ABSTRACT

This integrative review expands on the work of Kramer et al. (2020), by reviewing studies that utilized the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) to examine the interpersonal constructs (thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS) to understand suicidal thoughts and behaviors among service members and Veterans with combat experience. Very few studies (n = 9) in the literature were identified, however important relationships were revealed between combat exposure/experiences, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among military samples. Studies also reported risk factors for high levels of thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness in military samples, such as moral injuries, betrayal, and aggression. This review highlights the utility of the INQ to measure ITS constructs among Post-9/11 U.S. Combat Veterans.

KEYWORDS: Combat veterans, Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, military, Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire, Post-9/11, Global War on Terrorism, deployment, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness

What is the public significance of this article?—This article describes what we know about root causes of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Post-9/11 U.S. Combat Veterans. The authors also describe gaps in knowledge and make recommendations for future research.

Background and significance

High rates of suicide are seen among service members who deployed in support of the Post-9/11 conflicts (i.e., Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn) with 27 suicides per 100,000 Reserve/National Guard service members and 35.1 suicides per 100,000 active-duty service members (Bullman et al., 2021). The literature identifies risk factors for suicidal ideation and attempts among Post-9/11 Combat Veterans (i.e., service members or Veterans who deployed on a combat mission), such as having a traumatic brain injury (Fonda et al., 2017), post-traumatic stress disorder (Blakey et al., 2018), depression, insomnia (Bryan et al., 2015), and experiencing a moral injury during a combat deployment (Nichter et al., 2021). However, studies have not comprehensively explained why Combat Veterans have higher rates of suicide than other service members (Department of Defense, 2021). Thus, a theoretical framework is necessary to deepen our understanding of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans and develop targeted strategies for early identification and preventive interventions. Specifically, the term “suicidal thoughts and behaviors” includes suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts (Franklin et al., 2017).

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS), also known as the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS) was developed to explain why people desire to end their life, as well as how they develop the capability to do so (Joiner, 2005). The three components of the theory are thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and the acquired capability for suicide (Joiner, 2005). Thwarted belongingness refers to feeling socially disconnected from others and perceived burdensomeness refers to feeling burdensome to others, to the point they believe their loved ones would be better off without them. An acquired capability of suicide develops when an individual no longer fears death or has a lower threshold for pain. The capability for suicide can result from near-death experiences or experiencing violence or multiple painful events (Joiner, 2005). This theory is well suited for the military population because the constructs capture important aspects of military culture. Being a part of a “military family” corresponds to feelings of belonging, being a burden is counter to military training, and Combat Veterans frequently experienced traumatic or near-death experiences in battle that may have caused them to acquire the capability for suicide. The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) is a psychometrically sound tool that was developed to measure the interpersonal constructs of the ITS theory (Van Orden, 2009). The INQ has demonstrated strong validity and reliability in military samples (Gutierrez et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2012); however, researchers use several different abbreviated versions of the INQ.

Specific aims

A systematic review of the literature was recently published that focused exclusively on the acquired capability for suicide construct and how it is used in studies involving U.S. military service members and Veterans (Kramer et al., 2020). The authors specifically included Combat Veteran studies and reported correlations between the acquired capability for suicide and combat exposures (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013), specific combat experiences (Butterworth et al., 2017), and the number of deployments a service member has experienced (Bryan & Cukrowicz, 2011). The purpose of this integrative review is to expand on the work of Kramer et al. (2020) by focusing on studies that used the INQ to examine the two other Interpersonal Theory of Suicide constructs (thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) to understand suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Post-9/11 U.S. Combat Veterans. Aims of this review are as follows: a) to determine relationships between combat exposure/experiences, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Post-9/11 Combat Veterans; (b) to identify risk factors for high levels of thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness among Post-9/11 Combat Veterans, (c) to organize studies using different versions of the INQ to compare study findings; and (d) to make recommendations for future research.

Methods

This integrative review was conducted using the Whittemore and Knafl Integrative Review method (2005). This method is a rigorous approach to promote a thorough reporting of the state of the science on a given topic. Compared to other literature review methods, an integrative review allows for the inclusion of diverse primary research within the review (e.g., gray literature). The steps in this process are problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Literature search

A comprehensive search of literature was conducted with the guidance of an experienced medical librarian. Articles were identified through advanced data searches in PubMed, APA PsychInfo, Academic Search Elite, and EMBASE. The precise literature search terms were: Interpersonal Theory of Suicide or Interpersonal psychological theory of suicide or acquired capability for suicide or perceived burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness and suicide* or ptsd, or traumatic brain injury* or concussion and armed forces personnel or combat or military* or soldier or veteran or operation Iraqi freedom or operation enduring freedom. Ancestry searching was also conducted to ensure that scholarly articles were not overlooked.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included if the authors used the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS) as a framework for understanding suicidal thoughts and behaviors among a sample exclusively of Post-9/11 U.S. Combat Veterans. Articles were also included if they used psychometrically sound or reliable versions of the INQ instrument to measure the interpersonal ITS constructs. Articles were excluded from this review if the study was meant to evaluate an INQ instrument, included civilians, or included military participants without combat experience. No articles were excluded by year of publication since the ITS was first published in 2010 (during the Post-9/11 conflicts).

