Abstract

Men historically consume more meat than women, show fewer intentions to reduce meat consumption, and are underrepresented among vegans and vegetarians. Eating meat strongly aligns with normative masculinities, decisively affirming that “real men” eat meat and subordinating men who choose to be veg*n (vegan or vegetarian). The emergence of meat alternatives and increasing environmental concerns may contest these long-standing masculine norms and hierarchies. The current scoping review addresses the research question what are the connections between masculinities and men’s attitudes and behaviors toward meat consumption and veg*nism? Using keywords derived from two key concepts, “men” and “meat,” 39 articles were selected and analyzed to inductively derive three thematic findings; (a) Meat as Masculine, (b) Veg*n Men as Othered, and (c) Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity. Meat as Masculine included how men’s gendered identities, defenses, and physicalities were entwined with meat consumption. Veg*n Men as Othered explored the social and cultural challenges faced by men who adopt meatless diets, including perceptions of emasculation. Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity was claimed by men who eschewed meat in their diets and advocated for veg*nism as legitimate masculine capital through linkages to physical strength, rationality, self-determination, courage, and discipline. In light of the growing concern about the ecological impact of meat production and the adverse health outcomes associated with its excessive consumption, this review summarizes empirical connections between masculinities and the consumption of meat to consider directions for future men’s health promotion research, policy, and practice.

Keywords: masculinity, meat, plant-based diet, vegetarian, vegan

Introduction

Food takes the foremost position in the hierarchy of human needs, as the agricultural sector commands a substantial role in the global economy (Belasco & Scranton, 2014). However, the livestock industry in particular contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions (Clark & Tilman, 2017; Lacroix, 2018; Leip et al., 2015). Within this context, there is growing consensus that transitioning toward a more plant-based diet would benefit the climate, public health, and animal welfare (Aiking, 2011; Anomaly, 2015; Mehrabi et al., 2020; NCDs, 2015; Pluhar, 2010; Willett et al., 2019). Historically across many countries, men eat more meat than women (Beardsworth & Bryman, 1999; Gossard & York, 2003; Kiefer et al., 2005; Liebman et al., 2003; O’Doherty Jensen & Holm, 1999; Pfeiler & Egloff, 2018; Prättälä et al., 2007; Roos et al., 1998), show fewer intentions to reduce their meat consumption (Nakagawa & Hart, 2019), and are underrepresented among veg*ns 1 (Browarnik, 2012; Trocchia & Janda, 2003). In terms of gendered dimensions, meat has been portrayed as a symbol of manhood, power, and virility (Adams, 1994) to the extent that men’s alignments to masculine norms can moderate their meat consumption (De Backer et al., 2020) across the life course (Ritzel & Mann, 2021). The current scoping review, in addressing the research question what are the connections between masculinities and men’s attitudes and behaviors toward meat consumption and veg*nism? considers directions for future health promotion research, policy, and practice.

For industrialized nations to reach climate targets, current meat consumption patterns will need to undergo substantial change (Lacroix, 2018; Mehrabi et al., 2020). In addition to environmental concerns, current levels of meat consumption have been linked to negative health outcomes (NCDs, 2015; Willett et al., 2019) while the production of meat raises ethical concerns over animal welfare (Anomaly, 2015; Pluhar, 2010). That said, global meat consumption is rapidly increasing (Whitnall & Pitts, 2019), and consumers indicate little interest in reducing their consumption (Sanchez-Sabate & Sabaté, 2019). While some consumers in developed countries indicate their intent to eat less meat (Latvala et al., 2012) amid white meat replacing a significant amount of red meat consumption (Zeng et al., 2019), overall consumption levels have not decreased (Tobler et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2019). Indeed, while consumer awareness, attitudes, and intentions toward meat may be changing, their actual dietary behaviors are not (Dagevos & Verbeke, 2022; Richardson et al., 1993). Even consumers who decide to eliminate animal products from their diets often return to consuming them (Asher et al., 2014).

Sex differences have been used to explain men’s higher meat consumption. For example, men show less activation of empathy-related brain regions than women when they are exposed to animal and human suffering (Proverbio et al., 2009). The gendered dimensions of men’s meat consumption align with normative masculinities, affirming that “real men eat meat” (Schösler et al., 2015), and many men situate a meal without meat as not being a “real” meal (Sobal, 2005). Men also have more negative views of veg*ns than women, especially with regard to men who do not eat meat—a subgroup they [dis]regard as outsiders (Kildal & Syse, 2017), weak (Minson & Monin, 2012), and unmasculine (Ruby & Heine, 2011). The gender comparison and meat consumption research has presented differences wherein women report more negative feelings about meat than men (Kubberød et al., 2002) and dissociate themselves from their reasons for eating meat, while men tend to deny animal suffering and justify their consumption (Rothgerber, 2013). Meat-eating men are less likely than women to be concerned with the environment (Rosenfeld, 2020) and more highly value security and conformity (Hayley et al., 2015). These men tend to endorse social hierarchies (Allen et al., 2000), dominance over nature (Rothgerber, 2013), and exhibit more Machiavellian traits (Mertens et al., 2020). It has been suggested that as long as meat and masculinity are closely linked, effectively reducing consumption will be challenging (De Backer et al., 2020; Kildal & Syse, 2017).

One promising avenue to reduce meat eating is shifting consumption toward meat alternatives, which have the potential for improving men’s health (Chriki & Hocquette, 2020; Hu et al., 2019; Sadler, 2004), as well as environmental outcomes (Lynch & Pierrehumbert, 2019; Post, 2012; Tuomisto & Teixeira De Mattos, 2011), and animal welfare (Sexton et al., 2019). However, early research indicates that consumption of plant-based meat alternatives is low (Hagmann et al., 2019; Siegrist & Hartmann, 2019) and that many men harbor negative attitudes toward such foods (Michel et al., 2021). This reticence may be influenced by food neophobia (Bryant & Dillard, 2019; Hoek et al., 2011)—the aversion to try new foods (Pliner & Hobden, 1992)—wherein alternatives (Barton et al., 2020; Birch et al., 2018; Hartmann et al., 2015; Hoek et al., 2011; Onwezen et al., 2021) including cultivated meat (Wilks et al., 2019), meat that is grown through stem cell technology (Post, 2012), is of little interest.

While the literature reiterates strong connections between normative masculinity and meat consumption, the gendered dimensions of men’s uptake of meat alternatives are poorly understood, as the authors of a 2022 study noted their research was “the first study to explore male attitudes toward plant-based alternatives” (Bogueva et al., 2022, p. 3), while interventions to promote reduced meat consumption have been gender blind (Kwasny et al., 2022). The current scoping review summarizes empirical connections between masculinities and the consumption of meat and attitudes toward the notions of reducing consumption and/or consuming alternatives to thoughtfully consider directions for future men’s health promotion research, policy, and practice.

Methods

The decision to complete a scoping review was based on the heterogeneous nature of studies examining masculinities and attitudes and behaviors toward meat consumption. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), the scoping review included (a) articulating a research question, (b) developing a search strategy, (c) screening retrieved studies, (d) extracting and tabulating data from the included studies, and (e) summarizing the results. As per Levac et al.’s (2010) recommendation, thematic analysis was used to offer inductively derived thematic findings.

Search Strategy

The research question what are the connections between masculinities and men’s attitudes and behaviors toward meat consumption and veg*nism? was developed in recognizing masculinities as socially constructed norms, behaviors, and expectations associated with men that operate relationally within temporal, cultural, and locale specificities (Connell, 2013). As the article centers on the meat-masculinity nexus and those who refrain from meat consumption, the term veg*nism was employed inclusively to encompass all individuals abstaining from meat consumption. A search using keywords derived from “men” and “meat” (masculinit* OR gender identit* OR gender role* AND Meat* OR Vegan* OR Vegetarian*) was conducted on May 17, 2023 in seven databases: Embase, Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, Women’s Studies International, CAB Direct, and PsycINFO Ovid. No year range was set and the oldest retrieved study in the database was published in 1977.

