Abstract

Purpose of Study

To compare the outcomes of minimally invasive and open techniques in the surgical management of dorsolumbar and lumbar spinal tuberculosis (STB).

Methods

Skeletally mature patients with active STB involving thoracolumbar and lumbar region confirmed by radiology (X-ray, MRI) and histopathological examination were included. Healed and mechanically stable STB, patients having severe hepatic and renal impairment, coexisting spinal conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis, and patients unwilling to participate were excluded from the study. The patients were divided in to two groups, group A consisted of patients treated by MIS techniques and group B consisted of patients treated by open techniques. All the patients had a minimum follow-up of 24 months.

Results

A total of 42 patients were included in the study. MIS techniques were used in 18 patients and open techniques were used in 24 patients. On comparison between the two groups, blood loss (234 ml vs 742 ml), and immediate post-operative VAS score (5.26 vs 7.08) were significantly better in group A, whereas kyphotic correction (16° vs 33.25°) was significantly better in group B. Rest of the parameters such as duration of surgery, VAS score, ODI score and number of instrumented levels did not show significant difference between the two groups.

Conclusion

MIS stabilization when compared to open techniques is associated with significant improvement in immediate post-operative VAS scores. The MIS approaches at 2-year follow-up have functional results similar to open techniques. MIS is inferior to open techniques in kyphosis correction and may be associated with complications.

Keywords: Minimally invasive spine surgery, Spinal tuberculosis, Open decompression, Posterior instrumentation

Introduction

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS) has been gaining popularity in the last 2 decades because of decreased intraoperative blood loss, decreased tissue damage, shorter operative time, and reduced post-operative pain [1–5]. MIS techniques are being routinely applied to treat spinal disorders such as trauma, tumors, and deformity with good results [6–8]. MIS techniques for spondylodiscitis has steadily and increasingly been recognized as treatment for spinal tuberculosis (STB) [9, 10]. The goals of MIS are to achieve spinal decompression and stabilization matching that of its open counterpart while reducing iatrogenic muscle injury to the back [8].This concept can be used in spondylodiscitis patients who frequently suffer from severe comorbidities. MIS has the advantage of minimal tissue damage during the procedure and sparing of posterior midline structures leads to decreased pain, and superior functional outcome in post-operative period aiding in early rehabilitation [11, 12]. There is plethora of literature which compares MIS techniques and open techniques for spinal trauma and degenerative conditions, but there are very few such comparative studies in surgical management of STB. We conducted this prospective study to compare the outcomes of the two techniques with a hypothesis that all advantages of MIS techniques can be passed on to the cases of STB while achieving similar outcomes when compared to gold standard open techniques.

Materials and Methods

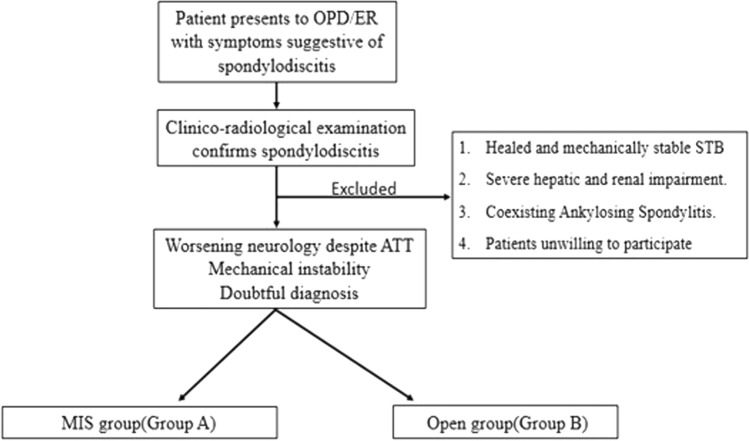

This was a prospective cohort study conducted in a tertiary health care center. After obtaining ethical clearance (Reg No: ECR/736/IEC/89), 42 patients were recruited into the study from June 2019 to June 2020 according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned below (Fig. 1). All the patients included in the study provided a written informed consent. Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were offered surgical intervention. Choice of surgery was discussed with the patient and final decision on the technique was made by the patient. The patients were grouped accordingly into two groups. Group A was treated by MIS technique and group B treated by open technique (examples Figs. 2 and 3). All the patients had a minimum follow-up of 24 months (24–30 months). Routine radiographs were done and final fusion was assessed using the criteria by Bridwell et al. [13].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing selection of the patients.

