Abstract

The construction of a delivery and clearing system for the generation of food-grade recombinant lactic acid bacterium strains, based on the use of an integrase (Int) and a resolvo-invertase (β-recombinase) and their respective target sites (attP-attB and six, respectively) is reported. The delivery system contains a heterologous replication origin and antibiotic resistance markers surrounded by two directly oriented six sites, a multiple cloning site where passenger DNA could be inserted (e.g., the cI gene of bacteriophage A2), the int gene, and the attP site of phage A2. The clearing system provides a plasmid-borne gene encoding β-recombinase. The nonreplicative vector-borne delivery system was transformed into Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 and, by site-specific recombination, integrated as a single copy in an orientation- and Int-dependent manner into the attB site present in the genome of the host strain. The transfer of the clearing system into this strain, with the subsequent expression of the β-recombinase, led to site-specific DNA resolution of the non-food-grade DNA. These methods were validated by the construction of a stable food-grade L. casei ATCC 393-derived strain completely immune to phage A2 infection during milk fermentation.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) play an important role as starters of fermented food products. When present in food products, LAB function as a biopreservative, preventing spoilage by pathogenic microorganisms through acidification, competition for essential nutrients, and/or production of inhibitory compounds (33). Some strains of LAB are also thought to be beneficial for consumers due to their claimed specific health-promoting, probiotic characteristics (26, 30).

Most of the relevant properties of LAB (e.g., lactose fermentation, citrate transport, protease production, phage resistance mechanisms, etc.) are plasmid encoded. In fact, plasmid instability and phage infection are the major sources of disruption in the production of fermented products by LAB (7, 14, 23). The development of a wide variety of versatile cloning vehicles based on endogenous replicons and selection markers allowed the improvement of many properties of LAB and ameliorated these problems (1, 9, 20, 24). However, one way to circumvent the potential instability of plasmid-based cloning vehicles is the construction of food-grade vectors that could allow the direct insertion of DNA fragments (e.g., by site-specific recombination) into the genome of LAB.

Site-specific recombinases can be clustered into two major families. The Int family comprises those enzymes that catalyze recombination between sites located either in the same (resolution and inversion) or in separate DNA molecules (integration) (22). Vector systems based on the site-specific integration apparatus of temperate bacteriophages of Lactococcus (6, 15, 19) or Lactobacillus (3, 10, 27) spp. have been constructed. These systems allowed targeted insertion at the attB site on the host genome. The integrase encoded by gene int of Lactobacillus casei phage A2 targets insertion into a 19-bp attB site at a tRNALeu gene (3). This enzyme is also able to catalyze recombination between the attP and a 13- or 11-bp attB-like site present in the genome of Lactococcus lactis (at an intergenic region) and Escherichia coli (at the rrnD operon) cells, respectively (3). These cloning systems, however, cannot be used in commercial fermentation without the selective elimination of unwanted sequences because starters are usually consumed with the product.

The second family of recombinases includes those enzymes that catalyze recombination only when the sites are located in the same DNA molecule (resolution and/or inversion); they are collectively termed resolvases/invertases (12). β-Recombinase (29), which belongs to this family, catalyzes in vitro intramolecular deletions and inversions of DNA sequences located between two 90-bp target sites (six site) present in a supercoiled substrate, provided that a chromatin-associated protein is present in the reaction mixture (2, 5). β-Recombinase, in the presence of Hbsu or HMG1 protein, promotes in vivo deletions of the intervening DNA, independently of the insertion position of the two directly oriented six sites on a bacterial or mammalian cell genome (2, 8). Hence, the β-mediated recombination could be used to remove the unwanted sequences left by the integration events directed into the genome of LAB.

In this study we describe the construction of a delivery and depuration system. We show that the Int protein catalyzes in vivo site-specific integration, as a single copy, into the genome of LAB and that the β-recombinase catalyzes the deletion of the unwanted sequences. The system was validated by the cloning of the phage A2 repressor gene (cI) (11, 16), which provided superinfection immunity. In the present study, a food-grade L. casei strain which has the phage A2 cI gene stably integrated into the genome was shown to be completely resistant to phage infection and able to ferment milk even in the presence of phage A2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, bacteriophage, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and the bacteriophage used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. casei strains were cultivated in MRS medium (Oxoid), without aeration, at 30°C. Standard media and growth condition were used for E. coli (31). When appropriate, the medium was supplemented with 5 μg of erythromycin (Em) or chloramphenicol (Cm), 100 μg of ampicillin (Ap), or 0.4 μg of novobiocin (Nv) per ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, phage, plasmids, and primers used in the present study

