Abstract

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors are difficult to diagnose because of the lack of specific indicators. We describe a diagnostically challenging case of an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor primary to the peritoneum.

Case presentation

The patient was a 25‐year‐old male who presented at our hospital with lower abdominal pain. Computed tomography revealed a mass lesion 80 mm in diameter just above the bladder. This was suspected to be a bleeding tumor of the urachus. Since malignancy could not be ruled out, surgery was planned. This revealed a fragile tumor arising from the peritoneum. Following its removal, the tumor was diagnosed by histopathological analysis as an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Conclusion

We describe a case of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor primary to the peritoneum diagnosed by histopathology. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal wall and anterior bladder tumors.

Keywords: abdominal wall, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, histopathological analysis, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, peritoneum

Keynote message.

We report a case with an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor primary to the peritoneum. The occurrence of cases like this is rare because it originates from the abdominal wall. We diagnosed inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor by histopathology. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal wall and anterior bladder tumors.

Abbreviations & Acronyms

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- CT

computed tomography

- IMT

inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

An IMT is borderline malignant and characterized by myofibroblast proliferation with infiltration of inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells. It can occur in any organ of the body but most frequently manifests in the lungs. IMT can be difficult to diagnose due to the lack of specific identifying features in blood tests and imaging studies. 1 In this report, we describe a case of IMT diagnosed by histopathology after surgical resection.

Case presentation

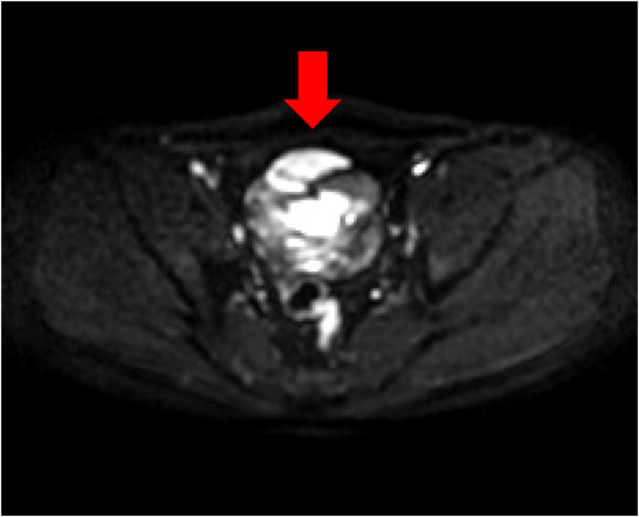

The patient was a 25‐year‐old man with no relevant medical history or family medical history. He visited the Department of Gastroenterology at our hospital for lower abdominal pain. His abdomen was flat and tender, with spontaneous pain in the lower abdomen. Ultrasound examination showed an internally heterogeneous tumor on the cephalic side of the bladder. A contrast‐enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showed a high‐density area of 80 mm diameter just above the urinary bladder (Fig. 1). This was accompanied by fluid accumulation in the surrounding area. It was suspected to be a tumor of the urachus with bleeding. The patient was referred to the Department of Urology. Blood test results were hemoglobin 15.9 g/dL, white blood cells 6580/μL, aspartate aminotransferase 19 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 26 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase 184 U/L, creatinine 0.72 mg/dL, C‐reactive protein 0.16 mg/dL, carcinoembryonic antigens 0.7 ng/mL, and carbohydrate antigens 19–94 U/mL. These are all within their normal ranges. We did not suspect malignancy, so he was followed up with imaging examinations to monitor the bleeding. An abdominal MRI 3 months after the initial visit showed a shrinking mass and a multicellular cystic tumor. Diffusion‐weighted images showed major diffusion restriction (Fig. 2). T2 weighted image showed a high‐signal cystic component, and fat‐suppressed T1‐weighted image revealed a hematoma on the dorsal surface of the tumor in addition to an area suggestive of a fat component. Cystoscopy showed no abnormalities. Since the tumor image was unclear after the bleeding, a biopsy was not planned. Although we suspected a benign tumor after discussion among urologists, we decided to perform surgical resection on standby to confirm the diagnosis and prevent rebleeding. Rapid intraoperative pathological diagnosis was considered but was not performed because it would not affect the treatment plan.

Fig. 1.

Contrast‐enhanced sagittal CT image of the abdomen. At the tip of the arrow, a hyperintense mass 80 mm in diameter is visible just above the bladder with fluid accumulation in the surrounding area.

Fig. 2.

MRI scan of the abdomen. At the tip of the arrow, a horizontal diffusion‐weighted image found limited diffusion associated with the tumor.

Surgery was performed 6 months after the initial medical examination. We reached the anterior bladder cavity through the midline of the lower abdomen, but no tumor was found. When the abdominal cavity was opened, a fragile tumor was found with wall continuity to the peritoneum. The tumor was completely resected and the abdominal cavity was thoroughly cleaned. We closed the wound and finished the operation.