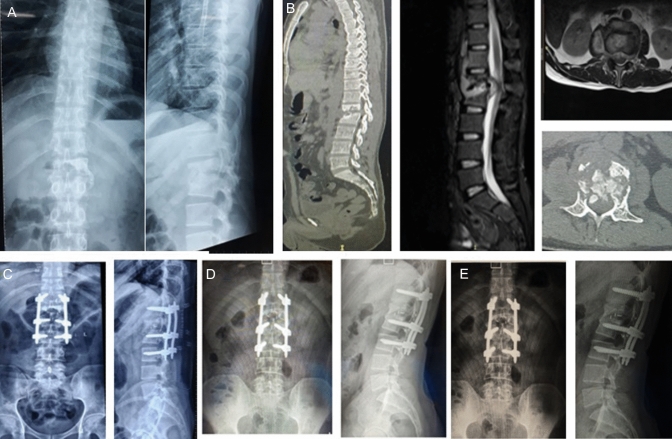

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative AP and lateral X-ray of Spinal Tuberculosis (L1-L2) treated by open technique (A); Pre-operative MRI and CT Scan sagittal and axial view (B); Immediate post-operative view (C); Follow up X-ray at 6 months (D); Final follow-up (E)

Fig. 3.

Pre-operative AP and lateral X-ray of Spinal Tuberculosis (L4-L5) treated by MIS technique (A); Pre-operative MRI scan sagittal and axial view (B, C); Immediate post-operative view (D); Follow up X-ray at 6 months (E); Final follow-up (F)

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: skeletally mature population (age group 18–60 years), patients with active spinal tuberculosis involving thoracolumbar (D10–L2) and lumbar (L2–3 disc-S1) tuberculosis confirmed by radiology (X-ray, MRI) and histopathological examination, mechanical instability of spine [14, 15], patient developing new neurological deficits, progressive deficits or deficits persisting during the course of conservative treatment (3–4 weeks), and severe pain and disability not responding to conservative methods.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria were: healed and mechanically stable STB, patients having severe hepatic and renal impairment, coexisting spinal conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis, and patients unwilling to participate in the study. The patients with multilevel STB requiring intervention in dorsal spine alongside dorsolumbar or lumbar spine were also excluded from the study.

Treatment Protocol

The patients were labeled as tubercular cases only after thorough clinico-radiologic examination and histopathological confirmation. The diagnostic workup included blood investigations (ESR, CRP, and screening for HIV status), radiographs, CT, and MRI scans. Antitubercular therapy was started according to institutional protocol, i.e., HRZE (Isoniazid (H) 5 mg/kg, Rifampicin (R) 10 mg/kg, Pyrazinamide (Z) 25 mg/kg, Ethambutol (E) 15 mg/kg) for 2 months and HRE for 10 months. Liver functions and erythrocyte sedimentation rates were monitored carefully at regular intervals. The patients who failed conservative management for STB were planned for surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Once the data were collected and tabulated, descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables. t-test was used to find the significance in changes of VAS, ODI scores, and kyphosis correction before and after surgery. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 42 patients were included in the study. The demographic details of both the groups are enumerated in Table 1. The intraoperative variables and radiologic outcomes in both the groups are enumerated in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic details of group A and group B

| Group A MIS n = 18 |

Group B (open) n = 24 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 43 years (24–60) | 36.7 years (18–60) | 0.15 |

| Sex (M/F) | 13/5 | 15/9 | 0.83 |

| Preop neurological deficit (A/B/C/D/E) | 1/0/3/2/12 | 4/1/2/1/16 | 0.88 |

| Indication (neurological deficit/instability or deformity/doubtful diagnosis) | 6/11/1 | 8/14/2 | 0.903 |

| Levels—single | 17 | 21 | 0.893 |

| Multilevel | 1 | 3 | – |

| Dorsolumbar | 10 | 16 | – |

| Lumbar | 8 | 8 | – |

Table 2.

