Abstract

Background/Aim

Aiming to resolve debates on honey’s efficacy for radiotherapy-induced severe oral mucositis in head and neck cancer, we conducted a meta-analysis focused on randomized trials, primarily assessing severe mucositis incidence. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, pain management, and honey types.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, WOS, and the Cochrane Library up to December 2023. The analysis concentrated on randomized controlled trials that assessed the efficacy of honey, targeting the incidence of mucositis as the main outcome. Additional outcomes explored were weight loss, intolerable pain, and the specific types of honey used in interventions. Data analysis was performed using CMA software, and a funnel plot was employed to identify publication bias.

Results

The analysis of 176 records resulted in the inclusion of 10 studies with 599 patients receiving radiotherapy. The research showed that honey significantly reduced the occurrence of grade 3-4 mucositis (severe mucositis), provided significant pain relief, and had a positive effect on reducing weight loss. Regarding the type of honey used, no significant differences were found in their effectiveness in alleviating severe mucositis.

Conclusion

Honey serves as an effective intervention for individuals with oral mucositis. It can be considered as an adjuvant in the management of clinical radiotherapy-associated oral mucositis, particularly for patients requiring prolonged use of anti-analgesic or antifungal medications.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, chronic pain, ulcer, antifungal, anti-analgesic

Radiotherapy stands as a cornerstone in the fight against cancer, offering hope to many, particularly those who battle head and neck cancers (1). However, it is not without its tribulations; patients will endure radiation-induced mucositis, a prevalent but debilitating side effect. This condition, characterized by inflammation, ulceration, and pain, not only impairs quality of life, but also complicates the continuity of cancer treatment (2).

The search for remedies has led clinicians to honey, a substance with anti-inflammatory (3) and healing activities (4). Its application in modern clinical settings has expanded to the management of wounds of various etiologies, including those inflicted by radiation therapy. Although a study (dating back to 2003) (3) has supported the role of honey in ameliorating the effects of radiation on oral tissues, the scientific community has yet to reach a consensus, partly due to a mixture of both positive and less encouraging results from various trials.

A meticulous review of existing meta-analyses has identified a significant oversight: the impact of honey on radiation-induced mucositis has not been conclusively validated, primarily because previous meta-analyses have aggregated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of radiotherapy with those of combined chemo-radiotherapy, misinterpreting the specificity of the results. Furthermore, the issue of high heterogeneity among studies has clouded the true effectiveness of honey, leaving healthcare professionals uncertain about the integration of this natural remedy into standard mucositis care protocols.

To bridge these research gaps, we conducted a rigorous evaluation of honey’s impact on mucositis, its contributions to weight stabilization, and alleviation of pain specifically in the post-radiotherapy setting. Utilizing an innovative analytical methodology, we were able to reduce data heterogeneity significantly, thus paving the way for a more precise comprehension of honey’s therapeutic efficacy in these clinical outcomes.

Recent research has shown that honey does not significantly affect milder forms of radiation-induced mucositis (5). Consequently, this meta-analysis is focused on examining the effectiveness of honey in the treatment of severe oral mucositis.

Materials and Methods

Data sources and selection criteria. We searched for RCTs exploring the impact of honey on oral mucositis related to radiotherapy, utilizing databases, such as PubMed, Embase, WOS, and the Cochrane Library, covering the period from January 2010 to December 2023. The keywords used were “honey”, “radiotherapy”, “radiation”, “mucositis”, “head and neck neoplasm”, and “head and neck cancer”. The search was limited to clinical trials with human subjects. Our methodology adhered to the guidelines set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Articles sourced through this approach were accessed, and their bibliographies were reviewed for further pertinent studies. Only studies published in English were included; exclusions encompassed case reports, technical reports, conference papers, reviews, letters, editorials, and laboratory-based research. Oral mucositis grade was measured using the World Health Organization (WHO), Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), or Oral Mucositis Assessment (OMA) scales.

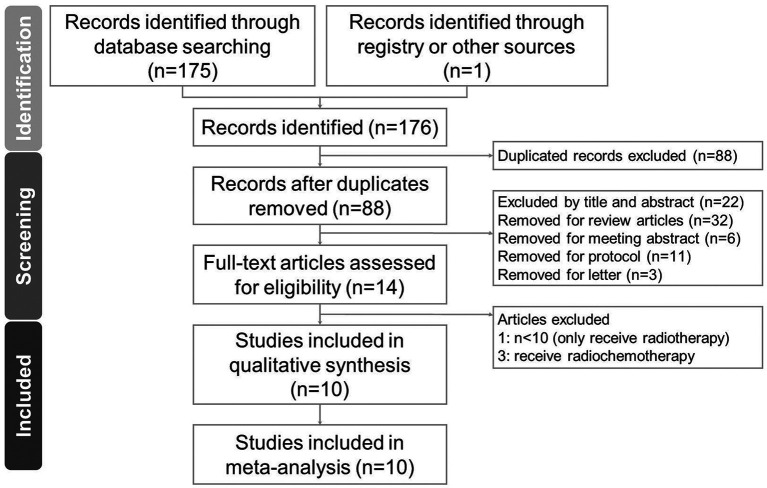

Selection of studies. The data screening and selection process was performed independently by two authors (CPL and SYG) and was verified by a third author (RYT). A hard copy of all the articles was obtained and read in full. Details of the selection process are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of the study selection process for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data extraction. Authors CPL and SYG independently performed data extraction utilizing a standard form in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook guidelines (6). Extracted information included study author(s), publication year and country, inclusion criteria, participant numbers, research design, intervention details and honey varieties, along with the outcomes and their measurement methods.

Outcomes. Primary outcomes were evaluated utilizing the WHO, RTOG, and OMA scales, which are established metrics for assessing mucositis. Mild mucositis was categorized as grades 1 and 2, whereas grades 3 and 4 were classified as severe mucositis. The incidence of each mucositis grade was recorded starting from the second week of radiotherapy and subsequently every two weeks until the conclusion of treatment. Secondary outcomes, including weight loss and oral cavity pain scores, were assessed upon treatment completion. Pain levels were measured using visual analog scales.

Quality assessment. Two authors (CPL and RYT) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (7) was calculated for quality assessment of the included studies. Disagreements were resolved through consultations with a third reviewer to reach a consensus. A study was judged to be at high risk of bias overall if at least one domain showed a risk of bias.

Data analysis. For each included study, we calculated the standard mean difference (SMD) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing the intervention and placebo groups. To aggregate these SMDs, a random-effects model was utilized. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Between-trial heterogeneity was determined using the I2 test, and values >50% were regarded as considerable heterogeneity. Funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to examine potential publication bias. Statistical significance was defined as p-values <0.05, except for the determination of publication bias, which employed p<0.10. Subgroup analysis was conducted to find the reason for high heterogeneity. Literature publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots. Sensitivity analysis was carried out by excluding an individual study each time to assess the stability of our results.

Results

Study search and characteristics of included patients. We identified 88 unique articles of RCTs during the initial screening through title and abstract review, which were subsequently narrowed down to 14 articles for detailed assessment after excluding those that did not meet our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). With careful reading, four records were eliminated due to receiving radio-chemotherapy (8-10) and a small sample size (n<10) (11). As a result, ten articles were included in this meta-analysis (3,12-20). For the RCTs included in this study, two were double-blind (14,15) and six were single-blind (3,13,17-20). The final quantitative analysis included 599 participants. The characteristics and study methodology are shown in Table I.

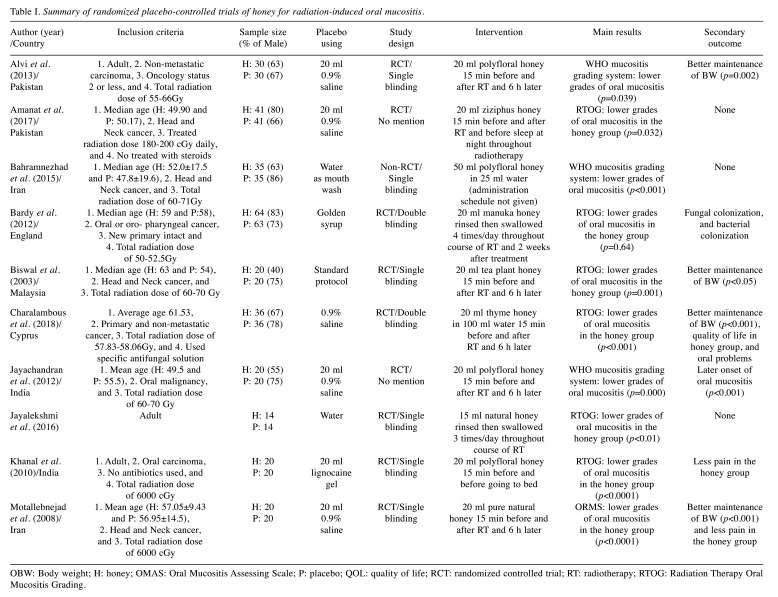

Table I. Summary of randomized placebo-controlled trials of honey for radiation-induced oral mucositis.

OBW: Body weight; H: honey; OMAS: Oral Mucositis Assessing Scale; P: placebo; QOL: quality of life; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RT: radiotherapy; RTOG: Radiation Therapy Oral Mucositis Grading.

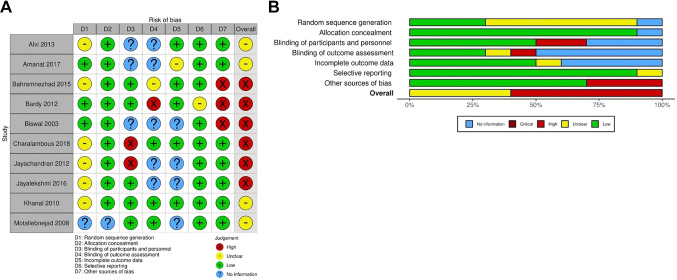

Quality assessment. The risk of bias was moderate in seven domains in the included trials and all trials were limited in quality. Ten studies were RCTs, and one study did not mention the method of random sequence generation; two trials used a double-blind design, six trials used a single-blind design, and two trials did not clearly mention the type of design. Three trials did not mention whether there was bias according to sex. The results of the Cochrane Collaboration are shown in Figure 2A and B.

Figure 2. Assessment of methodological quality of the included trials. (A) Risk of bias for each included study. (B) The overall summary of bias of the ten studies.

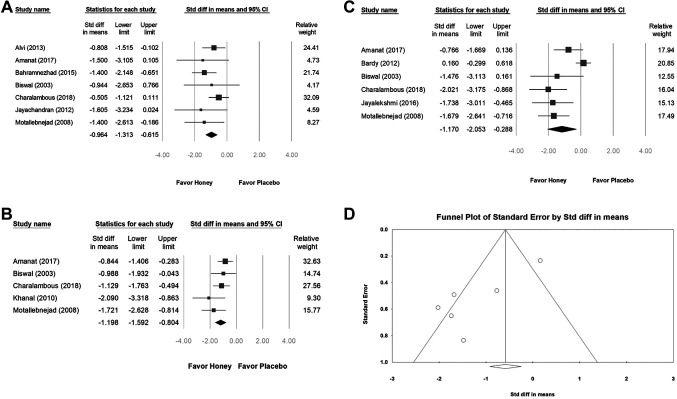

Impact of honey on mucositis. We found that, the intervention with honey in patients with severe mucositis demonstrated a significant effect on preventing severe mucositis at week 2 (SMD=−0.964, 95%CI=−1.313 to −0.615; I2=0%, p=0.526), week 4 (SMD=−1.198, 95%CI=−1.592 to −0.804; I2=20.391%, p=0.285), and week 6 (SMD=−1.170, 95%CI=−2.053 to −0.288; I2=80.390%, p=0.000) (Figure 3A, B, and C). We conclude that from the beginning of the treatment, honey effectively regulated severe grade mucositis. The results of the meta-analysis comparing the incidence of mucositis after radiotherapy revealed high heterogeneity in the week 6 group (I2>50%) (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3. The effect of honey on radiation-induced oral mucositis by WHO and RTOG scales was compared with placebo from the 2nd week (A), 4th week (B) to the 6th week (C) of treatment. (D) Funnel plot for figure C studies reporting.

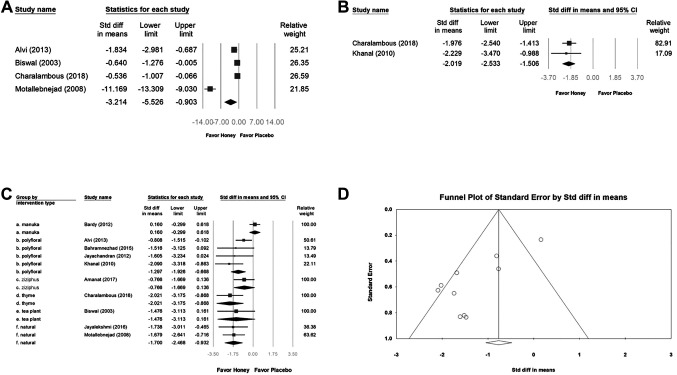

Impact of honey on body weight loss. Four studies reporting reduced body weight loss were included in the pooled analysis (SMD=3.214, 95%CI=−5.526 to −0.903). High heterogeneity was observed between the intervention and control groups between the studies (I2=96.801%, p=0.000). Although all four trials revealed that the intervention reduced weight loss [especially in the study by Motallebnejad et al. (19)], more trails are required to certify the honey effect (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis of the effects of honey on body weight loss (A) and pain relief (B) after radiotherapy. (C) Subgroup analysis of the effect of different honey types on radiation-induced oral mucositis by WHO and RTOG scales was compared with placebo at treatment completion. (D) Funnel plot for figure C studies reporting.

Impact of honey on intolerable pain. Two studies that reported honey-associated relief of intolerable pain were included in the pooled analysis (SMD=−2.019, 95%CI=−2.533 to −1.506; I2=0%, p=0.716). Although those two trials shown that the intervention relieved intolerable pain, more trails are required to confirm the honey effect (Figure 4B).

Honey type. The other subgroup analyses (Figure 4C) were performed to explore whether the study findings were influenced by honey type. The results showed that most types of honey can relieve severe oral mucositis caused by radiation therapy, but it is worth noting that there is no significant difference in the effect between honey types. Based on this result, we believe that there is no need to insist on expensive honey types.

Publishing bias. The Egger’s test indicated no obvious publication bias. The funnel plot for the SMD of honey intervention preventing severe mucositis in week 6 is shown in Figure 3D and the effect of types of honey on alleviating severe oral mucositis is shown in Figure 4D.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis offers critical perspectives on the role of honey in managing severe mucositis among patients receiving radiotherapy, highlighting its significant ability to mitigate this challenging side effect of cancer therapy. We observed a significant protective effect of honey against severe mucositis, particularly from the second week of treatment. Honey’s prevention of severe mucositis early on aligns with the common clinical observation that more severe mucositis tends to develop in the latter stages of radiotherapy. This timing suggests honey’s role may be more prophylactic than previously understood.

One of the most noteworthy outcomes is the pronounced effect of honey in reducing the incidence of severe mucositis (grades 3 and 4). When we compared our findings with existing literature (5,16), our pioneering discovery was the reduction in incidence of severe mucositis, indicating honey’s broader protective spectrum. A recent study suggested that honey’s intervention within the first three weeks is crucial for its effectiveness against grade 4 mucositis, underscoring the importance of early and proactive management strategies (5). This nuanced understanding adds a valuable layer to the body of research that has mostly concentrated on honey’s impact on severe mucositis. Our study’s approach to analyzing mucositis grades over time allows for a more detailed understanding of honey’s therapeutic timeline.

Interestingly, our study observed a notable decrease in weight loss among patients treated with honey, aligning with reduced severity of mucositis. This correlation suggests that mitigating mucositis can contribute to better nutritional outcomes and potentially enhance overall patient well-being during radiotherapy. However, the impact of honey on pain management did not exhibit significant differences, indicating the subjective nature of pain and the potential influence of patient adherence and perception of treatment. The diverse types of honey used across the included studies and their varying antibacterial and antifungal properties call for further research to identify specific honey types that may offer the most benefit. Additionally, the optimal administration protocol for honey remains to be determined, with studies employing various dosages and treatment durations.

The substantial reduction in heterogeneity compared to previous meta-analyses (21-23) marks a significant methodological improvement in our study, enhancing the reliability of our conclusions. By isolating the effects of honey in the absence of chemotherapy, we have provided a clearer picture of its role in managing radiotherapy-induced mucositis. This specificity is a stride forward in mucositis research and may inform more targeted clinical applications of honey as an adjunct therapy.

Our meta-analysis brings important findings to light, but the small number and size of the trials suggest careful interpretation of the results. The varied methods for measuring pain and weight loss point to a need for standardized approaches in the future. More comprehensive, multi-center studies with consistent measurement techniques are needed to solidify these findings. Additionally, further research should delve into how honey might prevent milder mucositis and its specific healing actions against radiation-related mucosal damage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this discussion emphasizes the promising role of honey in preventing and treating severe mucositis, while also acknowledging the need for further research to fully understand its benefits across all grades of mucositis. The findings advocate for a strategic approach to honey’s application in clinical settings, tailored to the severity of mucositis and the timing of treatment to maximize its therapeutic potential.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

CPL, CCC, and RYT contributed to the study conception, performed the risk of bias analysis, screened all identified studies, assessed the risk of bias, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. SYG, CHK, and HJY contributed to the study design. All Authors reviewed and drafted the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants provided by the Chung Shan Medical University (CSMU-INT-111-18) and Tungs’ Taichung MetroHarbor Hospital (TTMHH-R1120039).

References

- 1.Scully C, Epstein J, Sonis S. Oral mucositis: A challenging complication of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiochemotherapy. Part 2: Diagnosis and management of mucositis. Head Neck. 2004;26(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/hed.10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sciubba JJ, Goldenberg D. Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(2):175–183. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswal BM, Zakaria A, Ahmad NM. Topical application of honey in the management of radiation mucositis. A Preliminary study. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(4):242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0443-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karimi Z, Behnammoghadam M, Rafiei H, Abdi N, Zoladl M, Talebianpoor MS, Arya A, Khastavaneh M. Impact of olive oil and honey on healing of diabetic foot: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:347–354. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S198577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An W, Li S, Qin L. Role of honey in preventing radiation-induced oral mucositis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct. 2021;12(8):3352–3365. doi: 10.1039/d0fo02808h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Cochrane Collaboration Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Second edition. edn. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley-Blackwell. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, Mcaleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pach D, Brinkhaus B, Roll S, Wegscheider K, Icke K, Willich SN, Witt CM. Efficacy of injections with Disci/Rhus toxicodendron compositum for chronic low back pain—a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries M, van Rijckevorsel DCM, Vissers KCP, Wilder-Smith OHG, van Goor H, Pain and Nociception Neuroscience Research Group Tetrahydrocannabinol does not reduce pain in patients with chronic abdominal pain in a phase 2 placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(7):1079–1086.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan H, Zheng L, Lai Y, Lu W, Yan Z, Xiao Q, Li B, Tang M, Huang D, Wang Y, Li Z, Mei Y, Jiang Z, Liu X, Tang Q, Zuo D, Ye J, Yang Y, Huang H, Tang Z, Xiao J, China Irritable Bowel Syndrome Consortium Tongxie formula reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1724–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawley P, Hovan A, McGahan CE, Saunders D. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of manuka honey for radiation-induced oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(3):751–761. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amanat A, Ahmed A, Kazmi A, Aziz B. The effect of honey on radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23(3):317–320. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_146_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahramnezhad F, Dehghan Nayeri N, Bassampour SS, Khajeh M, Asgari P. Honey and radiation-induced stomatitis in patients with head and neck cancer. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(10):e19256. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardy J, Molassiotis A, Ryder WD, Mais K, Sykes A, Yap B, Lee L, Kaczmarski E, Slevin N. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial of active manuka honey and standard oral care for radiation-induced oral mucositis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(3):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charalambous M, Raftopoulos V, Paikousis L, Katodritis N, Lambrinou E, Vomvas D, Georgiou M, Charalambous A. The effect of the use of thyme honey in minimizing radiation - induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;34:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayachandran S, Balaji N. Evaluating the effectiveness of topical application of natural honey and benzydamine hydrochloride in the management of radiation mucositis. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18(3):190–195. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.105689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayalekshmi JL, Lakshmi R, Mukerji A. Honey on oral mucositis: A randomized controlled trial. Gulf J Oncol. 2016;1(20):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanal B, Baliga M, Uppal N. Effect of topical honey on limitation of radiation-induced oral mucositis: an intervention study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(12):1181–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motallebnejad M, Akram S, Moghadamnia A, Moulana Z, Omidi S. The effect of topical application of pure honey on radiation-induced mucositis: A randomized clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(3):40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvi Z, Mahmood A, Rasool S, Ali U, Arif S, Ishtiaq S, Maqsood T. Role of honey in prevention of radiation induced mucositis in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;63(3):379–383. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu TM, Luo YW, Tam KW, Lin CC, Huang TW. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of honey on radiochemotherapy-induced mucositis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2361–2370. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu JL, Xia R, Sun ZH, Sun L, Min X, Liu C, Zhang H, Zhu YM. Effects of honey use on the management of radio/chemotherapy-induced mucositis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45(12):1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian X, Xu L, Liu X, Wang CC, Xie W, Jiménez-Herrera MF, Chen W. Impact of honey on radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(4):1431–1441. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]