Abstract

Purpose:

Efforts to optimize human-computer interactions are becoming increasingly prevalent, especially with virtual reality (VR) rehabilitation paradigms that utilize engaging interfaces. We hypothesized that motor and perceptional behaviors within a virtual environment are modulated uniquely through different modes of control of a hand avatar depending on limb dominance. This study investigated the effects of limb dominance on performance and concurrent changes in perceptions, such as time-based measures for intentional binding, during virtual reach-to-grasp.

Methods:

Participants (n = 16, healthy) controlled a virtual hand through their own hand motions with control adaptations in speed, noise, and automation.

Results:

A significant (p < 0.01) positive relationship between performance (reaching pathlength) and binding (time-interval estimation of beep-sound after grasp contact) was observed for the dominant hand. Unique changes in performance (p < 0.0001) and binding (p < 0.0001) were observed depending on handedness and which control mode was applied.

Conclusions:

Developers of VR paradigms should consider limb dominance to optimize settings that facilitate better performance and perceptional engagement. Adapting VR rehabilitation for handedness may particularly benefit unilateral impairments, like hemiparesis or single-limb amputation.

Keywords: Virtual reality, Movement rehabilitation, Handedness

1. Introduction

Optimizing human-computer interactions requires modifications of computerized settings to adapt the interface according to user cognitive engagement and performance (Bannon, 1995; Carroll & Long, 1991). These human-computer interactions can have distinct effects on user perceptions, including the sense of agency (Moore, 2016). Movement performance adaptation through computerized interfaces is an advanced approach to augment functional capabilities after motor impairment (Lazarou et al., 2018; Wolpaw et al., 2002). Physical therapy after brain and spinal cord injury is critical to recovering motor function (Behrman et al., 2005), and gains in functional abilities have been positively correlated to therapy dosage (Hsieh et al., 2012; Stevenson et al., 2012). Computerized interfaces, such as virtual reality, (Matallaoui et al., 2017) are increasingly utilized in rehabilitation to address challenges in patient engagement and personalization resulting from the tedium of physical therapy and the heterogeneity of neurotraumas. Optimal design and deployment of VR rehabilitation interfaces require an understanding of how control of these interfaces may be best adapted to maximize functional performance and more positive perceptions, i.e., reflect greater feelings of user engagement. Perceptions of engagement that are of high interest in movement rehabilitation would suggest greater coupling of user intentions to act with observed consequences. This coupling may be temporal (binding, implicit agency) or subjectively stronger feelings of control (explicit agency) (Moore et al., 2012).

The effectiveness of advanced modes of rehabilitation such as VR and robotics (Veerbeek et al., 2017; Winstein et al., 2016) remains uncertain once the dosage is controlled (Laver et al., 2017). Human-level factors (psychological and physical) may be systematically leveraged to improve the efficacy of computerized rehabilitative interfaces. Computerized environments can be tailored on several levels to accentuate motor cognition (Laver et al., 2017). Thus, if participants perceive greater control with each training repetition, then higher rates of learned performance may be expected (Lindgren et al., 2016). The key to unlocking the potential of VR rehabilitation may be the personalization of control settings in commanding devices or avatars that facilitate greater cognitive engagement and performance. On a clinical level, personal characteristics from which to customize rehabilitative platforms include injury type, target function to be restored, and impaired physical limb. With neurotraumas, such as stroke and incomplete spinal cord injury, there is variance in the severity of the injury. Furthermore, one side of the body is typically more affected (Adamovich et al., 2009; Behrman et al., 2005; van Vliet & Sheridan, 2007), which may or may not be the dominant side before the neurotrauma.

The psychological and functional implications of limb dominance (i. e., handedness) have generated mixed conclusions, particularly in rehabilitation contexts. Multiple studies have suggested differences in rehabilitation outcomes after stroke based on hand dominance (Langan & van Donkelaar, 2008; Waller & Whitall, 2005). Waller and Whitall (2005) suggested that differences in baseline motor function post-stroke are independent of hemispheric dominance. However, they also concluded there are clear advantages in training response for right-handed persons with left hemispheric lesions. Conversely, Langan and van Donkelaar (2008) did not observe significant differences in cortical or behavioral responses based on hand dominance after constrained-inducted therapy for stroke. Other evidence indicates that specific neurophysiological states after dominant sphere neurotrauma can determine rehabilitation progress (Keren et al., 1993). Thus, it remains unclear how limb dominance may affect rehabilitation training outcomes or could be better leveraged with computerized interfaces for rehabilitation.

We posit that further investigation is needed to consider the effects of limb dominance on rehabilitation metrics that include performance and cognitive factors such as perceptions. The effects of handedness on perception are relatively unclear, let alone in consideration of computer feedback variations to better rehabilitate clinical populations. While one study indicated that sense of agency, or perception of control, can be higher with the non-dominant hand (Damen et al., 2014), another study has indicated that attribution of movement had no dependence on handedness (Saito et al., 2015). Thus, the role of handedness in agency remains uncertain and may be context-specific. Thus, further investigation of the role of handedness on movement performance and perceptions of movement control in the context of computerized rehabilitative interfaces is warranted.

Perception of control is the belief that one is the true author of their functional action (Moore, 2016). The sense of agency can empower one to perform movements with more purpose and belief in successful rehabilitation outcomes (Zimmerman & Warschausky, 1998). Previous works have demonstrated the relationship between performance and agency (Metcalfe et al., 2013; Metcalfe & Greene, 2007; Vuorre & Metcalfe, 2016). A standard measure for implicit agency is time-interval estimation for intentional binding (Moore & Obhi, 2012). Intentional binding is the phenomenon where one perceives a compression in the time-interval between a volitional action and a subsequent sensory consequence. In the seminal work by Haggard et al. (Haggard et al., 2002), a keypress action was coupled to a sound beep consequence under voluntary and involuntary (transcranial magnetic stimulation) conditions. The perceived time-intervals were shorter after voluntary actions, which is assumed to be associated with more control and a perceived sense of agency. While recent studies have suggested a disconnect between binding and intentional action (Kirsch et al., 2019; Suzuki et al., 2019), multisensory causal binding reflected through varied perceptions in time has an apparent positive link to hand functions performed through computerized interfaces (Nataraj et al., 2020a; Nataraj et al., 2020b; Nataraj & Sanford, 2021). As such, time-perception metrics may still be a window into sensory-based motor learning (Adamovich et al., 2009; Sanford et al., 2020) as done with VR rehabilitation. Computerized platforms such as VR can be readily customized to consider person-specific characteristics. For persons with neurotraumas, such as stroke and spinal cord injury, resulting phenotypic traits are injury severity and which side of the body may be most affected. Understanding how such traits may affect movement performance and perceptions related to said movements during computerized training could be crucial for the effective personalization of such a rehabilitation platform.

Compared to explicit agency measures such as survey responses (Saito et al., 2015), time-perception measures offer practical advantages for VR rehabilitation. Estimating a time-interval is a task wholly distinct from the performance task. Perceptions may not be as affected by personal feelings about performance and reflect the effects of time-perception due to control mode. Intentional binding metrics are also sensitive to external sensory cues (Moore et al., 2009) and reliable in assessing human-computer interactions (Limerick et al., 2014). An orthodox interpretation of intentional binding as a surrogate for implicit agency entails absolute compression of perceived time-intervals compared to actual values. However, for practical applications, such as optimally fitting users to computerized interfaces, identifying conditions (e.g., device parameters) in which users perceive relatively shorter time-intervals than a baseline condition can still be valuable. Furthermore, tuning a human-computer interface to better couple (relatively bind) their actions to observed consequences is beneficial if it improves functional performance (Nataraj et al., 2020b). Our previous work has specifically demonstrated the positive relationship between time-perception measures for binding and performance of functional reach (Nataraj et al., 2020a; Nataraj et al., 2020b) and grasp (Nataraj, 2020) with computerized interfaces. Virtual reality is well suited for tracking these metrics and developing rehabilitation protocols that systematically vary and integrate sensory cues for cognitively-inspired movement training (Moore & Fletcher, 2012). The programmable format of VR allows for customization and adaptation of sensory-based training cues against real-time tracking of performance.

