Abstract

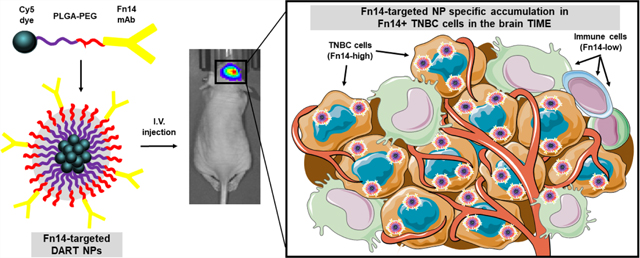

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients with brain metastasis (BM) face dismal prognosis due to the limited therapeutic efficacy of the currently available treatment options. We previously demonstrated that paclitaxel-loaded PLGA−PEG nanoparticles (NPs) directed to the Fn14 receptor, termed “DARTs”, are more efficacious than Abraxane—an FDA-approved paclitaxel nanoformulation—following intravenous delivery in a mouse model of TNBC BM. However, the precise basis for this difference was not investigated. Here, we further examine the utility of the DART drug delivery platform in complementary xenograft and syngeneic TNBC BM models. First, we demonstrated that, in comparison to nontargeted NPs, DART NPs exhibit preferential association with Fn14-positive human and murine TNBC cell lines cultured in vitro. We next identified tumor cells as the predominant source of Fn14 expression in the TNBC BM-immune microenvironment with minimal expression by microglia, infiltrating macrophages, monocytes, or lymphocytes. We then show that despite similar accumulation in brains harboring TNBC tumors, Fn14-targeted DARTs exhibit significant and specific association with Fn14-positive TNBC cells compared to nontargeted NPs or Abraxane. Together, these results indicate that Fn14 expression primarily by tumor cells in TNBC BMs enables selective DART NP delivery to these cells, likely driving the significantly improved therapeutic efficacy observed in our prior work.

Keywords: fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14, triple-negative breast cancer, brain metastases, tumor-immune microenvironment, DART nanoparticles, Abraxane

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of nanoparticles (NPs) as drug delivery vehicles has led to significant improvements in the treatment of cancer patients, resulting in the approval of formulations such as Doxil (liposomal doxorubicin) in 1995 and Abraxane (albuminstabilized paclitaxel NPs) 10 years later. While these and other nanodrug formulations improved drug tolerability and safety, their efficacy at reducing tumor growth improved only marginally compared to conventional drug formulations and administration regimes.1,2 Abraxane, for example, enabled the administration of paclitaxel without using Cremophor EL, an oil-based solvent that causes significant toxicity in patients.3 In addition to solubilizing hydrophobic drugs, Abraxane and other NP formulations take advantage of the characteristically defective and leaky vasculature of tumors for preferential accumulation via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.4,5 However, while such NPs enhance the delivery of chemotherapeutics, they fail to leverage one of the most significant benefits afforded by NP-mediated drug delivery: tumor-specific targeting. Thus, after nearly three decades since the approval of first-generation NPs, there still are no FDA-approved targeted NPs for cancer treatment.

The development of targeted NPs remains especially challenging for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which lacks expression of estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor 2 receptors (ER, PR, and Her2).6 These features render TNBC nonresponsive to hormone treatments or specific therapies currently used to treat other breast cancer subtypes. As a result, patients experience significantly higher rates of recurrence, relapse, and metastasis.7 A recent retrospective study estimated that up to 46% of patients with metastatic TNBC develop brain metastases (BMs),8 with incidence steadily increasing over the past two decades.9−11 Treatment options are limited, as BMs are typically too difficult to remove via surgical resection and radiation therapies have limited survival benefits.12 Further preventing clinical success, the unique architecture of central nervous system tumors can significantly limit the efficacy of systemically administered drugs. The blood−tumor barrier (BTB) can prevent drug accumulation,13−15 while the brain’s densely charged extracellular space can limit convective and diffusive drug transport within the brain parenchyma.16−20 In addition, the glial lymphatic system21 and expression of multidrug resistance pumps within the brain can reduce drug concentrations in the tumor microenvironment22 and intracellularly,23 respectively.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) and its receptor, fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14), are members of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies, respectively, that are primarily involved in repair processes that occur following tissue injury.24 Fn14 expression is low in healthy tissues but upregulated in over a dozen solid tumors, including TNBC tumors and metastases,25,26 and high Fn14 levels have been shown to correlate with advanced tumor stage and poor patient outcomes.24,27−32 Importantly, Fn14 is also significantly overexpressed in BC BMs,33 where it has been identified as the most useful and accurate predictive biomarker of BM in luminal BC subtypes.34 The function of Fn14 in primary or metastatic BC is unclear; however, ectopic expression of Fn14 in TNBC cells stimulates cell migration and invasion, suggesting a potential metastasis-promoting function.35

The combined lack of Fn14 expression in healthy tissues, upregulation of expression in TNBC primary tumors and metastases, and constitutive Fn14 recycling to the cell surface36 makes Fn14 an ideal candidate for targeting therapeutics to BC tumors. Indeed, we previously demonstrated the utility of Fn14-targeted NPs for paclitaxel drug delivery in the TNBC mammary fat pad (MFP) and brain tumor (BT) mouse models of primary TNBC and TNBC BMs, respectively.28 These NPs, which had been formulated specifically for decreased nonspecific adhesivity and receptor targeting, or DART characteristics,37 were crucially shown to outperform Abraxane and nontargeted NPs in enhancing the survival of tumor-bearing mice after a single intravenous treatment. We speculated that Fn14-targeted DART NP therapeutic efficacy in these models was due to a combination of prolonged systemic circulation, enhanced tumor accumulation, and extended tissue penetration and drug release. However, this study did not address the Fn14 cellular expression pattern within the tumor microenvironment or the targeting thereof with Fn14-directed DART NPs. Indeed, neither the specific targeting of Fn14-positive cells nor nonspecific uptake of Fn14-targeted DART NPs by phagocytes (i.e., passive targeting) present within tumors has been investigated following systemic administration.

The brain tumor (BT) microenvironment is composed of tissue-resident cells and a large proportion of recruited immune cells that, in the case of BC, can constitute up to 50% of the tumor mass.38 Our group recently reported that glioblastoma tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) express Fn14 through analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data.27 Fn14 expression has also been detected in human monocyte cell lines,39 peritoneal macrophages, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells.40 These findings suggest that Fn14-targeted DART NPs may associate with Fn14-positive non-neoplastic cells in the tumor-immune microenvironment (TIME). Indeed, if Fn14 is expressed by immune cells with antitumor activity, then Fn14-targeted, drug-loaded DART NPs would eliminate these cells, an undesirable outcome. Conversely, considering the progressively immunosuppressive nature of TAMs in TNBC BM,41 eliminating Fn14-positive tumor-supporting immune cells would be a beneficial effect of Fn14-targeted therapeutic NP delivery. Regardless of Fn14 expression, however, TAMs and other phagocytes present within the TIME are thought to be passively targeted by NPs.42 While most studies demonstrating passive TAM NP accumulation have been investigated in extracranial BC tumor models,43−45 we have yet to determine if Fn14-targeted DART NPs exhibit significant nonspecific uptake by these populations in TNBC BTs.

Regardless of nonspecific uptake, NP formulations are subject to protein corona formation (i.e., surface adsorption of serum proteins46) following systemic administration, which has been shown to eliminate molecular targeting of some nanotherapeutics.47 While the significantly enhanced efficacy of Fn14-targeted DART NPs noted in our prior study28 implies retention of targeting capability, it remains possible that this is mediated by specific targeting of Fn14-expressing immunosuppressive immune cells, passive targeting of these cells, or by other factors such as prolonged circulation or differential drug release as noted above. Therefore, a better understanding of Fn14 expression in the TNBC brain TIME and whether Fn14-targeted DART NPs can successfully bind Fn14-positive cells within tumors following systemic administration will help understand the reported efficacy and future utility of Fn14-targeted NPs. In this study, we assess Fn14 expression in the TIME of two complementary animal models of TNBC BMs and compare the clearance, biodistribution, and cellular targeting of Fn14-targeted NPs, nontargeted NPs, and Abraxane.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials.

Methoxy-terminated PLGA−PEG (10:5 kDa), PLGA−PEG with maleimide end group (PLGA−PEG-Mal, 10:5 kDa), and PLGA-Cyanine 5 (PLGA-Cy5, 30−55 kDa) were purchased from PolySciTech. ITEM4 was provided by Dr. Hideo Yagita (Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan), and mouse IgG isotype control antibody (10400C) was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. PVA (25 kDa) was purchased from Polysciences. PD-10 Desalting Columns were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. SulfoCyanine 5 (sulfo-Cy5) NHS ester, an amine-reactive red-emitting fluorescent dye, was purchased from Abcam (ab146459) for Abraxane labeling. PLGA (7−17 kDa, 50:50), dichloromethane (DCM), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2-iminothiolane hydrochloride, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used without further purification. Clinical-grade Abraxane was purchased from the University of Maryland Medical Center Outpatient Pharmacy. Antibodies for flow cytometry include CD45-eF450 (30-F11, eBioscience 48–0481-82), CD11b-PE-Cy7 (M1/70, Biolegend 101216), Ly6G-Alexa Fluor 700 (1A8, Biolegend 127621), Ly6C-PE (HK1.4, Biolegend 128007), Luciferase-Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam epr17790), Fn14-APC (Biolegend 314108), and IgG-APC (Biolegend 400322). Zombie Aqua (Biolegend 423102) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and used to stain cells at a final concentration of 1:50.

2.2. Preparation of Cy5-Labeled Polymeric Nanoparticles.

Cy5-labeled maleimide-terminated PLGA−PEG nanoparticles were synthesized using a single emulsion solvent evaporation technique. Briefly, the polymers, including poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-Cy5 (PLGA-Cy5), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)−polyethylene glycol (PEG), and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)−polyethylene glycol maleimide (PLGA−PEG-mal), were dissolved in 2 mL of dichloromethane to form an organic/oil phase. The prepared oil phase was added to 12 mL of 5% w/v PVA solution in water to form an oil-in-water emulsion. All of the emulsions were sonicated in an ice bath using an ultrasonication probe at 40% amplitude for 3 min with 20 s on−off pulses. The sonicated emulsions were stirred at room temperature for 4 h to allow vaporization of organic solvent, followed by microcentrifugation at 50,000g for 40 min to pellet the formulated nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were washed with ultrapure water and collected by centrifugation (three washes in total) to remove any unreacted polymers and byproducts. The purified nanoparticles were resuspended in ultrapure water, followed by antibody conjugation.

