Abstract

Background

Balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) is a method for the management of osteoporotic vertebral body fracture (OVF). However, improvement in back pain (BP) is poor in some patients, also previous reports have not elucidated the exact incidence and risk factors for residual BP after BKP. We clarified the characteristics of residual BP after BKP in patients with OVF.

Hypothesis

In this study, we hypothesize that some risk factors may exist for residual BP 2 years after the treatment of OVF with BKP.

Patients and Methods

A multicenter cohort study was performed where patients who received BKP within 2 months of OVF injury were followed-up for 2 years. BP at 6 months after surgery and final observation was evaluated by Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score. Patients with a score of 40 mm or more were allocated to the residual BP group, and comparisons between the residual back pain group and the improved group were made for bone density, kyphosis, mobility of the fractured vertebral body, total spinal column alignment, and fracture type (fracture of the posterior element, pedicle fracture, presence or absence of posterior wall damage, etc.). Also, Short Form 36 (SF-36) for physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) at the final follow-up was evaluated in each radiological finding.

Results

Of 116 cases, 79 (68%) were followed-up for 2 years. Two years after the BKP, 26 patients (33%) experienced residual BP. Neither age nor sex differed between the groups. In addition, there was no difference in bone mineral density, BKP intervention period (period from onset to BKP), and osteoporosis drug use. However, the preoperative height ratio of the vertebral body was significantly worse in the residual BP group (39.8% vs. 52.1%; p = 0.007). Two years after the operation, the vertebral body wedge angle was significantly greater in the residual BP group (15.7° vs. 11.9°; p = 0.042). In the multiple logistic regression model with a preoperative vertebral body height ratio of 50% or less [calculated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve], the adjusted odds ratio for residual BP was 6.58 (95% confidence interval 1.64–26.30; p = 0.007); similarly, patients with vertebral body height ratio less than 50% had a lower score of SF-36 PCS 24.6 vs. 32.2 p = 0.08.

Conclusion

The incidence of residual BP 2 years after BKP was 33% in the current study. The risk factor for residual BP after BKP was a preoperative vertebral body height ratio of 50% or less, which should be attentively assessed for the selection of a proper treatment scheme and to provide adequate stabilization.

Level of Evidence

III.

Keywords: Osteoporotic vertebral fracture, Back pain, Balloon kyphoplasty, Vertebral height, 2-Year follow-up study

Introduction

The risk of osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVF) increases in older people. In post-menopausal women, the lifetime incidence risk increases by 16% yearly. Osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVF) occur in 15% of women aged 50–59 years and in 50% of women >85 years of age [1–4]. The majority of OVFs are asymptomatic and occur in the absence of specific trauma. However, even these mild fractures could have clinical consequences for the patient because of the increased risk of future fractures, which may be symptomatic and mainly associated with morbidity and mortality among them [5–7].

Different treatment strategies are available for pain and preventing deterioration and deformity in patients with OVF. These strategies may include medications, bed rest, and bracing, which may be partially effective [8]. On the other hand, previous reports have often described the failure of a conservative treatment to improve pain and mobility [9]. Recently, minimally invasive approaches have been gradually adopted [10–13]. From previous reports, balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) has been identified as an effective, efficient, and safe method for the management of pathological vertebral compressive fractures [14, 15]. Based on a previously published report of 119 patients with OVF, 3.8% of patients who underwent BKP required revision surgery within 2 years of follow-up. Revision surgery was indicated for the cases with potential risk factors [16]. Meanwhile, infection, progressive kyphosis, and neurological dysfunction were also reported as causes of revision surgery [17]. The cause of post-operative back pain (BP) in patients who undergo BKP is not yet well understood and is controversial; moreover, to the best of our knowledge, the incidence and risk factors of BP after BKP have not been previously reported, which may have affected the patient’s quality of life.

The aim of the current study was, therefore, to evaluate the risk factors for residual BP 2 years after the treatment of OVF with BKP.

