Abstract

BRD4 is associated with a variety of human diseases, including breast cancer. The crucial roles of amino-terminal bromodomains (BDs) of BRD4 in binding with acetylated histones to regulate oncogene expression make them promising drug targets. However, adverse events impede the development of the BD inhibitors. BRD4 adopts an extraterminal (ET) domain, which recruits proteins to drive oncogene expression. We discovered a peptide inhibitor PiET targeting the ET domain to disrupt BRD4/JMJD6 interaction, a protein complex critical in oncogene expression and breast cancer. The cell-permeable form of PiET, TAT-PiET, and PROTAC-modified TAT-PiET, TAT-PiET-PROTAC, potently inhibits the expression of BRD4/JMJD6 target genes and breast cancer cell growth. Combination therapy with TAT-PiET/TAT-PiET-PROTAC and JQ1, iJMJD6, or Fulvestrant exhibits synergistic effects. TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC treatment overcomes endocrine therapy resistance in ERα-positive breast cancer cells. Taken together, we demonstrated that targeting the ET domain is effective in suppressing breast cancer, providing a therapeutic avenue in the clinic.

Introduction

Epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and nucleosome remodeling, may contribute to various diseases, including cancer.1,2 The bromodomain and extraterminal domain (BET) protein family, consisting of BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, and BRDT, plays important roles in breast cancer development as epigenetic readers.3 Among the BET protein family members, BRD4 is implicated in a variety of biological processes, including chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, DNA damage repair, cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.4,5 Both bromodomains (BDs) in BRD4, BD1 and BD2, contain four α helices and a variable loop region to form a hydrophobic cavity, which recognizes and binds to acetylated histones to regulate gene transcription. BD inhibitors compete with acetylated histones in occupying the hydrophobic cavity in BDs to inhibit the selective recruitment of BET family protein, including BRD4, to the promoter and/or enhancer of target genes, resulting in transcriptional inhibition.4,6,7 However, the overaccumulated BET proteins8,9 or the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways10,11 lead to inherent or acquired drug resistance and adverse events,12−15 which represent two major challenges for the clinical application of BD inhibitors.

In addition to BDs, BRD4 also associated with proteins involved in transcriptional regulation through its extraterminal (ET) domain to drive gene expression.16−23 The BRD4 ET domain is also reported to bind to the surface of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen (kLANA) to maintain the formation of kLANA “nuclear speckles” and regulate latent replication.24,25 The first reported short peptide binding to ET is derived from the interface of murine leukemia virus γ-retroviral integrase (MLV IN) and BRD4, which blocks the interaction between BRD4 and NSD326 and suppresses the proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells after sequence optimization.27 Therefore, the ET domain is considered as a promising therapeutic target to treat BRD4-related diseases.

We previously reported that BRD4-dependent JMJD6 recruitment on distal enhancers promotes transcriptional pause release and gene expression in the context of the active P-TEFb complex. The enzymatic activity of JMJD6 and the protein–protein interaction (PPI) between JMJD6 and BRD4 are both critical for this process.28 Furthermore, such transcriptional activation mechanism is utilized by breast cancer cells to drive the expression of oncogenic genes, including MYC and CCND1, thereby promoting cell growth and tumorigenesis.29,30 More recently, we discovered a specific small-molecule inhibitor, iJMJD6, targeting the enzymatic activity of JMJD6, which is potent in suppressing oncogene expression and breast cancer development.6

In the current study, we deduced a consensus BRD4 ET domain-binding motif, YXYX, based on computer modeling, where Y represents a positively charged residue and X can be a hydrophilic or lipophilic residue. Five peptide segments containing the YXYX motif were discovered in the JMJD6 protein, among which the peptide RNQKFKCGE exhibited the highest binding affinity with the BRD4 ET domain and effectively disrupted the interaction between BRD4 and JMJD6 in vitro. We named this peptide as the peptide inhibitor targeting ET domain (PiET). Modified PiET with a TAT transmembrane sequence, TAT-PiET, was effective in interrupting the BRD4 and JMJD6 interaction in cultured cells. Furthermore, proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) modified TAT-PiET, TAT-PiET-PROTAC, and degraded BRD4 in an ET domain-dependent manner, suggesting that it specifically targeted the ET domain in BRD4. Both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC potently inhibited the transcriptional activation of BRD4/JMJD6 target genes, including MYC and CCND1, the malignant behaviors of breast cancer cells in culture, and breast tumor growth in xenograft and allograft mouse models. Combination treatment with TAT-PiET/TAT-PiET-PROTAC with JQ1,31 iJMJD6,6,32 or ICI33 exhibited synergistic effects on suppressing breast tumor growth.

Results

BRD4 ET Domain-Binding Motif Is Discovered Based on the Binding Modes between BRD4 ET and ET-Binding Partners

Due to the critical role of the ET domain in BRD4, we sought to identify the consensus peptide motif ET domain binds based on the binding modes between ET and peptides from several ET-interacting partners (Figure S1A).21,26,34 The NMR structures of the BRD4 ET domain revealed that there is a shallow pocket on the protein surface formed by two helices (α1 and α2) and an induced β strand (β1) by peptide binding. The pocket center shapes a hydrophobic surface to accommodate two lipophilic residues from the bound peptides in common. The β1 strand generally makes backbone hydrogen bonds with Ile 652 and Ile 654 to anchor these two residues once the peptide is also folded into a β strand. In addition, Glu 651, Glu 653, and Asp 655 in the β1 strand make ionic interaction with positively charged residues, such as lysine and arginine in the binding peptides21,26,34 (Figure S1B–F). Therefore, a β1 strand peptide motif characterized by two interspaced positively charged residues can be deduced to guide the search of peptide binding with the ET domain. We named this motif YXYX, in which Y represents a positively charged residue and X can be a hydrophilic or lipophilic residue. In this study, we explored the whole sequence of JMJD6 to search for peptides containing the YXYX motif and determine their biological activities.

PiET, a Peptide Inhibitor Specifically Targeting the BRD4 ET Domain to Disrupt BRD4/JMJD6 Interaction, Is Discovered

By searching the protein sequence of JMJD6, five peptide segments (P1 to P5) contain the deduced ET-binding motif YXYX, including one peptide segment (P2) that has been reported to bind with the ET domain21 (Figure 1A). To validate their binding with the ET domain, we synthesized all five peptides, P1 to P5, and performed an SPR assay with the purified ET domain. Among the five peptides tested, the binding affinity between P3 and ET domain was much higher than the other four peptides (Figures 1B–D and S2A–E). The dissociation constant (Kd) of P3 binding with the ET domain was 0.090 μM, which was comparable to that of JMJD6 full-length protein (0.016 μM) (Figure 1B–D). The binding mode between P3 and ET was predicted using the protein–protein docking method and refined by molecular dynamic simulations (Figure 1E). P3 is folded into a β strand and binds to the ET protein surface enriched with positively charged residues (Figure 1E). The two lipophilic residues, Phe and Cys, in P3 are located at the center of the hydrophobic pocket, and two positively charged lysine residues in P3 are engaged in the interaction with Asp 655 and Glu 653 from the ET domain as expected. Such binding mode remains stable even after 200 ns equilibrium simulation (Figure S2F). The binding free energy also indicated that P3 has a strong potential to bind with ET (Figure S2F).