2.3. Antibody Conjugation to PLGA−PEG Nanoparticles.

The thiol-modified ITEM4 and IgG antibodies were prepared by the reaction of free amines with 2-iminothiolane, as described previously.28 Briefly, the antibodies were mixed with 2-iminothiolane (140× molar excess) in 100 mM phosphate buffer with EDTA (pH 7.2; 150 mM NaCl and 5 mM EDTA) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The thiolated antibody solution was purified with Zeba Spin Columns [7 kDa molecular weight (MW) cutoff] and frozen immediately until needed for further use. The antibody-conjugated Cy5-PLGA−PEG nanoparticles were prepared by mixing maleimide functionalized PLGA−PEG nanoparticles with thiol-modified antibody via maleimide−thiol chemistry. For this, the unconjugated NPs were mixed with thiol-modified ITEM4-SH or IgG-SH solution (1.2× excess SH to maleimide) in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2; 150 mM NaCl) and allowed to react overnight at 4 °C. After the reaction, nanoparticles were purified from unconjugated antibodies via microcentrifugation at 21,100g for 30 min with ultrapure water (three washes in total). The nanoparticles were resuspended and used fresh for experiments.

2.4. Physicochemical Characterization of Cy5-Labeled Nanoformulations.

The physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles were measured in 15× diluted PBS (∼10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) at 25 °C. The hydrodynamic diameter and ζ-potential were determined by dynamic light scattering and laser Doppler anemometry, respectively, using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Southborough, MA). Particle size measurement was performed at 25 °C at a scattering angle of 173° and is reported as the number-average mean. The ζ-potential values were calculated using the Smoluchowski equation and are reported as the mean zeta potential.

2.5. Surface Plasmon Resonance Analysis of Cy5-Labeled Nanoparticle Binding to Fn14.

The specific interaction of ITEM4 and IgG conjugated nanoparticles with the recombinant Fn14 extracellular domain (Cell Sciences) was analyzed using a high-throughput SPR-based Biacore 3000 instrument (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C, as previously described.16,28,48 Briefly, the Fn14 extracellular domain was diluted in acetate buffer (pH 4.0) and conjugated to a CM5 Biacore chip with a response unit (RU) value of ∼1700. The first flow path (Fc1) was activated and blocked with ethanolamine to serve as a reference cell. For binding experiments, the nanoparticle samples were diluted in 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 50 μM EDTA (HBS-N) used as running buffer. The samples were assayed at a flow rate of 20 μL/min with an injection time of 3 min, followed by a 2.5 min wait for dissociation before the chip was regenerated with 10 mM glycine (pH 1.75). Data were analyzed using Biacore 3000 Evaluation Software, where data from Fc1 were subtracted from the Fc2 data to give the final sensograms. In addition, binding isotherms for the nanoparticle were generated by analyzing the kinetic binding of nanoparticles to the Fn14 chip at serially diluted nanoparticle concentrations. The data were analyzed by fitting to a pseudo-first-order process to determine the maximum change in RUs (RUeq). RUeq values were then plotted versus nanoparticle concentrations. The equilibrium binding affinity (KD) was calculated by fitting the binding isotherm data into a single class of binding sites using nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 7.03 software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

2.6. Cell Culture.

Human MDA-MD-231-TD-luciferase (“231-TD-luc”) TNBC cells were provided by Dr. Stuart Martin (University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM)).49 Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen 16140071), 1% penicillin−streptomycin (1000 units/L, Invitrogen 15140122), 0.25 mg/ mL G418 sulfate (Gemini Bio 400–113), and 0.5 mg/mL hygromycin B (Corning 30–240-CR). Murine 66.1 TNBC cells were provided by Dr. Amy Fulton (UMSOM).50 They were transduced with purified lentiviral particles encoding firefly luciferase (GeneCopoeia Inc., Rockville, Maryland) to generate the 66.1-luc cell line and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin−streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (95% air, 5% CO2).

2.7. Evaluation of Fn14 Expression in TNBC Cell Lines and Mouse Tissues.

Total and surface expression of Fn14 was determined via Western blotting and flow cytometry, respectively. For cell line Western blot analysis, cells were detached with trypsin and lysed in RIPA (Sigma R0278) supplemented with a protease and phosphate inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific 1861281). The protein concentration of each lysate was determined by the BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific 23227). For mouse tissue Western blot analysis, tissues (kidneys, liver, spleen) or brains harboring tumors were isolated, mechanically disrupted, and homogenized with sonication in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged to pellet debris, and the protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen NP0342BOX) and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes (Thermo Scientific 88518). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM) in TBST buffer and then sequentially incubated with either an anti-Fn14 antibody (Abcam EPR3179) or an anti-glyceraldehyde-3-dehydrogenase (GAPDH, CST 2218S) antibody. Following washing in TBST (CST 9997S), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (CST) was added to the membranes. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using the Amersham Enhanced Chemiluminescence Plus kit (Cytiva RPN2232) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For flow cytometry, cells were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, cells were blocked with Mouse Trustain Fcx (Biolegend 101320) for 15 min and then incubated with: no antibody, IgG isotype-APC, or ITEM4-APC in FACS Buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 2.5 mM EDTA) for 30 min on ice. Cells were then washed three times with FACS buffer, detached with trypsin, and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Invitrogen 28906) for 10 min. Data was acquired on a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer and assessed for APC median fluorescence intensity after gating to exclude dying cells and debris.

2.8. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Nanoparticle Uptake In Vitro.

Cellular uptake of Cy5-labeled nanoparticles by cells in vitro was quantified via flow cytometry. Briefly, cells (100,000 per well) were seeded in 12-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, cells were washed once with 1× PBS and the media was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% mouse serum and penicillin−streptomycin containing 5, 25, 50, 100, or 200 μg/mL of NPs for 15−120 min at 37°. Cells were washed three times with 1× PBS, detached with trypsin, and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The median fluorescence intensity of Cy5 was analyzed using a Cytek Aurora spectral cytometer. For endocytosis inhibition studies, cells were treated with 25 μg/mL of NPs for 30 min at 37 or 4 °C. To block the Fn14-mediated endocytosis, receptor cells were pretreated with excess IT4 (200 μg/mL) for 30 min before NP treatment. Cells were then washed and analyzed via flow cytometry, as above.

2.9. Intracranial Injection of TNBC Cell Lines.

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the Office of Animal Welfare Assurance (OAWA). Athymic nude and BALB/cByJ (“BALB/c”) female mice (age 6−8 weeks) were purchased from Taconic and the Jackson Laboratory, respectively. Animals were anesthetized via the continuous flow of 2−3% isoflurane through a nose cone and secured to a stereotactic frame. Using a handheld drill, a burr hole was drilled into the brain’s left frontal lobe, approximately 2 mm lateral and 1 mm anterior to Bregma. A Hamilton syringe attached to the stereotactic frame was used to inject 5 × 105 MDA-MB-231-TD-luc cells or 2 × 105 66.1-luc cells in 5 μL at a rate of 1 μL/min over 5 min at a depth of 3 mm below the dura. Mice were subcutaneously administered Rimadyl (Carprofen, 3mg/kg) after the surgery and observed daily for neurological dysfunction or signs of distress.

2.10. In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging and Quantification of Tumor Burden.

Intracranial tumor growth was monitored via bioluminescence imaging. Briefly, animals were anesthetized in an induction chamber with 2.5% isoflurane and intraperitoneally injected with Pierce D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg, dissolved in PBS) (ThermoFisher Cat# 88293). After 10 min, animals were moved to a Xenogen IVIS system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) maintained at 2.5% isoflurane and imaged for tumor bioluminescence. Photons emitted from live mice were acquired as photons/s/cm2/steradian (p/s/cm2/sr). The average radiance (p/s/cm2/sr) within identical regions of interest drawn around the brain was used to quantify tumor burden using Living Image software (PerkinElmer, MA).

2.11. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Dissociated Intracranial Tumors.

Mice harboring BTs were anesthetized, sacrificed, and subjected to transcardial perfusion with ice-cold PBS. BTs were placed in complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Lonza Group), and tissue was mechanically disrupted on a 70 μm filter and resuspended in RPMI containing DNase (10 mg/mL; Roche, Mannheim, Germany), Collagenase/Dispase (1 mg/mL; Roche), Papain (25 U; Worthington Biochemical), and EDTA for enzymatic digestion at 37 °C while shaking (200rpm) for 1 h. Tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was discarded. Cells were resuspended in 70% Percoll and underlaid in 30% Percoll. The gradient was centrifuged at 500g for 20 min at 4 °C. Myelin was removed by aspiration, and cells at the interface were collected to enrich leukocyte populations. Cells were centrifuged and blocked with mouse Fc block prior to staining with primary antibody-conjugated fluorophores and Zombie Aqua viability dye (see Materials). Cells were washed three times with 1× PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 8 min at room temperature. Data was acquired on a Cytek spectral cytometer using SpectroFlo and analyzed using FCS Express 7 software. Events were sequentially gated to exclude debris and clumps of cells/doublets. All cell population gates were set using fluorescence minus one (FMO) staining controls for all of the fluorophores used. A standardized gating strategy was used to identify tumor cells (for 231-TD, CD45−/GFP+; for 66.1-luc, CD45−/ luciferase+), monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G−), neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C-Ly6G+), tumor-associated macrophages (CD45+CD11b+Ly6C-Ly6G−), and putative lymphocytes (CD45+CD11b−). Within the macrophage population, resident microglia were further identified as a CD45 intermediate, whereas bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were identified as CD45-high. The Zombie Aqua Live/Dead dye was used to assess cell death in individual populations and to exclude dead cells from analysis. Populations with an insufficient number of gated cells were excluded from the analysis. Additional details of quantification analyses from individual experiments are available in the figure legends.

