Abstract

Background:

Fragile X syndrome (FXS), the leading cause of inherited intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder, is associated with multiple neurobehavioral abnormalities including sleep difficulties. Nonetheless, frequency, severity, and consequences of sleep problems are still unclear.

Method:

The Fragile X Online Registry with Accessible Research Database (FORWARD-version-3), including Clinician Report and Parent Report forms, was analyzed for frequency, severity, relationship with behavioral problems, and impact of sleep difficulties in a mainly pediatric cohort. A focused evaluation of sleep apnea was also conducted.

Results:

Six surveyed sleep difficulties were moderately frequent (~23%-46%), relatively mild, affected predominantly younger males, and considered a problem for 7-20% families. Snoring was more prevalent in older individuals. All sleep difficulties were associated with irritability/aggression and most also to hyperactivity. Only severe snoring was correlated with sleep apnea (loud snoring: 30%; sleep apnea: 2-3%).

Conclusion:

Sleep difficulties are prevalent in children with FXS and, although they tend to be mild, they are associated with behavioral problems and negative impact to families. Because of its cross-sectional nature, clinic-origin, use of ad hoc data collection forms, and lack of treatment data, the present study should be considered foundational for future research aiming at better recognition and management of sleep problems in FXS.

Keywords: Fragile X syndrome, insomnia, sleep apnea, quality of life, problem behaviors

1. INTRODUCTION

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability (ID) and monogenic cause of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2008)ffecting up to 1 in 7,000 males and 1 in 11,000 females in the US (Hunter et al., 2014). FXS is associated with a full mutation CGG expansion (≥200) in 5’ untranslated region of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene, which leads to epigenetic silencing and consequent reduction of the translational regulator fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (Kaufmann et al., 1999; Tassone et al., 2012). Levels of FMRP correlate with overall severity of the FXS phenotype, exemplified by level of ID, with males being more severely affected due to the X-linked pattern of inheritance (Budimirovic et al., 2020; Kaufmann et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2019; Loesch et al., 2004). In addition to cognitive impairment, affected individuals are at increased risk for a wide range of behavioral abnormalities, including anxiety, hyperarousal, impulsivity, self-injurious behavior, aggression, irritability, and severe autistic behavior (Hagerman & Polussa, 2015; Budimirovic et al., 2014 (updated 2020); Hernandez et al., 2009; Kaufmann et al., 2017).

Sleep difficulties are also frequent in FXS, occurring in 27-77% of individuals (Agar et al., 2021; Kidd et al., 2014; Kronk et al., 2010; Kronk et al., 2009; Richdale, 2009; Symons et al., 2010), a wide range reflecting differences in study design and instruments of assessment. Kronk and colleagues (2010) reported on a large parental survey (n=1,295) that revealed that both sleep onset and maintenance difficulties were frequent in FXS. A recent large meta-analysis of 273 articles also showed high prevalence of sleep difficulties among 55,310 individuals with 19 different genetic syndromes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), including FXS (Agar et al., 2021). Frequency of sleep difficulties in FXS is comparable to that of other NDDs such Rett syndrome (RTT) (49-77%) and idiopathic ASD (40-80%), but lower than in Williams syndrome (WS) (65-97%) (Shelton & Malow, 2021; Veatch et al., 2021). These figures are in contrast to the lower prevalence of sleep problems in children without NDDs, reported to be approximately 25% (Agar et al., 2021; Owens & Witmans, 2004; Trosman & Ivanenko, 2021). A meta-analysis of individuals with ID, including FXS (Surtees et al., 2018), supported differences in sleep duration and sleep quality when compared with typically developing children and adolescents (Trosman & Ivanenko, 2021). In a study involving the Fragile X Clinical and Research Consortium (FXCRC) (N=260, 198 males; age range: 0-55 years), whose pilot database served as basis for the Fragile X Online Registry With Accessible Research Database (FORWARD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was found in 7% of individuals with FXS (Kidd et al., 2014), a figure much lower than Down Syndrome (DS) (50-80%), PWS (45-80%), and RTT and Angelman syndrome (both ~60%) (Agar et al., 2021; Veatch et al., 2021), but higher than the 2-3.5% in young children without NDD (Trosman & Ivanenko, 2021) .

