Abstract

DNA’s programmable, predictable, and precise self-assembly properties enable structural DNA nanotechnology. DNA nanostructures have a wide range of applications in drug delivery, bioimaging, biosensing, and theranostics. However, physiological conditions, including low cationic ions and the presence of nucleases in biological systems, can limit the efficacy of DNA nanostructures. Several strategies for stabilizing DNA nanostructures have been developed, including i) coating them with biomolecules or polymers, ii) chemical cross-linking of the DNA strands, and iii) modifications of the nucleotides and nucleic acids backbone. These methods significantly enhance the structural stability of DNA nanostructures and thus enable in vivo and in vitro applications. This study reviews the present perspective on the distinctive properties of the DNA molecule and explains various DNA nanostructures, their advantages, and their disadvantages. We provide a brief overview of the biomedical applications of DNA nanostructures and comprehensively discuss possible approaches to improve their biostability. Finally, the shortcomings and challenges of the current biostability approaches are examined.

Keywords: DNA nanostructures, Biostability, Biomedical applications, DNA nucleases

1. Introduction

As a natural biopolymer, DNA molecules store genetic information [1]. Chargaff’s base-pairing rule (the amount of adenine equals thymine, and the amount of guanine equals cytosine) along with biodegradability, biocompatibility, programmability, and predictability inspired the development of structural DNA nanotechnology through the sequence-based assembly of DNA molecules [2–5]. The high affinity of complementary sequences allows for the construction of well-organized architectures via programmable self-assembly of DNA. A pioneer in the field, C. Ned. Seeman and colleagues created the first four-way junction by combining partially complementary DNA strands that then expanded to wellordered extended DNA junctions. They created several molecular entities through the cohesion of the branched DNA molecules with sticky ends (Fig. 1a) [6]. Self-assembly of the more complex nanostructures required a series of complementary base pairing and ligation assays. The fabrication process is sensitive to the ratio of the oligonucleotides and would break down in multiple reactions and purification steps that collectively lower the final yield. To address the misfolding and low yield in the fabrication of complex structures, Rothemund introduced a simple one-pot assembly strategy by folding a long single-stranded DNA scaffold using a set of short oligonucleotides (staples) (Fig. 1b). Rectangles, triangles, five-pointed stars, and smile symbols were among the successful 2D DNA nanostructures created following this approach [7,8]. It is noteworthy that, the introduction of scaffolded DNA origami enables the fabrication of various complex 3D structures, such as molecular containers of tetrahedron geometry or space-filling multilayer objects [9,10]. The main strategies in the transition from 2D to 3D using scaffolded DNA origami rules are based on honeycomb, square, and hexagonal lattices. Detailed design principles of the lattices are described in ref [10]. Differential characteristics of these lattice types include the difference in the number of possible neighboring helices and the interval spaces between connecting crossovers. Therefore, lattices of each type provide the framework for different applications. For example, a square lattice is a better design option for fabricating compact rectangular structures with flat edges [9].

Fig. 1.

Classification of DNA nanostructures. a) 2D lattice-like DNA nanostructure forms through sticky-end cohesion of Four-way junction DNA with sticky ends. Reprinted from [6], Copyright (2023), with permission from Elsevier. b) DNA origami [8]. c) DNA tetrahedron (left). Modified and reproduced from ref [58] with permission, DNA cage (right). Modified and reproduced from ref [16] with permission. d) different helix bundle nanotubes built from the alignment of DNA duplexes to form channel-like structures. Modified and reproduced from ref [33] with permission. Copyright (2019) Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. e) Spherical nucleic acid-nanoparticle conjugate [59]. f) Tripodna, tetrapodna, hexapodna, and octapodna DNA polypods. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [47]. Copyright (2012), American Chemical Society. g) pH and temperature-responsive hydrogel for drug delivery. Modified and reproduced from ref [30] with permission. Copyright (2020), American Chemical Society.

Improvements in computational tools, design strategies, and control over the structure’s functionality enable the creation of more intricate 2D and 3D DNA nanostructures, translating the technology toward nanofabrication and biomedical applications [11]. DNA honeycombs [12], DNA origami polyhedrons in tripods [13], barcoded DNA origami [14], self-folding amphiphilic DNA origami [15], and many programmable cage-like structures with molecular gates [16,17] are some examples of DNA nanostructures. The artificially designed DNA nanostructures with sophisticated surface features provide a robust and versatile framework for functionalization with various drugs, imaging dyes, probes, and chemicals [18]. The convenience of DNA functionalization makes DNA nanostructures one of the most favorable candidates with therapeutic and diagnostic potential.

Although recent progress in design, fabrication, and functionalization strategies have greatly expanded the efficacy of DNA nanostructures for diverse applications, the transition from bench to bedside still requires many improvements. The limits are primarily due to the vulnerability of DNA nanostructures to heat denaturation, enzymatic degradation, and structural disassembly in biological environments [19]. Therefore, the biostability and structural integrity of the DNA nanostructures should be the main concerns in biomedical research.

2. Classification of DNA nanostructures

Numerous DNA nanostructures with predefined geometries, sizes, and shapes have been designed and fabricated for a wide range of applications at the interface with biology, material and electronic sciences [20,21]. The main categories of DNA nanostructures are DNA cages, particles, polypods, and hydrogels (Fig. 1) [22,23]. The following is detailed information on each sort of DNA nanostructure from the perspective of the design, main features, and applications.

2.1. DNA cages

Cage-like polyhedral structures are constructed from the self-assembly of synthetic DNA oligonucleotides. DNA origami, DNA tile, and DNA wireframe are typical DNA cages. Cage-like DNA nanostructures are multifunctional and programmable 3D structures built from the pleated layers of double-helical DNA closely packed to square or honeycomb lattices. DNA double-helical molecules connect to neighbors by antiparallel strand cross-overs with defined intervals depending on the type of lattice [9,10]. Ease of encapsulation of drugs, dyes, and small biomolecules in their interior cavities and surface functionalization demonstrate the potential for “space-time” controlled biomarker sensing (diagnostic) and payload delivery (therapeutic) [24]. A cage-like DNA logic platform was used for sensing several cancer-related miRNAs in biological samples. In the presence of target miRNAs, these short oligos compete to bind the locked oligos and open the structure (Fig. 1c) [25]. Using the same approach, Tang et al. designed an aptamer-functionalized DNA cage sensitive to malaria plasmodium falciparum lactate dehydrogenase protein. Aptamer-target binding results in the opening and dissolving of the structure [26]. Structural modification of the DNA cage enhances the properties of the nanostructure through the gain of novel characteristics and capabilities. Duanghathaipornsuk et al. (2020) have shown higher binding stability and greater specificity and sensitivity for targets in the hybrid DNA cage-aptamer (hemoglobin or glycated hemoglobin high-affinity aptamer-integrated cages) [27].

The wireframe DNA cages are broadly categorized into two distinct polyhedrons and nanotubes. DNApolyhedrons are scaffold-free wireframe structures enabling the production of arbitrary 3D shapes without the routing and size restrictions associated with scaffold strands in DNA origami [28]. High permeability from biological membranes, biostability, biocompatibility, convenient functionalization, and lack of cytotoxicity make DNA tetrahedral the most promising nanodevice for biomedical research in vitro and in vivo [2]. Confocal microscopy and Förster resonance energy transfer experiments have confirmed the high permeability of the fluorescently labeled DNA tetrahedral nanostructures across the cell membrane, cytoplasmic localization, and structural intactness up to 48 hours in human embryonic kidney cells [29]. Progressively, DNA tetrahedrons fabricate as a carrier of complex payloads, including aptamer, peptide nucleic acid, and small molecule drugs, to live cells for antibacterial and anticancer therapies [30–32]. Although DNA tetrahedral represents a high potential for drug delivery and biosensing, these nanostructures are sensitive to the size and spatial structure of the payload. For instance, DNA tetrahedral delivery systems are ineffective for transporting long nucleic acids with complex secondary structures [30].

Membrane channels and cytoskeleton filaments (e.g., actin and myosin) are biologically natural nanotubes that participate in cell-cell communications, cell membrane and intracellular transport, and cellular shape. The emergence of bottom-up assembly enables biomimetic DNA nanotubes to play a role as artificial membrane channels, delivery tools, and bioreactors (Fig. 1d) [33]. In vitro fabrication of DNA nanotubes includes either aligning DNA double helices in a circular orientation or closing DNA rectangular lattice to form channel-like tubes [33]. Figure 1d demonstrates the higher-ordered multilayer DNA nanotubes in honeycomb packing assembled from 6-helix bundle building blocks. Using DNA nanotubes to deliver CpG immunostimulatory motifs showed strengthened drug-binding capability, enhanced immune activation, and reduced cytotoxicity compared to liposome drug delivery [34].

