Abstract

Gross anatomy is a critical course for the development of a variety of skills such as anatomical knowledge and spatial, critical, and clinical reasoning. There have been few attempts to integrate clinical applications in gross anatomy, with the majority of these being in the lecture hall and not in the laboratory. Clinical cases and guided questions were added to a laboratory manual (Clinically Oriented Laboratory Manuals (COLMs)) in a first-year medical gross anatomy prosection course during COVID-19. The effectiveness of the COLMs was analyzed using in-laboratory assessments between treatment and control groups, as well as student perceptions. There was no significant difference between in-lab assessment scores between students with or without the COLMs in 2020 (t1304.735= 0.647, p ;= 0.518). Student perceptions demonstrated that 61.6% strongly agreed or agreed that the COLMs were a good way to learn anatomy and 32.0% desired more COLMs in the lab. Overall, COLMs did not increase student knowledge by the end of a session. Students thought the COLMs were a good tool to learn anatomy because they helped become more clinically aware; however, students desired better implementation of the COLMs. The addition of COLMs in the laboratory is a potential method to address the need for clinical applications within the gross anatomy laboratory.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-023-01970-1.

Keywords: Gross Anatomy, Cognitive Integration, COVID-19, Gross Anatomy Laboratory, Laboratory Manuals

Introduction

Human gross anatomy has been a foundational discipline in medical education for centuries. Throughout its history, anatomy has become one of the most comprehensive courses within the first two years of medical school. Anatomy is critical to the training of future clinicians as it provides a myriad of skills such as introducing students to anatomic variability; topics of death and dying; practice with dexterity; the language of medicine; communication skills; and enhances students’ clinical and spatial reasoning [1–3]. Medicine requires a detailed knowledge of the three-dimensional shape, spatial orientation, and how the structures are interconnected [4]. The hands-on experience of the gross anatomy laboratory allows students to touch and investigate the three-dimensionality of the body. Through this investigation, students employ critical thinking skills in order to relate pathology to what they view on their “first patient,” the donor [5]. Students also develop interpersonal skills by working as a dissection team and learn anatomy through respectful handling of the donor. The skills learned within the anatomy laboratory are imperative to safe and ethical medical practice [4–5].

Both clinicians and medical students believe that anatomy is critical to learning medicine [5–8]. Clinicians state that anatomy is critical to performing proper physical examinations, accurately diagnosing patients, and communicating with other physicians [9–13]. Despite clinicians’ views about the importance of anatomy, 64% of clinicians feel that students entering the clinic have insufficient anatomical knowledge [14]. Many clinicians, therefore, question why their trainees lack adequate anatomical knowledge [13, 15–17]. Medical students echo the sentiments of clinicians. More than 90% of students rated anatomy as the most fundamental basic science course [12, 18] because of the basic clinical skills and understanding of the human body that anatomy provides [10]. However, many medical students perceive that the anatomy taught in medical school was not sufficient enough to prepare them for the clinic [7, 16, 19–20]. This may be due to the changes that have occurred in anatomy education such as diminished anatomy teaching hours [21] and implementation of a variety of new educational methods [22–23]. In addition to this, the impact of the global pandemic coronavirus (COVID-19) may have an effect that has yet to be investigated [24].

Both clinicians and medical students are calling for anatomy to be taught practically through clinically relevant topics or dissection [5, 9, 25–26]. Teaching anatomy in clinical context is a well-known concept [17]. However, there is limited research concerning integrating anatomy and clinical applications specifically within the gross anatomy laboratory [17, 27]. Therefore, anatomy education is in a quandary about how to teach anatomy most effectively through clinical applications with varying teaching styles and time restrictions [16].

There is no consensus on the most practical way to address this predicament presented to anatomy educators. Currently, anatomy education is faced with four specific challenges: (1) decreased hours for anatomy instruction [21]; (2) value of dissection over other teaching modalities [28]; (3) need for clinical integration in basic sciences; [29]; and (4) providing a safe environment for students during and after COVID-19 [30]. Some attempts to address these concerns have focused on efforts within the classroom by having clinicians present in lecture halls or tacking on clinical applications at the end of lectures. Many institutions are employing curricular changes focusing on active learning such as problem-based learning (PBL), team-based learning (TBL), case-based learning (CBL), and computer-assisted learning (CAL) [13, 31]. These active approaches are student-centered, rather than teacher-centered which is seen in the lecture format [1, 32–33]. These active learning principles are focused more within the classroom setting, rather than the anatomy laboratory. Intentional clinical integration within the laboratory setting is continually being investigated and is not yet fully developed [27].

Some methods have been implemented such as the use of clinical procedures. Rizzolo and colleagues had students prepare for a surgical dissection by reading the dissector notes and answering clinical questions to guide them [29]. Other techniques involved filming clinical procedures on donors and showing them to students [34–35]. Pathologists have also been brought into the laboratory to assist students in determining the cause of death of the donors [36]. Additionally, active learning methods have been utilized to enhance the clinical anatomy experience through TBL sessions separate from the lab [37] or case-based anatomy sessions with imaging and prosections [38].

Implementation of online resources such as viewing their donors’ own computed tomography (CT) scan [39]; computerized dissection manual with links to CT scans, pathological slides, radiology, etc. [39, 40]; and virtual reality [41–44] have also been utilized to increase exposure to clinical applications. Additionally, to draw focus on the donor as a “first patient,” some schools had students make observations of their donors throughout the course and present these later as projects [45–46].

Adding an extra challenge to the already time limited anatomy instruction is COVID-19. Students were required to work online at home or wear facemasks and social distance on campus; thus, creating a barrier to in-person dissection laboratories [30]. Some anatomists moved their sessions to online formats such as virtual dissections, anatomy videos, digital cadaveric images, and video conferencing [47–49]. COVID-19 has presented many challenges to providing an engaging learning environment for students. It also provided introspection for anatomy educators about how anatomy is taught in and outside of the laboratory.

Overall, there is a need to be effective and efficient in anatomy pedagogy, especially with fewer hours devoted to anatomy [21] and traditional methods being questioned [22–23, 50–51]. Understanding basic anatomy and correlating it to clinical cases is a major means to teaching students clinical skills [52]. There is a lot of debate about the most effective tools for teaching anatomy such as prosections vs. dissections, incorporation of active learning methods, use of virtual models, etc. [27–28]. However, there are few adaptations of these methods to focus attention on clinically oriented tools without a complete restructuring of a curriculum. The concept of ‘cognitive integration’ combines basic and clinical sciences within a cognitive learning activity; rather than horizontal or vertical integration that occurs at a curricular level [53]. Use of cognitive integration in medical education can lead to students gaining ‘conceptual coherence,’ which is when concepts have been grouped to make sense for the learner [54]. By integrating at the level of the learning activity, educators can enhance student learning by connecting meaning to the basic knowledge and relating it to their future clinical practice [26]. Cognitive integration has been shown to aid in novice training in diagnostic reasoning [55–59]. This integration is most effective when creating an activity that makes specific and definite connections between basic and clinical sciences [53]. Regarding gross anatomy labs, anatomists should consider what is the most effective way to cognitively integrate clinical applications and basic anatomical knowledge?

