Abstract

Introduction

Medium-term clinical outcome data are lacking for cyanoacrylate glue (CAG) ablation for symptomatic varicose veins, especially from the Asian population.

Objectives

Aim was to determine the 3-year symptomatic relief gained from using the VenaSeal™ device to close refluxing truncal veins from the Singaporean ASVS prospective registry.

Methods

The revised Venous Clinical Severity Score (rVCSS) and three quality of life (QoL) questionnaires were completed to assess clinical improvement in venous disease symptoms along with a dedicated patient satisfaction survey. 70 patients (107 limbs; 40 females; mean age of 60.9 ± 13.6 years) were included at 3 years.

Results

At 3 years, rVCSS showed sustained improvement from baseline (5.00 to 0.00; p < 0.001) and 51/70 (72.9%) had improvement by at least 2 or more CEAP categories.

Freedom from reintervention was 90% and 85.7% patients were extremely satisfied with the treatment outcome. No further reports of further hypersensitivity reactions after one year.

Conclusion

The 3-year follow-up results of the ASVS registry demonstrated continued and sustained clinical efficacy with few reinterventions following CAG embolization in Asian patients with chronic venous insufficiency.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Registration: NCT03893201.

Keywords: VenaSeal™ closure system, Endovenous, Cyanoacrylate closure, Varicose vein, Chronic venous insufficiency

Introduction

A Singapore VenaSeal™ real world post-market evaluation Study (ASVS) evaluated the clinical efficacy of the VenaSeal™ Closure System (VSCS) (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) to ablate symptomatic refluxing truncal veins. ASVS showed that the technology was safe in 100 Asian patients and was associated with high efficacy in terms of truncal closure, technical success and patient satisfaction at the 2 week, 3- and 12- month intervals [1, 2]. However, the UK National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) currently still recommend thermal ablation as first-line endovenous treatment modalities for symptomatic superficial truncal saphenous vein incompetence [3] despite the fact that there is now level 1 evidence from the US VeClose RCT showing non-inferiority of the VSCS compared to radiofrequency ablation, in terms of successful incompetent great saphenous vein (GSV) occlusion and symptom improvement was sustained to 5 years [4]. The aim was to report 3 year clinical outcomes from the ASVS registry.

Methods

ASVS was a real-world, prospective, single arm, multi-centre, multi-investigator trial investigating the use of VSCS in a cohort of multi-ethnic Asian patients with symptomatic chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins from Singapore. Study design, inclusion, exclusion criteria, procedural and peri-operative care protocols and outcomes through 12 months have been previously described [1]. Patients of Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy and pathophysiology (CEAP) classification 2–5 were included. Ethical approval was gained from the Institution Review Board of both centres and informed consent was gained from all participants.

Outcome of interest was clinical improvement at 3 years, assessed on the basis of change in revised Venous Clinical Severity Score (rVCSS) and CEAP. In addition, patients completed 3 quality of life surveys—EuroQol-5 Dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D), Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ) and Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality life Questionnaire-14 (CIVIQ-14) [5]. Occurrence, severity of any further adverse events and reinterventions were documented. Patients completed a brief questionnaire about treatment satisfaction and whether they would have the operation again if required to, which has been previously described in detail [1]. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to perform Duplex ultrasound confirmation of anatomical closure, unless there was a clinical need for potential reintervention.

Results

Seventy out of the original one hundred patients were included (40 (57.1%) females, 107 limbs, 68 (63.6%) bilateral GSV ablation) with a mean age of 66.4 ± 11.9 years. Majority were Chinese (51/70; 72.9%). Patient demographics/ clinical variables are summarized in Table 1. As previously reported, there was 100% technical success rate and no device-related complications during truncal vein embolization.

Table 1.

