accumulation of a novel defective RNA species, designated RNA B. Northern blot, primer extension, and sequence analyses indicated that, unlike prototypical DI RNAs, RNA B lacks region I. In vitro transcripts corresponding to the region II-III-IV structure of RNA B were amplified when coinoculated with helper, indicating that the 5′ NTR of the genome does not harbor cis-acting replication elements essential for viral RNA replication. Region I is, however, important for DI RNA fitness, since molecules lacking it accumulated to significantly lower levels (∼10-fold reduction). Analysis of the minus-strand sequence of region I led to the identification of an RNA undecamer sequence, arranged in tandem, at its very 3′ terminus. Additional variants of the undecamer motif were also identified at internal positions in region I and in the negative strands of regions II, III, and IV. Features of the undecamer motif, the consensus of which is (−)3′-CCCAAAGAGAG, are consistent with a role as a cis-acting replication element. It is proposed that the ability of RNA B to be amplified is due, in part, to compensatory effects of a strategically positioned undecamer motif in region II. Possible replicase-mediated mechanisms for the generation of this novel viral RNA are also presented.

Genome replication for plus-sense RNA viruses involves the synthesis of a complementary minus-sense RNA which serves as a template for the production of additional copies of the genome. This two-step process is generally asymmetrical, showing differences in both the kinetics and absolute levels of accumulation of plus- and minus-sense strands (14, 22). Promoter elements have been identified in both the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of plus-sense RNA viral genomes (5, 7, 9, 21, 27, 37), and RNA signals involved in the synthesis of minus strands have been studied extensively (5, 9, 21, 36, 41). Much less is known about the mechanisms of plus-strand synthesis or the cis elements necessary for this process to occur. However, various mutations in the 5′ nontranslated regions (NTRs) or 5′-terminal regions of different viral RNAs lead to defects in replication specific for plus-strand synthesis (1, 8, 16, 30).

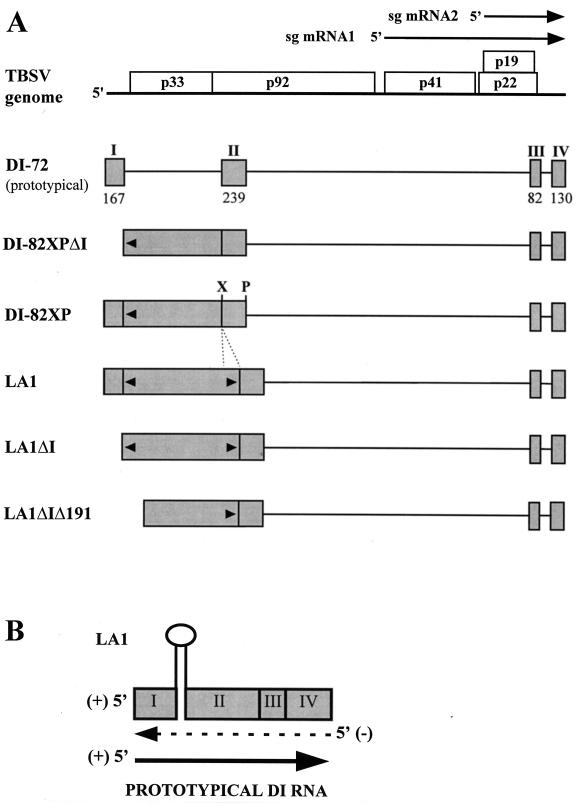

Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV), a small plus-sense RNA virus, is the prototype member of the genus Tombusvirus in the family Tombusviridae. Its 4.8-kb genome is neither capped nor polyadenylated, and it encodes five functional open reading frames (ORFs) (12). The 5′-proximal ORFs encode the viral components (p33, p92) required for genome replication (Fig. 1A) (26, 35), and these products are translated directly from the genome. The ORFs located more 3′ in the genome encode the coat protein (p41) and movement proteins (p19, p22) (34) that are translated from two subgenomic (sg) mRNAs (Fig. 1A) (12). In addition to legitimate sg mRNAs, defective interfering (DI) RNAs have been identified in TBSV infections (13). These molecules maintain cis-acting promoter elements which make them useful for studies on viral RNA replication (4, 10, 33a). For TBSV and other members of the genus Tombusvirus, prototypical DI RNAs contain four noncontiguous segments (regions I through IV) derived from the 5′ NTR (I), an internal segment within the ORF encoding p92 (II), and 3′-terminal segments (III and IV) of the viral genome (Fig. 1A) (2, 17, 32). Previous studies on prototypical tombusvirus DI RNAs suggested that regions I, II, and IV are essential for viability (4, 10). The requirement for region III was less clear; for cymbidium ringspot tombusvirus, this region appeared to be essential for DI RNA accumulation (10), whereas for TBSV and cucumber necrosis tombusvirus (CNV) it was dispensable (4).

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the TBSV RNA genome and various defective viral RNAs. The wild-type TBSV genome is shown at the top as a thick horizontal line, with coding regions depicted as open boxes and the approximate molecular weights (in thousands) of the encoded proteins indicated (12). The regions corresponding to the two sg mRNAs are shown as arrows above the genome. Below, a prototypical DI RNA and various precursor DI RNAs are depicted, with shaded boxes representing regions of the genome retained in these molecules and thin lines corresponding to segments which are absent. DI-72 is composed of four noncontiguous regions (I through IV), the lengths of which are indicated (in nucleotides) (43). Various artificially constructed precursor DI RNAs are shown below DI-72, and the positions of engineered XbaI (X) and PstI (P) sites in DI-82XP are indicated. The rightward-pointing arrowheads in LA1 and its derivatives represent the inserted 191-nt segment, which is complementary to an existing upstream sequence (leftward-pointing arrowhead). (B) Proposed replicase-mediated model for generation of prototypical DI RNAs from precursor LA1 containing complementary segments (note: the stem-loop structure depicted is not to scale) (45). During minus-strand synthesis (broken arrow) the replicase is able to traverse the base of the strong secondary structure and resume copying on the other side. Synthesis of a complementary plus strand (solid arrow) generates a prototypical DI RNA.

DI RNAs are thought to be generated by aberrant RNA synthesis by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDRP), resulting in the introduction of deletions into nascent RNA strands (19, 28). In TBSV, this process has been studied in some detail by analyzing precursor DI RNAs in which the segment normally absent between regions I and II in a prototypical DI RNA was reintroduced (Fig. 1A) (43, 45). When protoplasts are coinoculated with helper genome and a precursor DI RNA, prototypical DI RNAs are generated from the precursor via internal deletion of the reintroduced segment. This system was used previously to show that complementary segments in precursors can facilitate the targeting of junction sites to the base of the secondary structure that is predicted to form (Fig. 1B) (45).