While no sex differences in frequency or type of sleep difficulties have been found in FXS (Richdale, 2009; Sadeh et al., 2002), developmental trajectories appear to differ by sex Kronk et al., 2010). Males tend to improve with age whereas sleep problems remain relatively stable in females. A recent study based on FORWARD data demonstrated a higher frequency of sleep difficulties in adolescents and young adults (n=199) with FXS and ASD than in their counterparts without ASD (41% in FXS+ASD vs. 16% in FXS only). The same study revealed that sleep difficulties were in fact quite frequent (36-41%) in children with FXS under 12 years regardless of their ASD status (Kaufmann et al., 2017). In terms of severity, sleep difficulties in children with FXS tend to be mild to moderate (88% in males; 41% mild, 47% moderate; 79% in females; 32% mild, 47% moderate) (Kronk et al., 2010). In support of their clinical impact, nearly half of individuals with FXS, especially males, were administered some form of medication as a sleep aid (Kronk et al., 2010; Weiskop et al., 2005). While drugs are recommended for the treatment of sleep problems in those with NDDs if behavioral interventions are unsuccessful, data on treatment of sleep difficulties in FXS are limited (Shelton & Malow, 2021). As in the general population, in NDDs sleep difficulties have been associated with a wide range of behavioral problems including symptoms of ASD in children with NDDs (Astill et al., 2012; Sadeh et al., 2002; Vriend et al., 2013; Mazurek & Sohl, 2016; Shelton & Malow, 2021; Trosman & Ivanenko, 2021). Moreover, sleep problems in ASD and DS showed bidirectional relationships with behavioral symptoms (Kamara & Beauchaine, 2020). Literature on behavioral problems and sleep difficulties in FXS is limited and inconsistent. Authors often describe behavioral problems, including hyperactivity and anxiety, as variations in clinical presentation as well as predictors of sleep problems in FXS (Kronk et al., 2010; Shelton & Malow, 2021). In terms of the impact of sleep difficulties on parents and caregivers of children with NDDs, including those FXS, a few studies have shown that parental stress levels are higher in affected families (Agar et al., 2021). For example, a study of 46 mothers and 50 children with NDDs indicated that more severe sleep and associated behavioral difficulties in affected children were significantly associated with disturbed sleep and increased depression, anxiety and stress levels in their mothers. Mothers' sleep disturbance was also found to significantly predict poor maternal psychological well-being (Chu & Richdale, 2009). Expanding these findings, a meta-analysis of 26 studies and 33 groups of individuals with NDDs, which included FXS, ASD, DS, and WS, revealed that a shorter night sleep duration was associated with increased daytime problem behaviors and greater parental stress (Surtees et al., 2018).

In order to address gaps in our knowledge of sleep difficulties in FXS, we conducted a large-scale survey of data from the nationwide clinic-based FORWARD project (Sherman et al., 2017). The analyses reported here intend to present an overview of sleep problems in individuals with FXS in a predominantly pediatric sample. We focused on determining the frequency and severity of sleep difficulties in FXS, as well as their impact on the affected individual (associated behavioral abnormalities) and their families.

2. METHODS

2.1. Editorial policies and ethical considerations

All clinic sites associated with the Fragile X Online Registry With Accessible Research Database (FORWARD) project had obtained local Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects standards. Informed consent was obtained from all parents of participants included in the study.

2.2. Study procedures

Analyses in this report were derived from FORWARD, a multisite clinic-based observational study initiated in 2012 (Liu et al., 2016; Sherman et al., 2017), with 26 FXS clinics providing data for the present study. The diagnosis of FXS was confirmed by review of a clinical genetic test report demonstrating an FMR1 full mutation. The present study included individuals with mosaicism. Baseline de-identified data from FORWARD version 3 included 1,071 individuals who had either a Clinician Report form and/or a Parent Report form. For analyses that required both clinician and parent data, data from a subset of subjects (n=706) was used. While the sample was predominantly pediatric, some young adults were also included as revealed in the age distribution. Individuals were evaluated between 2012-2015 and reported data on sleep problems corresponded to the time of initial assessment. Demographic variables, including age and sex, were collected on a separate Registry form. Table 1 depicts major demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants, including level of intellectual function and ASD status.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical features of the FXS sample

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (n=977) | 0-5 | 243 | 24.87 |

| 6-12 | 375 | 38.38 | |

| 13-18 | 198 | 20.27 | |

| 19+ | 161 | 16.48 | |

| Gender (n=1,070) | Male | 824 | 77.01 |

| Female | 246 | 22.99 | |

| ASD† (n=935) | Yes | 375 | 38.82 |

| No | 560 | 57.97 | |

| Intellectual disability (n=918) | Developmental delay (children under 6 years) | 112 | 12.20 |

| Borderline | 84 | 9.15 | |

| Mild | 205 | 22.33 | |

| Moderate to profound | 457 | 49.78 | |

| Level not specified | 60 | 6.54 | |

ASD, autism spectrum disorder ever diagnosed

Data collected from the Parent Report form included responses to questions about sleep difficulties, specifically severity and whether the sleep habit represented a Problem for the family (Yes/No, Table 2). Six sleep difficulties (sleep habits/problems) in the categories of physiological (Problems falling asleep; Frequent night-time awakening; Child seems tired in the morning), behavior-driven (Struggles at bedtime), and “other” (Grinds teeth, wets the bed, or appears restless; Loud snoring), were assessed. Severity of sleep difficulties was based on weekly frequency using three levels: Rarely (0-1 times per week), Sometimes (2-4 times per week) and Usually (≥ 5 times per week). In order to determine a clinical relevance of sleep problems and their severity, the aforementioned levels were re-labeled as ‘Absent’, “Present/Sometimes’, and ‘Present/Usually’, respectively, with the latter two considered as a clinically-relevant problem. All analyses were primarily conducted by comparing the “Absent’ category with the combined ‘Present’ categories. These were complemented by 3-way analyses comparing all three severity groups. Data on sleep apnea were obtained through both Parent Report and Clinician Report forms, with parents reporting any current or previous occurrence and response to treatment, and clinicians confirming presence (or absence) of sleep apnea as a co-morbid condition. In addition, we analyzed the relationship between presence of sleep problems and behavioral co-morbidities as recorded by clinicians.

Table 2.

