Abstract

The successful application of human gene therapy protocols on a broad clinical basis will depend on the availability of in vivo cell-type-specific gene delivery systems. We have developed retroviral vector particles, derived from spleen necrosis virus (SNV), that display the antigen binding site of an antibody on the viral surface. Using retroviral vectors derived from SNV that displayed single-chain antibodies (scAs) directed against a carcinoembryonic antigen-cross-reacting cell surface protein, we have shown that an efficient, cell-type-specific gene delivery can be obtained. In this study, we tested whether other scAs displayed on SNV vector particles can also lead to cell-type-specific gene delivery. We displayed the following scAs on the retroviral surface: one directed against the human cell surface antigen Her2neu, which belongs to the epidermal growth factor receptor family; one directed against the stem cell-specific antigen CD34; and one directed against the transferrin receptor, which is expressed on liver cells and various other tissues. We show that retroviral vectors displaying these scAs are competent for infection in human cells which express the antigen recognized by the scA. Infectivity was cell type specific, and titers above 105 CFU per ml of tissue culture supernatant medium were obtained. The density of the antigen on the target cell surface does not influence virus titers in vitro. Our data indicate that the SNV vector system is well suited for the development of a large variety of cell-type-specific targeting vectors.

In the past few years, many human gene therapy trials have been initiated not only to cure genetic diseases but also to test the therapeutic effects of various genes for the cure of cancer and AIDS (8, 9, 14, 25, 39). In almost all trials, the tools of gene delivery are retroviral vectors (11, 24, 35). However, due to the broad host range of the vector particles used, gene therapy has been performed ex vivo. Such ex vivo protocols are cumbersome and expensive and thus far have not led to satisfactory results, except for the treatment of adenosine deaminase deficiency.

All retroviral vectors used in human gene therapy today are derived from amphotropic murine leukemia virus (ampho-MLV), a virus with a very broad host range that can infect a large variety of human cells. However, due to this broad host range, such vectors cannot be used in vivo to deliver genes solely into specific target cells. Moreover, there is a risk that ampho-MLV will infect human germ line cells if injected directly into the bloodstream of a patient.

To make MLV vectors specific for a particular cell type, several groups have modified the envelope protein of ecotropic Moloney MLV (eco-MLV), which is infectious only on mouse cells. Roux et al. showed that eco-MLV could infect human cells if an antibody bridge between the virus and a cell surface was established (15, 28). This antibody bridge anchored the virus to the cell surface, enabling internalization and membrane fusion. It consisted of two biotinylated antibodies, which were linked at their carboxy termini by streptavidine. One antibody was directed against the envelope protein of eco-MLV; the other was directed against a human cell surface protein. However, infectivity could be achieved only with 2 of 18 different conjugates, and the efficiency of infection was very low (15, 28).

In a more direct approach, Russell et al. and our group have developed retroviral vector particles that display the antigen binding site of an antibody on the viral surface (6, 29). This has been achieved using single-chain antibody (scA) technology. First, using hapten model systems, Russell et al. and our group were able to show that such particles are competent for infection (6, 29). Using spleen necrosis virus-derived (SNV) retroviral vectors and a scA directed against a human carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA)-related cell surface protein (B6.2), we showed that such scA-displaying particles are infectious as well (3, 4, 6). This finding was confirmed by using eco-MLV and a scA directed against the low-density lipoprotein receptor (34). However, recent studies with scAs directed against various other human cell surface proteins indicate that all other scA-displaying vectors derived from eco-MLV are not or only minimally infectious (19, 26, 31, 37).

To test whether other scAs displayed on SNV-derived retroviral vector particles are competent for infection, we developed vector particles that displayed three different scAs: one directed against the Her2neu antigen, one against the stem cell antigen CD34, and one against the transferrin receptor (TFR). The Her2neu antigen, which belongs to the family of epidermal growth factor receptors, is overexpressed in about 25% of all human breast cancers and displayed on numerous cell types. Thus, this antigen may not be an appropriate target for cell-type-specific in vivo delivery of therapeutic genes into one particular organ, but its use at this point was helpful for assessing the potential of this technology and SNV-derived vectors for future application in humans. (i) SNV is not infectious in human cells. Since Her2neu is expressed on many different cell types, the question of whether SNV-derived targeting vectors are suitable to transduce genes into various human cell types could be answered. (ii) Some human cancer cells overexpress Her2neu. Thus, the question of whether the density of the targeting antigen on the cell surface determines the efficiency of infection could be addressed. (iii) Some tumor cell lines such as SK-BR-3 cells shed soluble Her2neu into the medium. Thus, infection interference assays could be easily performed with supernatant medium from such cells.

The TFR is expressed on the surface of probably all proliferating cells and is involved in the heme metabolism which results in the presence on the surface of hematopoietic cells such as erythroleukemia cell line K562. Vectors directed against this target antigen may not have clinical potential but were useful for further testing the feasibility of SNV developing universal targeting vectors. The antigen CD34 is believed to be a stem cell-specific marker which is expressed in human stem cells and other progenitor cells of the hematopoietic system (2, 7, 33). Since MLV-derived vectors poorly infect human hematopoietic cells (27), it was of interest to test whether the SNV vector system is useful for transducing genes into cells of the human hematopoietic system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nomenclature.

Plasmid constructs are indicated by the letter “p” (e.g., pAJ6) to distinguish them from the virus derived from the plasmid construct (e.g., AJ6). The protein expressed from the corresponding construct is indicated as “gp” (e.g., gpAJ6).

Plasmids.

Plasmid pCXL (23) contains an SNV-derived retroviral vector expressing the bacterial β-galactosidase (lacZ) gene. pRD118-puro was derived from pRD118 (5) and contains a puromycin resistance gene driven by the SNV promoter. Plasmids pRD134 and pIM29 contain the complete wild-type envelope gene of SNV and have been described recently (20, 21).

