Abstract

The biosynthetic gene cluster (12.3 kb) of mersacidin, a lanthionine-containing antimicrobial peptide, is located on the chromosome of the producer, Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 in a region that corresponds to 348° on the chromosome of Bacillus subtilis 168. It consists of 10 open reading frames and contains, in addition to the previously described mersacidin structural gene mrsA (G. Bierbaum, H. Brötz, K.-P. Koller, and H.-G. Sahl, FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 127:121–126, 1995), two genes, mrsM and mrsD, coding for enzymes involved in posttranslational modification of the prepeptide; one gene, mrsT, coding for a transporter with an associated protease domain; and three genes, mrsF, mrsG, and mrsE, encoding a group B ABC transporter that could be involved in producer self-protection. Additionally, three regulatory genes are part of the gene cluster, i.e., mrsR2 and mrsK2, which encode a two-component regulatory system which seems to be necessary for the transcription of the mrsFGE operon, and mrsR1, which encodes a protein with similarity to response regulators. Transcription of mrsA sets in at early stationary phase (between 8 and 16 h of culture).

Mersacidin is a tetracyclic peptide that is produced by Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 (9). It belongs to the family of lantibiotics, a group of lanthionine-containing peptides with antimicrobial activity (46). On the basis of differences in their structures, two types of lantibiotics have been distinguished, type A and type B lantibiotics (20). Mersacidin, actagardine, and the lantibiotics of the cinnamycin type constitute the latter group, which comprises rigid globular peptides with no net charge or a net negative charge. In contrast, type A lantibiotics are flexible, elongated peptides that act by forming pores in the bacterial membrane. Besides lanthionine, lantibiotics contain a number of rare amino acids, such as didehydroalanine, didehydrobutyrine, methyllanthionine, S-aminovinylcysteine, etc. In contrast to classical peptide antibiotics, lantibiotics are synthesized from precursor genes using the ribosomal pathway and the rare amino acids are introduced by posttranslational modification procedures into the lantibiotic precursor peptides. These so-called prepeptides consist of an N-terminal leader sequence and the C-terminal propeptide domain that is modified to be the lantibiotic. Several gene clusters of type A lantibiotics have been studied so far and found to comprise the structural gene, the enzymes that catalyze the modification reactions and accessory factors that confer export from the cell, regulation, and producer self-protection or immunity, a specific mechanism that protects the producing strain against the bactericidal action of its own lantibiotic (for recent reviews, see references 19 and 42). These gene clusters can be subdivided into two groups. The gene clusters of the strongly basic peptides, which possess a leader peptide with a conserved FNLD motif, contain two modification enzymes, LanB and LanC, involved in dehydration of hydroxy amino acids and thioether formation, respectively (42). (Lan is used as a collective locus symbol when homologous genes of different lantibiotic gene clusters are referred to.) These gene clusters also contain a LanT transporter and usually a separate LanP that acts as a leader peptidase. In contrast, the gene clusters of those peptides that carry no net charge or a single positive charge and are characterized by a leader peptide with a conserved double glycine cleavage site (GG-type leader peptide) possess a single LanM enzyme which is supposed to catalyze dehydration, as well as thioether formation, and a LanT transporter with an associated protease activity (42).

With respect to chemotherapeutic application, mersacidin is the most promising member of the type B lantibiotics, due to its in vivo activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (8). Like vancomycin, mersacidin acts by binding to lipid II, the ultimate peptidoglycan precursor, but its target is different from that of vancomycin, making mersacidin a lead structure of a new class of antibiotics (5, 7).

Genetic engineering of lantibiotics has been shown to be possible for several type A lantibiotics (25, 28) but requires the construction of a dedicated expression system that provides all of the enzymes and factors necessary to modify and export the lantibiotic peptide. The possibility of constructing such an expression system for modified mersacidin molecules with extended antibiotic spectra or increased efficacy prompted us to explore the mersacidin biosynthetic gene cluster. Here we present for the first time the complete sequence of a gene cluster of a type B lantibiotic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

For isolation of DNA, the mersacidin producer Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 (9) was grown in 45 ml of tryptic soy broth at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 1. For mersacidin production experiments, a synthetic medium (2) was employed. Antibacterial activity was determined in an agar diffusion assay with Micrococcus luteus ATCC 4698 as the indicator strain. Quantitation of mersacidin by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography was performed as described previously (2). Escherichia coli 71-18, E. coli BHM 71-18 mutS (51), Bacillus subtilis W23 (3), and Staphylococcus carnosus TM 300 (45) were used as cloning hosts and cultivated in the presence of the appropriate antibiotics on tryptic soy agar, in tryptic soy broth, or in Luria-Bertani medium. B. subtilis W23 was checked for the presence of the mersacidin biosynthetic gene cluster by PCR using primers 1 (see below) and 3 (5′-TATAAATCAAATTTAACAAATACATTCAG-3′), which anneals to the four last codons of mrsA; however, mrsA could not be detected. E. coli strains were transformed by electroporation, and staphylococci and bacilli were subjected to protoplast transformation (15, 16). Determination of MICs was performed by a microtiter plate assay with half-concentrated Mueller-Hinton broth.

