Abstract

Six undescribed and six known bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids were isolated from the embryo of Nelumbo nucifera seeds. Their structures were fully characterized by a combination of 1H, 13C NMR, 2D NMR, and HRESIMS analyses, as well as ECD computational calculations. The antiadipogenic activity of 11 alkaloids was observed in a dose-responsive manner, leading to the suppression of lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Luciferase assay and Western blot analysis showed that the active alkaloids downregulated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ, a key antiadipogenic receptor) expression in 3T3-L1 cells. Analysis of the structure–activity relationship unveiled that a 1R,1′S configuration in bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids led to a notable enhancement in antiadipogenic activity. The resistance level against lipid accumulation highlighted a consistent pattern with the suppressive effect on the PPARγ expression. These activity results indicate that alkaloids from the embryo of N. nucifera seeds have a potential of antiobesity effects through PPARγ downregulation.

Obesity can easily lead to a series of diseases such as fatty liver, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, which is regarded as one of the public health problems of global concern.1 Several antiobesity drugs such as orlistat, lorcaserin, semaglutide, and liraglutide are effective therapeutic agents.2 However, they may have a variety of disadvantages including the low response rates, serious side effects, and drug resistance. Therefore, it is necessary to find new and effective antiobesity agents. Many studies have demonstrated that natural products from traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) can exert antiobesity activity through inhibition of adipogenesis.3−5 In recent years, a variety of isoquinoline and bisbenzylisoquinoline (BBI) alkaloids have been reported to have a significant antiadipogenic effect in addition to antidiabetic, antihypertensive, antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activity.6−8 These studies have made it more reliable to find antiobesity agents from isoquinoline alkaloids.

The embryo of Nelumbo nucifera seeds is rich in BBI and aporphine alkaloids,9,10 which are recognized as the main antiadipogenic components in lotus leaf (the dried leaf of N. nucifera, which has been proved to have significant antiobesity function).11−15 Recently, neferine, a BBI alkaloid from the embryo of N. nucifera seeds, has been reported to possess antiadipogenic activity.16 This indicates that the embryo of N. nucifera seeds may have potential in the antiobese function and encouraged us to investigate other alkaloids in the embryo of N. nucifera seeds for a better understanding of the antiobesity benefits of N. nucifera.

In the present work, the CH2Cl2 fraction of an embryo of N. nucifera seeds extract was found to be rich in alkaloids by TLC analysis (Figure S1). Thus, the CH2Cl2 fraction was investigated in this study, and 12 BBI alkaloids were isolated and identified (Chart 1). Subsequently, we assessed the effect of these alkaloids on 3T3-L1 preadipocyte adipogenesis. The luciferase assay on lentivirus (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma [PPARγ] luciferase reporter)-transfected 3T3-L1-Lenti-PPARγ-Luc cells and Western blotting analysis on 3T3-L1 adipocytes were used to explore the inhibition mechanism of the active BBIs.

Chart 1. BBI Alkaloids 1–12.

Results and Discussion

Compound 1 was isolated as a pink amorphous powder, with a positive result to Dragendorff’s reagent (orange red), indicating the presence of an alkaloid skeleton.17,18 HRESIMS and 13C NMR (Table 1) analyses revealed a molecular formula of C39H44N2O6 at m/z 637.3269 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272). The 1H NMR spectrum (Table 2) revealed two N-methyl signals at δH 2.84 and 2.87, four aromatic proton singlets at δH 6.88, 6.81, 6.53, and 6.00, corresponding to two 1,2,4,5-tetra-substituted aromatic rings, a pair of doublets at δH 6.73 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz) and 6.96 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz) of an AA′BB′ system, and an ABX system with δH 6.33 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), and 6.78 (1H, dd, J = 8.3, 1.9 Hz). 13C NMR and DEPT spectra revealed 39 carbon signals, namely 6 methyls, 6 methylenes, 13 methines, and 14 quaternary carbons. These NMR data indicated that 1 has a structure similar to that of neferine (compound 7, a major alkaloid in the embryo of N. nucifera seeds19,20), except for the presence of a trisubstituted olefin (δC 130.2 and 137.2) in 1 and the absence of a C-9 or C-9′ methylene in neferine (7).

Table 1. 13C NMR Data for Compounds 1–7 in CD3ODa.

| position | 1b | 2c | 3b | 4c | 5c | 6b | 7b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65.9, CH | 66.2, CH | 66.1, CH | 65.9, CH | 66.1, CH | 73.6, CH | 65.6, CH |

