Abstract

The interferon (IFN)-induced, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) mediates the antiviral and antiproliferative actions of IFN, in part, via its translational inhibitory properties. Previous studies have demonstrated that PKR forms dimers and that dimerization is likely to be required for activation and/or function. In the present study we used multiple approaches to examine the modulation of PKR dimerization. Deletion analysis with the λ repressor fusion system identified a previously unrecognized site involved in PKR dimerization. This site comprised amino acids (aa) 244 to 296, which span part of the third basic region of PKR and the catalytic subdomains I and II. Using the yeast two-hybrid system and far-Western analysis, we verified the importance of this region for dimerization. Furthermore, coexpression of the 52-aa region alone inhibited the formation of full-length PKR dimers in the λ repressor fusion and two-hybrid systems. Importantly, coexpression of aa 244 to 296 exerted a dominant-negative effect on wild-type kinase activity in a functional assay. Due to its role as a mediator of IFN-induced antiviral resistance, PKR is a target of viral and cellular inhibitors. Curiously, PKR aa 244 to 296 contain the binding site for a select group of specific inhibitors, including the cellular protein P58IPK. We demonstrated, utilizing both the yeast and λ systems, that P58IPK, a member of the tetratricopeptide repeat protein family, can block kinase activity by preventing PKR dimerization. In contrast, a nonfunctional form of P58IPK lacking a TPR motif did not inhibit kinase activity or perturb PKR dimers. These results highlight a potential mechanism of PKR inhibition and define a novel class of PKR inhibitors. Finally, the data document the first known example of inhibition of protein kinase dimerization by a cellular protein inhibitor. On the basis of these results we propose a model for the regulation of PKR dimerization.

Cellular protein kinases play crucial roles in propagating, regulating, and coordinating signals necessary for many seminal biological processes, including metabolism, gene expression, cell growth, differentiation, and development. As a result, protein kinases are subjected to elaborate control mechanisms, including association with domains or subunits that inhibit kinase activity by an autoregulatory process (40, 44) or domains that target the kinase to different subcellular localizations and/or substrates (23, 36). In addition, association with activating or inhibitory proteins (21, 86), reversible protein phosphorylation (19, 32), and multimerization (31, 76) also may regulate kinase activity. While dimerization is a common regulatory mechanism for receptor protein kinases, it is less so for cytosolic nonreceptor protein kinases. The latter class of protein kinases, whose dimerization is implicated in their activation and/or function, includes the cGMP- and cAMP-dependent kinases (81), casein kinase 2 (9), Mst1 kinase (17), Raf-1 kinase (22), and the interferon (IFN)-induced, double-stranded (ds)-RNA-activated kinase (PKR) (60). PKR is novel in that it also regulates its own protein synthesis at the translational level (7, 82).

PKR is a pivotal component of the host antiviral defense system because of its translational inhibitory properties (58, 74). Viral replication produces dsRNA that can bind PKR via two dsRNA-binding motifs (DSRMs) located in the N-terminal portion of the kinase, resulting in autophosphorylation and consequently activation of the enzyme. Activated PKR, in turn, phosphorylates the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF-2α), leading to a complex series of biochemical events that culminate in a dramatic decrease in the initiation of protein synthesis (15, 59). This disables the use of the translational machinery for the production of viral proteins, and hence restricts viral replication within the cell. Due to its function in antiviral defense, PKR is a target of viral and cellular inhibitors (42, 51). The best-characterized cellular protein inhibitor of PKR is P58IPK, which is activated upon influenza virus infection (53, 54). P58IPK appears to be a member of a potential new class of molecular chaperones containing tetratricopeptide repeat motifs and the “J region” of the DnaJ family (52, 62). The non-enzymatic P58IPK protein inhibits both the auto- and trans-phosphorylation activities of PKR (53, 54). However, the exact mode of P58IPK action is not fully understood, although it likely involves direct physical interaction with PKR (25, 69).

In addition to its role in interferon-induced antiviral resistance, there is growing evidence that PKR is involved in the control of cell growth and proliferation. Overexpression of PKR in mouse (46), insect (4), and yeast (14) cells results in severe inhibition of growth due to increased eIF-2α phosphorylation. Furthermore, expression of catalytically inactive mutants of PKR elicits fibroblast transformation and tumor formation upon injection of the cells into nude mice, suggesting that PKR has tumor suppressor properties (6, 46, 61). In support of this view, the P58IPK protein exhibits oncogenic potential; overexpression of the cellular PKR inhibitor causes a transformed phenotype and rapid tumor formation in nude mice (3).

The mechanism(s) by which the functionally defective PKR mutants or wild-type P58IPK induce malignant transformation is not known. One hypothesis is that the PKR mutants inhibit kinase function by forming inactive heterodimers with endogenous wild-type PKR (6, 46). This also raises a fundamental question concerning the role of dimerization on PKR function. Indeed, evidence for PKR dimerization dependent on the DSRMs has been reported (16, 67), although its role in activation and/or function remains unclear (71, 85). Moreover, the role of P58IPK in modulating PKR dimer formation has not been investigated.

Recent efforts to identify the region and mechanism responsible for PKR dimerization have led to conflicting results (16, 66, 67). This controversy can be explained, at least in part, by our demonstration herein that PKR can dimerize through a previously unrecognized region independent of the DSRMs. In addition, we show that P58IPK, but not a nonfunctional form of the protein, prevents PKR dimer formation, suggesting that P58IPK inhibits PKR by converting PKR dimers into stable monomers. To our knowledge, our findings present the first known example of a cytosolic kinase whose activity may be modulated at the level of dimerization through association with a nonenzymatic cellular protein inhibitor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, bacteriophage, and media.

λKH54 and the Escherichia coli strains AG1688 and JH372 (34) were kindly provided by J. C. Hu (Texas A&M University). AG1688, which carries the lacIq gene for maintaining low expression level of the fusion protein, was used to assess immunity to the tester phage, λKH54. λKH54 has undergone a deletion of the cI repressor. JH372 strain, which is a derivative of AG1688, harbors the lacZ gene under the control of the λPR promoter and was used in β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity assays. The E. coli strain XL-1 Blue (Stratagene) was used in the cloning of plasmids. E. coli strains used in this study were propagated in Luria broth (LB) or agar (73) and stored at −70°C in LB containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. All media contained 20 μg of chloramphenicol and/or 50 μg of ampicillin per ml for plasmid selection.

Plasmid constructions.

λ repressor fusions containing various regions of PKR were constructed in the plasmids pC132 and pC168 (55), kindly provided by F. Gigliani (Universita La Sapienza). pC132 (12) carries a fusion between the N-terminal 132 residues of the λ cI repressor (λN) and the Rop protein. Expression of fusion protein is driven by the pLac promoter. pC168, a derivative of pC132, replicates under the control of the replication origin from p15A and is thus a low-copy-number replicon compatible with plasmids (such as pC132 and pGEX2T) that contain the ColE1 origin. Gene fusions were performed by cloning PCR-amplified PKR DNA fragments into the SalI and BamHI sites of pC132 or pC168. Digestion with SalI and BamHI completely removed the Rop part of the fusion in pC132 and pC168 and created the backbone vectors for the construction of the λN fusions. DNA fragments were amplified by PCR with the appropriate primers to introduce the required restriction sites and the stop codon on the DNA fragments. PCR was performed with the Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Plasmid pcDNAI/NEO (Invitrogen) carrying PKR(K296R) (43) was used as a template for the amplification of the various fragments of PKR. DNA fragments obtained by PCR were purified on agarose gels, recovered with the GeneClean II kit (Bio 101), digested, and cloned into the backbone of pC132 or pC168. When possible, internal fragments were released from the resultant plasmids by using the appropriate restriction enzymes and replaced with the corresponding internal fragments from pcDNAI/NEO-PKR(K296R) to minimize PCR-generated mutations. pKH101 expressing only the N-terminal DNA-binding domain of the repressor (λN) was obtained from J. C. Hu.

The glutathione-S-transferase (GST)–PKR(244–296) construct was made by cloning a PCR-amplified DNA fragment with the appropriate primers to introduce the SalI site at the 3′ end and the BamHI site at the 5′ end of the fragment into SalI-BamHI-digested pGEX-4T-3 (Pharmacia Biotech). Construction of GST-P58IPK and GST-ΔTPR6 fusions has been described previously (52, 79). GST-PKR was obtained from B. R. Williams (Cleveland Clinic Foundation). The GST-NS1 and GST-K3L constructs were provided by R. M. Krug (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) and E. Beattie (University of Washington), respectively. pCDNA1/NEO-PKR(296–551) was constructed by cloning a PCR-amplified DNA fragment into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pCDNA1/NEO.