Literature search results

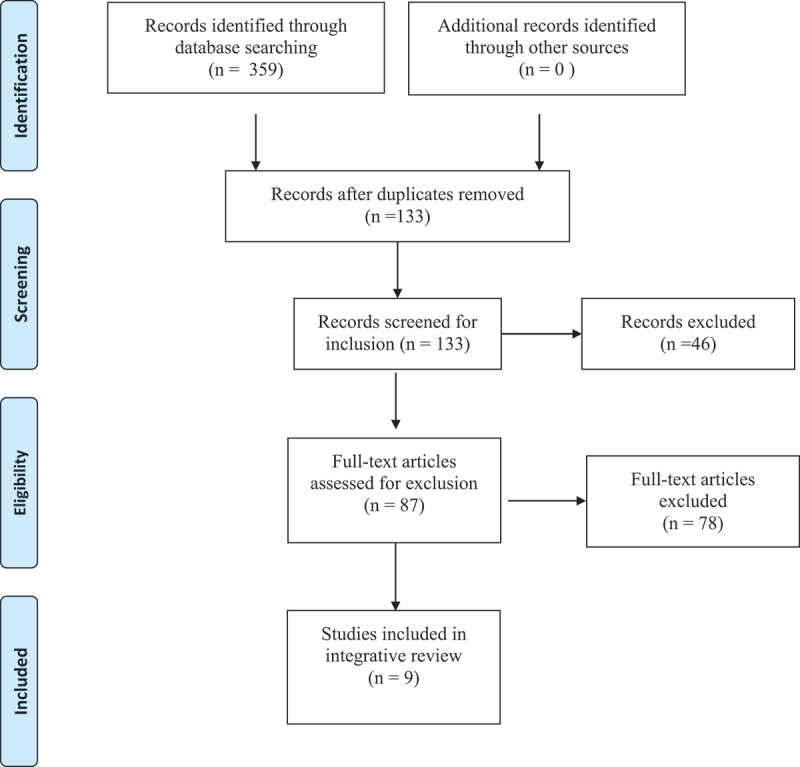

The initial search yielded 359 articles and the ancestry technique yielded no additional data. The articles were first exported to EndNote, sorted by bibliographic database, and then moved to Covidence (a literature review management program) for review. Covidence software identified and removed 226 duplicate articles (63%) and 46 articles (13%) that did not meet inclusion criteria. The remaining 87 articles (24%) were examined for inclusion criteria by two of the authors.

This process resulted in another 78 (22%) articles being excluded from the sample. Most of the articles were excluded for having samples consisting of civilians or service members without combat experience. Others were excluded for not measuring ITS constructs. As a final step, the reviewers graded the articles using the 36-point Hawker Quality Scale (Hawker et al., 2002), which evaluates the title and abstract, introduction and aims, method of data collection, sampling techniques, data analysis, ethics, and bias on a scale of 1(very poor) to 4(good) for each domain. All of the included articles were peer-reviewed research articles, and no articles were excluded after quality scoring, as they all were given a quality score of 31/36 points or higher (see, Table 1). The PRISMA diagram (see, Figure 1) illustrates the literature reduction process (Moher et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Studies exploring associations between thwarted belongingness (TB), perceived burdensomeness (PB), and suicidal ideation (SI) or suicidal behaviors (SB) or suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) among Combat Veterans.

| INQ Version & Authors | Study Purpose | Study Sample | Study Design | Article Quality Score | Major Findings Related to the ITS Constructs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: 8-Item Version (INQ-8) | |||||

| INQ-8 Allan et al. (2019) |

To understand suicidal ideation and suicide behavior trajectories over one year of follow-up. |

n =359 past & current SMs. Army: 66.3% Air Force: 8.1% Marines: 13.9% Navy: 8.1% |

Longitudinal descriptive study with 3-month follow-up assessments over 12 months | 34/36 | TB levels predict SI trajectories. PB levels predict SI trajectories. SI predicted SB. |

| Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: 10-Item Version (INQ-10) | |||||

| INQ-10 Bryan et al. (2010) |

Explore the relationships between combat experience and PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, TB, PB, ACS, SI, and SB. | N = 522 SMs

Army: 24.4.% Air Force: 74% Marines: 1.6% |

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 33/36 | Combat experiences are not related to TB or PB levels. Combat experiences are directly related to ACS. Both TB and PB are directly related to past STBs, PTSD symptoms, and depression symptoms. |

| INQ-10 Bryan and Anestis (2011) |

Examine the relationships between flashbacks and/or repeated nightmares about traumatic experiences (PTSD symptoms), general mental health, TB, PB, ACS, and/or SB. | N = 157 SMs being evaluated for a TBI in theater.

Army: 78.9% Air Force: 13.7% Marines: 5% Active duty: 48.4% ARNG: 34.2% Reserves: 3.7% Unknown: 11.2% |

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 33/36 | PTSD symptoms (flashbacks and/or nightmares) are directly related to TB and PB. |

| INQ-10 Bryan et al. (2012) |

Evaluate the IPTS constructs of TB, PB, ACS, and suicidality in two samples of deployed service members seeking mental health evaluations and/or treatment. |

n1 = 133 SMs with a mild TBI (mTBI). Army: 80.3% n2 = 55 SMs who self-referred to MH clinic. Air Force: 82.7% |

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 34/36 | TB is not significantly associated with STBs, neither independently or in conjunction with either PB or ACS. PB and ACS are associated with STBs. The interaction of PB and ACS is significantly related to STBs. As ACS levels increased, the effect of PB on STBs becomes much more pronounced. |

| INQ-10 Bryan, Hernandez et al. (2013) |

Identify the direct and indirect effects of combat exposure on suicide risk, depression symptom levels, PTSD symptom severity, TB, PB, and ACS. |

n = 348 USAF Security Forces personnel deployed to Iraq (OIF). |

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 34/36 | There is no direct connection between combat exposure and STBs. TB is positively correlated with combat exposure. TB and PB are positively correlated with STBs. Combat exposure is associated with PTSD symptom severity. PTSD symptom severity is strongly associated with depression symptom severity, which in turn is directly related to STBs (in the non-clinical sample) and indirectly related to STBs through high TB and PB (in the clinical sample). |

| Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: 12-Item Version (INQ-12) | |||||

| INQ-12 Martin et al. (2020) |

To examine the relationship between post-battle experiences and TB and PB and SI in a 3 military samples *INQ-12 used for samples 2 & 3 See below for sample 1 (INQ-15). |

n2 = 273 active-duty Air Force Security Forces with history of deployment. n3 = 172 active-duty Army with deployment history, receiving outpatient mental health treatment. |