Adaptations in visual feedback within VR environments can be especially effective for generating variations in cognitive factors (Farrer et al., 2008; Nataraj et al., 2020b), learning of functional movements (Sanford et al., 2020; Sigrist et al., 2013), and supporting greater engagement in physical therapy (Lohse et al., 2014). The role of visual feedback is well established in functional reach-to-grasp (Schettino et al., 2003; Winges et al., 2003). Reach-to-grasp is critical for many activities of daily living; therefore, it is an essential component of physical and occupational therapy programs following neurological impairments (Kwakkel et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007). Reach-to-grasp is also a standard target function for restoration with powered assistive devices such as exoskeletons (Farris et al., 2013) and prostheses (Nataraj et al., 2010; Nataraj et al., 2012). For any rehabilitation paradigm relying on computerized interfaces, understanding how variations in control of virtual avatars or real-world devices will affect resulting performance, and related perceptions, may accelerate motor rehabilitation outcomes for reach-to-grasp function.

In this study, a virtual reach-to-grasp task was used to investigate how changes in control of a virtual hand affected performance and a time-perception metric. Participants controlled the virtual hand from first-person perspective through their own hand movements. The visually observed movements depended on a specified control mode. The control modes that were tested included speed changes (Blaya & Herr, 2004; Wege & Hommel, 2005), the addition of mild “noise” interference (Agostini & Knaflitz, 2011; Taylor et al., 2002), and automated assistance (Ronsse et al., 2010). Speed, noise, and automation are settings that may be tuned for an assistive device and induce greater performance and cognition during training. The control modes tested for this study represent a small set of adaptations that are possible for highly customized rehabilitation protocols. However, previous work demonstrates these modes are sufficient to generate significant changes in movement performance and related perception (Nataraj et al., 2020b). The study presented here extends this approach to investigate how changes in performance, and related perceptions, are further affected based on hand dominance.

This reach-to-grasp study primarily examined performance (minimizing reaching pathlength) and time-perception (following grasp contact). For comparative reference, we also examined the relative corrective efforts (movement accelerations) demonstrated to achieve the observed performance and an explicit agency measure (survey). We hypothesized that changes in control modes for a simple virtual reach-to-grasp task would elicit significant variation in performance, and related perceptions, for both dominant and non-dominant hands. Since the subject population was healthy and without prior training on this task, we expected that performance and perceptions, positively indicating greater binding or agency, would be higher and more tightly correlated for the dominant hand given its advantages in controlling limb dynamics (Bagesteiro & Sainburg, 2002). We intuitively posit that more robust capabilities to generate limb actions for this trajectory task would naturally manifest in concurrently improved performance and more positive perceptions. Greater limb control should empower positive perceptions associated with self-attribution to observed actions, including agency and binding. Indeed, a greater ability to make online corrections would presumably result in better tracking of target (i.e., minimal pathlength) trajectories. Furthermore, given the emphasis on minimization of pathlength for performance, we expected better performance and more positive perceptions for the dominant hand due to greater potential for lower joint torque output, i.e., reduced effort, in achieving those target trajectories (Sainburg, 2005). While our study tests non-disabled participants, we expect such studies can still provide a template to inform rehabilitation paradigms. Specifically, these studies may suggest how specific variations in visually-observed control of a computer avatar produce unique performative and perceptional effects pending hand dominance.

2. Material and methods

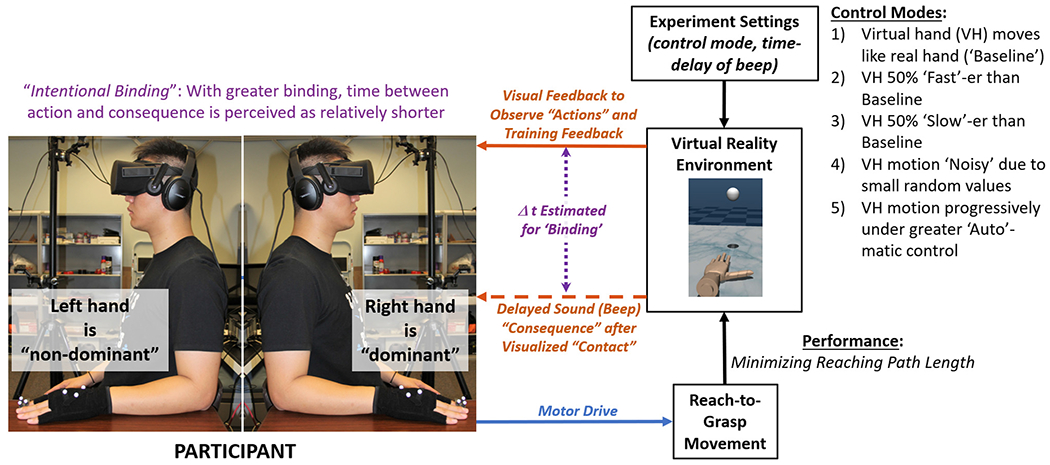

In this protocol, participants controlled a virtual hand to perform a reach-to-grasp task through their own hand motions (Fig. 1). Control modes of the hand were varied while assessing measures for performance (minimizing reaching pathlength), performance efficiency (performance normalized by corrective effort), binding (time perception metric to suggest implicit agency), and explicit agency (survey measures). Each participant repeated the protocol with their dominant (right side) and non-dominant (left side) hands. Order effects of which hand was tested first was neutralized with half of the participants testing with the nondominant hand first before repeating with the dominant hand, and vice versa for the remaining participants.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram is shown for participant performing reach-to-grasp task with a virtual hand under different control modes. Performance and perception (binding) were concurrently measured. The protocol was repeated with both dominant (right side) and non-dominant (left side) hands.

2.1. Participants

In this study, sixteen able-bodied persons (12 males, 4 females, mean age 21 ± 3 years) voluntarily participated. All participants reported they were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. No participant reported nor demonstrated disease, injury, or complications involving cognition or upper extremity function. All participants signed an informed consent form for this study approved by the Stevens Institutional Review Board. A 90% power analysis (eta-squared effect variable) for one-way ANOVA, performed with the Statistics Toolbox for MATLAB® (Mathworks Inc.) and the factor of control modes (five levels, Bonferroni correction of multiple comparisons), demonstrated that n = 8 would be sufficient at alpha level of 0.05 for both performance (as measured by minimal reaching pathlength) and perception (as measured by time-interval estimation for intentional binding) and in either hand for this protocol.

2.2. Equipment (hardware and software)

The virtual hand was a model of a prosthetic hand (MPL, Modular Prosthetic Limb, (Johannes et al., 2011)) in a 3-D physics-based virtual reality environment (MuJoCo, Roboti LLC). The motion of the virtual hand was driven by real-time motion capture of retroreflective marker-clusters placed on the respective participant hand. Size-scaling procedures were applied in real-time to map each participant hand to the virtual hand. A marker-based motion capture system tracked real-time kinematics of marker-clusters placed on the dorsal hand (third metacarpal) and distal segments of the thumb and index finger. The motion capture system included nine infra-red cameras (Prime 17 W by Optitrack®, NaturalPoint Inc.). The markers on the dorsal hand were 9 mm in diameter and affixed via Velcro. The hand marker-cluster drove animation of the virtual hand base segment. The digit markers were 4 mm in diameter and affixed onto 3-D printed platforms attached to the nails with double-side adhesive tape. The digit marker-clusters drove animation of the virtual thumb and index digits. Joint angle changes across the virtual thumb and index digits were based on real-time inverse kinematics solutions that sufficiently satisfied the position and orientation constraints of all three marker-clusters. The only digits animated were the thumb and index finger since the functional task was reaching with precision grasp (Nataraj et al., 2014). Real-time streaming (at 120 Hz) of marker data was enabled through motion capture software (Motive by Optitrack®) and API code written in MATLAB running on a Dell Precisions T7910 Workstation.