There have been no studies to date that have examined the effect of cognitively integrating in a gross anatomy laboratory with a clinical laboratory manual. The current study sought to address some of the challenges anatomists face within the laboratory by examining the effectiveness of Clinically Oriented Laboratory Manuals (COLMs) in a prosection laboratory during COVID-19. This was accomplished by examining the following specific aims:

Describe how gross anatomy students’ knowledge on pre- and post-assessments differs between students with the COLMs (treatment) and those without (control). The hypothesis was that students’ scores on in-laboratory assessments will be significantly higher in the treatment group than the control group.

Describe students’ perceptions of having the COLMs within a prosection course.

Materials and Methods

Course Overview

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC), Medical Gross and Developmental Anatomy is a 14-credit hour course taught within the fall of the first year of medical school. The course is taught in 4 regional blocks: upper limb and back (Block 1); thorax and abdomen (Block 2); pelvis and lower limb (Block 3); and head and neck (Block 4). The 18-week course is combined with embryology and contains a lecture and a lab component. There is a total of 170 h devoted to the course with 120 of these hours spent within the gross anatomy laboratory. The remaining time is spent devoted to didactic lecture, review sessions, and ultrasound and radiology small group sessions. Six faculty members, with the help of graduate teaching assistants, conducted lectures and aided students in identifying anatomical structures in the laboratory. There was a total of 167 students in the Fall of 2020.

Students’ grades were based on 4 written electronic examinations; 4 laboratory practical examinations; 20 online quizzes; and 1 National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject exam taken at the end of the course. The written exams had 100 multiple choice questions, 35 of which pertained to embryology and 65 to anatomy. Practical examinations were administered within the anatomy laboratory. They consisted of 57 questions at 60 stations, with 3 rest stations. Students had one minute to answer the question before moving on to the next station. Due to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), the laboratory and lecture settings were altered in order to ensure student and faculty safety. Lecture was not mandatory, however strongly encouraged. Lecture was in-person for one-third of the class and virtual for the rest of the students via Big Blue Button©, a web conferencing software, to be viewed synchronously or asynchronously. Students attending the in-person lecture were required to wear facemasks and maintain 6 feet distance apart. The majority of the students attended virtually with fewer than 20 students attending in person.

In the anatomy laboratory, there were 11 tables with prosected specimens. The medical student class was divided into 3 groups (A, B, and C). On a given day of scheduled lab, each of these groups attended a laboratory session for one hour. These sessions were mandatory except for students diagnosed positive for COVID-19 and in this case, they were excused. Each individual student had a total of 40 scheduled hours in the lab. Students worked at the 11 tables in groups of 5–6 students to view specimens, identify the list of structures, and work through the lab manual. The room was divided so that one faculty member monitored three dissection tables. Each laboratory table (11) had the same prosection for the students to view. Students were required to wear facemasks, gloves, eye protection, and a laboratory coat. This altered environment resulted in a reduction of the number of students in the lab at one time, 6-feet distancing in the lab, and less time physically in the lab.

Students utilized the Thieme© dissector [60], a modifiable electronic dissection manual, to guide them in the lab. In this manual, students were given the learning objectives for the day, instructions for dissection, and a list of structures to identify. Due to the change from dissection to prosection viewing, students used the dissector to guide them to the identification of anatomical structures, rather than as dissection instructions. During the scheduled laboratory time, there were no specific roles for the students. The students were responsible for determining how to use their time, with no formal instruction or assessment of student involvement. Students had 24/7 access to the laboratory for further studying outside of scheduled lab time.

Creation of COLMs

In order to create the COLMs, research on the most relevant and critical clinical correlations medical students need to master prior to their graduation was conducted [61–63]. Then, these clinical applications were correlated to the students’ required textbook, Gray’s Basic Anatomy, 2e [64].

After determining the pertinent cases for Blocks 1 and 2, eight cases were created (4 for Block 1 concerning the Back and Upper Limb; and 4 for Block 2 concerning the Thorax and Abdomen). Each case contained a patient presentation, applicable clinical findings (e.g., physical examinations, imaging studies), and any additional definitions. The case was added to the beginning of the Thieme© lab module for that day. Throughout the lab manual, guided questions were interspersed with the Thieme© instructions. These questions asked students about the relevant anatomy by connecting the structures they were viewing on the prosection to their knowledge of anatomy and to the patient case. The questions were inserted to promote deeper thinking about the anatomy, facilitate conversation, and guide students to the patient’s diagnosis. The last question in the manual asked students what the patient’s final diagnosis was and what brought them to this diagnosis.

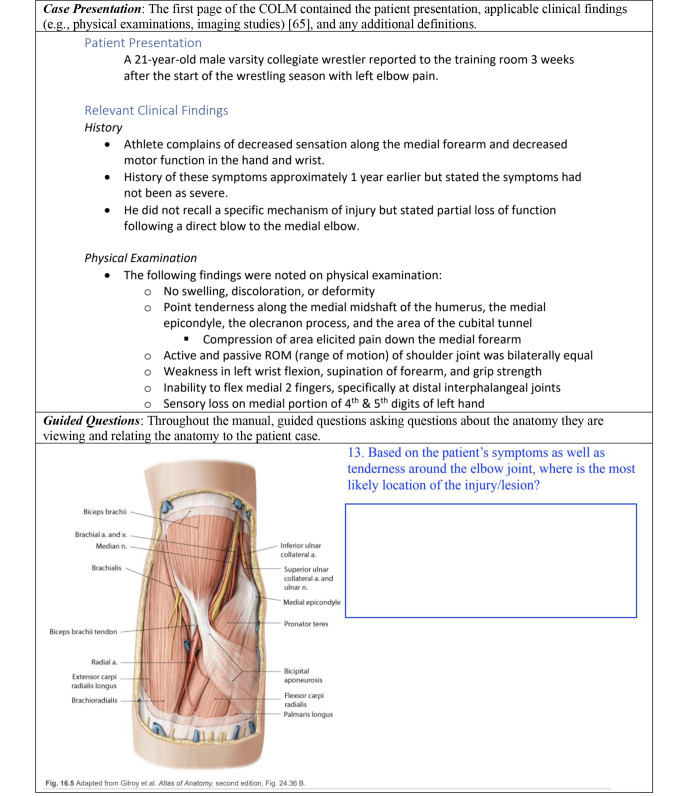

The COLMs were vetted by second-year medical students who had previously taken anatomy in the Fall of 2019 and a panel of expert anatomists. Based on their suggestions and edits, the COLMs were then altered before administration. An example of the COLMs is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A condensed example of a COLM demonstrating the first page of the manual [65] as well as guided questions throughout the COLM