Cross-sectional survey study | 31/36 |

Sample 2: TB is associated post-battle experiences. PB is not associated with post-battle experiences. Sample 3: TB is not associated with post-battle experiences. PB is not associated with post-battle experiences. |

| Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: 15-Item Version (INQ-15) | |||||

| INQ-15 Martin et al. (2020) |

Examine the relationship between post-battle experiences and TB and PB and SI in 3 military samples. | n = 564 non-clinical mostly ARNG demobilizing from combat deployment. | Cross-sectional survey study | 31/36 |

Sample 1: TB is correlated with post-battle experiences. PB is not associated with post-battle experiences. |

| INQ-15 Butterworth et al. (2017) |

To examine the relationship between specific combat experiences, SI, TB, PB, and/or ACS. | n = 400 mostly ARNG (89.4%) deployed to a combat zone and endorsing combat experience. | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 34/36 | Killing, or thinking one killed an enemy in combat is associated with TB and SI. Witnessing the serious injury or death of a soldier (from one’s unit or an enemy) is associated with TB. Being wounded or injured in combat is associated with TB. |

| INQ-15 Martin et al. (2017) |

To examine the relationship between deployment-related betrayal and TB, and if that relationship is moderated by a specific type of aggression (physical aggression, verbal aggression, hostility, and/or anger) among SMs with at least one previous deployment. | N = 562 mostly ARNG (89.4%)

|

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 35/36 | Betrayal is associated with TB, only when aggression (physical aggression, verbal aggression, hostility, and anger) levels are high. Neither betrayal, nor aggression are associated with PB levels. |

| INQ-15 Houtsma et al. (2017). |

Examine the moderating role of post-deployment social support on the association between moral injury (self-transgressions, other-transgressions, and betrayal) and TB among SMs with at least one previous deployment. | N = 562 mostly ARNG (89.4%)

Note: this sample is the same sample evaluated in the Martin et al. (2017) study. |

Cross-sectional descriptive study | 32/36 | When post-deployment support is low, transgressions toward others and betrayal are significantly associated with TB. Self-transgressions are not associated with post-deployment support or TB. |

SM = Service member; INQ = Interpersonal Questionnaire, AD = active duty; ARNG = Army National Guard; SI = suicidal ideation; SB = suicidal behaviors; SA = suicide attempts; ITS/IPTS = Interpersonal Theory of Suicide/Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide; PB = perceived burdensomeness; TB = thwarted belongingness

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

Data analysis

Table 1 contains information extracted from primary sources using NVIVO-12 software. Categories for extraction included the study purpose, sample size, quality score (Hawker et al., 2002) and major findings related to the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide framework. The articles were then grouped by the version of the INQ used in the study to ensure fair comparisons between measurements and samples. Next, a content analysis was conducted by two of the authors within each grouping to compare key findings. In support of the aims of this review, the information in Table 1 is organized by the version of the INQ used.

Results

Description of studies

The articles’ reported results from quantitative studies exploring thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness among combined samples of nearly 4,000 Combat Veterans. The articles span 10 years (2010 to 2020) of investigative work and were mainly published in psychology journals. Study samples were almost exclusively comprised of United States Army and/or Air Force Combat Veterans. Three of the articles included samples that were predominantly active-duty U.S. Army personnel and three study samples consisted mainly of U.S. Army National Guard service members. One article included an entirely active-duty Army sample and two samples were exclusively Air Force Security Forces. A small percentage of Navy personnel were included in one article (Allan et al., 2019) and Marines were included in three of the nine articles (Allan et al., 2019; Bryan & Anestis, 2011; Bryan et al., 2010). The Army was represented in all but two samples and is therefore overrepresented in this review.

Detailed demographics of each sample, such as relationship status, number of children, education level, and length of military service were not consistently reported, but all authors reported sex, which was predominately male. Articles that described the military rank and race/ethnicity of the sample reported that a majority of the sample were non-Hispanic white enlisted service members (Bryan & Anestis, 2011; Bryan et al., 2012; Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). The majority of the studies relied on self-reported data and used a cross-sectional design. Only one study used a longitudinal design to model suicidal ideation trajectories and make predictions related to suicide (Allan et al., 2019).

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) was developed to assess thwarted belongingness (TB) and perceived burdensomeness (PB) (Van Orden, 2009). Items on the INQ are rated by self-report on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me), and composite scores are computed as mean scores across each subscale. Examples of items assessing TB include, “These days, I feel disconnected from other people” and “These days, I am close to other people” (reverse scored). Examples of PB items include, “These days, the people in my life would be happier without me” and “These days, I think I make things worse for the people in my life” (see Table 2).

Table 2.