2.3. Protocol

2.3.1. Participant preparation

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were re-informed about the protocol. Right-hand size was measured as the maximum spread distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the index finger. This size measurement for each participant was used to scale real-time mapping of hand motion to that of the virtual hand. Participants were then seated with the reaching forearm supported by a tabletop. The chair and table were height adjusted to have shoulders comfortably level and elbow of reaching arm at a right angle (Fig. 2). The subject had Velcro glove, marker-clusters, Oculus® Rift headset (Facebook Technologies, LLC), and noise-canceling headphones (Bose® QuietComfort 35) placed by experimenters. The headphones allowed participants to hear a beep tone (sound consequence for binding measurements) while minimizing all other audible distractions.

Fig. 2.

Experimental set-up used with each participant. A) Participant is shown in a seated position to start each trial. B) Starting position for hand located by digits placed on Velcro strips.

2.3.2. VR reach-to-grasp task

The participant was cued to begin each reach-to-grasp trial by a three-second countdown (Fig. 3). The subject was instructed to proceed with reach-to-grasp with index and thumb digits upon the visible target sphere after the countdown. Color transitions of the target sphere represented the countdown. The color transitions were red at trial time (ttrial) = −2 s, yellow at ttriai = −1 s, and green at ttrial = 0 s, when reach was to commence. The task required subjects to adhere to constant motion velocity as cued by constant speed pacers that began to move at ttrial = 0 s. The pacers ceased movement at ttrial = 4 s or earlier if the participant made premature grasp contact. Participants were instructed to maximize reach-to-grasp performance to the best of their abilities across three criteria: (1) minimize reaching pathlength, (2) match hand reaching velocity to speed pacers, and (3) grasp the target sphere with thumb and index finger at consistent locations. Participants were told that the first criterion (pathlength) was of primary importance but to consider all three criteria to promote task consistency. Each trial lasted up to a maximum of 10 s, including the countdown. Thus, the participant had 7 s to complete reach-to-grasp with a performance goal to complete in precisely 4 s. Although ecologically valid reach-to-grasp is approximately 1 s (van Vliet & Sheridan, 2007) in duration, this task was intended to emulate a task requiring more focus than device-based rehabilitation (Hochberg et al., 2012).

Fig. 3.

Participant shown reaching with non-dominant side to control virtual hand in a computerized environment. Top Left) Participant actively viewed virtual hand while reaching own hand being motion tracked. Top Right) Close-up of the virtual hand shown as it approached target sphere to grasp. Bottom) Three-second countdown to reach shown with color transitions of target sphere prior to reach-to-grasp.

Once the virtual hand grasped the target sphere with the index and thumb digits, the sphere instantly changed color from green to black, and the virtual environment was suspended in place. This final color-change event informed the participant that grasp action was successfully completed. A short-duration (~100 ms), moderate-pitch (1000 Hz) sound beep was provided through the headphones at a given time-interval following completed grasp action. The time-interval varied across trials. The participant was asked to verbally estimate this time-interval between the color-change of the sphere (upon grasp contact) and the start of the beep to the best of their abilities. The participant was previously instructed that the interval could be any duration from 100 to 1000 ms in denominations of 100 ms. The actual intervals were always 100, 300, 500, 700, or 900 ms. For each block of trials to test a control mode, the number of trials presented at a specific time-interval was based on a Gaussian distribution centered at 500 ms. Participants were presented time-intervals randomly across trials, as done in (Moore & Obhi, 2012), but reported integer values from 1 to 10 corresponding to 100–1000 ms estimates, respectively. Participants did not make estimates with the view of a clock, as is commonly done because our functional task was so visually dominant. Participants needed to continually view and register visual impressions of their control of a virtual hand such that additionally requiring a view of a clock would be cognitively disturbing. Participants were not presented feedback about their performance (i.e., pathlength values) trial to trial. As such, no positive reinforcement learning (Boakes, 2021) was expected beyond the participant’s inferences of their experiences.

2.3.3. Varying control modes

All participants performed a block of trials of the reach-to-grasp task for each of five different control modes, which were randomly presented. As previously mentioned, the control modes in this study included modifications in speed, the addition of mild noise, and automation. The control modes were as follows:

(1). Baseline

The virtual hand moved in equal distance proportion to the real hand in all three dimensions. This control mode served as the standard reference from which all other modes were modified.

(2). Slow

The virtual hand moved in all three dimensions at a speed that was 50% slower than Baseline. The virtual hand appeared ‘sluggish’, and the participant needed to move the real hand 50% faster and further to compensate and complete reach-to-grasp as intended.

(3). Fast

The virtual hand moved in all three dimensions at a speed that was 50% faster than Baseline. The virtual hand appeared ‘hyperactive’, and the participant needed to move their own hand 50% slower and shorter to compensate and complete reach-to-grasp as intended.

(4). Noise

The virtual hand was affected by mild to moderate noise compared to Baseline. A small random value was added in each of the three position dimensions. The random value would occur over [−X, +X], where X = 1 cm per 12 cm/s of hand velocity. Thus, random positions errors were generated that were less than 10% of hand velocity. This noise level produced a visual tremor to the virtual hand that was noticeable but not distracting or challenging to complete each trial.

(5). Auto

The virtual hand was progressively (linear with time) under greater automatic control. At the start-time of reach (ttriai = 0 s, treach = 0), the participant controlled the virtual hand as with ‘Baseline’. Over the designated 4-second reach period, the position of the virtual hand (posVR—hand) was a weighted average of the true hand position (postrue) and a pre-defined optimal position (posopt) corresponding to the minimal path trajectory. The virtual hand position was given as: . At treach = 4 s, the virtual hand would be at the sphere, but the participant still needed to grasp volitionally to complete the trial.

2.3.4. Experimental testing blocks

Participants performed a block of 20 consecutive trials for each of the five control modes, repeated for the dominant and non-dominant hands. The first three trials served as ‘practice’ and always included a presentation of a time-interval between contact and beep fixed at 1000 ms (1 s). The participants were aware these practice trials were intended to gain initial familiarity with the control mode and to re-calibrate their perception for a time-interval of 1 s. The remaining 17 trials in the block were used to assess performance and binding perceptions, and time-intervals were randomly varied between 100 and 900 ms as previously described. After each trial, perceived time-intervals were assessed as previously described. After each block, the participant was provided five minutes to rest and complete a survey to rate their subjective experiences for assessment of explicit agency.

2.3.5. Surveys

After each block, the participant completed a 1-statement survey to rate their subjective perception of the presented control mode. Participants were asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale (−2 = strongly disagree, −1 = disagree, 0 = neutral, +1 = agree, +2 = strongly agree), to what extent they agreed that “the observed VR hand motions reflected their intentions”. The survey responses served as an explicit, or conscious, measure of agency (Moore et al., 2012) for each control mode. Given the relative simplicity of our reach-to-grasp task for neurotypical persons, the survey question is intended to indicate the perception of control ‘felt’, as opposed to control ‘used’, as described in Potts and Carlson (2019). Unlike binding measurements, which were done with each trial, the survey for explicit agency was only presented once after each block. Pilot investigations demonstrated participants were not inclined to vary their survey responses with each trial within a block of trials for any given control mode.

2.4. Data and statistical analysis

The following data metrics were assessed across participants and control modes for both the dominant (right) and non-dominant (left) hands:

-

Performance (minimizing pathlength) – The 3D motion pathlength of the hand marker-cluster was computed as:

where i = time index, N = total number of time-points until grasp contact at a sampling frequency of 120 Hz, px, py, pz = x, y, z position of hand marker-cluster.

To interpret greater performance as higher positive values, performance was taken as the inverse of pathlength (i.e., performance = P−1 or ) since the performance objective was to minimize pathlength.

