Abstract

Background

Traditional medical practices have been used to maintain animal health for millennia and have been passed down orally from generation to generation. In Ethiopia also, plants are the primary means by which the indigenous people in remote areas treat the illnesses of their animals. The present study was therefore, carried out to document the type and distribution of medicinal plants of the county.

Methods

To collect ethnobotanical information, a total of 205 informants (133 men and 72 women) were selected. Among these 121 traditional medicine practitioners, while the remaining 84 were selected through a systematic random sampling method. Ethnobotanical data were collected between January 2023 and August 2023 through semi-structured interviews, participant observation, guided filed walks and focus group discussions. Using descriptive statistics, the ethnobotanical data were analyzed for the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) and Fidelity Level (FL) values, preference, and direct matrix rankings. SPSS 26.0 and PAST 4.11 software were used in data analysis.

Results

Totally, 78 ethnoveterinary medicinal plants distributed in 36 families were identified in the study area. Asteraceae was the dominant family with 9 species (14%), followed by Euphorbiaceae with 8 species (12%). Herbs 42(56%), wild collected 62 (66%), and leaf part (52%) made the highest share of the plant species. Hordeum vulgare L. had the highest fidelity level (FL = 98%) for treating bone fractures. Blackleg, bloat, and endoparsistes each had the highest values of the consensus factor among the informants (ICF = 1). According to preference ranking, Withania somnifera was the most potent remedy for treating blackleg. Knowledge of medicinal plants was shared through storytelling within families.

Conclusion

In the study area, there is broad access to traditional medicinal plants that can treat ailments in animals. Conservation efforts should be prioritized to protect medicinal plants from threats such as agricultural expansion, drought, and development. Further research should be conducted to explore the potential of different medicinal plants for treating common livestock ailments.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12917-024-04019-6.

Keywords: Animal diseases, Ethno-veterinary, Medicinal plants, Traditional medicine

Background

Livestock production is vital to developing nations' rural economies, especially in rural communities [1]. Food security and poverty reduction are two benefits it provides, along with support for many cultural rituals [2]. Animals fulfill a number of social roles and are a major source of food, money, and nutrient-rich dung that may rebuild soil [3, 4]. However, their likelihood of catching other diseases is usually higher. Diseases that affect livestock raising to differing degrees may put different kinds of animals at risk [5–7]. Ethnoveterinary medicine (EVM) is the application of a range of belief-based systems and knowledge, conventional wisdom, experience, techniques, knowledge of medicinal plants, technologies, and teaching to the care of livestock in order to maintain animal health [8]. However, public veterinary services are only available in large cities and some selected area in terms of economic importance [9]. So, for farmers and livestock herders in remote locations, EVM provides a viable replacement for western veterinary procedures. According to McGaw and Eloff et al. [10], plants contain a variety of phytochemicals and investigations in EVM are necessary. Wendimu et al. [11] claimed these plants can be the leading candidates for the creation of medications and other active items that are useful for controlling human and livestock health ailments. As a nation, Ethiopia continues to rely heavily on traditional medicine, and medicinal herbs in particular, to address problems with livestock health [11, 12]. Given that the country is listed in two biodiversity hotspots and has a rapid population growth and the continued loss of biodiversity highlights the necessity of researching plant resources, especially local species that are considered endemic or indigenous [13, 14].

Despite some efforts [12, 15–19], the lack of documenting and dissemination of scientific data on the use of ethnoveterinary medicine among various ethnic groups worldwide represents a crucial gap in the body of material currently available. The majority of diagnostic and treatment expertise has historically been passed down orally and through mentoring; written records have been used sparingly [20–22]. The research and documentation of traditional ethnoveterinary medicine need to be prioritized more and more, as there is a possibility that indigenous knowledge levels could be lost due to many circumstances, including urbanization, migration, and technology [11, 23–27]. The importance of this corpus of information is best expressed by the African saying "When an erudite old man dies, the whole library disappears" [28].

People in the Omo-Gibe and Rift Valley Basins in southern Ethiopia's Wolaita Zone use traditional diagnostic techniques and plant-based treatments to treat livestock ailments. This research investigated ethnoveterinary practices in this region, focusing on traditional diagnostic tools and plant-based treatments for livestock disease, with the goal of preserving indigenous knowledge and improving animal health.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

Wolaita is the name of one of Ethiopia's zonal administrations. The Wolaita people, whose ancestral home is in the zone, gave it their name. Wolaita is bordered by Gamo Gofa on the south, the Omo River on the west, which separates it from Dawro, Kembata, Tembaro on the northwest, Hadiya on the north, the Oromia Region on the northeast, the Bilate River on the east, which separates it from Sidama Region, and Lake Abaya on the south-east, which separates it from Oromia Region. Sodo serves as the administrative hub of Wolaita. Wolaita Zone is located in one of Ethiopia's Southern Regional states. With a surface area of 4383.7 km2, the zone has a population above 5.3 million [29].

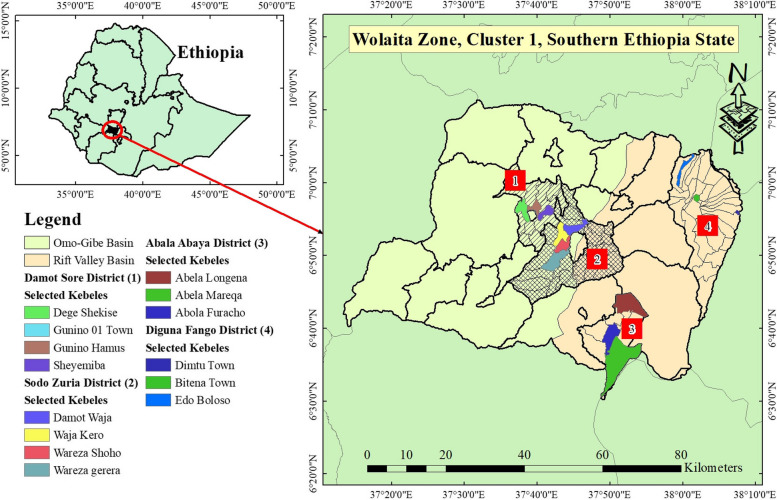

The study was carried out in four districts, such as Damot Sore District and Sodo Zuria District in Omo-Gibe Basin Side and Diguna Fango District and Abala Abaya District in Rift Valley Basin Side of Wolaita Zone (Fig. 1). The maximum monthly temperatures are 17.7°C in July and 22.1°C in February and March. The average annual temperature is 19.9°C [30–32]. The region receives an average of 1,350 mm (53 in) of rainfall annually, according to Bagnara [30].

Fig. 1.

The study area map, Wolaita Zone, Cluster 1, South Ethiopia Regional State (Source: AcrMap10.4.1 by Abenezer Wendimu)

Study design

In a cross-sectional study approach was used to collect ethnoveterinary information from traditional healers in the Wolaita zone between January 2023 and August 2023. The primary study parameters were indigenous ethnobotanical knowledge, resources, and their applications.

Sampling procedure and informant selection

The key informants were chosen by using purposive sampling method. Following the discovery of a few practioners/healers utilizing the sources mentioned above, fruitful initial interactions were made and further ethnopractitioners were found using their existing networks. This method is frequently employed in indigenous knowledge studies to gather data from unexplored communities that are challenging for academics to reach. With the help of the purposive sample technique, it was ensured that only the key respondents with the necessary traits and levels of understanding of the traditional animal healthcare system were selected [32]. Two Hundred Five (205) individuals were chosen to take part in the study, with 65% of them being men and 35% being women while the remaining 84 were selected through a systematic random sampling method. Participants included were farmers, livestock, herders, and individuals with indigenous knowledge, and their ages ranged from 18 to 95. From the total population, 121 were key informants. The selection method for the study's target or key respondents was depending on the target individual's background experience in contemporary ethnoveterinary medical practices. Ethnopractitioners who give the local livestock vital medical care were designated as the target or key respondents.

Data collection

From Damot Sore District, in Rift Valley Basin side, the kebeles (wards; small administrative unit of the district) used to conduct the research were Dege Shekise, Gunino 01, Gunino Hamus, and Sheyemiba kebeles while in Sodo Zuria District, Damot Waja, Waja Kero, Wareza Shoho, and Wareza Gerera kebeles. In Rift Valley Basin side, Abela Longena, Abela Mareqa and Abela Gurcho were kebeles selected from Abala Abaya District and Dimtu Town, Bitena Town and Edo Boloso were kebeles selected from Diguna Fango District.

An open interview questions was created for data collection and given to the participants. The interview was split into two segments. Basic data, including the respondent's name, age, gender, place of birth, and level of education, were gathered in the first section. Different items made up the open interview in the second section including the names of plants, a list of ailments/diseases treated with the claimed MPs, plant parts utilized, mode of preparation, plant habitat, source of information acquisition, etc. The interviewees were requested to go with us to the neighboring mountains, farms, or grasslands to identify the medicinal plants they used and to offer local colloquial names in Wolaita dialect, in addition to written records and audio recordings, which were taken with another party's permission. Individual interview data were cross-checked with additional participants' commentaries from the same villages in order to gather trustworthy information about the study region [33].