| Material | Relevant features | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| E. coli DH10B | Used for general cloning | GIBCO-BRL |

| L. casei ATCC 393 | Plasmid-free | ATCCa |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19E | pUC19 derivative, Emr | 18 |

| pBT338 | pUC18::six | 29 |

| pLP825 | p8014-2, ori of pBR322, Cmr | 25 |

| pBT241 | pT712-borne β gene | 29 |

| pEM40 | pUC19E-borne A2 int-attP | 3 |

| pEM40::cI | pUC19E-borne A2 cI, int-attP | 3 |

| pEM74 | pUC19E-borne six, A2 int-attP | This work |

| pEM76 | pUC19E-borne six1 A2 int-attP six2 | This work |

| pEM76::cI | pUC19E-borne six1 A2 cI int-attP six2 | This work |

| pEM68 | pLP825-borne β gene | This work |

| Phage A2 | Temperate phage isolated from milk whey | 13 |

| Primers | ||

| att1 | 5′-AGCAGGACGAGAAAGCAATGAATGT-3′ | 3 |

| att7 | 5′-GCCGGTGTGGCGGAATTGGCAG-3′ | 3 |

| b1 | 5′-TCTCTGATAGACAGTATAGAGGAG-3′ | 3 |

| int2 | 5′-CTGGGATCCCCAAGGCTTACTTT-3′ | This work |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Phage A2 was propagated on L. casei ATCC 393, and phage titers were determined as previously described (13). Phage resistance phenotype was assayed at 30°C for 24 h in 11% reconstituted skim milk (4). After steaming (100°C, 30 min), the reconstituted skim milk was supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 0.25% yeast extract.

DNA manipulation procedures.

Total DNA was extracted using 2× Kirby lytic mix according to Hopwood et al. (15). Plasmid DNA was prepared from E. coli by the alkaline lysis method (31). Isolation of plasmid DNA from L. casei was performed as described previously (32). Phage A2 DNA was extracted and purified as described by Suárez and Chater (34). The DNA modification enzymes were from commercial sources, and they were used as recommended by the suppliers.

Electrotransformation of E. coli was achieved in a Bio-Rad pulser apparatus using protocols provided by the supplier; L. casei was electroporated as described by Wei et al. (36), yielding 106 to 107 transformants/μg of DNA. The site-specific integration of the vectors into the genome of L. casei was analyzed by PCR amplification using the previously described oligonucleotide primers att1 and att7 (3) (Table 1). The site-specific resolution was confirmed by PCR analysis using the primers b1 and int2 (Table 1) and the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The hybridization was performed using the nonradioactive DNA Labelling and Detection Kit of Roche Molecular Biochemicals according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Plasmid constructions.

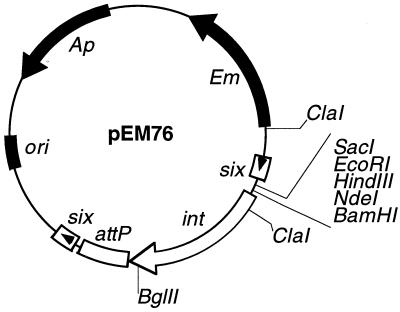

Plasmid pEM76 (see Fig. 1) was constructed in two steps. The 450-bp XbaI blunt-ended SphI fragment, containing the six (EMBL database, accession number X64695) isolated from pBT338, was joined to a pEM40 derivative containing the E. coli replication origin (ori), the β-lactamase (Ap), and the erythromycin (Em) resistance genes, the int gene, and the attP site to generate pEM74. The 450-bp BamHI-BglII fragment containing a second copy of the six site was inserted into the BamHI site of pEM74, resulting in pEM76. pEM76 contains two directly oriented six sites separated by a 1.6-kb fragment that includes the integration cassette of bacteriophage A2 (Fig. 1). The 0.8-kb EcoRI DNA segment containing the cI gene from phage A2 was joined to EcoRI-linearized pEM76 to generate pEM76::cI (see Fig. 2A).

FIG. 1.

Physical map of plasmid pEM76. The relevant features are indicated, including the E. coli replication origin (ori); the β-lactamase and erythromycin gene conferring resistance to ampicillin (Ap) and erythromycin (Em), respectively; the integration region of bacteriophage A2 (int-attP); and two directly oriented copies of the β-recombinase binding site (six). Arrowheads denote the polarity of the insert. Relevant restriction sites are denoted.

