Highlights

-

•

An inhibitor of Aurora kinase A, Alisertib, surprisingly depletes primary cilia across multiple patient GBM cell lines and in patient biopsy tissues treated ex vivo.

-

•

Alisertib does not deplete normal neuron or astrocyte primary cilia.

-

•

Alisertib-induced depletion of GBM cilia is in part mitigated by chloroquine, an autophagy inhibitor.

-

•

TTFields plus Alisertib suppress GBM cell proliferation beyond either treatment alone.

-

•

TTFields plus Alisertib suppression of GBM cell proliferation is cilia-independent.

Keywords: Tumor Treating Fields, AURKA, AURKB, Primary cilium, Autophagy, ARL13B, Glioblastoma

Abstract

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) extend the survival of glioblastoma (GBM) patients by interfering with a broad range of tumor cellular processes. Among these, TTFields disrupt primary cilia stability on GBM cells. Here we asked if concomitant treatment of TTFields with other agents that interfere with GBM ciliogenesis further suppress GBM cell proliferation in vitro. Aurora kinase A (AURKA) promotes both cilia disassembly and GBM growth. Inhibitors of AURKA, such as Alisertib, inhibit cilia disassembly and increase ciliary frequency in various cell types. However, we found that Alisertib treatment significantly reduced GBM cilia frequency in gliomaspheres across multiple patient derived cell lines, and in patient biopsies treated ex vivo. This effect appeared glioma cell-specific as it did not reduce normal neuronal or glial cilia frequencies. Alisertib-mediated depletion of glioma cilia appears specific to AURKA and not AURKB inhibition, and attributable in part to autophagy pathway activation. Treatment of two different GBM patient-derived cell lines with TTFields and Alisertib resulted in a significant reduction in cell proliferation compared to either treatment alone. However, this effect was not cilia-dependent as the combined treatment reduced proliferation in cilia-depleted cell lines lacking, ARL13B, or U87MG cells which are naturally devoid of ARL13B+ cilia. Thus, Alisertib-mediated effects on glioma cilia may be a useful biomarker of drug efficacy within tumor tissue. Considering Alisertib can cross the blood brain barrier and inhibit intracranial growth, our data warrant future studies to explore whether concomitant Alisertib and TTFields exposure prolongs survival of brain tumor-bearing animals in vivo.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) therapy is the latest approved therapeutic option for glioblastoma (GBM). TTFields are low intensity (1–3 V/cm), intermediate frequency (200 kHz) alternating electric fields applied across the tumor through a wearable headset array. When combined with standard of care chemotherapeutic temozolomide (TMZ), overall GBM patient survival is prolonged by 4–5 months [1]. How this synergism works remains unclear because TTFields engages a wide range of anti-tumor mechanisms on cells [2]. Recently we reported that one cellular target affected by TTFields is the primary cilium of tumor cells in vitro and ex vivo [3]. Primary cilia are microtubule-based organelles that are gaining increasing attention on GBM cells [4,5]. For example, cilia are linked to glioma cell stemness [6], angiogenesis [7] and chemoresistance [3,[8], [9], [10]]. In addition, our group and others have found that TMZ promotes the formation of primary cilia on GBM cells [3,9,10]. Ablating glioma cilia genetically or with TTFields lowered resistance to TMZ [3,[8], [9], [10]]. This led us to explore whether targeting other tumor cell pathways essential for ciliogenesis could further enhance the effects of TTFields.

One critical regulator of ciliogenesis is AURKA [11], a molecule that has been extensively characterized in promoting GBM growth and treatment resistance. AURKA is frequently overexpressed in GBM compared to control and other brain tumor subtypes, and an inhibitor of AURKA, Alisertib (MLN8237), exhibits potent toxicity against numerous GBM lines [12], [13], [14]. Notably, Alisertib can prolong in vivo survival of animals implanted intracranially with glioma cells [15], [16], [17], [18]. Thus, the drug can cross the blood brain barrier and penetrate intracranial tumor tissue reaching concentrations of up to ∼1000 nmol/L [15]. The drug also synergizes with TMZ to reduce proliferation in vitro [14]. Inhibitors of AURKA, including Alisertib, have reached clinical trials for various cancers including GBM [19,20], although the drug's clinical success has not yet delivered the same anti-tumor benefits as observed in preclinical studies.

AURKA controls numerous downstream cellular events [19,21]. One major aspect of the cell cycle regulated by AURKA function is to drive primary cilia disassembly [11,[22], [23], [24]]. Disassembling the primary cilium is an essential step for cells to exit G1 and re-purpose their centrioles for spindle pole formation during G2/M phase. Inhibiting AURKA activity with Alisertib can prevent cilia disassembly and as a result stabilize or increase the frequency of ciliogenesis. For example, Alisertib increased the frequency of cilia in human retinal pigmented epithelial cells (ARPE-19) and human diploid fibroblasts (WI-38) [25,26]. Furthermore, Alisertib restored the frequency of primary cilia in Panc1 cells (a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line) [27] and more recently, it restored cilia in supratentorial RELA ependymal cells [28].

To our knowledge, nobody has examined whether or how Alisertib affects GBM cilia, and if it does, whether this treatment could potentially work in concert with TTFields. In this study, we sought to determine whether Alisertib affects the frequency of GBM cilia, and whether these effects could render cells more susceptible to the tumor cell killing effects by TTFields.

Results

Inhibiting AURKA via Alisertib reduces the frequency of primary cilia in GBM cell lines and biopsies treated ex vivo

We first explored the effect of Alisertib on cilia frequency in gliomaspheres of our patient GBM-derived lines L0 and R24–3. Gliomaspheres were selected because they display more stemlike characteristics than adherent cultures of glioma cells [29], and because our previous study showed TTFields disrupt cilia within spheres [3]. Cells were treated with either vehicle, 1uM or 4uM Alisertib for 24hr. These initial concentrations were selected as they approximate physiologic levels measured in brain, tumor and plasma [15]. After 24hr, we fixed, and immunolabeled cryosections of the spheres for pericentriolar material 1 (PCM1, a protein which concentrates around centrioles and ciliary basal bodies) and ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 13B (ARL13B, which enriches along the primary cilia membrane). We then calculated the number of cilia/sphere area. Surprisingly, we observed a marked loss of ARL13B+ cilia in both GBM cell lines (Fig. 1A-C, E-G). Quantification of the results showed significant reduction of the density of ARL13B+ cilia in treated L0 (Fig. 1D) and R24–3 (Fig. 1H) spheres. We observed a similar effect in our S7 cell line spheres (Suppl. Fig. 1), suggesting the phenomena may extend to lower grade glioma cells. The IC50 of Alisertib in GBM cells has been reported to range from ∼3–225 nM depending on whether glioma cells were grown as adherent or spheres [12,30]. Some studies have reported that the Alisertib's effect on increasing or stabilizing the cilia are observed with as low as 10 nM of Alisertib [27]. Thus, we also examined whether much lower concentrations (10 nM or 100 nM) increase GBM ciliogenesis. However, after 24 or 72 of treatment, we observed either lack of an effect or reduced frequencies of ARL13B+ cilia (Suppl. Fig. 2). Further, we transfected R24–3 cells with cDNA encoding OFD1:mCherry (OFD1 localizes around centrioles/basal bodies) and ARL13BWT:GFP which enriches in the cilium. We then collected timelapse images of ARL13BWT:GFP+ cilia over a 24hr period. Compared to vehicle treatment, dissolution of the cilium can be observed in cells treated with 1 µM Alisertib (Fig. 1I-K). Together, these unexpected results indicate that inhibiting AURKA, rather than increasing or stabilizing cilia, promotes destabilization or degradation of glioma cilia.