Isolation of chromosomal DNA and cloning techniques.

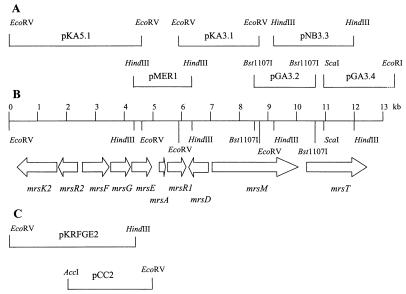

Chromosomal DNA from Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 was purified using Genomic-Tips 500/G in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). All genetic manipulations were performed as described previously (43) or in accordance with the recommendations of the supplier (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). After determination of the sequences downstream and upstream of mrsA (2) on pMER1 (see Fig. 1A), restriction digests of chromosomal DNA were hybridized with 18- to 22-bp digoxigenin-labeled oligonucleotides that had been derived from pMER1. Those fragments that gave a positive hybridization signal were cut out from the agarose gels, eluted with a BIOTRAP (Schleicher & Schüll, Dassel, Germany), and ligated into pUC18+ (49). All of the sequencing clones of the gene cluster that were generated by this and subsequent chromosome walking steps, as well as the inserts of plasmids that were constructed to probe the transcription of mrsFGE, are shown in Fig. 1A and C. pKRFGE2 contained an additional 0.73-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment covering the C terminus of mrsE which, however, is located downstream of mrsK2 so that mrsE is not reconstituted in this plasmid.

FIG. 1.

Mersacidin biosynthetic gene cluster. (A) Inserts of sequencing clones. (B) Organization of the gene cluster. The arrows indicate relative directions of transcription. (C) Inserts of plasmids constructed for transcription experiments with mrsFGE.

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

E. coli plasmid DNA was purified by the method of Felichiello and Chinali (13). A total of 14,190 bp of double-stranded DNA was sequenced on both strands by a primer-walking strategy using synthetic oligonucleotides labeled with the A.L.F.express dATP labeling mixture, an A.L.F.express sequencer, and A.L.F.express AutoRead sequencing kits (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) (22, 44). The PCGene program package (version C 6.01; IntelliGenetics, Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) was employed for DNA and protein analysis. The FASTA software was used for protein similarity searches and identification of known protein sequence patterns (34).

Northern analysis.

The isolation of total RNA from staphylococci was performed employing the QIAGEN RNeasy total RNA kit as described previously (32). For Bacillus preparations, the cells were lysed for 15 min at 37°C after addition of 2 mg of lysozyme per ml and 7 μl of RNase block RNase inhibitor (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) per ml. The following steps were performed in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturers. A 60-μl volume of the eluates was precipitated with LiCl and ethanol and resuspended in 7 μl of demineralized water. The total RNA was then denatured with formaldehyde and separated on 1.2% agarose gels (6.475% formaldehyde) with 1× MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) as the running buffer (43). Transfer of the RNA to the nylon membrane was performed by capillary blotting within 18 h.

Inactivation of mrsA by allelic exchange.

A resistance cassette was constructed using the 0.6-kb EcoRV fragment covering the 3′ end of mrsE and 179 bp of the mrsE mrsA intergenic region, the erythromycin resistance gene of pUC19E (23), and a 0.7-kb fragment covering the last three codons of mrsA, the intergenic region, and the 5′ end of mrsR1. This cassette was cloned into the PvuII site of the temperature-sensitive vector pTVO (corresponding to pBD95 (17) but carrying the pE194Ts origin of replication) in S. carnosus TM 300. The resulting plasmid was transformed into the producer strain at 30°C, and clones that had integrated the plasmid were selected by a temperature shift to 42°C. Clones that had performed the double crossover were selected after 48 h of growth in the presence of 25 mg of erythromycin per liter. The integration was checked by PCR employing primers 1 (5′-GGGTATATGCGGTATAAACTTATG-3′) and 2 (5′-GTTTCCCCAATGATTTACCCTC-3′), which amplify the DNA fragment between bp 4818 and 5415 that contains mrsA.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence presented in this report has been submitted to the EMBL database under accession number AJ250862.

RESULTS

Organization of the mersacidin biosynthesis gene cluster.

The cloning strategy of the mersacidin gene cluster is shown in Fig. 1A. A total of 14.2 kb was sequenced comprising the complete mersacidin biosynthesis gene cluster and neighboring regions. The gene cluster covered 12.3 kb and contained 10 putative open reading frames, 3 of which were located on the opposite strand of mrsA, the structural gene of the mersacidin prepeptide (2) (Fig. 1B). All open reading frames were preceded by putative ribosome-binding sites and were initiated by either an ATG or a TTG start codon.

Regulation.

