Abstract

We describe the dynamics of changes in the intracellular pH (pHi) values of a number of lactic acid bacteria in response to a rapid drop in the extracellular pH (pHex). Strains of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactococcus lactis were investigated. Listeria innocua, a gram-positive, non-lactic acid bacterium, was included for comparison. The method which we used was based on fluorescence ratio imaging of single cells, and it was therefore possible to describe variations in pHi within a population. The bacteria were immobilized on a membrane filter, placed in a closed perfusion chamber, and analyzed during a rapid decrease in the pHex from 7.0 to 5.0. Under these conditions, the pHi of L. innocua remained neutral (between 7 and 8). In contrast, the pHi values of all of the strains of lactic acid bacteria investigated decreased to approximately 5.5 as the pHex was decreased. No pronounced differences were observed between cells of the same strain harvested from the exponential and stationary phases. Small differences between species were observed with regard to the initial pHi at pHex 7.0, while different kinetics of pHi regulation were observed in different species and also in different strains of S. thermophilus.

Bacteria have developed different ways to withstand stressful situations, such as a decrease in the pHex. Neutrophilic bacteria like Escherichia coli maintain a pHi that is close to neutral when the pHex is decreased and therefore generate large proton gradients (28). Among the gram-positive bacteria, strains of Enterococcus hirae which were originally identified as Streptococcus faecalis (12) have been studied extensively in order to examine pH homeostasis (14–16). These bacteria also grow at alkaline pH values, and they are considered neutrophiles (31), although they are phylogenetically related to streptococci and lactococci.

Many acid-tolerant fermentative bacteria have developed another strategy; in these organisms the pHi decreases as the pHex decreases during growth (4, 23) in order to maintain a constant pH gradient rather than a constant pHi. Generating a large proton gradient is disadvantageous for fermentative lactic acid bacteria, because proton translocation consumes energy (16), and anaerobic organisms gain significantly less energy from sugar metabolism than aerobes gain. Furthermore, a large proton gradient results in accumulation of organic acid anions in the cytosol (33).

Food fermentations are often carried out by sequential microbial populations; this occurs in dairy fermentations, such as yogurt fermentation (32), as well as in indigenous spontaneous fermentations of cereals and vegetables (7, 10, 20). Lactic acid bacteria, particularly lactobacilli, which are considered the most acid-tolerant bacteria, are often dominant at the end of these fermentations (13, 34). The acid tolerance of these organisms is advantageous, as they have a competitive advantage over known pathogens and other undesirable bacteria when the concentration of organic acids is high (34). A mixture of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus is used for yogurt fermentation. S. thermophilus grows faster in the beginning of a fermentation, whereas L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus finishes the fermentation due to the more pronounced acid tolerance of this species. Another very important lactic acid bacterium from a dairy viewpoint is Lactococcus lactis, whose pHi has been more extensively investigated (3, 4, 22, 23).

The study described here was undertaken in order to investigate the dynamics of pH regulation in individual bacterial cells. Carboxyfluorescein, which was used throughout this study, is a ratiometric pH probe that exhibits no pH sensitivity when it is excited at 435 nm and maximal sensitivity when it is excited at 490 nm. After we obtained a fluorescent signal at each excitation wavelength, a concentration-independent ratio between pH-sensitive and pH-insensitive signals was calculated. The ratio measurements precluded potential artifacts due to variations in dye concentration. This method has been used successfully to measure pHi values in populations of bacteria (3, 22). In FRIM, the technique described above is combined with a microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera, which allows measurements for single cells to be obtained. As bacterial cells are small, the fluorescence intensity of an individual cell is low, which provides a significant experimental challenge. Although this technique has many advantages, pHi examinations of bacteria in which FRIM has been used have been limited to studies of developing Bacillus subtilis forespores (17, 18) and investigations of a mixture of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Listeria innocua (35).