Sleep difficulties in FXS: frequency, severity and impact on the family

| Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep difficulty | Absent | Problem for family |

||

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Problem falling asleep | 467 (60) | 99 (15.8) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.55 (8.5) | 9.4 (5.9) | ||

| Males (%) | 347/467 (74.3) | 79 (79.8) | ||

| Child struggles at bedtime | 594 (76.8) | 93 (14.9) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.7 (8.6) | 8.8 (7.1) | ||

| Males (%) | 451/594 (76.5) | 78 (83.9) | ||

| Frequent night-time awakenings | 499 (63.9) | 122 (19.9) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.3 (7.6) | 8.2 (7.1) | ||

| Males (%) | 383/499 (76.7) | 101 (82.8) | ||

| Child seems tired in the morning | 415 (54.5) | 87 (14.7) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.3 (8.6) | 9.73 (5.7) | ||

| Males (%) | 309/415 (74.5) | 73 (83.9) | ||

| Grinds teeth, wets the bed, restless | 465 (60.5) | 94 (15.6) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 12.7 (8.7) | 9.53 (5.8) | ||

| Males (%) | 353/465 (75.9) | 75 (79.8) | ||

| Child snores loudly | 538 (70.0) | 44 (7.4) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 11.2 (8.0) | 11.3 (7.8) | ||

| Males (%) | 395/538 (73.6) | 38 (86.4) | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P1, P value of two-way chi-quadrat square Absent vs. Present; P2, P value of three-way chi-quadrat square: Absent vs. Present Sometimes vs. Present Usually; **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses included tabulations of frequency and proportions for categorical variables and central tendency and dispersion measures for continuous variables (e.g., mean, SD). Tests used for group comparisons and for examining relationship between variables included Chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum and Student t-tests, and ANOVAs.

Given the pilot and descriptive nature of this work, significant group differences are reported at p<0.05, without correction for multiple comparisons, although findings at p≤0.01 are highlighted. Only data with valid values was used for all the analyses, which were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC) and online calculators (GraphPad, Social Science Statistics).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sleep difficulties: frequency, severity and impact on the family

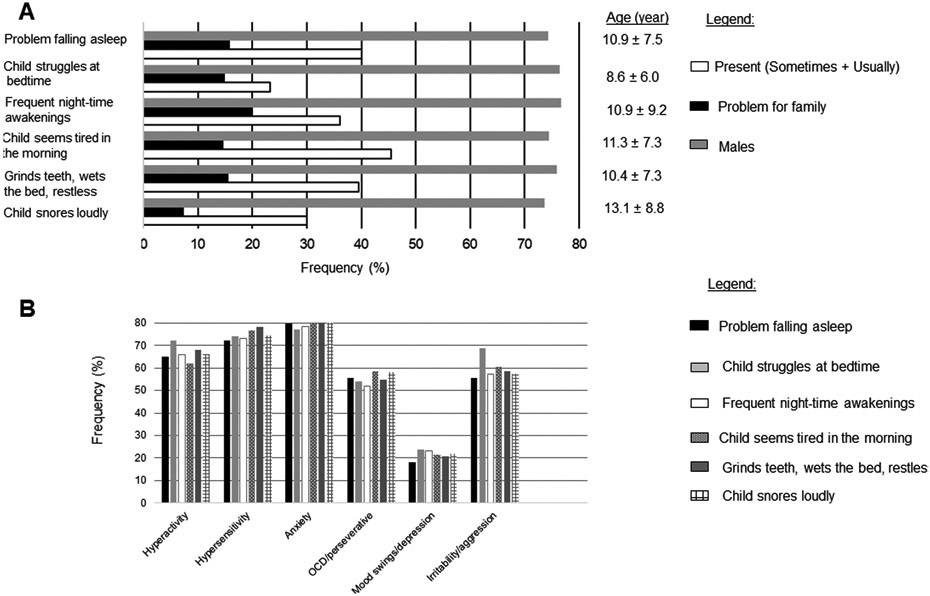

Of 1,071 individuals with Parent Report forms, 800 had information on sleep difficulties. Table 2 presents data on frequency, severity and impact divided by sex and age for this subset of 800 participants. Frequency (Present) of the 6 sleep problems ranged from 23.2% (Child struggles at bedtime) to 45.5% (Child seems tired in the morning), while the group with the greatest severity (Present/Usually) represented between 6.6% (Child struggles at bedtime) and 16.6% (Grinds teeth, wets the bed, or appears restless). Caregivers responding positively to the Problem for family question ranged from ~7% (Child snores loudly) to ~15-20%. For all 6 sleep difficulties, the group with highest severity (Present/Usually) was smaller than those with lower severity (Present/Sometimes). For three sleep difficulties (e.g., Problem falling asleep) the proportion of individuals for whom it was a problem for the family was comparable to or lower than the proportion of individuals for whom the sleep difficulty was reported as Present/Usually (i.e., impact comparable to greatest severity), while for other three sleep problems (e.g., Frequent night-time awakening) it was higher (i.e., impact higher than greatest severity). For 5 of the 6 sleep problems the Present group was significantly younger or comparable in age to the Absent group, whereas those with Child snores loudly (Present group) were significantly older than the Absent group. Three sleep problems (e.g., Problems falling asleep) showed a male predominance while for the other sleep difficulties sex distribution was proportional to the overall subject sample.