Fig. 1.

Alisertib lowers the frequency of primary cilia in patient-derived GBM spheres in vitro. Patient-derived GBM L0 (A-C) and R24–3 (E-G) gliomaspheres exposed to vehicle or different concentrations of Alisertib. Twenty-four hr later, spheres were fixed, frozen, sectioned and immunolabeled for PCM1 (red), which clusters around basal cilia bodies/centrioles, and ARL13B (green) which enriches in the primary cilium. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). The arrows in A and E spheres point to cilia enlarged in the insets. Insets show ARL13B+ cilia (arrows) with PCM1 (arrowheads) clustered around the basal body. D, H) Bar graphs show mean (+/-SEM) number of ARL13B+ cilia per sphere area (µm2) in vehicle or Alisertib-treated cells. For L0, n = 47 (veh), 40 (1 µM Alis), and 26 (4 µm Alis) spheres/group. For R24–3, n = 27 (veh), 34 (1 µM Alis), and 35 (4 µM Alis) spheres/group. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (ANOVA). I-K) Live imaging of R24–3 cells transiently co-transfected with cDNA encoding ARL13BWT:EGFP (which labels the cilium (arrow)) and OFD1:mCherry (which clusters around the ciliary base (arrowhead)). Twenty-four to 48hr after transfection cells were timelapse imaged for about 20–30 min at baseline (BL). Cells were then treated with either vehicle (I) or 1 µM Alisertib (J, K) and imaged every 10–15 min up to 22 hr later. Note the loss of ARL13B+ cilia (brackets in J and K) at 15.8 and 22 hr later, respectively. Scale bars (µm) in G (representing panels A-G) = 20, I (representing all timelapse images in I-K) = 5.

In addition to ciliary changes, we observed accompanying mitotic abnormalities in the spheres. Previous studies on human GBM cells showed that potent AURKA inhibition significantly increase cell and nuclear size, produce abnormal mitoses, and cell cycle arrest [12,18]. Because phosphorylation of histone H3 is critical for mitosis onset, and AURKA physically interacts with the histone H3 tail and phosphorylates Ser10 [19], we also examined the extent of phospho-histone H3(Ser10)+ cells in our spheres and levels by western blot. Within spheres treated with 1 or 4 µM Alisertib, there were significantly fewer p-HH3(Ser10)+ nuclei compared to vehicle (Suppl. Fig. 3). Further, Alisertib-treated L0 or R24–3 spheres displayed reduced p-HH3(Ser10) protein by western blot (Suppl. Fig. 3). These observations indicate significant mitotic arrest which could contribute to ciliary depletion after Alisertib treatment.

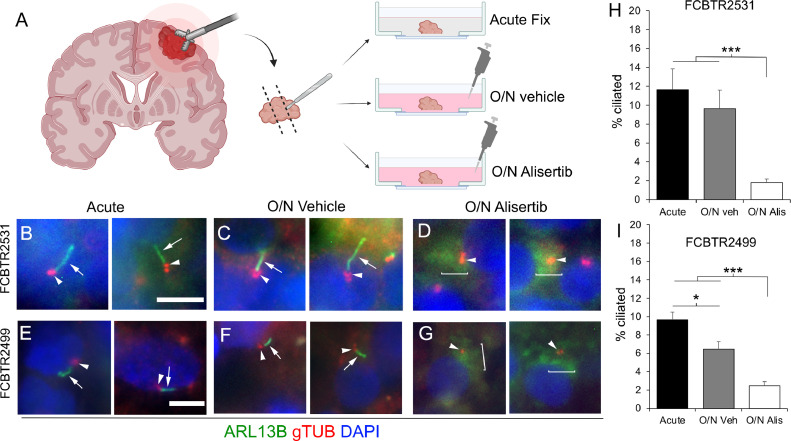

We next wondered if Alisertib could have the same influence on cilia in ex-vivo cultured GBM patient biopsies. To that end, two pathology-confirmed GBM biopsies were subdissected into 3 groups: acute fixation, overnight vehicle, or overnight in 1 µM Alisertib (Fig. 2A). All groups were fixed, frozen, cryosection and immunolabeled for gamma-tubulin (which labels the tubulin isoform comprising centrioles/basal bodies) and ARL13B to label the cilium. While we readily observed ARL13B+ cilia in tissues that were acutely fixed (Fig. 2B, E) and overnight control (Fig. 2C, F), cilia frequency was reduced in Alisertib-treated specimens (Fig. 2D, G). Quantification of these results showed significant loss of cilia compared to controls in both Alisertib-treated specimens (Fig. 2H,I).

Fig. 2.

Alisertib disrupts ciliogenesis in GBM patient biopsies treated ex vivo. A) Ex-vivo treatment of surgical resections. Biopsies were dissected and separated into acute fix, overnight (O/N) vehicle or O/N Alisertib (1uM) treatment. B-G) Tissues were fixed, frozen, cryosectioned and immunostained for ARL13B (green, arrows) and gTub (red, arrowheads) which labels the ciliary basal body. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Two examples of acute fix (B,E), overnight vehicle (C,F) or overnight Alisertib (D,G) from two different patients are shown. Brackets in D and G show diffuse ‘clouds’ of ARL13B signal surrounding gTUB+ centrioles/basal bodies. H, I) Percent of ciliated cells from indicated patient samples in the indicated group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 (ANOVA). Scale bars in B (representing B-D), E (representing E-G) = 10 µm. Images in A were generated using Biorender.com.

While Alisertib is a selective inhibitor of AURKA, higher concentrations of Alisertib have been reported to inhibit AURKB activity [31]. Aurora B/C kinase activity has been linked to glioma cilia disassembly(6). Therefore we wondered if the ciliary changes after Alisertib could be attributable to disruption of AURKB activity in our cell lines. We grew adherent L0 and R24–3 cells in the presence of vehicle or AURKB inhibitor, AZD1152 (Barasertib). Given that as low as 5 nM of AZD1152 significantly inhibited GBM cell proliferation in vitro [32], we used a range of 3–100 nM of AZD1152 to examine GBM ciliogenesis 24hr after treatment. While we observed changes in nuclear size/morphology/number at all AZD1152 concentrations, we observed no effect of AZD1152 on the percent of ciliated GBM cells (Suppl. Fig. 4). These results suggest an AURKA inhibitor-specific effect on glioma cilia depletion.