ASVS baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Number of subjects at Baseline (n = 100) | Number of subjects at 12 m (n = 90) | Number of subjects at 36 m (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 41 | 37 (41.1) | 30 (42.9) |

| Female | 59 | 53 (58.9) | 40 (57.1) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 60.1 ± 12.8 | 60.7 ± 12.8 | 60.9 ± 13.6 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 26.7 ± 4.58 | 26.6 ± 4.65 | 26.2 ± 4.32 |

| Ethnic Group | |||

| Chinese | 71 | 64 (71.1) | 51 (72.9) |

| Malay | 11 | 9 (10.0) | 8 (11.4) |

| Indian | 16 | 16 (17.8) | 10 (14.3) |

| Others | 2 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.43) |

| Smoking | |||

| Smoker | 9 | 6 (6.7) | 4 (5.71) |

| Non-Smoker | 84 | 78 (86.7) | 63 (90.0) |

| Former Smoker | 7 | 6 (6.7) | 3 (4.29) |

| Primary Symptoms | |||

| Pain | 37 | 32 (35.6) | 24 (34.3) |

| Aching | 43 | 33 (36.7) | 25 (35.7) |

| Swelling | 57 | 52 (57.8) | 39 (55.7) |

| Heaviness | 46 | 45 (50.0) | 29 (41.4) |

| Burning | 2 | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.00) |

| Itch | 26 | 24 (26.7) | 14 (20.0) |

| Others | 30 | 4 (4.4) | 22 (31.4) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 45 | 40 (44.4) | 31 (44.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 37 | 33 (36.7) | 24 (34.3) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 16 | 14 (15.6) | 11 (15.7) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 6 | 5 (5.6) | 4 (5.71) |

| CEAP category | |||

| C2 (varicose veins) | 24 | 20 (22.2) | 15 (21.4) |

| C3 (edema) | 33 | 30 (33.3) | 25 (35.7) |

| C4a (pigmentation/eczema) | 32 | 28 (31.1) | 21 (30.0) |

| C4b (lipodermatosclerosis) | 4 | 4 (4.4) | 3 (4.29) |

| C5 (healed venous ulcer) | 7 | 7 (7.8) | 3 (4.29) |

| Duration of Varicose Veins (months), median (IQR) | 24.00 (7.75–60.0) | 24.00 (7.00–60.0) | 24.0 (6.00 – 60.0) |

| Distribution of Truncal Endovenous Ablation | (n = 151 legs) | (n = 138 legs) | (n = 107 legs) |

| GSV | 49 (32.5%) | 41 (29.7%) | 35 (32.7) |

| Bilateral GSV | 96 (63.6%) | 92 (66.7%) | 68 (63.6) |

| SSV | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.93) |

| Combined unilateral GSV and SSV or ATV | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (2.9%) | 3 (2.80) |

| Total number of truncal veins treated | (n = 156 veins) | (n = 142 veins) | (n = 110veins) |

| GSV | 150 (96.2) | 137 (96.5) | 106 (96.4) |

| SSV | 5 (3.2) | 4 (2.82) | 4 (3.64) |

| ATV | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

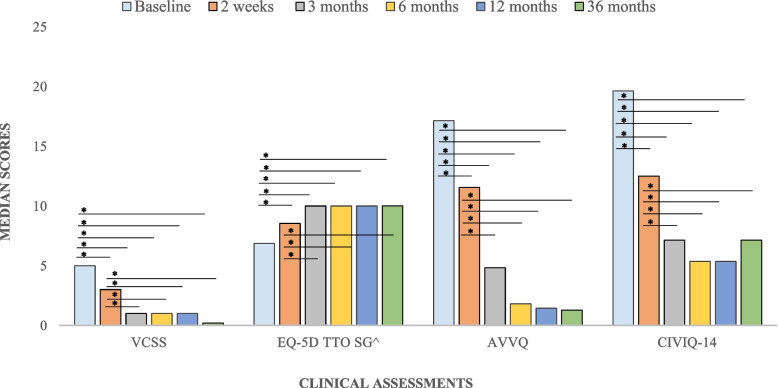

The median follow-up period was 41.5 (IQR 38.8 – 43.9) months. Median rVCSS showed sustained improvement from baseline through to 36 months (5.00 to 0.00; p < 0.001) (Table 2). Figure 1 and Table 2 summarize rVCSS, AVVQ, CIVIC-14 and EQ-5D scores at baseline, 2 weeks, 3, 6,12 and 36 months visits. Improvement in all four measures was statistically significant and sustained between baseline and at all timepoints (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Follow-up clinical assessments