3.2. Sleep apnea profile

Data on obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) were collected for 706 participants through parent- and clinician-completed forms. According to parent report, 2.3% of individuals experienced OSA Present/Currently, 5.8% experienced OSA Present/In the past; 87.3% of individuals were reported not to have experienced OSA, and parents of 4.7% of parents did not know if OSA was present. Clinicians reported OSA Present/Currently in only 3.4% of individuals. These OSA frequency figures contrast with the frequency of Child snores loudly (30%) depicted in Table 2.

3.3. Relationship between sleep apnea and other sleep difficulties

We examined whether OSA, as recorded by clinicians, related to the severity of other sleep difficulties in the Parent Report (data not shown). Chi-square analyses showed significant association between sleep apnea and severe snoring (Child snores loudly Present/Usually, p=0.0003), as well marginally significant associations between OSA and Child seems tired in the morning Present/Usually or Frequent night-time awakening Present (all) (p=0.06 and p=0.074, respectively).

3.4. Relationship between sleep difficulties and problem behaviors

To assess the impact of sleep problems in individuals with FXS, we examined the relationship between sleep difficulties, as reported by parents, and behavioral problems, as identified by clinicians, in the participants described in section 3.1 (Table 3). We first evaluated the relationship between presence of a sleep difficulty and presence of a behavioral problem. All sleep problems were significantly associated with the presence of Irritability/aggression and, with the exception of Child seems tired in the morning, they were also significantly associated with Hyperactivity. A few sleep difficulties were statistically significant associated with the presence of Mood swings/depression (e.g., Frequent night-time awakening). Another relationship of interest was found between Child seems tired in the morning and Hypersensitivity. Of note, despite its high prevalence, Anxiety was only statistically significant associated with Child snores loudly. The same age and sex distribution profiles reported for each type of sleep difficulty (see Table 2) were evident in their association with behavioral problems. This is illustrated in Table 3 by the lower age, in most instances, of those individuals with co-occurring sleep and behavioral problems.

TABLE 3.

Sleep difficulties in FXS: relationship with behavioral abnormalities

| Attention problems |

Hyperactivity | Hypersensitivity | Anxiety | OCD/ perseverative |

Mood swings/depression |

Irritability/ aggression |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

N (%) | Mean age (±SD) |

||

| Problems falling asleep | absent | 327 (80.74) | 12.5 (7.71) | 224 (55.58) | 11.22 (7.24) | 284 (71.36) | 12.51 (8.52) | 332 (83.00) | 13.52 (8.69) | 215 (54.16) | 14.64 (9.66) | 73 (18.30) | 15.67 (9.94) | 186 (46.38) | 12.79 (8.76) |

| present | 211 (78.73) | 11.02 (7.28) | 173 (64.79) | 9.68 (6.16) | 191 (72.07) | 10.52 (6.89) | 215 (79.63) | 11.86 (7.49) | 147 (55.68) | 11.72 (7.68) | 48 (18.11) | 12.36 (8.31) | 147 (55.68) | 10.67 (6.71) | |

| p | 0.52 | 0.02* | 0.02* | 0.02* | 0.84 | 0.0053 * | 0.27 | 0.02* | 0.70 | 0.0015** | 0.95 | 0.05* | 0.02* | 0.01 * | |

| Frequent night-time awakenings | absent | 348 (81.12) | 12.43 (7.07) | 238 (55.74) | 10.98 (6.37) | 299 (70.52) | 12.26 (7.50) | 355 (83.33) | 13.11 (7.49) | 239 (56.50) | 13.47 (7.84) | 66 (15.57) | 14.45 (7.70) | 195 (46.10) | 12.4 (7.61) |

| present | 193 (78.77) | 10.86 (8.22) | 161 (65.98) | 9.82 (7.35) | 175 (73.22) | 10.85 (8.69) | 193 (78.45) | 12.38 (9.48) | 125 (51.87) | 13.43 (10.94 | 56 (23.24) | 14.23 (11.16) | 139 (57.20) | 10.92 (8.32) | |

| p | 0.46 | 0.03* | 0.01 * | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 0.01 * | 0.90 | 0.006** | 0.10 | |

| Child seems tired in the morning | absent | 287 (79.28) | 12.50 (8.19) | 205 (56.94) | 11.02 (7.29) | 238 (67.23) | 12.29 (8.41) | 285 (79.39) | 13.47 (8.58) | 184 (51.98) | 13.84 (9.39) | 54 (15.21) | 16.06 (10.04) | 148 (41.46) | 12.8 (8.31) |

| present | 241 (81.41) | 11.31 (6.96) | 183 (62.03) | 10.13 (6.53) | 225 (76.53) | 11.22 (7.56) | 251 (84.80) | 12.28 (7.98) | 171 (58.56) | 13.19 (8.87) | 63 (21.43) | 13.15 (8.98) | 177 (60.41) | 11.07 (7.76) | |

| p | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.01 * | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.04* | 0.10 | <0.00001** | 0.05* | |

| Child struggles at bedtime | absent | 402 (79.60) | 12.86 (7.90) | 273 (54.17) | 11.39 (7.22) | 350 (70.42) | 12.67 (8.33) | 417 (82.90) | 13.83 (8.58) | 272 (54.73) | 14.58 (9.50) | 82 (16.47) | 16.1 (10.22) | 219 (43.98) | 13.24 (8.54) |