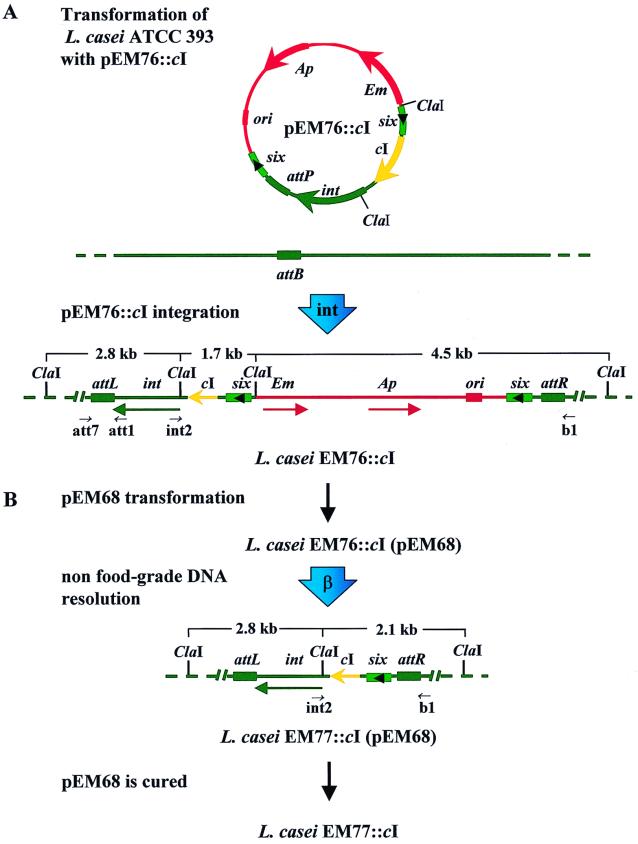

FIG. 2.

Mechanism of integration and deletion of pEM76::cI into the genome of L. casei ATCC 393 to render L. casei EM77::cI. (A) pEM76::cI is introduced by transformation into L. casei ATCC 393, and the Int protein catalyzes site-specific integration between attP and attB to yield L. casei EM76::cI. (B) pEM68-borne β gene product, with the help of the L. casei chromatin-associated protein, catalyzes DNA resolution between two directly oriented six genes to generate L. casei EM77::cI(pEM68). In a second step, pEM68 is cured to render plasmid-free L. casei EM77::cI. Food-grade DNA is shown in green, non-food-grade DNA is shown in red, and the gene to be stabilized (cI in this case) is shown in yellow.

Plasmid pEM68 was generated by cloning a 1.4-kb AccI DNA fragment containing the β-recombinase gene (EMBL database, accession number X64695) from pBT241 (29) into SphI-SalI-digested pLP825 upon blunting of the DNA ends.

RESULTS

Construction of the delivery system.

The pEM76-based delivery system, which does not replicate in gram-positive bacteria, is composed of versatile cassettes and was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. It contains an E. coli replication origin and the β-lactamase and erythromycin resistance genes bracketed by two directly oriented six sites and the int gene and the attP site (Fig. 1). To validate the use of the delivery system we have cloned a DNA segment that contains the cI gene, which encodes the repressor of phage A2, into pEM76 to generate pEM76::cI (Fig. 2A).

The depuration system contains a DNA fragment, coding for the β-recombinase, joined to the shuttle E. coli-LAB vector pLP825 (25) to generate pEM68. Since an accessory factor needed for β-mediated recombination is provided by eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells (28, 29), we expected that an L. casei-encoded chromatin-associated protein was present and would assist β-mediated site-specific recombination. This is consistent with the fact that the β-recombinase catalyzes in vivo deletions in mouse, E. coli, and B. subtilis cells (2, 8).

Construction of a food-grade strain expressing the phage A2 cI repressor.

The nonreplicative pEM76::cI vector (Fig. 2) and the pEM76 control (Fig. 1) were transformed into L. casei ATCC 393 with selection for Em resistance (Emr). L. casei Emr colonies, which are only formed if the nonreplicative vector has been integrated either at the 19-bp attB site (Fig. 2A) or ectopically at any other site, are observed at a relative high frequency. We confirmed by PCR, Southern blot, and nucleotide sequence analyses that integration occurs as a single copy in an orientation-dependent manner only at the attB site.