-

Performance efficiency (performance normalized by effort measure) - Since the target motion trajectory was constant velocity, non-zero accelerations were interpreted as corrective efforts. The total 3-D acceleration at each time index was computed as:

where i = time index, ax, ay, az = x, y, z acceleration of hand marker-cluster.

Performance efficiency was performance (P−1) divided by the average total 3-D acceleration during reach.

Intentional binding (time-interval estimation) – Positive (greater) binding was indicated by underestimation of presented time-intervals. An overestimation of true time-intervals would indicate repulsion, but relative binding can be interpreted as less repulsion (i. e., negative values, but closer to zero). Relative binding measurement for each trial was taken as the true time-interval subtracted by the verbally estimated time-interval from the participant. Based on intentional binding, greater underestimation of time-intervals indicated greater compression (shortening) of the perceived time-interval to implicitly show relatively greater agency (Suzuki et al., 2019). This study also accepted relative underestimation, e.g., less overestimation, as a positive indicator of relative binding (Nataraj et al., 2020b). No trial data were excluded.

Explicit agency (survey response): Assessment for explicit agency was simply the Likert scale response for each control mode block.

The following statistical analyses were performed using Statistics Toolbox functions in MATLAB:

A two-way ANOVA was performed to observe if an interaction existed between the two factors of control modes and hand dominance. This two-way ANOVA was repeated on the primary metrics of interest of performance and intentional binding.

To observe variations in metrics based on control modes specific to each hand, repeated-measures one-way ANOVA was done on each metric for each hand. Post hoc comparisons were made with Bonferroni correction. The p-value, F-statistic, and eta-squared metric were reported for relative significance and effect size. This one-way analysis was desirable to observe specific patterns within the non-dominant hand case using a similar analysis pipeline for the dominant hand done in a previous study (Nataraj et al., 2020b) when handedness was not a factor. Furthermore, this one-way analysis tests simple main effects within each hand case if the two-way ANOVA suggests a significant interaction.

The relationship between performance and binding was assessed from a linear regression analysis. The F-statistic and p-value were computed to refute the null hypothesis that the slope coefficient was equal to zero and suggest a significant relationship with perceptional binding.

A paired t-test (two-tailed) was used to assess aggregate (pooling data across control modes) simple effect differences in each metric between dominant and non-dominant hands.

3. Results

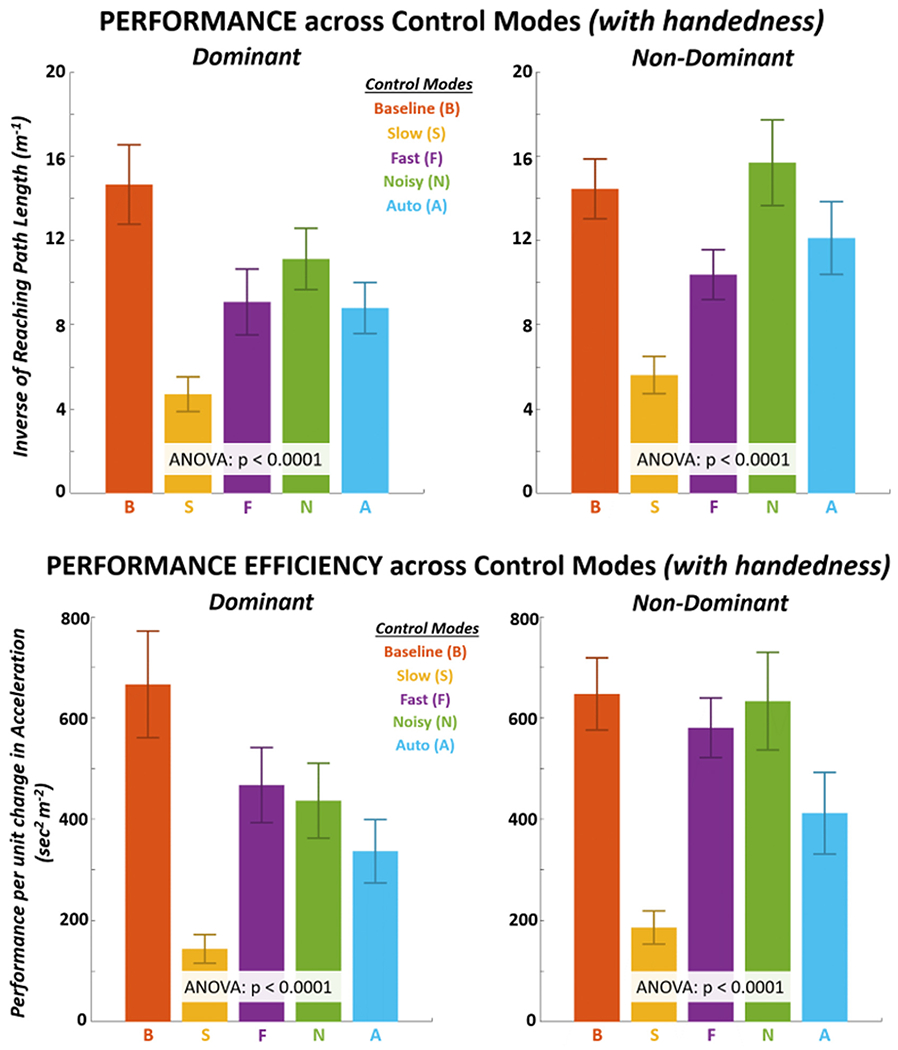

A two-way ANOVA indicated a significant interaction (p < 0.05) between factors of control modes and handedness for performance (p = 5.4E-09), binding (p = 1.6E-04), and performance efficiency (p = 1.1E-06) metrics. The only exception to interaction was with explicit agency in which there were also no significant effects. As such, we primarily report one-way ANOVA results to describe simple effects across control modes within each hand case. The mean performance and performance efficiency for each control mode with both hands are shown in Fig. 4. There were significant differences (p < 0.0001) across control modes for both metrics for each hand with a large effect size (η2 > 0.80). As specified in Tables 1A, 1B, and 1C, all pairwise differences between control modes were significant (p < 0.05) for performance except Fast-Auto on the dominant hand and Baseline-Noisy on the non-dominant hand. All pairwise differences between control modes were significant (p < 0.05) for performance efficiency (Tables 2A, 2B, 2C) except Fast-Noisy for both hands and additionally Baseline-Fast and Baseline-Noisy on the non-dominant hand. Baseline performance and performance efficiency were the highest for the dominant hand. Performance was comparatively high for both Baseline and Noisy modes with the non-dominant hand.

Fig. 4.

Mean (±s.d.) performance (TOP) and performance efficiency (BOTTOM) across control modes for the dominant and non-dominant hand.

Table 1A.

Mean performance (inverse reaching pathlength, m−1) across control modes with dominant and non-dominant hand.

| Side | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Dominant | 14.7 ± 1.8 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 1.6 | 11.1 ± 1.5 | 8.8 ± 1.2 | 96.6 | 1E-29 | 0.85 |

| Non-dominant | 14.4 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 10.4 ± 1.2 | 15.7 ± 2.0 | 12.1 ± 1.7 | 103.5 | 1E-28 | 0.86 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 2A.

Mean performance efficiency (performance over acceleration, s2/m2) across control modes with dominant and non-dominant hands.

| Side | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Dominant | 666 ± 105 | 144 ± 28 | 467 ± 74 | 437 ± 74 | 336 ± 63 | 102.0 | 2E-28 | 0.85 |

| Non-dominant | 647 ± 71 | 186 ± 33 | 581 ± 59 | 633 ± 96 | 412 ± 81 | 112.2 | 1E-29 | 0.87 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

The mean relative binding and explicit agency for each control mode across both hands are shown in Fig. 5. The mean values for relative binding were negative (net repulsion) for all control modes, including Baseline. A one-sample t-test on the mean value for Baseline for both hands indicates a significant difference (p < 0.001) from zero (i.e., net repulsion effect). ANOVA demonstrated a significant difference in relative binding across control modes for both dominant (p < 0.0001) and non-dominant (p < 0.0001) hands. Greater binding is indicated with more positive time-interval values. As such, these results indicate a measure of repulsion on average for all control modes but higher relative binding as indicated by the less negative absolute values, i.e., less overestimation, for time-interval differentials. There was a medium effect size (η2 = ~0.30) in significant difference for both hands (Tables 3A, 3B, and 3C). Significant pairwise differences were found for the Slow control mode with the dominant hand and the Baseline control mode with the non-dominant hand. The Slow mode notably produced the lowest relative binding for the dominant hand. For the non-dominant hand, Baseline notably produced the highest relative binding among control modes. There were no significant differences observed across control modes for explicit (survey-based) agency (Tables 4A, 4B, and 4C).