In this study, we used FRIM combined with a perfusion system, which allowed us to determine the dynamics of pHi regulation during a change in pHex, as well as the heterogeneity in pHi in a population. We investigated a number of strains of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus and thus examined variations within species. Finally, L. innocua was included as model pathogenic organism. Previously, we found that pHi regulation in L. innocua was very different from pHi regulation in L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (35).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abbreviations.

FRIM, fluorescence ratio imaging; pHi, intracellular pH; pHex, extracellular pH; ΔpH, pH gradient (pHi − pHex); OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions used in this study are shown in Table 1. MRS and brain heart infusion broth were purchased from Difco, and M17 broth was obtained from Oxoid. Stationary cultures were grown overnight (OD600 for the lactic acid bacteria, approximately 4 to 5; OD600 for L. innocua, 1.3), and exponential-phase cultures were harvested from mid-exponential growth (OD600 for the lactic acid bacteria, approximately 1; OD600 for L. innocua, 0.4).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used and growth conditions

| Species or subspecies | Medium | Growth temp (°C) | Strain(s)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus thermophilus | M17 | 37 | 50, 61, 63, 68 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | MRS | 42 | NCFB 2772, 01, 08 |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | M17 | 30 | 02 |

| Listeria innocua | BHIb | 30 | AJL-1 |

NCFB 2772 was kindly provided by G. Grobben, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. AJL-1 was provided by the Alfred Jørgensen Laboratory Ltd., Copenhagen, Denmark. All other strains were commercial starter cultures obtained from the culture collection at MD Foods R & D, Aarhus, Denmark.

BHI, brain heart infusion broth.

Buffers and solutions.

The pH values of citrate-potassium phosphate buffers were adjusted by mixing citric acid (25 mM) and K2HPO4 (50 mM). A 1 M glucose stock solution was added to all buffers to obtain a final glucose concentration of 10 mM prior to each experiment in order to supply energy to the cells. Solutions containing 50 μM 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (Sigma) in buffer were prepared from a concentrated stock solution (3 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide) by dilution in buffer at pH 7.0 and 5.0. All chemicals were analytical grade and were obtained from Merck, unless indicated otherwise.

Staining protocol.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 2 min) and were resuspended in buffer (pH 7.0) to an OD600 of 0.6. Subsequently, cells were incubated in the presence of 10 μM 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) at 37°C for 30 min. When perfusion experiments were performed, cells were analyzed immediately after staining, while the pH-equilibrated cells used for validation of pHi measurements were stored on ice in the dark for a maximum of 1 h prior to analysis.

The buffers used in this study contained citric acid at a concentration corresponding to a concentration of undissociated citric acid of less than 0.2 mM in the pH 5.0 buffer. We noticed that ΔpH in L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 at pHex 5.0 was approximately 0.5 pH unit lower when the staining buffer was a citrate phosphate buffer than when a pure potassium phosphate buffer was used (data not shown).

Immobilization of cells for microscopic analysis.

Stained cells were immobilized by drawing aliquots of an appropriate dilution through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter and mounting the part of the filter containing the bacteria in a perfusion chamber as previously described (35).

Fluorescence microscopy.

The microscope setup used has been described previously (6) and consisted of a monochromator providing two excitation wavelengths (490 and 435 nm) and an inverted microscope equipped with a ×100 objective. The emitted light (515 to 565 nm) was collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera. Experiments were controlled by using the software package Metafluor 3.5 (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, Pa.), and background subtraction and image analysis were performed with saved experimental data as previously described (35).

The perfusion chamber (model RC-21A; Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, Conn.) was mounted on the stage of the microscope. A schematic diagram of the chamber has been published previously (21). Solutions were perfused through the inlet of the chamber at a rate of 8.3 μl s−1 by using a modified Alitea-XV pump (Microlab Aarhus A/S, Aarhus, Denmark). After passage through the chamber, the liquid was continuously removed from the outlet reservoir by another pump. The perfusion pump was calibrated prior to each session.

In each experiment the perfusion chamber was filled with pH 7.0 buffer after the filter was mounted, and perfusion was initiated at 2 min with a pH 5.0 perfusion solution. All experiments were performed at least twice on different occasions, and in general, the average from one experiment was within the standard deviation of the duplicate experiment for every acquisition point. For clarity, the results of a single experiment are presented below.