Figure 1.

PiET, a peptide inhibitor specifically targeting the BRD4 ET domain to disrupt BRD4 and JMJD6 interaction, is discovered. (A) Five peptides, P1 to P5, from JMJD6 with “YXYX” motif are shown, where Y represents a positively charged residue and X can be a hydrophilic or lipophilic residue. (B) The binding affinity between purified, His-tagged BRD4 ET and JMJD6 protein or synthetic peptides P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5 was examined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The dissociation constant (Kd) is shown. (C, D) The SPR histograms for JMJD6 protein (C) and P3 peptide (D) as described in (B) are shown. The Kd is shown. (E) Molecular docking analysis results for P3 and ET protein (PDB ID: 2N3K) are shown. P3 is shown as magenta stick. PDB file of the docking model is included in Supporting Information: 2N3K_P3. (F) In vitro GST pull-down assay was performed by mixing purified, GST-tagged ET with or without purified, His-tagged JMJD6 in the presence or absence of P3 (10 μM), followed by immunoblotting (IB) analysis using antibodies as indicated. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; **P < 0.01; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (G) Amino acid sequence of TAT, TAT-PiET, TAT-PROTAC, and TAT-PiET-PROTAC is shown. TAT: cell-penetrating peptide YGRKKRRQRRR; P (OH): trans-4-hydeoxy-l-proline; IYP(OH)YI: VHL ligand; AHX: linker 6-aminohexanoic acid. (H) MCF7 cells transfected with Flag-tagged JMJD6 and His-tagged BRD4 were treated with TAT or TAT-PiET (10 μM) for 12 h, followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag antibody and IB analysis with antibodies as indicated. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (I) MCF7 cells were treated with TAT-PROTAC or different doses of TAT-PiET-PROTAC as indicated for 24 h, followed by IB analysis using antibodies as indicated. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (J) MCF7 cells were treated with TAT-PROTAC (10 μM) for 24 h or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) for different duration as indicated followed by IB analysis using antibodies as indicated. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; **P < 0.01; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (K) MCF7 cells were treated with TAT-PROTAC or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) in the presence or absence of MG132 (10 μM) for 24 h followed by IB analysis. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (L) MCF7 cells were treated with or without TAT, TAT-PROTAC, TAT-PiET, or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) for 24 h followed by IB analysis. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (M) MCF7 cells transfected with His-tagged BRD4 ET (601–683), BRD4 (1–470), BRD4 (471–730), BRD4 (731–1046), or BRD4 (1047–1362) were treated with TAT-PROTAC or different doses of TAT-PiET-PROTAC as indicated for 24 h, followed by IB analysis using antibodies as indicated. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (N) MCF7 cells as described in (M) were treated with TAT-PROTAC or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) for different duration as indicated, followed by IB analysis using antibodies as indicated. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here.

We then tested whether P3 is capable of interrupting the interaction between the BRD4 ET domain and JMJD6. As shown by in vitro GST pull-down assay, P3 inhibited the interaction between the BRD4 ET domain and JMJD6 (Figure 1F). We therefore renamed P3 as the peptide inhibitor targeting the ET domain (PiET). To further test whether PiET can interrupt the interaction between BRD4 and JMJD6 in culture cells, a cell-permeable form of PiET, TAT-PiET, with the twin-arginine translocation (TAT) sequence added to the amino (N)-terminus of PiET was synthesized (Figure 1G). TAT was also synthesized to serve as a control (Figure 1G). The interaction between BRD4 and JMJD6 was inhibited when MCF7 cells were treated with TAT-PiET compared to the TAT control (Figure 1H). To test whether TAT-PiET targets BRD4 directly in cells, we applied PROTAC technology35 to connect a VHL ligand, IYP (OH) AL, using 6-aminohexanoic acid (AHX) to the carboxyl-terminus of TAT-PiET (TAT-PiET-PROTAC) (Figures 1G and S2G). TAT-PROTAC was also synthesized to serve as a control (Figure 1G). Immunoblotting analysis results demonstrated that TAT-PiET-PROTAC, but not TAT-PROTAC, induced the degradation of BRD4 proteins in a dose- and time-dependent manner in MCF7 cells (Figure 1I,J). Interestingly, JMJD6 was similarly downregulated by TAT-PiET-PROTAC (Figure 1I,J), which was due to that the region containing PiET in JMJD6 binds to the JMJD6 protein itself and is required for JMJD6 oligomerization (Figure S3A,B). As expected, the downregulation of BRD4 and JMJD6 protein levels was blocked by proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 1K) and TAT-PiET (Figure 1L). Furthermore, the degradation of BRD4 truncations induced by TAT-PiET-PROTAC only occurred when they contained the ET domain, indicating that TAT-PiET-PROTAC specifically targeted the ET domain in BRD4 (Figure 1M,N). We also compared the bromodomain-based PROTAC, MZ1,36 to TAT-PiET-PROTAC in terms of the potency to downregulate BRD4 proteins. The results showed that MZ1 (1 μM) induced the degradation of full-length BRD4 protein as effectively as TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) (Figure S3C). However, the ability of MZ1 to downregulate BRD4 seemed to only occur in the context of full-length proteins as it failed to do so for any of the truncations we tested, including BRD4 (1–470), which contains the bromodomains (Figure S3C).

Both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC Are Effective in Suppressing Breast Cancer Cell Growth Both in Cultured Cells and in Mouse Tumor Models

To explore the cytotoxic effects of TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC on breast cancer cells, we treated MCF7, T47D, MDA-MB-231, and BT549 cells with a gradient concentration of peptides, followed by a cell proliferation assay. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (EC50) of TAT-PiET in MCF7, T47D, MDA-MB-231, and BT549 was 8.13 ± 1.15, 13.35 ± 1.11, 4.68 ± 1.21, and 32.34 ± 1.11 μM, respectively (Figure S4A). TAT-PiET-PROTAC exhibited very similar effects as TAT-PiET in these cell lines (Figure S4A). However, both peptide inhibitors had minimal effects on HEK293T cells (Figure S4A). The suppressive effects on cell growth were also demonstrated by colony formation assay in MCF7, MDA-MB-231, T47D, and BT549 cells (Figures 2A–H and S4B–I). Both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC effectively inhibited the migration ability of these cells as well, as represented by MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 (Figure 2I–P). To test the antitumor effects of TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC in xenograft mouse models, we subcutaneously injected MCF7 cells into BALB/c nude mice and treated with or without peptide inhibitors. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited in mice with peptide treatment compared to the control group (Figure 2Q–S). Importantly, no significant difference in body weight was found between control and peptide inhibitor-treated mice (Figure S4J). The tumor-suppressive effects of both peptide inhibitors were confirmed in MDA-MB-231 cell-derived xenografts (Figures 2T–V and S4K).