In the present study, we have identified and characterized a novel TBSV defective RNA species, RNA B, which was generated from various precursor DI RNAs. The absence of region I in these molecules indicates that, despite its invariable presence in prototypical DI RNAs, the 5′ NTR is not essential for viral RNA replication. An RNA sequence undecamer motif, present in multiple copies in region I, was also identified in regions II, III, and IV. Possible roles for these elements in the context of prototypical DI RNAs and RNA B are discussed, and likely mechanisms for the generation of RNA B are described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral and DI RNA constructs.

Plasmid construct K2/M5, containing cDNA corresponding to the full-length viral genome of CNV, has been described previously (33). DI-72XP, DI-82XP, and LA1 [previously termed DI-82XP-191(−)] have been described previously (43, 45). The following oligonucleotides were used in this study (underlined residues correspond to nonviral sequence, whereas those not underlined correspond to viral sequence): P9, 5′-GGCGGCCCGCATGCCCGGGCTGCATTTCTGCAATGTTCC (TBSV, minus sense, 4754 to 4776); P45, 5′-GGCCTCTAGAGAGAATGATTTGGCCTAAGAAAGAG (TBSV, plus sense, 180 to 204); P46, 5′-GGCCGGCCGGCTAGCCAGCACAATCAGTTTTGAGTAATTC (TBSV, minus sense, 346 to 370); PF7, 5′-GGCGGAGCTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAAATTCTCCAGGATTTC TC (TBSV, plus sense, 1 to 20); PB1, 5′-ACTGTCCTAGCTAGCCCGGTTGCGAAATCACCCA (TBSV, minus sense, 211 to 245); PB2, 5′-TCATGTATCGCTAGCCCACACGACACACCAATTG (TBSV, minus sense, 262 to 295); PB19, 5′-CCAAAGGCTCCTTTGGTAGGTTGTGGAGTG (TBSV, minus sense, 1305 to 1334); PB20, 5′-CGCTTGTTTGTTGGAAGTTACAATTTATCC (TBSV, minus sense, 134 to 163); PB21, 5′-GAACTAGGTCGAGAAATCCTGGAGAATTTC (TBSV, minus sense, 1 to 30); PB22, 5′-AACCTTCTCACAAACCGCTTTCCTGAACGG (TBSV, minus sense, 1345 to 1374); PB23, 5′ - CGGCGGAGCTC TAATACGAC TCAC TATAGAGAATGAT T TGGCC TAAGAAAGAG (TBSV, plus sense, 180 to 204); PB24, 5′-GGCTCAACCACCAGACAATCTG (TBSV, minus sense, 701 to 722); PB25, 5′-CGGCGGAGCTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAAGAAACGGGAAGCTCGCTC (TBSV, plus sense, 1285 to 1303); PB26, 5′-CGGCGGAGCTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAAACGGGAAGCTCGCTCGC (TBSV, plus sense, 1286 to 1305); PB27, 5′-CGGCGGAGCTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAACCGGGAAGCTCGCTCGC (TBSV, plus sense, 1286 to 1305, [1289, A to C]); PB31, 5′-CGGCGGAGCTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGCCAAATGGGAATGGTTCATG (TBSV, plus sense, 370 to 390).

Plasmid construction.

Viral constructs were created by a combination of PCR- and restriction enzyme-based methods. The following PCR products were generated with the specified oligonucleotide pairs and templates, respectively: PCR 1, PF7/P46 and LA1; PCR 2, P46/P9 and LA1; PCR 3, P45/PB1 and DI-82XP; PCR 4, P45/PB2 and DI-82XP; PCR 5, PF7/PB2 and L6(−); PCR 6, PB2/P9 and L6(−); PCR 7, PF7/PB1 and L5(−); PCR 8, PB1/P9 and L5(−). The uses of these products are described below.

To construct L6(−), the PCR 3 product was digested with XbaI and NheI and inserted into the XbaI site of DI-82XP in the opposite orientation. To construct L5(−), the PCR 4 product was digested with XbaI and NheI and inserted into the XbaI site of DI-82XP in the opposite orientation. To construct L1, a 339-bp fragment was removed from LA1 by digestion with NaeI and StuI, and the large fragment was isolated from an agarose gel and self-ligated. To construct L2, LA1 was digested with NaeI and SphI, and the smaller fragment was excised and replaced with the SphI-digested PCR 2 product. To construct L3, LA1 was digested with SacI and StuI, and the smaller fragment was excised and replaced with the SacI-digested PCR 1 product. L7, L9, and L8 and L11, L13, and L12 were generated as described for the construction of L1 through L3 except that L6(−) and L5(−), respectively, were used as the recipients of the PCR products. A summary of the structures of the resulting viral constructs is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Relevant structural features of selected precursor DI RNAs

| Seta | Precursor DI RNA | Predicted complementary segment (nt) | Predicted intervening sequence (nt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | LA1 | 191 | 920 |

| L1 | 191 | 581 | |

| L2 | 191 | 367 | |

| L3 | 191 | 244 | |

| B | L6(−) | 101 | 1,010 |

| L7 | 101 | 671 | |

| L8 | 101 | 244 | |

| L9 | 101 | 457 | |

| C | L5(−) | 45 | 1,066 |

| L11 | 45 | 727 | |

| L12 | 45 | 244 | |

| L13 | 45 | 513 |

Sets A, B, and C correspond to the panels in Fig. 4.

LA1ΔI was generated by PCR amplification of positions 180 to 722 from DI-82XP by using the oligonucleotide pair PB23/PB24. Oligonucleotide PB23 included a SacI site and a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The product was digested with SacI and ligated into SacI/NaeI-digested LA1. LA1ΔIΔ190 was generated by PCR amplification of positions 370 to 722 from DI-82XP by using oligonucleotide pair PB31/PB24. Oligonucleotide PB31 included a SacI site and a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The product was digested with SacI and ligated into SacI/NaeI-digested LA1. DI-82XPΔI was generated by transferring the smaller fragment of SacI/NaeI-digested LA1ΔI into SacI/NaeI-digested DI-82XP.

B1 was generated by PCR amplification of region II through region IV from DI-82XP by using oligonucleotide pair PB25/P9. Oligonucleotide PB25 included a SacI site and a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The PCR product was digested with SacI/BstXI and inserted into SacI/BstXI-digested DI-82XP. B2 was generated by PCR amplification of region II through region IV from DI-82XP by using oligonucleotide PB26 and oligonucleotide P9. Oligonucleotide PB26 included a SacI site and a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The PCR product was digested with SacI/BstXI and inserted into SacI/BstXI-digested DI-82XP. The authenticity of each construct was verified by restriction endonuclease digestion analysis and/or DNA sequencing.

In vitro transcription.

Viral transcripts were generated in vitro via transcription of SmaI-linearized template DNAs with the Ampliscribe T7 RNA polymerase transcription kit (Epicentre Technologies). Following the transcription reaction, DNA templates were removed by treatment with DNase I (Epicentre Technologies), and unincorporated nucleotides were removed via column chromatography with a Sephadex G-25 spin column (Pharmacia). Ammonium acetate was added to the flowthrough to a final concentration of 2 M, and the transcripts were extracted twice with equal volumes of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and then precipitated with ethanol. Subsequently, the transcripts were quantified spectrophotometrically and an aliquot was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis to verify integrity.

