Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and has a 5-year life expectancy of ~8%. Currently, only a few drugs have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for pancreatic cancer treatment. Despite available drug therapy and ongoing clinical investigations, the high prevalence and mortality associated with pancreatic cancer mean that there is an unmet chemopreventive and therapeutic need. From ongoing studies with various novel formulations, it is evident that the development of smart drug delivery systems will improve delivery of drug cargo to the pancreatic target site to ensure and enhance the therapeutic/chemoprevention efficacy of existing drugs and newly designed drugs in the future. With this in view, nanotechnology is emerging as a promising avenue to enhance drug delivery to the pancreas via both passive and active targeting mechanisms. Research in this field has grown extensively over the past decade, as is evident from available scientific literature. This review summarizes the recent advances that have brought nanotechnology-based formulations to the forefront of pancreatic cancer treatment.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, adenocarcinoma, nanoparticle, theranostic, targeted nanocarrier

I. INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States and has a 5-year life expectancy of ~8%.1,2 According to 2017 estimates from the American Cancer Society, ~53,670 new cases (27,970 men and 25,700 women) of PC will be diagnosed and ~43,090 patients (22,300 men and 20,790 women) will die due to this disease.3 From an epidemiological perspective, high risk factors for PC include genetic predisposition, personal or familial history of pancreatitis, age, and, most importantly, lifestyle-related aspects such as smoking (highest risk), tobacco consumption, alcohol, and obesity. Increases in lifestyle-related risk factors, the growing geriatric world population, and late diagnosis are leading to a high prevalence of PC, which in turn is causing propulsive growth in the PC therapeutic market. According to market data forecast, the global PC therapeutics market worth $2.08 billion in 2016 is growing rapidly at a compound annual growth rate of 7.54% and is estimated to reach ~$3 billion by 2021.1,4

Currently, only a few drugs have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for PC treatment. It is also apparent that combination drug therapy is gaining better therapeutic response as compared with single drug therapy (Table 1). Additionally, many clinical investigations are ongoing and a few relevant studies are listed in Table 2.5 Studies indicate that, in addition to identifying new drugs, efforts are being focused on repurposing the already approved drugs alone or in combination for the management of PC. Finally, extensive efforts are being undertaken to identify chemopreventive regimens to reduce the risk or curtail incidence of PC.

TABLE 1:

Marketed formulations for PC management

| Trade name | Active | Dosage form; administration route |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Abraxane® | Paclitaxel | Albumin-bound paclitaxel; intravenous infusion |

| Gemzar® | Gemcitabine | Injectable; injection |

| Fluorouracil | Fluorouracil | Injectable; injection |

| Onivyde® | Irinotecan | Liposomal injectable; intravenous infusion |

| Tarceva® | Erlotinib hydrochloride | Tablet; oral |

| Abraxane® + Gemzar® | paclitaxel, gemcitabine | Injectable |

| Tarceva®+ Gemzar® | Erlotinib hydrochloride, gemcitabine | Oral; injectable |

| Folfirinox® | Folinic acid (leucovorin), fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin | Injectable |

TABLE 2:

Clinical trial status of new drugs/formulations for PC management

| Clinical study | Active | Indication | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Global phase III clinical study to begin-HALO pancreatic 301 | Pegvorhyaluronidase alfa (PEGPH20) in combination with paclitaxel (Abraxane®) and gemcitabine (Gemzar®) | PC | 102 |

| Phase III clinical study | Olaparib | Patients with BRCA mutated metastatic PC with no disease progression upon platinum-based chemotherapy | 103 |

| Phase I/II study to begin | Ribociclib and trametinib | Solid tumors, PC/colorectal cancer | 104 |

| Phase III study to begin | AM0010 and FOLFOX | Second-line treatment for PC which has progressed even with gemcitabine | 5 |

| Phase III study-MAESTRO study | Evofosfamide (TH-302) and gemcitabine | Unresectable PDAC | 105 |

| PEGPH20 safety study | Gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel, PEGPH20 and rivaroxaban | Advanced PDAC | 5 |

| Pilot study | Ascorbic acid and folfirinox | Advanced PDAC | 5 |

| Phase 0 Pilot study | Gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel, cisplatin, and anakinra | Potentially resectable PDAC | 5 |

| Phase I study | Onivyde, 5-FU, and xilonix | Advanced PC with cachexia | 5 |

| Phase I trial study | Disulfiram and gemcitabine | Solid tumor and PC | 5 |

| Phase I study | Defactinib, pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine | Advanced PC | 5 |

| Phase Ib dose-escalation study | Palbociclib and nab-paclitaxel | PDAC | 5 |

| Phase I study | Gemcitabine and pulse dose erlotinib in | Second line treatment of advanced PC | 5 |

| Phase I/II study | RX-3117 and Abraxane® | Metastatic PC | 5 |

| Phase Ib study | Nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine with or without olaratumab | Metastatic PC | 5 |

| Phase II study | BPM31510 (Ubidecarenone, USP) nanosuspension with or without gemcitabine | Advanced PC | 5 |

As per published reports, the median survival of metastatic PC patients is extremely low (< 1 year) when treated with first-line gemcitabine combinations and Folfirinox® (a drug cocktail of fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin). This necessitates the use of second-line drug therapy in addition to the existing first-line drug care. In this context, the NAPOLI-1 clinical study has shown significant prolongation of progression-free survival and overall survival in patients treated with second-line drug therapy with nanoliposomal irinotecan in combination with 5-fluorouracil. Based on these promising results, the nanoformulation-based second-line drug therapy was recently approved by the FDA and Onivyde® (liposomal formulation of irinotecan) has been on the market since October 2015.6

Despite available drug therapy and ongoing clinical investigations, the high prevalence and mortality associated with PC mean that there is an unmet chemopreventive and therapeutic need. From ongoing studies with various novel formulations, it is also clear that the development of smart drug delivery systems that will improve delivery of drug cargo to the pancreatic target site is of utmost important to ensure and enhance the therapeutic/chemoprevention efficacy of existing drugs and newly designed drugs in future.

Nanotechnology is emerging as a promising avenue to enhance drug delivery to the pancreas via both passive and active targeting mechanisms. Research in this field has grown extensively over the past decade and is evident from the growing number of publications in scientific literature. This review provides a timely summary of the recent advances in pharmaceutical nanoformulations in attempts to accomplish the unmet chemopreventive and therapeutic need in the field of PC management.

II. RECENT UPDATES ON PC PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND AVAILABLE DRUG TARGETS

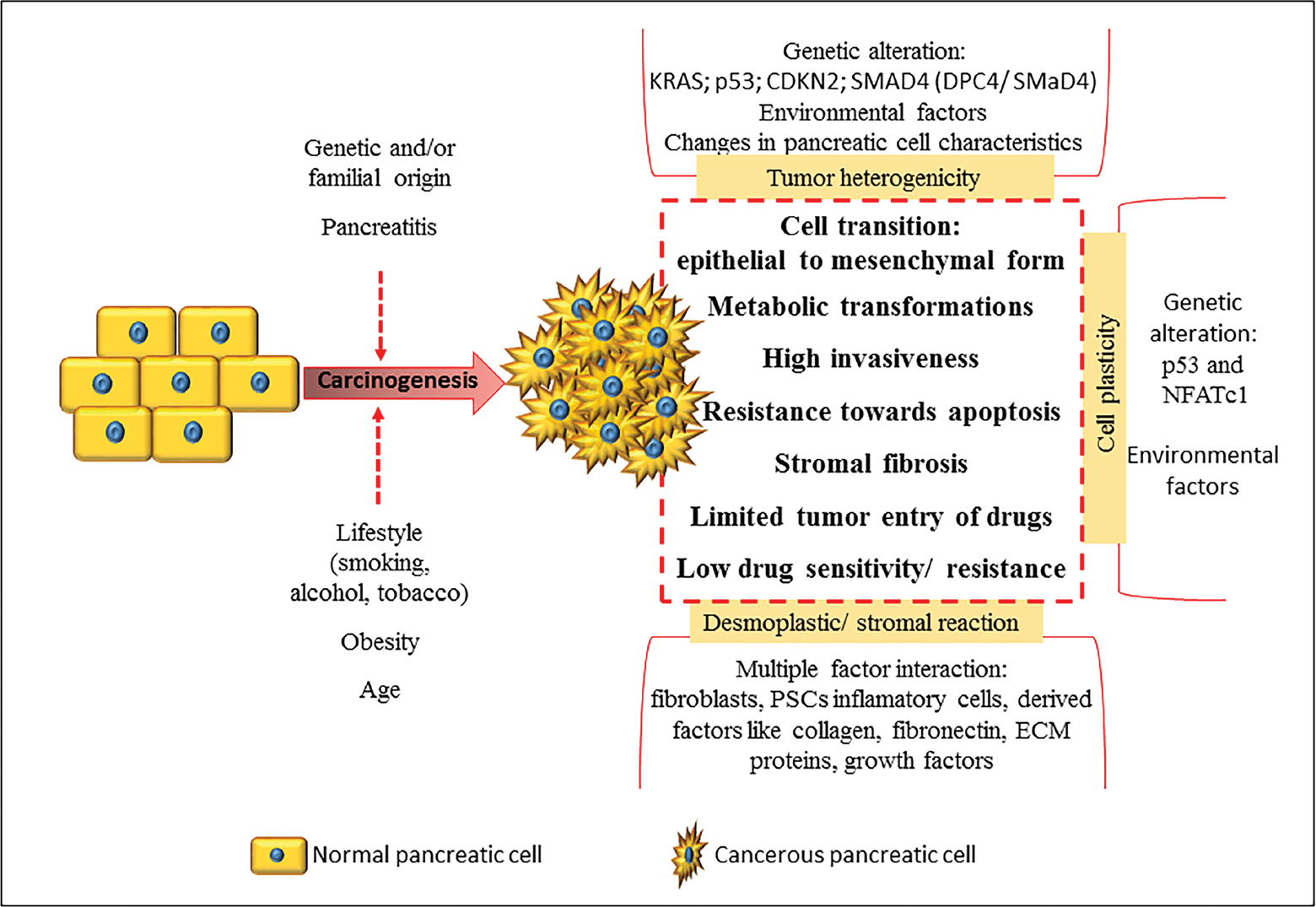

PC is a highly aggressive metastatic cancer associated with significant tumor heterogenicity, increased cancer cell plasticity, and classical desmoplastic/stromal reaction. Key features of PC pathophysiology are summarized in Fig. 1. There exists two major cell types in the pancreas: endocrine cells and exocrine cells. PC type is decided based on the specific cell type neoplasticity. Of the two types of PC, exocrine cancer is predominant, accounting for > 95% of reported cases, and begins in the exocrine cells responsible for formation of digestive pancreatic enzymes. In the majority of the cases, it is a malignant adenocarcinoma commonly known as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).4 PDAC classically shows presence of typical precursor lesions including: pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (most common), mucinous cystic neoplasm, and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.2,7 Other less prevalent but common types of exocrine PCs are acinar cell carcinoma, intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (Table 3).7 The endocrine pancreatic tumor that accounts for < 5% of cases is known as a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET) or islet cell tumor because it associates with pancreatic islet cells (primary function: glucose homeostasis) tumorigenesis. This type of cancer grows slowly and is less aggressive than the PDAC type. In most scenarios, PNET is nonfunctional (devoid of hormone production), but in some cases, it is functional (hormone producing), which makes it highly critical due to an imbalance in glucose homeostasis (Table 3).2,7,8