2.12. Tumor Pathology and Immunohistochemistry Analyses.

Animals were euthanized with induction of general anesthesia followed by exsanguination using transcardiac perfusion of cold PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde. Whole brains were rapidly extracted and fixed in 4% formalin for 24 h and transferred to 70% ethanol before embedding in paraffin. H&E staining and IHC analysis for Fn14 expression (1:200 dilution of Fn14 antibody ab109365, Abcam) were conducted by NDB Bio, LLC (Baltimore, MD) as follows. Fixed tissues were mounted in paraffin blocks using the Leica EG 1160 embedding center (Leica Microsystems) and then sectioned into 5 μm slices. For IHC, antigen retrieval was performed using either Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 1 (pH ∼6) or Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 (pH ∼9) (Leica Microsystems) at 99−100 °C for 20−32 min. IHC staining was performed on a Leica BOND-III autostainer (Leica Microsystems), and a peroxidase/DAB Bond Polymer Refine Detection System (Leica Microsystems) was used for Fn14 detection.

2.13. Preparation of Cy5-Labeled Abraxane.

Clinical-grade Abraxane was labeled using the sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester, amine-reactive red-emitting fluorescent dye from Abcam (ab146459). Briefly, Abraxane was dissolved in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.12) to a concentration of 24 mg/mL (800 μL) and 19 μL of sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester dye (2 mg/mL in water) was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark while rotating for 90 min. Following incubation, Cy5-labeled Abraxane was then loaded onto a PD-10 column to separate the free dye from the conjugate. Abraxane integrity before and after conjugation was confirmed using dynamic light scattering to measure the hydrodynamic diameter and the polydispersity index. Absorbance readings of the conjugate were used to calculate the dye/protein molar ratio as the manufacturer’s instructions suggested, using the molar extinction coefficients of 38,553 M−1 cm−1 at 643 nm for Cy5 dye and 250,000 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm for human serum albumin. This preparation consistently yielded a dye/protein molar ratio of 0.03.

2.14. Dosing and Normalization of Cy5-Labeled Nanoparticles and Abraxane.

The concentration of Abraxane in the Cy5-Abraxane conjugate was quantified from the absorbance of an Abraxane standard curve measured at 280 nm and injected at a final dose of 5 mg/mL of Abraxane (total injected dose = 1 mg/mouse of Abraxane; 0.1 mg/mouse of paclitaxel, ∼4 mg/kg PTX). Absorbance readings at 643 nm were used to calculate the amount of Cy5 dye in the conjugate, Cy5-PP-IgG, and Cy5-PP-IT4 (Fn14-targeted DART NPs) using the molar extinction coefficients of 38,553 M−1cm−1. Cy5-PP NPs were then diluted to the equivalent concentration of Cy5 in prepared 5 mg/mL Cy5-Abraxane and injected at a final dose of 5.8 and 5.75 mg/mL for Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, respectively (total injected dose = 1.16 mg/mouse and 1.15 mg/mouse for Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG, respectively). Normalization of particles was confirmed via subsequent absorbance readings at 643 nm.

2.15. Intravenous Injection and Imaging of Cy5-Labeled Nanoparticles or Abraxane.

Individual mice were restrained briefly in a Tailveiner apparatus (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA), and the tail was then subjected to 70% ethanol scrub. For circulation and tumor studies, Cy5-labeled PLGA−PEG nanoparticles or Cy5-Abraxane were injected in a final volume of 200 μL via a tail vein catheter at the doses indicated above. At designated time points up to 96 h, mice were anesthetized as previously described and a fluorescence signal was detected using the Xenogen IVIS system. Identical imaging acquisition settings (time, 2 sec; ex/em, 640/680; F-stop, 2; binning, medium) and the same area of regions of interest (ROI) drawn around animals were used to obtain total radiance (photons/sec/cm2/sr). An untreated mouse was imaged alongside treated mice at each time point for background discrimination. Images were processed using Living Image (PerkinElmer) software to calculate the percentage relative fluorescence intensities against time to estimate the half-life of NPs. For ex vivo tissue biodistribution analysis, mice were euthanized with induction of general anesthesia followed by cervical dislocation. Tissues were isolated, weighed, placed on a sterile 100 mm tissue culture dish, and imaged using the Xenogen IVIS system for fluorescence using identical acquisition settings (time, 2 s; ex/em, 640/680; F-stop, 2; binning, medium). Identical ROIs were used to quantify the fluorescence signal from individual tissues measured as the tissue total radiance (photons/sec/cm2/sr) and expressed as a percent of the injected dose (% ID) obtained from the in vivo Cy5 total radiant efficiency of the respective mouse imaged after 30 min. The % ID was then normalized to tissue weight. (% ID/mg).

2.16. Flow Cytometric Analysis of NP Cellular Targeting in Dissociated Intracranial Tumors.

Mice were treated with Cy5-labeled NPs as described above. After 24 h, mice were euthanized with induction of general anesthesia followed by cervical dislocation. The entire left hemisphere of the brain harboring the tumor was isolated, processed, and stained with immunophenotypic markers for flow cytometric analysis as described above.

2.17. Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis of data was performed by the unpaired Student’s t test, one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple test adjustment using the FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg using GraphPad software. Additional details pertaining to specific statistical analyses performed can be found in the figure legends. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at a level of P < 0.05 after multiple test adjustments.

RESULTS

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Cy5-Labeled Nanoparticles.

Fluorescently labeled poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-Cyanine-5(Cy5)-polyethylene glycol (PEG) nanoparticles (NPs) were synthesized via a single emulsion method as previously described.28,37 Cy5-PLGA−PEG (Cy5-PP) NPs were then conjugated via maleimide−thiol chemistry to ITEM4 (IT4, Cy5-PP-IT4) or murine immunoglobulin (IgG, Cy5-PP-IgG). These NPs were formulated using a single emulsion solvent evaporation technique with 10% PEG and 1% antibody surface densities (Supporting Table 1) as optimized in our previous study for minimal nonspecific binding to serum proteins and extracellular matrix (ECM).28 NP physiochemical characterization by dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed that both Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NPs maintain sub-100 nm size with a relatively monodisperse size distribution and have a slightly negative surface charge (Table 1), comparable to the paclitaxel-loaded NPs used in our previous efficacy studies.28 Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs (i.e., Fn14-targeted DART NPs) were marginally larger (∼95 vs ∼90 nm), more neutral (−2.19 vs −4.11 mV), and more uniformly distributed (0.10 vs 0.19) than Cy5-PP-IgG NPs (i.e., nontargeted NPs).

Table 1.

Physicochemical Properties of Cy5-Labeled Nanoformulations and Unlabeled Abraxane

| formulation | hydrodynamic diameter (nm)a | ζ-potential (mV)b | PDIc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy5-PP-IT4 | 95.47 ± 3.20 | −2.19 ± 0.68 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| Cy5-PP-IgG | 90.25 ± 3.32 | −4.11 ± 0.37 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| Cy5- Abraxaned |

163.40 ± 1.11 | −8.39 ± 1.22 | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| Abraxaned | 131.20 ± 0.76 | −14.73 ± 1.23 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

Hydrodynamic diameter measured by dynamic light scattering. Data represent the average of three independent experiments +/− SD.

Surface charge measured at 25 °C in 15× diluted PBS with ∼10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Data represent the average of three independent experiments +/− SD.

Polydispersity index (PDI) indicates the distribution of individual molecular masses in NP batches. Measured by dynamic light scattering. Data represent the average of three independent experiments +/− SD.

Contains 10% (w/v) paclitaxel.

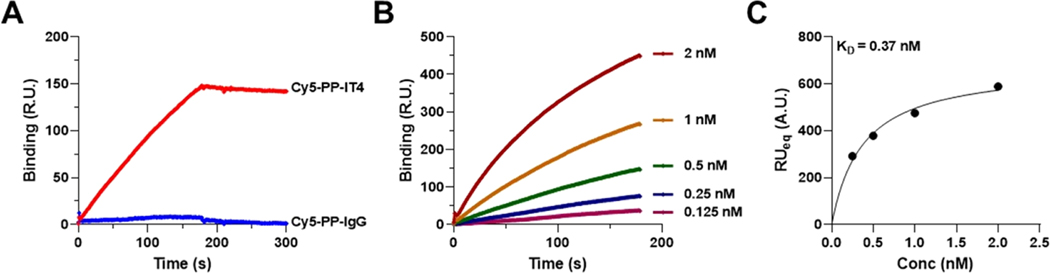

To test if Cy5 conjugation had a detrimental effect on the ability of PP-IT4 NPs to bind Fn14, we examined the binding of Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NPs to a Fn14-coated CM5 Biacore chip via the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay.37 We observed that Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, but not Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, exhibited strong Fn14 binding (Figure 1A). Kinetic binding analysis with different Cy5-PP-IT4 NP concentrations revealed that binding increased proportionally to the NP concentration used (Figure 1B). We then used this binding data to quantify Cy5-PP-IT4 NP:Fn14 binding affinity and calculated a dissociation constant (KD) of 0.37 nM (Figure 1C), which is similar to the KD we reported for nonfluorescent PP-IT4 NPs.28 Together, these data indicated that Cy5 modification of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs does not alter their binding to immobilized Fn14.

Figure 1.

Specific binding of Cy5-labeled Fn14-targeted and nontargeted PGLA nanoformulations to the Fn14-coated sensor chip. (A) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding of 0.5 nM Cy5-PP-IT4 or Cy5-PP-IgG NPs to the Fn14-coated Biacore chip. (B) SPR binding analysis of various concentrations of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs to the Fn14-coated Biacore chip. (C) The binding isotherms of the Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs shown in B were used to determine the dissociation constant (KD). Data was fit by nonlinear regression using GraphPad analysis software.

