Abstract

Background

Air pollution is associated with lower lung function, and both are associated with premature mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Evidence remains scarce on the potential mediating effect of impaired lung function on the association between air pollution and mortality or CVD.

Methods

We used data from UK Biobank (n∼200 000 individuals) with 8-year follow-up to mortality and incident CVD. Exposures to particulate matter <10 µm (PM10), particulate matter <2.5 µm (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) were assessed by land-use regression modelling. Lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and the FEV1/FVC ratio) was measured between 2006 and 2010 and transformed to Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) z-scores. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards and causal proportional hazards mediation analysis models were fitted, stratified by smoking status.

Results

Lower FEV1 and FVC were associated with all-cause and CVD mortality, and incident CVD, with larger estimates in ever- than never-smokers (all-cause mortality hazard ratio per FEV1 GLI z-score decrease 1.29 (95% CI 1.24–1.34) for ever-smokers and 1.16 (95% CI 1.12–1.21) for never-smokers). Long-term exposure to PM2.5 or NO2 was associated with incident CVD, with similar effect sizes for ever- and never-smokers. Mediated proportions of the air pollution–all-cause mortality estimates driven by FEV1 were 18% (95% CI 2–33%) for PM2.5 and 27% (95% CI 3–51%) for NO2. Corresponding mediated proportions for incident CVD were 9% (95% CI 4–13%) for PM2.5 and 16% (95% CI 6–25%) for NO2.

Conclusions

Lung function may mediate a modest proportion of associations between air pollution and mortality and CVD outcomes. Results likely reflect the extent of either shared mechanisms or direct effects relating to lower lung function caused by air pollution.

Shareable abstract

Adverse effects of air pollution on lower lung function (FEV1) potentially mediate 10–30% of the effects of PM2.5 or NO2 on mortality and incident cardiovascular disease https://bit.ly/4bJmWgf

Introduction

According to the Global Exposure Mortality Model, particulate matter <2.5 µm (PM2.5) was estimated to cause nearly 9 million deaths worldwide in 2015, the majority of which were from cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. Ambient air pollution is also an established risk factor for impaired respiratory health. Long-term exposure to particulate matter <10 µm (PM10), PM2.5 or nitrogen dioxide (NO2) has been associated with impaired lung function, and prevalence and incidence of COPD [2–4]. Air pollution has also been associated with increased risk of multimorbidity [5].

Impaired lung function (as measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC)) is predictive of all-cause and cardiovascular (CVD) mortality in general population cohorts in the UK [6, 7]; such associations are also seen among lifelong non-smokers, as reported in UK Biobank previously [7]. Mendelian randomisation studies have suggested that confounding by smoking alone does not explain the relationship between lung function and mortality [8, 9]. Few studies, however, have reported the potential mediating role of impaired lung function on the associations between air pollution and mortality or CVD outcomes [10], in particular in subgroups that differ by smoking status. Previous studies have shown that the effect of air pollution on lung function may differ by smoking status [2]; effects of air pollution in ever-smokers have been hypothesised as being harder to detect, since smoking may already impair lung function via similar pathways to air pollution. Moreover, when studying the relationship between lung function and CVD, associations in smokers are likely to be residually confounded by smoking intensity [7].

We previously reported in a cross-sectional analysis that ambient air pollution was associated with lower levels of lung function in UK Biobank [2]. In this present study, we further investigate the extent to which associations between air pollution and mortality or incident CVD are potentially driven by the effect of air pollution on the spirometric measures of FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC. Three theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between lung function and CVD, including shared risk factors (e.g. confounding of the association), lung function representing the end-point of multiple early-life risk factors that affect CVD, and that reduced lung function (in our study, proposed as a result of air pollution exposure) might cause endothelial dysfunction and promote atherosclerosis [11]. Whilst gaseous pollutants may reach the alveoli and diffuse across the blood–air barrier, particulate matter may lodge in proximal airways of decreasing calibre, according to particle size [12]. Therefore, it is hypothesised that some inhaled pollutants may directly translocate to the bloodstream and exert local effects on the vasculature, whereas others may provoke a pulmonary inflammatory response with systemic consequences [13, 14]. In the largest mediation analysis of its kind, we estimated the proportions of the air pollution–outcome associations explained by the relationship between air pollution and lung function impairment.

Methods

Study populations

UK Biobank is a prospective cohort study of more than 500 000 participants (aged 40–69 years at baseline, 2006–2010), recruited from general practices across the UK [15]. On joining the study, participants attended a clinical interview with a nurse, completed questionnaires on their health and lifestyle, and performed spirometry. UK Biobank includes linkage to electronic healthcare records, as well as ambient air pollution concentration estimates at residence (supplementary table S1). All participants provided written consent, and ethical approval at the inception of the overall UK Biobank study was obtained from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethical Committee and Patient Information Advisory Group. These specific analyses have been approved as part of UK Biobank project 648.

Study outcomes

The main study outcomes in this analysis include mortality (all-cause and CVD) and incident CVD. Dates and causes of death from linked death registry data were used to define all-cause and CVD mortality. Death from CVD was defined in participants with a primary cause of death specifying an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code from the list described in supplementary table S2 and supplementary methods. Incident CVD (fatal and non-fatal events) was defined using the aforementioned death registry data and from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data. ICD-10 codes that defined fatal and non-fatal incident CVD events are also described in supplementary table S2. Participants with prevalent CVD events at the time of entering the study were excluded. The origin for the time axis was set to year of birth, with subjects entering analysis on the date of the baseline study visit. Censor dates were as described previously [16]: censor dates for mortality were 31 January 2016 in England and Wales, and 30 November 2015 in Scotland (and for participants whose location was unclear). For incident CVD (based on death registry data and HES data), censor dates were 31 March 2015 (England), 31 October 2015 (Scotland) and 29 February 2016 (Wales). Participants with hospital admissions from multiple nations were excluded (n=2772), as a censor date could not be confidently ascribed.

