Abstract

Mus dunni endogenous virus (MDEV) infects a wide variety of cell types from many different species. To take advantage of this broad host range, we have constructed packaging cells (PD223) that produce virions bearing the MDEV envelope. PD223 cells are able to package Moloney murine leukemia virus-based vectors at a titer of 4 × 105 infectious units per ml in the absence of contaminating replication-competent retrovirus. Vectors packaged by PD223 cells are able to transduce CHO cells, which are resistant to transduction by many retroviruses, at ≥25-fold higher efficiency than vectors having other pseudotypes. A vector packaged by PD223 was found to be among the most efficient for transducing primary baboon and human CD34+ cells.

Retroviral vectors have become important tools for the study of biology and for the transfer of genes for therapeutic purposes. A crucial step in gene transfer by retroviral vectors is the binding of the virus envelope protein (Env) to a specific cellular receptor. Because cells vary in their expression of retroviral receptors, it is important to have available a variety of packaging cells that express different envelopes that in turn recognize different receptors. Viral interference experiments show that the recently described Mus dunni endogenous virus (MDEV) uses a novel receptor among murine retroviruses (10). Retroviral vectors pseudotyped by wild-type MDEV can infect different cell types from a variety of species, including mouse, rat, hamster, cat, dog, quail, and human (2). We have therefore constructed packaging cells that express the MDEV envelope to take advantage of its novel receptor usage and have evaluated the potential of vectors packaged by PD223 for use in hematopoietic gene therapy.

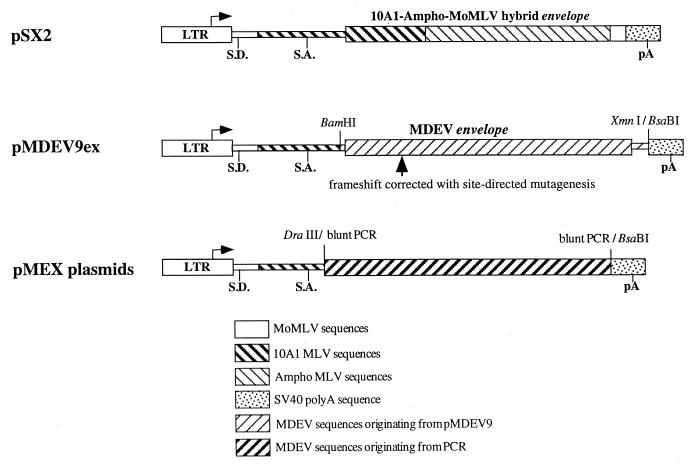

Generation of MDEV Env expression plasmids.

The original molecular clones of MDEV contained a frameshift mutation in the envelope gene that precluded expression of complete Env proteins (15). Intact env genes were obtained by several methods and cloned into the expression plasmid pSX2 (Fig. 1), which was chosen because it was found to express the highest levels of 10A1 murine leukemia virus (MLV) Env among a series of constructions (7). pMDEV9ex contains an MDEV env from the original clone that was corrected by site-directed mutagenesis (15).

FIG. 1.

Envelope expression constructs. The constructs are drawn to scale, and the backbone plasmid sequences are not shown. Each plasmid contains the MoMLV LTR promoter (truncated at the 5′ end to the Sau3AI site upstream of the enhancers), the MoMLV splice donor, the 10A1 MLV splice acceptor, an envelope coding sequence, and the simian virus 40 (SV40) early polyadenylation sequence. The pMDEV9ex plasmid was created by cloning a 2,165-bp BamHI-XmnI fragment containing the corrected MDEV env into the 3,948-bp fragment of pSX2 prepared by digestion with BsaBI and partial digestion with BamHI. The structure of pMEX represents 20 plasmids in which the MDEV env was amplified from various sources and cloned into the 3,835-bp DraIII-BsaBI fragment of pSX2.

The pMEX series of plasmids contain the entire envelope of MDEV (nucleotides 5754 to 7787; accession no. AF053745) amplified using the high-fidelity Pwo polymerase with various templates. Templates included plasmid DNA containing the same envelope sequence as pMDEV9ex (pMEXplasmid clones), DNA from M. dunni tail fibroblasts (dunni cells) that had not been activated to produce MDEV (pMEXdunni clones), and DNA from MDEV-infected cat G355 cells that produce a high titer of MDEV (pMEXG355 clones). Amplification products were inserted in place of the 10A1 MLV env of pSX2, and 20 clones representing a variety of templates were selected for analysis.

Evaluation of MDEV Env expression plasmids.