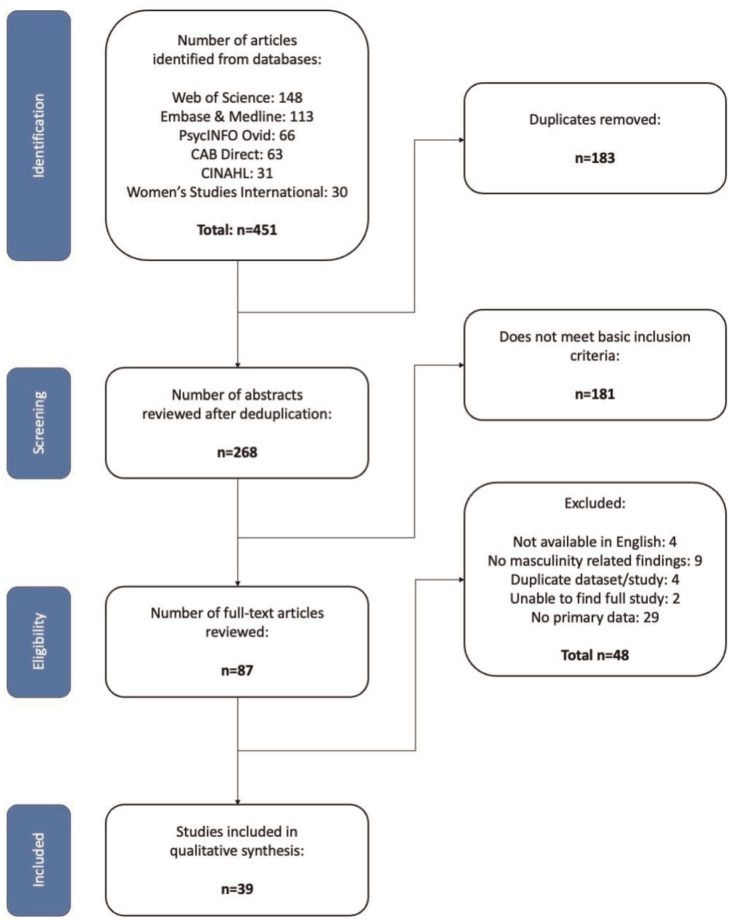

Using Covidence, studies reporting primary data findings regarding men’s meat consumption were included, and studies were excluded if they were not available in English or if the full-text article was unavailable. To ensure screening accuracy, a second researcher (NG) independently reviewed the retrieved articles, and discrepancies, disagreements, and findings were discussed to reach consensus. Through abstract screening studies were included if they focused on perceptions, beliefs, behaviors, or attitudes about men’s meat eating, meat alternatives, and/or the adoption of veg*nism relating to masculinity (please see Figure 1: Flow Diagram for retrieval details).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Data Extraction and Analysis

Nearly all studies were conducted in Western contexts and most focused on younger adults, with just three study samples comprising respondents with an average age of >40 years-old. Fourteen studies were conducted with male only samples, while 25 had a mixed gender sample. Studies utilized qualitative (n = 17), quantitative (n = 18) and mixed methods (n = 4) designs. Included studies were published between 2011 and 2023. Each article was read in full, and data were extracted and charted (please see Table 1: Study Characteristics). In charting each study, descriptive categories were formulated to organize the data and develop preliminary interpretations. As the specificities were compared across studies, tentative categories and themes were derived, under which patterns were discerned and developed with the writing up of each of the thematic findings; (1) Meat as Masculine, (2) Veg*n Men as Othered, and (3) Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity. Meat as Masculine included how men’s gendered identities and physicalities were idealized in the preparation and/or consumption of meat. Veg*n Men as Othered included risks to men who adopted meatless diets including emasculation and being perceived as weak. Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity was characterized by men who unashamedly eschewed meat in their diets and advocated for veg*nism as a legitimate embodiment of manly values.

Table 1.

Overview of Included Studies

| Author, year | Journal | Method | Data collection | Research aim | Themes | Subtheme findings | Veg* | Male | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aavik & Velgan (2021) | American Journal of Men’s Health | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore vegan men’s food practices in relation to health and well-being and the links between veganism and masculinity | VaCM | Veg*nism as healthy; Veg*nism as rational; Veg*nism as self-determination | ✓ | ✓ | Europe—Finland, Estonia |

| Bogueva & Marinova (2020) | Frontiers in Nutrition | Mixed methods | Surveys | To examine perceptions and opinions about cultured meat of young adults | MaM | Meat alternatives as threat to masculinity; Meat sensory properties as masculine; Barbequing meat as masculine | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Bogueva et al. (2017) | Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics | Mixed methods | Surveys | To find out what motivates meat consumers to consume meat and explore the opportunities of social marketing to counteract this | MaM | Meat as physical strength; Meat sensory properties as masculine | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Bogueva et al. (2020) | Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment | Mixed methods | Surveys | To examine the power of the current food discourse and social constraints imposed on vegetarian men | MaM; VMaO; VaCM | Meat as physical strength; Veg*n men seen as emasculated; Veg*n men seen as weird; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*n men as socially rejected; Veg*nism as courageous | ✓ | Oceania—Australia | |

| Bogueva et al. (2022) | Sustainability | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore the acceptance of meat alternatives by meat-loving men who visited a vegan restaurant and ate a plant-based burger | MaM | Meat alternatives as threat to masculinity | ✓ | Oceania—Australia | |

| Brookes & Chałupnik (2022) | Discourse, Context & Media | Qualitative | Discourse analysis | To examine discourse representations of men in a large online vegan community | VaCM | Veg*nism as physical strength; Veg*nism as rational; Veg*nism as self-determination; Veg*nism as courageous; Veg*nism as toughness | ✓ | International | |

| Carroll et al. (2019) | American Journal of Men’s Health | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore the influential drivers on young Australian blue- and white-collar men’s eating habits | MaM | Barbequing meat as masculine | ✓ | Oceania—Australia | |

| Çınar et al. (2021) | Appetite | Quantitative | Surveys—FNS; TMFS | To demonstrate that food neophobia varies across meat and plant dimensions and validate a measure of meat and plant neophobia | MaM | Masculinity associated with meat neophobia | International—United States, the Netherlands | ||

| De Backer et al. (2020) | Appetite | Quantitative | Surveys—ATVS; NMI; MAQ | To investigate if newer forms of masculinity can predict differences in meat consumption and attitudes toward vegetarians among men | MaM; VaCM | Masculinity associated with higher meat consumption/lower willingness to reduce consumption; Masculinity associated with lower willingness to consider veg*nism; Nontraditional masculinity associated with more positive attitudes toward vegetarians | ✓ | Europe—Belgium | |

| DeLessio-Parson (2017) | Gender, Place & Culture | Qualitative | Interviews | To investigate how vegetarian men and women experience social resistance and disrupt gender and culture | VMaO; VaCM | Veg*n men seen as weird; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*n men as socially rejected; Veg*nism as rational | ✓ | South America—Argentina | |

| Fidolini (2022) | Food, Culture & Society | Qualitative | Interviews | To examine how men regard their food practices as a core activity to prevent or cure illness and delaying the aging process | VMaO; VaCM | Veg*n men seen as weak; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*n men as socially rejected; Veg*nism as healthy; Veg*nism as physical strength; Veg*nism as self-determination; Veg*nism as courageous; Veg*nism as toughness | ✓ | Europe—France, Italy | |

| Graziani et al. (2021) | Sex Roles | Quantitative | Experiments—IAT | To examine preschool children’s explicit and implicit food-gender stereotypes and their stereotypical food likings | MaM | Masculinity associated with meat | Europe—Italy | ||

| Greenebaum & Dexter (2018) | Journal of Gender Studies | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore the experiences and viewpoints of vegan men in relation to patriarchal and hegemonic masculinity | VaCM | Veg*nism as healthy; Veg*nism as physical strength; Influence of veg*n male role models; Veg*nism as courageous; Veg*nism as toughness | ✓ | ✓ | North America—United States |

| Johnston et al. (2021) | Poetics | Qualitative | Interviews | To investigate the gendered conceptualization of prototypical meat-eaters and vegetarians | MaM; VMaO | Meat as physical strength; Veg*n men seen as emasculated; Veg*n men seen as weak | North America—Canada | ||

| Kakoschke et al. (2022) | Current Psychology | Quantitative | Surveys—PNSRI | To identify motivational profiles of veg*n males and test whether these differ on dimensions of masculinity and femininity | VaCM | Veg*n men masculine self-concept | ✓ | ✓ | International |

| Kelly & Ciclitira (2011) | Journal of Gender Studies | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore issues regarding the eating and drinking habits of young Irish men living in the United Kingdom | MaM | Masculinity associated with meat | ✓ | Europe—United Kingdom | |

