Abstract

MORF4-related gene on chromosome 15 (MRG15), a chromatin remodeller, is evolutionally conserved and ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues and cells. MRG15 plays vital regulatory roles in DNA damage repair, cell proliferation and division, cellular senescence and apoptosis by regulating both gene activation and gene repression via associations with specific histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase complexes. Recently, MRG15 has also been shown to rhythmically regulate hepatic lipid metabolism and suppress carcinoma progression. The unique N-terminal chromodomain and C-terminal MRG domain in MRG15 synergistically regulate its interaction with different cofactors, affecting its functions in various cell types. Thus, how MRG15 elaborately regulates target gene expression and performs diverse functions in different cellular contexts is worth investigating. In this review, we provide an in-depth discussion of how MRG15 controls multiple physiological and pathological processes.

Keywords: epigenetic modifications, MRG15, chromatin remodelling, DNA damage repair, cell proliferation, senescence

Introduction

MORF4-related gene on chromosome 15 (MRG15), also known as mortality factor 4-like protein 1 (MORF4L1), is a member of a family of transcription factor-like genes called the MRG family. Although there are seven members of this family, only MORF4 (Mortality factor on chromosome 4), MRG15/MORF4L1, and MRGX (MORF-related gene on chromosome X)/MORF4L2 are efficiently transcribed and expressed, while the other members are not effectively transcribed [1, 2]. MORF4 was the first MRG family protein identified, and it is recognized as a cellular ageing-related gene in a subset of human immortalized cell lines assigned to complementation group B [3, 4]. However, the tissue-specific expression profile of MORF4 is unclear. Studies have shown that MRGX is present in vertebrates and is widely expressed in mammalian tissues. Although MRGX is nonessential for cell growth and development [5], MRGX has been demonstrated to be a member of the Tat interacting protein 60 kDa (Tip60)/NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex and might be a diagnostic marker for tumours and involved in drug resistance after tumour treatment [6–8]. In different developmental stages, MRG15 is ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues, among which the testis is the most common [9]. As MRG15 is a highly evolutionarily conserved protein, homologues of MRG15 have been found to be present in more than twenty species, from yeast to humans, suggesting its vital role in various biological processes [1].

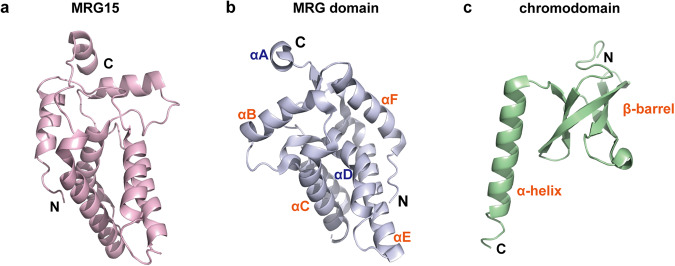

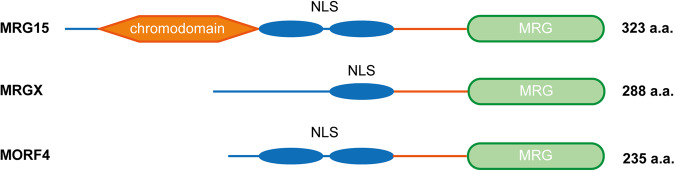

MRG15 shares some common structural characteristics with MORF4 and MRGX. Specifically, all three proteins are localized to the nucleus and have a common conserved MRG domain in the C-terminus, which is a defining and key feature containing several conserved sequence motifs, including a helix-loop-helix domain and a leucine zipper. Notably, the C-terminal MRG domains of MORF4, MRGX, and MRG15 are different in several amino acids and contain several conserved hydrophobic residues that organize the scaffold of the structure [1, 10]. In addition to these three proteins, the male-specific lethal 3 (MSL3) protein, a member of the dosage compensation complex that modulates the expression of X-linked genes, also contains an MRG domain [11]. Through studies on the crystal structure of the MRG domain (Fig. 1a, b), it was revealed that the structure is composed of six α helices [10, 12–15]. The core structure is composed of four helices that form two sets of antiparallel helices (αB, αC and αE, αF) or mutually orthogonal helix hairpins, while helices αD and αA are adjunct to the core structure [14]. There are two discrete interaction surfaces in the MRG domain: one is plastic, and the other is rigid. The former interaction surface is involved in molecular mimicry, and the latter is engaged in the conserved FxLP motif, a sequence motif shared by most high-affinity interactors [12, 13]. The specific characteristics of the MRG-binding conserved motif signature are defined as FxLP(x) 2-3Φ, which means that the MRG15-binding protein x is separated by 2-3 amino acids with Φ, a hydrophobic amino acid [12, 16]. Therefore, the functions of MRG domains are diverse and might change the stability of interactions to accommodate different biological processes. The unique MRG domain provides a molecular foundation for the functions of MRG family members. Since the stereochemical structure of the MRG domain is similar to the core binding domains of Cre and XerD, which function as tyrosine site-specific recombinases, MRG proteins might have DNA-binding potential [14]. In addition, MRG15 and MORF4 both contain a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) with phosphorylation sites at the sides, while there is only a single NLS in MRGX [2].

Fig. 1. The crystal structures of human MRG15 and its MRG domain and chromodomain.

a The overall crystal structure of human MRG15. The C-terminus and N-terminus of MRG15 are shown in the picture. Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure ID: 8C60. b The crystal structure of the MRG domain of MRG15. The MRG domain is composed of six α helices. The core structure is composed of four helices that form two sets of antiparallel helices (αB, αC and αE, αF) or mutually orthogonal helix hairpins, while helices αD and αA are adjunct to the core structure. PDB structure ID: 2F5J. c The crystal structure of the chromodomain of MRG15. The chromodomain is composed of a β-barrel and a long α-helix. PDB structure ID: 2F5K.

The reason that MRG15 is different from the other two MRG proteins is largely attributed to its extensional chromodomain in the N-terminus. Composed of a β-barrel and a long α-helix, the MRG15 chromodomain is structurally similar to the dMOF (drosophila male on first) chromo barrel domain (Fig. 1c) [17]. The MRG15 chromodomain has been found to bind to methylated Lys36 of histone H3 (H3K36) and act as an adaptor to associate with modified H3 proteins via a mode different from that of the chromodomains of heterochromatin-binding protein 1 (HP1) and Polycomb (Pc), which interact with methylated Lys9 and Lys27 of histone H3 (H3K9 and H3K27), respectively [13, 17]. The C-terminus and N-terminus of MRG15 are linked together by a flexible structural region, which functions in regulating the conformation of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains. The C-terminal and N-terminal domains of MRG15 interact with different factors and influence the overall molecular structure and biological functions of MRG15 in a collaborative way [10] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The structural features of MRG family members.

The C-terminal MRG domain, which is responsible for mediating protein‒protein interactions, contains several conserved motifs, including a helix-loop-helix and a leucine zipper. The unique N-terminal MRG15 chromodomain consists of a β-barrel and a long α-helix and can bind to methylated Lys36 (H3K36). NLS nuclear localization signal, a.a. amino acids.

MRG15-related nuclear protein complexes

Deeper biochemical and structural biological insights have revealed that chromodomain-containing proteins can interact and recognize histones or other associated proteins in nucleoprotein complexes, therefore mediating the chromatin remodelling that activates or represses the transcription of different genes [18]. MRG15 is widely considered a chromatin modifier as well as a transcriptional regulator, and in most cases performs its biological functions as a component of multinucleoprotein complexes. Moreover, the MRG15 MRG domain has been demonstrated to be the binding site of many proteins, including PAM14 (protein associated with MRG15 of 14 kDa), MRGBP (MRG domain-binding protein), Pf1 (plant homeodomain zinc finger protein), and PALB2 (partner and localizer of BRCA2), to induce interactions [10, 12–14, 16, 19, 20].

