Abstract

Wood formation involves consecutive developmental steps, including cell division of vascular cambium, xylem cell expansion, secondary cell wall (SCW) deposition, and programmed cell death. In this study, we identified PagMYB31 as a coordinator regulating these processes in Populus alba × Populus glandulosa and built a PagMYB31-mediated transcriptional regulatory network. PagMYB31 mutation caused fewer layers of cambial cells, larger fusiform initials, ray initials, vessels, fiber and ray cells, and enhanced xylem cell SCW thickening, showing that PagMYB31 positively regulates cambial cell proliferation and negatively regulates xylem cell expansion and SCW biosynthesis. PagMYB31 repressed xylem cell expansion and SCW thickening through directly inhibiting wall-modifying enzyme genes and the transcription factor genes that activate the whole SCW biosynthetic program, respectively. In cambium, PagMYB31 could promote cambial activity through TRACHEARY ELEMENT DIFFERENTIATION INHIBITORY FACTOR (TDIF)/PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM (PXY) signaling by directly regulating CLAVATA3/ESR-RELATED (CLE) genes, and it could also directly activate WUSCHEL HOMEOBOX RELATED4 (PagWOX4), forming a feedforward regulation. We also observed that PagMYB31 could either promote cell proliferation through the MYB31-MYB72-WOX4 module or inhibit cambial activity through the MYB31-MYB72-VASCULAR CAMBIUM-RELATED MADS2 (VCM2)/PIN-FORMED5 (PIN5) modules, suggesting its role in maintaining the homeostasis of vascular cambium. PagMYB31 could be a potential target to manipulate different developmental stages of wood formation.

Transcription factor MYB31 regulates cambial cell proliferation, xylem cell expansion, and secondary cell wall thickening in poplar.

IN A NUTSHELL.

Background: In trees such as poplar (Populus spp.), wood formation involves cell division of the vascular cambium, xylem cell expansion, secondary cell wall deposition, and programmed cell death. The ability of cambial cells to continue to divide is critical for the stems, branches, and trunks of woody plants to grow in diameter (radial growth). Therefore, understanding how plants regulate cambial cells has implications for producing trees with improved wood growth. The WUSCHEL homeobox transcription factor WOX4 has been identified as a central regulator of cambial cell division, and NAC and MYB transcription factors have been identified as key regulators of secondary cell wall thickening. However, our current knowledge on how cambial cell proliferation and differentiation are coordinately regulated is still limited.

Question: We wanted to identify which gene is involved in regulating cambium cell division and differentiation (xylem development) and understand how it regulates cambial cell proliferation and differentiation in poplar (Populus alba × Populus glandulosa).

Findings: Phenotypic characterization of mutant and overexpressing transgenic plants demonstrated that the transcription factor PagMYB31 positively regulates cambial cell proliferation and negatively regulates xylem cell expansion and secondary cell wall biosynthesis. We find that PagMYB31 plays an important role in maintaining vascular cambium homeostasis in multiple pathways to promote or inhibit WOX4 expression. We also find that PagMYB31 inhibits the expansion of cambial cells and xylem cells and wall thickening of xylem cells, demonstrating its essential role in balancing cambial meristematic fate and differentiation. PagMYB31 can directly regulate key genes controlling cambial cell proliferation and xylem development, placing PagMYB31 at the center of the regulatory network coordinating wood formation.

Next steps: This study shows that PagMYB31 has opposite functions in regulating cambial cell proliferation and xylem development (cell expansion and wall thickening). Further analyses will be carried out to uncover what upstream cues or factors regulate PagMYB31 and to explore strategies for breeding trees with augmented growth.

Introduction

Woody dicotyledon and gymnosperm species have secondary growth, in which the continual activities of vascular cambium produce xylem inward and phloem outward. The xylem is the specialized tissue of vascular plants, providing mechanical support and transporting water and nutrients. Two types of xylem cells (fiber cells and vessels) in angiosperm woody plants have thickened secondary cell walls (SCWs), where cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin are deposited as the major wall components. The interaction and high content of these components in fiber SCWs create a rigid and thick wall, while the hydrophobic surface of the SCWs in vessels, due to lignin structure, enhances their transport function.

During secondary growth, cambial cells need to maintain an undifferentiated stem cell state for self-renewal. Our understanding of the involvement of hormones and key regulators in the regulation of stem cell maintenance in the (pro)cambium is mainly from studies in the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Cytokinin (CK) stimulates cambial activity through D-type cyclin CYCD3 (Dewitte et al. 2007). Auxin concentration is higher in the cambium than in other areas, and the maintenance of auxin homeostasis is modulated by polar auxin transport (Schrader et al. 2003). Overexpression (OE) of PIN-FORMED transporter gene PdePIN5b, transporting auxin to the endoplasmic reticulum to limit the cytoplasmic auxin availability, reduces the indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) level, repressing cambial proliferation (Zheng et al. 2021). Auxin regulates cell division through AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs (ARFs). While ARF5/MONOPTEROS stimulates periclinal cell division during embryogenesis by activating the gene expression of LONELY GUY4 (LOG4) and LOG3, which encode critical enzymes in the CK biosynthetic pathway (De Rybel et al. 2014; Ohashi-Ito et al. 2014), it inhibits vascular cambial activity during secondary growth. In contrast, ARF3 and ARF4 positively regulate cambial activity (Brackmann et al. 2018).

Similar to in the shoot apical meristem, stem cell homeostasis regulation in (pro)cambium is under a noncell-autonomous control by the peptide/receptor system, in which the 12-amino acid Tracheary Element Differentiation Inhibitory Factor (TDIF) peptides, including CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (CLE)-related family members CLE41, CLE42, and CLE44, are produced in phloem and move to the (pro)cambium, where they bind and activate TDIF RECEPTOR (TDR)/PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM (PXY) (Hirakawa et al. 2010). While peptide PttCLE47 is produced in cambium and may promote cambial proliferation in a cell-autonomous way (Kucukoglu et al. 2020). TDIF/PXY signaling regulates vascular stem cell proliferation through WUSCHEL HOMEOBOX RELATED 4 (WOX4) and WOX14, which are key regulators of cambium division with redundant functions. However, mutation of WOX4 and WOX14 does not eliminate cambial activity completely (Etchells et al. 2013), while cambial activity is virtually lost when both WOX4 and Knotted-like from A. thaliana 1 (KNAT1)/BREVIPEDICELLUS were mutated, showing that WOX4 and KNAT1 are major determinants of cambial activity (Zhang et al. 2019). WOX4 is regarded as the central regulator of cambial activity since it integrates multiple pathways, including hormonal and TDIF/PXY signaling. Besides being downstream of TDIF/PXY signaling, WOX4 is required for ARF5-mediated repression of cambium activity and ethylene-mediated promotion of cambium activity (Brackmann et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2020). Phosphorylation of ARF5 by BIN2-LIKE 1 (BIL1) integrates PXY and CK signaling, because PXY can inhibit BIL1 activity, which attenuates the effect of ARF5 on ARR7 and ARR15 expression for increasing cambial activity (Han et al. 2018). Populus tomentosa PtoARF7 directly activates WOX4 and forms a ternary complex with DELLA and Auxin/IAA (AUX/IAA) proteins, providing evidence for the synergic regulation on cambial activity by gibberellin (GA) and auxin (Hu et al. 2022).

The progeny cells generated by cambial proliferation undergo rapid differentiation, including cell expansion, SCW deposition, and programmed cell death (PCD), forming vessels and fiber cells. It is proposed that the cell expansion involves the activities of wall-modifying enzymes, including expansin (EXPA/B), xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH), pectin methyl esterase (PME), pectin/pectate lyase (PL), endo-1,4-β-glucanase (EGase), and endo-1,4-β-mannanase (MAN) (Luo and Li 2022). A 4-layered hierarchical transcriptional regulatory network (hTRN) regulating SCW biosynthesis has been constructed in poplar, in which NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2) transcription factors (TFs), SECONDARY WALL-ASSOCIATED NAC DOMAIN PROTEIN1 (SND1), and VASCULAR-RELATED NAC DOMAIN (VND) in the top layer and MYB TFs in the second layer of the TRN can activate the SCW biosynthesis (Luo and Li 2022; Wei and Wei 2024).