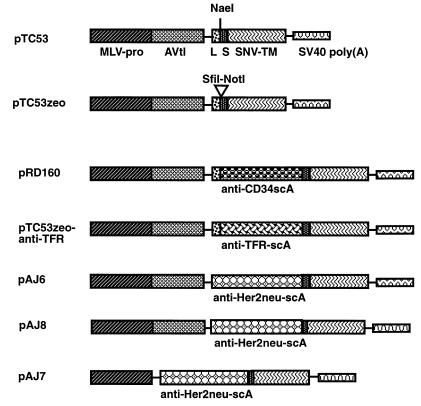

Plasmid pTC53 is a gene expression plasmid for the fast cloning and efficient expression of scA-envelope fusion proteins for display on retroviral particles (Fig. 1). pTC53, derived from pTC13 (3, 5), contains the MLV U3 promoter and the adenovirus tripartite leader sequence followed by a sequence coding for the hydrophobic leader sequence of the SNV envelope gene (Fig. 1). Next, the plasmid contains a unique NaeI site (which cuts between two codons) for cloning of scA genes (e.g., PCR products). Downstream of the NaeI site is a DNA linker coding for the amino acid motif (Gly4-Ser)3 to enable flexibility of the scA. This Gly-Ser linker is fused in frame to the complete transmembrane envelope protein (TM) coding region of the SNV envelope gene. The polyadenylation site downstream of the TM coding region was derived from simian virus 40. The plasmid backbone is that of pUC19.

FIG. 1.

Universal cloning vectors to express scA-SNV Env fusion proteins. pTC53 contains the MLV long terminal repeat promoter (MLV-pro) followed by the adenovirus tripartite leader sequence (AVtl) for enhanced gene expression. Downstream of the AVtl is the coding region of the SNV Env hydrophobic leader sequence (L), followed by a unique cloning site (NaeI) for the insertion of scA genes (e.g., PCR products). Adjacent to the NaeI site and upstream of the SNV Env-TM coding region, a spacer sequence which codes for the peptide (Gly4-Ser)3 has been inserted. Polyadenylation occurs in the poly(A) recognition sequence of simian virus 40 (SV40). The plasmid sequences flanking this cassette were derived from pUC19 and contain the ampicillin resistance gene. pTC53zeo was derived from pTC53 and contains the zeomycin resistance gene expressed from the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter inserted into the NdeI site. A short linker sequence containing SfiI and NotI sites has been inserted into the NaeI site. Thus, in pTC53zeo, scA genes can be easily transferred from the Pharmacia phage display cloning vector.

Plasmid pTC53zeoαTfnR was derived from pTC53 as follows. pTC53 was digested with NdeI followed by insertion of the NdeI fragment of plasmid pZeoSV (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) containing the zeo gene mediating resistance of mammalian cells to the antibiotic Zeocin. The plasmid pTC53zeoαTFR was constructed by recombinant PCR using oligonucleotide primers comprising the terminal restriction sites SfiI and NotI flanked in turn by additional NruI sites. The amplified scFv cDNA was digested by NruI and inserted into the vector fragment of plasmid pTC53zeo prepared after digestion with NaeI. This resulted in the loss of the NaeI and NruI restriction sites.

pRD160 was made in two cloning steps. First, the protein coding region of the anti-CD34 scA gene (in plasmid pelB1-SCA9069-His6, kindly supplied by Baxter Healthcare) was amplified by PCR as described earlier (3, 5) and cloned into the SmaI site of pRD15 (a pUC19 derivative) (32) to give plasmid pRD159. After DNA sequencing to verify the fidelity of the scA coding region, an Eco47III (introduced with the PCR primer)-to-HincII fragment was cloned into pTC53 digested with NaeI to give pRD160 (Fig. 2). pAJ6, pAJ7, and pAJ8 were made in a slightly different way. First, a DNA linker coding for the amino acid sequence Ala-Gly-Ala-Ser-Gly-Ser was inserted at the carboxy-terminal end of the anti-Her2neu scA gene (which contains the authentic hydrophobic leader sequence of the antibody gene) to give plasmid pRD161. DNA fragments (SnaB1 to Eco47III) isolated from pRD161 and which contained the anti-Her2neu scA were cloned into pIM19 (21) digested with SmaI plus MscI or SacII (blunt ended) plus MscI to give plasmids pAJ7 and pAJ8, respectively (Fig. 2). In pAJ6, a SnaB1-to-NaeI fragment isolated from pRD161 (and which does not contain the linker) was cloned into pTC53 digested with SacII (blunt ended) plus NaeI (Fig. 2). DNA sequencing was performed after all cloning steps to verify the maintenance of the correct reading frame of genes coding for chimeric proteins.

FIG. 2.

Constructs to express chimeric scA-Env fusion proteins. pRD160 and pAJ6 were derived from pTC53 and contain scA genes against the human stem cell marker CD34 or the Her2neu protein, respectively. pAJ6 has the hydrophobic leader sequence of the original antibody gene. The scA genes have been inserted into the NaeI site of pTC53. pTC53zeoαTFR was derived from pTC53zeo and contains a scA gene against the human TFR. pAJ7 and pAJ8 are similar to pAJ6 but contain shorter linker sequences. pAJ7 does not contain the adenovirus tripartite leader sequence. For abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 1; for more details about the constructs, see Materials and Methods.

In pRD154, the envelope gene of ampho-MLV (an SfiI-to-SalI fragment, isolated from plasmid pJD1 [13] [kindly provided by Howard Temin’s laboratory]) was cloned into the gene expression vector pWS4 (32) digested with XbaI (filled in) plus SalI (Fig. 2).

Cells.

D17 cells (a dog osteosarcoma cell line obtained from the American Type Culture collection [ATCC]) and human HT1080 cells (a kidney tumor cell line obtained from the ATCC) were grown in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing 6% calf serum. HeLa (human cervical carcinoma) and MDA-MB453 (human breast cancer) cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). DSH-cxl cells are SNV-derived retroviral packaging cells (20) which contain the retroviral vector pCXL (23) and have been described in detail recently (3, 5, 22). KG1a and Daudi cells (obtained from the ATCC) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. SK-BR-3 and MDA453 (human breast cancer) cells were grown in McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented with 10% FBS (30). COLO-320DM (colon carcinoma) cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

Construction of packaging cell lines.

