Abstract

Background/Aim:

Probiotics are live microbial supplements that improve the microbial balance in the host animal when administered in adequate amounts. They play an important role in relieving symptoms of many diseases associated with gastrointestinal tract, for example, in necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), antibiotic-associated diarrhea, relapsing Clostridium difficile colitis, Helicobacter pylori infections, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In this narrative review, the authors aim to evaluate the role of different probiotic formulations in treating gastrointestinal diseases in pediatric population aged 18 years or younger and highlight the main considerations for selecting probiotic formulations for use in this population.

Methodology:

The authors searched PubMed and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to 24th July 2022, without any restrictions. Using an iterative process, the authors subsequently added papers through hand-searching citations contained within retrieved articles and relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Results:

The effectiveness of single-organism and composite probiotics in treating gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients aged 18 or under were analyzed and compared in this study. A total of 39 studies were reviewed and categorized based on positive and negative outcomes, and compared with a placebo, resulting in 25 studies for single-organism and 14 studies for composite probiotics. Gastrointestinal disorders studied included NEC, acute gastroenteritis (AGE), Acute Diarrhea, Ulcerative Colitis (UC), and others. The results show that probiotics are effective in treating various gastrointestinal disorders in children under 18, with single-organism probiotics demonstrating significant positive outcomes in most studies, and composite probiotics showing positive outcomes in all studies analyzed, with a low incidence of negative outcomes for both types.

Conclusion:

This study concludes that single-organism and composite probiotics are effective complementary therapies for treating gastrointestinal disorders in the pediatric population. Hence, healthcare professionals should consider using probiotics in standard treatment regimens, and educating guardians can enhance the benefits of probiotic therapy. Further research is recommended to identify the optimal strains and dosages for specific conditions and demographics. The integration of probiotics in clinical practice and ongoing research can contribute to reducing the incidence and severity of gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients.

Keywords: adolescent, children, gut, microbiome signature, microbiota, synbiotic

Introduction

Highlights

Probiotics are dietary supplements and foods consisting of yeast and bacteria that are commonly used, especially the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. The diseases related to the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) are often caused by an imbalance in the microbiota found in GIT.

Probiotics are believed to play a crucial role in relieving GIT-related disease symptoms and beneficially regulating the microbiota composition. The study supports the role of different probiotic formulations in treating GI diseases among individuals aged 18 years or younger.

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to 24th July 2022, without any restrictions. The search included iterative processes and hand-searching citations contained within retrieved articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

The study includes a descriptive and comparative analysis between single-organism and composite probiotics. Results demonstrate that probiotics are effective in treating various GI disorders, including NEC, FAP, AGE, Acute Diarrhea, Ulcerative Colitis, and many others, and have been compiled into 39 studies categorized by title and outcomes.

The positive outcomes highlight the drug’s effectiveness in improving health, while the negative outcome explains any adverse effects that the drug may have shown. The study emphasizes the importance of gaining further insights into various gut microbes and microbiomes with specific demographic to reduce GI disorders and strengthen the gut.

Functional digestive problems have become more prevalent in recent years and can be associated with various conditions such as gastrointestinal cancers, intestinal obstruction, ulcers, and reflux diseases. Functional gastrointestinal diseases (FGIDs) are the most common type of gastrointestinal disorders, especially in infants, children, and adolescents. As of 2021, around 40% of the world’s population suffers from some form of gastrointestinal disease1. The occurrence rates of FGIDs in pediatric populations have been documented to range from 27 to 40.5% among infants and toddlers aged 0 to 3 years, and from 9.9 to 27.5% among children and adolescents aged 4–18 years2.

Dysbiosis has been linked to various metabolic and chronic medical conditions including gastrointestinal disorders. However, the patterns of dysbiosis have been inconsistently observed across different countries and life stages3. As the human gut microbiome changes significantly over a lifetime, age-specific differences may provide insight into microbiome-mediated effects on health4. The systematic review by Abdukhakimova et al.5 found no clear microbiota signature associated with celiac disease in children’s fecal and/or duodenal samples due to heterogeneity in study design, but suggests that certain fecal microbiota elements, particularly Bifidobacterium spp., such as Bifidobacterium longum, may be useful as diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers and for probiotic therapy and require further investigation. Similarly, study by Poddighe and Kushugulova6, suggested that although a clear microbiome signature for celiac disease has not been identified in humans, several studies suggest that the gut microbiota can impact disease onset and progression through various mechanisms7. Clinical studies on the salivary microbiome in celiac disease are less common but may provide better correlation with the duodenal bacterial environment. Further studies on the salivary microbiome in different populations are necessary to explore its usefulness in understanding celiac disease pathogenesis with potential clinical implications.

Probiotics play an important role in relieving symptoms of many other diseases associated with gastrointestinal tract for example in, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), antibiotic-associated diarrhea, relapsing Clostridium difficile colitis, Helicobacter pylori infections, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). When it pertains to extremely preterm infants between the ages of 2 weeks and 2 months, NEC is the most prevalent major gastrointestinal condition and the leading cause of mortality. The condition mostly affects babies born before 32 weeks of pregnancy, and its frequency is inversely correlated with gestational age8. It is linked to the use of antibiotics, acid suppression, enteral diluted hydrochloric acid, and enteral antibiotics, all of which change the microbiome of the infant’s gut. These findings lend credence to the idea that dysbiosis, or aberrant gut flora, is a primary cause of NEC8. The hallmarks of NEC include acute inflammation, penetration of gas into the portal venous system and bowel wall, ischemic necrosis of the intestinal mucosa, and invasion by enteric gas-forming organisms. These symptoms have been linked to a higher risk of neurodevelopmental (ND) impairment (NDI)9. As far as antibiotic associated diarrhea is concerned, of individuals who obtain antibiotics, up to 35% suffer from diarrhea10. This is attributed to the gut flora’s colonization resistance11. It is frequently mild, but it can occasionally be severe and even fatal, particularly when Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is present10. In addition to frequent watery bowel movements, urgency, and dyspepsia, is linked to changes in intestinal microbiota, mucosal integrity, and vitamin/mineral metabolism. If severe, it can cause toxic megacolon, pseudomembranous colitis, electrolyte imbalances, diminution in volume, and, very rarely, death11. Dysbiosis is also linked to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Disproportionate immune responses against commensal intestinal bacteria have been observed in IBD patients, and these responses may be essential in driving intestinal inflammation12,13. Others, however, speculate that the main cause of inflammation in IBD is an imbalanced gut flora14. Commensal enteric microbes can lead to the following complications in IBD patients; superinfection with intestinal pathogens can trigger flare-ups of the illness; and opportunistic infections become more significant when immunosuppressive medication is used widely. In addition to hepatocellular abscesses, sepsis, and endocarditis, secondary bacterial invasion of mucosal ulcers also frequently results in common septic local complications such as abscesses and fistulae14.