Patients and Methods

Patients

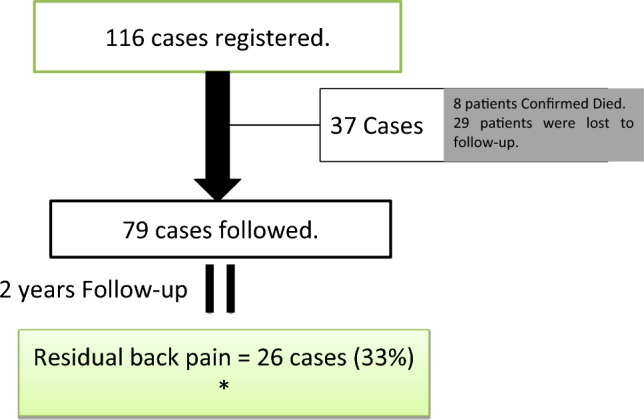

This study was designed as a retrospective review of patient data from a multicenter cohort. A total of 116 patients with single-level OVF were initially included; among them, 8 patients were confirmed as deceased, and 29 others were lost to follow-up. Inclusion criteria were old age patients, single-level OVF, fracture of thoracolumbar/ lumbar level, within 2 months of initial injury. Exclusion criteria were neurological deficits, multilevel fractures, pathological fractures, suspected underlying malignant disease, and dementia due to the unreliability of clinical outcomes. Seventy-nine patients with OVF who were followed-up in six health facilities for at least 2 years between 2015 and 2019 (Fig. 1) were enrolled. Each patient underwent a simple X-ray, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging before undergoing BKP. Study eligibility was determined after initial clinical and radiographic evaluation, all radiological parameters were independently evaluated blind to two groups by specialist spine surgeons. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka City University (No. 3174) Informed consent was obtained from the patients prior to study participation. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan. [16].

Fig. 1.

Patient flowchart

Methods

Surgical Procedure

We accomplished BKP with the Kyphon Inc. system, as described by Robinson et al. [18]. Once the surgery was completed, final radiographic images were taken to confirm the position of the bone cement. Finally, skin incision sites were sterilized, and the tape was applied.

Method of Assessment

Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation

The BKP was accomplished at multiple centers within 2 months of the injury for consecutive OVFs, and patients were followed-up for 2 years. Back pain at preoperative, 6 months after surgery, and the final observation was evaluated using the VAS score. Patients with a VAS score of 40 mm or more were allocated to the residual BP group. Patients with a VAS score <40 mm were allocated to the improved group, and comparisons were performed between the groups. The clinical parameters examined were bone density, duration of BP, treatment for osteoporosis, 36-item Short Form Health Survey Physical and Mental components (SF-36 PCS, and MCS) at the final follow-up using univariate analysis in each radiological finding such as spinous process, lamina, pedicle fractures, upper endplate deficit, vertebral body height ratio less than 50% (Fig. 1), and preoperative, 6 months after surgery, and the final follow-up VAS for BP. For the evaluation of radiological parameters and fracture specifications, we used lateral view dynamic X-ray, and computed tomography scan, taken preoperatively. The wedge angle of fractured vertebrae was quantified preoperatively and 7 days after BKP surgery (Fig. 2). The existence of pedicle and spinous process fracture was confirmed [16]. In addition, we assessed kyphosis and mobility of the fractured vertebral body, total spinal column alignment, preoperative fracture type (fracture of the posterior element, pedicle fracture, presence, or absence of posterior wall damage, etc.), upper/lower end-plates deficit, and vertebral body height ratio [16]. Preoperatively and in the final follow-up, the correction rate (rate of vertebral body restoration immediately after the BKP) and correction loss (loss of vertebral body restoration in the latest follow-up) were evaluated using simple radiographs in flexion and extension positions 2 years after the BKP.

Fig. 2.

A 74-year-old female with an osteoporotic vertebral fracture of L1, with a large angular motion of 15° between the extension and flexion position and height ratio of less than 50%. c,d Radiographs obtained at 1 week after balloon kyphoplasty. e Percentage height of the anterior wall as calculated by the following formula:

Statistical Analysis

The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was performed to indicate the cutoff point for the vertebral body height ratio. The Chi-squared (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test and t test were used.

The odds ratio (OR) of variables for residual BP was calculated. We included the following possible confounding factors in multivariate analysis: age, sex, angular motion, vertebral body height ratio of more than 50%, and spinous process fracture. Findings were counted as significant at p < 0.05. SAS Institute, Cary, NC version 9.4 software was used for analyses of our data [16].