Cambial cell proliferation and differentiation need accurate coordination. TDIF-PXY signaling contributes to the maintenance of procambial cells by suppressing their differentiation into xylem cells, and this suppression is through glycogen synthase kinase 3-mediated inhibition on BRl1-EMS SPPRESSOR 1 (Kondo et al. 2014). Several factors, including WOX4 and WOX14, have dual functions in cambial cell proliferation and xylem cell differentiation (Zhang et al. 2019). Populus ethylene response factor PtERF85 not only activates the genes related to xylem cell expansion but also prevents transcriptional activation of the genes related to SCW formation (Seyfferth et al. 2021). Currently, the knowledge about the coordinated regulation between cambial cell proliferation and xylem cell differentiation is still limited, especially in poplar.

In this study, we characterized PagMYB31 as a central regulator coordinating different developmental stages of wood formation in Populus alba × Populus glandulosa. We found PagMYB31 exhibited opposite effects during wood formation, positively regulating cambium activity and negatively regulating xylem cell expansion and wall thickening. PagMYB31 also coordinately regulated cambial cell proliferation and cell expansion/growth. We built a TRN for this regulator, aiming to understand the molecular mechanism for its coordinated regulation in wood formation.

Results

Improvement of P.alba × P.glandulosa genome assembly

We used P. alba × P. glandulosa in this study. Our previous genome assembly of this species is based on Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing reads and is not at the chromosome level (Huang et al. 2020). To obtain a better genome assembly, we used 25.26 Gb PacBio high-quality (HiFi) long reads and 344.14 M high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) reads (Supplementary Text S1) to reassemble the genome. The final genome assembly that included 2 haploid genomes was 879.94 Mb in length, with a higher contig N50 (10.54 Mb) than the previous version. The contigs were anchored into 38 pseudochromosomes, with scaffold N50 of 24.55 Mb. Benchmarking set of Universal Single-Copy Orthologs assessment showed that the assembly covered 99.26% (1,602/1,614) of the embryophyta single-copy ortholog data sets. The annotation resulted in a total of 85,392 protein-encoding genes, with 44,998 in subgenome A and 40,394 in subgenome B (Supplementary Text S1).

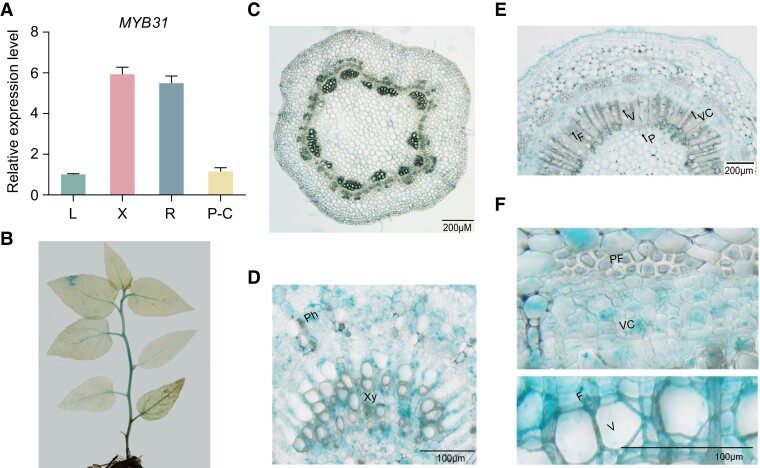

PagMYB31 was expressed in various types of cells in P. alba × P. glandulosa stems

Based on the RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data (Li et al. 2021), PagMYB31 (Potri.007G106100.v3.1), the putative ortholog of AtMYB69 (AT4G33450), was abundantly expressed in the differentiating xylem of P. alba × P. glandulosa. Our reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis confirmed the higher transcript abundance of PagMYB31 in differentiating xylem and young roots and the lower transcript abundance in leaf and phloem–cambium (Fig. 1A). To further examine the detailed expression pattern of PagMYB31, we used 2.5 kb of its promoter to drive the GUS gene in P. alba × P. glandulosa. Young transgenic plants showed GUS staining in the stems and veins of leaves (Fig. 1B). Further GUS staining was performed in the stem cross sections of MYB31p-GUS transgenic plants. In the stem with primary growth, GUS staining was obviously observed in vascular bundle, with signals in both xylem and phloem cells (Fig. 1, C and D). In the stem with secondary growth, GUS signals could be observed in fiber cells, vessels, and ray cells of the differentiating xylem, and there were also detectable GUS signals in cambium and phloem cells, such as phloem fibers (Fig. 1, E and F). Subcellular localization analysis showed that PagMYB31 protein was localized in the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Expression patterns of PagMYB31 in P. alba × P. glandulosa. A) RT-qPCR analysis of PagMYB31 expression in leaf (L), young root (R), differentiating xylem (X), and phloem–cambium (P-C). Values are the means ± Sd of 3 biological replicates. For comparison, the expression level in leaf is set as 1. B to F) GUS staining in tissue-cultured MYB31p-GUS transgenic P. alba × P. glandulosa.B) Young plant, C) cross section of stem with primary growth, D) enlarged image of vascular bundle, E) cross section of stem with secondary growth, and F) enlarged images of phloem, cambial zone, and xylem portions in E). F, fiber cell; P, pith; PF, phloem fiber; Ph, phloem; V, vessel; VC, vascular cambium; Xy, xylem.

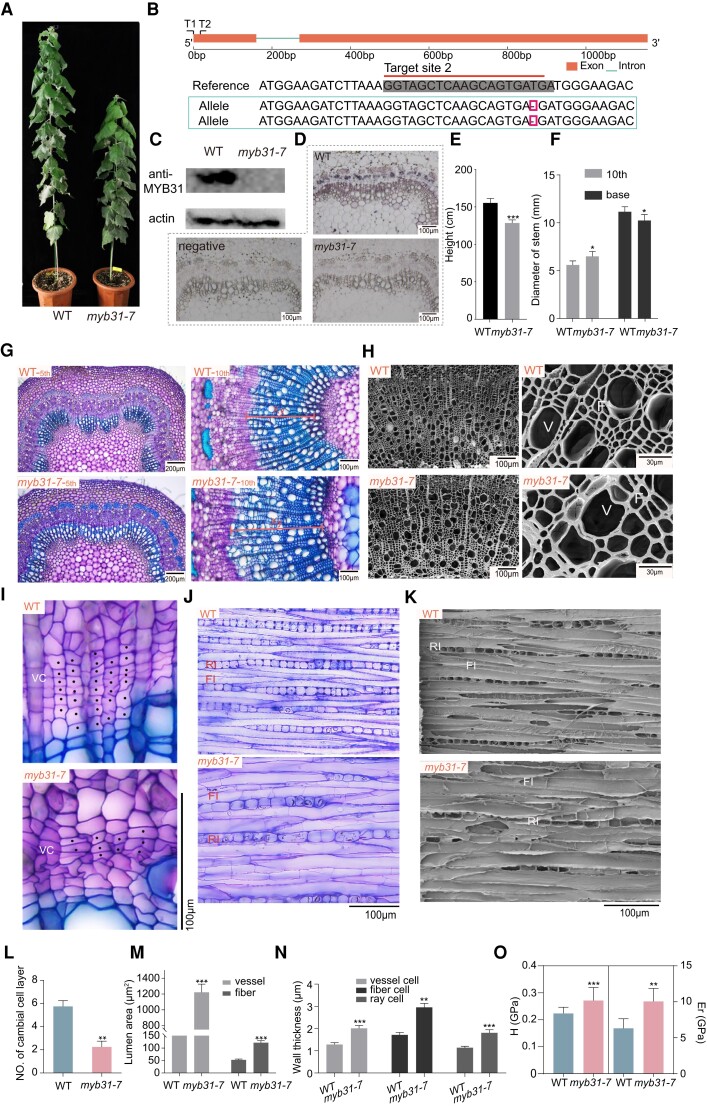

CRISPR-mediated PagMYB31 knockout affected cambial activity, xylem cell expansion and SCW biosynthesis