Equilibration of pHi with pHex.

Stained cells were suspended in buffers having different pH values. Valinomycin (Sigma) and nigericin (Molecular Probes Inc.) were each added to a final concentration of 5 μM, and this was followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min. Valinomycin renders plasma membranes permeable to potassium ions, and nigericin exchanges potassium for protons; thus, the combined actions of these compounds result in equilibration of both potassium ions and protons across the membrane. The cells were immobilized as described above, and the chamber was filled with buffer containing valinomycin and nigericin before ratio images were acquired.

Addition of valinomycin and nigericin had almost no effect on Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 02, and stained cells of this strain were therefore permeabilized by treatment with 70% ethanol for 30 min prior to resuspension in the appropriate buffers to obtain pH-equilibrated cells.

Calculation of pHi.

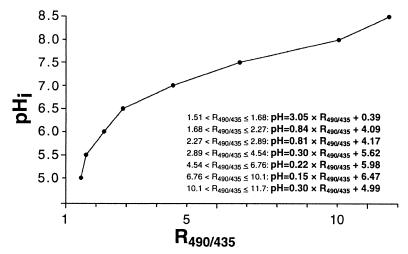

Calculation of pHi from the ratio images was based on pH-equilibrated cells of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772. A piecewise linear equation for the ratio value and pH was derived from the equations shown in Fig. 1. Conversion was automatically performed with Microsoft Excel, and the ratio value for every cell at every time point was converted to pHi before the average and standard deviation were calculated.

FIG. 1.

Correlation between excitation ratio 490 nm/435 nm (R490/435) and pH in pH-equilibrated cells of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 in buffers with pH values ranging from 5.0 to 8.5. At least 20 cells were used for every calibration point. Linear equations were determined for adjacent calibration points, which resulted in seven equations describing the relationship between R490/435 and pH over the pH range investigated.

RESULTS

Rate of pH change during perfusion.

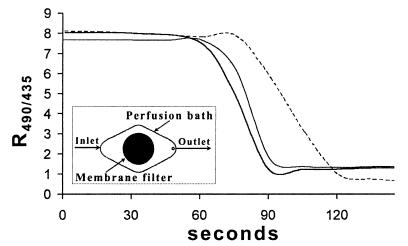

The pH in the chamber during the experiments was estimated by filling the chamber with pH 7.0 buffer containing 50 μM carboxyfluorescein and recording the two excitation images at 15-s intervals. After 60 s, pH 5.0 buffer containing the same concentration of fluorochrome was flushed through the chamber. In two such experiments, ratio images were recorded close to the center of the chamber, where the membrane filter was located. In a third experiment, ratio images were recorded near the outlet of the chamber, and the resulting values are shown in Fig. 2. The data show that the shift from pH 7.0 to 5.0 occurred rapidly. In the center of the chamber, the decrease began almost simultaneously with the perfusion, and the complete change occurred within 30 s after initiation. At the outlet, the response was slightly delayed, but the change was still complete within 1 min. All subsequent analyses were performed close to the center of the chamber. The ratios in Fig. 2 cannot be converted to pHi values by using the equation described above because the experimental setup was different (i.e., a large volume of fluorescent buffer was used instead of stained cells).

FIG. 2.

Rate of R490/435 change during perfusion. The chamber was filled with pH 7.0 buffer containing the fluorescent probe carboxyfluorescein, and thus the initial level was pH 7.0. Perfusion was initiated after 60 s with pH 5.0 buffer containing carboxyfluorescein, and the final level corresponded to pH 5.0. The solid lines show the results of two independent perfusion experiments performed in the area covered by the membrane filter, and the dotted line shows the results of an experiment in which the analysis was performed close to the outlet. The inset is a schematic diagram of the perfusion chamber. The membrane filter was located in the center of the diamond-shaped bath. The perfusion liquid flowed from left to right and left the bath through the outlet.