MrsR2 codes for a typical response regulator protein of 240 amino acids and a theoretical molecular mass of 27.6 kDa. It displays the highest sequence similarity to the YvrH protein of B. subtilis (47.9% identity) (26). MrsR2 belongs to the subfamily of OmpR-like response regulators, which also includes the response regulators of the nisin and subtilin gene clusters (21, 47). The conserved Asp residues (positions 12, 13, 14, and 57) of the N terminus and the Lys-Pro-Phe motif (positions 105 to 107) are present. The start codon of the following downstream open reading frame, mrsK2, overlaps the stop codon of mrsR2. MrsK2 is a 477-amino-acid protein (theoretical molecular mass, 55.6 kDa) with the typical features of a sensor kinase which acts as a sensor for environmental signals. The N terminus contains two hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions which are interrupted by a 90-amino-acid hydrophilic stretch that is probably the extracellular sensor domain. MrsK2 shows sequence similarity to the YvrG protein of B. subtilis (30.1% overall identity) (26) and ScnK of the streptococcin A-FF22 gene cluster (24.3% overall identity) (29). The sequence similarity of MrsK2 to the histidine kinases of the nisin and subtilin gene clusters, NisK (12) and SpaK (21), is restricted to the hydrophilic intracellular C-terminal part, which contains the conserved His residue (position 253), where autophosphorylation is thought to take place; the catalytic Asp residue (position 372); and two Gly-rich motifs that are supposed to be the ATP-binding site.

A further open reading frame, mrsR1, encodes a putative response regulator protein of 213 amino acids (24.2 kDa) and is located 95 bp downstream of mrsA. Sequence analysis identified MrsR1 as a response regulator protein, but the sequence similarity of MrsR1 to other response regulator proteins is significantly lower than that of MrsR2. The phosphate acceptor site Asp (position 53) is present; however, the conserved Asp residues in the N terminus of the protein and the Lys residue of the conserved Lys-Pro-Phe motif are missing. Therefore, it is doubtful that MrsR1 can change its conformation in response to phosphorylation, since this effect is mediated by the Lys residue. The C-terminal DNA-binding motif of the OmpR subfamily is present in MrsR1. EpiQ is the single regulatory protein of the epidermin gene cluster, and the C terminus of EpiQ displays homology to PhoB and OmpR, whereas the N terminus of EpiQ does not show homology to response regulator proteins of this family. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that EpiQ binds to one of the inverted repeats upstream of epiA and is indispensable for production of epidermin (35). However, there is no significant similarity between the N termini of MrsR1 and EpiQ. Alignment of MrsR1 with MutR (37), which is yet another single regulatory protein in a lantibiotic gene cluster, did not show any similarity.

Immunity.

At 242 bp upstream of the start codon of mrsR2 in reverse orientation, another open reading frame, mrsF, codes for a protein with similarity to the ATP-binding domain of an ABC transporter and is, in turn, followed by two open reading frames coding for membrane domains: the start codon of mrsG is located 10 bp downstream of the stop codon of mrsF, and the start codon of mrsE follows 16 bp downstream of mrsG. MrsF is a 303-amino-acid (33.8-kDa) protein that shows sequence similarity to the bacitracin transport protein of Bacillus licheniformis (45.1% identity) (36) and several LanF proteins, such as LctF (41.8% identity) (41) and MutF (40.9% identity) (37) from the lacticin and mutacin II gene clusters. All of the residues that are involved in the ATP-binding boxes are conserved in MrsF. The membrane domains MrsE (247 amino acids, 27.4 kDa) and MrsG (244 amino acids, 27.1 kDa) display only a little similarity to their counterparts in other lantibiotic gene clusters, but hydropathy plots predict the formation of six membrane-spanning helices in each protein.

Modifying enzymes.

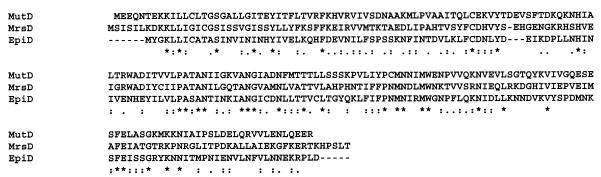

The mersacidin gene cluster contains two modification enzymes. An open reading frame, mrsD, that is located 53 bp downstream of mrsR1 in reverse orientation with respect to mrsA encodes a 194-amino-acid (21.7-kDa) protein with strong sequence similarity (31.4% identity) to MutD from the mutacin III gene cluster (38) and EpiD (25.9% identity), which is an oxidative decarboxylase in the epidermin gene cluster (Fig. 2). EpiD is a 181-amino-acid enzyme which is responsible for the biosynthesis of the C-terminal S-[(Z)-2-aminovinyl]-d-cysteine residue of epidermin (27). Mersacidin contains a C-terminal S-[(Z)-2-aminovinyl]-3-methyl-d-cysteine residue, and MrsD is supposed to catalyze the analogous reaction.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the sequences of MrsD, MutD, and EpiD from the mutacin III and epidermin biosynthesis gene clusters (1, 38). The asterisks indicate identical residues, and residues with high and low degrees of conservation are indicated by colons and dots, respectively.