MAF1 and MAF2 complexes

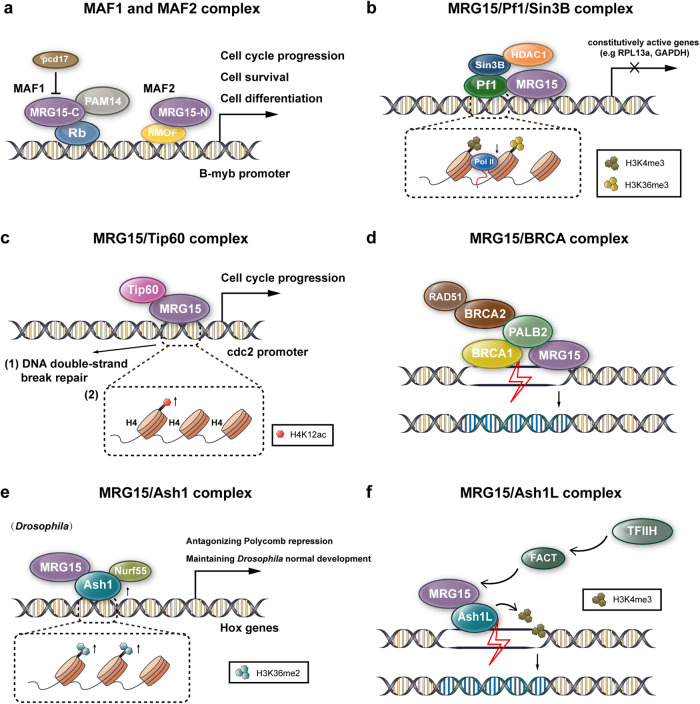

MRG15 interacts with the nuclear proteins PAM14 and Rb (retinoblastoma tumour suppressor) and is considered to be a component of a cellular protein complex called MAF1 (MRG15-associated factor 1) that regulates transcription [21, 22]. Structurally, the human MRG15 MRG domain binds to the N-terminus of PAM14, which is composed of residues Ile160, Leu168, Val169, Trp172, Tyr235, Val268, and Arg260. Upon their interaction, a shallow hydrophobic pocket is formed. In addition, both the helix-loop-helix and leucine zipper motifs of MRG15 are required for the interaction [10]. Studies have demonstrated that MRG15 can block Rb-induced repression of the B-myb promoter by binding to Rb and displacing E2F from the complex, thus increasing B-myb promoter activity [21, 23]. B-myb can physiologically regulate cell cycle progression, cell survival and cell differentiation, and derepression of the B-myb promoter might lead to apoptosis in neurons. MRG15 has been found to bind to a paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD)-related antigen, pcd17, and pcd17 negatively regulates MRG15-induced activation of the B-myb promoter. However, how this interaction further affects neuronal survival and the pathogenesis of PCD remains unclear [23] (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. MRG15-related nuclear protein complexes.

a MAF1 and MAF2 complexes. The MAF1 complex consists of MRG15, PAM14 and Rb, which can be negatively regulated by pcd17. The MAF2 complex is composed of MRG15 and hMOF. MAF1 and MAF2 can both promote B-myb promoter activity, subsequently facilitating cell cycle progression, cell survival and cell differentiation. MRG15-C, C-terminal MRG domain of MRG15; MRG15-N, N-terminal chromodomain of MRG15. b MRG15/Pf1/Sin3B complex. This complex, composed of MRG15, Pf1, Sin3B and HDAC1, inhibits the progression of RNA polymerase II and transcriptional activity by binding H3K4me3/H3K36me3-enriched nucleosomes. c MRG15/Tip60 complex. The MRG15/Tip60 complex has effects on (1) DNA double-strand break repair and (2) transcriptional activation of the cdc2 promoter via acetylation of H4K12, thereby facilitating cell cycle progression. d MRG15/BRCA complex. This complex is composed of MRG15, BRCA1, PALB2, BRCA2, and RAD51. Once DNA double-strand breaks occur, PALB2, which directly binds BRCA1 and MRG15, recruits them to DNA damage sites. BRCA1 and MRG15 are responsible for repair site selection and maintenance of chromatin accessibility, respectively. After colocalization, PALB2 recruits BRCA2 and RAD51 for DNA damage repair. e MRG15/Ash1 complex. In Drosophila, the MRG15/Ash1 complex, which is composed of MRG15, Ash1 and Nurf55, stimulates H3K36 dimethylation on nucleosomes of Hox genes and maintains normal development. f MRG15/Ash1L complex. Upon UV irradiation, the MRG15/Ash1L complex deposits H3K4me3 on nucleosomes and recruits the histone chaperone FACT and the TFIIH complex to damage sites, thus mediating nucleotide excision repair.

Furthermore, MRG15 has been shown to associate with the hMOF protein, an MYST family histone acetyltransferase, in another complex called MAF2 (MRG15-associated factor 2). hMOF is a homologue of Drosophila MOF, which participates in the acetylation of histone H4 to increase the transcription of genes on the X male chromosome. The MRG15 chromodomain at the N-terminus is needed for MAF2 assembly. This complex can also promote HAT-associated activity and B-myb promoter activity [22] (Fig. 3a).

MRG15/Pf1/Sin3B complex

Several studies have confirmed that MRG15 binds to Pf1, a plant homeodomain zinc finger protein that transcriptionally modulates the balance between the HDAC corepressors sin3 and TLE (Transducin-Like Enhancer of Split) [15, 24–26]. The MRG15 MRG domain and Pf1 MRG-binding domain (MBD, residues 200–241) present a composite surface for the binding of Pf1 plant homeodomain 1 (PHD1, residues 48–116) [20]. Pf1 connects MRG15 with Sin3 and the other component of the complex through multivalent interactions [26]. A study also revealed that the MRG15 MRG domain competes with instead of cooperating with the paired amphipathic helix2 (PAH2) domain of Sin3 for binding to Sin3 interaction domain 1 of Pf1 (SID1), thereby disrupting the interaction between Pf1 and Sin3 [26]. This proves that the MRG15 MRG-Pf1 interaction has a higher affinity than the Sin3 PAH2-Pf1 interaction, while the molecular basis of the interaction and how the interaction influences the function of the complex are unknown. Moreover, a stable mammalian complex composed of the corepressor Sin3B, the histone deacetylase HDAC1, MRG15, and Pf1, has been discovered. This complex inhibits the progress of RNA polymerase II along the transcribed regions and represses transcriptional activity by binding H3K4me3/H3K36me3-enriched nucleosomes, thereby playing an important role in transcriptional regulation [24] (Fig. 3b). Moreover, the involvement of MRG15 in the Sin3/HDAC complex might be associated with retinol-binding protein (RBP2, also known as JARID1A), a JmjC domain-containing protein, and contribute to maintaining the level of H3K4 methylation at transcribed regions and the transcriptional elongation state [25].

MRG15/Tip60 complex

MRG15, as well as its homologue Eaf3, has been widely identified as members of the Tip60/NuA4 HAT complex, which is responsible for transcriptional modulation and DNA double-strand break repair by catalysing histone modifications in organisms from yeast to humans [14, 19, 25, 27–30]. The MRG15/Tip60 complex has a cooperative effect on transcriptional activation via acetylation of H4K12 in the cdc2 promoter in human cell lines [27] (Fig. 3c). In prostate cells, MRG15 interacts with MRGBP and Tip60 and recruits MRGBP to regions of active genes through its binding to H3K4me1/3, thus affecting the activity of androgen receptor (AR)-associated enhancer and promoter regions [19]. Data from these studies indicate that the MRG15-containing Tip60 HAT complex associates with different histones, as well as different amino acid sites. This finding suggests the various functions of MRG15 in histone modification. There is a submodule of the Tip60/NuA4 complex called Trimer Independent of NuA4 involved in Transcription Interactions with Nucleosomes (TINTIN), which was initially found in yeast. This complex can regulate nucleosome transactions during transcription elongation [29, 31]. Later, a functionally similar mammalian complex composed of MRG15/X, MRGBP, BRD8, and EP400NL was discovered. The protein EP400NL in the complex, a homologue of the Tip60/NuA4 subunit EP400 at the N-terminus, competes for binding to BRD8. It can be assumed that the BRD8 H4ac-binding bromodomain, along with the MRG15 H3K36me3-binding chromodomain in the transcribed region, might be potentially responsible for transcriptional regulation in chromatin-based nuclear processes [32].

MRG15/BRCA complex

MRG15 is a partner of PALB2 and is present in the BRCA complex [16, 33–36]. PALB2 was previously characterized to connect the two primary breast cancer susceptibility gene products BRCA1 and BRCA2 at DNA damage sites, and it plays a key role in DNA double-strand break repair by homologous recombination (HR) [37, 38]. MRG15 not only directly binds to PALB2, a tumour suppressor protein, in a multiprotein complex and tethers PALB2 to active genes but also binds to the integral BRCA complex (containing BRCA1, PALB2, BRCA2, and RAD51) and recruits it to sites of DNA damage. The link between MRG15 and PALB2 is important in DNA double-strand break repair and maintenance of chromatin [16, 33–35, 39]. Structural and biochemical studies have revealed that the MRG15 MRG domain is connected to both N-terminal and C-terminal of PALB2, while the peptide containing amino acids 597–630 in PALB2 is important for the stability of the complex. Moreover, PALB2 competes with other transcriptional MRG-binding factors for the same extended binding interface with similar affinity [16] (Fig. 3d).