Validation of pHi calculation from ratios in different bacterial species.

The piecewise linear equation described in Fig. 1 was obtained by using L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772, and we examined whether this equation could be used to determine pHi in all of the species investigated. To do this, all strains were pH equilibrated at pHex 7.0 and 6.0, and the ratios for more than 20 cells in each experiment were recorded on a spreadsheet. The equation was subsequently used to convert ratio values to pHi values, as shown in Table 2. For all strains, the pHi should have been the same as the pHex after equilibration. The largest difference between pHi and pHex for the strains was 0.2, which is close to the accuracy of the method (35), and the equation was therefore used to convert ratios to pHi values throughout the experiment.

TABLE 2.

Calculated pHi values for pH-equilibrated cells as determined by the equation derived from L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 data

| Strain | pHi at:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| pHex 6.0 | pHex 7.0 | |

| S. thermophilus 50 | 6.1 ± 0.1a | 7.0 ± 0.1 |

| S. thermophilus 61 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.1 |

| S. thermophilus 63 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| S. thermophilus 68 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.0 |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 01 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.1 |

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 08 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis 02 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| L. innocua | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± standard deviations based on the data obtained for at least 20 cells.

Change in the pHi of lactic cocci as a response to decreasing pHex.

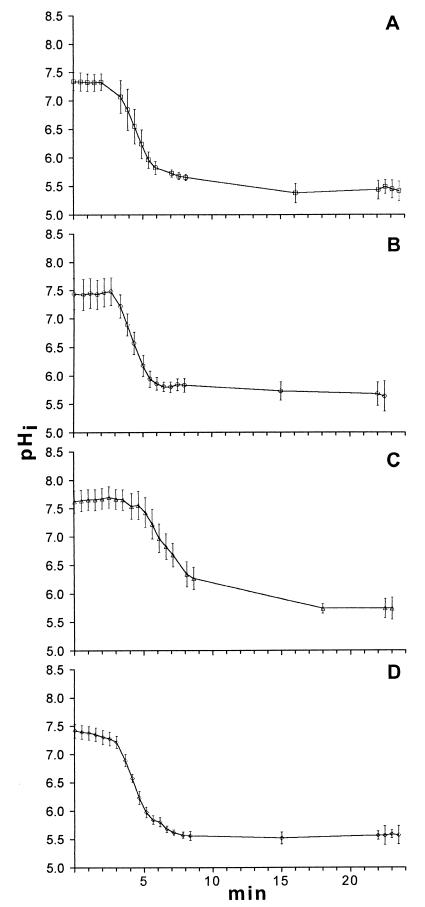

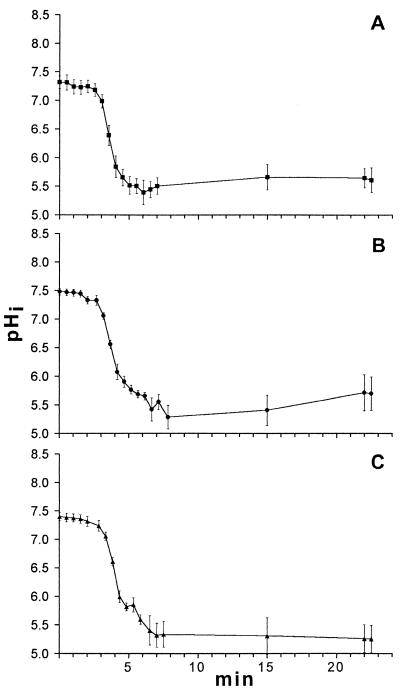

Figure 3 shows the changes in the pHi values of stationary-phase cells of four strains of S. thermophilus as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. At 2 min perfusion was initiated, and at 2.5 min the pHex was 5.0 in the center of the chamber, where the cells were located. All of the streptococcal strains had initial pHi values between 7.4 and 7.6 (Fig. 3). The ΔpH at the end of the experiment (>20 min) was close to 0.5 pH unit for all strains. The standard deviations in the starting pHi values for the streptococci ranged from 0.15 to 0.25 pH unit, which indicated that the populations were homogeneous. S. thermophilus 63 maintained a high pHi for a longer period than the other strains; the pHi of this strain decreased to 6.5 after 5 min of perfusion (Fig. 3C), while the pHi values of the other strains reached this level within 2 to 2.5 min (Fig. 3A, B, and D). The pHi profile of stationary-phase cells of L. lactis subsp. lactis is shown in Fig. 4. The behavior of this bacterium was similar to the behavior of S. thermophilus 63 (Fig. 3C), as the pHi decreased slowly. In addition, the ΔpH was relatively high (0.8 pH unit) when the pHi stabilized at pHex 7.0 or 5.0.