| Khara et al. (2021) | Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | Qualitative | Interviews; Participant observation | To explore meat-eating practices of young urban Australians to identify the key drivers and barriers to adopt plant-based eating | VMaO | Veg*n men seen as emasculated | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Kildal & Syse (2017) | Appetite | Qualitative | Interviews | To explore Norwegian soldiers’ attitudes to the military’s meat reduction practice and reducing meat consumption | MaM; VMaO | Meat as physical strength; Veg*n men seen as weird | Europe—Norway | ||

| Leary et al. (2023) | Frontiers in Nutrition | Quantitative | Surveys; Masculinity threat—TMFS; NMI; MGRDS | To integrate literature on masculinity stress with research on goal conflict to examine preferences for plant-based meat alternatives | MaM | Masculinity stress associated with meat consumption; Masculine framing alternative meat | North America—United States, Canada | ||

| Love & Sulikowski (2018) | Frontiers in Psychology | Quantitative | Experiments; Surveys—IAT | To measure implicit and explicit attitudes toward meat in men and women | MaM | Meat as physical strength | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Mertens & Oberhoff (2023) | Food Quality and Preference | Quantitative | Surveys; Masculinity threat—BSRI | To investigate the relationship between sex, sex role identification, and meat-eating justification through gender identity threat | MaM | Masculinity associated with direct meat consumption strategies | Europe—Germany | ||

| Mesler et al. (2022) | Appetite | Quantitative | Surveys—TMFS; MGRDS | To explore the effects of masculinity stress on red meat consumption | MaM | Masculinity stress associated with meat consumption | International—United Kingdom, United States, Canada | ||

| Mycek (2018) | Food and Foodways | Qualitative | Interviews | To understand how vegetarian and vegan men conceptualize their plant-based diets in relation to their broader identity practices | VMaO; VaCM | Veg*n men seen as emasculated; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*nism as healthy; Veg*nism as rational; Veg*nism as self-determination | ✓ | ✓ | North America—United States |

| Nath (2011) | Journal of Sociology | Qualitative | Interviews | To investigate the impact of hegemonic masculinity on men’s adoption of meatless diets | MaM; VMaO | Meat as physical strength; Barbequing meat as masculine; Veg*n men seen as weird; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*n men as socially rejected | ✓ | ✓ | Oceania—Australia |

| Oliver (2023) | Social Movement Studies | Qualitative | Interviews; Discourse analysis | To explore two vegan masculine narratives; the redemption and progressive masculinity narrative | VaCM | Veg*nism as physical strength; Veg*nism as courageous | ✓ | ✓ | Europe—United Kingdom |

| Peeters et al. (2022) | Food, Culture & Society | Quantitative | Surveys—TMFS; NMI | To investigate meat consumption behavior and how this is related to gender identity and new masculinity norms | MaM | Masculinity associated with higher meat consumption/lower willingness to reduce consumption | International—United Kingdom, United States | ||

| Pohlmann (2014) | Dissertation University of Hawai’i | Quantitative | Surveys; Experiments—PAQ; GITGKQ | To demonstrate that men express higher preference for meat compared with women | MaM | Masculinity threat increased men’s intended meat consumption; Masculinity associated with meat | North America—United States | ||

| Pohlmann (2022) | Appetite | Quantitative | Surveys; Masculinity threat; Experiments—GITGKQ | To investigate the effects of interhuman as well as interspecies compassion appeals on food choice using masculinity threats | MaM | Masculinity threat reduced likelihood to opt for alternative meat | North America—United States | ||

| Ritzel & Mann (2021) | Foods | Quantitative | Surveys | To identify the gender meat bias across stages of human life by applying a multiple-group regression across seven age classes | MaM | Masculinity associated with higher meat consumption/lower willingness to reduce consumption | North America—United States | ||

| Rothgerber (2013) | Psychology of Men & Masculinity | Mixed methods | Surveys; Interviews—MRNS | To explore what strategies men and women use to justify meat eating | MaM | Masculinity associated with higher meat consumption/lower willingness to reduce consumption; Masculinity associated with direct meat consumption strategies | North America—United States | ||

| Ruby & Heine (2011) | Appetite | Quantitative | Vignettes | To investigate people’s perceptions of others who follow omnivorous and vegetarian diets | VMaO | Veg*n men seen as less masculine | North America—Canada | ||

| Schösler et al. (2015) | Appetite | Quantitative | Surveys | To investigate whether the link between meat consumption and framings of masculinity may hinder reduced meat consumption | MaM | Meat-masculinity link culturally influenced | Europe—Netherlands | ||

| Sogari et al. (2019) | Agriculture | Qualitative | Surveys | To explore attitudes of younger Australians toward edible insects | MaM | Meat sensory properties as masculine; Meat as physical strength; Meat alternatives as threat to masculinity | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Stanley et al. (2023) | Sex Roles | Quantitative | Surveys—TMFS | To explore the extent to which self-rated gender typicality explains differences in meat consumption intentions and behavior | MaM | Masculinity associated with higher meat consumption/lower willingness to reduce consumption; Masculinity associated with lower willingness to consider veg*nism; Masculinity associated with endorsing 4Ns | Oceania—Australia | ||

| Thomas (2016) | Appetite | Quantitative | Vignettes | To replicate and extend research on the link between masculinity and vegetarianism | VMaO | Veg*n men seen as less masculine | North America—United States | ||

| Timeo & Suitner (2017) | Psychology of Men & Masculinity | Quantitative | Vignettes—ATVS | To investigate the link between meat consumption and masculine gender role norms | MaM; VMaO | Masculinity associated with meat; Veg*n men seen as less masculine; Veg*n men seen as less attractive | Europe—Italy | ||

| Unsain et al. (2020) | Appetite | Qualitative | Ethnography; Surveys; Interviews | To describe food preferences and eating practices of gay bears in Brazil and their relations to masculinity | MaM; VMaO | Meat sensory properties as masculine; Meat as physical strength; Barbequing meat as masculine; Veg*n men seen as less masculine | ✓ | South America—Brazil | |

| Van Der Horst et al. (2023) | Appetite | Qualitative | Interviews | To investigate male athletes’ perceptions of mixed and plant-based diets | MaM; VMaO; VaCM | Meat as physical strength; Disapproval of veg*n men; Veg*nism as healthy; Veg*nism as physical strength; Influence of veg*n male role models; Veg*nism as courageous; Veg*nism as toughness | ✓ | Europe | |

| Weber & Kollmayer (2022) | Sustainability | Quantitative | Surveys—PNSRI | To understand why some people decide to stop consuming animal products while others do not | VaCM | Veg*n men masculine self-concept | International |

ATVS = Attitudes Toward Vegetarians Scale; BSRI = Bem’s Sex Role Inventory; FNS = Food Neophobia Scale; GITGKQ = Gender Identity Threat, Gender Knowledge Questionnaire; IAT = Implicit Association Test; MaM = Meat as Masculine; MAQ = Meat Attachment Questionnaire; MGRDS = Masculine Gender Role Discrepancy Stress; MRNS = 26-item Male Role Norms Scale; NMI = New Masculine Inventory; PAQ = Personal Attributes Questionnaire; PNSRI = Positive-Negative Sex-Role Inventory; TMFS = Traditional Masculinity-Femininity Scale; VaCM = Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity; VMaO = Veg*n Men as Othered; Veg* = fully veg*n sample; Male = fully male sample.

Results

Theme 1: Meat as Masculine

The most heavily weighted theme was Meat as Masculine, wherein explicit connections were made between gender and men’s meat consumption. Twenty-seven of the 39 studies connected the research design and/or findings to socially constructed masculinities. Eighteen quantitative and mixed-methods studies (Bogueva et al., 2020, 2017; Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Çınar et al., 2021; De Backer et al., 2020; Graziani et al., 2021; Leary et al., 2023; Love & Sulikowski, 2018; Mertens & Oberhoff, 2023; Mesler et al., 2022; Peeters et al., 2022; Pohlmann, 2014, 2022; Ritzel & Mann, 2021; Rothgerber, 2013; Schösler et al., 2015; Stanley et al., 2023; Timeo & Suitner, 2017) and nine qualitative studies included masculinity as a thematic finding (Bogueva et al., 2022; Carroll et al., 2019; Johnston et al., 2021; Kelly & Ciclitira, 2011; Kildal & Syse, 2017; Nath, 2011; Sogari et al., 2019; Unsain et al., 2020; Van Der Horst et al., 2023).