Isolation and inoculation of protoplasts.

Protoplasts were prepared from 6- to 8-day-old cucumber cotyledons (var. Straight 8) as described previously (43). Briefly, the lower epidermis of the cotyledons was peeled off with forceps, and the cotyledons were digested in 20 ml of an enzyme mix containing 0.25 g of cellulase (Calbiochem), 0.025 g of pectinase (ICN), and 0.025 g of bovine serum albumin (ICN) for 6 to 8 h with gentle shaking (60 rpm) in the dark. The protoplasts were then washed in 10% mannitol and purified by banding twice on a 20% sucrose cushion. Quantification was carried out by bright-field microscopy with a hemacytometer. Purified protoplasts (approximately 4 × 105) were inoculated with 5 μg of each viral RNA transcript (unless specified otherwise) and were incubated in a growth chamber under fluorescent lighting at 22°C for 24 h.

Analysis of viral RNAs.

Total nucleic acid was harvested from protoplasts at 24 h postinoculation by resuspension in 300 μl of a buffer containing 0.2 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (43). Following two extractions with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, 100 μl of 8 M NH4 acetate was added to the aqueous phase and the mixture was precipitated with ethanol. Aliquots of the total nucleic acid preparation (one-sixth) were separated in 4.5% polyacrylamide gels in the presence of 8 M urea. Viral RNAs were detected by electrophoretic transfer to nylon (Hybond-N; Amersham) followed by Northern blot analysis with 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotides complementary to various segments of the TBSV genome.

Primer extension of viral RNAs.

Approximately 0.2 pmol of 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide PB22 was mixed with an aliquot (one-fourth) of the total nucleic acids extracted from inoculated protoplasts (4 × 105) or with ∼20 ng of gel-purified RNA B. The mixtures, in a volume of 10 μl, were incubated at 90°C for 2 min and then transferred to ambient temperature for 5 min. The extension reaction was carried out in a final volume of 20 μl which included 300 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL), a 1× concentration of the buffer provided by the manufacturer, and a 0.5 mM concentration of each of the four deoxyribonucleotides. The mixture was incubated at 45°C for 40 min, after which the samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and then precipitated with ethanol. The recovered pellets were resuspended in 20 μl of double-distilled H2O, and a 2-μl aliquot was mixed with 2 μl of formamide loading dye and separated in an 8% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 8 M urea. A sequencing ladder was generated with oligonucleotide PB22 and LA1 template, and the products were separated along with those of the primer extension reactions.

Structural analysis of viral RNA transcripts.

Various viral RNA transcripts (5 μg) were digested with 0.1, 1, or 10 units of RNase T1 (Calbiochem) in a final volume of 15 μl of H2O (containing residual NH4 acetate from prior ethanol precipitation) at 37°C for 1.5 h. The products of the reaction were then separated by neutral 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. cDNAs corresponding to RNA B were generated from gel-purified RNA B and amplified by PCR as described previously (43) or by using a 5′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) kit (Life Technologies). The products were subsequently cloned and sequenced.

RESULTS

Accumulation of novel defective viral RNAs from a precursor DI RNA.

Previously, analysis of DI RNA formation with a system utilizing precursor molecules indicated that complementary segments in precursor LA1 (Fig. 1A) can target junction sites to the base of the secondary structure predicted to form between the two segments (Fig. 1B) (45). For these studies, a heterologous genome (CNV-K2/M5) derived from the closely related tombusvirus CNV was used as helper to enable confirmation of the derivation of smaller prototypical DI RNAs (i.e., from the precursor versus from the helper). In this system, accumulation of prototypical DI RNAs was not observed in the initial protoplast infection, but such molecules were detected following a single passage (43, 45). In the present study, we have focused our analyses on small viral RNAs which accumulate during initial infections with helper and precursor LA1.

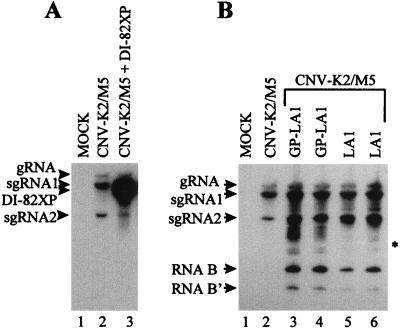

In Fig. 2A, the coinoculation of protoplasts with CNV-K2/M5 and precursor DI-82XP (Fig. 2A, lane 3) resulted in very efficient amplification of the precursor in addition to authentic genomic and subgenomic species (compare Fig. 2A lane 3 with lane 2); however, no readily detectable smaller viral RNAs were observed (Fig. 2A, lane 3), consistent with previous results (43, 45). Inoculations of DI-82XP alone, or individual inoculations of any other precursor DI RNA tested in this study, resulted in no detectable viral RNA accumulation (data not shown). Precursor LA1 is a derivative of DI-82XP in which a 191-nucleotide (nt) segment, which is complementary to an upstream region, was inserted just 5′ to region II (Fig. 1A) (45). The complementary segments in this precursor thus have the potential to participate in a long-distance base-pairing interaction (as depicted in Fig. 1B). When coinoculated with helper, the LA1 precursor did not accumulate significantly, but a prominent low-molecular-weight viral RNA species, designated RNA B, and a less-abundant smaller species, designated RNA B′, were detected (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6). The electrophoretic mobilities of these RNAs were significantly greater than that anticipated for prototypical DI RNAs (Fig. 2B, asterisk). To ensure that these small products were not derived from less-than-full-length precursor transcripts generated during the in vitro transcription reaction, full-length LA1 transcripts were gel purified. Coinoculation of gel-purified LA1 with helper also led to efficient accumulation of RNA B (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of progeny viral RNAs isolated from cucumber protoplasts inoculated with various combinations of viral RNA transcripts. (A) Coinoculation of precursor DI-82XP and CNV-K2/M5 helper transcripts. (B) Coinoculations of precursor LA1 (2 μg [lane 5] or 5 μg [lane 6]), gel-purified LA1 (GP-LA1) (2 μg [lane 3] or 5 μg [lane 4]), and CNV-K2/M5 helper transcripts. The RNA transcripts used in the inoculations are indicated at the top, and the positions of the genome RNA (gRNA), sg mRNAs (sgRNA1 and sgRNA2), and defective RNAs (RNAs B and B′) are shown on the left. The predicted position for prototypical DI RNAs is indicated with an asterisk. Total nucleic acids were isolated from approximately 4 × 105 protoplasts after a 24-h incubation and were separated in a 4.5% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 8 M urea, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with a 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe (P9) complementary to the 3′-terminal 23 nt of the TBSV and CNV genomes.