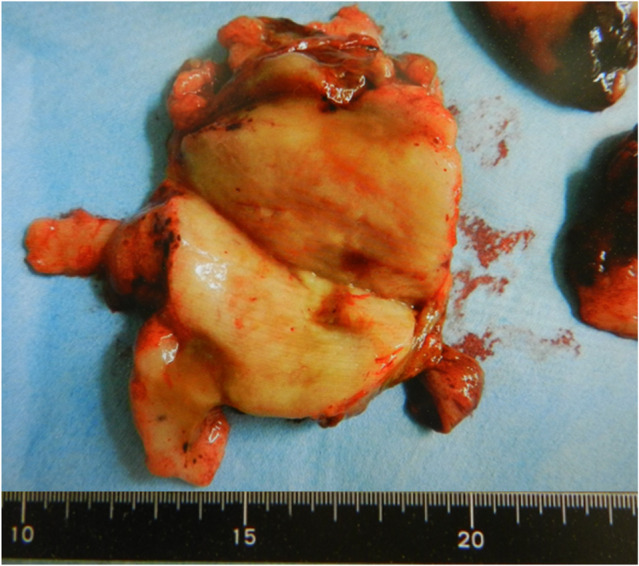

The removed tumor weighed 150 g, and its cross‐section was yellowish‐brown in color and glossy (Fig. 3). The postoperative course was good and the patient was discharged from the hospital on the sixth postoperative day.

Fig. 3.

Tumor cross‐section. The cross‐section was yellowish‐brown and shiny.

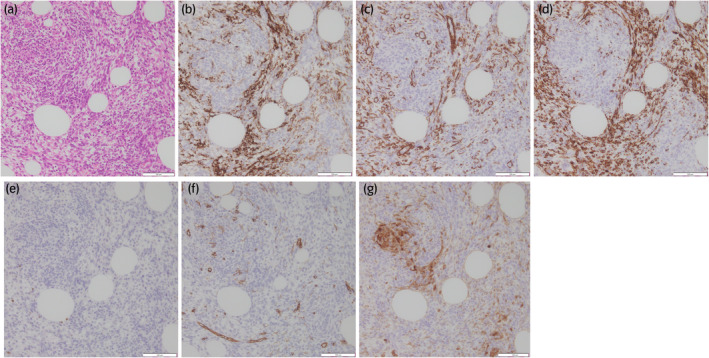

A histopathological examination was performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed spindle cell proliferation with inflammatory cell infiltration, and immunostaining found the tumor to be positive for ALK, smooth muscle actin, and desmin. It was negative for myogenin, CD34, and S‐100 proteins (Fig. 4). Therefore, a diagnosis of IMT was made. The patient is being followed up and doing well with no recurrence 6 months after surgery. We will consider using ALK inhibitors for future recurrences.

Fig. 4.

Histopathological image. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (×200 magnification). Proliferating spindle cells can be seen engulfing adipocytes and inflammatory cell infiltration is visible. (b) ALK stain (×200 magnification). ALK is positive. (c) Smooth muscle actin stain (×200 magnification). Smooth muscle actin is positive. (d) Desmin stain (×200 magnification). Desmin is positive. (e) Myogenin stain (×200 magnification). Myogenin is negative. (f) CD34 stain (×200 magnification). CD34 is negative. (g) S‐100 proteins stain (×200 magnification). S‐100 proteins are negative.

Discussion

IMTs were previously called inflammatory pseudotumors or plasma cell granulomas. However, in 1990, Pettinato reported lesions thought to be inflammatory pseudotumors due to lung inflammation to be tumors composed mainly of myofibroblasts. 2 , 3 Although many cases of IMT have been reported in the lungs and bladder, tumor originating from the peritoneum and located just above the bladder are rare. The incidence of IMT is low and the majority occurs in children and young adults. No difference has been found between the incidence in males and females. Rare cases of recurrence and metastasis have been reported. 4 , 5 IMT has no unique manifestations and no fever or elevated inflammatory reaction. On CT scans, it appears as a heterogeneous internal mass, and MRI scans show moderate signals on T1‐weighted images and high signals on T2‐weighted images. However, since none of these are specific to IMTs, it is often difficult to make a diagnosis based on imaging alone, and histopathological diagnosis is important. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, IMT shows spindle‐shaped tumor cells. Immunostaining is sometimes positive for ALK, and ALK protein expression and gene translocation may be observed. 6 The frequency of ALK protein expression and gene translocation has been reported to be between 33% and 89%. 7 ALK fusion genes such as TPM4‐ALK, TPM3‐ALK, CTLC‐ALK, and RANBP2‐ALK have also been reported. 8 ALK‐positive cases are most common in patients under 40 years of age and are rare in older patients. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 These cases are considered to have better prognoses than ALK‐negative cases because of the higher rate of local progression and distant metastasis in ALK‐negative cases. 12 Other tumors that express ALK proteins include rhabdomyosarcomas, leiomyosarcomas, Ewing sarcomas, malignant schwannomas, and malignant fibrous histiocytomas. 13 Therefore, a diagnosis of IMT requires comprehensive consideration of immunostaining findings and the morphological features found in hematoxylin and eosin staining. In addition to ALK, positive results for pan‐keratin, Cam5.2, CK18, actin, desmin, calponin, and smooth muscle actin; and negative results for S‐100 proteins, CD34, and myogenin support a diagnosis of IMT. 14 Although surgical resection is the usual treatment, crizotinib, an ALK inhibitor, has been found effective in patients with unresectable tumors and those requiring adjuvant therapy. However, this treatment option depends on tumor size and metastasis. 15 , 16