2.2. Nucleic acid-nanoparticle hybrid

Spherical nucleic acids are 3D core-shell nanoparticles that surround the solid or hollow core with dense arrays of single-stranded nucleic acids (Fig. 1e). Spherical nucleic acids are an excellent adaptable tool for bioimaging and therapeutics due to the high cellular uptake independence of auxiliary proteins, biocompatibility, cellular stability, and nontoxicity. Radially oriented surrounding nucleic acids show high affinity for the ligands on cell membranes and improve tissue-specific targeting. Moreover, they will increase the surface area and create abundant drug/dye binding sites [35–38]. The high loading capacity enables the functionalization with various moieties for biosensing, diagnosis, and therapeutic purposes. Spherically arrayed siRNA targets the Bcl2Like12 mRNA, successfully passes through the blood-brain barrier, and induces apoptosis to prevent glioblastoma multiforme lethal malignancy [39]. Spherical arrays of anti-interleukin-17A receptors on liposomes were recruited to change the clinical manifestations of psoriasis through the blockade of the interleukin-17 pathway [40].

Hybrid nucleic acid-nanoparticles combine molecular recognition and programmability features of DNA with the efficient properties of nanoparticles. Different hybrid DNA nanostructures have emerged depending on the types of nanoparticles, including DNA-inorganic nanoparticles, DNA-lipid, and DNA-polymer hybrid nanosystems [41]. DNA-gold nanoparticles complex combines the high affinity and specificity of the DNA for a specific ligand with the optical features of the gold nanoparticles in biosensor development and drug delivery [42]. For instance, hybrid DNA-gold nanoparticles functionalized with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibodies specifically target the breast cancer cells for co-delivery of the doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil anticancer drugs [43]. DNA-calcium phosphate nanoparticles are biocompatible structures with high cellular uptake. These hybrid structures have shown strong immunological response, high transfection efficiency, and immunomodulatory function [44,45].

2.3. Polypod DNA nanostructures

Multibranched DNA nanostructures provide higher biostability than single-stranded DNA as well as higher binding sites for drugs, dyes, and therapeutic nucleic acids. The polypod DNA nanostructures are more flexible than DNA tetrahedrons, given that, more available for transporting drugs into hard-to-reach tissues [46,47]. The main types of polypod DNA nanostructures are DNA polypodna and DNA centipede. It’s fascinating that polypodnas with different Y- or X-shapes or dendrimers resembling multi-branched structures are immunostimulatory (Fig. 1f). They greatly increase the production of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 and their significant immunostimulatory action is supported by the design of CpG-containing polypodnas. Increasing the number of pods will reduce serum stability while improving cell permeability [47,48]. On the other hand, inspired by the centipede, saturation of the DNA backbone with arrays of high-affinity aptamers for specific ligands on target cells introduced DNA nanocentipede structures. Small-molecule drugs (e.g., doxorubicin) and intercalating agents (e.g., imaging dyes) carried by the DNA backbone would release to the site of action by specific hybridization of the aptamers with target ligands on the desired cells/tissues. The dual functionality of the DNA nanocentipedes overcomes the systemic adverse effects of traditional oncology treatments by targeted drug release [49].

2.4. DNA hydrogels

DNA hydrogels are sponge-like networks made up of chemically cross-linked DNA molecules, ligated branched DNA motifs (e.g., X- or Y-shape motifs), bird-nest-like microstructures, or hybrid DNA/nanoparticles. Hydrophilic DNA molecules actively interact with water and create gel-resemblance supramolecular structures. Pure DNA (All-DNA) hydrogels form either by parallel ligation reactions of DNA motifs or amplification of the DNA by a particular polymerase (phi29). The latter is based on rolling circle amplification and multiprimed chain amplification of a circular DNA template to create a bulk entangled DNA hydrogel (Fig. 1g). The huge, branched DNA hydrogel was successfully examined as a drug delivery tool in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, DNA hydrogel follows the preload rule in which 100% of the drugs are loaded into the hydrogel structure pre-transition to the gel state. Preloading also improves the drug loading efficiency and eliminates the payload size restriction. Diverse biological molecules, including RNA, DNA, antisense transcripts, aptamers, and even live cells, can encapsulate in the gel structure during gelation [50–54]. Controlled drug release in response to the alterations in the biological microenvironment was the other noticeable observation. In vivo experiment revealed the antitumor effect of the CpG/doxorubicin DNA hydrogel on mice colon26/Luc tumor. Using DNA hydrogels, it is possible to synthesize cell-free proteins, which is one of the most recent advances. This capability brings scientists closer to their ultimate goal of creating artificial cells [50].

Owing to the ease of DNA functionalization, a variety of targeting entities (e.g., antibody, aptamer, siRNA, fluorescent dyes), nanocrystals (nanoclay), and metals (e.g., Au) have been used to establish robust and versatile platforms to minimize the drawbacks of the current approaches in biomedical research. DNA-clay hybrid hydrogels showed strengthened protection of DNA against enzymatic digestion. Furthermore, these hydrogels more efficiently respond to external stimuli and are able to synthesize cell-free proteins when exposed to the gene expression machinery in vitro [50]. In the other types of hybrid DNA hydrogels, DNA motifs have been attached to the DNA backbone to see the synergistic effects of the DNA and decorative tags on sensing and therapeutic potentials. For example, the DNA hydrogel polypod with surrounding arrays of CpG motifs exhibits enhanced immunomodulatory activity and tumor-suppressing effects compared to the naked CpG motifs [55].

DNA hydrogels are miniaturized factories capable of producing proteins and metal nanoparticles as cofactors for catalytic processes. We previously explained the art of designing All-DNA hydrogels to express cell-free proteins. DNA hydrogels uptake and concentrate gold ions to produce thousands of highly concentrated stable gold nanoparticles (2–3 nm size) throughout the hydrogel scaffold. These hybrid hydrogels behave as a bioreactor to promote chemical reactions (e.g., hydrogenation of nitrophenol) [56]. Walia et al. have established the significance of DNA hydrogels as an extracellular matrix mimic. They have demonstrated that cells can successfully adhere to and spread across the DNA hydrogel scaffold. In addition, they assessed the overexpression of membrane receptors, the increased endocytosis of membrane-binding ligands, and the invasion of grafted cells in the presence of a hydrogel matrix. DNA hydrogel facilitates 3D cell culture and simulation of in vivo environments to better understand the behavior of cells and intracellular processes [57]. Despite the promising potentials of DNA hydrogels for biomedical applications, the high cost of oligonucleotide synthesis and the low yield of complete hydrogel on large scales should be addressed. Furthermore, there is a lack of data on the biostability of DNA hydrogels under physiological circumstances, their circulation lifetime, and their interactions with blood proteins [57].

3. Biomedical applications of the DNA nanostructures

3.1. Drug delivery and gene delivery

Conventional drug delivery systems are often inefficient either because a big portion of the drugs is digested by enzymes or if reach the target position unable to pass through the biological barriers to release adequate amounts of drugs for efficient therapeutic effects. Furthermore, premature leakage of the drugs along the designed path to the target sites led to a potential risk of toxicity and adverse side effects on healthy tissues. Therefore, alternative drug delivery systems are on demand to not only address the drawbacks but also possible co-delivery of multiple drugs to improve the therapeutic effects [60]. Taking advantage of the unique features of the DNA molecules including programmability, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and cell permeability, many DNA nanocarriers were developed for “space-time” controlled drug release (Fig. 2a) [41,46,61]. Cancer cells have high ATP concentrations, and some express mucin receptor 1 on the cell membrane. Accordingly, a core-shell nanostructure carries doxorubicin in the core, and mucin receptor 1, ATP1, and ATP2 aptamers on the surface are able to invade mucin receptor 1 positive cancer cells with little systemic cytotoxicity [62].

Fig. 2.

Examples of drug delivery. a) Co-delivery of the anticancer doxorubicin and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides to cancer cells. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [65]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society. b) targeted delivery of siRNA to glioma cells [64].

Nucleic acid therapeutics include antisense oligonucleotides, antagomir, RNA sponge, miRNA, and siRNA, which are newly emerged drugs with long-lasting curative effects by targeting the genetic components of the cells. Low biostability and short half-life due to enzymatic degradation, lack of tumor targeting, and low cell uptake are the limiting factors in their biomedical applications. Convenient loading of the therapeutic oligonucleotides with pre-assembled DNA nanostructures increases their stability, target-oriented delivery, and cell uptake (Fig. 2b) [63]. One example is the induction of apoptosis through targeting the survivin gene by survivin-specific siRNA in glioma cancer cells. The aptamer-modified siRNA-loading DNA tetrahedron was efficiently uptake by the target cells through aptamer hybridization and released siRNA in intracellular space. Downregulation of the mRNA and its protein counterpart confirmed the successful targeting of the survivin gene in the target cells [64]. The structures tested for each application, the functional moiety and target molecules, and the outcomes of the applied tools are summarized in Table 1.

Table1.