| 2-NCH3 | 41.2, CH3 | 42.1, CH3 | 40.8, CH3 | 41.1, CH3 | 40.7, CH3 | 44.1, CH3 | 41.0, CH3 |

| 3 | 47.0, CH2 | 47.7, CH2 | 46.7, CH2 | 47.2, CH2 | 46.5, CH2 | 53.1, CH2 | 46.9, CH2 |

| 4 | 24.3, CH2 | 25.7, CH2 | 23.9, CH2 | 24.1, CH2 | 23.8, CH2 | 29.2, CH2 | 24.0, CH2 |

| 4a | 128.7, C | 128.0, C | 127.9, C | 127.8, C | 128.3, C | 129.2, C | 128.0, C |

| 5 | 114.2, CH | 113.9, CH | 114.0, CH | 113.9, CH | 113.8, CH | 114.0, CH | 114.1, CH |

| 6 | 152.2, C | 151.6, C | 152.8, C | 152.2, C | 152.9, C | 151.6, C | 152.1, C |

| 6-OCH3 | 56.5, CH3 | 56.3, CH3 | 56.5, CH3 | 56.4, CH3 | 56.3, CH3 | 56.6, CH3 | 56.6, CH3 |

| 7 | 144.4, C | 144.5, C | 144.6, C | 145.1, C | 143.7, C | 144.6, C | 145.0, C |

| 8 | 121.2, CH | 121.2, CH | 121.8, CH | 120.4, CH | 122.6, CH | 120.9, CH | 120.8, CH |

| 8a | 125.5, C | 129.5, C | 126.0, C | 124.9, C | 124.3, C | 132.0, C | 124.9, C |

| 9 | 40.5, CH2 | 40.6, CH2 | 40.4, CH2 | 40.2, CH2 | 40.1, CH2 | 148.7, C | 40.0, CH2 |

| 10 | 129.3, C | 129.7, C | 128.7, C | 128.8, C | 128.7, C | 132.7, C | 128.8, C |

| 11 | 131.8, CH | 131.7, CH | 131.6, CH | 131.7, CH | 132.1, CH | 130.1, CH | 131.8, CH |

| 12 | 115.2, CH | 114.9, CH | 115.1, CH | 115.2, CH | 114.9, CH | 114.6, CH | 115.2, CH |

| 13 | 160.2, C | 159.8, C | 160.3, C | 160.3, C | 160.2, C | 160.8, C | 160.3, C |

| 13-OCH3 | 55.7, CH3 | 55.6, CH3 | 55.7, CH3 | 55.7, CH3 | 55.7, CH3 | 55.7, CH3 | 55.7, CH3 |

| 14 | 115.2, CH | 114.9, CH | 115.1, CH | 115.2, CH | 114.9, CH | 114.6, C | 115.2, CH |

| 15 | 131.8, CH | 131.7, CH | 131.6, CH | 131.7, CH | 132.1, CH | 130.1, CH | 131.8, CH |

| 16 | 119.3, CH2 | ||||||

| 1′ | 130.2, C | 74.4, CH | 73.9, CH | 73.6, CH | 73.9, CH | 65.9, CH | 65.8, CH |

| 2′ | 64.8, CH2 | ||||||

| 2′-NCH3 | 44.6, CH3 | 44.1, CH3 | 44.0, CH3 | 43.8, CH3 | 40.8, CH3 | 40.9, CH3 | |

| 3′ | 53.4, CH2 | 53.1, CH2 | 53.3, CH2 | 53.5, CH2 | 46.8, CH2 | 46.8, CH2 | |

| 3′-NCH3 | 44.0, CH3 | ||||||

| 4′ | 56.7, CH2 | 29.5, CH2 | 28.8, CH2 | 28.5, CH2 | 28.3, CH2 | 23.6, CH2 | 23.6, CH2 |

| 4a′ | 130.9, C | 128.0, C | 125.6, C | 125.2, C | 123.6, C | 123.7, C | |

| 5′ | 32.5, CH2 | 113.2, CH | 113.9, CH | 112.8, CH | 113.0, CH | 112.7, CH | 112.9, CH |

| 5a′ | 131.1, C | ||||||

| 6′ | 114.9, CH | 149.3, C | 149.7, C | 148.3, C | 148.6, C | 150.5, C | 150.4, C |

| 6′-OCH3 | 56.6, CH3 | 57.1, CH3 | 56.5, CH3 | 56.7, CH3 | 56.5, CH3 | 56.5, CH3 | |

| 7′ | 150.2, C | 149.0, C | 149.3, C | 146.2, C | 146.5, C | 148.8, C | 148.6, C |

| 7′-OCH3 | 56.8, CH3 | 56.4, CH3 | 56.6, CH3 | 56.2, CH3 | 56.1, CH3 | ||

| 8′ | 149.6, C | 111.7, CH | 111.7, CH | 114.6, CH | 114.3, CH | 112.5, CH | 112.6, CH |

| 8a′ | 129.7, C | 127.5, C | 127.8, C | 126.7, C | 123.5, C | 123.6, C | |

| 8′-OCH3 | 56.7, CH3 | ||||||

| 9′ | 114.3, CH | 148.8, C | 148.5, C | 147.7, C | 147.3, C | 40.2, CH2 | 40.0, CH2 |

| 9a′ | 133.0, C | ||||||

| 10′ | 137.2, CH | 132.2, C | 131.8, C | 131.4, C | 131.1, C | 128.2, C | 128.3, C |

| 11′ | 128.3, C | 118.3, CH | 117.8, CH | 118.4, CH | 116.7, CH | 119.1, CH | 120.4, CH |

| 12′ | 118.8, CH | 146.0, C | 146.3, C | 145.6, C | 145.8, C | 147.4, C | 146.2, C |

| 13′ | 146.4, C | 148.0, C | 148.6, C | 148.7, C | 148.5, C | 148.0, C | 148.2, C |

| 14′ | 149.2, C | 116.9, CH | 117.5, CH | 117.5, CH | 117.5, CH | 117.9, CH | 117.9, CH |

| 15′ | 117.2, CH | 123.8, CH | 124.6, CH | 124.4, CH | 124.4, CH | 125.7, CH | 126.6, CH |

| 16′ | 127.5, CH | 117.9, CH2 | 120.0, CH2 | 119.5, CH2 | 121.2, CH2 |

δ in ppm.

Measured at 100 MHz.

Measured at 150 MHz.

Table 2. 1H NMR Data for Compounds 1–7 in CD3ODa.

| position | 1b | 2c | 3b | 4c | 5c | 6b | 7b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.19, dd (7.9, 5.1) | 4.16, dd (9.3, 4.4) | 4.19, m | 4.27, dd (9.3, 4.4) | 4.18, dd (10.1, 3.5) | 4.31, m | 4.34, dd (8.4, 4.1) |

| 2-NCH3 | 2.84, s | 2.84, s | 2.90, s | 2.88, s | 2.90, s | 2.41, s | 2.90, s |

| 3 | 3.58, m | 3.58, m | 3.65, m | 3.63, m | 3.73, m | 3.17, m | 3.60, m |

| 3.27, m | 3.27, m | 3.38, m | 3.35, m | 3.37, m | 2.69, m | 3.31, m | |

| 4 | 3.12, m | 3.14, m | 3.17, m | 3.17, m | 3.21, m | 3.10, m | 3.15, m |

| 3.04, m | 3.03, m | 3.09, m | 3.08, m | 3.17, m | 2.83, m | 3.08, m | |

| 5 | 6.81, s | 6.84, s | 6.87, s | 6.85, s | 6.78, s | 6.86, s | 6.85, s |

| 6-OCH3 | 3.75, s | 3.72, s | 3.80, s | 3.75, s | 3.78, s | 3.75, s | 3.81, s |

| 8 | 6.00, s | 6.01, s | 5.78, s | 5.99, s | 5.65, s | 6.79, s | 6.07, s |

| 9 | 3.25, dd (13.1, 4.4) | 3.22, dd (12.9, 3.5) | 3.24, m | 3.24, dd (13.8, 4.6) | 3.26, dd (13.0, 3.6) | 3.31, m | |