Alisertib does not reduce cilia frequency on neurons or glia derived from mouse cortex

Previous studies reported that Alisertib concentrations up to 800 nM do not exert appreciable toxicity on normal human astrocytes in vitro [30]. Since Alisertib dramatically reduced glioma cilia within 24 h of exposure, we asked whether cilia of normal primary neural cell types are similarly affected. To test this, we cultured dissociated mouse neonatal cortices on glass coverslips for 12 days in vitro (DIV). At 12DIV, we assigned coverslips as control (vehicle) or 1 µM Alisertib. We previously showed that these types of culture allow us to examine the effect of TTFields or drugs on cells that differentiate into various subtypes including astrocytes and neurons, marked by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neuronal nuclei (NeuN) expression respectively [3].

We first examined neuronal cilia by triple immunolabeling for NeuN, type 3 adenylyl cyclase (AC3), an enzyme enriched in most neuronal cilia in the cortex, and pericentrin (Pcnt, a protein concentrated around the cilia basal body) (Fig. 3A,B). After 24 h of Alisertib, we did not observe any significant changes on the frequency of neurons with AC3+ cilia (Fig. 3C). We next examined astrocyte cilia through a combined immunostaining for GFAP, ARL13B and Pcnt (Fig. 3D, E). However after 24 h of treatment, we did not observe significant differences in the frequency of astrocyte cilia (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that, at least at acute timepoints after Alisertib, neuronal and astrocyte cilia are less responsive to Alisertib than glioma cells.

Fig. 3.

Alisertib does not disrupt neuronal and glial cell primary cilia frequency. Mixed primary cultures from neonatal mouse cerebral cortex were dissociated and maintained for 12DIV and treated with vehicle or 1 µM Alisertib exposed for 24 h. A,B) Cells were stained for neuronal cilia marker AC3 (green, arrow) and NeuN (blue). Arrows point to AC3+ cilia in both groups. C) Percent of NeuN+ cells with AC3+ cilia. n = 332 (Veh) and 496 (Alis) neurons. D, E) Cultures were immunostained for ARL13B (green), pericentrin (Pcnt, red), and GFAP (blue). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (grey). F) Percent of GFAP+ cells with ARL13B+ cilia. n = 310 (Veh) and 407 (Alis) glial cells. Scale bar in B (representing all images) = 10 µm.

Alisertib-induced depletion of ARL13B+ GBM cilia may be due to autophagy pathway activation

In addition to mitotic arrest, we further explored a mechanism that may contribute to the unexpected loss of glioma cilia following Alisertib treatment. Previously, we found that TTFields-induced depletion of GBM primary cilia occurred in part thru activation of the autophagy pathway. Pretreating GBM spheres with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) delayed the TTFields-induced loss of cilia [3]. Likewise, Alisertib can induce autophagy in human GBM cells [13]. Thus, using our R24–3 GBM spheres, we asked whether pretreatment with CQ could prevent the Alisertib-mediated depletion of cilia. The treatment groups were: vehicle, CQ (20 µM), Alisertib (1 µM), or CQ (added 30 min prior) plus Alisertib. After 24hr treatment, we fixed, froze and immunolabeled cryosections for ARL13B (Fig. 4A-D). Quantification of the number of ARL13B+ cilia/sphere area revealed significantly higher frequency of ARL13B+ cilia in the CQ plus Alisertib group compared to Alisertib alone group (Fig. 4E). While the combination CQ plus Alisertib did not fully restore cilia frequency to that of control groups, the increase over Alisertib alone suggests Alisertib stimulation of the autophagy pathway in part triggers the depletion of GBM cilia.

Fig. 4.

Chloroquine pretreatment partially prevents the Alisertib-induced loss of cilia. (A–D) R24–3 spheres were treated with vehicle (A), 20 µM chloroquine (CQ) (B), 1 µM Alisertib (Alis), or 20 µM CQ (given 30 min prior) plus 1 µM Alis (D). Spheres were fixed after 24hr and immunostained for ARL13B (green). Nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows point to cilia observed in spheres of the indicated treatments. Scale bar in A for the respective row = 20 µm. (E) Bar graphs show mean (+/- SEM) number of ARL13B+ cilia/sphere area (µm2) in indicated treatment group. N = 54 (veh), 30 (CQ), 49 (Alis) and 50 (CQ+Alis) spheres/group. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 (ANOVA).

Alisertib with or following TTFields reduces GBM cell proliferation

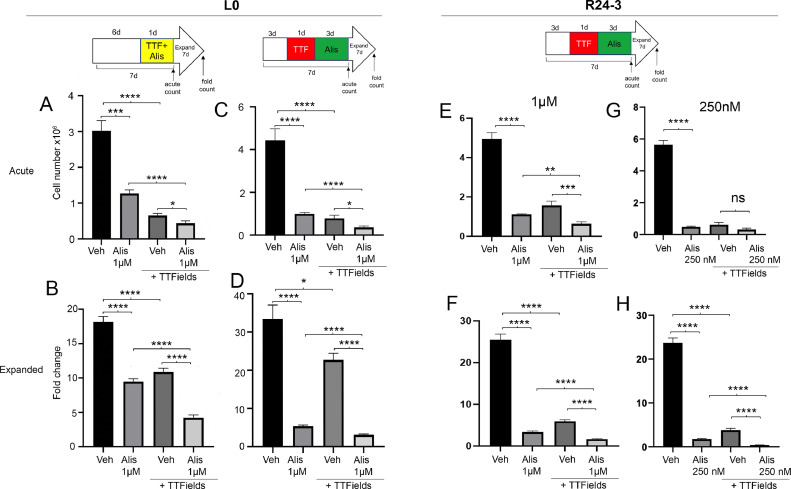

Our previous study suggested cilia may be associated with tumor cell recurrence following TTFields [3], and that suppressing ciliogenesis may help enhance TTFields efficacy. Since Alisertib reduced GBM cilia frequencies, we wondered if the two treatments may work better together. To test this, we examined L0 and R24–3 cell lines after co-treatment or sequential treatment of TTFields followed by Alisertib (see Fig. 5 top schematics for treatment schedule). The four treatment groups were: vehicle, Alisertib (1 µM), vehicle + TTFields, Alisertib + TTFields. We examined proliferation of cells at two points during the treatment schedule. First, we examined the acute total numbers (acute count) of cells immediately after last treatment (i.e. after 1 or 4 days of treatments). Second, we determined the fold expansion (or recurrence index) of cells seven days after the last treatment (fold count). For L0 cells, we found that treating cells with both Alisertib + TTFields significantly reduced cell number (Fig. 5A,C) and fold expansion (Fig. 5B,D) compared to either treatment alone, and irrespective of the treatment sequence. Similarly in R24–3 cells, Alisertib and TTFields significantly reduced both cell number (Fig. 5E) and fold expansion (Fig. 5F) of cells compared to either treatment alone. We also tested a lower concentration (250 nM) of Alisertib in which we did not find any effect of Alisertib+TTFields at the acute timepoint (Fig. 5G), but did observe significantly reduced fold expansion of cells compared to either treatment alone (Fig. 5H). We also performed a western blot of treated cell lysates to determine if TTFields itself was contributing to a reduction in phospho-AURKA like 250 nM of Alisertib. However we only observed an obvious reduction of phospho-AURKA after Alisertib exposure and not TTFields in both cell lines (Suppl. Fig. 5). Altogether, these results indicate adding Alisertib to TTFields treatment has a greater effect of inhibiting GBM cell expansion than either treatment alone.