FIG. 1:

Key features of PC pathophysiology

TABLE 3:

Overview of various types of PCs

| PC Type | Key features |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Exocrine | |

|

| |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Prevalence: > 95% of reported cases Presence of typical precursor lesions viz. pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (most common), mucinous cystic neoplasm, and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm Highly aggressive |

| Acinar cell carcinoma | Vary rare type Possibility of excessive pancreatic lipase secretion |

| Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm | Pancreatic duct carcinoma (grows from main pancreatic duct or branches of the duct) Main duct carcinoma is more severe Potential precursor of PDAC |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | Rare type Type of cystic tumor More commonly observed in tail of pancreas Predominant in women |

|

| |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pancreatic NETs or PNETs)/islet cell tumors | |

|

| |

| Prevalence: < 5% of reported cases Less aggressive than PDAC Can be functional (produce hormones) or nonfunctional (produce no hormones) Majority are nonfunctional tumors |

|

Pancreatic tumor-associated heterogenicity can be both phenotypic and/or functional and results from genetic factors, environmental factors, and changes in pancreatic cell characteristics. Among these, genetic heterogenicity is very critical as it can lead to mutations of oncogenes and tumor supressor genes that affect multiple signaling pathways. For example, a genomic investigation on 24 pancreatic carcinomas have confirmed alteration in > 63 genes, which affects a minimum of 12 signaling pathways.9 Among these, the most common PDAC-associated mutations are KRAS (90% tumors), p53 gene (75% tumors), inactivation of p16 protein encoding CDKN2 gene (95% tumors), and mutation or deletion of SMAD4 gene (DPC4/SMaD4).8,10–13

Cancer cells possess high cell plasticity (i.e., the ability to transform to adapt the extreme tumor environment) predominantly involving transition from epithelial to mesenchymal form and metabolic transformations. These changes confer specific phenotype properties to the cancer cells such as high invasiveness, resistance toward apoptosis, etc. The cell plasticity mainly results from genetic alterations (p53 and NFATc1 signaling activity), but changes in environmental factors have also been reported as a possible reason.8,14

Classical desmoplastic/stromal reaction is a key histopathological aspect of PC that results from multiple factor interaction that involves fibroblasts, pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), inflammatory cells, and derived factors such as collagen, fibronectin, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, various growth factors, etc. Among these, PSCs are the critical hurdle limiting delivery of antineoplastic drugs to the pancreatic tumor cells. PSCs are activated by PC cells to undergo morphological and functional changes. This results in excessive formation and deposition of ECM that causes fibrosis of pancreatic stroma. Stromal fibrosis creates a conducive environment facilitating tumor growth and also plays a critical role in distant metastasis. Further, the stromal fibrosis limits delivery of drugs at the tumor site, resulting in low drug sensitivity and resistance in some cases. Therefore, over time, PSCs and associated stroma have emerged as a potential target to retard the pancreatic tumorigenesis and to improve the efficacy of overall PC therapy by increasing tumor sensitivity toward antineoplastic drugs.15–18 PC cells show up-regulation of various growth factors that induce tumorigenesis and play a part in stromal reaction. These factors include transforming growth factor-β, hepatocyte growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and connective tissue growth factor.16–18 Interestingly, inhibitors of these upregulated growth factors have been reported as potential targets for drug therapy and for the development of targeted drug delivery systems.

In view of such a multifaceted pathophysiology, various drug targets have been identified for PC prevention and therapy. Currently available drugs on the market, drugs undergoing clinical studies and active research are listed in Table 4, along with their proposed mechanism of action toward PC management. Among the available drugs, gemcitabine is currently considered the preferred drug for treatment of PC.

TABLE 4:

Drugs investigated for PC management

| Nucleoside analogs |

| • Gemcitabine and derivatives |

| • 5-Fluurouracil |

| Mitotic inhibitor |

| • Paclitaxel |

| Enzyme modulators/suppressors/inhibitors |

| • Irinotecan (topoisomerase I inhibitor) |

| • SN38 - active metabolite of irinotecan (topoisomerase I inhibitor) |

| • Doxorubicin (topoisomerase II inhibitor) |

| • 9-Nitrocamptothecin (topoisomerase I inhibitor) |

| • Bortezomib (proteasome inhibitor) |

| • Baicalin (caspase inhibitor) |

| • Ormeloxifene (selective estrogen receptor modulator, desmoplasmic suppressor) |

| • MMP-2 responsive peptide (interference with metalloprotease 2) |

| • GDC-0449 (hedgehog pathway inhibitor) |

| • Pirfenidone (collagen synthesis inhibitor used to overcome stromal barrier) |

| • Mitomycin-C (DNA synthesis inhibitor) |

| • 17-N-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin [heat shock protein 90 (HSP 90) inhibitor] |

| • Sulforaphane (HSP 90 interference) |

| • Ellagic acid (NF-κB inhibitor) |

| Photodynamic therapy |

| • Cathepsin E-sensitive prodrug |

| Gene/siRNA delivery |

| • TR3 siRNA |

| • siRNA of NGF |

| Miscellaneous |

| • Cromolyn (anti-inflammatory) |

| • Ibuprofen (anti-inflammatory, chemoprevention) |

| • Aspirin (anti-inflammatory, chemoprevention) |

| • Curcumin and derivatives [anti-inflammatory, chemoprevention, inhibitor of oxidative stress and angiogenesis and reduction of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP)] |

III. NANOFORMULATION INTERVENTIONS FOR PC MANAGEMENT

In addition to the drug potency, real-time therapeutic efficacy of any drug depends upon various other factors such as stability, absorption, distribution, metabolism, toxicity, specific delivery at therapeutic site, drug resistance, and route of administration. Interestingly, whereas drug potency against a specific target is a fixed response, other parameters can be modified and controlled to a desirable level to enhance the overall chemopreventive/therapeutic efficacy of the drug using various strategies. These strategies include chemical modifications such as the development of prodrug, drug conjugates, salts, and adducts and physical modifications such as the development of special drug delivery systems, alteration in route of administration, concurrent use of drug metabolism inhibitors, and use of absorption enhancers. In this context, nanotechnology-based formulations are revolutionizing the field of drug delivery and are undergoing extensive research. These formulations offer various advantages such as small nanometric size, large surface area, incorporation of both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs, stabilization of encapsulated drug, biocompatibility, long circulation time, controlled and sustained release, possibility of active targeting allowing site specific drug delivery, and enhanced tumor delivery via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Additionally, nanotechnology-based formulations have shown promise in overcoming specific drug delivery challenges associated with PC chemoprevention and therapy, such as limited pancreatic tumor specific drug delivery, low drug sensitivity and high resistance, stromal barrier, high toxicity, and poor pharmacokinetic performance.

