Abstract

Introduction

Risky sexual behavior exposes an individual to the risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Even though risky sexual behavior is a devastating problem in low- and middle-income countries, studies on risky sexual behavior and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries are limited. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude of risky sexual behavior and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries that help to target high-risk groups and set appropriate intervention.

Method

The appended and recent Demographic and Health Survey dataset of 10 Eastern African countries from 2012 to 2022 was used for data analysis. A total of 111,895 participants were included in this study as a weighted sample. Associated factors were determined using a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model. Significant factors in the multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression model were declared significant at p-values < 0.05. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and confidence interval (CI) were used to interpret the results.

Result

The overall magnitude of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries was 28.16% (95% CI 27.90%, 28.43%), which ranged from 3.80% in Ethiopia to 67.13% in Kenya. In the multivariable analysis, being a younger woman, being an educated woman, being tested for human immunodeficiency virus, having work, drinking alcohol, and being an urban dweller were factors that were significantly associated with higher odds of risky sexual behavior.

Conclusion

The overall magnitude of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries was high. Individual-level (being a younger woman, being an educated woman, being tested for human immunodeficiency virus, having work, and drinking alcohol) and community-level (being an urban dweller) variables were associated with higher odds of risky sexual behavior. Therefore, policymakers and other stakeholders should give special consideration to urban dwellers, educated, worker and younger women. Better to improve the healthy behavior of women by minimizing alcohol consumption and strengthening HIV testing and counseling services to reduce the magnitude of risky sexual behavior.

Keywords: Women, Sexual behavior, Eastern Africa, Risky sex

Introduction

Risky sexual behavior is defined as sexual activities that expose an individual to the risk of having sexual and reproductive health problems [1]. It includes engaging in unprotected sexual behavior, having sex at a young age, having sex with multiple sexual partners, and having sex while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection (STI) is elevated in individuals with RSB. Adverse outcomes such as infertility and ectopic pregnancies are also linked to STIs. Cervical cancer is also brought on by the human papillomavirus, which also causes genital warts. Similarly, the chance of HIV transmission rises due to the presence of STIs. To prevent the harmful effects of unsafe sex (HIV, unintended pregnancy, incurable STI, etc.), creating awareness of responsible sex behavior is critical [2].

Despite the social, economic, demographic, and health benefits of safe sex and consistent condom use is important in promoting women’s health and well-being, the findings of the previous studies highlighted that, the prevalence of risky sexual behavior, 17.2–24.7% in Ethiopia [3, 4], 66.9% in Ghana [5], 28.7% in Rwanda [6], 69.5% in Bangkok [2]. The prior studies revealed that age, educational status, working status, age at first sexual intercourse, drinking alcohol, wealth index, marital status, residence, comprehensive knowledge about HIV/ADIS, tested for HIV, and ever heard about sexually transmitted infections (STI) were factors significantly associated with risky sexual behavior [2–4, 6–12].

Due to the negative consequences of risky sexual behavior on women’s health, there must be an intervention to reduce the magnitude of risky sexual behavior and the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Even though risky sexual behavior is a devastating problem in low- and middle-income countries, studies on risky sexual behavior and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries are limited. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the magnitude of risky sexual behavior and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries that help to target high-risk groups and set appropriate interventions.

Methods

Data source, study setting, period, and design

The study utilized the appended and the recent demographic and health survey dataset from 10 Eastern African countries conducted from 2012 to 2022. DHS is a community-based cross-sectional study conducted every five years to examine health and health-related indicators.

