Abstract

Patient: Male, 36-year-old

Final Diagnosis: MR-induced tattoo reaction

Symptoms: Burning sensation • edema • erythema • papular skin lesion • skin lesion

Clinical Procedure: Magnetic resonance imaging

Specialty: Dermatology • Nuclear Medicine • Radiology

Objective:

Unknown etiology

Background:

Over the past 30 years, painful reactions during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in tattooed individuals have been sporadically reported. These complications manifest as burning pain in tattooed skin areas, occasionally with swelling and redness, often leading to termination of the scanning. The exact cause is unclear, but iron oxide pigments in permanent make-up or elements in carbon black tattoos may play a role. Additionally, factors like tattoo age, design, and color may influence reactions. The existing literature lacks comprehensive evidence, leaving many questions unanswered.

Case Report:

We present the unique case of a young man who experienced recurring painful reactions in a recently applied black tattoo during multiple MRI scans. Despite the absence of ferrimagnetic ingredients in the tattoo ink, the patient reported intense burning sensations along with transient erythema and edema. Interestingly, the severity of these reactions gradually decreased over time, suggesting a time-dependent factor contributing to the problem. This finding highlights the potential influence of pigment particle density in the skin on the severity and risk of MRI interactions. We hypothesize that the painful sensations could be triggered by excitation of dermal C-fibers by conductive elements in the tattoo ink, likely carbon particles.

Conclusions:

Our case study highlights that MRI-induced tattoo reactions may gradually decrease over time. While MRI scans occasionally can cause transient reactions in tattoos, they do not result in permanent skin damage and remain a safe and essential diagnostic tool. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind these reactions and explore preventive measures.

Keywords: Skin Temperature, Safety Management, Nociceptors, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Electromagnetic Phenomena

Introduction

Over the past 3 decades, instances of tattooed individuals having painful adverse events during MRI have been sporadically reported in the medical literature. These skin reactions are commonly described as agonizing burning or stinging sensations directly in the tattooed skin, occasionally followed by mild edema and erythema. Symptoms are often transient, with full remission within 2 days. So far, no permanent distortion or damage to tattoos or surrounding skin has been documented [1]. As these events are rare but likely underreported [2], numerous questions remain unanswered, leaving the pathological mechanism unsubstantiated. These reactions can occur in both permanent make-up and regular decorative tattoos. In permanent make-up, the use of iron oxide pigments, sometimes containing the ferrimagnetic substance magnetite, has been proposed as the culprit ingredient for MRI interactions [3]. The formation of artifacts from permanent eye-liners or eyebrows during MRI scans of the head region is a recognized phenomenon [4,5]. Controversially, regular carbon black tattoos with no signs of metallic content have also been documented to cause painful skin reactions, thus raising the question of 2 independent pathophysiological pathways [6,7].

Various predisposing factors, including tattoo age, design, and coloration, have been considered. Currently, darker shades appear to be more prone to MRI reactions. Conductive materials, particularly those in elongated shapes such as sensor leads, are more susceptible to radio frequency (RF)-induced thermal heating during MRI scans, known as the “antenna effect.” It has been hypothesized that spiral tattoos can form conductive loops, thereby increasing the risk of thermal reactions, but the current literature does not offer evidence to support this hypothesis [8]. Since the available reports are derived from individual scans, the temporal aspect of the problem has been insufficiently represented in the data to warrant a study [1].

We present the case of a young man who endured recurring fiery burning pain in a newly applied black tattoo during MRI examinations. Uniquely, this is the first time a patient with MRI-induced tattoo reactions has been prospectively followed across a series of scans. Concurrently, a doctor trained in dermatology continuously monitored the skin and surface temperatures during and after MRI, while histological examinations were conducted on collected skin biopsies. The composition of the applied ink was chemically characterized from the skin biopsies using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX).

Prior to the publication of the case report and any accompanying images, we obtained written informed consent from the patient.

Case Report

A 36-year-old White man was referred for clinical evaluation at the Department of Dermatology, following a severe, painful reaction in a 3-week-old tattoo during an MRI scanning. The patient was suffering from lumbar radiculopathy, which caused sensory disturbances in his left leg. Since 2017, he had undergone 6 spinal surgeries and 15 related MRI scans without any issues before the current incident.