Administration of the COLMs

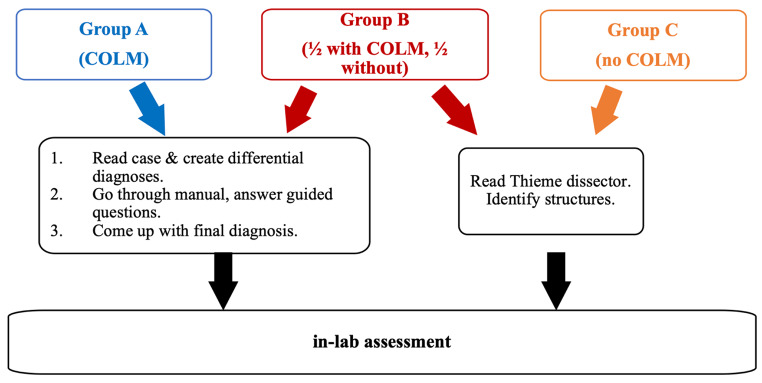

Eight COLMs were administered in the first two blocks of medical gross anatomy. On a day of administration, half of the students received the COLM (treatment), and the other half did not receive the COLM (control). Since there were 3 groups (A, B, and C), group B was divided in half to equally divide the class into treatment and control groups, Fig. 2. In the B group, the treatment and control cohorts were physically separated to avoid the control group members from hearing discussions about the COLMs. Treatment and control groups alternated so that every student had a chance to work with the COLMs.

Fig. 2.

Diagram representing the control and treatment cohorts for the 2020 prosection groups. Those with the COLMs (treatment) would alternate with those without COLMs (control) on a given intervention day

At the beginning of the lab, students in the treatment group got to work on one COLM at a prosection table. Students were instructed to read the case as a group, come up with differential diagnoses, then go through the lab manual by identifying structures and answering the guided questions. Students assigned one person to scribe, or they would rotate opportunities to scribe. In the last 10 min of lab, every student (treatment and control) would take an individual in-lab assessment.

Participation in the study was completely anonymous and voluntary. Students were reassured that their responses on the COLM and in-lab assessments had no effect on their grades and no faculty would view their material. At the end of the laboratory experience, the COLMs and in-laboratory assessment keys were posted on Canvas© to ensure that every student had access to the information before the block exam.

Data Collection

Data were collected from in-laboratory assessments and a survey about student perceptions. The in-lab assessments were created in order to test students’ knowledge after utilizing the COLMs. The in-lab assessment had six multiple choice questions in which students had 5–10 min to complete the assessment at the end of the lab. On the post-assessment survey, there was an additional question to see if the student scribed (i.e., wrote answers within the COLMs) that day. Questions were pulled from Gray’s Anatomy Review book [66] because they were vetted and they correlated with the students’ textbook. The assessment contained three types of questions: (1) anatomy knowledge (structure and function), (2) spatial reasoning ability, and (3) the ability to answer clinical questions, Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of In-Lab Assessment Questions

| Type Question | In-Lab Assessment Question |

|---|---|

| Anatomy Knowledge |

After the orthopedic surgeon examined the MRI of the shoulder of a 42-year-old female, he informed her that the supraspinatus muscle was injured and needed to be repaired surgically. Which of the following is true of the supraspinatus muscle? a.It inserts on the lesser tubercle of the humerus. b.It initiates adduction of the shoulder. c.It is innervated chiefly by the C5 spinal nerve. d.It originates from the lateral border of the scapula. |

| Spatial Ability |

The orthopedic surgeon exposed the muscle in the supraspinous fossa so that she could move it laterally, in repair of an injured rotator cuff. As she reflected the muscle from its bed, an artery was exposed crossing the ligament that bridges the notch in the superior border of the scapula. What artery was this? a.Subscapular b.Transverse cervical c.Dorsal scapular d.Posterior humeral circumflex e.Suprascapular |

| Clinical Question |

A 23-year-old male medical student fell asleep in his chair with Netter’s Atlas wedged into his axilla. When he awoke in the morning, he was unable to extend the forearm, wrist, or fingers. Movements of the ipsilateral shoulder joint appear to be normal. Which of the following nerves was most likely compressed, producing the symptoms described? a.Lateral cord of the brachial plexus b.Medial cord of the brachial plexus c.Radial nerve d.Median nerve e.Lateral and medial pectoral nerves |

Table 1 Examples of the in-lab assessment questions from Gray’s Anatomy Review book [66] which included questions based on anatomy knowledge, spatial ability, and clinical questions.

At the end of administration of the COLMs (at the end of Block 2), students were given a perception survey about the COLMs electronically. Students were asked to rate 8 statements on a Likert scale from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5). The open-ended questions inquired about how the COLMs were useful or not useful and if students had any additional comments.

Data Analysis

For the in-lab assessments, independent sample t-tests were conducted to analyze the differences between students in the control and treatment groups. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the Likert-scale student perceptions data. The free responses from the open-ended questions of the survey were analyzed by thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a qualitative analysis in which codes are generated from statements in order to establish initial themes or potential themes. Then, the initial themes are analyzed and grouped to create main themes [67]. To reduce potential bias and provide various perspectives, two other researchers assisted in the creation of initial and main themes.

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 with a level of significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

In-Lab Assessment

Analyses were conducted between the treatment (students with the COLMs while viewing prosections) and the control (students solely viewing prosections without the COLMs) groups’ performances on in-lab assessments. The mean represents the number of questions answered correctly.