To study the function of PagMYB31 during wood formation, we first generated loss-of-function mutation of PagMYB31 in P. alba × P. glandulosa using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing (Ma et al. 2015). Two guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed for mutations at 2 sites, and DNA sequencing identified 2 gene-editing mutants (myb31-7 and 11), which both had a homozygous mutation at the 33 base behind ATG within the first exon of PagMYB31 (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. S2A). Western blotting did not detect PagMYB31 proteins in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 2C). Consistently, the cellular immunolocalization detected PagMYB31 proteins in the cells from phloem to xylem of the wild type (WT) but not in the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

PagMYB31 mutation decreases cambial activity and promotes cell expansion and SCW biosynthesis. A) An myb31 mutant and a WT plant. Plants are 5 mo old. B) Sequencing shows a base deletion at the target site 2 in the coding region of PagMYB31. C) Western blotting did not detect PagMYB31 proteins in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant. D) Cellular immunolocalization of PagMYB31 proteins in the stem cross section of myb31-7 and WT plants. Cross section without anti-PagMYB31 antibody was used as a negative control. E) Height of 5-mo-old plants. F) Stem diameter in 7-mo-old plants. G) Cytological observations of stem cross sections of 5th and 10th internodes show enhanced xylem development. H) SEM of stem cross sections of 12th internode. I) Enlarged images in the cambial region of 10th internode. J) Cytological observations of tangential sections in the cambial region. K) SEM observation of tangential sections in the cambial region. L) The number of cambial cell layers at 10th internode. There are fewer layers of cambial cells in the myb31-7 mutant. M) Lumen area of fiber cells and vessels. N) Wall thickness of vessels, fiber cells and ray cells. O) NI analysis. In E), F), and L), error bars represent SD of 6 independent measurements. In M) and N), error bars represent Sd of 50 cells from 3 plants for each line. In O), error bars represent Sd of 20 points from 3 fiber cells in WT and myb31-7 plants. Asterisks show significant differences by Student's t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). F, fiber cell; FI, fusiform initial; RI, ray initial; V, vessel; VC: vascular cambium; Xy, xylem.

PagMYB31 knockout mutant myb31-7 plants that were less than 2 mo old had the same growth rate as WT plants, while 3-mo-old mutant plants started to display a slower growth rate (Fig. 2, A and E). Cytological observation on stem cross sections of the 5th, 10th, and 15th internodes showed differences in anatomical structures between the mutant and WT. In the stem cross sections of the 5th internode, the phloem cap was more obvious in the myb31-7 mutant, showing an enhanced wall thickening in phloem fiber cells (Fig. 2G). In this internode of WT, intrafascicular cambium and interfascicular cambium started to form a continuous vascular cambium; vascular bundles were separated, and the cells between vascular bundles had only slight differentiation (Fig. 2G). While in the 5th internode of the myb31-7 mutant, there was differentiation of fiber cells and vessels in the secondary xylem, causing them to form a continuous xylem circle (Fig. 2G), xylem width in the 5th and 10th internodes of the myb31-7 mutant was larger than that in WT, indicating that xylem development was promoted (Fig. 2G). Consistently, the stem diameter of the 10th internode in the myb31-7 mutant was larger than that in WT (Fig. 2F). However, the stem diameter near the base was smaller in the mutant (Fig. 2F). There were fewer cell layers in secondary xylem at the 15th internode of the myb31-7 mutant compared to in the WT (Supplementary Fig. S3). To check whether the fewer layers of xylem cells are caused by the effect on cambial activities, we compared the cambial zone between the mutant and WT. The vascular cambial zone in the myb31-7 mutant was more difficult to distinguish, because the cambial cells were not in the typical flat shape and the number of cambial cell layers was about half of that in WT (Fig. 2, I and L). We further observed the cambial region on tangential sections under a light microscope and a scanning electron microscope (SEM), and both showed that the fusiform initials and uniseriate ray initials in the myb31-7 mutant were larger than those in WT, and wall-like structures were formed inside some fusiform initials of the mutant, resulting in the loss of the fusiform shape (Fig. 2, J and K).

We further looked at the xylem cells on the stem cross sections under SEM (Fig. 2H). Both vessels and fiber cells were larger in the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 2M), while measurement of segregated xylem cells showed that the length of both vessels and fiber cells in the myb31-7 mutant were shorter than those in WT (27.6% to 31.6%) (Supplementary Fig. S4), showing that PagMYB31 positively regulates xylem cell expansion in the longitudinal direction but negatively regulates xylem cell expansion in the radial direction. The myb31-7 mutant displayed thicker walls in xylem fiber cells than WT (Fig. 2H), and wall thickness of fiber cells in the myb31-7 mutant was about 48.5% larger than that in the WT (Fig. 2N). Vessels and ray cells also had thicker walls in the myb31-7 mutant, about 54.1% and 52.39% thicker than those in WT, respectively (Fig. 2N). Wood compositions were determined in the 7-mo-old myb31-7 mutant and WT, and both cellulose and xylan contents were higher in myb31-7 wood than in WT wood, while lignin content was not significantly different (Table 1). Further, we used nanoindentation (NI) technique to measure the mechanical properties of the fiber cells at the microlevel. Both elastic modulus (Er) and hardness (H) values, 2 important indicators of the micromechanical properties of wood cells, were significantly higher in the myb31-7 mutant than in WT (Fig. 2O), indicating an increased mechanical strength of fiber cells in the mutant.

Table 1.

Wood compositions of PagMYB31 mutant and transgenic plants

| Lines | Glucose | Xylose | Lignin |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 | 54.29 ± 0.80 | 15.62 ± 0.24 | 21.4 ± 0.30 |

| myb31-7 | 56.05 ± 0.12* | 19.10 ± 0.07*** | 22.1 ± 1.49 |

| OE-17 | 48.59 ± 0.43*** | 6.84 ± 0.05*** | 20.3 ± 1.19 |

| WT2 | 58.19 ± 0.74 | 16.82 ± 0.32 | 20.9 ± 1.130 |

| SRDX-19 | 52.42 ± 0.71*** | 12.54 ± 0.36*** | 22.0 ± 1.24 |

Wood compositions were determined using the wood from 7-mo-old myb31-7 mutant, PagMYB31-OE transgenic line OE-17, and PagMYB31:SRDX OE transgenic line SRDX-19. myb31-7, OE-17, and their corresponding WT1 were grown in a field on campus, while SRDX-19 and its corresponding WT2 were grown in a growth room. The content of cellulose and xylan is represented by the detected glucose and xylose contents, respectively. Other hemicelluloses are not shown because of trace amount. Results are presented as mean values ± Sd, and the error bars represent Sd derived from 3 technical replicates. Asterisks show significant differences by ANOVA (myb31-7, OE-17, and WT1) and Student's t-test (SRDX-19 and WT2) (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

The other mutant myb31-11 displayed the same phenotypes as myb31-7, such as fewer layers of cambial cells, promoted xylem development but with fewer layers of xylem cells, larger xylem cells, and thicker walls in vessels and fiber cells (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). The cytological observations demonstrate that PagMYB31 mutation caused a decrease of cambial activity but promoted xylem cell expansions and SCW formation.