Questionnaire distribution

The interviewer assisted each of the respondents in completing a well-structured questionnaire (S1 Appendix). The survey consisted of 18 questions covering: village, respondent's information, approval, ethnoveterinary medicine details, animal species treated, remedy identification, care, compensation, knowledge exchange, livestock illnesses treated, plants used, plant state, plant variables, plant actions, challenges, respondent's views, recommendations, and direct observation by the interviewer.

The interviewer was required to be accompanied by a senior relative or friend, as well as a member of the local government from the office of the area subchief who was acquainted with the interviewee, whenever a questionnaire was delivered to the subject. As the interviewer completed the questionnaire, these two individuals actively and productively engaged the interviewee in conversation. This combination produced a highly beneficial interaction that created a favorable setting for the successful completion of research using Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) and Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA). Because it lessened the following causes of bias, this technique was deemed to be very effective and reliable:—(1) modeling bias, or projecting the interviewer's viewpoint onto the subjects under study, (2) strategic bias, or the subject's expectation of benefits, (3) relationships between senior relatives, administrator representatives, and interviewees that are familiar with one another may lead to rote responses and outsider bias while lessening resistance to questioning and (4), decreasing the influence of "key personas" [25]. Due to these preconceived notions, questionnaires would be filled out incorrectly and the data collected would not be properly documented or analyzed [12, 15].

Plant specimen collection and identification

After the key respondents were personally interviewed, the indicated specimens of plants were identified and collected during numerous field trips. The specimens were collected, and each plant species was verified using The World Flora Online [34] and The Plant List [35] before botanical identification was completed in a field laboratory using biological keys. They were photographed and sampled for identification at the National Herbarium of Ethiopia. Formal identification of the plant materials were carried out by Abenezer Wendimu (the first author) and Zekarias Demisseie (a botanist) assisted the identification.

Data analysis

The collected data on medicinal plants, their uses, and related knowledge were recorded and coded on Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics like percentages and frequency tables were employed to analyze the data using SPSS version 20.Remarks about the medical worth of plants, their growing forms, modes of preparation, how they are used, routes of adminstration, dose, and what components of the plants they are made of were all part of the interview session. Using the t-test at a 95% confidence level, it was enabled to us to compare the traditional medical dynamics about the use of plants for medicinal purposes by men and women, young and old, illiterate and educated, key and general informants.

According to Chekole et al. [36], quantitative ethnobotanical methods like Informant Consus Factor (ICF) values were calculated to determine the most common livestock illnesses categories reported across the communities and to identify potentially effective medicinal plant species in respective disease categories.

where; nur (category's total number of citations) was calculated by subtracting the total number of species utilized (nt) and dividing the result by the total number of citations in each category, minus one.

Furthermore, Fidelity Level (FL) values were computed as follows: FL (%) = Ip/Iu × 100. Where Iu stands for all informants who indicated using a plant to treat any sickness, while Ip indicates how many respondents overall suggested utilizing a plant to treat a particular condition. Preference ranking was developed to determine the effectiveness of particular medicinal plants against the most prevalent diseases in the research district.

Results

Diversity of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants in the district

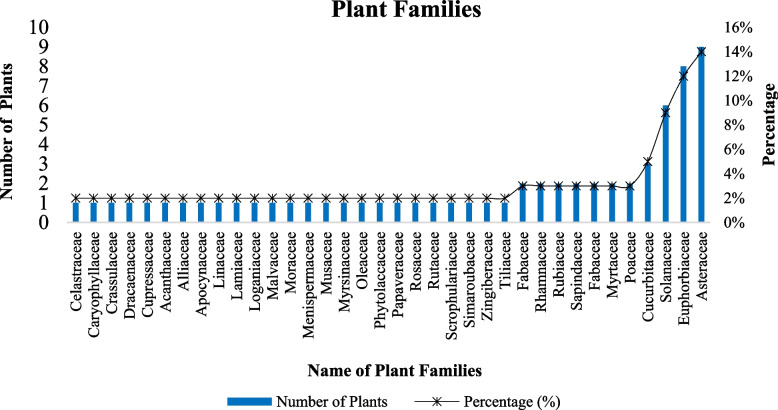

The research districts contained 78 different species of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants, which are belongs into 36 families (Table 1). Asteraceae was a dominant family with 9(14%) species followed by Euphorbiaceae 8(12%), Solanaceae 6(9%), and Cucurbitaceae 3(5%) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The diversity of medical plants used in traditional ethno-veterinary practices, the methods used in their production and application to treat typical livestock maladies in Wolaita, South Ethiopia

| Family Names | Scientific Name and Voucher Code | English and Local Names (FL) | Growth Form | Collection habits | Used Part | Ailments treated | Remedy Preparation and dosage | Administration Route | Freq | Used by | FL (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T., (SW 35) | Justicia (E), Olomuwa (W), Sensel, Simiza, Sansal and Dumoga (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Rabies | Crushing the leaves of the plant and adding in to a hot water. Afterwards, one glass of preparation is given per day for three consecutive days | Oral | By weekly | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 17% |

| Circling disease | The crushed leaves are mixed with cold water, filtered after 30–40 min and administrated orally | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Ovine and caprine | 54% | ||||||

| Alliaceae | Allium sativum L., (BN077) | Garlic (E), Nechi shenkurt (A), Shunkurtiya (W) | Herb | Cultivated | Bulb | General illness | When in pain, a combination of crushed J. procera leaf and A. sativum bulb is administered. For sheep and goats, one liter of the mixture is administered; for cows and oxen, two liters | Oral | Recovery | Bovine | 13% |

| Aloaceae | Aloe spp. (MNWP-05) | Aloe (E), Wende rate (A), Atuma godarre utta (W) | Herb | Wild | Sap | New castle | The fresh stem of the plant is crushed and squeezed. Then resulting sap is given until recovery | Oral | Recovery | Galine | 29% |

| Aloaceae | Aloe pulcherrima Gilbert & Sebsebe, (MW-002) | Aloe (E), Sete rate (A), Macca godarre utta (W) | Shrub | Wild | Sap | New castle | The fresh stem of the plant is crushed and squeezed. Then resulting sap is given until recovery | Oral | Recovery | Galine | 45% |

| Apiaceae | Anethum graveolens L., (MB-53) | Dill (E), Insilaalee (A), Wosoluwa (W) | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | Bloat | Crushed leaf mixed with water and filtered. The, the prepared mixture is given orally to drinking | Oral | Once a day | Bovine | 21% |

| Apiaceae | Diplolophium africanum Turcz, (GC041) | Yeferse zenge (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Taenia | Crushed leaf mixed with water and filtered. The, the prepared mixture is given orally to drinking | Oral | Once | Bovine | 19% |

| Apocynaceae | Carissa spinarum L., (MB-38) | Agamsa (A) | Shrub | Root | Respiratory allergies | Crushing and adding water | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 17% | |

| Asteraceae | Acmella caulirhiza Del., (SW 15) | Acmella (E), Aydaamiya (W), Yemdir berbere (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Leech | When the plant's fresh leaves are pinched, the fragrance causes gasping and sneezing | Nasal | Once | Bovine | 68% |

| Seed | Internal parasite | The dry ground seed is mixed with milk in 0.5L bottle | Oral (drinking) | Once | Feline | 29% | |||||

| Leave | Newcastle | The fresh plant leaves were crushed and soaked with water in open dish for an hours. The sauce is then filtered and only the liquid part is collected in 1L bottle | Oral | Twice | Poultry | 31% | |||||

| Asteraceae | Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd., (SW 17) | African Wormwood (E), Chekugne (A), Cuqqunaiya (W) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Diarrhea | Crushed fresh plant leaves are blended for five minutes with hot water. After filtration, the produce is then administered orally. The dosage is 1 L each day until the recovery | Oral | Once | Bovine | 74% |

| Asteraceae | Artemisia spp., (SW 17) | Naatraa (W) | Herb | Cultivated | Stem, Leave | Bloating | When in pain, this plant's fresh shoot or leave and an E. globulus leave are crushed together and given in doses of one liter for cows and oxen and half a liter for sheep and goats | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, caprine, ovine | 88% |

| Asteraceae | Conyza spp. | Horseweed (E), Asfa (A), Chakga (W) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Internal parasite | Crushed plant material and water are combined with the plant's young leaves. Then, one liter of the concoction is administered once daily in the morning | Oral (drinking) | Twice | Bovine | 47% |

| Asteraceae | Echinops spp., (SW 25) | Glandular globe-thistle (E), Boorisaa (W), Kebericho (A) | Herb | Wild | Root | Diarrhea | The plant's fresh roots are crushed and combined with water. The medication is then administered daily till recovery in quantities of one water glass | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 64% |

| Pasteurellosis | The plant's freshly formed roots are crushed and combined with water. Then, doses of 1–3 drops of the product are administered | Nasal | Once | Bovine | 52% | ||||||