A comparison of the different versions of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire.

| INQ-15 Items | INQ-12 | INQ-10 | INQ-8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. These days, the people in my life would be better off if I were gone | |||

| 2. These days, the people in my life would be happier without me | |||

| 3. These days, I think I am a burden on society | Omitted | Changed to “I am a burden on the people in my life” | |

| 4. These days, I think my death would be a relief to the people in my life | Omitted | Omitted | |

| 5. These days, I think the people in my life wish they could be rid of me | Omitted | ||

| 6. These days, I think I make things worse for the people in my life | |||

| 7. These days, other people care about me | Omitted | ||

| 8. These days, I feel like I belong | Omitted | ||

| 9. These days, I rarely interact with people who care about me | Omitted | Omitted | Omitted |

| 10. These days, I am fortunate to have many caring and supportive friends | Omitted | ||

| 11. These days, I feel disconnected from other people | Omitted | ||

| 12. These days, I often feel like an outsider in social gatherings | Omitted | ||

| 13. These days, I feel that there are people I can turn to in times of need | Omitted | Omitted | |

| 14. These days, I am close to other people | |||

| 15. These days, I have at least one satisfying interaction every day | Omitted | Omitted | |

| Additional Item: | Added: “I am an asset to the people in my life” |

After development of the original 25-item INQ (Van Orden, 2009), the same authors conducted exploratory factor analyses on the original version, which resulted in the removal of 10 items (Van Orden et al., 2012). Thereafter, abbreviated versions of the INQ have been used in published research. Four versions of the INQ were used by studies in this review: the INQ-8, INQ-10, INQ-12, and INQ-15. The INQ-10 was the predominant instrument used in earlier military studies (2010–2013) and the INQ-15 was favored by military researchers after it was validated with military samples in 2012 (Van Orden et al., 2012). The main difference between versions is the number of items, and author rationale for version selection is consistently attributed to lowering participant burden (Table 2).

The use of several different versions of the INQ instrument presents a challenge from a measurement standpoint because each version of the INQ essentially becomes a new instrument and inferences from the scores are not perfectly comparable (J.Schreiber, personal communication, 2022). For example, the thwarted belongingness score of an individual on one version of the INQ may be very different than the score on another version of the INQ. Thus, the most accurate comparisons can only be made between studies using the same INQ version (J.Schreiber, personal communication, 2022). Hence, this review is organized by version of the INQ to promote the most accurate comparisons between studies and report findings in context of the version of the INQ used.

INQ – 8

The INQ-8 was developed specifically for Department of Defense-funded research and was psychometrically tested with a high-risk military sample (Allan et al., 2016). The INQ-8 was used in only one study in this review and the reliability was 0.73 for measuring thwarted belongingness and 0.88 for measuring perceived burdensomeness (Allan et al., 2019).

Thwarted belongingness

Allan et al.’s (2019) longitudinal study identified four distinct trajectories of suicidal ideation (SI): Low-Stable, Moderate-Stable, High-Stable, and High-Rapidly Declining (i.e., increasing SI) among a mixed military branch sample of mainly current or former Army service members who endorsed recent suicidal ideation and/or a lifetime suicide attempt (n = 359). Analysis of the data suggested that thwarted belongingness predicted SI trajectories. In general, the subsample endorsing a High-Stable SI trajectory had the highest levels of thwarted belongingness and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and those endorsing Low-Stable SI trajectories also endorsed low levels of thwarted belongingness and PTSD.

Perceived burdensomeness

Allan et al. (2019) also measured perceived burdensomeness, along with PTSD symptoms and substance use over one year. The study showed that perceived burdensomeness also predicted SI trajectories. PB levels were highest in the High-Stable SI trajectory, compared to both Moderate-Stable and Low-Stable SI trajectories. In this sample of high-risk Combat Veterans (i.e., service members endorsing recent suicidal ideation), perceived burdensomeness distinguished between High-Stable and Moderate-Stable trajectories.

INQ-10

The 10-item INQ demonstrated strong factor structure of the two interpersonal variables and clinical utility to identify current suicidal ideation among deployed service members (Bryan, 2011). Four studies used the INQ-10 which demonstrated internal consistencies of greater than 0.80 for measuring thwarted belongingness and greater than 0.70 for measuring perceived burdensomeness.

Thwarted belongingness

Bryan et al. (2010) used the INQ-10 to examine the relationship between thwarted belongingness (TB), past suicidal thoughts and behaviors, PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and combat experiences in a retrospective study using data from a mixed clinical (referred to a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or mental health clinic) and non-clinical sample (service members who participated in baseline testing only) of mostly male (90.4%) Air Force personnel (74%) while deployed to Iraq (n = 522). In the non-clinical sample only, past suicidal thoughts and behaviors, PTSD symptoms, and depression levels were associated with higher levels of TB, regardless of demographic variables such as age, sex, rank, and number of past deployments. Combat experiences were not associated with TB, when clinical variables, like depression, were considered.

TB was positively correlated with PTSD reexperiencing symptoms (Bryan & Anestis, 2011) and PTSD symptom severity (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013) in service members (n = 157 and n = 348, respectively) with a suspected or diagnosed TBI in Iraq (Bryan & Anestis, 2011; Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). Also, suicidal thoughts and behaviors were associated with TB and PTSD (Bryan & Anestis, 2011). In contrast, the Bryan et al. (2012) study found that TB was not associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors in two different samples (combined n = 188) of deployed service members recruited from a TBI and mental health clinic (Bryan et al., 2012). The ambiguous findings may have been due to different combat experiences, number of deployments, and length of time in theater when the data were collected. Bryan, Hernandez et al. (2013) also reported ambiguous findings regarding TB among clinical and non-clinical samples of mainly Air Force Security Forces deployed to Iraq (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). In the Bryan, Hernandez et al. (2013) study, half of the clinical sample had no previous combat deployments and the other half had previously deployed up to 8 times. The non-clinical sample averaged three previous deployments (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). At the time of data collection, service members on their first deployment may not had yet fought in battle, causing their data to mirror service members who had never deployed. This may explain the ambiguity of the study findings. Analysis of data from the non-clinical sample showed that the number of combat experiences were correlated with PTSD symptom severity, but not TB or suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). Analysis also revealed significant relationships between depression symptoms and TB, as well as between depression symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, although there was no direct relationship between TB and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, nor combat exposure and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013).