FIG. 3.

Change in the pHi of four strains of S. thermophilus as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. Perfusion was initiated after 2 min. (A) S. thermophilus 50. (B) S. thermophilus 61. (C) S. thermophilus 63. (D) S. thermophilus 68. Each line shows the average values for at least 20 individual cells, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

FIG. 4.

Change in the pHi of L. lactis subsp. lactis 02 as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. Perfusion was initiated after 2 min. The line shows the average values for at least 20 individual cells, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

Change in the pHi of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in response to a decrease in the pHex.

The pHi profiles for three strains of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus harvested from stationary-phase cultures are shown in Fig. 5. The pHi values of all of these strains decreased more rapidly than pHi values of the cocci decreased (Fig. 3 and 4). After 2.5 min of perfusion, the pHi values of all three strains had decreased to 6.0 or less. The ΔpH was 0.5 pH unit for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 and 01 (Fig. 5A and B) and as low as 0.3 pH unit for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 08 (Fig. 5C). The initial pHi values were 7.3 to 7.5, and the standard deviations for all three strains were less than 0.1 pH unit. The heterogeneity in pHi increased to 0.2 to 0.3 pH unit after perfusion.

FIG. 5.

Change in the pHi of three strains of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. Perfusion was initiated after 2 min. (A) L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772. (B) L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 01. (C) L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus 08. Each line shows the average values for at least 20 individual cells, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

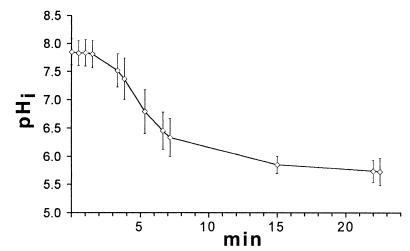

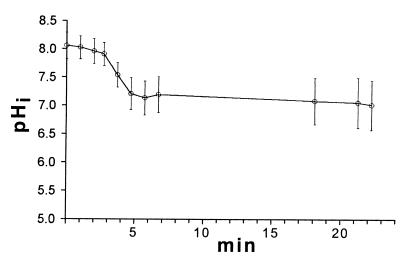

Change in the pHi of L. innocua in response to a decrease in the pHex.

L. innocua is an example of a homeostatic bacterium (35), and under the same perfusion conditions that were used for the lactic acid bacteria, the pHi of stationary-phase cells was close to neutral (i.e., between 8.0 and 7.1) when the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0 (Fig. 6). The heterogeneity in pHi values was more pronounced after perfusion, and the heterogeneity reached a level of almost 0.9 pH unit.

FIG. 6.

Change in the pHi of L. innocua as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. Perfusion was initiated after 2 min. The line shows the average values for at least 20 individual cells, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

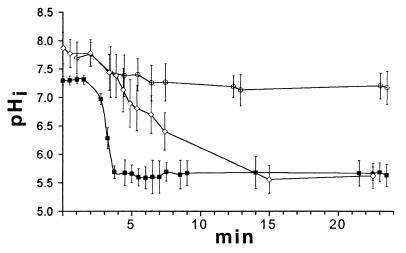

Change in the pHi in response to a lower pHex in exponentially growing cells.

