Abstract

Introduction:

People engaged in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) report struggling with whether and how to disclose, or share information about their OUD history and/or treatment with others. Yet, disclosure can act as a gateway to re-establishing social connection and support during recovery. The current study describes a pilot randomized controlled trial of Disclosing Recovery: A Decision Aid and Toolkit, a patient decision aid designed to facilitate disclosure decisions and build disclosure skills.

Methods:

Participants (n = 50) were recruited from a community-based behavioral health organization in 2021–2022 and randomized to receive the Disclosing Recovery intervention versus an attention-control comparator. They responded to surveys immediately after receiving the intervention as well as one month following the intervention at a follow-up appointment. Primary outcome analyses examined indicators of implementation of the intervention to inform a future efficacy trial. Secondary outcome analyses explored impacts of the intervention on the decision-making process, disclosure rates, and relationships.

Results:

Participants were successfully recruited, randomized, and retained, increasing confidence in the feasibility of future efficacy trials to test the Disclosing Recovery intervention. Moreover, participants in the Disclosing Recovery intervention agreed that the intervention is acceptable, feasible, and appropriate. They additionally reported a higher quality of their decision-making process and decisions than participants in the comparator condition. At their follow-up appointment, participants with illicit opioid use who received the Disclosing Recovery intervention were less likely to disclose than those who received the comparator condition. Moreover, significant interactions between opioid use and the intervention condition indicated that participants without illicit opioid use who received the Disclosing Recovery intervention reported greater closeness to and social support from their planned disclosure recipient than those who received the comparator condition.

Conclusions:

The Disclosing Recovery intervention appears to be an acceptable, feasible, and appropriate patient decision aid for addressing disclosure processes among people in treatment for OUD. Moreover, preliminary results suggest that it shows promise in improving relationship closeness and social support in patients without illicit opioid use. More testing is merited to determine the intervention’s efficacy and effectiveness in improving relationship and treatment outcomes for people in treatment for OUD.

Keywords: disclosure, opioid use disorder, patient decision aid, randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

People engaged in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) report discomfort with disclosure (Earnshaw et al., 2019), a social process that involves sharing information about one’s OUD history and/or treatment with others (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). When disclosure goes well, it can lead to important social connection and support that helps to facilitate recovery from OUD (Ariss & Fairbairn, 2020; Kumar et al., 2021). When disclosure goes poorly, it can lead to stigma (e.g., social rejection and/or poor treatment from others) that acts as a pernicious barrier to recovery (Tsai et al., 2019). Although disclosure interventions have shown promise for people with other concealable stigmatized chronic illnesses (e.g., Brohan et al., 2014; Corrigan et al., 2013), none have been evaluated for people in treatment for OUD. The current study therefore evaluated a pilot randomized controlled trial of Disclosing Recovery, a brief disclosure intervention designed to facilitate disclosure decisions and skills among people in treatment for OUD.

Disclosure is a complex social process. It involves a series of decisions including whether, why, what, how, and when to disclose. The Disclosure Process Model suggests that some of these decisions (e.g., regarding reasons why to disclose) impact disclosure recipients’ reactions to disclosures (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). Additionally, disclosure requires an advanced skillset, including communication, de-escalation, and coping skills. The Disclosure Process Model suggests that the ways in which people disclose (e.g., depth, breadth, and duration) further shape responses to disclosures (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). Perhaps because disclosure is a high-stakes and complex social process, many people in recovery from substance use disorders (SUD) struggle with disclosure and remain uncomfortable with disclosure decades into recovery (Earnshaw, Bergman, et al., 2019). Disclosure processes may be particularly challenging for people in recovery from OUD given that OUD is severely stigmatized (Perry et al., 2020) and OUD impacts social cognition and interaction skills (Christie, 2021; Quednow, 2020).

Disclosure interventions exist for people with several concealable stigmatized chronic illnesses, including mental illness (e.g., CORAL: Conceal OR ReveAL [Brohan et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2013]; Honest, Open, Proud [Corrigan et al., 2013; Modelli et al., 2021; Mulfinger et al., 2018]) and HIV (e.g., Gundo-So [Chamber of Confidentiality], [Bernier et al., 2018], TRACK: Teaching Raising, And Communicating with Kids [Murphy et al., 2011]). These disclosure interventions have positive impacts on disclosure decision making and skills, including leading to less disclosure distress, less decisional conflict, and more disclosure self-efficacy (Bernier et al., 2018; Brohan et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2011). Some disclosure interventions lead to more disclosure or less secrecy surrounding one’s illness (Henderson et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2011). Disclosure interventions additionally lead to improved mental health (including reduced depressive symptoms [Mulfinger et al., 2018] and improved emotional functioning [Murphy et al., 2011]) and communication with family members (Murphy et al., 2011). Despite this growing body of evidence that disclosure interventions are beneficial for disclosure processes, relationship outcomes, and mental health, no evidence-based disclosure intervention exists for people in treatment for OUD.

Disclosure interventions that incorporate patient decision aids may be particularly helpful for people in treatment for OUD. People receiving treatment for OUD are diverse in terms of whether they are still using illicit opioids and/or other substances, their goals for treatment, how long they have been in treatment, whether they are receiving medication, whether they identify as being in recovery, and other characteristics (Farré et al., 2002; Frings & Albery, 2015; Rosic et al., 2021). Moreover, people in treatment for SUDs including OUD disclose in a wide range of relationship contexts (e.g., family, friendship, romantic, workplace) and for a variety of reasons (e.g., to be honest, to make amends, for logistical purposes; Earnshaw, Bergman, et al., 2019; Earnshaw et al., 2021). Characteristics of the person disclosing, their reasons for disclosure, the disclosure recipient, and other factors may all shape outcomes of disclosure, including the extent to which the disclosure leads to growing social connection and support versus stigma from disclosure recipients (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). Given this complexity, there may be no clear “right” or “wrong” choice for disclosure decisions. Instead, people in treatment for OUD need to make personalized disclosure decisions based on their own values and needs. Patient decision aids may be useful in this context because they are evidence-based tools designed to help patients make choices among multiple viable options that are guided by their own values and needs (Sepucha et al., 2018).