According to the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic and prebiotics; probiotics are live microbial feed supplements that beneficially affect the host animal by improving microbial balance when administered in adequate amounts, while prebiotics are nondigestible dietary compounds that stimulate the growth and activity of specific bacterial populations15,16. To ensure safety and effectiveness, a set of established criteria has been developed for selecting probiotics, as summarized in Table 1 17. Following this, there has been a recent increase in global consumption of nonprescription probiotics for improving overall health, as they have been found to regulate the composition of the microbiota by promoting beneficial bacteria and inhibiting harmful bacteria. However, conflicting clinical findings exist regarding the effectiveness of many probiotic strains and preparations.

Table 1.

Criteria for use as a probiotic17.

| • The organism being utilized must be recognized, that is, its genus, species, and strain must be known |

| • The organism must be deemed viable to consume: *not infectious or harboring genes for antibiotic resistance *not converting to bile acids or degrading to the intestinal mucosa |

| • It needs to endure intestinal transit: tolerance of bile and acid |

| • It has to stick to the mucosa and colonize the gut (at least for a short period) |

| • It must have known and documented impacts on health: *synthesize antimicrobials and combat harmful germs *a minimum of one phase 2 research demonstrating a benefit |

| • During storage and processing, it must remain stable |

Therefore, to address the variability in probiotics research in terms of disparity of studied strains this systematic review aims to assess the efficacy of different probiotic formulations, at the strain level, in treating gastrointestinal diseases in the pediatric population. It provides a comprehensive review of current evidence on the use of probiotics as a complementary therapy for treating gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients, including the effectiveness of single-organism and composite probiotic formulations, ongoing clinical trials, and recommendations for healthcare professionals and guardians. The ultimate goal of this review is to assess the positive and negative outcomes of utilizing probiotic formulation and improve the management of gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients and promote further research in this field.

Methodology

Data sources AND search strategy

We searched PubMed and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to 24th July 2022, without any restrictions. In PubMed, two search strategies were combined, that is, S1 and S2 (Table 2) searches included Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] and limits to title and abstract [Title/Abstract]. S2 was added to exclude studies limited to animals or involving both animal and human participants. Using an iterative process, we subsequently added papers through hand-searching citations contained within retrieved articles and relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table 2.

Detailed search strategy.

| S1: ((infant*[Title/Abstract] OR baby[Title/Abstract] OR babies[Title/Abstract] OR newborn*[Title/Abstract] OR neonat*[Title/Abstract] OR neo nat*[Title/Abstract] OR child*[Title/Abstract] OR toddler*[Title/Abstract] OR adolescen*[Title/Abstract] OR teen*[Title/Abstract] OR teenager*[Title/Abstract] OR youth[Title/Abstract] OR juvenile*[Title/Abstract] OR “Infant”[Mesh] OR “Child”[Mesh] OR “Adolescent”[Mesh])) AND (Probiotics[Title/Abstract] OR “Probiotics”[Mesh]) AND (“Gastrointestinal Diseases”[Mesh])) NOT S2: ((“Animals”[Mesh]) NOT (“Animals”[Mesh] AND “Humans”[Mesh])) |

Inclusion criteria: The studies needed to provide complete data related to the study topic, be randomized controlled trials, focus on evaluating the efficacy of various probiotic formulations in patients with gastrointestinal-related diseases, and be published in peer-reviewed journals in English. We specifically sought studies involving pediatric populations aged 18 years or younger diagnosed with a range of gastrointestinal diseases. Additionally, we included studies that investigated both single-organism and composite probiotic formulations, regardless of dosage or form. In determining the relevance of study outcomes, we considered only those reported in studies where the P-value was less than or equal to 0.05, indicating statistical significance. Furthermore, to facilitate analysis, we classified study outcomes as either positive, indicating health enhancement, or negative, suggesting potential harmful effects of the intervention. These classifications are detailed comprehensively in Table 3 for clarity and reference.

Table 3.

List of randomized controlled trials analyzing different types of that is, single-organism and composite probiotic formulations.

| Single-organism probiotic vs. placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study and patient characteristics | ||||||

| Study | Study location | Sample size (n= number of individuals) | Study population (Gastrointestinal disease) | Intervention (Probiotic Formulation) | Positive outcome | Negative outcome |

| Benor S. et al.11 | Israel | 58 | NEC | L reuteri DSM 17938 (1 108 Colony-Forming Units/D) | Intervention might decrease the incidence of NEC in breastfed infants | N/A |

| Romano C. et al.11 | Sicily | 60 | Functional Abdominal Pain (FAP) | Lactobacillus reuteri | The intervention reduced perceived abdominal pain intensity | N/A |

| Serce O. et al.18 | Turkey | 208 | NEC | Saccharomyces boulardii | N/A | The intervention did not decrease the incidence of NEC or sepsis |

| Demirel G. et al.19 | Turkey | 271 | NEC | S. boulardii | Feeding intolerance and clinical sepsis were found to be significantly lower in the probiotic group | The intervention was not effective at reducing the incidence of death or NEC in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants |

| Pieścik-Lech M. et al.20 | Poland | 88 | AGE | LGG and smectite versus LGG alone | LGG plus smectite and LGG alone are equally effective for treating young children with AGE. The combined use of the two interventions is not justified | N/A |

| Francavilla R. et al.21 | Italy | 74 | Acute Diarrhea | Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 derived from L. reuteri ATCC 55730 | The intervention was found beneficial in reducing the frequency, duration and recrudescence rate of the disease | N/A |

| Oliva S. et al.22 | Italy | 40 | Mild to Moderate Ulcerative Colitis (UC) | L. reuteri | The intervention was effective in improving mucosal inflammation and changing mucosal expression levels of some cytokines involved in the mechanisms of inflammatory bowel disease | N/A |

| Maldonado J. et al.23 | Spain | 215 | Incidence Of Infections | Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 (L. Fermentum) | The intervention was found useful for the prevention of community-acquired gastrointestinal and upper respiratory infections | N/A |

| Sari FN. et al.24 | Turkey | 221 | NEC | Lactobacillus sporogenes | Feeding intolerance was significantly lower in the probiotics group than in the control group | The intervention showed no significant difference in the incidence of death or NEC between the groups |

| Dinleyici EC. et al.25 | Turkey | 68 | Blastocystis Hominis Infection | Saccharomyces boulardii | Metronidazole or S. boulardii has potential beneficial effects on B. hominis infection | N/A |

| Indrio F. et al.26 | Italy | 42 | Regurgitation | Lactobacillus reuteri | Intervention reduces gastric distension and accelerates gastric emptying. In addition, this probiotic strain seems to diminish the frequency of regurgitation | N/A |

| Francavilla R. et al.12 | Italy | 141 | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) or (FAP) | LGG | The intervention seemed to significantly reduce the frequency and severity of abdominal pain in children with IBS; this effect is sustained and may be secondary to the improvement of the gut barrier | N/A |

| Martens U. et al.13 | Iran | 52 | IBS | LGG | The key IBS symptoms (abdominal pain, stool frequency), as well as the other symptoms (bloating, mucous and blood in stool, need for straining at stools, urge to defecate), improved significantly during treatment. Global assessment of therapy by parents and doctors was altogether positive | No adverse effects were shown |

| Coccorullo P. et al.14 | Naples | 44 | Functional Chronic Constipation | Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938) | The intervention caused a higher frequency of bowel movements | The intervention showed no improvement in stool consistency and episodes of inconsolable crying episodes |

| Hojsak I. et al.15 | Croatia | 742 | Nosocomial Gastrointestinal Tract Infections | LGG | The intervention caused the risk for gastrointestinal infections, vomiting episodes and diarrheal episodes, episodes of gastrointestinal infections, episodes of respiratory tract infections that lasted 3 days to significantly decrease |