Construction of the PKR(244–551) in pET11a (Novagen) was as described previously (5). To create the GAL4 DNA-binding domain fusion containing PKR(244–551), the NdeI linker sequence, CCATATGG, was ligated into the SmaI site of pGBT9 (Clontech Laboratories) to generate pGBT10. The plasmid insert encoding PKR(244–551) was released from pET11a by cleaving with restriction enzymes NdeI and BamHI, purified on agarose gel, and cloned into NdeI-BamHI-digested pGBT10. Construction of the PKR(K296R) in pGBT10 and GAL4 transcriptional activation domain fusions containing PKR(K296R), -(1–296), -(1–242), -(244–551), -(244–366), -(367–551), and -(244–296) in pGAD425 (Clontech Laboratories) was described previously (25).

pYES2 (Invitrogen) and pYX222 (Novagen) were used for expression of PKR(244–296), P58IPK, and P58IPKΔTPR6 in yeast. pYX222-PKR(244–296) was generated by cloning an EcoRI-BglII fragment from pGAD425-PKR(244–296) (25) into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pYX222. pYES2-PKR(244–296) was constructed by inserting an EcoRI-SalI fragment of pYX222-PKR(244–296) into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pYES2. To create pYX222-P58IPK, an EcoRI-BamHI fragment released from pYX232-P58IPK (27) was cloned into the corresponding sites of pYX222. pYX222-P58IPKΔTPR6 was produced by replacing the BstEII-BamHI fragment of the P58IPK gene in pYX222-P58IPK with a BstEII-BamHI fragment from pET15b-P58IPKΔTPR6 (79). Construction of P58IPK and P58IPKΔTPR6 in pYES2 will be described in a separate report (28).

λ repressor-derived dimerization tests.

Bacterial cells expressing different λN fusions or coexpressing λN and GST fusions were assessed for immunity to λKH54 by cross-streak tests. Phage (∼109 PFU) were striped down the center of an agar plate containing appropriate antibiotics and 100 nM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and allowed to dry. Cells from liquid cultures grown overnight at 30°C in LB supplemented with appropriate drugs, 10 mM MgSO4, and 0.2% maltose were streaked perpendicularly across the phage stripe with a toothpick. For dot plaque assay, lawns of E. coli strains containing various plasmids were infected by spotting with 5-μl aliquots of serial dilutions of phage lysates containing 102 to 106 PFU at 10-fold intervals. Infected lawns were incubated overnight at 30°C. β-Gal assays were done on agar plates layered with 3 ml of top agar containing the appropriate antibiotic(s), 20 μM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal), 100 nM IPTG, and 4 mM phenylethyl-β-d-thiogalactoside. Colony color determination was made after streaking overnight cultures and overnight incubation at 30°C. Plasmids pBR322 and pACYC184 (New England Biolabs) were used as empty vector controls.

Yeast two-hybrid system.

Yeast strain Hf7c (Clontech Laboratories), which carries the HIS3 reporter fused to a GAL1 promoter sequence, was used to assay for protein-protein interactions. The two-hybrid plasmids pGBT10 and pGAD425 were used for construction of GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GBD) and GAL4 transcriptional activation domain (GAD) fusions, respectively. Hf7c was cotransformed with pGBT10-PKR(244–551) and different pGAD425 plasmid constructs as indicated. Transformation was performed by the lithium acetate method (75). Transformants were plated on solid synthetic defined (SD) medium lacking tryptophan (Trp) and leucine (Leu) for selection of double transformants and determination of transformation efficiency. To select for histidine (His)-positive colonies, transformants grown on SD plates lacking Trp and Leu for 3 days at 30°C were streaked onto SD plates lacking Trp, Leu, and His and allowed to grow for 3 to 5 days to deplete endogenous His stores. Colonies were then streaked onto His-containing plates in the presence of 1 mM 3-amino-triazole (3-AT) and incubated for 3 to 5 days at 30°C, after which the plates were scored for growth.

In order to introduce a third protein into the yeast two-hybrid system, we used the plasmid pYX222 (Novagen), which is compatible with the two-hybrid plasmids, pGBT10 and pGAD425. Since pYX222 contains a HIS3+ selectable marker, we used yeast strains SFY526 (Clontech Laboratories) and Y187 (obtained from S. J. Elledge, Baylor College of Medicine) for selection of triple transformants of pYX222, pGBT10, and pGAD425 plasmids. A mating procedure was used to combine all three plasmids. The MATa strain SFY526 was cotransformed with pGBT10-PKR(K296R) and pGAD425-PKR(K296R), and the MATα strain Y187 was transformed with pYX222-P58IPK, pYX222-P58IPKΔ6, or control pYX222. After mating, diploids were streaked on SD plates lacking Trp, Leu, and His. The lacZ reporters integrated in the genome of both strains were used to assess interaction based on a Clontech Laboratories β-Gal assay. Yeast cell extracts were prepared by a glass bead method as described previously (25).

PKR functional assay in yeast.

To determine the effect of overexpression of P58IPK and PKR fragments upon PKR function in vivo, we used a yeast growth suppression assay (26, 71). P58IPK or PKR(244–296) was coexpressed from the pYES2 plasmid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain RY1-1, which carried two copies of human PKR integrated into the LEU2 locus, under the control of the galactose-inducible GAL1-CYC1 promoter (71). RY1-1 exhibits a growth arrest phenotype when grown on minimal medium containing galactose as the sole carbon source due to hyperphosphorylation of yeast eIF-2α by PKR. Thus, the ability of P58IPK or PKR(244–296) to interfere with PKR function was assessed by reversion of the PKR-mediated growth suppression effect and analysis of the eIF-2α phosphorylation state in the appropriate RY1-1 strain harboring the corresponding expression plasmid. Reversal of yeast growth arrest and in vivo eIF-2α phosphorylation status was determined as previously described (26).

In vitro transcription and translation.

Transcripts encoding full-length and mutant PKR were generated essentially as described previously (43) with the T7 promoter of pCDNA1/NEO. Linear transcripts encoding full-length PKR(K296R), PKR(1–242), and PKR(244–551) were prepared from pCDNA1/NEO-PKR(K296R) as described previously (25, 43). Transcripts encoding PKR(296–551) were generated by linearizing pCDNA1/NEO-PKR(296–551) with BamHI digestion. Transcript integrity was monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis. For in vitro translation, 2-μg portions of each in vitro transcription product were used to program a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) in the presence of [35S]methionine as described previously (43). To verify that the translation products were of the expected sizes, an aliquot of each was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and fluorography. Translation product abundance was quantitated by scintillation counting of the trichloroacetic acid-precipitable material from each translation reaction.

Far-Western analysis.

For the detection of in vitro self-interaction of PKR, increasing amounts of purified bacterially expressed GST and GST-PKR(244–296) fusion proteins were size-fractionated by SDS-PAGE on a 14% resolving gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and renatured by overnight incubation in BLOTTO G (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% nonfat milk powder, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 10% glycerol) at room temperature. Filters were then rinsed twice in Hyb75 buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1% nonfat milk powder, 75 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40) and subsequently overlaid with approximately 5.0 × 105 cpm of [35S]methionine-labeled in vitro-translated product from PKR amino acids (aa) 1 to 242, 244 to 551, or 296 to 551 (in fresh Hyb75 buffer) overnight at 4°C. Production, purification, and quantitation of GST fusions and in vitro translation products were carried out as described previously (25). Filters were washed three times with Hyb75 buffer and then subjected to autoradiography.

Immunoblot analysis.

One milliliter of the same overnight culture (3 ml) used for the λ repressor fusion tests was centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 2× SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel (equal amounts of protein estimated by Coomassie blue staining were loaded into each lane) and were then electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblot analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) as described previously (4).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

All DNA constructs were verified to be the correct reading frame by restriction mapping and nucleotide sequence analysis. Sequencing reactions were carried out by using the Applied Biosystems dye terminator system (University of Washington). DNA sequences were analyzed by DNA strider and the Wisconsin GCG package (Madison, Wis.). Homology searches were carried out using the BLAST (1) service at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from Life Technologies.

RESULTS

The λ repressor fusion system detects a novel region involved in PKR dimerization.

We used the λ repressor fusion assay (34) to determine the region(s) responsible for mediating PKR dimerization because it is a relatively simple system in which to study dimer interactions (33). A schematic of the λ repressor fusion system is shown in Fig. 1. We first determined whether full-length PKR dimerized in this assay by scoring for bacterial immunity to λ superinfection. Since wild-type PKR is partly toxic to bacteria (5), we used a catalytically inactive PKR protein, PKR(K296R) (43). This mutant protein is well characterized and retains the ability to dimerize (16, 66, 67) and interact with known PKR partners (10, 25, 26). As revealed by dot plaque assays (Fig. 2A), bacteria expressing a fusion between the λ repressor N-terminal DNA-binding domain (λN) and PKR(K296R), designated λN-PKR(K296R), were clearly less susceptible to λ superinfection than were bacteria expressing λN alone. This indicates successful reconstitution of λN DNA-binding activity promoted by PKR dimerization in E. coli. As an additional test, the plasmid was also introduced into a strain (JH372) that harbors the lacZ reporter gene under the control of the λPR promoter (34). In this scenario, dimerization is assayed by β-Gal activity, whereby functionally reconstituted λN fusions repress expression of lacZ. As shown in Fig. 2B, bacteria expressing a λN fusion of PKR(K296R) or the Rop protein control (12) formed white colonies on indicator plates containing the chromogenic lactose analog X-Gal. On the contrary, bacterial cells that expressed only λN or an empty vector control (pBR322) developed blue colonies.