LGPS/LAPSN cells are NIH 3T3 cells that express Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) Gag and Pol (8) and contain the LAPSN retroviral vector, which expresses a human placental alkaline phosphatase (AP) gene (11). These cells secrete viral particles containing the LAPSN genome, but the particles are not infectious due to the lack of Env proteins. The MDEV Env expression plasmids were evaluated by transfecting them into LGPS/LAPSN cells and measuring the titer of infectious LAPSN vector particles 2 days after transfection. A preliminary experiment used to screen the 20 pMEX clones showed that all 5 clones containing the MDEV env amplified from plasmid DNA were functional, 5 out of 6 clones amplified from G355/LAPSN+MDEV cellular DNA were functional, but only 2 out of 9 clones amplified from dunni cell DNA were functional (data not shown). We have shown that elements related to MDEV exist in the M. dunni genome (2), and some of these nonfunctional pMEX plasmids may carry related but defective envelopes. We have not sequenced any of the nonfunctional plasmids.

The transfection experiments indicate that the various functional MDEV Env expression plasmids express similar levels of the MDEV Env (Table 1 and data not shown for pMEXG355). In each case, however, the LAPSN titers resulting from transfection of the MDEV Env expression plasmids were lower than those achieved by transfection of pSX2. This may reflect the biology of the viruses, for 10A1 MLV typically achieves titers that are 100-fold higher than those of MDEV. Viral interference experiments demonstrated that the LAPSN vector packaged by the MDEV Env in these transfection experiments used the same receptor as that used by wild-type MDEV (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the functionality of the MDEV Env expression plasmidsa

| Plasmid | LAPSN titer (AP+ FFU/ml)b |

|---|---|

| pBSIIKS+ | <5 |

| pSX2 | 1 × 105 |

| pMDEV9ex | 2 × 103 |

| pMEXplasmid | 2 × 103 |

| pMEXdunni | 2 × 103 |

LGPS/LAPSN cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells per 6-cm-diameter dish on day 1. On day 2, 10 μg of each plasmid DNA was transfected in duplicate dishes by calcium phosphate precipitation. The medium was replaced on day 3 and harvested on day 4 and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cells and debris. Virus titration was performed as described previously (11) on D17 cells (ATCC CCL183). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% FBS.

The titers are means of the values obtained from the duplicate transfections.

Creation of the MDEV packaging cells and selection of clones.

To generate the MDEV packaging cells, one of the active pMEXdunni clones was stably introduced into LGPS cells (NIH 3T3 cells that express MoMLV Gag and Pol [9]) by cotransfection with the selectable plasmid pSV2Δ13-hyg (a gift from Paul Berg at Stanford University) at a ratio of 20:1. The plasmid pMEXdunni was chosen because it likely contains the env sequence identical to that of the native M. dunni provirus. After transfection, the cells were selected in 0.4 mg of hygromycin per ml for 7 days, and 38 clones were isolated. The clones were designated “PD,” for packaging cells based on the M. dunni endogenous virus envelope. Two screens confirmed that the PD clone 223 (PD223) packaged the LAPSN vector at the highest titer [>105 AP+ focus-forming units (FFU)/ml]. Upon determining that PD223 packaged LAPSN at the highest titer, we cloned the PD223/LAPSN cells to obtain a high titer producer line which consistently produces the LAPSN vector at a titer of 4 × 105 AP+ FFU/ml measured on D17 canine cells.

The pMEXdunni env nucleotide sequence of the PD223 cells differs from the published MDEV env sequence at only one nucleotide, located at position 6186 at the end of the first variable region of the envelope. The reported MDEV sequence has an A, corresponding to an Arg residue, and that of pMEXdunni has a G, corresponding to a Gly residue. Sequence analysis of additional cloned PCR products amplified from DNA from either dunni cells or G355/LAPSN+MDEV cells demonstrated a G at this position, indicating that pMEXdunni has the same env sequence as the native MDEV provirus.

A vector packaged by PD223 cells uses the same receptor as MDEV.