The open reading frame mrsM starts 212 bp upstream of mrsD on the opposite strand and encodes a putative 1,062-amino-acid (121-kDa) protein that exhibits sequence similarity to several LanM proteins, for example, CylM (26.2% identity) (14) and LctM (22.8% identity) (40). Sequence alignments show 13 conserved regions within the proteins, 6 of which were identified in the N terminus, including the new motives N5 and N6 (Fig. 3). The LanM proteins are supposed to catalyze dehydration and thioether formation of the lantibiotic prepeptides.

FIG. 3.

Conserved motifs of the N termini of the LanM proteins. The asterisks indicate identical residues, and residues with high and low degrees of conservation are indicated by colons and dots, respectively.

Transport function and processing.

At 51 bp downstream of the stop codon of mrsM, there is an open reading frame encoding a putative 730-amino-acid (83.1-kDa) protein that shows sequence similarity to the dual-function transporters found in the gene clusters of GG-type lantibiotics, for example, CylB (29.0% identity [14]). These proteins are involved in export of the modified lantibiotic from the cell, as well as processing of the leader peptide (18). The N-terminal 130 amino acids of MrsT display sequence similarity to the cysteine protease domains of these proteins, and the conserved Cys residue that was shown to be active in the LagD transporter (18) is also present in MrsT. The C-terminal 600 amino acids show similarity to LanT transporters, and a hydropathy plot predicts six hydrophobic membrane-spanning domains.

Localization of the gene cluster.

At 292 bp downstream of mrsT, the stop codon of another open reading frame was found. A search of the B. subtilis data bank revealed that the protein encoded by this open reading frame shows nearly 100% similarity to ioIJ of the myoinositol dehydrogenase gene cluster. In B. subtilis 168, this gene lies adjacent to yxdJ and yxdK, which encode a two-component regulatory system with an unknown function (52). In Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728, open reading frames with sequences nearly identical to those of yxdJ and yxdK were found 149 bp downstream of mrsK2, indicating that the mersacidin gene cluster is inserted between ioIJ and yxdJ at 348° on the chromosome of the producer strain. The nucleotide sequence that frames the mersacidin gene cluster in Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 differs from the noncoding region of approximately 100 bp located between ioIJ and yxdJ in B. subtilis 168 and contains two different indirect repeats. The overall GC content of the gene cluster, 34.2%, is lower than that of the chromosome of B. subtilis 168, with 43.5% GC (26).

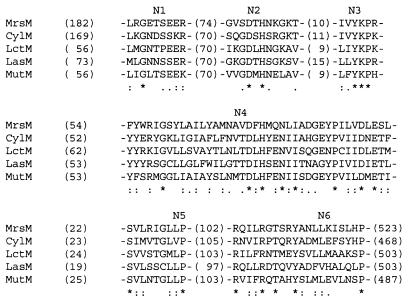

Transcription of mrsA.

At 283 bp downstream of the stop codon of mrsE, the structural gene for mersacidin, mrsA, is located, which encodes the 68-amino-acid prepeptide of mersacidin (2). Only one 270-bp transcript corresponding to mrsA, which appeared between 8 and 16 h of cultivation and which was still present after 32 h, was detected in Northern blots (Fig. 4). Eight base pairs downstream of mrsA, a stem-loop structure (ΔG, −85.7 kJ/mol) is located that could act as a rho-independent transcription terminator. In order to investigate whether mersacidin is the only antibacterial substance excreted by the producer strain, mrsA was exchanged for an erythromycin resistance cassette by double homologous recombination in Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 Rec1. The integration was confirmed by PCR, which yielded a 1,410-bp product; the 597-bp product of the wild-type strain was not detected. The strain did not hybridize with a probe against mrsA in Southern and Northern blots, and after 64 h of cultivation in production medium, no mersacidin could be detected in the high-pressure liquid chromatography fractions of the supernatant by assay of the antibacterial activity. Producer self-protection against mersacidin was not affected in this clone. In spite of the mrsA knockout, we detected some antibacterial activity in the supernatant, indicating that the producer strain is indeed able to synthesize several antibiotic substances (Fig. 5). One of these compounds could be a surfactin-like antibiotic, since we also cloned and sequenced a region with high similarity to the Srf1 subunit of the surfactin synthetase (data not shown).

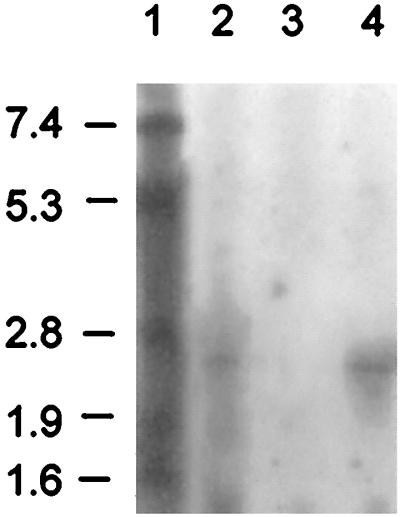

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of the time course of mrsA transcription. Lanes: 1, size standard (the values to the left are sizes in kilobases); 2, 8 h of cultivation; 3, 16 h of cultivation; 4, 24 h of cultivation; 5, 32 h of cultivation.