We also labeled clinical-grade Abraxane with an amine-reactive sulfo-Cy5 NHS ester, followed by isolation of Cy5-Abraxane from free Cy5 dye by size exclusion chromatography. Analysis of labeled and unlabeled Abraxane physiochemical properties showed that the addition of Cy5 increases the nanoformulation size from ∼131 to ∼163 nm (Table 1). Cy5 labeling also increased Abraxane polydispersity (0.15−0.20) and surface charge (−14.7 to −8.3 mV), the latter of which may be explained by masking of surface albumin, which is negatively charged at physiologic pH (isoelectric point ∼4.9).51 The conjugation procedure consistently yielded a dye/protein molar ratio of 0.03, indicating that approximately one Cy5 molecule was attached to 3 out of 100 albumin molecules in the labeled formulation. At this molar ratio, in which 97 of every 100 albumin molecules remains unlabeled, Cy5 labeling is not likely to change Abraxane biological activity or pharmacokinetics.52

3.2. Fn14 Cell Surface Expression Enables Preferential Fn14-Targeted DART NP Association with TNBC Cell Lines In Vitro.

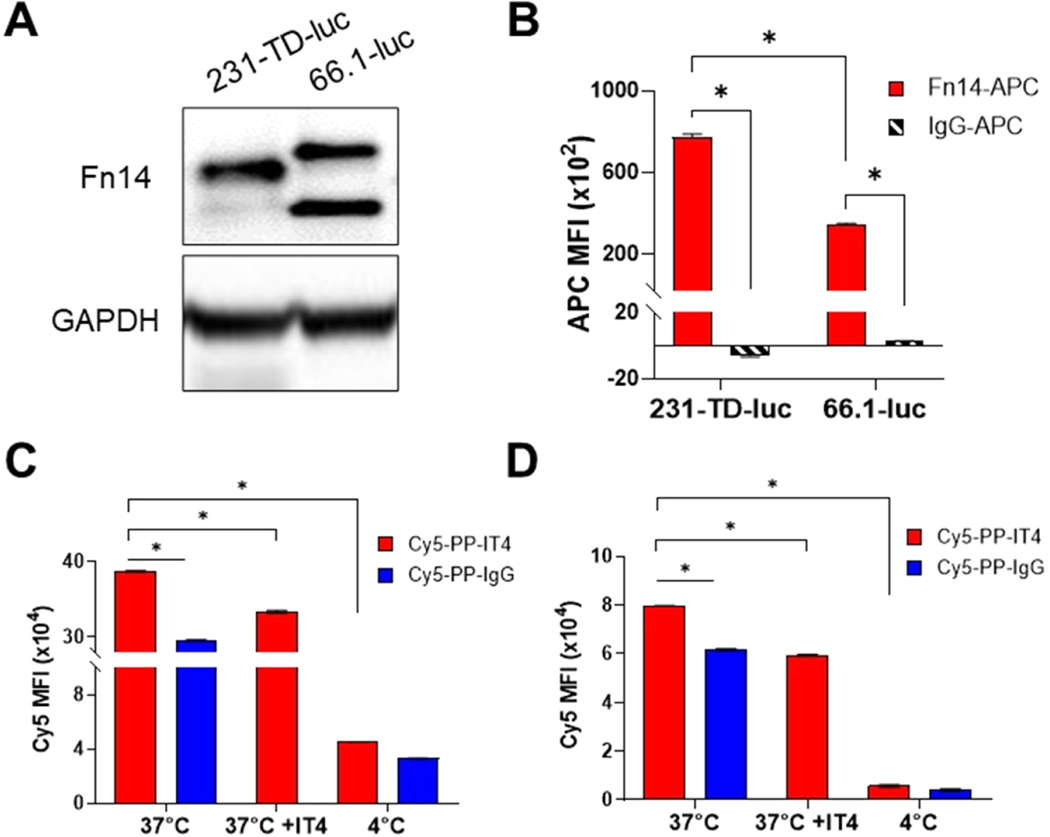

Fn14 expression in the murine and human TNBC cell lines selected for these studies was investigated via Western blotting and flow cytometry. MDA-MB-231-TD-luc (231-TD-luc) is a tumor-derived (“TD”) variant of the well-studied MDA-MB-231 TNBC cell line used in our previous efficacy studies28 that exhibits high metastatic potential.49 The 66.1-luc cells are murine TNBC cells syngeneic with BALB/c mice.53 Fn14 protein expression was detected in both cell lines by Western blot analysis (Figure 2A). Full-length murine Fn14 runs at a slightly higher molecular weight than human Fn14 on SDS-PAGE gels (∼16 and ∼15 kDa for 66.1-luc and 231-TD-luc, respectively). Also, the 66.1-luc cells express a lower molecular weight form of Fn14 (∼12.5 kDa), which likely represents an Fn14 mRNA splice variant-derived isoform missing the extracellular domain.54,55 This isoform is also expressed at lower levels by 231-TD-luc cells. Flow cytometry was used to confirm that Fn14 was present on the cell surface of both cell lines, with significantly more Fn14 detected in 231-TD-luc cells compared to 66.1-luc cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Fn14 is expressed by the TNBC cell lines used in the intracranial tumor growth models and enables preferential uptake of targeted NPs by these cells in vitro. (A) Human 231-TD-luc and murine 66.1–1uc cells were harvested, lysates were prepared, and Fn14 and GAPDH levels were assayed via SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of surface Fn14 expression by TNBC cell lines was performed. The cells were stained with an Fn14 antibody (red) or isotype control IgG (black striped), and expression was quantified as the APC median fluorescence intensity (MFI) after subtraction of unstained cells. (C, D) Flow cytometric analysis of Cy5-PP-IT4 (red) and Cy5-PP-IgG NP (blue) uptake in 231-TD-luc (C) and 66.1-luc (D) cells in vitro. Cells were treated with 25 μg/mL NPs for 30 min either at 37 °C, 4 °C, or after a 30 min preincubation with 200 μg/mL ITEM4 (IT4) at 37 °C. Cells were washed, and NP uptake was quantified from the Cy5 MFI following background subtraction of untreated cells. Values shown are mean ± SD (n = 3). Data was analyzed for significance using 2-way ANOVA with the follow-up FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg for multiple comparisons, *p < 0.0001.

We then measured the cellular association of Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NPs via flow cytometry. We performed these studies in the presence of 10% mouse serum in the culture media to mimic protein corona formation after systemic NP delivery in mice. First, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of NPs for 30 min, which revealed dose-dependent uptake of both NP types (Figure S1A,C). Next, we treated cells with a fixed concentration of NPs (25 μg/mL) for increasing incubation times, which demonstrated time-dependent uptake of both particle types in the two cell lines (Figure S1B,D), though uptake in the 231-TD-luc cells appears to begin plateauing upon treatment for 90 min. There is significantly more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake than Cy5-PP-IgG uptake in all of the treatment conditions except when treating 66.1-luc cells with 5 μg/mL of NPs for 30 min or when treating 231-TD-luc cells with 25 μg/mL of NPs for 10 min. Finally, Cy5-PP-IT4 NP targeting efficiency (Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake/Cy5-PP-IgG NP uptake) is higher in 231-TD-luc cells (∼1.3-fold more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake) compared to 66.1-luc cells (1.1-fold more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake), consistent with the increased expression of fulllength Fn14 by 231-TD-luc cells (Figure 2B).

To confirm that increased Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake is mediated by the Fn14 receptor, we pretreated cells with excess IT4 antibody and then added the Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs. We found significantly decreased NP uptake in IT4 pretreated cells compared to cells without pretreatment (Figure 2C,D). Finally, NP treatment of both cell lines at 4 °C, which blocks all active endocytic processes, dramatically reduced both Cy5-PP-IgG and Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake, indicating that cellular uptake of both NP types occurs via energy-dependent endocytosis mechanisms (Figure 2C,D).

3.3. Fn14 Is Primarily Expressed by TNBC Cells in Both Intracranial Growth Models.

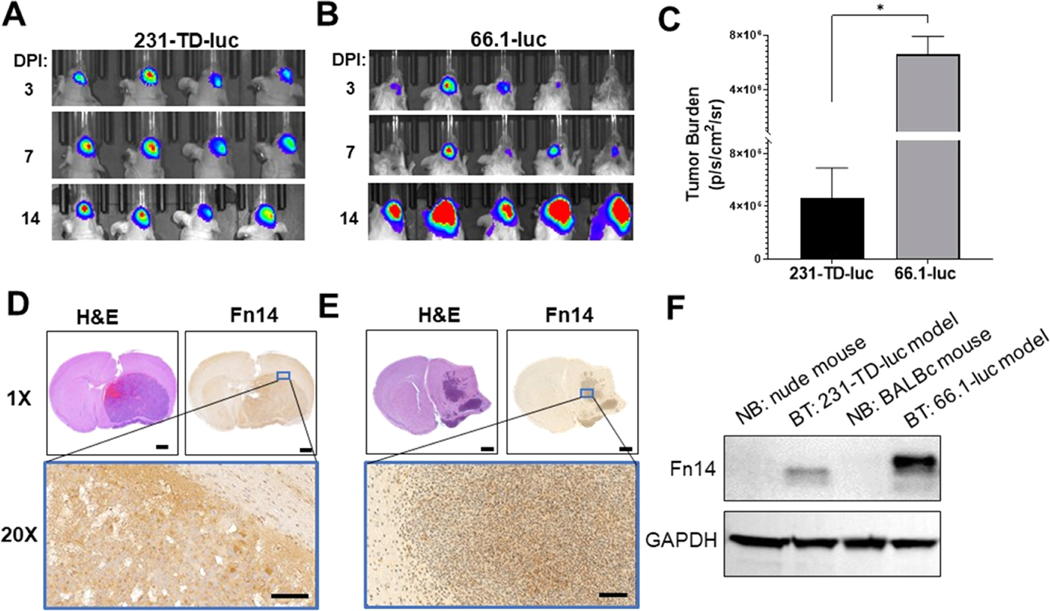

Both TNBC cell lines formed BTs upon intracranial implantation. Analysis of tumor growth via bioluminescence imaging (Figure 3A,B) revealed that 231-TD-luc cells form smaller BTs with over 14-fold lower tumor burden than 66.1-luc cells after 14 days of growth despite inoculation of more cells (Figure 3C). Histopathological analysis of these tumors revealed distinct tumor growth patterns in the two models: 231-TD-luc BTs grow as a single mass (Figure 3D), while 66.1-luc BTs exhibit more infiltrative growth with multiple foci (Figure 3E), which more accurately resembles human BMs. Finally, we examined Fn14 expression in isolated normal brain tissue and intracranial tumor tissue by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 3D,E) and Western blot analysis (Figure 3F) and found Fn14 was only expressed in the tumor samples.

Figure 3.

Analysis of 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc intracranial tumor growth, tumor histology, and the Fn14 expression level in isolated tumor tissues. Bioluminescence imaging of 231-TD-luc (A) or 66.1-luc (B) tumor growth in the brain of nude and BALB/c mice, respectively, at the indicated days post-inoculation (DPI). (C) Quantification of 231-TD-luc or 66.1-luc tumor burden in (A), (B) at 14 DPI, determined by measuring the average radiance within identical regions of interest (ROIs) around the tumors. Error bars show +SEM of results from at least 4 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired Student’s t test, *p ≤ 0.005. (D, E) H&E and Fn14 immunohistochemical staining of brain sections from mice harboring 231-TD-luc (D) or 66.1-luc (E) tumors. Staining of the region within the blue box is shown at 20× magnification. Scale bars: 1 mm (1×) and 100 μm (20×). (F) Analysis of Fn14 expression in normal brains (NB) or brain tumors (BT). The indicated tissues were harvested 14 DPI, lysed, and Fn14 and GAPDH levels were examined via Western blot analysis.

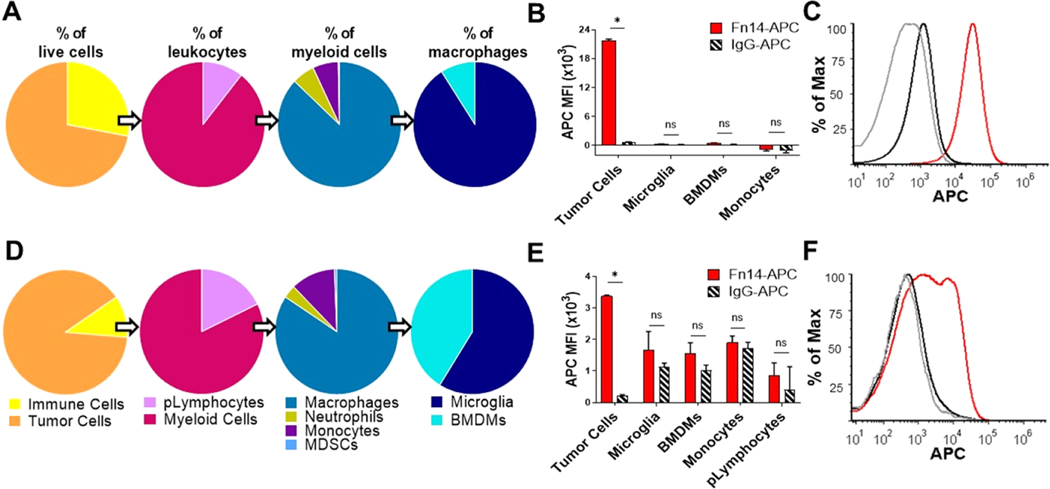

To analyze the tumor-immune microenvironment (TIME) of these tumors, which can significantly influence NP accumulation in vivo,56 we dissociated the right brain hemispheres harboring tumors and stained them with a panel of immunophenotypic antibodies (Supporting Table 2) to identify major immune cell populations (Figure S2). Tumor cells accounted for over 66% of the live cells analyzed in both models, with a higher proportion of tumor cells in the 66.1-luc BM model (Figure 4A,D). CD45+ cells lacking CD11b expression were identified as putative lymphocytes (pLymphocytes) and included T and B lymphocytes.57 pLymphocytes constitute a larger proportion of immune cells in 66.1-luc BTs, as expected, as athymic nude mice lack functional T cells. Despite being the most abundant leukocyte in healthy adults,58 neutrophils accounted for less than 5% of the myeloid cells in these BTs (Figure 4A,B). Likewise, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which are a heterogenous population of immature innate immune cells that are broadly identified as Ly6C and Ly6G-expressing myeloid cells,59 are rare in these intracranial tumors (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Tumor cells are the predominant source of Fn14 expression in the tumor-immune microenvironment of both the xenograft and syngeneic mouse models of TNBC growth in the brain. Flow cytometric analysis of dissociated brains harboring 231-TD-luc (A−C) or 66.1-luc (D−F) tumors. (A, D) Pie charts show the frequency of respective populations calculated from the total number of live cells within each gated population divided by the total number of cells in the parent populations. (B, E) Quantification of Fn14 surface expression compared to isotype control (IgG) in gated cell populations of tumor cells, microglia, bone marrow-derived macrophages (DMs), monocytes, and putative lymphocytes (pLymphocytes). Data is quantified as the APC median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the indicated populations after subtraction of the respective signal from fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls. (C, F) Representative histogram of tumor cell population flow data showing staining with anti-Fn14 (red), isotype IgG (black), or FMO control (gray). Data is representative of three independently performed experiments. Error bars show +SEM of results from 4 mice. Statistical analyses were done using the unpaired Student’s t test. *p ≤ 0.005, ns: nonsignificant.

Macrophages are mononuclear phagocytes that play a critical role in both normal homeostasis and in tumor progression,60 and account for over 80% of the myeloid cells in these BTs (Figure 4A,D). Within the brain, two distinct macrophage populations exist based on their origin and can be distinguished by their relative level of CD45 expression: infiltrating bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs, CD45-hi) and tissue-resident microglia (CD45 intermediate).61 Microglia account for the majority of macrophages in both BM models, though a significantly larger population of infiltrating BMDMs was observed in dissociated 66.1-luc BTs compared to 231-TD-luc BTs (Figure 4A,D). Monocytes, which are circulating immature myeloid cells that differentiate into macrophages within tissues,59 represent a large frequency of myeloid cells in 66.1-luc BTs (Figure 4A,D) and thus likely contribute to the increased accumulation of BMDMs.

To examine Fn14 expression levels in TIME cells, dissociated BTs were stained with a Fn14 antibody or control IgG and flow cytometry was performed. We detected minimal Fn14 expression by microglia and BMDMs, as well as other immune populations, in both 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc BTs, as evidenced by the similar level of Fn14 antibody and isotype control staining (Figure 4B,E). On the contrary, high levels of Fn14 were detected in the tumor cell compartment in both BT models, with higher Fn14 expression observed by 231-TD-luc cells (Figure 4B,C) compared to 66.1-luc cells (Figure 4E,F). This data suggests that the elevated Fn14 expression level in 66.1-luc BTs (Figure 3F) is driven by the increased number of tumor cells within this model, which express less Fn14 per cell than 231-TD-luc.

3.4. Fn14-Targeted DART NPs Are Not Rapidly Cleared, Do Not Promote Mouse Weight Loss, and, in Contrast to Abraxane, Do Not Accumulate in Mouse Lungs Following Systemic Administration.

Prior to assessing the tissue and cellular biodistribution of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, and Abraxane in mice harboring TNBC BTs, we first investigated NP clearance and biodistribution after intravenous delivery into tumor-naïve, immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Measurement of the whole-body NP signal over time was used to compare the clearance of polymeric NPs or Abraxane. Whole-body fluorescence was increased 4 h after treatment with each formulation, likely due to circulation in the bloodstream, and then gradually decreased over time (Figure S3A). Follow-up analysis of curves fit with nonlinear regression reveals similar clearance kinetics between Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, which differed significantly from Cy5-Abraxane, as would be expected due to structural and physiochemical differences (Table 1) between the polymeric NPs and Abraxane.62 After 24 h, there was significantly more Cy5-Abraxane signal compared to Cy5-PP NPs, but after 72 h, there was significantly more Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs compared to the other two formulations remaining in the mice. We also estimated the half-life of these three nanoformulations (i.e., the time required for 50% clearance). Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, and Cy5-Abraxane had half-lives of ∼30, ∼39, and ∼43 h, respectively, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure S3B). We also confirmed that neither the dose of Cy5-Abraxane (∼4 mg/kg paclitaxel) nor the two Cy5-labeled polymeric NP formulations (no drug) induced overt toxicity in mice during the course of this experiment, as monitored by body weight measurements (Figure S3C).

To assess the biodistribution of NPs in these same mice, we removed the major organs 96 h after NP administration and performed ex vivo imaging, which confirmed that all three formulations were still detectable in mice 4 days after treatment (Figure S3D). Both Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs and nontargeted NPs are primarily present in the liver and spleen, as would be expected due to the known clearance of ∼100 nm diameter NPs from the blood by the mononuclear phagocyte system.62 In comparison, Cy5-Abraxane was detected in the liver, kidneys, and lungs.

3.5. Systemically Administered Fn14-Targeted DART NPs Accumulate to Similar Levels as Nontargeted NPs and Abraxane in Brains Harboring TNBC Tumors.