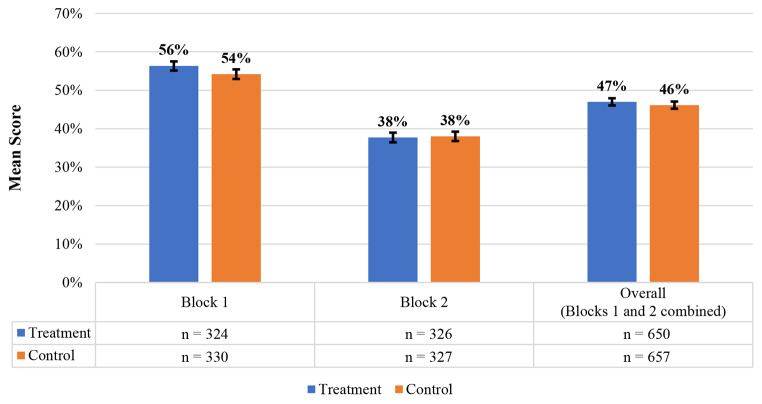

There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment (M = 3.38) and the control (M = 3.25), t650.654 = 1.235, p = 0.217, on the Block 1 overall average in-lab assessments. On Block 2 overall mean in- lab assessment scores, there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment (M = 2.26) and control (M = 2.28), t650.373 = -0.167, p = 0.868. Examining the data of both Block 1 and 2 combined, there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment (M = 2.82) and control (M = 2.77) groups, t1304.735 = 0.647, p = 0.518, Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Overall mean scores on six multiple-choice questions from post-lab assessments from Block 1, Block 2, and Overall (combined Blocks 1 and 2) between the treatment and control groups

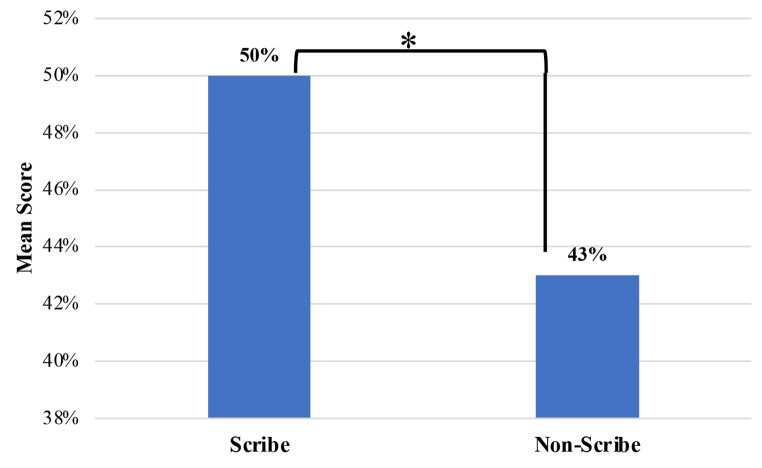

Comparisons were also conducted between students who were scribes (i.e., wrote answers within the COLMs) and students who were not scribes when using the COLMs. There were 113 scribes total for the eight cases, Fig. 4. Combining Blocks 1 and 2, there was a statistically significant difference between the scores of the scribes (M = 3.02) and those who were not scribes (M = 2.58), t221.256 = 2.831, p = 0.005.

Fig. 4.

Overall mean scores on post-lab assessments from combined Blocks 1 and 2 (overall) between scribes and non-scribes. Vertical bars represent ± SEM. * Indicates a statistically significance difference

Student Perceptions

The survey about student perceptions was administered at the end of the Block 2 examination, after the COLM administration. 165 students were in attendance and 126 (76.36%) of them completed the survey. One student left statements 1 and 8 blank. The results of the survey are represented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Medical students’ (n = 126) rating of eight statements concerning their use of the COLMs within the laboratory

| Statement | Strongly Disagree/Disagree n, (%) |

Neutral n, (%) |

Strongly Agree/Agree n, (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Viewing prosections with clinical lab manuals is a good way to learn anatomy. | 16 (12.8) | 32 (25.6) | 77 (61.6) |

| 2 | The clinical lab manuals aided in my understanding of anatomical structures. | 30 (23.8) | 38 (30.2) | 58 (46.0) |

| 3 | The clinical lab manuals helped me become more clinically aware. | 14 (11.1) | 16 (12.7) | 96 (76.2) |

| 4 | I would like to have more clinical lab manuals within the lab. | 50 (39.7) | 35 (27.8) | 41 (32.5) |

| 5 | Viewing prosections with the lab manuals enhanced my gross anatomy lab experience. | 30 (23.8) | 44 (34.9) | 52 (41.3) |

| 6 | Viewing prosections with the clinical lab manuals helped me develop a 3D appreciation of the body. | 31 (24.6) | 40 (31.7) | 55 (43.7) |

| 7 | The clinical lab manuals helped me relate anatomical structure to pathology. | 15 (11.9) | 19 (15.1) | 92 (73.0) |

| 8 | The clinical lab manuals helped me answer clinical questions on the exams. | 29 (23.2) | 27 (21.6) | 69 (55.2) |

To understand the student responses to the Likert scale, students were given two open-ended questions to provide their free responses. The first question asked about ways that the COLM was or was not useful, with 117 students (92.9%) providing responses. The second question was provided for students to give any additional feedback, with 44 students (34.9%) responding to this question. Two new themes were delineated from this question. Themes from the students’ free responses and student exemplar quotes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Themes delineated from student responses to the 2 open-ended questions provided at the end of the perceptions survey with student quotes to supplement the themes

| Question 1: Did you find the clinical lab manuals useful for learning? In what ways were they useful/not useful? | |

| Theme | Student Exemplar Quote |

| Change in implementation | “Would potentially be good as a pre-lab so when we get in there we can find and refer, then have the quiz at the end to see. Also would help if we immediately covered answers after because even though the answers were posted later I generally forgot what I put.” – Student #123 |

| Useful if they had adequate time to complete | “I think they would have been more useful if we didn’t only have an hour in lab. We really only were able to focus on lab or the manual during the short hour. They would have been very helpful if we could have had more time.” – Student #15 |

| Aided in integrating lab, lecture, and clinical concepts | “I think working through the manuals was helpful because it made us think about the clinical implications and see these structures are related as a big picture.” – Student #72 |

| Beneficial if students were familiar with the anatomy | “It was useful in correlating clinical symptoms with identification of major structures, but I often felt my knowledge was not sufficient to fully understand how to answer the questions correctly.” – Student #115 |

| Useful for learning and recall in and out of the laboratory | “Yes, engaging; applications of material helped me with recall of the gross anatomy.” – Student #87 |

| Aided in stimulating group conversation and engagement | “They were useful. It made the course feel more interactive and the information on the packets is some of the information I recalled the most from both lab and lecture.” – Student #114 |

| Ineffective | “No I did not. I found it more overwhelming than useful. Usually, I view lab as primarily a time to identify the structures and understand their relation to one another/functions. I understand the attempt to integrate pathology/clinical presentations, but for me personally, it was too overwhelming to do all at once” – Student #17 |

| Question 2: Any additional comments? | |

| Theme | Student Quote |

| Have multiple scribes for writing answers helps recall | “I would also have maybe one or more people write the answers to the packets. I recalled more when I wrote it.” – Student #119 |

| COLMs provided a beneficial challenge for students | “I’ve taken an anatomy course before and these lab guides would be phenomenally useful.” – Student #78 |

Discussion

Understanding of anatomy is critical to the practice of medicine. However, many clinicians, medical students, and anatomists feel that students entering the clinic have inadequate anatomical knowledge [8, 14, 16]. Therefore, the literature suggests teaching anatomy through cognitive integration, in which both clinical and basic sciences are taught together in order to foster clinical knowledge in anatomy [53–54]. Due to fewer hours devoted to anatomy [21], deviation from traditional methods of anatomy teaching [22–23], and the potential effect of COVID-19 [24], anatomists are looking for effective teaching methods during such challenging circumstances.