Viral interference analysis is used to classify retroviruses into groups according to receptor usage and relies on the observation that a cell producing a retroviral Env is resistant to infection by a retrovirus that recognizes the same receptor as the expressed Env. Interference assays were conducted to determine whether a vector packaged by the PD223 cells uses the same receptor as MDEV (Table 2). The LAPSN(PD223) and LAPSN(PA317) vectors contain the same MoMLV Gag and Pol proteins, so any differences observed are Env-specific and therefore at the level of viral entry. The entry of LAPSN(PA317) was not impeded by the presence of MDEV in dunni/N2 cells nor by the expression of retroviral proteins in the PD223 cells (which are based on NIH 3T3 cells), as expected, indicating that the amphotropic MLV envelope expressed by PA317 cells recognizes a different receptor than does MDEV. However, the entry of LAPSN(PD223) was dramatically impeded by the presence of MDEV in dunni/N2 cells (>24,000-fold interference), and the entry of LAPSN(MDEV) was impeded by the presence of retroviral constructs in PD223 cells (400-fold interference), indicating that the Env proteins contained on LAPSN(PD223) virions recognize the same receptor as MDEV.

TABLE 2.

Vectors packaged by PD223 cells use the same receptor as does MDEVa

| LAPSN pseudotypec | LAPSN titer (FFU/ml)b on:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dunni/N2 | dunni/N2+MDEV | NIH 3T3 | PD223 | |

| PA317 | 1 × 106 | 1 × 106 | 2 × 105 | 2 × 105 |

| PD223 | 6 × 104 | <2.5 | 2 × 103 | 20 |

| MDEV | NDd | ND | 2 × 103 | 5 |

Data are from two separate experiments, each of which was repeated with nearly identical results. The first experiment included the dunni and dunni/N2+MDEV cells and the second included NIH 3T3 and PD223 cells as targets for infection. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% FBS except for GL8c16 cells, which were used to produce the LAPSN (MDEV) virus and which were cultured in McCoy’s medium with 15% FBS. Titration was performed as described previously (11) on D17 cells.

The titers are the means of duplicate assays in which each value varied by no more than 17% of the mean, except for the values 20 and 5 which represent only a few foci.

The LAPSN vector with a PA317 (amphotropic) pseudotype was made by using PA317 cells (6) containing the LAPSN vector. The LAPSN vector with a PD223 pseudotype was made by using PD223/LAPSN cells and had a titer of 3 × 105 AP+ FFU/ml on D17 cells. MDEV pseudotype LAPSN vector was harvested from the GL8c16 clone of G355/LAPSN+MDEV cells. This particular virus stock had a lower titer than usual and thus gave a titer on NIH 3T3 cells equivalent to that of LAPSN(PD223) virus, although the GL8c16 virus titer is usually about 10-fold higher.

ND, not determined.

PD223 cells package vectors without contaminating helper virus.

A risk inherent to packaging cells is the generation of contaminating replication-competent retroviruses (RCR), or helper virus. One potential source of RCR in other packaging cells is homologous recombination among the engineered sequences in the packaging cells. This could not generate RCR in the PD223 cells due to lack of sequence similarity or overlap in the appropriate regions of the constructs. A homologous recombination event could join a long terminal repeat (LTR) from an LN-series vector (9) with the gag and pol sequences of pLGPS to generate the 5′ half of an RCR, but a homologous recombination event between pLGPS and pMEXdunni could not complete the set of retroviral genes due to a deletion of pol in pMEXdunni. Additionally, there is no similarity between the 3′ end of the MDEV env in pMEXdunni and an LN-series vector that could supply a 3′ LTR to a recombinant virus. However, incompletely characterized endogenous retroviral sequences could be involved in generation of RCR. Furthermore, rarer recombination events that involve no sequence homology could occur, making it necessary to directly test for RCR.

We used two marker rescue assays to screen for RCR. The assays were performed by adding test medium harvested from PD223/LAPSN cells to G355/LAPSN or dunni/LAPSN cells, passaging the cells for more than 2 weeks to allow for viral spread, and then transferring medium exposed to the cells to naive G355 or dunni cells, respectively. If the test medium contained RCR that could replicate in the cells, that virus should package the LAPSN vector and induce AP+ foci in the final indicator cells. Cells that were the same type as the LAPSN-containing amplification cells were used as the final indicators to ensure that any virus that could grow in the marker rescue assay cells could also infect the indicator cells. The G355-based assay was able to detect RCR in 0.01 μl of MDEV-containing medium, and the dunni cell-based assay was able to detect RCR in 0.1 μl of MDEV-containing medium. Similarly, both assays could efficiently detect amphotropic MLV. Neither assay, however, revealed any contaminating RCR in medium conditioned by PD223/LAPSN cells (<0.5 infectious units/ml).

PD223 cells are useful for transduction of CHO cells.

