Abstract

Acetylcholine (ACh) is released from basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in response to salient stimuli and engages brain states supporting attention and memory. These high ACh states are associated with theta oscillations, which synchronize neuronal ensembles. Theta oscillations in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) in both humans and rodents have been shown to underlie emotional memory, yet their mechanism remains unclear. Here, using brain slice electrophysiology in male and female mice, we show large ACh stimuli evoke prolonged theta oscillations in BLA local field potentials that depend upon M3 muscarinic receptor activation of cholecystokinin (CCK) interneurons (INs) without the need for external glutamate signaling. Somatostatin (SOM) INs inhibit CCK INs and are themselves inhibited by ACh, providing a functional SOM→CCK IN circuit connection gating BLA theta. Parvalbumin (PV) INs, which can drive BLA oscillations in baseline states, are not involved in the generation of ACh-induced theta, highlighting that ACh induces a cellular switch in the control of BLA oscillatory activity and establishes an internally BLA-driven theta oscillation through CCK INs. Theta activity is more readily evoked in BLA over the cortex or hippocampus, suggesting preferential activation of the BLA during high ACh states. These data reveal a SOM→CCK IN circuit in the BLA that gates internal theta oscillations and suggest a mechanism by which salient stimuli acting through ACh switch the BLA into a network state enabling emotional memory.

Keywords: acetylcholine, amygdala, emotion, interneuron, oscillation, theta

Significance Statement

While acetylcholine (ACh) is critical in establishing network states enabling emotional behaviors, the mechanisms by which ACh acts on circuits involved in emotion remain unclear. The basolateral amygdala (BLA) receives dense cholinergic projections and plays a key role in emotional behaviors. Using electrophysiology recordings in mouse brain slices, we show that cholinergic stimuli induce theta oscillations in BLA through cholecystokinin (CCK), but not parvalbumin (PV) interneurons (INs). These oscillations are gated by somatostatin (SOM) INs, establishing a CCK→SOM microcircuit in the generation of theta oscillations. Further, oscillatory activity is more readily induced in BLA compared to hippocampus or cortex. These results reveal a circuit-specific mechanism for ACh modulation of BLA theta oscillations that play a critical role in emotional processing.

Introduction

Alterations in behavioral state are associated with changes in brain activity. Subcortical neuromodulators are instrumental in regulating these state-dependent changes (Scammell et al., 2017; Thiele and Bellgrove, 2018; van den Brink et al., 2019; Jones, 2020; McCormick et al., 2020). One such modulator is acetylcholine (ACh), which plays an important role in establishing network states, namely, network oscillations in the theta frequency (3–12 Hz), that support attention, memory, and emotional processes (Everitt and Robbins, 1997; Monmaur et al., 1997; Hasselmo, 2006; Hasselmo and Sarter, 2011; Luchicchi et al., 2014; Wilson and Fadel, 2017). Cholinergic innervation of the cortex and limbic regions arises from the basal forebrain (BF; Carlsen et al., 1985; Nitecka and Frotscher, 1989; Mesulam, 2004; Gielow and Zaborszky, 2017) and emotionally salient stimuli recruit BF cholinergic firing (Hangya et al., 2015; Teles-Grilo Ruivo et al., 2017; Crouse et al., 2020; Sturgill et al., 2020). Interestingly, the basolateral amygdala (BLA) receives the most robust cholinergic innervation of any target of the cholinergic BF (Hellendall et al., 1986; Emre et al., 1993). In the BLA of both humans and rodents, theta oscillations are increased during emotional processing (Paré and Collins, 2000; Maratos et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021) where they are thought to be a neural correlate of avoidance and freezing behavior (Jacinto et al., 2016; Karalis et al., 2016) through synchronized activity with both the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) and prelimbic cortex (PL; Seidenbecher et al., 2003; Lesting et al., 2011; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2012; Felix-Ortiz et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2017).

Studies in the hippocampus and cortex have found that ACh actions on GABAergic inhibitory interneurons (INs) are critical in regulating network oscillations (Pafundo et al., 2013; Zemankovics et al., 2013; Dannenberg et al., 2015; Lévesque and Avoli, 2018). In the BLA, three largely nonoverlapping IN populations can be divided based on those expressing parvalbumin (PV), cholecystokinin (CCK), and somatostatin (SOM; Hájos, 2021). Anatomically, SOM INs target distal dendrites (Muller et al., 2007), while PV and CCK INs perisomatically innervate local BLA excitatory pyramidal neurons (PYRs; Mascagni and McDonald, 2003; Rainnie et al., 2006). BLA INs are differently recruited during behavior to modulate BLA output (Wolff et al., 2014; Mineur et al., 2022), but their precise roles in synchronizing BLA network activity are not well understood. Mechanistically, BLA INs could synchronize network activity through entrainment by rhythmic inputs from external regions or conversely; these rhythms could arise internally from local BLA circuit interactions. For example, while PV INs in BLA are strongly driven by glutamatergic input, providing a possible mechanism for external glutamatergic control of theta oscillations (Bocchio et al., 2017), PV INs have been implicated in BLA theta oscillations in some (Davis et al., 2017; Ozawa et al., 2020; Antonoudiou et al., 2022), but not all conditions (Bienvenu et al., 2012). Alternately, ACh generates theta oscillation in the BLA in vivo (Aitta-aho et al., 2018) but also inhibits glutamate release from cortical input (Tryon et al., 2023), suggesting favorable conditions for internally generated BLA oscillations. Whether local BLA circuit interactions can internally produce theta oscillations, however, is still not clear. Together, these observations highlight multiple possible circuit mechanisms for theta oscillations in the BLA, yet the mechanisms underlying these remain unresolved and reveal a gap in our mechanistic understanding of emotional processing.

In this study, we systematically explored the role of BF-derived ACh in generating theta oscillations in the BLA and the circuits involved. We report that phasic cholinergic stimuli to the BLA act through muscarinic receptors (mAChRs) to reorganize local inhibitory circuits and produce internal theta oscillations with increased and synchronized PYR output. Both CCK and SOM INs play critical roles in this process. CCK INs are uniquely sensitive to ACh and are the drivers of this synchronized network behavior, revealing a previously undefined role for these cells in the BLA. These findings suggest a mechanism by which ACh release from emotionally salient stimuli can switch the BLA into a network state enabling emotional behavior and memory.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal use and care procedures were performed under the guidelines of the National Institute of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health and Human Services) and approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice had access to ad libitum food and water and were socially housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Multiple transgenic mouse lines were purchased and bred for use in this study. For experiments utilizing optogenetically released ACh, female Chat-Cre mice [ChAT-IRES-Cre::SV40pA::frt-neo-frt (B6;129S6-Chat tm2(cre)Lowl/J; stock number #006410, The Jackson Laboratory] were crossed with male Ai32 mice [B6; 129S-Gt(ROSA)26SOR tm21(CAG-COP4*H134R/EYFP)Hze/J, #012569, The Jackson Laboratory] to create ChAT-ChR2 offspring (Unal et al., 2015; Aitta-aho et al., 2018). For targeted IN recordings and manipulations, the following transgenic mice were used: PV-tdTomato mice created by crossing female PV-Cre (B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J,#008069, The Jackson Laboratory) with male Ai14 (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J,#007914, The Jackson Laboratory), SOM-tdTomato mice created by crossing female SOM-Cre (Ssttm2.1(cre)Zjh/J,#013044, The Jackson Laboratory) with male Ai14, and CCK-Cre mice (C57BL/6-Tg(Cck-cre)CKres/J,#011086, The Jackson Laboratory). Both male and female mice of all transgenic lines were used in this study when they were between 5 and 24 weeks old.

Stereotaxic viral injections

For stereotaxic surgeries, mice that were at least 6 weeks old were anesthetized with isoflurane and secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting). Adeno-associated virus (AAV, 150–350 nl) was slowly injected into the BLA of both hemispheres (coordinates relative to bregma: anterior/posterior, −0.4 mm; medial/lateral, ±3.2 mm; dorsal/ventral, −5.2 mm). For halorhodopsin experiments, PV-tdT and PV-Cre, SOM-tdT, or CCK-Cre mice were injected with AAV5-EF1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0-eYFP (UNC Vector Core). For channelrhodopsin experiments, CCK-Cre, PV-Cre, or SST-Cre mice were injected with AAV5-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP (UNC Vector Core). For selective florescent expression in CCK INs, CCK-Cre mice were injected with AAV5-hDlx-Flex-dTomato-Fishell_7 (Addgene; Dimidschstein et al., 2016), which selectively labels CCK INs. After viral injection, skin incisions were closed with topical GLUture adhesive (Abbott Laboratories), and mice were closely monitored for recovery. Injected animals were given at least 3 weeks for viral expression after surgery before use in brain slice experiments.

Brain slice electrophysiology

For brain slice preparation, mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and the brain swiftly removed and submerged in ice-cold “cutting” ACSF containing the following (in mM): 110 choline chloride, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 20 glucose, 5 MgSO4, and 0.5 CaCl2. The cutting solution was continually bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After at least one minute of recovery in this cutting solution, coronal slices of either 300 microns (whole-cell and single unit recordings) or 400–500 microns [local field potential (LFP) and multiunit recordings] were made using a VT1000S Vibratome (Leica). After cutting, brain slices were bisected and transferred to an incubation chamber filled with “incubating” artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, 5 MgSO4, and 1 CaCl2 superfused with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 34°C, pH 7.3 (300–310 mOsm). After 30–45 min of incubation at 34°C for slice recovery, the incubation chamber containing the brain slices was allowed to equilibrate to room temperature for at least 15 min before recordings were made.