Perceived burdensomeness

The Bryan et al. (2010) study also measured perceived burdensomeness (PB) and found that high levels of PB were associated with PTSD re-experiencing symptoms, past suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and depression. However, the investigators did not find a direct link between PB and combat experiences (Bryan et al., 2010). This may have been due to evaluating the service members in the combat environment rather than in their home environment where they are more likely to experience PB. PTSD reexperiencing symptoms were also correlated with PB in a sample of mostly Army service members presenting to a TBI clinic in Iraq (Bryan & Anestis, 2011). Bryan et al. (2012) studied an almost identical sample and found that PB was associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. PB and suicidal thoughts and behaviors were also correlated in a mixed clinical sample of Airforce (61.6%) and Army (32%) personnel receiving psychological and/or neuropsychological evaluations in Iraq, but the same association was not found in the non-clinical (baseline testing only) sample from the same study (Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). As mentioned previously, it is unclear if the ambiguous findings are due to differences between service members who had been previously deployed and service members who were on their first deployment. Service members on their first deployment may have not yet had the opportunity to experience feeling like they were a burden because they had not yet returned home to know how it would feel to be around family and friends having experienced combat and/or a combat injury.

INQ-12

The 12-item version of the INQ has been validated with military samples at high risk for suicide with or without combat exposure, and with or without a TBI (Gutierrez et al. (2016). This version removed three items from the INQ-15; two items related to thwarted belongingness (“I feel like I belong,” “These days, I rarely interact with people who care about me”) and one item related to perceived burdensomeness (“I think my death would be a relief to the people in my life”). One study in this review used the INQ-12 and reported reliability statistics of greater than .80 (Martin et al., 2020) for measuring thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Thwarted belongingness

Martin et al. (2020) examined the relationships between post-battle experiences and thwarted belongingness (TB) in three military samples. Post-battle experiences were identified as “consequences of war,” such as seeing dead bodies and destroyed villages (p. 3). The authors used the INQ-12 in two of their three samples (Air Force and Army, n = 445). The researchers identified correlations between post-battle experiences and TB among the Air Force Security Forces sample (n = 273). The correlation between post-battle experiences and TB remained significant after controlling for the participants’ annual income, age, sex, marital status, and perceived burdensomeness levels. However, TB was not associated with post-battle experiences in the group of active-duty Army service members seeking outpatient mental health treatment (n = 172). The authors hypothesized that post-battle experiences may have been less important to this group than the mental health struggles they were experiencing at the time of data collection.

This study did not find an association between perceived burdensomeness and post-battle experiences (witnessing the consequences of war) in either of their samples using the INQ-12.

INQ-15

The INQ-15 is the only abbreviated version of the 25-item INQ that has been psychometrically tested in several different samples (civilian and military) (Van Orden et al., 2012). Psychometric testing found the properties of the INQ-15 to be stronger than the original 25-item questionnaire (Van Orden et al., 2012). Four studies in this review used the INQ-15, and the reliability of the INQ-15 ranged between .85 and .94 for measuring thwarted belongingness and .89 to .94 for measuring perceived burdensomeness in military samples.

Thwarted belongingness

One study examined how combat experiences impacted thwarted belongingness (TB) in Army National Guard service members (n = 400) (Butterworth et al., 2017). This study showed that National Guardsmen who witnessed a fellow service member and/or an enemy soldier being killed or seriously wounded endorsed higher TB levels than their fellow service members who did not witness such events during the same deployment. Likewise, killing someone, or believing they killed someone, was associated with higher TB scores. Martin et al. (2020) also found correlations between negative post-battle experiences and higher TB levels in their sample of Army National Guardsmen (half of whom were returning from a combat tour, n = 564). As noted above, post-battle experience refers to the immediate aftermath of battle, such as destroyed towns and caring for the remains of fellow service members and allies who died. The correlation between negative post-battle experiences and high TB levels remained significant in National Guardsmen, after controlling for annual income, age, sex, marital status, and perceived burdensomeness levels.

Interpersonal experiences during and after deployment also impacted TB levels in a sample predominately of Army National Guardsmen. Houtsma et al. (2017) found that experiencing a transgression (moral injury) or betrayal from a fellow service member during the deployment, combined with a low levels of post-deployment (interpersonal) support, was associated with higher TB levels. Interestingly, the effect of transgressions on TB was specific to the type of transgression. Transgressions committed by the service member did not impact TB levels, but witnessing, failing to prevent, or learning about transgressions committed by others resulted in higher levels of TB. Further analysis showed that post-deployment support moderated the relationship between transgressions (moral injuries) and TB. When post-deployment support was at or above the mean level of support, TB levels were lower.

Martin et al. (2017), using the same Army National Guard sample (n = 562) as Houtsma et al. (2017), tested the impact of aggression on the correlation between betrayal and thwarted belongingness. Betrayal was operationalized or defined as “the perception that an individual has been betrayed by others” (p. 274). The researchers found that the interaction of betrayal and verbal and physical aggression and the interaction of betrayal and hostility were associated with higher TB levels. Associations between betrayal and TB levels were significant only when aggression levels (verbal or physical) were categorized as high.

Perceived burdensomeness

Investigators using the INQ-15 did not find an association between combat or post-battle experiences and perceived burdensomeness (PB) (Butterworth et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2020), but they did find that PB was associated with suicidal ideation and betrayal among a large sample (n = 937) of Army National Guardsmen (Martin et al., 2017). In this sample, aggression did not influence or impact the association between betrayal and PB, although betrayal had a small main effect on PB. PB was a significant covariate when the relationship between betrayal and thwarted belongingness was mediated by hostility and anger. For example, PB was associated with betrayal when hostility levels were high.