Results

Demographics

A total of 79 (68%) patients with OVF were followed-up. All the patients were aged 65 years or older, and females accounted for 84.5% of the study population. The average age of the patients was 79 years in the residual BP group, while it was 77.6 years in the improved group. Two years after the BKP surgery, 26 patients (33%) reported residual BP. There was no difference between the baseline characteristics and the demographic data obtained at the final follow-up, such as age or sex, postoperative bone mineral density, BKP intervention period (period from onset to BKP), and osteoporosis drug use among the patients in the residual BP group and those in the improved group (Table 1). The SF-36 PCS and MCS did not show significant differences between patients having the spinous process fractures, lamina fractures, pedicle fractures, and upper endplate deficit and patients without mentioned fractures, but patients with vertebral body height ratio less than 50% had a lower score of SF-36 PCS 24.6 vs. 32.2 p = 0.08 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of patients having osteoporotic vertebral fractures treated with balloon kyphoplasty

| RBP group n = 26 |

Improved group n = 53 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79.0 (5.1) | 77.6 (5.8) | 0.299 |

| Sex, female | 21 (84%) | 45 (85%) | 0.918 |

| Affected level | |||

| Thoracic level (T7–T10) | 1 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1.000 |

| Thoracolumbar level (T11–L2) | 23 (88%) | 45 (85%) | |

| Lumbar level (L3–L4) | 2 (8%) | 6 (11%) | |

| BMD | 0.64 (0.2) | 0.54 (0.1) | 0.069 |

| Duration of BP (m) | 35.5 (50.90) | 41.5 (79.5) | 0.692 |

| VAS score (mm) | |||

| Preoperative | 79.6 (19.5) | 72.0 (25.7) | 0.147 |

| Postop 6 months | 50.8 (25.2) | 18.8 (21.9) | < 0.001 |

| Final follow-up | 61.7 (13.2) | 11.8 (10.4) | < 0.001 |

BMD bone mineral density, RBP residual back pain, VAS score Visual Analog Scale

Table 2.

Comparison of SF-36 at final follow-up in each radiological findings using univariate analysis

| SF-36 PCS | p value | SF-36 MCS | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiological finding | Radiological finding | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Spinous process fracture | 22.8 (22.9) | 28.0 (18.7) | 0.497 | 44.6 (13.9) | 52.6 (10.6) | 0.074 |

| Lamina fracture | 33.0 (7.0) | 28.8 (19.1) | 0.419 | 48.3 (7.9) | 52.1 (11.4) | 0.397 |

| Pedicle fracture | 29.2 (21.3) | 27.2 (18.9) | 0.799 | 60.7 (10.4) | 50.7 (10.4) | 0.100 |

| Upper endplate deficit | 27.8 (19.1) | 26.7 (19.3) | 0.837 | 51.8 (11.9) | 51.4 (9.1) | 0.887 |

| Preoperative vertebral body height ratio (less than 50%) | 24.6 (20.5) | 32.2 (15.6) | 0.084 | 49.8 (10.7) | 53.7 (11.4) | 0.159 |

Radiographic Evaluation

Imaging analysis revealed that 68 patients had OVF at the thoracolumbar level (T11-L2) and 8 had OVF at the lumbar level (L3-L4). Preoperative parameters were significantly worse in the residual BP group compared with the improved group; univariate analysis (Table 3) showed the height ratio of the vertebral body as 39.8% vs. 52.1% (p = 0.007), wedge angle of 21.3° vs. 17.2° (p = 0.014), vertebral body motion angle of 9.3° vs. 6.5° (p = 0.044), and local motion angle of 14.2° vs. 9.8° (p = 0.015) in the residual BP vs. the improved group. In addition, the upper endplate deficit was significantly higher: 80.7% vs. 62.2% (p = 0.001) in the residual BP group than that in the improved group (Table 4).

Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative radiographic parameters’ comparative assessment between residual back pain vs. improved groups following balloon kyphoplasty

| RBP group n = 26 |

Improved group n = 53 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | |||

| Wedge angle | 21.3 (5.4) | 17.2 (8.2) | 0.014* |

| Vertebral body motion angle | 9.3 (5.5) | 6.5 (4.9) | 0.044* |

| Local kyphosis | 26.1 (9.9) | 20.8 (16.1) | 0.088 |

| Local motion angle | 14.2 (7.1) | 9.8 (6.7) | 0.015* |

| Vertebral height ratio 50% | 39.9 (13.9) | 52.1 (18.6) | 0.007* |

| Postop | |||

| Vertebra wedge angle | 15.7 (7.4) | 11.9 (7.7) | 0.042* |

| Local kyphosis | 26.2 (12.5) | 27.1 (14.6) | 0.453 |

| Vertebral height ratio | 62.1 (15.0) | 66.7 (12.0) | 0.175 |

| Correction rate | 47.2 (9.4) | 30.0 (22.5) | 0.009* |

| Correction loss | 21.3 (9.3) | 14.3 (13.6) | 0.045* |

| SVA | 82.5 (51.9) | 86.0 (71.7) | 0.870 |

| PI–LL | 27.7 (20.0) | 16.3 (24.9) | 0.043* |

SVA sagittal vertical axis, PI–LL pelvic incidence–lumbar lordosis

*Significant high difference compared with the residual back pain group

Table 4.