| present | 132 (81.98) | 8.77 (5.47) | 120 (72.32) | 8.42 (5.34) | 117 (74.05) | 8.60 (5.87) | 124 (77.02) | 9.53 (6.23) | 85 (54.14) | 9.72 (6.13) | 38 (23.90) | 10.61 (6.26) | 110 (68.75) | 8.81 (5.76) | |

| p | 0.51 | 0.0001** | <0.00001 | 0.0001** | 0.77 | 0.0001** | 0.09 | 0.0001** | 0.90 | 0.0001** | 0.03* | 0.0005** | <0.00001** | 0.0001** | |

| Child snores loudly | absent | 369 (78.68) | 11.66 (7.45) | 266 (56.84) | 10.17 (6.56) | 324 (69.83) | 11.24 (7.51) | 373 (79.70) | 12.41 (7.98) | 247 (53.00) | 13.28 (8.85) | 79 (16.99) | 14.43 (10.11) | 216 (46.35) | 11.21 (7.29) |

| present | 163 (84.45) | 12.33 (7.87) | 126 (65.97) | 11.34 (7.54) | 139 (74.33) | 12.57 (8.87) | 166 (89.73) | 13.85 (8.95) | 107 (58.15) | 13.78 (9.60) | 41 (21.81) | 14.15 (8.20) | 108 (57.45) | 13.04 (9.26) | |

| p | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.03* | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.04* | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.15 | 0.87 | 0.01** | 0.07 | |

| Grinds teeth, wets the bed, appears restless | absent | 311 (78.34) | 13.03 (7.89) | 214 (53.90) | 11.86 (7.83) | 260 (66.50) | 12.76 (8.58) | 317 (80.25) | 14.02 (8.65) | 207 (53.08) | 14.88 (9.56) | 67 (17.18) | 15.95 (9.76) | 173 (44.36) | 13.31 (8.57) |

| present | 222 (83.15) | 10.37 (6.92) | 179 (67.80) | 8.97 (4.96) | 205 (78.24) | 10.22 (6.71) | 226 (84.64) | 11.19 (7.38) | 151 (54.63) | 11.45 (7.84) | 55 (20.75) | 12.39 (8.64) | 156 (58.65) | 10.24 (6.96) | |

| p | 0.13 | 0.0001** | 0.0004** | 0.0001** | 0.001** | 0.0004** | 0.15 | 0.0001** | 0.25 | 0.0002** | 0.25 | 0.03* | 0.0003** | 0.0004** | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; OCD, Obsessive–compulsive disorder. **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

Note: age in years

The aforementioned key findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of findings.

A. Frequency of sleep difficulties and their impact to families.

B. Frequency of behavioral abnormalities in each difficulty (Present) group.

Abbreviation: OCD- obsessive compulsive disorder

4. Discussion

We report here the first large-scale, clinic-based study of sleep difficulties in a predominantly pediatric sample of individuals with FXS. We examined their frequency, severity, relationship with behavioral problems, impact on the family, and associated factors (gender, age) in a sample from a clinic-based natural history study of FXS. Overall, sleep difficulties were moderately frequent, ranging from approximately 23% to 46%. On the other hand, approximately 25% of all children in the general population experience sleep problems at some point during childhood (Owens, 2008). Most sleep difficulties in our sample fell into the mild to moderate severity category, with 7-20% of individuals affected at a level considered a problem for the family. Severity of sleep problems was related to family impact; however, in a few instances (e.g., Frequent night-time awakening) the frequency of those reporting a problem for the family exceeded that of those in the severe sleep difficulty category. All sleep problems were significantly associated with the presence of irritability/aggression and several of them were also associated with hyperactivity but not with anxiety, a highly prevalent behavioral problem in FXS. While loud snoring was relatively frequent, only severe loud snoring was significantly associated with sleep apnea (Child snores loudly 30%, sleep apnea ~2-3%). With the exception of snoring, younger individuals were more commonly and more severely affected. A relatively higher proportion of males was found among those with Problems falling asleep and Child snores loudly. The data reported here could provide the foundation for studies of specific sleep difficulties and of prevention and management of sleep problems in FXS.