Summary of findings

The literature exploring suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Post-9/11 Combat Veterans using the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire suggests relationships between specific experiences in combat, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (ideas of self-harm, past suicide attempts, future suicide plans). The literature also introduces moderators or mediators between the interpersonal constructs of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, such as PTSD betrayal, aggression, and post-deployment support. The following section summarizes the findings of the reviewed studies.

Combat exposure/experience, suicidal ideation, and the interpersonal constructs

Only one of the three studies in this review exploring the impact of combat exposure/experience on suicide found a direct relationship between specific combat experiences (e.g., killing an enemy and/or witnessing the injury or death of a fellow service member) and suicidal ideation (Butterworth et al., 2017). The impact of combat on suicidal thoughts and behaviors was more consistently highlighted when investigators added the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide constructs into their statistical models.

Researchers found relationships between PTSD symptoms (flashbacks and/or nightmares related to combat), thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness in a sample of predominately Army service members (Bryan & Anestis, 2011). Studies looking at more specific experiences in combat found that killing an enemy, witnessing the injury or death of an enemy and/or fellow service member, and being wounded in combat were strongly correlated with thwarted belongingness (not perceived burdensomeness) in Army National Guard service members (Butterworth et al., 2017). These results were confirmed by the Martin et al. (2020) study that revealed an association between thwarted belongingness and combat experiences, such as witnessing death and destruction of villages, in mixed samples of Air Force and Army service members (Martin et al., 2020).

Experiencing a betrayal by a fellow service member while deployed was also associated with thwarted belongingness, and this relationship was moderated by an individual’s propensity toward physical and/or verbal aggression (Martin et al., 2017). Finally, post-deployment support was identified as a possible confounding variable when associations between betrayal, experiencing a transgression while deployed, and thwarted belongingness were explored (Houtsma et al., 2017). Only one study in this review reported that combat experiences were not associated with thwarted belongingness nor perceived burdensomeness in a mixed sample (n = 273) of deployed Air Force and Army service members (Bryan et al., 2010).

The interpersonal constructs and suicidal thoughts and behaviors

The few studies that looked for relationships between the interpersonal ITS constructs and suicidal thoughts and behaviors showed equivocal results. Both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were directly related to past suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Bryan et al., 2010; Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013) in military samples. In fact, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness levels predicted suicidal ideation trajectories among a sample of predominately Army service members (Allan et al., 2019). Yet, several cross-sectional studies examining the relationship between thwarted belongingness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors did not show an association between the same variables (Bryan et al., 2012; Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). However, one study in this review found that perceived burdensomeness levels were associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Bryan et al., 2012).

Risk factors for high thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness levels

Important risk factors for high levels of both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness emerged from the literature, such as depression (Bryan et al., 2010), moral injuries, and the concept of betrayal (Martin et al., 2017). Further, service members’ propensities toward all forms of aggression (verbal and physical) (Martin et al., 2017) and low post-deployment moral support (Houtsma et al., 2017) were correlated with high thwarted belongingness levels. Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also emerged as a notable risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans. PTSD was directly associated with both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, as well as suicidal thoughts andbehaviors and combat experiences. This review shows that PTSD may have indirect pathways to suicidal thoughts and behaviors when examining the ITS constructs. Some Combat Veterans with PTSD appear to have unique risk factors for suicide because of their combat experience.

Gaps in the literature

Several gaps in the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide literature are noted. First, only three studies examined suicidal thoughts and behaviors among service members with a suspected TBI, and the investigators did not look specifically at TBI symptoms, mechanism of injury, and/or number of TBIs (Bryan & Anestis, 2011; Bryan et al., 2012; Bryan, Hernandez et al., 2013). Data from service members with a suspected TBI were only collected in the operational theater; no studies in this review explored how sequelae of a TBI impacted thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, or suicidal thoughts and behaviors once the service members returned from deployment. Consequently, military studies grounded in the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide cannot yet explain why Combat Veterans with a deployment-related TBI are four times more likely to attempt suicide than Combat Veterans without a TBI (Fonda et al., 2017).

Second, there is no consensus from the literature whether number of combat deployments, length of combat deployments, time between deployments, military branch and/or components (active vs. Reserve/National Guard) influenced the effect of thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness on suicidal thoughts and behaviors. For example, it would be interesting to know if there was a difference in thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness levels between Reserve/National Guard and active-duty Combat Veterans based upon the frequency of their exposure to military environments before and after the combat deployment. Third, it is difficult to know if study results would be different if all authors used the same version of the INQ and if more follow-up data was collected after the deployed service members returned home. For example, one study using the INQ-10 found a significant interaction between age, combat exposure levels, and thwarted belongingness levels among Airmen who were not deployed at the time of the study (Bryan, McNaughton-Cassill et al., 2013). As age and combat exposure increased, thwarted belongingness levels increased, especially in Combat Veterans above the age of 34 years (Bryan, McNaughton-Cassill et al., 2013). The Bryan, McNaughton-Cassill et al. (2013) study did not meet our inclusion criteria (only a portion of the sample had combat experience), but the results support the need to continue examining the impact of combat exposure after Combat Veterans are home. Finally, the limited number of studies (n = 9) exclusively looking at Combat Veterans reveals that little is known about theoretically based suicide risk factors in this specific population. Even less is known about female service members and Veterans and Navy and Marine Corps service members and Veterans who deployed to combat zones.

Limitations

Despite our rigorous approach, the inclusion/exclusion criteria and search strategy may have caused articles to be overlooked. In general, this review showed that the military ITSliterature related to the impact of combat is in its infancy, with most investigators using a cross-sectional study design and several studies utilizing the same military sample. Further, the magnitude of the relationship between variables was either small (Butterworth et al., 2017) or not reported.