Disclosing Recovery:

A Decision Aid and Toolkit is a patient decision aid developed to help people in treatment for OUD make key decisions regarding disclosure and build skills to disclose. Primary aims of the current pilot randomized controlled trial were to examine the implementation of the intervention to inform a future efficacy trial. More specifically, this study assessed participants’ perceptions of the intervention’s acceptability (i.e., extent to which intervention is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory), appropriateness (i.e., extent to which intervention is relevant to the problem of disclosure), and feasibility (i.e., extent to which the intervention can be successfully carried out) (Weiner et al., 2017). Secondary aims were to explore the intervention’s impact on quality of the disclosure decision-making process and decision, disclosure rates, and relationship outcomes. Given that people currently using illicit opioids may be at greater risk of experiencing stigma and evidence that opioid use impacts social cognition and interactions (Christie, 2021; Quednow, 2020), the study considered current illicit opioid use as a moderator of the intervention on disclosure rates and relationship outcomes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Intervention Design

This parallel randomized controlled trial randomly assigned participants to receive the Disclosing Recovery intervention versus an attention-control comparator. The two conditions are described below and in Appendix A.

2.1.1. Disclosing Recovery Condition

We adapted the decision aid from CORAL, a decision aid designed to support individuals considering disclosing mental illness to employers or coworkers (Brohan et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2013). The study chose CORAL for adaptation because previous work suggests that individuals with SUD struggle with disclosure decisions (Earnshaw, Bergman, et al., 2019; Earnshaw, Bogart, et al., 2019), and CORAL was developed using the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (i.e., a theory for guiding patients making medical and social decisions; Brohan et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2013; A. M. O’Connor et al., 1998). CORAL is a workbook that guides individuals to consider the pros and cons of disclosure, their disclosure needs, their disclosure values, when to disclose, and to whom to disclose. It incorporates quotes from people with mental illness. At the end, participants record their decision regarding when they will disclose (which can range from on the job application, to at the job interview, to never), to whom they will disclose, what they will say, and with whom they may discuss their decision.

To inform the adaptation of CORAL, Earnshaw et al. conducted a longitudinal mixed-methods study of disclosure processes among people in treatment for OUD (n = 146) (2021). We incorporated key findings from this study into the decision aid. As examples, approach and avoidance goals for disclosure were identified and incorporated into the decision aid to guide participants’ values clarification regarding disclosure. We expanded the targeted disclosure context given that participants were considering disclosing to a wide range of other people. An added coaching component built disclosure skills because participants reported that they were not sure of exactly what to say, how to say it, or how to respond to negative reactions. The patient decision aid includes participant quotes from this study. Several stakeholder groups reviewed the adapted intervention, titled Disclosing Recovery, prior to pilot testing. People receiving OUD treatment, OUD treatment providers, and individuals to whom people have disclosed their OUD recovery responded positively to the structure (e.g., modular format), content (e.g., disclosure examples and patient quotes), and delivery (e.g., paper workbook and worksheet) of the Disclosing Recovery intervention.

Disclosing Recovery is a brief, one-hour intervention accompanied by a workbook and worksheet. It is designed to be facilitated by a counselor or peer, and facilitation does not require specialized training. Following guidance for intervention development and testing (National Institute on Aging, 2022), a member of the study team acted as a facilitator in the current pilot test. The introduction to the workbook notes that it is designed to help people with SUD decide whether to share information about their SUD history and treatment with others. The materials referred to SUDs broadly rather than OUD specifically given that many people in treatment for OUD have experienced another SUD. In part one of the intervention, participants identify one person to whom they are considering disclosing and are guided to make key decisions regarding disclosure to that person. They consider whether and why they should disclose by clarifying their approach and avoidance goals for the disclosure, what or how much they should disclose (i.e., all of the details, some of the details or no details), how to disclose (i.e., in person; over the phone; by text, letter, or email), and whether they are ready to disclose. Approach and avoidance goals include reasons to disclose (e.g., support, honesty) and not to disclose (e.g., judgment, worry), and help participants clarify their goals for and against disclosure. For each decision, the decision aid included example patient quotes. As participants make key decisions regarding disclosures, they record their answers on their worksheet. Part two of the Disclosing Recovery intervention coaches participants to build skills for disclosure. Participants build skills for disclosure even if they decide not to disclose given that they may change their mind or face an unexpected situation in which they feel they should or need to disclose. Participants plan what and how to disclose, construct a social support plan for their disclosure, consider sharing resources with their disclosure recipient (i.e., an informational brochure about OUD and OUD treatment, and a support brochure outlining steps that people can take to support people in OUD recovery), and role play their disclosure. To encourage participants to consider negative outcomes of disclosure, and how they may react to those outcomes, the decision aid shares quotes from patients describing negative outcomes of disclosures (e.g., feelings of frustration, social rejection). By the end of the intervention, participants have a disclosure script and plan that they have practiced and recorded on their worksheet.

2.1.2. Comparator Condition

In the comparator condition, participants could choose between several brief mindfulness videos. We constructed a paper workbook and worksheet wherein participants were introduced to six mindfulness videos from Headspace with different purposes (e.g., “How to Fall in Love with Life”, “How to Achieve your Limitless Potential”) and then choose several videos to watch that best fit their interests. Similar to the Disclosing Recovery intervention, the study prompted participants to reflect on the videos and record their thoughts. Also similar to the Disclosing Recovery intervention, a member of our research team facilitated the comparator condition over an average of one hour.

2.2. Procedures

We conducted this pilot randomized controlled trial in June 2021-August 2022 at a non-profit, community-based behavioral health organization located in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. One clinic associated with the organization recruited all participants. Clients have access to care management, medications for opioid use disorder (methadone, buprenorphine), individual and group counseling, peer-based recovery support services, and integrated services (e.g., infectious disease clinic, perinatal health program, syringe services). We advertised the study via flyers and encouraged interested individuals to contact a research assistant in the waiting room. Passive recruitment strategies (i.e., recruitment flyers) limited interaction with clinic patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were: 18 years or older, currently receiving outpatient treatment at the clinic where the intervention was piloted, were considering disclosing their OUD history and/or treatment to at least one person in the next month, and had access to a phone that could receive text messages and phone calls. The study excluded individuals if they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Interested individuals completed a screener on a tablet computer. If they were eligible to participate, they signed up for their first study appointment with the research assistant.