Study population, sampling technique, and analysis

The recent DHS data of 10 Eastern African countries (Ethiopia, Comoros, Burundi, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Zambia) was downloaded from the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) program website and appended to have a single data set. DHS data exhibit nested dependencies, where individuals are nested within communities. It employs stratified two-stage cluster sampling. Clusters (communities) are sampled, and within each cluster, households and individuals are further selected. The cleaned and recorded data were analyzed using STATA (version 14) statistical software. The women’s sample weight (v005/1,000,000) was applied to address under or over-sampling. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was tested to check multi-collinearity. To determine factors associated with the outcome variable (risky sexual behavior) multi-level mixed-effect logistic regression was applied. We conducted a likelihood ratio test, comparing ordinary logistic regression to multilevel logistic regression. The results affirmed a significant improvement when using multilevel models, reinforcing their suitability. Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regression follows four models: null model (outcome variable only), model I (only individual-level variables), model II (only community-level variables), and model III (both individual and community-level variables). The model without independent variables (Null model) was used to check the variability of risky sexual behavior across the cluster. The association of individual-level variables with the outcome variable (Model I) and the association of community-level variables with the outcome variable (Model II) were assessed. In the final model (Model III), the association of both individual and community variables was fitted with the outcome variable (risky sexual behavior). Variables with a p-value of < 0.25, were candidates for the multivariable analysis in univariate analysis at 95% confidence intervals and variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 were considered as significantly associated with the outcome variable in the final analysis. The weighted total sample participants for the study were 111,895 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample size for risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries

| Country | Year of survey | Weighted sample(n) | Weighted sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi | 2016/17 | 10,224 | 9.14 |

| Comoros | 2012 | 3,261 | 2.91 |

| Ethiopia | 2016 | 10,301 | 9.21 |

| Kenya | 2022 | 27,703 | 24.76 |

| Mali | 2018 | 8,600 | 7.69 |

| Rwanda | 2019/20 | 8,613 | 7.7 |

| Tanzania | 2022 | 12,011 | 10.73 |

| Uganda | 2016 | 13,682 | 12.23 |

| Zambia | 2018 | 10,297 | 9.2 |

| Zimbabwe | 2015 | 7,204 | 6.44 |

| Total sample size | 111,895 |

Study variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable of this study was risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women derived from a series of questions from the individual records. The woman was considered to have risky sexual behavior if she experienced either or both of the risky sexual behaviors, (I) had multiple sexual partners, and (II) had sexual intercourse other than a spouse or live-in partner. Even though Condon’s use during sex is one of the most effective methods to protect oneself from sexually transmitted infections including HIV [13], the authors of this study didn’t include it to determine the outcome. Because the DHS data incorporate condom use in the last sexual intercourse only. Thus, the consistency of condom utilization during sexual intercourse is unknown.

Independent variables

The independent variables of this study were individual-level variables, age (15–19 years, 20–35 years, and 36–49 years), educational level (no education, primary, secondary, and higher level), having media exposure (yes or no), household wealth index (poor, middle and rich), working status (working or not working), tested for HIV (yes, no), drinking alcohol (yes or no) have comprehensive knowledge about HIV/ADIS), age at first sex (< 18 years or ≥ 18 years), and community level variables, residence (urban or rural), community level media exposure (low or high), community level women illiteracy (low or high), community level poverty (low or high). The community media exposure, community poverty, and community illiteracy levels were aggregated from the individual level variables; media exposure (derived from combining whether a respondent reads a newspaper, watches television, and listens to radio and coded as yes (if the respondent had been exposed to at least for one of these media) an no (otherwise), house wealth status (wealth index), and maternal educational status. Regarding the analysis of the aggregation, first, the individual variables were re-categorized and cross-tabulations were done with the cluster variable using STATA version 14. Then, the proportion of media exposure, poverty, and illiteracy was computed using Microsoft Excel 2013. Next, the proportions from Excel were imported to STATA and combined with the original set of the variables in the STATA. Finally, we have categorized the proportion of media exposure, poverty, and illiteracy into levels.

Result

Individual and community-level characteristics of the study participants

More than half (60.49%) of the participants were in the age category of 20–35 years. More than two-thirds of (72.51%) respondents had media exposure. More than half (60.21%) of the participants in the study had work. The majority (78.99%) of the respondents were tested for HIV. The majority (95.36%) of women’s ever heard about STIs. More than two-thirds (69.68%) of the participants were rural dwellers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Individual and community-level characteristics of the study participants

| Individual level variables | Weighted frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–19 years | 11,042 | 9.87 |