Stable packaging cells which produce scA-displaying retroviral vector particles followed were constructed according to a protocol described in detail recently (4). Briefly, using the dog D17 cell-derived cell line DSgp13-cxl (4), which expresses the encapsidation-negative SNV Gag-Pol proteins and the packageable retroviral vector pCXL, we first made cell lines which expressed the chimeric scA-Env fusion proteins (Fig. 2). For this, the scA-env gene expression vectors were cotransfected into DSgp13-xcl cells along with a plasmid expressing a selectable marker gene (e.g., the puromycin resistance gene). About 100 to 200 single antibiotic-resistant cell colonies were isolated for each transfection, and expression of the scA-Env protein was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and infectivity assays as soon as cells had been transferred to 24-well plates. The reason for making helper cells this way is that transfected plasmid DNAs often integrate into rather inactive chromosomal sites are poorly transcribed. Cell clones that had detectable levels of the scA-Env fusion protein as well as some infectivity in human target cells were selected for further experiments (data not shown). Next, the SNV wild-type envelope gene expression vector pIM29 was transfected into cell lines established from the single colonies described above. Again, transfection was done by cotransfecting a plasmid expressing a selectable marker (e.g., the hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene). Then 100 to 200 single-cell colonies were isolated and tested for infectivity on human target cells. Cell clones with the highest infectivity were selected, recloned once or twice, and finally used for all further investigations.

Antibodies.

11A25 and 11B118 are monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific for the TM peptides of reticuloendotheliosis virus subgroup A and SNV (10). These antibodies were kindly provided by L. Lee (Regional Poultry Research Laboratory, East Lansing, Mich.). Antibodies 8550 and 8555 are polyclonal rabbit antisera raised against the C-terminal tridecapeptide of the reticuloendotheliosis virus subgroup A and SNV SU (surface envelope glycoprotein) peptides (36). These antibodies were kindly provided by S. Oroszlan (NCI-Frederick Cancer Research, Frederick, Md.). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat and anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G’s were purchased from Pierce and Sigma, respectively. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody was purchased from Promega. An antibody directed against the anti-Her2neu scA was kindly provided by Baxter.

Transfections and infections.

Transient transfections were performed with the Lipofectamine reagent as recommended by the supplier (Bethesda Research Laboratories). Briefly, 6 × 105 DSH-cxl cells were plated on 50-mm-diameter dishes the day before transfection; 6 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 15 μl of Lipofectamine. Cells were incubated with the DNA-Lipofectamine mixture in 1 ml of serum-free medium for 6 h, and then the Lipofectamine mixture was replaced with 3 ml of normal growth medium; 42 h after transfection, the supernatant medium was collected and used for infectivity studies. To obtain stable cell lines, the plasmid DNAs were transfected into D17 cells or D17-derived cells by the Polybrene (hexadimethrine bromide)-dimethyl sulfoxide method as described elsewhere (18). Infectivity studies were performed also as described recently (3). To determine the number of cells expressing the bacterial lacZ gene, the cells were stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) as described elsewhere (23).

FACS analysis of membrane proteins.

The level of proteins expressed on the cell surface was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as described recently (4, 21).

Radioimmunoprecipitation and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Confluent cell monolayers were labeled with 40 μCi of [35S]methionine-[35S]cysteine (Tran35S-label; ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, Calif.) per ml, and cell lysates were prepared as described previously (17). Incorporated [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine were determined by scintillation counting. An excess of the respective anti-Env antibody (0.1 μl of ascites fluid, containing the anti-TM 11A25 or 11B118 MAb, or 10 μl of rabbit antiserum 8555, containing polyclonal anti-SU antibodies) was preabsorbed with protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia-LKB, Piscataway, N.J.); 3 × 107 cpm of the lysate from each sample was then incubated with the immunocomplex, precipitated and subjected to electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gels as described elsewhere (17). The gels were fixed and exposed to Kodak X-ray film as described elsewhere (17).

Competition assays.

To test specificity of infection, competition assays were performed as previously described (3, 6).

RT-PCR.

mRNAS were isolated from tissue culture cells by using an mRNA isolation kit obtained from Invitrogen. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed with a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit purchased from Perkin-Elmer. Protocols recommended by the suppliers were followed. Primers used for the reactions had the following sequences (5′ to 3′): pair 1, CCAGACTCTGGTCTTCTTTGGGTA and TCATTGAAACCAGGATCCCTGCTC; pair 2, CCCTTATTACACGGAAAACGGTGG and GGAGCTCAGTGGAACTTAGAGAAC.

RESULTS

Vectors to express scA-Env fusion proteins.

We had previously shown that the B6.2 scA, directed against a CEA-related protein displayed on SNV-derived retroviral vectors, could be used to generate infectious virus particles (3, 4). For this, three fusion proteins containing the scA fused to different sites within SU or directly to TM had been constructed. It was shown that the site at which the scA had been fused to Env did not largely influence the infectivity of the resulting vector particles (3). In all experiments presented here, the scA was fused directly to TM. The cleavage motif recognized by a cellular protease which cleaves the retroviral envelope precursor protein into SU and TM was mutated. Thus, all scA-Env fusion proteins were not proteolytically cleaved and were expected to be expressed as single-peptide-chain glycoproteins (4).

To facilitate the construction of future scA-Env fusion proteins, we first constructed the universal gene expression vectors pTC53 and pTC53zeo (Fig. 1), which allowed fast and easy construction of scA-Env fusion genes. They contained the hydrophobic leader sequence of the envelope gene of SNV. After cloning of an scA coding region into the NaeI (or SfiI-NotI) site downstream of the hydrophobic leader sequence, a scA-Env fusion protein which contains the scA fused to the complete TM coding region of SNV (Fig. 1 and 2) was expressed. The scA and TM were separated by a 15-amino-acid-long spacer (Gly4-Ser)3 to achieve flexibility of the scA and enable correct folding of both peptides. Plasmids pRD160 and pAJ6 (Fig. 2), derived from pTC53, contain an anti-CD34 and an anti-Her2neu scA gene, respectively. pAJ7 and pAJ8 (Fig. 2) are similar to pTC25, which allows expression of the B6.2 scA-Env fusion protein. These constructs contain a short 6-amino-acid-long spacer (Ala-Gly-Ala-Ser-Gly-Ser) between the scA and TM (3, 5). The rationale for making these different constructs was to determine whether the length of the spacer between the scA and TM plays a role in scA display on the viral surface and/or infectivity of respective virus particles. pTC53zeoαTFR, derived from pTC53zeo and similar to pRD160, contained a scA gene derived from MAb E6 directed against the human TFR inserted into SfI- and NotI-flanked pTC53zeo.

Retroviral packaging lines producing scA-displaying vector particles.