Individuals received more information about the study at the first appointment and provided informed consent to study procedures. After providing informed consent, they answered survey questions related to their disclosure, completed the intervention (i.e., the Disclosing Recovery intervention or a comparator condition), and then answered a post-intervention survey and brief interview questions related to their reactions to the intervention. The study invited participants to complete a second, follow-up appointment one month later, where they completed additional survey and brief interview questions. We collected all survey data via a tablet computer using the Qualtrics Offline Survey App. Given that COVID-19 continued to impact participants’ clinic attendance during the study period, second appointments could be conducted in person or via telephone. The institutional review board approved all procedures.

Block randomization with a block size of four randomly allocated participants to conditions at a 1:1 ratio. The principal investigator used a random number generator to create the allocation sequence.. The principal investigator did the The study recorded and temporarily covered condition assignments on the back of consent forms. The covering was removed after participants completed the consent process; therefore, the study blinded both the research assistant and participants to condition assignments until after the completion of the consent process.

2.3. Measures

Participants responded to surveys and brief interview questions at the first and second study appointments. The study evaluated primary outcomes (i.e., preliminary intervention efficacy and implementation) at the first study appointment immediately post-intervention delivery and assessed secondary outcomes (i.e., disclosure and relationship) at the second appointment. We collected information used to describe the sample, including participant socio-demographic characteristics, select recovery characteristics (i.e., time in recovery), and planned disclosure recipient characteristics, at the first appointment prior to intervention delivery. We abstracted baseline illicit opioid use from participants’ medical records based on results from urinalysis tests (i.e., positive screen for opiate, fentanyl, and/or oxycodone use) conducted before participants’ first study appointments. Participants’ medical records provided current prescribed medications for opioid use disorder.

2.3.1. Primary Outcomes

The Acceptability of Intervention Measure, Intervention Appropriateness Measure, and Feasibility of Intervention Measure assessed implementation outcomes (Weiner et al., 2017). These measures include five items each that are rated on 5-point Likert-type scales. They were reliable in the current study (acceptability: Cronbach’s α = 0.96; appropriateness: Cronbach’s α = 0.97; feasibility: Cronbach’s α = 0.95). To inform planning for a larger randomized clinical trial, the feasibility of procedures to recruit, randomize, and retain participants as well as collect survey and medical record data were additionally examined (Leon et al., 2011). We therefore examined the CONSORT flow diagram as part of the primary outcome analysis.

2.3.2. Secondary Outcomes

The study measured preliminary intervention efficacy following recommendations for evaluating patient decision aids (Sepucha et al., 2013) and adapted from existing measures of decision quality including the Decisional Conflict Scale (O’Connor, 1995) and the Perceived Involvement in Care Scale (Lerman et al., 1990; see Appendix B). All items were measured on 5-point Likert-type scales. Indicators of quality of the disclosure decision making process included: recognizing that a decision can be made (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.95), feeling informed about options (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.90), feeling clear about values (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.92), discussing goals with provider (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.93), and preferences regarding involvement with decision making (1 item). Indicators of decision quality included informed patient (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.81) and decision certainty (4 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

At their second appointment, participants reported whether they disclosed. Participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition also indicated whether they were ready to disclose in the post-intervention survey at their first appointment. We calculated concordance between whether these participants reported that they were ready to disclose in the post-intervention survey at their first appointment and whether they actually disclosed by their second appointment as an additional indicator of decision quality (Sepucha et al., 2013).

Given that the Disclosure Process Model hypothesizes that goals for and characteristics of disclosures will impact relationship outcomes, participants additionally answered questions about their relationships with the person to whom they had planned to disclose (see Appendix B). They reported how close they felt using three items from the Unidimensional Relationship Closeness Scale (Dibble et al., 2012; Cronbach’s α = 0.92), how much social support they received using three items from the modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (Moser et al., 2012; Cronbach’s α = 0.89), and how much stigma they received using three items from the Methadone Maintenance Stigma Mechanisms Scale (Smith et al., 2019; Cronbach’s α = 0.68). All items were rated on 5-point Likert-type scales.

2.4. Analysis

The study explored participant socio-demographic, recovery, and disclosure recipient characteristics using descriptive statistics. We evaluated primary outcomes with t-test and chi-square tests comparing participants in the Disclosing Recovery versus comparator conditions. The study also explored secondary outcomes with t-test and chi-square tests. Because opioid use is hypothesized to impact interpersonal interactions, we additionally explored whether baseline opioid use moderated associations between intervention assignment with disclosure rates and/or relationship outcomes with logistic regression (for disclosure) and two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA; for relationship outcomes). Logistic regression and ANOVA analyses included the effects of the intervention, baseline opioid use, and the interaction between the intervention and baseline opioid use on the secondary outcomes. We further explored statistically significant associations. Primary analyses included the full sample of participants, and secondary analyses included the full sample of participants for preliminary efficacy analyses or participants who completed the second appointment only for disclosure and relationship outcome analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Participant socio-demographic and recovery characteristics, as well as disclosure recipient characteristics, are in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between participants in the Disclosing Recovery and comparator conditions. Notably, over half of participants in both conditions (56% in Disclosing Recovery and 68% in the comparator) tested positive for baseline illicit opioid use.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic, Recovery, and Disclosure Recipient Characteristics (n=50)

| Characteristic | Disclosing Recovery | Comparator | t-test or X2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % (n) | M (SD) or % (n) | |||