MRG15/Ash1 (Ash1L) complex

Previous studies have shown that MRG15 and Nurf55 (also known as Caf1) are two subunits of both the Drosophila Ash1 (Absent, small, or homeotic discs 1) and human Ash1L (Ash1-Like) complexes [40, 41]. MRG15 is connected to a conserved FxLP motif close to the Ash1 catalytic SET domain, mainly through an extensional segment located at the N-terminus, and triggers Ash1/Ash1L H3K36 [40–44] and H3K4 [45] methyltransferase activity on nucleosomes. Studies on the crystal structure of the MRG15/Ash1L complex have proven that an autoinhibitory loop in the post-SET region of Ash1L is released and that the conformation of the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) binding pocket of Ash1L is changed upon the interaction of Ash1L with MRG15 [42, 43]. In contrast to these findings, a recent study found that the binding of MRG15 does not affect the structure of either the autoinhibitory loop or SAM binding site of ASH1L [44]. In Drosophila, the MRG15/Ash1 complex can antagonize Polycomb repression and maintain a transcriptionally active state and normal gene expression during development [40, 41] (Fig. 3e). In response to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the MRG15/Ash1L complex facilitates successive deposition of H3K4me3 and recruits the histone chaperone FACT (FAcilitates Chromatin Transcription) and the TFIIH (Transcription Factor IIH) complex, thus allowing verification of DNA damage in genome-wide nucleotide excision repair (NER) [45] (Fig. 3f).

Other MRG15-associated complexes

MRG15 has also been found to be a component of two gene silencing complexes, LAF (LID-associated factors) and RLAF (RPD3 and LID-associated factors). LID is a histone H3K4me2/3 demethylase, while RPD3 is a histone deacetylase. These two complexes are related to histone deacetylation and mediation of nucleosome assembly at regulatory elements of NOTCH target genes, leading to selective gene silencing through mutual crosstalk with the histone chaperones ASF1 and NAP1, which are H3/H4 chaperones and H2A/H2B chaperones, respectively [46]. MRG15 also interacts with the nuclear receptor LRH-1, and the MRG15–LRH-1 complex rhythmically regulates genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism through the recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and histone acetylation [47]. It can be concluded from these data that MRG15 orchestrates epigenetic remodelling and transcriptional activity in widespread contact with HAT/HDAC-associated complexes as a component of these complexes.

MRG15 in physiological and pathological processes

MRG15 in DNA homologous recombination repair

MRG15 deletion in neural stem/progenitor cells (NSCs) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) results in serious defects in the DNA damage response post ionizing radiation exposure, delayed recruitment of repair proteins to damage sites, inhibited acetylation of H2A and H2AX and reduced formation of nuclear Rad51 foci [28, 36, 48], and these effects are potentially attributed to MRG15-associated complexes. Since MRG15 is a component of the Tip60/NuA4 complex, it has been widely confirmed that this complex is indispensable for DNA double-strand break repair [37, 38, 49]. A study revealed that in Drosophila, the Tip60/NuA4 multiprotein complex promotes the acetylation of nucleosomal phospho-H2Av, a Drosophila H2AX homologue, post ionizing radiation exposure, and replaces it with an unmodified H2Av protein at sites of DNA double-strand breaks, while deletion of either dTip60 or dMRG15 results in a decreased phospho-H2Av level and impairment of the DNA damage response, suggesting that MRG15 is necessary for this function [38]. However, the precise mechanism by which MRG15 in the Tip60/NuA4 complex functions in DNA damage repair is unclear.

Moreover, MRG15 is involved in the DNA damage response by recruiting the BRCA complex to DNA damage sites and in regulation of homologous recombination during DNA damage repair via an interaction with PALB2 [33, 34, 50]. A study revealed that meiotic cells expressing mutants of the MRG15 and BRCA2 C. elegans orthologues exhibit accumulation of human replication protein-1 (RPA-1) nuclear foci and aberrant chromosomal compactions [36]. Studies have shown that cells with MRG15 deficiency exhibit impaired homology-directed DNA damage repair, but the results are somewhat controversial [33, 34]. Sy et al. proposed that in the gene conversion assay, MRG15-binding-defective PALB2 mutants alleviated the repression of sister chromatid exchange, leading to hyperrecombination, while damage-induced RAD51 foci formation and mitomycin C sensitivity (MMC) remained relatively normal in cells expressing these mutants. Depletion of MRG15 had no influence on the expression level of the BRCA2 protein but promoted gene conversion. This suggests that the PALB2-MRG15 interaction is vital for the inhibition of sister chromatid-mediated homologous recombination [33]. From another perspective, Hayakawa et al. demonstrated that MRG15 was needed for DNA damage repair by homologous recombination and for resistance to MMC. Notably, depletion of MRG15 resulted in a decrease in BRCA2 stability and disruption of the interaction of BRCA2 with chromatin and affected the recruitment of BRCA2 and RAD51 in a manner independent of the MRG15-PALB2 interaction [34]. Interestingly, a recent study explored the novel role of the MRG15-Ash1L complex upon UV irradiation [45]. MRG15 activates the H3K4 methyltransferase activity of Ash1L, assisting the XPC and TFIIH complex in navigating damaged DNA and introducing genome-wide NER hotspots. This complex also recruits the histone chaperone FACT to sites of DNA damage, allowing verification of DNA damage [45]. In addition, it was discovered that MRG15 recognizes H2B ubiquitination, controls histone H4 Lys16 acetylation and chromatin relaxation and modulates ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) activation and DNA damage response pathways via MRG15-dependent acetyltransferase complexes, which are regulated by RNF8 and Chfr, two E3 ubiquitin ligases and chromatin remodellers [51, 52]. Thus, further studies are needed to explain the discrepancies and better clarify the mechanisms by which MRG15 recruits various chromatin remodelling complexes and affects the DNA damage response network.

In addition to its function in DNA damage repair, MRG15 has been demonstrated to associate with chromatin in the absence of DNA damage. During DNA replication, PALB2 interacts strongly with its binding partner MRG15 at active genes and mediates a timely and effective response to and protection against DNA damage stress through the SET2/H3K36me3/MRG15 axis [35].

MRG15 in cell proliferation and division

In vivo, MRG15 is required for embryonic survival. It was initially discovered that targeted deletion of MRG15 results in embryonic lethality and a smaller size of null embryos [53, 54], with a neural tube much thinner than that of wild-type and heterozygous embryos [55]. The Mrg15 begins to be expressed at E10.5 and continues to be highly expressed throughout embryonic development. At E14.5, Mrg15 knockout mouse embryos still had heartbeats, but their development was abnormal, manifested mainly by the smaller embryo size, and all organs of these embryos were significantly smaller than those of wild-type embryos. More importantly, the development of the cardiovascular system in Mrg15 knockout mice showed obvious pathological features. The entire embryo was paler, suggesting abnormal vascular development, and its heart developed with distinct features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, including enlarged cardiomyocytes and a disordered arrangement of myocardial fibres. The knockout mice all died after delivery, probably due to abnormal development of the autonomic circulatory system. Expression of a short-truncated form of a Drosophila MRG15 mutant or inverted repeat constructs led to reduced female fertility, larval death, and a shortened lifespan [54].

Previous studies have shown that corepressor complexes containing HDACs are vital for the determination of cell fate and the differentiation of stem/precursor cells [56–58]. As a component of HDAC complexes, MRG15 might also repress the expression of genes required for the maintenance of stemness in stem cells [55]. In vitro, compared with the corresponding wild-type controls, MRG15-deficient MEFs and neural stem and progenitor cells exhibited a limited cell proliferation ability [48, 53]. MRG15 is needed for derepression of the B-myb promoter via association with Rb through the leucine zipper motif of MRG15 or relaxation of chromatin surrounding the promoter in a manner dependent on MRG15-mediated histone acetylation [22]. MRG15 regulates the expression level of p21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that participates in the regulation of cell cycle progression. MRG15 inhibits NPC cell proliferation and migration by increasing the levels of p21 and E-cadherin, thus acting as a tumour suppressor [59]. On the other hand, significantly increased expression of p21 was observed in MRG15-null MEFs and NSCs, indicating that loss of MRG15 might potentially induce premature of p21 in these cells [53, 55]. MRG15, together with Tip60, also positively affects cell proliferation via direct activation of the cdc2 promoter through histone H4 acetylation [27]. HDAC2-dependent deacetylation of MRG15 at Lys148 enhances MRG15 homodimerization and facilitates the formation of the MRG15/Pf1/mSin3A corepressor complex to inhibit cell proliferation [60]. Thus, MRG15 appears to be involved in cell proliferation predominantly via transcriptional regulation of cell cycle factors through chromatin remodelling, constituting an intricate regulatory network, largely due to interactions with different histone modification enzymes at specific genes to drive their activation or repression.