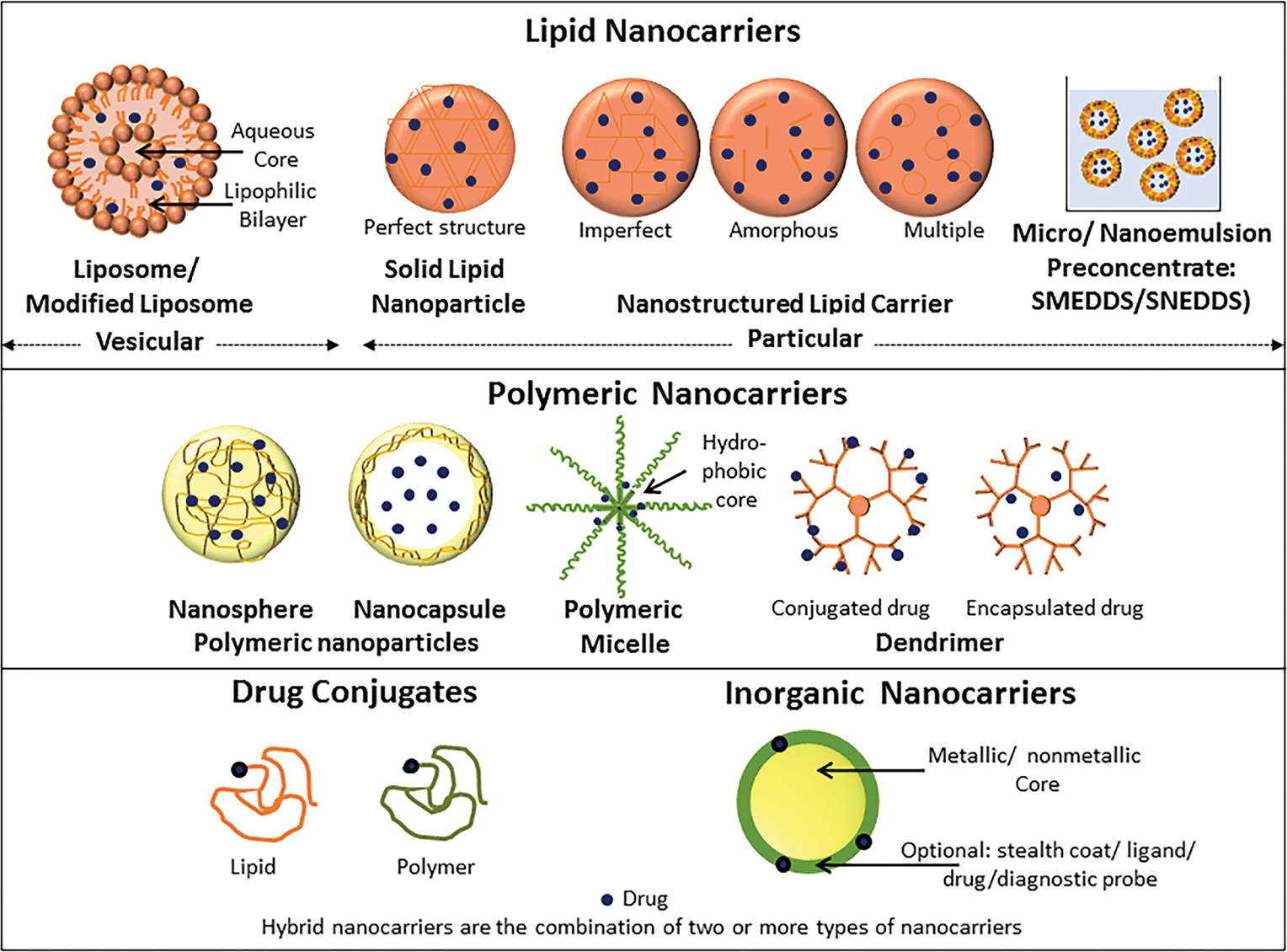

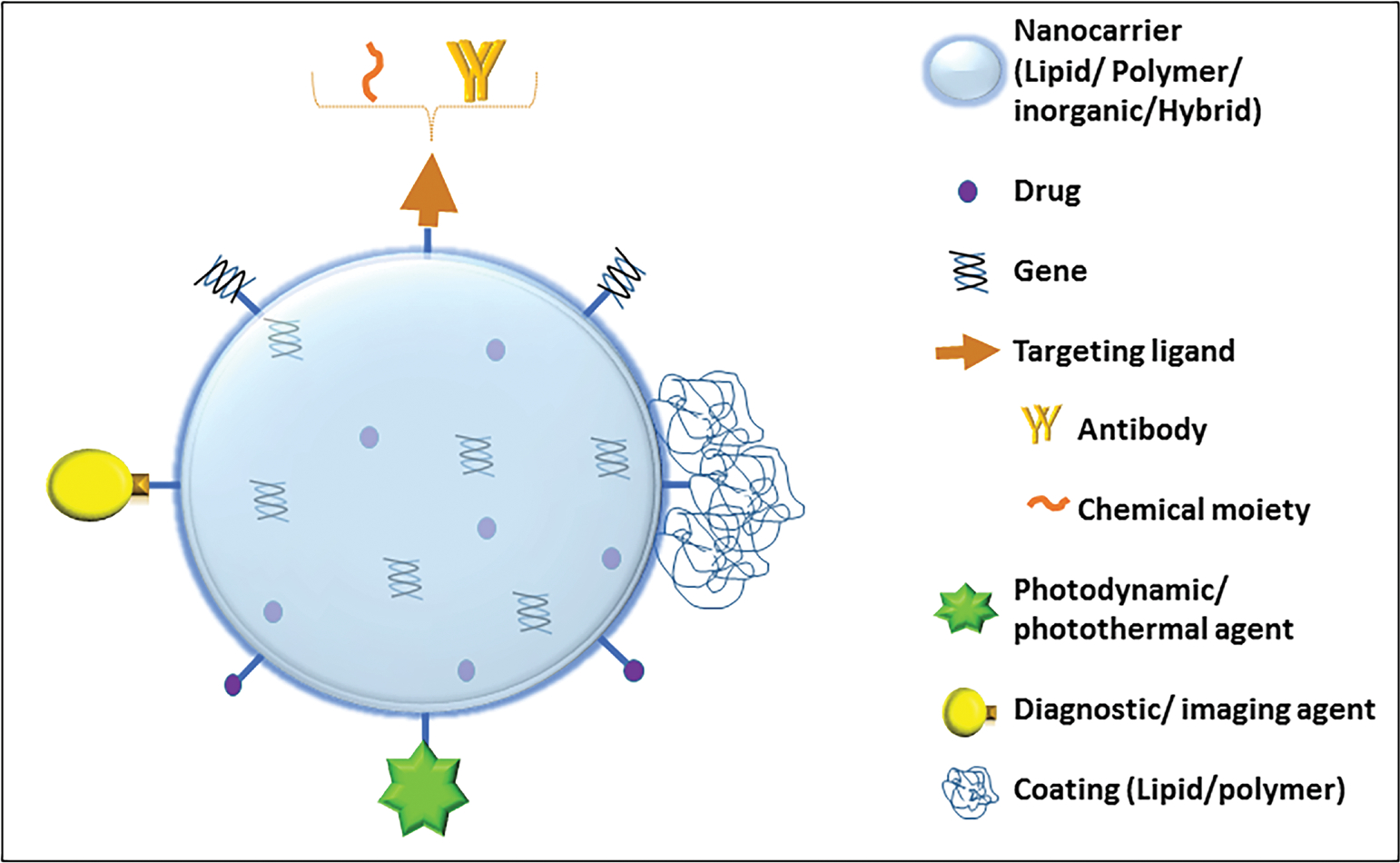

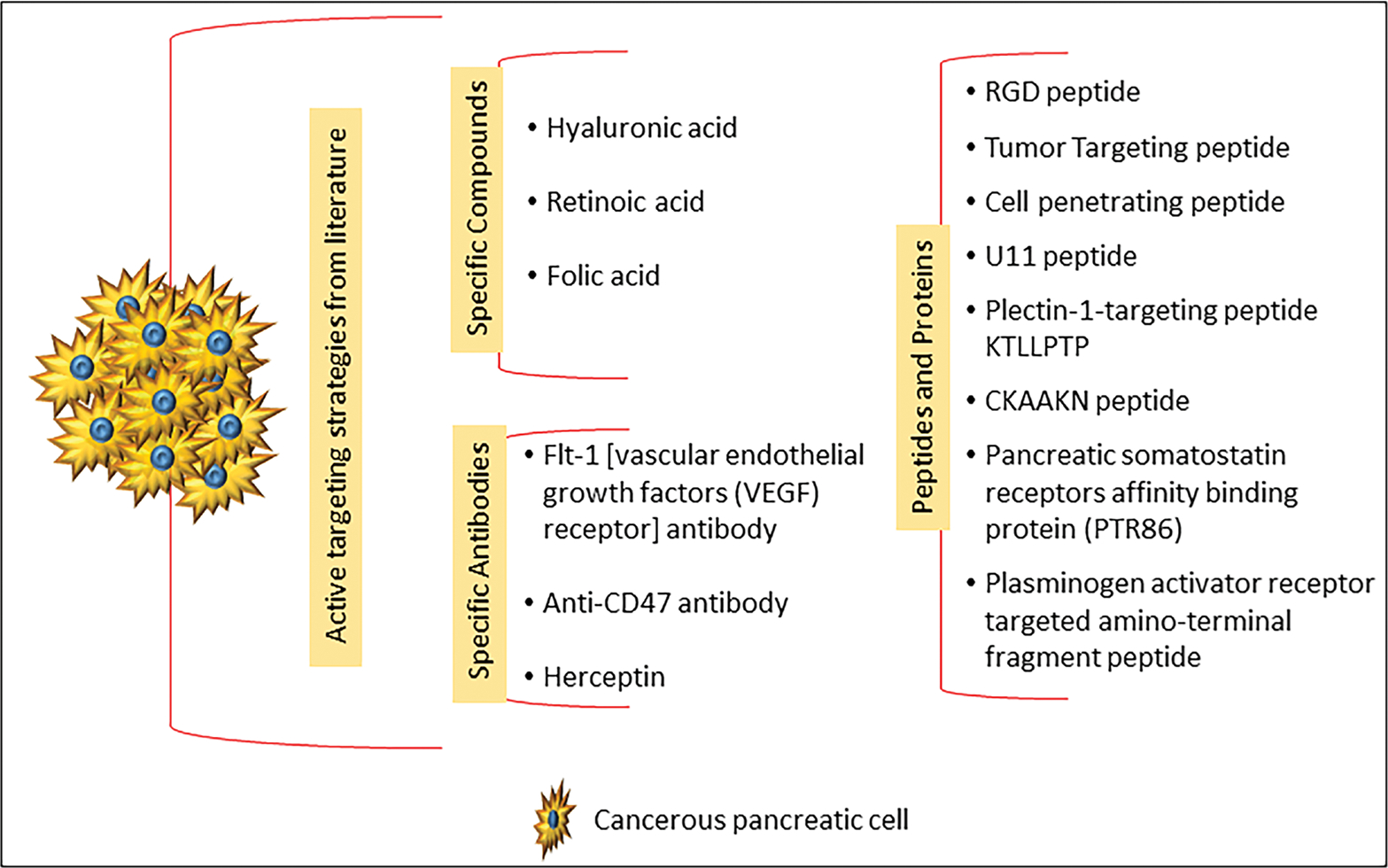

Various types of nanoformulations include lipid nanocarriers, polymeric nanocarriers, inorganic nanocarriers, nanoassembled drug conjugates/prodrugs, and hybrid nanoparticles (i.e., a combination of two or more types of nanocarriers); these are represented in Fig. 2.19,20 Figure 3 depicts schematically the targeted and multifunctional nanodelivery systems that are gaining importance due to their unique properties of selective pancreatic delivery. An extensive list of conventional (non-active targeted) and active targeted nano-therapeutics investigated for PC chemoprevention and therapy is given in Tables 5 and 6, respectively, and these are discussed below. Figure 4 summarizes various active targeting ligands explored for the development of active targeted nanoparticles for PC management. The trend shows that researchers are focusing extensively on the development of novel active targeted nanoformulations for PC management.