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age | 41.04 (10.94) | 42.04 (11.32) | −0.32 | 0.75 |

| Race | 1.24 | 0.54 | ||

| Black/African American | 12% (3) | 16% (4) | ||

| White | 88% (22) | 80% (20) | ||

| Other | 0% (0) | 4% (1) | ||

| Latinx/Hispanic | 4% (1) | 4% (1) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.78 | ||

| Woman | 52% (13) | 56% (14) | ||

| Man | 48% (12) | 44% (11) | ||

| Relationship Status | 0.26 | 0.88 | ||

| Single | 36% (9) | 32% (8) | ||

| In a Relationship, Dating, or Married | 56% (14) | 56% (14) | ||

| Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | 8% (2) | 12% (3) | ||

| LGBT | 4% (1) | 12% (3) | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| Education | 0.92 | 0.63 | ||

| Less than High School Degree | 20% (5) | 20% (5) | ||

| High School Degree or GED | 40% (10) | 52% (13) | ||

| More than High School Degree | 40% (10) | 28% (7) | ||

| History of Incarceration | 72% (18) | 64% (16) | 0.37 | 0.54 |

| Recovery Characteristics | ||||

| Time in Recovery (years) | 2.05 (2.65) | 1.83 (1.62) | 0.34 | 0.73 |

| Medication for Opioid Use Disorder | 0.76 | 0.38 | ||

| Methadone | 84% (21) | 92% (23) | ||

| Buprenorphine | 16% (4) | 8% (2) | ||

| Opioid Use (Medical Record) | 56% (14) | 68% (17) | 0.76 | 0.56 |

| Disclosure Recipient Characteristics | ||||

| Age | 49.52 (19.09) | 50.64 (17.70) | −0.22 | 0.83 |

| Gender | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||

| Woman | 48% (12) | 52% (13) | ||

| Man | 52% (13) | 48% (12) | ||

| Relationship Type | 6.22 | 0.29 | ||

| Immediate Family | 32% (8) | 28% (7) | ||

| Extended Family | 12% (3) | 25% (6) | ||

| Friend | 38% (7) | 16% (4) | ||

| Romantic Partner | 8% (2) | 16% (4) | ||

| Work Relationship | 8% (2) | 16% (4) | ||

| Other | 12% (3) | 0% (0) | ||

| Relationship Length (years) | 21.28 (19.16) | 23.89 (16.98) | 0.51 | 0.61 |

| Substance Use History | 0.62 | 0.73 | ||

| Past Substance Use | 12% (3) | 20% (5) | ||

| In Recovery | 16% (4) | 16% (4) | ||

| No Past Substance Use | 72% (8) | 64% (16) |

3.2. Primary Outcomes

As shown in Table 2, participants viewed the Disclosing Recovery intervention as more acceptable, feasible, and appropriate than the comparator condition. Scores were close to five, indicating that participants viewed the Disclosing Recovery intervention as highly acceptable, feasible, and appropriate.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics, T-Tests, and Chi-Square Tests of Outcome Measures (n=47–50)

| Characteristic | Disclosing Recovery | Comparator | t-test or X2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % (n) | M (SD) or % (n) | |||

| Post-Intervention Survey (n=50) | ||||

| Implementation | ||||

| Acceptability | 4.82 (0.34) | 3.19 (1.14) | 6.87 | <0.001 |

| Appropriateness | 4.74 (0.46) | 2.93 (1.27) | 6.93 | <0.001 |

| Feasibility | 4.88 (0.32) | 3.78 (0.84) | 6.11 | <0.001 |

| Quality of Decision-Making Process | ||||

| Recognize Decision | 4.49 (0.59) | 1.88 (0.98) | 11.44 | <0.001 |

| Feel Informed about Options | 4.60 (0.56) | 3.14 (0.91) | 6.83 | <0.001 |

| Feel Clear about Values | 4.74 (0.45) | 4.02 (0.81) | 3.83 | <0.001 |

| Discuss Goals with Provider | 4.88 (0.30) | 2.77 (0.98) | 10.27 | <0.001 |

| Involvement in Decision | 1.47 | 0.23 | ||

| Prefer to Decide Myself | 60% (15) | 76% (19) | ||

| Prefer to Decide with Provider | 40% (10) | 24% (6) | ||

| Prefer Provider to Decide | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | ||

| Decision Quality | ||||

| Informed Patient | 4.89 (0.26) | 4.34 (0.52) | 4.72 | <0.001 |

| Decision Certainty | 4.46 (0.50) | 3.82 (0.68) | 3.79 | <0.001 |

| Second Appointment Survey (n=47) | ||||

| Disclosure | 66.7% (16) | 82.6% (19) | 1.57 | 0.21 |

| Relationship | ||||

| Closeness | 4.11 (0.95) | 3.90 (1.28) | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| Social Support | 3.17 (1.17) | 3.29 (1.38) | −0.33 | 0.74 |

| Enacted Stigma | 1.83 (0.72) | 1.91 (1.03) | −0.31 | 0.76 |

As shown in Figure 1, the study screened 98 individuals for eligibility of whom 48 (49.0%) did not meet the study inclusion criteria. The remaining participants (n = 50) were successfully randomized to and fully completed the Disclosing Recovery (n = 25, 50%) or comparator (n = 25, 50%) condition. One participant in each condition was lost to follow-up representing a 96% (n = 48/50) retention rate. Both of these participants had left care. One participant’s data in the comparator condition could not be uploaded from the Qualtrics Offline Survey App. Analyses using post-intervention data collected at the first appointment therefore include n = 25 participants per condition, and analyses using data collected at the second appointment include n = 23–24 participants per condition. There was no item-level missing survey data. That is, participants who completed the first and second appointment surveys responded to all questions. The study successfully abstracted medical record data including urinalysis results for all participants.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

Also as shown in Table 2, participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition reported a higher quality of their decision-making process than participants in the comparator condition in the post-intervention survey. They recognized that they could decide whether and how to disclose (recognize decision), felt informed about their options regarding whether and how to disclose (feel informed), understood whether and how they personally would want to disclose (feel clear about values), and perceived that they were encouraged to talk about their disclosure decision (discussed goals with provider). Most participants in both conditions preferred to make disclosure decisions themselves. Slightly more participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition preferred that their provider be involved in their decision; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition also reported a better decision quality than participants in the comparator condition. They strongly agreed that they could choose whether and how to disclose (informed patient) as well as felt sure about their decision (decision certainty).