| 2.78, m | 2.98, dd (13.4, 8.5) | ||||||

| 2.89, m | 2.90, dd (13.0, 9.0) | 2.93, dd (13.6, 8.5) | 2.88, m | ||||

| 11 | 6.96, d (8.3) | 6.95, d (8.1) | 6.77, d (8.3) | 6.97, d (8.2) | 6.86, d (8.2) | 7.19, d (8.8) | 6.95, d (8.4) |

| 12 | 6.73, d (8.4) | 6.67, d (8.1) | 6.53, d (8.3) | 6.70, d (8.2) | 6.51, d (8.2) | 6.72, d (8.2) | 6.76, d (8.4) |

| 13-OCH3 | 3.70, s | 3.69, s | 3.63, s | 3.70, s | 3.59, s | 3.67, s | 3.73, s |

| 14 | 6.73, d (8.4) | 6.67, d (8.1) | 6.53, d (8.3) | 6.70, d (8.2) | 6.51, d (8.2) | 6.72, d (8.2) | 6.76, d (8.4) |

| 15 | 6.96, d (8.3) | 6.95, d (8.1) | 6.77, d (8.3) | 6.97, d (8.2) | 6.86, d (8.2) | 7.19, d (8.8) | 6.95, d (8.4) |

| 16 | 5.49, s | ||||||

| 5.21, s | |||||||

| 1′ | 4.18, s | 4.39, s | 4.34, s | 4.54, s | 4.26, m | 4.38, dd (9.5, 4.1) | |

| 2′ | 3.85–3.78, m | ||||||

| 2′-NCH3 | 2.34, s | 2.45, s | 2.42, s | 2.54, s | 2.77, s | 2.90, s | |

| 3′ | 3.03, m | 3.13, m | 3.12, m | 3.21, m | 3.54, m | 3.60, m | |

| 2.54, m | 2.70, m | 2.70, m | 2.89, m | 3.23, m | 3.26, m | ||

| 3′-NCH3 | 2.87, s | ||||||

| 4′ | 3.33, m | 2.76, m | 2.89, m | 2.81, m | 2.94, m | 3.03, m | 2.95, m |

| 3.23, m | 2.64, m | 2.72, m | 2.67, m | 2.77, m | 2.91, m | 2.91, m | |

| 5′ | 2.99, m | 6.64, s | 6.72, s | 6.64, s | 6.74, s | 6.71, s | 6.75, s |

| 6′ | 6.88, s | ||||||

| 6′-OCH3 | 3.82, s | 3.86, s | 3.85, s | 3.95, s | 3.80, s | 3.82, s | |

| 7′-OCH3 | 3.87, s | 3.63, s | 3.57, s | 3.49, s | 3.50, s | ||

| 8′ | 6.67, s | 6.73, s | 6.60, s | 6.67, s | 5.96, s | 5.97, s | |

| 8′-OCH3 | 3.54, s | ||||||

| 9′ | 6.53, s | 3.13, m | 3.26, dd (13.9, 4.5) | ||||

| 2.81, m | |||||||

| 2.91, m | |||||||

| 10′ | 6.83, s | ||||||

| 11′ | 6.60, d (2.1) | 6.29, d (2.0) | 6.49, d (1.9) | 6.10, d (1.9) | 6.27, d (2.0) | 6.29, d (2.0) | |

| 12′ | 6.33, d (1.9) | ||||||

| 14′ | 6.75, d (8.4) | 6.79, d (8.4) | 6.77, d (8.4) | 6.82, d (8.3) | 6.85, d (8.3) | 6.86, d (8.1) | |

| 15′ | 6.75, d (8.4) | 7.04, dd (8.4, 2.1) | 7.07, dd (8.3, 2.0) | 7.00, dd (8.4, 1.9) | 7.04, dd (8.4, 1.8) | 6.73, m | 6.80, m |

| 16′ | 6.78, dd (8.3, 1.9) | 5.55, s | 5.60, s | 5.56, s | 5.62, s | ||

| 5.26, s | 5.38, s | 5.27, s | 5.44, s |

δ in ppm, J in Hz.

Measured at 400 MHz.

Measured at 600 MHz.

The correlation of 3′-N-CH3 (δH 2.87) to C-2′ and C-4′ (δC 56.7) as well as that of the olefinic proton (δH 6.83) to C-1′ (δC 130.2) and C-2′ (δC 64.8) in the HMBC spectrum suggested the presence of a seven-membered nitrogen heterocycle (Figure 1). Furthermore, the correlation of H-10′ (δH 6.83) to C-1′ and C-2′ as well as that of H-16′ (δH 6.78) to C-10′ (δC 137.2) indicated a bond between a 1,2,4-trisubstituted aryl unit with the seven-membered nitrogen heterocycle at C-1′.21 The HMBC correlations of 2-NCH3 (δH 2.84) to C-1 (δC 65.9) and C-3 (δC 47.0); H-5 (δH 6.81) to C-4 (δC 24.3), C-7 (δC 144.4), and C-8a (δC 125.5); H-8 (δH 6.00) to C-1 (δC 65.9), C-4a (δC 128.7), and C-6 (δC 152.2); H-12/14 (δH 6.73) to C-10 (δC 129.3); and H-11/15 (δH 6.96) to C-9 (δC 40.5) and C-13 (δC 160.2), along with the correlated spectroscopy (COSY) cross-peaks of H-3 (δH 3.58/3.27)/H-4 (δH 3.12/3.04) and H-1 (δH 4.19)/H-9 (δH 3.25/2.89), revealed the presence of a second benzylisoquinoline unit in 1.