Intraoperative variables and radiologic outcomes in group A and group B

| Clinical parameters | Pre-operative score (mean ± SD) (Group A) |

Post-operative score (mean ± SD) (Group A) |

p value | Pre-operative score (Mean ± SD) (Group B) |

Post-operative score (mean ± SD) (Group B) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | 8.93 ± 0.59 | 2.93 ± 1.03 | < 0.05 | 8.25 ± 0.59 | 2.29 ± 0.85 | < 0.05 |

| ODI | 89.5 ± 5.06 | 21.2 ± 6.36 | < 0.05 | 87.9 ± 11.02 | 28.25 ± 8.27 | < 0.05 |

| Kyphotic angle DL spine | + 17.14° ± 7.01 | 7.42° ± 3.73 | < 0.05 | + 17.69 ± 9.26 | 5.38 ± 6.85 | < 0.05 |

| Kyphotic angle lumbar spine | + 6° ± 20 | − 17.5° ± 4.98 | < 0.05 | + 19.27 ± 14.87 | − 19.1 ± 5.088 | < 0.05 |

Comparison Between Group A and Group B

On comparing the group A and group B, kyphotic correction, post-operative VAS score and blood loss showed significant difference. The other parameters such as duration of surgery, VAS score, ODI score and number of instrumented levels did not show any significant difference between the two groups. The details are enumerated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between group A and group B

| Group A MIS | Group B open | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood loss | 234.6 ± 276.9 ml | 742.08 ± 652.49 ml | 0.00040 |

| Duration | 191.3 ± 50.54 min | 204.16 ± 64.06 min | 0.51 |

| Immediate VAS score | 5.26 ± 1.16 | 7.08 ± 1.01 | 0.000016 |

| Final VAS | 2.93 ± 1.03 | 2.29 ± 0.85 | 0.08 |

| Final ODI Score | 21.2 ± 6.36 | 28.25 ± 8.27 | 0.09 |

| Kyphosis correction DL spine | 10.43° ± 3.64 | 10.69° ± 4.27 | 0.88 |

| Kyphosis correction lumbar spine | 16° ± 11.83 | 33.25 ± 13.41 | 0.002 |

| Instrumented levels | 4.06 ± 0.96 | 4.75 ± 1.22 | 0.06 |

Improvement in the Neurological Deficits

All the patients with neurological deficits in both the groups had improvement in neurology by at least one grade. In group A, patients with DL spine involvement, incomplete neurological deficits were seen in 3 patients (Frankel C). One of them improved to Frankel D and the other two improved to Frankel E. One patient with complete neuro-deficit (Frankel A) improved to Frankel D. Two of the patients (2/6) of lumbar STB with weakness of EHL (MRC3/5) recovered fully at final follow-up. Among four of the neurologically intact patients, one had deterioration of neurology in the post-operative period.

In group B, two patients of lumbar STB had weakness of ankle dorsiflexors and EHL which completely recovered in the final follow-up. In the dorsolumbar STB, four patients had Frankel A neurology, among which three improved to Frankel D and one improved to Frankel C. One patient of Frankel B improved to Frankel D and one patient of Frankel D improved to Frankel E.

Complications

In group A, there was one case of post-operative worsening of neurology which had to be taken up for repeat decompression in the immediate post-operative period. The patient’s neurology improved in the follow-up to ambulatory level. There was one case of superficial infection which healed with regular dressings. There was one case with renal artery injury, which had significant bleeding and nephrectomy was done to control the bleeding in the patient. One case had implant back out from the distal screw entry site at 3 months. The back out stabilized at 6 months and 9 months and so removal was not done.

In group B, there was one case of post-operative infection who required regular dressings before it healed. There was one case of proximal junctional failure (PJF) and one case of screw pull out (Fig. 4). Both the cases were re-operated and fusion levels were extended. Good fusion was obtained in the screw pull out case at 1-year follow-up, whereas the patient with proximal junctional failure (PJF) is under routine observation without any complaints. The complications are summarized in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Pre-operative AP and lateral X-ray of Spinal Tuberculosis (L3-L4) (A); Pre-operative MRI and CT Scan sagittal and axial view (B); Immediate post-operative view (C); Follow up X-ray at 6 months showing failure (D); Immediate revision post-operative view (E); Follow up X-ray after revision at 6 months (F); Final follow-up (G)

Table 4.