N/A |

| Hojsak I. et al.16 | Daycare centers are located in 4 separate locations in the Zagreb area | 281 | Gastrointestinal Tract Infections | LGG | Intervention reduced the risk of gastrointestinal infections, vomiting episodes, and diarrheal episodes. However, intervention caused no reduction in the number of days with gastrointestinal symptoms |

N/A |

| Baldassarre ME. et al.17 | Bari hospital | 30 | Hematochezia and Fecal Calprotectin | LGG | LGG resulted in significant improvement of hematochezia and fecal calprotectin compared with the extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (EHCF) alone | N/A |

| Sentongo TA. et al.27 | Chicago, IL | 21 | Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS) | LGG | N/A | Findings do not support empiric LGG therapy to enhance IP in children with SBS |

| Szajewska H. et al.28 | Poland | 29 | Rectal Bleeding | LGG | N/A | The intervention was ineffective in treating rectal bleeding in breastfed infants. No adverse effects were reported |

| Bauserman M. et al.29 | Children’s medical center pediatric gastroenterology | 50 | IBS | LGG | The intervention showed improvement in abdominal distention | Lactobacillus GG was not superior to placebo in the treatment of abdominal pain in children with IBS |

| Sýkora J. et al.30 | Czech republic | 86 | Helicobacter Pylori | Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) DN-114 001 | Eradication success was higher due to intervention | Side effects were infrequent |

| Dani C. et al.31 | Italy | 585 | Urinary Tract Infection, Bacterial Sepsis and NEC | LGG | It was found that infants who received Lactobacillus GG were less affected by NEC after 1 week of treatment | The intervention was not effective in reducing the incidence of UTIs, NEC and sepsis in preterm infants |

| Saran S. et al.32 | India | 100 | Diarrhea | Lactobacillus acidophilus | There were significantly fewer cases of diarrhea and fever due to the intervention | N/A |

| Rosenfeldt V. et al.33 | Denmark | 43 | Acute Diarrhea | L. reuteri DSM 17938 | The intervention was effective in reducing the duration of diarrhea | N/A |

| Guandalini S. et al.34 | Eleven centers in 10 countries | 287 | Acute Diarrhea | LGG | The intervention was deemed safe and results were obtained in a shorter duration of diarrhea. There was less chance of a protracted course, and patients were discharged earlier from the hospital | No adverse effects (rash, drug-related fever or nausea, etc.) related to the synbiotic use were noted |

| Composite Probiotic vs. Placebo | ||||||

| Muhammed Majeed. et al.35 | Three clinical sites i) Mysore Medical College and K R Hospital, Mysore, India ii) Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Bangalore, India and iii) Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangalore, India |

36 | Diarrhea Predominant IBS | Bifidobacterium breve, Lactobacillus casei and Galactooligosaccharides | The intervention caused a significant change/decrease in clinical symptoms like bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Stool frequency disease severity also decreased and the quality of life increased in the patient due to the intervention |

No serious adverse effects were shown |

| Evette Van Niekerk. et al.36 | Neonatal high care unit of Tygerberg Children’s Hospital (TBCH), Cape Town, South Africa |

184 | NEC | Probiotic Mixture (Bifidobacteria infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacteria bifidus; Solgar, Israel) | reduced the incidence of NEC reduction in the severity of disease was found in the HIV-exposed study group |

The intervention failed to show that probiotics lowered the incidence of NEC in HIV-exposed premature infants |

| Ali İşlek. et al.37 | Pediatric Emergency and Pediatric Gastroenterology Departments of the Akdeniz University Hospital |

156 | Acute Infectious Diarrhea | Infloran | The duration of diarrhea was significantly shorter in the synbiotic group than in the placebo The duration of diarrhea was shorter for patients who started the synbiotic therapy within the first 24 h than for those who started their treatment later |

No adverse effects were shown |

| Xiaolin Wang. et al.38 | Three medical centers—the Department of Pediatric Surgery, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology; The First Hospital of Harbin Medical University; and Anhui Provincial Hospital | 60 | Hirschsprung’s Disease-Associated Enterocolitis (HAEC) |

Lactobacillus plantarum 299 and Bifidobacterium infantis cure 21 | The incidence of HAEC (three out of 30, 10.0%) in the probiotic-treated group was significantly reduced the severity of HAEC in the probiotic-treated group was significantly reduced Probiotics-balanced T lymphocyte, IFN-γ, and IL-6 were significantly decreased inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was remarkably increased |

N/A |

| Marta Olivares. et al.39 | Hospital Universitari Sant Joan (Reus, Tarragona) and Hospital Universitario Sant Joan de Deu (Barcelona) | 33 | Colic Disease | a capsule containing either B. longum CECT 7347 (109 colony forming units) | The intervention caused a significant increase in the height percentile, decreased levels of peripheral CD3+ T lymphocytes and slightly reduced TNF-a concentration, The B. longum CECT 7347 group also had reduced numbers of the Bacteroides fragilis group and lower sIgA content in stools compared to the placebo group | No adverse events were reported during the intervention |

| Fernández-Carrocera LA. et al.40 | Mexico | 150 | NEC | Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacterium lactis containing 1 × 10(9) Total Organisms) | The intervention caused a reduction of NEC frequency, significantly lowered risk for the combined risk of NEC or death | No adverse effects were shown during hospitalization |

| Braga TD. et al.41 | Northeast brazil | 231 | NEC | VSL#3 | The intervention reduced the occurrence of NEC (Bell’s stage ≥ 2). It was considered that an improvement in intestinal motility might have contributed to this result | N/A |

| Cazzola M. et al.42 | France | 135 | Prevention of common winter diseases in children | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum, Enterococcus faecium, | Intervention decreased the risk of occurrence of common infectious diseases in children and limited the risk of school day loss | N/A |

| Guandalini S. et al.43 | Italy (4) and in India (1) Chicago, IL (1) | 59 | IBS | Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei | The intervention caused improvement in IBS symptoms | No adverse event was recorded |