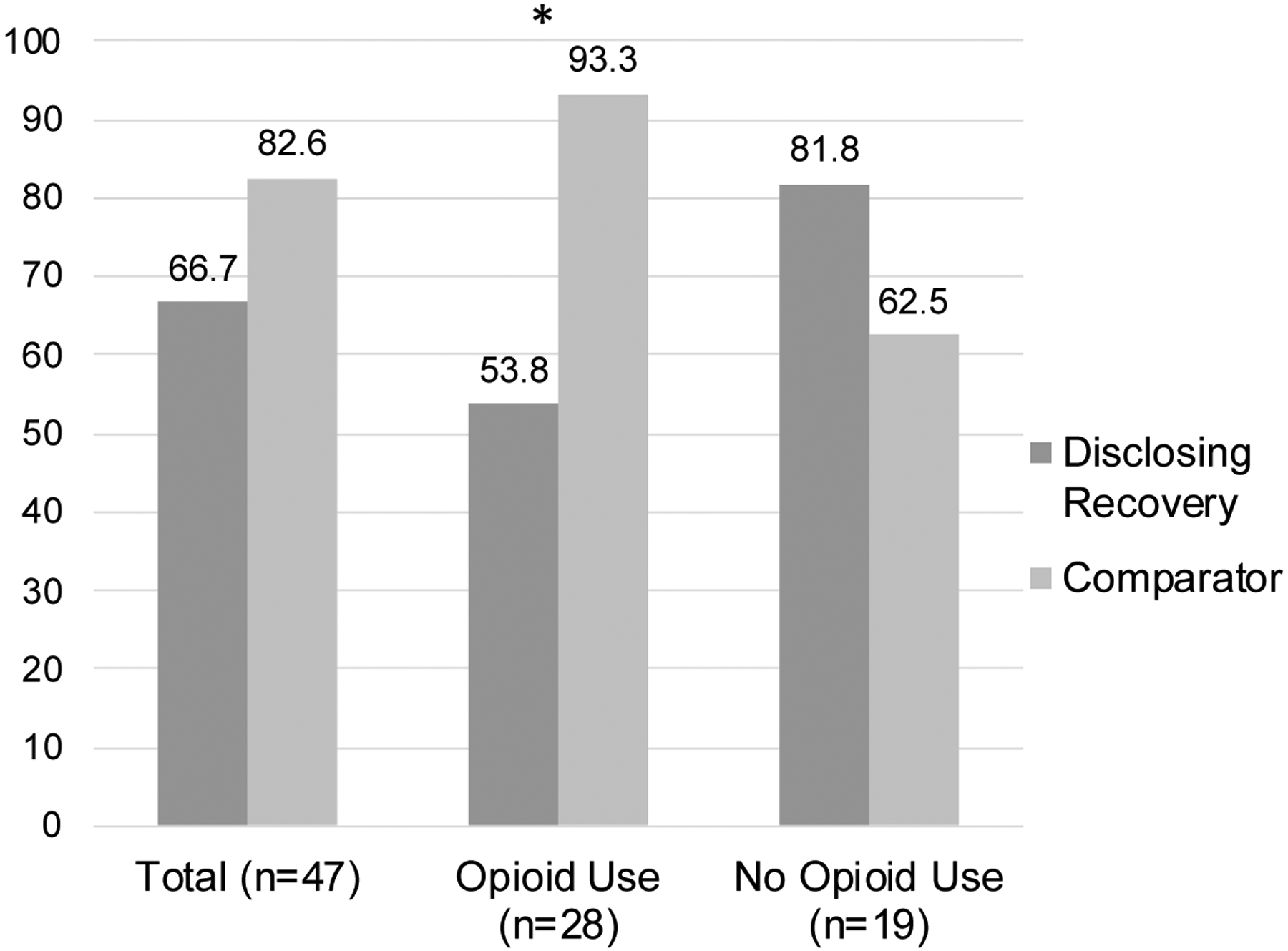

As shown in Figure 2, 66.7% of participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition had disclosed by the second appointment in contrast to 82.6% of participants in the comparator condition. A bivariate comparison between conditions was non-statistically significant (see Table 2). The logistic regression analysis controlling for baseline opioid use suggested that the Disclosing Recovery condition was associated with increased odds of disclosure (OR = 12.0, 95% CI = 1.20–120.08), and that there was an interaction between the intervention condition and baseline opioid use (OR = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.01–0.70). Among participants who tested positive for any illicit opioid use at baseline, there was a statistically significant difference in disclosure rates (χ2[1] = 5.79, p = 0.02) with fewer participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition disclosing than those in the comparator condition. Among participants who did not test positive for illicit opioid use at baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in disclosure rates between the conditions (χ2[1] = 0.89, p = 0.34).

Figure 2.

Disclosure Rates by Condition, Stratified by Opioid Use at Baseline (n=47)

Note: *p < .05

Among participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition, there was additionally an association between whether they reported that they felt ready to disclose in the post-intervention survey and whether they disclosed by their second appointment (χ2[1] = 6.75, p = 0.01). Following the intervention, 50% of participants felt ready to disclose and 50% did not feel ready to disclose or were unsure. More participants who felt ready to disclose went on to disclose (91.7% disclosed) than those who did not feel ready to disclose or were unsure (41.7% disclosed).

T-test comparisons of relationship outcomes between participants in the Disclosing Recovery and comparator conditions were not statistically significant (Table 2). Two-way ANOVA results suggested statistically significant interactions between the intervention condition and baseline illicit opioid use for closeness (F[1, 43] = 4.86, partial η2 = 0.10, p = 0.03) and social support (F[1, 43] = 7.54, partial η2 = 0.15, p = 0.01). As shown in Table 3, we examined pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means to understand the interaction. Among participants with no illicit opioid use at baseline, participation in the Disclosing Recovery condition was associated with greater closeness and social support. Among participants with illicit opioid use at baseline, participation in the Disclosing Recovery condition was not associated with closeness and was marginally associated with less social support. Results of an additional two-way ANOVA suggested that the interaction between intervention condition and baseline opioid use was not statistically significant for enacted stigma (F[1, 43] = 1.61, partial η2 = 0.04, p = 0.21). Although participants in the Disclosing Recovery condition with no illicit opioid use at baseline reported less enacted stigma than participants in the comparator condition with no illicit opioid use at baseline, this difference was not statistically significant (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Pairwise Comparisons of Estimated Marginal Means of Relationship Outcomes at Second Appointment Survey (n=47)

| Opioid Use | Condition | M (SE) | Mdiff (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closeness | ||||

| No Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 3.94 (0.30) | 1.11 (0.46) | 0.02 |

| Comparator | 2.83 (0.35) | |||

| Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 4.26 (0.28) | −0.21 (0.38) | 0.58 |