Fig. 5.

Mean (±s.d.) relative perceptional binding (TOP) and explicit agency (BOTTOM) across control modes for dominant and non-dominant hands.

Table 3A.

Mean relative binding (time-interval underestimation, ms) across control modes with dominant and non-dominant hands.

| Side | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Dominant | −66 ± 32 | −122 ± 29 | −69 ± 30 | −77 ± 38 | −70 ± 33 | 7.58 | 4E-05 | 0.30 |

| Non-dominant | −58 ± 26 | −95 ± 27 | −95 ± 22 | −102 ± 44 | −113 ± 28 | 6.82 | 1E-04 | 0.29 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 4A.

Mean explicit agency (Likert scale: +2 strongly agree to −2 strongly disagree) across control modes with dominant and non-dominant hands.

| Side | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Dominant | −0.09 ± 0.76 | 0.04 ± 0.67 | −0.23 ± 0.65 | −0.11 ± 0.58 | 0.17 ± 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.04 |

| Non-dominant | 0.01 ± 0.37 | −0.05 ± 0.66 | −0.19 ± 0.68 | 0.15 ± 0.34 | 0.08 ± 1.07 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.03 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Scatter plots of data points representing mean performance versus mean relative binding for each participant and control mode pairing are shown in Fig. 6. Scatter plots for both dominant and non-dominant hands are fitted with regression lines. The slope parameter, indicating the relative relationship between performance and binding, was positive and significantly non-zero (p < 0.01, F-stat = 11.43) for the dominant hand. However, the fitted slope to data for the non-dominant hand was not significantly non-zero (p > 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Linear regression applied on mean performance and mean binding data points for each participant and control mode. For the dominant hand, F-stat for regression is 11.43 with p = 0.0012. For non-dominant hand, F-stat for regression is 0.71 with p = 0.402.

In Fig. 7, shifts in metrics from dominant to non-dominant hands are shown. Positive shifts indicate greater values for the non-dominant hand. Handedness shifts across modes were significant (p < 0.001) for all performance and perception metrics except for explicit agency (p > 0.05). As specified in Tables 5A, 5B, and 5C, the shifts in performance and performance efficiency across modes were significant with a large effect size (η2 > 0.40). Shifts were positive (greater for non-dominant hand) in all modes except for Baseline. In Tables 6A, 6B, and 6C, shifts in binding are shown that were significant with medium effect size (η2 = ~0.30). Shifts were negative, i.e., greater values for the dominant hand, for three of the five control modes.

Fig. 7.

Mean shift in metrics from dominant to non-dominant sides across control modes.

Table 5A.

Mean shifts from dominant to non-dominant hand for performance (m−1) and performance efficiency (s2/m2).

| Metric | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Performance | −0.21 ± 2.4 | 0.91 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.5 | 16.9 | 1E-10 | 0.49 |

| Efficiency | −18 ± 121 | 42 ± 45 | 113 ± 105 | 196 ± 76 | 75 ± 72 | 12.5 | 1E-07 | 0.42 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 6A.

Mean shifts from dominant to non-dominant hand for relative binding (ms) and explicit agency (Likert).

| Metric | Control mode |

ANOVA |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | F-Stat | p-val | η2 | |

| Relative binding | 8 ± 29 | 28 ± 32 | −25 ± 44 | −24 ± 60 | −43 ± 43 | 6.55 | 1E-04 | 0.27 |

| Explicit agency | 0.11 ± 0.77 | −0.09 ± 0.73 | 0.04 ± 0.77 | 0.04 ± 0.79 | −0.09 ± 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

Comparisons in the aggregate results for each metric between the use of the dominant and the non-dominant hands are shown in Table 7. Relative binding is significantly (p < 0.05) greater for the dominant hand. Performance and performance efficiency were significantly greater (p < 0.0001) for the non-dominant hand. No significant difference was observed for explicit agency between dominant and non-dominant hands.

Table 7.

Paired t-test comparison of metrics for dominant hand versus non-dominant hand.

| Metric | Dominant | Non-dominant | Shift (dominant non-dominant) | T-Stat | p-val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative binding (ms) | −81 ± 38 | −93 ± 35 | −11.4 ± 49 | 2.0 | 0.049 |

| Explicit agency (Likert) | 0.0 ± 0.73 | 0.0 ± 0.67 | 0.0 ± 0.71 | 2E-16 | 0.99 |

| Performance (m−1) | 9.7 ± 3.6 | 11.6 ± 3.8 | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 6.9 | 1E-09 |

| Performance efficiency (s2/m2) | 410 ± 186 | 492 ± 189 | 82 ± 112 | 6.3 | 2E-08 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of hand dominance on performance and perception metrics during a virtual reach-to-grasp task. Various control modes of the virtual hand were applied to broadly generate changes in performance and perception and observe potential relationships. We primarily observed significant changes in performance, performance efficiency, and time perception (binding measure) with variation in control modes and across hands. Results regarding explicit agency were inconclusive. Performance and relative binding exhibited a significant positive correlation for the dominant hand. This performance-perception correlation was also positive but inconclusive for the non-dominant hand. These correlative findings between higher relative compression of time-intervals and greater performance suggest a potential role of perceptional metrics for improved rehabilitation gains in limbs perceived as dominant. This result may explain, in part, the improved motor outcomes observed in stroke patients rehabilitating the dominant versus the non-dominant hand (Harris & Eng, 2006). Limb dominance has demonstrable effects on movement symmetry (Sadeghi et al., 2000), relative force output (Kovaleski et al., 1997), and unique variations in muscle activation patterns (Hageman et al., 1988).

The experience of agency remains unclear in our VR protocol, given that the net bias towards repulsion for time-interval estimates and explicit agency measures were inconclusive. While significant shifts towards greater relative binding were observed, the repulsion bias and no corroboration from explicit agency measures challenge absolute conclusions about agency. While intentional binding has been presented as an implicit measure of agency (Haggard et al., 2002), it is plausible that purely time perception effects from sensory (visual) distortions (Van Wassenhove et al., 2008) may have also affected the metric beyond perceptions of control. As such, the goal of perceptional approaches to optimize computerized motor rehabilitation may be better interpreted more generally as mitigation of the lengthening of time-perception as a vehicle to accelerate functional gains. Furthermore, there may be greater potential for such approaches when the impaired limb is perceived as dominant.

Strategies to address unilateral impairment include the promotion of functional gains upon the impaired limb through cooperative tasks (Sainburg et al., 2013) and mirror therapy (Sütbeyaz et al., 2007). However, another strategy to accelerate rehabilitation outcomes may be encouraging psychology of dominance upon the impaired limb. In lieu of causal analysis, correlative findings from our study suggest that binding perceptions, and its positive relationships with performance, is greater with the dominant limb. As such, perception-based motor rehabilitation with VR may accelerate functional outcomes through co-maximization of certain perception and performance measures for the dominant limb. We had postulated that the correlation between perception and performance would be greater with the dominant limb due to improved control of limb dynamics for this trajectory task (Sainburg, 2005). However, absolute performance was greater for the non-dominant hand, which we later attribute, in part, to our task being relatively simple. In simpler tasks without performance feedback, advantages in control and perceptions towards motor learning with the dominant hand may be diminished. Similarly, the coupling between perception and performance may also be further reinforced against greater task complexity.