Sleep difficulties are recognized as a common and potentially impairing clinical manifestation in NDDs (Shelton & Malow, 2021). Estimates of frequency of sleep difficulties for a given NDD are highly variable due to different subject samples and methodologies of evaluation (e.g., community vs. clinic samples; ad hoc surveys vs. standardized questionnaires), with reported ranges between 20-80% (Shelton & Malow, 2021; Surtees et al., 2018; Veatch et al., 2021). The largest study to date in FXS, a parental survey of approximately 1,200 individuals, mainly children (mean age ~15 years), reported a 32% frequency of sleep difficulties without difference between sexes (Kronk et al., 2010). A previous study of a smaller sample of children with FXS (N=90) employing a standardized questionnaire, the widely used Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) (Owens et al., 2000), showed that 47% of participants had sleep problems at a level of clinical referral (Kronk et al., 2009). A third publication, analyzing a clinic-based sample from FORWARD’s foundational study, reported sleep problems in 27% of children again with no sex differences (Kidd et al., 2014). Although in the present investigation we did not estimate overall frequency of sleep problems, the 23-46% range for the 6 sleep difficulties under evaluation is in line with these previous studies of children with FXS. The main difference between the present study and previous ones is the relatively higher frequency of males with certain sleep problems, notably sleep onset insomnia (Problems falling asleep) and loud snoring (Child snores loudly). In terms of age distribution, we found that all sleep problems, with exception of loud snoring, tended to occur in younger children who were also overrepresented in the more severe (Present/Usually) subgroups. The abovementioned large parental survey also examined Problems with falling asleep and Frequent night-time awakenings, but did not find age differences (Kronk et al., 2010). These authors also reported higher percentages of children with Difficulty waking in morning and Daytime sleepiness, problems that were not included in our study, among those older than 15 years. The latter illustrates the challenges in interpreting data on prevalence and other features of sleep problems, when using ad hoc measures. Application of standardized instruments like the CSHQ offers the promise of approaching sleep difficulties in FXS with a ‘common language’. Indeed, a CSHQ profile similar to the one published by Kronk and colleagues (2009) was identified by Kidd et al. (2014), when the standardized instrument was applied to a small convenience sample (n=29) of their clinic-based cohort. Overall, the frequency of sleep problems in the predominantly pediatric FXS sample reported here is in line with previous studies of the disorder but in the lower end range among NDDs.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a severe condition with a well-established association to some disorders such as DA (Agar et al., 2021) and, more recently, to several other severe NDDs (Veatch et al., 2021). Kronk and colleagues (2009) reported a high prevalence of loud snoring and OSA, 38% and 34%, respectively. These figures were not confirmed by the clinic-based study reported by Kidd et al. (2014). In the latter OSA prevalence was 7%, in line with the present study (i.e., 2.3% by parent, 3.4% by clinician) and with most studies in the general pediatric population (0.2%-4.0%) (Lumeng & Chervin, 2008). We also found that 30% of individuals with FXS presented with loud snoring and that severe loud snoring strongly correlated with OSA and weakly with severe morning tiredness and frequent night-time awakenings. Thus, our data suggest that severe loud snoring is clinically meaningful since it is associated with OSA and other sleep problems. Our findings have implications for management guidelines of children with FXS, in that OSA may be underdiagnosed in FXS due to the difficulties in obtaining sleep studies in those patients with more problematic behavior (Kidd et al., 2014). It should also be considered that a higher proportion of those with less than severe snoring symptoms may actually have had OSA, especially if it was manifested as gasping rather than snoring (Myers et al., 2013). Since in the present study we did not have data on OSA in the past, we may also have missed patients who had OSA when young, prior to having had a tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (Boudewyns et al., 2017). Altogether, our OSA data suggest that greater vigilance may be needed in FXS clinics to properly diagnose OSA.

Considering the challenges in precisely determining frequency and severity of sleep difficulties in FXS (Agar et al., 2021; Kaufmann et al., 2017; Kidd et al., 2014), evaluating their relationship with other symptoms and the impact on caregiver and other family members may help to elucidate their clinical relevance. Most sleep difficulties were associated with irritability/aggression. Since the latter is one of the most problematic behavioral abnormalities in FXS, linked to an overall more severe phenotype (Budimirovic et al., 2020; Eckert et al., 2019; Kaufmann et al., 2017), presence of sleep problems in children with FXS should alert clinicians to identifying other clinically significant manifestations of the disorder. Additional associations between most sleep problems and hyperactivity underscore the behavioral implications of sleep difficulties in FXS. Interestingly, sleep problems were not associated with anxiety, attention problems, or hypersensitivity, three of the most prevalent and distinctive behavioral abnormalities in FXS. Our findings are in general agreement with studies of sleep difficulties in other NDDs, which demonstrate a link with behavioral problems. However, they do not confirm an association of sleep problems with ADHD or anxiety, as reported earlier in FXS (Kronk et al., 2010; Shelton & Malow, 2021). In fact, they support a more specific previously reported association between sleep problems, irritability/aggression, and ASD (Kaufmann et al., 2017). It is important to consider the link between anxiety and irritability in lower functioning individuals with FXS (49.8% moderate-profound intellectual disability) in this study, which is in line with the literature (Budimirovic et al., 2020) and may also explain the findings by Kronk and colleagues (2010). We evaluated the impact of sleep problems on the family through a simple Yes/No question. The range of positive responses was 7-20%, with the lowest figure corresponding to loud snoring. These percentages were approximately equivalent to the frequencies of severe sleep problems, with exception of Struggles at bedtime; Frequent night-time awakening; and Child seems tired in the morning, which showed higher frequency of impacted families than those reporting severe sleep difficulty. These data indicate that, depending on the type, even a milder sleep problem could affect the family’s quality of life.

Despite the strength of the reported data considering its sample size and expert assessment, this study presents several limitations. The cohort was clinic-based, which may have selected more affected individuals with FXS. Also, the information was collected cross-sectionally with ad hoc, not standardized instruments. The categorization of some items was problematic since there was no Absent/Lack of sleep problem option. Our decision to interpret the choice Rarely (0-1 time per week) as absence may have led to underestimating the frequency of sleep difficulties. Associations between different sleep difficulties or between sleep difficulties and behavioral problems do not establish causality nor demonstrate common pathophysiology. Therefore, caution is warranted in interpreting results. The study contemplated only 7 sleep problems and treatments were not evaluated. Thus, follow up investigations to expand the scope of the work presented here by including, among others, additional sleep problems, longitudinal data, and standardized instruments, are necessary to fully appreciate the clinical significance of sleep difficulties in FXS.