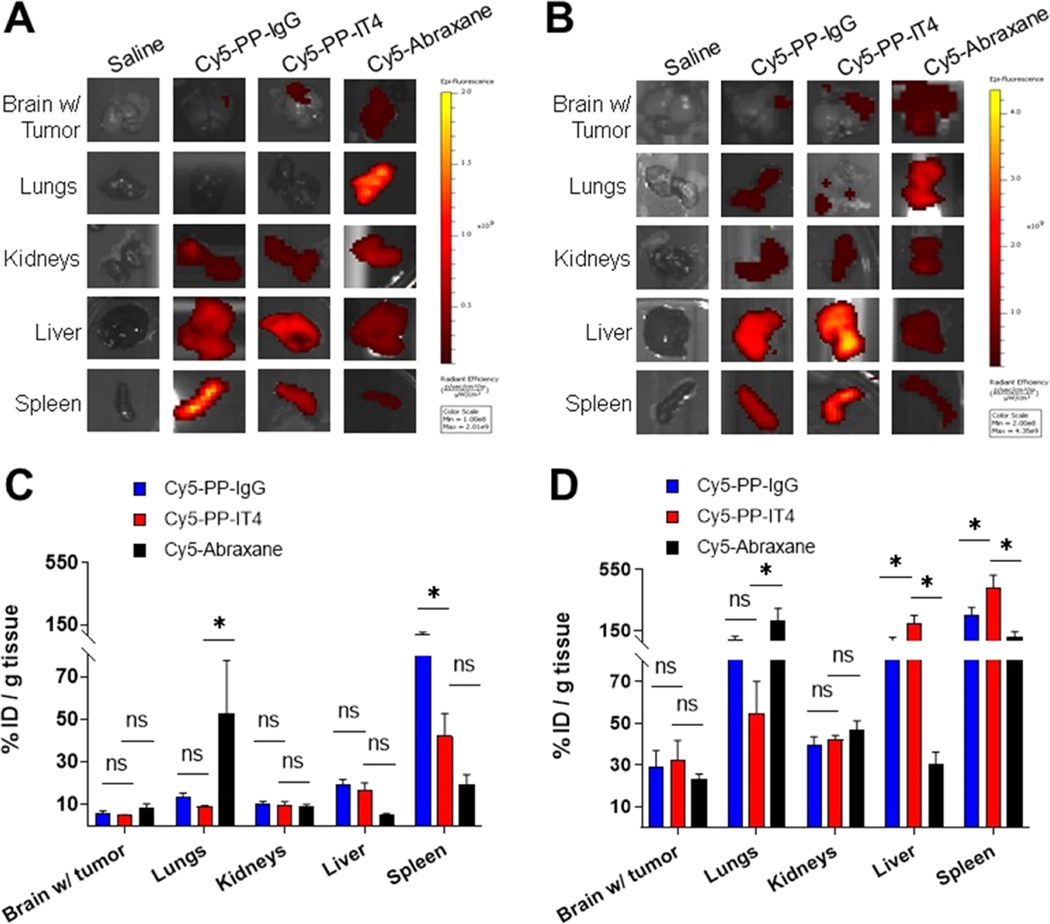

We next assessed the biodistribution of systemically administered Cy5-labeled nanoformulations in BT-harboring mice 14 days after tumor inoculation. Whole-body fluorescence imaging was used to monitor NP distribution at 0.5 1, 4, and 24 h post-delivery (HPD) (Figure S4), but to better quantify biodistribution, brain tissue (containing both normal brain and BT), as well as four normal organs exhibiting NP accumulation in healthy mice (Figure S3D), were harvested 24 h after NP injection and NP accumulation quantified via ex vivo fluorescence imaging. In both models, the Cy5-Abraxane signal was detected throughout the brain, whereas Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, and to a lesser extent Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, exhibited more localized BT signals within the right frontal hemisphere (Figure 5A,B). As expected based on our previous studies,28 both Cy5-PP NPs exhibited the most accumulation in the spleen of nude mice, with significantly more Cy5-PP-IgG NP accumulation (Figure 5C). There was also significantly more Cy5-PP NP accumulation in the liver and kidneys than Cy5-Abraxane, whereas Cy5-Abraxane exhibited the highest proportional accumulation in the lungs.

Figure 5.

Fn14 targeting does not increase NP accumulation in brains harboring TNBC tumors at 24 h. Cy5-labeled NP ex vivo biodistribution in nude (A, C) and BALB/c (B, D) mice harboring 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc intracranial tumors, respectively, at 24 h after intravenous injection. (A, B) Representative ex vivo imaging of NP biodistribution quantified in (C), (D). (C, D) Cy5-labeled NP tissue accumulation expressed as a percent of the respective Cy5 injected dose (%ID) and normalized to tissue weight. Error bars show +SEM of results from at least 4 mice. Asterisks show significant differences between Cy5-PP-IT4 and other groups using 2-way ANOVA and the FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg for correction of multiple comparisons, *p < 0.01, ns: nonsignificant.

Nude mice are hairless and, thus, with equal fluorescence acquisition parameters, have a higher in vivo NP signal than BALB/c mice. As NP biodistribution is quantified as a percent of the in vivo signal (% initial dose) of the respective mouse, we see a less normalized accumulation of all of the NPs in all of the tissues isolated from the nude mice. Still, in the syngeneic BALB/c model, there was 2.7-, 4.8-, and 6.6-fold more Cy5-Abraxane, Cy5-PP-IgG NP, and Cy5-PP-IT4 NP brain (with tumor) accumulation, respectively, (Figure 5D) than in the xenograft model (Figure 5C). Here, there was a trend of more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation in brains harboring 66.1-luc BTs, but the difference did not achieve statistical significance in comparison to Cy5-PP-IgG NPs or Cy5-Abraxane. We attribute the trend of more Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs in this model to the increased total Fn14 expression by these tumors (Figure 3F). Interestingly, there was also significantly more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation in the liver and spleen of these mice, and slightly elevated accumulation in the kidneys, in comparison to Cy5-PP-IgG NPs. However, Western blot analysis of these organs did not detect Fn14 expression, suggesting nonspecific accumulation in these clearance organs (Figure S5). Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, but not Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, exhibited an increase in the NP signal throughout the body beginning at 4 HPD (Figure S4B), which was absent in tumor-naïve mice (Figure S3A). We therefore speculate that the comparatively higher Cy5-PP-IT4 NP spleen and liver accumulation may be due to persistence of Cy5-PP-IgG in the blood. Cy5-Abraxane in BALB/c mice harboring 66.1-luc BTs again exhibited the most significant accumulation in the lungs; however, it also showed substantial accumulation in the spleen (Figure 5B,D).

3.6. Fn14-Targeted DART NPs Exhibit Specific and Significant Targeting of Fn14-Positive TNBC Cells within the Brain TIME.

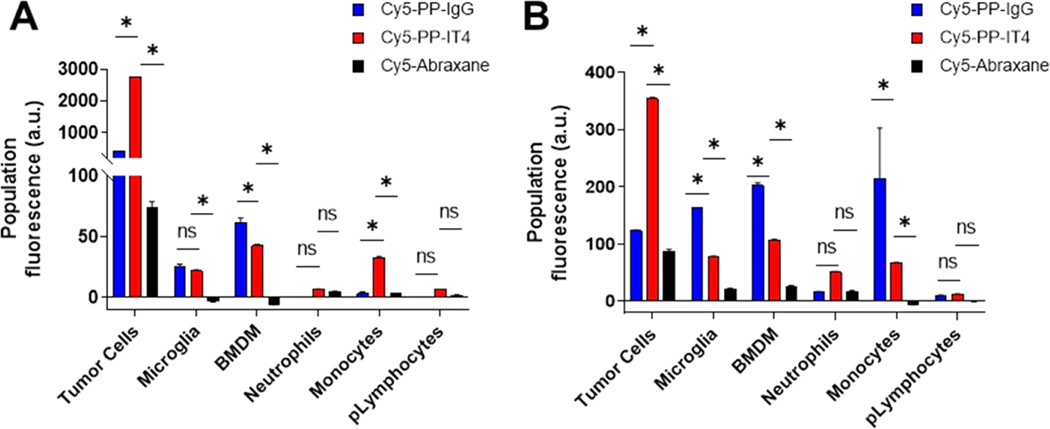

After observing that all three Cy5-labeled NP formulations can be detected in 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc tumor-harboring brain tissue after systemic delivery, we next sought to quantify the cellular distribution of these formulations in the TIME. Right cerebral hemispheres harboring BTs were harvested 24 HPD and dissociated into single-cell suspensions for analysis via flow cytometry. We chose this time point to complement tissue targeting studies and also in light of studies showing that cellular internalization of PEGylated PLA NPs within the brain is significantly increased by 24 HPD compared to 4 HPD.63 We quantified NP cellular tropism in two ways: (i) we measured the Cy5 median fluorescence intensity (MFI) after subtraction of the background signal from saline-treated mice which reflects the amount of NP uptake per celland normalized this to the relative abundance of that cell population within dissociated BTs to represent the total population fluorescence (Figure 6) and (ii) we measured the percentage of cells within each population positively associating with NPs (Figure S6).63

Figure 6.

Fn14 targeting enables significant and specific targeting of Fn14-positive tumor cells in the TIME of xenograft and immunocompetent models of TNBC BM. Flow cytometric analysis of NP cellular targeting in dissociated 231-TD-luc (A) and 66.1-luc (B) BTs 24 h after systemic administration of Cy5-labeled NPs or normal saline. (A, B) The Cy5 median fluorescence intensity of the indicated live populations from saline-treated mice was subtracted from the respective populations in NP-treated mice and then multiplied by the relative number of cells in each population to derive the population fluorescence (arbitrary units, au). Populations with an insufficient number of gated events were excluded from analyses. Error bars show +SEM of results from at least 3 mice. *p ≤ 0.05, ns: nonsignificant. Asterisks show significant differences between Cy5-PP-IT4 and other groups using 2-way ANOVA and the FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg for correction of multiple comparisons.

Analysis of the total Cy5 signal of each population revealed significant, specific targeting of Fn14-positive tumor cells with Cy5-PP-IT4 NP treatment in both models (Figure 6) and significantly less Cy5-PP-IgG NP and Cy5-Abraxane accumulation in these same cells. Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs exhibited 6.2- and 2.9-fold more accumulation than Cy5-PP-IgG NP within the tumor cell compartment of 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc BTs, respectively. Furthermore, a comparison between the two models demonstrates that Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation within the tumor population is ∼7.8-fold higher in the 231-TD-luc model compared to the 66.1-luc model (Figure 6), despite 231-TD-luc cells accounting for a lower proportion of cells within these BTs (Figure 4). This corresponds to their relative Fn14 expression levels in vivo, where 231-TD-luc cells express ∼6.4-fold more surface Fn14 than 66.1-luc (Figure 4). Additional analysis on the fate of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs alone reveals a similar pattern of distribution among immune populations within the two models, with BMDM and lymphocyte populations exhibiting the most and least targeted NP accumulation, respectively, in BTs (Figure 6). Cy5-PP-IgG NP TIME distribution varied considerably between the two models.

In addition to assessing the relative targeting of each population, we also sought to determine the percentage of cells within each population that associates with NPs (Figure S6). Interestingly, these analyses revealed that <10% of the tumor cells in both models had taken up Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, which was still significantly greater than that of nontargeted NPs (1.6−3.1 and 0.1−0.3% for Cy5-PP-IgG and Cy5-Abraxane, respectively). Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs associated with 6.8 and 8.3% of 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc tumor cells, respectively.