Our measurement of perceptional binding imposed a variation from traditional approaches that examine binding with discretized performance actions, e.g., key press (Haggard et al., 2002). In this way, action initiation is tightly coupled with the sensory consequence. In this study, we follow a template from our previous works (Nataraj et al., 2020a; Nataraj et al., 2020b; Nataraj & Sanford, 2021) whereby we examine an ‘extended’ action with a prolonged movement phase (e.g., reach) prior to a terminating action (e.g., grasp). This approach was necessary to allow participants to ‘experience’ the effects of each control mode and modulate perception before the grasp action, which ultimately incited the sound beep. This approach to measuring ‘second-order’ binding has more significant implications for rehabilitation device interfaces because users must continually observe and feel device operation to register their perceptions of time or control.

In our study, significant changes in relative binding and performance metrics were observed across the control modes tested for both dominant and non-dominant hands. We attribute net repulsion (mean time-intervals differences were ‘negative’) in our experimental protocol, in part, to a virtual hand that appeared artificial (prosthetic hand) and the computation of second-order binding on grasp that followed an extended reach phase. A previous study investigating congruency effects during an embodiment of a robotic hand observed net binding effects, but for the simple, classical keypress task (Caspar et al., 2015). Other studies that introduce complexity through multi-event procedures to discern binding to secondary effects also reported positive binding values (Ruess et al., 2018; Yabe et al., 2017). Again, however, the task was restricted to a simple keypress task, unlike our functional reach-and-grasp task in VR that requires continuous user control of reach before registering binding to the terminal action of grasp.

We observed a group repulsion effect (i.e., for all control modes), including Baseline. Thus, we attribute this net repulsion to our protocol since we would not necessarily expect a loss of binding in the Baseline case whereby VR hand actions are perfectly coupled, both spatially and temporally, to the actual participant hand. Despite the absolute repulsion measures, there were notably unique effects for relative binding depending on the control mode and which hand was used. Relatively high performance and binding for Baseline were observed with both hands. To what extent our binding measure reflects agency is unclear. However, this finding may still be expected since Baseline provided the best visuo-proprioceptive match (Pereira et al., 2009) and embodiment (Kilteni et al., 2012) between virtual and natural hands. As such, these features to promote consistency in sensory feedback may have mitigated potential distortions in time-perception (Van Wassenhove et al., 2008). As such, we reasonably expected, and primarily observed, higher performance and binding with the Baseline case and generally sub-optimal results for other control modes in which distortions were more apparent. Specific reductions in performance and binding may be attributable to handedness in conjunction with control mode, which was a central investigative motivation for this study, rather than universal reductions. Compared to Baseline, lower relative binding (significant pairwise differences) was observed with the non-dominant hand for all other control modes. Conversely, control modes with the dominant hand produced relatively smaller reductions from Baseline than the non-dominant hand. These findings indicate that binding perceptions were more sensitive to alterations in control modes with the non-dominant hand. Thus, it may be crucial for perception-based VR rehabilitation of a nondominant limb to ensure ecological conditions, such as embodiment and reflections of actual physical actions, within the virtual environment.

While actions with the dominant hand were generally more resilient against reductions in relative binding from Baseline, the most notable reduction in binding was observed with the Slow control mode. The Slow mode was primarily distinguished by the additional physical effort required to complete the task. The person must reach further and faster to compensate for sluggish control perceived with the virtual hand. In addition, with the Slow mode, there is certainly sensory misalignment (Cressman & Henriques, 2010) in proprioceptively resolving the virtual hand against one’s own hand, which is required to move faster to have the virtual hand match the pacer speed. This challenge to sensory-temporal integration could most certainly create sensory-level distortions upon time perceptions (Van Wassenhove et al., 2008).

To whatever extent the agentic perception of control may be reflected in the binding results for the Slow mode, it may be through effort. However, the link between perception of control and effort is uncertain. A previous study has suggested that physical effort can boost agency (Demanet et al., 2013), but if cognitive resources are depleted with that effort, then agency can lower (Howard et al., 2016). In this study, it is plausible that effort across the other control modes was interpreted as similarly low, and the added effort with Slow became ‘relatively’ more cognitively taxing with the dominant hand. These potentially, and concurrently, adverse effects in reducing agency, lengthening time-perceptions, and lowering performance with the Slow mode may explain, in part, why this mode was so distinct from Baseline. This distinction was evident even compared to other control modes in driving the performance-binding relationship at the lower ranges of both variables. The Auto condition with the non-dominant hand also demonstrated shallow relative binding, just as the Slow mode. Given the Auto condition has ‘progressive’ shifting from fully voluntary to fully automated (involuntary) control throughout the movement, there may be similarly interpreted distortions in the sluggishness of voluntary control. However, our inability to observe changes in our explicit agency measures across any control modes makes conclusions about perceptions of control more difficult.

The speed-dependence results for performance are similar to that observed in Metcalfe and Greene (2007), where scroll speeds varied for a mouse cursor task, and speed had a greater impact on performance than perceptional judgments. In our study, the Fast (lower effort) condition improved performance over Slow control for both hands. As such, greater performance sensitivity to variations in speed was observed with both hands, while time-perceptional sensitivity was only apparent in the dominant hand. The implication to rehabilitation may be that minimizing perceptions of greater physical and mental effort is especially important for re-training a dominant limb. These effects on relative binding from speed/effort were not observed for the non-dominant hand.

The higher overall relative binding and sensitivity of binding to speed in the dominant hand may be in part explained by the experience of flow to the extent that relative binding can be attributed, at least in part, to agency. Vuorre and Metcalfe (2016) found an unexpected dissociation between agency and experience of ‘flow’. They attribute this contradictory observation to the dependence of flow on the loss of reflective self-consciousness (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2009) while agency definitively requires central involvement of the self as the actor (Gallagher, 2007). In our experimental set-up, a person may exhibit greater flow with the non-dominant hand given higher performance and lower relative binding than the dominant hand. This loss of self-consciousness, which is a hallmark of flow, may also be related to the reduction in attention stemming from the simplicity of our task. Reduction in attentional resources, which can negate either implicit or explicit agency (Hon, 2017), can be associated with increases in cognitive loading (Qu et al., 2021). Alternatively, as in our protocol, given a highly simple task such that participants are exceptionally confident in successful completion, feelings of ‘automation’ (Wen et al., 2019) can materialize to reduce agency and conscious engagement similarly. Thus, the lack of engagement with task simplicity may have better facilitated a state of flow with the non-dominant hand resulting in higher performance.

In contrast, the inability to observe differences in explicit agency and a bias towards repulsion in our binding measures challenge conclusive links between flow and agency based solely on handedness. If our binding results more purely reflect changes in time perceptions, the performance sensitivity to binding may reflect error-prediction processes (Kagerer, 2016; Tseng et al., 2007) that are finely tuned for the dominant hand. These more established processes with the dominant hand may manifest from greater usage resulting in greater sensitivity to perceived distortions (Van Wassenhove et al., 2008) from Baseline, where action-event expectations are better resolved. As such, our current results are preliminary in contextualizing perceptional concepts relating to control, flow, and effort for computerized interfaces for motor rehabilitation. However, further investigation into all three components for motor rehabilitation is highly warranted. All three components are well integrated with performance-driven platforms for movement. Users may have compromised control (due to a neuromuscular disability) while incentivized to find flow (undergo several sequential repetitions of a task) and exert efforts (given reduced physical capacities).