Fig. 5.

Co- or sequential treatment of TTFields and Alisertib impair GBM cell expansion. L0 (A-D) or R24–3(E-H) cells were grown as spheres for the indicated time and then exposed to either Alisertib alone, TTFields alone or together for 1 day (A,B), or in sequence (C,D, E-H). Cells were counted immediately after treatment at 7 days (Acute count), then pooled, and 2.5 × 104 cells/well were expanded in fresh media for 7 days in 24 well plates (n = 12 wells/group) and the fold expansion was calculated (Fold count). ns =not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (ANOVA).

Alisertib and TTFields co-treatment effects persist in ARL13B-depleted and ARL13B+ cilia-lacking U87-MG GBM cells

We next asked if the effect of Alisertib and TTFields on the GBM cell proliferation in vitro is attributable to Alisertib's surprising effect on glioma cilia. To test this, we examined two different GBM cell lines lacking cilia: an L0 transgenic cell line that we previously generated by genetic depletion of ARL13B cilia using CRISPR/Cas9 [33], and a U87-MG cell line which are naturally devoid of ARL13B+ cilia [34,35]. In L0 cells, we found that Alisertib plus TTFields significantly reduces both acute cell number (Fig. 6A) and fold expansion of cells (Fig. 6B) compared to either treatment alone. Similarly, in U87-MG cells, we found that the combination of Alisertib and TTFields reduces both acute cell number (Fig. 6C) and fold expansion of cells (Fig. 6D) compared to either treatment alone. Surprisingly, U87-MG cells appear less sensitive to Alisertib alone (Fig. 6C), though it is not clear if this is associated with the cell's loss of ARL13B+ cilia, presence of serum in U87-MG cells or some other cell-type related factor. Nevertheless, these results suggest Alisertib's effects on cilia are not required to generate a combined treatment effect observed in wildtype GBM cells.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of GBM cell proliferation by TTFields and Alisertib is not cilia-dependent. L0 ARL13B KO (A,B) or naturally cilia-devoid U87-MG (C,D) cells were grown as spheres (L0) or adherent (U87-MG) for the indicated treatment schedule. Cells were counted immediately after treatment at 8 days (Acute count), then pooled, and 2.5 × 104 cells/well were expanded in fresh media for 7 days in 24 well plates (n = 12 wells/group) and the fold expansion was calculated (Fold count). ns =not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (ANOVA).

Discussion

Our data show that concomitant treatment of Alisertib and TTFields in vitro suppresses GBM cell proliferation greater than either treatment alone. This effect is not mediated via tumor primary cilia, as both deciliated and ciliated populations of GBM cells appear sensitive to the combination of treatments. To our knowledge, we are the first to show that inhibiting AURKA suppresses GBM ciliogenesis both in vitro and ex vivo using patient derived biopsies, a counterintuitive phenomenon not observed in normal mouse cortical neurons or glia. The unexpected cilia ablation, in part attributable to autophagy pathway activation, may serve as a useful readout of the drug's penetrance into GBM tumors, a possibility that requires further in vivo investigation. A limitation of the present study is that although a preclinical device for delivering TTFields to mouse intracranial tumors is in development, it is not currently available to researchers. Future studies will need to exploit this capability to validate a combined antitumor effect of TTFields and Alisertib in the brains of mice.

Significance of Alisertib effects on glioma primary cilia

Considering that AURKA plays a key role in ciliary disassembly, and GBM cells constantly assemble and disassemble their cilia while proliferating, it was surprising to not observe increased GBM cilia frequency after Alisertib treatment. It is possible that AURKA inhibition in GBM cells stimulates activity of other molecules that promote ciliary disassembly such as HDAC6, NEK and others (for review see: [22,36,37]). However, we previously reported that overexpression of HDAC6 in our L0 or S7 glioma cells did not reduce cilia frequency or length [33]. Alisertib may have a selective capacity to kill GBM cells in their ciliated state. In part this may explain why U87-MG cells were less sensitive to Alisertib alone treatment (Fig. 6C), as U87-MG cells naturally lack cilia [35]. In contrast, we found that L0 GBM cells lacking cilia were highly sensitive to Alisertib (Fig. 6A), which could be attributable to secondary downstream effects of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated depletion of ARL13B. Lee and colleagues recently found that inhibiting Aurora B/C kinases using GSK-1,070,916 increased the frequency of ciliated patient-derived glioma stem cells [6]. However, when we inhibited AURKB specifically with AZD1152, we saw no effect on the frequency of ciliated GBM cells. The difference between the two studies could be related to use of a different drug, different cell lines, or an unappreciated role of Aurora C kinase in ciliogenesis.

A likely explanation for Alisertib-triggered cilia loss comes from a combined mitotic arrest and stimulation of the autophagy pathway. The dramatic decrease in p-HH3 in Alisertib treated spheres (Suppl. Fig 3) may cause cells to get arrested or delayed through the G2/M interface(13) when cells would normally not be ciliated [38]. A previous study found that synchronized MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells persist longer in M-phase as measured by prolonged pHH3 staining several hours after TTFields exposure [39]. Though we looked at pHH3 protein expression 24hr after dual Alisertib and TTFields treatment, we still observed weak pHH3 (Suppl. Fig. 3U), suggesting Alisertib could affect the DNA, e.g. by altering reported nuclear functions of AURKA [40], or in some other way that either overrides or interferes with TTFields effects on DNA. Further, we recently showed that TTFields-induced loss of primary cilia is in part attributable to activation of autophagy [3], and considering Alisertib also induces autophagy in human GBM cells [13], it was thus not surprising that Alisertib-induced autophagy appears to partially mediate the GBM cilia depletion (Fig. 4). Thus, even though the presence of cilia was not required for combined benefit of TTFields and Alisertib to suppress proliferation, future studies should explore whether both treatments may combine to further drive autophagy, a mechanism shown to suppress glioma stem cell renewal and tumor initiation [41].

The observation that Alisertib does not depend on primary cilia to work in concert with TTFields is not surprising. Like TTFields (for review see: [2]), AURKA regulates many other cellular processes with pro-tumorigenic activity (for review see: [19]) which their inhibition by Alisertib can potentially be enhanced by concomitant application of TTFields. This raises the question of whether the ciliary disruptions we observe are relevant. First, because Alisertib suppressed ciliogenesis in cultured biopsied tissue (Fig. 2) and the drug is measurable in CSF, brain and intracranial tumors, the drug-induced loss of tumor cilia in vivo could be a potential biomarker of Alisertib activity in the tumor. Second, tumor cilia are induced by and promote resistance to standard of care TMZ treatment in vitro and in vivo [3,[8], [9], [10]]. Considering Alisertib plus TMZ has been reported more toxic during gliomagenesis than either treatment alone [14], future studies should examine how Alisertib and TTFields, which suppress ciliogenesis, interact with TMZ chemotherapy which appears to stimulate ciliogenesis.