FIG. 2:

Schematic representation of various types of nanocarriers. (Figure modified and used with permission from Patravale and Desai19 and Desai et al.20)

FIG. 3:

Schematic representation of multifunctional (targeted/theranostic/hybrid) nanocarriers The figure represents various design approaches for building nanoparticles. This includes use of different targeting ligands, excipient types, diagnostic agents, and drugs. The nanoparticle is designated as a “targeted nanoparticle” when it comprises an active targeting ligand to elicit targeted pancreatic delivery; as a “hybrid nanoparticle” when it comprises a combination of more than one type of excipient such as a lipid, polymer, or inorganic construct; and as a “multifunction nanoparticle” when it comprises more than one of the above represented strategies

TABLE 5:

Conventional nanocarriers of PC management

| Active | Drug delivery system | Key feature | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Lipid nanocarriers | |||

|

| |||

| Gemcitabine | Liposomes | Improved pharmacokinetic performance High tumor targeting |

26 |

| Irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil | Liposomes | Clinical study proved significantly prolonged overall survival period | 6 |

| Ellagic acid –HAS complex | Liposomes | Effective against fibrotic stroma and tumor-promoting PSCs in PDAC Enhanced apoptosis and tumor growth inhibition |

25 |

| MMP-2-responsive peptide and pirfenidone | Liposomes | Antifibrosis effect at tumor site Increased sensitivity toward gemcitabine |

22 |

| Gemcitabine | PEGylated liposomes | High entrapment efficacy and drug loading High stability |

106 |

| Curcumin | Long-circulating liposome | Increased loading efficacy and stability Enhanced anticancer activity in PDAC model cell lines |

24 |

| Cromolyn | PEGylated liposomes | Prolonged circulation | 29 |

| Cromolyn and gemcitabine | PEGylated liposomes | Prolonged circulation Enhanced anticancer efficacy in bxpc-3 PC cell lines and the bxpc-3 tumor-bearing nude mice |

29 |

| 9-Nitrocamptothecin | SMEDDS | Size: < 40 nm Enhanced pharmacokinetic performance Enhanced efficacy in tumor xenograft model |

41 |

| Baicalin | Phospholipid complex - SMEDDS | Enhanced oral bioavailability | 42 |

| D07001-F4 | SMEDDS | Enhanced oral bioavailability Enhanced efficacy in xenograft model |

40 |

| Curcumin | SMEDDS | Size: 21 nm Enhanced oral bioavailability Increased passive diffusion across intestinal |

39 |

| Ibuprofen and free sulforaphane | SLN | Up to 4 fold dose reduction Enhanced antiproliferative activity because of regulation of p50 subunit of NF-κB DNA-binding activity Chemoprevention |

36 |

| Aspirin, curcumin and sulforaphane | SLN | Size: 150–250 nm Synergistic anticancer efficacy Chemoprevention |

107 |

| Aspirin, curcumin, and sulforaphane | SLN | Synergistic efficacy upon oral administration Significant reduction in tumor incidence in 24 week study Chemoprevention |

108 |

| Paclitaxel | PEGylated SLN | Enhanced stability Enhanced uptake |

37 |

|

| |||

| Polymeric nanocarriers | |||

|

| |||

| Gemcitabine | PLGA nanospheres | Size: 180 nm Sustained drug delivery over a period of 41 days Low IC50 MiaPaCa-2 and ASPC-1 PC cell lines compared with free drug |

45 |

| Anthothecol | PLGA nanoparticles | Apoptotic potential in pancreatic cell cultures and PC stem cells | 49 |

| Ormeloxifene | PLGA nanoparticles | Size: ~100 nm Uptake by EPR effect High animal survival in bxpc-3 xenograft mice model compared with plain drug |

46 |

| Curcumin | PLGA-PEG-PLGA triblock copolymeric micelles | Size: 26.29 nm Superior pharmacokinetic profile |

48 |

| 3,4-Difluorobenzylidene curcumin | Styrene-maleic acid co-polymer self-assembling nanomicelles | Enhanced in vitro intracellular uptake Efficient anticancer activity in Mia-PaCa-2 and AsPC-1 PC cell lines |

55 |

| SN38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and GDC-0449 (hedgehog pathway inhibitor) | Polymeric nanoparticles | Enhanced anticancer activity | 58 |

| Gemcitabine and paclitaxel | Polymeric micelles | Thermoresponsive micelles allowing tumor-specific drug release | 59 |

|

| |||

| Inorganic nanocarriers | |||

|

| |||

| Gemcitabine | Mesoporous silica vesicles | Increased uptake in PC cell lines High drug loading |

70 |

| siRNA of NGF | Gold nanocluster | Stabilization of the siRNA Prolongation of circulation time in vivo Augmented tumor site uptake Anticancer efficacy of this assembly was proved in PANC1 PC cell line with visible Down-regulation of NGF gene Promising efficacy in subcutaneous, orthotopic, and patient-derived xenograft model of PC |

75 |

|

| |||

| Drug conjugates | |||

|

| |||

| Squalenoyl prodrug of 5′-monophosphate gemcitabine | Self-assembly | Reduced metabolism Increased tumor sensitivity |

76 |

| Stearoyl gemcitabine | Polymeric micelles and self-assembling nanoparticles | Significantly high cytotoxicity in Panc-1 and AsPC-1 cell lines | 77 |

| Vitamin E succinate–gemcitabine | Colloidal suspension | Increased stability 4.7-fold higher tumor inhibition rate compared with gemcitabine alone |

78 |

| Gemcitabine–cholesterol | Liposome | Prolonged drug release Enhanced antitumor effect in H22 and S180 tumor models |

23 |

| Paclitaxel–albumin conjugate | Self-assembly | Enhanced drug permeation and efficacy Enhanced antitumor efficacy in clinical study |

79–81 |

| Mitomycin-C lipid-based prodrug | PEGylated liposomes | Better pharmacokinetic performance Reduced drug toxicity High tumor regression compared with gemcitabine in Panc-1 model |

28 |

| Gemcitabine–PLGA conjugate | Enhanced apoptosis and anticancer activity in vitro | 83 | |

| Gemcitabine-conjugated cationic co-polymers and tumor suppressor miRNA-205 (miR-205) | Reversal of chemoresistance Enhanced tumor inhibition in vivo |

85 | |

|

| |||

| Hybrid nanocarriers | |||

|

| |||

| Gemcitabine and HIF1α siRNA | Lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles | Reduced drug resistance Synergistic antitumor efficacy |

92 |

| Gemcitabine triphosphate | Lipid/calcium/phosphate nanoparticle | Enhanced antiproliferative activity | 94 |

| 17-N-allylamino-17-de-methoxygeldanamycin (17AAG) | Polymeric and inorganic nanoparticles | Higher safety better circulation time Enhanced efficacy |

95 |

| Bortezomib and gemcitabine | PEGylated lipid-coated gold nanoshells | Infrared laser triggered treatment Enhanced anticancer activity Efficacy in resistant pancreatic carcinoma |

73 |

|

| |||

| Theranostic (simultaneous diagnostic and therapeutic potential) nanocarriers | |||

|

| |||

| Therapy and diagnosis: doxorubicin | Dextran coated magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | Simultaneous detection and therapeutic efficacy Enhanced efficacy |

97 |

| Therapy and diagnosis: gemcitabine prodrug heptamethine cyanine (1–3) derivatives | Prodrug conjugate | Enhanced uptake by folate-positive cancer cell lines | 109 |

TABLE 6:

Targeted nanocarriers of PC management

| Active | Targeting strategy | Drug delivery system | Key feature | Reference no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Lipid nanocarriers | ||||

|

| ||||

| Pirfenidone and gemcitabine | RGD peptide, MMP-2-responsive liposome | β-cyclodextrin adapted liposome | Liposomes disassembly into two functional parts after cleavage by MMP-2 Part 1: β-cyclodextrin with pirfenidone (antifibrosis drag) to taiget PCSs allowing stoma targeting Part 2: RGD peptide linked liposome with gemcitabine to target pancreatic tumor cells |

27 |

| Gemcitabine lipophilie prodrug [4-(N)-lauroyl-gemcitabine, C12GEM] | Hyaluronic acid | Liposomes | Overexpressed pancreatic adenocarcinoma CD44 receptor targeting Enhanced pancreatic carcinoma cell line uptake with targeted liposomes than non-targeted liposomes Liposomal uptake increases with increase in molecular weight of targeting ligand Enhanced cytotoxicity with the prodrug compared with plain drug |

30 |

| Gemcitabine | Hyaluronic acid | Liposomes | Overexpressed pancreatic adenocarcinoma CD44 receptor targeting Enhanced tumor sensitivity toward gemcitabine Higher antitumor efficacy with targeted liposomes |

31 |

| Gemcitabine-stearic acid prodrug and hyaluronic acid-baicalin conjugate | Hyaluronic acid | NLC | Targeted NLCs exhibited enhanced cytotoxicity against aspc1 PC cell line Maximized antitumor effect in murine model |

38 |

| - | Apolipoprotein A-II | Lipid nanovesicles | Enhanced PC targeting 3.4-fold uptake enhancement in xenograft model |

43 |

| - | Hypoxia-responsive lipid | lipid-peptide conjugate Nano assembly | Reduction of functional lipid at tumor hypoxic site causing destabilization followed by drag release Enhanced anti-proliferative activity in hypoxic bxpc-3 spheroid carcinoma cell lines |

44 |

|

| ||||

| Polymeric nanocarriers | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gemcitabine | Herceptin | Chitosan nanoparticles | Significant increase in anti-proliferative activity and apoptosis than non-targeted chitosan nanoparticles | 50 |

| Gemcitabine | Folate receptor targeting using folic acid | Chitosan core-shell nanoparticles | Excellent antitumor activity in xenograft model | 54 |

| Curcumin | Folate | Poly-lactic acid–PEG micelles | Size: 80–86 nm Enhanced the drug encapsulation efficiency based on the poly-lactic acid to PEG ratio |

56 |

| Paclitaxel | TRAIL | Albumin nanoparticles | Size 170–230 nm Targeted nanoparticles exhibited significant anticancer activity in vivo with almost 4-fold reduction in tumor volume and weight compared with plain nanoparticles |

57 |

| Doxorubicin | Folic acid and the AS1411 aptamer | Polymeric (poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate)-poly(caprolactone)-poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) nanoparticles | Size of ~ 140 nm Significant enhancement in anticancer activity with targeted nanoparticles with higher payload in PANC-1 cell line |

110 |

| Gemcitabine | Folate | Albumin nanoparticles | Higher anticancer efficacy with targeted nanoparticles only in folate-expressing cancer cell lines | 111 |

| Paclitaxel and TR3 small interfering RNA | Tumor-targeting peptide | Dendrimer | Enhanced endosomal escape mechanism Enhanced uptake and antitumor efficacy |

61 |

| Gene delivery | Cell-penetrating peptide | Third-generation poly-L-lysine dendrigraft | Size: 110.9 ± 7.7 nm Enhanced uptake in tumor stroma |

64 |

| Gemcitabine | Flt-1 (VEGF receptor) antibody | PEG-cored PAMAM dendrimers | Size: < 300nm Enhanced in vivo anticancer efficacy with significant accumulation of formulation at tumor site |

63 |

| 3, 4-Difluorobenzylidene curcumin | Hyluronic acid | PAMAM dendrimer | Size: 9.3 ± 1.5 nm 1.71 fold higher anticancer activity in CD44 overexpressed MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 human PC cell lines compared with non-targeted drug loaded dendrimers |