In summary, sleep problems in our large, predominantly pediatric, sample of individuals with FXS were moderate in frequency and relatively lower severity. However, when severe, they were clinically significant because of their association with serious behavioral problems and their impact on quality of life. Some sleep difficulties, even when relatively mild, were also problematic for the family. Younger children, particularly boys, were at higher risk of severe sleep problems. Loud snoring, when severe, usually in teenage boys, indicated a high risk for the relatively infrequent OSA. These data indicate that clinicians should attempt to identify sleep difficulties, particularly in young children with FXS; treat more aggressively severe sleep problems because of their impact on quality of life; and investigate OSA in older boys with severe snoring. Altogether, this information can serve as foundation for studies of specific sleep difficulties and of prevention and management of sleep problems in FXS, as well as for the development of practice guidelines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Work on this publication was supported by cooperative agreements #U01DD000231, #U19DD000753 and # U01DD001189, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services. We would like to thank everyone involved in FORWARD: patients, their families and team of FORWARD researchers. We especially acknowledge Hannah Jackson’s contribution, who assisted with the data preparation and completed multiple initial analysis, helped with sections of the manuscript, including relevant most recent references.

Abbreviations

- ASD

Autism Spectrum Disorder

- FMR1

the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene

- FMRP

Fragile X mental retardation protein

- FORWARD

Fragile X Online Registry with Accessible Research Database

- FXS

fragile X syndrome

- IDD

intellectual and developmental disability

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- WASO

wake time after sleep onset

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dejan B. Budimirovic has received funding from Seaside, Roche, Neuren, Pfizer, Shire, Lundbeck, Forest, Sunovion, SyneuRX, Alcobra, Akili, Medgenics, Purdue, Supernus as a main sub-investigator, and from Ovid and Zynerba Pharmaceuticals as a principal investigator on clinical trials. He also consulted on clinical trial outcome measures (Seaside, Ovid). All the above funding has been directed to Kennedy Krieger Institute/the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions; DBB receives no personal funds and the Institute has no relevant financial interest in any of the commercial entities listed. Elizabeth Berry-Kravis has received funding from Acadia, Alcobra, AMO, Asuragen, BioMarin, Cydan, Fulcrum, GeneTx, GW, Ionis, Lumos, Marinus, Neuren, Neurotrope, Novartis, Ovid,Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Ultragenyx, Vtesse/Sucampo/Mallinckrodt, Yamo, and Zynerba Pharmaceuticals to consult on clinical trial design, run clinical trials, or develop testing standards or biomarkers, all of which is directed to RUMC in support of rare disease programs; E.B.-K. receives no personal funds, and RUMC has no relevant financial interest in any of the commercial entities listed. Walter E. Kaufmann is Chief Medical Officer of Anavex Life Sciences Corp. He has been a consultant to AveXis, EryDel, GW, Marinus, Neuren, Newron, Ovid, Stalicla, and Zynerba. Currently, WEK does not receive personal funds and has no financial interest in any of these commercial entities. The other co-authors declare that they have no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- Agar G, Brown C, Sutherland D, Coulborn S, Oliver C, & Richards C (2021). Sleep disorders in rare genetic syndromes: a meta-analysis of prevalence and profile. Mol Autism, 12(1), 18. doi: 10.1186/s13229-021-00426-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astill RG, Van der Heijden KB, Van Ijzendoorn MH, & Van Someren EJ (2012). Sleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzed. Psychol Bull, 138(6), 1109–1138. doi: 10.1037/a0028204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudewyns A, Abel F, Alexopoulos E, Evangelisti M, Kaditis A, Miano S, … Verhulst SL (2017). Adenotonsillectomy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: Is it enough? Pediatr Pulmonol, 52(5), 699–709. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budimirovic B, Haas-Givler B, Blitz R, Esler A, Kaufmann W, Sudhalter V, … Berry-Kravis E (2014. (updated 2020)). Understanding autism spectrum disorders in fragile X syndrome. Retrieved from https://fragilex.org/our-research/treatment-recommendations/understanding-asd-fxs/ [Google Scholar]