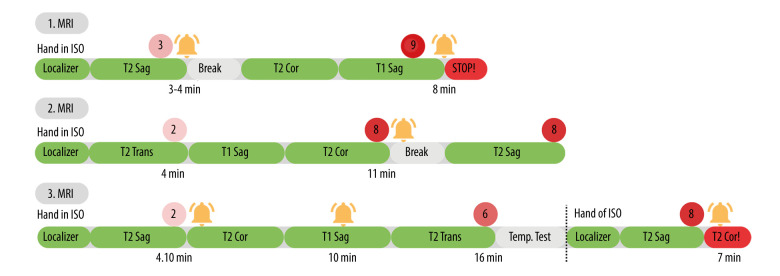

First MRI Scanning – 6.10.22

The patient underwent scanning in a GE Optima MR450W clinical 1.5T MRI, with his hands positioned in the iso-centre (Table 1). Upon entering the static magnetic field (SMF) of the scanner, he had no initial reactions. However, 3 min into the scan, he experienced a rising sensation of burning pain in his left dorsal hand where a 3-week-old tattoo was located. He alerted the staff, and the procedure was briefly interrupted. The patient retrospectively reported a visual analog scale (VAS) pain rating of 3. When the coronal T2 scan was resumed, the burning pain became more intense. His left hand felt noticeably warm, as if “someone was pouring boiling water on i”, with a VAS of 8–9. During the T1 FSE Sagittal sequence, the pain became unbearable, leading the patient to stop the scan after a total of 8 min (Figure 1). The pain abated soon after the scanning was halted. Edema and erythema were observed in the tattooed and surrounding skin of the left hand by both the patient and MRI technicians; however, photographs were not taken. Interestingly, none of his other tattoos were affected during the MRI scan.

Table 1.

The scanning protocol data derived from the 3 distinct MRI evaluations.

| 1st scan– GE Optima MR450 W, 1.5T, Date: 6.10.22 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Localizer | T2 FRFSE Sag | T2 FRFSE Cor | T1 FSE Sag | T2 FRFSE Ax |

| Scan time [m: s] | 0: 16 | 3.29 | 2: 17 | 3: 42 | Scanning stopped |

| TR [ms] | N/A | 4087 | 3906 | 319 | – |

| TE [ms] | 80 | 102 | 110 | 10.23 | – |

| Flip angle [°] | 90 | 160 | 160 | 160 | – |

| Voxels [mm] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – |

| Slice thickness [mm] | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 | – |

| Fov [mm] | 48 | 30 | ?? | 30 | – |

| Wb-sar | 1.45 | 1.13 | 0.97 | 1.47 | – |

| B1-RMS [µt] | 3.60 | 2.94 | 2.82 | 2.70 | – |

| 2nd scan – Siemens, Magnetom Avanto, 1.5T, date: 8.12.22 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Localizer | T2 TSE Sag | T2 TSE Cor | T1 TSE Sag | T2 TSE Ax/Trans |

| Scan Time [m: s] | 0: 24 | 2: 29 | 3: 31 | 3: 33 | 3: 37 |

| TR [ms] | 4,20 | 3000 | 605,0 | 3150 | 3220 |

| TE [ms] | 2,38 | 82 | 11 | 90 | 90 |

| Flip angle [°] | 6 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Voxels [mm] | 1.7×1.7×1.7 | 0.7×0.7×3 | 0.4×0.4×0.4 | 0.7×0.7×4 | 0.7×0.7×4 |

| Slice thickness [mm] | 1,7 | 3,0 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Fov [mm] | 400 | 220 | 280 | 280 | 280 |

| Wb-sar | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| B1-RMS [µt] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3rd scan – Philips, Ingenia Ambition, 1.5T, Date: 19.1.23 (TEST) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Localizer | T2 Dixon Sag | T2 3D cor | T1 Sag | T2 Trans |

| Scan time [m: s] | 0: 28 | 2: 55 | 5: 32 | 03: 10 | 1: 49 |

| TR [ms] | 22.9 | 2500 | 1300 | 441 | 2484 |

| TE [ms] | 3.9 | 90 | 129 | 8 | 120 |

| Flip angle [°] | 45 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Voxels [mm] | 1.39×1.39×10 | 0.67×0.67×4 | 0.42×0.42×0.7 | 0.34x×0.34×4 | 0.6×0.6×4 |

| Slice thickness [mm] | 10 | 4 | 1.40 | 4 | 4 |

| FOV [mm] | 400×400 | 260×299 | 160×280 | 160×298 | 200×200 |

| Wb-SAR [W/kg] | 0.33 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 1.55 | 1.55 |

| B1-RMS [µt] | 1.53 | 2.63 | 1.63 | 3.31 | 4.24 |

N/A – not available.