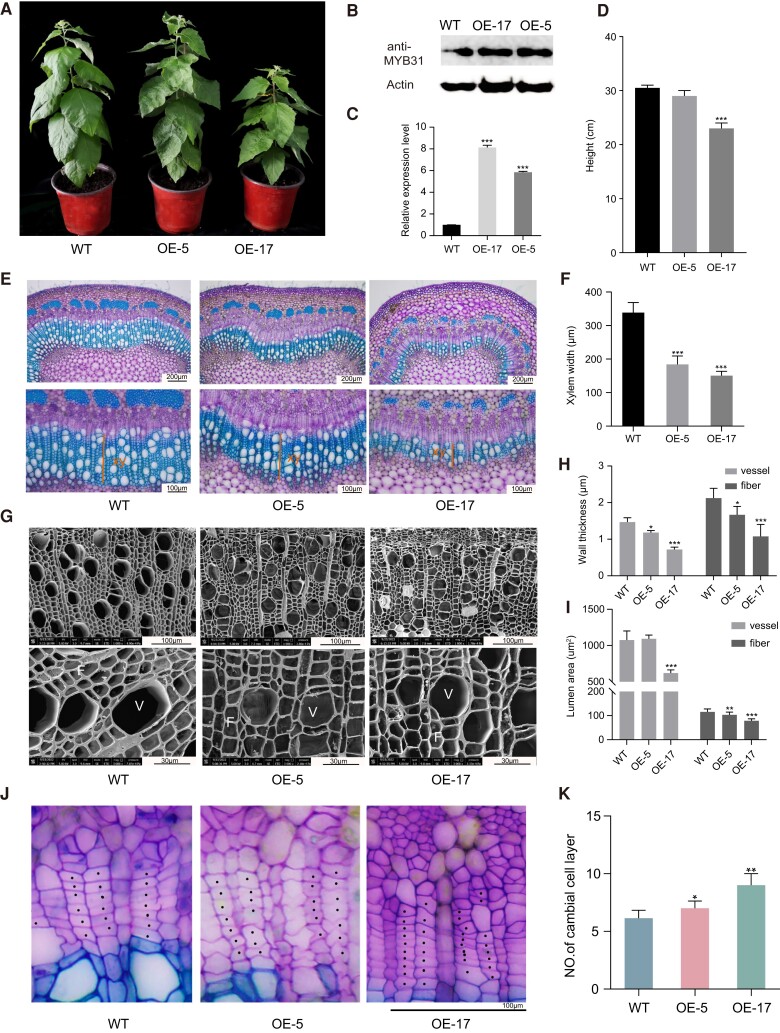

OE of either PagMYB31 or chimeric PagMYB31:SRDX in poplar had opposite effects compared to PagMYB31 mutation

We also generated PagMYB31-OE and PagMYB31:SRDX lines. Fusion of a plant-specific ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING FACTOR (ERF)-associated amphiphilic repression (EAR)-motif repressor domain (SRDX) to the TF C-terminal can turn an activator into a repressor or increase the repression ability of a repressor (Mitsuda et al. 2011). Transgenic plants displayed reduced growth compared to the WT. The growth reduction was more severe in the SRDX transgenic plants than in the OE transgenic plants, with a height reduction of 67.5% in SRDX-19 (Fig. 3, A and D; Supplementary Figs. S5A and S6, A and D). Among the 20 OE transgenic plants, OE-17 had the highest transgene OE (Fig. 3, B and C), and this line displayed a significant height reduction of 24.6% (Fig. 3, A and D).

Figure 3.

OE of Flag:PagMYB31 in P. alba × P. glandulosa inhibited xylem development and SCW thickening. A) WT plants and PagMYB31-OE transgenic lines 5 and 17 (OE-5, and -17). Plants are 1 mo old. B) Western blotting detection of PagMYB31 proteins in differentiating xylem of OE-17, OE-5 and WT. Actin was used as the internal control. C) RT-qPCR analysis of PagMYB31 expression in differentiating xylem of WT, OE-5 and OE-17. D) Height of 1-mo-old plants. E, G) Cytological observation on stem cross sections of 10th internode under light microscopy (E) and of 12th internode under SEM (G) in WT, OE-5 and OE-17. F, H, I) Measurement of xylem width in stem cross sections of 10th internode F), wall thickness of vessel and fibercells H) and lumen area of vessels and fiber cells I) of 12th internode. J) Enlarged images in the cambial region of WT, OE-5, and OE-17. K) Number of cambial cell layers. Error bars represent SD values of 3 biological replicates C), 6 independent measurements D, F, K) and 50 independent measurements H, I), and ANOVA was used for multiple-group comparison, followed by post hoc Dunnett pairwise comparisons to examine statistical significance between transgenic and WT plants (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Cytological observation on the stem cross sections of the 10th internode showed that both OE and SRDX transgenic plants had narrower xylem compared to WT, with a more pronounced difference in SRDX transgenic plants (Fig. 3, E and F; Supplementary Figs. S5, B and C, and S6, E and F). Among the 4 OE lines characterized, OE-17 had the smallest phloem cap with the fewest phloem fiber cells (Fig. 3E; Supplementary Fig. S5B). The phloem cap was even smaller in SRDX transgenic plants, and the SCWs of phloem fibers were not formed yet in the 10th internode of SRDX-11 (Supplementary Fig. S6E). The more severe phenotype in the SRDX transgenic plants may be caused by the higher transgene expression in SRDX transgenic plants than in OE transgenic plants (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S6, B and C), while the stem diameter of the 10th internode in SRDX transgenic plants was about the same as that in WT (Supplementary Fig. S6G).

We measured xylem cell wall thickness on the stem cross sections under SEM. A significant decrease in wall thickness was observed in both fiber cells (58.5% and 17.7%) and vessels (40.6% and 9.1%) of OE-17 and OE-5, respectively (Fig. 3, G and H). We also observed that vessels were smaller in OE-17 compared to in WT, as measured by cell lumen area (Fig. 3I). SEM observations showed that SRDX-11 and SRDX-19 exhibited a similar phenotype to OE transgenic plants, with smaller and thinner-walled vessels and fiber cells (Supplementary Fig. S6, H to J). We also counted the number of cell layers in the cambial zone and observed significant increases of the number in OE-17, OE -19, and OE -5 (Fig. 3, J and K; Supplementary Figs. S5, D and E, and S6, K and L). Wood composition analysis showed that both cellulose and xylan contents were decreased in OE-17 and SRDX-19, which was the opposite of the changes in the myb31-7 mutant. Lignin content was not changed significantly in the wood of either of these 2 transgenic plants (Table 1).

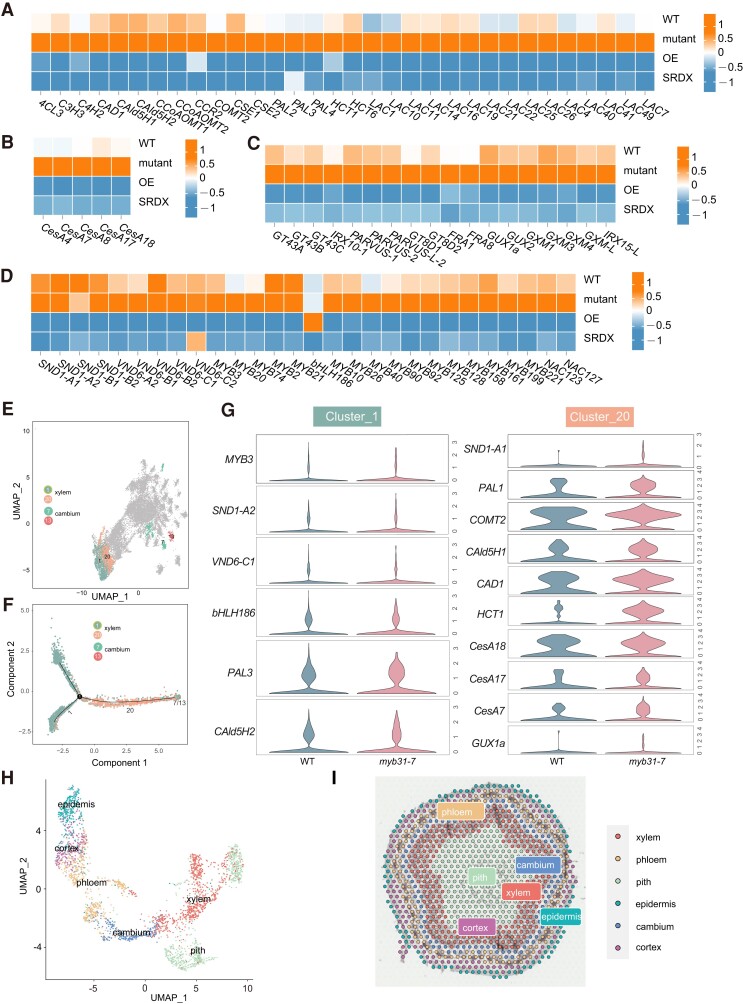

Transcriptome analysis showed that PagMYB31 is a negative regulator of SCW formation

