Abstract

Purpose:

The intracranial benefit of offering dual immune-checkpoint inhibition (D-ICPI) with ipilimumab and nivolumab to patients with melanoma or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for brain metastases (BMs) is unknown. We hypothesized that D-ICPI improves local control compared with SRS alone.

Methods and Materials:

Patients with melanoma or NSCLC treated with SRS from 2014 to 2022 were evaluated. Patients were stratified by treatment with D-ICPI, single ICPI (S-ICPI), or SRS alone. Local recurrence, intracranial progression (IP), and overall survival were estimated using competing risk and Kaplan-Meier analyses. IP included both local and distant intracranial recurrence.

Results:

Two hundred eighty-eight patients (44% melanoma, 56% NSCLC) with 1,704 BMs were included. Fifty-three percent of patients had symptomatic BMs. The median follow-up was 58.8 months. Twelve-month local control rates with D-ICPI, S-ICPI, and SRS alone were 94.73% (95% CI, 91.11%–96.90%), 91.74% (95% CI, 89.30%–93.64%), and 88.26% (95% CI, 84.07%–91.41%). On Kaplan-Meier analysis, only D-ICPI was significantly associated with reduced local recurrence (P = .0032). On multivariate Cox regression, D-ICPI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.4003; 95% CI, 0.1781–0.8728; P = .0239) and planning target volume (HR, 1.022; 95% CI, 1.004–1.035; P = .0059) correlated with local control. One hundred seventy-three (60%) patients developed IP. The 12-month cumulative incidence of IP was 41.27% (95% CI, 30.27%–51.92%), 51.86% (95% CI, 42.78%–60.19%), and 57.15% (95% CI, 44.98%–67.59%) after D-ICPI, S-ICPI, and SRS alone. On competing risk analysis, only D-ICPI was significantly associated with reduced IP (P = .0408). On multivariate Cox regression, D-ICPI (HR, 0.595; 95% CI, 0.373–0.951; P = .0300) and presentation with >10 BMs (HR, 2.492; 95% CI, 1.668–3.725; P < .0001) remained significantly correlated with IP. The median overall survival after D-ICPI, S-ICPI, and SRS alone was 26.1 (95% CI, 15.5–40.7), 21.5 (16.5–29.6), and 17.5 (11.3–23.8) months. S-ICPI, fractionation, and histology were not associated with clinical outcomes. There was no difference in hospitalizations or neurologic adverse events between cohorts.

Conclusions:

The addition of D-ICPI for patients with melanoma and NSCLC undergoing SRS is associated with improved local and intracranial control. This appears to be an effective strategy, including for patients with symptomatic or multiple BMs.

Introduction

More than 200,000 patients receive brain metastasis diagnoses annually in the United States, and the incidence continues to rise because of improvements in survival with more effective systemic therapies.1 Historically, brain metastases were managed with radiation therapy alone, with local control rates >90%.2 Today, patients receiving radiation therapy are often treated concurrently with immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICPIs), particularly combination ipilimumab and nivolumab (dual ICPI), which is standard of care for advanced melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).3–5 However, the potential synergistic benefit of this combined modality approach is unclear as early immunotherapy trials excluded patients with brain metastases.

The role of dual ICPI for patients with advanced melanoma and NSCLC was established by the CheckMate-067, CheckMate-227, and CheckMate-9LA trials, which found improved overall survival with combination ipilimumab and nivolumab.3–5 These early trials excluded patients with untreated or symptomatic brain metastases because of their poor prognosis and concern for inadequate blood-brain barrier penetrance. Subsequent studies demonstrating intracranial activity with ipilimumab or pembrolizumab (single ICPI) were limited by low response rates (10%–30%).6,7 More recently, the ABC and CheckMate-204 trials reported improved intracranial responses (50%–60%) with dual ICPI in patients with asymptomatic melanoma with untreated brain metastases.8,9 Emerging data from the CheckMate-9LA trial also suggest intracranial efficacy with dual ICPI in patients with treated NSCLC brain metastases.10

The encouraging intracranial activity of dual ICPI may synergize with the immunomodulatory effects of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to improve intracranial outcomes.11 Preclinical models suggest that radiation therapy potentiates the effects of immunotherapy by enhancing antigen presentation and promoting recruitment of cytotoxic T cells, thereby augmenting antitumor immune responses.12–14 However, the potential benefit of combining dual ICPI with SRS is extrapolated from studies that predate the routine use of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab and report mixed results.15,16 Even so, dual ICPI is routinely offered in clinical practice to patients with brain metastases receiving SRS despite the lack of prospective data evaluating this approach.

We therefore aimed to report our institutional experience with patients with brain metastases in the era of dual ICPI. We hypothesized that the addition of combination ipilimumab and nivolumab to SRS significantly improves local control compared with SRS alone. Secondary endpoints included intracranial control, overall survival, toxicity, and assessment of outcomes with single ICPI.

Methods and Materials

This was an observational study and the Duke University Health System IRB Research Ethics Committee confirmed that no approval for the study of human subjects was required. The institutional review board of the Duke University Health System approved this study. Eligible patients were identified from an institutional SRS database and had pathologically confirmed metastatic NSCLC or melanoma treated with SRS for brain metastases between January 2014 and November 2022. All patients were 18 years of age or older and completed at least 1 brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after SRS. Patients without follow-up imaging or with diffuse leptomeningeal disease were excluded.

Baseline demographic variables, treatment histories, and outcomes were collected for patients and individual brain metastases. Collected information included gender, race, age at the time of SRS, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) at the time of SRS, tumor histology, tumor molecular features, programmed cell death ligand 1 expression patterns, extracranial disease control, prior systemic therapies, immunotherapy regimens, radiation therapy details (eg, technique, dose, fractions), salvage therapies, radiographic findings on surveillance MRI scans, dates of local and distant intracranial progression, and dates of death or last follow-up. Outcomes for individual brain metastases were tracked over time until last follow-up or death. Patients with neurologic deficits attributed to their brain metastases were considered symptomatic. Patients with evidence of extracranial progression on radiographic imaging within 60 days of SRS were defined as having progressive extracranial disease. Adverse effects attributed by the prescribing medical oncologist to immunotherapy were defined as immunotherapy-related adverse events and were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. Adverse neurologic events were defined as new or progressing neurologic deficits after SRS requiring medical intervention. Hospitalizations for any cause potentially related to intracranial disease were also recorded for each patient. Adverse events were recorded until last known follow-up.