The imaging and blood test results of our patient did not lead us to suspect IMT. We were only able to arrive at this diagnosis after a pathological examination of the resected tissue. This revealed spindle cell proliferation and immunostaining was positive for ALK, smooth muscle actin, desmin, myogenin, and negative for CD34 and S‐100 proteins. Since local recurrence has been reported in previous cases, 2 it is recommended that resection of IMT is performed with adequate tumor borders. Kovach et al. published a review of 44 patients with IMT not limiting site of origin, and surgical resection was suggested for all lesions. 14% of patients who have difficulty undergoing radical resection were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy after surgery. Local recurrence was seen in 8%, but tumor recurrence after complete surgical resection is rare. 17 However, the intraperitoneal tumor in this case was extremely fragile and disintegrated during removal. All parts of the disintegrated tumor were removed completely, and the area was thoroughly cleaned to ensure no tumor cells remained. At the time of writing (6 months after surgery) the patient remains under follow‐up observation but there has been no recurrence. In this case, the tumor was ALK‐positive so the use of ALK inhibitors will be considered should there be any future recurrence. Further research is needed to identify any biomarkers or typical findings that would allow preoperative diagnosis of IMT.

Author contributions

Jurii Karibe: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; project administration; resources; visualization; writing – original draft. Jun‐ichi Teranishi: Supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Takashi Kawahara: Supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Takeaki Noguchi: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Teppei Takeshima: Writing – review and editing. Kimito Osaka: Writing – review and editing. Eita Kumagai: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Tomoe Sawazumi: Writing – review and editing. Satoshi Fujii: Writing – review and editing. Hiroji Uemura: Writing – review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Furugane R, Saito T, Terui K, Nakata M, Komatsu S. An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder in a 12‐year‐old male. J. Jpn. Soc. Pediatr. Surg. 2021; 57: 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pettinato G, Manivel JC, De Rosa N, Dehner LP. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (plasma cell granuloma). Clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1990; 94: 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1995; 19: 859–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maehara T, Iwashina M, Ikot H, Yokoo H. A case of ALK‐negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor originating from the greater omentum in a sixteen‐year‐old. Jpn. J. Diagn. Pathol. 2021; 38: 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, Henkle C, Ellingham T, Perlman EJ. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 2776–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uchida K, Furuhashi N, Araki M et al. A case of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Jpn. J. Diagn. Pathol. 2015; 32: 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katayama S, Hashimoto S, Toyooka K, Nodomi S, Imai T. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder in an 11‐year‐old girl. Jpn. J. Pediatr. Hemol. Oncol. 2020; 57: 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015; 10: 1240–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan JK, Cheuk W, Shimizu M. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase expression in inflammatory pseudotumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001; 25: 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Saito T et al. p53 mutation and MDM2 amplification in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours. Histopathology 2003; 42: 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawrence B, Perez‐Atayde A, Hibbard MK et al. TPM3‐ALK and TPM4‐ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2000; 157: 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007; 31: 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li XQ, Hisaoka M, Shi DR, Zhu XZ, Hashimoto H. Expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in soft tissue tumors: an immunohistochemical and molecular study of 249 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2004; 35: 711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Montgomery EA, Shuster DD, Burkart AL et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the urinary tract: a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases, including a malignant example inflammatory fibrosarcoma and a subset associated with high‐grade urothelial carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006; 30: 1502–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Butrynski JE, D'Asamo DR, Hornick JL et al. Crizotinib in ALK‐rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010; 363: 1727–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagumo Y, Maejima A, Toyoshima Y et al. Neoadjuvant crizotinib in ALK‐rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018; 48: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kovach SJ, Fischer AC, Katzman PJ et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006; 94: 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.