Figure 1.

Timeline of MRI Sessions. The bell icon denotes the activation of the alarm. Numbered red circles indicate the visual analog scale (VAS) of pain. Green bars represent the scanning sequence, red bars the stopped sequence.

Back at home, the patient noticed the formation of nodules within his tattoo. The erythema and edema resolved within 3–4 days, and the nodules disappeared after 2 weeks. Once the skin fully recovered, the patient noticed a tightening sensation over his left dorsal hand, which intensified when flexing his fingers.

First Clinical Evaluation – 24.11.22

Five weeks after the initial event, all objective symptoms had disappeared, but the sensation of skin tightening over the dorsal hand endured.

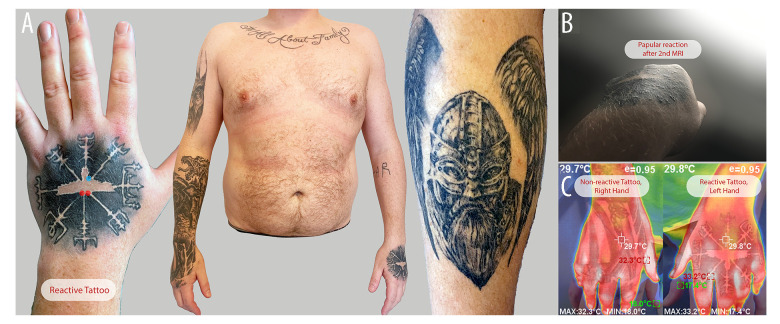

The tattoo in question was a black and white Nordic Helm of Awe design, measuring 8.5×9 cm, which covered most of the patient’s left dorsal hand (Figure 2A). The skin was heavily adorned with dense black pigment, centrally highlighted with white. The central outline appeared off-white and uneven, and was intermittently dotted with small red spots. The patient asserted that those red spots emerged after the MRI mishap and that the white had taken on a more yellowish hue. Despite the reaction, all tattoos displayed no discernible skin thickening, papules, nodules, or any discoloration or pigment blow-out.

Figure 2.

(A) Overview of the patient’s tattoos. Left dorsal hand, reactive tattoo (early October 2022). Red circles indicate initial biopsy locations; the blue circle shows the second biopsy site post-MRI. The broader view depicts tattoos on the right arm (mid-2021 to early 2022), upper-chest lettering (2017), and a right leg tattoo (late 2021). (B) Reactive tattoo, a few days after the second MRI. The patient reported multiple papules in a follicular pattern within the black tattoo. The photo was taken by the patient in natural daylight. (C) IR thermography of the right versus left hand tattoo after the MRI test session. There was no significant thermal difference between the 2 hand tattoos.

The patient also had 8 older decorative tattoos that covered approximately 9% of his skin, as quantified by hand surfaces [9]. All tattoos were in black/greyish colors drawn by the same professional artist in Copenhagen from 2017 to mid-2022. All the tattoo inks used were produced prior to the European legislation on tattoo inks was enacted. Unfortunately, the tattoo parlour was unable to disclose any information regarding the manufacturer of these inks [10].

A single-blind test was performed to evaluate the magnetic properties of the pigment in the reactive tattoo, as earlier defined [5,7]. This involved exposing the tattooed skin to a randomly varying magnetic field from a whiteboard magnet (0.03T), handheld neodymium magnets (0.3T or 0.5T), or a plastic dummy block in a single-blinded manner. No visual symptoms were observed, but the patient subjectively reported mild paresthesia radiating to the 5th finger when exposed to the 2 strongest magnets. When the 0.5T neodymium magnets were moved in a spiral pattern above the tattoo, mimicking a dynamic magnetic field, the patient reported heightened buzzing sensations compared to when the magnet was held statically above the hand. As reference, the tattoo on his right dorsal hand was tested, resulting in no sensations.