Figure 1.

Key 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1–6 and NOESY correlations of 2–5.

The ECD spectrum estimated using TDDCT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G+(d,p) level was consistent with the experimental CD spectrum, revealing the absolute configuration of 1 as 1R (Figure 2). Therefore, the structure of 1 was determined and named azepinneferine A.

Figure 2.

Experimental and calculated ECD spectra of compounds 1–6.

Compounds 2 (m/z 637.3284 [M + H]+, calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272) and 3 (m/z 637.3272 [M + H]+, calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272) had an identical molecular formula (C39H44N2O6,) based on the HRESIMS and 13C NMR analyses. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 revealed four O-methyl signals at δH 3.63 (3H, s), 3.69 (3H, s), 3.72 (3H, s), and 3.82 (3H, s); two N-methyl signals at δH 2.84 (3H, s) and 2.34 (3H, s); four aromatic proton singlets (δH 6.84, 6.67, 6.64, and 6.01); an ABX spin system at δH 6.60 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 6.75 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), and 7.04 (1H, dd, J = 8.3, 2.0 Hz); and an aromatic AA′BB′ system at δH 6.67 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz) and 6.95 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz). Its 13C NMR and DEPT spectra showed 39 carbons, 6 methyl groups, 6 methylenes, 13 methines, and 14 quaternary carbons. These 1D NMR data revealed the presence of BBI alkaloids.19,20,22,23 Furthermore, the 13C NMR data of 2 are nearly identical to those of neferine (7), except for the absence of a CH2 signal in the benzyl moiety and the presence of a terminal double bond carbon signal at δC 117.9 and 148.8. This finding suggested that the methylene group on the benzyl moiety (C-9 or C-9′) in neferine is replaced by a double bond in 2. The HMBC correlations of H-16′ (δH 5.55/5.26) to C-1′ (δC 74.4) and C-10′ (δC 132.2) indicated that the terminal double bond is at C-9′. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of 2 and 3 were similar, except for the difference in their terminal double bond signals (C-16′: δC 117.9 for 2 and 120.0 for 3), indicating that they have an identical two-dimensional structure.

In the NOESY spectrum, the correlations of H-1 (δH 4.16)/2-NCH3 (δH 2.84)/H-11 (δH 6.95)/H-8′ (δH 6.67)/H-1′ (δH 4.18) in 2 revealed a syn-periplanar relationship between H-1 and H-1′, which showed an identical relative configuration with 1R,1′R-neferine.20,24,25 The CD spectrum of 2 showed positive Cotton effects at 212 nm (Δε = +26.2) and 273 nm (Δε = +4.8) and negative Cotton effects at 230 nm (Δε = −25.0) and 290 (Δε = −2.2), which was consistent with the theoretical ECD curve. This information indicated the absolute configuration of 2 was 1R,1′R. In addition, the NOESY spectrum of 3 exhibited correlations of H-1 (δH 4.19)/2-NCH3 (δH 2.90)/H-11 (δH 6.77) and H-1′ (δH 4.39)/H-8′ (δH 6.73), but not between H-11 (δH 6.77) and H-8′ (δH 6.73), which revealed there was not a syn-periplanar relationship between H-1 and H-1′ and indicated a diastereoisomeric relationship between 2 and 3. Furthermore, the specific rotation [α]25D = −58.6 of 2 and [α]25D = −6.7 of 3, and the close HPLC retention times (tR = 23.110 and 21.934 min for 2 and 3, respectively) (Figure S2), as well as the asymmetric CD curves between 2 and 3, further suggested that these compounds were diastereomers. The theoretically estimated ECD spectrum at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level confirmed the absolute configuration of 3 as 1R,1′S. Thus, 2 and 3 were named 1R,1′R-neoneferine A and 1R,1′S-neoneferine A, respectively.

Compounds 4 (m/z 623.3118 [M + H]+, calcd for C38H43N2O6, 623.3116) and 5 (m/z 623.3143 [M + H]+, calcd for C38H43N2O6, 623.3116) also had an identical molecular formula based on the HRESIMS and NMR results. The NMR spectra of 4 and 5 closely resemble those of 2 and 3, except for the lack of an HMBC correlation between C-7′ and a −OCH3 group, suggesting the absence of a methoxy group at C-7′. HMBC correlations of 13-OCH3 to C-13, 6-OCH3 to C-6, and 6′-OCH3 to C-6′ were observed for both 4 and 5. The only difference between their 13C NMR spectra was the C-8a′ signal (δC 127.8 for 4 and δC 126.7 for 5), similar to that observed for 2 and 3 at C-8a′, indicating the same two-dimensional structure and that they could be C-1′ diastereomers. Besides, the NOESY correlation between H-11 and H-8′ only showed in 4 but not in 5. The CD spectrum of 4 is similar to that of 2, where the Cotton effect was negative at 231 nm (Δε = −10.2) and 290 nm (Δε = −0.8) and positive at 213 nm (Δε = +8.7) and 274 nm (Δε = +1.3), implying a 1R,1′R configuration. The CD spectrum of 5 is similar to that of 3, for which the Cotton effect was positive at 297 nm (Δε = +3.2) and negative at 209 nm (Δε = −18.5), 232 nm (Δε = −8.2), and 287 nm (Δε = −1.1), implying a 1R,1′S configuration. Thus, 4 and 5 were named 1R,1′R-neoisoliensinine A and 1R,1′S-neoisoliensinine A, respectively.

Compound 6 presented a molecular formula C39H44N2O6 at m/z 637.3262 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272) based on its HRESIMS analysis. The 1D NMR spectra of 6 and 3 are nearly identical, and their molecular formulas were the same. However, the HMBC correlation of H-16 (δH 5.49/5.21) to C-1 (δC 73.6) and C-10 (δC 132.7) for 6 suggested that a terminal double bond is present at C-9 of the structure in 6 rather than that at C-9′ in 3. The CD spectrum of 6 was similar to that of 3, with a Cotton effect positive at 298 nm (Δε = +0.5) and negative at 209 nm (Δε = −15.6), 236 nm (Δε = −3.6), and 287 nm (Δε = −2.6), implying a 1R,1′S configuration. Therefore, 6 was named 1R,1′S-neoneferine B.