Radiation technique

Simulation and treatment planning

All patients underwent a computed tomography (CT) simulation with a frameless SRS thermoplastic mask (BrainLAB). A thin-cut (1-mm) CT scan of the brain was fused with a thin-cut, gadolinium contrast−enhanced, axial, 3-dimensional spoiled-gradient, T1-weighted MRI image obtained using a 1.5T or 3T MRI scanner (General Electric). Patients were contoured using either the BrainLAB iPlan RT Image software (BrainLAB) or the Eclipse treatment planning software (Varian Medical Systems). Gross tumor volume was defined as the contrast-enhancing tumor on MRI T1 sequences. A planning target volume (PTV) was created by adding a 1-mm margin to the gross tumor volume. Either dynamic conformal arcs or volumetric arc therapy treatment plans were then prepared with the Varian Eclipse (Varian Medical Systems) treatment planning system, using beam geometry and optimization criteria as previously described.17,18 For patients with multiple brain metastases, a single isocenter multitarget technique was used.19 Dose was normalized so that the 100% isodose line encompassed >99% of the target volume with a maximum dose ranging between 110% and 125%.20

SRS dose and treatment delivery

Incorporating lesion size, lesion location, and the number of brain metastases, SRS dose was prescribed in a single fraction or multiple fractions by the treating radiation oncologist. Single-fraction dose prescriptions followed the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 90–05 guidelines in which target lesions measuring 0 to 2 cm in maximal diameter generally received 18 to 24 Gy in 1 fraction. Hypofractionated regimens were typically 25 to 27.5 Gy in 5 fractions and were reserved for target lesions measuring greater than 2 cm. Doses were decreased at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist according to V12Gy for the brain, doses to organs at risk from prior treatment, and tumor location. Postoperative tumor beds were included and were typically treated with multiple fractions. The number of fractions and brain location were recorded. Treatment was delivered on a TrueBeam STx linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems) using orthogonal kV imaging and cone beam CT with 6-degrees-of-freedom position adjustment before treatment.20 Prophylactic steroids were administered during and after SRS, with doses and steroid tapers determined by the treating radiation oncologist.

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy was classified as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy. The specific agents received, number of lines of systemic therapy before SRS, and their timing relative to radiation therapy were recorded. Timing of SRS relative to immunotherapy was at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Concurrent immunotherapy and SRS was defined as ICPI delivered within 4 weeks either before or after SRS, as previously described in the literature.21 Timing that did not meet this definition was considered sequential therapy. Patients were categorized as receiving SRS alone if they never received any immunotherapy. All patients in the dual ICPI cohort received combination ipilimumab and nivolumab. Patients who did not receive any immunotherapy were eligible for targeted therapy and chemotherapy at the discretion of the treating medical oncologist.

Follow-up

Patients were followed with clinical evaluation and MRI scans every 3 months after SRS, unless otherwise indicated. Reasons for discontinuation of surveillance imaging included patient preference, enrollment in hospice, or death. Outcomes for individual brain metastases were tracked on serial MRI images over the entire course of a patient’s history. Local recurrence was defined as progression at the site of a previously treated metastasis and was recorded for each brain metastasis. Per institutional guidelines, all lesions suspicious for local recurrence were reviewed at the multidisciplinary Duke University Health System Brain and Spine Metastasis Tumor Board, which consists of radiation oncologists, neurosurgeons, medical oncologists, and neuroradiologists. Pathologic confirmation of viable malignant cells was mandatory before salvage radiation therapy for suspected local recurrence after SRS. In the absence of pathologic confirmation, local recurrence was determined by consensus opinion at the multidisciplinary Duke University Health System Brain and Spine Metastasis Tumor Board, which incorporated clinical data, radiographic changes per Response assessment in neuro-oncology criteria Brain Metastasis criteria, and temporal responses to steroids and systemic therapy. Intracranial progression was defined as the composite of local recurrence and distant brain recurrence at sites not previously treated with radiation therapy. The incidence of intracranial progression was documented for each patient. Death due to any cause was also recorded for each patient.

Statistics

The primary endpoint was local control, which was defined for individual brain metastases as the interval between the completion of SRS and the date of biopsy-confirmed local recurrence for each treated metastasis. Brain metastases were censored at the time of last available imaging. Secondary outcomes included intracranial control and overall survival, which were defined as patient level outcomes. Intracranial control was defined as the interval between completion of SRS and the date of first local or distant intracranial progression. Overall survival was the interval between SRS completion and the date of death of any cause. Local control and overall survival were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with censoring at the time of death or last known follow-up. Time-to-event analyses for intracranial control were performed with death incorporated as a competing risk. The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between cohorts.

Patient demographics were reported using descriptive statistics as absolute and relative frequencies. Cox univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to assess the association of patient and treatment variables on clinical endpoints. The Wald test was used to assess the role of covariates in the model. The estimated hazards were reported and any predictors with a P value ≤.05 were included in the multivariate analysis. A 2-sided P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using the SAS statistical software package (version 9.4, SAS Institute).