CHO cells provide an important tool for genetic analysis due to their functionally haploid nature (13) and are widely used in biotechnology for production of glycosylated therapeutic proteins. Unfortunately, CHO cells are relatively resistant to transduction by a variety of retroviral vectors, with a block at the level of viral entry (12). We have previously demonstrated that a vector pseudotyped by wild-type MDEV could efficiently transduce CHO cells, so we compared the LAPSN vector packaged by PD223 cells to LAPSN packaged by seven other packaging cells that express different envelopes for the ability to transduce CHO cells (Table 3). The titers of LAPSN packaged by the various cell lines were generally low when measured with CHO cells, as predicted. However, the titer on permissive cells (D17 or NIH 3T3) was high for each stock, demonstrating that there was functional virus present. The most efficient entry into CHO cells was achieved by LAPSN(PD223), which transduced CHO at least 25-fold more efficiently than vectors packaged by any of the seven other packaging cells.

TABLE 3.

Vectors packaged by PD223 cells efficiently transduce CHO cellsa

| Packaging cells | Reference | Envelope type or description | LAPSN titer (FFU/ml)b on:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO | D17 | NIH 3T3 | |||

| PA317 | 6 | Amphotropic | <20 | 1 × 106 | NDc |

| PG13 | 8 | GALV | 600 | 3 × 106 | ND |

| PT67 | 7 | 10A1 | 800 | 3 × 105 | ND |

| PX | 1 | Xenotropic | <20 | 3 × 105 | ND |

| PM571 | 12 | MCF/polytropic | <20 | ND | 1 × 105 |

| PE501 | 9 | Ecotropic | <20 | ND | 1 × 106 |

| FLYRD | 3 | RD114 | <20 | 4 × 106 | ND |

| PD223 | This report | MDEV | 2 × 104 | 2 × 105 | ND |

Cells were plated at 105 cells per 3.5-cm-diameter well of a 6-well dish on day 1, infected on day 2 in the presence of 4 μg of Polybrene per ml, and stained for AP+ foci on day 4. All packaging cells, D17 cells, and NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% FBS, and CHO-K1 cells (ATCC CCL 61) were grown in α-minimal essential medium with 5% FBS.

Titers are means of results from duplicate assays, which varied from the mean by no more than 18%. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

ND, not determined.

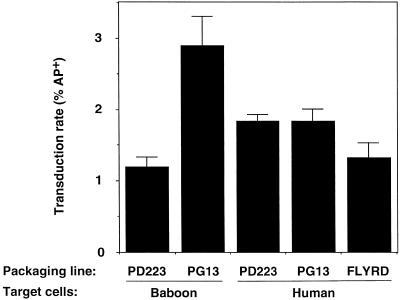

Vectors packaged by PD223 cells transduce primary baboon and human CD34+ cells.

Hematopoietic stem cells are an attractive target for gene therapy. Cells selected for the CD34 surface antigen contain hematopoietic stem cells and have been used here as a model for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell transduction. Primary baboon and human CD34+ cells were transduced with LAPSN pseudotyped by PD223 and PG13 (8) packaging cells. PG13 is a packaging cell line that is preferred for transduction of baboon and human CD34+ cells (5). Additionally, the FLYRD packaging cell line was included in the human cell experiment because it shows promise for transduction of human cells (3); however, it does not infect baboon cells (data not shown). Flow cytometry using an anti-human placental AP antibody revealed two distinct populations of cells, allowing the determination of the percentage of transduced cells. In the baboon cell experiment, the LAPSN packaged by PD223 transduced the CD34+ cells with about twofold lower efficiency than did LAPSN packaged by PG13. In the human cell experiment, the LAPSN packaged by PD223 transduced the cells as efficiently as did LAPSN packaged by PG13 and more efficiently than did LAPSN packaged by FLYRD (Fig. 2). In both experiments, mock-transduced CD34+ cells showed ≤0.05% transduction. The rates of transduction in these experiments were lower than those we usually obtain, but are within the range typically observed for these assays. Because CD34+ cells are a heterogeneous population, it is possible that the vectors with different pseudotypes transduced different subpopulations of cells. The only true assay of a stem cell is the measurement of its ability to reconstitute hematopoiesis in a myeloablated animal, so additional experiments will be required to further assess the utility of PD223 cells for use in hematopoietic gene therapy.

FIG. 2.