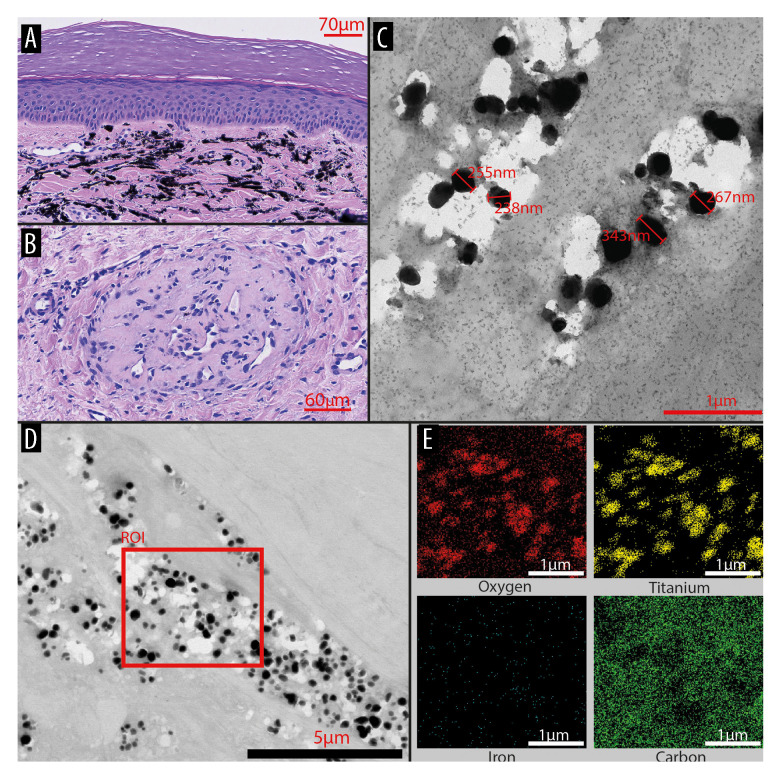

Two punch biopsies were taken from the inner region of the tattoo, including areas with both black and white pigment (red dots, Figure 2A). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining revealed clusters of melanophages containing pigment in the upper dermis, accompanied by very slight perivascular lymphocytic inflammation. Apart from that, there were no significant histo-logical changes, and no iron deposition was detected by iron staining (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Histology of the reactive tattoo following the first MRI adverse event, scale bar 70 μm. (B) The thrombosed vessel showing signs of angiogenesis, taken from a biopsy after the third MRI session, scale bar 60 μm. (C) TEM image of the tattoo pigment particles sized 243–343 nm, scale bar 1 μm. (D) STEM image displaying clusters of pigment, scale bar 5 μm. The red rectangle highlights the selected region of interest (ROI) for EDX analysis. (E) Elements such as oxygen, titanium, iron, and carbon are identified within the region of interest, scale bar 1 μm.

Prepared cobber slot grids with samples were loaded onto the STEM detector for a Quanta FEG 200 SEM (Thermo Fisher) and inserted into the microscope. Bright-field STEM images were acquired with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. EDX were acquired using an Oxford Instruments 80 mm2 X-Max silicon drift detector and elemental maps were generated for areas of interest.

The STEM-EDX analysis of the tattooed skin samples detected no significant amounts of ferrimagnetic metals, such as iron. However, clusters of carbon black pigment and a substantial quantity of titanium dioxide, referred to as white pigment, were identified (Figure 3D, 3E). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) revealed spherical, electron-dense tattoo particles with sizes ranging from 238 to 343 nm (Figure 3C)

Second MRI Scanning – 08.12.22

The patient was urgently admitted to the Department of Spine Surgery due to worsening back pain and diminished motor function of the left lower extremity. Consequently, an MRI was scheduled to evaluate the need for acute surgery.

The patient was scanned in a Siemens Magnetom Avanto, 1.5T, with his hands in the iso-center. As in the previous event, a stinging pain developed within 3 min, gradually intensifying over time. As the scanning progressed from a T1-weighted sagittal to a T2-weighted axial sequence, the patient triggered the alarm 11 min into the procedure, reporting a pain level of 7–8 VAS. No palpable warmth of the skin or observable skin symptoms occurred. Cold dressings were applied to alleviate the pain during the break. Given the scanning’s crucial role in assessing the risk of future surgery, the patient decided to endure the remaining 6 min of scanning. The pain persisted until the completion of the MRI. Surprisingly, no visible skin lesions immediately appeared, but 2 days later, papular lesions in a follicular pattern emerged in the black pigmented areas of the tattoo, without any accompanying symptoms (Figure 2B). The papular lesions spontaneously resolved after approximately 2 weeks.