| Asteraceae | Solanecio gigas (Vatke) C. Jeffrey, (MB-31) | Shecoco gomen (w) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Internal parasite | Crushed fresh plant leaves are blended for five minutes with hot water. After filtration, the produce is then administered orally. The dosage is 1 L each day until the parasite's excretions are removed | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 66% |

| Asteraceae | Spilanthes mauritiana (A.Rich. ex Pers.) DC. Asteraceae (SW 19) | Spilanthes (E), Aydamiia (W), | Herb | Wild | Leave | Internal parasite | Crushed fresh plant leaves are blended for five minutes with hot water. After filtration, the produce is then administered orally. The dosage is 1 L each day until the parasite's excretions are removed | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 66% |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia amygdalina Delile, (SW 52) | Bitter leaf (E), Garaa (W), Girawa (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Internal parasite | The young plant leaf is crushed, combined with water, and then consumed. One liter per day until the body returns to its normal state | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 47% |

| Asteraceae | Vernonis spp. | Buuzuwa (W) | Shrub | Wild |

Flower, Stem Leave |

Babesiosis | Crushed flower mixed with water and filtered. The, the prepared mixture is given orally to drinking | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 35% |

| Trypanosomiasis | Water is combined with crushed plant leaves. After that, one liter of the prepared juice is administered orally every day till recovery | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 23% | ||||||

| Asteraceae | Bidens prestinaria (Sch. Bip.) Cufod, (MB-49) | Chigogot (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Insect bite | The fresh plant leaves were crushed and soaked with water in open dish for an hours. The sauce is then filtered and only the liquid part is collected and smeared | Dermal | Once | Bovine, caprine | 15% |

| Asteraceae | Inula confertiflora A. Rich, (NA89) | Woyina gift (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Eye infection | The dry leaves are ground, powdered, and smeared on the eye | Ocular | Once | Bovine | 66% |

| Wound | The fresh leaves are crushed, squeezed, and the juice is dropped on the victim area | Dermal | Once | Bovine, caprine | 57% | ||||||

| Brassicaceae | Brassica nigra (L.) K.Koch, (BN089) | Oats (E), Senafich (A),Santta ayfiya (W) | Herb | Wild/cultivated | Seed | Bloat | The plant's dried seeds are crushed and combined with water. Until recovery, a dose of one glass of water per day is administered | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 71% |

| Brassicaceae | Lepidium sativum L. (SW 34) | Garden cress (E), Sibbikka (W), Fetto (A) | Herb | Wild/cultivated | Seed | Bloat | By grinding the dried seeds of the plant, the powder is mixed with water, it is good if the water is hot but ok with cold also. One water glass of the preparation is given every day for a week | Oral | Once everyday | Bovine, ovine, caprine, bovine | 23% |

| Caryophyllaceae | Silene macrosolen A. Rich | Silene (E), Wegert (A) | Herb | Wild | Whole body | General illness | Water and the ground-up plant root are combined. The combination is then heated for a short period of time on a stove. After the juice has cooled, it is subsequently introduced three to five drops into each nostril | Nasal | Twice a week | Bovine | 33% |

| Celastraceae | Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell | Qoqoba (A) | Shrub | Wild/cultivated | Leave | Insect bite | The fresh plant leaves were crushed and soaked with water in open dish for an hours. The sauce is then filtered and only the liquid part is collected and smeared | Dermal | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 52% |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe spp, | Flaming Katy (E), Mul’uwa (W) | Herb | Wild | Root, Leave | Abscess | The fresh root cover is collected from plant and applied on the swellings | Topical | Twice | Bovine | 38% |

| Erectile dysfunction ED | The plant's young leaves are crushed and combined with hot water. Following that, the frigid solution is given orally | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 14% | ||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis ficifolius A. Rich, (MB-15) | Cucumbers (E), Ymider enboye (A) | Herb | Wild | Root | Blackleg | Crushed plant roots are combined with cold water. Then, one glass of the solution is administered orally every day until healing has occurred | Oral | Recovery | Bovine | 29% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Lagenaria siceraria (molina) standl. (SW 55) | Bottle gourd (E), Gosiya (W), Kil (A) | Herb | Wild | Fruit | Rabies | Every day for a week, animals are given a half-liter of a mixture made from the crushed fruit of this plant and the leaves of P. dodecandra, together with salt and water | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 12% |

| Cucurbitaceae | Mukia maderaspatana (L.) M.J. Roem | Yeamora misa (A) | Climber | Wild | Leave | Mite infestation | Soaking the fresh leaves of the plant in water. Thereafter, washing the victim site with one water glass of solution per day until parasite load lessens | Dermal | Recovery | Bovine | 25% |

| Cupressaceae | Juniperus procera Hochst. Ex Endl. (SW 56) | African juniper (E), Abeshaa xidaa (W), Tsid (A) | Tree | Wild | Leave | Ectoparasites infestation | Soaking the fresh leaves of the plant in water. Thereafter, washing the victim site with one water glass of solution per day until parasite load lessens | Topical | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 67% |

| Bloating | When in pain, a combination of crushed J. procera leaf and A. sativum bulb is administered. For sheep and goats, one liter of the mixture is administered; for cows and oxen, two liters | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 32% | ||||||

| Dracaenaceae | Sansevieria ehrenbergii Schweinf. Ex Baker, (GC111) | Snake Plants (E), Wende kacha (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Mite infestation | Soaking the fresh leaves of the plant in water. Thereafter, washing the victim site with one water glass of solution per day until parasite load lessens | Dermal | Recovery | Bovine | 77% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha spp. | Love-lies-bleeding (E), Gagabissa (W), Lalisho (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Root | Bloat | The fresh or dried root is ground and soaked with water in 1L bottle | Oral | Twice | Bovine | 92% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton macrostachyus Del. (SW 05) | Woodland croton (E), Anka (W), Bisana (A) | Tree | Wild | Leave | Trauma | Until healing, a tiny amount of powder made from the plant's dried and roasted leaf is applied daily to the victim locations | Dermal | Recovery | Goat, sheep and livestock | 34% |

| Foot rot | The fresh leaves of the plant is crushed and mixed with water. The preparation is then given in doses of one water glass every day in evening for seven consecutive days until recovery | Oral and topical | 7 days | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 35% | ||||||

| Blackleg | Crushed fresh leaves of the plant is mixed with water and filtered. The preparation is then given in doses of one liter once a day | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 22% | ||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia abyssinica J.F.Gmel. (AK 073) | Candelabra Spurge (E), Akkirssaa (W), Qulqual (A) | Herb | Wild | Latex | Rabies | Fresh Euphorbia abyssinica latex is pulverized and either administered topically or ingested | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 44% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia tirucalli L. (SW 57) | Indian tree spurge (E), Maaxxuwa (W), Kinchib (A) | Herb | Wild | Stem | Strangle burning | The fresh stem of the plant is crushed and boiled in hot water. Animals are fumigated with the resulting steam vapor per day until recovery | Fumigation | Once | Equine | 50% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Manihot esculenta Crantz. (SW 10) | Cassava (E), Mitta boyyiya (W), Kassba (A) | Shrub | Cultivated | Leave | Cough | Manihot esculenta fresh leaves are squeezed with water, and the juice is specifically administered orally for chicken | Oral | Once | Galine | 37% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Ricinus communis L. (SW 47) | Castor oil plant (E), Qobuwa (W), Gulo (A) | Herb | Wild/cultivated | Leave | Foot and mouth disease | Crushed fresh plant leaves are combined with water. Up until the animal is healed, one cup of the prepared solution is administered orally each day | Oral | Once everyday | Bovine | 43% |

| Euphorbiaceae | Tragisa spp. | Tinttilashuwa (W) | Herb | Wild |

Root Leave |

Blackleg | The pulverized dry plant root or fresh plant leaf is combined with water, and the resulting preparation is then administered orally one liter every day till recovery | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 14% |

| Fabaceae | Calpurnia aurea (A it.) Benth., (MB-39) | Cape laburnum (E), Mello (W), Digita (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Trypanosomiasis | The plant's fresh leaves are crushed and combined with water. Then, 3 to 4 drops of the preparation are administered |

Nasal (drop), Oral (drinking) |

Every day until recovery | Ovine, bovine | 49% |

| Mite infestation | The plant's fresh leaves are crushed and the sap is anointed on the infested areas | Dermal | Bovine | 65% | |||||||

| Fabaceae | Lonchocarpus laxiflorus Guill. & Perr | Amera (A) | Tree | Wild | Root, leaf | Listeriosis | Crushed root/leaf mixed with water. One glass of the prepared slimy product is administrated orally till recovery | Oral | Recovery | Caprine | 28% |

| Fabaceae | Millettia ferruginea (Hochst.) Bak | Pongamia (E), Zagiya (W), Birbira (A) | Tree | Wild | Root | Trypanosomiasis | Crushed root mixed with water. One glass of the prepared slimy product is administrated orally till recovery | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 20% |

| Fabaceae | Trigonella foenum-graecum L., (BN079) | Fenugreek (E), Abishii (A), Abishiiya (W) | Herb | Wild/cultivated | Seed | Endoparsistes infestation | The dried plant seed is ground the powder is soaked in water. One glass of the prepared product is prescribed orally per day until body condition improved | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 77% |

| Lamiaceae | Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. Ex Benth., (SW 30) | Ocimum (E), Gulluwa (W), Damakessie (A) | Shrub | Wild/cultivated | Leave | Febrile illness | The plant's young leaves are crushed and boiled in hot water. Until recovery, one glass of the preparation is administered | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 14% |

| Linaceae | Linum usitatissimum L., (SW 44) | Linseed (E), Talbbaa (W), Telba (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Seed | Retained placenta | The plant's dried seeds are crushed and boiled for 5–7 min in hot water. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared slimy product is administered orally | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 39% |

| Loganiaceae | Buddleja polystachya Fresen | Buddlea (E), Kanbara (W), Anfar (Atquar) (A) | Shrub | Cultivated | Leave | Internal parasite | The plant's fresh leaves are crushed and combined with water. The medication is subsequently administered once daily in the morning in quantities of one liter | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 47% |

| Malvaceae | Sida schimperiana Hochst. ex A. Rich | Sida (E), Kinddiichchuwa (W), Garida (A) | Herb/Shrub | Wild | Leave | Blackleg | Water is combined with freshly crushed plant leaves. Following that, two to five drops of the prepared juice are then ingested through the nose each day until recovered | Nasal (drop) | Recovery | Bovine | 67% |

| Menispermaceae | Stephania abyssinica (Dillon & A. Rich.) Walp., (MB-13) | Kalala Vine (E) | Herb | Wild | Root | Mastitis | Water and the ground-up plant root are combined. The combination is then heated for a short period of time on a stove. After the juice has cooled, it is subsequently introduced three to five drops into each nostril | Oral (drinking) or Nasal (drop) | Once everyday | Bovine | 64% |

| Moraceae | Ficus vasta Forssk, (GC162) | Warka (A), Wolla (W) | Tree | Wild | Stem bark | Thrips | The plant's fresh stems is pounded and boiled, thereafter the medication is administered right away | Oral | Once | Bovine, caprine | 19% |

| Musaceae | Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman, (SW 07) | Ethiopian banana (E), Utaa (W), Enset (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Whole plant | Eye infection | The whole plant or a fresh leaf is cut or crushed into thin slices. Then, until recuperation, the preparation is provided to eat each day | Ophthalmic | Once/Twice | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 78% |

| Leave | Retained placenta | Fresh leaves from this plant are fed to animals immediately in order to help them expel the placenta | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine | 55% | |||||

| Stem | Retained placenta | Alternatively, a C. arabica leaf and its stem are crushed, cooked, and given to sheep and goats in doses of 2–3 L each | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 67% | |||||

| Myrsinaceae | Maesa lanceolata Forssk, (GC068) | Gegechuwa (W), Kilabo (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Bloat | Crushed leaves mixed with water. One glass of the prepared slimy product is administrated orally till recovery | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 74% |

| Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh, (AA115) | The river red gum (E), Keye baherzafe (A), Habasha zaafiya (W) | Tree | Wild | Leave | General illness | Fresh leaves are crushed, squeezed, and the juice is given nasally | Nasal | Recovery | Bovine | 18% |

| Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. (SW 06) | Tasmanian blue gum (E), Paranjjaa zaafiya (W), Nech baherzaf (A) | Tree | Wild | Leave | Febrile illness | The plant's young leaves are ground up and boiled in hot water. The generated steam vapor is used to fumigate animals once day until they are healthy | Fumigation | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 66% |

| Oleaceae | Jasminum abyssinicum Hochets. Ex DC., (MA60) | Tero hareg/tenbelele (A) | Wild | Leave | Blackleg | Water is combined with freshly crushed plant leaves. Following that, two to five drops of the prepared juice are then ingested through the nose each day until recovered | Oral | Recovery | Bovine | 29% | |

| Papaveraceae | Argemone mexicana L., (AS-57–2017) | Nechlebash (A) | Herb | Wild | Root | Accident | Water is combined with crushed plant leaves. After that, one liter of the prepared juice is administered orally every day till recovery | Oral | Recovery | Bovine | 12% |

| Stem | Sore | The fresh plant stem is chopped and sap is anointed on the victim area | Dermal | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 25% | |||||

| Phytolaccaceae | Phytolacca dodecandra L’H´er., (MB-03) | Endod (E), Hancciciaya (W) | Shrub | Wild | Root, Leave | Rabies | Crushed plant roots/leaf are combined with cold water. Then, one glass of the solution is administered orally or nasally every day until healing has occurred | Oral and nasal | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 58% |

| Poaceae | Hordeum vulgare L., (SW 43) | Barley (E), Banggaa (W), Gebis (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Seed | Bone fractures | Animals are given this plant's boiling or uncooked seed (2–5 kg per day) until they recuperate | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 98% |

| Poaceae | Triticum dicoccon (Schrank) Schübl., (SW 51) | Emmer (E), Banggaa (W), Sinde (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Seed | Bone fractures | Triticum dicoccon dry seeds are served for consumption right away | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 78% |

| Polygonaceae | Rumex nepalensis Spreng., (GC029) | Nepal Dock (E), Hotorsa (W), Yewsha Tult (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave, root | Coughing | The plant's fresh leaves or roots are crushed and combined with water. The juice mixture is then dissolved in a cup of water and administered orally during coughing seasons | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 68% |

| Polygonaceae | Rumex nervosus Vahl, (MB-25) | Curly dock (E), Anchechiya (W), Embuachew (A) | Herb | Wild | Stem | Constipation | Twice a week, new fiber from the plant's crushed stem is combined with water and administered orally. The dosage varies depending on the age of the livestock being treated, but in most cases, a half-liter water bottle is the ideal amount | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 74% |

| Seed | Swelling | The victim region is treated with a liquid that has been made by combining a crushed stem with water and filtering it | Topical application to the wound after opening the swelling | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 47% | |||||

| Leave | External parasites | The dried or fresh plant leave is crushed and the powder or the sauce is applied on the victim site. Has no dosage specificity but the amount and frequency of application depends on the area of infested. High infestation has high application rate and frequencies and vice versa | Topical application | Recovery | Bovine | 26% | |||||

| Ranculucaceae | Ranculucus multifidusfors.sk | Buttercup (E), Selo (W) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Trypanosomiasis | Crushed fresh plant leaves are combined with water. Next, the prepared remedy is administered orally. In order for the animal to recuperate, the prescribed dosage must surpass 3 to 4 cups of coffee each day | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 15% |

| Ranunculaceae | Nigella sativa L., (BN078) | Black cumin (E), Karetta sawuwa/shuquwaa (W), Tikur azmud (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Seed | Colic | The plant's seed is air dried before being pulverized. The powder is then combined with water. Until the symptom goes away, one glass of the prepared product is administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 55% |

| Rhamnaceae | Helinus mystacinus (A it.) E. Mey. ex Steud., (MM097) | Helinus (E), Gofe Gofa (W), Yegib mirkuz (A) | Shrub | Wild | Root | Blackleg | Every day until recovery, the plant's fresh roots are crushed and given to be eaten. Animal are not forced to eat but as per their eating capacity | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine | 25% |

| Rhamnaceae | Rhamnus prinoides L’H´er., (SW 46) | Glossy-leaf (E), Geeshuwa (W), Gesho (A) | Shrub | Wild/cultivated | Leave | Rabies | Crushed fresh plant leaves are combined with water. Until the animal feels better, one glass of the prepared solution is administered orally once per day | Oral | Once a day | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 14% |

| Rosaceae | Prunus africana (Hook. f) Kalkm, (AW-009) | African cherry (E), Onta (W) | Tree | Wild | Leave | Blackleg | Crushed plant leaves are combined with cold water. Following filtration, 1–3 drops of the preparation are administered nasally | Nasal (drop) | Everyday till recovery | Bovine | 74% |

| Rubiaceae | Coffea arabica L., (SW 03) | Arabian coffee (E), Tukkiya (W), Buna (A) | Shrub | Wild/cultivated | Seed | Wound | Until healing, a tiny amount of powder made from the plant's dried and roasted seeds is applied daily to the victim locations | Topical application | Recovery | Bovine, caprine, ovine | 67% |

| Retained placenta | To expel the placenta, cows are given 2–3 L of crushed, boiled E. ventricosum stem and C. arabica leaf mixture, and sheep and goats are given one liter | Oral (drinking) | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 44% | ||||||

| Rubiaceae | Pentas shemperina Hiern, (EM-120) | Pentas (E), Dambburssaa (W), Maraxalliya (W), Yejib mirkuz (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave, root, stem | Blackleg | Filtered water was combined with crushed leaves and stem. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared slimy product is administered orally | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 23% |

| Leave | Bone fractures | The plant's young leaves are crushed and squeezed. Then hot water is used to boil the liquid. Depending on the severity of the condition, the frigid, thick liquid is then filtered and administered orally once or twice a day | Oral | Once or twice a day | Bovine | 56% | |||||

| Rutaceae | Ruta chalepensis L., (SW 33) | Fringed rue (E), Xalotiya (W), Tenadam (A) | Shrub | Cultivated | Leave/Seed | Febrile illness | Water is combined with freshly crushed plant leaves or dried seed powder. For the duration of the animal's recovery, one cup of the prepared solution is administered orally every day | Oral and nasal | Once everyday | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 33% |

| Sapindaceae | Dodonaea angustifolia L.f., (MB-47) | Kitkita (A), Sankarra (W) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Bone dislocation | Crushed plant stems or tubers are immersed in salted water after being crushed. The produced juice is then given orally once every day, up to recovery, in a glass or pan | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 12% |

| Hepatitis | Filtered mixture of water and ground seed mixture is then placed on a hot stove for a little while. The juice is then administered nasally by three to five drops after chilling | Nasal | Once | Bovine | 36% | ||||||

| Rheumatic/ Arthritis | Fresh leaf is crushed, mixed with water, and given orally | Oral | Once | Bovine | 41% | ||||||

| Sapindaceae | Cardiospermum corundum L., (AW-009) | Lesser balloon vine (E), Smeg (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Blackleg | Crushed plant leaves are combined with cold water. Following filtration, 1–2 litter of the preparation are administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine | 71% |

| Scrophulariaceae | Verbascum sinaiticum Benth., (SW 29) | The scallop-leaved mullein (E), Yeaheya joro (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Myiasis | Fresh leaves are crushed, squeezed, and the juice is dropped on the skin | Dermal | Once | Bovine | 81% |

| Root | Erection of hair | Filtered water was combined with crushed fresh root. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared liquid product is administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 62% | |||||

| Root, Leave | Abdominal pain | Filtered water was combined with crushed fresh root/leaf. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared liquid product is administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 29% | |||||

| Simaroubaceae | Brucea antidysenterica JF. Mill., (MB-10) | Bitter bark tree (E), Shushale (W), Aballo (Waginos) (A) | Tree | Wild | Leave and seed | Epizootic lymphangitis | The dried ground seed and fresh leave are mixed with water and given in doses of one liter once a day |

Let them to eat Oral(drinking) |

Twice | Equine | 55% |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L., (SW 20) | Bell pepper (E), Qaariya (A), Kariya (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | Colic | The fresh ripen fruit of the plant is juiced using water as diluent. A dose of one water glass is given | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine, caprine, ovine | 52% |

| Solanaceae | Datura stramonium L., (ET020) | Jimson weed (E), Macharara (W), Laflafuwaa(W), Itse Fars (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Systemic illness | The plant's fresh leaves are crushed and put in water for maceration. Every day for two days, the preparation is given | Oral | Twice | Equine | 42% |

| Skin disease | The pulverized dry leaf is combined with water and applied to the skin | Topical application | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 18% | ||||||

| Solanaceae | Nicotiana tabacum L., (SW 45) | Tobacco (E), Tanbuwa (W), Tibahu (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | Leech infestation | Filtered water was combined with crushed leaves. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared liquid product is administered orally. Alternately, the plant leaf may be roasted and the smoke inhaled | Nasal and oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, Caprine | 32% |

| Trypanosomiasis | Crushed leaves mixed with water and filtered. One glass of the prepared liquid product is administrated orally till recovery. Or, the plant leaf is roasted and the smoke is prescribed nasally | Oral (drinking) Nasal | Once | Bovine | 29% | ||||||

| Coughing | For three days, the leaves of this plant is ground up and combined with water; a single water glass is provided to each cow, ox, donkey, and horse, and half of a water glass to each sheep and goat | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 12% | ||||||

| Leave/Seed | Loss of milk quality | Dairy livestock are given the plant's leaves and seeds, which have been dissolved in water. The prepared food is always fed to dairy cows during milking | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 25% | |||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum incanum L., (SW 48) | Thorn apple (E), Buluwa (W), Enboy (A) | Shrub | Wild | Seed | Leech | Filtered mixture of water and ground seed mixture is then placed on a hot stove for a little while. The juice is then administered nasally by three to five drops after chilling | Nasal (drop) | Once | Bovine, caprine | 47% |

| Solanaceae | Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, (GC048) | Ashwagandha (E), Gizawa (A) | Shrub | Wild | Leave, Stem | Blackleg | Fresh plant stems or leaves are filtered after being combined with water. The liquid is then administered orally twice till recovery | Oral (drinking), Topical | Recovery | Bovine, caprine | 54% |

| Solanaceae | Lycopersicon esculentum Mill | Timatim (A), Timatimiya (W) | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | Leech infestation | The plant's fresh stems is pounded and boiled, thereafter until recovery, one glass of the prepared liquid product is administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 28% |

| Tiliaceae | Triumfetta spp. | Burbark (E), Chyshie (W) | Shrub | Wild | Leave | Trypanosomiasis | The fresh crushed leaves is given to eat orally | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 12% |

| Urticaceae | Girardinia spp. | Nettle (E), Kona (W) | Herb | Wild | Leave, stem, root | Rabies | The plant's fresh leaves, stems, or roots are crushed up and combined with water. After being bitten by a rabid animal, the medication is administered right away | Oral (drinking) | Once | Bovine | 36% |

| Root | Internal parasite | The plant's new roots are crushed and combined with water. The medication is then administered daily till recovery in quantities of one water glass | Oral (drinking) | Twice | Ovine and caprine | 41% | |||||

| Urticaceae | Urtica simensis L., (GC179) | Sama (A) | Herb | Wild | Leave | Pasteurellosis | Filtered water was combined with crushed fresh root. Until recovery, one glass of the prepared liquid product is administered orally | Oral | Once | Bovine | 71% |

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe, (SW 31) | Ginger (E), Yenjjeeluwa (W), Zinjibil (A) | Herb | Cultivated | Stem (tuber) | Bloat | Crushed plant stems or tubers are immersed in salted water after being crushed. The produced juice is then given orally once every day, up to recovery, in a glass or pan | Oral | Recovery | Bovine, ovine, caprine | 81% |

Keys; A Amharic, national language of the country, E English, W Wolaitic, regional language of the Wolaita people

Fig. 2.

Frequency of the 32 plant families used in the treatment of livestock diseases

Collection habitat and growth pattern of medicinal plants.

A total of 54 medicinal plants were identified, of which 62(66%) were collected from the wild, 24(26%) were grown in private gardens, and the remaining plant species 8(8%) was gathered from both agricultural and uncultivated wilderness areas. In terms of growth patterns, herbs made up 42(56%) of the higher plant species and were the most frequently gathered to treat livestock diseases, followed by shrubs 24(31%) and trees 10(12%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Medicinal Plants Growth habit

Use knowledge of medicinal plants among people

Despite the fact that male informants reported 133(65%) more medicinal plants than female respondents 72(35%), the difference was statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). Similar to this, there were reported medicinal plant differences between the community unable to read and write 64(80%) and educated groups 41(20%) that were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Compared to general informants, key informants knew a considerably (p < 0.05) a greater number of therapeutic plants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical test of knowledge among different groups of informants on average number of medicinal plants reported

| Parameters used | Groups of informants | N | % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 133 | 64.87 | 0.53 |

| Female | 72 | 35.12 | ||

| Age | Youngest age range (20–39 years old) | 37 | 10.04 | 0.000 |

| Senior group (40–85 years old) | 168 | 81.95 | ||

| Educational level | Illiterate | 164 | 80 | 0.01 |

| Educated | 41 | 20 | ||

| Informant category | Key informants | 130 | 63.41 | 0.003 |

| General informants | 75 | 36.58 | ||

| Years of experience producing livestock | 5–10 | 55 | 26.83 | 0.000 |

| 11–20 | 65 | 31.7 | ||

| 21–30 | 70 | 34.14 | ||

| Above 30 | 15 | 7.31 | ||

| Method of raising livestock | Subsistence | 165 | 80.48 | 0.002 |

| Commercial | 40 | 19.51 | ||

| The way that animals are treated | Medicinal plants only | 48 | 23.41 | 0.01 |

| Combination of medicinal plants and conventional medicine | 157 | 76.58 |

N number of study participants; significance difference (p < 0.05)

Acquiring and sharing the knowledge of native medicinal plants

From a total of 205 practitioners, 179 (87%) said they had heard stories about medicinal plants from members of their family, especially their father and grandparents, in a very private way. The remaining 15 (7%) and 11 (6%) picked up knowledge of medicinal plants from reading various sources, and trial-and-error, respectively.

Distribution of medicinal plants

The land use and land cover (LULC) data of the study area comprises more than 10 different flora distribution classes (Fig. 4, upper). The habitat of the medicinal plants in the whole Wolaita can be divided into three parts in terms altitude—lowlands (Lowland < 1500 m.a.s.l; near and around villages, collection time within a day, collection areas easily accessible) and highlands (Highland > 2300 m.a.s.l; far from villages, collection takes more than a day, collection areas remote and hard to access) and midland (Midland 1500–2300 m.a.s.l) small villages near the district towns, collection takes not more than a day, collection areas near and accessible) (Fig. 4, lower). Out of the reported species, 29 species are found in the lowlands and 18 species were found in the highlands with 31 species common in lowlands and highlands (Fig. 5). Generally, collection of highland medicinal plants is difficult and hence storage of such species for further use is common practice in the study area.

Fig. 4.

Land use – Land cover and digital elevation model (DEM) of Wolaita Zone (Source: AcrMap10.4.1 by Abenezer Wendimu)

Fig. 5.

Distribution of medicinal plants in terms of altitude

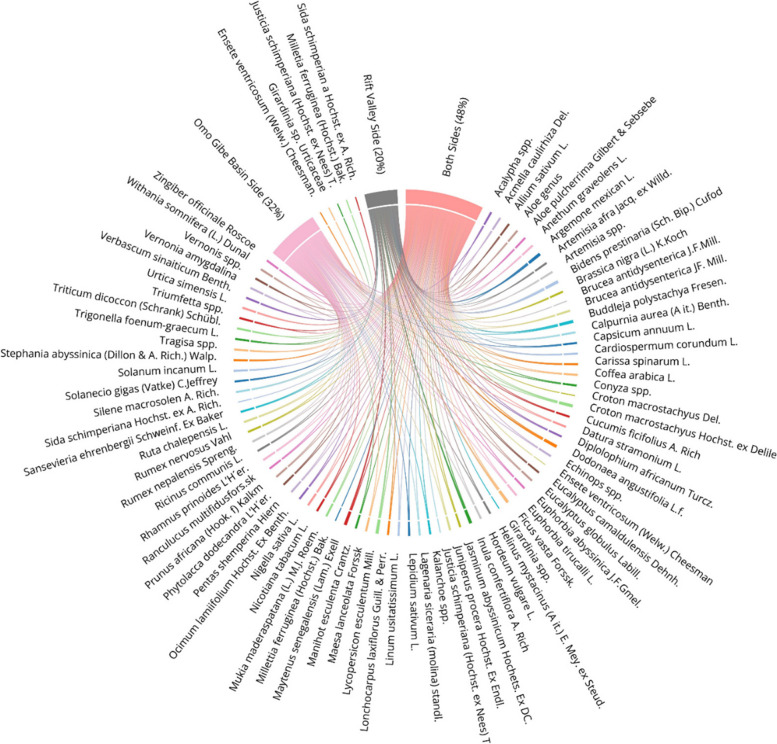

The distribution of medicinal plants in terms of major drainage basins in Wolaita revealed that, Omo-Gibe basin holds about 32% of total collection of medicinal plants where as 20% were collected from Rift Valley basin. A significant amount of medicinal plants overlap were recorded from the two basins with 48% of collections common to both basins (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Distribution of medicinal plants in terms of drainage basins

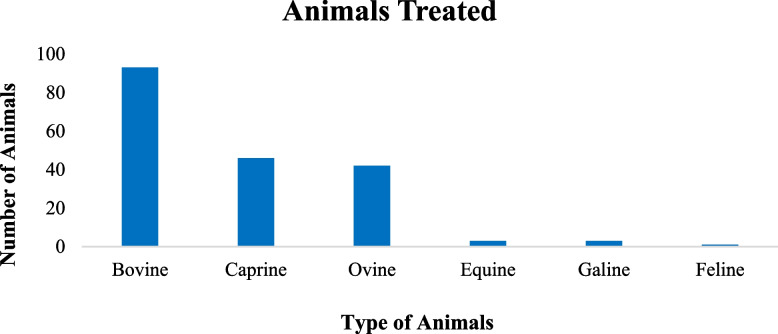

Aspects of animal disease in the study area

This study found 55 different forms of animal illnesses. Highest number of species (16) were prescribed to treat blackleg followed by 10 species to bloat, 8 Trypanosomosis, and 7 each in colic and leech infestation (Table 3). Practitioners noted that they might utilize one or several medicinal plant species to treat a certain type of sickness. Endoparasite infestation, blackleg, and colic were the most common types of diseases treated by 9 medicinal plant species. In the Wolaita zone, the therapeutic indication of medicinal plant-based medicines included all livestock species. Medicinal plant cures were most frequently prescribed for Bovine ailments 93(49%), followed by Caprine 46(24%), Ovine 42(22%), Equine 3(2%), Galline 3(2%), and Feline 1(1%) aliments (Fig. 7).

Table 3.

Ailments treated

Fig. 7.

Animals treated by traditional medical preparations in the study area

Parts of the medicinal plants utilized in the concoction of herbal remedies

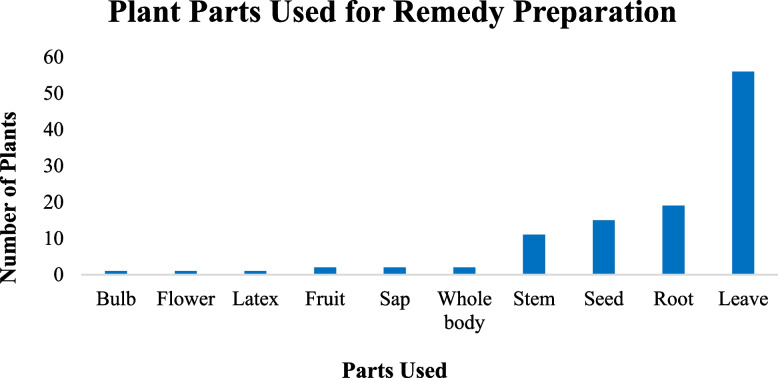

In the study area, leaves 55(52%) were the most often employed plant components in the preparation of remedies, followed by root 18(17%), seed 14(13%), and stems 10(9%). The remaining fruit, sap and whole parts of the plants contributed for 2% and 1% of the remedy preparation were prepared from bulb, flower and latex (Fig. 8). Regarding the state of the plant parts, freshly harvested plant parts dominated (80%), with the remaining 20% being used in both freshly and in a dried form.

Fig. 8.

Plant parts used for preparation of the remedies

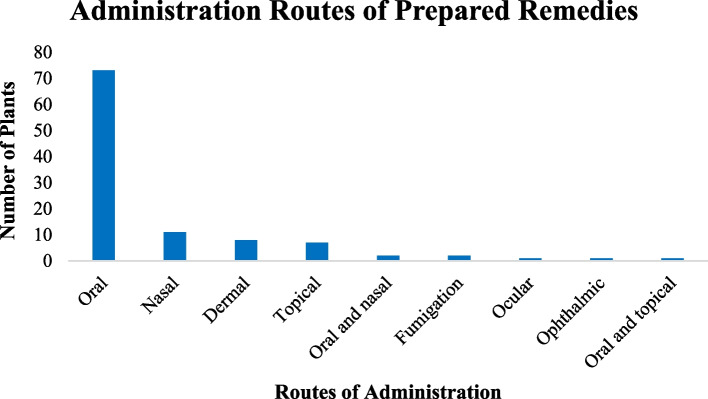

The routes of remedy administration

The target animal and the type of sickness determined how to administer ethnobotanical preparations. In the study area, the most common modes of administration were nasal, oral, topically/dermally, and intraocularly, and others include applying the medication directly to a fresh lesion or cut. Oral 73(69%) and nasal 11(10%) routes were the most frequently used delivery methods followed by dermal 8(7%) and topical 7(7%) administration routes. Ethnomedicines applied via the ophthalmic and ocular modes of administration routes were the least cited routes (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

The administration routes of ethnobotanical preparations

Informant consensus factor

Blackleg, bloat, and endoparsistes each had the highest values of the consensus factor among the informants, which were followed by trypanosomiasis (0.8) and colic (0.79) (Fig. 10). Leech and rabies took the next two spots (0.75 each).

Fig. 10.

Livestock ailments in the study district along with the Consensus Factor of Informants (ICF)

Fidelity level

Hordeum vulgare L. had the highest fidelity level (FL = 98%) for treating bone fractures followed by Acalypha spp. for treating bloat (FL = 92%) (Table 2).

Preference ranking

According to data collected from six key informants, Withania somnifera was the most potent remedy for treating blackleg. Tragisa spp. and Kalanchoe spp. were the next most efficient therapeutic plants. Ocimum lamiifolium and Prunus africana were, in comparison, the least effective plants for medicinal purposes, according to the data gathered from six key informants (Table 4).

Table 4.