For electrophysiological recordings, slices were transferred to a recording chamber where they were continuously perfused at a rate of 2–4 ml/min with warm, oxygenated recording ACSF (32–34°C, strongly bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2) containing the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 1 MgSO4, pH 7.3 (300–310 mOsm). For whole-cell recordings, neurons were visualized through a 40× water immersion objective lens with infrared-differential interference contrast optics (Olympus BX51WI). For targeted IN recordings, tdTomato-expressing cells were first identified with LED excitation (pE-4000, CoolLED) and a florescent filter cube (Thorlabs). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed using borosilicate glass electrodes with an input resistance of 3–6 MΩ. For LFP and multiunit recordings, the tips of the same borosilicate glass electrodes were manually broken off to yield an input resistance of 1–2 MΩ. Input and series resistance were monitored throughout recordings and cells discarded if either changed significantly during the recording. For optogenetic experiments, LED light (pE-4000, CoolLED) of either 490 nm (ChR2 activation) or 580 nm (halorhodopsin inhibition) was applied through the 40× objective over the recorded cell. Light pulses with wavelength 490 nm were 1–2 ms in duration and given in 5 Hz stimulation patterns for release of ACh from ChR2+ axons. For optogenetic activation experiments, ChR2 stimulation was applied with at least a 90 s delay between stimulation trials for full recovery of cholinergic fibers. For optogenetic inhibition experiments, constant 580 nm light was similarly applied over the recorded cell for 2–7 s with at least 60 s between epochs of light delivery. All recordings were made with a MultiClamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices) filtered at 2 kHz and digitized with a Digidata 1440A A-D board (Molecular Devices). LFP and multiunit recordings were amplified by 1,000–2,000×. pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices) was used for visualization and analysis of recorded traces.

LFP and multiunit recordings

The BLA is nonlinear in its organization and exhibits low activity in brain slices, making LFP recordings challenging to obtain and very small in amplitude. To increase BLA slice activity in baseline, LFP and multiunit recordings were carried out in a recording ACSF solution containing elevated KCl (3.3 mM as opposed to 2.7 mM) and an increased perfusion rate (7–12 ml/min as opposed to 2–4 ml/min; Goutagny et al., 2009). Recording electrodes were filled with the same recording ACSF as perfused over the slice. Continuous recordings were made with optogenetic cholinergic stimulation given at 5 Hz for 5 s (490 nm light, 1–2 ms light pulse duration) every 90 s. LFP recordings were high-pass filtered above 1 Hz for power spectrum analysis (pClamp 10) done in 2 s time bins directly before, during, and within 5 s after light stimulation. Total theta power was calculated as the sum of all power values from 3–12 Hz, while total gamma power was calculated as the sum of all values from 30–70 Hz. Multiunit recordings were high-pass filtered at 50 Hz and units detected using threshold event detection (pClamp 10). Multiunit frequency was determined as the number of units in 1 s time bins during recordings.

Voltage-clamp postsynaptic current recordings

Voltage-clamp recordings of PYRs were made using a symmetrical-chloride internal solution containing the following (in mM): 140 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 3 QX-314, 1 BAPTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, yielding a chloride reversal potential of 0 mV. Inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) were isolated by application of d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5, 50 µM, Hello Bio) and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione disodium salt (CNQX, 20 µM, Hello Bio) to block NMDA and AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs. Application of GABAA receptor antagonists bicuculline (Bic., 20 µM, Hello Bio) or picrotoxin (50 µM, Hello Bio) was used to block IPSCs to confirm they were GABAergic in nature. Template event detection (pClamp 10) was used for IPSC frequency and kinetic analysis. Total IPSC charge was determined as the sum of the area of all IPSCs. Small and large IPSCs were designated relative to the average IPSC amplitude of at least 20 s of baseline activity, as determined using event detection. Small IPSCs were classified as IPSCs within 1–3× average baseline IPSC amplitude and large IPSCs designated as IPSCs >5× the amplitude of baseline average IPSCs. For baseline halorhodopsin experiments to determine the contribution of different IN populations to sIPSCs, 580 nm light was applied multiple times for 2–7 s in duration for a total at least 12 s over the course 3–10 min to determine effects on IPSCs. Light on epochs were compared with IPSC activity directly preceding light and averaged over multiple trials for each cell. For ACh halorhodopsin experiments to determine the contribution of different IN populations to sIPSCs, light was applied for at least 2 s during periods of increased IPSC activity induced by a 500 ms puff of ACh (1 µM, MilliporeSigma) through a picospritzer. Light application was repeated over multiple ACh trials and averaged for each cell. Slices were only used for halorhodopsin experiments if eNpHR3.0-EGFP expressed strongly in the BLA around the recorded cell or if the recorded PYR received rebound IPSCs upon cessation of light, indicating functional halorhodopsin expression in the slice. For experiments using ChR2 in SOM INs, a pulse of 1 s 490 nm light was applied during a period of large IPSCs following focal ACh application.

Current-clamp recordings

For IN recordings, an internal solution containing (in mM) 135 K-gluconate, 5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, and 0.5 EGTA, pH 7.3 (290 mOsm) was used. Cell parameters and spiking characteristics (in response to current injections) were determined immediately after breaking into the cell. For determining ACh response, cells were held at their resting membrane potential and focal application of ACh (500 ms, 1 mM in a recording ACSF solution) delivered within 50 microns from the cell body (for tdTomato identified IN recordings) or light stimulation of cholinergic fibers at 5 Hz for 5 s (for blind putative IN recordings in ChAT-ChR2 mice). For PYR recordings an internal solution containing (in mM) 137 K-gluconate, 3 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 2 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, and 0.5 EGTA, pH 7.3 (290 mOsm) was used for detection of GABAA-mediated IPSPs (chloride reversal at −80 mV). PYR responses to ACh were determined at a −65 mV membrane potential. For experiments examining theta frequency membrane potential oscillations (MPOs) in PYRs, cells were held between −65 and −55 mV. For IPSP detection, pClamp template event detection was used and total IPSP frequency determined in 1 s time bins prior to and after light stimulation.

Paired PYR recordings

Paired recordings of neighboring PYRs (within 100 microns) were made to look at synchronization by ACh. For current-clamp recordings, synchronization of membrane potential before and after ACh stimulation was done through cross-correlation analysis (pClamp 10) in 2 s time bins. Cross-correlation was measured within 20 s before and 10 s after ACh stimulation in each cell pair and averaged across at least three cholinergic stimulation trials to produce a single value in that pair. This was done for both current-clamp membrane potential synchronization as well as voltage-clamp IPSC synchronization. PYR pairs were considered not synchronized by ACh if their cross-correlation value was <0.25. For spiking synchrony experiments, current was injected into each recorded cell to bring that cell to spike threshold and a sustained firing rate of 2–5 Hz. Spike timing was determined by event threshold detection (pClamp) and designated as synchronized if the action potential across cells was separated by <20 ms. Frequency of synchronized spiking was normalized to baseline conditions and compared with the frequency of spiking synchrony after ACh for each cell pair.

For all experiments, drugs were bath applied in the recording ACSF and allowed to wash on the slice for at least 2 min to achieve a steady-state effect. In all experiments involving ACh, a small amount of physostigmine (1 µM, Hello Bio) was present in the recording solution unless otherwise noted (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Optogenetically released ACh more reliably activates BLA over PL or vHPC inhibitory networks. A, Sample recording from a BLA PYR where rhythmic theta activity was produced following 25 pulses of light stimulation (5 Hz), but not 5 pulses. B, Heatmaps showing large IPSC frequency (1 s time bins) in all BLA cells that received 1, 5, 25, and 50 pulses of light stimulation (5 Hz) in ACSF (top) and in the presence of physostigmine (1 µM). C, Plot showing the percentage of BLA cells that show sustained (>1 s) theta frequency large IPSCs in ACSF and physostigmine (n = 16; N = 6). D, E, In the same conditions, 25 pulses of light did not evoke large IPSCs from a layer 2/3 PYR in the PL (n = 10; N = 4) (D) or CA1 PYR in vHPC (n = 16; N = 7) (E), while in that same cell, puff application of ACh (1 mM) could (insets, bottom). Heatmaps of IPSC frequency after ACh stimulation in all PL and vHPC PYRs highlight reduced sensitivity to ACh in these regions compared with the BLA.

Imaging and immunofluorescence

To validate ChR2 expression in BF cholinergic neurons, mice at least 8 weeks old were transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS containing 0.5% nitrite followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were postfixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C before 50 µm coronal brain sections were cut using a vibratome (VT1200S, Leica). Slices were blocked (TBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% donkey serum) for 30 min and then incubated for 48 h at room temperature in goat anti-ChAT primary antibody (1:1,000, AB144P, Millipore). Following rinse, sections were incubated at room temperature for 3 h in TBS containing Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (1:400, A-11056, Fisher Scientific), 0.5% Triton X-100, and 2% normal donkey serum. Sections were rinsed and mounted on slides with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Fisher Scientific). Images were captured on a Leica SP8 Multiphoton confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) software with manual counting of antibody-fluorescence overlap.