Risk factors for residual back pain after balloon kyphoplasty using univariate analysis

| VAS for back pain 2 years = <40 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved group N (%) |

RBP group N (%) |

||

| Spinous process fracture | |||

| No | 48 (63.16) | 19 (25) | 0.050* |

| Yes | 3 (3.95) | 6 (7.9) | |

| Lamina fracture | |||

| No | 47 (61.84) | 21 (27.63) | 0.272 |

| Yes | 4 (5.25) | 4 (5.26) | |

| Pedicle fracture | |||

| No | 47 (61.84) | 23 (30.26) | 0.221 |

| Yes | 4 (5.25) | 2 (2.63) | |

| Upper endplate deficit | |||

| No | 18 (23.68) | 4 (5.25) | 0.001* |

| Yes | 33 (43.42) | 21 (27.63) | |

*Significantly high difference compared with the residual back pain group

After the surgery, the correction rate was significantly different between the residual BP group and the improved group at 30.0% vs. 47.2% (p = 0.009). Two years after the operation, correction for loss of deformity was significantly higher in the BP group than that in the improved group at 21.3% vs. 14.3%, (p = 0.045); eventually, the wedge angle was 15.7° vs. 11.9° (p = 0.042) in the two groups, and pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis (PI-LL) showed significant difference among the groups at 27.7° vs. 16.3° (p = 0.043) (Table 3).

In the multiple logistic regression model (adjusted by age, sex, angular motion, end-plate deficit, preoperative pedicle/lamina fracture, preoperative spinous process fracture, and vertebral body height ratio), based on the cutoff point for preoperative vertebral body height ratio, which was indicated by 50% or less (calculated by ROC curve) (Fig. 3), the adjusted OR for (1) residual BP was 6.57 (95% confidence interval 1.64–26.31; p = 0.007); (2) the preoperative vertebral spinous process fracture was 4.70 (95% confidence interval 0.75–29.62; p = 0.099); and (3) the preoperative vertebral body motion angle was 1.07 (95% confidence interval 0.96–1.2; p = 0.216) at 15° or higher (Table 5).

Fig. 3.

ROC curve analysis for determining the cutoff point for preoperative vertebral body height ratio

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression model (adjusted by age, sex, angular motion, and vertebral body height ratio)f residual back pain

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.124 |

| Sex | 1.70 | 0.33 | 8.73 | 0.525 |

| Preoperative spinous process fracture | 4.70 | 0.75 | 29.62 | 0.099 |

| Preoperative vertebral body height ratio (less than 50%) | 6.58 | 1.64 | 26.30 | 0.007* |

| Preoperative vertebral body motion angle (per 1°) | 1.07 | 0.96 | 1.20 | 0.216 |

*Statistically significant values

Discussion

To the best of our understanding, current research is the first to scrutinize the detailed radiographic parameters before BKP and their correlation to residual BP. The preoperative vertebral body height ratio of <50% and preoperative spinous process fracture were indicated as potential risk factors for residual BP after 2 years of treatment with BKP in patients with OVF. Besides, we showed that the preoperative wedge angle, motion angle and postoperative correction rate, and PI-LL were significantly worse in patients with residual BP than in the improved group, as there was no history of BP prior to vertebral body fracture among our study participants to show the relationship with residual BP.

Mei et al. [19] reported previously in 43 patients that kyphoplasty is an effective way to alleviate the pain of new-onset osteoporotic vertebral compressive fractures. Patients with OVFs treated with BKP could be assured of effective osseous stability and rapid pain relief with osteoporotic compression fractures [20]. A systemic review described BKP as a well-tolerated, relatively safe, and effective technique that provides short-term pain relief and improved functional outcomes, as well as superior capability for kyphotic angle and vertebral body height improvement compared with percutaneous vertebroplasty [21]. Instead, the current study revealed that 33% of patients experience residual BP 2 years after their BKP treatment.