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

A total of 288 patients with 1,704 brain metastases from melanoma and NSCLC were included in the analysis (Table 1). One hundred twenty-eight (44%) and 160 (56%) patients had melanoma and NSCLC primaries, respectively. One hundred fifty-three (53%) patients had symptomatic intracranial disease. Tumor molecular features are detailed in Table E1. Seventy-two (25%) patients were >70 years old and 246 (85%) patients had a KPS >70. Eighty-two (28%), 129 (45%), and 77 (27%) patients were treated with dual, single, and no ICPI. Among patients who did not receive immunotherapy, 21% and 39% received a targeted agent or chemotherapy, respectively. The most common targeted agents were epidermal growth factor receptor (69%), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1/mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (19%), and ALK (13%) inhibitors. Two hundred eleven (73%) patients received immunotherapy, among whom 137 (65%) and 74 (35%) patients received immunotherapy concurrently and sequentially with SRS, respectively. Immunotherapy agents are listed in Table E2. The majority of patients receiving dual (74%) and single (59%) ICPI were treated concurrently with SRS. Patients in the dual ICPI cohort presented with a comparable number of brain metastases relative to patients in the single ICPI (P = .2390) and SRS alone (P = .2210) cohorts. The number of patients with >10 brain metastases at presentation was also similar across the dual (21%), single (17%), and no ICPI (16%) groups. Lesion features and treatment characteristics are reported in Table E3. The median follow-up was 58.8 months (Q1-Q3: 50.6–62.8), and 93 patients (32%) were alive at study closure.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic Variables (n, %) | All patients N = 288 (100%) | SRS + D-ICPI n = 82 (28%) | SRS + S-ICPI n = 129 (45%) | SRS alone n = 77 (27%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age (y) | .298 | ||||

| ≤70 | 216 (75) | 65 (79) | 98 (76) | 53 (69) | |

| >70 | 72 (25) | 17 (21) | 31 (24) | 24 (31) | |

| Race | .016* | ||||

| Caucasian | 252 (88) | 75 (92) | 104 (81) | 73 (95) | |

| African American | 30 (10) | 4 (5) | 22 (17) | 4(5) | |

| Asian | 5 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Karnofsky performance status | .331 | ||||

| ≤70 | 41 (14) | 7 (8) | 20 (16) | 14 (18) | |

| >70 | 246 (85) | 75 (92) | 108 (84) | 63 (82) | |

| Histology | <.001* | ||||

| NSCLC | 160 (56) | 15 (18) | 82 (64) | 63 (82) | |

| Melanoma | 128 (44) | 67 (82) | 47 (36) | 14 (18) | |

| Extracranial disease | .438 | ||||

| Stable | 113 (39) | 29 (35) | 47 (36) | 37 (48) | |

| Decreasing | 8 (3) | 3 (4) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Progressing | 153(53) | 46 (56) | 71 (55) | 36 (47) | |

| Unknown | 14 (5) | 4 (5) | 6 (5) | 4 (5) | |

| Immunotherapy timing | <.001* | ||||

| Concurrent | 137 (65) | 61 (74) | 76 (59) | - | |

| Sequential | 74 (35) | 21 (26) | 53 (41) | - | |

| Prior whole-brain radiation therapy | .467 | ||||

| Yes | 15 (5) | 4 (5) | 5 (4) | 6 (8) | |

| Neurologic symptoms at presentation | .036* | ||||

| Yes | 153 (53) | 47 (57) | 58 (45) | 48 (62) | |

| Number of prior lines of nonimmunotherapy | .003* | ||||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Radiation fractionation | .229 | ||||

| Single-fraction SRS | 147 (51) | 39 (48) | 73 (57) | 35 (46) | |

| Multifraction SRS | 141 (49) | 43 (52) | 56 (43) | 42 (55) | |

| Death | |||||

| Yes | 195 (68) | 41 (50) | 96 (74) | 58 (75) | <.001* |

Abbreviations: D-ICPI = dual immune-checkpoint inhibition; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; S-ICPI = single immune-checkpoint inhibition; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery.

Statistically significant.

Local control

A total of 127 (7%) brain metastases across 50 (17%) patients developed local recurrence after SRS, with 31 (62%) patients undergoing biopsy confirmation. Twelve-month local control for individual brain metastases was 94.73% (95% CI, 91.11%–96.90%), 91.74% (95% CI, 89.30%–93.64%), and 88.26% (95% CI, 84.07%–91.41%) after dual, single, and no ICPI (Fig. 1). The median time to local recurrence was not reached for any cohort. By Kaplan-Meier analysis, dual ICPI was associated with a significant reduction in local recurrence compared with SRS alone (P = .0032), whereas single ICPI was not associated with an improvement in outcomes (P = .0785). Neither concurrent nor sequential delivery of immunotherapy with SRS was associated with local control (P = .2705; Fig. E1), even after stratification by dual or single ICPI. On subgroup analysis of metastases treated sequentially, there was no difference in local control when immunotherapy was delivered in the neoadjuvant versus adjuvant setting (P = .4424; Fig. E2).

Fig. 1.

Local recurrence for individual brain metastases, stratified by immune-checkpoint inhibition status.

On univariate Cox regression analysis, dual ICPI (hazard ratio [HR], 0.4681; 95% CI, 0.2731–0.7764; P = .0042) was associated with improved local control, and a larger PTV for each metastasis (HR, 1.017; 95% CI, 1.002–1.029; P = .0088) and melanoma histology (HR, 1.749; 95% CI, 1.230–2.499; P = .0019) correlated with increased risk for local recurrence (Table 2). On multivariate Cox regression analysis, dual ICPI remained significantly associated with improved local control (HR, 0.4003; 95% CI, 0.1781–0.8728; P = .0239), and a larger PTV was predictive of worse outcomes (HR, 1.022; 95% CI, 1.004–1.035; P = .0059).

Table 2.