Cells harvested from exponential cultures of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772, L. lactis subsp. lactis, and L. innocua were examined in order to investigate the influence of growth phase on pHi regulation (Fig. 7). The responses of these cells were comparable to the responses of stationary-phase cells of the same species (Fig. 4, 5A, and 6). The heterogeneities of the populations were also similar, although the standard deviation in the pHi of L. innocua after perfusion was less pronounced than that in the stationary-phase culture (Fig. 6).

FIG. 7.

Changes in the pHi of exponentially growing cells of L. innocua (○), L. lactis subsp. lactis 02 (◊), and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772 (■) as the pHex was decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. Perfusion was initiated after 2 min. Each line shows the average values for at least 20 individual cells, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

In most studies of pHi in lactic acid bacteria the workers have used the ion distribution of radioactively labeled weak acids to measure pHi (4, 11, 13, 23, 26, 27, 36). This method involves equilibration of a weak acid between the medium and the cytosol, and it is therefore not possible to measure rapid changes in pHi. Recent studies in which spectrofluorometric determination of pHi was used included dynamic measurements obtained after various substances were added (3, 19), but as the measurements were determined in a cuvette, it was not possible to determine the pHi values for single cells. Recently, we demonstrated that the pHi values of single cells of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and L. innocua could be determined by FRIM at a pHi range of 5.0 to 8.0 (35). In this study, we used the same method to monitor the dynamic changes in the pHi values of a number of lactic acid bacteria as the pHex was rapidly decreased from 7.0 to 5.0. The decrease in pHex did not constitute a severe acid shock, as lactic acid bacteria naturally acidify the external medium to pH values below 5.0 during growth (11).

It has been suggested that pH homeostasis is best reflected in the ability to restore the pHi after perturbation (2), including rapid shifts in pHex. The results of previous studies of lactic acid bacteria have not been entirely consistent with regard to pH regulation at low pHex values. In L. lactis at pHex 5.0, the ΔpH ranges from 0.4 pH unit (4) to 2 pH units (3, 22, 29), and in L. plantarum at pHex 4.5, the ΔpH ranges from 0.7 pH unit (20) to almost 2 pH units (36). Some of the differences might be attributed to the presence of organic acid anions (34); e.g., low levels of lactate (less than 30 mM) significantly reduce the pHi of L. lactis (4). The concentrations of compensating cations, such as potassium and sodium ions, are also known to influence pHi values (2, 12), and experimental differences complicate comparisons of the results of different studies. In this study, however, we compared cells under the same experimental conditions for all of the species investigated, and we observed that the pHi values of all of the lactic acid bacteria investigated decreased, which resulted in ΔpH values of 0.5 to 0.8 pH unit. The pHi values for the populations of lactic acid bacteria were also quite homogeneous, which indicated that a pHex of 5.0 is not a pronounced stress for these bacteria. In contrast, the ΔpH for L. innocua was more than 2 pH units when the pHex was 5.0, which confirmed that this bacterium is homeostatic (Fig. 6 and 7). The greater heterogeneity in pHi at pHex 5.0 (Fig. 6) may reflect greater stress imposed on L. innocua at low pHex values.

In our experiments, exponentially growing cells of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus NCFB 2772, L. lactis subsp. lactis, and L. innocua exhibited the same pattern of pHi regulation (Fig. 7) as stationary-phase cells exhibited (Fig. 5A and 6). This is somewhat surprising, as it is generally accepted that cells entering the stationary phase undergo radical changes which ensure that they can deal with physical stresses (30), and it is known that low pHex values (such as the pHex values in stationary phase) induce adaptation mechanisms that increase survival (5, 8, 9, 27). The similarities in pHi regulation in stationary and exponentially growing cells may reveal a universal characteristic of these bacteria, but the influence of methodological artifacts needs to be investigated to confirm this observation. For example, we cannot eliminate the possibility that incubation in buffer containing glucose and prefluorochrome induces similar physiological changes in the two growth phases.