The finding of lower performance, despite higher relative binding, with the dominant hand was paradoxical to our stated hypothesis. Performance was similarly high for both hands with the Baseline training condition, which may be attributable to the simplicity of the motor task (Gopher & Lavie, 1980), in which skill advantages to make online motor corrections with the dominant hand are relatively nullified. However, there were significantly greater reductions in performance for the non-Baseline modes with the dominant hand. These findings suggest that with greater relative binding from the dominant limb, there was more performance sensitivity to perceptional deviations in feedback compared to Baseline. Agency is modulated by greater congruency between expected and actual sensory outcomes (Sato & Yasuda, 2005). Our study suggests a more active role for perception whereby when higher relative binding is preserved, distortions in perceptional feedback congruency have more detrimental effects on performance. For VR rehabilitation purposes, higher relative binding with the dominant limb may necessitate high-fidelity feedback that more accurately reflects user actions to maximize performance, as with the Baseline case. In contrast, when the limb is non-dominant, and relative binding is inherently lessened, there may be a greater ability to tolerate distortions in perceived control of a virtual avatar and better maintain performance for this simple task. Such tolerance may not reflect itself when the task becomes more complex, in which case, positive perceptions and performance may be more absolutely linked.

Another factor that may have relatively diminished performance with the dominant hand was the lack of performance feedback. For example, it is conceivable that lack of positive reinforcement feedback (Mataric, 1994; Nataraj et al., 2020a) may have dampened the motor learning potential with the dominant hand that otherwise would have resulted in greater performance. Similarly, flow may have been readily maintained with the non-dominant hand without performance feedback as participants can continue to maintain metacognitive beliefs of high performance (Kennedy et al., 2014). Given the simple task, belief in high performance is naturally maintained with either hand or any control mode. However, with the dominant hand, which expressed more relative binding, the distortions presented with altered control modes may be intrinsically interpreted as errors in place of external performance feedback. Thus, with the non-dominant hand, belief of high performance may be relatively better maintained to further facilitate flow-dependent performance.

Although this study observed a significant positive binding-performance relationship in aggregate for the dominant hand, the Noisy mode was a relative outlier. For the dominant hand, binding was relatively more diminished with Noisy but produced relatively higher performance among non-Baseline modes. Metcalfe and Greene (2007) observed a reduction in agency judgment for a mouse-cursor task when control is infected with turbulence, similar to ‘noise’. Our task involved 3-D control of a virtual hand from which noise may have different sensorimotor effects. Certain sensory noise levels can enhance feedback to augment motor performance (Priplata et al., 2002). In our study, the noise produced a similarly high performance to Baseline for the non-dominant hand but relatively more adverse ideomotor effects (Brass et al., 2001) in the dominant hand. Since higher relative binding with the dominant hand did not compensate for performance with the Noisy mode, visual sensory noise in VR training may not have facilitated perception-related gains in performance.

Performance efficiency largely followed trends in performance except for the Fast control mode. For both dominant and non-dominant hands, there was a notable increase in performance efficiency compared to Baseline. The reduced effort with Fast may have allowed persons to minimize acceleration corrections. The shift in increased efficiency with the non-dominant hand was greater for Fast than Auto, while the shift in increased performance was greater for Auto than Fast. These results suggest that with lesser hand dominance, higher performance may be achieved with lesser efficiency for automated conditions despite lower relative binding. Furthermore, the notable differential of higher performance efficiency for Fast (lower physical effort) and Slow (higher physical effort) was seen for both hands. Since higher relative binding for Fast was only observed for the dominant hand, we may attribute this phenomenon to how corticomotor excitability is affected by handedness and motor demand (Teo et al., 2012). The higher relative performance and performance efficiency, despite lower relative binding, in the nondominant hand may again possibly be explained by greater experience of flow, whereby one experiences being ‘in the zone’ but still perceives less agency given the state of de-centralization with respect to self (Kennedy et al., 2014; Metcalfe et al., 2013; Metcalfe & Greene, 2007; Vuorre & Metcalfe, 2016).

This study suggested greater sensitivity of time-perception bindings, compared to explicit agency, to altering computerized control modes with both hands. These findings for the non-dominant hand similarly follow those for the dominant hand in this study and previous ones performing reach and force grasp tasks (Nataraj, 2020; Nataraj et al., 2020b; Nataraj & Sanford, 2021). However, limitations in our measurement of explicit agency, including a single measurement per block, leave the potential effectiveness of explicit agency measures in our protocol uncertain. Furthermore, other potential implicit measures for agency may be more effective than time-interval estimation for intentional binding, especially for rehabilitation purposes. Physiological measures such as electromyography and electroencephalography have been previously implicated with the sense of agency (Kang et al., 2015). These measures offer the advantage of not requiring verbal estimates that may induce cognitive stress during longer sessions. Due to the stochastic nature of these signals, probabilistic methods to identify implicit agency (Ryu & Torres, 2018) may offer the best pathway for agency-based motor rehabilitation.

Other limitations of this study include the examination of only a single movement parameter, a single level for each control mode type, and task simplicity. For highly customized VR rehabilitation, several movement parameters may be measured concurrently to assess functionality. Furthermore, several modes or settings may be varied to optimize rehabilitation training. Future studies should further consider how spectrums of movement parameters and training settings respond to hand dominance and facilitate perception-based performance gains. Certainly, the final frontier for this line of work would be assessing performance and perceptional responses from actual clinical populations in future studies. Another notable limitation in our study regarding the investigation of handedness effects was restricting our participants to only non-disabled and all right-hand dominant. There are differential cognitive-perceptual loads pending which side is dominant (Liang et al., 2019).

Additional limitations mainly involved our measurements of explicit agency. Due to feelings of self-efficacy (Buxbaum et al., 2020), we may have expected higher explicit agency to be related to improved performance. However, unlike with performance and relative binding measures, we could not draw conclusive variations in our measurements of explicit agency across control modes. This finding may be attributable to our narrow scale of responses (5-point Likert scale), insensitivity to our survey question, and only querying participants once per trial block instead of each trial. A broader range of allowable responses (e.g., 0–100 scale) may have produced better concurrency in agency results with those from our binding and performance measures. Another procedural limitation that may have introduced perceptual bias includes using a reference of a 1-second interval during the three initial practice trials for each condition (control mode) block; however, pilot investigations indicated subjects were more comfortable making estimates by essentially guessing fractions of this reference value. Ultimately, our protocol as pursued makes definitive conclusions about perceptions of control difficult. Inferences about absolute control must be taken with caution due to the net repulsion effect observed in the binding results and the inability to corroborate those findings with explicit agency measures.

Rehabilitation can be effectively strategized based on whether dominant or non-dominant limbs are affected and what specific functional ability is being restored (Wang & Sainburg, 2007). These functional abilities typically involve advanced skill sets beyond simple reach-to-grasp for specific clinical populations to perform complex activities of daily living (Adamovich et al., 2009; McCabe et al., 2015). Perception-based motor training with VR may be a viable approach for more effective rehabilitation of independent function. This approach may also be leveraged for training persons to use computerized assistive/rehabilitative interfaces better. Training settings for the user may be coadapted with device settings that promote greater human-machine integration, both functionally and cognitively. Ultimately, perception-based VR rehabilitation may benefit from having a sense of limb dominance due to generally more positive outcomes, e.g., higher relative binding, and higher perception-related performance. As such, facilitating a sense of limb dominance if the non-dominant side may be beneficial to these rehabilitative ends. However, the onus to match perceived device/avatar control closely with user intentions may be amplified for the dominant hand due to greater potential reductions in performance for relatively mismatched cases of control that may distort perceptions, whether they be for time or control. Furthermore, it may be essential to match avatar/device operations to movement ‘targets’ or ‘intentions’, not necessarily actual movements, for clinical participants since their patterns exhibit pathology.