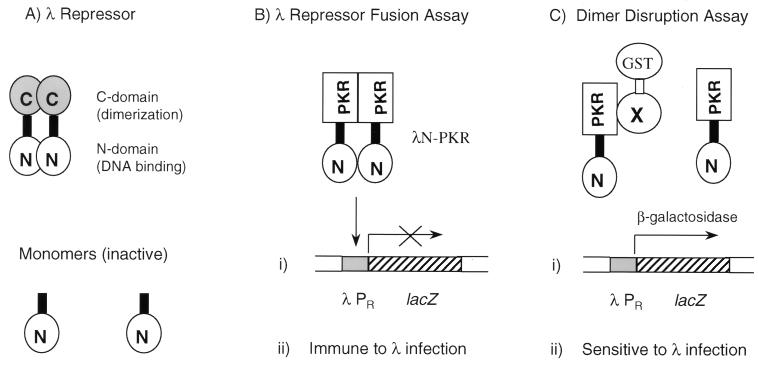

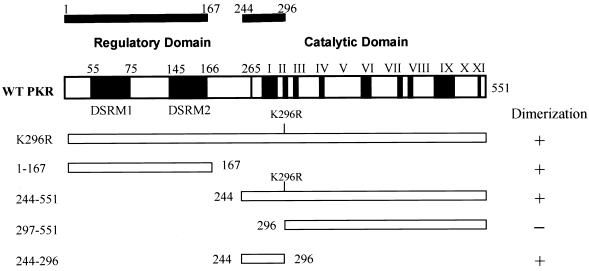

FIG. 1.

λ repressor-derived dimerization tests. (A) Structure and function of λ cI repressor. Wild-type λ cI repressor comprises a N-terminal DNA-binding domain (λN) and a C-terminal dimerization domain that are tethered by a flexible linker. The cI protein binds to λ early promoters as a dimer and represses the transcription of genes required for the phage lytic growth. λN itself is unable to dimerize efficiently and thereby is inactive. (B) Rationale for the λ repressor fusion system. Fusion of a heterologous protein (PKR in this case) containing a dimerization sequence restores dimer formation and DNA binding; cells become immune to λ superinfection and form white colonies on X-Gal medium when carrying a lacZ reporter under the control of λN-PKR. (C) Dimer disruption assay. The coexpression of a protein (a GST fusion in this case) capable of interfering with PKR dimer formation renders cells sensitive to λ superinfection and turns them blue on X-Gal medium due to derepression of reporter expression.

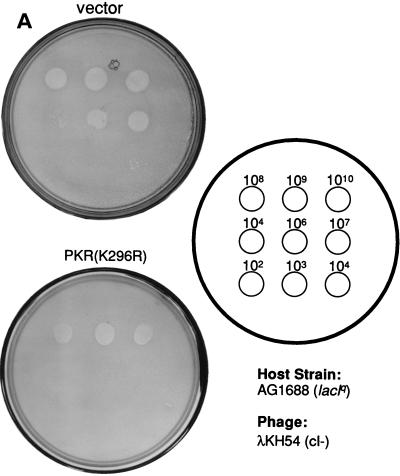

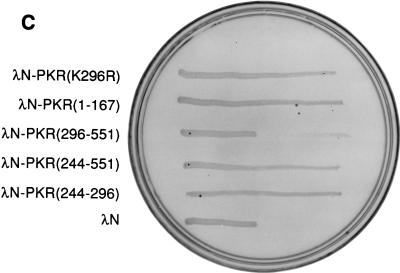

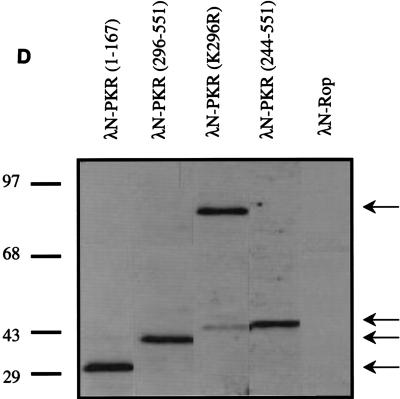

FIG. 2.

Dimerization properties of λN-PKR fusion proteins. (A) Dot plaque assay. Freshly poured lawns of E. coli (strain AG1688) expressing either λN alone or λN-PKR(K296R) fusion were infected by spotting with 5-μl aliquots of 10-fold dilutions of lysates of λKH54. The titer and pattern of the aliquots are indicated. Sensitivity to λ superinfection was scored by evaluating lysis plaques. (B) Repression of β-Gal expression. Repressor activity of the indicated λN fusions was assessed by expression from the λPR lacZ reporter in strain JH372. A functional λN fusion inhibits lacZ expression, resulting in white colony color. In contrast, cells lacking a functional repressor fusion form blue colonies due to β-Gal production. (C) Cross-streak tests. Phages were striped down the center of an agar plate, and cells harboring the plasmids expressing the indicated λN fusions were streaked perpendicularly across the phage stripe. Sensitive cells were scored by assessing lysis by the phage (i.e., the streak disappeared or was noticeably thinner after crossing the phage zone). (D) Expression of λN chimeric proteins containing different PKR mutants. Crude cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 14% gel and visualized by immunoblot analysis by using a polyclonal antibody raised against PKR (4). Detection of λN-PKR(244–296) was unsuccessful by this analysis. The positions of fusion proteins are indicated by arrows. The molecular size standards are shown in kilodaltons.

We next proceeded to map the dimerization region on PKR by generating hybrid proteins consisting of λN and various regions of PKR. Consistent with previous results (16, 67), immunity to phage superinfection by cross-streak tests indicated that dimerization of PKR can occur via the intact DSRMs (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, all λN fusions that contained aa 244 to 296 of PKR also retained their ability to dimerize in this assay. To verify the λ immunity test results produced by the different fusion genes, we assessed lacZ repression by β-Gal assay (Fig. 2B). The results of lacZ repression were consistent with those of λ immunity. Importantly, we confirmed that all fusion proteins accumulated to detectable levels (Fig. 2D), indicating that the loss of repressor activity was not merely due to an absence of protein in the cells. Although λN-PKR(244–296) was not readily detectable by Western analysis due to its small size, positive results obtained from both β-Gal and λ immunity tests (as well as experiments described below) suggest that fusion protein is most likely expressed to sufficient levels. Taken together, these results suggest that PKR dimerization is mediated by at least two different regions, including a previously undescribed region (aa 244 to 296) independent of the DSRMs, as summarized in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

PKR dimerization activity maps two independent regions. Schematic representation of domain structures of wild-type (WT) PKR and PKR deletion constructs used in the λ repressor fusion system. DSRM1 and DSRM2 denote the positions of the dsRNA-binding motifs 1 and 2, respectively. The protein kinase catalytic domain begins at residue 264 and contains the conserved kinase homology subdomains labeled I to XI (2). A summary of the dimerization activity of PKR variants is shown on the right. The solid bars at the top indicate the positions of the dimerization regions of PKR. The positions of terminal amino acids are also indicated.

Residues 244 to 296 mediate dsRNA-independent dimerization of PKR in the yeast two-hybrid system and in far-Western analysis.

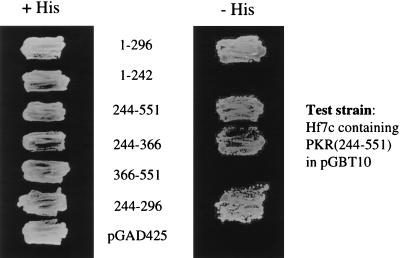

To validate that aa 244 to 296 were indeed involved in PKR-PKR interaction, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to detect protein-protein interactions as a result of their ability to reconstitute the trans-activating function of the GAL4 protein (24). Since PKR dimerization dependent on the DSRMs (aa 1 to 167) has been demonstrated by use of the two-hybrid assay (16, 67), we focused instead on the examination of PKR DSRM-independent interactions. A hybrid protein consisting of PKR aa 244 to 551 and the GAL4 DNA-binding domain was therefore constructed. The ability of this hybrid protein to associate with various regions of PKR fused to the GAL4 transcriptional activation domain was examined. All fusion constructs were expressed to detectable levels in the yeast cells as detected by Western blot analysis (25). As illustrated in Fig. 4, only hybrid proteins containing aa 244 to 296 interacted with PKR(244–551), as indicated by growth on His− medium. Conversely, all cotransfectants grew on medium supplemented with His, indicating that the lack of growth on His− medium is not due to toxicity caused by the overexpression of the relevant hybrid proteins in yeast.