To examine whether retroviral particles which express anti-Her2neu or anti-CD34 scAs are competent for infection, we first performed transient transfection-infection experiments as described previously (3). Briefly, the retroviral packaging cell line DSH-cxl, which expresses SNV Gag-Pol, Env, and a retroviral vector transducing the bacterial β-galactosidase gene (pCXL), was transfected with pAJ6, pAJ7, pAJ8, pRD160, or pTC53zeoαTFR, using the Lipofectamine reagent (Materials and Methods); 48 h after transfection, virus was harvested from the packaging cells, and human cell lines which express Her2neu (e.g., SK-BR-3 and COLO-320DM) or CD34 (e.g., KG1a) were infected. Virus harvested from all transfected cell lines was able to infect such cells with titers of up to 103 infectious units per ml of supernatant medium (data not shown). This result is similar to what we had obtained in transient transfection experiments using particles displaying the B6.2 scA. These data also indicate that neither the length of the spacer nor the intracellular level of gene expression of the scA-Env fusion protein had a major influence on the efficiency of infection.

To study the efficiency and specificity of this gene delivery system in more detail, stable helper cell lines were constructed (Materials and Methods). For reasons of clarity, experiments with these different scAs are described separately; we discuss first experiments with the anti-Her2neu scA and then studies with the anti-CD34 and anti-TFR scAs.

Retroviral vectors displaying anti-Her2neu scAs.

As described above, transient transfection-infection assays revealed no significant differences in infectivity among the three constructs (pAJ6 to pAJ8) which express anti-Her2neu-scA-Env fusion proteins. Thus, to reduce the amount of tissue culture work, stable packaging cell lines producing anti-Her2neu targeting vectors were made only with constructs pAJ6 and pAJ7.

First, we established cell lines that produced vector particles which displayed the chimeric envelope protein only (Materials and Methods). Consistent with our previous nomenclature, such cell lines were termed DSgp-cxl-AJ6 and DSgp- (D17 cells expressing SNV Gag-Pol proteins, the retroviral vector cxl, and the chimeric scA-Env protein from plasmid pAJ6) and DSgp-cxl-AJ7. Cell lines producing particles which display both wild-type and chimeric envelope were termed DSH plus the name of the chimeric plasmid construct plus the number of the cell clone from which the cell line was established (e.g., DSH-cxl-AJ7-cl.14 indicates that the D17-derived complete SNV-derived helper cell line contains the retroviral vector cxl and plasmid AJ7, derived from the clone 14). Infectivity of particles produced from such stable packaging lines was tested in various cell lines that do or do not express the Her2neu antigen.

Virus particles, which displayed the chimeric scA-Env fusion protein yield titers of only up to 2 × 104 CFU/ml in human cells which express the Her2neu protein (e.g., COLO-320DM, SK-BR-3, MDA-MB453, HeLa, and 293) (Table 1). Cell lines which do not express Her2neu (HT1080 and A431) cells) could not be infected (for details about Her2neu expression in human cells, see below and Fig. 3). Similar titers were obtained with packaging lines expressing construct pAJ6 or pAJ7. Table 1 shows data obtained with pAJ7. The finding that particles which display the scA-Env fusion protein without wild-type Env were highly infectious was unexpected, because earlier we found that retroviral particles displaying the B6.2 scA alone were only minimally infectious (3, 4). Vector particles containing wild-type envelope proteins alone (virus harvested from DSH-cxl cells) were not infectious in human cells, consistent with our earlier results (Table 1). Also, as demonstrated earlier, particles containing no envelope were not infectious in any of the cell lines tested (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Infectivity of SNV-derived anti-Her2neu scA-displaying retroviral vector particles on various cell linesa

| Source of SNV vector particles | Virus titer (CFU/ml)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D17 | COLO-320DM | SK-BRK-3 | MDA-MB453 | HeLa | 293 | HT1080 | A431 | |

| DSH | 106 | 3 × 101 | <101 | <101 | <101 | <101 | <101 | <101 |

| gp13 + AJ7 | <100 | 2 × 104 | 6 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 6 × 103 | <100 | <100 |

| DSH + AJ7 | 106 | 2 × 105 | 104 | 105 | 5 × 104 | 2 × 104 | <101 | <101 |

D17 cells are dog cells that can be efficiently infected with wild-type SNV vector particles (e.g., virus harvested from DSH helper cells). gp13-AJ7 and DSH-AJ7 cells are stable packaging cells producing vector particles that display anti-Her2neu scAs on the viral surface without and with the wild-type SNV envelope, respectively. All human cell lines except HT1080 or A431 express Her2neu. Because HT1080 and A431 cells do not express Her2neu, they cannot be infected with SNV vector particles that display anti-Her2neu scAs.

FIG. 3.

Expression of Her2neu in various cell lines determined by immunoprecipitation using the anti-Her2neu MAb from which the anti-Her2neu scA was derived. Her2neu, a 186-kDa glycoprotein expressed in many human tissues, is overexpressed in many breast cancer cell lines, including SK-BR-3 (lane 8). Expression was not detected in HT1080 and A431 cells (lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Lane 1, DSH-cxl cells (derived from dog D17 cells; negative control); lane 2, 293 cells; lanes 5 to 7, HeLa, COLO-320DM, and MDA-MB453 cells, respectively.

Next, packaging lines expressing both the chimeric and wild-type SNV envelopes were constructed from cell lines DSgp13-AJ6 and DSgp13-AJ7. The supernatants of more than 200 single-cell colonies were initially screened for infectivity in COLO-320DM cells. Four clones, DSH-AJ6-cl.8, DSH-AJ7-cl.14, DSH-AJ7-cl.17, and DSH-AJ7-cl.204, were selected for further analysis. All packaging lines derived from such clones produced similar titers ranging from 104 to 105 CFU/ml, i.e., 5- to 10-fold greater than titers from original producer cell lines not expressing the wild-type SNV Env (Table 1 shows pAJ7 as an example). Due to the presence of wild-type Env, these vector particles were also infectious in dog D17 cells, with titers of up to 106 CFU/ml (Table 1).

Specificity of infection.

Three sets of experiments were performed to test the specificity of infection on human cells expressing Her2neu. First, experiments were performed to show that Her2neu was present in or absent from the target cells used.