Takahashi et al. [16] reported that patients with angular motion ≥14° were at greater risk of revision surgery after BKP. Similarly, the current study revealed that patients with preoperative high wedge angle and vertebral body motion angle were more prone to residual BP. Previously, a study of the relationship of chronic low back pain with kyphosis showed a decreased vertebral BMD measure in osteoporotic patients [22]. Also, patients having severe vertebral body fractures had severe chronic back pain (BP) and significant limitations in activities of daily living because of the severity of the deformation [23]. Our study also revealed that patients with a preoperative vertebral body height ratio <50% had residual BP 2 years after the BKP. We believe that severe vertebral body fracture may cause wall and endplate deficits, making the cement leak at the time of performing the BKP, necessitating additional treatment for maintaining vertebral body height. Based on our understanding, patients with OVF having spinous process fractures may have similar instability as that seen in patients following a reverse seat-belt injury, from severe tension force across the posterior elements of the vertebrae. There is disruption of the posterior elements of the lumbar osseous and ligamentous tissues with a longitudinal separation of the disrupted elements associated with compression of the vertebral body [24]. Our results indicate that OVF patients with a preoperative spinous process fracture had residual BP after treatment by BKP; therefore, we believe BKP alone may not be effective for stabilization in these cases.

Mei et al. [19] reported that the remaining pain after BKP is not caused by fractured vertebrae but rather by paravertebral muscles. Also, the change in the extent of the bone marrow edema at the treated level is unrelated to the relief of BP after BKP. However, the current study could indicate that the preoperative vertebral body height ratio <50% and spinous process fractures associated with OVF were potential risk factors for residual BP 2 years after the BKP. Hence, we believe that OVF patients with these risk factors may need additional surgical stabilization, such as posterior instrumentation, for the effective management of the residual BP.

Based on our findings, correction loss may be associated with a height ratio <50%. Vertebral spontaneous mobility, because of severe fracture or osteonecrosis, is associated with loss of fracture reduction after the balloon deflation, which may form a weakness of the kyphoplasty [25]. Keiichiro Iida et al. [26] identified fractured vertebral instability as a risk factor for loss of restoration after BKP. However, the presence of an adjacent fracture attenuated the correction provided by BKP, and adjacent fractures occurred more frequently in patients with severe vertebral fractures.

Besides, spinous process fracture may be associated with posterior element instability. Based on the Francis Denis three-column classification, the chance fracture is an unstable flexion-distraction spinal injury with no rotation of the fracture fragments or lateral displacement. The osteoligamentous type of chance fracture includes elements of osseous and ligamentous injuries, which could cause severe instability of posterior elements in patients having vertebral body fractures [27]. In addition, tension and distraction on the vertebrae result in a tension force across the posterior elements of the vertebrae, which disrupts the posterior elements of the lumbar spino-osseous and ligamentous tissues with a longitudinal separation of the disrupted elements [20]. Based on our understanding, the chance fracture may need additional surgical stabilization instead of the BKP.

Our study has a few limitations concerning the interpretation of our findings. First, our study’s total population is small. A prospective study with a larger sample size and longer follow-up should be performed to confirm our findings. Second, due to the retrospective design, we could not collect information about other causes of BP, such as disc degeneration, paravertebral muscle mass, nerve root compression, etc., in our patients. Third, preoperative sagittal spinopelvic parameters were not assessed in this study because patients could not tolerate severe pain.

Conclusion

BKP patients with RLBP were longitudinally reviewed for 2 years, the incidence of residual BP 2 years after BKP was 33% in the current study. Treatment schemes for OVF patients with risk factors such as preoperative vertebral height of less than 50% and spinous process fracture should be attentively assessed to provide adequate stabilization.

Acknowledgements

We thank Osaka metropolitan university’s orthopedic department and affiliated hospitals operation room staff for their contribution to the current study.

Author Contributions

ST, MH, and HN contributed to the study concept. YH, HY, TT, SO, HT, and AS contributed to data acquisition and analyses. ST and HS wrote the manuscript. HK, SD, KT, and HS contributed to data interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development grant funds were received in support of this work.

Data Availability

The data are available, upon reasonable request, from the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was taken from the patients for the data and/or imaging documents to be presented in this article.