60 |

|

| ||||

| Inorganic nanocarriers | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gemcitabine | Anti-CD47 antibody | Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles | Excellent in vitro efficacy CD47-positive PC cell line | 68 |

| Carbachol (neural activity activator) and atropine (neural activity depressor) It was observed that | Transferrin receptor 1 targeting with EPR effect | Ferritin nanoparticles | Carbachol induced tumor progression, whereas atropine impaired tumor progression Confirmed potential of ferritin nanoparticles in delivery of neural drags for anti-cancer therapy |

67 |

| 5-Flurouracil | Hyaluronic acid | Silver-graphene quantum nanocomposites with carboxymethyl inulin | Reduced toxicity Enhanced anticancer activity |

69 |

| Cathepsin E | U11 peptide | Gold nanocluster | Enhanced apoptosis compared with non-targeted gold nanoclusters Increased tumor accumulation with targeted nanoclusters Therapy module for endomicroscopy guided photodynamic therapy of PDAC |

71 |

| Gemcitabine | Plectin-1-targeting peptide KTLLPTP | Gold nanoparticles | potentiated anticancer activity was observed with targeted nano assemblies and significant improvement in anticancer efficacy was established in orthotopic PANC-1 xenograft model with selective PDAC targeting | 72 |

|

| ||||

| Drug conjugates | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gemcitabine-squalenoyl prodrug | CKAAKN peptide | Squalene conjugated nanoparticles | Targeted uptake by cancerous cells and angiogenic vessels Selective anticancer activity against PC |

84 |

|

| ||||

| Hybrid nanocarriers | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gemcitabine | Retinoic acid, magnetic nanoparticles | Retinoic acid targeted PAMAM dendrimer coated magnetic nanoparticles | Dual targeting of cancer cells and stellate cells Enhanced uptake |

65 |

| Irinotecan | Cyclic tumor-penetrating peptide iRGD | Lipid bilayer coated mesoporous silica targeted nanoparticles (silicasomes) | Enhanced uptake and efficacy in xenograft model | 93 |

| Gemcitabine | Folic acid | pH-sensitive PEGylated dendritic hybrid nanocarrier comprising mesoporous silica, graphene oxide and magnetite | Enhanced anticancer efficacy | 112 |

| Gemcitabine | Laser irradiation induced linker breakdown | Hybrid nanoparticles | Drug conjugated hybrid nanoparticles Reduced toxicity Enhanced cellular uptake and resulting cytotoxicity Enhanced efficacy in tumor xenograft model |

113 |

| Gemcitabine | Gold nanoshell allowing photothermal effect upon mild near infrared irradiation | Gold nanoshell-coated rodlike mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Enhanced penetrate through the fibrotic stroma of pancreatic tumor Deep tumor deposition of gemcitabine Enhanced chemotherapeutic potential of gemcitabine by photothermal effect after mild near-infrared laser irradiation |

74 |

|

| ||||

| Theranostic (simultaneous diagnostic and therapeutic potential) nanocarriers | ||||

|

| ||||

| Therapy: gemcitabine Diagnosis: multispectral optoacoustic tomography |

Urokinase plasminogen activator and chitosan | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | Ex vivo and in vivo studies confirmed targeted delivery of drug payload at pancreatic tumor sites with possible tomography assisted diagnosis | 96 |

| Therapy: gemcitabine Diagnosis: magnetic iron oxide |

Plasminogen activator receptor targeted amino-terminal fragment peptide | Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | Significant inhibition of orthotopic human PC xenografts in nude mice | 98 |

| Therapy: gemcitabine Diagnosis: fluorescent dyes (dual MRI/optical imaging modality) |

Pancreatic somatostatin receptors affinity binding protein (PTR86) | Magnetic nanoworms | Enhanced efficacy in in vivo xenograft mouse model with human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and ex vivo studies | 99 |

FIG. 4:

Schematic representation of various active targeting ligands explored in the literature for the development of active targeted nanoparticles for PC management

A. Lipid Nanocarriers

Lipid nanocarriers have been studied over the decades for effective delivery of PC therapeutic actives and chemopreventive drugs. These are discussed below.

1. Lipid Vesicular Nanocarriers

Lipid vesicular nanocarriers such as liposomes and exosomes allow the incorporation of both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs. Among these, liposomes are widely studied for delivery of various PC chemopreventive and therapeutic agents such as irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, ellagic acid, curcumin, pirfenidone, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) responsive peptide (stellate cells regulator), etc.6,21–26 In addition, long-circulating nanoliposomes of irinotecan (Onivyde®, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) have also been approved by the FDA in combination with fluorouracil and leucovorin for PC patients who have been treated earlier with gemcitabine chemotherapy as first-line treatment.6

Ji et al.22,27 have reported liposomes comprising MMP-2-responsive peptide and pirfenidone to specifically release the drug at pancreatic tumor site. The actives herein regulate the PSCs and thereby reduce excessive secretion of ECM in tumor stroma. This leads to antifibrosis effect at tumor stromal site overcoming the resistance and enhancing the tumor sensitivity toward drugs such as gemcitabine. Therefore, this approach can be postulated as a way forward to treat ECM-overexpressed pancreatic tumors.22,27

Human serum albumin (HSA) nanoparticles of paclitaxel have shown enhanced penetration in the pancreatic tumor matrix but suffer from poor blood retention. To overcome this drawback, a paclitaxel HSA complex (~9 nm) has been incorporated in the hydrophilic core of thermoresponsive liposomes. Additionally, ellagic acid HSA complex was incorporated in same liposomal matrix to allow combination drug therapy. The developed system showed enhanced accumulation at the tumor site with augmented tumor matrix permeation leading to significant apoptosis and tumor growth inhibition.25

As an advancement, a polyethylene glycol (PEG) modification known as PEGylation of liposomes has been executed to reduce protein adsorption and to further enhance their circulation time. Examples of various drugs investigated for pancreatic tumor delivery via a PEGylated liposomal carrier include cromolyn, gemcitabine, and mitomycin-C.28,29 In this context, cromolyn was encapsulated in PEGylated liposomes that showed an almost 4.5-fold lower protein adsorption compared with non-PEGylated liposomes, indicating prolonged circulation. The same investigators incorporated gemcitabine with cromolyn in PEGylated liposomes, which exhibited promising cytotoxicity in BxPC-3 PC cell lines (in vitro study) and BxPC-3 tumor-bearing nude mice (in vivo study), confirming the potential of proposed strategy.29

Liposomes present a superior platform for delivery of drugs to pancreatic tumors via passive transport. The efficacy of this delivery platform can be further potentiated by means of active targeting. In view of this, targeted liposomes and immunoliposomes (antibody-conjugated liposomes) for pancreatic tumor targeting have been developed and studied for the delivery of drugs such as gemcitabine.30,31 Gemcitabine liposomes conjugated with hyaluronic acid to target CD44 receptors on pancreatic tumor were reported. The studies showed highest sensitivity of CD44-expressing PDAC cell line toward targeted liposomes than non-targeted liposomes and was further corroborated by an in vivo study showing higher antitumor efficacy with targeted liposomes. Interestingly, similar uptake of targeted and non-targeted liposomes was observed upon interaction with CD44 non-expressing pancreatic cell lines, confirming the selectivity of hyaluronic acid-based targeted nanoparticles toward CD44-overexpressed pancreatic tumors.31 Other examples of targeted liposomes include a β-cyclodextrin-adapted, MMP-2-responsive liposome comprising the anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone and the anticancer drug gemcitabine.27

Exosomes are endogenous membrane-based vesicles produced by cells and have multiple applications in various biological processes.32 Recently, milk-based exosomes (size: ~108 nm) of paclitaxel have been reported with enhanced antiproliferative activity and apoptosis in a lung tumor xenograft model and can be useful in the treatment of PC.33

Exosomes are extracellular vesicles derived from the cells that have been reported to act as mediators in cancer metastasis and have gained wide attention in recent years.34 Scientists are considering the options of using genetically engineered exosomes as PC treatment options because of their enhanced retention in the circulation and their superior cell transfection potential. For example, fibroblast-derived exosomes were engineered to incorporate oncogenic KrasG12D (PC mutation) specific short interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (iExosomes). These iExosomes exhibited higher circulation time compared with liposomes, which was attributed to CD47-assisted protection against phagocytosis. Further, in a mouse model, iExosomses showed increased suppression in PC with higher survival.35

2. Lipid Particulate Nanocarriers

Likewise, lipid vesicular nanocarriers and lipid particulate nanocarriers have also shown promising potential in PC management. Generally, lipid particulate nanocarriers are considered as options of choice for delivery of lipophilic and poorly bioavailable drugs. Various types of lipid particulate nanocarriers include solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), micro/nanoemulsions, and self-micro/nano-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS/SNEDDS).

SLNs of ibuprofen have been reported alone and in combination with sulforaphane as PC chemoprevention strategy. The studies showed higher antiproliferative activity of ibuprofen SLNs compared with ibuprofen alone, with a 4-fold dose reduction potential. The combination drug treatment further augmented the anti-proliferative activity and was assigned to down-regulation of p50 subunit of NF-κB DNA-binding activity.36 Interestingly PEGylated SLNs of paclitaxel have also been reported with enhanced in vivo uptake and longer circulation time.37 NLCs of PC therapeutic actives such as gemcitabine and baicalin prodrugs have been reported.38 For example, targeted NLCs comprising gemcitabine–stearic acid prodrug and hyaluronic acid–baicalin conjugate were formulated. Here, hyaluronic acid played a role as active targeting ligand that facilitated tumor-specific drug delivery. Targeted NLCs exhibited enhanced cytotoxicity against the AsPC1 PC cell line and showed a maximized antitumor effect in murine model.38

Enhancing oral bioavailability of poorly bioavailable actives is a key challenge and lipid based emulsification of such Biopharmaceutics Classification System class II and IV drugs is reported to enhance their uptake and in turn oral bioavailability.20 The reported nanoformulations in this category include micro/nanoemulsions and their preconcentrate forms such as SMEDDS and SNEDDS. SMEDDS of drugs such as 9-nitrocamptothecin, baicalin, gemcitabine, D07001-F4, and curcumin have been formulated to enhance their oral pharmacokinetics.39–42 For instance, the topoisomerase I inhibitor drug 9-nitrocamptothecin was developed as a SMEDDS with a size of < 40 nm and showed enhanced pharmacokinetic performance and efficacy in a xenograft model.41

Use of specialized or functionalized lipids to form targeted lipid nanodrug delivery systems is also on the forefront. For example, apolipoprotein A-II has potential of spontaneously forming lipid nanovesicles, which have been reported to enhance PC targeting of lipid nanocarriers for diagnostic and therapeutic application43. In another investigation, lipid nanoparticles comprising a synthesized hypoxia-responsive lipid and a lipid–peptide conjugate were formulated to target the deep tumor hypoxic sites that are predicted to increase angiogenesis and tumor progression. The designed lipid nanoparticles underwent reduction in hypoxic condition followed by lipid destabilization, releasing the drug cargo at tumor hypoxic sites and causing tumor apoptosis. The studies confirmed the enhanced antiproliferative activity in hypoxic BxPC-3 spheroid carcinoma cell lines.44

B. Polymeric Nanocarriers

Polymeric nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and dendrimers have shown intriguing potential to deliver PC chemopreventive and therapeutic drugs and are discussed below.