- Budimirovic B, Schlageter A, Filipovic-Sadic S, Protic DD, Bram E, Mahone EM, … Latham GJ (2020). A Genotype-Phenotype Study of High-Resolution FMR1 Nucleic Acid and Protein Analyses in Fragile X Patients with Neurobehavioral Assessments. Brain Sci, 10(10). doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, & Richdale AL (2009). Sleep quality and psychological wellbeing in mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil, 30(6), 1512–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert EM, Dominick KC, Pedapati EV, Wink LK, Shaffer RC, Andrews H, … Erickson CA (2019). Pharmacologic Interventions for Irritability, Aggression, Agitation and Self-Injurious Behavior in Fragile X Syndrome: An Initial Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord, 49(11), 4595–4602. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04173-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, & Hagerman PJ (2008). Testing for fragile X gene mutations throughout the life span. JAMA, 300(20), 2419–2421. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, & Polussa J (2015). Treatment of the psychiatric problems associated with fragile X syndrome. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 28(2), 107–112. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez RN, Feinberg RL, Vaurio R, Passanante NM, Thompson RE, & Kaufmann WE (2009). Autism spectrum disorder in fragile X syndrome: a longitudinal evaluation. Am J Med Genet A, 149A(6), 1125–1137. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, Kim E, Fotheringham I, & Leal J (2014). Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet A, 164A(7), 1648–1658. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamara D, & Beauchaine TP (2020). A Review of Sleep Disturbances among Infants and Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Rev J Autism Dev Disord, 7(3), 278–294. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00193-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Abrams MT, Chen W, & Reiss AL (1999). Genotype, molecular phenotype, and cognitive phenotype: correlations in fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet, 83(4), 286–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Kidd SA, Andrews HF, Budimirovic DB, Esler A, Haas-Givler B, … Berry-Kravis E (2017). Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome: Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment. Pediatrics, 139(Suppl 3), S194–S206. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1159F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SA, Lachiewicz A, Barbouth D, Blitz RK, Delahunty C, McBrien D, … Berry-Kravis E (2014). Fragile X syndrome: a review of associated medical problems. Pediatrics, 134(5), 995–1005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Hessl D, Randol JL, Espinal GM, Schneider A, Protic D, … Hagerman PJ (2019). Association between IQ and FMR1 protein (FMRP) across the spectrum of CGG repeat expansions. PLoS One, 14(12), e0226811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronk R, Bishop EE, Raspa M, Bickel JO, Mandel DA, & Bailey DB Jr. (2010). Prevalence, nature, and correlates of sleep problems among children with fragile X syndrome based on a large scale parent survey. Sleep, 33(5), 679–687. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronk R, Dahl R, & Noll R (2009). Caregiver reports of sleep problems on a convenience sample of children with fragile X syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil, 114(6), 383–392. doi: 10.1352/1944-7588-114.6.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JA, Hagerman RJ, Miller RM, Craft LT, Finucane B, Tartaglia N, … Cohen J (2016). Clinicians' experiences with the fragile X clinical and research consortium. Am J Med Genet A, 170(12), 3138–3143. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch DZ, Huggins RM, & Hagerman RJ (2004). Phenotypic variation and FMRP levels in fragile X. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev, 10(1), 31–41. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, & Chervin RD (2008). Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 5(2), 242–252. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-135MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow BA, Marzec ML, McGrew SG, Wang L, Henderson LM, & Stone WL (2006). Characterizing sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders: a multidimensional approach. Sleep, 29(12), 1563–1571. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, & Sohl K (2016). Sleep and Behavioral Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 46(6), 1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KA, Mrkobrada M, & Simel DL (2013). Does this patient have obstructive sleep apnea?: The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA, 310(7), 731–741. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA (2008). Classification and epidemiology of childhood sleep disorders. Prim Care, 35(3), 533–546, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Spirito A, & McGuinn M (2000). The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep, 23(8), 1043–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA & Witmans M (2004). Sleep problems. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 34(4), 154–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richdale AL (2009). A descriptive analysis of sleep behaviour in children with Fragile X. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 28(2), 135–144. doi: 10.1080/1366825031000147076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, & Raviv A (2002). Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev, 73(2), 405–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton AR, & Malow B (2021). Neurodevelopmental Disorders Commonly Presenting with Sleep Disturbances. Neurotherapeutics. doi: 10.1007/s13311-020-00982-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SL, Kidd SA, Riley C, Berry-Kravis E, Andrews HF, Miller RM, … Brown WT (2017). FORWARD: A Registry and Longitudinal Clinical Database to Study Fragile X Syndrome. Pediatrics, 139(Suppl 3), S183–S193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1159E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees ADR, Oliver C, Jones CA, Evans DL, & Richards C (2018). Sleep duration and sleep quality in people with and without intellectual disability: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev, 40, 135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons FJ, Byiers BJ, Raspa M, Bishop E, & Bailey DB (2010). Self-injurious behavior and fragile X syndrome: findings from the national fragile X survey. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil, 115(6), 473–481. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-115.6.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Iong KP, Tong TH, Lo J, Gane LW, Berry-Kravis E, … Hagerman RJ (2012). FMR1 CGG allele size and prevalence ascertained through newborn screening in the United States. Genome Med, 4(12), 100. doi: 10.1186/gm401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosman I, & Ivanenko A (2021). Classification and Epidemiology of Sleep Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 30(1), 47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veatch OJ, Malow BA, Lee H-S, Knight A, Barrish JO, Neul JL, … Glaze DG (2021). Evaluating Sleep Disturbances in Children With Rare Genetic Neurodevelopmental Syndromes. Pediatr Neurol, 123, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriend JL, Davidson FD, Corkum PV, Rusak B, Chambers CT, & McLaughlin EN (2013). Manipulating sleep duration alters emotional functioning and cognitive performance in children. J Pediatr Psychol, 38(10), 1058–1069. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskop S, Richdale A, & Matthews J (2005). Behavioural treatment to reduce sleep problems in children with autism or fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol, 47(2), 94–104. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.