Summarized biomedical applications of DNA nanostructures

| Biomedical application | Structure | Functional moiety | Target | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug delivery/Gene delivery | Core-shell nanostructure [62] | Core: Doxorubicin Surface: mucin 1 receptor, ATP1, and ATP2 aptamers | Mucine 1 receptor on cancer cell lines | Higher tumor accumulation and tumor growth inhibition compared to free doxorubicin |

| DNA tetrahedron [64] | Survivin-specific siRNA | Glioma cancer cell lines | Increased apoptosis and reduced expression of survivin | |

| DNA tetrahedron [65] | Doxorubicin; CpG oligodeoxynucleotides; and AS1411 aptamer | Cancer cell lines | Increase doxorubicin cell uptake; pH-responsive drug release in cancer cells |

|

| Biosensing | Aptamer-DNAzyme hairpin hybrid structure [66] | Aptamer | AMP molecule and lysozyme | Improve detection efficiency compared to the labeled hairpins |

| Molecular beacon [70] | miRNA-21-5p complementary sequence | miRNA-21-5p in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from non-small lung cancer patients | 100% sensitivity and 55.3% specificity for the target | |

| DNA octahedron [71] | AS1411 aptamer Thymidine kinase 1 and N-acetyl galactosamine mRNA complementary sequences | Thymidine kinase 1 and N-acetyl galactosamine mRNA in MCF-7 cell lines | Simultaneous detection of both target mRNAs with high specificity and sensitivity | |

| Locked tetrahedral DNAzyme, Active tetrahedral DNAzyme [72] | miRNA-21 inhibitor | miRNA-21 | High sensitivity (0.77 pM) and high specificity (one base mismatch discrimination) | |

| Bioimaging | Gold nanoparticles [75] | VCAM-1 antisense sequence with hairpin DNA | VCAM-1 mRNA in mouse laser-induced choroidal neovascularization | Sensitive mRNA imaging |

| DNA triangular prism [76] | Hairpin probes, AS1411 aptamer, Cy3 labeled strand | miRNA-155 and miRNA-21 tumor biomarkers in MCF-7 cells | Highly sensitive and specific multiplex bioimaging tool | |

| Y-DNA@Cu3(PO4)2 and Y-DNA@CuP hybrid nanoflowers [76] | Thymidine kinase mRNA complementary sequence | HeLa, HepG2, LO2, and MCF-7 cell lines | Highly sensitive and specific imaging tool with a limit of detection of 0.56 nM | |

| DNA tetrahedron [77] | AS1411 aptamer; FAM and CY5-labeled strands | miRNA-21 in MCF-7, A375, and A549 cancer cell lines | The high detection rate of the target miRNA-21 | |

| Triangular DNA [78] | AQ4 intercalating drug and photoacoustic contrast agent (PAI probe) |

in vitro: HeLa/ADR, HeLa cell lines in vivo: BALB/c female nude mice |

Sensitive intracellular screening of the drug | |

| Engineered switchable aptamer micelle flare [79] | Aptamer-switchable probe- diacyllipid chimer | ATP molecules in HeLa cell lines | Highly sensitive and specific detection and intracellular tracking of the target |

3.2. Biosensing

Hua et al. comprehensively reviewed the drawbacks of conventional biosensors and characterized DNA-based biosensors as a promising new generation of smart detecting materials [66]. High production cost, short lifetime due to device degradation, limited target detection range, low sensitivity for the target in a complex sample, which delay the early detection of human diseases, inconsistent results, and low reproducibility due to the influential effects of external factors such as temperature, humidity, pH, and electromagnetic field have attracted attention for the alternative to satisfy these limitations [66]. DNA’s inherent biocompatibility, ease of functionalization, ligand customization, and precise programmability introduced it as a fascinating alternative to conventional biosensors [67]. Smart DNA-based biosensors include functional DNA strand-based, DNA template-based, and DNA hybridization-based biosensors that sensitively and specifically detect their target and produce appropriate signals [66]. The pathological microenvironment is differentiated from the surrounding unaffected tissues and cells by varying in pH, cellular accumulation, a profile of the non-coding RNAs, and extracellular matrix that is defined as disease-state biomarkers [68]. Conformational changes, reorganization, or reconstruction of DNA nanostructures in response to the pathological microenvironment leads to biosensing signals. Therefore, detecting disease biomarkers allows for more accurate diagnosis and personalized therapeutic approaches.

Non-coding RNAs, especially miRNAs and peptides, are the two classes of biomarkers abnormally expressed in many human diseases. However, the shared sequence similarities and low quantities of the miRNAs in the complex biological context necessitate the development of highly sensitive and specific biosensors. DNA biosensors commonly combine the precise recognition behavior of aptamers, molecular beacons, and/or DNAzymes with optic, colorimetric, or electrochemical transducers to interrogate the cellular biomarker signature (Fig. 3a–c) [69]. A molecular beacon probe with a 5’-FAM reporter dye and a 3’-quencher, including a miR-21-5p complementary sequence in the loop region, was utilized to detect the miR-21-5p biomarker in lung cancer samples. This highly sensitive biosensor produces a measurable fluorescent signal proportional to miR-21-5p concentration to differentiate patients in stages I, II, or III of lung cancer [70]. An engineered aptamer-functionalized DNA octahedron that contains two fluorescently labeled recognition strands allows the detection of differentially expressed thymidine kinase 1 and N-acetyl galactosamine mRNAs in cancer cells. The designed aptasensor selectively targets tumor cells and measures the quantity of the tumor-specific mRNAs at nanomolar concentrations (Table 1) [71]. In the other study, Yu et al. fabricated a sensitive dual-function DNA tetrahedron to detect and regulate the miRNA in cells. The DNA tetrahedron serves as a carrier for DNAzyme and its fluorescently labeled substrate and miRNA inhibitor. In its original shape, hybridization of the miRNA inhibitor to the catalytic loop of the DNAzyme maintains the inactive state. In response to miRNA, the miRNA inhibitor-miRNA complex forms, and the DNAzyme activates, leading to cleaving the substrate and emitting the fluorescent signal [72].

Fig. 3.

a) General mechanism of actions of DNA-based biosensors. Modified and reproduced from ref [73]. Copyright (2021) Wiley-VCH GmbH. b) Fluorescently labeled aptamer loaded on DNA octahedron to sense two tumor biomarkers (TK1 mRNA and GalNAc-T mRNA) in tumor cells. The complementary base-pairing of the mRNA with aptamer increases the distance between fluorescent dyes and quenchers and the detecting signal emitted. Adapted with permission from ref [71]. Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society. c) Detection of AMP and lysozyme through conformational changes in the DNAzyme-aptamer hybrid structure. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [66]. Copyright (2009) American Chemical Society.

3.3. Bioimaging

Bioimaging represents a multidimensional visualization of biological components such as cells and intracellular compartments. Interpreting the visualizing signals provides in-depth insight into how biological processes occur in native living systems. Bioimaging modalities have been developed by conjugating fluorescent dyes and nanoparticles to DNA nanostructures to capture images with high spatiotemporal resolution. The combination of bioimaging modalities with aptamer or folic acid improves the sensitivity and cell-internalization features of the bioimaging platforms, respectively (Fig. 4a–b) [74]. Several reviews have already reported on the platforms assembled through the conjugation of gold nanoparticles, DNA origami, DNA tetrahedron, and DNA nanoflowers with fluorescent dyes, aptamers, or hairpin DNAs for the bioimaging of single or multiple miRNAs, mRNAs, or tumor tissues in vitro and in vivo (Table 1) [75–79].

Fig. 4.

Bioimaging using functionalized DNA nanostructures. a) Schematic illustration of DNA micelles encapsulating a target-sensitive molecular beacon aptamer. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [80]. Copyright (2013) American Chemical Society. b) Functionalized DNA tetrahedron for detection of surface nucleolin. Adapted with permission from ref [77]. Copyright (2022) Wiley-VCH GmbH.

4. Stability of DNA nanostructures in biological environments

The stability of DNA nanostructures is crucial for biomedical applications. For example, in drug delivery, the structural integrity of the DNA nanostructures is critical to protect the drugs from harsh physiological environments, minimize potential toxicity, and ensure the efficacy of the drugs at the target sites [81]. In general, environmental factors like pH, enzyme composition, covalent bonding, and ion concentrations significantly impact on the biostability of DNA nanostructures [82,83]. However, the presence of nucleases and low concentration of the cations in biological conditions primarily endangers the structural integrity of DNA nanostructures. Herein, the influences of the threatening factors on DNA nanostructures and the strategies that have been developed to improve the resistance of DNA nanostructure toward nucleases are discussed.

4.1. DNA nanostructures dissociation

The critical point here is to differentiate the requirements for the highly efficient assembly of DNA nanostructure from the optimal condition needed to maintain the stability and integrity of the assembled nanostructure. For DNA molecules to form a tightly packed structure with a certain shape, the negatively charged phosphate backbone must be shielded by cations. Primary experimental studies have revealed that high concentrations of Mg2+ in the folding buffer neutralize the inter-strand repulsion forces to promote highly efficient self-assembly of the DNA nanostructure [21,84]. Mg2+ cations in high concentrations may either interfere with some functionalities of the nanostructure or be incompatible with biological applications [85]. Several other ions can play complementary roles for Mg2+ in the DNA nanostructure assembly, but their binding affinity to DNA may differ significantly. Bednarz et al. have shown the optimal concentrations of monovalent cations (Li+, Na+, K+, Cs+) and divalent cations (Ca2+, Sr2+, Ba2+) for efficient folding of rectangle and triangle DNA nanostructures. AFM imaging confirmed the properly folded structures in the presence of all substituted ions [86]. For further investigation of the functionality of the folded structures, they changed the optimal concentrations of the ions and observed reversible partial structural defects for all the DNA nanostructures. These findings are in accordance with the observation of Martin and Dietz on the successful folding of the multi-layer DNA objects in the presence of a 100-fold higher concentration of Na+ in the Mg-depleted folding buffer [87].