CCK INs were fluorescently labeled by a Cre-dependent viral injection in CCK-Cre mice (AAV-hDlx-Flex-tdTomato; Dimidschstein et al., 2016). For targeted PV and SOM recordings, we utilized a double transgenic cross to create PV- and SOM-tdTomato mice. PV- and SOM-tdT mice were validated in a similar manner to ChAT-ChR2 mice, instead using rabbit anti-PV primary antibody (1:15,000, PV27, Swant) or rat anti-SOM primary antibody (1:500, sc-47706, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For experiments using post hoc cell visualization, 0.1–0.3% biocytin was included in the recording pipette internal solution during whole-cell recording. Brain slices were immediately transferred to a fixative solution (4% PFA in phosphate-buffered saline) at the completion of cell recording and allowed to fix overnight. Slices were subsectioned to 50 µm using a vibratome (VT1200, Leica) and Alexa Fluor 488 Streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) applied to label the recorded cell. Images were captured on a Leica SP8 multiphoton confocal microscope.

Data analysis

pClamp 10 and OriginPro 2018 and 2020 software were used to analyze electrophysiology data. OriginPro 2020 was used to create waveforms and graphs from the data. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using a t test (paired or unpaired), a one-way ANOVA, or a repeated-measures ANOVA with appropriate post hoc tests (α < 0.05 was taken as significant). Statistical significance is designated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. For each experiment, the number of animals (N) and cells/slices (n) values are reported. Box and whisker plots with individual data points (open circles) show 25th and 75th percentiles, median (solid line) and mean (solid square).

Results

Released ACh bidirectionally modulates BLA theta oscillations

To explore how endogenously released ACh modulates BLA network activity, we used a double transgenic strategy to selectively express channelrhodopsin (ChR2) in choline acetyltransferase-expressing (ChAT) neurons (termed ChAT-ChR2 mice). These mice showed selective expression of ChR2 in cholinergic neurons in the BF and dense axonal expression of ChR2 in the BLA (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Optogenetically released ACh bidirectionally modulates BLA LFP network activity. A, Confocal images of the BF and BLA in ChAT-ChR2 mice used for this study show ChAT expression in ChR2-expressing cells in the BF and vAChT expression in ChR2-expressing axons in the BLA (99% of ChR2-EGFP+ also ChAT+, 79% of ChAT+ cells also ChR2-EGFP+; 877 cells, 2 animals). Scale bars: 150, 25, and 5 µm. B, A representative waveform of BLA LFP recording showing a bidirectional effect of light stimulation (5 Hz for 5 s) on LFP activity in different frequency bands as separated with bandpass filters (short-time Fourier transform, below). C, Averaged normalized power spectrums from all slices before, during, and after light stimulation [10 slices (n), 6 animals (N)]. D, During the light stimulus (left), the total power in theta frequency (3–12 Hz) is decreased (0.69 ± 0.12 of baseline; paired t test; p = 0.039) while gamma frequency power (30–70 Hz) is not affected (0.97 ± 0.09 of baseline; paired t test; p = 0.77). After light (right), both theta (4.85 ± 1.08 of baseline; paired t test; p = 0.006) and gamma frequency power (1.92 ± 0.38 of baseline; paired t test; p = 0.037) are increased.

LFP recordings were performed in mouse coronal brain slices containing the BLA. Cholinergic terminals were activated with 1–2 ms pulses of 490 nm LED light delivered at 5 Hz for 5 s (Nagode et al., 2011). This stimulus pattern is consistent with BF cholinergic neuron firing in vivo during active waking and paradoxical sleep (Lee et al., 2005), representing a physiological phasic ACh release event. Light stimulation of cholinergic terminals had a biphasic effect on BLA LFP activity. Low-frequency activity in baseline was suppressed upon light stimulation that persisted during most of the 5 s light stimulus train (Fig. 1B). Following light stimulation, there was a robust increase in large-amplitude rhythmic network activity in the theta range (3–12 Hz) that often lasted for >10 s beyond the light stimulus. Power spectrum analysis in 2 s time bins before, during, and after light stimulation (Fig. 1C,D) revealed that total power at theta and gamma frequencies were affected. During the light stimulus, total theta power was significantly suppressed while gamma power was not. After light, there was an almost fivefold increase in theta power and a smaller, but significant increase in gamma power. Comparing the magnitude of ACh increases in theta and gamma power showed the poststimulation increase was significantly higher for the theta band (paired t test; p = 0.025), highlighting a strong role of ACh in inducing theta oscillations in BLA slices, as is observed in vivo (Unal et al., 2015; Aitta-aho et al., 2018).

ACh increases inhibitory circuit activity in the BLA

To explore the circuit mechanisms underlying ACh’s induction of BLA theta oscillations, we performed intracellular whole-cell recordings from BLA PYRs to monitor spontaneous synaptic activity. At baseline, recordings from PYRs showed periodic (<0.5 Hz) large, compound events (Fig. 2A). These events mirrored high-amplitude, low-frequency baseline activity of LFP recordings (Fig. 1B) and were blocked by application of either glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX (20 µM) and AP5 (50 µM) or the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (20 µM), indicating they were dependent on both glutamate and GABA transmission, consistent with previous reports of low-frequency network activity in BLA slices (Pape et al., 1998; Ryan et al., 2012; Perumal et al., 2021). Light stimulation of cholinergic fibers induced a marked change in synaptic activity (Fig. 2B). After an immediate (<5 ms onset) large-amplitude event induced by the first light pulse, there was a delayed induction of large, rhythmic events that occurred at theta frequency (Fig. 2B; power spectrum analysis: peak power frequency, 6.93 ± 0.38 Hz; n = 51, N = 18) that persisted beyond the light stimulation (average duration, 10.24 ± 0.5 s). There was no difference in these events from slices of male or female mice (slices from male mice, n = 27, N = 10; slices from female mice, n = 24, N = 8), and both sexes were combined for the remainder of the study. Unlike large events in baseline, these theta frequency events were not affected by glutamate antagonists or by a GABAB receptor antagonist but were fully blocked by bicuculline (Fig. 2C), indicating these events were entirely GABAergic in nature and did not require glutamate transmission. These properties differed from low-frequency BLA network activity in baseline states and highlight a switch in synchronized network dynamics by ACh. Additionally, while the broad nicotinic receptor (nAChR) antagonist mecamylamine (mec, 10 µM) had no effect on these events, they were fully blocked by the muscarinic receptor (mAChR) antagonist atropine (atro, 5 µM, Fig. 2D), indicating they were driven by mAChRs, but not nAChRs. Further, application of an M1 [telenzepine (tzp), 0.1 µM] or an M2 (AFDX, 1 µM) antagonist had no effect on these events, but application of an M3 receptor antagonist (4DAMP, 1 µM) blocked them completely (Fig. 2D). These results suggest ACh acts through an M3 receptor-mediated mechanism to drive inhibitory network activity in the BLA.

Figure 2.

ACh induces large changes in BLA inhibitory activity. A, Baseline recordings of spontaneous network activity in BLA PYRs show low-frequency, large-amplitude events that are blocked by either CNQX (20 µM) or bicuculline (20 µM). B, Optogenetic stimulation (5 Hz, 5 s) produces large theta frequency rhythmic events (power spectrum for sample waveform) that persist beyond light stimulation and are blocked by bicuculline (inset). C, Comparing total theta power of ACh-induced events show they are not blocked by glutamate antagonists (CNQX, 20 µM + AP5, 50 µM; n = 12; N = 5) or a GABAB antagonist (CGP, 2 µM; n = 6; N = 3) but are blocked by a GABAA receptor antagonist (bicuculline; n = 7; N = 5), one-way ANOVA; p = 2.28 × 10−5. D, Sample waveforms from a representative cell showing rhythmic events after light in control (black), +Mec. (10 µM, blue), and +Atro. (5 µM, green). Normalized total charge of these events show they are not affected by Mec. but are blocked by Atro; n = 8; N = 6; one-way repeated-measures ANOVA; p = 1.66 × 10−10. They are also blocked by a selective M3 receptor antagonist 4DAMP (n = 8; N = 3), but not an M1 (Tzp; n = 5; N = 3) or M2 (AFDX; n = 8; N = 3) antagonist (green graph, right); one-way ANOVA; p = 5.8 × 10−10. E, Isolation of IPSCs (CNQX and AP5) following light stimulation shows a slow, robust increase in IPSC total charge and (inset) IPSC frequency of both small (1–3× average) and large (>5× average) amplitude IPSCs (n = 11; N = 6). F, Waveform from example cell showing large IPSCs (top). Superimposing each large IPSC shows they consistently contain multiple, summated IPCSs (arrows, example IPSC dark blue trace, other IPSCs light blue traces).

To understand the direct effects of ACh on BLA inhibitory activity, IPSCs were isolated with application of glutamate antagonists (CNQX, 20 µM, and AP5, 50 µM). Measuring total IPSC charge over time (1 s bins) showed a drastic increase in IPSC charge in response to light stimulation that reached a maximal level after the end of light stimulation (Fig. 2E). The increase in IPSC charge was not only due to the presence of larger amplitude theta IPSCs induced by light stimulation but also an increase in overall IPSC frequency. Dividing IPSCs into small (1–3× average baseline IPSC amplitude) and large (>5× average baseline IPSC amplitude) events showed that light stimulation increased both types of IPSCs (Fig. 2E), indicating an increase in overall inhibition in the BLA. Large IPSCs were significantly more enhanced by light stimulation and peaked in the theta frequency range (fold increase in IPSC frequency by light: large, 28.26 ± 4.36; small, 3.37 ± 0.43; paired t test; p = 3.29 × 10−4). Isolation of the large IPSCs revealed that they contained tightly summated IPSCs that occurred within millisecond of each other (Fig. 2F), suggesting highly synchronized activity from multiple presynaptic INs.