Figure 2.

TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC are effective in suppressing breast cancer cell growth in cultured cells and mouse tumor models. (A, C, E, G) MCF7 (A, E) or MDA-MB-231 (C, G) cells were treated with TAT-PiET (A, C) or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (E, G) (10 μM) followed by cell colony formation assay. TAT (A, C) or TAT-PROTAC (E, G) (10 μM) was used as a negative control. Three biological repeats were performed and representative data is shown. (B, D, F, H) Quantification of the crystal violet dye as shown in (A, C, E, G) is shown (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (I, K, M, O) MCF7 (I, M) or MDA-MB-231 (K, O) cells were treated with TAT-PiET (I, K) or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (M, O) (10 μM) followed by wound healing assay. TAT (I, K) or TAT-PROTAC (M, O) (10 μM) was used as a negative control. Three biological repeats were performed and representative data is shown. (J, L, N, P) Quantification of wound closure as shown in (I, K, M, O) is shown (±SEM; **P < 0.01). (Q) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MCF7 cells, brushed with estrogen (E2, 10–2 M) on the neck every 2 days, randomized, and treated with or without TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (25 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (ip) injection) every 2 days. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (R) Tumors as described in (Q) are shown. (S) The weight of tumors in (R) is shown (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.01). (T) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MDA-MB-231 cells, randomized, and treated with or without TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (25 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection) every 2 days. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; ***P < 0.001). (U) Tumors as described in (T) are shown. (V) The weight of tumors in (U) is shown (±SEM; ***P < 0.001).

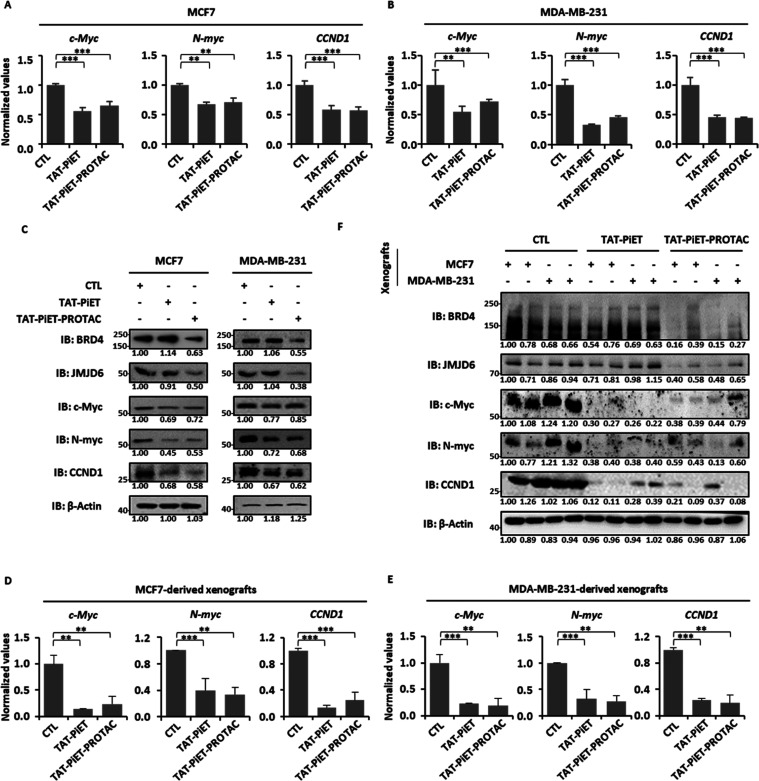

Both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC Repress the Expression of BRD4/JMJD6-Regulated Oncogenes Including MYC and CCND1

We previously reported that the functional importance of BRD4 and JMJD6 in breast cancer development was largely dependent on its regulation of a large set of oncogenes, such as c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1.6,29,30 We then examined whether TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC inhibit the expression of these genes in breast cancer cells.

Treatment with both peptide inhibitors led to decreased expression of c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1 at both mRNA and protein levels in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Figure 3A–C). To link the antitumor effects of TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC with their effects on oncogene expression, a significant decrease of c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1 mRNA and protein levels was detected in both MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell-derived xenografts as well (Figures 3D–F, and 2Q,T). Consistent with the results in culture cells, TAT-PiET-PROTAC treatment induced the degradation of BRD4 and JMJD6 in xenografts (Figure 3C,F). TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC did not affect the mRNA levels of BRD4 or JMJD6 in either culture cells or xenografts (Figure S5A–D).

Figure 3.

TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC downregulate the expression of Myc and CCND1 in breast cancer cells. (A, B) MCF7 (A) or MDA-MB-231 (B) cells were treated with or without TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) for 6 h followed by RT-qPCR analysis to examine the mRNA levels of c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1. Three biological repeats were performed (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (C) MCF7 (left panel) or MDA-MB-231 (right panel) cells were treated with or without TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (10 μM) for 24 h followed by IB analysis to examine the protein levels of BRD4, JMJD6, c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here. (D, E) MCF7 (D) and MDA-MB-231 (E) cell-derived xenograft tumor samples as described in Figure 2S,V, respectively, were subjected to RT-qPCR analysis to examine the mRNA levels of c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1. Three biological repeats were performed (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (F) Representative MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell-derived xenograft tumor samples as described in Figure 2S,V, respectively, were subjected to IB analysis to examine the protein levels of BRD4, JMJD6, c-Myc, N-myc, and CCND1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The experiments were repeated three times and included in the Supporting Table (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). Representative data is shown here.

Co-administration of the BD Inhibitor JQ1 and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC Exhibits Synergistic Effects on Suppressing Breast Tumor Growth

The bromodomains (BDs) are crucial for BRD4 in binding to acetylated histones to regulate oncogene expression. JQ1, a commonly used small-molecule inhibitor that targets BRD4 BDs to disrupt the association of BRD4 with acetylated histones, has great therapeutic potential in treating cancers, including breast cancer.19,31,37,38 The potency of TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC in suppressing breast tumor growth prompted us to explore the therapeutic potential of simultaneously targeting the BD and ET domain in BRD4 by using JQ1 and TAT-PiET/TAT-PiET-PROTAC, respectively. Co-treatment with JQ1 and peptide inhibitors led to a more dramatic reduction in cell proliferation (Figure 4A,B), colony formation (Figures 4C,D, and S6A,B), and migration (Figures 4E,F, and S6C,D) in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Similar observations were also made in T47D cells (Figure S6E–G). The therapeutic efficacy of JQ1 and peptide alone or in combination was further tested on MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell-derived xenografts in mice. The results showed that tumor volume and weight were inhibited more significantly in the group with combination treatment compared to the groups with each treatment alone (Figure 4G–L). There was no significant difference in body weight in different groups (Figure S6H,K). Organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney from drug-treated mice showed normal morphology and no significant difference in weight compared to control groups (Figure S6I,J).