Among quantitative studies, several scales to measure masculinity were used (Bem, 1974; Kachel et al., 2016; Kaplan et al., 2017; Spence et al., 1974; Thompson & Pleck, 1970). Specific details can be found in Table 1. Self-reported adherence to idealized masculinities was linked to higher self-reported meat consumption and/or lower willingness to reduce consumption (De Backer et al., 2020; Peeters et al., 2022; Rothgerber, 2013; Stanley et al., 2023), the use of “direct” meat consumption strategies (endorsing pro-meat attitudes as distinct from “indirect” strategies such as dissociation) (Mertens & Oberhoff, 2023; Rothgerber, 2013), unwillingness to consider veg*nism (De Backer et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2023), higher meat neophobia (fear of alternative meat products) (Çınar et al., 2021), and endorsing “the 4 Ns” (Piazza et al., 2015): meat as natural, normal, necessary, and nice (Stanley et al., 2023). The strength of the meat-masculinity relationship was reported to be culturally contingent, with Schösler et al. (2015) indicating significant variation across ethnic groups in the Netherlands.

Three studies (Mertens & Oberhoff, 2023; Pohlmann, 2014, 2022) utilized masculinity threat manipulations, wherein men completed surveys assessing “masculine” knowledge and, regardless of their actual performance, were informed that they scored significantly below average, aiming to elicit a sense of “threat” to masculinity and influence their subsequent behavior (Bosson et al., 2013; Schmitt & Branscombe, 2001). This was reported to increase men’s intended meat consumption (Pohlmann, 2014) and reduce the likelihood of choosing plant-based meat jerky (Pohlmann, 2022). One study, however, identified no such relationship (Mertens & Oberhoff, 2023). Two studies (Leary et al., 2023; Mesler et al., 2022) used a masculinity stress measure (Reidy et al., 2016), which directly assesses men’s feelings of masculinity compared with societal norms and their distress arising from any perceived disparity. Men experiencing such stress were more likely to Google search red meat and less likely to search for meat alternatives, and were more likely to consume plant-based meat when it was positioned as masculine (Leary et al., 2023). Masculinity stress also increased the likelihood that men chose red meat options over salad, and exposure to information that red meat was surging in popularity influenced men to pay more for meat (Mesler et al., 2022).

Meat consumption was reported to increase in the “masculinity intensifying stages” of men’s lives during adolescence and early adulthood (age 12-35), peak during midlife and mature adulthood (age 36-65), before decreasing in old age (age 65-80) (Ritzel & Mann, 2021). In two studies, preschool children associated masculine faces with images of meat (Graziani et al., 2021) and kindergarten age boys associated meat with men and expressed preferences for masculine foods (Graziani et al., 2021). Men linked the words “meat” and “healthy” significantly more often than women (Love & Sulikowski, 2018), associated meat-based pizza toppings with masculinity (Pohlmann, 2014), and were more likely to choose meat-based dishes in a restaurant setting if they associated vegetarianism with femininity (Timeo & Suitner, 2017). Whereas using photos to prime compassion—images depicting men engaging in acts of care and protection toward animals, such as gently holding them—decreased women’s intent to consume meat, it increased that of men (Pohlmann, 2022).

Qualitative findings linked the sensory properties of meat to masculinity including the “blood” of meat (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Bogueva et al., 2017; Sogari et al., 2019), its masculine smell (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Sogari et al., 2019; Unsain et al., 2020), and the primal ripping of meat from bones with one’s teeth (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020). Meat was consistently positioned as providing men power, strength, protein, and muscle (Bogueva et al., 2017, 2020; Johnston et al., 2021; Kildal & Syse, 2017; Nath, 2011; Sogari et al., 2019; Unsain et al., 2020; Van Der Horst et al., 2023). Connections between masculinities and the preparation of meat also consistently linked the barbeque as a manly, macho pursuit, and the “epitome” of masculinity (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Carroll et al., 2019; Nath, 2011; Unsain et al., 2020). The value of freedom—to eat what a man desires—also featured (Bogueva et al., 2022; Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Carroll et al., 2019), with studies describing plant-based burgers as a “symbol of eliminated freedom” (Bogueva et al., 2022) and cultured meats and alternative proteins as threats to masculinity (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Sogari et al., 2019). Calls for reduced meat consumption were predicted as potentially ineffective and even counterproductive among men (Carroll et al., 2019). Meat was regarded and reinforced as a manly choice (Bogueva & Marinova, 2020; Kelly & Ciclitira, 2011) with affirmations that “real men eat meat” (Bogueva et al., 2017, 2020).

Theme 2: Veg*n Men as Othered

The second most common theme was Veg*n Men as Othered, which focused on the negative perceptions held and/or expressed about veg*n men. Thirteen of the 39 studies were designed to and/or inductively derived discrete findings to explain how veg*n men were “othered.” This included four quantitative and mixed methods studies (Bogueva et al., 2020; Ruby & Heine, 2011; Thomas, 2016; Timeo & Suitner, 2017) and nine qualitative studies (DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Fidolini, 2022; Johnston et al., 2021; Khara et al., 2021; Kildal & Syse, 2017; Mycek, 2018; Nath, 2011; Unsain et al., 2020; Van Der Horst et al., 2023). It is important to note that the “othering” of veg*n men is marked by emasculation and social exclusion, distinct from the systemic oppression faced by historically marginalized groups that is characterized by pervasive obstacles to fundamental societal resources and opportunities.

Three quantitative and mixed-method studies utilized vignettes (Ruby & Heine, 2011; Thomas, 2016; Timeo & Suitner, 2017), wherein one sample cohort read vignettes featuring individuals adhering to an omnivorous diet, while another group read identical vignettes with the only difference being that the dietary preference was adjusted to veg*n. The participants were then asked to rate the target on traits such as virtue (Ruby & Heine, 2011), health-consciousness (Thomas, 2016), and attractiveness (Timeo & Suitner, 2017), in addition to their perceived masculinity. Two of these studies reported that both men and women perceived vegetarian men as less masculine than omnivorous men (Ruby & Heine, 2011; Timeo & Suitner, 2017). While one study identified no difference between vegetarian and omnivorous men, they reported that vegan men were regarded as less masculine than both omnivorous and vegetarian men, particularly those who ate vegan by choice (Thomas, 2016). In addition, the perceived lack of masculinity among vegetarian men was reported to reduce their attractiveness to women (Timeo & Suitner, 2017).

Using the Attitudes Toward Vegetarians scale (Chin et al., 2002), vegetarianism was associated more with femininity than masculinity by both men and women (Timeo & Suitner, 2017). Bogueva et al. (2020) reported high levels of intolerance and resentment toward veg*ns and the use of derogatory language to question their heterosexual orientation, as well as comments about veg*n men being emaciated and broader references to being “un-Australian,” “strange,” and a “disappointment” to masculine meat-eating men.

Qualitative studies explored non-veg*n men’s perceptions of men who eschewed meat (Johnston et al., 2021; Khara et al., 2021; Kildal & Syse, 2017; Unsain et al., 2020) and/or veg*n men’s experiences of discrimination (DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Fidolini, 2022; Mycek, 2018; Nath, 2011; Van Der Horst et al., 2023). Non-veg*n men described veg*n men as thin, physically weak, lacking muscle, and feminine (Johnston et al., 2021), using derogatory language in several studies (Khara et al., 2021; Unsain et al., 2020). The link between homosexuality and masculinity was made (Mycek, 2018; Nath, 2011; Unsain et al., 2020) and veg*n men were positioned as outsiders (Bogueva et al., 2020; DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Kildal & Syse, 2017; Nath, 2011).

Veg*n men expressed that they had their masculinity and physical prowess questioned (Nath, 2011) and that others regarded them as weak for not consuming meat (Fidolini, 2022). Veg*n men frequently mentioned experiences of other men’s disapproval (Bogueva et al., 2020; DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Fidolini, 2022; Mycek, 2018; Nath, 2011). A common theme was veg*n men struggling with belongingness in relationships with family and friends (DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Fidolini, 2022; Nath, 2011), as one study reported athletes in team sports dismissing vegan team members (Van Der Horst et al., 2023) and another identified meat-eating men avoiding being associated with veg*n men (Bogueva et al., 2020).

Theme 3: Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity

Twelve of the 39 studies were included in Veg*nism as Contemporary Masculinity, a theme characterized by contextualizing and negotiating veg*nism as a masculine practice, challenging the traditional association of masculinity with meat and disrupting manly dietary norms and behaviors. Four of these studies used quantitative or mixed methods (Bogueva et al., 2020; De Backer et al., 2020; Kakoschke et al., 2022; Weber & Kollmayer, 2022) and eight used qualitative designs (Aavik & Velgan, 2021; Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Fidolini, 2022; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Mycek, 2018; Oliver, 2023; Van Der Horst et al., 2023).