1. Polymeric Nanoparticles and Micelles

Among various biocompatible and biodegradable polymers, poly (D,L)-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) as a polymer for nanocarriers development has gained wide attention due to its sustained release properties along with its biodegradability and biocompatibility. Various actives such as gemcitabine, 5-flurouracil, curcumin, anthothecol, and ormeloxifene have been incorporated in PLGA-based nanocarriers for PC management.45–49 Gemcitabine-loaded nanospheres with 15% drug encapsulation efficiency showed a sustained release over a period of 41 days to release 100% drug in phosphate-buffered saline. Further, the formulation exhibited preferential uptake in the MiaPaCa-2 PC cell line over a period of 3 h with higher cytotoxicity compared with the plain drug.45 In another investigation, anthothecol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were formulated. Interestingly, these nanoparticles exhibited apoptotic potential, not only against pancreatic cell cultures, but also against PC stem cells. The stem cell apoptosis was thought to result from a multicascade pathway that inhibited the stem cell self-renewal potential.49

Chitosan-based polymeric nanoparticles have also made advances in the research arena for the management of PC. Chitosan bears a positive charge in physiological fluids because of its amino functionalities and can be used at an advantage for targeted drug delivery applications. Chitosan also exhibits bioadhesive properties in addition to biocompatibility, biodegradability, and high permeability, which makes it suitable for drug delivery application. Chitosan nanoparticles of gemcitabine, quercetin, 5-fluorouracil, metformin, etc., have shown enhanced antitumor efficacy compared with the plain drug.50–54 For example, targeted chitosan nanoparticles of gemcitabine with herceptin as targeting ligand were associated with a significant increase in antiproliferative activity and apoptosis than non-targeted chitosan nanoparticles and the plain drug.50 In another investigation, folate-targeted chitosan nanoparticles of gemcitabine were observed to perform excellent antitumor activity in a xenograft model.54

Various other polymeric nanoparticles have also been researched. For example, a poorly soluble chemopreventive and anticancer drug, 3,4-difluorobenzylidene curcumin, was incorporated in in-house-designed styrene–maleic acid co-polymer self-assembling nanomicelles. The nanomicelles exhibited size of 69.9 ± 7.7 nm (Polydispersity Index of 0.274 ± 0.08) with significant in vitro intracellular uptake and efficient anticancer activity in MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 PC cell lines.55 Curcumin-loaded poly-lactic acid–PEG micelles with folate as a targeting agent (80–86 nm) were developed and compared against a non-targeted micellar formulation. The micelles enhanced the drug encapsulation efficiency based on the poly-lactic acid to PEG ratio with enhanced in vitro cell line cytotoxicity potential.56 Targeted albumin bound paclitaxel nanoparticles with size 170–230 nm have also been reported. The targeting moiety here was tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL). The targeted nanoparticles exhibited significant anticancer activity in vivo with an almost 4-fold reduction in tumor volume and weight compared with plain nanoparticles.57

Combination drug therapy is evolving as a better PC management strategy to overcome drug resistance. In a recent study, polymeric nanoparticles for co-delivery of SN38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and GDC-0449 (hedgehog pathway inhibitor) were developed with significant anticancer efficacy both in vitro and in vivo.58 In another study, thermoresponsive polymeric micelles encapsulating gemcitabine and paclitaxel for targeted combination drug therapy were developed. The polymeric micelles exhibited lower critical solution temperature above the body temperature. This characteristic allowed thermo-reversible hydrophilic to hydrophobic phase transformations and could be tuned to release the drug by means of temperature stimulus causing micellar disruption at the tumor site.59

2. Dendrimers

Dendrimers as nanocarriers for delivery of actives such as gemcitabine, 3,4-difluorobenzylidene curcumin, paclitaxel, TR3 siRNA, gene, and fluorescent dyes such as Alexa Fluor 555 have been investigated as a promising approach to enhancing delivery to the tumor site via passive transport and active targeting.60–65 In one study, Flt-1 (VEGF receptor)-antibody conjugated PEG-cored PAMAM dendrimers were formulated for targeted delivery of gemcitabine. The drug was incorporated as an inclusion complex with dendrimer and the assembly exhibited size < 300 nm. The in vivo anticancer study revealed a significant accumulation of formulation at tumor site with enhanced efficacy.63 In other investigations, a fourth-generation PAMAM dendrimer with conjugated hyaluronic acid as a targeting ligand at CD44 receptor in PC was studied for the delivery of 3,4-difluorobenzylidene curcumin. The targeted dendrimers (size: 9.3 ± 1.5 nm and surface charge: −7.02 ± 9.53 mV) showed 1.71-fold higher anticancer activity in CD44-overexpressed MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 human PC cell lines compared with non-targeted drug-loaded dendrimers; this was supported by fluorescence studies confirming comparative higher cell line uptake of targeted dendrimers.60

C. Inorganic Nanocarriers

Inorganic nanoparticles are also being explored as an opportunity for PC management.66 Among inorganic nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles are being studied extensively because they allow targeted delivery of drugs at tumor site due to their magnetic properties and can additionally be tagged with specific targeting ligands. Examples of drugs studied for delivery via magnetic nanoparticles include gemcitabine, carbachol, and atropine.67,68 For instance, multifunctional targeted iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles with active targeting ligand anti-CD47 antibody (PC cells and cancer stem cells present anti-phagocytosis signal CD47 receptor) and gemcitabine as an anticancer drug were developed. The formulation exhibited excellent in vitro efficacy in a CD47-positive PC cell line.68

Arresting PC progression is one key challenge that needs to be addressed proactively. In this context, ferritin nanoparticles with both passive (EPR effect) and active (transferrin receptor 1 binding) targeting potential were developed with an ability to release drug in the acidic tumor microenvironment. To understand the performance of ferritin nanoparticles, two drugs, carbachol (neural activity activator) and atropine (neural activity depressor), were incorporated and studied for their effect on tumor progression. It was observed that carbachol induced tumor progression significantly, whereas atropine impaired tumor progression, confirming the potential of ferritin nanoparticles for the delivery of neural drugs for pancreatic anticancer therapy.67

Other inorganic nanoparticles investigated for PC management include quantum dots, silica nanoparticles, and gold nanoparticles. For example, silver–graphene quantum nanocomposites comprising carboxymethyl inulin to reduce cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles were developed. Further, hyaluronic acid was grafted on nanocomposite as a targeting moiety for site-specific PC delivery. The developed system was assessed for its efficacy using 5-flurouracil as a model drug and was reported to exhibit enhanced anticancer potential.69 In another study, mesoporous silica vesicles (MSVs) were incorporated with gemcitabine and became internalized by the BxPC-3 (human) and Pan02 (mouse) PC cell lines. Further, superior anticancer activity was seen with drug-loaded MSVs compared with drug alone and the non-cytotoxicity of plain MSVs was proven.70 Gold nanocarriers in combination with drugs have been reported to offer simultaneous chemotherapy and photothermal therapy for PC.71–74 The therapeutic actives investigated for delivery via gold nanocarriers include anticancer drugs such as gemcitabine, photothermally activated prodrugs such as cathepsin E, and gene therapeutics such as siRNA.71,74,75 In one study, actively targeted gold nanoparticles were developed to offer additional tumor-specific delivery of drug payload. Plectin-1-targeting peptide KTLLPTP-grafted gold nanoparticles were fabricated to ensure targeted delivery of gemcitabine to PDAC. A potentiated anticancer activity was observed with targeted nanoassemblies and significant improvement in anticancer efficacy was established in an orthotopic PANC-1 xenograft model with selective PDAC targeting.72 Further, an interesting four-component nanosystem was reported comprising photodynamic therapy carrier gold nanocluster, U11 peptide (active targeting ligand), cathepsin E (photodynamic therapy-sensitive prodrug), and cyanine dye Cy5.5 (cathepsin E sensitive imaging moiety). The targeted gold nanoclusters exhibited enhanced apoptosis compared with non-targeted gold nanoclusters with increased tumor accumulation. This strategy is postulated to offer a promising therapy module for endomicroscopy-guided photodynamic therapy of otherwise difficult to target PDAC.71 Gold nanoclusters incorporated with siRNA of nerve growth factor (NGF) to cause tumor suppression by inhibition of NGF gene expression have also been developed. Interestingly, gold nanocluster stabilized the siRNA, but also prolonged its circulation time in vivo and augmented tumor site uptake. The anticancer efficacy of this assembly was proved in the PANC1 PC cell line with visible down-regulation of NGF gene. In addition, efficacy was promising in a subcutaneous, orthotopic, and patient-derived xenograft model of PC.75 Considering the fact that genetic heterogenecity is most commonly observed in PC, the gold nanoassemblies for gene delivery can emerge as a future for PC therapy.