Her2neu is a 185-kDa transmembrane protein which is overexpressed in human SK-BR-3 (breast cancer) cells. It is also expressed in various other cell lines, albeit at much lower levels, and has been reported to be absent on human HT1080 and A431 cells (1). To demonstrate the density of cell surface expression of Her2neu, immunoprecipitation was performed with SK-BR-3, COLO-320DM, MDA-MB453, HT1080, 293, and A431 cells. The primary antibody used in this analysis was the parental MAb from which the scAs displayed on the viral surface had been derived. Correlating with earlier reports (1), Her2neu was detected in all cell lines investigated except HT1080 and A431 (Fig. 3). Expression was strongest in SK-BR-3 cells, followed by MDA-MB453 cells. Thus, the infectivity of anti-Her2neu scA-displaying particles coincides with Her2neu expression. However, it does not coincide with the level of Her2neu expression; e.g., COLO-320DM cells, which express low levels of Her2neu, could be infected with higher efficiency than SK-BR-3 cells or MDA-MB453 cells.

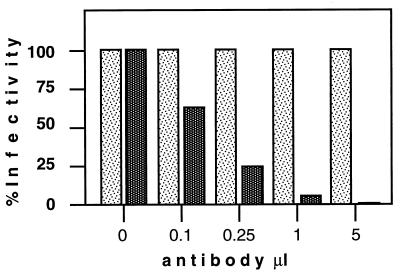

To further test the specificity of infection of anti-Her2neu scA-displaying particles, two different types of infection interference assays were performed. In the first experiment, COLO-320DM cell were preincubated with different amounts of the MAb (termed N2) from which the anti-Her2neu scA had been derived. After this preincubation, the cells were infected with retroviral vector particles displaying the anti-Her2neu scA on the viral surface harvested from the DSH-AJ7 helper cell line. Retroviral vector titers were determined and compared to vector titers obtained in cells without prior antibody preincubation or with cells preincubated with an anti-Her2neu MAb different from that displayed on the retroviral vector. We found that increasing amounts of the N2 antibody added to the cells before infection blocked infectivity of anti-Her2neu-displaying particles. About 90% inhibition of infection was observed when 4 × 105 COLO-320DM cells were preincubated with about 10 μl of MAb solution harvested from the N2 hybridoma cell line (Fig. 4A). No inhibition of infection was observed when such cells were preincubated with similar amounts of a different anti-Her2neu antibody (purchased from Becton Dickinson). The latter antibody recognized a different epitope on the Her2neu molecule. Thus, these data show that the cell-type-specific gene delivery was scA and epitope specific.

FIG. 4.

Competition assay to determine the specificity of infection with retroviral vector particles displaying anti-Her2neu scAs. (A) COLO-320DM cells were incubated with increasing amounts of N2 antibodies (dark bars) before infection or with anti-Her2neu antibody purchased from Becton Dickinson (light bars). Only the antibody from which the scA displayed on the retroviral vector was derived could block binding and infectivity. (B) Retroviral vector particles displaying anti-Her2neu scAs were incubated with increasing amounts of concentrated medium containing soluble Her2neu (harvested from SK-BR-3 cells) (black bars), concentrated medium harvested from dog D17 cells (grey bars), or medium harvested from SK-BR-3 cells which had been depleted from Her2neu by immunoprecipitation before infection (hatched bars). Virus titers were determined on COLO-320DM cells. inh, inhibitor. For details, see text.

In a second set of experiments, the virus particles were preincubated with soluble Her2neu. SK-BR-3 cells shed soluble Her2neu into the tissue culture medium. Thus, conditioned medium from SK-BR-3 cells and from D17 cells (negative control) was harvested after 3 days and concentrated 25-fold in Amicon ultrafiltration tubes. Virus particles were preincubated with increasing amounts of concentrated medium for 1 h at room temperature and then subjected to infectivity studies. We found that preincubating the vector particles with increasing amounts of Her2neu-containing medium blocked infectivity (Fig. 4B). A block of infectivity was also observed with conditioned medium harvested from D17 cells. However, this nonspecific inhibition was 1 order of magnitude less than that obtained with the Her2neu-containing medium. Moreover, when the Her2neu-containing medium was depleted from Her2neu by immunoprecipitation with anti-Her2neu antibodies before it was added to the vector particles, the inhibitory effect was very similar to that of the medium harvested from D17 cells. These data show that soluble Her2neu molecules blocked infection, again indicating that infection of Her2neu-positive cells was mediated by the scA directed against Her2neu.

SNV vector particles displaying anti-CD34 scAs.

CD34 is an antigen found in early progenitor cells of the human hematopoietic system (2, 7, 33). Stable retroviral packaging lines that displayed anti-CD34 scAs were constructed, and infectivity experiments were performed with various human cell lines. The efficiency of infection was compared to that of retroviral vector particles which contain SNV core proteins, the SNV retroviral vector pCXL, and the envelope protein of ampho-MLV strain A1070. This envelope is present on all MLV-derived vector particles currently used in human gene therapy trials.

SNV-derived vectors displaying the anti-CD34 were able to infect human KG1a cells with titers of up to 105 CFU/ml (Table 2). The infectivity in KG1a cells was 3 orders of magnitude higher than that obtained with SNV vector particles pseudotyped with the envelope of ampho-MLV (Table 2). This finding coincides with earlier reports that ampho-MLV poorly infects cells of the human hematopoietic system due to low levels of expression of the ampho-MLV receptor (27).

TABLE 2.

Infectivity of SNV-derived vector particles displaying anti-CD34 scAs on various human cell lines

| Source of vector particlesa | Virus titer (CFU/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KG1a | Daudi | HeLa | D17 | |

| DSH-cxl | <10 | <10 | <10 | 2 × 106 |

| DSgp13-cxl-RD160 | 3 × 103 | 2 × 103 | 3 × 102 | <10 |

| DSH-cxl-RD160 | 2 × 105 | 2 × 105 | 104 | 106 |

| DSgp13-cxl-MLV-Env | 2 × 102 | 5 × 102 | 105 | 105 |

All particles transduce a retroviral vector for expression of the bacterial β-galactosidase gene. DSH-cxl virus particles contain the wild-type SNV envelope; DSgp13-cxl-RD160 particles display chimeric anti-CD34 scA–SNV-Env fusion proteins; DSH-cxl-RD160 particles are similar to DSgp13-cxl-RD160 but also contain the SNV wild-type Env. DSgp13-cxl-MLV-Env particles contain SNV Gag-Pol proteins pseudotyped with ampho-MLV Env.