Preferential activation of BLA over hippocampal or cortical inhibitory networks by ACh

Due to the delayed timing of the rhythmic activity following stimulation, we were curious to explore how different amounts of cholinergic stimulation would impact circuit activity. Accordingly, increasing light stimulation (1, 5, 25, and 50 pulses at 5 Hz) was given either with or without the presence of low levels of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor physostigmine (1 µM). Interestingly, in most cells, large rhythmic IPSCs were only induced with increasing cholinergic stimulation (Fig. 3A) and rarely occurred with a single light pulse, suggesting they were dependent on the size of the cholinergic stimulus. In agreement, application of a low level of physostigmine greatly increased the probability of a given cholinergic stimulus to evoke large theta frequency IPSCs (Fig. 3C). In cells that showed ACh-induced large IPSCs in ACSF control conditions, physostigmine did not affect the overall frequency of the large IPSCs (large IPSC frequency after 5 s stimulation: ACSF, 7.0 ± 1.71 Hz, n = 4, N = 3; +PHYSO, 7.37 ± 1.18 Hz, n = 12, N = 7; two-sample t test; p = 0.87; t(14) = −0.16), but instead increased the time over which they occurred (ACSF, 6.05 ± 0.66 s; PHYSO, 19.20 ± 2.57 s; n = 8, N = 5; paired t test; p = 0.003; t(7) = −0.16), suggesting it did not fundamentally change the nature of the IPSCs and network event. Interestingly, large theta IPSCs peaked with similar latency after cholinergic stimulation onset regardless of the duration of the stimulation (onset latency: 1 s stimulation, 5.88 ± 0.57 s; 5 s stimulation, 6.81 ± 0.85 s; 10 s stimulation, 6.96 ± 1.06 s; one-way ANOVA; p = 0.63; F(2,36)= 0.47), suggesting they were not dependent on the exact nature of the cholinergic stimulus.

The BLA receives extremely dense cholinergic projections from the BF, more so than other cortical structures associated with fear circuitry, notably layer 2/3 of the PL and the CA1 region of the vHPC (Hellendall et al., 1986; Emre et al., 1993). While ACh is simultaneously released across these regions (Teles-Grilo Ruivo et al., 2017; Sturgill et al., 2020) in response to a salient stimulus, the comparative effect of similar cholinergic stimulation in these circuits is not clear. Endogenous ACh can evoke rhythmic IPSCs in HPC (Nagode et al., 2011, 2014). However, due to differences in cholinergic circuits, we hypothesized that large theta network activity would be less reliably evoked in the PL or vHPC compared with that in the BLA in response to the same cholinergic stimulus. To test this, we performed recordings from PYRs in either layer 2/3 in the PL or CA1 of the vHPC. As hypothesized, large IPSCs were much less reliably evoked in both the PL and the vHPC compared with those in the BLA (Fig. 3D,E), even in the presence of physostigmine. Interestingly, in cells where light stimulation did not evoke these events, a focal puff of ACh (1 mM) was able to evoke rhythmic large events (Fig. 3D,E), suggesting that the light stimulus failed to do so due to insufficient levels of ACh at critical points in the circuit. The findings suggest that cholinergic input preferentially induces theta network activity in BLA over the hippocampus and cortex, highlighting that the same cholinergic stimulus has brain area-specific effects.

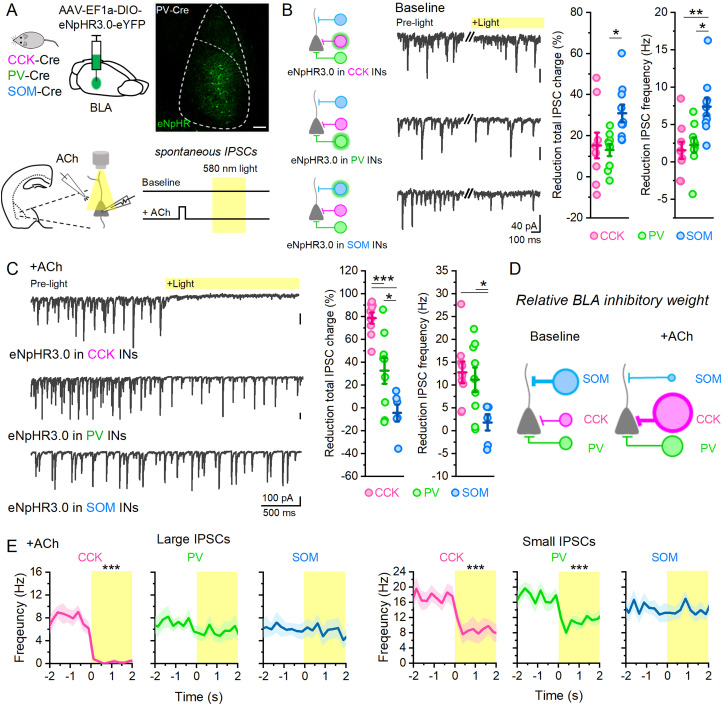

ACh activation of perisomatic inhibitory populations in the BLA

To understand how ACh modulates BLA inhibitory circuits to produce theta oscillations, we utilized the inhibitory opsin halorhodopsin (AAV-EF1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0) to selectively silence CCK, PV, or SOM IN populations during recordings of spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) from BLA PYRs (Fig. 4A). Since the CCK-Cre line exhibits Cre expression in populations of local BLA PYRs in addition to CCK INs (Rovira-Esteban et al., 2019), IPSCs were isolated in these experiments using glutamatergic antagonists added to the bath (CNQX, 20 µM, and AP5, 50 µM). In baseline conditions, inhibition of SOM INs resulted in the largest reduction in total sIPSC charge and frequency compared with CCK or PV INs (Fig. 4B), indicating SOM INs as dominant drivers of BLA inhibition in baseline states.

Figure 4.

ACh shifts dominant form of inhibition in BLA. A, Schematic of experimental design where BLA IN populations are selectively inhibited by halorhodopsin in brain slice preparations. Scale bar, 100 µm. B, Sample waveforms from BLA PYRs showing sIPSCs before and during light inhibition of CCK (n = 9; N = 4), PV (n = 9; N = 3), and SOM INs (n = 10; N = 4). Total reduction of IPSC charge and IPSC frequency during light is highest during SOM IN inhibition (one-way ANOVA; IPSC charge, p = 0.022; IPSC frequency, p = 0.002). C, Sample waveforms from BLA PYRs after ACh show different effects of light inhibition of CCK, PV, and SOM INs compared with baseline. Total reduction of IPSC charge and IPSC frequency during light is now highest during CCK IN inhibition (one-way ANOVA; IPSC charge, p = 7.6 × 10−6; IPSC frequency, p = 0.018). D, Schematic showing the representative shift in BLA inhibition by ACh. E, Comparing the frequency of large (>5× baseline average) and small (1–3× baseline average) IPSCs after ACh shows IN specific involvement.

Next, we sought to determine how ACh modulated activity in these inhibitory networks. ACh (1 mM) was briefly (500 ms) focally applied through a puffer pipette positioned near the recorded cell, which produced similar effects on BLA circuits as optogenetically released ACh (large IPSC frequency: optogenetically released ACh, 7.63 ± 0.71 Hz, n = 51, N = 18; focal puff ACh, 6.94 ± 0.38 Hz, n = 14, N = 12; two-sample t test; p = 0.39; t(63) = 0.85). Following focal ACh application, eNpHR inhibition of these different IN classes revealed a dramatic shift in activity of BLA inhibitory circuits. In these conditions, inhibition of CCK INs now blocked the large majority of IPSC charge (Fig. 4C), while inhibition of PV INs blocked a smaller component. Conversely, inhibition of SOM INs in this condition had no effect. There was also a larger decrease in IPSC frequency by inhibiting CCK and PV INs when compared with that of SOM INs. Taken together, these results indicate that ACh, acting via M3 mAChRs, shifts the BLA network from a state of strong SOM-mediated inhibition to a state of dominant CCK- and PV-mediated inhibition (Fig. 4C,D), shifting inhibition from dendritic to perisomatic compartments.

To understand the contribution of these different IN populations to theta oscillatory activity following ACh, we separated IPSCs into large or small events and plotted their frequency over time prior to and during eNpHR inhibition (Fig. 4E). Inhibition of CCK INs (n = 12; N = 4) resulted in a complete reduction of large IPSCs (paired t test; p = 5.12 × 10−6) and a partial reduction of small IPSCs (paired t test; p = 0.0015). PV IN inhibition (n = 16; N = 7) had no effect on the large IPSC frequency (paired t test; p = 0.274) but did result in a partial reduction of the small IPSCs (paired t test; p = 4.88 × 10−4). Finally, inhibition of SOM INs (n = 13; N = 6) had no effect on the frequency of either the large (paired t test; p = 0.661) or small IPSCs (paired t test; p = 0.672) after ACh. These results indicate that large theta frequency IPSCs induced by ACh were mediated by CCK INs, while the increased small IPSCs were produced by both PV and CCK INs. SOM INs did not contribute significantly to either type.