| Assessments | Median (IQR) | P value (baseline –2 weeks/3/6/12/36 months) | P value (2 weeks – 3/6/12/36 months) | P value (3 – 6/12 /36 months) | P value (6 – 12/36 months) | P value (12–36 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCSS | ||||||

| Baseline | 5.00 (4.00–7.00) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 weeks | 3.00 (2.00–5.00) | < 0.001* | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 1.00 (0.00–3.00) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | - | - | - |

| 6 months | 1.00 (0.00 – 2.00) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.910 | - | - |

| 12 months | 1.00 (0.00 – 3.00) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.369 | 0.938 | - |

| 36 months | 0.00 (0.00 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.999 | 0.782 | 0.256 |

| EQ-5D TTO SG | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.686 (0.430 – 0.890) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 weeks | 0.854 (0.700 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 1.00 (0.854 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | 0.0015* | - | - | - |

| 6 months | 1.00 (0.854 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | 0.018* | 0.985 | - | - |

| 12 months | 1.00 (0.890 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | 0.006* | 0.999 | 0.945 | - |

| 36 months | 1.00 (0.838 – 1.00) | < 0.001* | 0.404 | 0.553 | 0.902 | 0.413 |

| AVVQ | ||||||

| Baseline | 17.1 (11.1–25.4) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 weeks | 11.6 (5.90–19.3) | 0.0004* | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 4.83 (0.00–9.78) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | - | - | - |

| 6 months | 1.81 (0.00–6.68) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.651 | - | - |

| 12 months | 1.45 (0.00–10.7) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.653 | 1.00 | - |

| 36 months | 1.29 (0.00 – 5.39) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.579 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| CIVIQ-14 | ||||||

| Baseline | 19.64 (12.05–28.57) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 weeks | 12.50 (7.14–16.96) | < 0.001* | - | - | - | - |

| 3 months | 7.14 (0.00–13.39) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | - | - | - |

| 6 months | 5.357 (0.00–12.05) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.910 | - | - |

| 12 months | 5.357 (0.00–10.71) | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.369 | 0.939 | - |

| 36 months | 7.14 (0.00–10.71) | < 0.001* | 0.0002* | 0.999 | 0.782 | 0.255 |

VCSS Venous Clinical Severity Score, EQ-5D EuroQol-5 Dimension, TTO time trade-off, AVVQ Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire, CIVIQ-14 Chronic Venous Insufficiency quality life Questionnaire-14

*Significant at p < 0.05 when compared to baseline values

Fig. 1.

^ scaled up by 10 for presentation purposes. *p < 0.05

There was a significant improvement of CEAP score at 3 years compared to baseline (median 1 (IQR 0–2) from 3 (IQR 3–4); p < 0.05) and 51/70 (72.9%) had improvement by at least 2 or more CEAP categories (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in CEAP classification