Notably, MRG15 also plays a crucial role in cell differentiation, which is supported by the observation that Mrg15-null embryonic neural stem and progenitor cells show impaired self-renewal and neuronal differentiation capacities in vitro compared with those of the control cells [55]. Increased recruitment of MRG15 was observed during the induced differentiation of mouse erythroleukaemia (MEL) cells. MRG15 influences the expression of haemoglobin [53]. In addition, MRG-1 (homologue of MRG15 in C. elegans) is synthesized predominantly in oocytes and is required for the formation of normal primordial germ cells (PGCs) with the potential to initiate mitotic proliferation during postembryonic development [61]. By binding to RING finger protein (RFP-1), MRG-1 controls the extent of stem cell proliferation as well as the balance between proliferation and differentiation in a manner independent of the canonical spatially regulated GLP-1/Notch signalling pathway in the C. elegans germline [62].

Moreover, the functions of MRG15 are precisely regulated by alternative splicing during development [63, 64]. Two alternative splice variants of MRG15 mRNA have been observed; these encode two MRG15 isoforms: a short isoform (S-MRG15) with a complete chromodomain and a long isoform (L-MRG15) with an insertion in or near the chromodomain. The two variants perform different functions in retinogenesis: S-Morf4l1 mediates the transition from progenitor to differentiated cells, while L-Morfl1 shows no significant effect on phenotype [63]. Additionally, MRG15 colocalizes with splicing factors polypyrimidine tract binding proteins 1/2 (PTBP1/2) at H3K36me3 sites between the exons and the single intron of transition nuclear protein 2 (Tnp2). Spermatogenesis in the Mrg15-null testis is arrested at the round spermatid stage in the absence of meiotic division and histone acetylation, partially due to defective pre-mRNA splicing of Tnp2, a specific germ cell gene. This proves the essential role of MRG15 in pre-mRNA splicing during spermatogenesis [64]. Given the above observations, MRG15 might mediate cell division through pre-mRNA alternative splicing via histone modifications in association with other splicing factors.

MRG15 in cell senescence and apoptosis

MORF4, another member of the MRG family and a truncated form of MRG15, is widely recognized as a cellular senescence-inducing gene that causes termination of division in immortalized cells assigned to complementation group B for indefinite division [3, 4]. Transfection of a chromodomain-deleted MRG15 construct, which mimics MORF4, was found to lead to disruption of MAF2 and variations in the expression of genes related to senescence, resulting in a nonproliferative state in cells [3]. A large CRISPR-based screen in human primary dermal fibroblasts identified an important role of MRG15 in cellular senescence. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is a characteristic of cellular senescence and affects the tissue and cell microenvironment, tumorigenesis and age-related diseases [65]. Disrupting MRG15 neutralized the elevated expression of SASP genes in the bypass cells, consequently leading to distinctive cell fates because of senescence bypass. The screen also indicated that MRG15 might share a similar mechanism with mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) to modulate the SASP through IL1A and NF-κB [66].

Downregulation of MRG15 has been observed in senescent human fibroblasts compared to young proliferating fibroblasts, while overexpression of MRG15 and/or MRGX in presenescent cells leads to cell cycle re-entry in these cells, as evidenced by the increased number of BrdU-positive cells [67]. It is worth noting that Pf1, a partner of MRG15, can prevent premature cellular senescence. Inactivation of Pf1 results in the upregulation of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal), a marker of cellular senescence, and the effect of Pf1 on nucleolar functions might be mediated partially by its association with the MRG15/Pf1/Sin3 HDAC complex [68]. In addition, cellular senescence can be triggered by the accumulation of irreparable DNA damage [69]. Given that MRG15 is responsible for DNA damage repair, MRG15 might affect the process of cellular ageing via interactions with its partners (such as Tip60 and PALB2), which are involved in the DNA damage response. However, the concrete regulatory mechanism of MRG15 in cellular senescence is far from clear, and more research should be done to explain the relationships between MRG15 and SASP genes.

MRG15 binds to Rb and pcd17 and thereby increases E2F-responsive B-myb promoter activity, providing evidence for understanding the pathogenesis of PCD [23]. Notably, E2F expression has been demonstrated to be sufficient to promote neuronal apoptosis, and Rb can protect neurons from apoptosis [23, 70]. Therefore, in consideration of the close relationship between MRG15 and the Rb-E2F system, further investigations remain to be conducted to determine whether MRG15 is related to the initiation and progression of PCD.

Although MRG15-deficient neural precursor cells showed an impaired proliferation ability, and no increase in the number of apoptotic cells was observed during in vitro culture [55], overexpression of S-Morf4l, a short isoform of MRG15, led to disruption of the layering and integral structure of the chicken retina, as well as increased apoptosis in the infected area. The phenotype is potentially due to cell cycle arrest and subsequent apoptosis triggered by erroneous or forced chromatin changes [63]. In HeLa cells, MRG15 acts as a nuclear ligand for Agrocybe aegerita lectin (AAL), a fungal galectin that possesses nuclear migration activity and apoptosis-induced activity dependent on nuclear localization, in which the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) is essential for the interaction between AAL and MRG15 [71]. MRG15 is constantly expressed at low levels in the lung due to its continuous degradation mediated by an orphan ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, Fbxl18, and the expression of MRG15 is upregulated in both patients and animal models infected with pneumonia. MRG15 plays a role in the pathogenesis of pneumonia via the mediation of epithelial cell apoptosis [72]. Overall, MRG15 seems to be involved in cell apoptosis in a direct or indirect way, while how it precisely exerts pro-apoptosis activity and the factors that control its abundance in cells still need more research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biological functions of MRG15 and its cofactors.

| Physiological or pathological process | Cofactor | Function | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous recombination and DNA damage repair | MRG15/Tip60 | Acetylating nucleosomal phospho-H2Av post ionizing radiation exposure and promoting DNA damage repair | [38] |

| MRG15/PALB2 | Recruiting repair factors to DNA damage sites, increasing chromatin accessibility and stimulating homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks | [33, 34] | |

| MRG15 | Recognizing H2B ubiquitination, acetylating H4K16 and inducing chromatin relaxation, thus facilitating ATM activation and the DNA damage response | [52] | |

| MRG15/Ash1L | Facilitating H3K4me3 across the genome, assisting XPC and TFIIH in navigating along chromatin and recruiting the histone chaperone FACT to DNA lesions | [45] | |

| Response to DNA stress during DNA replication | MRG15/PALB2 | Protecting active genes from DNA stress during DNA replication through the SETD2/H3K36me3/MRG15 axis | [35] |

| Cell proliferation | MRG15/Rb | Promoting the activation of B-myb promoter and facilitating cell proliferation | [22] |

| MRG15 | Inhibiting cell proliferation and migration by increasing the expression levels of p21 and E-cadherin | [53, 55, 59] | |

| MRG15/Tip60 | Facilitating the acetylation of H4 and activating the cdc2 promoter, thus promoting cell cycle progression | [27] | |

| MRG15/Pf1/mSin3A | Inhibiting cell proliferation caused by HDAC2-dependent MRG15 homodimerization | [60] | |

| Cell differentiation | MRG15/RFP-1 | Controlling stem cell proliferation and the balance between proliferation and differentiation | [62] |

| mRNA alternative splicing | MRG15/PTB | Recognizing H3K36me3, recruiting the PTB splicing factor and regulating pre-mRNA alternative splicing | [64, 97] |

| Apoptosis | MRG15 | Promoting cell cycle re-entry in presenescent cells | [67] |

| MRG15/AAL | Regulating AAL’s proapoptotic activity as a nuclear ligand (MRG15) | [71] | |

| MRG15 | Mediating apoptosis when MRG15 is protected from ubiquitination by Fbxl18 | [72] |

PALB2 partner and localizer of BRCA2; ATM ataxia telangiectasia mutated; TFIIH Transcription Factor IIH; FACT Facilitates Chromatin Transcription; Rb retinoblastoma tumour suppressor; HDAC histone deacetylase; Pf1 plant homeodomain zinc finger protein; RFP-1 RING finger protein; PTB polypyrimidine tract binding protein; H3K36me3 H3 lysine 36 trimethylation; AAL Agrocybe aegerita lectin; TFIIH Transcription Factor IIH.