FIG. 4.

PKR self-associates independently of the DSRMs in the yeast two-hybrid system. Yeast strain Hf7c containing pGBT10/PKR(244–251) was transformed with the indicated pGAD425 plasmids containing various PKR mutants or plasmid alone. Cotransformants were replica plated on His+ medium (left) and His− medium (right) containing 1 mM 3-AT. Interaction was scored by growth on His− medium. Western blot analysis indicated that all GAL4 fusions were efficiently expressed in yeast (not shown).

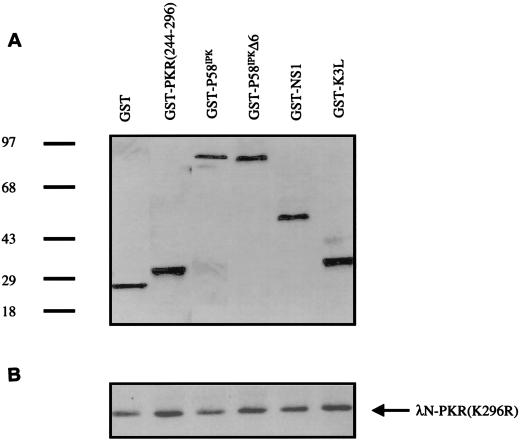

To further demonstrate, by an independent in vitro assay, that aa 244 to 296 interact with PKR independently of the DSRMs, we conducted far-Western experiments. GST-PKR(244–296) or, as a control, GST alone was electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE. Following transfer, the nitrocellulose filters were probed with [35S]methionine-labeled in vitro-translated PKR constructs containing either aa 1 to 242, 244 to 551, or 296 to 551. All translation products were verified by SDS-PAGE and fluorography (25; data not shown). As depicted in Fig. 5, the 35S-labeled PKR(244–551) probe interacted with GST-PKR(244–296) in a concentration-dependent manner but did not interact with GST alone. In contrast, neither a 35S-labeled PKR aa 1-to-242 nor a 35S-labeled PKR aa 295-to-551 probe recognized GST or GST-PKR(244–296). These results collectively support our conclusion that PKR can dimerize in vivo and in vitro independently of the DSRMs and that the dimerization is mediated, at least in part, by aa 244 to 296.

FIG. 5.

Direct PKR-PKR interaction via aa 244 to 296. Increasing amounts (lanes 1 and 6, 10 ng; lanes 2 and 7, 20 ng; lanes 3 and 8, 30 ng; lanes 4 and 9, 40 ng; lanes 5 and 10, 50 ng) of purified bacterially expressed GST and GST-PKR(244–296) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The filter was overlaid with radiolabeled PKR aa 1-to-242 (top), 244-to-551 (middle), or 296-to-551 probe (bottom) and subjected to autoradiography. Arrows indicate positions of GST fusion protein and GST alone.

Coexpression of an amino acid fragment (aa 244 to 296) inhibits both PKR dimerization and kinase function.

To further demonstrate that aa 244 to 296 were sufficient to mediate PKR dimerization, we asked whether coexpression of GST-PKR(244–296) could prevent dimerization of λN-PKR(K296R) in the λ repressor system via the formation of heterodimers (see Fig. 1C). If this were the case, the bacteria would turn blue on X-Gal-treated plates and become sensitive to phage superinfection due to the loss of functional λN-PKR(K296R) dimers (and hence repressor activity). Bacteria producing both λN-PKR(K296R) with GST-PKR(244–296), but not with GST alone, formed blue colonies on X-Gal-treated plates and were sensitive to phage superinfection (Table 1). No repressor activity was observed in bacteria coexpressing an empty vector control (pACYC184) with GST-PKR(244–296). Furthermore, GST-PKR(244–296) did not disrupt dimerization of the Rop protein control in the λ repressor system.

TABLE 1.

Summary of λ resistance and β-Gal expression properties of JH372 or AG1688 clones coexpressing λN-PKR(K296R) and GST fusionsa

| λN fusion | GST fusion | Immunity to λKH54 | Colony color on X-Gal-treated plates | Dimer disruption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKR(K296R) | GST alone | Immune | White | − |

| PKR(K296R) | PKR(244–296) | Sensitive | Blue | + |

| pACYC184 | PKR(244–296) | Sensitive | Blue | − |

| Rop | PKR(244–296) | Immune | White | − |

See Fig. 6.

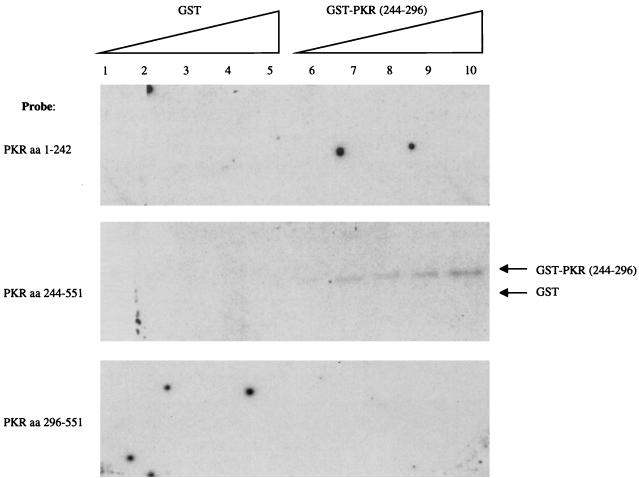

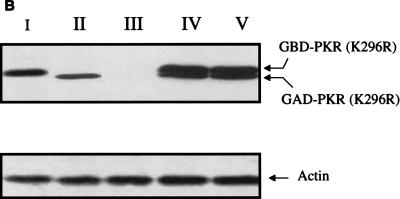

To corroborate these results, we demonstrate that the aa 244-to-296 segment alone also prevents the formation of PKR dimers in another independent assay. In the yeast two-hybrid system, PKR homodimerization can be detected by the induction of β-Gal expression in the appropriate tester strains (16, 66, 67). We thus asked if coexpression of the aa 244-to-296 fragment could inhibit PKR homodimerization in the system. Indeed, when the aa 244-to-296 fragment was overexpressed, self-interaction between PKR was significantly reduced (Fig. 6A). As a control, PKR homodimerization was not affected by the vector alone. Furthermore, the possibility that expression of the 244-to-296 segment reduced the amount of expression of the PKR fusion proteins in the assay is ruled out by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6B). The consistent results obtained with two different methods strongly suggest that aa 244 to 296 are sufficient to inhibit PKR dimerization.

FIG. 6.

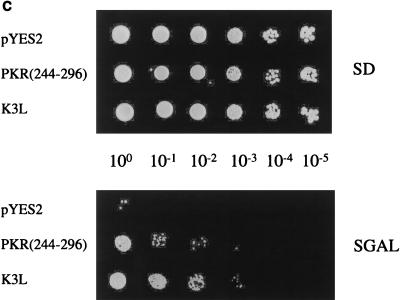

PKR aa 244-to-296 fragment alone prevents full-length PKR dimerization and inhibits kinase activity. Expression of λN-PKR(K296R) with the low-copy-number plasmid pC168 was sufficient to inhibit lacZ expression in strain JH372, resulting in white colony color (see Table 1). Coexpression from a high-copy-number plasmid of a second protein or protein domain [GST-PKR(244–296)] capable of disrupting the association of λN-PKR(K296R) molecules resulted in derepression of lacZ and blue colonies. λ immunity was determined by cross-streak assays as described for Fig. 2B. Bacteria coexpressing an inhibitor of PKR dimer formation are sensitive to λ infection in this case. (A) Coexpression of aa 244 to 296 reduced the amount of PKR dimer formation in the yeast two-hybrid system. Yeast strain SFY526 cotransformed with constructs expressing PKR(K296R) fused to GBD and PKR(K296R) fused to GAD or empty vectors (pGBT10 and pGAD425) was mated with yeast strain Y187 transformed with the expression constructs pYX222-PKR(244–296) or the negative control vector pYX222. Diploids were selected on a minimal selective medium lacking Trp, Leu, and His. β-Gal assays of yeast cell extracts cotransformed with the indicated plasmids were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The results shown represent the mean activity obtained from two experiments. (B) Expression of GAL4-PKR fusion constructs in yeast. An immunoblot analysis of extracts prepared from the indicated yeast transformants is shown. The panel represents the same blot probed sequentially with antibodies to PKR or actin as indicated. Not shown is PKR(244–296), which we were unable to detect by this analysis. The positions of GBD-PKR(K296R) and GAD-PKR(K296R) fusion proteins are indicated by arrows. (C) PKR aa 244-to-296 reverse wild-type kinase-mediated growth suppression in yeast. Yeast strain RY1-1 was transformed with the 2μm yeast expression constructs pYES2-PKR(244–296) or pEMBLYex-K3L (positive control) or the negative control vector pYES2. Transformants were spotted at various dilutions, as indicated in the middle of the panel, on uracil-deficient minimal synthetic medium containing 2% dextrose (SD) or 10% galactose–2% raffinose (SGAL) as the carbon source and scored for growth. Kinase function inhibition was scored by growth on the SGAL plate. Western blot analysis indicated that PKR was efficiently expressed in all yeast strains (not shown).