| Lin HC. et al.44 | Taiwan | 217 | NEC | Mixture of Bifidobacterium longum (BB536) and Lactobacillus johnsonii (La1 ) | The incidence of death or NEC (stage 2) was significantly lower | No adverse effect, such as sepsis, flatulence, or diarrhea, was noted |

| Bin-Nun A. et al.45 | Shaare zedek medical center | 145 | NEC | Probiotic Mixture (Bifidobacteria infantis, Bifidobacteria bifidum, Bifidobacteria longum and Lactobacillus acidophilus | reduced both the incidence and severity of NEC | No adverse effects were shown |

| Kliegman RM. et al.46 | Houston, texas | 155 | NEC | Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus acidophilus | The incidence of death or NEC (stage 2) was significantly lower | N/A |

| Vandenplas Y. et al.47 | Belgium | 111 | Acute Diarrhea | Synbiotic food supplement Probiotical (Streptoccoccus thermophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium infantis, fructo-oligosaccharides) | The median duration of diarrhea was significantly 1 day shorter in the synbiotic than in the placebo group, associated with decreased prescription of additional medications | N/A |

| Miele E. et al.48 | Italy | 29 | UC | VSL#3 | Endoscopic and histological scores were significantly lower in the VSL#3 group Remission was achieved in 13 patients |

No adverse effects were shown |

Exclusion criteria: All the unpublished trials, animal-based studies, study designs, that is, pilot and observational studies, reviews, editorials, commentaries, case reports, case series, and studies reporting incomplete data were excluded.

Results

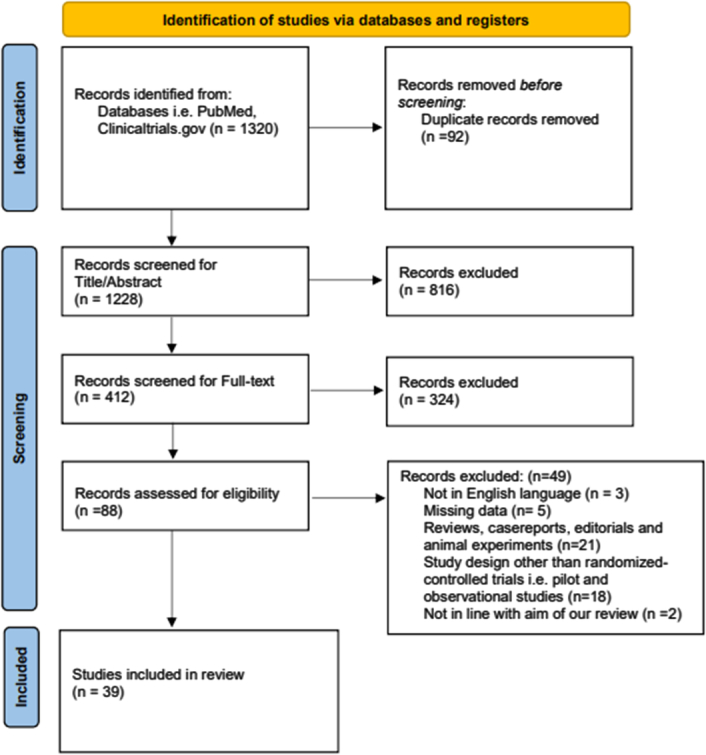

Data selection

Following the primary search and after removing duplicates, we screened 1228 articles for relevance based on title and abstract and full-text. We also manually searched for additional articles by looking through reference lists of the included full-text. In the end, a total of 39 studies were included in our review, details of the screening process are displayed in the flowchart below (Fig. 1). A list of selected examples of probiotic formulations is provided in Table 4. The studies are summarized in Table 3 based on their characteristics and findings.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart summarising the screening process.

Table 4.

Selected examples of probiotic formulations.

| Single-organism probiotic | Composite probiotic |

|---|---|

| Saccharomyces boulardii | Ecologic®Relief: Bifidobacteria (B.) bifidum, B. infantis, B. longum, Lactobacilli (L.) casei, L. plantarum and L. rhamnosus |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | A mixture of Bifidobacterium breve, Lactobacillus casei and Galactooligosaccharides Probiotic Mixture (Bifidobacteria infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacteria bifidus) |

| Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347 | Infloran: Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium infantis |

| Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 | Mixture of Lactobacillus plantarum 299 and Bifidobacterium infantis cure 21 |

| Lactobacillus sporogenes | Mixture of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium infantis |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) | Mixture of oral bifidobacterium, lactobacillus acidophilus, and enterococcus Triple Viable Capsules |

| Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938) | Bifidobacterium infantis, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacterium lactis, |

| Lactobacillus casei (DN-114 001) | Mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacteria lactis |

| Lactobacillus GG (Dicoflor) | VSL#3 is composed of four strains of lactobacillus, three strains of bifidobacterium, and one strain of Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophiles |

| Mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum, Enterococcus faecium | |

| Mixture of Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei | |

| Mixture of Bifidobacterium longum (BB536) and Lactobacillus johnsonii (La1 ) | |

| Probiotic mixture of Bifidobacteria infantis, Bifidobacteria bifidum, Bifidobacteria longum and Lactobacillus acidophilus | |

| Mixture of Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus acidophilus | |

| Mixture of L. acidophilus and B. infantis |

Single probiotic

According to Table 3, of the 25 articles assessed, 22 reported at least one statistically significant positive outcome between single-organism probiotics vs placebo18–21,23–37,45,46. The remaining three reported no statistically significant positive outcome attributed to single-organism probiotics38–40. A study reported that single-organism probiotics decreased the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in breastfed infants17,37. Another study reported that intervention reduced the intensity of abdominal pain18,26,27,30. Feeding intolerance and clinical sepsis were found to be significantly lower in the probiotic group according to another study23,28. Pieścik-Lech et al.20 reported that the combined use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) plus smectite or LGG alone are effective in treating young children with acute gastroenteritis (AGE). Single-organism probiotics were found to be beneficial in decreasing the frequency and duration of the gastrointestinal diseases like that is, AGE, acute diarrhea, and NEC20,32–34. Additionally, it also improved mucosal inflammation and changed mucosal expression levels of some cytokines involved in the mechanism of inflammatory bowel disease21. These probiotics were found to result in more frequent bowel movements, decreased stomach bloating, and accelerated gastric emptying25,28. Hojsak et al. reported a decreased risk of respiratory tract infections and gastrointestinal infections with probiotics in children in daycare centers and pediatric facilities35,36.

In contrast, of the of the 25 articles assessed, 16 reported no statistically significant negative outcomes between single-organism probiotics vs placebo18,20,21,23,25–27,29,30,32–35,37,41,45. The remaining nine reported at least one statistically significant negative outcome attributed to single-organism probiotics19,24,28,31,35,38–40,46.