Second Clinical Evaluation and MRI Test Session – 17.01.23

The patient experienced persistent skin tightening of the left hand. As the pain from the previous 2 scans had been intolerable, he considered having the tattoo removed. However, the tattoo’s anatomical location made dermabrasion or ablative laser removal unattractive due to the thin skin, proximity to extensor tendons, and the significant risk of severe scarring from the procedure. Thus, an MRI test session was arranged to evaluate whether the intensity of the tattoo reaction was decreasing over time. To elicit reactions, an MRI protocol similar to that used for the lumbar column was scheduled (Table 1, Figure 1). Prior to scanning, the surface skin temperature was measured using an infrared (IR) temperature scanner (Dermatemp TM, Exergen, Watertown, MA) and IR thermography.

No reaction occurred when entering the SMF. The patient was positioned in a Philips Ingenia Ambition, 1.5T with his hands in the iso-center. No pain was experienced during the localizer sequence. After 4: 10 min, during the T2-weighted sagittal sequence, pain began to increase, rated 3 VAS. At 7 min, during the coronal T2, the patient showed restless motor movements in his hand. At 9: 56 min, the patient alerted the personnel and reported increasing pain in his left hand, though still tolerable, at VAS 5–6. At 13: 54 min, the patient became restless with his left hand, reporting a pain level of 8 on the VAS. He managed to complete the scanning without extended breaks, only reporting his sensations to the personnel via the communication system. After scanning, a dermatology resident (K. Alsing) thoroughly examined the skin. No objective skin symptoms were seen of the left dorsal hand, nor palpable warmth of the skin compared to the opposite side. No significant skin surface temperature difference was found from multiple measurements made 10–20 s after the scanning ceased (minimum-maximum temperature right hand: 29.5–30.5°C, left hand: 28.5–29.1°C) and the IR thermography (right: 29.8°C, left: 29.7°C) (Figure 2C).

After a break of 5 min, the patient was positioned with his hand above his head, with the reactive tattoo off the iso-center, and an identical MRI program was initiated. Two min after scanning started, the pain struck. During the T2-weighted sagittal sequence, the patient pressed the alarm and stopped the scanning as the pain became too intense. Yet again, no visible skin symptoms appeared, and no measurable temperature difference was detected between the bilateral dorsal hands, which would be indicative of a thermal burn.

A skin biopsy was prepared for HE staining after the MRI test (blue circle, Figure 2A). Like the previous biopsy, it revealed no significant histopathological abnormalities, except for minor signs of perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and melanophages containing pigment. However, the most notable observation was a thrombosed vessel showing signs of angiogenesis, suggesting that the thrombosis had occurred some time ago (Figure 3A, 3B).

Discussion

This paper presents a case of MRI-induced cutaneous reactions in an ordinary black tattoo, showing that these events can evolve in both nonferrous decorative tattoos and permanent make-up tattoos [7]. Importantly, no ferrimagnetic contamination was detected in the applied ink, as confirmed by STEM-EDX analysis. Only carbon black and titanium dioxide were detected in the tattoo skin biopsies. This is the first time an interdisciplinary team of relevant physicians has prospectively followed the development of a reactive tattoo from a series of MRI scans, thus monitoring the possible time-dependent factors of the problem (Figure 1).

Objective skin symptoms, such as erythema and edema, only emerged during the first scanning, but sensory pain persisted with a slight decrease in intensity from the initial to the last scanning. Thus, we believe that the density of pigment particles in the skin must be a predisposing factor for the severity and risk of the MRI interaction. Searching the recent literature, we found that the mean age of the tattoo was around 2.2 years (4 weeks to 10 years, SD 2.8 years) old when the events occurred, although the data are not available in some papers (8 out of 19). If reported, 45.5% (5 out of 11) of the events occurred within the first year after tattooing, and 81.8% (9 out of 11) within the first 3 years. Only 2 events developed 7–10 years after tattooing [1,7]. Hence, it is plausible to infer that the likelihood of experiencing adverse events is most pronounced when the tattoo has been recently applied, specifically within a 3-year timeframe preceding the first MRI. The observations from prospectively evaluating our patient suggest that a recently acquired tattoo may have an increased risk of severe pain, along with skin erythema and edema. Subsequently, the symptomatology gradually transitions over time to become solely subjective due to local pigment breakdown and wash-out, as observed in Alsing et al [7]. It has been estimated that pigment concentration in the skin decreases by 87% to 99% over the years, but the rate at which this occurs remains largely unexplored [11]. However, it is not possible to determine a specific threshold or critical age at which MRI interference occurs based on the limited and scattered data provided [1].