By comparing the NMR data of alkaloids 7–12 with previously reported data, we identified 7 as neferine,228 as 1′-epi-neferine,229 as liensinine,2310 as isoliensinine,2311 as nelumboferine,26 and 12 as nelumborine A.26

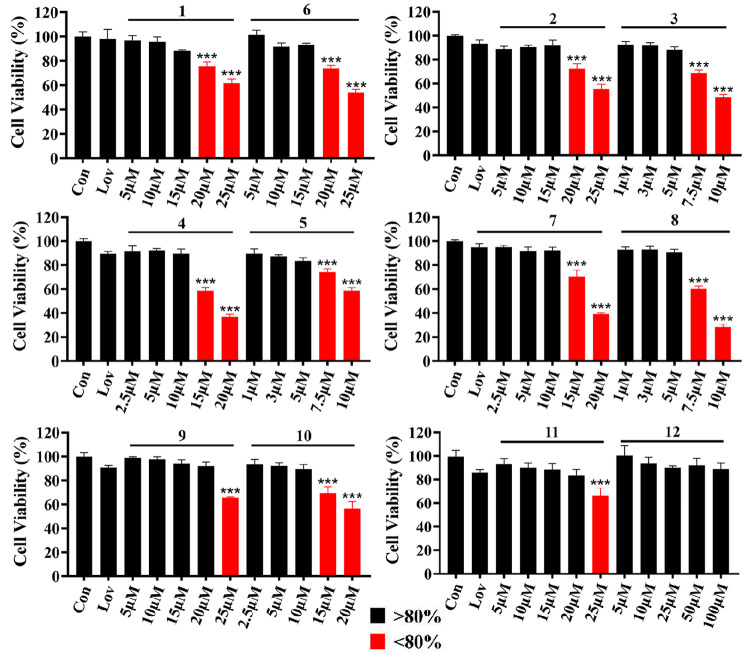

The antiadipogenic activities of 1–12 were estimated from the inhibition of lipid aggregation in 3T3-L1 cells. The CCK-8 assay was used to estimate the cytotoxicity of 1–12 in 3T3-L1 cells (Figure 3). Further experiments were conducted with noncytotoxic concentrations of 1–12. Alkaloids 1–11 significantly inhibited lipid accumulation in a dose-dependent response (Table S1, Figure 4A,B, and Figure S3), suggesting an antiadipogenic activity. The stereoisomers 2/3, 4/5, and 7/8 showed structure–activity relationships for cytotoxicity and antiadipogenic activity. The maximum noncytotoxic concentration for 3, 5, and 8 was 5 μM, which is lower than that for 2, 4, and 7 (15, 10, and 10 μM, respectively). The antiadipogenic activities of 3, 5, and 8 at 5 μM were 40.2%, 36.2%, and 35.9%, respectively, significantly higher than those of 2 (22.4%), 4 (23.5%), and 7 (25.1%) (P < 0.001). Therefore, although the 1R,1′S configuration increases the cytotoxicity, it also significantly increases the antiadipogenic activity. In addition, alkaloids 3, 5, and 8 also showed significantly higher antiadipogenic activities than that of lovastatin at 5 μM (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity effect of alkaloids 1–12 on 3T3-L1 cells (n = 3, mean ± SD). Lov, 5 μM of lovastatin. Significance is denoted as ***P < 0.001 vs Con.

Figure 4.

Effect of alkaloids 1–11 on the accumulation of intracellular lipids in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. (A) Measurement of lipid droplets using Nile Red staining. (B) Determination of the relative inhibitory rate of antiadipogenesis of 1–11, established by comparing the fluorescence intensity with the model group. Significance is denoted as ***P < 0.001 vs M (model group) and ###P < 0.001. Control represents undifferentiated group. Lov, 5 μM of lovastatin. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

PPARγ is a crucial transcription factor in cellular differentiation27 and plays a key role in adipocyte production as well as glucose and lipid metabolism. Suppressing 3T3-L1 preadipocyte expression of PPARγ suppresses adipocyte differentiation, resulting in antiadipogenic activity.28 Lentivirus (PPARγ luciferase reporter)-transfected 3T3-L1-Lenti-PPARγ-Luc cells29 were used for the preliminary verification of the inhibitory effect on PPARγ expression. Neferine (7), a known compound isolated in this study, has been reported to have a PPARγ inhibitory effect, so it was also used as a positive control for the PPARγ inhibition assay.16 The cytotoxicity of the 11 antiadipogenic alkaloids was assessed on 3T3-L1-Lenti-PPARγ-Luc cells (Figure S4). Their maximum noncytotoxic concentrations were consistent with those measured on 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. The luciferase assay revealed a significant inhibitory effect on PPARγ expression in a dose-responsive manner (Figure 5). Among the stereoisomers 2/3, 4/5, and 7/8, with the respective IC50 values of 10.7, 4.6, 8.8, 4.5 μM, 6.1 μM, and 4.5 μM, 3, 5, and 8 with the 1R,1′S configuration demonstrated higher inhibition of PPARγ expression, which was consistent with their inhibitory effects on lipid accumulation.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory impact of 1–11 on PPARγ expression in transfected 3T3-L1-Lenti-PPARγ-Luc cells. Significance is denoted as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs Con (exposed to 0.1% DMSO); PC, positive control. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

In order to gain a deeper understanding of how BBIs 1–11 can impede the PPARγ expression, we utilized Western blotting to evaluate the relative protein levels in the 3T3-L1 adipocytes. We noted that the relative protein levels of PPARγ were diminished in BBI-treated cells dose-responsively (Figure 6A–D). This finding indicates that the isolated BBIs downregulated PPARγ expression, thus inhibiting adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells.

Figure 6.