Accumulation of RNA B is facilitated by the inserted segment and sequence complementarity.

Region I, which corresponds to the 5′ NTR of the genome and is present in all prototypical DI RNAs, has been implicated in viral RNA replication (4, 10). To determine whether region I in precursor LA1 was required for the generation of RNA B, transcripts lacking region I, LA1ΔI (Fig. 1A), were coinoculated with helper into protoplasts. Despite the absence of this region, RNA B accumulated efficiently (Fig. 3A, lane 5). To test whether the potential base-pairing activity of LA1 was a contributing factor in the accumulation of RNA B, a derivative of LA1, LA1ΔIΔ191, which lacked both region I and the upstream segment complementary to the 191-nt insertion, was constructed (Fig. 1A). Coinoculation of LA1ΔIΔ191 and CNV-K2/M5 consistently led to decreased levels of accumulation of RNA B and increased levels of RNA B′ (Fig. 3A, lane 6). Interestingly, this coinoculation also resulted in efficient accumulation of an additional larger RNA product, designated RNA BX.

FIG. 3.

(A) Northern blot analysis of progeny viral RNAs isolated from cucumber protoplasts inoculated with CNV-K2/M5 helper and various precursor DI RNA transcripts. The RNA transcripts used in the inoculations are shown at the top, and the positions of the genome RNA (gRNA), sg mRNAs (sgRNA1 and sgRNA2), and defective RNAs (RNAs B, B′, and BX) are indicated. Total nucleic acids were isolated and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (B) Analysis of products generated from digestion of RNA transcripts of various precursor DI RNAs with RNase T1. The identity of the precursor analyzed is shown at the top, with the total number of units of RNase T1 present in each reaction indicated. HpaII-digested pUC19 is separated in lane M, and the sizes (in base pairs) of relevant fragments are indicated to the left. At right, an asterisk denotes the positions of full-length precursor transcripts and an arrowhead indicates products resistant to digestion. The samples were separated in a nondenaturing 2% agarose gel and then stained with ethidium bromide.

Two differences between DI-82XP and LA1 are evident. First, DI-82XP does not contain the 191-nt insertion present in LA1. Secondly, DI-82XP is amplifiable and accumulates efficiently, whereas LA1 does not. It is possible that one or both of these differences contribute to the absence of detectable RNA B in DI-82XP and helper coinfections (Fig. 2A, lane 3). As suggested by the results from the LA1ΔIΔ191 and helper coinfection, the inserted segment, which is absent in DI-82XP, may possess important properties which allow the generation and/or accumulation of RNA B. Alternatively, or additionally, the poorly amplifying LA1 may compete weakly for trans-acting replication factors, and this may in turn allow efficient accumulation of other less-competitive defective RNA species (e.g., RNA B). Thus, the lack of RNA B accumulation in DI-82XP and helper coinoculations may be the consequence of competitive suppression by the efficiently replicating precursor. To address this possibility, an accumulation-defective derivative of DI-82XP, DI-82XPΔI (Fig. 1A), was tested. Only very low levels of RNA B- and B′-sized species were detected in coinoculations with CNV-M2/K5 (Fig. 3A, lane 3).

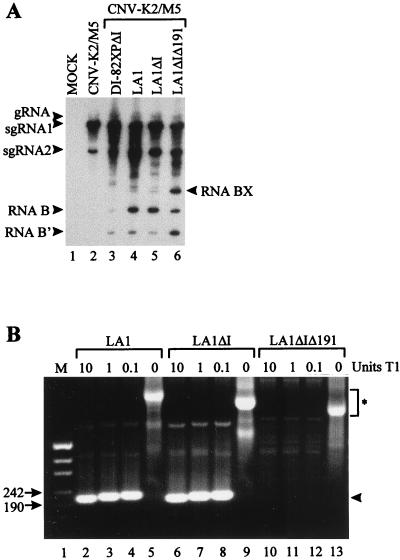

Our results suggest that sequence complementarity facilitates accumulation of RNA B. The ability of LA1 or LA1ΔI to form a stable stem structure was confirmed by subjecting in vitro-generated transcripts of these precursors to digestion with single-strand-specific RNase T1. For both LA1 and LA1ΔI, an approximately 191-bp nuclease-resistant fragment was generated, which was not observed for digestion of LA1ΔIΔ191, which lacks the upstream complementary segment (Fig. 3B). To test for possible limitations of RNA B accumulation due to the length and/or spacing of the complementary sequences, numerous derivatives of LA1 in which these structural features were varied were constructed (Table 1). Complementary segments of 191, 101, and 45 nt were tested in combination with various lengths of intervening sequences. In all cases, coinoculation of the various precursor DI RNAs with the helper led to efficient accumulation of RNA B but, interestingly, no significant accumulation of any precursor was observed (Fig. 4). This result indicates a significant degree of flexibility in the process leading to RNA B formation and/or amplification with respect to the structural parameters tested. The ability of selected precursors, with complementary segments of 101 or 45 nt, to form the predicted secondary structures was confirmed via digestion with RNase T1 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of progeny viral RNAs isolated from cucumber protoplasts coinoculated with helper and precursor DI RNA transcripts containing different-sized complementary segments and intervening sequences. See Table 1 for additional information on the structures of the precursors. The RNA transcripts used in the inoculations are indicated at the top, and the positions of the genome RNA (gRNA), sg mRNAs (sgRNA1 and sgRNA2), and RNA B are shown on the left. Total nucleic acids were isolated and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

Analysis of RNA B structure.