Few studies reported that single-organism probiotics did not decrease the incidence of NEC19,24,31,38. Additionally, no improvement in stool consistency was seen, but accompanied episodes of inconsolable crying were reported28. A study showed that intervention was ineffective in treating rectal bleeding in breastfed infants40. Lactobacillus rhamnosus therapy in children with short bowel syndrome did not improve intestinal permeability and was associated with conversion to positive hydrogen breath test results46.

Composite probiotics

Of the 14 articles using composite probiotics assessed, all reported at least one statistically significant positive outcome between composite probiotics vs placebo22,42–44,47–55. One study reported that composite probiotics decreased clinical symptoms like bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain42,44. It also decreased disease severity, consequently improving the quality of life in the patient42,43. Studies showed a lower incidence of NEC frequency with intervention in the HIV-exposed study group, preterm infants and low-birth neonates43,44,47,49,53,54,56. Taking composite probiotics within 24 h significantly decreased the duration of diarrhea compared to those who took it later50. Xiaolin et al.51 reported that T lymphocytes, IFN-γ, and IL-6 decreased, whereas IL-10 increased in patients treated with probiotics along with a decreased incidence of HAEC (3/30, 10%). Another study reported a decreased risk of common infectious diseases in children with probiotics, leading to a lower risk of school day loss55. Similarly, one study reported that the median duration of diarrhea was 1 day shorter in synbiotic food supplement Probiotical (Streptoccoccus thermophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium infantis, fructo-oligosaccharides) than the placebo group and hence, was associated with a decreased prescription of additional medications48. Another study reported that remission was achieved in active UC patients and endoscopic and histological scores were significantly lower in the VSL #3 group (Table 4) compared to the placebo group22.

In contrast, of from the 14 articles assessed, 13 reported no statistically significant negative outcomes between composite probiotics vs placebo22,42,44,47,48,50–55,57. The remaining reported one statistically significant negative outcome attributed to composite probiotics, the study reported that probiotics failed to decrease the incidence of NEC in HIV-exposed premature infants43.

Discussion: a way forward

In this study, the effectiveness of single-organism and composite probiotics in treating gastrointestinal disorders in the pediatric population aged 18 or under were analyzed and compared. A total of 39 studies were reviewed and categorized based on their outcomes, which included positive and negative effects of the probiotics. The studies were compared with a placebo, both individually and as a group, resulting in 25 studies for single-organism probiotics and 14 studies for composite probiotics. Gastrointestinal disorders studied included NEC, AGE, Acute Diarrhea, UC, and others. The findings of the study emphasize the effectiveness of probiotics in treating various gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric aged 18 or younger, with single-organism probiotics showing significant positive outcomes in most studies and composite probiotics showing positive outcomes in all studies analyzed, with low incidence of negative outcomes for both types of probiotics.

The possible mechanism of activity of some probiotic characteristics may be present in a uniform manner across different species or even genera58. As such, efficacy may vary across different strains. For instance, both Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. can generate the enzyme β-galactosidase, which can help address lactase insufficiency59. In contrast, other traits may be specific to certain species60 or even strains61, or may require interactions between different probiotic strains62. Some probiotic preparations, particularly those containing specific strains such as S. boulardii and LGG, have been shown in several meta-analyses and systematic reviews to help alleviate acute diarrhea in children and reduce its duration of diarrhea63–65. However, one recent updated meta-analysis based on large-scale randomized placebo-controlled trials66,67 involving over nine-tenth children in their total sample size with AGE concluded that large trials with low risk of bias suggest that probiotics are unlikely to have a significant impact on the incidence of diarrhea lasting 48 h or longer, and there is uncertainty regarding their effectiveness in reducing the duration of diarrhea63. Earlier guidelines that supported the use of probiotics in the management of AGE, based on lower-quality evidence, are now contradicting with these new findings.

There is evidence to suggest that probiotics may be effective in averting neonatal late-onset sepsis and NEC, a digestive illness that frequently impacts premature infants68. Research conducted on animals and human cell cultures proposes that specific types of probiotics, including LGG, could safeguard against NEC by strengthening the body’s defense mechanisms against harmful microorganisms, encouraging the growth of the immune system and cells lining the intestine, and reducing inflammation69. However, other trials involving very preterm infants in England using Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001 showed no significant effect on NEC or sepsis prevention70. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have produced conflicting outcomes on the effectiveness of enteral probiotics in preterm infants. A 2014 Cochrane review involving more than 5000 infants concluded that the administration of enteral probiotics containing either Lactobacillus alone or in combination with Bifidobacterium can decrease the occurrence of NEC and mortality in preterm infants, but not nosocomial sepsis71. Similarly, different systematic review and meta-analysis showed that probiotics are useful in reducing the occurrence of late-onset sepsis in preterm infants when given as mixtures and exclusively to those fed with human milk72. However, other meta-analyses did not find any significant effect of probiotics in preventing NEC or sepsis in infants with extremely low birth weights73,74. Depending on the disease and the particular probiotic being used, there may also be variations among the ideal dosage and period of probiotic treatment. Any probiotic strain has to reach its ideal mass or dosage for it to thrive and colonize the gut. Present literature shows that probiotics must be living and at high enough dosages (usually 106–107 colony-forming units (cfu)/g of product) in order to be effective75. However, Stool colonization rates indicate large studies often employ doses of 1×108 or 1×10976, and greater doses (1×1010) do not appear to enhance colonization rates77.

Prebiotics, on the other hand, which comprise different combinations of acidity, fructo-oligosaccharides, and galacto-oligosaccharides from nonhuman milk, have been researched in preterm children for a long time. These prebiotic mixes promote gastric peristalsis, minimize eating intolerance, raise stool sIgA, modify the fecal microbiota, and lower stool pH levels78. In contrast to probiotics which have some evidence of reducing incidence of NEC and sepsis in preterm infants, a meta-analysis of seven prebiotics placebo-controlled randomized clinical studies reveals that they play no role in the reduction in NEC, sepsis, or death in preterm infants79.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first one to examine the efficacy of probiotics on multiple gastrointestinal diseases among pediatric population younger or 18 years of age, highlighting all positive and negative outcomes for each probiotic to enable a more detailed comparison of the specific strains of each probiotic when used individually or in a composite. This approach provides valuable insights into the response of gastrointestinal disorders to probiotics, with a focus on strain-specific efficacy. By excluding animal studies, our synthesis solely focused on the effects of the intervention on human participants, which enhance the validity and reliability of our article. However, despite its well-designed methodology, further research is required to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Clinical implications