To confirm that CCK INs also drive large IPSCs in response to optogenetically released ACh, GABA release was selectively inhibited from CCK terminals via cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) activation (McDonald and Mascagni, 2001; Fig. 5A). Following optogenetic stimulation of ACh, large IPSCs in BLA PYRs were blocked by bath application of the CB1 agonist WIN 55,212-2 (2 µM; Fig. 5B) to block GABA release from the entire network of CCK INs or by a depolarizing-induced suppression of inhibition protocol (Fig. 5C) to block GABA release from CCK INs acutely at the recorded PYR. These manipulations further confirmed CCK INs as driving oscillatory theta inhibition in the BLA in response to large cholinergic stimulation.

Figure 5.

Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R)-expressing CCK INs underlie ACh-induced large IPSCs in BLA PYRs. A, In CCK-Cre and PV-Cre mice AAV5-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was injected into the BLA to allow for selective activation of CCK and PV INs in brain slice preparations. Application of WIN 55,212-2 (2 µM) reduced the amplitude of CCK-evoked IPSCs (WIN, 0.35 ± 0.04 of control IPSC amplitude; n = 4; N = 3; paired t test; p = 0.003; t(2) = 17.61) but not PV IPSCs (WIN, 1.17 ± 0.21 of control IPSC amplitude; n = 3; N = 3; paired t test; p = 0.48; t(2) = −0.85). B, Sample recording from BLA PYR showing large IPSCs in response to ACh stimulation in control conditions that are abolished by application of WIN in the bath. Measurements of large IPSC frequency show that these events are blocked by WIN (large IPSC frequency after ACh: CTRL, 7.56 ± 0.99 Hz; +WIN, 0.59 ± 0.25 Hz; n = 11; N = 5; p = 6.05 × 10−5; t(10) = 6.60). C, Additionally, depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) in a PYR recording (holding at 0 mV for 2 s) could also block large IPSCs after ACh stimulation that could be reversed by AM251 (1 µM; n = 5; N = 4), indicating an involvement of CB1Rs. Measuring large IPSC frequency in control conditions and after DSI shows this significant reduction (large IPSC frequency after ACh: CTRL, 6.82 ± 0.81 Hz; after DSI, 0.58 ± 0.20 Hz; 23 cells; 11 animals; paired t test; p = 1.11 × 10−7; t(22) = 7.70).

SOM IN activity can block CCK-induced theta inhibition in the BLA

SOM INs can fire rebound spikes following eNpHR inhibition (Royer et al., 2012; Lucas et al., 2016). Indeed, unit recordings from SOM INs in our preparations showed the presence of rebound spikes following light inhibition that could produce a barrage of rebound ISPCs in recorded PYRs in these slices (Fig. 6A,B). Interestingly, while eNpHR inhibition of the SOM INs had no effect on IPSCs induced by ACh (Fig. 4C,E), large IPSCs in BLA PYRs were significantly disrupted immediately by the cessation of light inhibition of SOM INs. Blockade of the large IPSCs by SOM rebound firing suggested a critical connection between SOM and CCK IN activity in the BLA, whereby SOM IN activity could block ACh-induced theta inhibition driven by CCK INs. To further test this, ChR2 was selectively expressed in SOM INs in BLA slices. This allowed for optogenetic activation of all SOM INs during ACh-induced CCK-mediated IPSCs in the BLA to determine if activation of SOM INs alone could disrupt rhythmic CCK-mediated theta inhibition (Fig. 6C). Indeed, light activation of SOM INs (490 nm light, 1 s duration) after ACh blocked the large IPSCs (Fig. 6D) within millisecond of SOM activation, suggesting that activity in these cells gate CCK IN activity in the BLA and theta oscillatory inhibition in response to ACh.

Figure 6.

SOM INs block CCK IN-induced theta frequency inhibition after ACh. A, Sample waveforms showing rebound firing in unit recording of SOM IN expressing eNpHR and rebound IPSCs in PYR. Scale bar, 20 µm. B, Rebound firing of SOM INs after light inhibition produces a barrage of IPSCs in BLA PYRs that block large IPSCs after ACh (n = 10; N = 3; paired t test; p = 0.004). C, Expression of ChR2 in SOM INs allows for optical activation of SOM INs with a single light pulse (top) or a barrage of SOM IN IPSCs during a 1 s light stimulus (bottom). D, Sample waveform showing activation of SOM INs disrupts CCK-mediated IPSCs in BLA PYR induced by ACh. E, Large IPSC frequency is decreased during activation of SOM INs (n = 6; N = 3; paired t test; p = 0.003). F, Circuit schematic showing SOM innervation of CCK INs that can gate ACh-induced theta inhibition.

Differential response to focal ACh by CCK, PV, and SOM INs

We have shown differential activity of CCK, PV, and SOM IN networks in the BLA after ACh stimulation. To gain a mechanistic understanding of this at the cellular level, we performed fluorescently targeted whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from these INs using different transgenic strategies (Fig. 7A). Recordings from these preparations revealed characteristic electrophysiological differences in the cell populations (Fig. 7B) consistent with previous reports (Hájos, 2021), confirming targeting in largely nonoverlapping populations.

Figure 7.

ACh differentially impacts CCK, PV, and SOM INs in the BLA. A, Targeted recordings from CCK, PV, and SOM INs, showing different firing patterns to current injection and spontaneous EPSCs (traces) were obtained using different transgenic strategies (top, confocal images showing LA/BLA complex, dotted white lines). Scale bar, 100 µm. B, Recordings from tagged neurons in these preparations show that these populations of INs can be distinguished based on electrophysiological parameters. C, Local puff application of ACh onto CCK, PV, and SOM INs reveals differential mAChR responses to ACh in these populations. D, Breakdown of mAChR response in each IN population. E, CCK INs are more likely to fire action potentials from rest in response to ACh. F, Sample waveform showing firing in a CCK IN in response to repeated puff application of ACh in control conditions (pink) or after application of 4DAMP (1 µM). Graph (top right) showing the firing frequency in each trial (light pink) and average (dark pink) for the sample cell and the average firing frequency in all cells in control and 4DAMP (bottom right; paired t test; p = 9.7 × 10−4; n = 4; N = 3). G, Sample waveform showing that underlying depolarization in CCK INs is blocked by 4DAMP (paired t test; p = 0.016; n = 4; N = 3).

To explore how these IN populations are modulated by mAChRs, we applied focal puff application of ACh (1 mM) within roughly 50 microns of the recorded cell. In some cells, an initial fast nAChR response was observed. In these instances, the mAChR response was determined with mecamylamine (20 µM) present. Not surprisingly, when recording from a resting membrane potential, the majority of both CCK and PV INs exhibited a slow depolarizing response to ACh (Fig. 7C,D). For CCK INs, 71% of cells (10/14 cells) had a slow ACh response that could be completely blocked by atropine (5 µM), indicating it was a mAChR response. In all CCK INs with a mAChR response, the response was depolarizing. On the other hand, while all PV INs exhibited a mAChR response (31/31 cells), a minority of the cells responded in a biphasic manner (4/31 cells), with an initial hyperpolarizing response followed by a delayed depolarization (Fig. 7D). While a minority of SOM INs were also depolarized by ACh (4/15 cells), nearly half of all recorded SOM INs were hyperpolarized (7/15 cells). In many instances, ACh blocked spontaneous action potential firing in SOM INs. Like PV INs, a minority of SOM INs also responded in a biphasic manner (4/15 cells). In addition to fluorescently targeted IN recordings, in recordings from 39 putative INs (as identified by electrophysiological parameters such as firing properties and membrane resistance) in ChAT-ChR2 slices, 28 cells showed similar muscarinic responses to released ACh, indicating that our focal puff application of ACh acts on INs in the BLA in a similar manner to transient endogenous ACh release.

Interestingly, from resting membrane potential, mAChR responses induced IN firing in 50% of CCK INs recorded, compared with only 19% of PV and 13% of SOM (Fig. 7E). When compared with PV INs, the difference in CCK sensitivity to firing could not fully be explained by the amplitude of ACh depolarization (amplitude ACh depolarization: PV, 4.12 ± 0.49 mV; CCK, 5.97 ± 1.03 mV; two-sample t test; p = 0.09) but was also likely due to differences in intrinsic parameters in these populations, including CCK INs exhibiting a more depolarized resting membrane potential, higher input resistance, and lower rheobase to action potential firing (resting membrane potential: PV, −68.37 ± 0.41 mV; CCK, −64.05 ± 0.97 mV; two-sample t test; p = 3.16 × 10−4; input resistance: PV, 152.99 ± 4.66 MΩ; CCK, 243.33 ± 19.53 MΩ; p = 4.68 × 10−9; PV, n = 132, N = 45; CCK, n = 18, N = 7; rheobase: PV, 187.25 ± 19.09 pA, n = 20, N = 6; CCK, 94.70 ± 11.79 pA; n = 17, N = 7; p = 3.58 × 10−4). Because ACh-induced large IPSCs in BLA PYRs were mediated by CCK INs and were blocked by the M3 antagonist 4DAMP, we hypothesized that CCK depolarization by ACh was also mediated by M3 mAChRs. Indeed, application of 4DAMP (1 µM) blocked CCK IN firing by ACh (Fig. 7F) and the underlying depolarization (Fig. 7G).