Two quantitative studies (Kakoschke et al., 2022; Weber & Kollmayer, 2022) analyzed veg*n men’s gendered self-concepts (Berger & Krahé, 2013) and reported that vegan men scored higher in positive femininity, but described themselves as no less masculine than omnivores. Weber and Kollmayer (2022) further delineated that vegetarian men scored lower on positive masculinity than their vegan counterparts, and that vegans ascribed fewer negative masculine attributes to themselves than omnivores. One study (De Backer et al., 2020) indicated that men who identified more strongly with progressive forms of masculinity (Kaplan et al., 2017) had more positive attitudes toward veg*ns, as another noted that younger Australian men were more likely to admire the “bravery” of veg*n men for adopting their dietary practices despite stigmatization (Bogueva et al., 2020).

Among qualitative studies, veg*n men questioned the traditional tenets of masculinity and meat eating in two studies (Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Oliver, 2023), describing rigid gendered practices as “passe” (Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018). However, instead of integrating traditionally feminine values such as care or compassion, it was more common for men to justify their veg*nism by framing it within the context of traditional masculinity, emphasizing ideals such as physical strength, rationality, and self-determination—one study described this as veg*n men “redoing” gender more than “undoing” it (Mycek, 2018).

Many veg*n men focused on the health benefits of veg*nism (Aavik & Velgan, 2021; Fidolini, 2022; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Mycek, 2018; Van Der Horst et al., 2023), emphasizing maintaining or gaining muscle and/or strength (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; Fidolini, 2022; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Oliver, 2023). Veg*n men doubted the need for animal protein for physical strength (Van Der Horst et al., 2023) and some emphasized that they could still consume unhealthy junk foods (Aavik & Velgan, 2021), while others claimed that veg*nism led to hormonal changes such as higher testosterone, more body hair, and curative effects for erectile dysfunction (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022). The importance of role models was also highlighted in two studies wherein men spoke to the impact of well-known veg*n male athletes (Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Van Der Horst et al., 2023). Indeed, one study noted that athletes with plant-based diets were regarded positively by their peers, which was associated with their perceived “determination, discipline and rationality” (Van Der Horst et al., 2023). Another study noted that men’s veg*nism was deemed acceptable by men when it was for either religious or health reasons (Bogueva et al., 2020).

Veg*n men strongly emphasized rationality in several studies, where they described their choice to become veg*n as entirely rational—a distinctly non-emotional decision that was driven by experts and/or scientific evidence (Aavik & Velgan, 2021; Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; DeLessio-Parson, 2017; Mycek, 2018). Self-determination was also mentioned and linked to values of autonomy and independence, with some men explaining that veg*nism gave them a sense of control over their lives, health, and the alignment between their values and behavior (Aavik & Velgan, 2021; Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; Fidolini, 2022; Mycek, 2018). In one study veg*nism was framed as a rebellious act in which men were not “going along with the crowd” (Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018). Veg*n men spoke about courage in standing up for their beliefs despite stigma and emphasized their protector role in sticking up for animals who cannot defend themselves (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Oliver, 2023). They reformulated meat-eating as a behavior that communicates weakness rather than strength (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; DeLessio-Parson, 2017) and constructed veg*nism as a sign of willpower, discipline, toughness, and determination (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; Fidolini, 2022; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Van Der Horst et al., 2023).

Veg*n men feeling the need to justify their decision within the context of masculinity was common throughout the studies, often due to experiencing stigmas. In three studies men spoke to hypermasculine activities such as fighting, shooting guns, and/or asserting their sexual prowess (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022; Fidolini, 2022; Oliver, 2023). Men also used masculine redemption narratives, such as an influencer portraying himself as having transitioned from being a dangerous criminal to becoming a veg*n (Oliver, 2023). Rejecting masculine norms was reported in two studies of veg*n men; one noted men showing a lack of care about achieving and maintaining a muscular body, problematizing the notion that men need to be physically strong (Aavik & Velgan, 2021), and another mentioned men discussing the negative aspects of masculinity and positive aspects of femininity (Brookes & Chałupnik, 2022).

Discussion

The scoping review findings confirm intricate relationships between masculinity, meat consumption, and veg*nism to reveal gendered dimensions that both rely on and disrupt deeply ingrained societal norms. While a significant body of research has linked the meat-masculinity nexus in traditional hunter-gatherer and pastoral societies to historically gendered divisions of labor (Bliege Bird & Bird, 2008; Eerkens & Bartelink, 2013; Leroy & Praet, 2015; Lowassa et al., 2012; Talle, 1990), the empirical literature on the “real men eat meat” phenomenon in Western society is relatively recent. Indeed, the studies included in this analysis were published in the last 12 years.

The current review findings reveal the meat-masculinity link as contested rather than monolithic in contemporary Western society. Central are the tensions between two opposing constructs: meat consumption as emblematic of masculinity and veg*nism as a burgeoning symbol of progressive manhood. Challenging the norms central to meat consumption, some veg*n men might be best understood as carving their own contemporary masculinity spaces. Yet, as noted here and in previous research (Sumpter, 2015), many veg*n men were apologetic, concealing, and/or conflicted in their public alignments to hegemonic masculinity, as they attempted to negotiate their dietary practices with traditional tenets of masculinity, rather than embodying traditionally feminine values such as compassion.

Men who could justify their veg*nism for health reasons faced less criticism than those opting to do so for moral reasons (Aavik & Velgan, 2021; Bogueva et al., 2020), which reflects existing research on the social attractiveness of veg*ns (De Groeve et al., 2022). Veg*n male athletes were positively viewed by their peers due to their perceived discipline and determination (Van Der Horst et al., 2023), lending support to suggestions that men who have established their masculinity in one domain may feel less pressured to adhere strictly to other traditional masculine norms, such as their diet (De Visser & Smith, 2006). In addition, as previously reported (MacInnis & Hodson, 2017), those adopting veg*n diets for religious reasons faced less scrutiny as well (Bogueva et al., 2020). Central to meat and veg*nism jockeying for masculine capital were traditional hegemonic discourses rendering veg*n men weak and emasculated, with some being complicit in sustaining, and others protesting, the subordinating effects of traditional gendered practices and powerplays. These prevailing masculine structures may hinder the promotion of plant-based diets and partially explain the relatively modest success of previous attempts to encourage sustainable eating (Modlinska et al., 2020).

Only three studies (Bogueva et al., 2022; Leary et al., 2023; Sogari et al., 2019) spoke to men’s perceptions of meat alternatives, highlighting threats to masculinity (Bogueva et al., 2022), eliminated manhood (Sogari et al., 2019), and the importance of masculine framing (Leary et al., 2023). It was noted that calls for reducing meat consumption or switching to alternatives may provoke reactance among men (Carroll et al., 2019). The commercial determinants of health play a significant role here, wherein advertising that reinforces meat and meat eating as synonymous with masculinity beckons the primal masculine essence to sustain those practices (Buerkle, 2009; Rogers, 2008). Similarly, popular TV shows promote the meat as masculine narrative by encouraging men’s preoccupation with barbeques and meat (Veri & Liberti, 2013) and reinforcing the notion that men should not be emotionally concerned for farmed animals (Parry, 2010). In addition, consuming meat serves as a direct response to refute social movements that challenge traditional masculinity (Calvert, 2014).

Although research indicates that plant-based alternatives are more accepted than cultivated meat (Onwezen et al., 2021), consumers with high meat consumption—by and large men—are more receptive to cultivated meat and are less open to other alternatives (Circus & Robison, 2018; de Boer et al., 2013; Onwezen et al., 2021). Since men tend to evaluate food in terms of taste and satiety more so than health, cultivated meat may meet the needs of male consumers (Lee et al., 2020; Post, 2012). Indeed, it has been suggested that mimicking the taste and texture of meat are the most important considerations to make meat alternatives more popular (Caputo et al., 2023; Michel et al., 2021). However, it must be noted that the ethical, environmental, and health benefits of cultivated meat have been questioned (Chriki & Hocquette, 2020), with criticisms about simplifying the complex issue of sustainable and ethical food production into binary oppositions of technology versus nature. Risked here is the perpetuation of existing power imbalances rather than addressing the root causes of unethical meat consumption (Abrell, 2023; Broad, 2020; Humbird, 2020). Since men frequently mention that they regard meat as essential sustenance for their bodies (Fiddes, 2004), it will be important for future research to more closely study the health effects of alternative meats, as these insights are crucial for their uptake (Santo et al., 2020; Toh et al., 2022).