Figure 4.

Combination treatment with the BD inhibitor JQ1 and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC exhibits synergistic effects on suppressing breast tumor growth. (A–F) MCF7 (A, C, E) or MDA-MB-231 (B, D, F) cells were treated with peptide inhibitors (10 μM) or JQ1 (5 μM) alone or in combination, followed by cell proliferation assay (A, B), colony formation assay (C, D), and wound healing assay (E, F). Three biological repeats were performed. Representative data is shown for colony formation and wound healing (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (G) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MCF7 cells, brushed with estrogen (E2, 10–2 M) on the neck every 2 days, randomized, and treated with peptide inhibitors (12.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (ip) injection) or JQ1 (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (ip) injection) every 2 days alone or in combination. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (H) Tumors as described in (G) are shown. (I) The weight of tumors as described in (H) is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (J) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MDA-MB-231 cells, randomized, and treated with peptide inhibitors (12.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection) or JQ1 (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection) every 2 days alone or in combination. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (K) Tumors as described in (J) are shown. (L) The weight of tumors as described in (K) is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

iJMJD6 in Combination with TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC Results in Synergistic Effects on Suppressing Breast Tumor Growth

We reported that BRD4 and JMJD6 regulation of gene expression depends not only on their interaction but also on JMJD6 enzymatic activity.28−30 More recently, we reported that a small-molecule inhibitor, iJMJD6, specifically inhibits the enzymatic activity of JMJD6 and potently suppresses breast tumor growth.6 Therefore, we tested the therapeutic potential of combination treatment with iJMJD6 and TAT-PiET/TAT-PiET-PROTAC in breast cancer. Such a strategy will simultaneously disrupt the interaction between BRD4/JMJD6 and inhibit the enzymatic activity of JMJD6. As expected, significantly decreased ability in cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration was induced by either treatment alone in MCF7 cells, while combination treatment induced more profound effects (Figures 5A–C and S7A,B). Similar results were obtained in MDA-MB-231 (Figures 5D–F and S7C,D) and T47D cells (Figure S7E–G). Furthermore, tumor growth was significantly more inhibited in the group with combination treatment compared with the groups with each inhibitor treatment alone in the MCF7 cell-derived xenograft mouse model (Figure 5G–I). There was no significant change of the weight of body and organs in any group (Figure S7H–J).

Figure 5.

Combination treatment with iJMJD6 and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC exhibits synergistic effects on suppressing breast tumor growth. (A–F) MCF7 (A–C) or MDA-MB-231 (D–F) cells were treated with peptide inhibitors (10 μM) or iJMJD6 (10 μM) alone or in combination, followed by cell proliferation assay (A, D), colony formation assay (B, E), and wound healing assay (C, F). Three biological repeats were performed and representative data is shown for colony formation and wound healing (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (G) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MCF7 cells, brushed with estrogen (E2, 10–2 M) on the neck every 2 days, randomized, and treated with peptide inhibitors (12.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (ip) injection) every 2 days or iJMJD6 (12.5 mg/kg, ip injection) every other day alone or in combination. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (H) Tumors as described in (G) are shown. (I) The weight of tumors as described in (H) is shown (±SEM; P* < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Combination Treatment with ERα Degrader Fulvestrant (ICI) and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC Exhibits Synergistic Effects on Suppressing ERα-Positive Breast Tumor Growth

The suppressive effects of peptide inhibitors, TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC, in ERα-positive breast tumor growth prompted us to examine the therapeutic effects of combination treatment with peptide inhibitor and fulvestrant (ICI), a selective estrogen receptor degrader that is used as a frontline treatment for ERα-positive breast cancer in the clinic.33 As expected, TAT-PiET, TAT-PiET-PROTAC, and ICI treatment alone significantly inhibited the cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration ability of the MCF7 cells. Combination treatment with ICI and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC exhibited synergistic effects (Figure 6A–E). Similar observations were made in T47D cells (Figure S8A–C). We further tested the antitumor effect of combination treatment in the MCF7 cell-derived xenograft mouse model. The effect of the combination therapy on tumor weight and volume was more pronounced than that of ICI or the peptide inhibitor alone (Figure 6F–H). There was no significant difference in body and organ weight in different groups (Figure S8D,E).

Figure 6.

Combination treatment with ICI and TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC exhibits synergistic effects on suppressing ERα-positive breast tumor growth. (A, B, D) MCF7 cells were treated with peptide inhibitors (10 μM) or ICI (2.5 μM) alone or in combination, followed by cell proliferation assay (A), colony formation assay (B), and wound healing assay (D). Three biological repeats were performed and representative data is shown for colony formation and wound healing (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (C) Quantification of the crystal violet dye in (B) is shown (±SEM; ***P < 0.001). (E) Quantification of the wound closure in (D) is shown (±SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (F) Female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated with MCF7 cells, brushed with estrogen (E2, 10–2 M) on the neck every 2 days, randomized, and treated with peptide inhibitors (12.5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (ip) injection) every 2 days or ICI (2.5 mg/kg, subcutaneous (sc) injection) every 6 days alone or in combination. Tumor growth curve is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). (G) Tumors as described in (F) are shown. (H) The weight of tumors as described in (G) is shown (±SEM; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC Treatment Overcomes Endocrine Therapy Resistance in ERα-Positive Breast Cancer Cells

Endocrine therapy resistance represents one of the major challenges for ERα-positive breast cancer in the clinic. Both BRD4 and JMJD6 have been reported to be involved in the development of endocrine therapy resistance, such as tamoxifen and ICI resistance.30,39,40 We therefore tested whether TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC treatment will resensitize tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 cells to tamoxifen treatment. The results showed that both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC treatment resensitized tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 cells as seen from cell proliferation and colony formation assay (Figure 7A–C). Similarly, tamoxifen-resistant T47D cells became sensitive to tamoxifen in the presence of TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC (Figure 7D–F).

Figure 7.

TAT-PiET or TAT-PiET-PROTAC treatment overcomes endocrine therapy resistance in ERα-positive breast cancer cells. (A, B, D, E) Tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 (A, B) or T47D (D, E) cells were treated with peptide inhibitors (10 μM) or tamoxifen (3 μM) alone or in combination, followed by cell proliferation assay (A, D) and colony formation assay (B, E). Three biological repeats were performed and representative data is shown for colony formation (±SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant). (C, F) Quantification of the crystal violet dye in (B) and (E) is shown (±SEM; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant).