One colony from each of the integrated materials, L. casei EM76::cI and EM76, respectively, was selected for further work. The pEM68-borne β gene was introduced into L. casei EM76::cI and EM76 by transformation and Cmr colonies were selected (Fig. 2B). To allow β-mediated recombination between the two six sites, the L. casei EM76::cI(pEM68) and EM76(pEM68) strains were grown overnight in liquid medium containing Cm but lacking Em. Colonies which were Cmr and Ems were obtained at a high frequency (approaching 60%) (see Fig. 2B), whereas spontaneous deletions of the Emr marker were not observed in the L. casei EM76::cI and EM76 strains (data not shown). This implies that the β-recombinase markedly enhanced the deletion of the unwanted DNA (ori-Ap-Em-six). The Cmr Ems strains, which were termed L. casei EM77::cI(pEM68) and EM77(pEM68), respectively, were then grown overnight in the presence of Nv and in the absence of Cm in order to cure the strains of pEM68. More than 10% of the culture cells were plasmid free. L. casei EM77::cI and EM77 colonies cured from plasmid pEM68 were selected for further analysis.

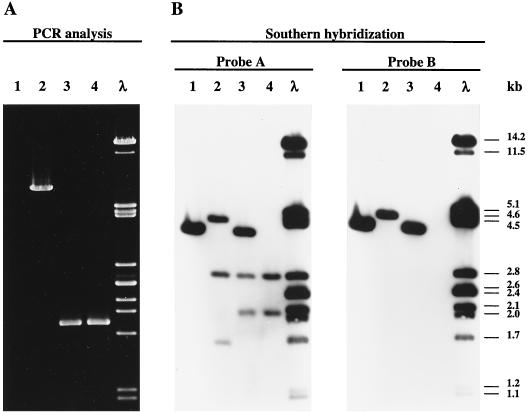

Each step was confirmed by PCR analysis and by Southern blotting. PCRs using primers b1 and int2 (Fig. 2A) and total DNAs extracted from relevant strains was performed. As revealed in Fig. 3A, no DNA amplification was observed using control DNA extracted from L. casei ATCC 393(pEM68) (Fig. 3A, lane 1) and, as expected, a 6-kb DNA fragment was obtained when the L. casei EM76::cI DNA was used as a template (Fig. 3A, lane 2). After transformation of L. casei EM76::cI and EM76 with pEM68, expression of the β gene, and subsequent deletion of the DNA encompassing the two six sites, the amplicon obtained using primers b1 and int2 and the L. casei EM77::cI and EM77 template DNAs (Fig. 2B) was ∼2 kb (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4). It is likely, therefore, that the non-food-grade DNA was deleted.

FIG. 3.

The food-grade L. casei EM77 and L. casei EM77::cI strains. The L. casei ATCC 393(pEM68) control and L. casei EM76::cI strains were analyzed by PCR and Southern hybridization analyses. (A) PCR analysis using total DNA and the int2 and b1 primers. (B) Southern hybridization conducted with ClaI digests of total DNA extracted from the same strains (probe A, plasmid pEM76; probe B, plasmid pUC19E). Lanes: 1, L. casei ATCC 393(pEM68); 2, L. casei EM76::cI; 3, L. casei EM77::cI(pEM68); 4, plasmid-free L. casei EM77::cI; 5, λ DNA digested with PstI. Molecular sizes are shown on the right.

Total DNA extracted from the same strains was digested with ClaI and probed with pUC19E (Fig. 3B, probe B) or its derivative pEM76 (Fig. 3B, probe A). The former is the E. coli vector used for the construction of pEM76. DNA corresponding to L. casei EM76::cI shows three hybridization bands of ca. 4.5, 2.8, and 1.6 kb (the pEM76::cI vector has two ClaI recognition sites; Fig. 2A and 3B [probe A], lane 2). DNAs corresponding to L. casei EM77::cI(pEM68) and EM77::cI, the ∼4.5- and ∼1.6-kb DNA segments, are absent, but a novel DNA band of ∼2.1 kb was detected (Fig. 3B, probe A, lanes 3 and 4). As revealed in Fig. 3, probe A, lanes 1 [L. casei ATCC 393(pEM68)] and 3 [EM77::cI(pEM68)], the 4.0-kb DNA band, which corresponds to plasmid pEM68, was missing when DNA from EM77::cI was analyzed (Fig. 3, probe A, lane 4). A second Southern blot analysis was performed to estimate whether heterologous DNA was completely eliminated from the strain L. casei EM76::cI. As revealed in Fig. 3B, probe B highlights the ∼4.5-kb DNA fragment from L. casei EM76::cI (lane 2), which contains the integrated pEM76 vector DNA and the ∼4.0-kb pEM68 DNA [L. casei ATCC 393(pEM68), lane 1; L. casei EM77::cI(pEM68), lane 3] but fails to hybridize with the plasmid-free L. casei EM77::cI integrated DNA (lane 4).