Complications

| Complications | Group A (MIS) | Group B (Open) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological | 1 | 0 | – |

| Implant related | 2 (screw pullout) | 2 (1PJF* + 1 screw pullout) | 0.57 |

| Wound related | 1 (infection) | 1 | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | 1 (renal artery injury) | – | – |

Discussion

The objective of using MIS in STB is to reach the affected area through as minimal a surgical corridor as possible and to reduce iatrogenic trauma to the surrounding tissues. The anticipated advantages of MIS techniques are decreased post-operative pain, less chances of acute and chronic muscular dysfunction, and hence improved functional recovery. These factors may potentially lead to a significant reduction of in-hospital stay and rehabilitation time [16]. The operative duration between the two groups in our study was not significantly different and was similar to the various studies in the literature. The mean duration of surgery in our study in group A was 191.33 min and 204.16 min in group B. The operative duration in a study done by Kandwal et al. was 255 min which was similar to our study group. In a study done by Fan et al., where minimally invasive techniques were used to treat lumbar tuberculosis, the mean operative duration was 185 min [17]. Prolonged operative duration has been shown to increase the risks of anesthetic-related and surgical site infections [18]. Whenever feasible, it is always better to choose a technique which has similar advantages to open techniques but can be done in a shorter duration. This reduces the infection rates, bleeding and also anesthetic complications. One theoretical concern of MIS techniques in the initial phases is that it has a significant learning curve which may increase the surgical time in the beginning but as the experience increases, the time duration is comparable to open techniques and in the long term the advantages outweigh the steep learning curve. One of the many advantages of MIS techniques is minimal blood loss during the procedure. The studies done in the past show a similar trend where the blood loss was higher in open techniques and lower in MIS techniques. Chen et al. [19] did a study comparing open techniques and minimally invasive techniques where the results confirmed that the groups treated by percutaneous instrumentation showed a marked reduction in intraoperative blood loss. The minimally invasive group in our study had less blood loss (234.6 vs 742.08 ml) when compared to the open group. However, the number of multilevel cases was more in the open group (3 cases) as compared to the MIS group (1 case). The blood loss reported by Fan et al. in his study was 165 ml which was lesser than our study group. This minor difference can be due to the various retractor systems and the stage of the disease being treated [17].

The surgical treatment of spinal tuberculosis should also focus on the correction of local kyphosis and restoring the normal curvatures of spine [20, 21]. The kyphosis correction in both the groups of our study was significant. The kyphosis was studied separately for dorsolumbar (DL) spine and for lumbar spine. The improvement in kyphosis in open lumbar group was significantly higher than the MIS group. Numerous studies have confirmed that posterior instrumentation not only helps in correction of the kyphotic angle, but also allows early mobilization, improve surgical outcomes, and accelerates healing [22, 23]. In two studies by Lee et al. [24] and Pu et al. [25] using conventional methods of posterior transpedicular decompression and fixation, mean pre-operative kyphosis ranged from 18° to 24° which was corrected by 4°–8°, over a mean follow-up of 22.5 months [25].Once the disease heals, the kyphotic deformity does not progress and this was shown by Upadhyay et al. [26] and Jain et al. [27] in their studies on surgically treated cases of STB.

The functional outcomes of MIS techniques and open techniques were evaluated by the VAS scores and ODI scores. Our study showed significant improvement in VAS scores post-operatively across both the groups. However, the immediate post-operative VAS scores were significantly better in MIS group. In a study done by Jain A et al. [28] where the study group compared the outcomes in cases of Potts spine, the improvement of VAS score was from 8.7 to 1.1 post-operatively at 1-year follow-up. In similar studies done by Yadav G et al. [12], the VAS score improved from 7.48 ± 1.16 pre-operatively to 0.47 ± 1.94 post-operatively. Wu et al. [29] also did a study in which the pain score improved from 7.9 ± 1.2 to 2.9 ± 1.1. El-sharkawi et al. [30] in his study showed the improvement of VAS scores from 8.5 ± 1.3 pre-operatively to 1.8 ± 1.1 post-operatively. Debridement of the lesion and stabilization along with antitubercular drugs provides pain relief in majority of cases due to reduced spasm of the muscles and decreased instability. Any pain on movement in the bed should raise the suspicion of instability and should be considered for stabilization irrespective of neurological status of the patient. The improvement in ODI may be due to either improvement in neurology or due to improvement in the alignment and stability of affected spine. The mean pre-operative ODI score improved from 89.5 ± 5.06 to 21.2 ± 6.36 in group A and from 87.9 ± 11.02 to 28.25 ± 8.27 in group B. In a study done by Yadav et al., the ODI score pre-operatively was 76.4 ± 17.9 which improved post-operatively to 6.74 ± 17.2. The improvement in ODI score has been found to be consistent with improvement in VAS score throughout the literature [31]. Most of the studies in the literature which report outcomes of STB treated surgically, observed for post-operative improvement in functional scores and reported a positive functional outcome following surgery [30, 32, 33]. There are very few studies in the literature which compare the functional outcomes of open and minimally invasive techniques. Tschugg et al. [4] did one such study where 67 patients of lumbar spondylodiscitis were treated by minimally invasive techniques. The authors reported over all pain relief at discharge was significantly better in MIS group compared to the open group and the duration of hospital stay was longer in the open group. When the VAS scores were compared in our study, we observed similar results where the immediate pain relief was much better in the MIS group when compared to the open group. However, at the final follow-up both the open and MIS group had similar pain relief. Further Tschugg et al. did not report the improvement/deterioration in the kyphosis of the diseased levels, but measured the disc heights of the affected levels in both the groups but did not find any significant difference in both the groups.