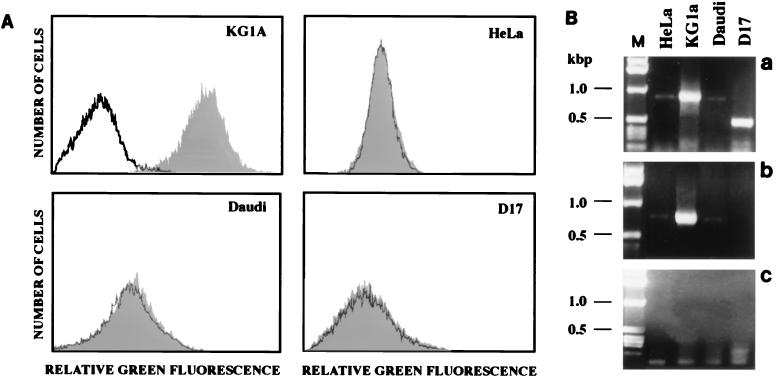

Human Daudi and HeLa cells could also be infected with retroviral vector particles displaying the anti-CD34 scA. This was surprising, because such cell lines do not reveal detectable levels of CD34 on the cell surface by FACS analysis (data not shown). However, when RT-PCR was performed with two different pairs of primers specific for CD34 mRNA, the presence of CD34 mRNA was also detected in Daudi and HeLa cells (Fig. 5). To further test whether infectivity of anti-CD34-displaying vectors in cells with low-level CD34 mRNA expression was mediated by the scA, antibody competition assays were performed as described above. HeLa cells were preincubated with increasing amounts of anti-CD34 antibody solution and then challenged with vector virus displaying anti-CD34 scAs. Preincubation of HeLa cells with increasing amounts of antibody decreased the infectivity on such cells (Fig. 6), indicating that even very low levels of cell surface expression of the antigen recognized by the scA are sufficient to enable infection of such cells in vitro.

FIG. 5.

(A) FACS analysis of cells using the anti-CD34 MAb from which the scA displayed on retroviral particles had been derived. A shift of the grey curve indicates the presence of detectable levels of CD34 molecules on the cell surface. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products of mRNAs isolated from HeLa, KG1a, Daudi, and D17 cells by using two pairs of primers specific for the CD34 mRNA. a and b, RT-PCR products obtained with primer pairs 1 (a) and 2 (b) (for sequences, see Materials and Methods), expected to give PCR products of 911 and 771 bp, respectively; c, RT-PCR with primer pair 1 after digestion of the isolated RNAs with RNase A. M, marker DNA (sizes of the bands are indicated at the left).

FIG. 6.

Competition assay to determine the specificity of infection with retroviral vector particles displaying anti-CD34 scAs. HeLa cells were preincubated with increasing amounts of MAb solution (1 μg/ml) from which the scA had been derived (dark bars) or nonspecific immunoglobulin G (light bars), followed by infection with retroviral vectors displaying the anti-CD34 scA and transducing the bacterial lacz gene. The efficiency of infection was determined by counting blue cells after X-Gal staining.

Targeting human cells that express TFR.

To further test whether other scAs displayed on SNV vector particles can be used to transfer genes into a variety of human cells, we constructed stable retroviral packaging lines that produce particles displaying scAs directed against the human TFR a housekeeping receptor that is involved in the transport of iron into the cell and thus is expressed on the cell surface of all cell types. Although the use of a scA against this receptor has no clinical application, it was useful to test whether various human cell lines differ in infectivity. To obtain high vector titers, we transfected plasmid pTC53zeoαTFR into DSH-cxl cells and, following Zeocin selection, we screened individual clones for high-titer production of vectors. The supernatant of the highest-producing cell clone was harvested and tested for infectivity on various human suspension as well as adherent cell lines. The infectious titers of the vector stock were shown to be 4 × 103 to 6 × 104 CFU/ml of supernatant medium on adherent cells and 1 × 105 to 2 × 105 on suspension cells, which are hematopoietic cells (Table 3). Thus, a variety of different scAs seem to be suitable for the production of SNV-derived cell-targeting vectors and efficient transduction of cells expressing the respective antigens on their surface. Moreover, in the case of all three scAs, the highest titers were obtained in cells of the hematopoietic system (e.g., KG1a, Daudi, and H9 cells [Table 3]).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of vector virus titers of SNV-derived vectors displaying anti-Her2neu, anti-CD34, or anti-TFR scAs in various human cell linesa

| Source of vector particles | Virus titer (CFU/ml)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KG1a | Daudi | H9 | COLO-320DM | SK-BRK-3 | MDA-MB453 | HeLa | 293 | HT1080 | A431 | |

| DSH-AJ7 | 5 × 104 | 105 | 105 | 2 × 105 | 104 | 105 | 5 × 104 | 2 × 104 | <101 | <101 |

| DSH-RD160 | 2 × 105 | 3 × 105 | 2 × 105 | 104 | 104 | 4 × 103 | 4 × 104 | 2 × 103 | 4 × 103 | 2 × 103 |

| DSH-αTFR | 105 | 105 | 2 × 105 | 6 × 104 | 104 | 104 | 2 × 104 | 104 | 4 × 103 | 8 × 103 |

SNV vector particles displaying wild-type envelope and anti-Her2neu, anti-CD34, or anti-TFR scAs were harvested from stable packaging cells and tested for infectivity in various human cell lines. All human cell lines except HT1080 or A431 express Her2neu. Since HT1080 and A431 cells do not express Her2neu, they cannot be infected with SNV vector particles that display anti Her2neu scAs. All human cells tested were found to express CD34 mRNA as tested by RT-PCR.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have shown that the tropism of SNV retroviral particles can be redirected by modifying the viral envelope protein. We have demonstrated that retroviral vector particles that display the antigen binding site of an antibody (termed B6.2, directed against a CEA-related protein) on the viral surface enable infection of human cells that express the corresponding antigen. SNV containing wild-type SNV Env is not infectious on such cells. To further investigate the versatility of this approach, we extended our experiments by using scAs against the Her2neu antigen, against CD34, and against the TFR. Here we report that SNV-derived vector particles displaying such scAs were also competent for infection. Furthermore, in the case of the anti-Her2neu or anti-CD34 scAs, even higher gene transduction efficiencies into some corresponding target cells have been obtained than with the B6.2 scA. Furthermore, extensive infection competition experiments with particles displaying anti-Her2neu scAs as well with particles displaying anti-CD34 scAs confirmed that the infectivity on human cells was mediated by the scA.