MRG15 expression regulation

MRG15 is constitutively highly expressed in most cells, and its expression is regulated in different ways. The mRNA level of MRG15 is downregulated by CUG repeats caused by stress through the RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR)-ph-eIF2α pathway in type 1 myotonic dystrophy (DM1) [73]. The molecular functionality and stability of MRG15 have been revealed to be regulated by different posttranslational modifications. MRG15 is an unstable protein whose half-life is approximately 30 min. Its endogenous protein level has been demonstrated to be degraded by the ubiquitin‒proteasome [62, 72, 74]. In-depth proteomic analysis indicated that the endogenous protein level of MRG15 is highly regulated by the ubiquitin‒proteasome system [74]. MRG15 is a substrate of a Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase (CRL), which is responsible for the process of ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of many cellular proteins [75]. Studies conducted in C. elegans demonstrated that the orthologue of MRG15, known as MRG-1, interacts with the E3 ligase containing a RING domain called RFP-1. Inhibition of the proteasome results in an increased level of MRG-1 [62]. Fbxl18 forms a complex with MRG15, thus facilitating its polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation [72]. K104 and K187 (or K143, the corresponding site in mice) have been demonstrated to be the sites of ubiquitylation in MRG15 [72, 74]. The ubiquitylation level of MRG15 at K104 and K187 decreases upon proteasome inhibition [74]. Furthermore, bacterial infection [72] and inflammatory cytokines produced during nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) progression [76] can upregulate K143 acetylation of MRG15, significantly enhancing its self-stability. HDAC2 interacts with MRG15 and is necessary for deacetylation of MRG15 at K148. The deacetylation status enhances MRG15 homodimerization, thereby facilitating MRG15 corepressor complex formation to inhibit cell proliferation [60]. MRG15 can also be methylated by NTMT1 (N-terminal methyltransferase 1) at the N-terminus, which is modulated by N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader, writer, and eraser proteins [77]. Meanwhile, in C. elegans, modification by the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO), also known as SUMOylation, affects the chromatin-binding dynamics of MRG-1 in a posttranslational way [78]. With increasing attention given to the molecular function of MRG15, transcription factors or signal transduction pathways regulating MRG15 expression need to be further explored (Table 2).

Table 2.

Posttranslational modifications of MRG15.

| Posttranslational modification | Mechanism | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination | (C. elegans) RFP1 interacts with MRG-1 and facilitates its proteasomal activity. | [62] |

| Fbxl18 interacts with MRG15 and mediates its ubiquitination at K143. | [72] | |

| The ubiquitination level of MRG15 at K104 and K187 decreases upon proteasome inhibition. | [74] | |

| Acetylation | GCN5 binds to MRG15, acetylating and stabilizing MRG15. | [72] |

| Inflammatory cytokines produced during NASH progression increase the acetylation level of MRG15. | [76] | |

| Deacetylation | HDAC2 interacts with MRG15, deacetylating MRG15 at K148 and enhancing its homodimerization. | [60] |

| Methylation | NTMT1 methylates MRG15 at the N-terminus. | [77] |

| SUMOylation | (C. elegans) SUMO associates with MRG-1 and affects the chromatin-binding dynamics of MRG-1. | [78] |

RFP-1 RING finger protein; GCN5 general control nonderepressible 5; NASH nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; HDAC2 histone deacetylase 2; NTMT1 N-terminal methyltransferase 1; SUMO small ubiquitin-like modifier.

MRG15 and diseases

MRG15 in cancer

Notably, it has been confirmed by RT–PCR that the mRNA expression of MRG15 is significantly downregulated in different types of cancer, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma and breast, colon, and lung cancers, suggesting that the expression of MRG15 is related to cancer initiation or progression. The low level of MRG15 may be due to the increased methylation of the MRG15 promoter in most cancer tissues compared with normal tissues [59, 79]. Mutation analysis of MRG15 in families with BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer and BRCA1/2 mutation carriers showed no clear evidence that structural changes in MRG15 may increase the risk of breast cancer [36, 39, 80]. Through oligonucleotide single-nucleotide polymorphism studies and mRNA expression array analyses to identify candidate cancer-related genes in a cohort of patients with primary breast cancer, MRG15 was detected in regions with a decreased chromosomal copy number and was considered a candidate tumour suppressor gene [79]. In addition, in CD49f+/EpCAM-, CD44+/CD24-, and CD271+ cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) that were isolated from breast milk obtained from patients with breast cancer, MRG15 was found to have gained an insertion that led to premature termination of its transcription [81]. Breast cancer-related mutations in PALB2, which interacts with BRCA1 and BRCA2 to activate DNA damage repair and mediate genome stability, cause only a minor decrease in the MRG15-PALB2 binding affinity [16, 82, 83]. In a genomic analysis of breast cancer patients, only the c.1919C>A (p.S640X) mutation of PALB2 was detected. This mutation resulted in an abnormal structure in the C-terminal domain, inducing an alteration in the MRG15–PALB2 interaction and loss of the interactions of PALB2 with RAD51 and BRCA2 [80]. However, whether the interaction between MRG15 and PALB2 affects the progression of cancer remains to be confirmed.

MRG15 plays a role in tumour cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [19, 59, 84, 85]. MRG15 increases the expression levels of p21 and E-cadherin to inhibit cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion in NPC [59]. As a nuclear ligand for the fungal galectin AAL, MRG15 plays a key role in antitumour activity via the modulation of apoptosis in HeLa cells [71]. In lung cancer, MRG15 associates with PTBP, a key factor required for FGFR-2 alternative splicing, at an H3K36me3-modified site generated by SETD2. Downstream of phosphorylation of IWS1 (an RNA processing regulator), PTB and H3K36me3-binding MRG15 coregulate FGFR-2 splicing in an Akt isoform-dependent phosphorylation pathway, mediating the proliferative and invasive phenotype of tumour cells [85]. In prostate cancer cells, MRG15 can regulate H3K4me1/3 modification of MRGBP to recruit TIP60 and acetylate histone variant H2A.Z at sites of AR binding, leading to the activation of AR-associated enhancers and promoters [19]. Taken together, MRG15 can potentially change the histone modification status of target genes in tumour cells through an epigenetic mechanism, thus mediating cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. MRG15 is considered either a tumour suppressor gene or a negative regulator in different types of cancer.

Moreover, MRG15 might be a specific marker for the diagnosis of cancers. In a recent study, an RNA ratio-based prediction model consisting of eight plasma extracellular vehicle (EV)-derived RNAs (FBXO7, MRG15, DDX17, TALDO1, AHNAK, TUBA1B, CD44, and SETD3) was developed, and this model contributes to the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [86]. Therefore, MRG15 potentially participates in different biological processes of cancer and in different types of cancer. It will be of great importance to elucidate the detailed role of MRG15 in cancer progression based on clinical studies.

MRG15 in liver and lung diseases

Epithelial cell death through an undefined mechanism is the pathogenic basis of pneumonia. The expression of MRG15 is elevated in patients with pneumonia and in lung epithelia when exposed to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or lipopolysaccharide. MRG15 results in lung epithelial cell death, therefore playing a vital role in the development of pneumonia. Moreover, an MRG15 antagonist, argatroban, has been demonstrated to inhibit MRG15-dependent histone acetylation, reduce MRG15 cytotoxicity and increase the survival rate of mice with lung infection. Argatroban, an FDA-approved thrombin inhibitor, was identified by computational analysis with molecular docking software, and the concentration at which it directly inhibited MRG15 cytotoxicity was found to be lower than those at which it is used as an anticoagulant. This reveals that MRG15 might be a potential molecular target for nonantibiotic medical treatment of severe pulmonary infections [72].