Our findings highlight the co-occurrence of another pathological mechanism of MRI-induced tattoo reactions apart from a consequence of magnetic iron oxide-based pigments. No magnetic components were detected, either by iron staining or STEM-EDX. This observation indicates that conductive elements in the tattooed skin, likely carbon particles, may drive the cutaneous reactions, perhaps via dermal C-fibers, thus triggering pain. A recent publication visualized clusters of black tattoo pigment located near a dermal nerve fiber using TEM, suggesting a higher risk of excitation during MRI [7].

Subjective skin symptoms are well-documented in patient with sensitive skin [12]. These often include sensations like burning and stinging and skin tightening, attributed to external stress-ors activating transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, leading to fiery pain, and proposed neurogenic inflammation by cytokine release [13]. A similar mechanism pathway may explain the burning sensations and erythema in tattooed skin during MRI. In our patient, mild inflammation was observed in the tissue biopsy obtained after the MRI sessions. If isolated neural provocation is the primary mechanism, no permanent complications can arise in the tattooed skin, in conformity with the literature [1,7].

On the other hand, this case demonstrates that possible long-term effects might emerge, as skin tightening and papules of the dorsal hand were reported after MRI. The exact etiology of these symptoms is unknown and could be random findings coinciding with the event, possibly due to heightened awareness. However, it has been determined that these symptoms are relatively harmless, and not an outcome of thermal induction. Our measurements of skin surface temperature detected no significant increase after the MRI procedure, thereby excluding a thermal skin burn. Similar findings have been reproduced experimentally [14], in mice [15], and in human subjects [7]. Therefore, thermal induction, previously proposed as a potential cause for the reported events, should be definitively ruled out. If the temperature increases occur on a nano-scale level within the pigment particles, this might still induce neural events, but involves severe measurement challenges.

Given the vital role of MRI in tracking our patient’s condition, the option of laser tattoo removal was considered. At present, there is a significant knowledge gap in the medical literature on the implications and risks related to MRI scans performed on individuals who have previously undergone tattoo laser removal. It is relevant to ask whether fragmenting the pigment particles in the skin would solve the problem, worsen it, or even create new problems in relation to MRI. If pigment density is a predisposing factor for these events, lasers fragmentation of the particles could theoretically decrease the problem by enhanced local washout of the pigment [16], but research is needed to support this notion. If a patient strongly desires a permanent solution to the problem, the tattoo can be surgically removed, either through excision or dermabrasion, considering the location and size [17].

If the skin reaction is solely driven by neural stimulation, applying topical analgesics (eg, lidocaine gel) prior to scanning could alleviate the painful sensations during MRI. As a prophylactic treatment, patients with MRI-reactive tattoos may consider applying analgesic creams under occlusion 30–60 min before scanning. However, if the sensations are generated from TRP activation, lidocaine would be less effective in providing pain relief. The effectiveness of analgesics has not yet been documented but should be considered for future patients.

To better understand MRI-induced reactions in decorative tattoos, it is relevant to study the conductivity of various tattoo pigments. These studies would elucidate an upper limit on how pigments in the skin interact with the radio frequency energies imposed during scanning. This knowledge could lead to production of more MRI-safe inks, reducing adverse reactions in tattooed patients. Additionally, future case investigation of MRI-related pain in tattoos should involve measuring TRP receptor expression and conducting immunoassay (eg, using ELISA) of skin biopsies to clarify the proposed neural etiology and release of cytokines.