| Comparator | 4.47 (0.26) | |||

| Social Support | ||||

| No Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 3.18 (0.34) | 1.10 (0.53) | 0.04 |

| Comparator | 2.08 (0.40) | |||

| Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 3.15 (0.32) | −0.78 (0.43) | 0.08 |

| Comparator | 3.93 (0.30) | |||

| Enacted Stigma | ||||

| No Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 1.58 (0.27) | −0.46 (0.41) | 0.26 |

| Comparator | 2.04 (0.31) | |||

| Opioid Use | Disclosing Recovery | 2.05 (0.25) | 0.21 (0.34) | 0.54 |

| Comparator | 1.84 (0.23) |

4. Discussion

Results of this pilot randomized controlled trial suggest that the Disclosing Recovery intervention was viewed as acceptable, appropriate, and feasible by participants, suggesting that it may be successfully implemented in OUD treatment settings. Exploratory secondary analyses further suggest that the intervention has potential to improve the quality of the disclosure decision-making process and decision for people in treatment for OUD. Although disclosure rates and relationship outcomes among participants in the Disclosing Recovery versus comparator conditions were not statistically significantly different overall, analyses accounting for baseline illicit opioid use identified differences by condition. Regarding disclosure rates, participants with illicit opioid use who received the Disclosing Recovery intervention were less likely to disclose than those who received the comparator condition. Regarding relationship outcomes, participants without illicit opioid use who received the Disclosing Recovery intervention reported greater closeness to and social support from their planned disclosure recipient than those who received the comparator condition. These exploratory results suggest that the impact of the Disclosing Recovery intervention on disclosure and relationship outcomes may differ depending on whether individuals are engaged in illicit opioid use. Future trials to evaluate Disclosing Recovery should therefore continue to explore illicit opioid use as a moderator of the intervention’s effects.

These preliminary findings suggest that the Disclosing Recovery intervention may have similarities and differences with previously evaluated disclosure interventions. Similar to other disclosure interventions, the Disclosing Recovery intervention improved disclosure decision making (Bernier et al., 2018; Brohan et al., 2014; Henderson et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2011). Different from other disclosure interventions, which lead to increased disclosure rates (Henderson et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2011), the Disclosing Recovery intervention may have led some participants to not disclose or delay disclosure. As noted earlier, participants engaged in illicit opioid use at baseline were less likely to disclose if they received the Disclosing Recovery intervention. Individuals engaged in illicit opioid use may be both at greater risk of and more vulnerable to stigmatizing reactions to disclosures. For these participants, not disclosing or delaying disclosure may be a protective decision. It is also possible that participants not engaged in illicit opioid use have higher recovery motivation and/or commitment to sobriety, which may impact their orientation towards disclosure. Future research should continue to explore how and why the Disclosing Recovery intervention impacts actual disclosure behaviors among people in OUD treatment with and without current illicit opioid use.

4.1. Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

Results of the current pilot study should be interpreted as preliminary, and further tests of the Disclosing Recovery intervention should be conducted to determine its efficacy and effectiveness. Participants were successfully recruited and randomized in the current study, increasing confidence that future randomized controlled trials of the Disclosing Recovery intervention will be feasible. All patients who were assessed for eligibility agreed to participate, suggesting that the intervention is of interest to patients. Because the study employed passive recruitment strategies, however, the number of eligible individuals who were aware of the intervention but were not interested in participating is unknown. Future studies should estimate interest in the intervention. The small sample size may have led to some wide confidence intervals for statistical tests, which should be interpreted with caution. Participants were recruited from one clinic and over half were engaged in illicit opioid use. More work is needed with larger, more diverse samples to test the generalizability of findings to individuals in other geographic locations and stages of recovery. This pilot used an attention-control comparator condition. Based on recent recommendations, however, a waitlist control or inactive comparator condition may have been more appropriate for early stages of intervention testing (Freedland, 2020; Freedland et al., 2019). Additionally, future research may collect data related to characteristics that may impact participants’ interactions with decision aids (e.g., literacy, prior experience with treatment options; Sepucha et al., 2018).

The participant retention rate (96%) was quite high in this study. Yet, future trials should follow participants for longer periods of time to determine whether and how the intervention impacts disclosure rates and relationship outcomes over longer time horizons. Longitudinal research may additionally be able to provide insight into whether the intervention ultimately impacts treatment and recovery-related outcomes. The evaluation was guided, in part, by the Disclosure Process Model, which suggests that aspects of disclosures may impact responses to disclosures, including relationship outcomes (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). We found preliminary support that a decision aid can lead to improved relationship outcomes for participants not engaged in illicit opioid use. Yet, it is critical that future research seek to understand why the Disclosing Recovery intervention was associated with less social support among participants engaged in illicit opioid use. Although this finding was marginally statistically significant, it merits additional attention and testing to determine whether it replicates and why it may exist. Research with larger sample sizes may also be able to better characterize the mechanisms whereby the intervention impacts relationship outcomes by including measures guided by the Disclosure Process Model (e.g., characteristics of the disclosure event, distress associated with concealing OUD history and/or treatment). The Disclosure Process Model further suggests that disclosures may impact individual-level outcomes over time, such as self-esteem and internalized stigma. Qualitative methods may yield important insight into the impact of the intervention on relationship and individual-level outcomes for participants engaged versus not engaged in illicit opioid use.

4.2. Conclusions

Given recent rapid increases in opioid overdose deaths, innovative solutions are needed to promote recovery among people in treatment for OUD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Although social isolation has been identified as an “important therapeutic target” for SUDs (Volkow, 2020), and evidence suggests that people with OUD are at particularly high risk for social isolation (Barman-Adhikari et al., 2015; Christie, 2021; Heilig et al., 2016), few evidence-based interventions exist to address social isolation among people in recovery from OUD. Disclosing Recovery is a disclosure intervention designed to improve disclosure processes among people in treatment for OUD, with the goal of improving social connection and support among this population. Results of this pilot randomized controlled trial suggests that Disclosing Recovery demonstrates promise, and more testing is warranted to establish its efficacy and effectiveness.

Highlights.

People in opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment struggle with disclosure decisions.

Disclosing Recovery is a patient decision aid for disclosure decisions and skills.