In addition to the role MRG15 may play in lung diseases, its function in the liver was first elucidated by Ding’s team in the last 2 years [47, 76]. A genome-wide systematic characterization revealed that MRG15 acts as a critical chromatin remodeller in the liver and rhythmically activates lipid metabolic genes and lipid synthesis. Blocking MRG15 has been shown in animal studies to attenuate high-fat diet (HFD)-induced hepatic steatosis and improve liver metabolism [47]. Simple hepatic steatosis is the primary feature of nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), the early stage of nonalcoholic fatty disease (NAFLD). During the progression from NAFLD to its advanced stage called NASH, the liver is characterized by increasing lesion severity, including inflammation and fibrosis [87]. The level of MRG15 is elevated in the livers of human patients and mice with NASH. The study also shows that mitochondrial MRG15 interacts with Tu translation elongation factor, mitochondrial (TUFM), and influences the acetylation status and stability of TUFM, resulting in impaired mitophagy, addictive oxidative stress and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway [76]. Given the clinical application of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-conjugated small interfering RNA (siRNA) gene therapy targeted to the liver [88], it is speculated that targeting MRG15 with siRNAs might be a potential gene therapy for NASH.

Despite the research mentioned above, studies focusing on MRG15’s function in lung and liver diseases are limited. As a consequence, future studies can expand the different roles of MRG15 in these organs.

MRG15 in nervous system diseases

MRG15 is localized in dendrites and in the nuclei of Purkinje cells, mediating synaptic activity and gene expression [89, 90]. MRG15 is associated with some age-related neurodegenerative disorders [23, 55, 66]. GSEA showed that MRG15 exhibited consistent downregulation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease [66]. An early study revealed that immunostaining of MRG15 overlapped significantly with that of phosphorylated tau in hippocampal tissue samples from patients with histopathologically confirmed AD compared with age-matched controls without AD [55, 91]. Additionally, MRG15 has been demonstrated to bind to pcd17, derepressing the B-myb promoter and consequently influencing the survival of Purkinje neurons. It has been confirmed that derepression of the B-myb promoter is related to neuronal apoptosis. Anti-Purkinje cell (anti-Yo) antibodies have been shown to derepress the B-myb promoter in the presence of pcd17 and MRG15. This study provides evidence for understanding the pathogenesis of PCD [55]. Thus, more research remains to be done in the future to uncover the roles of MRG15 in neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The roles of MRG15 in physiological and pathological processes.

The pie chart shows that MRG15 plays important roles in embryonic development and progression of multiple diseases, such as cancer, pneumonia, NASH and the neurodegenerative disorder Alzheimer’s disease. The figure was created with BioRender under a paid subscription (Agreement number: BP2619NB1L).

Summary and prospects

In summary, MRG15 plays vital roles in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodelling; is widely involved in homologous recombination, DNA damage repair, cell proliferation and division, senescence, and apoptosis; and has a function in many diseases. Although MRG15 is evolutionally important and widely expressed, few studies have reported the downstream targets of MRG15. Moreover, it is worth noting that MRG15 rhythmically regulates hepatic lipid metabolism and actively interacts with the canonical core clock. Therefore, MRG15 might affect lipidosis and lipolysis and potentially control the balance between glucose and insulin—two important regulators of lipid metabolism—and might participate in the pathophysiological processes related to diabetes. The mechanisms by which MRG15 regulates the peripheral biological clock, leading to rhythmic changes in other organs, are also worth exploring. Evidently, MRG15 plays a vital role in neuronal activity. However, whether and how MRG15 is related to neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, remains unknown. And further studies might provide evidence to address these diseases. In addition, the gene ADAMTS7 has been revealed to be related to coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodelling via cleavage of thrombospondin-1 [92–94], while several genome-wide association studies have identified a coronary artery disease (CAD)-associated locus, ADAMTS7 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 7)-MORF4L1 (MRG15) on 15q25, with a newly identified single-nucleotide polymorphism rs4380028 located in the first intron of MRG15 [92, 95, 96]. Thus, it can be supposed that MRG15 might contribute to the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases, but further studies are needed to elucidate the relationships and mechanisms.

It is clear that MRG15 may mediate diverse regulatory mechanisms of gene activation and repression via epigenetic modifications in different cell types, especially via mechanisms related to its involvement in nuclear protein complexes and interactions with specific histone modification enzymes (such as HAT and HDAC). However, how MRG15 subtly regulates and maintains the balance between regulatory activation and repression remains to be further addressed. Argatroban, an MRG15 antagonist that inhibits MRG15-dependent histone acetylation, has been demonstrated to alleviate pulmonary infection and hepatic steatosis. And since the expression of MRG15 is regulated by different posttranslational modifications, strategies that modulate MRG15 expression by means such as enhancing its degradation or increasing its stability, might reveal new insights into disease treatment. More importantly, given the roles of MRG15 in diverse physiological and pathological processes, therapies to manipulate the expression of MRG15 must be strictly controlled depending on the specific organ or disease state.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by General Program of Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (22ZR1415100), the Major Program (82220108020, 92068202) of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (20XD1400600). We apologize to all those whose work we have been unable to include due to space limitations.

Data availability

The following PDB datasets were used in Fig. 1: 8C60, 2F5J, 2F5K. Mentioned PDB structural datasets are publicly available free of charge. Figure 4 was created with BioRender.com (Agreement number: BP2619NB1L).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Dan Meng, Email: dmeng@fudan.edu.cn.