Neurological deficits in STB occur mainly due to compression of the thecal sac, kyphotic deformity, and instability. The aim of surgical treatment of STB is to address the compression and instability. The STB may heal with medical treatment alone when there is no significant compression and instability [34]. All the patients had improvement in neurology by at least one grade. In a study done by Garg et al., all the patients in the study who were treated by MIS decompression and stabilization reached full power at the final follow-up [35]. Case reports described by Ito et al. [36] and Rigotti et al. [11] also showed neurological improvement in patients treated by minimally invasive methods. Kandwal et al. [8] studied the patients of STB treated with percutaneous instrumentation and debridement with retractor system. All the patients in the study had neurological improvement. The results shown by these studies are similar to the results for neurological improvement in our study and these studies prove that good neurologic recovery can be achieved even by MIS techniques [6, 8, 37]. This also proves that debridement and stabilization when done by minimally invasive techniques definitely gives rise to improvement in neurological status.

None of the patients underwent implant removal in our study. Implant removal remains controversial in those who undergo fixation without fusion, as it requires second surgery and general anesthesia. Studies done by De Iure [38] and Court and Vincent [39] on patients with spinal fractures treated by percutaneous transpedicular fixation methods show that the need for implant removal may be low, as few patients have clinical or radiographic evidence of failure. Infective pathologies may behave differently, as fusions between involved bodies occur in them. Lee et al. [24] did not remove screws in any of their ten patients with infective spondylodiscitis at a mean follow-up of 29 months (maximum, 61 months), although they noticed screw loosening in three patients. We in our study did not remove implants after the disease healed. Removal of implant also means subjecting the patient to another surgery and increased cost in the overall treatment. However, no proven advantages are present in the literature with regard to implant removal after the treatment.

The main goal of MIS techniques in spine surgery is to achieve the same results comparable to open procedures via an approach which is less traumatic. Although minimizing approach-related morbidity is the primary aim of MIS, this must be accomplished without compromising the efficacy of the intended procedure. Due to minimal tissue trauma and minimal damage to tissues, MIS techniques may reduce the amount of iatrogenic injury while still safely accomplishing the goals of the conventional open techniques.

Limitations of the Study

Though this is a prospectively conducted study comparing the outcomes of patients of STB by MIS and Open techniques, there are certain limitations in this study. Small sample size is possibly a drawback of the study. Lack of randomization could have bearing on the outcome. Though our study showed less blood loss in the MIS group, the multilevel cases were more in the open group. This could potentially create a bias in the assessment and comparison of blood loss between the two groups. The distribution of cases with neurologic deficits is asymmetric between the two groups due to lack of randomization. Longer follow-up is desirable to verify the difference in the outcomes of the two procedures.