D. Drug Conjugates

Although gemcitabine is considered a gold standard in PC treatment, its efficacy is compromised by fast metabolism by blood deaminases and cell chemoresistance development. To overcome this, various gemcitabine conjugates that have potential to increase the tumor cell sensitivity toward gemcitabine have been investigated. Among these is a squalenoyl prodrug of 5′-monophosphate gemcitabine. This amphiphilic prodrug exhibited self-assembling properties to form nanomicellar structures. In the in vitro cell line studies, prodrug resulted in higher antiproliferative activity and cytotoxicity compared with the native drug and it was predominant in case of chemoresistant pancreatic cell lines, confirming the potential of the proposed strategy. The results were further supported by in vivo efficacy studies with similar findings.76

Prodrugs enhance drug efficacy and their activity can be further enhanced using suitable nanocarriers. For example, a prodrug stearoyl gemcitabine was formulated as poly-lactic acid–PEG polymeric micelles and self-assembled prodrug nanoparticles. The polymeric micelles exhibited small size (~120 nm) compared with self-assembled nanoparticles (~300 nm) and both micelles and nanoparticles exhibited significantly high cytotoxicity compared with plain prodrug solution when assessed for in vitro cytotoxicity assay using the Panc-1 and AsPC-1 PC cell lines.77 In another study, a vitamin E succinate-gemcitabine prodrug was synthesized and co-assembled with D-α-tocopheryl PEG succinate to form stable colloidal suspension in an isotonic solution for intravenous administration. In an in vivo antitumor efficacy study, the formulation revealed a 4.7-fold higher tumor inhibition rate compared with gemcitabine alone and the efficacy was attributed to higher stability of prodrug.78 Li et al.23 incorporated gemcitabine-cholesterol conjugate in liposomal nanocarriers (112.57 ± 1.25 nm) to prolong circulation time compared with free gemcitabine. Their studies proved that the liposomal drug conjugate exhibited higher antitumor efficacy in H22 and S180 tumor compared with free drug.23

Stromal barrier and resulting impaired drug permeation is a major challenge in PDAC management. To overcome this, conjugation of drugs to the moieties with higher affinity toward overexpressed stromal cell receptors is proposed as a promising approach. For instance, albumin has excellent affinity toward overexpressed SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) in PDAC. In view of this, paclitaxel has been protein conjugated to form albumin nanoparticles (nab-paclitaxel), which have shown enhanced drug permeation and efficacy and have also been studied to enhance efficacy in combination with gemcitabine. In addition, the potential and therapeutic efficacy of this combination was confirmed in a clinical investigation.79–81 Studies have confirmed that nab-paclitaxel is taken up by the cells using the macropinocytosis process and this pathway can be looked upon as a future avenue for drug delivery.80,82

A similar approach (drug–polymer covalent conjugates) can be used to address multiple issues such as enhancement of otherwise low drug loading of polymeric nanocarriers, imparting stability to otherwise unstable drugs. For example, gemcitabine was covalently linked to a PLGA polymer that showed increased drug stability in plasma. Further, the in vitro studies in multiple cells lines such as MIAPaCa-2 (PC), MCF-7 (breast cancer), and HCT-116 (colon cancer) confirmed enhancement in apoptosis and thus are a promising approach in the clinical setting for solid tumor treatment.83 Peptide (CKAAKN peptide as targeting agent)-conjugated squalene nanoparticles with gemcitabine prodrug (squalenoyl prodrug) have been reported to target carcinoma cells and angiogenic vessels specifically, allowing selective anticancer activity against PC.84 Self-assembling gemcitabine-conjugated cationic co-polymers in combination with the tumor suppressor miRNA-205 (miR-205) were also formulated. The combination therapy reversed chemoresistance with significant tumor inhibition in vivo.85

E. Hybrid Nanocarriers

Each type of nanocarrier exhibits some unique properties and also some limitations, as described briefly below. Lipid vesicular nanocarriers such as liposomes exhibit a unique platform for incorporation of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, but drug loading and entrapment can be challenging. Further, liposomes may present relatively faster clearance via the reticulo-endothelial system and need modification to elicit stealth properties (long circulating time).86–88 Polymeric nanoparticles offer advantages such as sustained delivery over a long period ranging from few days to months when prepared using the PLGA type of polymers and a polymer coat such as PEG. However, in some polymers, biocompatibility and in vivo polymer degradation, clearance, and safety need thorough investigation.45–49,87,89,90 Inorganic nanoparticles allow easy targeting and a simultaneous diagnosis opportunity, but may pose more safety concerns compared with biocompatible lipid and polymeric nanocarriers.67,68,75,91 Therefore, a symbiotic combination of two or more nanoparticles can allow integration of their advantages and may also help in overcoming individual drawbacks, resulting in more advantageous hybrid nanocarriers. With this hypothesis, extensive studies have been reported using hybrid nanocarriers for PC management, opening new avenues toward PC chemoprevention and treatment in the near future.

The biocompatibility and endogenous nature of lipids have been used at an advantage to combine them with other types of nanocarriers. For example, lipid polymer hybrid nanoparticles comprising cationic ε-polylysine co-polymer coated with PEGylated lipid were investigated for co-delivery of gemcitabine and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) siRNA. The hypothesis here was that HIF1α leads to increased drug resistance to first-line pancreatic anticancer drugs, by using HIF1α siRNA, the drug resistance toward first-line drugs such as gemcitabine could be reversed. Both in vitro and in vivo studies confirmed that HIF1α expression was suppressed with siRNA and exhibited synergistic antitumor efficacy.92 Lipid bilayer-coated mesoporous silica-targeted nanoparticles (silicasomes) of irinotecan have been reported. The targeting ligand in these was the cyclic tumor-penetrating peptide iRGD targeting the transcytosis transport pathway regulated by neuropilin-1. The targeted silicasomes exhibited enhanced uptake in a xenograft model.93

Lipid/calcium/phosphate nanoparticles of gemcitabine triphosphate were reported to arrest the cell cycle in the S phase with enhanced anti-proliferative activity in a preclinical study.94 For example, PEGylated lipid (long circulating)-coated gold nanoshells loaded with two drugs bortezomib and gemcitabine have been reported for PC management. Interestingly, the developed system revealed drug release only upon near infrared laser treatment, making site-specific delivery possible. The results were extremely promising in terms of anticancer activity and the therapy is postulated to be effective also in case of resistant pancreatic carcinoma.73

A combination of polymeric and inorganic nanoparticles has also been reported. In one study, magnetic nanoparticles with HSP90 as the drug (17-N-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) coated with PLGA were developed and showed promising anticancer efficacy against the MIA PaCa-2 cell line. Here, the polymeric coat imparts higher safety and better circulation time, but at the same time, it compromises the magnetic strength, so optimizing polymer coat concentration is a critical factor in such combination nanoparticles.95

Multiple inorganic nanoparticles can be used to take advantage of their individual properties to form multifunctional hybrid inorganic nanocarriers. For instance, gold nanoshell coated rod-like mesoporous silica nanoparticles were developed that exhibited tumor-targeting potential by means of a photothermal effect and allowed incorporation of gemcitabine. The proposed plasmonic photothermal therapy was able to penetrate through the fibrotic stroma of pancreatic tumor, allowing gemcitabine delivery in deep tumor tissue and thus enhanced anticancer efficacy.74

F. Theranostic Nanocarriers

Nanoparticle-assisted simultaneous diagnosis and therapy (theranostic) application is considered the next generation in the scientific arena of nanotherapeutics. Such nanocarriers have been developed and are in the early research stage for PC management. For example, targeted mesoporous silica nanoparticles with theranostic potential have been reported. Tumor-specific targeting was achieved by a dual mechanism, a urokinase plasminogen activator that binds specifically to tumor upregulated urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and chitosan, which is sensitive to the acidic tumor microenvironment. The diagnosis was achieved via multispectral optoacoustic tomography and gemcitabine was used as a therapeutic agent. The ex vivo and in vivo studies confirmed the targeted delivery of drug payload at pancreatic tumor sites with possible tomography-assisted diagnosis.96 Recently, dextran-coated magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin were developed. An interesting feature of this nanoparticulate system was the strategic use of auto-fluorescence of anticancer drug doxorubicin that allowed simultaneous detection and therapeutic efficacy.97 Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor targeted magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, allowing MRI-assisted imaging with gemcitabine as a therapeutic agent.98

Targeted magnetic nanoworms with surface-linked fluorescent dyes (dual MRI/optical imaging modality) were developed. PC-cell-specific targeting was made possible using pancreatic somatostatin receptors affinity binding protein (PTR86) in conjunction with magnetic nanoparticles. The results showed efficacy in both an in vivo xenograft mouse model with human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and ex vivo studies. Such targeted nanoparticles can also be investigated for PC-targeted drug therapy or as theranostic agents to achieve simultaneous diagnosis and therapy.99

To summarize, nanoparticle-based products are being investigated extensively worldwide and, although few have made their entry into the market, many are in the preclinical research or clinical pipeline. The above sections describe nanotechnology-based products that have shown greater efficacy and potential in PC management. However, when developing these products, one must consider not only their efficacy but also their safety. As per FDA guidelines, safety and efficacy go hand in hand for clinically successful products, so detailed in vitro and in vivo safety evaluation of such novel products is highly warranted.100,101

IV. CONCLUSION

PC continues to be a deadly disease with very poor prognosis and low chance of survival. By 2025, this disease is predicted to be ranked second behind lung cancer in terms of prevalence and mortality. In addition to identifying new drugs, research efforts are being focused on repurposing and reformulating already approved drugs alone or in combination for management of PC. Within the last 4–5 years, nanotechnology-based formulations have garnered significant attention because emerging data suggest their viability as smart drug delivery systems with the potential of actively targeting pancreatic tissue to achieve efficacious outcomes at lowered toxicity. The current review provides recent updates on PC management, particularly in the area of nanoformulation development, which has grown extensively over a past decade as evident from the available scientific literature. It is anticipated that, based on current research being conducted, in the future, there will be an increase in FDA-approved nanoformulations, thereby providing the PC patient with an increased number of chemoprevention and treatment options to cure and/or prolong survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R15CA182834-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Market Data Forecast. Pancreatic cancer therapeutics market by treatment type (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, others), by type (exocrine pancreas cancer, endocrine pancreas cancer), by end users (hospitals, clinics, research institutes, others), by region: Global industry analysis, size, share, growth, trends, and forecasts (2016–2021) [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/global-pancreatic-cancer-market-1277/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiaravalli M, Reni M, O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: State-of-the-art 2017 and new therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;60:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf.

- 4.Grand View Research. Pancreatic cancer treatment market size worth $4.2 billion by 2025 [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-pancreatic-cancer-treatment-market.

- 5.Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. Clinical trials search [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.pancan.org/trials?searchMode=GeneralSearch.

- 6.Rahman FAU, Ali S, Saif MW. Update on the role of nanoliposomal irinotecan in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(7):563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. Types of pancreatic cancer [cited 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.pancan.org/facing-pancreatic-cancer/learn/types-of-pancreatic-cancer/.