Is the AURKA pathway a viable adjunct therapy with TTFields?

Since TTFields prolong patient survival, there are active searches for combinatorial drug targets, particularly those that interfere with tumor cell mitosis and cell survival mechanisms. Relevant to our study, an inhibitor of Aurora B kinase pathway, AZD1152 (Barasertib) displays both properties by disrupting mitosis and survival of newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM cells in vitro which is exacerbated by TTFields treatment [32]. Our in vitro data suggest similar effects may be achievable by targeting Aurora A kinase pathway, a widely studied target across cancers [19,42]. Future in vivo studies should compare Alisertib or other AURKA inhibitors with TTFields.

Although Alisertib has reached Phase 1 clinical trials for high grade glioma [20], it appears that their results have not yielded the same success as seen in preclinical studies. Some of the challenges in working with Alisertib could be related to drug-induced changes to tumor cells that may countereffect anti-tumor immunity, or that effective dosages required to reach/kill brain tumors are significantly lower than needed. For example, a recent study suggests Alisertib may induce PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, which serves to suppress anti-tumor immunity [43]. However in our hands, Alisertib did not have an appreciable effect on GBM cell PD-L1 expression by western blot (data not shown). Further, while Alisertib has been shown by multiple groups to reach the brain and slow brain tumor growth in vivo as described above, a recent study examining Alisertib penetrance into CNS suggests its distribution and concentrations are limited [44]. Supporting this observation, Alisertib treatment alone did not slow intracranial tumor growth of transplanted GL261glioma cells, but did synergize with co-treatment of Birabresib (a BET bromodomain inhibitor) to significantly extend survival[45]. Thus it is feasible that low doses of Alisertib in the brain could combine or potentiate other drug or brain targeted therapies such as TTFields. Taken together our results demonstrate a potential benefit for concomitant application of TTFields and Alisertib and warrants further investigation in vivo possibly with concurrent use of other GBM clinically relevant drugs.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human L0 (grade IV glioblastoma from a 43 year old male) and S7(grade II glioma from a 54 year old female) cell lines were isolated and maintained as previously described [46], [47], [48], [49]. R24–03 cell lines were expanded from a 91year old male GBM. Human U87-MG (Cat# HTB-14) cells were obtained from ATCC (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and maintained in recommended media conditions. L0, R24–3, and S7 cells were grown as floating spheres and maintained in NeuroCult NS-A Proliferation medium and 10 % proliferation supplement (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Cat# 05,750 and #05,753), 1 % penicillin–streptomycin (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat# 15,140,122), 20 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (hEGF) (Cat #78,006), and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (STEMCELL Technologies; Cat #78,003). For S7 cells, the media was supplemented with 2 μg/ml heparin (STEMCELL Technologies; Cat #07,980). When cells reached confluency, or spheres reached approximately 150 μm in diameter, they were enzymatically dissociated by digestion with Accumax (Innovative Cell Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA; Cat#AM-105) for 10 min at 37 °C. For human cells grown on glass coverslips, NeuroCult NS-A Proliferation medium was supplemented with 10 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA; Cat #SH30070.03HI). All cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Where indicated, indicated cell lines were treated with Alisertib (Selleckchem.com; Houston, TX, USA; Cat# S1133), or AZD1152 (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ USA; Cat # HY-10,127) which were dissolved in 100 % DMSO (Fisher Scientific; Cat # D128–500), and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (4 % PFA) after indicated treatment durations and processed as described below.

Primary neural cultures were obtained and grown as previously described [3]. Briefly, acutely micro-dissected C57/BL6 mouse cortices from postnatal day 0–2 pups were dissected into Gey's Balanced Salt Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat #G9779) at ∼37 °C under oxygenation for ∼20 min. Dissociated cells were triturated with pipettes of decreasing bore size, pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 3–5 min, and resuspended and plated in glial medium containing DMEM (Cytiva HyClone, Cat# SH3002201), FBS (Gemini BioProducts, West Sacramento, CA, USA; Cat# 50–753–2981), insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 15,500), Glutamax (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA;Cat# 35,050,061) and Penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Cat# 15,140,122). Cells were plated at a density of 80,000 cells/coverslip on 12-mm glass coverslips coated with 0.1 mg/ml poly-d-lysine followed by 5 μg/ml laminin in minimal essential medium. After approximately 2 hrs, cells were supplemented with 2 mL neuronal media containing Neurobasal A (Gibco, Cat# 10,888,022) supplemented with B27 (Gibco, Cat# A3582801), Glutamax (Gibco, 35,050,061), Kynurenic acid (Sigma Aldrich, Cat# K3375), and GDNF (Sigma Aldrich, Cat# SRP3200). Every 4 days, half of the media was replaced with fresh neuronal media as described above but lacking kynurenic acid and GDNF. On DIV12, coverslips were treated with vehicle or Alisertib and fixed in 4 % PFA after 24 hrs.

Ex-vivo culture and Alisertib treatment

In accordance with our institutional IRB protocol (#201902489), we collected fresh, surgically-resected tumor biopsies that were subsequently pathologically confirmed. Within one hour of the resection, biopsies were taken to the laboratory, and dissected into several pieces using a sterile scalpel blade. Tissues were immediately fixed and/or transferred into 2 mL of S7 media for culture at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 and treated with vehicle or Alisertib, and fixed 24hr later in 4 % PFA.

TTFields application

Adherent cells (U87-MG) or spheres (L0, R24–3) were placed in TTFields ceramic dishes, each dish approximately 25 mm in diameter, and mounted onto inovitro™ base plates (Novocure Ltd., Haifa, Israel). The base plates were connected to a power generator which delivered TTFields at frequency of 200 kHz at a target intensity of 1.62 V/cm [50]. Treatment duration are as indicated, ranging from 24 to 72 h for a single treatment. To prevent media evaporation during TTFields application, parafilm was placed over each TTFields ceramic dish. Control samples were grown in 6 well plates. Data in each TTFields experiment were technical replicates and pooled from at least 6–8 dishes per condition and per timepoint.

Cell proliferation assessment

We examined proliferation of cells at two points during our treatment schedules. First, we calculated acute numbers of cells immediately after last treatment (i.e., after 1 or 4 days of treatment(s)). Total cell counts from each condition were collected using a Bio-Rad TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Second, we examined the fold expansion (or recurrence index) of cells seven days after the last treatment by seeding cells (2.5 × 104) in 500 μl of growth media per well in 24-well plates for each experimental group (n = 12 wells per group). After 7 days, cells were enzymatically dissociated and resuspended in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and counted. Mean fold changes +/- SEM were plotted and compared to vehicle-treated controls. Data were analyzed statistically using one-way ANOVA using Prism (v9.5.1).