Despite the results of these interaction studies, it was essential to prove the biological relevance of our observations. We therefore determined whether expression of the 52-aa fragment was sufficient to inhibit PKR activity by using a functional assay in yeast (71). High-level expression of the PKR gene from a galactose-inducible promoter in the yeast strain RY1-1 cultured on galactose medium severely impairs cell growth due to PKR-mediated hyperphosphorylation of yeast eIF-2α (14, 71). We reasoned that expression of the aa 244-to-296 fragment should suppress the toxicity of PKR in yeast by forming inactive heterodimers with wild-type PKR. As shown in Fig. 6C, RY1-1 cells expressing PKR(244–296) (or the vaccinia virus K3L positive control) but not cells expressing the vector control were able to overcome the growth defect effect caused by wild-type PKR induction. Furthermore, like P58IPK as described below, coexpression of PKR(244–296) reduced the extent of eIF-2α phosphorylation in RY1-1 yeast cells expressing PKR (data not shown). These results collectively indicate that dominant interference can occur by the formation of inactive heterodimers between PKR(244–296) and PKR, adding support to the functional significance of dimerization via aa 244 to 296 in kinase function.

P58IPK inhibits PKR activity through the disruption of PKR dimerization.

Earlier studies had demonstrated that PKR aa 244 to 296 comprised the binding site for kinase inhibitors, including P58IPK, the cellular inhibitor recruited by influenza virus to inactivate the protein kinase (25, 26). Given that dimerization may be essential for PKR activity and that the aa 244-to-296 region overlaps with the site of P58IPK interaction, we next explored the possibility that P58IPK adversely affected PKR dimerization. To test this possibility, we examined whether coexpression of a GST-P58IPK fusion could prevent or reduce dimerization of λN-PKR(K296R) in the λ repressor fusion system. As summarized in Table 2, transformants coexpressing GST-P58IPK but not those expressing GST alone turned blue on X-Gal plates and became sensitive to λ superinfection, indicating that P58IPK inhibits PKR dimerization. The specificity of GST-P58IPK for disruption of PKR dimerization was demonstrated by the fact that GST-P58IPK did not diminish dimerization of the Rop protein control in the λ repressor system. Furthermore, coexpression of the GST fusion containing other known PKR inhibitors that bind to other regions of the kinase, including the vaccinia virus K3L protein (25) and the influenza virus NS1 protein (78), had little or no effect on the dimeric state of PKR (Table 2). P58IPK did not abolish dimerization of a PKR fragment containing residues 1 to 167 (data not shown), suggesting that P58IPK acts specifically at residues 244 to 296 and that the two regions can dimerize independently.

TABLE 2.

Summary of λ resistance and β-Gal expression properties of JH372 or AG1688 clones coexpressing λN-PKR(K29R) and various GST fusionsa

| GST fusions | Immunity to λKH54 | Colony color on X-Gal-treated plates | Dimer disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| GST alone | Immune | White | − |

| P58IPK | Sensitive | Blue | + |

| P58IPKΔTPR6 | Immune | White | − |

| NS1 | Immune | White | − |

| K3L | Immune | White | − |

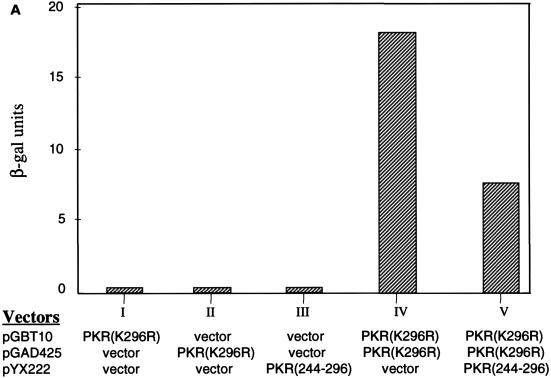

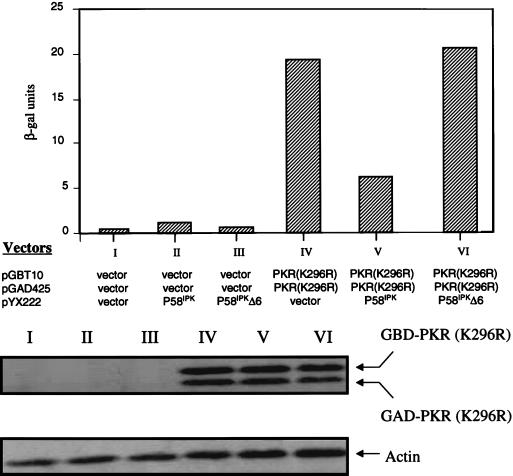

To obtain independent verification, we performed a similar analysis utilizing the yeast two-hybrid system. Coexpression of P58IPK, but not the vector control, markedly reduced the formation of PKR-PKR complex in the two-hybrid assay (Fig. 7). As a control, we tested a nonfunctional form of P58IPK, which lacked TPR domain 6 (P58IPKΔTPR6), in the bacterial and yeast assay. The TPR6 motif of P58IPK was earlier found to be necessary for binding to PKR and inhibiting kinase activity (25, 69). As predicted, we demonstrated that P58IPKΔTPR6 did not abrogate PKR dimerization either in the λ repressor assay (Table 2) or in the yeast assay (Fig. 7). It should be noted that in all cases recombinant proteins were produced to detectable levels (Fig. 7 and 8). Thus the lack of disruption of PKR dimerization and kinase inhibition cannot be explained by the failure to produce the relevant polypeptides. It also should be mentioned that P58IPK is not fused to a heterologous nuclear localization sequence in the coexpression plasmid (pYX222) in this experimental system. It is therefore likely that P58IPK associated with the GAL4-PKR(K296R) fusions in the cytoplasm and the complex was then translocated together to nuclei because of nuclear localization sequence in the GAL4 fusions. This is consistent with the observation that most PKR and P58IPK are found in the cytoplasm (20, 38, 39, 42).

FIG. 7.

P58IPK inhibits PKR dimer formation in the yeast two-hybrid system. (Top) β-Gal activities of triply transformed yeast cells. The appropriate GAL4 two-hybrid tester strains were transformed with the indicated plasmids, and β-Gal assay of the yeast cell extracts was performed as described for Fig. 6B. The results shown here represent the mean activity derived from two experiments. (Bottom) Expression of GAL4-PKR fusions in yeast cells. An immunoblot analysis of extracts prepared from the indicated yeast transformants is shown. The panel represents the same blot probed sequentially with antibodies to PKR or actin as indicated.

FIG. 8.

P58IPK prevents PKR dimerization in the λ repressor fusion system. (A) Coexpression levels of GST fusion proteins. Crude cell extracts from bacteria coexpressing λN-PKR(K296R) and various GST fusions were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 14% gel and visualized by immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal antibody directed against GST. Positions of molecular size standards are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Expression of λN-PKR chimeric protein. The panel represents the same blot probed with a polyclonal antibody to PKR. The arrow indicates the position of λN-PKR(K296R). (See also Table 2.)

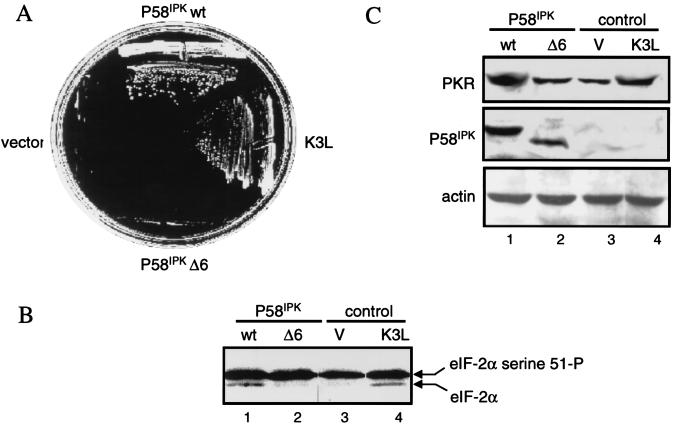

If the disruption of PKR dimers by P58IPK had functional relevance, it was essential to demonstrate that wild-type P58IPK but not the ΔTPR6 mutant retained the ability to inhibit PKR in an in vivo assay. To examine this, we utilized the yeast functional assay described above. RY1-1 cells expressing P58IPK but not P58IPKΔTPR6 or vector control were able to overcome the growth defect effect caused by wild-type PKR (Fig. 9A). The vaccinia virus K3L protein was used in these assays as a positive control (26). These data were further supported by the reduced levels of eIF-2α phosphorylation observed in RY1-1 expressing P58IPK compared to those in yeast cells expressing P58IPKΔTPR6 or vector alone (Fig. 9B). We verified that both wild-type and mutant P58IPK were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 9C). Importantly, RY1-1 cells coexpressing P58IPK but not P58IPKΔTPR6 with PKR exhibited an increase in PKR levels, a finding consistent with a P58IPK-mediated inhibition of PKR autoregulation and stimulation of protein synthesis (7, 71, 82). Thus, these findings strongly support our hypothesis that P58IPK inhibits PKR activity by converting PKR dimers to monomers.