Air pollution estimates

Land-use regression (LUR)-based estimates of PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 for year 2010 [17, 18] were linked to the geocoded residential address of each participant in UK Biobank. The LUR models used AirBase routine monitoring data with geospatial variables on road network, land use, population density and altitude. Models were originally developed for the Greater London area, with cross-validation in the study area of R2=77%, 88% and 87% for PM10, PM2.5 and NO2, respectively. Evaluation of transferability of the LUR models across the UK was assessed by comparing the modelled estimates with those from the UK's Automatic Urban and Rural Network monitoring data [19]. The R2 values fell with distance from study area, but whereas R2 values remained >0.5 for NO2, they were lower for particulate matter in northern England and Scotland, therefore particulate matter data >400 km from Greater London was not assigned to these areas (and they were excluded from analysis).

Lung function measurements

Best measures of FEV1, FVC and their ratio (FEV1/FVC) underwent quality control as described previously [20]; briefly, the “best measure” per individual was defined as the highest measure from the “acceptable” blows for FEV1 and FVC. FEV1/FVC was derived from the selected FEV1 and FVC. Pre-bronchodilation lung function tests were performed using the Pneumotrac 6800 spirometer (Vitalograph, Maids Moreton, UK) by trained staff. Further outlier exclusions were undertaken by calculating per-trait z-scores, using the Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) 2012 lung function equations, with any participant with an absolute GLI z-score value >5sd from the mean for any trait being excluded [21]. As explained previously, an individual's GLI “z-score” indicates their relative position (in terms of an sd (z) score) on a distribution for a given lung function trait in a population of non-smokers of a comparative age, sex and height [7]. Lung function GLI z-scores were used in the analysis, with hazard ratios (HRs) given for a 1-unit decrease in lung function GLI z-score (where a decrease in score indicates worse lung function).

Statistical analysis

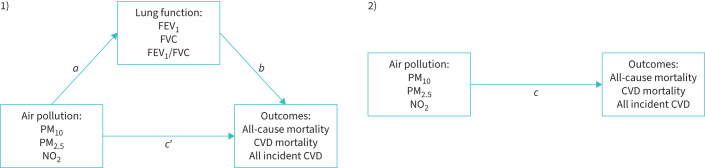

We first performed survival analyses (figure 1) investigating: 1) lung function in relation to all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and incident CVD, and 2) the relationship between air pollution and the same outcomes. Smoking-stratified analyses and analyses in smokers adjusting for smoking intensity were conducted to obtain more accurate estimates in ever-smokers. Effect modification by anthropometric and sociodemographic factors (including occupation) and asthma was explored. Finally, we conducted mediation analyses to examine proportions of the air pollution–outcome associations that could potentially be explained by the relationship between air pollution and FEV1.

FIGURE 1.

Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) detailing the analyses in this paper. The aim of the paper is to understand the extent to which the relationship between air pollution and outcomes studied (all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and all incident CVD) may be mediated by lung function impairment (see DAG 1). a indicates the relationship between air pollution and lung function, which has already been studied in detail in Doiron et al. [2]. b indicates the relationship between lung function and the outcomes (see table 3; all-cause and CVD mortality have been previously studied in Gupta and Strachan [7], this analysis additionally studies fatal and non-fatal CVD events and extends analyses to smokers). The sum of a+b indicates the indirect effect of air pollution on the outcomes that passes via lung function. c′ indicates the direct effect of air pollution on the outcomes. The total effect of air pollution on the outcomes c is estimated in table 3. The mediated proportion is the indirect effect a+b divided by the total effect c and is given in table 4. PM10: particulate matter <10 µm; PM2.5: particulate matter <2.5 µm; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity.

Rates of all-cause and CVD mortality, and incident CVD, were expressed per 10 000 person-years, stratified by age group and calendar year. Rates were calculated for 2008–2015, because although data for 2006–2016 exist, there were only small numbers of events in 2016 (since the last date of linkage in England, where the majority of participants live, was in 2015) and relatively few participants were recruited in 2006–2007.

Survival analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazards models. The origin for the time axis was set to year of birth, with subjects entering analysis on the date of the baseline study visit. Proportional hazard assumptions were tested between each lung function GLI z-score and air pollution variable with study outcomes, by plotting –ln(−ln(survival)) versus ln(analysis time) curves, per quintile of exposure. Correlations between Schoenfeld residuals and log(time) were then assessed.

Survival analyses were stratified by “ever” versus “never” smoking status and adjusted for covariates (see below). 1) FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC were explored as predictors of mortality (all-cause and CVD) and incident CVD. Hazard ratios were expressed per 1-unit decrease in GLI z-score. 2) PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 were investigated as predictors of the same outcomes. Hazard ratios were expressed per interquartile range (IQR) increase in each pollutant.

The proportion of the associations between air pollution and the outcomes that might be driven by FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC was investigated in mediation analyses, first in all participants and then stratified by smoking status. Analyses were only conducted for pollutants with evidence of an association with the outcomes. The estimated mediated proportion was computed at the median of the lung function trait and the exposure effect was compared across the IQR. Cox regression was used to model the outcome and linear regression was used to model the mediator.