In-lab Assessments

The COLMs did not enhance students’ knowledge on an in-lab assessment at the end of the laboratory session. The low in-lab assessment scores may have reflected a variety of issues. Students’ knowledge was variable entering the lab due to a variety of factors such as if they had prior anatomy experience or if they prepared for the lab for the day. Studies have shown that students rarely utilize assigned readings or materials before their laboratory sessions [68–70]; therefore, many students enter the lab unprepared for the day [71]. Additionally, Bickerdike and colleagues found that 47.1% of medical students “cram” one week before an exam and the rest (49.7%) steadily study throughout the course [72]. With minimal to low anatomy knowledge entering the lab, students’ ability to answer in-depth questions may not be feasible by the end of the lab, reflecting the students’ low in-lab scores. This suggests that only surface level knowledge (e.g., identification) may be acquired within the lab setting, not the ability to clinically reason.

The timing of when the COLMs were administered may also have affected the low scores. Students were given the COLMs within the first two blocks of their anatomy course, starting within the second week of their medical school experience. Because of this, students may not have acclimated to the high stress environment of medical school (e.g., increased workload and content, etc.) in order to perform well on the in-lab assessments. Additionally, this potentially was some students’ first time in a cadaver laboratory, adding another layer of anxiety [73–74]. The low in-lab scores within the first two blocks of medical school may be reflective of students acclimating to the large workloads and stresses as well as their first exposure to human cadavers.

Individuals who wrote out answers to the guided questions overall performed better on the in-lab assessments (about 7%) than those who were not scribes. Scribes actively synthesized the information discussed by their dissection groups and then worked to construct an appropriate way to address the question. The strategy of “writing-to-learn” has been utilized to strengthen recall and understanding of material [75–76]. Writing can facilitate knowledge transfer because it encourages active use of the information [77]. Students absorb the information (e.g., from the prosections, their teammates) and synthesize this into a coherent response. Liss and Hanson examined the effect of writing prompts on an undergraduate anatomy and physiology course [78]. Approximately 70% of students stated that they learned more from the writing assignments than multiple choice exams. However, there were no strong correlations between the writing assignments and examination scores [78]. Anatomy is the language of medicine, and by having the scribes engage with the language, those who wrote out answers demonstrated a greater mastery of the information than those that did not scribe.

Student Perceptions

Overall, the students had a positive response to the COLMs within the gross anatomy laboratory. They felt that it was a good way to learn anatomy (61.6%) and that the COLMs aided in their understanding of anatomy (46.0%). There is an overall desire for anatomy to be taught in clinical context to make learning anatomy more interesting and relatable [5, 7, 10, 19, 50, 79–81]. The COLMs connected anatomy to deeper, more relatable information by connecting clinical applications to the basic science of anatomy. Through this connection, the majority of students (76.2%) also felt that the COLMs aided in their clinical knowledge and helped relate anatomy to pathology (73.0%). From thematic analysis, the theme derived from student responses of “aided in integrating lab, lecture, and clinical concepts” supports the Likert scale data. Due to this interrelationship, the COLMs were helpful with recall and integration of material in and outside of the lab. COLMs provided students with an organized, structured study tool to learn clinical applications which has been known to be correlated with better exam performances [72].

Students understood the value of these manuals with their learning; however, they were apprehensive about having more COLMs because of the additional work. Kang and colleagues found comparable results when implementing explicit tasks in the anatomy lab [82]. About 70% of students positively responded to these tasks and 68% stated that the tasks piqued their interest; however, only 25.6% desired more of these tasks [82]. A major theme delineated from thematic analysis was “changes in implementation” such as providing the cases before lab, holding seminars afterwards, allowing students to take the COLMs home, etc. Some other themes correlated with this theme such as the COLMs were “useful if they had adequate time to complete” and “beneficial if students were familiar with the anatomy.” By altering the administration and implementation of the COLMs, it could aid in students desiring more of them in the lab.

Due to COVID-19, gross anatomy was often converted to online and teaching time was reduced [24]. Students’ time in lab was cut from three hours to one hour. They were still required to complete the same amount of material in addition to the COLM and in-lab assessment, even with the time reduction. Students commented that “without COVID rushing everything, I think they would be more effective and enjoyable” (Student #22). Some students also suggested having more knowledge of the basic anatomy would have been more helpful in completing the COLMs. Literature has shown varying results of prior anatomy experiences’ effect on students’ success in gross anatomy with some reporting a positive effect [83–84] and others showing no effect on anatomy performance [85]. Having some basic anatomy knowledge would be helpful before utilizing the COLMs; but even more broadly, it would be helpful for entering the gross anatomy laboratory in general.

Another major theme was that the COLMs “aided in stimulating group conversation and engagement.” Students with the COLMs had a structured environment with defined roles and expectations to discuss the clinical topics and guided questions. The small group dynamic allows others to share ideas and work through complex cases [86]. Small groups that work well can practice utilizing the language of medicine, delivering criticisms and opinions, and listening skills [87]. Clear, structured tasks with defined roles for students can lead to effective small group conversations [87]. The COLMs provided students with a structured task to work with so students could define their roles (e.g., scribe or non-scribe, etc.).

Lastly, the theme of “ineffective” was derived from student responses reflecting the changes in implementation students suggested. Many felt that the COLMs added extra workload to their already overloaded content schedule. Students in their first year are overwhelmed because of content overload and stressful school environment [88]. Thus, adding extra work is not well-received by medical students [82]. The COLMs took up time in a lab which already had time restrictions due to COVID-19, which may have stressed students more. Additionally, the in-lab assessments were sometimes above the level of knowledge that the students had at the time, thus creating more self-doubt and stress in students’ ability to perform [29]. Overall, there is a limit to what students can know and learn in a short period of time, which corresponds with cognitive load theory (CLT). CLT states that humans have a limited capacity for working memory (i.e., short-term memory) and if given excessive information, information overload occurs [89]. The COLMs seemed to increase cognitive load in the laboratory due to the multitude of tasks to complete in one hour. The COLMs may have asked too much of year one students, in a COVID environment, and with one hour to try to apply newly exposed anatomical information to clinical questions. Many of the implementation changes that the students suggested could be utilized in order to eliminate these issues such as reducing the number of guided questions, providing students with the manuals beforehand, and giving them more time.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study was the global pandemic COVID-19, which resulted in major changes to the laboratory experience and the utilization of the COLMs. The manuals were originally designed for a dissection course. Due to COVID-19, the laboratory setting was altered to a prosection course so that students were in the lab for less time. However, this demonstrates the flexibility of the COLMs—they can be utilized in multiple lab formats. Additionally, students had reduced time in the laboratory, with the time decreased significantly by two-thirds. With only 1 h to identify structures, work through the COLMs, and answer an in-lab assessment, students felt rushed and overwhelmed. This affected students’ experience with the COLMs therefore causing the COLMs to be viewed as a hindrance by some students rather than an aid. Students’ scores on the in-lab assessment reflected this, with many students not having enough time to adequately complete the assessment.