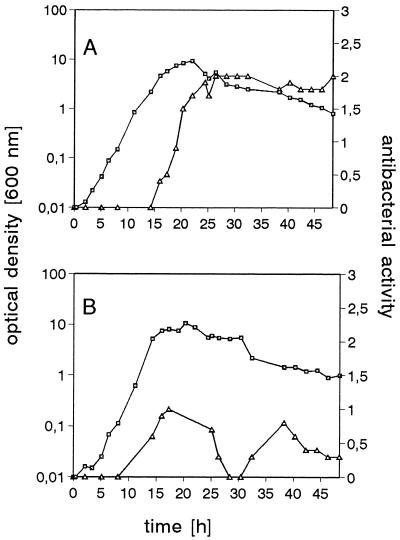

FIG. 5.

Time course of production of antibacterial activity (diameter of inhibition zone against M. luteus, in centimeters (Δ) and growth (□) of the wild-type producer strain (A) and Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728 Rec1 (mrsA::Erm) (B).

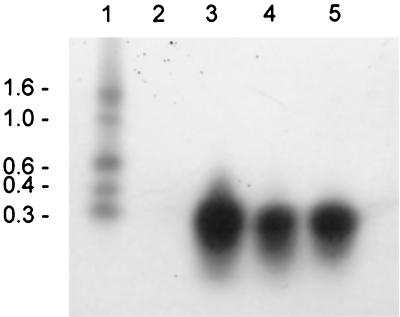

Transcription of putative immunity genes.

Transcription analyses of mrsFGE in the wild-type producer strain employing probes specific for mrsF, mrsG, and mrsE showed that all three genes are transcribed from an operon and yield a 2.5- to 2.6-kb RNA (Fig. 6), which corresponds well to the theoretical length of the mrsFGE operon (2,470 bp). mrsFGE was then cloned into the E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector pCU1 (1), giving pCC2 (Fig. 1C), and transformed into S. carnosus TM 300 and B. subtilis W23. Transcription analysis showed that the genes were not transcribed and no increase in resistance against mersacidin could be demonstrated in either strain. Attempts to clone a plasmid harboring mrsK2R2 mrsFGE failed because this construct was not stably maintained in either E. coli or S. carnosus TM300. A clone containing mrsK2R2 mrsFGΔE (pKRFGE2, Fig. 1C) was easily obtained, but the plasmid did not confer self-protection, since mrsE is disrupted. Nevertheless, transcription analysis showed that in the presence of the putative regulatory genes, mrsFGΔE was transcribed in B. subtilis W23 (Fig. 6). This transcript is a little shorter than that detected in the wild-type strain and is terminated within the vector sequence. These results demonstrate that MrsR2 and MrsK2 play a role in the regulation of transcription of the putative immunity genes.

FIG. 6.

Northern blot analysis of the transcription of mrsFGE employing an mrsF probe. Lanes: 1, size standard (the values to the left are sizes in kilobases); 2, wild-type producer Bacillus sp. strain HIL Y-85,54728; 3, B. subtilis W23 harboring pCC2; 4, B. subtilis W23 harboring pKRFGE2.