Survival and mediation analyses were adjusted for the following potential confounders: sex, height (cm), body mass index (kg·m−2), average household income before tax (dichotomised into <GBP 31 000 and ≥GBP 31 000), education level (categorised into “None”, “O Level, CSE or GCSE”, “A2, AS, NVQ, HNDC or Other” and “Degree”) and passive smoking (exposure to household smoke ≥1 h·week−1). In ever-smokers, results were further adjusted for smoking intensity, using “pack-years” (1 pack-year=20 cigarettes smoked per day per year).

Where a lung function or air pollution measure showed evidence of association with study outcomes, evidence of effect modification was assessed, using interaction terms, and then subgroup analysis, for: male versus female sex, age ≥65 versus <65 years, obesity (≥30 kg·m−2) versus non-obesity (<30 kg·m−2), “ever” versus “never” smoking status, income (≥GBP 31 000 versus <GBP 31 000), asthma versus no asthma and in those having a high-risk occupation for COPD [2, 22] versus those who did not (see supplementary table S3 for occupations considered). Covariates were as above.

Analysis was by complete-case analysis. Since many ever-smoker participants had missing data for “pack-years”, two sensitivity analyses were conducted, each omitting pack-years from the survival analyses for lung function and air pollution. First, the pack-years variable was omitted in ever-smokers with pack-years data. This analysis assessed sensitivity of the results to adjusting for smoking intensity. Next, pack-years was omitted again, but the sample of ever-smokers was expanded, this time also including ever-smokers without pack-years data. The latter analysis explored whether there was a selection effect when restricting to smokers with pack-years data, regardless of pack-years adjustment.

Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to undertake analyses, with the med4way package used to estimate mediated proportions in a survival model framework [23].

Results

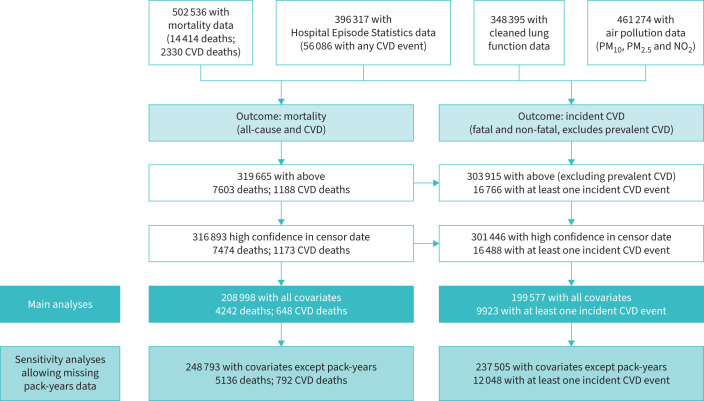

A total of 208 998 individuals with complete covariate data (4242 deaths, of which 648 were CVD deaths) formed the “mortality analysis sample”. The “incident CVD analysis sample” (n=199 577, with 9923 incident CVD events) was a subset of these individuals which excluded those with prevalent CVD (see study flowchart in figure 2). Comparing the 316 893 individuals with incomplete covariate data to those in the mortality and incident CVD analysis samples, the latter two groups were more highly educated, had higher household incomes and were less likely to have ever smoked (table 1). Incidence rates of all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and incident CVD were fairly static over 2008–2015, with a slight increase over time in the oldest groups (supplementary figures S1–S3).

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart detailing construction of the analysis sample in UK Biobank. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for individuals with complete data on key exposures and outcomes versus those in two main analysis samples for mortality and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD)

| Factor | Level | Complete outcome data # | Mortality analysis sample | Level |

CVD analysis (mortality

and incidence) sample |

| Individuals | 316 893 | 208 998 | 199 577 | ||

| Outcome | Alive | 309 419 (97.6) | 204 756 (98.0) | No CVD | 189 654 (95.0) |

| Died (other cause) | 6301 (2.0) | 3594 (1.7) | Incident CVD | 9923 (5.0) | |

| Died (CVD) | 1173 (0.4) | 648 (0.3) | |||

| FEV1 (L) | 2.8±0.8 (n=316 893) |

2.9±0.8 (n=208 998) |

2.9±0.8 (n=199 577) |

||

| FVC (L) | 3.7±1.0 (n=316 893) |

3.7±1.0 (n=208 998) |

3.7±1.0 (n=199 577) |

||

| FEV1/FVC | 0.8±0.1 (n=316 893) |

0.8±0.1 (n=208 998) |

0.8±0.1 (n=199 577) |

||

| COPD (GOLD stage) | No COPD | 272 468 (86.0) | 182 930 (87.5) | No COPD | 175 326 (87.8) |