Discussion and Conclusions

The critical roles of BRD4 in gene transcription regulation and tumorigenesis make it a promising anticancer target. BD inhibitors exert their anticancer effects through targeting the bromodomains (BDs) to block BRD4 binding to chromosomes. The BRD4 ET domain plays a crucial role in maintaining protein–protein interactions between BRD4 and other transcription factors/cofactors and thus the function of BRD4 in various oncogenic pathways. However, the development of inhibitors targeting the ET domain is very limited.

The functions of BRD4/JMJD6 on antipause enhancers and transcription regulation are largely dependent on the BRD4 ET domain, which have intriguing implications in development and disease. To disrupt the interaction between BRD4 and JMJD6, we performed docking analysis based on the interaction mode between the ET domain and peptides known to bind with the ET domain, resulting in the discovery of a motif YXYX, where Y represents a positively charged residue and X can be a hydrophilic or lipophilic residue. Five such peptide motifs were discovered in JMJD6. One of these peptides was confirmed to bind with the ET domain with the highest affinity, which is capable of inhibiting the interaction between BRD4 and JMJD6 invitro and its cell-permeable form does so in cultured cells. We named this peptide and its cell-permeable form PiET and TAT-PiET, respectively. The targeting specificity of TAT-PiET to the ET domain was demonstrated, such that its PROTAC form, TAT-PiET-PROTAC, specifically induces BRD4 degradation in an ET domain-dependent manner. Interestingly, TAT-PiET-PROTAC also appeared to induce JMJD6 degradation, which is due to the region where PiET is located in JMJD6 being critical for JMJD6 oligomerization, enabling the binding of TAT-PiET-PROTAC with the JMJD6 protein and therefore JMJD6 degradation. Similar to knockdown of BRD4 and JMJD6, TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC are effective in downregulating the expression of MYC and CCND1 in cultured breast cancer cells and breast cancer cell-derived tumors. Therefore, both TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC are potent in suppressing breast tumor growth in mouse tumor models.

The functions of BRD4/JMJD6 in transcription regulation are dependent not only on the BRD4 ET domain but also on BRD4 BDs, providing a molecular basis for combination treatment strategy using ET and BD inhibitors together. Indeed, simultaneously targeting the ET with PiET and the BD with the BD inhibitor JQ1 exhibited more profound effects on suppressing breast tumor growth. In addition, the functions of BRD4/JMJD6 in transcription regulation are dependent on not only BRD4 and JMJD6 protein–protein interaction but also JMJD6 enzymatic activity, providing a molecular basis for combination treatment strategy using ET and JMJD6 inhibitor together. Indeed, targeting the interaction of BRD4 and JMJD6 with PiET and JMJD6 enzymatic activity with iJMJD6 achieved synergistic effects. Endocrine therapy targeting ERα, including tamoxifen and fulvestrant (ICI), is the frontline treatment for ER-positive breast cancer. However, a fraction of ER-positive breast cancer patients does not benefit from endocrine therapy due to primary and acquired resistance. As BRD4/JMJD6 plays an essential role in ERα-mediated gene transcriptional activation and ER-positive breast cancer development, the therapeutic effects of combination treatment with ICI and PiET were explored and synergistic effects on tumor growth suppression were observed. In addition, PiET resensitized tamoxifen-resistant ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines to tamoxifen treatment. Furthermore, TAT-PiET-PROTAC may overcome BET inhibitor resistance caused by BRD4 protein accumulation and stability.8,41,42 As BRD4 plays an essential role in the development of many other cancer types, one could envision that PiET might be a promising candidate to test for tumor suppression in these cancer types. Due to the diversified interacting partners of the ET domain in BRD4 as well as other members from the BET family, we also need to consider the potential side effects of peptide inhibitors targeting ET. PiET appears to be safe in mice as assessed from mice body and organ weight upon PiET treatment. Further modification of PiET to increase its anticancer activity as well as exploration of the toxic side effects remains an interesting topic for future study.

In conclusion, TAT-PiET and TAT-PiET-PROTAC are two peptide inhibitors that are potent in suppressing breast tumor growth. Their specificity in targeting the ET domain and activity in suppressing tumor growth makes them promising candidate tools for further exploring BRD4 ET function and promising avenues for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer.

Experimental Section

Plasmids and Cloning Procedures

pET-28a-JMJD6, pBobi-3 × FLAG-3 × HA-JMJD6, pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 (full-length), pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 (1–470), pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 (471–730), pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 (731–1046), and pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 (1047–1362) expression vectors were reported previously.28,29 BRD4 ET (601–683) was PCR-amplified from full-length BRD4 by using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara) and then cloned into pGEX-6P-1 (Promega) expression vectors. JMJD6 PiET deletion (Δ95–103) was PCR-amplified from full-length JMJD6 by using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase and then cloned into pET-28a (Promega) expression vectors.

Antibodies and Compounds

The information on commercial antibodies used in this study are listed as following: GST (Proteintech, 66001–1-Ig), His (Santa Cruz, sc-803), Flag (Sigma, F3165), BRD4 (Bethyl Laboratories, A301–985A100), JMJD6 (Proteintech, 16476–1-AP), β-actin (Proteintech, 66009–1-Ig), c-Myc (Santa Cruz, sc-8432), N-myc (Santa Cruz, sc-53993), and CCND1 (Proteintech, 60186–1-Ig). Peptides P1 to P5, TAT, TAT-PROTAC, TAT-PiET, and TAT-PiET-PROTAC were synthesized by GenScript, all peptides are >95% pure by HPLC analysis (see details in Supporting Information: Molecular formula strings). JQ1 (HY-13030), fulvestrant (ICI) (HY-13636), MZ1 (HY-107425), and MG132 (HY-13259) were purchased from MedChemExpress. iJMJD6 was synthesized in-house as previously reported.6

Expression and Purification of Proteins from Bacterial Cells

For His-tagged protein, transformed BL21 (DE3) competent cells (Agilent, 200131) were inoculated with LB medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/mL) at 37 °C. When the OD600 of culture medium reached ∼0.7, IPTG (1 mM) was added, followed by incubation at 25 °C overnight. Cells were spun down and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P2714-IBTL). After sonication (10 s bursts at 80% power with a 10 s cooling period between each burst), the lysates were spun down for 30 min at 15,000 rpm and the supernatant was incubated with His beads (HisPur Ni-NTA Resin, Thermo) for 2 to 4 h. Beads were then washed with washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) to remove nonspecific binding and then eluted with elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Buffer exchange was then performed with PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, 17268612). Purified proteins were stored in storage buffer (10% glycerol, 90% PBS) at −80 °C. For GST-tagged protein, the procedure was similar to that for His-tagged protein purification with modifications. Bacterial cells were inoculated with LB medium containing ampicillin (100 mg/mL). Cell pellets were resuspended in PBS, and then Triton X-100 (Sigma T8787) was added (final concentration 1%), followed by immediate sonication. Cell lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min. Glutathione agarose beads (Sigma, G4510) were used for protein enrichment, and washing buffer (1% Triton X-100 in PBS) was used for removing nonspecific binding. Proteins were eluted with an elution buffer (10 mM glutathione, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0).