DISCUSSION

The mersacidin biosynthetic gene cluster is inserted into the chromosome of the producer strain close to the origin of replication, at 348°, and forms a distinct region that differs significantly in GC content. AT-rich islands in the genome of B. subtilis 168 are often formed by prophages, remnants of prophages or transposons (26). However, sequencing of the ends of the mersacidin gene cluster did not give any indication of the presence of a prophage or association with a transposon, although transposase or integrase genes have often been found in the vicinity of lantibiotic gene clusters, e.g., in the nisin (39) and lacticin 481 (41) gene clusters. The gene cluster of mersacidin was the first gene cluster of a type B lantibiotic to be sequenced. Compared to type A lantibiotic gene clusters, it shows the characteristic features of a gene cluster belonging to a GG-type leader peptide lantibiotic, containing a LanM modification enzyme and a chimeric LanT transporter with an associated protease domain (42). These results were unexpected because, at first sight, the leader peptide of mersacidin seems to differ from the GG-type leader peptides (2). It does not display sequence similarity upon alignment with a typical GG-type leader peptide, and there is no GG, GA, or GS double-glycine sequence in positions −2 and −1 of the leader peptide, which is the typical cleavage site of the protease domain of LanT. However, upon closer inspection, these apparent inconsistencies can be at least partly reconciled. The mersacidin prepeptide contains Ala residues at positions −1 and −2. Recently, another lantibiotic, staphylococcin C55β, that displays an AA cleavage site in combination with a chimeric LanT protein has been described (30). On the other hand, a GA sequence is present in the leader peptide of mersacidin at positions −8 and −7; thus, double processing, as reported for the cytolysin peptides by CylB and CylA, might be possible for mersacidin (4). In contrast to the cytolysin gene cluster, no dedicated serine protease is encoded in the mersacidin biosynthesis gene cluster. However, Bacillus is a prominent producer of a number of extracellular proteases and the subtilin gene cluster in B. subtilis 6633 does not contain a protease gene as well, indicating that subtilin and mersacidin may be processed by host enzymes. In Fig. 7, we have aligned a part of the leader peptide of mersacidin with all of the lantibiotic GG-type leader peptides described so far, the staphylococcin C55α, lacticin 3147 A1, and lactocin S leaders, assuming the GA at positions −8 and −7 to be the cleavage site of MrsT. The GG-type leader peptides show a conserved motif that starts with a hydrophobic residue at position −15: F/L/I-E(Q/D/N)-E-V(L)-S(T/K). The same motif is present in staphylococcin C55α and lacticin 3147 A1 leaders starting at position −16 and even displayed by lactocin S (LDELS at positions −24 to −20). With the exception of the Ser at position −14 and the Lys at position −5, the FSELK motif of the mersacidin prepeptide and the following sequence of amino acid residues show similarity to the listed leader peptides, although there is no marked similarity of the mrsA leader peptide to one specific peptide of the GG type. In conclusion, the mersacidin leader peptide carries fewer charged amino acids and is longer than GG-type leader peptides (2); nevertheless, some similarity to the conserved motifs of the GG-type leader peptides can be discerned if the GA at positions −8 and −7 is assumed to be the processing site. It has been demonstrated for nisin that the leader peptide is involved in the modification reactions or in targeting of the peptide to the modification and/or export complex. Perhaps the conserved motif of the above leaders fulfills a similar function by targeting the prepeptides to the LanM-LanT modification-and-export machine (48). On the other hand, the conserved sequence and the conserved biosynthesis machinery may simply indicate an evolutionary interrelationship between mersacidin and the GG-type leader peptide subgroup of type A lantibiotics. However, if such an interrelationship exists, the classification into type A and B lantibiotics, that was introduced on the basis of structural data (before the lantibiotics of the GG-type leader peptide had been described) and mode-of-action data, will have to be reconsidered and the sequence of biosynthetic gene clusters of other type B lantibiotics, e.g., cinnamycin, would be most interesting. In addition, not only the architecture of the gene cluster but also the modes of action of some type A lantibiotics and mersacidin are not as different as assumed previously. This fact is demonstrated by the putative immunity genes found in the mersacidin gene cluster and recent results obtained with epidermin and nisin. Unlike type A lantibiotics, mersacidin does not form pores but inhibits transglycosylation by binding to the ultimate cell wall precursor lipid II [undecaprenyl-pyrophosphoryl-MurNAc(pentapeptide)-GlcNAc] (5, 7). In spite of this, a LanEFG transporter is present in the gene cluster, which is also found in the gene clusters of, e.g., nisin and epidermin. The immunity transporter EpiFEG prevents binding of epidermin to the membrane, and consequently, fewer pores are formed (31). However, it is possible that LanEFG specifically prevents lantibiotic binding to or interaction with lipid II. Mersacidin acts by binding to lipid II, and recent studies have shown that the presence of lipid II facilitates pore formation by epidermin and nisin, which utilize the cell wall precursor as a docking molecule in the bacterial membrane (6). The producer strain of the antibiotic bacitracin, which acts by binding to undecaprenylpyrophosphate and prevents recyclization of the carrier to undecaprenylphosphate, is protected by an ABC transporter with sequence similarity to MrsF (36).

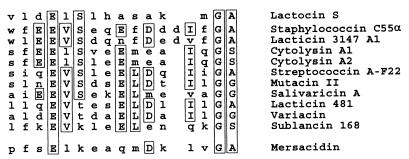

FIG. 7.

Alignment of the C-terminal part of the leader sequences of lantibiotic prepeptides harboring a GG-type cleavage site with an internal fragment of the mersacidin prepeptide. Amino acid residues that are not conserved are in lowercase, whereas residues that are conserved in five or more leader peptides are in uppercase and boxed (11, 30, 33, 40, 42, 50).

The exchange of mrsA for an erythromycin resistance cassette resulted in the loss of mersacidin production, but antibacterial activity was still excreted, indicating that mersacidin is only one of the antibacterial substances that are produced by the strain. This is not unusual for Bacillus strains; wild-type Bacillus isolates produce several antibiotic substances, such as surfactin, fengycin, difficidin, and sublancin, and sequencing of the B. subtilis 168 genome has shown that nearly 4% of the chromosome is devoted to coding for large multienzymes involved in antibiotic biosynthesis (26). The production of mersacidin was growth phase dependent. Transcription of mrsA started at the onset of early stationary phase, between 8 and 16 h of cultivation, corresponding well to the detection of mersacidin in the supernatant after 14 to 15 h. This correlation does not apply to all lantibiotics; mutacin II is expressed independently of the growth phase but produced only at the end of the exponential phase (37). Only a short, monocistronic 0.27-kb transcript representing mrsA was detected by Northern blotting. The stem-loop structure that is located downstream of mrsA might function as a transcriptional terminator or barrier to exonucleolytic degradation. In many lantibiotic gene clusters, similar structures are located downstream of the prelantibiotic genes and serve to limit the expression of the biosynthetic enzymes (42).