Food-grade L. casei EM77::cI strain induces stable phage resistance during milk fermentation.

Previously, it has been demonstrated that L. casei EM40::cI, which contains a single copy of cI inserted into the genome, is able to ferment milk in the presence of the phage (4). However, such a strain cannot be used as a starter in the production of fermented products due to the presence of non-food-grade DNA in the host chromosome. We show here that the food-grade L. casei EM77::cI strain is totally resistant to phage A2 infection under laboratory and milk fermentation conditions. First, no single A2 plaque on L. casei EM77::cI was produced by a phage suspension with a titer of 1010 PFU/ml, as judged by the plating efficiency of the L. casei ATCC 393 control strain. Second, L. casei EM77::cI, used as unique starter, is able to ferment milk in the presence of phage A2. Third, phage-free milk was inoculated, at 24-h intervals, with the whey of previous fermentations to test the stability of the resistance phenotype. After 10 days, L. casei EM77::cI conserved the ability to avoid phage infection. Finally, total DNA of L. casei EM77::cI after the 10 rounds of inoculation-fermentation was used as template for two independent PCR amplifications, one using the primers att1 and att7 and the other one using the primers b1 and int2 (Fig. 2A). In both cases the expected bands, of 0.3 and 1.8 kb, respectively, were amplified, confirming that there were no DNA rearrangements during milk fermentation.

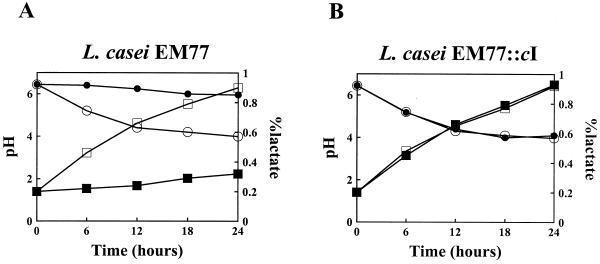

We show here that the presence of phage A2 did not have any effect on the evolution of titratable acidity and pH during fermentation of L. casei EM77::cI (4) (Fig. 4B). Curd formation was observed after about 8 h of incubation of L. casei EM77::cI with phage A2. However, in phage-contaminated milk inoculated with the control strain (L. casei EM77) significantly smaller variations were observed in both pH and lactate production (4) (Fig. 4A). Thus, milk did not coagulate even after 24 h of incubation.

FIG. 4.

Fermentation capacity of food-grade L. casei EM77 and L. casei EM77::cI strains in the presence of phage A2. Evaluation of lactic acid production (squares) and reduction of pH (circles) in milk inoculated with L. casei EM77 (A) or L. casei EM77::cI (B) in the absence (open symbols) or the presence (solid symbols) of phage A2 (multiplicity of infection, ∼10−4).

DISCUSSION

The pEM76 delivery system catalyzes the integration of DNA into the attB site present in the genome of LAB (Fig. 2). It has been documented that (i) the 44-kb phage A2 generates stable lysogens through integration of its DNA at the attB site of its host and (ii) a vector system containing the attP site of phage A2 integrates with high efficiency when the int gene is provided in cis (3, 4). It is likely, therefore, that we could clone, in different steps, up to 44 kb of food-grade DNA at the attB site without affecting cell fitness. In addition, we have constructed a clearing system and showed that the β-recombinase is able to catalyze the deletion of the non-food-grade genes used during the integration process. It is likely, therefore, that a lactobacillus chromatin-associated protein helps the β enzyme to catalyze recombination.