FIG. 9.

A P58IPK mutant incapable of disrupting PKR dimerization does not inhibit PKR function. (A) Yeast growth analysis. Yeast strain RY1-1 was transformed with the 2μm expression plasmid pYES2 (vector control), pYES2-P58IPK, pYES2-P58IPKΔ6, or pEMBLYex4-K3L (positive control) and streaked onto SD (not shown) or SGAL medium. Growth on the SGAL-treated plate indicated inhibition of PKR function in yeast cells. All transformants grew on SD medium (not shown). (B) eIF-2α phosphorylation analysis. Extracts from RY1-1 yeast cells harboring pYES2-P58IPK (lane 1), pYES2-P58IPKΔ6 (lane 2), pYES2 (lane 3), or pEMBLYex4-K3L (control; lane 4) were separated by isoelectric focusing and subjected to immunoblot analysis with an antiserum to yeast eIF-2α. Arrows indicate the positions of yeast eIF-2α phosphorylated on basal sites only (lower band) and yeast eIF-2α phosphorylated on Ser-51, the site of phosphorylation by PKR (upper band). (C) Protein expression. Strains were grown for 5 h in galactose-containing liquid medium, and extracts prepared as described previously (26). Proteins (25 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis. The panels represent the same blot probed sequentially with antibodies to PKR (top), P58IPK (middle), or actin (bottom).

DISCUSSION

Dimerization of PKR and its role in kinase regulation.

PKR was originally inferred to function as a dimer because activation of PKR displayed second-order kinetics (47). This notion was later supported by numerous biochemical analyses demonstrating that PKR exists in solution predominantly as a dimer (11, 49). Furthermore, the dominant negative phenotype of nonfunctional PKR mutants suggests that they form inactive heterodimers with wild-type PKR (6, 46, 61). It is thought that dimerization may mediate activation of PKR through trans-phosphorylation between two PKR monomers brought into close proximity by binding to a single molecule of dsRNA (47). That the wild-type enzyme is able to phosphorylate a catalytically inactive PKR in trans is consistent with this view (83, 84). Moreover, Cosentino et al. (16) demonstrated that PKR dimerizes via the DSRMs, and that dimerization in vitro is dependent on the presence of dsRNA.

Cosentino et al. (16) also demonstrated that the dimerization region of PKR resides within the N-terminal region of 184 residues, which includes the DSRMs. In contrast, Ortega et al. (66) reported that a PKR fragment containing residues 1 to 280 was insufficient to interact with full-length PKR. Indeed, genetic complementation studies in yeast (71) and in vitro binding studies (67) suggest there may be more than one dimerization region on PKR. The data presented in this study help reconcile these conflicting reports. We identified a site within aa 244 to 296 capable of promoting PKR dimerization, which spans the hinge region and catalytic subdomains I and II (60). In a finding that is consistent with the notion that dimerization is essential for PKR activation or function, we show that coexpression of the 52-aa fragment that inhibits dimerization also inhibits kinase function. Our results thus provide a simple explanation for the discrepancy generated from PKR dimerization studies, i.e., PKR can dimerize via direct protein-protein interaction dictated by a motif located within aa 244 to 296, as well as via dsRNA-mediated association between the DSRM sequences. Amino acid residues 244 to 296 of PKR include part of the so-called third basic domain (aa 233 to 273), which does not appear to bind detectable levels of RNA (50). Intriguingly, deleting this segment in full-length PKR abolishes kinase activity in vivo (50, 71). Experiments are in progress to identify the critical residues within the 244-to-296 region that are required for dimerization.

While dimer formation of PKR may not be required for activation (85), such formation may regulate its catalytic function. Dimerization is known to confer unique properties on enzymes; it may regulate the level of enzyme activity (8, 22) or modify enzyme specificity for substrate selection (57). In regard to the latter, PKR has also been shown to phosphorylate other substrates, including the inhibitor IκB of the transcription factor NF-κB (48), the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein (10), and an unknown protein of 90 kDa (70). Even in cases in which no apparent change in activity is linked to dimerization, it may stabilize the protein and/or prevent it from protease degradation or phosphatase action. Furthermore, the possibility that PKR dimerization plays a role in subcellular localization of the kinase cannot be excluded since PKR is found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (20, 38, 39).

Model for PKR dimerization.

Although dsRNA binding has been suggested to mediate the dimerization of PKR DSRMs, evidence for a dsRNA-independent mechanism also has been reported (66, 85). However, it will be difficult to decipher the exact mechanism of dimerization because both the dsRNA-binding and the dimerization properties of the DSRMs are closely embedded in the same regions (68). In any case, both the DSRMs and the aa 244-to-296 region may be required for the formation of a stable PKR dimer complex. Proteins that contain more than one dimerization region have been described, including the transcription factor AP-4 (35), c-Myc (18), the thyroid hormone receptor (63), the vitamin D receptor (64), and the early B-cell factor (29). However, it is beyond the scope of this study to compare the relative affinities of each of the two independent dimerization domains of PKR. Interestingly, we found that P58IPK, which binds PKR at aa 244 to 296, effectively inhibited dimerization of full-length PKR but not a PKR fragment containing aa 1 to 167 (Fig. 7 and 8; data not shown).

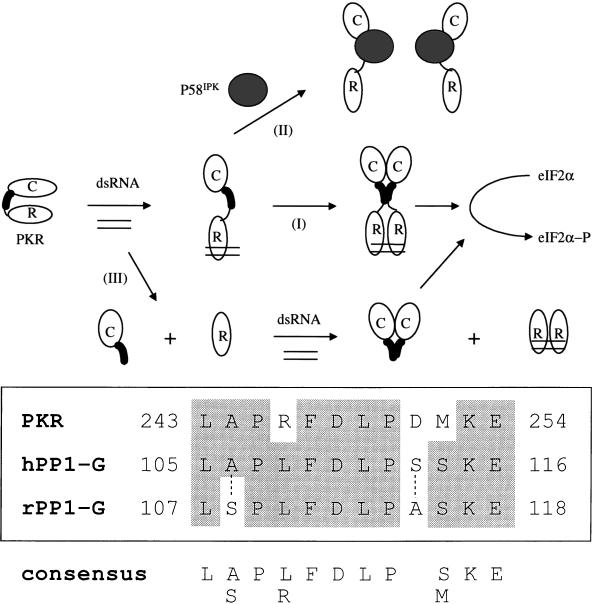

On the basis of our results and other studies, we propose a revised model for the regulation of the PKR dimeric state (Fig. 10A). In this model, the interaction of dsRNA with the DSRMs of PKR serves at least two purposes. First, dsRNA binding may target PKR to ribosomes (87), increasing the effective intracellular PKR concentration so that dimerization and localized functional activity are subsequently favorable. Second, it induces a conformational change that exposes the aa 244-to-296 region to promote protein-protein mediated dimerization of the kinase. P58IPK binding to aa 244 to 296 presumably alters the conformation of PKR such that the kinase, despite the presence of the DSRMs, can no longer form a functional dimer. Alternatively, P58IPK disruption of PKR dimers may simply be due to competition between PKR-PKR and PKR-P58IPK complexes. The observation that both the 244-to-296 segment and P58IPK (as well as a viral PKR inhibitor; see below) bind to PKR at the same site (aa 244 to 296) and inhibit kinase dimerization favors the latter scenario.

FIG. 10.

PKR dimerization. (Top) Proposed model for the modulation of PKR dimerization. The catalytic domain (C) and the regulatory domain (R) containing DSRMs are shown. (I) dsRNA binding to the DSRMs bridges PKR molecules and induces a conformational change that unmasks the dimerization site with residues 244 to 296 (darkened region) to promote intermolecular association of PKR. (II) Binding of P58IPK to the aa 244-to-296 region leads to monomerization of PKR and presumably to inactivation of the kinase. (III) Deletion of the DSRM sequences results in a conformational alteration exposing this dimerization region, and thus the isolated catalytic domain is still capable of forming dimers via aa 244 to 296. (Bottom) Limited homology within the noncatalytic portion of the aa 244-to-296 dimerization region of PKR with human (h) and rabbit (r) glycogen-associated subunits of PP1 (PP1-G). Identical residues are shown by the shaded area; dotted lines indicate the less-conserved residues. The numbers refer to the positions of the amino acids listed. Homology was identified by using the NCBI BLAST program (1).