Local control

| Variable | Univariate Cox regression |

Multivariate Cox regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| All brain metastases (N = 1704) | ||||

| Brain metastasis type | ||||

| Unresected metastasis | .7768 | 1.11 (0.58–2.47) | ||

| Resection cavity | Ref | |||

| Fractionation | ||||

| Single-fraction SRS | .1923 | 1.29 (0.89–1.90) | ||

| Multifraction SRS | Ref | |||

| BED10 | .2904 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | ||

| ICPI therapy | ||||

| D-ICPI | .0042* | 0.47 (0.27–0.77) | .0239* | 0.40 (0.18–0.87) |

| S-ICPI | .1094 | 0.73 (0.50–1.08) | .7158 | 1.12 (0.61–2.10) |

| No ICPI | Ref | |||

| Planning target volume (cm3) | .0088* | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | .0059* | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) |

| Histology | ||||

| Melanoma | .0019* | 1.75 (1.23–2.50) | .3579 | 1.45 (0.65–3.15) |

| NSCLC | Ref | |||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Infratentorial | .2405 | 0.72 (0.41–1.20) | ||

| Supratentorial | Ref | |||

| Prior nonimmune systemic therapy | ||||

| >2 Prior systemic therapies | .5625 | 0.77 (0.27–1.69) | ||

| ≤2 Prior systemic therapies | Ref | |||

| ICPI and SRS subgroup (n = 1258) | ||||

| ICPI timing | ||||

| Concurrent ICPI | .0979 | 0.69 (0.44–1.07) | ||

| Sequential ICPI | Ref | |||

Abbreviations: BED = biologically effective dose; D-ICPI = dual ICPI; HR = hazard ratio; ICPI = immune-checkpoint inhibition; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; Ref = reference; S-ICPI = single ICPI; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery.

Statistically significant.

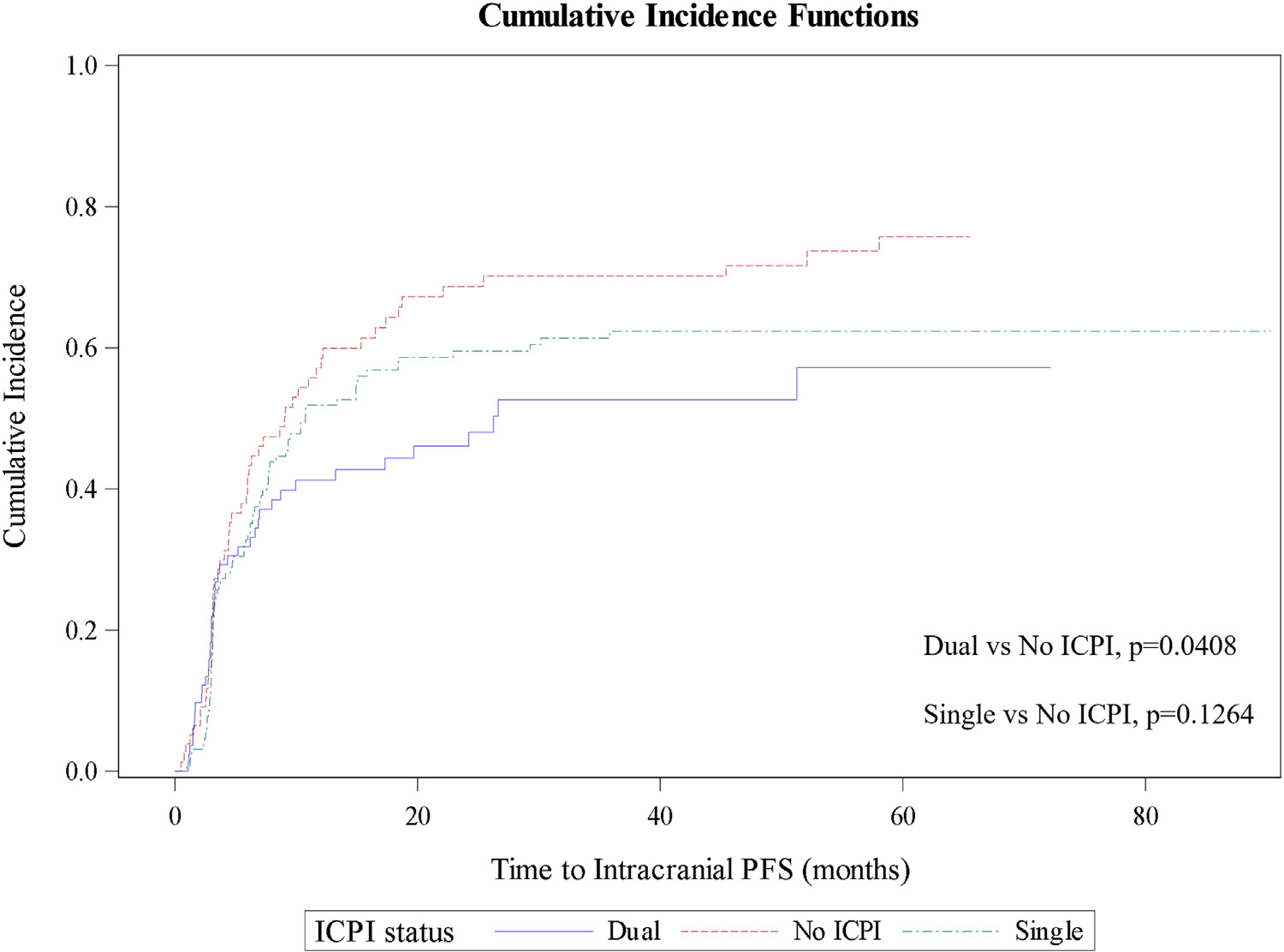

Intracranial control

One hundred seventy-three (60%) patients experienced intracranial progression. This included 40 (49%), 78 (60%), and 55 (71%) patients treated with dual, single, and no ICPI, respectively. On competing risk analysis, the 12-month cumulative incidence of intracranial progression was 41.27% (95% CI, 30.27%–51.92%), 51.86% (95% CI, 42.78%–60.19%), and 57.15% (95% CI, 44.98%–67.59%) with dual ICPI, single ICPI, and SRS alone (Fig. 2). Dual ICPI was associated with a significant reduction in intracranial recurrence compared with SRS alone (P = .0408), and the difference in outcomes between single ICPI and SRS alone did not reach statistical significance (P = .1264). On competing risk analysis, there was no association between either concurrent or sequential timing of immunotherapy and intracranial recurrence (P = .1391), even after stratifying by immunotherapy cohort (Fig. E3). On subgroup analysis of patients treated sequentially, adjuvant immunotherapy was associated with improved intracranial control compared with neoadjuvant immunotherapy (P = .049; Fig. E4).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of intracranial progression, stratified by immune-checkpoint inhibition status.