| Stage 1 | 20 610 (6.5) | 12 850 (6.1) | Stage 1 | 12 247 (6.1) | |

| Stage 2 | 20 994 (6.6) | 11 818 (5.7) | Stage 2 | 10 793 (5.4) | |

| Stage 3 | 2608 (0.8) | 1287 (0.6) | Stage 3 | 1119 (0.6) | |

| Stage 4 | 213 (0.1) | 113 (0.1) | Stage 4 | 92 (<1) | |

| PM10, 2010 (μg·m−3) | 16.0 (15.2–17.0) (n=316 893) |

16.0 (15.2–17.0) (n=208 998) |

16.0 (15.2–16.9) (n=199 577) |

||

| PM2.5, 2010 (μg·m−3) | 9.9 (9.3–10.5) (n=316 893) |

9.9 (9.2–10.5) (n=208 998) |

9.9 (9.2–10.5) (n=199 577) |

||

| NO2, 2010 (μg·m−3) | 25.9 (21.1–30.9) (n=316 893) |

25.6 (21.0–30.7) (n=208 998) |

25.6 (21.0–30.7) (n=199 577) |

||

| Sex | Female | 176 405 (55.7) | 116 341 (55.7) | Female | 113 452 (56.8) |

| Male | 140 488 (44.3) | 92 657 (44.3) | Male | 86 125 (43.2) | |

| Age (years)¶ | 56.3±8.1 (n=316 893) |

55.9±8.0 (n=208 998) |

55.6±8.0 (n=199 577) |

||

| Age group¶ | <45 years | 33 520 (10.6) | 23 177 (11.1) | <45 years | 23 018 (11.5) |

| ≥45 and <55 years | 92 690 (29.2) | 64 090 (30.7) | ≥45 and <55 years | 62 926 (31.5) | |

| ≥55 and <65 years | 133 931 (42.3) | 87 247 (41.7) | ≥55 and <65 years | 82 801 (41.5) | |

| ≥65 years | 56 752 (17.9) | 34 484 (16.5) | ≥65 years | 30 832 (15.4) | |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 27.3±4.7 (n=316 623) |

27.3±4.7 (n=208 998) |

27.2±4.7 (n=199 577) |

||

| BMI category+ | Normal | 106 648 (33.7) | 70 757 (33.9) | Normal | 68 989 (34.6) |

| Overweight | 134 951 (42.6) | 88 967 (42.6) | Overweight | 84 822 (42.5) | |

| Obese | 75 294 (23.8) | 49 274 (23.6) | Obese | 45 766 (22.9) | |

| Height (cm) | 168.4±9.2 (n=316 893) |

168.6±9.1 (n=208 998) |

168.5±9.1 (n=199 577) |

||

| Education§ | None | 48 954 (15.4) | 26 351 (12.6) | None | 23 867 (12.0) |

| O Level/CSE/GCSE | 54 517 (17.2) | 35 019 (16.8) | O Level/CSE/GCSE | 33 634 (16.9) | |

| A2/AS/NVQ/HNDC/Other | 106 745 (33.7) | 71 546 (34.2) | A2/AS/NVQ/HNDC/Other | 68 345 (34.2) | |

| Degree | 103 894 (32.8) | 76 082 (36.4) | Degree | 73 731 (36.9) | |

| Missing | 2783 (0.9) | ||||

| Income | <GBP 31 000 | 125 953 (39.7) | 92 645 (44.3) | <GBP 31 000 | 86 623 (43.4) |

| ≥GBP 31 000 | 148 228 (46.8) | 116 353 (55.7) | ≥GBP 31 000 | 112 954 (56.6) | |

| Missing | 42 712 (13.5) | ||||

| Smoking status | Never-smoker | 173 669 (54.8) | 145 776 (69.7) | Never-smoker | 141 055 (70.7) |

| Ever-smoker | 143 224 (45.2) | 63 222 (30.3) | Ever-smoker | 58 522 (29.3) | |

| Passive smoke exposure | None | 272 715 (86.1) | 198 511 (95.0) | None | 189 756 (95.1) |

| Any | 15 032 (4.7) | 10 487 (5.0) | Any | 9821 (4.9) | |

| Missing | 29 146 (9.2) | ||||

| Asthma | Never had asthma | 280 868 (88.6) | 184 892 (88.5) | Never had asthma | 176 542 (88.5) |

| Ever had asthma | 35 564 (11.2) | 23 953 (11.5) | Ever had asthma | 22 897 (11.5) | |

| Missing | 461 (0.1) | 153 (0.1) | Missing | 138 (0.1) | |

| Occupation | Non “at-risk” occupation | 311 072 (98.2) | 205 730 (98.4) | Non “at-risk” occupation | 196 463 (98.4) |

| “At-risk” occupation | 5821 (1.8) | 3268 (1.6) | “At-risk” occupation | 3114 (1.6) |

Data are presented as n, n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range). For continuous variables, numbers with non-missing data are given in brackets after the mean or median values (e.g. 2.9±0.8 (n=208 998)); for categorical variables, numbers missing are given as a separate category. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PM10: particulate matter <10 µm; PM2.5: particulate matter <2.5 µm; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; BMI: body mass index. #: numbers of participants with incomplete covariate data; ¶: at recruitment; +: normal <25 kg·m−2, overweight 25–29.9 kg·m−2 and obese ≥30 kg·m−2; §: the four categories correspond (approximately) to less than secondary education, secondary education, further education (usually 16–18 years) and degree level education (usually ≥18 years).

Lung function, mortality and incident CVD

A decrease in FEV1 and FVC GLI z-scores was associated with increased all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and incident CVD (table 2). Point estimates for both mortality outcomes were larger in ever-smokers than never-smokers. For example, all-cause mortality HR per FEV1 GLI z-score decrease in ever-smokers 1.29 (95% CI 1.24–1.34) versus never-smokers 1.16 (95% CI 1.12–1.21); corresponding HR for CVD mortality in ever-smokers 1.43 (95% CI 1.31–1.57) versus never-smokers 1.31 (95% CI 1.18 1.45). Associations between FEV1 or FVC GLI z-scores and incident CVD were almost identical by smoking status. For all outcomes, associations with FEV1/FVC GLI z-score were found in ever-smokers only, and the relative magnitude of each association mirrored the results for FEV1 and FVC.