The rate and pattern of pHi regulation in the species investigated appear to mirror the acid tolerance of the bacteria. In the very acid-tolerant lactobacilli the pHi decreases faster than it decreases in the moderately acid-tolerant lactic cocci during a change in pHex, and the pHi of L. innocua does not decrease below 7.0. The different rates of pHi decrease observed for the strains of S. thermophilus (Fig. 3) may also be correlated with differences in acidification performance. S. thermophilus 63, which exhibited the slowest decrease in pHi during perfusion (Fig. 3C), was investigated because it exhibited poor acidification when standard fermentation tests in milk were performed (unpublished data).

There are several possible mechanisms by which a bacterium can regulate pHi, but the most important mechanism in fermentative bacteria appears to be the proton-translocating ATPase (11, 16, 24). The pH data for this enzyme isolated from Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum revealed that the pH optima were 5.0 to 5.5 (1, 10, 24), and these values are markedly lower than the pH optima for strains of S. thermophilus and L. lactis, which were determined to be 7.0 to 7.5 (24). Another parameter involved in pHi regulation is the overall proton permeability of the plasma membrane. In L. casei and L. plantarum, this permeability was minimal at pH 4.0 (1, 10), and in the acid-sensitive organism Actinomyces viscosus it was minimal at pH 6.0 (1). These observations could explain the rapid decreases in pHi values in lactobacilli (Fig. 5), as these bacteria may not actively regulate pHi until the pHex is low.

Other factors, such as the cytoplasmic buffering capacity, are thought to have little influence on pHi regulation (11), and similar values have been found with most bacteria (2). Decarboxylation of amino acids leads to biochemical consumption of protons, and this process may contribute to acid tolerance during growth (25). However, the buffers used in this study did not contain amino acids, and therefore it is unlikely that consumption of amino acids was involved in pHi regulation to significant extent.

Although the mechanisms behind the observed differences in pHi regulation cannot be evaluated without further studies, the physiological significance of maintaining a small ΔpH is obvious. The energy requirement for proton translocation and accumulation of organic acid anions is reduced in lactic acid bacteria compared to homeostatic bacteria, and this is probably one of the reasons for the predominance of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations.