On univariate Cox regression analysis, dual ICPI (HR, 0.626; 95% CI, 0.416–0.944; P = .0253) and immunotherapy-related adverse events (HR, 0.693; 95% CI, 0.499–0.962; P = .0284) were associated with improved intracranial control (Table 3). Presentation with >10 brain metastases (HR, 2.493; 95% CI, 1.752–3.548; P < .0001) and a history of >2 prior lines of chemotherapy or targeted therapy (HR, 1.561; 95% CI, 1.170–2.082; P = .0025) were associated with elevated risk of progression. On multivariate Cox regression analysis, only dual ICPI (HR, 0.595; 95% CI, 0.373–0.951; P = .0300) and presentation with >10 brain metastases (HR, 2.492; 95% CI, 1.668–3.725; P < .0001) remained correlated with intracranial control.

Table 3.

Intracranial control

| Variable | Univariate Cox regression |

Multivariate Cox regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| All patients (N = 288) | ||||

| Age ≤70 y | .8825 | 1.03 (0.72–1.46) | ||

| KPS ≤70 | .7333 | 0.92 (0.56–1.50) | ||

| Neurologic symptoms at presentation | .1698 | 0.81 (0.61–1.09) | ||

| Fractionation | ||||

| Single-fraction SRS | .2761 | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | ||

| Multifraction SRS | Ref | |||

| BED10 | .5779 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | ||

| ICPI therapy | ||||

| D-ICPI | .0253* | 0.63 (0.42–0.94) | .0300* | 0.60 (0.37–0.95) |

| S-ICPI | .1623 | 0.79 (0.57–1.10) | .1206 | 0.75 (0.53–1.08) |

| No ICPI | Ref | |||

| SRS for >10 brain metastases | <.0001* | 2.49 (1.75–3.55) | <.0001* | 2.49 (1.67–3.73) |

| Total PTV (cm3) | .6043 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Melanoma | .5966 | 1.09 (0.80–1.47) | ||

| NSCLC | Ref | |||

| Prior nonimmune systemic therapy | ||||

| >2 Prior systemic therapies | .0025* | 1.56 (1.17–2.08) | .2510 | 1.23 (0.86–1.77) |

| ≤2 Prior systemic therapies | Ref | |||

| ICPI and SRS subgroup (n = 211) | ||||

| ICPI timing | ||||

| Concurrent ICPI | .4029 | 1.18 (0.81–1.72) | ||

| Sequential ICPI | Ref | |||

| irAEs (yes vs no) | .0284* | 0.69 (0.50–0.96) | .2182 | 0.79 (0.55–1.15) |

Abbreviations: BED = biologically effective dose; D-ICPI = dual ICPI; HR = hazard ratio; ICPI = immune-checkpoint inhibition; irAE = immune-related adverse events; KPS = Karnofsky performance status; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; PTV = planning target volume; Ref = reference; S-ICPI = single ICPI; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery.

Statistically significant.

Overall survival

Median overall survival was 26.1 (95% CI, 15.5–40.7), 21.5 (95% CI, 16.5–29.6), and 17.5 (95% CI, 11.3–23.8) months after dual, single, and no ICPI. By Kaplan-Meier estimate, the association between dual ICPI and survival did not reach statistical significance (P = .0772; Fig. E5). Timing of therapy was also not predictive of survival (P = .373), with a median survival of 24.5 (95% CI, 18.4–32.4) and 21.7 (95% CI, 11.1–32.7) months with concurrent and sequential therapy, respectively.

On univariate Cox regression analysis, KPS ≤70 (HR, 1.778; 95% CI, 1.174–2.691; P = .0065), presentation with >10 brain metastases (HR, 1.679; 95% CI, 1.252–2.252; P = .0005), and >2 prior lines of chemotherapy or targeted therapy (HR, 1.324;, 95% CI, 1.002–1.748; P = .0484) correlated with worse overall survival. By contrast, patients who experienced immunotherapy-related adverse events (HR, 0.646; 95% CI, 0.473–0.883; P = .0061) or with stable extracranial disease (HR, 0.487; 95% CI, 0.359–0.660; P < .0001) had improved survival (Table 4). On multivariate Cox regression analysis, KPS (HR, 1.723; 95% CI, 1.098–2.704; P = .0179), stable extracranial disease (HR, 0.485; 95% CI, 0.354–0.665; P < .0001), presentation with >10 brain metastases (HR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.242–2.522; P = .0016), and immunotherapy-related adverse events (HR, 0.607; 95% CI, 0.436–0.846; P = .0032) remained correlated with overall survival.

Table 4.

Overall survival

| Univariate Cox regression |

Multivariate Cox regression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) |

|

| ||||

| All patients (N = 288) | ||||

| Age ≤ 70 y | .4742 | 0.89 (0.64–1.23) | ||

| KPS ≤70 | .0065* | 1.78 (1.17–2.69) | .0179* | 1.72 (1.10–2.70) |

| Extracranial status | ||||

| Stable vs progressing | <.0001* | 0.49 (0.36–0.66) | <.0001* | 0.49 (0.35–0.67) |

| Decreasing vs progressing | .7455 | 0.91 (0.52–1.59) | .5819 | 1.17 (0.67–2.05) |

| Fractionation | ||||

| Single-fraction SRS | .8484 | 0.97 (0.73–1.29) | ||

| Multifraction SRS | Ref | |||

| ICPI therapy | ||||

| D-ICPI | .0855 | 0.70 (0.47–1.05) | ||

| S-ICPI | .4440 | 0.88 (0.64–1.22) | ||

| No ICPI | Ref | |||

| SRS for >10 brain metastases | .0005* | 1.68 (1.25–2.25) | .0016* | 1.77 (1.24–2.52) |

| Total PTV (cm3) | .9845 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Melanoma | .4847 | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | ||

| NSCLC | Ref | |||

| Prior nonimmune systemic therapy | ||||

| >2 Prior systemic therapies | .0484* | 1.32 (1.00–1.75) | .5255 | 1.11 (0.81–1.53) |

| ≤2 Prior systemic therapies | Ref | |||

| ICPI and SRS subgroup (n = 211) | ||||

| ICPI timing | ||||

| Concurrent ICPI | .3777 | 0.86 (0.61–1.21) | ||

| Sequential ICPI | Ref | |||

| irAEs (yes vs no) | .0061* | 0.65 (0.47–0.88) | .0032* | 0.61 (0.44–0.85) |

Abbreviations: D-ICPI = dual ICPI; HR = hazard ratio; ICPI = immune-checkpoint inhibition; irAE = immune-related adverse events; KPS = Karnofsky performance status; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; PTV = planning target volume; Ref = reference; S-ICPI = single ICPI; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery.