TABLE 2.

Associations between lung function variables and mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD), n=208 998) and all incident CVD (n=199 577), stratified by smoking status

| Individuals (n) | Outcomes (n) | Hazard ratio# (95% CI) | |||

| FEV1 | FVC | FEV1/FVC | |||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Never-smokers | 145 776 | 2267 | 1.16 (1.12–1.21) | 1.17 (1.13–1.22) | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) |

| Ever-smokers | 63 222 | 1975 | 1.29 (1.24–1.34) | 1.27 (1.22–1.33) | 1.20 (1.14–1.25) |

| CVD mortality | |||||

| Never-smokers | 145 776 | 286 | 1.31 (1.18–1.45) | 1.38 (1.24–1.54) | 1.01 (0.88–1.17) |

| Ever-smokers | 63 222 | 362 | 1.43 (1.31–1.57) | 1.42 (1.29–1.57) | 1.29 (1.16–1.43) |

| All incident CVD | |||||

| Never-smokers | 141 055 | 5743 | 1.12 (1.10–1.15) | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Ever-smokers | 58 522 | 4180 | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity. #: hazard ratios are per Global Lung Function Initiative z-score decrease for each lung function measure. Adjustments were as described in the Statistical analysis section of the Methods.

For all-cause mortality, there was evidence for a greater effect of impaired lung function in ever-smokers (HR for interaction (FEV1×ever-smoker) 1.10; p=0.001) and those from low-income households (HR for interaction (FEV1×higher income) 0.91; p=0.002). For incident CVD, effect sizes were slightly smaller in males (HR for interaction (FEV1×male sex) 0.93; p=1.20×10−4) (supplementary table S4).

Air pollution, mortality and incident CVD

Hazard ratios are reported in terms of an IQR increase in air pollutants. Median (IQR) values for PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 were 9.9 (1.3), 16.0 (1.8) and 25.6 (9.7) μg·m−3, respectively.

For PM2.5 and NO2, there was evidence of association with all-cause mortality, and associations were similar in never-smokers (HR per IQR 1.04 (95% CI 0.99–1.09) for PM2.5 and 1.04 (95% CI 0.98–1.10) for NO2) and ever-smokers (HR per IQR 1.05 (95% CI 0.99–1.10) for PM2.5 and 1.05 (95% CI 0.99–1.11) for NO2) (table 3). Point estimates for associations between PM2.5 or NO2 and CVD mortality were higher in ever-smokers (HR per IQR 1.15 (95% CI 1.02–1.30) for PM2.5 and 1.11 (95% CI 0.97–1.27) for NO2) and close to the null in never-smokers. There was also evidence of association between PM2.5 or NO2 and incident CVD, with similar associations in never-smokers (HR per IQR 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.08) for PM2.5 and 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.08) for NO2) and ever-smokers (HR per IQR 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.09) for PM2.5 and 1.04 (95% CI 1.00–1.09) for NO2). PM10 was not associated with either mortality or incident CVD outcomes.

TABLE 3.

Associations between air pollution variables and mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD), n=208 998) and all incident CVD (n=199 577), stratified by smoking status

| Individuals (n) | Outcomes (n) | Hazard ratio# (95% CI) | |||

| PM10 | PM2.5 | NO2 | |||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| Never-smokers | 145 776 | 2267 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) |

| Ever-smokers | 63 222 | 1975 | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) |

| CVD mortality | |||||

| Never-smokers | 145 776 | 286 | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) |

| Ever-smokers | 63 222 | 362 | 1.02 (0.93–1.13) | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) |

| All incident CVD | |||||

| Never-smokers | 141 055 | 5743 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) |

| Ever-smokers | 58 522 | 4180 | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) |

PM10: particulate matter <10 µm; PM2.5: particulate matter <2.5 µm; NO2: nitrogen dioxide. #: hazard ratios are per interquartile range increase for the air pollution measure (see table 1). Adjustments were as described in the Statistical analysis section of the Methods.

There was no formal evidence of interaction between PM2.5 or NO2 and any of the covariates studied (plus asthma and occupation) in relation to study outcomes (all pinteraction>0.1) (supplementary table S5).

Testing proportional hazard model assumptions

Proportional hazard assumptions were tested for univariate Cox regression models between quintiles of each lung function and air pollution variable with the mortality and CVD incidence outcomes (supplementary figures S4–S6). There was some evidence of departure from the proportional hazards assumption for the CVD mortality analyses for FEV1 (p=0.031) and FEV1/FVC (p=0.001) GLI z-scores (supplementary figure S5).

Sensitivity analyses

In the main analysis, when analysing smokers, we restricted to smokers with pack-years data available (n=63 222), and adjusted the association between lung function and mortality and CVD incidence outcomes for pack-years. However, many ever-smokers (n=39 975) had missing data for pack-years. Therefore, as sensitivity analyses (supplementary table S6), we performed two analyses without pack-years data, in 1) the same 63 222 individuals analysed in the main analysis and 2) in a larger sample of 103 197 smokers, regardless of whether or not they had pack-years data available. Point estimates were consistently larger in both sensitivity analyses where pack-years was not included, suggesting that controlling for smoking intensity was important, and drove the difference in the results in the main and sensitivity analyses (as opposed to a selection effect whereby those with pack-years data available differed greatly from those without it). A similar pattern of results (albeit with less pronounced differences) was seen for the air pollution analyses (supplementary table S7).