| Baseline (n = 100) | 3 Years (n = 70) | |

|---|---|---|

| CEAP Classification | ||

| C0 (Asymptomatic) | 0 | 33 (47.1) |

| C1 (Reticular Veins) | 0 | 12 (17.1) |

| C2 (Varicose Veins) | 24 | 8 (11.4) |

| C3 (Edema) | 33 | 5 (7.1) |

| C4 (Skin Changes) | 36 | 11 (15.7) |

| C5 (Healed venous ulcer) | 7 | 1 (1.4) |

| Median CEAP (IQR) | 3 (3 – 4) | 1 (0 – 2) |

| Improvement in CEAP | ||

| Worsened by ≥ 1 category | - | 4 (5.7) |

| Unchanged | - | 10 (14.3) |

| Improved by ≥ 2 category | - | 51 (72.9) |

There were no further hypersensivity or phlebitic episodes reported after one year (Table 4). 4/70 (5.7%) and 13/70 (18.6%) developed new and recurrent symptoms respectively. However, only 3 (4.2%) patients required reintervention between the 1–3 year timepoints (one deep vein interrogation and iliac vein stenting for non thrombotic iliac vein compression syndrome and 2 patients for progression of below the knee great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux). Overall freedom from reintervention at three – years was 63/70 (90.0%). We had previously reported 8/90 (8.9%) patients who complained of a pulling sensation during walking or exercise between the 3 and 12 months follow-up visits because of the fibrosed GSV cord located just below the skin in predominantly thin females, following CAG embolization. By 3 years, only 2/70 (2.9%) were still reporting this symptom. At 3 years, 60/70 (85.7%) were very or extremely satisfied with their treatment outcome and 62/70 (88.6%) would probably or definitely recommend this type of treatment to their next of kin or friend if required (Table 5).

Table 4.

Adverse events & reinterventions

| Adverse events | 12 months (n = 90) | 36 months (n = 70) |

|---|---|---|

| Allergic Skin Reaction (Redness/itch) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pulling Sensation | 8 (8.9) | 2 (2.9) |

| Newly Developed | ||

| Heaviness | 3 (3.3) | 2 (2.9) |

| Swelling | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) |

| Hyperpigmentation | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) |

| Recurrence of symptoms | ||

| Varicosities | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.3) |

| Heaviness | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.3) |

| Swelling | 3 (3.3) | 7 (10.0) |

| Ulcers | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Further Interventions for CVI | 5 (5.6) | 7 (10.0) |

| Deep Vein Interrogation | 4 (80.0) | 4 (57.1)a |

| Mean time to Deep Vein Interrogation procedure, months (± SD) | 7.6 ± 3.2 | 11.4 ± 7.6 |

| Superficial Vein Ablation | 1 (20.0) | 3 (42.9)b |

| Mean Time to SVA procedure, months (± SD) | 7.1 (NA) | 17.6 ± 1.0 |

aOne new IVUS/stenting procedure between 1–3 years timepoints

bTwo new below the knee GSV ablation for new symptomatic reflux

Table 5.