Phagocytic populations, including microglia, BMDMs, neutrophils, and monocytes, despite minimal Fn14 expression, showed the greatest fractional NP association regardless of targeting (Figure S6D,E). Indeed, ∼19 and 28% of BMDMs, ∼17 and 18% of monocytes, and ∼9 and 12% of neutrophils positively associate with Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs in 231-TD-luc and 66.1-luc BTs, respectively. Interestingly, 20% of microglia in 66.1-luc BTs but just 2% in 231-TD-luc BTs are associated with Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs. The increased percentage of all populations associated with Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs compared to nontargeted NPs in 66.1-luc BTs, but not 231-TD-luc BTs, suggest that this is maybe due to the slightly increased, yet insignificant, Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation in 66.1-luc BTs compared to the nontargeted formulations (Figure 5B). Lymphocyte populations showed the lowest fractional NP association, with less than 3% of these cells positively associating with any NP type. Upon Cy5-PP-IgG NP treatment, a surprising and significant proportion of infiltrating BMDMs (∼34%) was associated with these NPs in 231-TD-luc tumors, over double that observed in 66.1-luc BTs (∼15%). Given that mice in both models were administered identical doses of Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, this is likely due to the decreased frequency of BMDMs in 231-TD-luc BTs (Figure 4), which may enable a larger percentage of the population to be targeted.

As a whole, Cy5-Abraxane was associated with significantly fewer populations (Figure 6) and dramatically lower percentages of cells (Figure S6) in both models compared to polymeric formulations. The Cy5-Abraxane injected dose was 40% of the therapeutic dose used in previous studies,28 but to confirm that the apparent lack of Cy5-Abraxane cellular targeting was not the result of paclitaxel-mediated cell death, we also quantified the percentage of nonviable cells within each population that associated with NPs (Figure S7), which did not reveal more cell death as a result of Cy5-Abraxane treatment. In addition, increased tumor cell death was also not observed in mice treated with Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs.

4. DISCUSSION

In this work, we examined the utility of targeting the Fn14 receptor for nanotherapeutic drug delivery in two complementary models of the final stage of TNBC BM—cell growth in the brain. We prepared three Cy5-labeled nanoformulations and, after demonstrating that Cy5 labeling did not alter Cy5-PP-IT4 NP physiochemical characteristics or reduce Fn14 binding, investigated the properties of this formulation in comparison to nontargeted polymeric NPs and Abraxane, an FDA-approved nanoformulation used for metastatic BC patients. Specifically, we identified two Fn14-positive TNBC cell lines that form large intracranial tumors after stereotactic injection, allowing us to study NP association with tumor tissue, tumor cells, and tumor-associated immune cells after systemic delivery.

We first formulated Cy5-labeled NPs and demonstrated that Cy5 labeling does not interfere with the binding of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs to immobilized Fn14 via SPR (Figure 1). NP targeting capability following systemic administration is complicated by the formation of protein coronas upon exposure to serum proteins, which has been shown to significantly decrease or eliminate molecular targeting of some formulations in vivo.47 We therefore sought to confirm that Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs retained targeting capability in the presence of a protein corona by measuring NP uptake by human and murine TNBC cells in media supplemented with 10% mouse serum. We found that Fn14-targeted NPs retain targeting capability under these conditions and demonstrated that this uptake was mediated by Fn14 (Figure 2C,D). While these results suggest Fn14 receptor-mediated endocytosis to be a major Cy5-PP-IT4 NP cellular uptake mechanism, a much more dramatic reduction in NP uptake was observed upon inhibition of all active endocytic processes at 4 °C, suggesting that additional energy-dependent mechanisms may be driving Cy5-PP-IT4 and Cy5-PP-IgG NP uptake. Indeed, protein coronas are known to regulate NP cellular internalization pathways,64,65 and we have previously used quantitative proteomic analyses to identify more than 200 different proteins present on the surface of PLGA−PEG NPs following blood serum incubation.66 In this previous study, albumin, serotransferrin, and α−2-macroglobulin were the most abundant proteins adsorbed to NP surfaces, likely mediating additional endocytic uptake processes of both formulations. Nonetheless, the elevated Cy5-PP-IT4 NP uptake relative to nontargeted NP uptake by 231-TD-luc versus 66.1-luc cells (Figures S1 and 2C,D) corresponded well to the higher levels of Fn14 surface expression by 231-TD-luc (Figure 2B), further suggesting that targeting of the receptor mediates Cy5-PP-IT4 NP preferential uptake.

To further study Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs in the presence of endogenous protein coronas, we utilized complementary xenograft and syngeneic TNBC BM models. Bioluminescence imaging (Figure 3A−C) and histopathological analyses (Figure 3D,E) revealed differences in tumor burden and growth patterns between the two models, both of which expressed Fn14 (Figure 3D−F). Recent data demonstrating Fn14 expression by macrophages within human glioma tumors27 prompted us to further examine Fn14 expression in the tumor-immune microenvironment (TIME) of our TNBC BTs, which varied in immune cell frequency (Figure 4A,D). We found minimal Fn14 expression by macrophages or other immune cells within TNBC BTs (Figure 4B,E), further underscoring the utility of Fn14 expression as a tumor cell-specific portal for targeted drug delivery. Neutrophils and MDSCs in both models and pLymphocytes in 231-TD-luc BTs were excluded due to an insufficient number of gated cells for proper analysis, but nonetheless, we did not detect a significant difference in Fn14 and isotype control staining in these rarer populations (data not shown). Finally, the 231-TD-luc TNBC cells expressed more Fn14 than the 66.1-luc cells (Figure 4C,F), suggesting that the increased Fn14 expression in 66.1-luc BTs (Figure 3F) is due to the increased number of tumor cells (Figure 3C) within these tumors compared to 231-TD-luc tumors.

We next studied the three Cy5-labeled nanoformulations in vivo after systemic administration using tumor-naïve immunocompetent mice, which revealed similar clearance kinetics (Figure S3A,B). Importantly, a comparison of NP biodistribution in major organs 96 h after administration did not reveal aberrant accumulation of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs in non-clearance organs, whereas Cy5-Abraxane exhibited significant accumulation in the lungs (Figure S3D). This was anticipated by the >150 nm diameter of Cy5-Abraxane,62 but it has also been reported by others to occur with unlabeled Abraxane,67 underscoring the potential for this formulation to induce offtarget respiratory system effects.68 Indeed, drug-induced lung injury upon Abraxane administration in humans is not rare69 and may be avoided with paclitaxel delivery via polymeric NP formulations like our DART NPs. These studies were also conducted in tumor-naïve immunodeficient nude mice, which yielded similar results (data not shown). In consideration of our prior study demonstrating increased efficacy of paclitaxel-loaded Fn14-targeted DART NPs compared to Abraxane in a human TNBC BM model,28 we next compared the biodistribution of Cy5-labeled NPs to Cy5-labeled Abraxane 24 h after systemic administration into mice harboring BTs (Figure S4). We found that Fn14 targeting did not increase NP accumulation in brains that contained TNBC tumors in comparison to either of the nontargeted formulations (Figure 5). Kim et al. reported a similar finding in MMTV-neu models of Her2+ BC, in which Her2-targeted liposomes exhibited similar tumor accumulation as nontargeted liposomes despite significant differences in tumor cell accumulation.70 Nonetheless, there are four considerations that are important to note in light of our tissue accumulation findings. First, NP accumulation was measured in whole brains harboring BTs, as opposed to isolated BTs, which may have reduced our ability to detect tumor-targeting differences via the measurement of fluorescence signal intensities. Indeed, while Cy5-Abraxane was detected more broadly distributed throughout the brain (Figure 5A,B), Cy5PP-IT4 NPs, and to a lesser degree Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, were detected more localized with the tumors in the right frontal hemisphere. As Fn14 is not expressed in normal brain cells (Figure 3F),71 this may be indicative of Fn14-specific BT NP accumulation. Second, we only studied NP accumulation at 24 h post-delivery (HPD). We selected this time point based on the sufficient signal after 24 h in the clearance study (Figure S3A) and to complement previous data examining NP accumulation in 231-TD-luc tumors implanted above the MFP of nude mice 24 HPD.28 While we did report significantly more Fn14-targeted NP accumulation within MFP tumors in that study, the NP signal was not normalized to tissue weight and thus is not directly comparable to our BT findings. It is plausible, however, that 231-TD-luc MFP tumors express more Fn14 than 231-TD-luc BTs, enabling improved tumor accumulation. Nonetheless, differences in NP accumulation in both the xenograft and syngeneic BM models may be diminished by EPR-mediated accumulation of nontargeted NPs at this time point and this warrants investigation of biodistribution at earlier time points.

A third consideration regards direct intracranial tumor cell inoculation for modeling BMs, which was selected to extend our previous report demonstrating the efficacy of Fn14-targeted, paclitaxel-loaded NPs in a similar model.28 While these BTs do adequately reflect the final stage of TNBC metastasis macrometastasis outgrowthintracranial injection has been shown to affect NP BTB penetration.72 As BTB permeability remains a critical hurdle for all BT-targeting therapeutics, evaluation of Fn14-targeted NP BTB penetration was beyond the scope of this study but is warranted in future investigations. In this context, it should be noted that MRI findings have shown that BTB permeability, which is considered to be slightly more permissive than an intact blood−brain barrier,15,73,74 is extremely heterogeneous in preclinical BM models15,75 and human patients.13,15,74,76,77 A final consideration regarding our tissue accumulation findings is the potential differences in BT vasculature, lymphatic drainage, and immune status between the xenograft and syngeneic models. Differences in vascularization between the models may influence passive NP accumulation via the EPR effect62 and can play differential roles in modulating NP accumulation. Additionally, given the differences in the patterns of NP distribution between the models, we cannot exclude the likelihood that the differences in immune status between the two models influence NP biodistribution. Indeed, others have demonstrated that immune status dictates targeted NP tumor retention more so than target expression itself and that immunocompetent mice exhibit the most pronounced differences in targeted versus nontargeted NP accumulation,56 which is consistent with our findings.

While Fn14 targeting did not result in significantly more tumor accumulation, we found that Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs (i.e., Fn14-directed DART NPs) are capable of selectively associating with Fn14-positive tumor cells in the BT microenvironment, despite the presence of an endogenous protein corona. We quantified cellular tropism in two ways, demonstrating that although Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs associated with only ∼7 to 8% of the tumor cells in the microenvironment (Figure S6), quantification of population fluorescence by adjusting for the frequency of cells within the tumors demonstrates that these cells exhibit the largest relative accumulation of these NPs (Figure 6). This fractional association was similar in both models despite differences in Fn14 expression (Figure 4) and tumor burden (Figure 3), suggesting that subsets of tumor cells, likely those in closest proximity to blood vessels, are more able to associate with NPs.