Influence of alkaloids 1–11 on the protein levels of PPARγ in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. A, 1–3; B, 4–6; C, 7–9; D, 10–11. Significance is denoted as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs M (model group). C represents undifferentiated group. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

The embryo of N. nucifera seeds was mainly used for neuroprotection.30,31 However, it is rich in alkaloids that are highly similar to the leaf of N. nucifera,13−15 suggesting that embryo of N. nucifera seeds may also have antiobesity potential. Based on this, we studied the alkaloids of embryo of N. nucifera seeds and explored their biological activity. In summary, our phytochemical investigation of the embryo of N. nucifera seeds revealed 12 bisbenzylisoquinoline (BBI) alkaloids, including six undescribed compounds. Eleven compounds (1–11) showed significant resistance to lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Structure–activity relationship analysis revealed that the antiadipogenic activity is related to the alkaloids configuration. The antiadipogenic activity of the active BBIs was correlated to their suppressive effect on PPARγ expression. These findings provide a series of BBI alkaloids as candidates for antiadipogenic agents, suggesting that the embryo of N. nucifera seeds could be used as an antiobesity agent in medicine.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

For the measurement of optical rotations, a P-2000 polarimeter (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) was utilized, while circular dichroism (CD) spectra were captured using a J-815 spectrometer instrument (JASCO). Infrared (IR) spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FT-IR spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA). Additionally, UV spectra were recorded by means of a TU-1901 UV–vis spectrophotometer (acquired from Purkinje General Instrument, Beijing, China). An Advance III 400 or 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Fällanden, Switzerland) was utilized to record NMR spectra. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (HRESIMS) spectra were obtained with a 6500 HPLC ESI-QTOF-MS spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) specifically set on the positive-ion mode. To conduct preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), a Puri Master-7000 HPLC system (Shanghai Kezhe Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was utilized. The system incorporated a SymmetryPrep 7 μm C18 column (19 mm × 300 mm, Waters, Milford, MA). In addition, HPLC-diode array detection (DAD) was carried out using an Agilent 1260 series HPLC system. This system was equipped with a SymmetryPrep 5 μm C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, Waters). Open column chromatography (CC) involved the utilization of a combination of 200–300 mesh silica gel (Marine Chemical, Qingdao, China) and Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Silica gel F254 plates (Jiangyou Silica Gel Development, Yantai, China) were employed for thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The eluent of CC was monitored by spraying Dragendorff’s reagent (2 g of bismuth potassium iodide reagent was dissolved in 20 mL of glacial acetic acid and diluted with 50 mL of H2O) on the TLC plates. Imaging of the stained lipid droplets was accomplished through the use of an inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Plant Materials

The embryos of N. nucifera seeds were collected in Guangchang County, Jiangxi, China, in October 2016. Dr. Lihong Wu (Shanghai R&D Center for Standardization of Chinese Medicines) identified them as the dried, unripe cotyledons and radicles of mature Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn seeds. A voucher specimen (lzx160915) was stored at the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Extraction and Isolation

The air-dried embryos of N. nucifera seeds (19 kg) were extracted in 80% EtOH for 2 d three times by cold soaking. The vacuo concentration of the EtOH extract yielded 5 kg of residue. This material was suspended in H2O and subjected to extraction using CH2Cl2. The resulting CH2Cl2 extract (700 g) underwent a series of purification steps utilizing EtOAc, EtOAc–MeOH (15:1), EtOAc–MeOH (1:1), and MeOH on a silica gel column, generating four fractions (Fr.1–Fr.4). These fractions were analyzed by TLC for alkaloid detection. The alkaloid-rich Fr.4 (200 g) eluted through silica gel CC with EtOAc–MeOH–H2O (15:2:1, 10:2:1, and 7:2:1, v/v/v) yielded 11 fractions (Fr.4-1–11). Fr.4-11 (42 g) was further separated via silica gel CC using CHCl3–MeOH (35:1, 25:1, 15:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% NH3 to afford six subfractions (Fr.4-11-1–6). Fr.4-11-1 (4.5 g) was successively separated by chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) and subjected to preparative HPLC using CH3CN–H2O (5:95–25:75, v/v, 12.0 mL/min, 30 min) with 0.01% formic acid to yield 1 (16.0 mg). Fr.4-11-5 (110 mg) was also separated by chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) and subsequently subjected to preparative HPLC (CH3CN–H2O, 5:95–25:75, v/v, containing 0.01% formic acid, 12.0 mL/min, 30 min) to afford 1.8 mg of 4 and 2.9 mg of 5. Fr.4-10 (9.8 g) was separated by silica gel CC and eluted using CHCl3–MeOH (35:1, 25:1, 15:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% NH3, affording six subfractions (Fr.4-10-1–6). Fr.4-10-4 was consecutively separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column (MeOH), eluted through silica gel CC using CHCl3–MeOH (35:1–5:1, v/v) containing 0.1% NH3, and subjected to preparative HPLC using CH3CN–H2O (5:95–25:75, v/v, 12.0 mL/min, 30 min) with 0.01% formic acid, to give 9 (23.0 mg), 10 (50.0 mg), 11 (7.0 mg), and 12 (12.0 mg). Fr.4-10-5 (1.2 g) was separated by chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20 column (MeOH) and afterward subjected to preparative HPLC (CH3CN–H2O, 5:95–25:75, v/v, containing 0.01% formic acid, 12.0 mL/min, 30 min) to yield 2 (3.7 mg), 3 (10 mg), 6 (2.7 mg), 7 (60.0 mg), and 8 (40.0 mg).

Azepinneferine A (1)

Pink amorphous powder; [α]25D −22.2 (c, 0.015, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 220, 276 nm; IR νmax 2922, 1607, 1509, 1462, 1247, 1218 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 219 (+17.2), 237 (−18.8), 296 (+3.8); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 637.3269 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272).

1R,1′R-Neoneferine A (2)

Slightly yellow amorphous powder; [α]25D −58.6 (c, 0.2, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 223, 276 nm; IR νmax: 2936, 1578, 1513, 1431, 1264, 1212, 1123 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 212 (+26.2), 230 (−25.0), 273 (+4.8), 290 (−2.2); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 637.3284 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272).