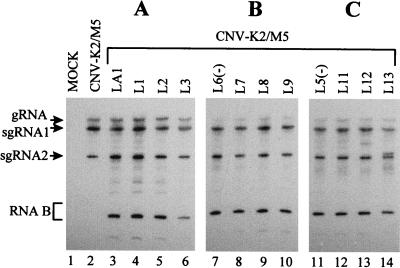

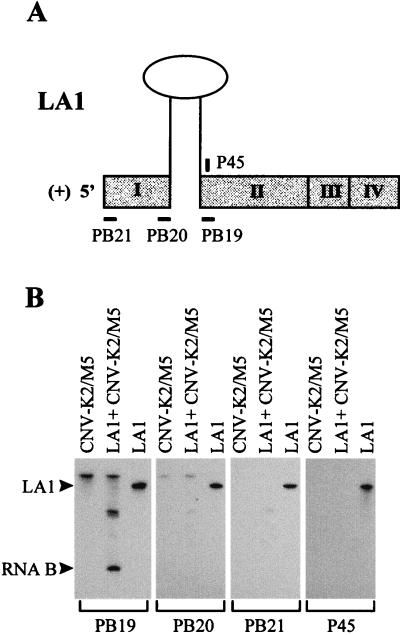

The accumulation of RNA B only in coinoculations which included precursor DI RNAs indicated that its production was dependent on the precursors and that the small RNA species was likely derived from them. Northern blot analyses with a 3′ terminus-specific probe established that RNA B contained a 3′ terminus analogous to that of LA1 (Fig. 2 through 4). To determine further the general structure of RNA B, oligonucleotides complementary to various regions of LA1 were used as probes for Northern blot analyses (Fig. 5A). Oligonucleotides PB21 and PB20, complementary to 5′ and 3′ segments in region I, respectively, did not hybridize to RNA B but did hybridize efficiently to in vitro-generated transcripts of LA1 (Fig. 5B). Oligonucleotide PB19, complementary to a 5′ section in region II, but not oligonucleotide P45, complementary to a 3′ segment of the 191-nt insert, hybridized to RNA B (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that RNA B does not contain region I and possesses a 5′ terminus which maps between the sites complementary to oligonucleotides PB19 and P45.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the structure of RNA B. (A) Schematic representation of LA1, with the relative positions of various complementary oligodeoxyribonucleotides indicated (note: the stem-loop structure depicted is not to scale). (B) Northern blot analysis of progeny viral RNAs isolated from cucumber protoplasts coinoculated with helper and precursor LA1. The RNA transcripts used in the inoculations are indicated at the top, except for lanes labeled LA1, where ∼70 ng of the LA1 transcript was analyzed in the gels. The positions of the LA1 transcripts and RNA B are shown on the left, and the oligonucleotide probes used for detection are indicated at the bottom. Total nucleic acids were isolated and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2 except that blots were hybridized with 32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to various segments of LA1.

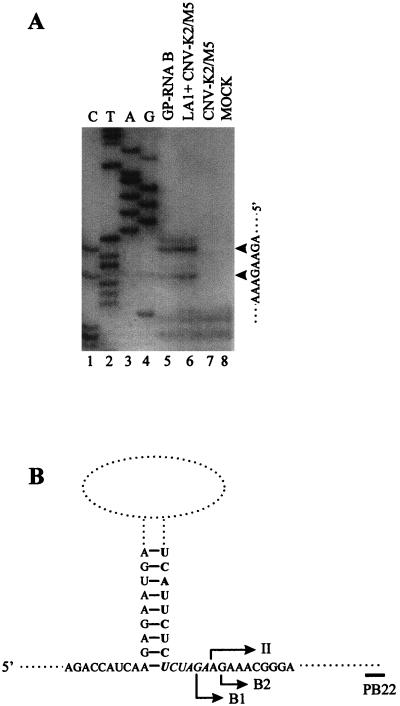

To more precisely map the 5′ terminus of RNA B, primer extension analysis was performed. Extension of a 32P-end-labeled primer (PB22) with total nucleic acids prepared from protoplasts coinoculated with helper and LA1, or gel-purified RNA B, resulted in two major products (Fig. 6A). The predicted termini of the primary products mapped within four residues of each other and indicated 5′-terminal residues containing the base guanine (Fig. 6). The positions of these termini were between the binding sites of PB19 and P45 and are thus consistent with the results obtained from Northern blot analysis (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that RNA B represents a set of structurally related molecules which contain somewhat heterogeneous 5′ termini but which are 3′ coterminal with LA1. Cloning and sequencing of RNA B, via reverse transcription-PCR and 5′ RACE, confirmed the predicted region II-III-IV structure and mapped the 5′ termini, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Mapping of the 5′ termini of RNA B. (A) Primer extension analysis of RNA B. The sources of the nucleic acids which were analyzed by primer extension are identified above lanes 5 to 8, and the corresponding sequencing ladder of LA1 is identified above lanes 1 to 4. Major termination sites, along with their corresponding positions in the plus-strand sequence, are indicated on the right by arrowheads. Products were separated in an 8% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 8 M urea. (B) Schematic representation of an internal segment of LA1 showing the relative positions of the mapped 5′ termini of RNA B. The arrows below the sequence indicate the predicted 5′ termini, whereas the arrow above the sequence defines the 5′ terminus of region II. Sequence corresponding to the 3′-terminal region of the inserted 191-nt segment is in boldface type, and the engineered XbaI site is italicized. The relative position of oligonucleotide PB22, used for primer extension analysis, is indicated.

Replication and accumulation kinetics of RNA B.

Our results indicate that RNA B is generated from different precursors. Various mechanisms might account for its generation from these molecules. For example, its formation may be replicase mediated, whereby a minus strand corresponding to LA1 serves as the template for its production. Alternatively, RNA B may be generated directly from the input LA1 transcript via endoribonucleolytic activity. To determine if the accumulating RNA B represented a stable degradation product of the input precursor DI RNAs, a time course experiment was performed. In coinoculations with helper and either LA1 or LA1ΔI, only trace amounts of the precursors were detected at the zero time point; however, a clear increase in accumulation of RNA B was observed over time (Fig. 7A and B). The limited quantity of precursor detected early in the time course would therefore be insufficient to generate, via nucleolytic cleavage, the significant levels of RNA B which accumulated. To address the question of replicability, transcripts corresponding to the region II-III-IV structures of the two major RNA B species, RNA B1 and RNA B2 (Fig. 6), were synthesized. When coinoculated with CNV-K2/M5, both showed significant increases in levels of accumulation over 24 h (Fig. 7C and D), confirming their capacities to be trans amplified.

FIG. 7.

Northern blot analysis of progeny viral RNAs showing the kinetics of accumulation of RNA B. The RNA transcripts used in the inoculations are indicated at the top, and the positions of the genome RNA (gRNA), sg mRNAs (sgRNA1 and sgRNA2), and RNA B are shown on the left. The times after inoculation at which the nucleic acid samples were isolated are indicated (in hours) above each lane. Total nucleic acids were isolated and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

Genome replication is a central process in the reproductive cycle of plus-sense RNA viruses, and RNA structure is a key determinant of the specificity and efficiency with which viral RDRPs utilize various templates. By analyzing different amplifiable viral RNAs, it is possible to gain insight into the structural features of templates that influence RDRP activity. In this study, we have identified a novel defective viral RNA species, RNA B, and have characterized its structure, biological activity, and some of the properties of its precursors which influence its accumulation. Our results provide clues to possible mechanisms responsible for generating RNA B and reveal valuable information on the cis-acting elements involved in viral RNA replication.

Formation and accumulation of RNA B.

Various properties of the precursor were analyzed to determine their effects on the accumulation of RNA B. The results suggest that (i) region I in the LA1 precursor is not essential for RNA B accumulation, (ii) the 191-nt insert in LA1 and its derivatives facilitate RNA B accumulation, (iii) the positive effect of the inserted segment on RNA B accumulation is stimulated further by the presence of a complementary upstream segment, and (iv) the absence of the complementary upstream sequence facilitates the accumulation of defective RNA species other than RNA B (which remain to be characterized).