Earlier, we found that viral particles displaying chimeric envelopes in which the scA is linked directly to TM did not differ markedly in infectivity from those which contained scA-SU fusion proteins. Here, we constructed several different chimeric Env expression vectors in which the scA was directly fused to TM. Three constructs expression anti-Her2neu scA–SNV–Env fusion proteins differed in promoter strength and in the length of a spacer sequence between the scA and TM. Transient transfection studies showed no significant differences in infectivity among these constructs. Thus, neither promoter strength nor the length of the spacer appears to play a significant role in determining the level of infectivity.

Earlier we found that wild-type envelope in viral targeting vector particles had to be present to infect human cells with significant efficiencies. To test whether this also applies to vector particles that display other scAs, stable packaging lines that express chimeric envelopes only or both wild-type and chimeric envelope proteins were constructed. Surprisingly, in the case of anti-Her2neu scA-displaying particles, relatively high levels of infectivity was also observed even in the absence of wild-type Env. This finding does not coincide with our observation with particles displaying the B6.2 scA, the anti-CD34 scA, or the anti-TFR scA: in the case of particles displaying such scAs, wild-type Env had to be present to enable infection of human cells at significant levels. However, particles that displayed both anti-Her2neu scA and wild-type Env were 5- to 10-fold more infectious than particles expressing the chimeric Env only and stable packaging lines produced retroviral vector stocks containing more than 105 particles per ml of supernatant medium. Thus, wild-type Env still further increased the efficiency of infection.

The finding that the anti-Her2neu scA–Env proteins alone were sufficient to confer infectivity on Her2neu-positive cells may have several reasons. (i) The anti-Her2neu scA–Env chimeric protein is folded differently from the B6.2 scA-Env protein, exposing the membrane fusion domain of TM. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that the B6.2 scA-Env fusion protein was recognized by anti-TM antibodies, whereas the anti-Her2neu scA fusion proteins could not be detected by anti-TM antibodies (data not shown). (ii) The anti-Her2neu scA itself has a hydrophobic domain which triggers membrane fusion. (iii) The anti-Her2neu antibody binds to its antigen in such a way that it pulls the viral particle toward the cellular membrane surface, triggering an unspecific and TM-independent membrane fusion. (iv) A combination of some or all such factors contributes to successful infection. However, at this point, there are no experimental data to support one or the other of these hypotheses.

It is generally believed that the amount of viral receptors on the cell surface mainly determines the efficiency of retroviral infection of ampho-MLV: e.g., ampho-MLV-derived vectors poorly infect human hematopoietic stem cells due to low levels of the corresponding receptor (27). In contrast, avian leukosis virus efficiently infect cells, albeit low levels of receptors on the cell surface (16, 38). Our experiments suggest that SNV behaves more like avian leukosis virus: data for the anti-Her2neu scA- or anti-CD34 scA-displaying vectors indicate that the density of the cellular receptor on the surface of the target cell surface does not determine the efficiency of infectivity of SNV-derived vector particles. For example, COLO-320DM cells, which express relatively low levels of Her2neu, were more efficiently infected than cells that overexpress Her2neu (e.g., SK-BR-3 or MDA cells). SK-BR-3 cells shed soluble Her2neu, which, it may be argued, would inhibit infection. However, in all infectivity studies, the medium had been removed from the target cells prior to the addition of the vector medium (Materials and Methods). Furthermore, data for particles displaying a scA directed against the human CD34 antigen indicate that even minuscule amounts of receptor are sufficient to enable infection; e.g., HeLa cells, which do not express detectable levels of CD34 on the cell surface by FACS analysis, could be infected with anti-CD34-displaying vector particles. Antibody competition assays revealed that the infectivity was mediated by the scA. Thus, it appears that HeLa cell indeed express very low levels of CD34 on the cell surface. This hypothesis is supported by RT-PCR experiments, which demonstrated the presence of low amounts of CD34 mRNA.

In the past 2 years, it has been repeatedly reported that MLV-derived vectors that display scAs or other ligands against various cell surface antigens are only minimally infectious or not infectious at all. If this is the case, then why do SNV-derived vectors work but MLV-derived vectors do not? We have hypothesized that the cellular receptor for the SNV wild-type Env is present on human cells. However, it may be mutated so as to prevent binding and virus penetration. The scA displayed on the viral surface may anchor the SNV vector particle to the cell surface and may enable interaction of the SNV wild-type Env with the natural receptor and the consequent membrane fusion, which is pH independent and occurs directly on the cell surface as in the case of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (4, 12). However, this hypothesis still needs to be supported by more experimental data, and the actual mechanism of particle penetration remains unknown.

In summary, we previously showed that SNV retroviral vectors that display the antigen binding site of an antibody are competent for infection. Here, we show that this cell-type-specific gene delivery system is not restricted to just one particular scA. Our data indicate that it may be useful to for the display of many different scAs to deliver genes into a large variety of different human cells. Cells of the hematopoietic system appear to be particularly good targets for SNV targeting vectors. It has to be noted that the scAs used in our studies may not have immediate use in clinical applications due to the fact that the antigens targeted appear not be unique for a particular cell type. Thus, more-specific scAs need to be developed. Furthermore, it is known that vectors produced from nonhuman packaging cells are inactivated by human complement. Thus, for future clinical applications, SNV-derived human packaging cells need to be developed. The studies presented here indicate that the SNV-based targeting system has great potential, being superior to MLV for the development of targeting vectors. The efficiency of infection can probably be even further optimized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research, Baxter Healthcare, and the National Institutes of Health (R01AI41899-01) to R. Dornburg and grants 01KV9550 from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung and 328-135000/03 from the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit to K. Cichutek.