To understand the effects made by PagMYB31 perturbation, we performed high-throughput transcriptome profiling in differentiating xylem, which was scraped from the xylem side below the 7th internode of 2-mo-old plant stems. Gene expression comparison of the RNA-seq data identified a total of 1,892 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the differentiating xylem of both mutant and OE compared to WT (Supplementary Data Set S1). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses showed that both the top-enriched KEGG pathways and GO terms were related to cell wall formation (Supplementary Fig. S7, A and B). We checked the expression of genes that encode essential enzymes for lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose biosynthesis during SCW formation (Fig. 4; Supplementary Data Set S1). Seventeen genes, encoding all the 11 enzymes (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase [PAL], cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, p-coumarate CoA ligase, hydroxycinnamoyltransferase [HCT], p-coumaroyl-CoA 3-hydroxylase, caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase, caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase [COMT], cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, caffeoyl shikimate esterase, coniferaldehyde 5-hydroxylase [CAld5H], and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase [CAD]) of monolignol biosynthesis, were upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the mutant and downregulated in the differentiating xylem of OE transgenic plants (Fig. 4A). Among the upregulated laccase genes in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 4A), 5 (PagLAC4, 21, 14, 40, and 49) were putative orthologs of AtLAC4, 2 (PagLAC7 and 11) were putative orthologs of AtLAC17, and 2 (PagLAC16 and 22) were putative orthologs of AtLAC11, while AtLAC4, AtLAC17, and AtLAC11 have been identified as encoding key enzymes in lignin polymerization (Berthet et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2013), suggesting enhanced polymerization of monolignols in the mutant. Also, the genes encoding essential enzymes for cellulose and xylan biosynthesis exhibited the same changes in expression patterns as lignin biosynthetic enzyme genes, including PagCesA4, 7/17, 8/18 (cellulose biosynthesis), PagGT43A, B, C, IRX10-1 (xylan backbone biosynthesis), PARVUS-1, -2, -L-2, GT8D1, 2, FRA1 and 8 (reducing end biosynthesis), GUX1a and 2 (adding GlcA), GXM1, 3, 4, and IRX15-L (adding 4-O-methyl groups to GlcA residues of xylan) (Fig. 4, B and C). RT-qPCR analysis of selected genes confirmed their upregulation in the mutant and downregulation in the OE/SRDX transgenic plants (Supplementary Fig. S7C). The gene expression analysis showed that biosynthesis of cellulose, hemicellulose (xylan), and lignin during SCW formation was enhanced in the mutant and repressed in the OE and SRDX transgenic plants.

Figure 4.

Transcriptome analysis of differentiating xylem in the myb31-7 mutant, Flag:MYB31, and MYB31:SRDX transgenic P. alba × P. glandulosa. Heat maps showing gene expression profiles of lignin biosynthetic pathway genes A), cellulose synthase (CesA) genes B), xylan biosynthesis enzyme genes C), and TF (MYB and NAC) genes D) in the differentiating xylem of WT, myb31-7 mutant, PagMYB31-OE and PagMYB31:SRDX OE (SRDX) transgenic plants. Orange and blue colors represent higher and lower gene expression levels. E) UMAP representation of clusters related to cambium and xylem by snRNA-seq. F) Pseudotime trajectory of cambium differentiation toward xylem. G) Violin plot visualization to compare the expression level in xylem Clusters 1 and 20 between WT and myb31-7 plants. The height of the violin represents the gene expression level, and the width of the violin represents the proportion of cells expressing in the cluster. H) UMAP visualization illustrates the cell clusters identified in spatial transcriptomics, with each color signifying a unique cell cluster. I) The cluster clusters are mapped over the images of hematoxylin–eosin staining section from 9th internode. 4CL, p-coumarate CoA ligase; C3H, p-coumaroyl-CoA 3-hydroxylase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; CAD, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase; CAld5H, coniferaldehyde 5-hydroxylase; CCoAOMT, caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase; CCR, cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; COMT, caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferaese; CSE, caffeoyl shikimate esterase; HCT, hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; LAC, laccase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase.

We looked at the expression of genes encoding TFs that have been identified as involved in wood formation (Luo and Li 2022), in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant and OE transgenic plants (Fig. 4D). Among the NAC genes at the top layer of the SCW biosynthesis TRN, 4 PagSND genes (SND1-A1/A2 and B1/B2) and 5 PagVND genes (VND6-A2, B1/B2, and C1/C2) were downregulated in PagMYB31-OE transgenic plants. However, among these 9 genes, only PagVND6-A2, B1, and C1 were significantly upregulated in the myb31-7 mutant. For the genes in the second layer, PagMYB21/2 and 20/3, orthologs of AtMYB46 and 83, their expression levels were all downregulated in the OE transgenic plants, while only PagMYB3 and 20 were upregulated in the myb31-7 mutant. PagMYB74, which was identified as an additional target of poplar SND1s (Chen et al. 2019), was upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the mutant and downregulated significantly in the OE transgenic plants. Many other MYB genes had the same expression change patterns, among which PagMYB90, 92, 10, 221, 125, 161, and 199 have been identified as functioning in wood formation in poplar (Luo and Li 2022).

We also conducted single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) in the myb31-7 mutant and WT, respectively, using nuclei that were isolated from the mixed differentiating xylem and phloem. Unsupervised clustering analysis of the transcriptome in WT and the myb31-7 mutant yielded 21 clusters, which were identified using available marker genes (Supplementary Fig. S8, A and B; Supplementary Data Set S2). Clusters 1, 2, 19, and 20 were attributed to the cells that were undergoing SCW thickening (Supplementary Fig. S8). Pseudotime trajectory analysis showed that Cluster 1 was in a later stage of the SCW thickening process than Cluster 20 (Fig. 4, E and F). We observed that many cell wall metabolite genes, including PagCesA7, CesA17, CesA18, PAL1, CAD1, COMT2, HCT1, CAld5H1, and GUX1a, were upregulated in Cluster 20 of the myb31-7 mutant, and only PagPAL3 and PagCAld5H2 were upregulated in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 4G). While more TF genes were upregulated in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant than in Cluster 20 (Fig. 4G). For examples, 3 genes, PagSND1-A2, VND6-C1, and MYB3, were upregulated in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant, while only PagSND1-A1 was upregulated in Cluster 20 of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 4G). Further, spatial transcriptome analysis was conducted on the stem cross sections of the 9th internode (Fig. 4, H and I; Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10). In this analysis, 40,395 genes were detected from 999 spots in WT and 45,406 genes were detected from 1,667 spots in the myb31-7 mutant (Supplementary Data Set S2). The spots were divided into 6 clusters following linear regression and UMAP visualization of spatial transcriptome (Fig. 4, H and I). Most TF and cell wall metabolite genes displayed the same expression change as in RNA-seq. For example, 4 genes encoding TFs that regulate SCW biosynthesis (PagMYB3, 20, 74, and VND6-C1) and PagCesA4, 7, IRX10-1, and 15-L were all upregulated in the mutant (Supplementary Fig. S9). The upregulation of these TF genes in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant and their downregulation in the OE transgenic plants indicate that the TRN regulating wood formation is enhanced in the differentiating xylem of the mutant and shut down in the OE transgenic plants.

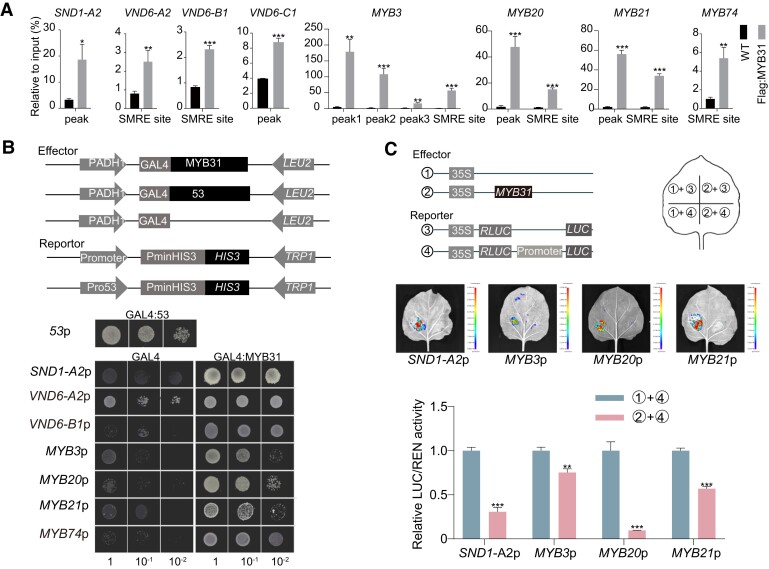

PagMYB31 regulated SCW formation by directly inhibiting the key TF genes regulating SCW biosynthesis

To investigate how perturbation of PagMYB31 affects SCW biosynthesis, we identified the direct targets of PagMYB31 through a combination of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq and RNA-seq (from mutant and OE transgenic plants). ChIP was conducted in Flag:PagMYB31-OE transgenic lines OE-5 and OE-17 using anti-Flag antibodies, followed by sequencing of the immunoprecipitated DNA fragments. Through the integration of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data, we identified a total of 252 PagMYB31 direct targets, which were upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant and downregulated in OE transgenic plants. Among these, 52 genes, corresponding to 74 ChIP peaks, were associated with secondary growth based on the GO annotations (Supplementary Data Set S3). ChIP-qPCR was performed for the interactions of PagMYB31 with the promoters of these 46 genes, and it verified that PagMYB31 could bind the promoters of 31 genes (Supplementary Fig. S11, Fig. 5A). Among these 31 genes, XYLEM CYSTEINE PROTEASE2 (PagXCP2) encoded a cysteine protease that is involved in the PCD process during xylem development.