The other step following assembly would be the conditions to maintain the integrity and stability of the folded nanostructures. Hann et al. performed the first investigation on the influence of Mg2+ or its substitution with monovalent cations on the post-assembly stability of the three different DNA nanostructures (6-helix bundle, 24-helix nanorod, and wireframe DNA nano-octahedron). The standard RPMI culture media contains low Mg2+ (0.4 mM) and high monovalent cations. Sensitivity analysis revealed the degradation of DNA nanostructures in a design and time-dependent manner, and only the 6-helix bundle remained intact after 24 h at 37°C [85]. The interpretation of the findings was that Mg2+ promotes conformational changes necessary to overcome the repulsive forces between helices by strongly binding to the DNA minor groove and backbone phosphates, whereas monovalent cations (e.g., Na+) loosely adhere to DNA [88]. Collectively, higher concentrations of monovalent cations compared to divalent cations (especially Mg2+) require screening the repulsive forces between helices in DNA nanostructure. It appears that the high concentrations of monovalent cations in biological systems are insufficient to compensate for Mg2+ deficiency [89]. The size of the DNA nanostructure and the length of the assembled strands are the other decisive factors impacting the biostability of the DNA nanostructures in the presence of varied ionic concentrations. Although small DNA nanostructures exhibit some degree of destabilization in the low-salt concentration media, giant DNA origami are more dramatically influenced by the low salt concentrations [90]. The thermal stability and resistance to low concentrations of Mg2+ in phosphate buffer saline culture media are considerably boosted when longer oligonucleotides are used to assemble the nanostructure. The other observation was that the presence of extended overhangs in the strands of the assembled nanostructure increases the vulnerability to deoxyribonuclease (DNase) and low salt concentration [90].

A year later, Linko et al. performed spin filtration to exchange the Mg2+-containing folding buffer against water to prepare structures for depositing. Surprisingly, they observed the high stability of the DNA nanostructures in water for 14 weeks [91]. Kielar et al. 2018 comprehensively investigated the post-assembly stability of DNA origami in eight different Mg2+-free buffers to explore the reason behind the discrepancies in the studies [92]. In this study, authors mimic the spin-filtration and Mg2+ removal from the Linko study. They found that the stability of DNA nanostructures is influenced by design and buffer compositions. For instance, DNA structures maintained their folded shapes in Mg2+-free Tris buffer while disassembled in Mg2+-free TAE buffer. In the other buffer condition, DNA nanostructures were disrupted in phosphate buffer saline (Na2HPO4). Restoring the buffer by adding high concentrations of NaCl could recover triangle structures but not the 24-helix bundle.

In conclusion, it seems that the secondary interactions of the other components of the buffers, such as EDTA in TAE buffer or HPO42− in phosphate buffer saline with phosphate-bound Mg2+ reduce the efficiency of other cations in overcoming the repulsion forces between DNA molecules. The other observation was the higher affinity of DNA molecules K+ compared to the Na+ ions which reduced the proper concentration of K+ to keep the stability of DNA nanostructures. Previously Chen et al. also demonstrated the disassembly and reassembly of the triangle and rectangle DNA nanostructures in low Mg2+ buffer and restoring the buffer to its original concentration [93]. Apart from thermal annealing of DNA origami in Mg2+-free buffers, the isothermal fabrication of the DNA nanostructures has also been possible in Mg2+-free NaCl buffer [94]. Buffers composing divalent cations (Mg2+ and Ca2+) need more energy to allow the structure reconfiguration to reach equilibrium, while Na+-stabilized base pairing allows the several times of structure reconfiguration to finally form the properly folded structures at room temperature.

4.2. Enzymatic degradation

Nucleases harbor the catalytic site for the hydrolysis of P-O3’ or P-O5’ bonds in the nucleic acids. Nucleases are essential components of the cell’s enzymatic machinery and drive several biological processes such as replication, repair, and recombination. In contrast to their importance in biological systems, nucleases are the primary impediment to in vivo (therapeutic) and ex vivo (diagnostic) applications of DNA nanostructures [95]. To determine the degradation rate of the DNA nanostructures exposed to nucleases, researchers performed nuclease degradation analysis by treating different DNA nanostructures with several nucleases (e.g., DNase I, T7 endonuclease I, T7 exonuclease, E. Coli exonuclease I, lambda exonuclease). DNase I, the most abundant endonuclease in biological fluids, nonspecifically targets both single-stranded and double-stranded DNA molecules. Accordingly, DNase I is the selected endonuclease to investigate the enzyme-induced degradation of DNA nanostructures. Degradation rates in the presence of DNase I are controlled by structural compactness, flexibility and accessibility of the enzyme, and concentrations of enzyme cofactors (e.g., Mg2+, Ca2+) [96]. The type of nuclease is a key factor in the level of degradation.

Castro et al. observed a higher lifetime of the 3D origami structures compared to duplex plasmids when treated with various nucleases such as DNase I and T7 endonuclease I. Unlike endonucleases, no cleavage activity for any of the exonucleases, including T7 exonuclease, E. Coli exonuclease I, and lambda exonuclease was seen on DNA nanostructures [10]. The same degradation pattern concerning the type of the treated enzyme was reported by Gerling et al. [97]. Different levels of degradation have been observed on paranemic DNA by exonuclease V, T7 exonuclease, and T5 exonuclease. There are many examples of the DNase I treatment of DNA nanostructures for stability tests that are explained in detail in the following sections [97,98,107,99–106]. The other endonuclease that was recently studied for the biostability of the folded DNA nanostructures is called DNase II. Evolutionary, DNase II is mostly found in higher eukaryotes and a few genera of bacteria. DNase II is a lysosomal enzyme and optimally catalyzes the reaction in very low acidic pH in the absence of ionic cofactors [108]. The structure of the DNA molecule determines the optimum cleavage by DNase II, and then the enzyme cleaves the purine-rich strand stronger than the complementary one [108]. Wamhoff et al., for the first time investigated the degradation of DNA nanostructures by DNase II and how minor groove binders could protect DNA from enzymatic digestion (see section 5.3.) [105].

5. Optimization of DNA nanostructures’ stability in biological environments

DNA nanostructures show remarkable nuclease degradation resistance compared to naked DNA. Keum and Bermudez, for instance, showed three times more stability for DNA tetrahedron rather than linear double-stranded DNA in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum and DNase I. They discovered that this higher enzymatic degradation resistance is size- and shape-independent [109]. Mei incubated several DNA origamis with cell lysates and compared the behavior of the DNA structures with single-stranded M13 genome and double-stranded phage λ DNA on the agarose gel. DNA origamis remained intact and easily isolated from cell lysate after 12 hours of incubation [110]. The findings of the Walsh et al. experiment have demonstrated the stability of the cage-like DNA nanostructures for more than 48 hours following cellular transfection [29]. Conformational hindrance for the nucleases, particularly, DNase I, to reach the recognition sequences in the compact 3D nanostructures partly explains the greater integrity of these structures against nucleases compared to naked duplex DNA molecules [109,111]. As mentioned earlier, the complexity of the situation would be increased by the influence of additional factors on the stability of DNA nanostructures, such as superstructure, temperature, size, and topology [98]. This would highlight the need for a deeper review of the behavior of the DNA nanostructures in biological environments.

To increase the stability of the DNA nanostructures in harsh physiological conditions, numerous strategies have been devised to impact DNA durability in biological environments. The capacity of the DNA molecule to interact with a variety of functional groups, including lipid bilayers [112], proteins [113], peptides [114], and polymers [115], is one of its intriguing properties. These moieties protect the DNA and lessen the exposure to the biological setting. Several other effective solutions were employed to overcome the limited stability of DNA nanostructures in biofluids or cells, which will be covered in more detail.

5.1. Protective coating of the DNA nanostructures

Various positively charged species, such as proteins and protein conjugates, polymers, polyamines, and cationic polysaccharides, have been used to protect DNA from dissociation and degradation in harsh physiological conditions. Polyamines (e.g., spermine [88], spermidine [116], oligoarginine [117], oligolysine [88,114], and polyethyleneimine [118]) interact with DNA electrostatically through amine-phosphate bonding. Despite their protective potential, most polyamine-functionalized DNA nanostructures exhibit structural deformation, aggregation, and diminished functionality. Oligolysine preserves the structural integrity of the DNA nanostructures with no evidence of deformation but little aggregation at low Mg2+ concentrations. Ponnuswamy et al. have verified the protective effect of oligolysine against dissociation at low Mg2+ concentration by functionalizing nine DNA nanostructures of various sizes, geometries, and shapes. Likewise, they have observed the slight protection of the oligolysine-coated DNA nanostructures in response to nuclease treatment (Fig. 5a) [114].