Toxicity

Immunotherapy-related adverse events occurred in 96 (45%) patients and are reported in Table E4. The most common adverse effects of immunotherapy were colitis (22%), hypothyroidism (18%), and hepatitis (14%). Sixty-five percent of events were grade 1 to 2 and 34% were grade 3 to 4. There was 1 grade 5 event attributed to immunotherapy-related fulminant hepatitis. There was no difference in the incidence of neurologic adverse events in patients receiving dual ICPI (33%) compared with single ICPI (36%; P = .6226) or SRS alone (37%; P = .5654). There was also no difference in the incidence of hospitalization among patients receiving dual ICPI (49%) compared with single ICPI (47%; P = .7184) or SRS alone (44%; P = .5046).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate long-term outcomes after dual ICPI in patients with brain metastases undergoing SRS. In a large cohort of 1704 brain metastases from 288 patients with NSCLC or melanoma with a median follow-up of nearly 5 years, treatment with dual ICPI was associated with a significant improvement in local control and overall intracranial control. Concurrent immunotherapy and single ICPI were not correlated with improved clinical outcomes. Dual ICPI was well tolerated with no difference in hospitalization or neurologic adverse events compared with single ICPI or SRS alone.

The intracranial efficacy of dual ICPI in combination with SRS has yet to be reported in the literature. The role of dual ICPI in patients with advanced melanoma and NSCLC was established by the CheckMate-067, CheckMate-227, and CheckMate-9LA trials, which observed improved overall survival with combination ipilimumab and nivolumab. However, CheckMate-067 excluded patients with melanoma with active brain metastases.3 Likewise, CheckMate-227 and CheckMate-9LA did not include intracranial outcomes as primary endpoints because patients with asymptomatic brain metastases were required to complete local therapy before study enrollment.4,5 Despite the lack of prospective data on intracranial efficacy with this combinatorial approach, dual ICPI is increasingly offered in conjunction with SRS in clinical practice.

The intracranial activity of dual ICPI is informed by the single-arm phase 2 CheckMate-204 trial, which evaluated outcomes with dual ICPI alone in patients with melanoma with asymptomatic (cohort A, n = 101) or symptomatic (cohort B, n = 18) untreated brain metastases.9 Asymptomatic patients had a 54% objective intracranial response rate and durable intracranial progression-free survival. Only 9% of patients in cohort A received prior SRS and 77% had fewer than 3 brain metastases. By contrast, symptomatic patients had poor responses to immunotherapy alone. These results are consistent with the phase 2 ABC trial, which randomized 79 patients with asymptomatic melanoma with untreated brain metastases to dual ICPI alone or single ICPI alone.8 Five-year intracranial progression-free survival was 46% and 15% with ipilimumab plus nivolumab versus nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks). In a recent post hoc analysis of patients in the CheckMate-9LA trial, intracranial outcomes from 101 (14%) patients with NSCLC with pre-treated, asymptomatic baseline brain metastases suggested improved intracranial efficacy with dual ICPI plus chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone.10 Intracranial progression-free survival favored addition of dual ICPI (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.26–0.68), with improved intracranial objective response rates (39% vs 20%) and time to development of new brain metastases (10.9 vs 4.6 months). Eighty-eight percent of patients had a history of prior radiation therapy, 37% to 40% of whom received whole-brain radiation therapy across both study arms. Although these studies support the intracranial efficacy of dual ICPI, it remains unclear whether combination with SRS could improve these response rates, particularly for symptomatic patients.

Preclinical evidence suggests that immunotherapy may potentiate the effects of SRS. SRS acts as a primer, upregulating major histocompatibility complex I expression on tumor cells, T-cell infiltration, and immunologic death.22–25 This may be mediated by activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in the setting of radiation-induced double-strand DNA breaks, resulting in type I interferon production and subsequent innate and adaptive immune responses.26 SRS may also enhance antigen presentation via epitope spreading, thus facilitating recruitment of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and recognition of tumor cells.12–14 By preventing downregulation of T-cell activation at the tumor-lymphocyte interface, ICPIs may potentiate antitumor responses and durability of tumor control after SRS.

Data on intracranial outcomes after combined immune-checkpoint blockade and SRS are limited to small retrospective series, which report mixed results and predate the routine use of dual ICPI. Chen et al27 reported outcomes from 260 patients with brain metastases, of whom 79 received immunotherapy and SRS. Immunotherapy did not correlate with improved local control, but overall survival was improved when immunotherapy was delivered within 2 weeks of SRS compared with SRS alone. In a cohort of 144 patients, Le et al28 reported improved distant intracranial control when SRS was delivered within 30 days of immunotherapy compared with nonconcurrent therapy and SRS alone, though local control was comparable. Although smaller single institution series also suggest improvements in distant intracranial control29–31 and local control,29,32,33 others report comparable outcomes with the addition of single ICPI compared with SRS alone.15,16,34–36

In this large series, we report significantly improved local control and intracranial control with the addition of dual ICPI in patients receiving SRS. These findings agree with the ABC and CheckMate-204 trials, which reported improved intracranial activity with dual ICPI alone compared with single ICPI alone. Likewise, Acharya et al29 reported improved 6-month distant intracranial control with dual ICPI in a small subgroup analysis of 14 patients. Importantly, our findings were independent of fractionation, tumor histology, or whether immunotherapy was delivered concurrently or sequentially with SRS. Additionally, 57% of dual ICPI patients had symptomatic intracranial disease. Even so, our findings compare favorably to results from CheckMate-204, which observed only a 17% response rate to dual ICPI among symptomatic patients.9 These results suggest that combining dual ICPI with SRS may improve outcomes for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with brain metastases.