The LAPSN vector packaged by PD223 cells transduces baboon and human CD34+ cells relatively efficiently. Fresh normal bone marrow cells were selected for the presence of the CD34+ antigen by using an immunomagnetic column procedure (7). On day 1, the cells were prestimulated with flt-3 ligand, interleukin 6, stem cell factor (100 ng/ml each), and megakaryocyte growth and development factor (50 ng/ml) during culture in RPMI medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). On day 2, cells were plated at 50,000 cells per well in a 24-well Pronectin F culture plate (for the experiment with human cells) (Protein Polymer Technologies) or in the presence of fibronectin fragment CH-296 (for the experiment with baboon cells) (Retronectin; Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Shiga, Japan) (4), in 500 μl of medium and exposed to 500 μl of LAPSN(PD223), LAPSN(PG13), or LAPSN(FLYRD) in the presence of Polybrene (4 μg/ml). Fresh virus was added on day 3, and the percentage of AP-expressing cells was evaluated by flow immunocytometry on day 5. For analysis, the cells were harvested, resuspended in hybridoma 2.4G2-conditioned medium to block FcγII receptors (14), and labeled using anti-human placental alkaline phosphatase (clone 8B6; Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.) which had been conjugated with biotin. After washing, the cells were stained using streptavidin phycoerythrin (Dako) and further washed. Prior to analysis, cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% FBS and propidium iodide (1 μg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) using CellQuest II software. Dead cells and debris were excluded by gating on forward and high angle light scatter and by the absence of propidium iodide staining. Each value represents the average of three separate transductions, with the standard deviations indicated. Human cells were obtained by using a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board, and baboon cells were obtained by using a protocol approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

In summary, we have taken advantage of the broad host range of MDEV by constructing packaging cells based on the MDEV envelope. Vectors packaged by PD223 cells can transduce a wide variety of cell types, including CHO cells, which are resistant to transduction by vectors packaged by many other packaging cells, and human CD34+ cells, which are considered an important target for human gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca Gottschalk for technical assistance, Hans-Peter Kiem and Julia Morris for advice on transduction of hematopoietic cells, and Jean-Luc Battini for providing the cell line PX/LAPSN.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL36444, HL54881, and DK47754. J.E.J.R. was supported by fellowship DRG081 of the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Battini, J.-L. Unpublished data.

- 2.Bonham L, Wolgamot G, Miller A D. Molecular cloning of Mus dunni endogenous virus: an unusual retrovirus in a new murine viral interference group with a wide host range. J Virol. 1997;71:4663–4670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4663-4670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosset F-L, Takeuchi Y, Battini J-L, Weiss R A, Collins M K L. High-titer packaging cells producing recombinant retroviruses resistant to human serum. J Virol. 1995;69:7430–7436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7430-7436.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiem H-P, Andrews R G, Morris J, Peterson L, Heyward S, Allen J M, Rasko J E J, Potter J, Miller A D. Improved gene transfer into baboon marrow repopulating cells using recombinant human fibronectin fragment CH-296 in combination with IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF. Blood. 1998;92:1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiem H-P, Heyward S, Winkler A, Potter J, Allen J M, Miller A D, Andrews R G. Gene transfer into marrow repopulating cells: comparison between amphotropic and gibbon ape leukemia virus pseudotyped retroviral vectors in a competetive repopulation assay in baboons. Blood. 1997;90:4638–4645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller A D, Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller A D, Chen F. Retrovirus packaging cells based on 10A1 murine leukemia virus for production of vectors that use multiple receptors for cell entry. J Virol. 1996;70:5564–5571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5564-5571.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller A D, Garcia J V, von Suhr N, Lynch C M, Wilson C, Eiden M V. Construction and properties of retrovirus packaging cells based on gibbon ape leukemia virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2220-2224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller A D, Rosman G J. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. BioTechniques. 1989;7:980–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller A D, Wolgamot G. Murine retroviruses use at least six different receptors for entry into Mus dunni cells. J Virol. 1997;71:4531–4535. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4531-4535.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller D G, Edwards R H, Miller A D. Cloning of the cellular receptor for amphotropic murine retroviruses reveals homology to that for gibbon ape leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:78–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller D G, Miller A D. Tunicamycin treatment of CHO cells abrogates multiple blocks to retrovirus infection, one of which is due to a secreted inhibitor. J Virol. 1992;66:78–84. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.78-84.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siminovitch L. On the nature of hereditable variation in cultured somatic cells. Cell. 1976;7:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unkeless J C. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. J Exp Med. 1979;150:580. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolgamot G, Bonham L, Miller A D. Sequence analysis of Mus dunni endogenous virus (MDEV) reveals a hybrid VL30/GALV-like structure and a distinct envelope. J Virol. 1998;72:7459–7466. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7459-7466.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]