We thank Baxter for supplying the scA genes against Her2neu and CD34 as well J. Raus and H. Hogenboom for providing the scA against the human TFR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alper O, Yamaguchi K, Hitomi J, Honda S, Matsushima T, Abe K. The presence of c-erbB-2 gene product-related protein in culture medium conditioned by breast cancer cell line SK-BR-3. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenson R J, Andrews R G, Bensinger W I, Kalamasz D, Knitter G, Buckner C D, Bernstein I D. Antigen CD34+ marrow cells engraft lethally irradiated baboons. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:951–955. doi: 10.1172/JCI113409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu T-H, Dornburg R. Retroviral vector particles displaying the antigen-binding site of an antibody enable cell-type-specific gene transfer. J Virol. 1995;69:2659–2663. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2659-2663.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu T-H, Dornburg R. Toward highly efficient cell-type-specific gene transfer with retroviral vectors displaying single-chain antibodies. J Virol. 1997;71:720–725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.720-725.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu T-H, Martinez I, Olson P, Dornburg R. Highly efficient eucaryotic gene expression vectors for peptide secretion. BioTechniques. 1995;18:890–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu T-H, Martinez I, Sheay W C, Dornburg R. Cell targeting with retroviral vector particles containing antibody-envelope fusion proteins. Gene Ther. 1994;1:292–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civin C I, Strauss L C, Brovall C, Fackler M J, Schwartz J F, Shaper J H. Antigenic analysis of hematopoiesis. III. A hematopoietic progenitor cell surface antigen defined by a monoclonal antibody raised against KG-1a cells. J Immunol. 1984;133:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cournoyer D, Caskey C T. Gene therapy of the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:297–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cournoyer D, Maurizio S, Stephen N J, Moore K A, Belmont J W, Caskey C T. Gene therapy: a new approach for the treatment of genetic disorders. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47:1–11. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1990.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui Z-Z, Lee L F, Silvia R F, Witter R L. Monoclonal antibodies against avian reticuloendotheliosis virus: identification of strain-specific and strain-common epitopes. J Immunol. 1986;136:4237–4242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dornburg R. Reticuloendotheliosis viruses and derived vectors. Gene Ther. 1995;2:301–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dornburg R. From the natural evolution to the genetic manipulation of the host range of retroviruses. Biol Chem. 1997;378:457–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty J P, Wisniewski R, Yang S, Rhode B W, Temin H M. New retrovirus helper cells with almost no nucleotide sequence homology to retrovirus vectors. J Virol. 1989;63:3209–3212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3209-3212.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dropubic B, Jeang K-T. Gene therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection: genetic antiviral strategies and targets for intervention. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:927–939–927–930. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.8-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etienne-Julan M, Roux P, Carillo S, Jeanteur P, Piechaczyk M. The efficiency of cell targeting by recombinant retroviruses depends on the nature of the receptor and the composition of the artificial cell-virus linker. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3251–3255. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert J M, Bates P, Varmus H E, White J M. The receptor for the subgroup A avian leukosis-sarcoma viruses binds to subgroup A but not to subgroup C envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:5623–5628. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5623-5628.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilmore T D, Temin H M. Different localization of the product of the v-rel oncogene in chicken fibroblasts and spleen cells correlates with transformation by REV-T. Cell. 1986;44:791–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90845-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai S, Nishizawa M. New procedure for DNA transfection with polycation and dimethyl sulfoxide. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1172–1174. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.6.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marin M, Noel D, Valsesia-Wittman S, Brockly F, Etienne-Julan M, Russell S, Cosset F-L, Piechaczyk M. Targeted infection of human cells via major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by Moloney leukemia virus-derived viruses displaying single-chain antibody fragment-envelope fusion proteins. J Virol. 1996;70:2957–2962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2957-2962.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez I, Dornburg R. Improved retroviral packaging lines derived from spleen necrosis virus. Virology. 1995;208:234–241. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez I, Dornburg R. Mapping of receptor binding domains in the envelope protein of spleen necrosis virus. J Virol. 1995;69:4339–4346. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4339-4346.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez I, Dornburg R. Partial reconstitution of a replication-competent retrovirus in helper cells with partial overlaps between vector and helper cell genomes. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:705–712. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.6-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikawa T, Fischman D A, Dougherty J P, Brown A M C. In vivo analysis of a new lacZ retrovirus vector suitable for lineage marking in avian and other species. Exp Cell Res. 1992;195:516–523. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90404-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller A D. Retrovirus packaging cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1990;1:5–14. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan R A, Andserson W F. Human gene therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:191–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilson B H K, Morling F J, Cosset F-L, Russell S J. Targeting of retroviral vectors through protease-substrate interactions. Gene Ther. 1996;3:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlic D, Girard L J, Jordan C T, Anderson S M, Cline A P, Bodine D M. The level of mRNA encoding the amphotropic retrovirus receptor in mouse and human hematopoietic stem cells is low and correlates with the efficiency of retrovirus transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11097–11102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux P, Jeanteur P, Piechaczyk M. A versatile and potentially general approach to the targeting of specific cell types by retroviruses: application to the infection of human by means of major histocompatibility complex class I and class II antigens by mouse ecotropic murine leukemia virus-derived viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9079–9083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell S J, Hawkins R E, Winter G. Retroviral vectors displaying functional antibody fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1081–1085. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnierle B S, Moritz D, Jeschke M, Groner B. Expression of chimeric envelope proteins in helper cell lines and integration into Moloney murine leukemia virus particles. Gene Ther. 1996;3:334–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheay W, Nelson S, Martinez I, Chu T-H T, Dornburg R. Downstream insertion of the adenovirus tripartite leader sequence enhances expression in universal eucaryotic vectors. BioTechniques. 1993;15:856–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simmons D L, Satterthwaite A B, Tennen D G, Seed B. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding CD34, a sialomucin of human hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somia N V, Zoppe M, Verma I M. Generation of targeted retroviral vectors by using single-chain variable fragment: an approach to in vivo gene delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7570–7574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Temin H M. Retrovirus vectors for gene transfer: efficient integration into and expression of exogenous DNA in vertebrate cell genomes. In: Kucherlapati R, editor. Gene transfer. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 144–187. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai W P, Oroszlan S. Site-directed cytotoxic antibody against the C-terminal segment of the surface glycoprotein gp90 of avian reticuloendotheliosis virus. Virology. 1988;166:608–611. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valsesia-Wittmann S, Morling F, Nilson B, Takeuchi Y, Russell S, Cosset F-L. Improvement of retroviral retargeting by using acid spacers between an additional binding domain and the N terminus of Moloney leukemia virus SU. J Virol. 1996;70:2059–2064. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2059-2064.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young J A, Bates P, Varmus H E. Isolation of a chicken gene that confers susceptibility to infection by subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma viruses. J Virol. 1993;67:1811–1816. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1811-1816.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu M, Poeschla E, Wong-Staal F. Progress towards gene therapy for HIV infection. Gene Ther. 1994;1:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]