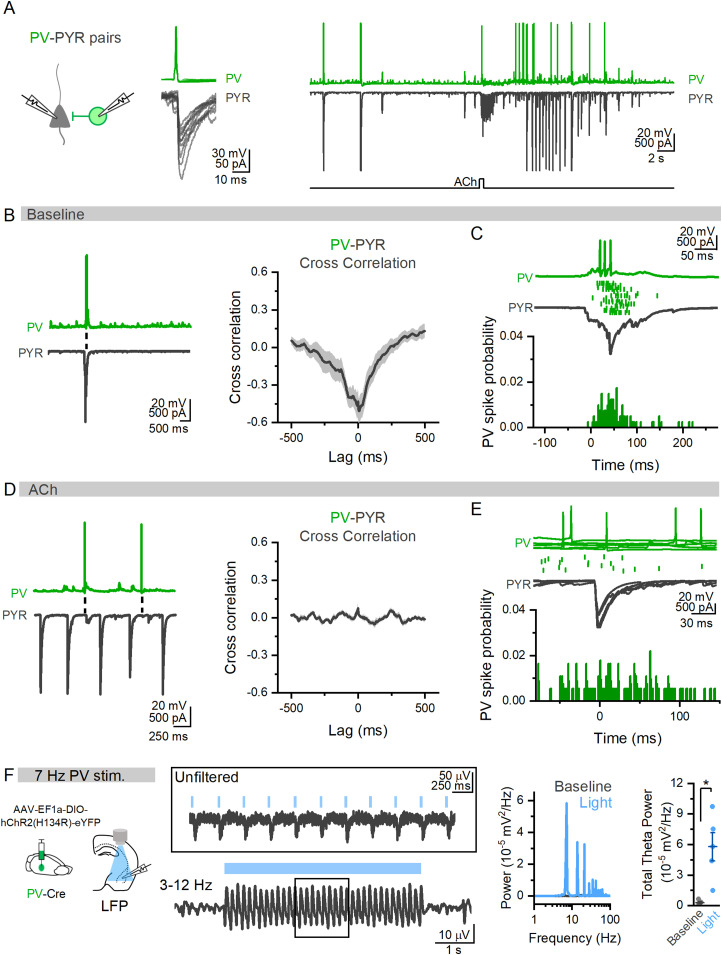

In paired PV→PYR recordings (Fig. 8A), even when PV INs did fire in response to ACh, their action potentials did not align with large IPSCs in the PYR (Fig. 8D,E). This contrasted from large events in baseline where PV IN firing was directly aligned (Fig. 8B), further indicating a shift in the circuit mechanisms underlying synchronized network activity by ACh. Indeed, optogenetic activation of PV INs could drive theta oscillations of BLA LFP (Fig. 8F) further indicating that these cells are capable of driving theta oscillations but are not doing so in response to cholinergic stimuli.

Figure 8.

BLA PV INs align with large network activity in baseline but not during ACh states. A, Example paired recording of a synaptically connected PV IN and PYR in the BLA (left) in baseline and after puff application of ACh (right). B, In same PV→PYR pair, sample trace of baseline network activity in the absence of ACh showing PV firing and large IPSCs in BLA PYR. Cross-correlation of these baseline network events shows high degree of cross-correlation (n = 5 pairs; N = 4). C, Zoomed in traces showing PV firing in relation to PYR network event (green dots represent action potentials across multiple trials from the same PV IN) show these events are tightly aligned to PYR activity in baseline conditions (bottom, total of 100 PV spikes from 5 PV→PYR pairs, 4 animals). D, In the same PV→PYR pair, traces show action potential firing in PV INs does not align with PYR IPSCs in the presence of ACh. Cross-correlation of PV and PYR membrane potentials after ACh show low cross-correlation (13 pairs; N = 6). E, Time-locked overlay of five individual large IPSCs after ACh in the PYR (bottom) and action potentials in PV IN (top, dots underneath trace represent PV action potentials across 11 IPSCs) highlights that these events do not align (bottom, probability of PV action potential in relation to the start of large IPSC in PYR: total of 107 PV spikes from 13 PV→PYR pairs, 6 animals). F, When ChR2 is expressed in PV INs in BLA slices, light stimulation at 7 Hz results in robust oscillations of the LFP (traces from example slice and corresponding power spectrum, right). Comparing total theta power (3–12 Hz) of LFP in baseline and during light stimulation of PV INs shows induction of theta oscillations by PV INs (total theta power (10−5 mV2/Hz): baseline, 0.28 ± 0.10; light, 5.78 ± 1.40; n = 5, N = 3; paired t test; p = 0.016; t(4) = −4.01).

ACh activates and synchronizes BLA PYRs

To understand how ACh is interacting with PYRs in the BLA during ACh-induced theta LFP oscillations, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of PYRs were performed. BLA PYRs exhibited a direct biphasic response to the cholinergic stimulus: an initial hyperpolarization followed by a slow depolarization that persisted beyond light stimulation, consistent with previous reports (Unal et al., 2015; Aitta-aho et al., 2018; Fig. 9A). The hyperpolarization lasted for the duration of the ACh release and was terminated by the cessation of the light stimulation at which point the slow depolarization became apparent. Interestingly, the slow depolarizing response in PYRs after light stimulation was not induced in all cells and often required increasing light stimulation or the presence of physostigmine (1 µM), again indicating that ACh’s effects on BLA circuits are dependent on the size of the cholinergic stimulus.

Figure 9.

ACh produces theta frequency oscillations in BLA PYRs. A, An example image of a recorded PYR showing characteristic spiny dendrites (top) and biphasic postsynaptic response to released ACh. Magnification of the membrane potential shows large rhythmic activity after light that is blocked by bicuculline (20 µM). Scale bar, 25 µm. B, Average power spectrums of PYR membrane potential before and after light show large increase in theta power (3–12 Hz) after light (paired t test; p = 2.28 × 10−5; n = 38; N = 13). C, This increase in theta power is blocked by bicuculline (n = 8; N = 5; one-way repeated-measures ANOVA; p = 5.24 × 10−4). D, Application of the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 (2 µM) also blocks theta oscillation in BLA PYRs induced by ACh (n = 9; N = 3; one-way repeated-measures ANOVA; p = 0.032). E, Plotting the average BLA PYR membrane potential after ACh stimulation shows a temporal overlap with theta frequency IPSPs in these cells. F, Unit recordings from BLA PYRs show that in response to cholinergic stimulation, they can fire at a theta frequency, which is blocked by atropine (5 µM; average unit frequency after light, 4.66 ± 0.98 Hz; n = 11, N = 7; peak frequency after light + atropine, 0.21 ± 0.14 Hz; n = 4, N = 3; two-sample t test; p = 0.022.)

In addition to the direct cholinergic response, BLA PYRs also exhibited a slow-onset large theta frequency MPO after light stimulation (Fig. 9A,B). This MPO began with a similar latency regardless of when the cholinergic light stimulation ended, like that of the large theta IPSCs recorded from BLA PYRs (Fig. 3). In agreement with IPSC experiments, application of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (20 µM) completely blocked the theta MPOs induced by light (Fig. 8C). Consistent with a role of CCK INs driving theta inhibition in this state, MPOs in PYRs were also abolished by the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,252–2 (2 µM; Fig. 9D).

Interestingly, we noted that large IPSPs evoked by ACh reached theta frequency during the rising phase of the ACh-induced depolarization of BLA PYRs (Fig. 9E). To test the hypothesis that this temporal relationship would have implications for spiking output of BLA PYRs, we performed cell-attached unit recordings in BLA PYRs (Fig. 9F). As predicted, ACh caused increased action potential firing that peaked in the theta frequency range and could be blocked by atropine (average unit frequency after light, 4.66 ± 0.98 Hz; n = 11, N = 7; peak frequency after light + atropine, 0.21 ± 0.14 Hz; n = 4, N = 3; two-sample t test; p = 0.022).

Coactivity in ensembles of BLA PYRs is important in activating downstream structures and mediating amygdalar behaviors. Theta oscillations are a mechanism by which local activity is synchronized in a circuit. To explore how ACh-induced theta oscillations modulate BLA PYR synchrony, paired recordings of neighboring (within <100 microns) PYRs were made (Fig. 10A). In baseline conditions, neighboring cells exhibited low correlation between fluctuations in their membrane potential (Fig. 10B). After ACh stimulation, theta MPOs driven by large IPSPs greatly synchronized these cells (Fig. 10B). Across 23 pairs of BLA PYRs, 15 pairs (65%) exhibited high (>0.25) cross-correlation of ACh-induced MPOs. The mechanism underlying MPO synchronization in PYR pairs could be explained by large theta IPSCs (Fig. 10C). In a different set of recorded pairs, large theta IPSCs were found to be synchronized across 12 of 19 pairs (63%). In the remaining seven pairs, large IPSCs induced by ACh were present in each cell but not synchronized (7/19, 37%). These results suggest that ACh synchronizes the majority of neighboring BLA PYRs via shared connectivity within local CCK IN circuits but leaves the possibility that there are some PYRs that are differently connected within the local inhibitory circuitry.

Figure 10.

ACh synchronizes BLA PYRs. A, Confocal image showing an example of a dual neighboring PYR recording in the BLA. Scale bar, 50 µm. B, Representative paired recordings of PYRs showing the high cross-correlation of membrane potentials during ACh-induced MPOs that occurs in most, but not all pairs (right; paired t test; p = 6.25 × 10−5; n = 23; N = 12). C, In voltage-clamp recordings, synchronization of ACh-induced large IPSCs can be observed in most cells, providing a mechanism for synchronized MPOs. D, E, Sample recordings showing that when neighboring PYRs are brought to firing threshold, ACh induces an inhibition of firing activity that is followed by an increase in the synchronization of PYR action potentials. F, Synchronization of spiking induced by ACh (n = 10 pairs; N = 8) is blocked in the presence of picrotoxin (n = 3 pairs; N = 3) to block GABAA receptors (two-sample t test; p = 0.01), shown in (G) traces from the same cell pair.