It appears to be acceptable, appropriate, and feasible.

Future trials should examine its impacts on relationship and treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their experiences with the study team and the staff at the treatment center where the study was conducted for their support.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; K01DA042881, VAE) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA, K24AA022136, JFK). Funders were not involved in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; write up of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of its funders.

Appendix A. Summary of Disclosing Recovery and Comparator Conditions

Disclosing Recovery Condition

Participants review topics in a workbook, and then complete activities and record their decisions on an accompanying worksheet.

| Topic | Activities and Decisions |

|---|---|

| Part I: Making Disclosure Decisions | |

| Should I disclose and why? | • Decide on your reasons to disclose. Choose all that apply: |

| □ Honesty | |

| □ Set an Example | |

| □ Other | |

| • Decide on your reasons not to disclose. Choose all that apply: | |

| □ Worry | |

| □ Other | |

| What should I disclose? | • Decide on amount of information you will share during disclosure. Choose one: |

| □ Some details | |

| • Identify and record details you will share | |

| • Identify and record details you will not share | |

| How should I disclose? | • Decide on your disclosure mode. Choose one: |

| □ Over the phone | |

| Am I ready to disclose? | • Decide on your readiness to disclose. Choose one: |

| • Decide on your confidence about disclosure. Choose one: | |

| □ Somewhat sure | |

| Summary | • Summarize and reflect on your disclosure decisions |

| Part II: Developing Tools for Disclosure | |

| Plan What to Say | • Review DEAR MAN (Describe, Express, Assert, Reinforce) and examples of disclosures |

| • Plan and record your disclosure script | |

| Prepare for How to Disclose | • Review DEAR MAN (stay Mindful, Appear confident, Negotiate) strategies |

| • Identify and record strategies you will use | |

| Prepare for Negative Outcomes | • Plan for building social support to bookend your conversation |

| • Identify and record a person who you will talk to before and after the disclosure | |

| Consider Sharing Resources | • Decide whether you will share brochure on how to provide support to people in recovery from substance use disorders. Choose one: |

| □ Do not share brochure | |

| • Decide whether you will share informational brochure about opioid use disorder recovery and treatment. Choose one: | |

| □ Do not share brochure | |

| Role Play Disclosure | • Role play a supportive disclosure and a non-supportive disclosure |

| Summary | • Summarize your disclosure plan |

Comparator Condition

Participants decide on which mindfulness video they would like to watch, and then complete activities in an accompanying worksheet. All participants watch the “How to get started” video before choosing a video.

| Decisions | Activities |

|---|---|

| × How to get started |

|

| □ How to let go |

|

| □ How to fall in love with life |

|

| □ How to deal with stress |

|

| □ How to be kind |

|

| □ How to deal with pain |

|

| □ How to achieve your limitless potential |

|

Appendix B. Measures adapted for the current study

Quality of Decision-Making Process and Decision Quality

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither disagree nor agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognize Decision: After doing the activity, did you realize that you need to make any decisions related to your disclosure? | ||||||

| 1 | Did the activity help you realize that you needed to decide whether to disclose? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Did the activity help you realize that you needed to decide how much details to disclose? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Did the activity help you realize that you needed to decide how to disclose – face-to-face, over the phone, by text or email? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Feel Informed: After doing the activity, do you understand why other people make decisions about their disclosures? | ||||||

| 1 | I feel I know why other people choose to disclose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I feel I know why other people choose not to disclose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I feel I know why other people disclose all the details, some details, or no details about their history. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I feel I know why other people disclose face-to-face, over the phone, by text or email. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Feel Clear about Values: After doing the activity, do you understand why you personally would make decisions about your own disclosure? | ||||||

| 1 | The reasons why I personally would want to disclose are clear to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | The reasons why I personally would not want to disclose are clear to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | The reasons why I personally would want to share more details are clear to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | The reasons why I personally would want to share fewer details are clear to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | The reasons why I personally would want to disclose face-to-face, over the phone, by text or email are clear to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Discuss Goals with Provider: Please answer these questions about the counselor, or person who did the activity with you. | ||||||

| 1 | The counselor encouraged me to talk about my reasons for and against disclosing. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | The counselor encouraged me to give my opinions about disclosing. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | The counselor gave me an explanation of the different choices I have for disclosing. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Informed Patient: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? | ||||||

| 1 | I can choose whether or not to disclose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I can choose how much detail to disclose: all of the details, some details, or no details. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I can choose how I want to disclose: in person, over the phone, by text, or some other way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I can choose when I’m ready to disclose. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Decision Certainty: How sure do you feel about your decisions related to your disclosure? | ||||||

| 1 | I know whether I want to disclose or not. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I know how much detail I want to disclose: all of the details, some details, or no details. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I know how I want to disclose: in person, over the phone, by text, or some other way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I know whether I am ready to disclose or not. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Be Involved

Which of the following best represents how you’d like to make decisions about your disclosures?

□ I prefer to make decisions about my disclosures by myself.

□ I prefer to make decisions about my disclosures with my counselor or therapist.

□ I prefer for my counselor or therapist make decisions about my disclosures for me.

Closeness

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | My relationship with this person is close. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | This person and I talk about important personal things. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | This person and I do a lot of things together. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Social Support

| Thinking about (name)… | None of the time | A little of the time | Some of the time | Most of the time | All of the time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | How often do you turn to this person for suggestions on how to deal with your personal problems? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | How often do you ask this person for help when you need it? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | How often do you turn to this person to do things to help you get your mind off things? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Enacted Stigma

| How often has (name) treated you this way? | Never | Not often | Somewhat often | Often | Very often | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | How often have they thought that you’re still a drug user? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | How often have they not supported your medication? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | How often have they thought you cannot recover? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report. The authors do not have a financial interest in the decision aid itself.

Note: The Disclosing Recovery workbook and worksheet is available from the first author on request.