Fig. 5.

Protective coating of DNA nanostructures. a) Schematic representation of the fate of naked and polyethylene glycol-oligolysine-functionalized DNA nanostructure in physiological conditions (low salt, 10% fetal bovine serum). Oligolysine protects DNA nanostructure dissociation, and polyethylene glycol-oligolysine completely protects DNA nanostructure in physiological conditions [114]. Copyright (2017). b) Schematic represents the sensitivity of DNA to Mg2+-depleted media and the presence of nucleases. Cationic polymers stabilize DNA nanostructures from dissociation and degradation in physiological mimic conditions. Reproduced from Ref [118] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. c) Virus envelope mimic (lipid-DNA conjugate) protects DNA nanostructures from harsh physiological conditions to deliver their cargo to the target sites. Reprinted with permission from ref [112]. All rights reserved. d) Bovine serum albumin-dendron (BSA-G2) protects the 60-helix bundle from degradation in DNase I-rich media. These conjugates are efficiently uptake by cells and diminish immune responses. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [107]. Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society.

Polyethylene glycol is a proper conjugate to circumvent the aggregation tendency of the oligolysine-coated DNA nanostructures [119]. Polyethylene glycol-oligolysine co-polymer avoids aggregation and interferes with the nucleases to interact with DNA in cutting sites. The fabrication of polyethylene glycol-oligolysine-coated DNA nanostructures led to increased cell uptake with no cytotoxicity or interference in biological processes. Regarding the above features, polyethylene glycol-oligolysine offers a potent functionalization moiety to get around the constraints of DNA nanostructures for in vivo therapeutic and diagnostic applications[114,119]. The other breakthrough in the stability field happened with the development of coated DNA nanostructures (different shapes and sizes) with glutaraldehyde cross-linked oligolysine-polyethylene glycol co-polymer. This innovative strategy noticeably (~ 100,000-fold and 250-fold increase compared to bare and non-crosslinked polyethylene glycol-oligolysine coated respectively) improved DNase I degradation resistance as well as cell uptake [120]. In all the above-mentioned experiments, polyethylene glycol envelope forms around the DNA nanostructure through electrostatic interaction with negatively charged phosphate groups. In contrast, Knappe et al. developed a new functionalization platform for covalent bonding of functional moieties such as polyethylene glycol to compare the protective significance of two modes of interactions. 5’-termini covalently PEGylated DNA-Virus-like particle resists nuclease degradation for a greater amount of time than the bare structure, but this improvement was inferior to the expected protection provided by electrostatic polyethylene glycol coating. These findings may emphasize the necessity of full-coverage coating of DNA nanostructures to avoid nuclease accessibility to DNA [121].

Polyethyleneimine, in combination with DNA nanostructures, forms polyplexes with great biostability. Ahmadi et al. investigated the behavior of polyethyleneimine -DNA origamis of various shapes and sizes in biologically mimic settings. To this end, unassembled and assembled DNA wireframe, nanorod, and nanobottle were applied in Mg-zero buffer (Tris, EDTA, NaCl), the culture media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and nuclease-rich media. Unassembled structures completely degraded within several hours, whereas assembled structures remained intact in low-salt buffer, 10% fetal bovine serum culture media, and nuclease-rich conditions for a long time (Fig. 5b) [118].

The unique properties of phthalocyanine, including strong thermal and chemical stability, design flexibility, and electrochemical capabilities have attracted interest in coating DNA with this positively charged pigment [122]. When DNA is electrostatically coupled to the porphyrin-like pigment in phthalocyanine, it acquires favorable properties such as improved biocompatibility and bioavailability [123], as well as an increased sensitivity for the complementary sequence in the pool of diverse sequences [124]. Many modified forms of phthalocyanine in complex with Cobalt (II), Fe (II) [125] (Kuznetsova et al., 2008), and Zn [123] were created for diverse applications. Because of greater resistance to enzymatic degradation, the hybrid Zn phthalocyanine-6-helix bundle nanostructure withstands a considerably longer time in circulation [123]. An innovative structure called a Janus-type phthalocyanine-coated 60-helix bundle, as well as an 80-helix bundle, were examined for stability in a biological environment. The structure contains Zn phthalocyanine on one side to promote electrostatic coupling to DNA origami and water-soluble, inert, and biocompatible triethylene glycol chains on the other side. Combining these features improves this new structure’s stability in physiological conditions [126].

Inspired by viruses’ approach to protect themselves from immune recognition, several virus-mimicking DNA protective coating approaches have been developed in the last few years. For instance, Perrault et al. surrounded a DNA nano-octahedron with lipid-bilayer shells to address the nuclease vulnerability and immunogenicity of DNA nanostructures in biomedical applications. The lipid-bilayer envelope protects the DNA structure significantly from nuclease degradation, reduces immunogenicity, and increases the half-life in the in vivo experiment in mice (Fig. 5c) [112]. It is supposed that the interaction of the viral proteins with DNA molecules in origami occupies the nuclease recognition sequences and interferes with the enzyme activity. Julin et al. not only introduced a strategy for fabricating DNA-lipid hybrids but also supported the improved nuclease resistance of lipid-encapsulated DNA nanostructures [127]. Proteins are the other interesting macromolecules for the protective coating of DNA nanostructures due to the possibility of high-yield production through recombinant gene expression, engineering by fusing various functional domains, and self-assembly properties. Hernandez-Garcia et al. produced a recombinant protein in yeast comprising a DNA-specific binding domain and long random coil polypeptide. The protein specifically coats the DNA through self-assembly and protects DNA from nuclease degradation. Interestingly, coating using this recombinant protein is compatible with other functional groups to interact with DNA and preserve the structural characteristics of the target DNA. The recombinant protein showed affinity to single-stranded and double-stranded DNA in liner and circular configuration as well as higher ordered DNA origami [128].

Human serum albumin, the most abundant protein in serum, is known for its prolonged half-life in blood circulation and high capacity for binding to diverse ligands. Because of the strong affinity of human serum albumin for fatty acids, a dendritic alkyl structure resembling fatty acids was synthesized as a human serum albumin ligand. Dendritic DNA comprises a nucleic acid strand bound to the long carbon chains ending with an alkyl group. Bound human serum albumin-dendritic DNA was substantially more stable than unmodified dendritic DNA in culture media-containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Furthermore, it has been observed that the substitution of the building DNA molecules of the DNA cage with dendritic DNA and decoration with human serum albumin significantly enhances the stability and circulation half-life of the DNA cage as a drug carrier in vivo [129]. Auvinen et al. have generated a protein-dendron conjugate containing bovine serum albumin as a protein component. Dendron adheres directly to brick-like DNA origami (60-helix bundle) through electrostatic interactions between NH2-phosphate groups. Coating DNA with bovine serum albumin effectively prevents DNA origami digestion by DNase I. Additionally, this coated structure showed less immunological stimulation and improved cellular uptake (Fig. 5d) [107].

Rather than proteins, peptidomimetics and especially Peptoids or N-substituted oligomers, demonstrated wide potential applications in biomedical and biotechnological research. Peptoids and peptides share the same backbone, while the side chains in peptoids shift from α-carbon to amide-nitrogen. This simple chemical change in the structure enables the generation of a large library of peptoids with sequence-dependent affinity to a specific protein or antibody and thereby actively recruited in drug discovery. Moreover, peptoids showed better solubility, cell uptake, and stability against proteolytic cleavage compared to peptides. These features along with low synthesis cost and designable sequence, attracted scientists’ attention to investigate the protective strength of peptoids against nucleases [130,131]. To this end, Wang et al. rationally designed nine different peptoids from different ordering of positively charged N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine (Nae) and neutral N-2-(2-(2- methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethylglycine (Nte) monomers. [102]. The organization of the monomers in brush or block shapes influences the interaction of peptoids with DNA. Coating of the double-stranded DNA with designed peptoids primarily elucidated the influence of the coating on the thermal stability of DNA with no further sign of structural changes. Peptoids’ high affinity for DNA was shown to be sequence- and structure-independent. Replications of all the stability tests on a DNA octahedron demonstrated improved thermal stability, nuclease (DNase I) resistance, and structural integrity in various buffer compositions including Mg-depletion or phosphate buffer saline with low magnesium concentrations [102].

Chitosan is a naturally occurring cationic polysaccharide comprised of a random distribution of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. Chitosan is gaining huge interest as a non-viral gene delivery carrier due to its biocompatibility, low cytotoxicity, negligible immunogenicity, availability, and biodegradability [132,133]. DNA binding to chitosan undergoes conformational changes from relaxed B-form to compact A-form [134,135]. The pH-dependent interaction of DNA with chitosan ensures efficient targeted gene delivery at physiological pH (~ 7.4) [135]. Although the plasmid DNA’s intrinsic features make it an ideal carrier for small molecule medications and nucleic acid therapeutics, it is extremely sensitive to nucleases in biological contexts. However, chitosan-functionalized DNA plasmids remain structurally intact and fully functional in physiological conditions [136]. Ahmadi et al. have provided more evidence supporting the significant improvement in the structural integrity of chitosan-modified DNA origamis in low-salt settings and the presence of nucleases [118].