Finally, to address how synchronized MPOs across PYRs could modulate spiking synchronization, paired recordings of neighboring PYRs were given current injections to induce sustained low-frequency firing (range, 2–5 Hz). In baseline conditions, the frequency of synchronized spikes (spikes <20 ms apart) was low (Fig. 10D). ACh stimulation evoked an initial inhibition of firing followed by firing at an increased frequency from baseline (Fig. 10E) in which spiking synchrony across PYR pairs was significantly increased (Fig. 10F). This increase in firing synchrony was blocked by application of picrotoxin to block GABAA receptors (Fig. 10F,G), indicating that the increase in firing synchrony was produced by ACh-induced CCK theta inhibition and could not be explained by an overall increase in spiking output, as firing frequency after light plus picrotoxin was still increased from baseline.

Discussion

ACh plays a vital role in establishing network states in the brain that support attention, memory, and emotional behaviors (Hasselmo and Sarter, 2011; Luchicchi et al., 2014; Wilson and Fadel, 2017). These high ACh states are associated with theta oscillations which bind activity of neuronal ensembles. In the BLA, theta oscillations are critical for emotional behaviors (Paré and Collins, 2000; Seidenbecher et al., 2003; Maratos et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021). However, despite the remarkably dense cholinergic innervation of the BLA, a mechanistic understanding of how ACh acts in the BLA to produce theta oscillations is lacking. Here, our data collectively outline a detailed temporal and cell-specific mechanism by which endogenous phasic ACh release induces theta oscillations in the BLA through a previously undefined microcircuit mechanism (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Summary schematic of the effects of ACh on BLA circuits. A, During periods of low firing of BF cholinergic neurons, SOM INs contribute the largest amount of inhibition in the BLA while BLA PYRs sparsely fire and the LFP exhibits low synchronous activity. After a burst of activity in cholinergic neurons releases ACh into the BLA, there is a cell type-specific shift in the BLA microcircuits that can extend for seconds beyond the cholinergic stimulus. In this circuit state, CCK INs show a robust increase in activity and produce large theta frequency inhibition onto BLA PYRs, synchronizing BLA firing and producing a theta frequency oscillation in the LFP. Importantly, SOM INs are inhibited during this time, which gates the ability of CCK INs to drive the theta oscillation.

SOM INs gate CCK-driven theta oscillations in BLA

While PV INs have been implicated in BLA theta oscillations (Davis et al., 2017; Ozawa et al., 2020; Antonoudiou et al., 2022), it is not clear if other IN populations can also play a role. Similar to PV INs, CCK INs heavily innervate the perisomatic region of BLA PYRs and can modulate fear behavior (Rovira-Esteban et al., 2019). However, the role of CCK INs in network function has remained elusive, largely due to difficulty in genetically targeting these INs (Rovira-Esteban et al., 2019). Intersectional approaches utilizing CCK-Cre lines and inhibition specific-promoters can also label PV INs in the hippocampus (Dudok et al., 2021; Grieco et al., 2023). However, in the BLA, CCK and PV do not show overlapping expression (Mascagni and McDonald, 2003; Andrási et al., 2017), and CCK basket cells uniquely express CB1 receptors on their axon terminals (McDonald and Mascagni, 2001). Thus, utilizing multiple intersectional approaches, including optogenetics, pharmacology, and targeted cell recordings, we show that CCK INs are recruited by cholinergic stimuli to synchronize PYR output and drive theta oscillations in the BLA, establishing a new role for these cells in BLA circuit function. Large CCK-mediated IPSCs induced by ACh contained tightly summated IPSCs, suggesting phasic cholinergic stimulation results in highly synchronized activity in the CCK IN network. This synchronized inhibition was sensitive to CB1 receptor manipulation, indicating it is likely driven specifically by the CCK basket cell network (Katona et al., 1999; Jasnow et al., 2009). Rhythmic inhibition in HPC induced by ACh is also sensitive to CB1Rs (Nagode et al., 2011, 2014), suggesting this cell type could play a similar role in other brain areas. CCK basket cells in the BLA are electrically coupled (Andrási et al., 2017), providing a mechanism by which M3 receptor depolarization can drive synchronized output from this network without the need for glutamatergic signaling.

In the BLA, SOM INs have been implicated in modulating external inputs (Wolff et al., 2014), plasticity (Ito et al., 2020), and feedforward (Guthman et al., 2020) and feedback inhibition (Ünal et al., 2020). Here, we describe a novel role of SOM INs in gating activity of CCK INs to modulate BLA synchronization. SOM INs exhibit high levels of activity in baseline states in cortical circuits in vivo (Klausberger et al., 2003; Leão et al., 2012), and we show this extended to BLA ex vivo. ACh decreased activity in this IN population, directly hyperpolarizing a large subset of these cells. This contrasts with the effects of ACh on SOM INs in other brain areas (Kawaguchi, 1997) but is consistent with decreased BLA SOM activity following systemic physostigmine (Mineur et al., 2022). This ACh-induced reduction in SOM activity shifts the network state in the BLA from high dendritic to strong perisomatic inhibition and allows for a CCK-driven theta oscillation to emerge. Interestingly, our data show that activation of SOM INs in this network state blocks CCK IN oscillatory inhibition, establishing a previously undefined functional relationship between SOM and CCK INs. They also establish that this SOM→CCK IN circuit must be suppressed to allow for CCK-mediated synchronization of BLA PYR theta activity. This provides an important role for ACh in inhibiting SOM INs to allow this network behavior and positions these INs to gate theta oscillations in the BLA. Intriguingly, ACh-mediated inhibition of SOM INs not only gates theta oscillations but also disinhibits PYR dendrites, which may support plasticity on PYR cell dendrites during BLA theta activity (Ito et al., 2020).

ACh shifts control of BLA theta oscillations from PV to CCK INs

PV INs in the BLA are capable of driving theta oscillations (Davis et al., 2017; Ozawa et al., 2020; Antonoudiou et al., 2022). However, we show that although PV IN activity is increased by ACh, PV INs were not involved in BLA theta network activity produced by phasic cholinergic stimulation, despite their involvement in network activity in baseline states. This suggests their involvement in network oscillations in the BLA is state dependent. Unlike the hippocampus (Karson et al., 2009), PV and CCK IN networks in the BLA form parallel circuits without direct synaptic communication (Andrási et al., 2017). While PV and CCK cells have differences in electrophysiological parameters, they equally inhibit BLA PYR firing (Vereczki et al., 2016). In any brain area, there is limited exploration on how complementary PV and CCK IN networks, both innervating the perisomatic region, differentially contribute to circuit dynamics (Dudok et al., 2021). One explanation is that these networks are differentially recruited to circuit function and play a state-dependent role. PV INs receive more glutamatergic inputs than CCK INs, while CCK INs are more sensitive to neuromodulatory control (Freund and Katona, 2007; Armstrong and Soltesz, 2012; Hájos, 2021). Accordingly, external glutamatergic inputs, such as those from cortex, could drive synchronization in BLA through interaction with PV INs. Alternatively, ACh suppresses cortical glutamatergic input (Tryon et al., 2023) and promotes a network state in BLA in which CCK INs internally drive theta oscillations without the need for external glutamatergic input. This suggests externally and internally driven theta oscillations in the BLA could be generated by these competing perisomatic IN networks in a brain state-dependent manner.

However, in the presence of ACh, PV INs show increased excitation in combination with ACh-evoked depolarization of PYRs. This state could generate gamma oscillations in the BLA that are driven by PV→PYR interactions (Headley et al., 2021). In agreement, gamma power was increased in BLA by ACh and while this was not examined in the current study, our results suggest that PV INs could play a role. Interestingly, this could offer separate control of theta and gamma oscillations in the BLA through CCK and PV networks by phasic ACh.

ACh effects on circuit behavior are cholinergic stimulus and brain area specific

BF cholinergic neurons respond to emotionally salient stimuli, resulting in phasic release of ACh into the BLA (Crouse et al., 2020) simultaneously with hippocampal and cortical areas (Teles-Grilo Ruivo et al., 2017). Firing in cholinergic neurons can vary based on the value of salient stimuli (Sturgill et al., 2020), and different ACh levels have been hypothesized to set network states for different functions (Hasselmo and McGaughy, 2004). The BLA receives especially dense cholinergic innervation compared with these other structures (Hellendall et al., 1986; Emre et al., 1993). Here, our data show that induction of theta oscillatory network behavior requires large cholinergic stimuli, and due to this, the same stimulation to cholinergic fibers more reliably recruits the BLA compared with vHPC and PL. This indicates a threshold of ACh must be reached to induce this network behavior, which has intriguing implications. First, depending on the level of innervation by cholinergic fibers, this results in differential effects in target structures by the same cholinergic stimulus, offering important insight into the behavioral effects of ACh signaling. In response to salient stimuli, this positions ACh to more readily induce synchronized theta behavior in the BLA, important for the transmission of valence information. Interestingly, cholinergic stimulation first results in a decrease in BLA network activity. It is possible this serves to reset BLA activity prior to induction of theta oscillations that are generated locally in BLA circuits. Indeed, BLA theta oscillations can lead synchronized behavior in vHPC and PL circuits during emotional processing (Burgos-Robles et al., 2017). It is an intriguing possibility that this is driven by differential cholinergic modulation in these regions. Additionally, stimulus specificity of ACh’s effects on BLA network oscillations could allow only salient stimuli to induce this network state as opposed to weak stimuli that lack strong valence.