The mersacidin gene cluster is the first lantibiotic gene cluster to contain two open reading frames that display homology to regulatory proteins. A similar combination involving one histidine kinase and two response regulator proteins was identified in the bacteriocin gene cluster of Lactobacillus plantarum C11 (10). Three lantibiotic gene clusters, those of nisin, subtilin, and streptococcin A-FF22, are regulated by a two-component regulatory system consisting of a sensor kinase and a response regulator (12, 21, 29). For nisin, the signal that activates transcription of the gene cluster has been elucidated; here, the lantibiotic itself regulates its biosynthesis and immunity genes (24). Mersacidin is apparently not the signaling molecule for transcription of the putative immunity genes; in B. subtilis W23, transcription of mrsFGE was initiated only in the presence of the two-component regulatory system formed by MrsR2 and MrsK2. B. subtilis W23 does not produce mersacidin, since it does not harbor the mersacidin biosynthetic gene cluster, and the lantibiotic had not been added to the culture in this particular experiment. The nature of the signal molecule, the regulation of mersacidin biosynthesis, and the interplay of MrsR1 with MrsR2 and MrsK2 will be the subjects of future research, and the understanding of these processes will be particularly important in the area of mersacidin biotechnology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bi 504/1-2 and Bi 504/1-3) and through the BONFOR program of the Medizinische Einrichtungen, University of Bonn.