1R,1′S-Neoneferine A (3)

Slightly yellow amorphous powder; [α]25D −9.7 (c, 0.12, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 223, 278 nm; IR νmax: 2936, 1578, 1513, 1431, 1264, 1212, 1123 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 209 (−37.5), 234 (−14.0), 287 (−1.9), 296 (+2.7); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 637.3272 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272).

1R,1′R-Neoisoliensinine A (4)

Slightly yellow amorphous powder; [α]25D −64.5 (c, 0.05, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 226, 278 nm; IR νmax: 2936, 1578, 1513, 1431, 1264, 1212, 1123 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 213 (+8.7), 231 (−10.2), 274 (+1.3), 290 (−0.8); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 623.3118 [M + H]+ (calcd for C38H43N2O6, 623.3116).

1R,1′S-Neoisoliensinine A (5)

Slightly yellow amorphous powder; [α]25D −7.5 (c, 0.05, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 225, 277 nm; IR νmax: 2936, 1578, 1513, 1431, 1264, 1212, 1123 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 209 (−18.5), 232 (−8.2), 287 (−1.1), 297 (+3.2); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 623.3143 [M + H]+ (calcd for C38H43N2O6, 623.3116).

1S,1′R-Neoneferine B (6)

Slightly yellow amorphous powder; [α]25D −4.6 (c, 0.08, MeOH); UV (CH3OH) λmax 226, 278 nm; IR νmax: 2936, 1608, 1509, 1250, 1228, 1117 cm–1; CD λmax (Δε) 209 (−15.6), 236 (−3.6), 256 (+2.3), 292 (−2.6); 1H and 13C NMR data, Tables 1 and 2; HRESIMS m/z 637.3262 [M + H]+ (calcd for C39H45N2O6, 637.3272).

Computational Analysis

The Spartan 14 software, incorporating the Merck molecular force field (MMFF), was utilized for conformational analysis. The search for conformers with the lowest energy was conducted via density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. A conductor-like polarized continuum model (CPCM) was used with MeOH. Time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level to compute the rotational strengths of 100 electronic excitations. Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra from the dipole-length rotational strengths were simulated using GraphPad Prism 5 plus SpecDis 1.53 software.

Cell Culture and Preadipocyte Differentiation

A modified version of the method reported by Ilavenil et al.32 was used for the cell culture. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (2 × 104) were seeded in 24-well plates with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until 100% confluence. After 2 d of cell confluence, the cells were incubated in a medium of 1 μM rosiglitazone (Rosi), 10 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 mM 3-isobuty-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and 0.25 μM dexamethasone (DEX) for 2 d (named days 0–2). Subsequently, the cells were incubated in insulin (910 μg/mL) for 2 d (named days 2–4). At this stage, the isolated alkaloids were added to the cells to investigate their antiadipogenic activity, and lovastatin was used as a positive control. After 6 d, cells were subjected to two rounds of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washing before being exposed to a Nile Red solution (1 μg/mL) in a light-restricted environment for a duration of 10 min.33 To eliminate the residual dye, the cells underwent an additional two rounds of washing with PBS and were then observed and captured through a fluorescence microscope. The specific excitation and emission wavelengths chosen were 485 and 572 nm, respectively. To quantify the fluorescence intensity, a microplate reader manufactured by BioTek Instruments Inc. (Winooski, VT) was employed. The computation of the differentiation inhibition rate was accomplished by utilizing the subsequent equation:

In the equation, the absorbances of the control well and the sample well are denoted by Ac and As, respectively, serving as the key components for the calculation.

Cell Viability Assay

To ascertain cell viability in the presence of the isolated alkaloids, the assessment was conducted using the CCK-8 kit.16 A 96-well microplate was utilized to culture 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (1 × 103 cells per well). Following a 12 h-incubation period, the cells were exposed to varying concentrations of alkaloids for 48 h. The experimentation was carried out following the specified guidelines provided by the manufacturer. Subsequently, the optical density of the cell cultures at 450 nm was quantified using a Synergy H4 microplate reader, which was manufactured by BioTek (Winooski, VT).

Luciferase Assay

The suppressive effect of the BBI alkaloids on PPARγ expression was estimated using the luciferase assay.29 To establish a positive control, neferine, a known suppressant of PPARγ, was administered. Measurement of the luminescence of the samples was conducted utilizing a Synergy H4 microplate reader, which was procured from BioTek.

Western Blotting Analysis

A modified version of the method reported in ref (34) was used. After the 3T3-L1 adipocytes were subjected to BBIs, the cells were harvested and isolated using a RIPA buffer (Meilunbio) supplemented with PMSF. This process was carried out under a controlled temperature on ice for a duration of 30 min. Following this, the protein concentrations were assessed using the BCA protein assay kit sourced from GBCBIO Technologies (Guangzhou, China). By employing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) provided by Sparkjade Biotechnology (Shandong, China), the samples containing equivalent amounts of protein were separated. Subsequently, the resulting bands were electro-transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane obtained from Genscript (Nanjing, China). To prevent nonspecific interactions, a blocking step involving 5% (w/v) skim milk was implemented and maintained for 2 h at 25 °C. To initiate immunoblotting, the membrane was exposed to primary antibodies for a period of 2 h, followed by the subsequent probing with secondary antibodies that were labeled with horseradish peroxidase for 1 h. The Amersham Imager 600 system from GE Health (MA) was utilized to examine reactive bands of the desired proteins. This detection was achieved through the application of an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent obtained from Sparkjade Biotechnology. The expression level of PPARγ was quantitatively analyzed by grayscale analysis of protein bands using Image J software.

Statistical Analysis

The results of preadipocyte differentiation, the cell viability assay, the luciferase assay, and the relative protein levels were reported as means ± SDs calculated from triplicate experiments (n = 3). To assess any significant variations between the values, the Student’s t test was employed, using a significance level of P ≤ 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the financial support received from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81973475) and the Talents Program of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine (no. 2022rcyb031).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c01290.