Conclusion

Our findings outline the cell-specific circuit mechanism by which endogenous phasic ACh modulates BLA theta oscillations and synchronizes BLA output acting through CCK INs. These results show how ACh modifies inhibitory circuits in the BLA to establish a network state favoring theta oscillations and reveal a previously undefined relationship between CCK and SOM INs that is critical for modulating oscillatory activity. We also show that ACh preferentially impacts BLA circuits over other hippocampal or cortical circuits in this manner. While not the only mechanism by which BLA circuits produce theta oscillations, this likely represents an important mechanism by which BLA theta oscillations are produced in response to presentation of salient environmental stimuli that plays an important role in emotional learning and memory.

References

- Aitta-aho T, Hay YA, Phillips BU, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Paulsen O, Apergis-Schoute J (2018) Basal forebrain and brainstem cholinergic neurons differentially impact amygdala circuits and learning-related behavior. Curr Biol 28:2557–2569.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrási T, Veres JM, Rovira-Esteban L, Kozma R, Vikór A, Gregori E, Hájos N (2017) Differential excitatory control of 2 parallel basket cell networks in amygdala microcircuits. PLoS Biol 15:e2001421. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonoudiou P, et al. (2022) Allopregnanolone mediates affective switching through modulation of oscillatory states in the basolateral amygdala. Biol Psychiatry 91:283–293. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C, Soltesz I (2012) Basket cell dichotomy in microcircuit function. J Physiol 590:683–694. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu TCM, Busti D, Magill PJ, Ferraguti F, Capogna M (2012) Cell-type-specific recruitment of amygdala interneurons to hippocampal theta rhythm and noxious stimuli in vivo. Neuron 74:1059–1074. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio M, Nabavi S, Capogna M (2017) Synaptic plasticity, engrams, and network oscillations in amygdala circuits for storage and retrieval of emotional memories. Neuron 94:731–743. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Robles A, et al. (2017) Amygdala inputs to prefrontal cortex guide behavior amid conflicting cues of reward and punishment. Nat Neurosci 20:824–835. 10.1038/nn.4553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen J, Záborszky L, Heimer L (1985) Cholinergic projections from the basal forebrain to the basolateral amygdaloid complex: a combined retrograde fluorescent and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 234:155–167. 10.1002/cne.902340203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tan Z, Xia W, Gomes CA, Zhang X, Zhou W, Liang S, Axmacher N, Wang L (2021) Theta oscillations synchronize human medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala during fear learning. Sci Adv 7:eabf4198. 10.1126/sciadv.abf4198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouse RB, et al. (2020) Acetylcholine is released in the basolateral amygdala in response to predictors of reward and enhances the learning of cue-reward contingency. Elife 9:e57335. 10.7554/eLife.57335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg H, Pabst M, Braganza O, Schoch S, Niediek J, Bayraktar M, Mormann F, Beck H (2015) Synergy of direct and indirect cholinergic septo-hippocampal pathways coordinates firing in hippocampal networks. J Neurosci 35:8394–8410. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4460-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P, Zaki Y, Maguire J, Reijmers LG (2017) Cellular and oscillatory substrates of fear extinction learning. Nat Neurosci 20:1624–1633. 10.1038/nn.4651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidschstein J, et al. (2016) A viral strategy for targeting and manipulating interneurons across vertebrate species. Nat Neurosci 19:1743–1749. 10.1038/nn.4430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudok B, et al. (2021) Alternating sources of perisomatic inhibition during behavior. Neuron 109:997–1012.e9. 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre M, Heckers S, Mash DC, Geula C, Mesulam M-M (1993) Cholinergic innervation of the amygdaloid complex in the human brain and its alterations in old age and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol 336:117–134. 10.1002/cne.903360110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW (1997) Central cholinergic systems and cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 48:649–684. 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz AC, Beyeler A, Seo C, Leppla CA, Wildes CP, Tye KM (2013) BLA to vHPC inputs modulate anxiety-related behaviors. Neuron 79:658–664. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Katona I (2007) Perisomatic inhibition. Neuron 56:33–42. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielow MR, Zaborszky L (2017) The input–output relationship of the cholinergic basal forebrain. Cell Rep 18:1817–1830. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutagny R, Jackson J, Williams S (2009) Self-generated theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 12:1491–1493. 10.1038/nn.2440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco SF, et al. (2023) Anatomical and molecular characterization of parvalbumin–cholecystokinin co-expressing inhibitory interneurons: implications for neuropsychiatric conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 10.1038/s41380-023-02153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthman EM, Garcia JD, Ma M, Chu P, Baca SM, Smith KR, Restrepo D, Huntsman MM (2020) Cell-type-specific control of basolateral amygdala neuronal circuits via entorhinal cortex-driven feedforward inhibition. Elife 9:e50601. 10.7554/eLife.50601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájos N (2021) Interneuron types and their circuits in the basolateral amygdala. Front Neural Circuits 15:1–17. 10.3389/fncir.2021.687257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A (2015) Central cholinergic neurons are rapidly recruited by reinforcement feedback. Cell 162:1155–1168. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME (2006) The role of acetylcholine in learning and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16:710–715. 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, McGaughy J (2004) High acetylcholine levels set circuit dynamics for attention and encoding and low acetylcholine levels set dynamics for consolidation. Prog Brain Res 145:207–231. 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45015-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Sarter M (2011) Modes and models of forebrain cholinergic neuromodulation of cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:52–73. 10.1038/npp.2010.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headley DB, Kyriazi P, Feng F, Nair SS, Pare D (2021) Gamma oscillations in the basolateral amygdala: localization, microcircuitry, and behavioral correlates. J Neurosci 41:6087–6101. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3159-20.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellendall RP, Godfrey DA, Ross CD, Armstrong DM, Price JL (1986) The distribution of choline acetyltransferase in the rat amygdaloid complex and adjacent cortical areas, as determined by quantitative micro-assay and immunohistochemistry. J Comp Neurol 249:486–498. 10.1002/cne.902490405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito W, Fusco B, Morozov A (2020) Disinhibition-assisted long-term potentiation in the prefrontal-amygdala pathway via suppression of somatostatin-expressing interneurons. Neurophotonics 7:015007. 10.1117/1.NPh.7.1.015007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto LR, Cerqueira JJ, Sousa N (2016) Patterns of theta activity in limbic anxiety circuit preceding exploratory behavior in approach-avoidance conflict. Front Behav Neurosci 10:171. 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow AM, Ressler KJ, Hammack SE, Chhatwal JP, Rainnie DG (2009) Distinct subtypes of cholecystokinin (CCK)-containing interneurons of the basolateral amygdala identified using a CCK promoter-specific lentivirus. J Neurophysiol 101:1494–1506. 10.1152/jn.91149.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE (2020) Arousal and sleep circuits. Neuropsychopharmacol 45:6–20. 10.1038/s41386-019-0444-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalis N, et al. (2016) 4-Hz oscillations synchronize prefrontal-amygdala circuits during fear behavior. Nat Neurosci 19:605–612. 10.1038/nn.4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karson MA, Tang AH, Milner TA, Alger BE (2009) Synaptic cross talk between perisomatic-targeting interneuron classes expressing cholecystokinin and parvalbumin in hippocampus. J Neurosci 29:4140–4154. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5264-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Sperlágh B, Sík A, Käfalvi A, Vizi ES, Mackie K, Freund TF (1999) Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 19:4544–4558. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04544.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y (1997) Selective cholinergic modulation of cortical GABAergic cell subtypes. J Neurophysiol 78:1743–1747. 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Marton LF, Roberts JDB, Cobden PM, Buzsaki G, Somogyi P (2003) Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature 421:844–848. 10.1038/nature01374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão RN, et al. (2012) OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci 15:1524–1530. 10.1038/nn.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Hassani OK, Alonso A, Jones BE (2005) Cholinergic basal forebrain neurons burst with theta during waking and paradoxical sleep. J Neurosci 25:4365–4369. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0178-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesting J, Narayanan RT, Kluge C, Sangha S, Seidenbecher T, Pape HC (2011) Patterns of coupled theta activity in amygdala–hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits during fear extinction. PLoS One 6:e21714. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque M, Avoli M (2018) Carbachol-induced theta-like oscillations in the rodent brain limbic system: underlying mechanisms and significance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 95:406–420. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas EK, Jegarl AM, Morishita H, Clem RL (2016) Multimodal and site-specific plasticity of amygdala parvalbumin interneurons after fear learning. Neuron 91:629–643. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchicchi A, Bloem B, Viaña JNM, Mansvelder HD, Role LW (2014) Illuminating the role of cholinergic signaling in circuits of attention and emotionally salient behaviors. Front Synaptic Neurosci 6:1–10. 10.3389/fnsyn.2014.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratos FA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Rippon G, Senior C (2009) Coarse threat images reveal theta oscillations in the amygdala: a magnetoencephalography study. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 9:133–143. 10.3758/CABN.9.2.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]