A system for generating unlabeled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes by homologous recombination has been previously described (17). However, to our knowledge, the present work constitutes the first attempt to employ two different types of site-specific recombinases to achieve the stable integration of vector DNA into the genome of LAB and the subsequent cleaning of non-food-grade sequences. Unlike the Cre-loxP system, which has been recently used for site-specific integration and excision of marker genes into and from the genomes on Agrobacterium cells (27), the A2 Int protein, in the absence of the A2 xis gene product, cannot catalyze the excision of the delivery cassette (3). This finding is consistent with the fact that after 10 successive milk fermentations, using as inoculum the whey of the previous one, the integrated material is stably maintained without the need for selective pressure.

The LAB food-grade cloning systems developed so far are mainly based in vectors whose DNA, including the selection markers, all derive from L. lactis (1, 9, 20, 24). The delivery and cleaning system constructed here facilitates genetic manipulation of starters: DNA manipulations, such as cloning, can be done in E. coli. Integration of vector DNA into the target strain by site-specific recombination and selection of transformants can be achieved by efficient non-food-grade markers. Once the vector is integrated in the selected strain, unwanted DNA can be easily eliminated. Since integration is stable (see above), even the non-food-grade selection markers can be deleted. It is also worth noting that our fermentation experiment indicated that neither the successive genetic manipulations nor the novobiocin treatment (used to eliminate the plasmid carrying the β-recombinase gene) had any effect on the viability or the technological functions of the strain. Even so, β-recombinase is now being cloned in a temperature-sensitive vector to facilitate plasmid curing. We consider the manipulated strain to be food grade because all of the remaining genes can already be found in a lactobacillus phage isolated from a food product (13). The recombination event leaves one copy of the noncoding six site, which has a dG+dC content in the DNA indistinguishable from that of LAB.

We have validated the use of the system for the easy generation of food-grade LAB strains making a stable food-grade L. casei strain completely immune to phage A2 infection during milk fermentation. Since the delivery system can be integrated in all LAB tested so far and also in E. coli without affecting cell fitness (3), we predict that, by using this system, it is possible to obtain engineered LAB that should keep their food-grade status. Moreover, easy modifications will allow us to extend the use of the clearing methodology to other biotechnologically important bacteria (2) and even to mammalian cells (8).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to M. Rosario Rodicio for critical reading of the manuscript and Rob Leer (TNO Voeding) for plasmid pBT825.