One of the other fascinating molecules with on-demand features for biomedical applications, such as biocompatibility, non-toxicity, thermal stability, and chemical inertness, is silica. Primarily, Nguyen et al. revealed the non-disruptive influence of silicification on 3D DNA nanostructure, which enables structural analysis of DNA nanostructures in both solution and dried state [137]. As the next step, the same research group considered the behavior of the 24-helix bundle and 13-helix ring in distilled water (lack of divalent cations) and DNase I treatment. The thin layer of the silica protected the DNA nanostructures’ intactness in DI water for up to 10 months and noticeably slowed down the nuclease degradation of both nanostructures [103]. The other study recently harnessed the features of silicification of DNA nanostructures for simultaneous diagnosis and treatment of cancer [138]. Recently, another experimental study used the same coating strategy for successful drug delivery and gene silencing in cancer cells. This study introduced disulfide bonds to the silica coat to make the structure sensitive to acidic pH and high glutathione in cancer cell cytoplasm for controllable drug and siRNA release [138].

5.2. Covalent crosslinking of DNA strands comprising nanostructures

Crosslinking agents react with DNA molecules at specific sites and covalently connect nucleotide residues in the same strand or the complementary strands. DNA crosslinkers form interstrand crosslinks, intrastrand crosslinks, DNA-protein crosslinks, or DNA adducts. Psoralens, plant-derived anticancer medicines, prevent the formation of replication forks by crosslinking the double-stranded DNA and arresting cancer cells’ growth (Fig. 6a) [139]. Excited 8-methoxypsoralen, well-known in the treatment of vitiligo and psoriasis, by high wavelength ultraviolet light (UVA; > 400nm) able to deeply penetrate and form covalent adducts with thymidine in both strands of DNA double helices in origami nanostructures. The 8-methoxypsoralen-modified DNA origami represents high thermal stability appropriate for the fabrication of nanoscale electrical and photonic devices [140]. The interaction between 3’-alkyne and 5’-azide functional groups at the DNA strand termini form interlocked rings. Self-assemblies of the rings expand to the large DNA nanostructures with high structural and thermal stabilities. Cassinelli et al. fabricated a stable 6-helix DNA tile tube containing different sets of interlocked rings. The structure resists magnesium ion depletion, nuclease-mediated degradation, and high temperature up to 95°C (Fig. 6b) [141]. On the other hand, 2,5-bis(2-thienyl) pyrrole covalently binds to the cytosine nucleobase in each strand of the duplex DNA. The oxidation reaction polymerized the cytosine-bound 2,5-bis(2-thienyl) pyrrole, resulting in permanent chemical crosslinking of the double-stranded DNA molecules (Fig. 6c). The irreversible crosslinked double-stranded DNA molecules persist in denaturation in the presence of denaturing materials such as urea. 2,5-bis(2-thienyl) pyrrole-crosslinked double-stranded DNA appears to be an excellent building block for creating supramolecular DNA nanostructures [142].

Fig. 6.

Schematic of different types of DNA crosslinkers. a) Psoralen links thymines of the complementary strands to form DNA adducts. Adapted with permission from ref [147]. Copyright (2018) Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. B) The linkage between azide and alkyne at the termini of the DNA strand forms DNA catenane. Modified and reproduced from ref [141]. Copyright (2015) WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. c) SNS binds to cytosines and covalently connects DNA complementary strands. Reproduced from Ref [146] with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Vinyl-modified nucleobases such as 3-cyanovinylcarbazole and p-carbamoylvinyl phenol nucleoside are the other commonly used interstrand photo-crosslinkers that enable the enzyme-independent ligation of blunt-ended DNA molecules. Recently, DNA nanotechnologists harnessed this feature to increase the stability of the 2D and 3D DNA nanostructures in low cation conditions [143,144]. The mechanism of action of these modified bases comprises the covalent bonding upon irradiation with 365 nm light followed by the base stacking interactions between vinyl-modified nucleobase with thymine or adenine in complementary strands. The covalent bond is reversible and would break down upon exposure with the short wavelength light (~ 312 nm). Firstly, Harimech et al. efficiently ligated DNA-gold nanoparticles following light irradiation (356 nm) of the 3-cyanovinylcarbazole-incorporated DNA arrays [145]. Recently, Gerling and Dietz investigated the influence of the covalent crosslinking between 3-cyanovinylcarbazole bases on the configuration alterations of the DNA origami switch. Unlike bare DNA switch, which rapidly switches to open configuration in low cation conditions, structural configuration transition in the photo-crosslinked stabilized structure is irradiation (312 nm) time-dependent [144]. These findings suggested new possibilities in the fabrication of dynamically controlled nanostructures.

Apart from chemical crosslinkers, DNA molecules can physically connect under UV light. UVB light irradiation causes DNA damage by covalently bonding the adjacent thymidine to form cyclobutene pyrimidine dimers. Inspiring UV point welding, UVB irradiation of the multilayer DNA origami containing deliberate thymines in the crossover positions and all the stands’ termini, leads crosslinking the nearby stands and, as a result, enhanced structural stability. Crosslinked structures with extra covalent bonds display exceptional thermal stability and bioactivity under physiological settings. On the other hand, the slower digestive activity of DNase I on such stable structures enhances the circulation half-life [97]. The key restriction of this technique is the negative effect of high-dose UV on DNA structure [146].

5.3. DNA minor groove binders/ DNA intercalators

As we discussed in section 4.1., rationally designed DNA nanostructures have been widely used as carriers of therapeutic payloads for targeted drug delivery. Among various cargos, doxorubicin, a small chemotherapeutic molecule, is prominent [43,49,50,62,65]. Doxorubicin has a planar structure, the major portion of the molecule that intercalates between bases of the two strands, with an aglycone (amine-sugar) side chain. Doxorubicin intercalates between DNA double helix by forming a covalent bond to a guanine of one strand and a hydrogen bond with the guanine on the complementary strand. The amine-sugar portion is protonated in the physiological condition and presumably interacts with the negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA in a minor groove and pushes apart the adjacent bases by 0.34 nm [148,149]. Recently, Ijäs et al. investigated the doxorubicin release rate from various 2D and 3D DNA origami using DNase I degradation. Apart from the related findings in accordance with the aim of the study, they also demonstrated the protective role of doxorubicin against DNase I degradation [104]. Doxorubicin binding to the DNA minor groove likely restricts the access of DNase I to double-stranded DNA, thereby modulating DNase I activity [104].

Minor groove binders are novel chemotherapeutic compounds that selectively bind to AT-rich DNA regions. In comparison to DNA intercalators (e.g., SYBR green, and ethidium bromide), most of the nucleic acid groove binders are less toxic and mutagenic and thereby better candidates for therapeutic development. [150]. Aryl amidine (e.g., diamidines), polyamides (e.g., distamycin), Benzimidazole (e.g., Hoechst 33258), isoquinolines, and pyrrolobenzodiazepines are the main minor groove binders with anti-tumor potential [151]. One of the first studies that investigated the binding mode and the affinity of minor groove binder drug, methylene blue, to different DNA origami was performed by Kollmann et al. in 2018. They found that the DNA binding efficiency of the drug was significantly influenced by the superstructure of the DNA origami [152]. Malina et al. further demonstrated that the minor groove-binding compounds inhibit the interaction of DNA-binding proteins (RNA polymerase in transcription) by limiting the accessibility of the enzymes to their target sequences [153]. The main question raised to be answered was whether the minor groove binders are able to inhibit the nucleases to protect wireframe DNA origami in biological conditions. By interacting several different minor groove binders with DNA wireframe, Wamhoff et al. recently demonstrated a significantly increased half-life against both DNase I and DNase II. The findings emphasize the various protective effects of different classes of minor groove binders. The authors also showed that the interaction of DNA with different minor grooves has no interference with other functional moieties [105].

5.4. Oligonucleotides chemical modifications

DNA molecules are composed of the different combinations of four distinct bases that encode the entire proteome of an organism. Increasing the contribution of nucleic acids in therapeutic approaches and synthetic biology will be possible by expanding the nucleic acid alphabets and diversifying the nucleic acid sequences. Researchers have spent decades exploring diverse modification strategies to expand the chemistry of nucleic acids (Fig. 7). Xeno nucleic acids, bearing modifications on the sugar, phosphodiester bond, nitrogenous bases, or a combination of some, are also known as synthetic genetic polymers and chemically modified nucleic acids with the same base-pairing capacity. Chemical modifications of nucleotide components are gain-of-function alterations improving nuclease resistance and structural stability over natural nucleic acids. Synthetic oligonucleotides with modified nucleotides are expected to have prolonged lifetime and functionality in living cells [154]. Properties like xeno nucleic acid homoduplex formation [155] and self-assembly into three-dimensional structures [156] have prompted researchers to investigate the impact of replacing native DNA with xeno nucleic acids in the development of DNA nanostructures. Several FDA-approved nucleic acid therapeutics are made up of chemically modified oligonucleotides, including Fomivirsen, Pegaptanib, Mipomersen, and Eteplirsen. In further depth, the following sections go through the three primary types of xeno nucleic acids.