The findings of this study suggest that both single-organism and composite probiotic formulations are effective complementary therapies for treating various gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients aged 18 years and under. As such, healthcare professionals should consider incorporating probiotics into standard treatment regimens. Gastrointestinal disorders among children are a significant cause of mortality, and probiotics have proven to be a safe and effective intervention. Fortunately, The National Institute of Health (NIH) has progressed with multiple ongoing clinical trials that aim to cater to various gastrointestinal disorders. A list of ongoing clinical trials listed in Table 5 provide valuable resources for clinicians and researchers interested in studying the effectiveness of strain-specific probiotic formulations for various gastrointestinal disorders in different age groups. However, there are many challenges to there are some challenges in clinical implications. The American Academy of Pediatrics 2021 guidelines highlight several warnings against recommending probiotics for preterm infants, particularly in infants with extremely low birth weight, including the absence of positive outcomes in a large RCT from the UK, the shortages of pharmaceutical-grade probiotics in the USA, the diversity of probiotic strains, demographic baselines of participants, and setting, and insufficient safety data80. Probiotic usage in healthy individuals may be safe, but in early newborns, it has been linked to an increased likelihood of infection and/or morbidity81 and underweight newborns82. This is most likely attributed to the transmigration of the administered strain or strains over the intestinal wall is most likely involved in the pathophysiology of probiotic sepsis83. It may further be challenging to detect because of difficulty forming colonies of obligate anaerobes using conventional culture techniques84.

Table 5.

List of ongoing trials analyzing single-organism and composite probiotic formulations against gastrointestinal diseases.

| Single-organism probiotic vs. placebo | ||

|---|---|---|

| Trial ID | Age | Intervention |

| NCT0416076769 | up to 14 years | Drug: Probiotic Vivomixx Behavioral: Gluten-free diet Other: Placebo |

| NCT0356222170 | 4 months to 4 months | Other: Gluten-free diet Dietary Supplement: Probiotics Dietary Supplement: Placebo |

| NCT0410321671 | 12 months to 36 months | Nitazoxanide with Lactobacillus Reuteri DSM 17938 Nitazoxanide |

| Composite Probiotics vs. Placebo | ||

| NCT0492247672 | 8 years to 18 years | Dietary Supplement: Alflorex |

| NCT0402130373 | 4 to 12 months old | Dietary Supplement: Experimental cereal Dietary Supplement: Conventional cereal |

| NCT0454177174 | 28 weeks to 34 weeks | Drug: Lactobacillus Reuteri DSM 17938 Drug: Placebo |

| NCT0401466075 | 10 years to 18 years | Probiotic L.plantarum Heal 9 and L.paracasei 8700:2 |

Probiotics can also lead to harmful metabolic activities. Increased D-lactate, which may result in D-lactate acidosis, is one example. Not only do the majority of preterm babies already likely to be acidotic, but blood gases cannot regularly quantify D-lactate, which makes it extremely challenging to catch84 Probiotics also possess the potential to sometimes cause allergic responses, especially when Saccharomyces boulardii is employed in those who have a history of yeast allergies. In the early stages of treatment, abdominal pain and bloating are possible side effects. Antibiotic resistance genes, like those of enterococci, can also be transferred on by some probiotics. Some probiotic strains like Bacillus cereus may also release emetic and enterotoxin85. As such, a personalized plan is essential, and medical professionals should evaluate the unique condition and treatment response of every child. Selecting reliable brands and products is crucial since there may be variations in the quality and purity of probiotics. Since probiotics are typically sold as nutritional supplements rather than pharmaceuticals, the market for them is unregulated, allowing producers to alter the composition of their products or the method of manufacturing without appropriately addressing these concerns86. For instance, it was reported that contamination of a composite prebiotic was linked to a deadly case of gastrointestinal mucomycosis87. To relay trial results to clinical practise, it is crucial to ensure accurate product identity at the strain level both during research and throughout real clinical application88.

Future insights and recommendations

It is recommended that guardians of pediatric age groups must be educated on the management of symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders. Oral rehydration for diarrhea, laxatives for constipation, and anti-emetics for vomiting are baseline treatments, this information can be provided to guardians through their doctor visits, health-care helpline and even educational health campaigns. The guardians must also ensure to keenly observe their children’s dietary and hygiene habits as that immensely affects gut health, routine checkup on bowel habits is recommended.

While the present study is a valuable addition to current knowledge on probiotics and their efficacy in treating gastrointestinal disorders, further research into identifying the optimal type, dose, and duration of probiotic therapy for specific conditions and strains that are most effective is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their effectiveness. Specifically, future studies should focus on directly comparing single-organism and composite probiotic formulations, as well as examining the specific strains used as interventions. This would provide more precise guidelines for selecting effective probiotic formulations. Preclinical studies on mice have shown clinical benefits in alleviating symptoms following gastrointestinal diseases69,89. However, the effects observed in animal models do not necessarily translate to humans90, and further research is necessary to identify the molecular players involved including the gut-brain axis. Furthermore, despite the promising results, caution is necessary when using probiotics in the treatment of NEC. The treatment’s effectiveness depends on factors such as the specific strains used, the dosage, the mode of administration, and the inclusion of prebiotics. The patient’s characteristics, such as their baseline risk concerning birth weight, environmental exposure to microorganisms, and diet, should also be taken into account58. The long-term effects of using probiotics on the natural gut microbiome and their impact on gut health need more research. Furthermore, large-scale studies analyzing microbiota signatures related to various disorders, like celiac disease, can help clinicians choose the most effective probiotic formulations for functional gastrointestinal disorders in children.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size and demographic scope, which may not be representative of a broader population or geographical area. Unfortunately, for the majority of the aforementioned clinical indications, there are also studies of similarly high methodological quality featuring opposing and negative results which cause disparity in overall inferences. In addition, the techniques employed in these experiments vary greatly, and encompass estimations from cell cultures, in vitro studies animal models, and human research. The diversity of strains investigated in probiotics research is another factor contributing to its unpredictability. Even now, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera, Lactococcus species, Streptococcus thermophilus, E. coli, and Saccharomyces boulardii are the predominant microorganisms employed in the probiotics sector. Certain health-related mechanisms of action—like the synthesis of bile salt hydrolases—are shared by several probiotic genera and species, while other characteristics may be unique to a particular strain or they might need to interact with one another to have an outcome. In addition, human responses to the same intervention may vary due to their great degree of heterogeneity in terms of nutrition, age range, genetic makeup, and gut microbiome composition, which sets them apart from animal models. It is also important to consider that individual responses to probiotics for gastrointestinal disorders can vary based on metabolites, genetics, and environmental factors. Therefore, the results obtained in this study may not be generalizable to all populations Lastly, a large number of probiotic research are financed by probiotic industry commercial entities or by professional advocacy groups closely affiliated and supported by the same industry. Additionally, biased results may occur due to the lack of randomization in the sample selection process. There is a need for independent verification of effectiveness claims through nonbiased research. Future human-based trials should also aim to overcome these limitations by conducting larger and more diverse studies, and implementing rigorous randomization protocols to reduce potential sources of bias scientific and medical organizations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of both single-organism and composite probiotic formulations as effective complementary therapies for gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric patients. However, due to inconsistency and limitation of our paper we cannot conclude which type of formulation, single or composite, is superior over the other. Hence, this paper warrants large-scale trials to validate the efficacy of either type. Overall, healthcare professionals should consider incorporating probiotics into standard treatment regimens and educate guardians on symptom management and gut health. Addressing colonization resistance is crucial for optimizing probiotic therapy, and the development of predictive algorithms based on host and microbiome features can aid in personalized treatment strategies. Further research into various gut microbes and microbiomes with specific demographics is recommended to enhance our understanding and application of probiotic interventions.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Sources of funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contribution

A.S.: conceptualized the original draft; A.S., S.I.A., and R.H.: visualized; A.S., R.H., S.I.A., L.I.V., K.Q., N.F., A.A., V.P., S.O., and M.A.H.: contributed to writing the original draft; A.S., S.O., M.A.H.: reviewed the final draft.