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

A CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) was activated by injecting 100 μL of N-ethyl-N0–3-(diethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) (200 mM) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (50 mM) (v/v 1:1). Bacterially expressed His-tagged ET proteins in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) were immobilized on the preactivated CM5 chip using amine coupling according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The remaining ester groups were blocked by injecting 100 μL of 1 M ethanolamine HCl (pH 8.0). The amount of immobilized ET was detected by mass concentration-dependent changes in the refractive index on the sensor chip surface and corresponded to about 10,000 resonance units (RU). A serial concentration of the compounds was added at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. When the data collection was finished in each cycle, the sensor surface was washed with glycine HCl (10 mM, pH 2.5). Sensor grams were fit globally with the BIAcore T200 analysis tool using 1:1 Langmuir binding mode.

Immunoblotting Assay

Cell or tumor tissue lysates (in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) or purified protein (in PBS or elution buffer) was boiled in SDS sample buffer (1% SDS, 5% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.25% bromophenol blue) for 10 min, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE gel in SDS running buffer (25 mM Tris, 250 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS), and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked by adding TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) containing 5% milk, and the mixture was gently shaken for 1 h at 25 °C, which was then incubated with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer and washed five times with TBST, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Membranes were then rinsed extensively with TBST before imaging. WesternBright Peroxide (Advansta, R-03025-D25) and WesternBright ECL (Advansta, R-03031-D25) were mixed at a 1:1 ratio before being added onto the membranes for 5 min. Imaging was performed with a Chemiluminescent Imaging System (CHAMPCHEMITM). All immunoblotting analyses were repeated at least three times and the results are presented in the Supporting Table.

Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) Pull-Down Assay

Glutathione agarose beads (Sigma, G4510) were equilibrated in binding buffer (1% Triton X-100 in PBS) and then incubated with purified GST-tagged ET proteins, followed by washing with PBB buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM ZnCl2, 10 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1× cocktail) three times. Purified His-tagged JMJD6 with or without peptide P3 (10 μM) were mixed with glutathione agarose beads conjugated with GST-ET proteins overnight at 4 °C under gentle rotation. After 5 times wash by using washing buffer NETN (1 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5% NP-40), beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer (1% SDS, 5% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.25% bromophenol blue) for 10 min, resolved by SDS-PAGE gel, and analyzed by immunoblotting assay.

Immunoprecipitation Assay

HEK293T cells were seeded in culture plates coated with poly-d-lysine (0.1% (w/v), Sigma, P7280) and transfected with pBobi-3 × FLAG-3 × HA-JMJD6 and pcDNA4C-his-Brd4 using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, 11668019) for 48 h. After treating with or without TAT-PiET (10 μM) for 12 h, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitor cocktail at 4 °C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation. The resultant supernatant was incubated with Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma, A2220) in TBS (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight and then washed 5 times with lysis buffer. Beads were then resuspended and boiled in SDS sample buffer, and the associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was then performed as described above.

Cell Culture

MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) medium, and T47D and BT549 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37 °C.

Cell Viability, Cell Colony Formation, and Wound Healing Assays

For the cell viability assay, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 103/well in 100 μL of culture medium and treated with or without peptide inhibitors for days as indicated. When measuring EC50, cells were treated with peptide inhibitors for 1 week. To measure cell viability, 20 μL of CellTiter 96 Aqueous one solution reagent (Promega, G3580) was added per 100 μL of culture medium, and the culture plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere incubator. Data was recorded at a wavelength of 490 nm using Infinite F50 (TECAN). For the cell colony formation assay, cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well and treated with or without peptide inhibitors for 2 weeks. The colonies were stained with crystal violet. To measure colony density, 10% acetic acid was added to resolve the crystal and recorded at a wavelength of 590 nm using Infinite F50. For wound healing assay, cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well and wounds were created with a 10 μL plastic pipet tip when the cells were 80–90% confluent. The cells were cultured in serum-free medium and treated with or without peptide inhibitors for time as indicated. The wound lines were photographed using an inverted microscope DMi8 (Leica). Three images of each well were taken. The wounded area was measured and recorded as A0, which was measured 12 or 24 h later again and recorded as A1. Cell migration was presented as wound closure (%) = (wounded area (A0 – A1)/wounded area A0) × 100%.

Animal Experiments

Female BALB/C nude mice (age 4–6 weeks) were subcutaneously implanted with 5 × 106 of MCF7 or MDA-MB-231 cells suspended in PBS. To support MCF7 cell-derived xenograft growth, mice were brushed with estrogen (E2, 10–2 M) every 2 days for the duration of the experiments. The length and width were measured using a vernier caliper every 2 days to calculate tumor volume (1/2 × length × width2). When the average tumor volume reached ∼50 mm3, the mice were randomly divided and subjected to treatment. Peptide inhibitors were dissolved in normal saline (0.9% NaCl) by intraperitoneal injection (25 mg/kg) every 2 days; ICI was dissolved in DMSO and mixed with corn oil in a ratio of 1:10 by subcutaneous injection (2.5 mg/kg) every 6 days; JQ1 was dissolved in DMSO and mixed with 10% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPBCD) in a ratio of 1:10 by intraperitoneal injection (50 mg/kg) every 2 days; iJMJD6 was dissolved in DMSO and mixed with PBS in a ratio of 1:20 by intraperitoneal injection (25 mg/kg) every 2 days. When used in combination treatment, drug dose was reduced to half. Animals were housed in the Animal Facility at Xiamen University under pathogen-free conditions, following the protocol approved by the Xiamen Animal Care and Use Committee of Xiamen University (XMULAC20210126).

RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells and xenograft tumors using RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa) following the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA synthesis from total RNA was carried out using Plus All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Novoprotein). Resulting cDNA was then analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using HiScript II One Step RT-PCR Kit (Vazyme, P611–01) with an Agilent AriaMx machine. All RT-qPCRs were repeated at least three times, and the relative abundance of each transcript was normalized to the expression level of actin and then to the control samples. Sequence information for all primers used for RT-qPCR was included in the Supporting Table.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82125028, U22A20320, 91953114, 31871319, 81761128015, and 81861130370), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0112300, 2020YFA0803600) to W.L., China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M682088) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82203477) to R.X., and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M720119) to Z. Zheng. The authors thank Dr. Qiang Liu for providing Tamoxifen-resistant MCF7 and T47D cells.