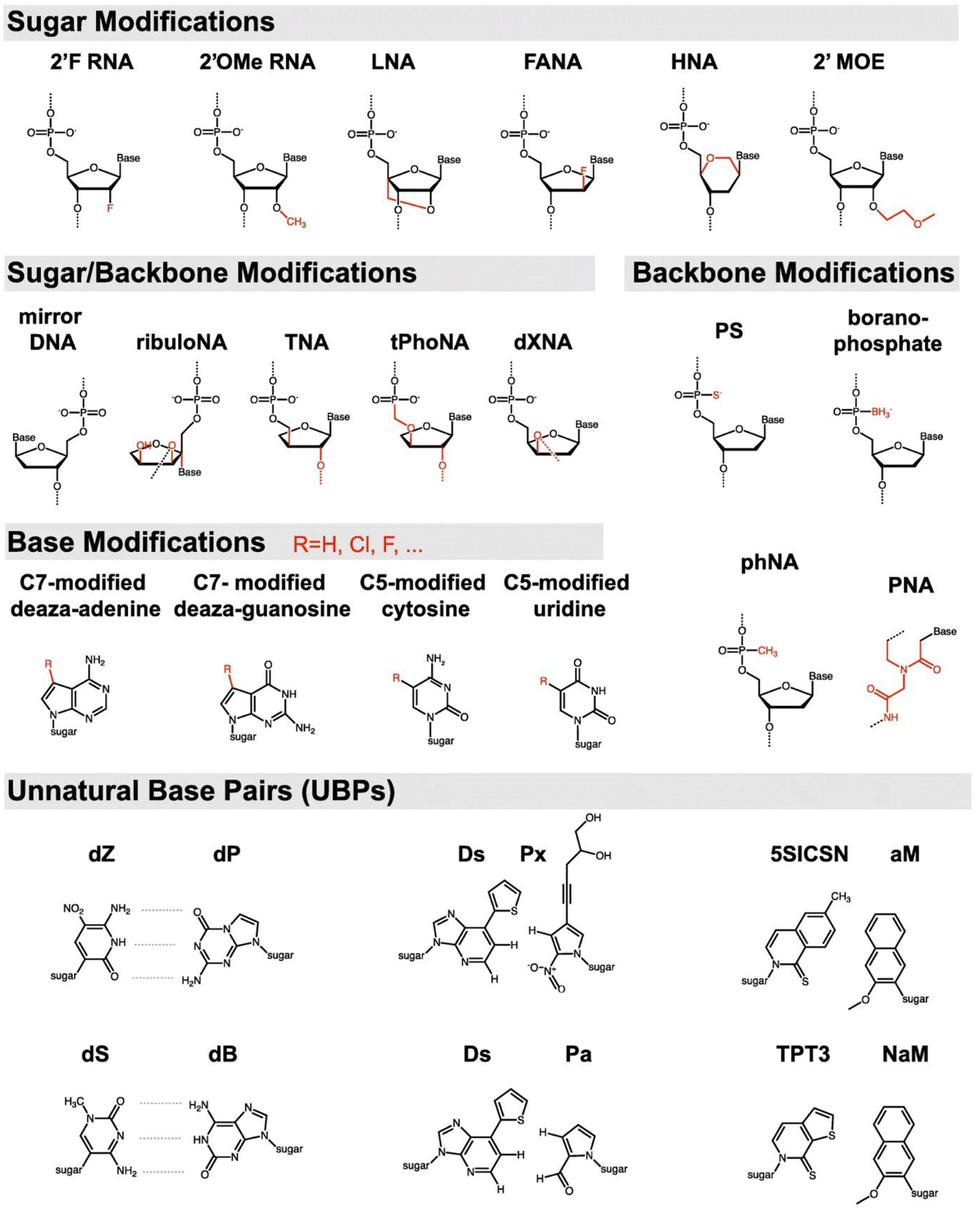

Fig 7.

Expanded nucleic acid chemistry. 2’-F RNA: 2’-Fluoro RNA; 2’OMe RNA: 2’-O-methylation RNA; LNA: Locked nucleic acid; FANA: 2’-Fluoro-arabinonucleic acid; HNA: Hexitol nucleic acid; 2’MOE: 2-Methoxyethyl; PS: Phosphorothioate; PNA: Peptide nucleic acid [160]. Copyright 2020.

A considerable number of oligonucleotides with modified internucleotide linkage have been synthesized. Phosphorothioate linkage is a modified version of the phosphodiester bond in which the sulfur atom sits instead of one nonbridging phosphate oxygen. This simple and inexpensive modification affects the physicochemical properties of nucleic acids by adding chirality to the internucleotide link and producing two different stereoisomers (Sp and Rp). Oligonucleotides with Rp (right-handed) configuration have stronger duplex stability, while the oligonucleotides with Sp (left-handed) configuration have higher nuclease resistance. To address the biostability of the siRNA, a common nucleic acid therapeutic, Jahns et al. synthesized siRNA with phosphorothioate linkages at both 3 and 5 ends and established the siRNAs’ nuclease protection in vivo [157,158]. Other benefits of the phosphorothioate linkage for nucleic acid therapies or DNA nanostructures include a higher affinity of phosphorothioate-linked nucleic acids for serum albumin, which enhances their circulation lifespan [159]. N3’ phosphoramidate linkage (replacing the OH group on the 3’C of the ribose with 3’amine functionality), Boranophosphate internucleotide linkage (nonbridging phosphate oxygen is replaced by trihydridoboron, also known as borane), phosphonoacetate linkage (nonbridging phosphate oxygen is replaced by acetic acid), morpholino phosphoramidates, and peptide nucleic acids are other common types of the modified internucleotide linkages. All these chemical modifications improve the nuclease resistance by introducing chirality to the oligonucleotides [160,161].

Expanding the chemistry of the nucleic acids through sugar modifications provides broad alternatives for natural nucleosides. 2’-O-methyl nucleoside analogs with methyl group replaced for hydrogen on carbon 2’ of the ribose is the most widely used chemical modification of the nucleosides. Oligonucleotides containing 2’-O-methyl nucleosides have a stronger affinity for complementary RNA counterparts, higher nuclease resistance, and a reduced immunostimulatory effect [161]. 2’-deoxy-2’-fluoro-β-D-arabino nucleic acid or 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids is the most applicable xeno nucleic acid in which the ribose or deoxyribose contains an arabinose ring, and the 2’-OH group is replaced by a fluorine atom. 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids can be chemically synthesized through standard chemical DNA synthesis and can hybridize with other single-stranded DNA or RNA through canonical Watson-Crick base pairing. Importantly, fluorine has nine electrons in its structure, and its negatively charged nature protects it against nuclease and acid destruction. Wang et al. experimentally evaluated the thermal stability and nuclease protection effect of the 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids in a double crossover nanotile. They discovered that increasing the number of 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids-containing strands increases the nanotile’s thermal stability and nuclease resistance.

Furthermore, they demonstrated the capability of a 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids-containing nanotile as a carrier of small compounds in mammalian cells [162]. Afterward, many complex 3D nanostructures developed through self-assembly of the sugar-modified nucleic acids for various biomedical applications. Taylor et al. constructed a DNA tetrahedron composed entirely of one or a combination of the 2’-Fluro-2’-deoxy-ribofuranose nucleic acid, 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids, hexitol nucleic acids, and cyclohexene nucleic acids, as well as an octahedron made entirely from 2’-fluoroarabino nucleic acids. The unmodified DNA tetrahedron dissociated completely after 1–2 days of incubation in the serum-containing cell culture media (rich in nucleases), whereas the hexitol nucleic acid-made tetrahedron remained visible after 8 days [163].

Locked nucleic acid is the other common variant of a nucleoside with a methylene bridge connecting the carbon 2’-OH to the carbon 4’ and locking the sugar in the north configuration. Locked nucleic acid is the most widely used chemical variant of the nucleoside in the generation of antisense therapeutic oligonucleotides. Computational simulations and experimental analyses show the impressive impact of locked nucleic acids on thermal stability, nuclease protection, and binding affinity for specific targets [164,165]. Importantly, the improved stability of the locked nucleic acid substituted oligonucleotides is sequence-dependent and more efficiently works when substituted with the nucleotide at the third position in the oligonucleotide. Furthermore, the insertion of one locked nucleic acid reduces ribose flexibility which is unfavorable for the nuclease to attach and degrade DNA. However, the substitution of tandem locked nucleic acids structurally transform the natural B-form to A-form DNA. This change happens by increasing the base-stacking, improving the hydrogen bonding of base pairs, widening the minor groove, and decreasing the DNA twist. The compact A-form DNA prevents the easy accessibility of the nucleases to their target sites on the DNA [166,167].