Timelapse imaging

For timelase imaging, we plated 50,000 cells in R24–3 media supplemented with 5 % FBS into 35 mm glass bottom culture dishes (Ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany; cat #81,158) which were maintained at 37 °C in 5 % CO2. Twenty four hours before imaging at about 70 % confluency, cells were transfected with 500 ng total cDNA/dish of pDest-Arl13b:GFP (a kind gift from T. Caspary, Emory University) and pCMV-myc/mCherry:hOFD1 (Vectorbuilder.com, vector ID: VB201119–1128fyp) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA, USA; cat#L3000015). Imaging was conducted on an inverted Zeiss AxioObserver D1 microscope using a Zeiss 40 × /0.95 plan Apochromat air objective. The microscope stage was equipped with a Tokai Hit stage incubation system that maintained a humid environment and stage temperature of 37 °C and 5 % CO2. After approximate 30 min of baseline images were obtained, vehicle/drug treatment was applied and images were acquired every 5 min for up to 24hours. Exposure times ranged in duration from 400 to 750msec (EGFP) and 300–400 msec (Cy3) per image. Image acquisition and processing were performed using Zeiss ZEN software (ZEN 2012 (Blue edition) v1.1.2.0).

Western blot

Western blot was performed as recently described [35]. Briefly, cells were harvested at indicated time points and lysed in 1x cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc, Danvers, MA, USA; Cat#9803) or 1 × radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Cell Signaling; Cat# 501,015,489) containing 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat# P2850), phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; Cat# P5726), and 2 (Sigma; Cat# P0044), and 1 × phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma; Cat# 93,482). Prior to loading, samples were heated to 70 °C for 10 min. A total of 25–30 μg of total protein lysate per lane were separated on 4–12 % Bis-Tris gels (Thermofisher; Cat# NP0050). Proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes using iBlot (program 3 for 8 min; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Blots were blocked in 5 % nonfat dry milk (NFDM) or bovine serum albumin (BSA, Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA, USA; Cat# NC9871802) in 1 × tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1 % Tween (TBST) for 20 min and then incubated in primary antibodies in 2.5 % NFDM or BSA in 1 × TBST for 24 h at 4 °C. Primary antibodies included rabbit anti-Aurora A (D3E4Q) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#14,475), rabbit anti-phospho-Aurora A(Thr288)/AuroraB(Thr232)/Aurora C(Thr198) (D13A11) (1:2000)(Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#2914), rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (1:2000; Millipore, Cat# 06–570), and mouse anti-beta-actin (1:10,000; Sigma; Cat #A5316), Blots were rinsed and probed in the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 30 min at RT in 2.5 % NFDM or BSA in 1 × TBST. Finally, blots were rinsed in 1 × TBS and developed using an Amersham ECL chemiluminescence kit (Global Life Sciences Solutions USA, Marlborough, MA, USA), and images were captured using an AlphaInnotech Fluorchem Q Imaging System (Protein Simple, San Jose, CA, USA). Selected areas surrounding the predicted molecular weight of the protein of interest were extracted from whole blot images.

Immunostaining

For immunocytochemical (ICC) and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses, samples were fixed at indicated timepoints with 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (4 % PFA) for 30 min for 15minutes (ICC) to 1 hour (IHC) and washed with 1x PBS. Spheres or biopsies were cryoprotected in 30 % sucrose in PBS followed by a 1:1: 30 % sucrose and optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (Fisher Healthcare, #4585), frozen in OCT over liquid N2 and cryosectioned at 16 µm. Samples were stained for the indicated primary antibodies: mouse anti-gamma Tub (1:3000; Sigma; Cat# T6557), mouse anti-ARL13B (1:3000; Abcam, Waltham, MA USA; Cat# AB136648), rabbit anti-ARL13B (1:3000; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL USA; Cat # 17,711–1-AP), chicken anti-GFAP (1:1000; Encor Biotechnology, Gainesville, FL USA; Cat# CPCA-GFAP), rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (1:3000; Millipore, Cat# 06–570), rabbit anti-pericentrin (1:1000; Covance; Cat #: PRB-432C), chicken anti-type 3 adenylyl cyclase (1:5000; Encor Biotechnology; Cat# CPCA-ACIII), and rabbit anti-PCM1 (1:1000; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX; Cat# A301–150A). Samples were incubated in blocking solution containing 5 % normal donkey serum (NDS) (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA; Cat#NC9624464) and 0.2 % Triton-X 100 in 1x PBS for 1 hour and then incubated in primary antibodies with 2.5 % NDS and 0.1 % Triton-X 100 in 1x PBS either for 2 h at room temperature (RT) or overnight at 4 °C. Appropriate FITC-, Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) in 2.5 % NDS with 1x PBS were applied for 1–2 hour at RT, and coverslips were mounted onto Superfrost™ Plus coated glass slides (Fisher Scientific, cat # 12–550–15) in Prolong Gold antifade media containing DAPI (Thermofisher; Cat# P36935). Stained coverslips were examined under epifluorescence using an inverted Zeiss AxioObserver D1 microscope using a Zeiss 40 × /0.95 plan Apochromat air objective or a Zeiss 63X/1.4 plan Apochromat oil objective. Images were captured and analyzed using Zeiss ZEN software (ZEN 2012 (Blue edition) v1.1.2.0).