Another limitation was the in-laboratory assessment which appeared to be above students’ knowledge level. COLMs were designed with the thought that students had some basic understanding of the region that they were examining in lab that day. However, many students seemed unprepared entering the lab, studying only close to the block exams; thus, rendering the COLMs inadequate because students did not understand the basic anatomy in order to apply it. Additionally, the engagement with the COLMs would vary dependent on other variables such as other exams that day or if students were generally overwhelmed. Lastly, this is one study from one medical school in which the results may not be transferable to all universities.

Future Directions

The implementation of the COLMs in the lab could be altered based on the suggestions of students and its limitations. Students could be given the COLM before lab or given pre-lab work to focus on the basic anatomy they need to have before entering the lab. This could attenuate students’ knowledge disparity when entering the lab. Pre- and post-laboratory assessments could be administered to assess the effect of the COLMs on clinical knowledge acquisition during a laboratory session. There could be discussions or seminars after the COLMs with the faculty or clinicians about the cases in the COLMs to answer any questions or to clarify the case. Students also could be given more time in the lab (more than one hour) so that they can fully complete the COLMs.

The manuals additionally could be administered in a dissection course or in a course utilizing virtual anatomy resources. The COLMs are highly adaptable to a variety of formats and courses (e.g., histology microscopic lab guides). They also can be utilized in an integrated curriculum by adding more information from other courses to tie into anatomy. Additionally, clinicians could be added into the lab sessions with theses manuals to hone in on the clinical importance of the cases in relation to the anatomy.

The COLMs also could include instructions for students to practice clinical skills; for example, listening for heart sounds and practicing use of ultrasounds. The manuals also could involve instructions utilizing other learning modalities such as virtual reality and imaging to provide students with multiple learning perspectives. Examinations of how students use the manuals outside of lab could also be investigated. Lastly, how the COLMs affect students’ practical and written examinations could also be explored.

Conclusion

The COLMs were an innovative tool for gaining exposure to clinical applications in the lab, however they did not increase knowledge during the laboratory session. Contrasting the initial hypothesis, students’ scores on in-laboratory assessments were not significantly higher when students had the COLMs. This may have resulted because of students’ variable knowledge of the basic anatomy entering the lab. If students did not understand the basic anatomy, it would be difficult to comprehend detailed clinical applications. The manual potentially provided students with a structured study tool that students could utilize in and out of the lab. The COLMs may have led to cognitive overload because of the COVID environment, one hour to complete all their tasks, and working through detailed clinical questions. Examination of students’ perceptions demonstrated that the students positively received the manuals and understood their value; however, they desired better implementation.

The COLMs provided students with a tool to cognitively integrate clinical applications into the gross anatomy laboratory. Based on the findings of this study, medical educators should consider implementing critical thinking tools that are achievable for students to promote students’ overall learning and cognitive integration.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Drs. Audra Schaefer, Erin Dehon, and Eddie Perkins for their assistance with developing the study; Drs. Casey Boothe and Andrew Ferriby for assistance in thematic analysis; and the students and faculty who graciously participated in this study.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All research for this study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Institutional Review Board (protocol 2020-0051).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Older J, Anatomy A must for teaching the next generation. The Surgeon. 2004;2:79–90. doi: 10.1016/S1479-666X(04)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korf HW, Wicht H, Snipes RL, Timmermans JP, Paulsen F, Rune G, Baumgart-Vogt E. The dissection course–necessary and indispensable for teaching anatomy to medical students. Ann Anat. 2008;190:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dissabandara LO, Nirthanan SN, Khoo TK, Tedman R. Role of cadaveric dissections in modern medical curricula: a study on student perceptions. Anat Cell Biol. 2015;48:205–12. doi: 10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegarty M, Keehner M, Cohen C, Montello DR, Lippa Y. The role of spatial cognition in medicine: applications for selecting and training professionals. Applied Spatial Cognition. Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 285–315.

- 5.Sbayeh A, Choo MAQ, Quane KA, Finucane P, McGrath D, O’Flynn S, O’Mahony SM, O’Tuathaigh CM. Relevance of anatomy to medical education and clinical practice: perspectives of medical students, clinicians, and educators. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5:338–46. doi: 10.1007/s40037-016-0310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orsbon CP, Kaiser RS, Ross CF. Physician opinions about an anatomy core curriculum: a case for medical imaging and vertical integration. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:251–61. doi: 10.1002/ase.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed K, Rowland S, Patel V, Khan RS, Ashrafian H, Davies DC, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Paraskeva PA. Is the structure of anatomy curriculum adequate for safe medical practice? The Surgeon. 2010;8:318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorgich EAC, Sarbishegi M, Barfroshan S, Abedi A. Medical students knowledge about clinical importance and effective teaching methods of anatomy. Shiraz E Medical J. 2017;18. 10.5812/semj.14316.