The inserted 191-nt segment (in the absence of the complementary upstream sequence) significantly increased RNA B accumulation, most likely by facilitating its formation. Possible mechanisms for its generation include (i) internal initiation of plus-strand synthesis on a minus-strand template, (ii) premature termination of minus-strand RNA synthesis, and/or (iii) cleavage of the precursor RNA. Analysis of the 3′ junction site of the inserted segment revealed partial sequence identity with the predicted sg mRNA 2 promoter (15) (Fig. 8A). Since various sg mRNA promoters have been shown to induce internal initiation of RNA synthesis on minus-strand templates (23, 39, 42), it is possible that this cryptic promoter could function in a similar manner, thereby generating RNA B. Internal initiation of plus-strand synthesis on a minus-strand template has been proposed as the mechanism generating 5′-terminally truncated forms of alfalfa mosaic virus RNA 3 (40); however, sg mRNA promoter-like sequences were not implicated.

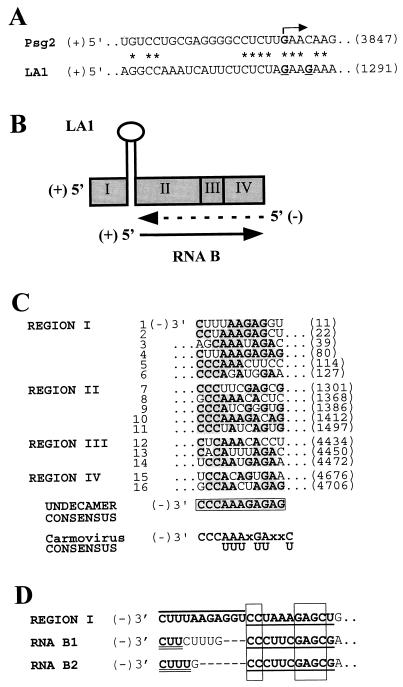

FIG. 8.

(A) Alignment of the predicted sg RNA2 promoter (Psg2) sequence (15) with the sequence in LA1 corresponding to the mapped 5′ termini of RNA B. The termini mapped for the two major RNA B species are in boldface type and underlined in the LA1 sequence, and the initiating nucleotide for sg mRNA2 synthesis (12) is in boldface type and indicated by an arrow. Identical nucleotides between Psg2 and LA1 are indicated by asterisks. The coordinates of the 3′-most residues in the sequences are shown in parentheses to the right and correspond to the numbering of the TBSV genome (12). (B) Replicase-mediated mechanism proposed to explain how secondary structure could facilitate the generation of RNA B from precursor LA1 (note: the stem-loop structure depicted is not to scale). Synthesis of a minus strand (broken arrow) complementary to LA1 is stalled at the strong secondary structure. The prematurely terminated minus strand is then copied to generate RNA B (solid arrow), which is amplified further via replication. (C) Alignment of selected conserved undecamer sequences present in the minus strand of DI-72 (Fig. 1), a prototypical TBSV DI RNA (43). The DI RNA regions from which the sequences were derived are indicated on the left, and individual sequences are numbered consecutively. The numbers in parentheses on the right indicate the coordinates of the 5′-most residues of the sequences shown and correspond to the numbering of the TBSV genome (12). Residues in sequences 1 through 16 which conform (see below) to the undecamer consensus sequence (boxed) are in boldface type and shaded. The undecamer consensus represents the most prevalent nucleotides at the respective positions. The sequences shown contain a minimum of 6 of the 11 consensus residues. For comparison, the consensus sequence of a carmovirus motif implicated in plus-strand synthesis is also shown (8). (D) 3′-terminal sequences of the minus strands of region I and RNAs B1 and B2. The terminal and adjacent undecamer motifs in the region I sequence are over- and underlined, respectively, and those in RNAs B1 and B2 are underlined. The boxes indicate nucleotides in the more 5′ undecamer in region I which are identical to those in RNAs B1 and B2. Terminal RNA B segments identical to the region I terminus are in boldface type and doubly underlined. Gaps were introduced into the RNA B sequences to maximize the alignment of 3′-terminal nucleotides with identical residues in region I.

The inserted sequence might, in the absence of the upstream complementary segment, promote RNA B formation by facilitating stalling and/or dissociation of the RDRP during minus-strand synthesis. However, no conspicuous sequences and/or structures which might potentially facilitate such a process were identified. The production of RNA B was clearly enhanced when the inserted segment was accompanied by a complementary upstream sequence. Previous studies have provided evidence that strong secondary structures in RNA templates can stall and/or cause the dissociation of an actively copying RDRP (11, 20, 24, 45). It is therefore possible that the facilitatory effect of the secondary structure involves blocking of RDRP movement during minus-strand synthesis (Fig. 8B). This template-mediated pausing might in turn promote dissociation and/or premature termination of minus-strand synthesis and/or initiation of plus-strand synthesis. A mechanism similar to this has been proposed recently for the generation of an sg mRNA of red clover necrotic mosaic virus (35a); however, in that case the potentially obstructive secondary structure was formed between two viral RNAs (i.e., in trans). The positions of the 5′ termini of RNA B are consistent with replicase obstruction, as they are located 4 and 7 nt 3′ to the base of the secondary structure. Following its generation, RNA B might then be amplified further in a precursor-independent fashion. Interestingly, formation of the secondary structure would sequester the inserted sequence into a double-stranded form, thereby limiting its participation in alternate structures. This suggests that the mechanisms of action in the presence or absence of the upstream complementary element may be partially or entirely independent.

It is also possible that initial generation of RNA B involved ribonuclease cleavage of the precursor. Such a mechanism would require that a ribonuclease(s) preferentially acts on LA1 (and its derivatives) but not on DI-82XPΔI. Although this possibility cannot be precluded, we feel that the replicase-mediated mechanisms suggested are more likely applicable.

It has been shown previously that competitive ability plays an important role in both the observed accumulation levels and the evolutionary pathways of DI RNAs (43, 44). For LA1, efficient accumulation of RNA B in the initial infection and its absence after a single passage (data not shown) is contrary to that observed for prototypical DI RNAs (43). One explanation for these reciprocal accumulation profiles is that RNA B is generated from LA1 more efficiently than are prototypical DI RNAs (e.g., the frequency of stalling at the structure exceeds that of bypassing it). As a consequence, RNA B would dominate early (i.e., in the initial infection) but over time (i.e., following a passage) would be outcompeted by the more fit prototypical molecules.

Implications for viral RNA replication.

Our results indicate that insertion of RNA segments with significant base-pairing potential into precursor DI RNAs causes a significant decrease in their viability. Base-paired sections as short as 45 bp, formed by sequences at distant positions, were able to dramatically reduce the accumulation of precursors. It is unlikely that the insertions inactivated essential cis-acting elements, since numerous similarly sized insertions of different sequences at the same site had no deleterious effects on precursor accumulation (46). It appears, therefore, that the ability to form a stable secondary structure may be the primary property exerting a negative influence on precursor accumulation. This effect may result from secondary structure-mediated inhibition of RNA replication in a manner akin to that depicted in Fig. 8B (i.e., blocking of replicase movement). However, other mechanisms which are unrelated to secondary structure (e.g., the inserted sequence is itself inhibitory) or which involve an indirect role for secondary structure (e.g., by binding an inhibitory protein factor) are also possible.