Several other factors emerged as independent predictors for clinical outcomes. Consistent with other investigations, larger PTVs predicted worse local control.37–39 Patients with >10 brain metastases also had significantly worse intracranial control, likely because of more aggressive underlying tumor biology. This finding supports the 2022 American Society for Radiation Oncology Clinical Guidelines, which distinguish patients with greater than 10 brain metastases because of their increased risk of intracranial progression.40 Additionally, immunotherapy-related adverse events were correlated with improved outcomes even after controlling for performance status, extracranial disease control, and the number of brain metastases. Development of treatment-related adverse effects could be a surrogate for more robust immune responses and immune-checkpoint efficacy, as previously reported in the literature.41

Finally, timing of immunotherapy was not predictive of response to treatment, with comparable outcomes after concurrent or sequential therapy. This concurs with Lehrer et al,42 who evaluated a cohort of 203 patients treated with immune-checkpoint blockade and SRS and reported comparable 1-year local control regardless of whether immunotherapy was delivered within 4 weeks of single-fraction SRS (81.9% and 74.6%; P = .36). However, our subgroup analysis of patients treated sequentially with immunotherapy identified improved intracranial control with adjuvant relative to neoadjuvant immunotherapy. The benefit of adjuvant immunotherapy for extracranial melanoma and NSCLC was demonstrated by the phase 3 European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 1325 and PACIFIC trials.43,44 In patients with brain metastases, SRS-induced epitope spreading may prime immune responses against tumor-associated antigens and enhance the efficacy of adjuvant immunotherapy. Adequately powered prospective trials are necessary to clarify the appropriate sequencing of these therapies for patients with brain mestastases.15,16,27–33

Interpretation of these results is limited by the non-randomized, retrospective nature of this study and the potential for unobserved covariates contributing to differences in local and intracranial control despite efforts to account for imbalances between cohorts. Importantly, the inclusion of patients with melanoma and NSCLC brain metastases may obfuscate histology-specific clinical responses to immunotherapy. Nonetheless, in a subgroup analysis of our study, dual ICPI remained associated with improved intracranial progression free survival for patients with either melanoma (P = .038) or NSCLC (P = .058) compared with SRS alone. Although our findings support results from the CheckMate-204 and CheckMate-9LA trials, future investigations should consider evaluating SRS with dual ICPI exclusively in patients with NSCLC or melanoma.

Conclusion

In summary, this is the largest single-institution series to report outcomes with SRS and immunotherapy and the first to evaluate long-term outcomes with dual ICPI. These findings represent a significant contribution to the field that could inform clinical practice. Dual ICPI plus SRS appears to be an effective treatment option for patients with NSCLC and melanoma brain metastases, including those with symptomatic disease and larger intracranial disease burden. The clinical benefit of this approach is independent of fractionation, tumor histology, and whether immunotherapy is delivered concurrently or sequentially with SRS, suggesting that this strategy has implications for a large proportion of patients with brain metastases. Results from ongoing trials evaluating outcomes with dual ICPI and SRS will be informative.45–47 Future prospective trials should incorporate additional toxicity endpoints and patient-reported outcomes as the appropriate sequencing of therapies is refined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors report the following funding information: National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (5R38-CA245204 to E.J.V.) and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (K08-CA2560450 to Z.J.R.). The funders had no role in the writing of the article or the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Z.J.R. receives royalties for intellectual property managed by Duke Office of Licensing and Ventures that has been licensed to Genetron Health and honoraria for lectures to Eisai Pharmaceuticals and Oakstone Publishing Group. A.K.S.S. receives research funding (paid to institution) from Ascentage, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ideaya, Immunocore, Merck, Olatec Therapeutics, Regeneron, Replimune, and Seagen. A.K.S.S. has a consultant or advisory role with Bristol Myers Squibb, Iovance, Regeneron, Novartis, and Pfizer. J.D. is a consultant for Amgen, Ono Therapeutics, and Novartis and has received royalties from Wolters Kluwer.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.12.002.

Data Sharing Statement:

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Cagney DN, Martin AM, Catalano PJ, et al. Incidence and prognosis of patients with brain metastases at diagnosis of systemic malignancy: A population-based study. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:1511–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Ludmir EB, Wang Y, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiation therapy for patients with 4–15 brain metastases: A phase III randomized controlled trial. Int J Radiat Oncol 2020;108:S21–S22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1345–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non−small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2020–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu T-E, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: Early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:976–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margolin K, Ernstoff MS, Hamid O, et al. Ipilimumab in patients with melanoma and brain metastases: An open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long GV, Atkinson VG, Lo S, et al. Long-term outcomes from the randomized phase II study of nivolumab (nivo) or nivo+ipilimumab (ipi) in patients (pts) with melanoma brain metastases (mets): Anti-PD1 brain collaboration (ABC). Ann Oncol 2019;30:v534. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Hodi FS, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with active melanoma brain metastases treated with combination nivolumab plus ipilimumab (CheckMate 204): Final results of an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1692–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz-Ares LG, Ciuleanu T-E, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for metastatic NSCLC in CheckMate 9LA: 3-year clinical update and outcomes in patients with brain metastases or select somatic mutations. J Thorac Oncol 2023;18:204–222. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amaral T, Kiecker F, Schaefer S, et al. Combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab with and without local therapy in patients with melanoma brain metastasis: A DeCOG* study in 380 patients. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharabi AB, Lim M, DeWeese TL, Drake CG. Radiation and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy: Radiosensitisation and potential mechanisms of synergy. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e498–e509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demaria S, Golden EB, Formenti SC. Role of local radiation therapy in cancer immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escorcia FE, Postow MA, Barker CA. Radiotherapy and immune checkpoint blockade for melanoma. Cancer J 2017;23:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohm AE, Tang JD, Mills MN, et al. Clinical outcomes of non−small cell lung cancer brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery and immune checkpoint inhibitors, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors, or chemotherapy alone. J Neurosurg 2022;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman R, Cortes A, Niemierko A, et al. The impact of timing of immunotherapy with cranial irradiation in melanoma patients with brain metastases: Intracranial progression, survival and toxicity. J Neurooncol 2018;138:299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison J, Hood R, Yin F-F, Salama JK, Kirkpatrick J, Adamson J. Is a single isocenter sufficient for volumetric modulated arc therapy radiosurgery when multiple intracranial metastases are spatially dispersed? Med Dosim 2016;41:285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanhope C, Chang Z, Wang Z, et al. Physics considerations for single-isocenter, volumetric modulated arc radiosurgery for treatment of multiple intracranial targets. Pract Radiat Oncol 2016;6:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim GJ, Buckley ED, Herndon JE, et al. Outcomes in patients with 4 to 10 brain metastases treated with dose-adapted single-isocenter multi-target stereotactic radiosurgery: A prospective study. Adv Radiat Oncol 2021;6:100760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limon D, McSherry F, Herndon J, et al. Single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases. Adv Radiat Oncol 2017;2:555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehrer EJ, Kowalchuk RO, Gurewitz J, et al. Concurrent administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors and single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma brain metastases is not associated with an increased risk of radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol 2023;116:858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, et al. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J Exp Med 2011;208:1989–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiotto M, Fu Y-X, Weichselbaum RR. The intersection of radiotherapy and immunotherapy: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Sci Immunol 2016;1:EAAG1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weichselbaum RR, Liang H, Deng L, Fu Y-X. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A beneficial liaison? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manda K, Glasow A, Paape D, Hildebrandt G. Effects of ionizing radiation on the immune system with special emphasis on the interaction of dendritic and T cells. Front Oncol 2012;2:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaios EJ, Winter SF, Shih HA, et al. Novel mechanisms and future opportunities for the management of radiation necrosis in patients treated for brain metastases in the era of immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Douglass J, Kleinberg L, et al. Concurrent immune checkpoint inhibitors and stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases in non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol 2018;100:916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le A, Mohammadi H, Mohammed T, et al. Local and distant brain control in melanoma and NSCLC brain metastases with concurrent radiosurgery and immune checkpoint inhibition. J Neurooncol 2022;158:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acharya S, Mahmood M, Mullen D, et al. Distant intracranial failure in melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery in the era of immunotherapy and targeted agents. Adv Radiat Oncol 2017;2:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanker MD, Garimall S, Gatt N, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases: Concurrent immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy associated with superior clinicoradiological response outcomes. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2022;66:536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusuf MB, Amsbaugh MJ, Burton E, Chesney J, Woo S. Peri-SRS administration of immune checkpoint therapy for melanoma metastatic to the brain: Investigating efficacy and the effects of relative treatment timing on lesion response. World Neurosurg 2017;100:632–640. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Inbar O, Shih H-H, Xu Z, Schlesinger D, Sheehan JP. The effect of timing of stereotactic radiosurgery treatment of melanoma brain metastases treated with ipilimumab. J Neurosurg 2017;127:1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdulhaleem M, Johnston H, D’Agostino R, et al. Local control outcomes for combination of stereotactic radiosurgery and immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer brain metastases. J Neurooncol 2022;157:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colaco RJ, Martin P, Kluger HM, Yu JB, Chiang VL. Does immunotherapy increase the rate of radiation necrosis after radiosurgical treatment of brain metastases? J Neurosurg 2016;125:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel KR, Shoukat S, Oliver DE, et al. Ipilimumab and stereotactic radiosurgery versus stereotactic radiosurgery alone for newly diagnosed melanoma brain metastases. Am J Clin Oncol 2017;40:444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathew M, Tam M, Ott PA, et al. Ipilimumab in melanoma with limited brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Melanoma Res 2013;23:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang EL, Hassenbusch SJ, Shiu AS, et al. The role of tumor size in the radiosurgical management of patients with ambiguous brain metastases. Neurosurgery 2003;53:272–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogelbaum MA, Angelov L, Lee S-Y, Li L, Barnett GH, Suh JH. Local control of brain metastases by stereotactic radiosurgery in relation to dose to the tumor margin. J Neurosurg 2006;104:907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han JH, Kim DG, Chung H-T, Paek SH, Park C-K, Jung H-W. Radiosurgery for large brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol 2012;83:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gondi V, Bauman G, Bradfield L, et al. Radiation therapy for brain metastases: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol 2022;12:265–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Yao Z, Yang H, Liang N, Zhang X, Zhang F. Are immune-related adverse events associated with the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2020;18:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehrer EJ, Gurewitz J, Bernstein K, et al. Concurrent administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors and stereotactic radiosurgery is well-tolerated in patients with melanoma brain metastases: An international multicenter study of 203 patients. Neurosurgery 2022;91:872–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2342–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez M, Hong AM, Carlino MS, et al. A phase II, open label, randomized controlled trial of nivolumab plus ipilimumab with stereotactic radiotherapy versus ipilimumab plus nivolumab alone in patients with melanoma brain metastases (ABC-X Trial). J Clin Oncol 2019;37 (15 suppl):TPS9600–TPS9600. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altan M, Wang Y, Song J, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab with concurrent stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: Analysis of the safety cohort for non-randomized, open-label, phase I/II trial. J Immunother Cancer 2023;11 : e006871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nadal E, Cantero A, Ortega AL, et al. EP08.01–029 NIVIPI-BRAIN, a phase II study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with chemotherapy for patients with NSCLC and synchronous brain metastases. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:S350–S351. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.