For analyses of neuronal and glial cell cilia frequency, we counted the number of NeuN+ cells bearing AC3+ cilia, and number of GFAP+ cells bearing ARL13B+ cilia in each image. Images were collected from at least 3 coverslips per treatment group. For analyses of frequencies of ARL13B+ cilia or phospho-histone H3(Ser10)+ cells in gliomaspheres, we determined the sphere area by tracing DAPI-labeled spheres using a line tool in Zeiss ZEN software, and counted the number of ARL13B+ cilia, or pHH3(Ser10)+ nuclei, within each sphere. For analysis of ex-vivo cultures of patient biopsies, for each image (13–23 images/group) we calculated the total number of DAPI+ nuclei and ARL13B+ cilia.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prizm 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Comparisons between groups were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis. In all analyses, p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jia Tian: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Julianne C. Mallinger: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Ping Shi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Dahao Ling: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Loic P. Deleyrolle: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Min Lin: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Habibeh Khoshbouei: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Matthew R. Sarkisian: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The work is in part supported by Novocure Inc. The corresponding author is a consultant for Novocure Inc.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Florida Center for Brain Tumor Research for providing surgically resected tissue. Funding for this research was supported by a 2022 AACR-Novocure Tumor Treating Fields Research Grant (#22–60–62-SARK) (to M.R.S), and a National Institutes of Health grant (1R21NS131636) (to M.R.S).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101956.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Stupp R., Taillibert S., Kanner A., Read W., Steinberg D., Lhermitte B., Toms S., Idbaih A., Ahluwalia M.S., Fink K., Di Meco F., Lieberman F., Zhu J.J., Stragliotto G., Tran D., Brem S., Hottinger A., Kirson E.D., Lavy-Shahaf G., Weinberg U., Kim C.Y., Paek S.H., Nicholas G., Bruna J., Hirte H., Weller M., Palti Y., Hegi M.E., Ram Z. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:2306–2316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karanam N.K., Story M.D. An overview of potential novel mechanisms of action underlying Tumor Treating Fields-induced cancer cell death and their clinical implications. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021;97:1044–1054. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2020.1837984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi P., Tian J., Ulm B.S., Mallinger J.C., Khoshbouei H., Deleyrolle L.P., Sarkisian M.R. Tumor Treating Fields suppression of ciliogenesis enhances temozolomide toxicity. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.837589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Satta M., Matheu A. Primary cilium and glioblastoma. Ther Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018;10 doi: 10.1177/1758835918801169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkisian M.R., Semple-Rowland S.L. Emerging roles of primary cilia in glioma. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:55. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee D., Gimple R.C., Wu X., Prager B.C., Qiu Z., Wu Q., Daggubati V., Mariappan A., Gopalakrishnan J., Sarkisian M.R., Raleigh D.R., Rich J.N. Superenhancer activation of KLHDC8A drives glioma ciliation and hedgehog signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI163592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L., Xie X., Wang T., Xu L., Zhai Z., Wu H., Deng L., Lu Q., Chen Z., Yang X., Lu H., Chen Y.G., Luo S. ARL13B promotes angiogenesis and glioma growth by activating VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling. Neuro. Oncol. 2022;25:871–885. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoang-Minh L., Deleyrolle L., Nakamura N., Parker A., Martuscello R., Reynolds B., Sarkisian M. PCM1 depletion inhibits glioblastoma cell ciliogenesis and increases cell death and sensitivity to temozolomide. Transl. Oncol. 2016;9:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shireman J.M., Atashi F., Lee G., Ali E.S., Saathoff M.R., Park C.H., Savchuk S., Baisiwala S., Miska J., Lesniak M.S., James C.D., Stupp R., Kumthekar P., Horbinski C.M., Ben-Sahra I., Ahmed A.U. De novo purine biosynthesis is a major driver of chemoresistance in glioblastoma. Brain. 2021;144:1230–1246. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei L., Ma W., Cai H., Peng S.P., Tian H.B., Wang J.F., Gao L., He J.P. Inhibition of ciliogenesis enhances the cellular sensitivity to temozolomide and ionizing radiation in human glioblastoma cells. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2022;35:419–436. doi: 10.3967/bes2022.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugacheva E.N., Jablonski S.A., Hartman T.R., Henske E.P., Golemis E.A. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell. 2007;129:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehman N.L., O'Donnell J.P., Whiteley L.J., Stapp R.T., Lehman T.D., Roszka K.M., Schultz L.R., Williams C.J., Mikkelsen T., Brown S.L., Ecsedy J.A., Poisson L.M. Aurora A is differentially expressed in gliomas, is associated with patient survival in glioblastoma and is a potential chemotherapeutic target in gliomas. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:489–502. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.3.18996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z., Wang F., Zhou Z.W., Xia H.C., Wang X.Y., Yang Y.X., He Z.X., Sun T., Zhou S.F. Alisertib induces G(2)/M arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR- and p38 MAPK-mediated pathways in human glioblastoma cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017;9:845–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiao W., Guo B., Zhou H., Xu W., Chen Y., Liang Y., Dong B. miR-124 suppresses glioblastoma growth and potentiates chemosensitivity by inhibiting AURKA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;486:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kogiso M., Qi L., Braun F.K., Injac S.G., Zhang L., Du Y., Zhang H., Lin F.Y., Zhao S., Lindsay H., Su J.M., Baxter P.A., Adesina A.M., Liao D., Qian M.G., Berg S., Muscal J.A., Li X.N. Concurrent inhibition of neurosphere and monolayer cells of pediatric glioblastoma by Aurora A inhibitor MLN8237 predicted survival extension in PDOX models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:2159–2170. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurokawa C., Geekiyanage H., Allen C., Iankov I., Schroeder M., Carlson B., Bakken K., Sarkaria J., Ecsedy J.A., D'Assoro A., Friday B., Galanis E. Alisertib demonstrates significant antitumor activity in bevacizumab resistant, patient derived orthotopic models of glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2017;131:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sak M., Williams B.J., Zumbar C.T., Teer L., Al-Kawaaz M.N.G., Kakar A., Hey A.J., Wilson M.J., Schier L.M., Chen J., Lehman N.L. The CNS-penetrating taxane drug TPI 287 potentiates antiglioma activity of the AURKA inhibitor alisertib in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2023;91:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s00280-023-04503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Brocklyn J.R., Wojton J., Meisen W.H., Kellough D.A., Ecsedy J.A., Kaur B., Lehman N.L. Aurora-A inhibition offers a novel therapy effective against intracranial glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5364–5370. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du R., Huang C., Liu K., Li X., Dong Z. Targeting AURKA in cancer: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for Cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20:15. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01305-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song A., Andrews D.W., Werner-Wasik M., Kim L., Glass J., Bar-Ad V., Evans J.J., Farrell C.J., Judy K.D., Daskalakis C., Zhan T., Shi W. Phase I trial of alisertib with concurrent fractionated stereotactic re-irradiation for recurrent high grade gliomas. Radiother. Oncol. 2019;132:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mou P.K., Yang E.J., Shi C., Ren G., Tao S., Shim J.S. Aurora kinase A, a synthetic lethal target for precision cancer medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021;53:835–847. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00635-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doornbos C., Roepman R. Moonlighting of mitotic regulators in cilium disassembly. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021;78:4955–4972. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plotnikova O.V., Nikonova A.S., Loskutov Y.V., Kozyulina P.Y., Pugacheva E.N., Golemis E.A. Calmodulin activation of Aurora-A kinase (AURKA) is required during ciliary disassembly and in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:2658–2670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez I., Dynlacht B.D. Cilium assembly and disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:711–717. doi: 10.1038/ncb3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVaul N., Koloustroubis K., Wang R., Sperry A.O. A novel interaction between kinase activities in regulation of cilia formation. BMC Cell Biol. 2017;18:33. doi: 10.1186/s12860-017-0149-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffries E.P., Di Filippo M., Galbiati F. Failure to reabsorb the primary cilium induces cellular senescence. FASEB J. 2019;33:4866–4882. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801382R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi T., Nakazono K., Tokuda M., Mashima Y., Dynlacht B.D., Itoh H. HDAC2 promotes loss of primary cilia in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:334–343. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Almeida Magalhaes T., Alencastro Veiga Cruzeiro G., Ribeiro de Sousa G., Englinger B., Fernando Peinado Nagano L., Ancliffe M., Rodrigues da Silva K., Jiang L., Gojo J., Cherry Liu Y., Carline B., Kuchibhotla M., Pinto Saggioro F., Kazue Nagahashi Marie S., Mieko Oba-Shinjo S., Andres Yunes J., Gomes de Paula Queiroz R., Alberto Scrideli C., Endersby R., Filbin M.G., Silva Borges K., Salic A., Gonzaga Tone L., Valera E.T. Activation of Hedgehog signaling by the oncogenic RELA fusion reveals a primary cilia-dependent vulnerability in supratentorial ependymoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2023;25:185–198. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J., Kotliarova S., Kotliarov Y., Li A., Su Q., Donin N.M., Pastorino S., Purow B.W., Christopher N., Zhang W., Park J.K., Fine H.A. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong X., O'Donnell J.P., Salazar C.R., Van Brocklyn J.R., Barnett K.D., Pearl D.K., deCarvalho A.C., Ecsedy J.A., Brown S.L., Mikkelsen T., Lehman N.L. The selective Aurora-A kinase inhibitor MLN8237 (alisertib) potently inhibits proliferation of glioblastoma neurosphere tumor stem-like cells and potentiates the effects of temozolomide and ionizing radiation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;73:983–990. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manfredi M.G., Ecsedy J.A., Chakravarty A., Silverman L., Zhang M., Hoar K.M., Stroud S.G., Chen W., Shinde V., Huck J.J., Wysong D.R., Janowick D.A., Hyer M.L., Leroy P.J., Gershman R.E., Silva M.D., Germanos M.S., Bolen J.B., Claiborne C.F., Sells T.B. Characterization of Alisertib (MLN8237), an investigational small-molecule inhibitor of aurora A kinase using novel in vivo pharmacodynamic assays. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:7614–7624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krex D., Bartmann P., Lachmann D., Hagstotz A., Jugel W., Schneiderman R.S., Gotlib K., Porat Y., Robel K., Temme A., Giladi M., Michen S. Aurora B Kinase Inhibition by AZD1152 Concomitant with Tumor Treating Fields is effective in the treatment of cultures from primary and recurrent glioblastomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:5016. doi: 10.3390/ijms24055016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi P., Hoang-Minh L.B., Tian J., Cheng A., Basrai R., Kalaria N., Lebowitz J.J., Khoshbouei H., Deleyrolle L.P., Sarkisian M.R. HDAC6 signaling at primary cilia promotes proliferation and restricts differentiation of glioma cells. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:1644. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moser J.J., Fritzler M.J., Rattner J.B. Primary ciliogenesis defects are associated with human astrocytoma/glioblastoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi P., Tian J., Mallinger J., Ling D., Deleyrolle L., McIntyre J., Caspary T., Breunig J., Sarkisian M. Increasing ciliary ARL13B expression drives active and inhibitor-resistant Smoothened and GLI into glioma primary cilia. Cells. 2023;12:2354. doi: 10.3390/cells12192354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel M.M., Tsiokas L. Insights into the regulation of ciliary disassembly. Cells. 2021;10:2977. doi: 10.3390/cells10112977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korobeynikov V., Deneka A.Y., Golemis E.A. Mechanisms for nonmitotic activation of Aurora-A at cilia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017;45:37–49. doi: 10.1042/BST20160142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plotnikova O.V., Pugacheva E.N., Golemis E.A. Primary cilia and the cell cycle. Methods Cell Biol. 2009;94:137–160. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)94007-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gera N., Yang A., Holtzman T.S., Lee S.X., Wong E.T., Swanson K.D. Tumor treating fields perturb the localization of septins and cause aberrant mitotic exit. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng F., Yue C., Li G., He B., Cheng W., Wang X., Yan M., Long Z., Qiu W., Yuan Z., Xu J., Liu B., Shi Q., Lam E.W., Hung M.C., Liu Q. Nuclear AURKA acquires kinase-independent transactivating function to enhance breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Nat. Comm. 2016;7:10180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao Z., Li T., Ma H., Yang Y., Zhang C., Hai L., Liu P., Yuan F., Li J., Yi L., Tong L., Wang Y., Xie Y., Ming H., Yu S., Yang X. Autophagy suppresses self-renewal ability and tumorigenicity of glioma-initiating cells and promotes Notch1 degradation. Cell Death. Dis. 2018;9:1063. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Assoro A.B., Haddad T., Galanis E. Aurora-a kinase as a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2015;5:295. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X., Huang J., Liu F., Yu Q., Wang R., Wang J., Zhu Z., Yu J., Hou J., Shim J.S., Jiang W., Li Z., Zhang Y., Dang Y. Aurora A kinase inhibition compromises its antitumor efficacy by elevating PD-L1 expression. J. Clin. Invest. 2023:133. doi: 10.1172/JCI161929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh J.H., Power E.A., Zhang W., Daniels D.J., Elmquist W.F. Murine central nervous system and bone marrow distribution of the Aurora A Kinase inhibitor alisertib: pharmacokinetics and exposure at the sites of efficacy and toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2022;383:44–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.122.001268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ariey-Bonnet J., Berges R., Montero M.P., Mouysset B., Piris P., Muller K., Pinna G., Failes T.W., Arndt G.M., Morando P., Baeza-Kallee N., Colin C., Chinot O., Braguer D., Morelli X., Andre N., Carre M., Tabouret E., Figarella-Branger D., Le Grand M., Pasquier E. Combination drug screen targeting glioblastoma core vulnerabilities reveals pharmacological synergisms. EBioMedicine. 2023;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deleyrolle L.P., Harding A., Cato K., Siebzehnrubl F.A., Rahman M., Azari H., Olson S., Gabrielli B., Osborne G., Vescovi A., Reynolds B.A. Evidence for label-retaining tumour-initiating cells in human glioblastoma. Brain. 2011;134:1331–1343. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hothi P., Martins T.J., Chen L., Deleyrolle L., Yoon J.G., Reynolds B., Foltz G. High-throughput chemical screens identify disulfiram as an inhibitor of human glioblastoma stem cells. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1124–1136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarkisian M.R., Siebzehnrubl D., Hoang-Minh L., Deleyrolle L., Silver D.J., Siebzehnrubl F.A., Guadiana S.M., Srivinasan G., Semple-Rowland S., Harrison J.K., Steindler D.A., Reynolds B.A. Detection of primary cilia in human glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2014;117:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1340-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin B., Lee H., Yoon J.G., Madan A., Wayner E., Tonning S., Hothi P., Schroeder B., Ulasov I., Foltz G., Hood L., Cobbs C. Global analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 profiles in glioblastoma stem cells and identification of SLC17A7 as a bivalent tumor suppressor gene. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5369–5381. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porat Y., Giladi M., Schneiderman R.S., Blat R., Shteingauz A., Zeevi E., Munster M., Voloshin T., Kaynan N., Tal O., Kirson E.D., Weinberg U., Palti Y. Determining the optimal inhibitory frequency for cancerous cells using Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) J. Vis. Exp. 2017;(123):55820. doi: 10.3791/55820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.