Patient satisfaction

| Satisfaction criteria | Percentage of subjects n(%) |

|---|---|

| Extremely/Very Satisfied | |

| Baseline | - |

| 2 weeks | 66/100 (66.0) |

| 3 months | 72/91 (79.0) |

| 6 months | 74/90 (82.2) |

| 12 months | 78/90 (86.7) |

| 36 months | 60/70 (85.7) |

| Definitely/Probably recommend | |

| Baseline | - |

| 2 weeks | 76/100 (76.0) |

| 3 months | 79/91 (87.0) |

| 6 months | 79/90 (87.8) |

| 12 months | 81/90 (90.0) |

| 36 months | 62/70 (88.6) |

| Appearance much/somewhat improved | |

| Baseline | - |

| 2 weeks | 69/100 (69.0) |

| 3 months | 60/91 (66.0) |

| 6 months | 59/90 (65.6) |

| 12 months | 70/90 (77.8) |

| 36 months | 58/70 (82.9) |

| Symptoms much/somewhat improved | |

| Baseline | - |

| 2 weeks | 73/100 (73.0) |

| 3 months | 83/91 (91.0) |

| 6 months | 86/90 (95.5) |

| 12 months | 85/90 (94.4) |

| 36 months | 64/70 (91.4) |

Discussion

The ASVS registry showed a sustained clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction after VenaSeal™ ablation through 3 years. There were few reinterventions since one year and the worrying pulling phenomenon prevalence we had reported previously had reduced. These data are in keeping with the 3-year efficacy and safety results from the first-in-human use of cyanoacrylate glue for GSV incompetence [6], the European multicentre eScope registry [7] and the 5-year US VeClose RCT [4], which all assessed the utility of the VSCS for varicose veins and the only studies to date with medium term results published. Our study has the advantage of recruiting a purely Asian cohort albeit with no Duplex-defined anatomical closure confirmation of the axial vein at the three year time-point because of the COVID-19 crisis, which led to many patients being unable to come back for their dedicated follow-up. However, it does reinforce the sustained clinical effect and improvement of QoL of CAG closure at the medium term in Asian CVI patients. The reintervention rate was low (< 5%) and the majority were for new below the knee GSV reflux, which had not been present at the initial Duplex scan when the patients had first enrolled into the study. It was also encouraging that there were no reinterventions for recanalizations. The persistent clinical benefit was further indicated by continued patient satisfaction scores (> 85%). Those who were not extremely satisfied or would not happily recommend the procedure did not complain of any adverse events related to the procedure such as a hypersensitivity reaction or thrombophlebitis but were more neutral and not on the extreme opposite end because of new or recurring leg symptoms requiring further imaging or investigations. The pulling sensation rate of the fibrotic cord created after CAG embolization of the more superficial GSV in thin women seen in 8.9% patients at the one year follow-up had reduced at 3 years (2.9%). It is thought that CAG does not produce significant thrombosis because the vein walls are immediately coapted to the medical adhesive by the application of external compression resulting in an inflammatory and eventual fibrotic reaction rather than a thrombotic one [8]. This may well delay the fibrotic reaction leading to the patient still feeling the “inflamed” GSV longer than if the truncal vein were blocked using a thermal ablation technique.

Limitations of the study include 30% of patients were unable to be contacted during this time and lack of truncal occlusion data by Duplex ultrasound because of the COVID-19 crisis making it difficult for research patients to come to the hospital for imaging. We plan to address this when we perform 5-year ASVS data analysis.

Conclusion

The 3-year follow-up results of the ASVS registry demonstrated continued and sustained clinical efficacy with few reinterventions following CAG embolization in Asian patients with chronic venous insufficiency.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AVVQ

Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire

- CAG

Cyanoacrylate Glue

- CEAP

Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology Classification

- CIVIQ

Chronic Venous Insufficiency Quality of Life Questionaire

- CVI

Chronic Venous Insufficiency

- EQ5D

EuroQol-5 Dimension questionnaire

- GSV

Great Saphenous Vein

- QoL

Quality of Life

- rVCSS

Revised Venous Clinical Severity Score

Authors’ contributions

TYT researched the literature and conceived the study. TYT, CJQY, SXYS, VBXK, ETCC and TTC was involved in gaining ethical approval, patient recruitment, and data collection. SLC was involved in data analysis and interpretation. TYT drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ASVS study was kindly supported with investigator-initiated funding from Medtronic.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Singhealth Central Institutional Review Board approved this study (CIRB ref number: 2017/2087). Informed consent was sought from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TYT/CTT has received physician initiated grants and speaking honoraria from Medtronic; otherwise the authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tang TY, Yap CJQ, Chan SL, et al. Early results of an Asian prospective multicenter VenaSeal real-world postmarket evaluation to investigate the efficacy and safety of cyanoacrylate endovenous ablation for varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9:335–345 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang TY, Yap CJ, Soon SX, et al. One-year outcome using cyanoacrylate glue to ablate truncal vein incompetence: a Singapore VenaSeal real-world post-market evaluation study (ASVS) Phlebology. 2021;36:609–619. doi: 10.1177/02683555211013678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsden G, Perry M, Kelley K, et al. Diagnosis and management of varicose veins in the legs: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;347:f4279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison N, Gibson K, Vasquez M, et al. Five-year extension study of patients from a randomized clinical trial (VeClose) comparing cyanoacrylate closure versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of incompetent great saphenous veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8:978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuet ML, Lane TR, Anwar MA, et al. Comparison of disease-specific quality of life tools in patients with chronic venous disease. Phlebology. 2014;29:648–653. doi: 10.1177/0268355513501302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida JI, Javier JJ, Mackay EG, et al. Thirty-sixth-month follow-up of first-in-human use of cyanoacrylate adhesive for treatment of saphenous vein incompetence. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proebstle T, Alm J, Dimitri S, et al. Three-year follow-up results of the prospective European multicenter cohort study on cyanoacrylate embolization for treatment of refluxing great saphenous veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida JI, Min RJ, Raabe R, et al. Cyanoacrylate adhesive for the closure of truncal veins: 60-day swine model results. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;45:631–635. doi: 10.1177/1538574411413938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA).