Earth’s precursor material lost most carbon through sublimation in the nebular disk shortly after the Sun’s birth.

Abstract

Carbon is an essential element for life, but its behavior during Earth’s accretion is not well understood. Carbonaceous grains in meteoritic and cometary materials suggest that irreversible sublimation, and not condensation, governs carbon acquisition by terrestrial worlds. Through astronomical observations and modeling, we show that the sublimation front of carbon carriers in the solar nebula, or the soot line, moved inward quickly so that carbon-rich ingredients would be available for accretion at 1 astronomical unit after the first million years. On the other hand, geological constraints firmly establish a severe carbon deficit in Earth, requiring the destruction of inherited carbonaceous organics in the majority of its building blocks. The carbon-poor nature of Earth thus implies carbon loss in its precursor material through sublimation within the first million years.

INTRODUCTION

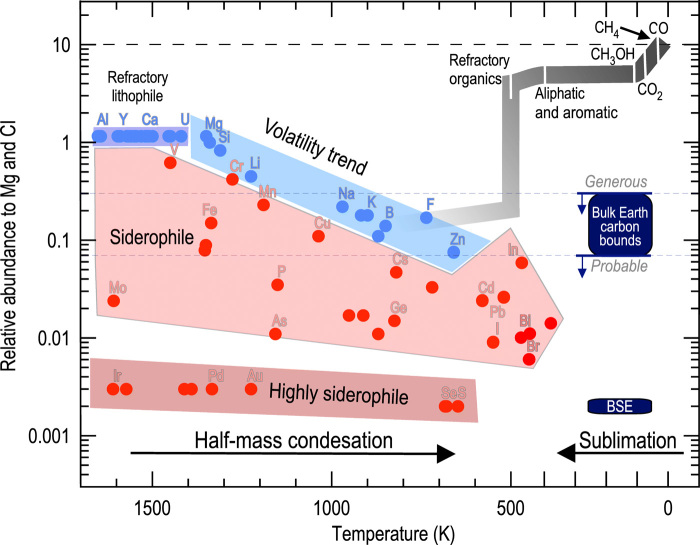

Carbon provides an essential constituent of terrestrial life and plays a critical role in maintaining Earth’s habitable environment. Elucidating the processes of carbon acquisition by rocky planetary bodies is therefore crucial for understanding planetary habitability. Conventional condensation models for Earth formation typically assume chemical equilibrium and posit that elements were initially present in nebular gas and became available for accretion into solid bodies when the gases were sufficiently cool to precipitate (1, 2). As seen in Fig. 1, for refractory and moderately volatile lithophile elements (such as Mg, Si, Na, and K), the degree of depletion in the bulk silicate Earth (BSE) correlates with the element’s half-mass condensation temperature (1), consistent with the condensation model. However, equilibrium condensation cannot explain the quantities and forms of carbon found in primitive chondrites and comets. At 10−3 bar pressure, major carbon carriers (CO, CO2, and CH4) in the nebular gas do not condense at temperatures above 80 K and, therefore, remain gaseous within tens of astronomical units (AU) from the forming Sun (1, 3, 4). Consequently, chondrites and terrestrial worlds would have received no carbon. The presence of notable, although depleted, carbon in chondritic meteorites thus requires the creation or preservation of more refractory carbon-rich solids within the solar nebula than predicted by equilibrium condensation models.

Fig. 1. The sublimation sequence of carbon in the solar nebula.

An element’s relative abundance to Mg and CI is the ratio of its relative abundance to Mg to that in CI, calculated as (C/Mg in Earth or solar)/(C/Mg in CI) in wt %. On the high-temperature side, the volatility trend (blue-shaded band) describes the relative abundances of lithophile elements (rock loving, blue circles) in the bulk silicate Earth (mantle and crust) as a function of their half-mass condensation temperatures (1). Siderophile elements (iron loving, red circles) plot below the volatility trend, presumably due to preferential incorporation into the core. On the low-temperature side, the sublimation sequence of carbon (gray thick line) traces the falling relative abundance of condensed carbon in the solar nebula (excluding H and He) as the disk warms up (tables S4 and S5). The abundance (relative to Mg and CI) of condensed carbon starts at 9.48 (long dashed line) and is reduced to 4.74 after carbon-carrying ices transform into gases. It falls precipitously by more than one order of magnitude when the nebular temperature reaches ~500 K. The maximum amount of carbon in the bulk Earth (large dark blue box), represented by a generous upper bound of 1.7 ± 0.2 wt % carbon (0.30 ± 0.03 relative to Mg and CI) and a probable bound of 0.4 ± 0.2 wt % carbon (0.07 ± 0.04 relative to Mg and CI), corresponds to a maximum fraction of 1 to 7% carbon-rich source material that survived sublimation (table S6). The bulk silicate Earth (BSE; small dark blue box) with 140 ± 40 ppm (parts per million) carbon by weight (1.7 ± 0.5 × 10−3 relative to Mg and CI) plots well below the upper bounds, possibly due to sequestration of carbon by the core.

Clear evidence for the survival of unprocessed prestellar grains has been found in the meteoritic record (5). These carbonaceous organics are not products of condensation from a hot atomized nebula, and, therefore, some or all must have been inherited from the interstellar medium (ISM) without ever being sublimated. However, the amount of carbon locked away as refractory solids in the ISM is far greater than carried by the most primitive and least processed meteorites (CI chondrites) that otherwise reflect solar composition (6, 7). The presence of inherited carbon-rich solids at sub-ISM levels thus suggests that interstellar carbonaceous grains are partially destroyed in the inner solar system. Here, we model the sublimation sequence and loss of carbon in the solar nebula. These results are then combined with derived upper bounds on the carbon content of the bulk Earth to investigate how nebular processes influence the acquisition of carbon by rocky planetary bodies.

RESULTS

The carbon content of solid aggregates in a protoplanetary disk depends on the extent of heating they experience; hence, the sublimation sequence of carbon carriers as a function of nebular temperature rises to prominence as the governing process for carbon acquisition by terrestrial worlds. Astronomical observations show that approximately half of the cosmically available carbon entered the protoplanetary disk as volatile ices and the other half as carbonaceous organic solids (6). As the disk warms up from 20 K, all the volatile carbon carriers sublimate by 120 K, followed by the conversion of major refractory carbon carriers into CO and other gases near a characteristic temperature of ~500 K (table S1 and fig. S1). The sublimation sequence of carbon exhibits a “cliff” where dust grains in an accreting disk lose most of their carbon to gas within a narrow temperature range near 500 K (Fig. 1).

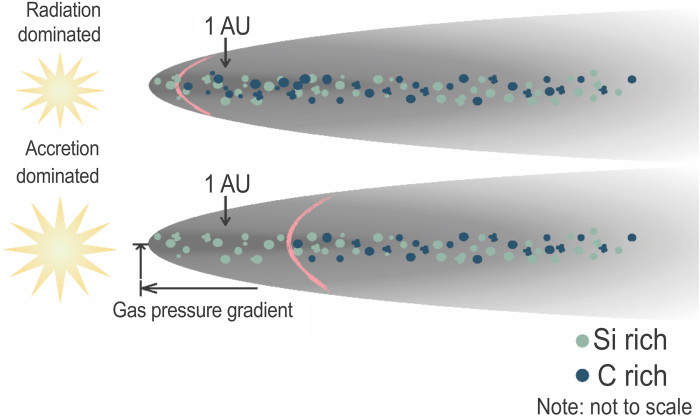

The division between the stability fields of solid and gas carbon carriers corresponds to the “soot line,” a term coined to describe the location where the irreversible destruction of presolar polycyclic hydrocarbons via thermally driven reactions in the planet-forming region of disks occurred (8). In the earliest phases of star formation, the soot line migrates with time as the pressure and temperature of the disk evolve (Fig. 2). Disk observations suggest an order-of-magnitude variation in the accretion rate at a given time, but there is a clear general decline of accretion rate with age (9). Very early after the Sun’s birth, when high accretion rates from the solar nebula onto the Sun provided a source of disk heating, Tsoot of 500 K may have been reached out to tens of astronomical units near the disk midplane. As the accretion rate diminished and stellar irradiation became the dominant source of heating in the disk, the soot line then migrated inward to eventually cross 1 AU and reside interior to Earth’s current orbit.

Fig. 2. Schematic illustration of the soot line in a protoplanetary disk.

The soot line (red parabola) delineates the phase boundary between solid and gaseous carbon carriers. In the accretion-dominated disk phase, it is located far from the proto-Sun and divides carbon-poor dust and pebbles (green dots) from carbon-rich ones (dark blue dots). Within 1 Ma, as a result of the transition to a radiation-dominated, or passive, disk phase, the soot line migrates inside Earth’s current orbit. Note that the Si-rich and C-rich solids do not represent distinct reservoirs because carbonaceous material is likely associated with silicates. They are provided for ease in illustration.

A key proviso in the sublimation model is that the carbon-depleted precursor material of the inner solar system must have resided within the soot line. Our calculated thermal structures of disks illustrate that at accretion rates higher than 10−7 M⦿ (solar mass)/year, the soot line resides beyond 1 AU and potentially as far away as the asteroid belt (fig. S3). If the primary materials accreted by Earth are assembled during this phase, they would be carbon poor, as the carbon grains would be destroyed while silicate grains could remain intact. For systems with accretion rates below ~10−7 M⦿/year, the soot line lies within the current Earth orbit. Hence, preplanetary solids that exist at 1 AU during this phase are likely to be carbon rich, similar to other objects known to form at low temperatures, such as comets Halley and 67/P. Observations show that the accretion rate in forming disk systems decreases so rapidly with time that the soot line would move inward to cross 1 AU within 1 Ma (9); thus, the carbon-poor objects in Earth’s chief feeding zone near 1 AU are likely present only during the first million years of solar system history in the phase associated with high mass accretion rates. If the bulk carbon content of Earth is low, then most of its source materials must have lost carbon through sublimation early in the nebula’s history or by additional processes such as planetesimal differentiation. Constraining the fraction of carbon-depleted source material accreted by Earth requires us to constrain the maximum amount of carbon in the bulk Earth.

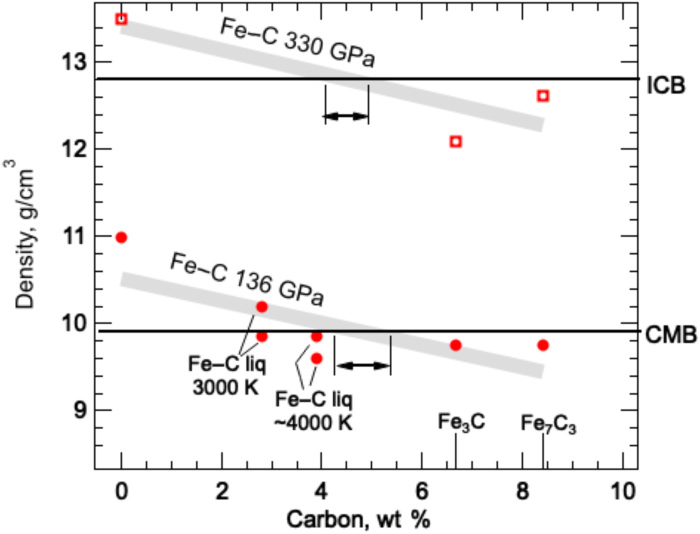

In the near-surface reservoirs, carbon occurs in trace quantities at the level of hundreds of parts per million (ppm) by weight (10). The carbon content of the BSE is more than three orders of magnitude below the solar composition (Fig. 1). The severe carbon deficit in the accessible part of Earth has been attributed to its volatility and possible sequestration by the iron-rich core. The strong affinity of carbon for iron-rich alloys at low to moderate pressures suggests that the core could be Earth’s largest carbon reservoir (10–12). As such, it is helpful to seek geochemical and geophysical constraints on the carbon content of the core, which then places limits on carbon in the bulk Earth. Carbon is considered a candidate lighter element for Earth’s core because it may partially account for important physical properties, including density, sound speeds, elastic anisotropy, and the partially solidified state (11). A generous upper bound on core carbon content is obtained from density considerations (Fig. 3). The liquid outer core and solid inner core are less dense than pure iron at the relevant P-T (pressure-temperature) conditions by 5 to 8% and 2 to 5%, respectively (11), and carbon could reduce or eliminate this density difference. With the equations of state of liquid iron and relevant iron-carbon alloys (13–15), we estimate that 5.0 ± 0.6 and 4.5 ± 0.5 wt % carbon could account for the entire density deficits in both the liquid outer and solid inner core (16). Hence, the amount of carbon in the core from the density constraints must be less than 5.0 ± 0.5 wt %. This estimate is undoubtedly generous because the outer core contains notable amounts of sulfur, silicon, and oxygen (11) and possibly hydrogen (17).

Fig. 3. Generous upper bounds on carbon in Earth’s core, from density constraints.

The density of Fe─C alloy at the inner core boundary (ICB) or the core-mantle boundary (CMB) as a function of carbon content is estimated from that of iron and Fe─C alloys at 330 GPa and 5500 ± 1500 K [red squares (13)] and that at 136 GPa and 4500 ± 1500 K [red-filled circles (14–15)], respectively. The thick trends are linear fits through experimental data on solid Fe─C alloys and compounds (top) and liquid Fe─C alloys (bottom). The horizontal black lines are the inferred densities at the ICB and CMB based on the Preliminary Reference Earth Model (PREM) (16). The horizontal arrows denote the ranges of carbon concentrations in iron-carbon alloys to match the core densities, considering uncertainties in core temperatures and mineral physics measurements. The maximum estimated carbon in the liquid outer and the solid inner core are 5.0 ± 0.6 and 4.5 ± 0.5 wt %, assuming that carbon is the sole light element in the core to account for the observed densities (16).

More probable upper bounds may be obtained by comparing the sound velocities of Fe─C alloys with the values observed for the core. Existing data suggest that the presence of 1.0 ± 0.6 wt % carbon in liquid iron would match the compressional wave velocity (Vp) of the outer core (fig. S5). Because this composition falls on the iron-rich side of the eutectic point of the Fe─C binary (fig. S6), the solid inner core would contain less carbon and, therefore, is limited to <1.0 ± 0.6 wt %.

The maximum amount of carbon in the bulk Earth can then be calculated from estimated upper bounds on that of the BSE and core. The BSE probably contains 140 ± 40 ppm carbon by weight and most likely no more than 0.1 wt % (18). With the core accounting for 32% of Earth’s mass, we arrive at a generous upper bound of 1.7 ± 0.2 wt % carbon, and a more probable upper bound of 0.4 ± 0.2 wt % (4000 ± 2000 ppm by weight) carbon in the bulk Earth. We emphasize that these are robust upper bounds and they are higher than the 530 ± 210 ppm by weight estimate from geochemical constraints (19) and the recent estimate of 370 to 740 ppm from a multistage model of core formation using partition coefficients determined at relevant pressure and temperature conditions (12).

According to the sublimation sequence (Fig. 1), carbon-rich source material is stable outside the soot line, but the abundance of carbon relative to Mg and CI falls precipitously from 4.74 to <0.47 because of sublimation of organic carbon carriers inside the soot line (table S6). The estimated upper bound for the bulk Earth carbon at 0.2 to 1.9 wt % corresponds to a maximum fraction of 1 to 7% carbon-rich source material in Earth’s building blocks. The carbon-poor nature of Earth implies that most of its precursor materials lost carbon. Because the soot line was already located inside 1 AU by ~1 Ma, carbon loss from Earth’s building blocks must occur very early in the solar history. If the sublimation temperature were higher than 500 K, then at a given disk cooling rate, the soot line would reach 1 AU sooner. Consequently, the accretion of carbon-poor building blocks to the proto-Earth would have to take place earlier.

DISCUSSION

Earth’s severe carbon deficit is consistent with the expectation of limited contribution of carbon-rich solids via pebble drift. The latest model for planet formation suggests that centimeter- to meter-sized objects known as pebbles played a major role in delivering mass to growing bodies. Pebbles form via coagulation and settle to the dust-rich midplane where they are subject to forces leading toward an inward drift (20). These pebbles would thus carry both water and carbon from the outer solar system, beyond the soot line, to the inner solar system (21). Dynamic simulations show that pebbles drift inwards to the local pressure maximum (pressure bump) in the disk (22, 23), which would nominally be the inner edge, marking the destruction of the silicate dust (Fig. 2). However, a multi-Earth–sized planet or giant planet core in the disk would carve out a gap in the gaseous disk, with the outer edge representing a local pressure bump. Drifting pebbles would pile up there, thus diminishing the supply of carbon-rich precursors (24). Analysis of molybdenum and tungsten isotopes find evidence for two distinct reservoirs of meteorite parent bodies within the solar nebula that formed as early as 1 Ma and remained separate thereafter, presumably as a result of the formation of Jupiter’s core (25). This scenario would reduce the supply of carbon to the inner solar system. It is worth noting that pressure bumps are pervasive in million-year-old disks (22, 26), and they may be induced via other means (27). Furthermore, in pebble accretion models, rapid formation of ~100-km-sized bodies is further accelerated. If such bodies formed early in solar system history, especially within the first 0.1 to 0.2 Ma, radiogenic heating by short-lived 26Al can cause degassing (28). Thus, there are additional mechanisms of volatile loss through planetesimal degassing, also active in the first million years of evolution, aside from the sublimation sequence discussed here that have caused Earth’s carbon deficit.

Very early carbon depletion in Earth’s source material is supported by the carbon-poor nature of iron meteorites (29), which also formed in less than 1 Ma after CAIs (calcium- and aluminum-rich inclusions) (30). The notion of extensive carbon loss is also consistent with the composition of moderately or slightly volatile elements in Earth (e.g., Na, K, Li, and Si). The correlation between the bulk Earth abundance of an element and its half-mass condensation temperature (Fig. 1) implies thermally activated volatile loss, which requires that most of Earth’s precursor materials were heated at least above the sublimation temperature of carbon-rich presolar grains. Sublimation is likely important for other life-essential elements such as nitrogen and hydrogen. At some point, the sequences of condensation and sublimation must merge (Fig. 1), and in the intermediate stages, both processes could contribute to the creation and destruction of nebular solids, thereby setting the stage for the formation of habitable worlds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Modeling soot line location as a function of time

We calculated sublimation temperatures of refractory carbon carriers using a kinetic rate law and experimentally constrained parameters (fig. S1 and table S1). To determine the location of the soot line as a function of time, we calculated the thermal structure within a protoplanetary disk that is heated by internal viscous dissipation and irradiation from the central star (fig. S3).

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Nittler and an anonymous reviewer for critically reading the manuscript and helping us improve and clarify it. Funding: This research was supported by NSF grants AST 1344133, EAR 1763189, and AST1907653 and by the NASA Astrobiology Program, grant NNX15AT33A. Author contributions: J.L., E.A.B., G.A.B., F.J.C., and M.M.H. contributed equally to the project design and writing. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/14/eabd3632/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lodders K., Solar system abundances and condensation temperatures of the elements. Astrophys. J. 591, 1220–1247 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonough W. F., Sun S.-s., The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 3.E. A. Bergin, L. I. Cleeves, Chemistry during the gas-rich stage of planet formation, in Handbook of Exoplanets, H. J. Deeg, J. A. Belmonte, Eds. (Springer, Cham., 2018), pp. 2221–2250. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gail H.-P., Trieloff M., Spatial distribution of carbon dust in the early solar nebula and the carbon content of planetesimals. Astron. Astrophys. 606, A16 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’D. Alexander C. M., Nittler L. R., Davidson J., Ciesla F. J., Measuring the level of interstellar inheritance in the solar protoplanetary disk. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 52, 1797–1821 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergin E. A., Blake G. A., Ciesla F., Hirschmann M. M., Li J., Tracing the ingredients for a habitable earth from interstellar space through planet formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8965–8970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiss J., Composition measurements and the history of cometary matter. Astron. Astrophys. 187, 859–866 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kress M. E., Tielens A. G. G. M., Frenklach M., The ‘soot line’: Destruction of presolar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the terrestrial planet-forming region of disks. Adv. Space Res. 46, 44–49 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann L., Herczeg G., Calvet N., Accretion onto pre-main-sequence stars. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 54, 135–180 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.B. J. Wood, J. Li, A. Shahar, Carbon in Earth, R. M. Hazen, A. P. Jones, J. A. Baross, Eds. (Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry, 2013), vol. 75, pp. 231–250 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.J. Li, B. Chen, M. Mookherjee, G. Morard, Carbon versus other light elements in Earth’s core—A combined geochemical and geophysical perspective, in Deep Carbon Past to Present, B. Orcutt, I. Daniel, R. Dasgupta, Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019), pp. 40–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer R. A., Cottrell E., Hauri E., Lee K. K. M., Voyer M. L., The carbon content of Earth and its core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 8743–8749 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morard G., Nakajima Y., Andrault D., Antonangeli D., Auzende A. L., Boulard E., Cervera S., Clark A. N., Lord O. T., Siebert J., Svitlyk V., Garbarino G., Mezouar M., Structure and density of Fe-C liquid alloys under high pressure. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 7813–7823 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morard G., Andrault D., Antonangeli D., Bouchet J., Properties of iron alloys under the Earth’s core conditions. C. R. Geosci. 346, 130–139 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakajima Y., Imada S., Hirose K., Komabayashi T., Ozawa H., Tateno S., Tsutsui S., Kuwayama Y., Baron A. Q. R., Carbon-depleted outer core revealed by sound velocity measurements of liquid iron–carbon alloy. Nat. Commun. 6, 8942 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dziewonski A. M., Anderson D. L., Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 25, 297–356 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose K., Tagawa S., Kuwayama Y., Sinmyo R., Morard G., Ohishi Y., Genda H., Hydrogen limits carbon in liquid iron. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5190–5197 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirschmann M. M., Comparative deep Earth volatile cycles: The case for C recycling from exosphere/mantle fractionation of major (H2O, C, N) volatiles and from H2O/Ce, CO2/Ba, and CO2/Nb exosphere ratios. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 502, 262–273 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marty B., The origins and concentrations of water, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases on Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 313–314, 56–66 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.S. J. Weidenschilling, J. N. Cuzzi, Formation of planetesimals in the solar nebula, in Protostars and Planets III (Univ. Arizona Press, 1993), p. 1031. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ida S., Yamamura T., Okuzumi S., Water delivery by pebble accretion to rocky planets in habitable zones in evolving disks. Astron. Astrophys. 624, A28 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dullemond C. P., Birnstiel T., Huang J., Kurtovic N. T., Andrews S. M., Guzmán V. V., Pérez L. M., Isella A., Zhu Z., Benisty M., Wilner D. J., Bai X.-N., Carpenter J. M., Zhang S., Ricci L., The Disk Substructures at High Angular Resolution Project (DSHARP). VI. Dust trapping in thin-ringed protoplanetary disks. Astrophys. J. Letters 869, L46 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teague R., Bae J., Birnstiel T., Bergin E. A., Evidence for a vertical dependence on the pressure structure in AS 209. Astrophys. J. 868, 113 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinilla P., Benisty M., Birnstiel T., Ring shaped dust accumulation in transition disks. Astron. Astrophys. 545, A81 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruijer T. S., Burkhardt C., Budde G., Kleine T., Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6712–6716 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrews S. M., Huang J., Pérez L. M., Isella A., Dullemond C. P., Kurtovic N. T., Guzmán V. V., Carpenter J. M., Wilner D. J., Zhang S., Zhu Z., Birnstiel T., Bai X.-N., Benisty M., Meredith Hughes A., Öberg K. I., Ricci L., The Disk Substructures at High Angular Resolution Project (DSHARP). I. Motivation, sample, calibration, and overview. Astrophys. J. Letters 869, 2 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flock M., Ruge J. P., Dzyurkevich N., Henning T., Klahr H., Wolf S., Gaps, rings, and non-axisymmetric structures in protoplanetary disks from simulations to ALMA observations. Astron. Astrophys. 574, A68 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lichtenberg T., Golabek G. J., Burn R., Meyer M. R., Alibert Y., Gerya T. V., Mordasini C., A water budget dichotomy of rocky protoplanets from 26Al-heating. Nat. Astron. 3, 307–313 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein J. I., Huss G. R., Scott E. R. D., Ion microprobe analyses of carbon in Fe–Ni metal in iron meteorites and mesosiderites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 200, 367–407 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein T., Schachermayer M., Mendez-Martin F., Schöberl T., Rashkova B., Clemens H., Mayer S., Carbon distribution in multi-phase γ-TiAl based alloys and its influence on mechanical properties and phase formation. Acta Mater. 94, 205–213 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chyba C. F., Thomas P. J., Brookshaw L., Sagan C., Cometary delivery of organic molecules to the early Earth. Science 249, 366–373 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kebukawa Y., Nakashima S., Zolensky M. E., Kinetics of organic matter degradation in the Murchison meteorite for the evaluation of parent-body temperature history. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 45, 99–113 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’D. Alexander C. M., Fogel M., Yabuta H., Cody G. D., The origin and evolution of chondrites recorded in the elemental and isotopic compositions of their macromolecular organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4380–4403 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cody G. D., O’D. Alexander C. M., Yabuta H., Kilcoyne A. L. D., Araki T., Ade H., Dera P., Fogel M., Militzer B., Mysen B. O., Organic thermometry for chondritic parent bodies. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 272, 446–455 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano H., Kouchi A., Tachibana S., Tsuchiyama A., Evaporation of interstellar organic materials in the solar nebula. Astrophys. J. 592, 1252–1262 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remusat L., Derenne S., Robert F., Knicker H., New pyrolytic and spectroscopic data on Orgueil and Murchison insoluble organic matter: A different origin than soluble? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 69, 3919–3932 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollmer C., Pelka M., Leitner J., Janssen A., Amorphous silicates as a record of solar nebular and parent body processes—A transmission electron microscope study of fine-grained rims and matrix in three Antarctic CR chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 55, 1491–1508 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riebe M. E. I., Foustoukos D. I., O’D. Alexander C. M., Steele A., Cody G. D., Mysen B. O., Nittler L. R., The effects of atmospheric entry heating on organic matter in interplanetary dust particles and micrometeorites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 540, 116266 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manara C. F., Robberto M., Da Rio N., Lodato G., Hillenbrand L. A., Stassun K. G., Soderblom D. R., Hubble Space telescope measures of mass accretion rates in the Orion nebula cluster. Astrophys. J. 755, 154 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.N. I. Shakura, R. A. Sunyaev, Black holes in binary systems: Observational appearances, in X- and Gamma-Ray Astronomy (1973), p. 155.

- 41.Flaherty K., Hughes A. M., Simon J. B., Qi C., Bai X.-N., Bulatek A., Andrews S. M., Wilner D. J., Kóspál Á., Measuring turbulent motion in planet-forming disks with ALMA: A Detection around DM tau and nondetections around MWC 480 and V4046 Sgr. Astrophys. J. 895, 109 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baraffe I., Homeier D., Allard F., Chabrier G., New evolutionary models for pre-main sequence and main sequence low-mass stars down to the hydrogen-burning limit. Astron. Astrophys. 577, A42 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Öberg K. I., Boogert A. C. A., Pontoppidan K. M., van den Broek S., van Dishoeck E. F., Bottinelli S., Blake G. A., Evans N. J. II, The Spitzer ice legacy: Ice evolution from cores to protostars. Astrophys. J. 740, 109 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuga M., Marty B., Marrocchi Y., Tissandier L., Synthesis of refractory organic matter in the ionized gas phase of the solar nebula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7129–7134 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tartese R., Chaussidon M., Gurenko A., Delarue F., Robert F., Insights into the origin of carbonaceous chondrite organics from their triple oxygen isotope composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 8535–8540 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.B. T. Draine, B. S. Hensley, The dielectric function of “Astrodust” and predictions for polarization in the 3.4μm and 10μm features. arXiv:2009.11314 [astro-ph.GA] (23 September 2020).

- 47.A. P. Jones, Dust evolution, a global view: IV. Tying up a few loose ends. arXiv:1804.10628 [astro-ph.GA] (27 April 2018).

- 48.Fomenkova M. N., On the organic refractory component of cometary dust. Space Sci. Rev. 90, 109–114 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson D. E., Bergin E. A., Blake G. A., Ciesla F. J., Visser R., Lee J.-E., Destruction of refractory carbon in protoplanetary disks. Astrophys. J. 845, 13 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klarmann L., Ormel C. W., Dominik C., Radial and vertical dust transport inhibit refractory carbon depletion in protoplanetary disks. Astron. Astrophys. 618, 10.1051/0004-6361/201833719, (2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’D.Alexander C. M., Cody G. D., De Gregorio B. T., Nittler L. R., Stroudc R. M., The nature, origin and modification of insoluble organic matter in chondrites, the major source of Earth’s C and N. Chem. Erde-Geochem. 77, 227–256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prescher C., Dubrovinsky L., Bykova E., Kupenko I., Glazyrin K., Kantor A., Cammon C. M., Mookherjee M., Nakajima Y., Miyajima N., Sinmyo R., Cerantola V., Dubrovinskaia N., Prakapenka V., Rüffer R., Chumakov A., Hanfland M., High Poisson’s ratio of Earth’s inner core explained by carbon alloying. Nat. Geosci. 8, 220–223 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mashino I., Miozzi F., Hirose K., Morard G., Sinmyo R., Melting experiments on the Fe-C binary system up to 255 GPa: Constraints on the carbon content in the Earth’s core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 515, 135–144 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fei Y., Brosh E., Experimental study and thermodynamic calculations of phase relations in the Fe-C system at high pressure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 408, 155–162 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lord O. T., Walter M. J., Dasgupta R., Walker D., Clark S. M., Melting in the Fe-C system to 70 GPa. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 284, 157–167 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vočadlo L., Brodholt J., Dobson D. P., Knight K. S., Marshall W. G., Price G. D., Wood I. G., The effect of ferromagnetism on the equation of state of Fe 3 C studied by first-principles calculations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 203, 567–575 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ono S., Mibe K., Magnetic transition of iron carbide at high pressures. Phys. Earth Planet. In. 180, 1–6 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mookherjee M., Elasticity and anisotropy of Fe3C at high pressures. Am. Mineral. 96, 1530–1536 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Litasov K. D., Sharygin I. S., Dorogokupets P. I., Shatskiy A., Gavryushkin P. N., Sokolova T. S., Ohtani E., Li J., Funakoshi K., Thermal equation of state and thermodynamic properties of iron carbide Fe3C to 31 GPa and 1473 K. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 5274–5284 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chi H., Dasgupta R., Duncan M. S., Shimizu N., Partitioning of carbon between Fe-rich alloy melt and silicate melt in a magma ocean—Implications for the abundance and origin of volatiles in Earth, Mars, and the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 139, 447–471 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/14/eabd3632/DC1