This study has several limitations. Mainly, as a scoping review, appraisal of the included studies was not conducted to assess the quality of evidence. In addition, this study grouped vegetarians and vegans together to report the findings, despite their attitudinal and behavioral diversities (Rosenfeld, 2019), which may influence perceptions of and alignments to masculinities. Importantly, the study is restricted by its reliance on White Western samples. As meat-masculinity is deeply influenced by culture (Schösler et al., 2015) and the growth rate in meat production is significantly higher in non-Western countries (Ritchie et al., 2017), future research might benefit by broadening its view to examine these connections in diverse cultural contexts to delineate discrete patterns in and across specific male subgroups, particularly among those that are less privileged. It should be noted that the relative importance of masculinity in men’s decisions surrounding meat consumption and veg*nism is difficult to ascertain, as masculinity sits among broader factors that influence men’s dietary practices such as affordability, availability, and perceptions of processed foods (Machín et al., 2017).

So far, interventions to reduce meat consumption have given little attention to the effects of gender (Kwasny et al., 2022). It is important for future interventions to be tailored and to positively frame meat alternatives (Bryant & Dillard, 2019) to target men’s behavior change (Creighton & Oliffe, 2010; Singleton, 2008; Sloan et al., 2010). It has been suggested that showing male vegetarians who fit masculine ideals (Funk et al., 2020) may help lever normative sustained changes for meat-eating men (Michel et al., 2021). However, considering that this approach could inadvertently reinforce negative stereotypes, it is critical to thoughtfully examine how such portrayals can be balanced to avoid perpetuating harmful masculine norms. In addition, advocating for a more inclusive and flexible masculinity has been suggested as a potential means to reduce meat consumption (Salmen & Dhont, 2023), where incorporating insights on reactance will be essential to ensure efforts are well-received.

This review has illustrated the contested nature of the meat-masculinity link in Western society. Men’s dietary choices, especially when based on ethical considerations, often conflict with societal expectations, leading to a complex relationship with food and gender identity. Their choices, influenced by health, environmental, and moral concerns, face varying levels of scrutiny, revealing underlying societal biases relating to masculinity. The study also points out the challenges faced by meat alternatives in gaining acceptance among men and underscores the importance of understanding these gendered dynamics in promoting sustainable dietary choices and creating interventions to reduce meat consumption.

Acknowledgments

E.L. was supported by a Tier 2 Principal’s Research Chair program in Social Innovation for Health Equity and Food Security. P.S. was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship and Michael Smith Health Research BC Research Trainee Award. J.L.O. was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Men’s Health Promotion.

Veg*n(ism) includes both vegan(ism) and vegetarian(ism).

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Rob Velzeboer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2596-9427

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2596-9427

Paul Sharp  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5616-3181

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5616-3181

John L. Oliffe  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9029-4003

References

- Aavik K., Velgan M. (2021). Vegan men’s food and health practices: A recipe for a more health-conscious masculinity? American Journal of Men’s Health, 15(5), 15579883211044323. 10.1177/15579883211044323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrell E. (2023). The empty promises of cultured meat. In Adams C. J., Crary A., Gruen L. (Eds.), The good it promises, the harm it does: Critical essays on effective altruism (pp. 149–C10P30). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780197655696.003.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams C. J. (1994). The sexual politics of meat. In Jaggar A. M. (Ed.), Living with contradictions (pp. 548–557). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Aiking H. (2011). Future protein supply. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 22(2), 112–120. 10.1016/j.tifs.2010.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. W., Wilson M., Ng S. H., Dunne M. (2000). Values and beliefs of vegetarians and omnivores. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(4), 405–422. 10.1080/00224540009600481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anomaly J. (2015). What’s wrong with factory farming? Public Health Ethics, 8(3), 246–254. 10.1093/phe/phu001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asher K., Green C., Gutbrod H., Jewell M., Hale G., Bastian B. (2014). Study of current and former vegetarians and vegans. Veg*n Advocacy. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/sm_vegn/1 [Google Scholar]

- Barton A., Richardson C. D., McSweeney M. B. (2020). Consumer attitudes toward entomophagy before and after evaluating cricket (Acheta domesticus)-based protein powders. Journal of Food Science, 85(3), 781–788. 10.1111/1750-3841.15043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsworth A., Bryman A. (1999). Meat consumption and vegetarianism among young adults in the UK: An empirical study. British Food Journal, 101(4), 289–300. 10.1108/00070709910272169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belasco W., Scranton P. (2014). Food nations: Selling taste in consumer societies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bem S. L. (1974). Bem Sex Role Inventory. 10.1037/t00748-000 [DOI]

- Berger A., Krahé B. (2013). Negative attributes are gendered too: Conceptualizing and measuring positive and negative facets of sex-role identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(6), 516–531. 10.1002/ejsp.1970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birch D., Skallerud K., Paul N. A. (2018). Who are the future seaweed consumers in a Western society? Insights from Australia. British Food Journal, 121(2), 603–615. 10.1108/BFJ-03-2018-0189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bliege Bird R., Bird D. (2008). Why women hunt: Risk and contemporary foraging in a Western Desert Aboriginal community. Current Anthropology, 49, 655–693. 10.1086/587700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogueva D., Marinova D. (2020). Cultured meat and Australia’s Generation Z. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7, Article 148. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2020.00148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogueva D., Marinova D., Bryant C. (2022). Meat me halfway: Sydney meat-loving men’s restaurant experience with alternative plant-based proteins. Sustainability, 14(3), Article 1290. 10.3390/su14031290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogueva D., Marinova D., Gordon R. (2020). Who needs to solve the vegetarian men dilemma? Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(1), 28–53. 10.1080/10911359.2019.1664966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogueva D., Marinova D., Raphaely T. (2017). Reducing meat consumption: The case for social marketing. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 29(3), 477–500. 10.1108/APJML-08-2016-0139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson J., Vandello J., Caswell T. A. (2013). Precarious manhood. In Ryan M. K., Branscombe N. R. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and psychology (pp. 115–130). Sage. 10.4135/9781446269930.n8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broad G. M. (2020). Making meat, better: The metaphors of plant-based and cell-based meat innovation. Environmental Communication, 14(7), 919–932. 10.1080/17524032.2020.1725085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes G., Chałupnik M. (2022). ‘Real men grill vegetables, not dead animals’: Discourse representations of men in an online vegan community. Discourse, Context & Media, 49, 100640. 10.1016/j.dcm.2022.100640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browarnik B. (2012). Attitudes toward male vegetarians: Challenging gender norms through food choices. Psychology Honors Papers. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/psychhp/25