Mediation analyses

Mediation analyses were only conducted for the associations between air pollution and all-cause mortality and incident CVD, as there was less consistent evidence of an association between air pollution and CVD mortality, as seen in table 3.

There was evidence that associations of PM2.5 or NO2 with all-cause mortality could be partially mediated via FEV1 (estimated proportion mediated 0.18 (95% CI 0.02–0.33) for PM2.5 and 0.27 (95% CI 0.03–0.51) for NO2) (table 4). Whilst smoking-stratified analyses may have been underpowered, point estimates were similar in magnitude for PM2.5, but larger in never-smokers for NO2 (although confidence intervals overlapped for estimates in ever- and never-smokers). For incident CVD, point estimates were larger for NO2 (0.16 (95% CI 0.06–0.25)), although confidence intervals overlapped with those of PM2.5 (0.09 (95% CI 0.04–0.13)). Differences in effect sizes by smoking status were not pronounced.

TABLE 4.

Estimated proportions of associations between particulate matter <2.5 µm (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2)# and all-cause mortality and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD), mediated by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)

| Coefficient¶ (95% CI) | ||

| PM2.5 | NO2 | |

| All-cause mortality | ||

| All | 0.18 (0.02–0.33) | 0.27 (0.03–0.51) |

| Never-smokers | 0.16 (−0.05–0.38) | 0.28 (−0.12–0.67) |

| Ever-smokers | 0.15 (−0.05–0.35) | 0.19 (−0.04–0.43) |

| All incident CVD | ||

| All | 0.09 (0.04–0.13) | 0.16 (0.06–0.25) |

| Never-smokers | 0.11 (0.03–0.19) | 0.20 (0.04–0.35) |

| Ever-smokers | 0.06 (0.01–0.11) | 0.10 (0.00–0.19) |

#: analyses not run for particulate matter <10 µm, since there was no strong evidence of association between this pollutant and mortality or incident CVD; ¶: coefficients are estimate proportions of the effect of the pollutant on the outcome mediated via FEV1. Results were produced using the med4way Stata package, specifying the lower and upper quartiles of the air pollutants as the referent (a0) and actual (a1) levels of the exposure (a0), the median of FEV1 as the level of the mediator at which the four-way decomposition is computed (m), “cox” as the form of regression model for the outcome (yreg) and “linear” as the form of the regression model for the mediator (mreg). Confounders (c) were fixed at female sex, income <GBP 31 000, no qualifications, no passive smoke exposure, and at the means of height, body mass index and pack-years smoked.

Mediation analyses studying FVC and FEV1/FVC as mediators are presented in supplementary table S8. Generally, larger point estimates were observed for all-cause mortality compared with incident CVD, and the magnitude of the proportion of effect mediated was smaller for FVC and FEV1/FVC compared with FEV1. Confidence intervals for analyses stratified by smoking were broad, but for incident CVD, the possibility of mediation of pollutant–outcome exposures by FVC was stronger in never-smokers, whereas for FEV1/FVC it was stronger in ever-smokers.

Discussion

In previous analyses of UK Biobank, we found that air pollution was associated with impaired lung function [2]. Whilst the relationship between mortality and lung function has been studied previously in lifelong non-smokers in UK Biobank [5], in the current study, we additionally studied smokers. We found that lower levels of FEV1 and FVC were associated with all-cause mortality, CVD mortality and incident CVD regardless of smoking status, whereas associations with FEV1/FVC were mainly apparent in ever-smokers. We also found associations between air pollutants and mortality or incident CVD that were most prominent for NO2 and PM2.5, with no strong associations found for PM10. Mediation analyses suggested that FEV1 could mediate 18% of the association between exposure to PM2.5 and all-cause mortality, and 27% of the association with NO2. Estimated mediated proportions by FEV1 for the associations of the same pollutants with incident CVD were smaller (9% and 16%, respectively).

Our observed associations between PM2.5 and NO2 and all-cause mortality, as well as incident CVD, were comparable to those found in the ELAPSE (Effects of Low-level Air Pollution: a Study in Europe) project [24, 25]. The main biological mechanisms for the effects of PM2.5 or NO2 on morbidity and mortality proposed include promotion of oxidative stress and local pulmonary inflammation, which subsequently leads to subclinical systemic inflammation. Pathways involving increased oxidative stress and inflammation may drive CVD risk, via promoting atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, a prothrombotic state, and alterations to the electrophysiology of the heart and blood pressure regulation [26]. Ultrafine particulates (e.g. particulate matter <0.1 µm (PM0.1)) and noxious gases (e.g. NO2) may also translocate/diffuse into the bloodstream and exert a direct effect on the heart and vasculature [12]. The theory that reduced lung function leads to an increase in systemic inflammation and then to atheroma formation is one of the three theories proposed by McAllister and Newby [11] to explain a relationship between lung function and CVD, with other hypotheses being that the association is confounded or observed because lung function is the end-point of multiple adverse fetal and early-life factors which affect CVD risk.

Our mediation analysis suggested that, in addition to the pathways described above, lung function impairment may partially explain the associations between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and mortality or incident CVD. For FEV1 and FVC, this result was more prominent in never-smokers; for FEV1/FVC, the result was more prominent in ever-smokers. Our results in all participants are in broad agreement with a previous mediation analysis from the SALIA (Study on the influence of Air pollution on Lung function, Inflammation and Ageing) cohort of 2527 elderly women in Germany [10]. Although the outcome assessed in the SALIA study was cardiopulmonary mortality, the confidence intervals of the proportion of the associations of NO2 with mortality and incident CVD mediated by FEV1 in our analysis are consistent with the SALIA estimate (in SALIA, 16.5% of the NO2–cardiopulmonary mortality association was estimated to be mediated via FEV1). Both studies have found that FEV1 mediated less of the association between PM2.5 and the outcomes studied, compared with analyses of NO2.