Finally, let us suppose the impaired side is non-dominant, and facilitating dominance is not possible. In that case, there may be more insensitivity to performance reductions due to perceptional changes from varied avatar/device control. It is still an open question how performance gains may persist through perceptional changes, whether based on distortions in time, flow disruptions, or actual agency alterations. However, as observed in this study, perception-based performance outcomes may be plausible, and computerized interfaces may need to consider how these outcomes rely on several factors, including task complexity along with handedness. Desired outcomes include improving absolute performance and enhancing the coupling of perception with performance if leveraging perception is an end-goal in the design of the VR rehabilitation protocol. Further studies on actual clinical participants are necessary to assess the true potential of systematic variations in user control of computerized rehabilitative interfaces on perception-centered gains in performance. Even if time-perception binding is not wholly diagnostic of agency (Haggard, 2017) and is affected by factors of attention, causality, and adaptation, it appears there are potential correlations between measures for performance and perception during computerized rehabilitative-type tasks (e.g., VR reach-to-grasp). Further studies, with more reliable measurement instruments for explicit agency, are warranted to tease out agentic versus time-perception effects in metrics such as binding. Regardless, if control over computerized interfaces for rehabilitation is adapted to maximize perceptions, there may be potential motor learning benefits that accelerate functional outcomes through greater participant engagement.

5. Conclusions

Variations in a virtual hand’s dominant or non-dominant limb control produce significant changes in performance and perception (relative binding) of a reach-to-grasp task. Furthermore, a significant positive correlative relationship between performance and perceptions (binding) was observed for the dominant hand. It remains unclear to what extent binding results in this study reflect actual agency versus sensory-driven distortions in time perception. The presented work serves as a first step to incentivize further investigations into adapting computerized interfaces to leverage perceptional measures for augmenting movement performance optimally. Perception-based motor rehabilitation with VR may better engage participants and accelerate gains in function. A perceptional approach to rehabilitation may be further optimized by adapting training protocols to personalized characteristics such as limb dominance.

Table 1B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance across control modes with dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 1E-08 | 1E-08 | 4E-08 | 1E-08 |

| Slow | – | – | 1E-08 | 1E-08 | 1E-08 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 1E-08 | 0.98 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 3E-04 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 1C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance across control modes with non-dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 1E-10 | 1E-08 | 0.17 | 6E-04 |

| Slow | – | – | 1E-10 | 1E-10 | 1E-10 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 1E-10 | 0.019 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 1E-07 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 2B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance efficiency across control modes with dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 1E-10 | 1E-08 | 1E-10 | 1E-10 |

| Slow | – | – | 1E-10 | 1E-10 | 2E-08 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.78 | 6E-05 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 3E-03 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 2C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance efficiency across control modes with non-dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 1E-10 | 0.089 | 0.98 | 1E-10 |

| Slow | – | – | 1E-10 | 1E-10 | 1E-10 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.27 | 1E-07 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 1E-10 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 3B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for relative binding across control modes with dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 1E-04 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.99 |

| Slow | – | – | 4E-04 | 4E-03 | 4E-04 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.97 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 3C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for relative binding across control modes with non-dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.014 | 0.015 | 2E-03 | 1E-04 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.46 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.97 | 0.45 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.84 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 4B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for explicit agency across control modes with dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.86 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.73 | 0.58 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.99 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 4C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for explicit agency across control modes with non-dominant hand.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.66 | 0.82 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.99 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 5B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.45 | 0.17 | 1E-08 | 1E-05 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.98 | 5E-06 | 4E-03 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 1E-04 | 0.027 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.34 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 5C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for performance efficiency.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.33 | 1E-03 | 5E-08 | 0.037 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.19 | 1E-04 | 0.84 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.084 | 0.76 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 3E-03 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Table 6B.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for relative binding.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.72 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.015 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.011 | 0.014 | 3E-04 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.99 | 0.78 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.74 |

Table 6C.

Post hoc comparisons (p-values) for explicit agency.

| Control mode | Control mode |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Slow | Fast | Noisy | Auto | |

| Baseline | – | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| Slow | – | – | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Fast | – | – | – | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Noisy | – | – | – | – | 0.99 |

Note1: all post hoc comparisons made with Bonferroni correction.

Note2: significant post hoc p-values (<0.05) bolded.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Aniket Shah, who assisted with data collection and management. This work was supported by the Schaefer School of Engineering and Science at the Stevens Institute of Technology and a research grant (PC 53-19) from the New Jersey Health Foundation.

Appendix A

The mean motion trajectories during reach are shown in each of three directions for both the dominant and non-dominant hand in Fig. A.1. There was significant (p < 0.05) difference in motion variability (average standard deviation) during the designated reach period (t = 3–7 s) between dominant and non-dominant hands for the forward-backward and upward-downward directions.

Fig. A.1.

The mean position trajectory for dominant and non-dominant hands in each of three orthogonal directions. Thickness indicates +/− 1 standard deviation about mean trajectory. A paired t-test was performed on the average standard deviation during the designated reach period (shaded area, time = 3–7 s) for each dimension between dominant and non-dominant sides. The average standard deviations for the dominant side in the forward, upward, and rightward directions are 0.0566, 0.0443, and 0.0255 m, respectively. The average standard deviations for the non-dominant side in the forward, upward, and rightward directions are 0.0489, 0.0430, and 0.0269 m, respectively.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

RN – Designing and developing the experiment, data analysis, writing manuscript, revising the manuscript, directing project

SS – Recruiting participants, performing data collections, data analysis, revising the manuscript

ML – Figures for the manuscript, revising the manuscript

NYH – Revising the manuscript

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report for this manuscript.

References

- Adamovich SV, Fluet GG, Mathai A, Qiu Q, Lewis J, & Merians AS (2009). Design of a complex virtual reality simulation to train finger motion for persons with hemiparesis: A proof of concept study. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation, 6(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostini V, & Knaflitz M (2011). An algorithm for the estimation of the signal-to-noise ratio in surface myoelectric signals generated during cyclic movements. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 59(1), 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagesteiro LB, & Sainburg RL (2002). Handedness: Dominant arm advantages in control of limb dynamics. Journal of Neurophysiology, 88(5), 2408–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon LJ (1995). From human factors to human actors: The role of psychology and human-computer interaction studies in system design. In Readings in human–computer interaction (pp. 205–214). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman AL, et al. (2005). Locomotor training progression and outcomes after incomplete spinal cord injury. Physical Therapy, 85(12), 1356–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaya JA, & Herr H (2004). Adaptive control of a variable-impedance ankle-foot orthosis to assist drop-foot gait. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 12(1), 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boakes RA (2021). Performance on learning to associate a stimulus with positive reinforcement. In Operant-Pavlovian interactions (pp. 67–101). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brass M, Bekkering H, & Prinz W (2001). Movement observation affects movement execution in a simple response task. Acta Psychologica, 106(1–2), 3–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum LJ, Varghese R, Stoll H, & Winstein CJ (2020). Predictors of arm nonuse in chronic stroke: A preliminary investigation. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 34(6), 512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JM, & Long J (1991). Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1st. [Google Scholar]

- Caspar EA, Cleeremans A, & Haggard P (2015). The relationship between human agency and embodiment. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressman EK, & Henriques DY (2010). Reach adaptation and proprioceptive recalibration following exposure to misaligned sensory input. Journal of Neurophysiology, 103(4), 1888–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen TG, Dijksterhuis A, & Baaren R. B.v. (2014). On the other hand: nondominant hand use increases sense of agency. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(6), 680–683. [Google Scholar]

- Demanet J, Muhle-Karbe PS, Lynn MT, Blotenberg I, & Brass M (2013). Power to the will: How exerting physical effort boosts the sense of agency. Cognition, 129(3), 574–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer C, Bouchereau M, Jeannerod M, & Franck N (2008). Effect of distorted visual feedback on the sense of agency. Behavioural Neurology, 19(1), 53–57, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris RJ, Quintero HA, Murray SA, Ha KH, Hartigan C, & Goldfarb M (2013). A preliminary assessment of legged mobility provided by a lower limb exoskeleton for persons with paraplegia. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 22(3), 482–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S (2007). Sense of agency and higher-order cognition: Levels of explanation for schizophrenia. Cognitive Semiotics, 1, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gopher D, & Lavie P (1980). Short-term rhythms in the performance of a simple motor task. Journal of Motor Behavior, 12(3), 207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman PA, Gillaspie DM, & Hill LD (1988). Effects of speed and limb dominance on eccentric and concentric Isokinetic testing of the knee. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 10(2), 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]