On the other hand, unlocked nucleic acid (2’,3’-seco-RNA) refers to a nucleoside lacking the covalent bond between the carbon 2’−3’ of ribose or deoxyribose. It is an acyclic RNA mimic with higher flexibility. This modified nucleoside has been used in the synthesis of antisense oligonucleotides, aptamers, and other therapeutic nucleic acids [168]. Incorporation of the unlocked nucleic acid into the siRNA 3’-overhang slightly increases the serum stability and nuclease resistance [169]. 2’-O-2-methoxyethyl and 2’-O-methylcarbamoyl ethyl are two other modifications in which O-methoxyethyl and O-methylcarbamoyl ethyl moieties sit on carbon 2’ of the sugar. These simple changes would improve the nuclease resistance and target affinity as the two beneficial characteristics for nucleic acid therapeutics. One of the FDA-approved nucleic acid therapeutics, mipomersen, contains 2’-O-2-methoxyethyl-modified antisense oligonucleotides. The significantly high affinity of this antisense oligonucleotide for its targets reduces the applied concentration of the drug for therapeutic purposes [170]. Apart from the above-mentioned examples that are created due to the alterations on carbon 2’ of the (deoxy)ribose, there are other modifications such as cyclohexene nucleic acid, altritol nucleic acid, oxepane nucleic acid, ad hexitol nucleic acid with changes in the furanose ring and the result is the improved serum stability and nuclease protection [161].

Recently, many unnatural nucleobases were synthesized by modifying the 4-position and 5-position in pyrimidines and the 6-position and 7-position in purines. These alterations would not affect the canonical base pairing and geometry of the nucleotides. Naturally occurring modified bases such as 2,6-diamino-purine, a modified version of adenine, are the best example of a pair with high duplex stability for uracil and thymine. 5-Bromo-Uran and 5-iodo-Ura are the modified versions of the uracil base with high duplex stability [161,171]. The main unnatural base pairs include i) hydrophobic base pairs such as d5SICS-dNaM, ii) metal-mediated base pairs e.g., N-Ag-N [172], and iii) unnatural base pairs with similar hydrogen bonding as natural bases such as AnN-SyN, isocytidine or 5-methyl-isocytidine-isoguanosine, A-2-thiothymidine [173], 2-amino-8-(1′-β-D-2-deoxyribofuranosyl)-imidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazin-4(8H)one, also called P, and 6-amino-5-nitro-3-(1′-β-D-2′-deoxyribo-furanosyl)-2(1H)-pyridone, called Z nucleobases [174]. The latter contains nucleotides that, although obeying the same Watson-Crick base pairing principles, have different nitro functionality. Sefa et al. revealed that incorporating P and/or Z into the sequence of aptamers substantially increases their affinities for their targets [174].

Synthetic biology aims to create novel therapeutic or diagnostic proteins by engineering semi-synthetic organisms. One way to accomplish this would be to introduce unnatural base pairs to the DNA duplex to translate into unnatural amino acids and proteins with altered structural and chemical properties [175]. Furthermore, the site-specific inclusion of unnatural base pairs enables the post-amplification labeling of DNA that can be utilized as a probe in hybridization techniques [176] and the fabrication of DNA nanostructures [173]. Fabrication of 6-arm DNA junction and 6-helix DNA nanotube using unnatural, more stable 5-methyl-isocytidine/isoguanosine and A/2-thiothymidine base pairs rather than natural C/G and A/T base pairs resulted in a notable improvement in thermal stability, structural integrity, as well as nuclease resistance up to 24 hours after treatment of the structures with T7 exonuclease [177]. As compared to the isocytidine, the methylated isocytidine, utilized by Benner et al. as the first unnatural base pair to diagnose different viral RNA sequences, was chemically more stable [178].

It is a big achievement that the oligonucleotides containing modified nucleotides show high target affinity and nuclease resistance. However, the potential risk of toxicity of modified oligonucleotides is another important aspect of biomedical applications. Locked nucleic acid or bridged-containing allele-specific oligonucleotides showed less hepatotoxicity in comparison to 2’-O-2-methoxyethyl-modified oligonucleotides. The introduction of 2′-O-2-N-Methylcarbamoylethyl in the synthesis of allele-specific oligonucleotides would result in very low hepatotoxicity compared to 2’-O-2-methoxyethyl while maintaining the same on-target effects and target affinity [170] Furthermore, some of the chemical modifications, especially those on the sugar, confer a high affinity for the target to nucleic acids. The higher affinity for the target not only improves duplex stability but also assists the hybridizations that occur in a short homology region even with 1–2 mismatches. It is noteworthy that improved target affinity may result in several non-specific hybridizations of siRNAs or allele-specific oligonucleotides and have detrimental consequences on many cellular pathways or cellular death [179,180].

5.5. Nucleic acid backbone modifications

In biological systems, DNA is a right-handed molecule composed of a D-stereoisomer of deoxyribose. Synthetic left-handed DNA with unique L-form nucleotides is the best orthogonal base-pairing system with the equivalent thermodynamic stability of natural DNA. The opposite chirality of the deoxyribose in left-handed DNA prevents the function of intracellular nucleases, non-specific interaction with cellular macromolecules, and hybridization with intracellular nucleic acids. By taking these virtues together, left-handed DNA exhibits superior resistance to enzymatic degradation with no off-target nucleic acid hybridization. Hauser et al. performed a comprehensive study to compare left-handed DNA with natural D-DNA from several aspects. In contrast to D-DNA oligonucleotides, left-handed DNA oligonucleotides (single-stranded, double-stranded, and chimeric) remain intact following treatment with E. Coli exonuclease I and T7-exonuclease. The same results have been acquired by treating the left-handed DNA oligonucleotide with S1-nuclease and DNase I [106].

Left-handed DNA, identical to its natural D-DNA counterpart, is a biocompatible, nonimmunogenic, and noncytotoxic molecule [181]. Several groups employed left-handed DNA-based biosensors and drug carriers and demonstrated their intactness in physiological conditions. For instance, Kim et al. conducted an exhaustive study on left-handed tetrahedrons as a carrier for in vivo drug delivery instead of the conventional D-tetrahedron. Notably, left-handed tetrahedrons exhibited enhanced resistance to enzymatic attack, resulting in enhanced serum and intracellular stability [182]. Recently, Zhong et al. employed a strand-displacement circuit made by left-handed DNA and a fluorescent reporting system to demonstrate the improved performance and enhanced stability of left-handed DNA in living cells [181].

5.6. DNA end chemical modifications

By adding hydrophobic phosphoramidite monomers or hydrophilic hexaethylene glycol components to the synthetic nucleic acids, Conway et al. proposed a straightforward end modification technique for the functionalization of oligonucleotide chains. The prismatic cage nanostructure fabricated using these modified oligonucleotides showed less susceptibility to nuclease degradation and greater serum stability [183]. Bujold et al. applied the same methodology to fabricate a sensitive DNA cube for prostate cancer-specific biomarkers. In 10% fetal bovine serum media, DNA nanostructures with blunt-end DNA molecules or single-stranded overhang demonstrated stronger nuclease resistance compared to single-stranded DNA counterparts. The presence of functional hydrophobic chains at the exterior face of the cube not only improves cellular uptake but also increases nuclease protection [184]. The hydrophobic compound hexanediol can attach to the 3’ end of an oligonucleotide and prevent DNA polymerase from adding further nucleotides. Assembly of the triangular prism using these modified oligonucleotides noticeably increases the lifetime in nuclease-rich medial [183].

5.7. DNA design and assembly conditions

Paranemic crossover DNA is composed of two double-stranded DNA held together by forming crossover along the entire length of the molecules [185]. The most stable complexes of the paranemic crossover motifs (paranemic crossover 6:5, 7:5, and 8:5) have sequential major-groove spacings of six, seven, and eight base pairs alternating with minor-groove spacings of five base pairs [185]. The biocompatibility of these DNA patterns has been established through in vitro studies utilizing mouse and human cell lines. The stability analysis also corroborates the hypothesis that the nuclease enzymes, such as DNase I, human serum, and urine nucleases, are strikingly prevented from binding to the target sequence and/or from engaging in catalytic activity by the crossovers between DNA helices. This protective effect is crossover-frequency dependent, given that fewer crossovers make the DNA more susceptible to enzyme breakdown [111]. The paranemic crossover DNA motifs have been used as the oligonucleotides in two-dimensional crystals [186], one-dimensional DNA arrays [187], DNA octahedrons [167], and paranemic crossover DNA triangles [188]. The same trend has been observed in more complex DNA nanostructures. Xin et al. compared the stability of the two identical 6-helix bundles with different crossover spacings (21-basepair and 42-basepair) in various concentrations of Mg2+ and in response to nuclease treatment. The twice number of crossovers in the 21-basepair 6-helix bundle decreases the accessibility of the nuclease to cutting sites and consequently, improves the nuclease resistance. They also showed the reduced tolerance of such a compact structure in low-Mg2+ conditions. These findings allow designing the best-fitted DNA nanostructures for specific applications [189].