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- BET

bromodomain and extraterminal

- BRD4

bromodomain-containing protein 4

- BRD2

bromodomain-containing protein 2

- BRD3

bromodomain-containing protein 3

- BRDT

bromodomain-containing protein T

- BDs

bromodomains

- ET

extraterminal

- JMJD6

Jumonji domain-containing 6

- ICI

fulvestrant

- ERα

estrogen receptor α

- kLANA

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen

- MLV IN

murine leukemia virus γ-retroviral integrase

- P-TEFb

positive transcription elongation factor b

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- PROTAC

proteolysis-targeting chimera

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c00141.

Immunoblotting analyses and sequence information for all primers (XLSX)

PDB files: 2N3K_P3 (BRD4 ET bound with P3), 2N3K (BRD4 ET bound with MLV), 2NCZ and 2ND1 (BRD4 ET bound with NSD3), 2ND0 (BRD4 ET bond with LANA), and 6BNH (BRD4 ET bound with JMJD6) (ZIP)

Binding mode analysis for ET and known peptides that bind to ET; region where PiET is located in JMJD6 is required for JMJD6 oligomerization; combination treatment with TAT-PiET/TAT-PiET-PROTAC with JQ1, iJMJD6 or ICI; HPLC analysis of peptides, mass spectrometry analysis of peptides, and production protocol of peptides (PDF)