- Bryant C., Dillard C. (2019). The impact of framing on acceptance of cultured Meat. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, Article 103. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2019.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerkle C. W. (2009). Metrosexuality can stuff it: Beef consumption as (heteromasculine) fortification. Text and Performance Quarterly, 29(1), 77–93. 10.1080/10462930802514370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert A. (2014). You are what you (m)eat: Explorations of meat-eating, masculinity and masquerade. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 16(1), Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo V., Sogari G., Van Loo E. J. (2023). Do plant-based and blend meat alternatives taste like meat? A combined sensory and choice experiment study. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 45(1), 86–105. 10.1002/aepp.13247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J.-A., Capel E. M., Gallegos D. (2019). Meat, masculinity, and health for the “typical Aussie bloke”: A social constructivist analysis of class, gender, and consumption. American Journal of Men’s Health, 13(6), 1557988319885561. 10.1177/1557988319885561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M. G., Fisak B., Sims V. K. (2002). Development of the Attitudes Toward Vegetarians Scale. Anthrozoös, 15(4), 332–342. 10.2752/089279302786992441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chriki S., Hocquette J.-F. (2020). The myth of cultured meat: A review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7, Article 7. 10.3389/fnut.2020.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Çınar Ç., Karinen A. K., Tybur J. M. (2021). The multidimensional nature of food neophobia. Appetite, 162, 105177. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circus V. E., Robison R. (2018). Exploring perceptions of sustainable proteins and meat attachment. British Food Journal, 121(2), 533–545. 10.1108/BFJ-01-2018-0025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M., Tilman D. (2017). Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environmental Research Letters, 12(6), 064016. 10.1088/1748-9326/aa6cd5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. (2013). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton G., Oliffe J. (2010). Theorising masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociology Review, 19, 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos H., Verbeke W. (2022). Meat consumption and flexitarianism in the Low Countries. Meat Science, 192, 108894. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer C., Erreygers S., De Cort C., Vandermoere F., Dhoest A., Vrinten J., Van Bauwel S. (2020). Meat and masculinities. Can differences in masculinity predict meat consumption, intentions to reduce meat and attitudes towards vegetarians? Appetite, 147, Article 104559. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J., Schösler H., Boersema J. J. (2013). Motivational differences in food orientation and the choice of snacks made from lentils, locusts, seaweed or “hybrid” meat. Food Quality and Preference, 28(1), 32–35. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Groeve B., Rosenfeld D. L., Bleys B., Hudders L. (2022). Moralistic stereotyping of vegans: The role of dietary motivation and advocacy status. Appetite, 174, 106006. 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLessio-Parson A. (2017). Doing vegetarianism to destabilize the meat-masculinity nexus in La Plata, Argentina*. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(12), 1729–1748. 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1395822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Visser R., Smith J. A. (2006). Mister in-between: A case study of masculine identity and health-related behaviour. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(5), 685–695. 10.1177/1359105306066624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eerkens J. W., Bartelink E. J. (2013). Sex-biased weaning and early childhood diet among middle holocene hunter–gatherers in Central California. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 152(4), 471–483. 10.1002/ajpa.22384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiddes N. (2004). Meat: A natural symbol. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203168141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fidolini V. (2022). Eating like a man. Food, masculinities and self-care behavior. Food, Culture & Society, 25(2), 254–267. 10.1080/15528014.2021.1882795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funk A., Sütterlin B., Siegrist M. (2020). The stereotypes attributed to hosts when they offer an environmentally-friendly vegetarian versus a meat menu. Journal of Cleaner Production, 250, 119508. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gossard M. H., York R. (2003). Social structural influences on meat consumption. Human Ecology Review, 10(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Graziani A. R., Guidetti M., Cavazza N. (2021). Food for boys and food for girls: Do preschool children hold gender stereotypes about food? Sex Roles, 84(7), 491–502. 10.1007/s11199-020-01182-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenebaum J., Dexter B. (2018). Vegan men and hybrid masculinity. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(6), 637–648. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1287064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann D., Siegrist M., Hartmann C. (2019). Meat avoidance: Motives, alternative proteins and diet quality in a sample of Swiss consumers. Public Health Nutrition, 22(13), 2448–2459. 10.1017/S1368980019001277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C., Shi J., Giusto A., Siegrist M. (2015). The psychology of eating insects: A cross-cultural comparison between Germany and China. Food Quality and Preference, 44, 148–156. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley A., Zinkiewicz L., Hardiman K. (2015). Values, attitudes, and frequency of meat consumption. Predicting meat-reduced diet in Australians. Appetite, 84, 98–106. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek A. C., Luning P. A., Weijzen P., Engels W., Kok F. J., de Graaf C. (2011). Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person- and product-related factors in consumer acceptance. Appetite, 56(3), 662–673. 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F. B., Otis B. O., McCarthy G. (2019). Can plant-based meat alternatives be part of a healthy and sustainable diet? Journal of the American Medical Association, 322(16), 1547–1548. 10.1001/jama.2019.13187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbird D. (2020). Scale-up economics for cultured meat: Techno-economic analysis and due diligence. Engineering Archive. 10.31224/osf.io/795su [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J., Baumann S., Oleschuk M. (2021). Capturing inequality and action in prototypes: The case of meat-eating and vegetarianism. Poetics, 87, 101530. 10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kachel S., Steffens M. C., Niedlich C. (2016). Traditional masculinity and femininity: Validation of a new scale assessing gender roles. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 956. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakoschke K. C., Hale M.-L., Sischka P. E., Melzer A. (2022). Meatless masculinity: Examining profiles of male veg*n eating motives and their relation to gendered self-concepts. Current Psychology, 42, 29851–29867. 10.1007/s12144-022-03998-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D., Rosenmann A., Shuhendler S. (2017). What about nontraditional masculinities? Toward a quantitative model of therapeutic New Masculinity Ideology. Men and Masculinities, 20(4), 393–426. 10.1177/1097184X16634797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A., Ciclitira K. (2011). Eating and drinking habits of young London-based Irish men: A qualitative study. Journal of Gender Studies, 20, 223–235. 10.1080/09589236.2011.593322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khara T., Riedy C., Ruby M. B. (2021). The evolution of urban Australian meat-eating practices. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, Article 624288. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2021.624288 [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer I., Rathmanner T., Kunze M. (2005). Eating and dieting differences in men and women. The Journal of Men’s Health and Gender, 2(2), 194–201. 10.1016/j.jmhg.2005.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kildal C. L., Syse K. L. (2017). Meat and masculinity in the Norwegian Armed Forces. Appetite, 112, 69–77. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubberød E., Ueland Ø., Tronstad Å., Risvik E. (2002). Attitudes towards meat and meat-eating among adolescents in Norway: A qualitative study. Appetite, 38(1), 53–62. 10.1006/appe.2002.0458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwasny T., Dobernig K., Riefler P. (2022). Towards reduced meat consumption: A systematic literature review of intervention effectiveness, 2001–2019. Appetite, 168, 105739. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix K. (2018). Comparing the relative mitigation potential of individual pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 195, 1398–1407. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala T., Niva M., Mäkelä J., Pouta E., Heikkilä J., Kotro J., Forsman-Hugg S. (2012). Diversifying meat consumption patterns: Consumers’ self-reported past behaviour and intentions for change. Meat Science, 92(1), 71–77. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary R. B., MacDonnell Mesler R., Montford W. J., Chernishenko J. (2023). This meat or that alternative? How masculinity stress influences food choice when goals are conflicted. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, Article 1111681. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1111681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. J., Yong H. I., Kim M., Choi Y.-S., Jo C. (2020). Status of meat alternatives and their potential role in the future meat market—A review. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 33(10), 1533–1543. 10.5713/ajas.20.0419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leip A., Billen G., Garnier J., Grizzetti B., Lassaletta L., Reis S., Simpson D., Sutton M. A., Vries W., de Weiss F., Westhoek H. (2015). Impacts of European livestock production: Nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus and greenhouse gas emissions, land-use, water eutrophication and biodiversity. Environmental Research Letters, 10(11), 115004. 10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/115004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy F., Praet I. (2015). Meat traditions. The co-evolution of humans and meat. Appetite, 90, 200–211. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman M., Propst K., Moore S. A., Pelican S., Holmes B., Wardlaw M. K., Melcher L. M., Harker J. C., Dennee P. M., Dunnagan T. (2003). Gender differences in selected dietary intakes and eating behaviors in rural communities in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Nutrition Research, 23(8), 991–1002. 10.1016/S0271-5317(03)00080-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Love H. J., Sulikowski D. (2018). Of meat and men: Sex differences in implicit and explicit attitudes toward meat. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 559. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowassa A., Tadie D., Fischer A. (2012). On the role of women in bushmeat hunting—Insights from Tanzania and Ethiopia. Journal of Rural Studies, 28(4), 622–630. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J., Pierrehumbert R. (2019). Climate impacts of cultured meat and beef cattle. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, Article 5. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machín L., Cabrera M., Curutchet M. R., Martínez J., Giménez A., Ares G. (2017). Consumer perception of the healthfulness of ultra-processed products featuring different front-of-pack nutrition labeling schemes. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49(4), 330–338. 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis C. C., Hodson G. (2017). It ain’t easy eating greens: Evidence of bias toward vegetarians and vegans from both source and target. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(6), 721–744. 10.1177/1368430215618253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi Z., Gill M., Wijk M., van Herrero M., Ramankutty N. (2020). Livestock policy for sustainable development. Nature Food, 1(3), Article 3. 10.1038/s43016-020-0042-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens A., Oberhoff L. (2023). Meat-eating justification when gender identity is threatened: The association between meat and male masculinity. Food Quality and Preference, 104, 104731. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens A., von Krause M., Meyerhöfer S., Aziz C., Baumann F., Denk A., Heitz T., Maute J. (2020). Valuing humans over animals: Gender differences in meat-eating behavior and the role of the Dark Triad. Appetite, 146, 104516. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesler R. M., Leary R. B., Montford W. J. (2022). The impact of masculinity stress on preferences and willingness-to-pay for red meat. Appetite, 171, 105729. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F., Hartmann C., Siegrist M. (2021). Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Quality and Preference, 87, 104063. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minson J. A., Monin B. (2012). Do-gooder derogation: Disparaging morally motivated minorities to defuse anticipated reproach. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 200–207. 10.1177/1948550611415695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modlinska K., Adamczyk D., Maison D., Pisula W. (2020). Gender differences in attitudes to vegans/vegetarians and their food preferences, and their implications for promoting sustainable dietary patterns–A systematic review. Sustainability, 12(16), Article 16. 10.3390/su12166292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mycek M. K. (2018). Meatless meals and masculinity: How veg* men explain their plant-based diets. Food and Foodways, 26(3), 223–245. 10.1080/07409710.2017.1420355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S., Hart C. (2019). Where’s the beef? How masculinity exacerbates gender disparities in health behaviors. Socius, 5, 2378023119831801. 10.1177/2378023119831801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nath J. (2011). Gendered fare?: A qualitative investigation of alternative food and masculinities. Journal of Sociology, 47(3), 261–278. 10.1177/1440783310386828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NCDs. (2015). IARC monographs evaluate red and processed meats. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization. http://www.emro.who.int/noncommunicable-diseases/highlights/red-and-processed-meats-cause-cancer.html [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty Jensen K., Holm L. (1999). Preferences, quantities and concerns: Socio-cultural perspectives on the gendered consumption of foods. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53(5), Article 5. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver C. (2023). Mock meat, masculinity, and redemption narratives: Vegan men’s negotiations and performances of gender and eating. Social Movement Studies, 22(1), 62–79. 10.1080/14742837.2021.1989293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onwezen M. C., Bouwman E. P., Reinders M. J., Dagevos H. (2021). A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite, 159, 105058. 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry J. (2010). Gender and slaughter in popular gastronomy. Feminism & Psychology, 20(3), 381–396. 10.1177/0959353510368129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters A., Ouvrein G., Dhoest A., Backer C. (2022). It’s not just meat, mate! The importance of gender differences in meat consumption. Food, Culture & Society, 26, 1193–1214. 10.1080/15528014.2022.2125723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiler T. M., Egloff B. (2018). Personality and meat consumption: The importance of differentiating between type of meat. Appetite, 130, 11–19. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza J., Ruby M. B., Loughnan S., Luong M., Kulik J., Watkins H. M., Seigerman M. (2015). Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite, 91, 114–128. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P., Hobden K. (1992). Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite, 19(2), 105–120. 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluhar E. B. (2010). Meat and morality: Alternatives to factory farming. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 23(5), 455–468. 10.1007/s10806-009-9226-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann A. (2014). Threatened at the table: Meat consumption, maleness and men’s gender identities. University of Hawaii at Manoa. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/100470 [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmann A. (2022). The taste of compassion: Influencing meat attitudes with interhuman and interspecies moral appeals. Appetite, 168, 105654. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post M. J. (2012). Cultured meat from stem cells: Challenges and prospects. Meat Science, 92(3), 297–301. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prättälä R., Paalanen L., Grinberga D., Helasoja V., Kasmel A., Petkeviciene J. (2007). Gender differences in the consumption of meat, fruit and vegetables are similar in Finland and the Baltic countries. European Journal of Public Health, 17(5), 520–525. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio A. M., Adorni R., Zani A., Trestianu L. (2009). Sex differences in the brain response to affective scenes with or without humans. Neuropsychologia, 47(12), 2374–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy D. E., Brookmeyer K. A., Gentile B., Berke D. S., Zeichner A. (2016). Gender role discrepancy stress, high-risk sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted disease. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(2), 459–465. 10.1007/s10508-014-0413-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson N. J., Shepherd R., Elliman N. A. (1993). Current attitudes and future influence on meat consumption in the U.K. Appetite, 21(1), 41–51. 10.1006/appe.1993.1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H., Rosado P., Roser M. (2017). Meat and dairy production. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/meat-production