Clinical Trial Identifier: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04836247

References

- Ariss T, & Fairbairn CE (2020). The effect of significant other involvement in treatment for substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(6), 526–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E, Winetrobe H, & Petering R (2015). Social network correlates of methamphetamine, heroin, and cocaine use in a sociometric network of homeless youth. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(3), 433–457. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Yattassaye A, Beaulieu-Prévost D, Otis J, Henry E, Flores-Aranda J, Massie L, Préau M, & Keita BD (2018). Empowering Malian women living with HIV regarding serostatus disclosure management: Short-term effects of a community-based intervention. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(2), 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Henderson C, Slade M, & Thornicroft G (2014). Development and preliminary evaluation of a decision aid for disclosure of mental illness to employers. Patient Education and Counseling, 94(2), 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Opioids: Data overview. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/data/

- Chaudoir S, & Fisher JD (2010). The Disclosure Process Model: Understanding disclosure decision-making and post-disclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 236–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie NC (2021). The role of social isolation in opioid addiction. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(7), 645–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA, & Rusch N (2013). Reducing self-stigma by Coming Out Proud. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibble JL, Levine TR, & Park HS (2012). The Unidimensional Relationship Closeness Scale (URCS): Reliability and validity evidence for a new measure of relationship closeness. Psychological Assessment, 24(3), 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Menino DD, Kelly JF, Chaudoir SR, Reed NM, & Levy S (2019). Disclosure, stigma, and social support among young people receiving treatment for substance use disorders and their caregivers: a qualitative analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(1535–1549). 10.1007/s11469-018-9930-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Bergman BG, & Kelly JF (2019). Whether, when, and to whom?: An investigation of comfort with disclosing alcohol and other drug histories in a nationally representative sample of recovering persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Sepucha KR, Laurenceau J-P, Subramanian SV, Brousseau NM, Chaudoir SR, Hill EC, Morrison LM, & Kelly JF (2021). Disclosure processes as predictors of relationship outcomes among people in recovery from opioid use disorder: A longitudinal analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 228, 109093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré M, Mas A, Torrens M, Moreno V, & Camí J (2002). Retention rate and illicit opioid use during methadone maintenance interventions: a meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 65(3), 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedland KE (2020). Purpose-guided trial design in health-related behavioral intervention research. Health Psychology, 39(6), 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedland KE, King AC, Ambrosius WT, Mayo-Wilson E, Mohr DC, Czajkowski SM, Thabane L, Collins LM, Rebok GW, Treweek SP, Cook TD, Edinger JD, Stoney CM, Campo RA, Young-Hyman D, Riley WT, & National Institutes of Health Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Expert Panel on Comparator Selection in Behavioral and Social Science Clinical Trials. (2019). The selection of comparators for randomized controlled trials of health-related behavioral interventions: recommendations of an NIH expert panel. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 110, 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings D, & Albery IP (2015). The social identity model of cessation maintenance: Formulation and initial evidence. Addictive Behaviors, 44, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Epstein DH, Nader MA, & Shaham Y (2016). Time to connect: Bringing social context into addiction neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(9), 592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, Dockery L, Farrelly S, Murray J, & Murphy C (2013). Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: Feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(5), 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Oles W, Howell BA, Janmohamed K, Lee ST, Funaro MC, O’Connor PG, & Alexander M (2021). The role of social network support in treatment outcomes for medication for opioid use disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 127. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, & Kraemer HC (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(5), 626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman CE, Brody DS, Caputo GC, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, & Wolfson HG (1990). Patients’ perceived involvement in care scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 5(1), 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modelli A, Candal Setti VP, van de Bilt MT, Gattaz WF, Loch AA, & Rössler W (2021). Addressing mood disorder diagnosis’ stigma with an Honest, Open, Proud (HOP)-Based intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, & Clough-Gorr KM (2012). The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: Psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65, 1107–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulfinger N, Müller S, Böge I, Sakar V, Corrigan PW, Evans-Lacko S, Nehf L, Djamali J, Samarelli A, Kempter M, Ruckes C, Libal G, Oexle N, Noterdaeme M, & Rüsch N (2018). Honest, Open, Proud for adolescents with mental illness: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(6), 684–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Armistead L, Marelich WD, Payne DL, & Herbeck DM (2011). Pilot trial of a disclosure intervention for HIV+ mothers: The TRACK program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 203–214. 10.1037/a0022896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. (2022). NIH Stage Model for behavioral intervention development. Retrieved December 26, 2022, from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/nih-stage-model-behavioral-intervention-development

- O’Connor AM, Drake ER, Fiset V, Graham ID, Laupacis A, & Tugwell P (1998). The Ottawa patient decision aids. Effective Clinical Practice, 2(4), 163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM (1995). Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Medical Decision Making, 15(1), 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, & Krendl AC (2020). The unique nature of public stigma toward non-medical prescription opioid use and dependence: a national study. Addiction, 115(12), 2317–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB (2020). Social cognition in addiction. In Verdejo-Garcia A (Ed.), Cognition and Addiction: A Researcher’s Guide From Mechanisms Towards Interventions (pp. 63–78). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Rosic T, Naji L, Panesar B, Chai DB, Sanger N, Dennis BB, … & Samaan Z (2021). Are patients’ goals in treatment associated with expected treatment outcomes? Findings from a mixed-methods study on outpatient pharmacological treatment for opioid use disorder. BMJ Open, 11(1), e044017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepucha KR, Borkhoff CM, Lally J, Levin CA, Matlock DD, Ng CJ, Ropka ME, Stacey D, Joseph-williams N, Wills CE, & Thomson R (2013). Establishing the effectiveness of patient decision aids: Key constructs and measurement instruments. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(Suppl 2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepucha KR, Abhyankar P, Hoffman AS, Bekker HL, LeBlanc A, Levin CA, Ropka M, Shaffer VA, Sheridan SL, Stacey D, Stalmeier P, Vo H, Wills CE, & Thomson R (2018). Standards for Universal reporting of patient Decision Aid Evaluation studies: The development of SUNDAE Checklist. BMJ Quailty & Safety, 27, 380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LR, Mittal ML, Wagner K, Copenhaver MM, Cunningham CO, & Earnshaw VA (2019). Factor structure, internal reliability and construct validity of the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Stigma Mechanisms Scale (MMT-SMS). Addiction, 115, 354–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L,M,K, Mcginty EE, Smith LR, Strathdee SA, Wakeman SE, & Venkataramani AS (2019). Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Medicine. 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND (2020). Personalizing the treatment of substance use disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(2), 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, Boynton MH, & Halko H (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(108), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]