The importance of residues 244 to 296 in PKR dimerization and P58IPK interaction brings up the question of whether homologous domains in other proteins dimerize or associate with PKR, P58IPK, and/or P58IPK-like proteins. Interestingly, the noncatalytic part of the aa 244-to-296 region contains a putative sequence motif (Fig. 10B) that is also present in the glycogen-associated subunit of the type 1 serine-threonine protein phosphatase (PP1-G) (13). It is tempting to speculate that the identified sequence motif may also play a role in the phosphatase dimerization and/or interaction with PKR. Regarding the latter, the type 1 protein phosphatase has been shown to dephosphorylate PKR, causing a loss in kinase activity (77).

Does P58IPK represent a new class of PKR inhibitors?

Until the present study, regulation of kinase dimerization by a cellular protein inhibitor had not been reported. The PIN protein inhibitor of the neurotransmitter nitric oxide synthase apparently inhibits the enzyme by directly interfering with its dimeric state (37). The results reported here demonstrate that P58IPK can specifically prevent PKR dimerization, providing insights into the mechanism by which P58IPK inhibits PKR activity. In addition, since P58IPK is an established inhibitor of PKR, the finding also lends support to the functional importance of dimerization for kinase activity. Consistent with the view that the aa 244-to-296 region mediates dimerization, PKR inhibitors that act elsewhere on the molecule, including the pseudosubstrate protein K3L (25) and the dsRNA-binding protein NS1 (78), did not perturb the dimeric state of PKR (Table 2). The biological significance of aa 244 to 296 of PKR is further exemplified by the fact that at least one other PKR inhibitor, the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A), also associates with PKR in this region (26). Therefore, P58IPK and NS5A may constitute a new group of PKR effectors, i.e., those that act via disruption of PKR dimerization.

In agreement with the notion that disruption of PKR dimerization by P58IPK is associated with the loss of kinase function, a nonfunctional form of P58IPK lacking the TPR6 domain was unable to inhibit PKR dimer formation. Because the TPR6 domain of P58IPK is required for interacting with PKR (25), a P58IPK protein devoid of this domain (P58IPKΔTPR6) would not be expected to disrupt PKR dimers. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that P58IPK also may act by preventing the activation of PKR by blocking the ATP-binding residues or autophosphorylation sites found within aa 244 to 296 (80). Alternatively, P58IPK may affect the conformation essential for proper ATP binding or sterically hinder the access of substrates to the catalytic site. The former strategy has precedence among the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (45, 65, 72), including the INK4 family members, which all contain the ankyrin repeat motifs (41), a finding that is reminiscent of the tetratricopeptide repeat motifs of P58IPK. Therefore, it is conceivable that there may be more than one mechanism of P58IPK-mediated PKR inhibition, especially given the fact that P58IPK inhibits both the auto- and trans-phosphorylation activity of active PKR (53, 54).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. Gigliani and J. C. Hu for gifts of plasmids and strains for the λ repressor fusion system. We thank M. Domenowske for figure preparation, N. M. Tang, R. M. Krug and E. Beattie for providing GST fusion constructs, K. Elias and M. J. Korth for helpful comments on the manuscript, and G. M. Barber and members of our laboratory for encouragement and stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI 22646, RR 00166, and AI-41629 to M.G.K. M.J.G. is currently a Helen Hay Whitney Fellow. S.-L.T. is supported by a grant from the Gustavus & Louise Pfeiffer Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber G N, Jagus R, Meurs E F, Hovanessian A G, Katze M G. Molecular mechanisms responsible for malignant transformation by regulatory and catalytic domain variants of the interferon-induced enzyme RNA-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17423–17428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber G N, Thompson S, Lee T G, Strom T, Jagus R, Darveau A, Katze M G. The 58-kilodalton inhibitor of the interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase is a tetratricopeptide repeat protein with oncogenic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4278–4282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber G N, Tomita J, Garfinkel M S, Meurs E F, Hovanessian A G, Katze M G. Detection of protein kinase homologues and viral RNA-binding domains utilizing polyclonal antiserum prepared against a baculovirus-expressed ds RNA-activated 68,000-Da protein kinase. Virology. 1992;191:670–679. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90242-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber G N, Tomita J, Hovanessian A G, Meurs E F, Katze M G. Functional expression and characterization of the interferon-induced double-stranded RNA activated P68 protein kinase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10356–10361. doi: 10.1021/bi00106a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber G N, Wambach M, Thompson S, Jagus R, Katze M G. Mutants of the RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) lacking double-stranded RNA binding domain I can act as transdominant inhibitors and induce malignant transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3138–3146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber G N, Wambach M, Wong M L, Dever T E, Hinnebusch A G, Katze M G. Translational regulation by the interferon-induced double-stranded-RNA-activated 68-kDa protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4621–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beutner G, Ruck A, Riede B, Welte W, Brdiczka D. Complexes between kinases, mitochondrial porin and adenylate translocator in rat brain resemble the permeability transition pore. FEBS Lett. 1996;396:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boldyreff B, Mietens U, Issinger O G. Structure of protein kinase CK2: dimerization of the human beta-subunit. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01497-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand S R, Kobayashi R, Mathews M B. The Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is a substrate and inhibitor of the interferon-induced, virally activated protein kinase, PKR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8388–8395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpick B W, Graziano V, Schneider D, Maitra R K, Lee X, Williams B R G. Characterization of the solution complex between the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase and HIV-I TAR RNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9510–9516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castagnoli L, Vetriani C, Cesareni G. Linking an easily detectable phenotype to the folding of a common structural motif. Selection of rare turn mutations that prevent the folding of Rop. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:378–387. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y H, Hansen L, Chen M X, Bjorbaek C, Vestergaard H, Hansen T, Cohen P T, Pedersen O. Sequence of the human glycogen-associated regulatory subunit of type 1 protein phosphatase and analysis of its coding region and mRNA level in muscle from patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1994;43:1234–1241. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.43.10.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong K L, Feng L, Schappert K, Meurs E, Donahue T F, Friesen J D, Hovanessian A G, Williams B R G. Human p68 kinase exhibits growth suppression in yeast and homology to the translational regulator GCN2. EMBO J. 1992;11:1553–1562. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemens M J. Protein kinases that phosphorylate eIF2 and eIF2B, and their role in eukaryotic cell translational control. In: Hershey J, Mathews M, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 139–172. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosentino G P, Venkatesan S, Serluca F C, Green S R, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N. Double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase and TAR RNA-binding protein form homo- and heterodimers in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9445–9449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creasy C L, Ambrose D M, Chernoff J. The Ste20-like protein kinase, Mst1, dimerizes and contains an inhibitory domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21049–21053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis L J, Halazonetis T D. Both the helix-loop-helix and the leucine zipper motifs of c-Myc contribute to its dimerization specificity with Max. Oncogene. 1993;8:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denu J M, Stuckey J A, Saper M A, Dixon J E. Form and function in protein dephosphorylation. Cell. 1996;87:361–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois M F, Hovanessian A G. Modified subcellular localization of interferon-induced p68 kinase during encephalomyocarditis virus infection. Virology. 1990;179:591–598. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90126-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elledge S J, Harper J W. Cdk inhibitors: on the threshold of checkpoints and development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:847–852. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrar M A, Alberola-Ila J, Perlmutter R M. Activation of the Raf-1 kinase cascade by coumermycin-induced dimerization. Nature. 1996;383:178–181. doi: 10.1038/383178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faux M C, Scott J D. Molecular glue: kinase anchoring and scaffold proteins. Cell. 1996;85:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale M, Jr, Tan S-L, Wambach M, Katze M G. Interaction of the interferon-induced PKR protein kinase with inhibitory proteins P58IPK and vaccinia virus K3L is mediated by unique domains: implications for kinase regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4172–4181. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale M, Jr, Korth M J, Tang N M, Tan S-L, Hopkins D A, Dever T E, Polyak S J, Gretch D R, Katze M G. Evidence that hepatitis C virus resistance to interferon is mediated through repression of the PKR protein kinase by the nonstructural 5A protein. Virology. 1997;230:217–227. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale M, Jr, Blakely C M, Hopkins D A, Melville M, Wambach M, Romano P, Katze M G. Regulation of the interferon-induced protein kinase, PKR: modulation of P58IPK inhibitory function by a novel protein, P52rIPK. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:859–871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale, M., Jr., C. M. Blakely, N. M. Tang, and M. G. Katze. Unpublished data.