Conflicts of interest disclosures

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: not applicable.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: not applicable.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): not applicable.

Guarantor

All authors accept full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Data availability statement

Available upon reasonable request from corresponding author.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Published online 4 April 2024

Contributor Information

Amna Siddiqui, Email: siddiquie.amna@gmail.com.

Ramsha Haider, Email: ramshahaider521@gmail.com.

Syeda Ilsa Aaqil, Email: syedailsaaaqil@gmail.com.

Laiba Imran Vohra, Email: laibaimranvohra@gmail.com.

Khulud Qamar, Email: khu.qamr@gmail.com.

Areesha Jawed, Email: areeshajawed00@gmail.com.

Nabeela Fatima, Email: nab.hameed25@gmail.com.

Alishba Adnan, Email: alishbaadnan13@gmail.com.

Vidhi Parikh, Email: vidhiparikh529@gmail.com.

Sidhant Ochani, Email: Sidhantochani1@gmail.com.

Md. Al Hasibuzzaman, Email: al.hasibuzzaman.hasib@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Avramidou M, Angst F, Angst J, et al. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal symptoms in young and middle-aged Swiss adults: prevalences and comorbidities in a longitudinal population cohort over 28 years. BMC Gastroenterol 2018;18:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, et al. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the Rome IV criteria. J Pediatr 2018;195:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2369–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duvallet C, Gibbons SM, Gurry T, et al. Meta-analysis of gut microbiome studies identifies disease-specific and shared responses. Nat Commun 2017;8:1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdukhakimova D, Dossybayeva K, Poddighe D. Fecal and duodenal microbiota in pediatric celiac disease. Front Pediatr 2021;9:652208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poddighe D, Kushugulova A. Salivary microbiome in pediatric and adult celiac disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021;11:625162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdu EF, Galipeau HJ, Jabri B. Novel players in coeliac disease pathogenesis: role of the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel RM, Underwood MA. Probiotics and necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg 2018;27:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaidya R, Yi JX, O’Shea TM, et al. Long-term outcome of necrotizing enterocolitis and spontaneous intestinal perforation. Pediatrics 2022;150:e2022056445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett JG. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2002;346:334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Q, Goldenberg JZ, Humphrey C, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD004827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank DN, Robertson CE, Hamm CM, et al. Disease phenotype and genotype are associated with shifts in intestinal-associated microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartor RB. Key questions to guide a better understanding of host–commensal microbiota interactions in intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol 2011;4:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2008;134:577–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. Expert consensus document: the international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borchers AT, Selmi C, Meyers FJ, et al. Probiotics and immunity. J Gastroenterol 2009;44:26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francavilla R, Miniello V, Magistà AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of lactobacillus GG in children with functional abdominal pain. Pediatrics 2010;126:e1445–e1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demirel G, Erdeve O, Celik IH, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: A randomized, controlled study. Acta Paediatrica, Int J Paediatr 2013;102:e560–e565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pieścik-Lech M, Urbańska M, Szajewska H. Lactobacillus GG (LGG) and smectite versus LGG alone for acute gastroenteritis: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 vs. placebo in children with acute diarrhoea - a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;36:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miele E, Pascarella F, Giannetti E, et al. Effect of a probiotic preparation (VSL#3) on induction and maintenance of remission in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldonado J, Cañabate F, Sempere L, et al. Human milk probiotic lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 reduces the incidence of gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sari FN, Dizdar EA, Oguz S, et al. Oral probiotics: lactobacillus sporogenes for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth weight infants: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011;65:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinleyici EC, Eren M, Dogan N, et al. Clinical efficacy of Saccharomyces boulardii or metronidazole in symptomatic children with Blastocystis hominis infection. Parasitol Res 2011;108:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Indrio F, Riezzo G, Raimondi F, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri accelerates gastric emptying and improves regurgitation in infants. Eur J Clin Invest 2011;41:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martens U, Enck P, Zieseniss E. Probiotic treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. German Med Sci 2010;8:07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coccorullo P, Strisciuglio C, Martinelli M, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM 17938) in infants with functional chronic constipation: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Pediatr 2010;157:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benor S, Marom R, Tov A, et al. Probiotic supplementation in mothers of very low birth weight infants. Am J Perinatol 2014;31:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano C, Ferrau’ V, Cavataio F, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri in children with functional abdominal pain (FAP). J Paediatr Child Health 2014;50:E68–E71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dani C, Biadaioli R, Bertini G, et al. Probiotics feeding in prevention of urinary tract infection, bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: A prospective double-blind study. Biol Neonate 2002;82:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saran S, Gopalan S, Krishna TP. Use of fermented foods to combat stunting and failure to thrive. Nutrition 2002;18:393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenfeldt V, Michaelsen KF, Jakobsen M, et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus strains on acute diarrhea in a cohort of nonhospitalized children attending day-care centers. Pediatric Infect Dis J 2002;21:417–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guandalini S, Pensabene L, Zikri MA, et al. Lactobacillus GG administered in oral rehydration solution to children with acute diarrhea: a multicenter European trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hojsak I, Abdović S, Szajewska H, et al. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of nosocomial gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics 2010;125:e1171–e1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hojsak I, Snovak N, Abdović S, et al. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections in children who attend day care centers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr 2010;29:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sýkora J, Valecková K, Amlerová J, et al. ,Effects of a specially designed fermented milk product containing probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 and the eradication of H. pylori in children: a prospective randomized double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serce O, Benzer D, Gursoy T, et al. Efficacy of saccharomyces boulardii on necrotizing enterocolitis or sepsis in very low birth weight infants: a randomised controlled trial. Early Hum Dev 2013;89:1033–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sentongo TA, Cohran V, Korff S, et al. Intestinal permeability and effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus therapy in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;46:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szajewska H, Gawrońska A, Woś H, et al. Lack of effect of Lactobacillus GG in breast-fed infants with rectal bleeding: a pilot double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliva S, Di Nardo G, Ferrari F, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 rectal enema in children with active distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35:327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majeed M, Nagabhushanam K, Natarajan S, et al. Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 supplementation in the management of diarrhea predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a double blind randomized placebo controlled pilot clinical study. Nutr J 2016;15:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Niekerk E, Nel DG, Blaauw R, et al. Probiotics reduce necrotizing enterocolitis severity in HIV-exposed premature infants. J Trop Pediatr 2015;61:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guandalini S, Magazzù G, Chiaro A, et al. VSL#3 improves symptoms in children with irritable bowel Syndrome: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;51:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baldassarre ME, Laforgia N, Fanelli M, et al. Lactobacillus GG improves recovery in infants with blood in the stools and presumptive allergic colitis compared with extensively hydrolyzed formula alone. J Pediatr 2010;156:397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bausserman M, Michail S. The use of Lactobacillus GG in irritable bowel syndrome in children: A double-blind randomized control trial. J Pediatr 2005;147:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin HC, Hsu CH, Chen HL, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight preterm infants: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2008;122:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vandenplas Y, De Hert SG. Randomised clinical trial: the synbiotic food supplement Probiotical vs. placebo for acute gastroenteritis in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kliegman RM. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 2005;146:710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Islek A, Sayar E, Yilmaz A, et al. The role of Bifidobacterium lactis B94 plus inulin in the treatment of acute infectious diarrhea in children. Turk J Gastroenterol 2015;25:628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Li Z, Xu Z, et al. Probiotics prevent Hirschsprung’s disease-associated enterocolitis: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olivares M, Castillejo G, Varea V, et al. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled intervention trial to evaluate the effects of Bifidobacterium longum CECT 7347 in children with newly diagnosed coeliac disease. Br J Nutr 2014;112:30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernández-Carrocera LA, Solis-Herrera A, Cabanillas-Ayón M, et al. Double-blind, randomised clinical assay to evaluate the efficacy of probiotics in preterm newborns weighing less than 1500 g in the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013;98:F5–F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braga TD, da Silva GAP, de Lira PIC, et al. Efficacy of Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei oral supplementation on necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cazzola M, Pham-Thi N, Kerihuel JC, et al. Efficacy of a synbiotic supplementation in the prevention of common winter diseases in children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010;4:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stricker T, Braegger CP. Oral probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis. Oral probiotics reduce the incidence and severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;42:446–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bin-Nun A, Bromiker R, Wilschanski M, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr 2005;147:192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E, et al. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat Med 2019;25:716–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonder MJ, Kurilshikov A, Tigchelaar EF, et al. The effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome. Nat Genet 2016;48:1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fernandez EM, Valenti V, Rockel C, et al. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut 2011;60:1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin YP, Thibodeaux CH, Peña JA, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppress proinflammatory cytokines via C-Jun. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1068–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lavasani S, Dzhambazov B, Nouri M, et al. A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS One 2010;5:e9009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, et al. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;2010:CD003048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feizizadeh S, Salehi-Abargouei A, Akbari V. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for acute diarrhea. Pediatrics 2014;134:e176–e191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szajewska H, Kołodziej M, Gieruszczak‐Białek D, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for treating acute gastroenteritis in children – a 2019 update. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:1376–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freedman SB, Williamson-Urquhart S, Farion KJ, et al. Multicenter trial of a combination probiotic for children with gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2015–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schnadower D, Tarr PI, Casper TC, et al. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG versus placebo for acute gastroenteritis in children. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2002–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rao SC, Athalye-Jape GK, Deshpande GC. Probiotic supplementation and late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20153684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan F, Liu L, Cao H, et al. Neonatal colonization of mice with LGG promotes intestinal development and decreases susceptibility to colitis in adulthood. Mucosal Immunol 2017;10:117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Costeloe K, Hardy P, Juszczak E, et al. Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001 in very preterm infants: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2016;387:649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alfaleh K, Anabrees J. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Evidence-Based Child Health 2014;9:584–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aceti A, Maggio L, Beghetti I, et al. Probiotics prevent late-onset sepsis in human milk-fed, very low birth weight preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2017;9:904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dermyshi E, Wang Y, Yan C, et al. The “Golden Age” of probiotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and observational studies in preterm infants. Neonatology 2017;112:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang GQ, Hu HJ, Liu CY, et al. Probiotics for preventing late-onset sepsis in preterm neonates. Medicine 2016;95:e2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shah NP, Ali JF, Ravula RR. Populations of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus casei in Commercial Fermented Milk Products. Biosci Microflora 2000;19:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berrington JE, Zalewski S. The future of probiotics in the preterm infant. Early Hum Dev 2019;135:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dutta S, Ray P, Narang A. Comparison of stool colonization in premature infants by three dose regimes of a probiotic combination: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol 2014;32:733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Westerbeek EAM, Slump RA, Lafeber HN, et al. The effect of enteral supplementation of specific neutral and acidic oligosaccharides on the faecal microbiota and intestinal microenvironment in preterm infants. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;32:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Srinivasjois R, Rao S, Patole S. Prebiotic supplementation in preterm neonates: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2013;32:958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Poindexter B, Cummings J, Hand I, et al. Use of probiotics in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2021;147:e2021051485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quin C, Estaki M, Vollman DM, et al. Probiotic supplementation and associated infant gut microbiome and health: a cautionary retrospective clinical comparison. Sci Rep 2018;8:8283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Topcuoglu S, Gursoy T, Ovali F, et al. A new risk factor for neonatal vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonisation: bacterial probiotics. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med 2015;28:1491–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kulkarni T, Majarikar S, Deshmukh M, et al. Probiotic sepsis in preterm neonates—a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr 2022;181:2249–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Costa RL, Moreira J, Lorenzo A, et al. Infectious complications following probiotic ingestion: a potentially underestimated problem? A systematic review of reports and case series. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18:329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saeed NK, Al-Beltagi M, Bediwy AS, et al. Gut microbiota in various childhood disorders: implication and indications. World J Gastroenterol 2022;28:1875–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van den Akker CHP, van Goudoever JB, Shamir R, et al. Probiotics and preterm infants: a position paper by the european society for paediatric gastroenterology hepatology and nutrition committee on nutrition and the european society for paediatric gastroenterology hepatology and nutrition working group for probiotics and prebiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020;70:664–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vallabhaneni S, Walker TA, Lockhart SR, et al. Notes from the field: Fatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis in a premature infant associated with a contaminated dietary supplement—Connecticut, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:155–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Toscano M, De Grandi R, Pastorelli L, et al. A consumer’s guide for probiotics: 10 golden rules for a correct use. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buffington SA, Di Prisco GV, Auchtung TA, et al. Microbial reconstitution reverses maternal diet-induced social and synaptic deficits in offspring. Cell 2016;165:1762–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reis DJ, Ilardi SS, Punt SEW. The anxiolytic effect of probiotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical and preclinical literature. PLoS One 2018;13:e0199041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request from corresponding author.