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

Author Contributions

⊥ Q.H., D.F., Z.Z. and T.R. contributed equally to this work. W.L. and Q.H. conceived the original ideas, designed the project, and wrote the manuscript with inputs from D.F., Z.Z., and T.R. Q.H. performed the majority of the experiments with participation from D.F., Z.Z., A.B., R.X, and G.H. T.R. performed the molecular docking analyses.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vick A. D.; Burris H. H. Epigenetics and Health Disparities. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4 (1), 31–37. 10.1007/s40471-017-0096-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Chen W.; Liu S.; Chen C. Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19 (2), 552–570. 10.7150/ijbs.76187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni J. M.; Keri R. A. Targeting bromodomain and extraterminal proteins in breast cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 156–176. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Zheng Q.; Peng Y. BET proteins: Biological functions and therapeutic interventions. Pharmacol Ther 2023, 243, 108354 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H. A.; Li Y.; Bilal A. H. M.; Qin T.; Yuan Z.; Zhao W. A Comprehensive Review of BET Protein Biochemistry, Physiology, and Pathological Roles. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 818891 10.3389/fphar.2022.818891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R. Q.; Ran T.; Huang Q. X.; Hu G. S.; Fan D. M.; Yi J.; Liu W. A specific JMJD6 inhibitor potently suppresses multiple types of cancers both in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119 (34), e2200753119 10.1073/pnas.2200753119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran A. G.; Conery A. R.; Sims R. J. 3rd Bromodomains: a new target class for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18 (8), 609–628. 10.1038/s41573-019-0030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X.; Gan W.; Li X.; Wang S.; Zhang W.; Huang L.; Liu S.; Zhong Q.; Guo J.; Zhang J.; et al. Prostate cancer-associated SPOP mutations confer resistance to BET inhibitors through stabilization of BRD4. Nat. Med. 2017, 23 (9), 1063–1071. 10.1038/nm.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Wang D.; Zhao Y.; Ren S.; Gao K.; Ye Z.; Wang S.; Pan C. W.; Zhu Y.; Yan Y.; et al. Intrinsic BET inhibitor resistance in SPOP-mutated prostate cancer is mediated by BET protein stabilization and AKT-mTORC1 activation. Nat. Med. 2017, 23 (9), 1055–1062. 10.1038/nm.4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu S.; Lin C. Y.; He H. H.; Witwicki R. M.; Tabassum D. P.; Roberts J. M.; Janiszewska M.; Huh S. J.; Liang Y.; Ryan J.; et al. Response and resistance to BET bromodomain inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer. Nature 2016, 529 (7586), 413–417. 10.1038/nature16508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K.; Raza S. S.; Knab L. M.; Chow C. R.; Kwok B.; Bentrem D. J.; Popovic R.; Ebine K.; Licht J. D.; Munshi H. G. GLI2-dependent c-MYC upregulation mediates resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9489 10.1038/srep09489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim S.; Stathis A.; Gleeson M.; Iyengar S.; Magarotto V.; Leleu X.; Morschhauser F.; Karlin L.; Broussais F.; Rezai K.; et al. Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma: a dose-escalation, open-label, pharmacokinetic, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3 (4), E196–E204. 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthon C.; Raffoux E.; Thomas X.; Vey N.; Gomez-Roca C.; Yee K.; Taussig D. C.; Rezai K.; Roumier C.; Herait P.; et al. Bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 in patients with acute leukaemia: a dose-escalation, phase 1 study. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3 (4), E186–E195. 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falchook G.; Rosen S.; LoRusso P.; Watts J.; Gupta S.; Coombs C. C.; Talpaz M.; Kurzrock R.; Mita M.; Cassaday R.; et al. Development of 2 Bromodomain and Extraterminal Inhibitors With Distinct Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Profiles for the Treatment of Advanced Malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26 (6), 1247–1257. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piha-Paul S. A.; Sachdev J. C.; Barve M.; LoRusso P.; Szmulewitz R.; Patel S. P.; Lara P. N. Jr.; Chen X.; Hu B.; Freise K. J.; et al. First-in-Human Study of Mivebresib (ABBV-075), an Oral Pan-Inhibitor of Bromodomain and Extra Terminal Proteins, in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25 (21), 6309–6319. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhar M.; Ebert A.; Neumann T.; Umkehrer C.; Jude J.; Wieshofer C.; Rescheneder P.; Lipp J. J.; Herzog V. A.; Reichholf B.; et al. SLAM-seq defines direct gene-regulatory functions of the BRD4-MYC axis. Science 2018, 360 (6390), 800–805. 10.1126/science.aao2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.; Pinto H. B.; Kamikawa Y. F.; Donohoe M. E. The BET family member BRD4 interacts with OCT4 and regulates pluripotency gene expression. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 4 (3), 390–403. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollavilli P. N.; Pawar A.; Wilder-Romans K.; Natesan R.; Engelke C. G.; Dommeti V. L.; Krishnamurthy P. M.; Nallasivam A.; Apel I. J.; Xu T.; et al. EWS/ETS-Driven Ewing Sarcoma Requires BET Bromodomain Proteins. Cancer Res. 2018, 78 (16), 4760–4773. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Wang Y.; Zeng L.; Wu Y.; Deng J.; Zhang Q.; Lin Y.; Li J.; Kang T.; Tao M.; et al. Disrupting the interaction of BRD4 with diacetylated Twist suppresses tumorigenesis in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2014, 25 (2), 210–225. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S.; Sowa M. E.; Ottinger M.; Smith J. A.; Shi Y.; Harper J. W.; Howley P. M. The Brd4 extraterminal domain confers transcription activation independent of pTEFb by recruiting multiple proteins, including NSD3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31 (13), 2641–2652. 10.1128/MCB.01341-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konuma T.; Yu D.; Zhao C.; Ju Y.; Sharma R.; Ren C.; Zhang Q.; Zhou M. M.; Zeng L. Structural Mechanism of the Oxygenase JMJD6 Recognition by the Extraterminal (ET) Domain of BRD4. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 16272 10.1038/s41598-017-16588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A. E.; Kleffmann T.; Mace P. D. Oncogenic Truncations of ASXL1 Enhance a Motif for BRD4 ET-Domain Binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433 (22), 167242 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepanski A. P.; Zhao Z.; Sosnowski T.; Goo Y. A.; Bartom E. T.; Wang L. ASXL3 bridges BRD4 to BAP1 complex and governs enhancer activity in small cell lung cancer. Genome Med. 2020, 12 (1), 63 10.1186/s13073-020-00760-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellert J.; Weidner-Glunde M.; Krausze J.; Richter U.; Adler H.; Fedorov R.; Pietrek M.; Ruckert J.; Ritter C.; Schulz T. F.; Lührs T. A structural basis for BRD2/4-mediated host chromatin interaction and oligomer assembly of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and murine gammaherpesvirus LANA proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9 (10), e1003640 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottinger M.; Christalla T.; Nathan K.; Brinkmann M. M.; Viejo-Borbolla A.; Schulz T. F. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA-1 interacts with the short variant of BRD4 and releases cells from a BRD4- and BRD2/RING3-induced G1 cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 2006, 80 (21), 10772–10786. 10.1128/JVI.00804-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe B. L.; Larue R. C.; Yuan C.; Hess S.; Kvaratskhelia M.; Foster M. P. Structure of the Brd4 ET domain bound to a C-terminal motif from gamma-retroviral integrases reveals a conserved mechanism of interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113 (8), 2086–2091. 10.1073/pnas.1516813113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing E.; Surendranathan N.; Kong X.; Cyberski N.; Garcia J. D.; Cheng X.; Sharma A.; Li P. K.; Larue R. C. Development of Murine Leukemia Virus Integrase-Derived Peptides That Bind Brd4 Extra-Terminal Domain as Candidates for Suppression of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4 (5), 1628–1638. 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Ma Q.; Wong K.; Li W.; Ohgi K.; Zhang J.; Aggarwal A.; Rosenfeld M. G. Brd4 and JMJD6-associated anti-pause enhancers in regulation of transcriptional pause release. Cell 2013, 155 (7), 1581–1595. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W. W.; Xiao R. Q.; Zhang W. J.; Hu Y. R.; Peng B. L.; Li W. J.; He Y. H.; Shen H. F.; Ding J. C.; Huang Q. X.; et al. JMJD6 Licenses ERalpha-Dependent Enhancer and Coding Gene Activation by Modulating the Recruitment of the CARM1/MED12 Co-activator Complex. Mol. Cell 2018, 70 (2), 340–357. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z. Z.; Xia L.; Hu G. S.; Liu J. Y.; Hu Y. H.; Chen Y. J.; Peng J. Y.; Zhang W. J.; Liu W. Super-enhancer-controlled positive feedback loop BRD4/ERalpha-RET-ERalpha promotes ERalpha-positive breast cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (18), 10230–10248. 10.1093/nar/gkac778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P.; Qi J.; Picaud S.; Shen Y.; Smith W. B.; Fedorov O.; Morse E. M.; Keates T.; Hickman T. T.; Felletar I.; et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1067–1073. 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran T.; Xiao R.; Huang Q.; Yuan H.; Lu T.; Liu W. In Silico Discovery of JMJD6 Inhibitors for Cancer Treatment. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (12), 1609–1613. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanker A. B.; Sudhan D. R.; Arteaga C. L. Overcoming Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37 (4), 496–513. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Zeng L.; Shen C.; Ju Y.; Konuma T.; Zhao C.; Vakoc C. R.; Zhou M. M. Structural Mechanism of Transcriptional Regulator NSD3 Recognition by the ET Domain of BRD4. Structure 2016, 24 (7), 1201–1208. 10.1016/j.str.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.; Zou Y.; Chu Y.; Liu Z.; Liu G.; Chu J.; Li M.; Wang J.; Sun S. Y.; Chang Z. A cell-permeable peptide-based PROTAC against the oncoprotein CREPT proficiently inhibits pancreatic cancer. Theranostics 2020, 10 (8), 3708–3721. 10.7150/thno.41677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengerle M.; Chan K. H.; Ciulli A. Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10 (8), 1770–1777. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asangani I. A.; Dommeti V. L.; Wang X.; Malik R.; Cieslik M.; Yang R.; Escara-Wilke J.; Wilder-Romans K.; Dhanireddy S.; Engelke C.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of BET bromodomain proteins in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 2014, 510 (7504), 278–282. 10.1038/nature13229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civenni G.; Bosotti R.; Timpanaro A.; Vazquez R.; Merulla J.; Pandit S.; Rossi S.; Albino D.; Allegrini S.; Mitra A.; et al. Epigenetic Control of Mitochondrial Fission Enables Self-Renewal of Stem-like Tumor Cells in Human Prostate Cancer. Cell Metab. 2019, 30 (2), 303–318. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alluri P. G.; Asangani I. A.; Chinnaiyan A. M. BETs abet Tam-R in ER-positive breast cancer. Cell Res. 2014, 24 (8), 899–900. 10.1038/cr.2014.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P.; Gupta A.; Desai K. V. JMJD6 orchestrates a transcriptional program in favor of endocrine resistance in ER+ breast cancer cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1028616 10.3389/fendo.2022.1028616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janouskova H.; El Tekle G.; Bellini E.; Udeshi N. D.; Rinaldi A.; Ulbricht A.; Bernasocchi T.; Civenni G.; Losa M.; Svinkina T.; et al. Opposing effects of cancer-type-specific SPOP mutants on BET protein degradation and sensitivity to BET inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2017, 23 (9), 1046–1054. 10.1038/nm.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X.; Yan Y.; Wang D.; Ding D.; Ma T.; Ye Z.; Jimenez R.; Wang L.; Wu H.; Huang H. DUB3 Promotes BET Inhibitor Resistance and Cancer Progression by Deubiquitinating BRD4. Mol. Cell 2018, 71 (4), 592–605. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.