Conclusions

In conclusion, based on the insight from this case report and the existing literature, we suggest that MRI can generally be considered safe for tattooed individuals and presence of tattoos do not contraindicate future scanning if needed. While transient reactions and discomfort may arise from neural stimulation, no permanent damage to tattoos or the surrounding skin emerges, in conformity with the literature. Recent findings have debunked the notion that thermal induction in the tattooed skin is the underlying cause of the problem. Uniquely, this case report provides the first evidence that reactions can diminish over time, suggesting that the symptomatic severity experienced is dependent on the age of the tattoo. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms behind these reactions and the consequence of removal, and to explore preventive measures.

Overall, the prognostic benefits of MRI outweigh the risks, and with proper monitoring and communication, patients with tattoos can undergo MRI scans confidently.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Helle Juhl Simonsen from the Department of Clinical Physiology, Nuclear Medicine & PET, Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, as well as to Pernille Nedergaard Engesgaard and Dennis Bakdal from the Department of Radiology, Bispebjerg University Hospital, Copenhagen, for their invaluable support in conducting the MRI scans.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Department and Institution Where Work Was Done

The work was done at the Department of Dermatology, Department of Radiology at Copenhagen University Hospital– Bispebjerg, and Department of Radiology Copenhagen University Hospital – Rigshospitalet Glostrup, Denmark.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Alsing KK, Johannesen HH, Hansen RH, Serup J. Tattoo complications and magnetic resonance imaging: A comprehensive review of the literature. Acta Radiol. 2020;61:1695–700. doi: 10.1177/0284185120910427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohner V, Enkirch SJ, Hattingen E, et al. Safety of tattoos, permanent makeup, and medical implants in population-based 3T magnetic resonance brain imaging: The Rhineland Study. Front Neurol. 2022;13:795573. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.795573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serup J, Alsing KK, Olsen O, et al. On the mechanism of painful burn sensation in tattoos on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Magnetic substances in tattoo inks used for permanent makeup (PMU) identified: Magnetite, goethite, and hematite. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(3):e13281. doi: 10.1111/srt.13281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krupa K, Bekiesińska-Figatowska M. Artifacts in magnetic resonance imaging. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:93–105. doi: 10.12659/PJR.892628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johannesen HH, Hansen RH, Alsing KK, Serup J. Tattoo Ink, Magnetism and sensation of burn during magnetic resonance imaging, and introduction of hand-held magnet testing of commercial tattoo ink stock products prior to use. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2022;56:251–58. doi: 10.1159/000521482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franiel T, Schmidt S, Klingebiel R. First-degree burns on MRI due to nonferrous tattoos. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:2006–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alsing KK, Olsen O, Koch CB, et al. MRI-induced neurosensory events in decorative black tattoos: Study by advanced experimental methods. Case Rep Dermatol. 2023;15:85–92. doi: 10.1159/000530220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang M, Yamamoto T. Progress in understanding radiofrequency heating and burn injuries for safer MR imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2023;22:7–25. doi: 10.2463/mrms.rev.2021-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foerster M, Dufour L, Bäumler W, et al. Development and validation of the epidemiological tattoo assessment tool to assess ink exposure and related factors in tattooed populations for medical research: Cross-sectional validation study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e42158. doi: 10.2196/42158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serup J. Chaotic tattoo ink market and no improved customer safety after new EU regulation. Dermatology. 2023;239(1):1–4. doi: 10.1159/000526338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehner K, Santarelli F, Penning R, et al. The decrease of pigment concentration in red tattooed skin years after tattooing. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1340–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misery L, Weisshaar E, Brenaut E, et al. Pathophysiology and management of sensitive skin: position paper from the special interest group on sensitive skin of the International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):222–29. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huet F, Misery L. Sensitive skin is a neuropathic disorder. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:1470–73. doi: 10.1111/exd.13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsing KK, Johannesen HH, Hansen RH, et al. MR scanning, tattoo inks, and risk of thermal burn: An experimental study of iron oxide and organic pigments: Effect on temperature and magnetic behavior referenced to chemical analysis. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:278–84. doi: 10.1111/srt.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomita S, Miyawaki T. Multifaceted evaluation of ultra-high-field 9.4-T magnetic resonance imaging after inorganic tattoos: An animal study. JMA J. 2019;2:155–63. doi: 10.31662/jmaj.2019-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi H, Togashi K. CT of tattoos removed with laser therapy. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1468–69. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sepehri M, Jørgensen B, Serup J. Introduction of dermatome shaving as first line treatment of chronic tattoo reactions. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):451–55. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.999021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]