In consideration of reports that TAMs are passively targeted due to their phagocytic activity,43−45,63 we also sought to investigate whether these and other phagocytic immune populations act as a nonselective sink for Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation within the brain TIME. Analysis of the total population fluorescence revealed that the tumor cell compartment exhibited significantly greater Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation than all phagocytic populations (Figure 6). However, there was significantly more passive accumulation of polymeric NPs compared to Cy5-Abraxane (Figures 6 and S6). Infiltrating BMDMs in both models exhibited more Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation than microglia despite representing a smaller population frequency (Figure 4A,D), which has been reported with iron oxide NPs in models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)78 and with lipid nanocapsules in immune cells freshly isolated from human glioblastoma patients.79 We also observed increased uptake by BMDMs versus microglia with Cy5-PP-IgG NPs, suggesting that BMDMs are more susceptible to passive polymeric NP targeting, which may contribute favorably to enhanced efficacy. Nonetheless, the increased total (Figure 6) and fractional (Figure S6) association of Cy5-PP-IgG versus Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs by both of these TAM populations suggests that the lack of targeting to tumor cells results in concomitant increased accumulation of Cy5-PP-IgG NPs in TAMs.

While there are several targeted nanotherapeutics for BC BMs in preclinical development,41 studies employing flow cytometric or single-cell quantification of tumor cell NP targeting within TNBC BTs are lacking. However, similar studies performed 24 h after systemic administration in other tumor models reveal that our Fn14-targeting strategy may enable more preferential tumor cell targeting than other targeted nanotherapeutics. For example, Dai et al. reported that Her2-targeted gold NPs associate with <1% of tumor cells compared to ∼13% of tumor-associated macrophages in subcutaneous models of ovarian cancer.43 In NOD-SCID mice harboring MMTV-neu tumors, Her2-targeted liposomal NP uptake by tumor cells was ∼1.7 to 3.4-fold higher than nontargeted uptake,70 which was comparable to our targeting efficiency. We attribute the successful localization of Fn14-targeted NPs within the neoplastic compartment to the high Fn14 expression by these cells and to previous optimization of NP surface IT4 and PEG densities,28 the latter of which simultaneously improves tumor penetration16 and reduces protein corona formation to minimize masking of NP targeting moieties.80

In comparison to Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, we observed significantly less tumor cell targeting upon treatment with Cy5-PP-IgG NPs or Cy5-Abraxane, confirming that Fn14 targeting successfully enables tumor cell-specific uptake in these models. The selection of Cy5-PP-IgG NPs as nontargeted control NPs was based, in part, on the recognition that Fc regions of antibodies can nonspecifically bind Fc receptors. Fc regions within IgG antibody isotypes, including the IT4 monoclonal antibody, bind Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) primarily expressed by immune cells and are also reported to be expressed by TNBC cells.81 While the use of IgG-functionalized NPs, therefore, affirms that increased Cy5-PP-IT4 NP accumulation in Fn14-positive tumor cells is mediated by specificity for Fn14 and not Fc-mediated interactions, the differential targeting of BMDMs by Cy5-PP-IgG observed in the two models suggest that these control NPs behave differently based on differences in mouse strain or perhaps inflammatory milieu. Indeed, the effector functions of IgG antibodies are largely dependent on the type of FcγR bound, which in turn is affected by the inflammatory cues.82 Nonetheless, the fractional association of nontargeted NPs within tumor cell populations (1.6−3.1%) was similar to that observed with nontargeted PEGylated polymeric NPs following systemic administration in mouse models of melanoma.83

It is also worth noting that, particularly upon Cy5-PP-IgG NP administration, there were some shifts in the immune populations present 24 HPD of NPs, as has been reported to occur with systemic NP administration.84 While the purpose of this study was to use Cy5 labeling to determine the cellular localization of PP NPs without inducing drug-induced cellular toxicity, investigations into changes in the TIME following systemic administration of drug-loaded NPs are warranted yet beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, we did note that Cy5-PP-IgG NP treatment corresponded with increased BMDM infiltration in the 231-TD-luc model (data not shown) and is a potential explanation for the increased percentage of these cells positively associating with control Cy5-PP-IgG NPs (Figure S6D). It is also worth mentioning that, in both models, pLymphocyte fractions increased following Cy5-PP-IT4 NP treatment (data not shown), which has been reported to occur in extracranial BC models following iron oxide NP treatment,56 but further studies are necessary to address this potential immunomodulatory effect of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs, why this was not observed upon Cy5-PP-IgG NP treatment, and whether this occurs with drug-loaded, Fn14-targeted DART NPs.

We did not detect tumor cell death after treatment with the three nanoformulations, including the paclitaxel-loaded Abraxane. The lack of increased tumor cell death upon Cy5-PP-IT4 NP treatment suggests that the antitumor activity induced by Fn14-targeted DART NPs in our previous report28 is likely not mediated by Fn14-mediated apoptotic signaling as has been reported with other Fn14 antibodies or elicitation of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.85,86

The similar degree of Cy5-Abraxane BT accumulation (Figure 5) but decreased association with all cell types (Figures 6 and S6) as compared to Cy5-PP NPs suggests that Cy5-Abraxane may not traverse through the brain interstitium or tumor ECM as efficiently as our optimized polymeric NPs. Indeed, we have previously shown that Abraxane exhibits strong nonspecific binding to tumor ECM components,16 whereas PP NPs were engineered for decreased interactions with ECM proteins. Additionally, Cy5-PP NPs are smaller in size than Cy5-Abraxane (Table 1), which likely enables deeper tumor penetration away from the vasculature.87 Furthermore, Abraxane has been hypothesized to bind gp60 albumin receptors on endothelial cells and use the endogenous transport of albumin to enter tumors,3,88 and despite recent evidence challenging this theory,89 this nonetheless raises the possibility that Cy5-Abraxane may accumulate in other cells within BTs.

There are a few general limitations regarding this study that should be noted. First, as mentioned above, we employed direct intracranial injections to model BM, which bypasses the initial steps of this complicated process. This experimental approach is still suitable for modeling TNBC cells growing in the brain90 and allowed us to draw conclusions from our previous efficacy studies using such models, but additional investigation into Fn14 expression and the targeting thereof is warranted in spontaneous and/or experimental metastasis models that fully recapitulate TNBC metastatic spread through the bloodstream. A second study limitation worth noting is that our flow cytometry antibody panel was designed to only identify major immune populations within the brain TIME (Figure S2).41 Thus, while our results did not indicate significant Fn14 expression in any nontumor cell population, further analysis of Fn14 expression in nonimmune populations (endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes) and in additional immune system cell types (NK cells, dendritic cells)59 is necessary to fully define Fn14 expression not only in TNBC BM models, but also in human tumors. Finally, our characterization of Cy5-Abraxane and unlabeled Abraxane revealed slight differences in physiochemical properties upon Cy5 labeling, which may modulate tissue/cell distribution in vivo.

It is frequently emphasized that few NP delivery systems have succeeded past clinical trials,62 and the limited translational success of these therapeutics is often attributed to the relatively small fraction of systemically administered NPs reaching the tumor site.43,87 Indeed, while this is valid, perhaps more emphasis on the cellular distribution of NPs accumulating within tumors is needed. Given the comparable levels of Fn14-targeted and nontargeted NP accumulation within TNBC BTs, our data suggest that selective drug delivery specifically to the neoplastic compartment is at least partially responsible for the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Fn14-targeted DART NPs compared to nontargeted NPs and Abraxane we observed in our prior study.28

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we formulated Cy5-labeled DARTs (Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs), nontargeted NPs, and Abraxane and demonstrated preferential cellular uptake of Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs by two Fn14-expressing TNBC cell lines in vitro. Using these TNBC cells to develop complementary xenograft and immunocompetent TNBC models of BM, we found that tumor cells are the predominant source of Fn14 expression in BT TIMEs, with minimal Fn14 expression by microglia, infiltrating macrophages, monocytes, and pLymphocytes. Following systemic administration, we found that Fn14 targeting of polymeric NPs does not significantly alter the clearance rate in tumor-naïve mice or improve TNBC BT accumulation compared to nontargeted polymeric NPs or Abraxane. However, analysis of dissociated TNBC BTs revealed significant, specific targeting of DARTs to Fn14-positive tumor cells in both models, suggesting that specific tumor cell delivery drives the efficacy of Fn14-targeted DART drug delivery.

Supplementary Material

■. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (R37 CA212617 and R01 NS107813) and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (I01 BX004908). We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Stuart S. Martin and Dr. Amy Fulton for providing the cell lines used in these studies.

■. ABBREVIATIONS USED

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophage

- BM

brain metastasis

- BT

brain tumor

- BTB

blood−tumor barrier

- BC

breast cancer

- Cy5

cyanine-5

- DART

decreased nonspecific adhesivity, receptor-targeted

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Fn14

fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14

- IT4

ITEM-4

- luc

luciferase

- MFP

mammary fat pad

- 231-TD-luc

MDA-MB-231-TD-luciferase

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MFI

median fluorescence intensity

- NP

nanoparticles

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PLGA

poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- PLGA−PEG

PP, putative lymphocytes, pLymphocytes

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TWEAK

TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- TAMs

tumor-associated macrophages

- TD

tumor-derived

- TIME

tumor-immune microenvironment

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00663.

Cy5-PP-IT4 NPs exhibit dose and time-dependent cellular uptake in Fn14-positive TNBC cells (Figure S1); 1nanoparticle synthesis by emulsion solvent evaporation method (Table S1); cell markers used to identify populations of interest (Table S2); representative gating strategy for flow cytometric analysis of dissociated intracranial tumors (Figure S2); Fn14 targeting does not increase the clearance rate, induce toxicity, or promote NP accumulation in non-clearance organs following systemic delivery in tumor-naïve BALB/c mice (Figure S3); whole-body IVIS imaging shows localization of Cy5-labeled nanoformulations in TNBC BTs following systemic administration (Figure S4); analysis of Fn14 expression in the liver and spleen of tumor-harboring BALB/c mice (Figure S5); cellular distribution of nanoformulations after systemic delivery in mice harboring TNBC tumors in the brain (Figure S6); systemic administration of nanoformulations does not promote cell death (Figure S7) (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00663

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Christine P. Carney, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States; Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States

Anshika Kapur, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States; Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21201, United States.