It is conceivable that the differences in the rate of pHi decrease in the lactic acid bacteria investigated could be used to improve industrial fermentations, as the change in pHi appears to mirror acid tolerance. We are planning to test this hypothesis in experiments in which we will use L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus as model organisms in mixed-culture fermentations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The skillful technical assistance of Jan Hansen is gratefully acknowledged. We thank N. Arneborg and A. Gravesen for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was part of the FØTEK2 program supported by the Danish Dairy Research Foundation (Danish Dairy Board) and the Danish government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender G R, Marquis R E. Membrane ATPases and acid tolerance of Actinomyces viscosus and Lactobacillus casei. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2124–2128. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2124-2128.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth I R. Regulation of cytoplasmic pH in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:359–378. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.4.359-378.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breeuwer P, Drocourt J-L, Rombouts F M, Abee T. A novel method for continuous determination of the intracellular pH in bacteria with the internally conjugated fluorescent probe 5 (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:178–183. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.178-183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook G M, Russell J B. The effect of extracellular pH and lactic acid on pH homeostasis in Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus bovis. Curr Microbiol. 1994;28:165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster J W, Hall H K. Inducible pH homeostasis and the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5129–5135. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.16.5129-5135.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guldfeldt L U, Arneborg N. Measurements of the effects of acetic acid and extracellular pH on intracellular pH of nonfermenting, individual Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:530–534. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.530-534.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halm M, Lilie A, Sørensen A K, Jakobsen M. Microbiological and aromatic characteristics of fermented maize doughs for kenkey production in Ghana. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;19:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90179-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey E W, Hirschfield I N. Low-pH-induced effects on patterns of protein synthesis and on internal pH in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1038–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1038-1045.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill C, O'Driscoll B, Booth I R. Acid adaptation and food poisoning microorganisms. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;28:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong S-I, Kim Y-J, Pyun Y-R. Acid tolerance of Lactobacillus plantarum from Kimchi. Food Sci Technol- Lebensm- Wiss Technol. 1999;32:142–148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutkins R W, Nannen N L. pH homeostasis in lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76:2354–2365. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakinuma Y. Inorganic cation transport and energy transduction in Enterococcus hirae and other streptococci. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1021–1045. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1021-1045.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashket E R. Bioenergetics of lactic acid bacteria: cytoplasmic pH and osmotolerance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H, Murakami N, Unemoto T. Regulation of the cytoplasmic pH in Streptococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13246–13252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi H, Suzuki T, Kinoshita N, Unemoto T. Amplification of the Streptococcus faecalis proton-translocating ATPase by a decrease in cytoplasmic pH. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1157–1160. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1157-1160.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi H, Suzuki T, Unemoto T. Streptococcal cytoplasmic pH is regulated by changes in amount and activity of a proton-translocating ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:627–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magill N G, Cowan A E, Koppel D E, Setlow P. The internal pH of the forespore compartment of Bacillus megaterium decreases by about 1 pH unit during sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2252–2258. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2252-2258.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magill N G, Cowan A E, Leyva-Vazquez M A, Brown M, Koppel D E, Setlow P. Analysis of the relationship between the decrease in pH and accumulation of 3-phosphoglyceric acid in developing forespores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2204–2210. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2204-2210.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magni C, de Mendoza D, Konings W N, Lolkema J S. Mechanism of citrate metabolism in Lactococcus lactis: resistance against lactate toxicity at low pH. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1451–1457. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1451-1457.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald L C, Fleming H P, Hassan H M. Acid tolerance of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2120–2124. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meaden P G, Arneborg N, Guldfeldt L U, Siegumfeldt H, Jakobsen M. Endocytosis and vacuolar morphology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are altered in response to ethanol stress or heat shock. Yeast. 1999;15:1211–1222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990915)15:12<1211::AID-YEA448>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molenaar D, Abee T, Konings W N. Continuous measurement of the cytoplasmic pH in Lactococcus lactis with a fluorescent pH indicator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1115:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nannen N L, Hutkins R W. Intracellular pH effects in lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:741–746. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nannen N L, Hutkins R W. Proton-translocating adenosine triphosphatase activity in lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:747–751. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomura M, Nakajima I, Fujita Y, Kobayashi M, Kimoto H, Suzuki I, Aso H. Lactococcus lactis contains only one glutamate decarboxylase gene. Microbiology. 1999;145:1375–1380. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Sullivan E, Condon S. Relationship between acid tolerance, cytoplasmic pH, and ATP and H+-ATPase levels in chemostat cultures of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2287–2293. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2287-2293.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Sullivan E, Condon S. Intracellular pH is a major factor in the induction of tolerance to acid and other stresses in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;63:4210–4215. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4210-4215.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padan E, Zilberstein D, Schuldiner S. pH homeostasis in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;650:151–166. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(81)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poolman B, Driessen A J, Konings W N. Regulation of solute transport in streptococci by external and internal pH values. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:498–508. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.498-508.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rees C E D, Dodd C E R, Gibson P T, Booth I R, Stewart G S A B. The significance of bacteria in stationary phase to food microbiology. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;28:263–275. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rius N, Solé M, Francia A, Lorén J G. Buffering capacity and membrane H+ conductance of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;120:291–296. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson R K, Tamime A Y. Microbiology of fermented milks. In: Robinson R K, editor. Dairy microbiology. Vol. 2. 1990. pp. 291–343. The microbiology of milk products, 2nd ed. Elsevier Applied Science, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell J B. Another explanation for the toxicity of fermentation acids at low pH: anion accumulation versus uncoupling. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;73:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell J B, Diez-Gonzales F. The effects of fermentation acids on bacterial growth. Adv Microb Physiol. 1998;39:205–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegumfeldt H, Rechinger K B, Jakobsen M. Use of fluorescence ratio imaging for intracellular pH determination of individual bacterial cells in mixed cultures. Microbiology. 1999;145:1703–1709. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsau J-L, Guffanti A A, Montville T J. Conversion of pyruvate to acetoin helps to maintain pH homeostasis in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:891–894. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.891-894.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]