| 20–35 years | 67,686 | 60.49 | |

| 36–49 years | 33,166 | 29.64 | |

| Educational level | No education | 25,363 | 22.67 |

| Primary | 46,480 | 41.54 | |

| Secondary | 30,638 | 27.38 | |

| Higher | 9414 | 8.41 | |

| Marital status | Single | 14,271 | 12.75 |

| Married | 72,097 | 64.43 | |

| Ever married | 25,527 | 22.81 | |

| Media exposure | No | 30,755 | 27.49 |

| Yes | 81,140 | 72.51 | |

| Household wealth | Poor | 40,670 | 36.35 |

| Middle | 21,567 | 19.27 | |

| Rich | 49,658 | 44.38 | |

| Currently working | No | 44,520 | 39.79 |

| Yes | 67,375 | 60.21 | |

| Tested for HIV | No | 20,268 | 21.01 |

| Yes | 76,187 | 78.99 | |

| Drinking alcohol | No | 13,645 | 66.48 |

| Yes | 6880 | 33.52 | |

| Know HIV/ADIS | No | 65,077 | 93.64 |

| Yes | 4422 | 6.36 | |

| Ever heard about STI | No | 4477 | 4.64 |

| Yes | 91,978 | 95.36 | |

| Residence | Urban | 33,927 | 30.32 |

| Rural | 77,967 | 69.68 | |

| Community-level media exposure | Low | 60,640 | 54.19 |

| High | 51,255 | 45.81 | |

| Community-level women illiteracy | Low | 61,484 | 54.95 |

| High | 50,411 | 45.05 | |

| Community level poverty | Low | 55,100 | 49.24 |

| High | 56,795 | 50.76 | |

Prevalence of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in eastern African countries

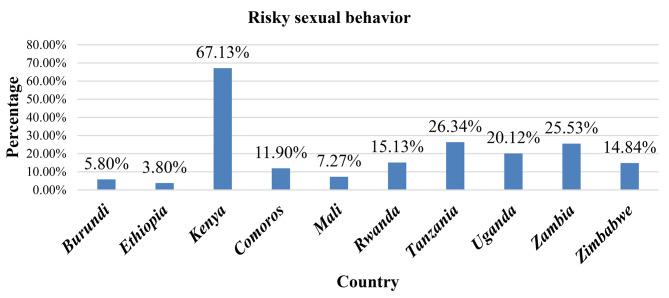

The overall magnitude of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries was 28.16% (95% CI 27.90%, 28.43%), which ranged from 3.80% in Ethiopia to 67.13% in Kenya (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries

Types of risky sexual behavior among Reproductive-age women in eastern African countries

From the total participants of the study, 17,994 (16.08%), and 30,496 (27.25%) of the women reported that they had two or more sexual partners, and had sexual intercourse other than a spouse or live-in partner (Table 3).

Table 3.

Types of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries

| Item | Weighted frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had two or more sexual partners | No | 93,901 | 83.92 |

| Yes | 17,994 | 16.08 | |

| Had sexual intercourse other than a spouse or live-in partner | No | 81,398 | 72.75 |

| Yes | 30,496 | 27.25 | |

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in eastern African countries

In the final fitted model of multivariable logistic regression being younger age, being educated, drinking alcohol, not being tested for HIV, being a worker, and being an urban dweller were factors significantly associated with higher odds of risky sexual behavior (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis of individual-level and community-level factors associated with risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries

| Parameter | Null model | Model I AOR (95% CI) |

Model II AOR (95% CI) |

Model III AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 15–19 years | 12.14 (9.29, 15.85) | 13.06 (9.98, 17.09)* | ||

| 20–35 years | 1.76 (1.44, 2.15) | 1.81 (1.48, 2.21)* | ||

| 36–49 years (ref.) | ||||

| Age at first sex | ||||

| < 18 years | 1.23 (1.05, 1.45) | 1.17 (1.00, 1.38) | ||

| ≥ 18 years (ref.) | ||||

| Level of education | ||||

| No education (ref.) | ||||

| Primary | 1.45 (1.20, 1.76) | 1.36 (1.12, 1.65)* | ||

| Secondary | 4.91 (3.88, 6.21) | 3.86 (3.03, 4.92)* | ||

| Higher | 7.11 (5.12, 9.88) | 4.13 (2.93, 5.83)* | ||

| Currently working | ||||

| No (ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.62 (1.36, 1.91) | 1.73 (1.46, 2.06)* | ||