Conclusion

The advantages of MIS techniques when compared to open techniques are low immediate post-operative VAS scores which translates to better and early rehabilitation. However, MIS approaches at 2-year follow-up is associated with functional results similar to open techniques. Kyphosis correction potential of MIS techniques on the other hand is inferior to open group and MIS may be associated with complications especially during learning curve.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rieger B, Jiang H, Ruess D, Reinshagen C, Molcanyi M, Zivcak J, et al. First clinical results of minimally invasive vector lumbar interbody fusion (MIS-VLIF) in spondylodiscitis and concomitant osteoporosis: A technical note. European Spine Journal: Official Publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2017;26(12):3147–3155. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4928-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan NR, Clark AJ, Lee SL, Venable GT, Rossi NB, Foley KT. Surgical outcomes for minimally invasive vs open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(6):847–874. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turel MK, Kerolus M, Deutsch H. The role of minimally invasive spine surgery in the management of pyogenic spinal discitis. Journal of Craniovertebral Junction & Spine. 2017;8(1):39–43. doi: 10.4103/0974-8237.199873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tschugg A, Hartmann S, Lener S, Rietzler A, Sabrina N, Thomé C. Minimally invasive spine surgery in lumbar spondylodiscitis: A retrospective single-center analysis of 67 cases. European Spine Journal. 2017;26(12):3141–3146. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin T-Y, Tsai T-T, Lu M-L, Niu C-C, Hsieh M-K, Fu T-S, et al. Comparison of two-stage open versus percutaneous pedicle screw fixation in treating pyogenic spondylodiscitis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayaswal A, Upendra B, Ahmed A, Chowdhury B, Kumar A. Video-assisted thoracoscopic anterior surgery for tuberculous spondylitis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2007;460:100–107. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318065b6e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLain RF. Spinal cord decompression: An endoscopically assisted approach for metastatic tumors. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(9):482–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandwal P, Upendra B, Jayaswal A, Garg B, Chowdhury B. Outcome of minimally invasive surgery in the management of tuberculous spondylitis. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2012;46(2):159. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.93680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kandwal P, VijayaraghavanJayaswal GA. Management of tuberculous infection of the spine. Asian Spine Journal. 2016;10(4):792–800. doi: 10.4184/asj.2016.10.4.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahuja K, Gupta T, Ifthekar S, Mittal S, Yadav G, Kandwal P. Variability in management practices and surgical decision making in spinal tuberculosis: an expert survey-based study. Asian Spine Journal. 2022;16(1):9–19. doi: 10.31616/asj.2020.0557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rigotti S, Boriani L, Luzi CA, Marocco S, Angheben A, Gasbarrini A, et al. Minimally invasive posterior stabilization for treating spinal tuberculosis. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2013;14(2):143–145. doi: 10.1007/s10195-012-0184-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav G, Kandwal P, Arora SS. Short-term outcome of lamina-sparing decompression in thoracolumbar spinal tuberculosis. Journal of Neurosurgery Spine. 2020 doi: 10.3171/2020.1.SPINE191152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, McEnery KW, Baldus C, Blanke K. Anterior fresh frozen structural allografts in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Do they work if combined with posterior fusion and instrumentation in adult patients with kyphosis or anterior column defects? Spine. 1995;20(12):1410–1418. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199506020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahuja K, Kandwal P, Ifthekar S, Sudhakar PV, Nene A, Basu S, et al. Development of tuberculosis spine instability score (TSIS): An evidence-based and expert consensus-based content validation study among spine surgeons. Spine. 2022;47(3):242–251. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahuja K, Ifthekar S, Mittal S, Yadav G, Sarkar B, Kandwal P. Defining mechanical instability in tuberculosis of the spine: A systematic review. EFORT Open Reviews. 2021;6(3):202–210. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.6.200113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens KJ, Spenciner DB, Griffiths KL, Kim KD, Zwienenberg-Lee M, Alamin T, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive and conventional open posterolateral lumbar fusion using magnetic resonance imaging and retraction pressure studies. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2006;19(2):77–86. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000193820.42522.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan W, Yang G, Zhou T, Chen Y, Gao Z, Zhou W, et al. One-stage freehand minimally invasive pedicle screw fixation combined with mini-access surgery through OLIF approach for the treatment of lumbar tuberculosis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2022;17(1):242. doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03130-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leong G, Wilson J, Charlett A. Duration of operation as a risk factor for surgical site infection: Comparison of English and US data. The Journal of Hospital Infection. 2006;63(3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen MJ-W, Niu C-C, Hsieh M-K, Luo A-J, Fu T-S, Lai P-L, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody debridement and fusion with percutaneous pedicle screw instrumentation for spondylodiscitis. World Neurosurgery. 2019;128:e744–e751. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ifthekar S, Yadav G, Ahuja K, Mittal S, Venkata SP, Kandwal P. Correlation of spinopelvic parameters with functional outcomes in surgically managed cases of lumbar spinal tuberculosis—A retrospective study. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2022;26:101788. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2022.101788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal N, Ahuja K, Yadav G, Gupta T, Ifthekar S, Kandwal P. PEEK vs titanium cage for anterior column reconstruction in active spinal tuberculosis: A comparative study. Neurology India. 2021;69(4):966. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.325384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klöckner C, Valencia R. Sagittal alignment after anterior debridement and fusion with or without additional posterior instrumentation in the treatment of pyogenic and tuberculous spondylodiscitis. Spine. 2003;28(10):1036–1042. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000061991.11489.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W-J, Wu C-C, Jung C-H, Chen L-H, Niu C-C, Lai P-L. Combined anterior and posterior surgeries in the treatment of spinal tuberculous spondylitis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2002;398:50–59. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S-H, Sung J-K, Park Y-M. Single-stage transpedicular decompression and posterior instrumentation in treatment of thoracic and thoracolumbar spinal tuberculosis: A retrospective case series. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2006;19(8):595–602. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211241.06588.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pu X, Zhou Q, He Q, Dai F, Xu J, Zhang Z, et al. A posterior versus anterior surgical approach in combination with debridement, interbody autografting and instrumentation for thoracic and lumbar tuberculosis. International Orthopaedics. 2012;36(2):307–313. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1329-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Upadhyay SS, Saji MJ, Sell P, Sell B, Yau AC. Longitudinal changes in spinal deformity after anterior spinal surgery for tuberculosis of the spine in adults. A comparative analysis between radical and debridement surgery. Spine. 1994;19(5):542–549. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain AK, Dhammi IK, Jain S, Mishra P. Kyphosis in spinal tuberculosis—Prevention and correction. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2010;44(2):127–136. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.61893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain A, Jain RK, Kiyawat V. Evaluation of outcome of transpedicular decompression and instrumented fusion in thoracic and thoracolumbar tuberculosis. Asian Spine Journal. 2017;11(1):31–36. doi: 10.4184/asj.2017.11.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu P, Luo C, Pang X, Xu Z, Zeng H, Wang X. Surgical treatment of thoracic spinal tuberculosis with adjacent segments lesion via one-stage transpedicular debridement, posterior instrumentation and combined interbody and posterior fusion, a clinical study. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2013;133(10):1341–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Sharkawi MM, Said GZ. Instrumented circumferential fusion for tuberculosis of the dorso-lumbar spine. A single or double stage procedure? International Orthopaedics. 2012;36(2):315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeraagunta T, Yerramneni VK, Kanala RR, Gaikwad G, Kumar HDP, Phutane AS. Minimally invasive spinal fusion and decompression for thoracolumbar spondylodiscitis. Journal of Craniovertebral Junction and Spine. 2020;11(1):17. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_24_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, Huang S, Guo H, Ge L, Sheng B, Wang Y, et al. A clinical study of internal fixation, debridement and interbody thoracic fusion to treat thoracic tuberculosis via posterior approach only. International Orthopaedics. 2012;36(2):293–298. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1449-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaveri GR, Mehta SS. Surgical treatment of lumbar tuberculous spondylodiscitis by transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) and posterior instrumentation. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2009;22(4):257–262. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31818859d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhojraj S, Nene A. Lumbar and lumbosacral tuberculous spondylodiscitis in adults. Redefining the indications for surgery. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British. 2002;84(4):530–534. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b4.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garg N, Vohra R. Minimally invasive surgical approaches in the management of tuberculosis of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2014;472(6):1855–1867. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3472-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito M, Sudo H, Abumi K, Kotani Y, Takahata M, Fujita M, et al. Minimally invasive surgical treatment for tuberculous spondylodiscitis. Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery. 2009;52(05/06):250–253. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lü G, Wang B, Li J, Liu W, Cheng I. Anterior debridement and reconstruction via thoracoscopy-assisted mini-open approach for the treatment of thoracic spinal tuberculosis: Minimum 5-year follow-up. European Spine Journal: Official Publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2012;21(3):463–469. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Iure F, Cappuccio M, Paderni S, Bosco G, Amendola L. Minimal invasive percutaneous fixation of thoracic and lumbar spine fractures. Minimally Invasive Surgery. 2012;2012:e141032. doi: 10.1155/2012/141032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Court C, Vincent C. Percutaneous fixation of thoracolumbar fractures: Current concepts. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research: OTSR. 2012;98(8):900–909. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]