We gratefully acknowledge C. Szekat for expert technical assistance, I. Wiedemann for contributions to the growth curves, and T. Schmitter for contributions to the Northern blots and thank Aventis Pharma AG, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, for making the mersacidin producer strain available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin J, Rosenstein R, Wieland B, Schneider U, Schnell N, Engelke G, Entian K-D, Götz F. Genetic analysis of epidermin biosynthetic genes and epidermin-negative mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:1149–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierbaum G, Brötz H, Koller K-P, Sahl H-G. Cloning, sequencing and production of the lantibiotic mersacidin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisschop A, Konings W N. Reconstitution of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase activity with menadione in membrane vesicles from the menaquinone-deficient Bacillus subtilis AroD. Eur J Biochem. 1976;67:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth M C, Bogie C P, Sahl H-G, Siezen R J, Hatter K L, Gilmore M S. Structural analysis and proteolytic activation of Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin, a novel lantibiotic. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1175–1184. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.831449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brötz H, Bierbaum G, Reynolds P E, Sahl H-G. The lantibiotic mersacidin inhibits peptidoglycan biosynthesis at the level of transglycosylation. Eur J Biochem. 1997;246:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brötz H, Josten M, Wiedemann I, Schneider U, Götz F, Bierbaum G, Sahl H-G. Role of lipid-bound peptidoglycan precursors in the formation of pores by nisin, epidermin and other lantibiotics. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:317–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brötz H, Bierbaum G, Leopold K, Reynolds P E, Sahl H-G. The lantibiotic mersacidin inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by targeting lipid II. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:154–160. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee S, Chatterjee D K, Jani R H, Blumbach J, Ganguli B N, Klesel N, Limbert M, Seibert G. Mersacidin, a new antibiotic from Bacillus: in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity. J Antibiot. 1992;45:839–845. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee S, Chatterjee S, Lad S J, Phansalkar M S, Rupp R H, Ganguli B N, Fehlhaber H-W, Kogler H. Mersacidin, a new antibiotic from Bacillus: fermentation, isolation, purification and chemical characterization. J Antibiot. 1992;45:832–838. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Nes I F. Characterization of the locus responsible for the bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4472–4483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4472-4483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty B A, Hill C, Weidman J F, Richardson D R, Venter J C, Ross R P. Sequence and analysis of the 60 kb conjugative, bacteriocin-producing plasmid pMRC01 from Lactococcus lactis DPC3147. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1029–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelke G, Gutowski-Eckel Z, Kiesau P, Siegers K, Hammelmann M, Entian K-D. Regulation of nisin biosynthesis and immunity in Lactococcus lactis 6F3. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:814–825. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.814-825.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feliciello I, Chinali G. A modified alkaline lysis method for the preparation of highly purified plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:394–401. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilmore M S, Segarra R A, Booth M C, Bogie C P, Hall L R, Clewell D B. Genetic structure of the Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1-encoded cytolytic toxin system and its relationship to lantibiotic determinants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7335–7344. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7335-7344.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Götz F, Schumacher B. Improvements of protoplast transformation in Staphylococcus carnosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;40:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosch J C, Wollweber K L. Transformation of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens protoplasts by plasmid DNA. In: Streips U N, Goodgal H S, Guild W R, Wilson G A, editors. Genetic exchange. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1982. pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gryczan T J, Hahn J, Contente S, Dubnau D. Replication and incompatibility properties of plasmid pE194 in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:722–735. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.2.722-735.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Håvarstein L S, Diep D B, Nes I F. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack R W, Bierbaum G, Sahl H-G. Lantibiotics and related peptides. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung G. Lantibiotics—ribosomally synthesized biologically active polypeptides containing sulfide bridges and α,β-didehydroamino acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1991;30:1051–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein C, Kaletta C, Entian K-D. Biosynthesis of the lantibiotic subtilin is regulated by a histidine kinase/response regulator system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:296–303. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.296-303.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraft R, Tardiff J, Kauter K S, Leinwand L A. Using miniprep plasmid DNA for sequencing doublestranded templates with Sequenase. BioTechniques. 1988;6:544–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuipers O P, Beerthuyzen M M, Siezen R J, de Vos W M. Characterization of the nisin gene cluster nisABTCIPR of Lactococcus lactis: requirement of expression of the nisA and nisI genes for development of immunity. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuipers O P, Beerthuyzen M M, de Ruyter P G G A, Luesink E J, de Vos W M. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27299–27304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuipers O P, Bierbaum G, Ottenwälder B, Dodd H M, Horn N, Metzger J W, Kupke T, Gnau V, Bongers R, van den Bogaard P, Kosters H, Rollema H S, de Vos W M, Siezen R J, Jung G, Götz F, Sahl H-G, Gasson M J. Protein engineering of lantibiotics. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00399421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, Azevedo V, Bertero M G, Bessieres P, Bolotin A, Borchert S, Borriss R, Boursier L, Brans A, Braun M, Brignell S C, Bron S, Brouillet S, Bruschi C V, Caldwell B, Capuano V, Carter N M, Choi S K, Codani J J, Connerton I F, Danchin A, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kupke T, Götz F. Post-translational modifications of lantibiotics. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:139–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00399419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Hansen J N. Enhancement of the chemical and antimicrobial properties of subtilin by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25078–25085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLaughlin R E, Ferretti J J, Hynes W L. Nucleotide sequence of the streptococcin A-FF22 lantibiotic regulon: model for production of the lantibiotic SA-FF22 by strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;175:171–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navaratna M A D B, Sahl H G, Tagg J R. Identification of genes encoding two-component lantibiotic production in Staphylococcus aureus C55 and other phage group II S. aureus strains and demonstration of an association with the exfoliative toxin B gene. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4268–4271. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4268-4271.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otto M, Peschel A, Götz F. Producer self-protection against the lantibiotic epidermin by the ABC transporter EpiFEG of Staphylococcus epidermidis Tü3298. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;166:203–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pag U, Heidrich C, Bierbaum G, Sahl H-G. Molecular analysis of expression of the lantibiotic Pep5 immunity phenotype. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:591–598. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.591-598.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paik S H, Chakicherla A, Hansen J N. Identification and characterization of the structural and transporter genes for, and the chemical and biological properties of, sublancin 168, a novel lantibiotic produced by Bacillus subtilis 168. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23134–23142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peschel A, Augustin J, Kupke T, Stefanovic S, Götz F. Regulation of epidermin biosynthesis genes by EpiQ. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podlesek Z, Herzog B, Comino A. Amplification of bacitracin transporter genes in the bacitracin producing Bacillus licheniformis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi F, Chen P, Caufield P W. Functional analyses of the promoters in the lantibiotic mutacin II biosynthetic locus in Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:652–658. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.652-658.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi F, Chen P, Caufield P W. Purification of mutacin III from group III Streptococcus mutans UA787 and genetic analyses of mutacin III biosynthesis genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3880–3887. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.3880-3887.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rauch P J G, de Vos W M. Identification and characterization of genes involved in excision of the Lactococcus lactis conjugative transposon Tn5276. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2165–2171. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2165-2171.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rincé A, Dufour A, Le Pogam S, Thuault D, Bourgeois C M, Le Pennec J P. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of genes involved in production of lactococcin DR, a bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1652–1657. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1652-1657.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rincé A, Dufour A, Uguen P, Le Pennec J P, Haras D. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4252–4260. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4252-4260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahl H-G, Bierbaum G. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from Gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:41–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schleifer K H, Fischer U. Description of a new species of the genus Staphylococcus: Staphylococcus carnosus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1982;32:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnell N, Entian K-D, Schneider U, Götz F, Zähner H, Kellner R, Jung G. Prepeptide sequence of epidermin, a ribosomally synthesized antibiotic with four sulphide-rings. Nature. 1988;333:276–278. doi: 10.1038/333276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Meer J R, Polman J, Beerthuyzen M M, Siezen R J, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Characterization of the Lactococcus lactis nisin A operon genes nisP, encoding a subtilisin-like serine protease involved in precursor processing, and nisR, encoding a regulatory protein involved in nisin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2578–2588. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2578-2588.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Meer J R, Rollema H S, Siezen R J, Beerthuyzen M M, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Influence of amino acid substitutions in the nisin leader peptide on biosynthesis and secretion of nisin by Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3555–3562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodruff W A, Novak J, Caufield P W. Sequence analysis of mutM and mutA genes involved in the biosynthesis of the lantibiotic mutacin II in Streptococcus mutans. Gene. 1998;206:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00578-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida K, Sano H, Miwa Y, Ogasawara N, Fujita Y. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of a 15 kb region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the iol operon. Microbiology. 1994;140:2289–2298. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]