| Household wealth | ||||

| Poor | 0.85 (0.70, 1.05) | 1.21 (0.96, 1.51) | ||

| Middle | 0.71 (0.56, 0.90) | 1.03 (0.80, 1.33) | ||

| Rich (ref.) | ||||

| Drink alcohol | ||||

| No (ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.63 (1.38, 1.92) | 1.75 (1.48, 2.06)* | ||

| Knowledge about HIV/ADIS | ||||

| No (ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.22 (0.87, 1.71) | 1.25 (0.89, 1.76) | ||

| Have media exposure | ||||

| No (ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.09 (0.92, 1.29) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21) | ||

| Tested for HIV | ||||

| No (ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.33 (1.09, 1.62) | 1.43 (1.17, 1.74)* | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Rural (ref.) | ||||

| Urban | 2.16 (2.08, 2.23) | 3.73 (2.89, 4.80) * | ||

| Community-level media exposure | ||||

| Low (ref.) | ||||

| High | 2.60 (2.26, 2.98) | 1.01 (0.78, 1.30) | ||

| Community-level women illiteracy | ||||

| Low (ref.) | ||||

| High | 2.36 (2.07, 2.71) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.36) | ||

| Community level poverty | ||||

| Low (ref.) | ||||

| High | 0.63 (0.57, 0.70) | 0.94 (0.74, 1.18) | ||

| Variance | 1.392 | 0.605 | 0.849 | 0.614 |

| ICC | 29.73 | 15.53 | 20.51 | 15.73 |

| PCV | Reference | 56.54 | 39.01 | 55.89 |

| Deviance | 127,666.856 | 6405.148 | 125,188.016 | 6293.009 |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ICC, intra-class correlation coefficient; PCV, proportional change in variance; (ref.), reference; *p ≤ 0.05 (significantly associated)

The odds of risky sexual behavior were 13.06 (AOR = 13.06, 95% CI: 9.98, 17.09) and 1.81 (AOR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.48, 2.21) times higher among 15 to 19 years and 20 to 35 years old women as compared with women aged 36 to 49 years respectively. The likelihood of risky sexual behavior was 1.36 (AOR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.65), 3.86 (AOR = 3.86, 95% CI: 3.03, 4.92), and 4.13 (AOR = 4.13, 95% CI: 2.93, 5.83) times higher among women who had primary, secondary, and higher educational level as compared with those women who had no education respectively. Risky sexual behavior was 1.73 (AOR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.46, 2.06) times higher among worker women as compared with their counterparts. The odds of risky sexual behavior were 1.75 (AOR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.48, 2.06) times higher among women who drank alcohol as compared with women who didn’t drink alcohol. The likelihood of risky sexual behavior was 1.43 (AOR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.74) times higher among women who didn’t test for HIV as compared with women tested for HIV. Risky sexual behavior was 3.73 (AOR = 3.73, 95% CI: 2.89, 4.80) time higher among urban dwellers as compared with rural dwellers. There was about 29.73% variability in risky sexual behavior due to the difference between communities/clusters. The final model (model III), attributed approximately 55.89% of the variation in the likelihood of risky sexual behavior to both individual and community-level variables. The lowest deviance, which was 6293.009 in model III revealed that model III was the best fit for the data.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess risky sexual behavior and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries. The overall magnitude of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries was 28.16% (95% CI 27.90%, 28.43%), which ranged from 3.80% in Ethiopia to 67.13% in Kenya. It implies that risky sexual behavior is still a great concern in Eastern African countries. Being younger, being educated, having work, drinking alcohol, being tested for HIV, and being an urban dweller were factors associated with the higher odds of risky sexual behavior.

The odds of risky sexual behavior were higher among women who drink alcohol as compared with women who never drink alcohol. The finding of this study are consistent with the prior studies [14–19]. Alcohol plays a great role in negative behaviors. Excessive drinking can lower inhibitions, impair a person’s judgment, and increase the risk of aggressive behaviors [20]. Drinking alcohol resulted in conflict between an individual’s desire and their inhibitions, which in turn failed to inhibit inappropriate or risky behaviors [21]. It could be because women who drink alcohol may not be fully conscious which in turn alters their decision in whether risky or responsible sexual activity. Furthermore, it could be because women intentionally use alcohol for their sexual interest which in turn results in risky sexual practice.