- 29.Hagman J, Gutch M J, Lin H, Grosschedl R. EBF contains a novel zinc coordination motif and multiple dimerization and transcriptional activation domains. EMBO J. 1995;14:2907–2916. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanks S K, Quinn A M, Hunter T. The protein kinase family: conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains. Science. 1988;241:42–52. doi: 10.1126/science.3291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heldin C H. Dimerization of cell surface receptors in signal transduction. Cell. 1995;80:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofer H W. Conservation, evolution, and specificity in cellular control by protein phosphorylation. Experientia. 1996;52:449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF01919314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J C. Repressor fusions as a tool to study protein-protein interactions. Structure. 1995;3:431–433. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu J C, O’Shea E K, Kim P S, Sauer R T. Sequence requirements for coiled-coils: analysis with lambda repressor-GCN4 leucine zipper fusions. Science. 1990;250:1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.2147779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu Y F, Luscher B, Admon A, Mermod N, Tjian R. Transcription factor AP-4 contains multiple dimerization domains that regulate dimer specificity. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1741–1752. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubbard M J, Cohen P. On target with a new mechanism for the regulation of protein phosphorylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:172–177. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaffrey S R, Snyder S H. PIN: an associated protein inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science. 1996;274:774–777. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeffrey I W, Kadereit S, Meurs E F, Metzger T, Bachmann M, Schwemmle M, Hovanessian A G, Clemens M J. Nuclear localization of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR in human cells and transfected mouse cells. Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:17–27. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiménez-García L F, Green S R, Mathews M B, Spector D L. Organization of the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase DAI and virus-associated VA RNAI in adenovirus-2-infected HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:11–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson L N, Noble M E, Owen D J. Active and inactive protein kinases: structural basis for regulation. Cell. 1996;85:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalus W, Baumgartner R, Renner C, Noegel A, Chan F K, Winoto A, Holak T A. NMR structural characterization of the CDK inhibitor p19INK4d. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katze M G. Regulation of the interferon-induced PKR: can viruses cope? Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katze M G, Wambach M, Wong M L, Garfinkel M, Meurs E, Chong K, Williams B R, Hovanessian A G, Barber G N. Functional expression and RNA binding analysis of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-activated, 68,000-Mr protein kinase in a cell-free system. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5497–5505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kemp B E, Pearson R B. Intra-steric regulation of protein kinases and phosphatases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1094:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90027-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knighton D R, Zheng J H, Ten E L F, Xuong N H, Taylor S S, Sowadski J M. Structure of a peptide inhibitor bound to the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1991;253:414–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1862343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koromilas A E, Roy S, Barber G N, Katze M G, Sonenberg N. Malignant transformation by a mutant of the IFN-inducible dsRNA-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:1685–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1382315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kostura M, Mathews M B. Purification and activation of the double-stranded eIF-2 kinase DAI. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1576–1586. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar A, Haque J, Lacoste J, Hiscott J, Williams B R. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase activates transcription factor NF-kappa B by phosphorylating I kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6288–6292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langland J O, Jacobs B L. Cytosolic double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase is likely a dimer of partially phosphorylated Mr = 66,000 subunits. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10729–10736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee S B, Green S R, Mathews M B, Esteban M. Activation of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-activated human protein kinase in vivo in the absence of its dsRNA binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10551–10555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee T G, Katze M G. Cellular inhibitors of the interferon-induced, dsRNA-activated protein kinase. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 1994;14:48–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78549-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee T G, Tang N, Thompson S, Miller J, Katze M G. The 58,000-dalton cellular inhibitor of the interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) is a member of the tetratricopeptide repeat family of proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2331–2342. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee T G, Tomita J, Hovanessian A G, Katze M G. Purification and partial characterization of a cellular inhibitor of the interferon-induced protein kinase of Mr 68,000 from influenza virus-infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6208–6212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee T G, Tomita J, Hovanessian A G, Katze M G. Characterization and regulation of the 58,000-dalton cellular inhibitor of the interferon-induced, dsRNA-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14238–14243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Longo F, Marchetti M A, Castagnoli L, Battaglia P A, Gigliani F. A novel approach to protein-protein interaction: complex formation between the p53 tumor suppressor and the HIV Tat proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:326–334. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu Y, Wambach M, Katze M G, Krug R M. Binding of the influenza virus NS1 protein to double-stranded RNA inhibits the activation of the protein kinase that phosphorylates the elF-2 translation initiation factor. Virology. 1995;214:222–228. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.9937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacMillan-Crow L A, Lincoln T M. High-affinity binding and localization of the cyclic GMP dependent protein kinase with the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8035–8043. doi: 10.1021/bi00192a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathews M B. Interactions between viruses and the cellular machinery for protein synthesis. In: Hershey J, Mathews M, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 505–548. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merrick W C, Hershey J W B. The pathway and mechanism of eukaryotic protein synthesis. In: Hershey J, Mathews M, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meurs E, Chong K, Galabru J, Thomas N S, Kerr I M, Williams B R, Hovanessian A G. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase induced by interferon. Cell. 1990;62:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90374-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meurs E, Galabru J, Barber G N, Katze M G, Hovanessian A G. Tumor suppressor function of the interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:232–236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murthy A E, Bernards A, Church D, Wasmuth J, Gusella J F. Identification and characterization of two novel tetratricopeptide repeat-containing genes. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:727–735. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagaya T, Jameson J L. Distinct dimerization domains provide antagonist pathways for thyroid hormone receptor action. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24278–24282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nishikawa J, Kitaura M, Imagawa M, Nishihara T. Vitamin D receptor contains multiple dimerization interfaces that are functionally different. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:606–611. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olah G A, Mitchell R D, Sosnick T R, Walsh D A, Trewhella J. Solution structure of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit and its contraction upon binding the protein kinase inhibitor peptide. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3649–3657. doi: 10.1021/bi00065a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ortega L G, McCotter M D, Henry G L, McCormack S J, Thomis D C, Samuel C E. Mechanism of interferon action. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the intermolecular association of the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR from human cells. Virology. 1996;215:31–39. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel R C, Stanton P, McMillan N M, Williams B R, Sen G C. The interferon-inducible double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase self-associates in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8283–8287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patel R C, Stanton P, Sen G C. Specific mutations near the amino terminus of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) differentially affect its double-stranded RNA binding and dimerization properties. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25657–25663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Polyak S J, Tang N, Wambach M, Barber G N, Katze M G. The P58 cellular inhibitor complexes with the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, to regulate its autophosphorylation and activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1702–1707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rice A P, Kostura M, Mathews M B. Identification of a 90-kDa polypeptide which associates with adenovirus VA RNAI and is phosphorylated by the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20632–20637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romano P R, Green S R, Barber G N, Mathews M B, Hinnebusch A G. Structural requirements for double-stranded RNA binding, dimerization, and activation of the human eIF-2 alpha kinase DAI in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:365–378. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Russo A A, Jeffrey P D, Patten A K, Massague J, Pavletich N P. Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor bound to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature. 1996;382:325–331. doi: 10.1038/382325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samuel C E. The eIF-2 alpha protein kinases, regulators of translation in eukaryotes from yeasts to humans. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7603–7606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stock J. Receptor signaling: dimerization and beyond. Curr Biol. 1996;6:825–827. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00605-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szyszka R, Kudlicki W, Kramer G, Hardesty B, Galabru J, Hovanessian A G. A type 1 phosphoprotein phosphatase active with phosphorylated Mr = 68,000 initiation factor 2 kinase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3827–3831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan, S.-L., and M. G. Katze. In vitro and in vivo complex formation between the influenza A virus NS1 protein and the interferon-induced PKR protein kinase. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Tang N M, Ho C Y, Katze M G. The 58-kDa cellular inhibitor of the double stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase requires the tetratricopeptide repeat 6 and DnaJ motifs to stimulate protein synthesis in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28660–28666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taylor D R, Lee S B, Romano P R, Marshak D R, Hinnebusch A G, Esteban M, Mathews M B. Autophosphorylation sites participate in the activation of the double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase PKR. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6295–6302. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor S S, Buechler J A, Yonemoto W. cAMP-dependent protein kinase: framework for a diverse family of regulatory enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:971–1005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomis D C, Samuel C E. Mechanism of interferon action: autoregulation of RNA-dependent P1/eIF-2 alpha protein kinase (PKR) expression in transfected mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10837–10841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomis D C, Samuel C E. Mechanism of interferon action: evidence for intermolecular autophosphorylation and autoactivation of the interferon-induced, RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. J Virol. 1993;67:7695–7700. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7695-7700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomis D C, Samuel C E. Mechanism of interferon action: characterization of the intermolecular autophosphorylation of PKR, the interferon-inducible, RNA-dependent protein kinase. J Virol. 1995;69:5195–5198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5195-5198.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu S, Kaufman R J. Double-stranded (ds) RNA binding and not dimerization correlates with the activation of the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1756–1763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang X F, Settleman J, Kyriakis J M, Takeuchi-Suzuki E, Elledge S J, Marshall M S, Bruder J T, Rapp U R, Avruch J. Normal and oncogenic p21ras proteins bind to the amino-terminal regulatory domain of c-Raf-1. Nature. 1993;364:308–313. doi: 10.1038/364308a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhu S, Romano P R, Wek R C. Ribosome targeting of PKR is mediated by two double-stranded RNA-binding domains and facilitates in vivo phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14434–14441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]