Oxidative stress and inflammation have also been suggested as key drivers of damage to the lung parenchyma, the physiological repair mechanisms and accelerated lung ageing [27]. The mechanisms of action for NO2 are less well characterised, but may also relate to oxidative stress [26], or concentrations may be a marker of ultrafine particulate matter (both are generated by combustion [28]), which may cause more pulmonary inflammation (which may initiate an acute-phase inflammatory response) and lodge for longer in the lung [29].

Our analyses demonstrated differing magnitudes of associations between lung function and mortality/CVD in ever- and never-smokers. We found that adjusting for smoking intensity (pack-years) in smokers attenuated effect sizes towards those observed in never-smokers. This did not appear to be due to a selection effect of those with non-missing data for smoking intensity. The persistent larger effect size of lung function–mortality estimates in smokers may be due to residual confounding as a result of measurement error in smoking intensity. We also observed higher effect sizes for lung function on all-cause mortality in those with lower household incomes and in males; a residual confounding effect by smoking intensity may explain these findings.

Further, our results for incident CVD suggest that up to 10–20% of the impact of air pollution may be mediated by lung function; therefore, at least 80% occurs through either a different mechanism or direct effects on the cardiovascular system.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest mediation analysis exploring the role of FEV1 in driving associations between air pollution, all-cause mortality and incident CVD, and includes a more diverse population (in terms of age and sex) than studied previously [10]. We were able to stratify by smoking status and control for smoking intensity in analyses of smokers. The large sample size is likely to have helped detection of a potential mediating effect of FEV1 on PM2.5–mortality and –CVD outcome associations; this more modest effect size for PM2.5 may explain why it was not detected in a previous, smaller study [10].

There are a number of limitations in this work. Air pollution model agreement with ground-level monitoring has been shown to be only moderate; if such error is random, this may bias point estimates towards the null. Air pollution estimates were modelled for 2010, potentially up to 4 years after spirometry measures were taken (2006–2010), meaning that the mediator measurement could precede the exposure measurement for some participants. However, there is evidence that air pollution measures are likely to have been relatively stable in the UK over these years [2, 30]. Despite the larger sample size, the follow-up period was shorter than other studies, which along with the strict definition of requiring an ICD-10 code as the primary cause, may have reduced the power of the CVD mortality analyses. Moreover, the analyses of CVD mortality and incident CVD may be vulnerable to bias from competing risks. Importantly, it is recognised that the relationship between lung function and CVD may not be causal [11]. Similarly, in this observational work, we cannot conclude causation from our mediation analyses, and differences in results by lung function traits, outcomes, pollutants and smoking status highlight the need to perform further work to interrogate any potential causal mechanisms. This may require even more complex modelling of additional environmental and non-environmental confounders, such as other cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes and blood pressure) and pollutants (e.g. ultrafine particulate matter), and consideration of mediation–outcome confounders (e.g. if systemic oxidative stress confounds the lung function–CVD relationship, rather than mediates it). Given the correlation between pollutants, which is particularly pronounced for NO2 and PM2.5, future analyses taking into account the dependencies between these variables would be important. Finally, we performed complete-case analysis, which will have limited the power of our analyses and may have led to an underrepresentation of participants from more disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, which may in turn introduce the possibility of collider bias [31].

In conclusion, this study suggests that the effects of PM2.5 or NO2 on lung function may account for between 10% and 30% of the association between these pollutants and all-cause mortality and incident CVD. Future work is required in order to understand whether these associations are causal.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00093-2024.SUPPLEMENT (528KB, pdf)

Supplementary material 00093-2024.SUPPLEMENT (44.4KB, xlsx)

Acknowledgements

This study was performed using UK Biobank (project number 648). The authors would like to acknowledge Mark Rutherford and Lucy Teece (Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK) for their advice on the manuscript.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Author contributions: A.L. Guyatt was involved in all aspects of the work, including design of the analysis (with input from M.D. Tobin, D. Doiron and A.L. Hansell), and analysis and interpretation of the data; A.L. Guyatt wrote the first draft of the paper with input from Y.S. Cai. Y.S. Cai, A.L. Hansell and M.D. Tobin were involved in data interpretation, and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to data interpretation and draft revision.

Conflict of interest: M.D. Tobin has a research collaboration with GSK, and M.D. Tobin and A.L. Guyatt have a research collaboration with Orion Pharma, all unrelated to this paper. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Support statement: A.L. Guyatt was supported by internal awards from the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (204801/Z/16/Z) and British Heart Foundation Accelerator Award (AA/18/3/34220) at the University of Leicester. M.D. Tobin is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (WT202849/Z/16/Z) and holds an National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator Award. Y.S. Cai and A.L. Hansell acknowledge funding from the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Environmental Exposures and Health, a partnership between the UK Health Security Agency, the Health and Safety Executive, and the University of Leicester, and funding from the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS or the NIHR, UK Health Security Agency, Health and Safety Executive or the Department of Health and Social Care. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Ethics statement: This specific project was approved by UK Biobank as part of application 648. No specific ethical approval was required as the project was covered by the overall approvals for UK Biobank as a whole (all participants provided written consent, and ethical approval at the inception of the overall UK Biobank study was obtained from the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethical Committee and Patient Information Advisory Group).