Figure 5.

PagMYB31 regulates SCW biosynthesis through directly inhibiting the TF genes regulating SCW formation. A) Detection of the interactions between PagMYB31 and the promoters of 8 TF genes of SCW biosynthesis by ChIP-qPCR. ChIP was conducted in WT and Flag:PagMYB31-OE transgenic line OE-17. The qPCR primers are designed within the region of ChIP peaks, and SMRE sites were identified in the promoters of PagVND6-A2, B1, C1, MYB3/20, 21, and 74. B) Y1H assays of PagMYB31 with its targets. Cotransformants (GAL4:MYB31 and Promoter:HIS3) were diluted (1, 10−1, and 10−2) and grown on SD/-Leu-Trp-His medium, supplemented with a certain concentration of 3-AT. GLA4:53 + 53p:HIS3 was used as a positive control, and GAL4 + Promoter:HIS3 was the negative control. C) Effector–reporter-based activation/repression assays show that PagMYB31 inhibits the promoter activity of PagSND1-A2, MYB21 and 20/3. The activity of Rluc was used as internal interference. In A) and C), error bars represent Sd values of 3 biological replicates, and asterisks indicate significance between transgenic and WT plants by Student's t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

To confirm the ChIP results, we selected 11 genes (PagMYB21, 20/3, SND1-A2, MYB158, NAC127, CAld5H2, AUX1, XCP2, TBL33, and TBL38) to perform yeast 1 hybridization (Y1H) and effector–reporter assays. In Y1H assays (Supplementary Fig. S12; Fig. 5B), the bait yeast strain harboring each promoter of these 11 genes could not grow on the medium supplemented with 3-amino-1,2,4-tritriazole (3-AT). When PagMYB31 was transformed into bait strain, the yeast could grow on the medium supplemented with 3-AT, indicating that PagMYB31 could activate these promoters. In effector–reporter assays (Supplementary Fig. S13; Fig. 5C), the effector construct (35S:PagMYB31) was cotransformed with each of these 11 reporter constructs in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and luciferase (LUC) activity was determined to examine the activation/repression effects of PagMYB31 on each promoter. The assays showed that LUC activity in each of the cotransformations was decreased compared to that in the control (transformed reporter construct only), showing that transient OE of PagMYB31 inhibited the expression of these 11 genes. Both Y1H and effector–reporter assays supported the ChIP results and the repressor activity of PagMYB31.

A total of 8 genes encoding TFs that regulate SCW biosynthesis were identified as candidate direct targets of PagMYB31 by ChIP-seq/qPCR (Supplementary Data Set S3; Fig. 5A), and they included one PagSND1 member (SND1-A2), 3 PagVND6 members (VND6-A2, B1, and C1), and 4 PagMYB members (MYB3/20, 21, and 74). Y1H assays also detected the interaction of PagMYB31 with the promoters of 7 of the 8 genes (Fig. 5B). We selected PagSND1-A2, MYB3/20, and 21 for effector–reporter assays, which showed that PagMYB31 could inhibit their promoter activity significantly (Fig. 5C). Among these 8 genes, except PagSND1-A2 and MYB21, the other 6 genes were upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 4D), while PagSND1-A2 was upregulated in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant by the snRNA-seq (Fig. 4G). Although ChIP/qPCR showed that PagMYB31 could also bind the promoter of PagVND6-B2 (Supplementary Fig. S11), the expression of PagVND6-B2 was not changed significantly in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant. These results demonstrate that PagMYB31 directly and negatively regulates PagSND1-A2, MYB3/20, 74, VND6-A2, B1, and C1 and the enhanced SCW biosynthesis in the myb31-7 mutant may be caused by upregulation of these 7 TF genes.

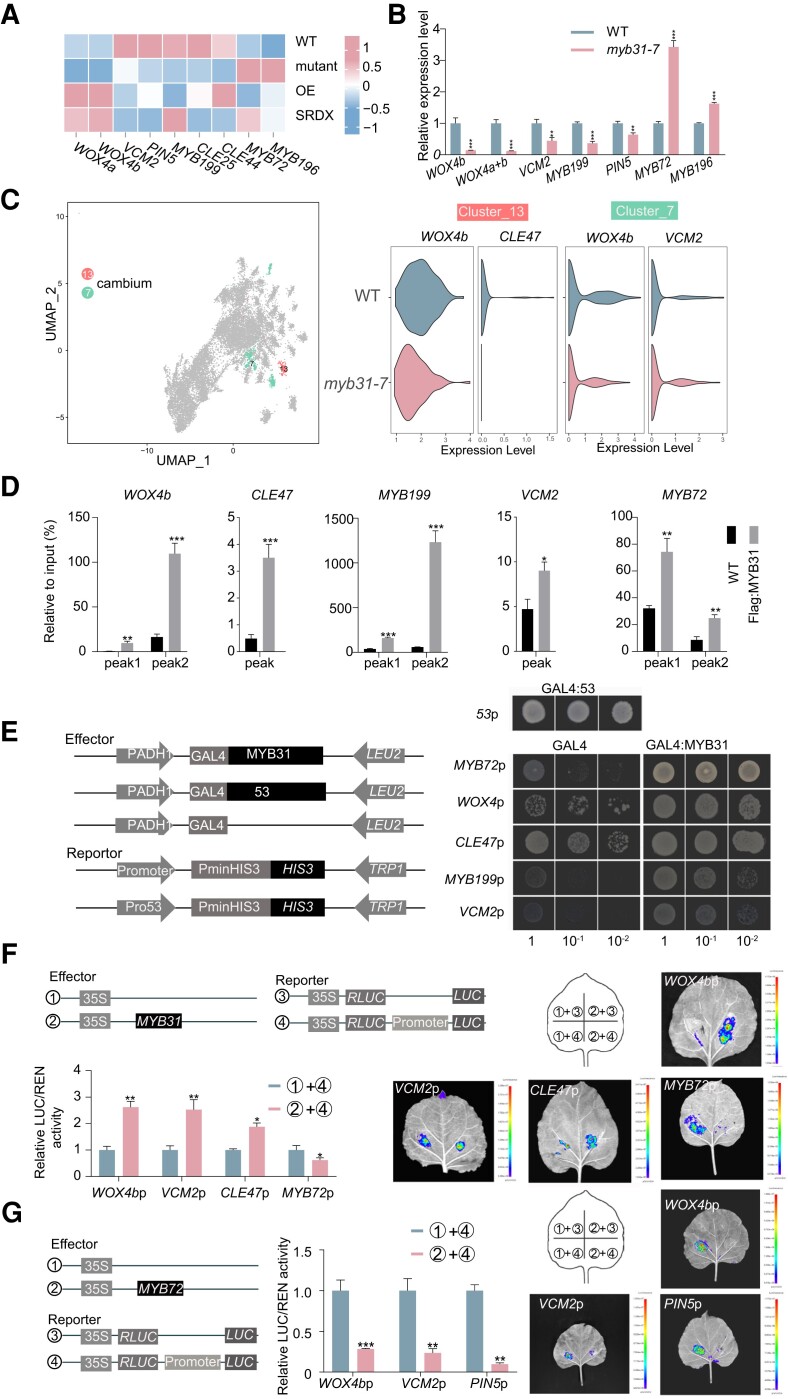

PagMYB31 positively regulates cambium activity

The myb31 mutants displayed fewer layers of cambial cells than WT, while OE transgenic plants had increased layers of cambial cells (Figs. 2, I and L, and 3, J and K; Supplementary Figs. S2, B and C, and S5, D and E), showing that PagMYB31 positively regulates cambial activity. To examine gene expression in cambial cells, the tissues were scraped from the bark side and used for RNA-seq. Although the tissue from the bark side was a mixture of phloem and cambium, the majority of cambial cells were attached to the phloem side but not the xylem side when the bark was peeled; thus, we could analyze the expression of cambium-specific genes based on the RNA-seq data (Supplementary Data Set S4).