This work was supported by grant BIO4-CT96-0402 to J.E.S. and grants PB 96-0817 and BIO4-CT98-0250 to J.C.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison G E, Klaenhammer T R. Functional analysis of the gene encoding immunity to lactacin F, lafI, and its use as a Lactobacillus-specific, food-grade genetic marker. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4450–4460. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4450-4460.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso J C, Weise F, Rojo F J. The Bacillus subtilis histone-like protein Hbsu is required for DNA resolution and DNA inversion mediated by the β recombinase of plasmid pSM19035. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2938–2945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez M A, Herrero M, Suarez J E. The site-specific recombination system of the Lactobacillus species bacteriophage A2 integrates in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Virology. 1998;250:185–193. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez M A, Rodríguez A, Suárez J E. Stable expression of the Lactobacillus casei bacteriophage A2 repressor blocks phage propagation during milk fermentation. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:812–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canosa I, Lurz R, Rojo F, Alonso J C. β recombinase catalyzes inversion and resolution between two inversely oriented six sites on a supercoiled DNA substrate and only inversion on relaxed or linear substrates. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13886–13891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen B, Johnsen M G, Stenby E, Vogensen F K, Hammer K. Characterization of the lactococcal temperate phage TP901-1 and its site-specific integration. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1069–1076. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1069-1076.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly C, Fitzgerald G F, Davis R. Biotechnology of lactic acid bacteria with special reference to bacteriophage resistance. In: Venema G, Huis in't Veld J H J, Hugenholtz J, editors. Lactic acid bacteria: genetics, metabolism and applications. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. p. 3.14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Díaz V, Rojo F, Martinez-A C, Alonso J C, Bernad A. The prokaryotic β recombinase catalyzes site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6634–6640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickely F, Nilsson D, Hansen E B, Johansen E. Isolation of Lactococcus lactis nonsense suppressors and construction of a food-grade cloning vector. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupont L, Boizet-Bonhoure B, Coddeville M, Auvray F, Ritzenthaler P. Characterization of genetic elements required for site-specific integration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus bacteriophage mv4 and construction of an integration-proficient vector for L. plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:586–595. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.586-595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García P, Ladero V, Alonso J C, Suárez J E. Cooperative interaction of CI protein regulates lysogeny of Lactobacillus casei by bacteriophage A2. J Virol. 1999;73:3920–3929. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3920-3929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grindley N D F. Resolvase-mediated site-specific recombination. In: Eckstein F, Lilley D M J, editors. Nucleic acids and molecular biology. VIII. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 236–267. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrero M, de los Reyes-Gavilán C G, Caso J L, Suárez J E. Characterization of φ393-A2, a bacteriophage that infects Lactobacillus casei. Microbiology. 1994;140:2585–2590. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill C. Bacteriophage and bacteriophage resistance in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kiese T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H S. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: John Innes Institute; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladero V, García P, Bascarán V, Herrero M, Alvarez M A, Suárez J E. Identification of the repressor-encoding gene of the Lactobacillus bacteriophage A2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3474–3476. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3474-3476.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leenhouts K, Buist G, Bolhuis A, ten Berge A, Kiel J, Mierau I, Dabrowska M, Venema G, Kok J. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s004380050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leenhouts K J, Kok J, Venema G. Stability of integrated plasmids in the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2726–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2726-2735.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillehaug D, Nes I F, Birkeland N K. A highly efficient and stable system for site-specific integration of genes and plasmids into the phage φLC3 attachment site (attB) of the Lactococcus lactis chromosome. Gene. 1997;188:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00798-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacCormick C A, Griffin H G, Gasson M J. Construction of a food-grade host/vector system for Lactococcus lactis based on the lactose operon. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:105–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormac A C, Elliott M C, Chen D-F. PBECKS2000: a novel plasmid series for the facile creation of complex binary vectors, which incorporates “clean-gene” facilities. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:226–235. doi: 10.1007/s004380050961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nash H A. Site-specific recombination: integration, excision, resolution and inversion of defined DNA segments. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R III, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2363–2376. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novel G. Génétique moléculaire et génie génétique des bactéries lactiques. In: de Roissart H, Luquet F M, editors. Bactéries lactiques. Vol. 1. Uriage, France: Lorica; 1994. pp. 403–428. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platteeuw C, van Alen-Boerrigter I, van Schalkwijk S, de Vos W M. Food-grade cloning and expression system for Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1008–1013. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1008-1013.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posno M, Leer R J, van Rijn J M M, Lokman B C, Pouwels P H. Transformation of Lactobacillus plantarum by plasmid-DNA. In: Ganesan A T, Hoch J A, editors. Genetics and biotechnology of bacilli. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouwels P H, Leer R J, Shaw M, den Bak-Glashouwer M-J H, Tielen F D, Smit E, Martínez B, Jore J, Conway P L. Lactic acid bacteria as antigen delivery vehicles for oral immunization purposes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;41:155–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raya R R, Fremaux C, De Antoni G L, Klaenhammer T R. Site-specific integration of the temperate bacteriophage φadh into Lactobacillus gasseri chromosome and molecular characterization of the phage (attP) and bacterial (attB) attachment sites. J Bacteriol. 1995;174:5584–5592. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5584-5592.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritt C, Grimm R, Fernández S, Alonso J C, Grasser K D. Four differently chromatin-associated maize HMG domain proteins modulate DNA structure and act as architectural elements in nucleoprotein complexes. Plant J. 1998;14:623–631. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rojo F, Alonso J C. A novel site-specific recombinase encoded by the Streptococcus pyogenes plasmid pSM 19035. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:159–172. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salminen S, Isolauri E, Salminen E. Clinical uses of probiotics for stabilizing the gut mucosal barrier: successful strains and future challenges. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:347–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00395941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheirlink T, Mahillon J, Joos H, Dhaese P, Michiels F. Integration and expression of α-amylase and endoglucanase genes in the Lactobacillus plantarum chromosome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2130–2137. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2130-2137.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stiles M E. Biopreservation by lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00395940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suárez J E, Chater K F. Development of a DNA cloning system in Streptomyces using phage vectors. Ciencia Biol. 1981;6:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Guchte M, Daly C, Fitzgerald G F, Arendt E K. Identification of int and attP on the genome of lactococcal bacteriophage Tuc2009 and their use for site-specific plasmid integration in the chromosome of Tuc2009-resistant Lactococcus lactis MG1363. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2324–2329. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2324-2329.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei M Q, Rush C M, Nonma J M, Hafner L M, Epping R J, Timmus P. An improved method for the transformation of Lactobacillus strains using electroporation. J Microbiol Methods. 1995;21:97–109. [Google Scholar]