Computational ECD data, NMR, HRESIMS, UV, and IR for compounds 1–6; cytotoxicity of compounds 1–12 to 3T3-L1 cells; TLC chromatogram of CH2Cl2 extract and aqueous fraction; HPLC separation of compounds 2–5; effect of 12 on intracellular lipid accumulation; and cytotoxicity of compounds 1–11 to 3T3-L1-Lenti-PPARγ-Luc cells (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ P.Z. and J.L. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kopelman P. G. Nature 2000, 404, 635–643. 10.1038/35007508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q. Y.; Wang Y.; Hao Q. K.; Vandvik P. O.; Guyatt G.; Li J.; Chen Z.; Xu S. S.; Shen Y. J.; Ge L.; Sun F.; Li L.; Yu J. J.; Nong K. L.; Zou X. Y.; Zhu S. Y.; Wang C.; Zhang S. Z.; Qiao Z.; Jian Z. Y.; Li Y.; Zhang X. Y.; Chen K. R.; Qu F. R.; Wu Y.; He Y. Z.; Tian H. M.; Li S. Y. Lancet 2022, 399, 259–269. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Bae S.; Kim Y. S.; Yoon Y. Life Sci. 2011, 89, 388–394. 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W. D.; Gu D. Y.; Li J. N.; Cui K.; Zhang Y. O. PLoS One 2011, 6, 24520. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S. R.; Wu S. H.; Gao B.; Xiao J. R.; Guo Z. Y.; Long S. Y.; Bai Y.; Su Z. Q. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 399–401, 1568–1572. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.399-401.1568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas Z.; Perna S.; Al-thawadi S.; Alalwan T. A.; Riva A.; Petrangolini G.; Gasparri C.; Infantino V.; Peroni G.; Rondanelli M. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110137. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C.; Opatz T. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2019, 81, 1–114. 10.1016/bs.alkal.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V. K.; Kou K. G. M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 7535–7543. 10.1039/D1OB00812A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T. H.; Chen C. M. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1970, 17, 235–242. 10.1002/jccs.197000030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y.; Furutani S.; Itoh A.; Tanahashi T.; Nakajima H.; Oshiro H.; Yamada J. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 1117–1124. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C. J.; Wang J. J.; Chu H. M.; Zhang X. X.; Wang Z. H.; Wang H. L.; Li G. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3481–3494. 10.3390/ijms15033481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J. P.; Hu P. C.; Zhu Y. H.; Xu Y. Y.; Tan Q. S.; Liang X. F. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 584782. 10.3389/fphys.2020.584782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J. S.; Lee Y. J.; Kim K. S.; Kim S. H.; Chang K. J. Nutr. Res. (N.Y.) 2014, 34, 258–267. 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo A.; Jang Y. J.; Ahn J.; Jung C. H.; Choi W. H.; Ha T. Y. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 7, 688–695. 10.12691/jfnr-7-10-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Tao Y.; Qiu L.; Xu W.; Huang X.; Wei H.; Tao X. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4348. 10.3390/nu14204348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M.; Han J.; Lee H. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1858. 10.3390/nu12061858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Wang M.; Li Y.; Zhou M. Z.; Wu T.; Cheng Z. H. Phytochem. Anal. 2021, 32, 242–251. 10.1002/pca.2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Bao M. F.; Wu J.; Chen J.; Yang Y. R.; Schinnerl J.; Cai X. H. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 5938–5942. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. M.; Sun J.; Pan Y.; Zhang J. L.; Xiao M.; Zhu M. S. Fitoterapia 2018, 124, 58–65. 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. X.; Ma S. C.; Mao P.; Wang Y. D. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1755–1758. 10.1016/j.cclet.2016.06.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatenkov A. T.; Soldatova S. A.; Mamyrbekova-Bekro J. A.; Gimranova G. S.; Malkova A. V.; Polyanskii K. B.; Kolyadina N. M.; Khrustalev V. N. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2012, 48, 1332–1339. 10.1007/s10593-012-1141-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura K.; Horii S.; Tanahashi T.; Sugirnoto Y.; Yamada J. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 59–68. 10.1248/cpb.c12-00820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Zhou K. L. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2004, 42, 994–997. 10.1002/mrc.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C.; Liu Y. Y.; Chen L. Q.; Tang D. M.; Zhao Y. L.; Luo X. D. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 16090–16101. 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c03784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Xie B. P.; Han Y. T.; Li Z. Y.; Cheng Y. Y.; Tian L. W. Phytochemistry 2023, 211, 113700. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2023.113700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh A.; Saitoh T.; Tani K.; Uchigaki M.; Sugimoto Y.; Yamada J.; Tanahashi T. Chem.Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 947–951. 10.1248/cpb.59.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.; Elwood F.; Mcnally J.; Weiszmann J.; Lindstrom M.; Amaral K.; Li Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 19649–19657. 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T. N.; Ha T. T.; Nguyen T. H.; Vu T. H.; Truong N. H.; Chu H. H.; Quyen D. V. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4826595. 10.1155/2017/4826595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H. Y.; Tang J. H.; Zhang P. L.; Miao Y.; Wu T.; Cheng Z. H. Phytochemistry 2020, 175, 112363. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. X.; Li X. P.; Wu J. X.; Li J. Y.; Xiao M. Z.; Yang Y.; Liu Z. Q.; Cheng Y. Y. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 266, 113429. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. Y.; Hung C. Y.; Chiu K. M.; Lee M. Y.; Lu C. W.; Wang S. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4130. 10.3390/ijms23084130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilavenil S.; Kim D. H.; Vijayakumar M.; Srigopalram S.; Roh S. G.; Arasu M. V.; Lee J. S.; Choi K. C. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, 38. 10.1186/s40659-016-0098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. L.; Zhao T. H.; Zhang Q.; Wu M.; Zhang Z. Z. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 334–344. 10.1002/cbin.11490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T.; Ito C.; Itoigawa M.; Shibata T. Food Chem. 2022, 377, 131992. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.