- 8.Falasca M, Kim M, Casari I. Pancreatic cancer: Current research and future directions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1865(2):123–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, Seay T, Tjulandin SA, Ma WW, Saleh MN, Harris M, Reni M, Dowden S, Laheru D, Bahary N, Ramanathan RK, Tabernero J, Hidalgo M, Goldstein D, Van Cutsem E, Wei X, Iglesias J, Renschler MF. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attri J, Srinivasan R, Majumdar S, Radotra BD, Wig J. Alterations of tumor suppressor gene p16IN-K4a in pancreatic ductal carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271(5247):350–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohr M, Kloppel G, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Luttges J. Frequency of K–ras mutations in pancreatic intraductal neoplasias associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis: a meta–analysis. Neoplasia. 2005;7(1):17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarpa A, Capelli P, Mukai K, Zamboni G, Oda T, Iacono C, Hirohashi S. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas frequently show p53 gene mutations. Am J Pathol. 1993;142(5):1534–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sousa CM, Kimmelman AC. The complex landscape of pancreatic cancer metabolism. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(7):1441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apte MV, Wilson JS, Lugea A, Pandol SJ. A starring role for stellate cells in the pancreatic cancer microenvironment. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1210–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erkan M, Reiser–Erkan C, Michalski CW, Kleeff J. Tumor microenvironment and progression of pancreatic cancer. Exp Oncol. 2010;32(3):128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahadevan D, Von Hoff DD. Tumor–stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(4):1186–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips P Pancreatic stellate cells and fibrosis. In: Grippo PJ, Munshi HG, editors. Pancreatic cancer and tumor microenvironment. Trivandrum, India: Transworld Research Network; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patravale VB, Desai PP. Topical nanointerventions for therapeutic and cosmeceutical applications. In: Domb AJ, Khan W, editors. Focal controlled drug delivery. Boston, MA: Springer; 2014. p. 535–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai PP, Date AA, Patravale VB. Overcoming poor oral bioavailability using nanoparticle formulations: Opportunities and limitations. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2012;9(2):e87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graeser R, Bornmann C, Esser N, Ziroli V, Jantscheff P, Unger C, Hopt UT, Schaechtele C, von Dobschuetz E, Massing U. Antimetastatic effects of liposomal gemcitabine and empty liposomes in an orthotopic mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2009;38(3):330–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji T, Lang J, Wang J, Cai R, Zhang Y, Qi F, Zhang L, Zhao X, Wu W, Hao J, Qin Z, Zhao Y, Nie G. Designing liposomes to suppress extracellular matrix expression to enhance drug penetration and pancreatic tumor therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11(9):8668–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T, Chen L, Deng Y, Liu X, Zhao X, Cui Y, Shi J, Feng R, Song Y. Cholesterol derivative–based liposomes for gemcitabine delivery: preparation, in vitro, and in vivo characterization. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43(12):2016–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmud M, Piwoni A, Filipczak N, Janicka M, Gubernator J. Correction: long-circulating curcumin–loaded liposome formulations with high incorporation efficiency, stability and anticancer activity toward pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines in vitro. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei Y, Wang Y, Xia D, Guo S, Wang F, Zhang X, Gan Y. Thermosensitive liposomal codelivery of HSA-paclitaxel and HSA-ellagic acid complexes for enhanced drug perfusion and efficacy against pancreatic cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interf. 2017;9(30):25138–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang F, Jin C, Jiang Y, Li J, Di Y, Ni Q, Fu D. Liposome based delivery systems in pancreatic cancer treatment: from bench to bedside. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(8):633–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji T, Li S, Zhang Y, Lang J, Ding Y, Zhao X, Zhao R, Li Y, Shi J, Hao J, Zhao Y, Nie G. An MMP-2 responsive liposome integrating antifibrosis and chemotherapeutic drugs for enhanced drug perfusion and efficacy in pancreatic cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfa. 2016;8(5):3438–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabizon A, Amitay Y, Tzemach D, Gorin J, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. Therapeutic efficacy of a lipid-based prodrug of mitomycin C in pegylated liposomes: studies with human gastro-entero-pancreatic ectopic tumor models. J Control Release. 2012;160(2):245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim CE, Lim SK, Kim JS. In vivo antitumor effect of cromolyn in PEGylated liposomes for pancreatic cancer. J Control Release. 2012;157(2):190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arpicco S, Lerda C, Dalla Pozza E, Costanzo C, Tsapis N, Stella B, Donadelli M, Dando I, Fattal E, Cattel L, Palmieri M. Hyaluronic acid-coated liposomes for active targeting of gemcitabine. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85(3 Pt A):373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalla Pozza E, Lerda C, Costanzo C, Donadelli M, Dando I, Zoratti E, Scupoli MT, Beghelli S, Scarpa A, Fattal E, Arpicco S, Palmieri M. Targeting gemcitabine containing liposomes to CD44 expressing pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells causes an increase in the antitumoral activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828(5):1396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ha D, Yang N, Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes: current perspectives and future challenges. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6(4):287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agrawal AK, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Spencer WA, Beck J, Gachuki BW, Alhakeem SS, Oben K, Munagala R, Bondada S, Gupta RC. Milk-derived exosomes for oral delivery of paclitaxel. Nanomedicine. 2017;13(5):1627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong EA, Beal EW, Chakedis J, Paredes AZ, Moris D, Pawlik TM, Schmidt CR, Dillhoff ME. Exosomes in pancreatic cancer: from early detection to treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(4):737–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamerkar S, LeBleu VS, Sugimoto H, Yang S, Ruivo CF, Melo SA, Lee JJ, Kalluri R. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;546(7659): 498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thakkar A, Chenreddy S, Wang J, Prabhu S. Evaluation of ibuprofen loaded solid lipid nanoparticles and its combination regimens for pancreatic cancer chemoprevention. Int J Oncol. 2015;46(4):1827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arranja A, Gouveia LF, Gener P, Rafael DF, Pereira C, Schwartz S Jr, Videira MA. Self-assembly PEGylation assists SLN-paclitaxel delivery inducing cancer cell apoptosis upon internalization. Int J Pharm. 2016;501(1–2):180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Z, Su J, Li Z, Zhan Y, Ye D. Hyaluronic acid-coated, prodrug-based nanostructured lipid carriers for enhanced pancreatic cancer therapy. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43(1):160–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui J, Yu B, Zhao Y, Zhu W, Li H, Lou H, Zhai G. Enhancement of oral absorption of curcumin by self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2009;371(1–2):148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao WH, Wang JJ, Hsueh SP, Hsu PJ, Chang LC, Hsu CS, Hsu KY. In vitro and in vivo studies of pharmacokinetics and antitumor efficacy of D07001–F4, an oral gemcitabine formulation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(2):379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu JL, Wang JC, Zhao SX, Liu XY, Zhao H, Zhang X, Zhou SF, Zhang Q. Self–microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) improves anticancer effect of oral 9–nitrocamptothecin on human cancer xenografts in nude mice. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;69(3):899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu H, Long X, Yuan F, Chen L, Pan S, Liu Y, Stowell Y, Li X. Combined use of phospholipid complexes and self–emulsifying microemulsions for improving the oral absorption of a BCS class IV compound, baicalin. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2014;4(3):217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Julovi SM, Xue A, Thanh LT, Gill AJ, Bulanadi JC, Patel M, Waddington LJ, Rye KA, Moghaddam MJ, Smith RC. Apolipoprotein A-II plus lipid emulsion enhance cell growth via SR-B1 and target pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkarni P, Haldar MK, Katti P, Dawes C, You S, Choi Y, Mallik S. Hypoxia responsive, tumor penetrating lipid nanoparticles for delivery of chemotherapeutics to pancreatic cancer cell spheroids. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27(8):1830–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaidev LR, Krishnan UM, Sethuraman S. Gemcitabine loaded biodegradable PLGA nanospheres for in vitro pancreatic cancer therapy. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2015;47:40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan S, Chauhan N, Yallapu MM, Ebeling MC, Balakrishna S, Ellis RT, Thompson PA, Balabathula P, Behrman SW, Zafar N, Singh MM, Halaweish FT, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Nanoparticle formulation of ormeloxifene for pancreatic cancer. Biomaterials. 2015;53:731–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masloub SM, Elmalahy MH, Sabry D, Mohamed WS, Ahmed SH. Comparative evaluation of PLGA nanoparticle delivery system for 5-fluorouracil and curcumin on squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;64:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song Z, Feng R, Sun M, Guo C, Gao Y, Li L, Zhai G. Curcumin-loaded PLGA-PEG-PLGA triblock copolymeric micelles: Preparation, pharmacokinetics and distribution in vivo. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2011;354(1):116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verma RK, Yu W, Singh SP, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Anthothecol-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles inhibit pancreatic cancer stem cell growth by modulating sonic hedgehog pathway. Nanomed. 2015;11(8):2061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arya G, Vandana M, Acharya S, Sahoo SK. Enhanced antiproliferative activity of Herceptin (HER2)-conjugated gemcitabine-loaded chitosan nanoparticle in pancreatic cancer therapy. Nanomed. 2011;7(6):859–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.David KI, Jaidev LR, Sethuraman S, Krishnan UM. Dual drug loaded chitosan nanoparticles: Sugarcoated arsenal against pancreatic cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerf. 2015;135:689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snima KS, Jayakumar R, Unnikrishnan AG, Nair SV, Lakshmanan VK. O-carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles for metformin delivery to pancreatic cancer cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;89(3):1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trickler WJ, Khurana J, Nagvekar AA, Dash AK. Chitosan and glyceryl monooleate nanostructures containing gemcitabine: potential delivery system for pancreatic cancer treatment. AAPS PharmSci-Tech. 2010;11(1):392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu S, Xu Q, Zhou J, Wang J, Zhang N, Zhang L. Preparation and characterization of folate-chitosangemcitabine core-shell nanoparticles for potential tumor–targeted drug delivery. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13(1):129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kesharwani P, Banerjee S, Padhye S, Sarkar FH, Iyer AK. Parenterally administrable nano-micelles of 3,4-difluorobenzylidene curcumin for treating pancreatic cancer. Colloids Surf B Biointerf. 2015;132:138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phan QT, Le MH, Le TT, Tran TH, Xuan PN, Ha PT. Characteristics and cytotoxicity of folate-modified curcuminloaded PLA-PEG micellar nano systems with various PLA:PEG ratios. Int J Pharm. 2016. Jun 30;507(1–2):32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Min SY, Byeon HJ, Lee C, Seo J, Lee ES, Shin BS, Choi HG, Lee KC, Youn YS. Facile one-pot formulation of TRAIL-embedded paclitaxel-bound albumin nanoparticles for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Int J Pharm. 2015;494(1):506–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Liu X, Zhou Q, Sui M, Lu Z, Zhou Z, Tang J, Miao Y, Zheng M, Wang W, Shen Y. Terminating the criminal collaboration in pancreatic cancer: Nanoparticle-based synergistic therapy for overcoming fibroblast-induced drug resistance. Biomaterials. 2017;144:105–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emamzadeh M, Desmaële D, Couvreur P, Pasparakis G. Dual controlled delivery of squalenoyl-gemcitabine and paclitaxel using thermo-responsive polymeric micelles for pancreatic cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2017: e90–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]