Though active duty and Reserve/National Guard members were equally represented in this review, the military suicide literature is limited by investigators not fully describing the sample’s combat exposure and experiences, nor the military subgroups which make comparisons of the findings difficult. Studies that examined the impact of combat on suicidal thoughts and behaviors during a deployment did not report how long the sample had been in theater (at the time of the assessment), information related to the combat mission or location, nor did they separate service members with a history of multiple combat experiences in the analyses to compare them to service members on their first combat deployment. Without this information, it is difficult to compare combat experiences across samples, as deployment experiences vary widely based upon the mission and location of service members overseas (J.C. Brooks, personal communication, 2020). For example, some service members were assigned to military posts (e.g., forward operating bases) for the duration of the deployment, while others were assigned to combat outposts embedded in Iraqi or Afghani villages where they endured daily violent encounters (J.C. Brooks, personal communication, 2021). These design limitations inhibit generalizability of the findings and the ability to understand the disparity in suicide rates between Reserve/National Guard and active duty service members who deployed in support of the Post-9/11 conflicts (Bullman et al., 2021).

Lastly, the authors in the reviewed articles often used the term “predictor” when interpreting results from cross-sectional studies which can be misleading and must be interpreted with caution (Hanis & Mansori, 2017). Prediction models can be derived from two separate sets of cohort data, where the prediction model derived from one sample would be validated in a second sample, or longitudinal studies where the prediction model would be validated over time (Hanis & Mansori, 2017). Without longitudinal data, it is difficult to identify potential/true “predictors” of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in military samples. Thus, we changed the wording of the results reported as “predictors” in cross-sectional studies to “associations” to reflect the findings more accurately. Nonetheless, the associations identified in this review are worth noting.

Clinical and research implications

It is clear from this review that the links between military experiences and suicidal thoughts and behaviors are complex. Exposure to combat, witnessing the aftermath of war, thwarted belongingness, betrayal, and post-deployment support play an important role in suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide framework shifts the paradigm from identifying suicide risk factors among Combat Veterans to getting to the heart of how or why suicidal thoughts and behaviors develop in this population.

The findings in this review have important clinical and research implications regarding the interpersonal aspects of suicide among military samples. Previous preventive suicide interventions target specific diagnoses (e.g., TBI, PTSD, depression, anxiety), however, clinicians should consider interventions that place a greater emphasis on addressing thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, betrayal, and/or moral injury. Findings from this review also suggest that study findings are different in clinical and non-clinical military samples. With the knowledge that some conditions (e.g., PTSD, TBI, and depression) are associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Fonda et al., 2017), Combat Veterans with such conditions should receive targeted interventions to address feelings of belonging and of being a burden, in an effort to prevent suicide (Bryan & Anestis, 2011; Bryan, McNaughton-Cassill et al., 2013).

Regarding future research, since we know that sustaining a TBI in combat is a prominent risk factor for suicide attempts (Fonda et al., 2017), and being wounded in combat is associated with thwarted belongingness (Butterworth et al., 2017), future studies should examine how invisible combat injuries (i.e., TBI) impact a Combat Veteran through the lens of the ITS. This is especially important because many of the Combat Veterans included in the reviewed studies have been out of combat environments for some time or are no longer serving in the military. Psychological and physical injuries sustained in combat may place strain on interpersonal relationships (i.e., burden) in their homes and workplaces (civilian and/or military).

Thwarted belongingness is consistently associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans, so studies are necessary to examine specific aspects of the military culture that may impact, or have impacted, Combat Veterans’ sense of “belonging,” such as promotions, job positions, component type, military commendations, or other more subtle institutional norms. Since there are significant differences between military branches and components (e.g., culture, training, and job responsibilities), study samples examining military culture must study each military branch and component separately. To go a step further, it would also be important to identify and examine the sub-cultures within each military branch (e.g., combat arms vs. support personnel). Many of the samples in this review consisted of mixed military branches, thus further research should be conducted to confirm study findings in homogeneous samples.

The concept of betrayal and moral injuries (measured by the Moral Injury Events Scale) emerged as important concepts for the study of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans. It would be interesting to examine the associations between the ITS constructs and moral injuries and betrayal in the post-deployment period. Such investigative efforts may lead to more discoveries because a feeling of betrayal and experiencing a moral injury may also be a risk for suicide in the post-deployment period (Martin et al., 2017).

Finally, researchers must recruit study samples that accurately reflect the racial and ethnic distribution seen in the U.S. military. For example, as of September, 2020, almost 50% of active duty Army and Reserve Soldiers are non-white (Department of the Army, 2020), yet studies in this review enrolled mostly non-Hispanic white service members. Without adequate racial/ethnic representation in studies, the study results are generalizable to only non-Hispanic white service members.

Conclusions

This literature review provides insight into suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Combat Veterans through the use of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. The literature suggests that a sense of belonging and feeling like a burden on others play a key role in suicidal thoughts and behaviors in Combat Veterans. Given the small number of studies of Combat Veterans and high rates of suicide in this population (Bullman et al., 2021), researchers need to focus on Combat Veterans as a unique and specific population. Specifically, longitudinal studies are needed to identify predictors of suicide to inform effective suicide prevention interventions.