- 9.Arráez-Aybar LA, Sánchez-Montesinos I, Mirapeix RM, Mompeo-Corredera B, Sañudo-Tejero JR. Relevance of human anatomy in daily clinical practice. Ann Anat. 2010;192:341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho MJ, Hwang Y. Students’ perception of anatomy education at a Korean medical college with respect to time and contents. Anat Cell Biol. 2013;46:157–62. doi: 10.5115/acb.2013.46.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarus MD, Chinchilli VM, Leong SL, Kauffman GL., Jr Perceptions of anatomy: critical components in the clinical setting. Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:187–99. doi: 10.1002/ase.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali A, Khan ZN, Konczalik W, Coughlin P, El Sayed S. The perception of anatomy teaching among UK medical students. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97:397–400. doi: 10.1308/rcsbull.2015.397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papa V, Vaccarezza M. Teaching anatomy in the XXI century: new aspects and pitfalls. Sci World J. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/310348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waterston SW, Stewart LJ. Survey of clinicians’ attitudes to the anatomical teaching and knowledge of medical students. Clin Anat. 2005;18:380–4. doi: 10.1002/ca.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moxham BJ, Plaisant O. Perception of medical students towards the clinical relevance of anatomy. Clin Anat. 2007;20:560–4. doi: 10.1002/ca.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald JEF, White MJ, Tang SW, Maxwell-Armstrong CA, James DK. Are we teaching sufficient anatomy at medical school? The opinion of newly qualified doctors. Clin Anat. 2008;21:718–24. doi: 10.1002/ca.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergman EM, Van Der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. Why don’t they know enough about anatomy? A narrative review. Med Teach. 2011;33:403–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.536276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pabst R, Rothkötter HJ. Retrospective evaluation of a medical curriculum by final-year students. Med Teach. 1996;18:288–93. doi: 10.3109/01421599609034179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemeir MA. Attitudes and views of medical students toward anatomy learnt in the preclinical phase at King Khalid University. J Fam Commun Med. 2012;19:190. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.102320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triepel CPR, Koppes DM, Van Kuijk SMJ, Popeijus HE, Lamers WH, Van Gorp T, Futterer JJ, Kruitwagen RFPM, Notten KJB. Medical students’ perspective on training in anatomy. Ann Anat. 2018;217:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBride JM, Drake RL. National survey on anatomical sciences in medical education. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(1):7–14. doi: 10.1002/ase.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roxburgh M, Evans DJ. Assessing anatomy education: a perspective from design. Anat Sci Educ. 2021;14(3):277–86. doi: 10.1002/ase.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guimarães B, Dourado L, Tsisar S, Diniz JM, Madeira MD, Ferreira MA. Rethinking anatomy: how to overcome challenges of medical education’s evolution. Acta Med Port. 2017;30(2):134–40. doi: 10.20344/amp.8404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franchi T. The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: a student’s perspective. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13:312–5. doi: 10.1002/ase.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxham BJ, Moxham SA. The relationships between attitudes, course aims and teaching methods for the teaching of gross anatomy in the medical curriculum. Eur J Anat. 2007;11:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CF, Mathias HS. What impact does anatomy education have on clinical practice? Clin Anat. 2011;24:113–9. doi: 10.1002/ca.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estai M, Bunt S. Best teaching practices in anatomy education: a critical review. Ann Anat. 2016;208:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson AB, Miller CH, Klein BA, Taylor MA, Goodwin M, Boyle EK, Brown K, Hoppe C, Lazarus M. A meta-analysis of anatomy laboratory pedagogies. Clin Anat. 2018;31:122–33. doi: 10.1002/ca.22934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rizzolo LJ, Rando WC, O’Brien MK, Haims AH, Abrahams JJ, Stewart WB. Design, implementation, and evaluation of an innovative anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:109–20. doi: 10.1002/ase.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Dumont AS, Tubbs RS. A review of anatomy education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: revisiting traditional and modern methods to achieve future innovation. Clin Anat. 2021;34:108–14. doi: 10.1002/ca.23655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolmans DH, De Grave W, Wolfhagen IH, Van Der Vleuten CP. Problem based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Med Educ. 2005;39:732–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bransford JD, Brown AL, Cocking RR. How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and School. Committee on developments in the Science of Learning in. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen D, Tanner K. Infusing active learning into the large-enrollment biology class: seven strategies, from the simple to complex. Cell Biol Educ. 2005;4:262–8. doi: 10.1187/cbe.05-08-0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzpatrick CM, Kolesari GL, Brasel KJ. Teaching anatomy with surgeons’ tools: Use of the laparoscope in clinical anatomy. Clin Anat. 2001;14:349–53. doi: 10.1002/ca.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson DR, Nava PB. Medical student responses to clinical procedure teaching in the anatomy lab. Clin Teach. 2010;7:14–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2009.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rae G, Cork JR, Karpinski AC, McGoey R, Swartz W. How the integration of pathology in the gross anatomy laboratory affects medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29:101–8. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1194761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huitt TW, Killins A, Brooks WS. Team-based learning in the gross anatomy laboratory improves academic performance and students’ attitudes toward teamwork. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8:95–103. doi: 10.1002/ase.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drake RL. A unique, innovative, and clinically oriented approach to anatomy education. Acad Med. 2007;82:475–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803eab41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami T, Tajika Y, Ueno H, Awata S, Hirasawa S, Sugimoto M, Kominato Y, Tsushima Y, Endo K, Yorifuji H. An integrated teaching method of gross anatomy and computed tomography radiology. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:438–49. doi: 10.1002/ase.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeves RE, Aschenbrenner JE, Wordinger RJ, Roque RS, Sheedlo HJ. Improved dissection efficiency in the human gross anatomy laboratory by the integration of computers and modern technology. Clin Anat. 2004;17:337–44. doi: 10.1002/ca.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elizondo-Omaña RE, Morales‐Gómez JA, Guzmán SL, Hernández IL, Ibarra RP, Vilchez FC. Traditional teaching supported by computer‐assisted learning for macroscopic anatomy. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2004;278:18–22. doi: 10.1002/ar.b.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugand K, Abrahams P, Khurana A. The anatomy of anatomy: a review for its Modernization. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:83–93. doi: 10.1002/ase.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson A, Hazzard M, Challman SD, Morgenstein AM, Brueckner JK. A second life for gross anatomy: applications for multiuser virtual environments in teaching the anatomical sciences. Anat Sci Educ. 2011;4:39–43. doi: 10.1002/ase.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel SB, Mauro D, Fenn J, Sharkey DR, Jones C. Is dissection the only way to learn anatomy? Thoughts from students at a non-dissecting based medical school. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4:259–60. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0206-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenstein A, Vaisman L, Johnston-Cox H, Gallan A, Shaffer K, Vaughan D, O’Hara C, Joseph L. Integration of basic science and clinical medicine: the innovative approach of the cadaver biopsy project at the Boston University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2014;89:50–3. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meredith MA, Clemo HR, McGinn MJ, Santen SA, DiGiovanni SR. Cadaver rounds: a comprehensive exercise that integrates clinical context into medical gross anatomy. Acad Med. 2019;94:828–32. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brassett C, Cosker T, Davies DC, Dockery P, Gillingwater TH, Lee TC, Milz S, Parson SH, Quondamatteo F, Wilkinson T. COVID-19 and anatomy: stimulus and initial response. J Anat. 2020;237:393–403. doi: 10.1111/joa.13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longhurst GJ, Stone DM, Dulohery K, Scully D, Campbell T, Smith CF. Strength, weakness, opportunity, threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13:301–11. doi: 10.1002/ase.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byrnes KG, Kiely PA, Dunne CP, McDermott KW, Coffey JC. Communication, collaboration and contagion:virtualisation of anatomy during COVID-19. Clin Anat. 2021;34:82–9. doi: 10.1002/ca.23649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell R, Batty L. Undergraduate perspectives on the teaching and learning of anatomy. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:118–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizzolo LJ, Stewart WB, O’Brien M, Haims A, Rando W, Abrahams J, Dunne S, Wang S, Aden M. Design principles for developing an efficient clinical anatomy course. Med Teach. 2009;28:142–51. doi: 10.1080/01421590500343065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elizondo-Omaña RE, López SG. The development of clinical reasoning skills: a major objective of the anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1:267–8. doi: 10.1002/ase.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kulasegaram KM, Martimianakis MA, Mylopoulos M, Whitehead CR, Woods NN. Cognition before curriculum: rethinking the integration of basic science and clinical learning. Acad Med. 2013;88:1–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a45def. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy GL, Medin DL. The role of theories in conceptual coherence. In: Margolis E, Laurence S, editors. Concepts: core reading. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 425–58. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woods NN, Brooks LR, Norman GR. The value of basic science in clinical diagnosis: creating coherence among signs and symptoms. Med Educ. 2005;39:107–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woods NN, Neville AJ, Levinson AJ, Howey EH, Oczkowski WJ, Norman GR. The value of basic science in clinical diagnosis. Acad Med. 2006;81:124–27. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200610001-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baghdady MT, Carnahan H, Lam EW, Woods NN. Integration of basic sciences and clinical sciences in oral radiology education for dental students. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:757–63. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.6.tb05527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goldszmidt M, Minda JP, Devantier S, Skye AL, Woods NN. Expanding the basic sciences debate: the role of physics knowledge in interpreting clinical findings. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17:547–55. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baghdady MT, Pharoah MJ, Regehr G, Lam EW, Woods NN. The role of basic sciences in diagnostic oral radiology. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:1187–93. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thieme [Computer software]. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. 2013. Retrieved from: https://www.thieme.com/.