Preference ranking medicinal plants to treat blackleg

| No | Medicinal plants name | Informants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | I2 | I3 | I4 | I5 | I6 | Total score | Ranking | ||

| 1 | Ocimum lamiifolium | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 9th |

| 2 | Prunus africana | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 8th |

| 3 | Sida schimperian a | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 7th |

| 4 | Stephania abyssinica | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 6th |

| 5 | Croton macrostachyus | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 21 | 5th |

| 6 | Allium sativum L | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 22 | 4th |

| 7 | Kalanchoe spp | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 24 | 3rd |

| 8 | Tragisa spp. | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 24 | 2nd |

| 9 | Withania somnifera | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 25 | 1st |

Medicinal plant threats in the area

Both natural factors (such as drought and landslides) and anthropogenic factors (firewood, overgrazing, agricultural expansion, construction, and medicinal use) have an impact on the survival of medicinal plants in the study district. The main dangers to medicinal plants in the study district were the expansion of agriculture, followed by drought and development (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Medicinal plants conservation threats in the study area

Discussion

Livestock is essential to the livelihoods of the inhabitants of the study districts for a variety of reasons, including crop production, draft power, marketing, and revenue generating. Despite the fact that knowledge differed depending on the age and sex group, this causes the residents of the district to have the knowledge to defend their animals from a variety of illnesses using therapeutic plants. There were just 64.87% of women respondents in this survey, whereas there were 35.12% men. The elders may pass on their knowledge to their older son or to their preferred son rather than their daughter, which could be the cause of this. A different Ethiopian region has also observed similar results [37, 38]. The reason behind this preference for passing on knowledge to a male heir rather than a female one may be rooted in traditional gender roles and societal norms. In many cultures, especially patriarchal ones, sons are often seen as the ones who will carry on the family legacy and continue the family line, while daughters are expected to marry into another family. Additionally, there may be a belief that certain types of knowledge are better suited for men to carry on, such as medicinal or magical practices that require physical strength or are traditionally performed by men. It is important to note that these beliefs are based on outdated gender stereotypes and should not be used to justify discrimination against female family members. Even though, on average, males used slightly more medicinal herbs than women, the differences were not that much big and statistically insignificant (p = 0.53). Other factors may be influencing the higher usage of medicinal herbs among males, but further research is needed to determine these factor.. This finding was consistent with the conclusions reached by Yigezu et al. [39]. The study also revealed that older groups of informants reported a considerably larger average number of therapeutic plants than the youngest group (p < 0.05). The main factors to this notable disparity are the growth of modern medicine and the younger age groups' disinterest in traditional medications. There could be other factors at play, such as differences in cultural upbringing, access to traditional medicine, or differing beliefs about the effectiveness of traditional remedies.

In addition, the youthful group lacks interest due to the seasonal scarcity of therapeutic plants and their hard harvesting. As a result, a decline in positive attitudes toward traditional medicine is a sign that knowledge of these practices and the species of medicinal plants is eroding. The research by Yigezu et al. [39] and Lulekal et al. [40] got the same results. In accordance, significantly (p < 0.05) more medicinal plants were reported by illiterate respondents than by educated respondents. This is because respondents who were educated preferred modern treatment and paid less attention to traditional medicine. In turn, this leads to a decline in medical expertise in the following generation. By Birhan et al. [8], the same conclusion was reported. Key informants could report significantly more medicinal plants than general informants (p < 0.05) as a result of their experience.

The identification and documentation of 78 ethnoveterinary medicinal plant species, including their scientific and local names, habits, methods of preparation, and used components, was included in the present study. The dominant families were Euphorbiaceae and Asteraceae. Ethiopia's Amhara region, according to Lulekal et al. [40], likewise exhibited a predominance of the Asteraceae family. However, the family Solanaceae has been found in various regions of Ethiopia [11, 18, 41, 42], which goes against this study. The district is home to a diverse population, according to this result. Furthermore, the preference for native and endemic plants with therapeutic properties shows that people don't have contemporary knowledge but rather has a lengthy history and is handed down from one generation to the next over an extended period of time. This finding was consistent with studies by Mengesha [43] and Lulekal et al. [40].

The bulk of plant growth forms investigated for medicinal purposes were herbs; shrubs came in second, and trees and climbers next in sequential order of species. In a different region of Ethiopia, a high consumption of shrubs for their therapeutic benefits was noted [18, 41, 44]. This can occur as a result of the relatively abundant herb availability for practitioners in the study districts. According to other findings [37, 45, 46], shrubs predominate.

The majority of the plants in this study—32 (61.5%)—were gathered from the wild, while 11 (25%) were taken from backyard gardens, and the remaining 7 (13.5%) species were found in both backyard and wild habitats. The results of other authors [18, 40, 44, 46] were consistent with this finding. This indicates that growing plants in a home garden for therapeutic reasons is quite uncommon in the research area. This decreased practice of growing medicinal plants in backyard gardens results in a lack of those plants throughout the year as desired by practitioners.

Many medicinally important plant species were reported to be found in the mid-altitudinal ranges (1500–2300 m.a.s.l) for the ollection areas were near and accessible. This is in line with Kunwar and Bussmann [47] who reported an increase of medicinal plant species with increasing altitude up to about 2000 m.a.s.l. The medicinal plant diversity corresponds with total richness of plant diversity [48], however, the high value species were reported from the highland areas.

Although different plant parts have been used to treat various illnesses, leaves and seeds were the two plant parts most frequently used in the study district. This result is consistent with research conducted by Tekle [49] in the southern Ethiopian Amaro special district, the western Ethiopia Horro Gudurru district [18], and the eastern Harerghe Melkabello district [41]. It disagrees, however, with studies done by Jima and Megersa [50] in the Berbere District of Oromia region and by Seid [44] in the Amhara region's Enarj Enawega District's east Gojjam Zone [8]. The persistence of plants in their native environment is not significantly impacted using leaves for medication. However, the use of roots for medicinal purposes could result in the extinction of certain species from their natural habitats as well as the native plant medicine expertise is being lost. The majority of practitioners in the research district like plants in fresh 60 (80%) circumstances. The results of Chekole et al. [51] are consistent with this finding. The harvesting of fresh plant material used by practitioners to make medicines during the dry season may cause the plants' species to be stripped.

Oral form of administration accounted for 62 (74%) of all administrations, followed by nasal mode of administration (13%) and cutaneous mode of administration (8%). This result was consistent with that of Yigezu et al. [39]. There is no standard unit of measuring for plant remedies in the study district; instead, people use their own system of measurement. The medication dosage is based on the age, breed, and size of the animals that are receiving treatment. Other authors reported the same results [42, 52–56].

Blackleg (0.82), general sickness (0.8), and pasteurellosis (0.79), according to informants' consensus factors (ICF), had the highest values. Blackleg received the highest plant citation at the time, 10(30.3%), followed by general disease 7(21.21%). This makes it very evident that blackleg is a widespread and well-known illness in the studied area. There are 10 ethnoveterinary medicinal herbs that can be used to treat this condition. Vernonia amygdalina was the most popular medicinal plant species for treating blackleg, followed by Cucumis ficifolius and Solanecio gigas. According to Mengesha and Dessie [53] and Tadesse et al. [54], different districts used the same ethnoveterinary medicinal herbs that were identified in the research districts to treat blackleg.

In general, the research area has a high biodiversity, and the locals have a wealth of conventional knowledge concerning the use of herbal remedies to treat certain livestock diseases. A variety of indigenous plant species can be found in the study region. The findings of this investigation demonstrated that the district's expertise and therapeutic plants are vulnerable. Therefore, it necessitates special consideration from the public, the government, and all stakeholders.

The cultural interpretation of medicinal plants and diseases in the Wolaita region offers a fascinating glimpse into the rich heritage and traditional knowledge of the local community. For generations, the people of Wolaita have developed a profound understanding of the medicinal properties of various plants, which they have used to treat and manage a wide range of diseases and ailments. The traditional healers, known as "hiillaa," play a significant role in preserving this knowledge and administering remedies derived from the region's diverse flora. These healers possess an intimate understanding of both the physical and spiritual aspects of healing, often incorporating rituals, prayers, and incantations into their practices. In the study area, specific diseases are attributed to spiritual or supernatural causes, leading to the use of specific plants and rituals aimed at appeasing or combatting these metaphysical influences. The cultural interpretation of medicinal plants and diseases in Wolaita intertwines the deep-rooted beliefs, values, and practices of the local population, showcasing their respect for nature and their reliance on traditional wisdom passed down through generations.

Limitation of the study

The study was conducted in small portions of the Omo-Gibe and Rift Valley basins in Ethiopia, which may not fully represent the entire ethnobotanical use of plants in treating livestock ailments of these basins. Future studies should aim to include a more comprehensive assessment of the ethnobotanical use of plants in these basins to provide a more holistic understanding of medicinal plant species diversity, use, distribution, and abundance in the area.