References

- 1.Lelieveld J, Klingmüller K, Pozzer A, et al. Cardiovascular disease burden from ambient air pollution in Europe reassessed using novel hazard ratio functions. Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 1590–1596. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doiron D, de Hoogh K, Probst-Hensch N, et al. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1802140. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02140-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin S, Bai L, Burnett RT, et al. Air pollution as a risk factor for incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. A 15-year population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203: 1138–1148. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1744OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Jørgensen JT, Ljungman P, et al. Long-term exposure to low-level air pollution and incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the ELAPSE project. Environ Int 2021; 146: 106267. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronaldson A, Arias de la Torre J, Ashworth M, et al. Associations between air pollution and multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 1035415. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1035415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duong M, Islam S, Rangarajan S, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular and respiratory morbidity in individuals with impaired FEV1 (PURE): an international, community-based cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e613–e623. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta RP, Strachan DP. Ventilatory function as a predictor of mortality in lifelong non-smokers: evidence from large British cohort studies. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015381. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higbee DH, Granell R, Sanderson E, et al. Lung function and cardiovascular disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2003196. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03196-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Au Yeung SL, Borges MC, Lawlor DA, et al. Impact of lung function on cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular risk factors: a two sample bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Thorax 2022; 77: 164–171. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalecká A, Wigmann C, Kress S, et al. The mediating role of lung function on air pollution-induced cardiopulmonary mortality in elderly women: the SALIA cohort study with 22-year mortality follow-up. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2021; 233: 113705. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAllister DA, Newby DE. Association between impaired lung function and cardiovascular disease. Cause, effect, or force of circumstance? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 3–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0167ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcon-Rodriguez CI, Osornio-Vargas AR, Sada-Ovalle I, et al. Aeroparticles, composition, and lung diseases. Front Immunol 2016; 7: 3. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimakakou E, Johnston HJ, Streftaris G, et al. Exposure to environmental and occupational particulate air pollution as a potential contributor to neurodegeneration and diabetes: a systematic review of epidemiological research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15: 1704. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Künzli N, Tager IB. Air pollution: from lung to heart. Swiss Med Wkly 2005; 135: 697–702. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.11025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strain T, Wijndaele K, Sharp SJ, et al. Impact of follow-up time and analytical approaches to account for reverse causality on the association between physical activity and health outcomes in UK Biobank. Int J Epidemiol 2020; 49: 162–172. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eeftens M, Beelen R, de Hoogh K, et al. Development of land use regression models for PM2.5, PM2.5 absorbance, PM10 and PMcoarse in 20 European study areas; results of the ESCAPE project. Environ Sci Technol 2012; 46: 11195–11205. doi: 10.1021/es301948k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beelen R, Hoek G, Vienneau D, et al. Development of NO2 and NOx land use regression models for estimating air pollution exposure in 36 study areas in Europe – the ESCAPE project. Atmos Environ 2013; 72: 10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.02.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang M, Beelen R, Bellander T, et al. Performance of multi-city land use regression models for nitrogen dioxide and fine particles. Environ Health Perspect 2014; 122: 843–849. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrine N, Guyatt AL, Erzurumluoglu AM, et al. New genetic signals for lung function highlight pathways and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associations across multiple ancestries. Nat Genet 2019; 51: 481–493. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0321-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Matteis S, Jarvis D, Hutchings S, et al. Occupations associated with COPD risk in the large population-based UK Biobank cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2016; 73: 378–384. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Discacciati A, Bellavia A, Lee JJ, et al. Med4way: a Stata command to investigate mediating and interactive mechanisms using the four-way effect decomposition. Int J Epidemiol 2019; 48: 15–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strak M, Weinmayr G, Rodopoulou S, et al. Long term exposure to low level air pollution and mortality in eight European cohorts within the ELAPSE project: pooled analysis. BMJ 2021; 374: n1904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf K, Hoffmann B, Andersen ZJ, et al. Long-term exposure to low-level ambient air pollution and incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of six European cohorts within the ELAPSE project. Lancet Planet Health 2021; 5: e620–e632. doi: 10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00195-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP) . Effects of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution on cardiovascular morbidity: mechanistic evidence. 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5bc8b165ed915d2c01488b9a/COMEAP_CV_Mechanisms_Report.pdf Date last accessed: 10 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckhardt CM, Wu H. Environmental exposures and lung aging: molecular mechanisms and implications for improving respiratory health. Curr Environ Health Rep 2021; 8: 281–293. doi: 10.1007/s40572-021-00328-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seaton A, Dennekamp M. Hypothesis: ill health associated with low concentrations of nitrogen dioxide – an effect of ultrafine particles? Thorax 2003; 58: 1012–1015. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.12.1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schraufnagel DE. The health effects of ultrafine particles. Exp Mol Med 2020; 52: 311–317. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0403-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs . Emissions of air pollutants in the UK – particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5). 2023. www.gov.uk/government/statistics/emissions-of-air-pollutants/emissions-of-air-pollutants-in-the-uk-particulate-matter-pm10-and-pm25 Date last accessed: 10 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffith GJ, Morris TT, Tudball MJ, et al. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 5749. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19478-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00093-2024.SUPPLEMENT (528KB, pdf)

Supplementary material 00093-2024.SUPPLEMENT (44.4KB, xlsx)