- 61.Leonard RJ. A clinical anatomy curriculum for the medical student of the 21st century: gross anatomy. Clin Anat. 1996;9:71–99. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1996)9:2<71::AID-CA1>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McHanwell S, Davies DC, Morris J, Parkin I, Whiten S, Atkinson M, Dyball R, Ockleford C, Standring S, Wilton J. A core syllabus in anatomy for medical students-adding common sense to need to know. Eur J Anat. 2007;11:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Educational Affairs Committee, American Association of Anatomists. Gross anatomy learning objectives for competency-based undergraduate medical education. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.anatomy.org/AAA/Resources/Anatomical-Competencies.aspx.

- 64.Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM, Tibbitts R, Richardson P, Horn A. Gray’s Basic anatomy. 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruce SL, Wasielewski N, Hawke RL. Cubital tunnel syndrome in a collegiate wrestler: a case report. J Athl Train. 1997;32(2):151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loukas M, Tubbs RS, Abrahams PH, Carmichael SW. Gray’s Anatomy Review. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- 67.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burchfield CM, Sappington J. Compliance with required reading assignments. Teach Psychol. 2000;27(1):58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sappington J, Kinsey K, Munsayac K. Two studies of reading compliance among college students. Teach Psychol. 2002;29:272–4. doi: 10.1207/S15328023TOP2904_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clump MA, Bauer H, Bradley C. The extent to which psychology students read textbooks: a multiple class analysis of reading across the psychology curriculum. J Instr Psychol. 2004;31.

- 71.Hannon K. Utilization of an educational web-based mobile app for acquisition and transfer of critical anatomical knowledge, thereby increasing classroom and laboratory preparedness in veterinary students. Online Learn. 2017;21:201–8. doi: 10.24059/olj.v21i1.882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bickerdike A, O’Deasmhunaigh C, O’Flynn S, O’Tuathaigh C. Learning strategies, study habits and social networking activity of undergraduate medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:230. doi: 10.5116/ijme.576f.d074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evans EJ, Fitzgibbon GH. The dissecting room: reactions of first year medical students. Clin Anat. 1992;5:311–20. doi: 10.1002/ca.980050408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dinsmore CE, Daugherty S, Zeitz HJ. Student responses to the gross anatomy laboratory in a medical curriculum. Clin Anat. 2001;14:231–6. doi: 10.1002/ca.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McCrindle AR, Christensen CA. The impact of learning journals on metacognitive and cognitive processes and learning performance. Learn Instr. 1995;5:167–85. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00010-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wiley J, Voss JF. The effects of playing historian on learning in history. Appl Cogn Psychol. 1996;10:63–S72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199611)10:7<63::AID-ACP438>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bereiter C, Scardamalia M. The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liss JM, Hanson SD. Writing to learn in anatomy and physiology of the Speech and hearing mechanisms. Center for Interdisciplinary Studies of Writing, University of Minnesota; 2003.

- 79.Pabst R. Gross anatomy: an outdated subject or an essential part of a modern medical curriculum? Results of a questionnaire circulated to final-year medical students. Anat Rec. 1993;237:431–3. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092370317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhangu A, Boutefnouchet T, Yong X, Abrahams P, Joplin R. A three year prospective longitudinal cohort study of medical students’ attitudes toward anatomy teaching and their career aspirations. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:184–90. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092370317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meral Savran M, Tranum-Jensen J, Frost Clementsen P, Hastrup Svendsen J, Holst Pedersen J, Seier Poulsen S, Arendrup H, Konge L. Are medical students being taught anatomy in a way that best prepares them to be a physician? Clin Anat. 2015;28:568–75. doi: 10.1002/ca.22557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kang SH, Shin JS, Hwang YI. The use of specially designed tasks to enhance student interest in the cadaver dissection laboratory. Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:76–82. doi: 10.1002/ase.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Forester JP, McWhorter DL, Cole MS. The relationship between premedical coursework in gross anatomy and histology and medical school performance in gross anatomy and histology. Clin Anat. 2002;15:160–4. doi: 10.1002/ca.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peterson CA, Tucker RP. Undergraduate coursework in anatomy as a predictor of performance: comparison between students taking a medical gross anatomy course of average length and a course shortened by curriculum reform. Clin Anat. 2005;18:540–7. doi: 10.1002/ca.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robertson EM, Thompson KL, Notebaert AJ. Perceived benefits of anatomy coursework prior to medical and dental school. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13:168–81. doi: 10.1002/ase.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ganguly PK. Teaching and learning of anatomy in the 21st century: direction and the strategies. Open Med Educ J 3. 2010.

- 87.Jaques D. Teaching small groups. BMJ. 2003;326:492–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sweller J. Cognitive load theory. In: Jose P. Mestre, Brian H. Ross, editors. Psychology of learning and motivation. Academic Press. 2011; Vol. 55, pp. 37–76.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.