We investigated genes encoding proteins that are known to function in the cambium of poplar, including PagWOX4, VCM1/2, and MYB199 (Moyle et al. 2002; Tang et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2021). PttWOX4 is specifically expressed in the cambium region in poplar (Kucukoglu et al. 2017). In the myb31-7 mutant, transcript abundance of PagWOX4a/b was significantly lower compared to that in WT, with PagWOX4b transcript abundance being particularly low (1.48-fold lower than in WT, Padj < 0.05) (Supplementary Data Set S4; Fig. 6A). Two vascular cambium-related MADS-box proteins, VCM1 and VCM2, regulate cambium activity through directly activating PIN5 (Zheng et al. 2021). Both PagVCM2 and PagPIN5 were downregulated significantly in the phloem–cambium of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 6A). PaMYB199 is induced by auxin and encodes a negative regulator of cambial cell proliferation (Tang et al. 2020). PagMYB199 was downregulated in the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 6A). RT-qPCR confirmed the downregulations of PagWOX4, VCM2, PIN5, and MYB199 in the mutant (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

PagMYB31 directly regulates the expression of the genes involved in cambial proliferation. A) Heat map shows the expression level changes of the genes involved in cambial cell proliferation in the phloem–cambium of WT, myb31-7 mutant, PagMYB31-OE and PagMYB31:SRDX OE (SRDX) transgenic plants. B) RT-qPCR confirmation of downregulation of PagWOX4, VMC2, MYB199, and PIN5 and upregulation of PagMYB72 and 196 in the phloem–cambium of the myb31-7 mutant. Specific primers are designed to quantify the transcript abundance of PagWOX4a + 4b and PagWOX4b. C) UMAP visualization (left) of Clusters 7 and 13, which represent cambium cells, and violin plot visualization (right) of the downregulation of PagWOX4, CLE47, and VCM2 in cambium clusters of the myb31-7 mutant by snRNA-seq. The height of the violin represents the gene expression level, and the width of the violin represents the proportion of cells expressing in the cluster. D) ChIP-qPCR shows the binding of PagMYB31 to the promoters of PagWOX4, CLE47, MYB199, VCM2, and MYB72. E) Y1H assays of PagMYB31 and the promoters of PagWOX4, CLE47, MYB199, VCM2, and MYB72. Cotransformants (GAL4:MYB31 and Promoter:HIS3) were diluted (1, 10−1, and 10−2) and grown on SD/-Leu-Trp-His medium, supplemented with 3-AT. GLA4:53 + 53p:HIS3 was used a positive control, and GAL4 + Promoter:HIS3 was the negative control. F) Effector–reporter assays show that PagMYB31 activates the promoter activity of PagWOX4, VCM2, and CLE47 but inhibits the promoter activity of PagMYB72. G) Effector–reporter transactivation/repression assays show that PagMYB72 represses the promoter activity of PagWOX4b, VCM2 and PIN5. In B), D), F), and G), error bars represent Sd values of 3 biological replicates, and asterisks indicate significance between transgenic and WT plants by Student's t-test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

In the snRNA-seq analysis, Clusters 7 and 13 were characterized as cambium cells based on the upregulation of PagWOX4 in these 2 clusters (Supplementary Fig. S8). We observed that PagWOX4b and CLE47 were downregulated in Cluster 13 of the myb31-7 mutant and PagWOX4b and VCM2 were downregulated in Cluster 7 of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 6C), which was consistent with the RNA-seq results. The downregulation of PagWOX4 in the cambial region was also detected in the spatial transcriptome analysis (Supplementary Fig. S10A). The results showed that PagMYB31 mutation affected the expression of the genes associated with cambial proliferation.

Integration of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq in phloem–cambium identified a few direct targets of PagMYB31, including PagWOX4, VCM2, MYB199, CLE47, and MYB72, which was confirmed by ChIP-qPCR (Supplementary Data Set S3; Fig. 6D). Y1H assays also supported that PagMYB31 bound the promoters of these 5 genes (Fig. 6E). Further effector–reporter assays showed that PagMYB31 could activate the promoter activity of PagWOX4b, CLE47, and VCM2 (Fig. 6F), demonstrating that PagMYB31 directly and positively regulates these 3 genes. Although we did not detect the direct regulation of CLE44 genes by PagMYB31, we observed that PagCLE44D was upregulated in the phloem–cambium, suggesting a role for CLE peptide in PagMYB31-mediated cambial activity regulation.

Among the 95 vascular cambium-specific (VCS) TF genes (Dai et al. 2023), PagMYB72 (VCS60) and PagMYB196 (VCS74) were the only 2 genes that were upregulated in the phloem–cambium of myb31 in RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 6, A and B), and spatial transcriptome analysis also showed the upregulation of PagMYB72 in the cambial region of the myb31-7 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S10A). Among these 2 genes, PagMYB72 was identified as a PagMYB31 target by ChIP-seq (Supplementary Data Set S3). ChIP-qPCR confirmed that PagMYB31 could bind the promoter of PagMYB72 but not PagMYB196 (Fig. 6D). We performed effector–reporter assays and observed that PagMYB72 significantly inhibited the promoter activity of PagWOX4b, VCM2, and MYB199 (Fig. 6G). Because in the effector–reporter assay, PagMYB31 could suppress the expression of PagMYB72 (Fig. 6F), we assume that PagMYB31 might regulate the expression of PagWOX4, VCM2, and MYB199 through PagMYB72.

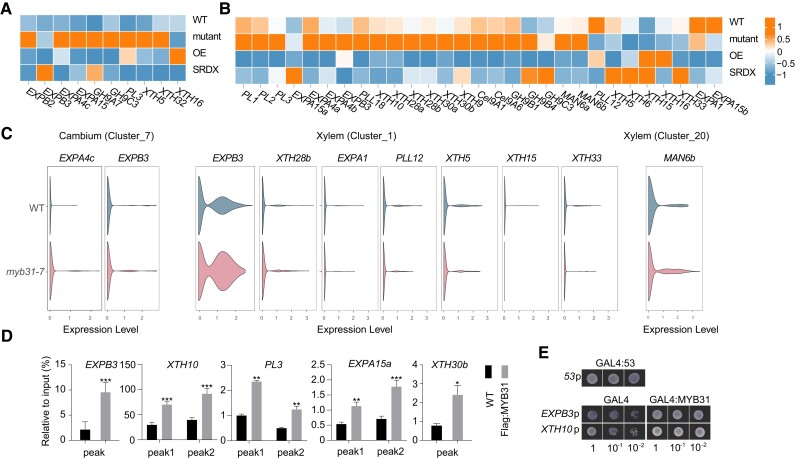

PagMYB31 regulates cell expansion and growth

Cytological observations showed larger fiber cells and vessels in the differentiating xylem of myb31 mutants compared to WT, and fusiform initials and ray initials in the cambium of the myb31-7 mutant were obviously larger also. We looked at the expression of the DEGs encoding wall-modifying enzymes that are associated with wall expansion, including EXPA/B, xyloglucan transglucosylase/hydrolase (XET/XEH), PME, PL, EGase, and MAN (Luo and Li 2022). RNA-seq analysis showed a large number of wall-modifying enzyme genes were differentially expressed in the mutant, including 10 genes in the phloem–cambium and 29 in the differentiating xylem (Supplementary Data Sets S1 and S4). Among the 10 DEGs in the phloem–cambium, PagXTH16 was downregulated, and the other 9 genes were all upregulated (Fig. 7A), and consistently spatial transcriptome analysis showed 3 of these 9 genes (PagEXPB3, PL3, and EXPA4c) were upregulated in the cambial region of the myb31-7 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S10B). Among the 29 DEGs in the differentiating xylem, 21 genes were upregulated in RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 7B), and spatial transcriptome analysis showed 8 of these 21 genes were upregulated in the xylem region of the myb31-7 mutant compared to in that of WT (Supplementary Fig. S10C).