The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide provides a useful framework for military suicide research and promotes a common language and shared data to build the body of knowledge on military suicide. Due to the fact that most of the studies in this review used the INQ-15, it would be useful for future military studies using the INQ to use the 15-item version because it has strong psychometric properties and is reliable in Combat Veteran samples (Gutierrez et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2012). This would allow readers to draw accurate comparisons between studies and compare the different military branches and components. In conclusion, we must continue to advocate for the Post-9/11 Combat Veterans through innovative and thoughtful research. New questions must be asked to discover connections that will ultimately lower the suicide rate within this population.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joan Lockhart (Duquesne University) for sharing her expertise and providing feedback on this integrative review. We also thank Dr. David Nolfi (Duquesne University) for his guidance through advanced literature searches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- Allan, N. P., Gros, D. F., Hom, M. A., Joiner, T. E., & Stecker, T. (2016). Suicidal ideation and interpersonal needs: Factor structure of a short version of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire in an at-risk military sample. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 79(3), 249–261. 10.1080/00332747.2016.1185893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan, N. P., Gros, D. F., Lancaster, C. L., Saulnier, K. G., & Stecker, T. (2019). Heterogeneity in short-term suicidal ideation trajectories: Predictors of and projections to suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(3), 826–837. 10.1111/sltb.12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakey, S. M., Wagner, H. R., Naylor, J., Brancu, M., Lane, I., Sallee, M., Kimbrel, N. A., & Elbogen, E. B. (2018). Chronic pain, TBI, and PTSD in military veterans: A link to suicidal ideation and violent impulses? The Journal of Pain, 19(7), 797–806. 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J. (2011). The clinical utility of a brief measure of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness for the detection of suicidal military personnel. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(10), 981–992. 10.1002/jclp.20726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C., & Anestis, M. (2011). Reexperiencing symptoms and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among deployed service members evaluated for traumatic brain injury. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 67(9), 856–865. 10.1002/jclp.20808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Clemans, T. A., & Hernandez, A. M. (2012). Perceived burdensomeness, fearlessness of death, and suicidality among deployed military personnel. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 374–379. 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2011). Associations between types of combat violence and the acquired capability for suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(2), 126–136. https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L362248715&from=export [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Cukrowicz, K. C., West, C. L., & Morrow, C. E. (2010). Combat experience and the acquired capability for suicide. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 66(10), 1044–1056. 10.1002/jclp.20703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Gonzales, J., Rudd, M. D., Bryan, A. O., Clemans, T. A., Ray-Sannerud, B., Wertenberger, E., Leeson, B., Heron, E. A., Morrow, C. E., & Etienne, N. (2015). Depression mediates the relation of insomnia severity with suicide risk in three clinical samples of US Military personnel. Depression and Anxiety, 32(9), 647–655. 10.1002/da.22383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., Hernandez, A. M., Allison, S., & Clemans, T. (2013). Combat exposure and suicide risk in two samples of military personnel. Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 64–77. 10.1002/jclp.21932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C. J., McNaughton-Cassill, M., & Osman, A. (2013). Age and belongingness moderate the effects of combat exposure on suicidal ideation among active duty Air Force personnel [Article]. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 1226–1229. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullman, T., Schneiderman, A. (2021). Risk of suicide among U.S. veterans who deployed as part of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn. Injury Epidemiology, 8(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s40621-021-00332-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, S. E., Green, B. A., & Anestis, M. D. (2017). The association between specific combat experiences and aspects of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 78, 9–18. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense . (2021, September 3). Annual suicide report. https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/CY20%20Suicide%20Report/CY%202020%20Annual%20Suicide%20Report.pdf?ver=0OwlvDd-PJuA-igow5fBFA%3D%3D

- Department of the Army . (2020). Army demographics FY20. https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2021/02/01/aa8adcbb/army-profiles-fy20-tri-fold.pdf

- Fonda, J. R., Fredman, L., Brogly, S. B., McGlinchey, R. E., Milberg, W. P., & Gradus, J. L. (2017). Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among Veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Epidemiology, 186(2), 220–226. 10.1093/aje/kwx044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Huang, X., Musacchio, K. M., Jaroszewski, A. C., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, P. M., Pease, J., Matarazzo, B. B., Monteith, L. L., Hernandez, T., & Osman, A. (2016). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire and the acquired capability for suicide scale in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(12), 1684–1694. 10.1037/pas0000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanis, S. M., & Mansori, K. (2017). Is determination of predictors by cross-sectional study valid? The American Journal of Medicine, 130(10), e455. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker, S., Payne, S., Kerr, C., Hardey, M., & Powell, J. (2002). Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research, 12(9), 1284–1299. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsma, C., Khazem, L. R., Green, B. A., & Anestis, J. C. (2017). Isolating effects of moral injury and low post-deployment support within the U.S. military. Psychiatry Research, 247, 194–199. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, E. B., Gaeddert, L. A., Jackson, C. L., Harnke, B., & Nazem, S. (2020). Use of the acquired capability for suicide scale (ACSS) among United States military and Veteran samples: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 229–242. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. L., Assavedo, B. L., Bryan, A. O., Green, B. A., Capron, D. W., Rudd, M. D., Bryan, C. J., & Anestis, M. D. (2020). The relationship between post-battle experiences and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in three United States military samples. Archives of Suicide Research, 24, 156–172. 10.1080/13811118.2018.1527266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. L., Houtsma, C., Bryan, A. O., Bryan, C. J., Green, B. A., & Anestis, M. D. (2017). The impact of aggression on the relationship between betrayal and belongingness among US military personnel. Military Psychology, 29(4), 271–282. 10.1037/mil0000160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter, B., Norman, S. B., Maguen, S., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2021). Moral injury and suicidal behavior among US combat veterans: results from the 2019-2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans study. Depression and Anxiety, 38(6), 606–614. 10.1002/da.23145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K. A. (2009). Construct validity of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Florida State University, Florida, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K. A., Cukrowicz, K. C., Witte, T. K., & Joiner, T. E. (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychology Assessment, 24(1), 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.