Ethical Standard

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patients prior to study participation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cauley JA, Palermo L, Vogt M, Ensrud KE, Ewing S, Hochberg M, et al. Prevalent vertebral fractures in black women and white women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2008;23:1458–1467. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasnich RD. Vertebral fracture epidemiology. Bone. 1996;18:S179–S183. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steven R, Cummings LJMI. Epidemiology and consequences of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrar L, Jiang G, Adams J, Eastell R. Identification of vertebral fractures: An update. Osteoporosis International. 2005;16:717–728. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1880-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen ND, Jones G, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Asymptomatic vertebral deformity as a major risk factor for subsequent fractures and mortality: A long-term prospective study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20:1349–1355. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Kolta S, Briot K, Girard M. Mild prevalent and incident vertebral fractures are risk factors for new fractures. Osteoporosis International. 2007;18:1617–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay R, Pack S, Li Z. Longitudinal progression of fracture prevalence through a population of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2005;16:306–312. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian J, Yang H, Jing J, Zhao H, Ni L, Tian D, et al. The early stage adjacent disc degeneration after percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic VCFs. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallberg I, Rosenqvist AM, Kartous L, Löfman O, Wahlström O, Toss G. Health-related quality of life after osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis International. 2004;15:834–841. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rousing R, Hansen KL, Andersen MO, Jespersen SM, Thomsen K, Lauritsen JM. Twelve-months follow-up in forty-nine patients with acute/semiacute osteoporotic vertebral fractures treated conservatively or with percutaneous vertebroplasty: A clinical randomized study. Spine. 2010;35:478–482. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b71bd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renaud C. Treatment of vertebral compression fractures with the cranio-caudal expandable implant SpineJack®: Technical note and outcomes in 77 consecutive patients. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 2015;101:857–859. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zairi F, Court C, Tropiano P, Charles YP, Tonetti J, Fuentes S, et al. Minimally invasive management of thoraco-lumbar fractures: Combined percutaneous fixation and balloon kyphoplasty. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 2012;98:S105–S111. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endres S, Badura A. Shield kyphoplasty through a unipedicular approach compared to vertebroplasty and balloon kyphoplasty in osteoporotic thoracolumbar fracture: A prospective randomized study. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 2012;98:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klazen CAH, Verhaar HJJ, Lampmann LEH, Juttmann JR, Blonk MC, Jansen FH, et al. VERTOS II: Percutaneous vertebroplasty versus conservative therapy in patients with painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures; rationale, objectives and design of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2007;8:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi S, Hoshino M, Yasuda H, Terai H, Hayashi K, Tsujio T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Balloon Kyphoplasty for Patients with Acute/Subacute Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures in the Super-Aging Japanese Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:E298–305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Takahashi S, Hoshino M, Yasuda H, Hori Y, Ohyama S, Terai H, et al. Characteristic radiological findings for revision surgery after balloon kyphoplasty. Science and Reports. 2019;9:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55054-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu X, Jiang W, Chen Y, Wang Y, Ma W. Revision surgery after cement augmentation for osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 2021;107:102796. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.102796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson Y, Heyde CE, Försth P, Olerud C. Kyphoplasty in osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures—Guidelines and technical considerations. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2011;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mei X, Sun ZY, Zhou F, Luo ZP, Yang HL. Analysis of pre- and postoperative pain variation in osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture patients undergoing kyphoplasty. Medical Science Monitor. 2017;23:5994–6000. doi: 10.12659/MSM.906456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang T, Liu S, Lv X, Wu Z. Balloon kyphoplasty for acute osteoporotic compression fractures. Interventional Neuroradiology. 2010;16:65–70. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi-Ming G, Wen-Juan L, Yun-Mei H, Yin-Sheng W, Mei-Ya H, Yan-Ping L. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: A metaanalysis. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2015;49:377–387. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.154892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briggs AM, Straker LM, Burnett AF, Wark JD. Chronic low back pain is associated with reduced vertebral bone mineral measures in community-dwelling adults. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki N, Ogikubo O, Hansson T. The prognosis for pain, disability, activities of daily living and quality of life after an acute osteoporotic vertebral body fracture: Its relation to fracture level, type of fracture and grade of fracture deformation. European Spine Journal. 2009;18:77–88. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0847-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onuoha Clement E, Kelechukwu O. The biomechanics and pathogenesis of seat belt syndrome: Literature review. Nigerian Journal of Medicine. 2019;28:323. doi: 10.4103/1115-2613.278605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saliou G, Rutgers DR, Kocheida EM, Langman G, Meurin A, Deramond H, et al. Balloon-related complications and technical failures in kyphoplasty for vertebral fractures. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2010;31:175–179. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iida K, Harimaya K, Tarukado K, Tono O, Matsumoto Y, Nakashima Y. Kyphosis progression after balloon kyphoplasty compared with conservative treatment. Asian Spine Journal. 2019;13:928–935. doi: 10.31616/asj.2018.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koay J, Davis DD, Hogg JP. Chance fractures. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available, upon reasonable request, from the corresponding author.

Not applicable.