- Ritzel C., Mann S. (2021). The old man and the meat: On gender differences in meat consumption across stages of human life. Foods, 10(11), Article 11. 10.3390/foods10112809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. (2008). Beasts, burgers, and hummers: Meat and the crisis of masculinity in contemporary television advertisements. Environmental Communication-a Journal of Nature and Culture, 2, 281–301. 10.1080/17524030802390250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E., Lahelma E., Virtanen M., Prättälä R., Pietinen P. (1998). Gender, socioeconomic status and family status as determinants of food behaviour. Social Science & Medicine, 46(12), 461519–461529. 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00032-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld D. L. (2019). A comparison of dietarian identity profiles between vegetarians and vegans. Food Quality and Preference, 72, 40–44. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld D. L. (2020). Gender differences in vegetarian identity: How men and women construe meatless dieting. Food Quality and Preference, 81, 103859. [Google Scholar]

- Rothgerber H. (2013). Real men don’t eat (vegetable) quiche: Masculinity and the justification of meat consumption. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(4), 363–375. 10.1037/a0030379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby M. B., Heine S. J. (2011). Meat, morals, and masculinity. Appetite, 56(2), 447–450. 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler M. J. (2004). Meat alternatives—Market developments and health benefits. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 15(5), 250–260. 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salmen A., Dhont K. (2023). Animalizing women and feminizing (vegan) men: The psychological intersections of sexism, speciesism, meat, and masculinity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(2), Article e12717. 10.1111/spc3.12717 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santo R. E., Kim B. F., Goldman S. E., Dutkiewicz J., Biehl E. M. B., Bloem M. W., Neff R. A., Nachman K. E. (2020). Considering plant-based meat substitutes and cell-based meats: A public health and food systems perspective. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, Article 134. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00134 [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M. T., Branscombe N. R. (2001). The good, the bad, and the manly: Threats to one’s prototypicality and evaluations of fellow in-group members. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(6), 510–517. 10.1006/jesp.2001.1476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schösler H., de Boer J., Boersema J. J., Aiking H. (2015). Meat and masculinity among young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch adults in the Netherlands. Appetite, 89, 152–159. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton A. E., Garnett T., Lorimer J. (2019). Framing the future of food: The contested promises of alternative proteins. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(1), 47–72. 10.1177/2514848619827009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist M., Hartmann C. (2019). Impact of sustainability perception on consumption of organic meat and meat substitutes. Appetite, 132, 196–202. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton A. (2008). “It’s because of the invincibility thing”: Young men, masculinity, and testicular cancer. International Journal of Men’s Health, 7(1), 40–58. 10.3149/jmh.0701.40 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan C., Gough B., Conner M. (2010). Healthy masculinities? How ostensibly healthy men talk about lifestyle, health and gender. Psychology & Health, 25(7), 783–803. 10.1080/08870440902883204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J. (2005). Men, meat, and marriage: Models of masculinity. Food and Foodways, 13(1–2), 135–158. 10.1080/07409710590915409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sogari G., Bogueva D., Marinova D. (2019). Australian consumers’ response to insects as food. Agriculture, 9(5), Article 5. 10.3390/agriculture9050108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spence J. T., Helmreich R., Stapp J. (1974). Personal Attributes Questionnaire. 10.1037/t02466-000 [DOI]

- Stanley S. K., Day C., Brown P. M. (2023). Masculinity matters for meat consumption: An examination of self-rated gender typicality, meat consumption, and veg*nism in Australian men and women. Sex Roles, 88(3), 187–198. 10.1007/s11199-023-01346-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumpter K. C. (2015). Masculinity and meat consumption: An analysis through the theoretical lens of hegemonic masculinity and alternative masculinity theories. Sociology Compass, 9(2), 104–114. 10.1111/soc4.12241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talle A. (1990). Ways of milk and meat among the Maasai: Gender identity and food resources in a pastoral economy. In Pálsson G. (Ed.), From water to world-making (pp. 73–92). SIAS. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. A. (2016). Are vegans the same as vegetarians? The effect of diet on perceptions of masculinity. Appetite, 97, 79–86. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E., Pleck J. (1970). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29, 531–543. 10.1177/000276486029005003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timeo S., Suitner C. (2017). Eating meat makes you sexy: Conformity to dietary gender norms and attractiveness. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19, 418–429. 10.1037/men0000119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler C., Visschers V. H. M., Siegrist M. (2011). Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite, 57(3), 674–682. 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh D. W. K., Srv A., Henry C. J. (2022). Unknown impacts of plant-based meat alternatives on long-term health. Nature Food, 3(2), Article 2. 10.1038/s43016-022-00463-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]