Conclusions

The communities that were chosen are mainly rural in character, and livestock farmers are looking into the local biodiversity and indigenous knowledge systems to satisfy the demands of animal health and productivity. In the study region, 78 ethnoveterinary species of medicinal plants from 28 distinct families were discovered. The Euphorbiaceae and Asteraceae plant families made up the majority of those that were noted. Herbs were the most frequently collected to cure livestock sickness and made up higher plant species in terms of growth patterns. Most of the plants were collected from the wild. According to practitioners, they would use one or several therapeutic plant species depending on the disease. Nine different species of medicinal plants were used to cure the most frequent ailments, including colic, blackleg, and endoparasite infestation. Bovine ailments were most frequently treated using medicinal plant remedies. The plant's fresh leaves were the plant parts that were most frequently used to make medicines. The most popular remedy administrative methods in the study area included the nose, mouth, skin, eyes, and others, including applying the drug directly to a fresh lesion or cut. Blackleg, bloat, and endoparsistes had the highest values of the consensus factor among the informants, according to the data. According to data collected from six important informants, Withania somnifera was the most potent remedy for treating blackleg. The primary threats to botanical medicine in the study region were the expansion of agriculture, followed by drought and development. Despite the fact that the research region in the districts of the Wolaita Zone was proven to be rich in a variety of medicinal plants, there are currently few attempts being made to look at the native knowledge and plants associated with them. To prevent such losses, communities at large along with accountable organizations must protect therapeutic plants. It's also important to choose plants for further study that have a high potential based on the relevant ethnobotanical indices, such as phytochemical analysis and pharmacological and toxicological investigations. In general, the research area has a high biodiversity, and the locals have a wealth of conventional knowledge concerning the use of herbal remedies to treat certain livestock diseases. A variety of indigenous plant species can be found in the study region. The findings of this investigation demonstrated that the district's expertise and therapeutic plants are vulnerable. Therefore, it necessitates special consideration from the public, the government, and all stakeholders.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the administrative and agricultural offices of the study districts. We also want to express our gratitude to the informants and development agents who helped us gather all data needed for the study. We are also grateful to Wolaita Sodo University for approving our request to conduct the research. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

A.W. collected data, wrote the main manuscript text, study area mapping and formal analysis. E.B and Y.A. assisted data collection, project administration and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The study received no funding from government, commercial, or non-profit financing organizations.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the supplementary information file(s).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This manuscript doesn’t contain any person’s data, and further consent for publication isn’t required.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Varijakshapanicker P, Mckune S, Miller L, Hendrickx S, Balehegn M, Dahl GE, Adesogan AT. Sustainable livestock systems to improve human health, nutrition, and economic status. Anim Front. 2019;9:39–50. doi: 10.1093/af/vfz041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakale MV, Mwanza M, Aremu AO. Ethnoveterinary knowledge and biological evaluation of plants used for mitigating livestock diseases: a critical insight into the trends and patterns in South Africa. Front Vet Sci. 2021;891:710884. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.710884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottet A, Teillard F, Boettcher P, De’Besi G, Besbes B. Domestic herbivores and food security: current contribution, trends and challenges for a sustainable development. Animal. 2018;12:s188–s198. doi: 10.1017/s1751731118002215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banda LJ, Tanganyika J. Livestock provide more than food in smallholder production systems of developing countries. Anim Front. 2021;11:7–14. doi: 10.1093/af/vfab001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Jaarsveld BDL, Pieters BDH, Potgieter EDB, vanWyk GDN, Pfitzer KDS, Trümpelmann LD, et al. Monthly Report on Livestock Disease Trends as Informally Reported by Veterinarians Belonging to the Ruminant Veterinary Association of South Africa (RuVASA), a Group of the South African Veterinary Association; Ruminant Veterinary Association of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017; p. 28.

- 6.Maikhuri R. Eco-energetic analysis of animal husbandry in traditional societies of India. Energy. 1992;17:959–967. doi: 10.1016/0360-5442(92)90045-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dovie DB, Shackleton CM, Witkowski E. Valuation of communal area livestock benefits, rural livelihoods and related policy issues. Land Use Policy. 2006;23:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2004.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birhan YS, Kitaw SL, Alemayehu YA, Mengesha NM. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants and practices in Enarj Enawga District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int J Anim Sci. 2018;2(1):1014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabuti JR, Dhillion SS, Lye KA. Ethnoveterinary medicines for livestock (Bos indicus) in Bulamogi county, Uganda: plant species and mode of use. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;88:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGaw LJ, Eloff JN. Ethnoveterinary use of southern African plants and scientific evaluation of their medicinal properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:559–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wendimu A, Tekalign W, Asfaw B. A survey of traditional medicinal plants used to treat common human and livestock ailments from Diguna Fango district, Wolaita, southern Ethiopia. Nord J Bot. 2021;39(5):1–20. doi: 10.1111/njb.03174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraha T, Balcha A, Mirutse G. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoveka LN, van der Bank M, Bezeng BS, Davies TJ. Identifying biodiversity knowledge gaps for conserving South Africa’s endemic flora. Biodivers Conserv. 2020;29:2803–2819. doi: 10.1007/s10531-020-01998-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wall B, Mateus A, Marshall L, Pfeiffer D, Lubroth J, Ormel H, Otto P, Patriarchi A. Drivers, Dynamics and Epidemiology of Antimicrobial Resistance in Animal Production; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6209e.pdf.

- 15.Elizabeth A, Hans W, Zemede A, Tesfaye A. The current status of knowledge of herbal medicine and medicinal plants in Fiche Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomedicine. 2014;10:1–33. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynam T, De Jong W, Sheil D, Kusumanto T, Evans K. A review of tools for incorporating community knowledge, preferences, and values into decision making in natural resources management. Ecol Soc. 2007;12:5. doi: 10.5751/ES-01987-120105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beinart W, Brown K. African Local Knowledge & Livestock Health: Diseases & Treatments in South Africa. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birhanu T, Abera D. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants at selected Horro Gudurru Districts, Western Ethiopia. African Journal of Plant Science. 2015;9(3):185–192. doi: 10.5897/AJPS2014.1229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGaw LJ, Famuyide IM, Khunoana ET, Aremu AO. Ethnoveterinary botanical medicine in South Africa: a review of research from the last decade (2009 to 2019) J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;257:112864. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisner H. What makes the systems engineer successful? various surveys suggest an answer; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL. USA. 2020 doi: 10.1201/9781003089650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bredemus BA. Consensual qualitative research analysis of prominent multicultural psychotherapy researchers’ career experiences; the chicago school of professional psychology proquest dissertations Publishing: Chicago, IL. USA. 2021 doi: 10.1037/a0012051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruchac M. Indigenous knowledge and traditional knowledge. Encycl Glob Archaeol. 2014;10:3814–3824. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abebe D. Traditional medicine in Ethiopia: the attempts being made to promote it for effective and better utilization. SINET. 1986;9:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giday M, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z. Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asfaw Z. Proceedings of Workshop on Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Institute of Biodiversity Conservation and Research; 2001. The role of home gardens in the production and conservation of medicinal plants. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hecht S, Yang AL, Basnett BS, Padoch C, Peluso NL. People in Motion, Forests in Transition: Trends in Migration, Urbanization, and Remittances and Their Effects on Tropical Forests; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2015;142. 10.17528/cifor/005762.

- 27.Crane PR, Ge S, Hong DY, Huang HW, Jiao GL, Knapp S, Kress WJ, Mooney H, Raven PH, Wen J. The Shenzhen declaration on plant sciences-uniting plant sciences and society to build a green, sustainable earth. J Syst Evol. 2017;55:59–61. doi: 10.1111/jse.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalonde A. African indigenous knowledge and its relevance to sustainable development. International program for traditional ecological knowledge, 1993, Ottawa. https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/904/African_Indigenous_Knowledge_and_its_Relevance_to_Environment_and_Development_Activities.pdf?sequence=1.

- 29.Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Population Size by Sex, Region, Zone and Wereda: July 2021. https://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Population-of-Weredas-as-of-July-2021.pdf.

- 30.Bagnara GL. Agricultural Production and Market of Wolaita Rural Area (Ethiopia). Technical Report. 2017. 10.13140/RG.2.2.34313.95846.

- 31.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) Tables: Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region Archived 2012–11–13 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, and 3.4. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell B. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative methods. 3. California: Altamira Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kongsager R. Data collection in the field: lessons from two case studies conducted in belize. Qual Rep. 2021;26:1218–1232. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The World Flora Online. (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/. Accessed 1 – 9 2023.

- 35.The Plant List (http://www.theplantlist.com. Accessed 1 – 9 2023.

- 36.Chakale MV, Asong JA, Struwig M, Mwanza M, Aremu AO. Ethnoveterinary practices and ethnobotanical knowledge on plants used against livestock diseases among two communities in South Africa. Plants. 2022;11:1784. doi: 10.3390/plants11131784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abebe M. The study of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants at Mojana Wodera district, central Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0267447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chekole G. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used against human ailments in Gubalafto District, Northern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):1–29. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0182-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yigezu Y, Haile DB, Ayen WA. Ethnoveterinary medicine in four districts of Jimma zone, Ethiopia: cross sectional survey for plant species and mode of use. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:76. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lulekal E, Asfaw Z, Kelbessa E, Damme PV. Ethnoveterinary plants of Ankober districts, North Shewa zone, Amhara region Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:21. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammed C, Abera D, Woyessa M, Birhanu T. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants in Melkabello District, eastern Harerghe zone Eastern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veter J. 2016;20(2):1–15. doi: 10.4314/evj.v20i2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leul K, Gebrecherkos G, Tadesse B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Ganta Afeshum District, Eastern Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]