Xiu-ling Zhi, Email: zhixiuling@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bertram MJ, Pereira-Smith OM. Conservation of the MORF4 related gene family: identification of a new chromo domain subfamily and novel protein motif. Gene. 2001;266:111–21. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertram MJ, Berube NG, Hang-Swanson X, Ran Q, Leung JK, Bryce S, et al. Identification of a gene that reverses the immortal phenotype of a subset of cells and is a member of a novel family of transcription factor-like genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1479–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.2.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tominaga K, Tominaga E, Ausserlechner MJ, Pereira-Smith OM. The cell senescence inducing gene product MORF4 is regulated by degradation via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung JK, Pereira-Smith OM. Identification of genes involved in cell senescence and immortalization: potential implications for tissue ageing. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;235:105–10. doi: 10.1002/0470868694.ch10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tominaga K, Matzuk MM, Pereira-Smith OM. MrgX is not essential for cell growth and development in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4873–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4873-4880.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tominaga K, Leung JK, Rookard P, Echigo J, Smith JR, Pereira-Smith OM. MRGX is a novel transcriptional regulator that exhibits activation or repression of the B-myb promoter in a cell type-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49618–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo WY, Wu CY, Hwu L, Lee JS, Tsai CH, Lin KP, et al. Enhancement of tumor initiation and expression of KCNMA1, MORF4L2 and ASPM genes in the adenocarcinoma of lung xenograft after vorinostat treatment. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8663–75. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kooblall KG, Stokes VJ, Shariq OA, English KA, Stevenson M, Broxholme J, et al. miR-3156-5p is downregulated in serum of MEN1 patients and regulates expression of MORF4L2. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2022;29:557–68. doi: 10.1530/ERC-22-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tominaga K, Pereira-Smith OM. The genomic organization, promoter position and expression profile of the mouse MRG15 gene. Gene. 2002;294:215–24. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang P, Zhao J, Wang B, Du J, Lu Y, Chen J, et al. The MRG domain of human MRG15 uses a shallow hydrophobic pocket to interact with the N-terminal region of PAM14. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2423–34. doi: 10.1110/ps.062397806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadlec J, Hallacli E, Lipp M, Holz H, Sanchez-Weatherby J, Cusack S, et al. Structural basis for MOF and MSL3 recruitment into the dosage compensation complex by MSL1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:142–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie T, Zmyslowski AM, Zhang Y, Radhakrishnan I. Structural basis for multi-specificity of MRG domains. Structure. 2015;23:1049–57. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie T, Graveline R, Kumar GS, Zhang Y, Krishnan A, David G, et al. Structural basis for molecular interactions involving MRG domains: implications in chromatin biology. Structure. 2012;20:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowman BR, Moure CM, Kirtane BM, Welschhans RL, Tominaga K, Pereira-Smith OM, et al. Multipurpose MRG domain involved in cell senescence and proliferation exhibits structural homology to a DNA-interacting domain. Structure. 2006;14:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan MSM, Muhammad R, Koliopoulos MG, Roumeliotis TI, Choudhary JS, Alfieri C. Mechanism of assembly, activation and lysine selection by the SIN3B histone deacetylase complex. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2556. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redington J, Deveryshetty J, Kanikkannan L, Miller I, Korolev S. Structural insight into the mechanism of PALB2 interaction with MRG15. Genes (Basel) 2021;12:2002. doi: 10.3390/genes12122002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang P, Du J, Sun B, Dong X, Xu G, Zhou J, et al. Structure of human MRG15 chromo domain and its binding to Lys36-methylated histone H3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6621–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eissenberg JC. Structural biology of the chromodomain: form and function. Gene. 2012;496:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito S, Kayukawa N, Ueda T, Taniguchi H, Morioka Y, Hongo F, et al. MRGBP promotes AR-mediated transactivation of KLK3 and TMPRSS2 via acetylation of histone H2A.Z in prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2018;1861:794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar GS, Chang W, Xie T, Patel A, Zhang Y, Wang GG, et al. Sequence requirements for combinatorial recognition of histone H3 by the MRG15 and Pf1 subunits of the Rpd3S/Sin3S corepressor complex. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:519–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung JK, Berube N, Venable S, Ahmed S, Timchenko N, Pereira-Smith OM. MRG15 activates the B-myb promoter through formation of a nuclear complex with the retinoblastoma protein and the novel protein PAM14. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39171–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pardo PS, Leung JK, Lucchesi JC, Pereira-Smith OM. MRG15, a novel chromodomain protein, is present in two distinct multiprotein complexes involved in transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50860–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakai K, Kitagawa Y, Saiki S, Saiki M, Hirose G. Effect of a paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration-associated neural protein on B-myb promoter activity. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:529–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jelinic P, Pellegrino J, David G. A novel mammalian complex containing Sin3B mitigates histone acetylation and RNA polymerase II progression within transcribed loci. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:54–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00840-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayakawa T, Ohtani Y, Hayakawa N, Shinmyozu K, Saito M, Ishikawa F, et al. RBP2 is an MRG15 complex component and down-regulates intragenic histone H3 lysine 4 methylation. Genes Cells. 2007;12:811–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar GS, Xie T, Zhang Y, Radhakrishnan I. Solution structure of the mSin3A PAH2-Pf1 SID1 complex: a Mad1/Mxd1-like interaction disrupted by MRG15 in the Rpd3S/Sin3S complex. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peña AN, Tominaga K, Pereira-Smith OM. MRG15 activates the cdc2 promoter via histone acetylation in human cells. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:1534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia SN, Kirtane BM, Podlutsky AJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Tominaga K. Mrg15 null and heterozygous mouse embryonic fibroblasts exhibit DNA-repair defects post exposure to gamma ionizing radiation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng X, Cote J. A new companion of elongating RNA Polymerase II: TINTIN, an independent sub-module of NuA4/TIP60 for nucleosome transactions. Transcription. 2014;5:e995571. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2014.995571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyon Y, Selleck W, Lane WS, Tan S, Cote J. Structural and functional conservation of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex from yeast to humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1884–96. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1884-1896.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gowher H, Brick K, Camerini-Otero RD, Felsenfeld G. Vezf1 protein binding sites genome-wide are associated with pausing of elongating RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121538109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devoucoux M, Roques C, Lachance C, Lashgari A, Joly-Beauparlant C, Jacquet K, et al. MRG proteins are shared by multiple protein complexes with distinct functions. Mol Cell Proteom. 2022;21:100253. doi: 10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sy SM, Huen MS, Chen J. MRG15 is a novel PALB2-interacting factor involved in homologous recombination. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21127–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayakawa T, Zhang F, Hayakawa N, Ohtani Y, Shinmyozu K, Nakayama J, et al. MRG15 binds directly to PALB2 and stimulates homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1124–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bleuyard JY, Fournier M, Nakato R, Couturier AM, Katou Y, Ralf C, et al. MRG15-mediated tethering of PALB2 to unperturbed chromatin protects active genes from genotoxic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:7671–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620208114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martrat G, Maxwell CM, Tominaga E, Porta-de-la-Riva M, Bonifaci N, Gómez-Baldó L, et al. Exploring the link between MORF4L1 and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R40. doi: 10.1186/bcr2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murr R, Loizou JI, Yang YG, Cuenin C, Li H, Wang ZQ, et al. Histone acetylation by Trrap-Tip60 modulates loading of repair proteins and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:91–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusch T, Florens L, Macdonald WH, Swanson SK, Glaser RL, Yates JR, 3rd, et al. Acetylation by Tip60 is required for selective histone variant exchange at DNA lesions. Science. 2004;306:2084–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1103455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frio TRio, Haanpaa M, Pouchet C, Pylkas K, Vuorela M, Tischkowitz M, et al. Mutation analysis of the gene encoding the PALB2-binding protein MRG15 in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer families. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:842–3. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmahling S, Meiler A, Lee Y, Mohammed A, Finkl K, Tauscher K, et al. Regulation and function of H3K36 di-methylation by the trithorax-group protein complex AMC. Development. 2018;145:dev163808. doi: 10.1242/dev.163808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C, Yang F, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Cai G, Li L, et al. Mrg15 stimulates Ash1 H3K36 methyltransferase activity and facilitates Ash1 Trithorax group protein function in Drosophila. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1649. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01897-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou P, Huang C, Liu CP, Yang N, Yu T, Yin Y, et al. Structural insights into stimulation of Ash1L’s H3K36 methyltransferase activity through Mrg15 binding. Structure. 2019;27:837–45. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee Y, Yoon E, Cho S, Schmahling S, Muller J, Song JJ. Structural basis of MRG15-mediated activation of the ASH1l histone methyltransferase by releasing an autoinhibitory loop. Structure. 2019;27:846–52. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Harthi S, Li H, Winkler A, Szczepski K, Deng J, Grembecka J, et al. MRG15 activates histone methyltransferase activity of ASH1L by recruiting it to the nucleosomes. Structure. 2023;31:1200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2023.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maritz C, Khaleghi R, Yancoskie MN, Diethelm S, Brulisauer S, Ferreira NS, et al. ASH1L-MRG15 methyltransferase deposits H3K4me3 and FACT for damage verification in nucleotide excision repair. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3892. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39635-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moshkin YM, Kan TW, Goodfellow H, Bezstarosti K, Maeda RK, Pilyugin M, et al. Histone chaperones ASF1 and NAP1 differentially modulate removal of active histone marks by LID-RPD3 complexes during NOTCH silencing. Mol Cell. 2009;35:782–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei Y, Tian C, Zhao Y, Liu X, Liu F, Li S, et al. MRG15 orchestrates rhythmic epigenomic remodelling and controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Nat Metab. 2020;2:447–60. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen M, Pereira-Smith OM, Tominaga K. Loss of the chromatin regulator MRG15 limits neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation via increased expression of the p21 Cdk inhibitor. Stem Cell Res. 2011;7:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Utley RT, Lacoste N, Jobin-Robitaille O, Allard S, Cote J. Regulation of NuA4 histone acetyltransferase activity in transcription and DNA repair by phosphorylation of histone H4. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8179–90. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8179-8190.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pauty J, Rodrigue A, Couturier A, Buisson R, Masson J-Y. Exploring the roles of PALB2 at the crossroads of DNA repair and cancer. Biochem J. 2014;460:331–42. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moyal L, Lerenthal Y, Gana-Weisz M, Mass G, So S, Wang SY, et al. Requirement of ATM-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2B for timely repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell. 2011;41:529–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu J, Chen Y, Lu LY, Wu Y, Paulsen MT, Ljungman M, et al. Chfr and RNF8 synergistically regulate ATM activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:761–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tominaga K, Kirtane B, Jackson JG, Ikeno Y, Ikeda T, Hawks C, et al. MRG15 regulates embryonic development and cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2924–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.2924-2937.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang H, Li Y, Yang J, Tominaga K, Pereira-Smith OM, Tower J. Conditional inactivation of MRG15 gene function limits survival during larval and adult stages of Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:825–33. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen M, Takano-Maruyama M, Pereira-Smith OM, Gaufo GO, Tominaga K. MRG15, a component of HAT and HDAC complexes, is essential for proliferation and differentiation of neural precursor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1522–31. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Humphrey GW, Wang YH, Hirai T, Padmanabhan R, Panchision DM, Newell LF, et al. Complementary roles for histone deacetylases 1, 2, and 3 in differentiation of pluripotent stem cells. Differentiation. 2008;76:348–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuzmochka C, Abdou HS, Hache RJG, Atlas E. Inactivation of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) but not HDAC2 is required for the glucocorticoid-dependent CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBP alpha) expression and preadipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4762–73. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Streubel G, Fitzpatrick DJ, Oliviero G, Scelfo A, Moran B, Das S, et al. Fam60a defines a variant Sin3a-Hdac complex in embryonic stem cells required for self-renewal. EMBO J. 2017;36:2216–32. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sang Y, Zhang R, Sun L, Chen KK, Li SW, Xiong L, et al. MORF4L1 suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion by increasing p21 and E-cadherin expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:294–302. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Y, Li J, Dunn S, Xiong S, Chen W, Zhao Y, et al. Histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) protein-dependent deacetylation of mortality factor 4-like 1 (MORF4L1) protein enhances its homodimerization. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7092–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujita M, Takasaki T, Nakajima N, Kawano T, Shimura Y, Sakamoto H. MRG-1, a mortality factor-related chromodomain protein, is required maternally for primordial germ cells to initiate mitotic proliferation in C. elegans. Mech Dev. 2002;114:61–9. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta P, Leahul L, Wang X, Wang C, Bakos B, Jasper K, et al. Proteasome regulation of the chromodomain protein MRG-1 controls the balance between proliferative fate and differentiation in the C. elegans germ line. Development. 2015;142:291–302. doi: 10.1242/dev.115147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boije H, Ring H, Shirazi Fard S, Grundberg I, Nilsson M, Hallbook F. Alternative splicing of the chromodomain protein Morf4l1 pre-mRNA has implications on cell differentiation in the developing chicken retina. J Mol Neurosci. 2013;51:615–28. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwamori N, Tominaga K, Sato T, Riehle K, Iwamori T, Ohkawa Y, et al. MRG15 is required for pre-mRNA splicing and spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E5408–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611995113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coppe JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol-Mech. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Wei L, Dong Q, Liu L, Zhang MQ, Xie Z, et al. A large-scale CRISPR screen and identification of essential genes in cellular senescence bypass. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:4011–31. doi: 10.18632/aging.102034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen M, Tominaga K, Pereira-Smith OM. Emerging role of the MORF/MRG gene family in various biological processes, including aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1197:134–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Graveline R, Marcinkiewicz K, Choi S, Paquet M, Wurst W, Floss T, et al. The chromatin-associated Phf12 protein maintains nucleolar integrity and prevents premature cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2017;37:e00522–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00522-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Di Micco R, Sulli G, Dobreva M, Liontos M, Botrugno OA, Gargiulo G, et al. Interplay between oncogene-induced DNA damage response and heterochromatin in senescence and cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:292–302. doi: 10.1038/ncb2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu DX, Greene LA. Regulation of neuronal survival and death by E2F-dependent gene repression and derepression. Neuron. 2001;32:425–38. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liang Y, Lin JC, Wang K, Chen YJ, Liu HH, Luan R, et al. A nuclear ligand MRG15 involved in the proapoptotic activity of medicinal fungal galectin AAL (Agrocybe aegerita lectin) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zou C, Li J, Xiong S, Chen Y, Wu Q, Li X, et al. Mortality factor 4 like 1 protein mediates epithelial cell death in a mouse model of pneumonia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:311ra171. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huichalaf C, Sakai K, Jin B, Jones K, Wang GL, Schoser B, et al. Expansion of CUG RNA repeats causes stress and inhibition of translation in myotonic dystrophy 1 (DM1) cells. FASEB J. 2010;24:3706–19. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Porras-Yakushi TR, Reitsma JM, Sweredoski MJ, Deshaies RJ, Hess S. In-depth proteomic analysis of proteasome inhibitors bortezomib, carfilzomib and MG132 reveals that mortality factor 4-like 1 (MORF4L1) protein ubiquitylation is negatively impacted. J Proteom. 2021;241:104197. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liao H, Liu XJ, Blank JL, Bouck DC, Bernard H, Garcia K, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of cellular protein modulation upon inhibition of the NEDD8-activating enzyme by MLN4924. Mol Cell Proteom. 2011;10:M111.009183. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tian C, Min X, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Wu X, Liu S, et al. MRG15 aggravates non-alcoholic steaohepatitis progression by regulating the mitochondrial proteolytic degradation of TUFM. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bade D, Cai Q, Li L, Yu K, Dai X, Miao W, et al. Modulation of N-terminal methyltransferase 1 by an N6-methyladenosine-based epitranscriptomic mechanism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;546:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baytek G, Blume A, Demirel FG, Bulut S, Popp O, Mertins P, et al. SUMOylation of the chromodomain factor MRG-1 in C. elegans affects chromatin-regulatory dynamics. Biotechniques. 2022;73:5–17. doi: 10.2144/btn-2021-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen W, Salto-Tellez M, Palanisamy N, Ganesan K, Hou Q, Tan LK, et al. Targets of genome copy number reduction in primary breast cancers identified by integrative genomics. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:288–301. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vietri MT, Caliendo G, Schiano C, Casamassimi A, Molinari AM, Napoli C, et al. Analysis of PALB2 in a cohort of Italian breast cancer patients: identification of a novel PALB2 truncating mutation. Fam Cancer. 2015;14:341–8. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9786-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhat-Nakshatri P, Kumar B, Simpson E, Ludwig KK, Cox ML, Gao H, et al. Breast cancer cell detection and characterization from breast milk-derived cells. Cancer Res. 2020;80:4828–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quinet A, Vindigni A. Superfast DNA replication causes damage in cancer cells. Nature. 2018;559:186–7. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hashimoto Y, Ray Chaudhuri A, Lopes M, Costanzo V. Rad51 protects nascent DNA from Mre11-dependent degradation and promotes continuous DNA synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1305–11. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kadamb R, Leibovitch BA, Farias EF, Dahiya N, Suryawanshi H, Bansal N, et al. Invasive phenotype in triple negative breast cancer is inhibited by blocking SIN3A-PF1 interaction through KLF9 mediated repression of ITGA6 and ITGB1. Transl Oncol. 2022;16:101320. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanidas I, Polytarchou C, Hatziapostolou M, Ezell SA, Kottakis F, Hu L, et al. Phosphoproteomics screen reveals akt isoform-specific signals linking RNA processing to lung cancer. Mol Cell. 2014;53:577–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qin D, Zhao Y, Guo Q, Zhu S, Zhang S, Min L. Detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by a qPCR-based normalizer-free circulating extracellular vesicles RNA signature. J Cancer. 2021;12:1445–54. doi: 10.7150/jca.50716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018;24:908–22. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schlegel MK, Janas MM, Jiang Y, Barry JD, Davis W, Agarwal S, et al. From bench to bedside: Improving the clinical safety of GalNAc-siRNA conjugates using seed-pairing destabilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:6656–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matsuoka Y, Matsuoka Y, Shibata S, Ban T, Toratani N, Shigekawa M, et al. A chromodomain-containing nuclear protein, MRG15 is expressed as a novel type of dendritic mRNA in neurons. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:299–308. doi: 10.1016/S0168-0102(02)00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hajduskova M, Baytek G, Kolundzic E, Gosdschan A, Kazmierczak M, Ofenbauer A, et al. MRG-1/MRG15 is a barrier for germ cell to neuron reprogramming in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2019;211:121–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raina AK, Pardo P, Rottkamp CA, Zhu X, Pereira-Smith OM, Smith MA. Neurons in Alzheimer disease emerge from senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;123:3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reilly MP, Li MY, He J, Ferguson JF, Stylianou IM, Mehta NN, et al. Identification of ADAMTS7 as a novel locus for coronary atherosclerosis and association of ABO with myocardial infarction in the presence of coronary atherosclerosis: two genome-wide association studies. Lancet. 2011;377:383–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kessler T, Zhang L, Liu ZY, Yin XK, Huang YQ, Wang YB, et al. ADAMTS-7 inhibits re-endothelialization of injured arteries and promotes vascular remodeling through cleavage of thrombospondin-1. Circulation. 2015;131:1203–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bauer RC, Tohyama J, Cui J, Cheng L, Yang J, Zhang X, et al. Knockout of Adamts7, a novel coronary artery disease locus in humans, reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2015;131:1202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.C. Coronary Artery Disease Genetics. A genome-wide association study in Europeans and South Asians identifies five new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:339–44. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luco RF, Pan Q, Tominaga K, Blencowe BJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science. 2010;327:996–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1184208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The following PDB datasets were used in Fig. 1: 8C60, 2F5J, 2F5K. Mentioned PDB structural datasets are publicly available free of charge. Figure 4 was created with BioRender.com (Agreement number: BP2619NB1L).