The replication of RNA B, which lacks the entire 5′ NTR of the genome, is significant since 5′-terminal segments are important or essential for genome replication and/or viability in numerous plus-sense RNA plant and animal viruses (7, 16, 25, 27, 30, 40). Interestingly, entire 3′ NTRs of picornavirus genomes can be deleted while viability is maintained (38). This result is notable, since these regions have been shown to harbor cis-acting elements important for genome replication (29, 31). Despite the apparent dispensability of the TBSV 5′ NTR for replication, its absence did lead to decreased levels of accumulation of the viral replicon (i.e., RNA B accumulated to levels of approximately 1 order of magnitude less than that of DI-72, which contains region I [data not shown]), thus underscoring the importance of this terminal segment for optimal amplification. In the context of a TBSV DI RNA, the role of region I is likely limited to replication and/or stability, since these molecules are neither translated nor packaged efficiently (12).

Although our present results indicate that the 5′ NTR in its entirety is not required in cis for replication of a subviral RNA, we cannot preclude the possibility that this region is essential but that its activity is provided in trans by the helper genome. Alternatively, region II, or other regions of the molecule, might harbor sequences which are able to compensate partially for the absence of those in region I. cis elements important for plus-strand synthesis of prototypical DI RNAs likely reside at or near the minus-strand 3′ terminus, as has been shown for a subviral RNA of the closely related carmovirus turnip crinkle virus (a member of the family Tombusviridae) (8). Examination of the minus-strand sequence of the prototypical TBSV DI RNA, DI-72 (Fig. 1), revealed a tandemly arranged semiconserved 11-nt sequence present at the 3′ terminus of region I (Fig. 8C, lines 1 and 2). Further examination of the minus strand of the TBSV DI RNA allowed the identification of additional variants of the semiconserved undecamer sequence at locations more 5′ in region I and in regions II, III, and IV (Fig. 8C). Alignment of the segments containing the sequence variants allowed the determination of a consensus undecamer motif (Fig. 8C). Interestingly, the deduced consensus sequence, 3′-CCCAAAGAGAG, is very similar to a sequence motif identified by Guan et al. (8), 3′-CCCAAAXGAXXU, at the 3′ termini of minus strands of carmoviruses and carmovirus-related RNAs (Fig. 8C). Additionally, the carmovirus motif variant (−)3′-UCCCAAAGUAU has been shown to have plus-strand promoter activity in vitro (8). This finding, the high degree of similarity between the two consensus motifs, their presence at 3′-terminal and internal locations in strands of the same sense, and the close relatedness of the virally encoded components of the RDRPs of tombusviruses and carmoviruses (18) support the concept that at least some of the TBSV motif variants identified are also involved in plus-strand synthesis. It should be noted that three of the undecamer motifs in the minus strand of region I partially overlap copies of a motif identified by Finnen and Rochon (6) in the plus strand of region I in CNV DI RNAs. It was suggested that the plus-strand motifs facilitate synthesis of minus-strand CNV DI RNAs from DI RNA dimers (6).

Either one or two copies of the carmovirus motif were identified at or near the 3′ termini of the minus-strand viral RNAs examined (8). Similarly, the 3′ termini of minus strands of region I contain two copies of the undecamer motif (Fig. 8C, lines 1 and 2), and versions of the motif can be found at similar positions (and also internally) in other tombusvirus genomic and satellite RNAs (data not shown). Examination of the minus strands of RNAs B1 and B2 revealed that an undecamer motif derived from region II (Fig. 8C, line 7) was positioned at 9 and 6 nt, respectively, from their 3′ termini (Fig. 8D). This observation suggests that this originally internal motif, when repositioned adjacent to a 3′ terminus, may function in a capacity similar to those motifs normally located terminally in region I. In addition, the sequence identity between the most 3′ nucleotides of region I and those in RNAs B1 and B2 implies that they too may be important for RNA synthesis (Fig. 8D).

The roles of the internally positioned undecamer motifs in prototypical DI RNA and RNA B species are less obvious. However, their conservation in different tombusvirus genomes and satellite RNAs (data not shown) indicates likely functional roles. For example, the sequence (−)3′-CCCAAAGAGAG, which conforms precisely to the undecamer consensus, is present in two different TBSV satellite RNAs (3) and is located approximately 45 nt from the 3′ termini of their minus strands. In addition, the two TBSV satellite RNAs contain other internal segments that have very significant sequence identities to internal portions of region I that harbor undecamer motifs (data not shown). The conservation of internal copies of the motif, along with its homology with terminal elements and a defined plus-strand promoter element (8), suggests possible roles as promoters, enhancers, and/or regulatory elements of plus-strand synthesis. Systematic mutagenesis of the undecamer motifs in DI RNA and satellite RNAs is currently under way and should provide further information regarding these repetitive elements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laurie Baggio and members of our laboratory for reviewing the manuscript. We are also grateful to D’Ann Rochon for providing CNV-K2/M5.