The current finding revealed that risky sexual behavior was higher among women who had work compared with their counterparts. This finding is supported by the previous study [12, 22]. It might be because women who had work exhibit higher levels of independence and tend to go against certain societal expectations, which in turn can cause having multiple sexual partners and committing sexual intercourse other than their spouse or live-in partner.

The age of women is another significant factor associated with risky sexual behavior. The odds of risky sexual behavior were significantly higher among younger women as compared with older women. This finding is supported by the prior study [12]. Compared to older women, younger women were better educated, made their sexual debuts earlier, and were more likely to engage in high-risk and transactional sex [11]. Furthermore, it could be due to variations in sexual desire between younger and older women. Compared to older women, younger women experienced more frequent and intense sexual desires. Additionally, they were more likely to have sex earlier in a relationship and had more sex overall [23].

The odds of risky sexual behavior were higher among women who were educated as compared with those women who had no education. It could be due to variations in their residence and age between educated and non-educated women. There is a significant education gap between urban and rural areas [24]. However, additional investigation is required to gain a deeper comprehension of the complex correlation between education and risky sexual behaviors among reproductive-age women.

Contrary to the prior study [25], in this study, the likelihood of risky sexual behavior was higher among women not tested for HIV as compared with women tested for HIV. It could be because those women who have tested for HIV have a chance of getting information from health professionals regarding the negative effects of risky sexual behavior and the burden of sexually transmitted infections. Thus, women tested for HIV may not participate in risky sexual activities.

In addition, contrary to the prior studies [26, 27], the odds of risky sexual behavior were higher among urban dweller women as compared to rural dwellers. It could be because, urban women frequently use social media more likely to share sexually explicit texts, images, and videos with a sexual partner, which in turn leads to risky sexual behavior.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The data used for the study was nationally representative with multi-country and appropriate statistical analysis which is multilevel analysis. Hence policymakers and the international community can use it as evidence to undertake necessary measures. However, the study also has limitations, important factors that could have a big impact on risky sexual behavior, like beliefs, risky sexual behavior, and social norms, are not included in the dataset. Additionally, due to the sensitive nature of risky sexual behavior, a social desirability bias and under-report may have been present in the women’s verbal responses. These will hinder our findings from having the intended impact, so further studies should be carried out to explore women’s risky sexual behavior.

Conclusion

The overall magnitude of risky sexual behavior among reproductive-age women in Eastern African countries was high. Individual-level (being a younger woman, being an educated woman, being tested for human immunodeficiency virus, having work, and drinking alcohol) and community-level (being an urban dweller) variables were associated with higher odds of risky sexual behavior. Therefore, policymakers and other stakeholders should give special consideration to urban dwellers, educated, worker and younger women. Better to improve the healthy behavior of women by minimizing alcohol consumption and strengthening HIV testing and counseling services to reduce the magnitude of risky sexual behavior. Furthermore, the authors of the study recommend further investigation into the reason why being educated and working women increases the risk of having risky sexual behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors of the study are grateful to DHS programs for letting us to use the relevant data.

Author contributions

BSW: involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing original draft, review & editing; AFZ: involved in investigation, and methodology; TTT: involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis; EGM: involved in data curation, and formal analysis.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available publicly online at (https://www.dhsprogram.com).