This work was supported by grants to K.A.W. from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball L A. Replication of the genomic RNA of a positive-strand RNA animal virus from negative-sense transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12443–12447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgyan J, Rubino L, Russo M. De novo generation of cymbidium ringspot virus defective interfering RNA. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:505–509. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celix A, Rodriguez-Cerezo E, Garcia-Arenal F. New satellite RNAs, but not DI RNAs, are found in natural populations of tomato bushy stunt virus. Virology. 1997;239:277–284. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang Y C, Borja M, Scholthof H B, Jackson A O, Morris T J. Host effects and sequences essential for accumulation of defective interfering RNAs of cucumber necrosis and tomato bushy stunt tombusviruses. Virology. 1995;210:41–53. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreher T W, Hall T C. Mutational analysis of the sequence and structural requirements in brome mosaic virus RNA for minus strand promoter activity. J Mol Biol. 1988;210:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finnen R L, Rochon D M. Characterization and biological activity of DI RNA dimers formed during cucumber necrosis virus coinfections. Virology. 1995;207:282–286. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French R, Ahlquist P. Intercistronic as well as terminal sequences are required for efficient amplification of brome mosaic virus RNA3. J Virol. 1987;61:1457–1465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1457-1465.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan H, Song C, Simon A E. RNA promoters located on (−)-strands of a subviral RNA associated with turnip crinkle virus. RNA. 1997;3:1401–1412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havelda Z, Burgyan J. 3′ terminal putative stem-loop structure required for the accumulation of cymbidium ringspot viral RNA. Virology. 1995;214:269–272. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havelda Z, Dalmay T, Burgyan J. Localization of cis-acting sequences essential for cymbidium ringspot tombusvirus defective interfering RNA replication. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2311–2316. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havelda Z, Dalmay T, Burgyan J. Secondary structure-dependent evolution of cymbidium ringspot virus defective interfering RNA. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1227–1234. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hearne P Q, Knorr D A, Hillman B I, Morris T J. The complete genome structure and synthesis of infectious RNA from clones of tomato bushy stunt virus. Virology. 1990;177:141–151. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillman B I, Carrington J C, Morris T J. A defective interfering RNA that contains a mosaic of a plant virus genome. Cell. 1987;51:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa M, Meshi T, Ohno T, Okada Y. Specific cessation of minus-strand RNA accumulation at an early stage of tobacco mosaic virus infection. J Virol. 1991;65:861–868. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.861-868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston J C, Rochon D M. Deletion analysis of the promoter for the cucumber necrosis virus 0.9-kb subgenomic RNA. Virology. 1995;214:100–109. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K, Hemenway C. The 5′ nontranslated region of potato virus X RNA affects both genomic and subgenomic RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:5533–5540. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5533-5540.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knorr D A, Mullin R H, Hearne P Q, Morris T J. De novo generation of defective interfering RNAs of tomato bushy stunt virus by high multiplicity passage. Virology. 1991;181:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90484-S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koonin E V, Dolja V V. Evolution and taxonomy of positive-strand RNA viruses: implications of comparative analysis of amino acid sequences. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;28:375–430. doi: 10.3109/10409239309078440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazzarini R A, Keene J D, Schubert M. The origins of defective interfering particles of the negative-strand RNA viruses. Cell. 1981;26:145–154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Ball L A. Nonhomologous RNA recombination during negative-strand synthesis of flock house virus RNA. J Virol. 1993;67:3854–3860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3854-3860.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Y J, Liao C L, Lai M M. Identification of the cis-acting signal for minus-strand RNA synthesis of a murine coronavirus: implications for the role of minus-strand RNA in RNA replication and transcription. J Virol. 1994;68:8131–8140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8131-8140.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh L E, Huntley C C, Pogue G P, Connell J P, Hall T C. Regulation of (+):(−)-strand asymmetry in replication of brome mosaic virus RNA. Virology. 1991;182:76–83. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90650-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller W A, Dreher T W, Hall T C. Synthesis of brome mosaic virus subgenomic RNA in vitro by internal initiation on (−) sense genomic RNA. Nature. 1985;313:68–70. doi: 10.1038/313068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy P D, Bujarski J J. Targeting the site of RNA-RNA recombination in brome mosaic virus with antisense sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6390–6394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niesters H G, Strauss J H. Defined mutation in the 5′ nontranslated sequence of Sindbis virus RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:4162–4168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4162-4168.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oster S K, Wu B, White K A. Uncoupled expression of p33 and p92 permit amplification of tomato bushy stunt virus RNAs. J Virol. 1998;72:5845–5851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5845-5851.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacha R F, Ahlquist P. Substantial portions of the 5′ and intercistronic noncoding regions of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus RNA3 are dispensable for systemic infection but influence viral competitiveness and infection pathology. Virology. 1992;187:298–307. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90318-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrault J. Origin and replication of defective interfering particles. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1981;93:151–207. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68123-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilipenko E, Poperechny V K, Maslova S V, Melchers J G, Bruins Slot H J, Agol V. Cis-element, oriR, involved in the initiation of (−) strand poliovirus RNA: a quasi-globular multi-domain RNA structure maintained by tertiary (‘kissing’) interactions. EMBO J. 1996;15:5428–5436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pogue G P, Marsh L E, Hall T C. Point mutations in the ICR2 motif of brome mosaic virus RNAs debilitate (+)-strand replication. Virology. 1990;178:152–160. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rholl J B, Moon D H, Evans D J, Almond J W. The 3′ untranslated region of picornavirus RNA: features required for efficient genome replication. J Virol. 1995;69:7835–7844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7835-7844.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rochon D M. Rapid de novo generation of defective interfering RNA by cucumber necrosis virus mutants that do not express the 20-kDa nonstructural protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11153–11157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rochon D M, Johnston J C. Infectious transcripts from cloned cucumber necrosis virus cDNA: evidence for a bifunctional subgenomic promoter. Virology. 1991;181:656–665. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90899-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.Roux L, Simon A E, Holland J J. Effects of defective interfering viruses on virus replication and pathogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Adv Virus Res. 1991;40:181–211. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60279-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholthof H B, Scholthof K B, Kikkert M, Jackson A O. Tomato bushy stunt virus spread is regulated by two nested genes that function in cell-to-cell movement and host-dependent systemic invasion. Virology. 1995;213:425–438. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholthof K B, Scholthof H B, Jackson A O. The tomato bushy stunt virus replicase proteins are coordinately expressed and membrane associated. Virology. 1995;208:365–369. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Sit T L, Vaewhongs A A, Lommel S A. RNA-mediated trans-activation of transcription from a viral RNA. Science. 1998;281:829–832. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song C, Simon A E. Requirement of a 3′-terminal stem-loop in vitro transcription of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:6–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamatsu N, Watanabe Y, Iwasaki T, Shiba T, Meshi T, Okada Y. Deletion analysis of the 5′ untranslated leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. J Virol. 1991;65:1619–1622. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1619-1622.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Todd S, Towner J S, Brown D M, Semler B L. Replication-competent picornaviruses with complete genomic RNA 3′ noncoding region deletions. J Virol. 1997;71:8868–8874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8868-8874.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van der Kuyl A C, Langereis K, Howing C J, Jaspars E M J, Bol J F. Cis-acting elements involved in replication of alfalfa mosaic virus RNAs in vitro. Virology. 1990;176:346–354. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90004-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van der Vossen E A G, Neeleman L, Bol J F. The 5′ terminal sequence of alfalfa mosaic virus RNA 3 is dispensable for replication and contains a determinant for symptom formation. Virology. 1996;221:271–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Rossum C M, Reusken C B, Brederode F T, Bol J F. The 3′ untranslated region of alfalfa mosaic virus RNA3 contains a core promoter for minus-strand RNA synthesis and an enhancer element. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3045–3049. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Simon A E. Analysis of the two subgenomic RNA promoters for turnip crinkle virus in vivo and in vitro. Virology. 1997;232:174–186. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White K A, Morris T J. Nonhomologous RNA recombination in tombusviruses: generation and evolution of defective interfering RNAs by stepwise deletions. J Virol. 1994;68:14–24. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.14-24.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White K A, Morris T J. Enhanced competitiveness of tomato bushy stunt virus defective interfering RNAs by segment duplication or nucleotide insertion. J Virol. 1994;68:6092–6096. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6092-6096.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White K A, Morris T J. RNA determinants of junction site selection in RNA virus recombinants and defective interfering RNAs. RNA. 1995;1:1029–1040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, B., and K. A. White. Unpublished data.