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was based on an analysis of existing survey datasets in the public domain that are freely available online with all the identifier information anonymized, no ethical approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chawla N, Sarkar S. Defining high-risk sexual behavior in the context of substance use. J Psychosexual Health. 2019;1(1):26–31. doi: 10.1177/2631831818822015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thepthien B-o. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among sexually-experienced adolescents in Bangkok, Thailand: findings from a school web-based survey. Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srahbzu M, Tirfeneh E. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among adolescents aged 15–19 years at governmental high schools in Aksum Town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2019: an institution-based, cross-sectional study. BioMed research international. 2020;2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Azeze GA, Gebeyehu NA, Wassie AY, Mokonnon TM. Factors associated with risky sexual behaviour among secondary and preparatory students in Wolaita Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia; Institution based cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21(4):1830–41. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v21i4.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson F, Haile ZT. Association between educational attainment and risky sexual behaviour among Ghanaian female youth. Afr Health Sci. 2023;23(1):301–8. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v23i1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawuki J, Nuwabaine L, Namulema A, Asiimwe JB, Sserwanja Q, Gatasi G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus among sexually active women in Rwanda: a nationwide survey. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):2222. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-17148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asresie MB, Worede DT. Factors Associated with Risky Sexual Behavior Among Reproductive-Age Men in Ethiopia: Evidence from Ethiopian Demography and Health Survey 2016. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care. 2023:549 – 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sicard S, Mayet A, Duron S, Richard J-B, Beck F, Meynard J-B, et al. Factor associated with risky sexual behaviors among the French general population. J Public Health. 2017;39(3):523–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekletsadik EA, Ayisa AA, Mekonen EG, Workneh BS, Ali MS. Determinants of risky sexual behaviour among undergraduate students at the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150:e2. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baru A, Adeoye IA, Adekunle AO. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among sexually-active unmarried young female internal migrants working in Burayu Town, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0240695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faini D, Hanson C, Baisley K, Kapiga S, Hayes R. Sexual behaviour, changes in sexual behaviour and associated factors among women at high risk of HIV participating in feasibility studies for prevention trials in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darteh EKM, Dickson KS, Amu H. Understanding the socio-demographic factors surrounding young peoples’ risky sexual behaviour in Ghana and Kenya. J Community Health. 2020;45(1):141–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis). [10 July 2023].

- 14.Cho H-S, Yang Y. Relationship between Alcohol Consumption and Risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults: a Meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605669. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agius P, Taft A, Hemphill S, Toumbourou J, McMorris B. Excessive alcohol use and its association with risky sexual behaviour: a cross-sectional analysis of data from victorian secondary school students. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(1):76–82. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izutsu T, Tsutsumi A, Matsumoto T. Association between sexual risk behaviors and drug and alcohol use among young people with delinquent behaviors. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi = Japanese J Alcohol Stud Drug Depend. 2009;44(5):547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin JA, Umstattd MR, Usdan SL. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among collegiate women: a review of research on alcohol myopia theory. J Am Coll Health. 2010;58(6):523–32. doi: 10.1080/07448481003621718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Supplement. 2002;14:101–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kassa GM, Degu G, Yitayew M, Misganaw W, Muche M, Demelash T et al. Risky sexual behaviors and associated factors among Jiga high school and preparatory school students, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. International scholarly research notices. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Alcohol Rehab Guid. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj29O7-v6KDAxUJB8AKHb6wBSEQFnoECAkQAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.alcoholrehabguide.org%2Falcohol%2Fcrimes%2F&usg=AOvVaw2REcuYwjYIdwNKke_8QzhA&opi=89978449.

- 21.Dermen KH, Cooper ML. Inhibition conflict and alcohol expectancy as moderators of alcohol’s relationship to condom use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8(2):198. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.8.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich LM, Kim S-B. Employment and the sexual and reproductive behavior of female adolescents. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2002:127 – 34. [PubMed]

- 23.Guid HaS. How Sex Drive Changes Through the Years. https://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/ss/slideshow-sex-drive-changes-age. [July 18, 2023].

- 24.Wood RM. A review of Education differences in Urban and Rural areas. Int Res J Educational Res. 2023;14(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.George G, Beckett S, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Govender K, Kharsany AB. Impact of HIV testing and treatment services on risky sexual behaviour in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Therapy. 2019;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12981-019-0237-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voeten HA, Egesah OB, Habbema JDF. Sexual behavior is more risky in rural than in urban areas among young women in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004:481–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Thompson EL, Mahony H, Noble C, Wang W, Ziemba R, Malmi M, et al. Rural and urban differences in sexual behaviors among adolescents in Florida. J Community Health. 2018;43:268–72. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available publicly online at (https://www.dhsprogram.com).