Figure 7.

PagMYB31 regulates cambium and xylem cell expansion. A) Heat map shows the expression of wall-modifying enzyme genes, including expansin (EXPA) genes, XTH genes, and PL genes in the phloem–cambium A) and differentiating xylem B). C) Violin plot visualization to compare the expression level of wall-modifying enzyme genes in cambium and xylem clusters between WT and myb31-7 plants by snRNA-Seq. The height of the violin represents the gene expression level, and the width of the violin represents the proportion of cells expressing in the cluster. D) ChIP-qPCR detection of the binding of PagMYB31 to the promoters of 5 wall-modifying enzyme genes. Error bars represent Sd values of 3 biological replicates, and asterisks indicate significance between transgenic and WT plants by Student's t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). E) Y1H assays of PagMYB31 with the promoters of PagEXPB3 and PagXTH10. Cotransformants (GAL4:MYB31 and Promoter:HIS3) were diluted (1, 10−1, and 10−2) and grown SD/-Leu-Trp-His, supplemented with 3-AT. GLA4:53 + 53p:HIS3 was used as the positive control, and GAL4 + Promoter:HIS3 was the negative control.

Using the snRNA-seq data, we compared the gene expression of these wall-modifying enzyme genes in Clusters 13 and 7, which represented the cambial cells, and in Clusters 1 and 20, which represented the xylem cells. We observed that only PagEXPB3 and PagEXPA4c were upregulated significantly in Cluster 7 of the myb31-7 mutant. Two genes PagEXPB3 and PagXTH28b were upregulated significantly in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant, and PagMAN6b was upregulated significantly in Cluster 20 (Fig. 7C). Among the 8 downregulated genes in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant in RNA-seq analysis, 5 genes (PagEXPA1, PLL12, XTH5, 15, and 33) were downregulated in cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant in snRNA-seq analysis (Fig. 7C).

Among the direct targets of PagMYB31 by ChIP-seq, a total of 12 wall-modifying enzyme-encoding genes were differentially expressed in the myb31-7 mutant by RNA-seq analysis (Supplementary Data Sets S1 and S4). We selected 5 genes PagEXPB3, XTH10, EXPA15a, XTH30b, and PL3 for ChIP-qPCR experiments and confirmed enriched DNA fragments immunoprecipitated by anti-PagMYB31 antibodies in their promoters (Fig. 7D). Y1H assays on 2 selected genes, PagEXPB3 and PagXTH10, supported the ChIP results (Fig. 7E). Among the 12 PagMYB31 targets, 2 genes, including PagEXPB3 and PL3, were upregulated in both phloem–cambium and differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant. The results show that more wall-modifying enzyme genes are involved in the cell expansion of xylem cells. The upregulation of wall-modifying enzyme genes caused by PagMYB31 mutation indicates that these enzymes play a role in PagMYB31-mediated cell expansion of cambial cells and xylem cells. PagEXPB3 and PL3 may be involved in cell expansion in both the cambial region and differentiating xylem.

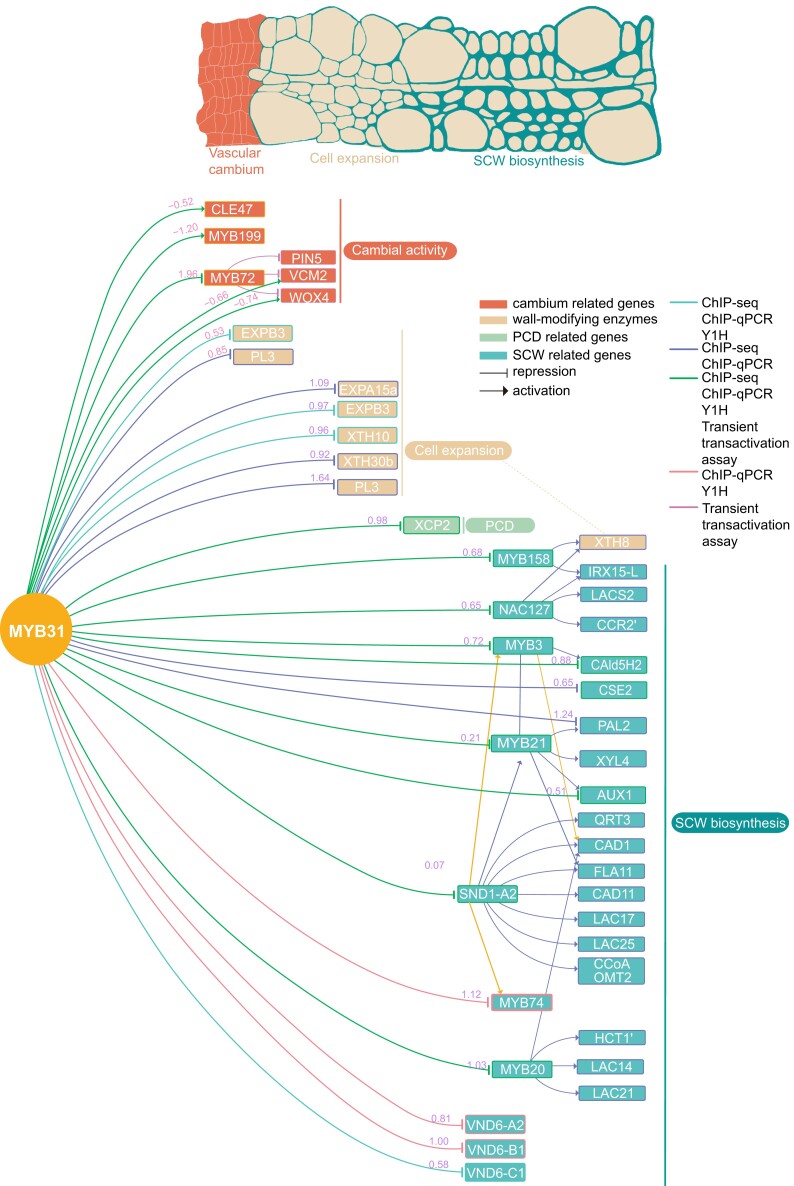

PagMYB31-mediated TRN

To build the TRN mediated by PagMYB31, we selected 6 TF genes that were identified as PagMYB31 targets and performed ChIP-seq. These 6 TF genes were fused with 3 × Flag tags and transiently transformed into poplar plants via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. ChIP-seq analysis showed that these 6 TFs could bind to the promoters of at least 1 of 19 cell wall metabolite genes, which was verified by ChIP-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. S14). For example, PagSND1-A2 directly regulated 10 genes, including 3 for monolignol biosynthesis, 2 for lignin polymerization, 2 for CW modifications, and 3 MYB genes. PagMYB20 directly regulated 4 genes, PagCAD1, HCT1́, LAC14, and LAC21. Combining the RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, Y1H, and effector–reporter assay, we built a PagMYB31-mediated TRN, which consisted of 58 TF–DNA interactions (Fig. 8; Supplementary Data Set S5). The TRN showed that PagMYB31 directly regulates cell expansion, PCD and SCW biosynthesis, while in cambium, PagMYB31 directly and indirectly regulates PagWOX4. PagMYB31 not only indirectly repressed PagCAld5H2 through PagMYB3 but also had a feedforward effect on PagCAld5H2. Among the 27 wall-modifying enzyme genes that were upregulated in the differentiating xylem and cambium of the myb31-7 mutant, PagMYB31 directly regulated only 5 of them. Among the others, PagXTH8 was directly regulated by PagMYB31's target PagNAC127.

Figure 8.

PagMYB31-mediated TRN regulating different developmental steps of wood formation, including cambial cell proliferation, xylem cell expansion, and SCW biosynthesis. In cambium, PagMYB31 directly regulates PagWOX4, VCM2, MYB199, and CLE47. PagMYB72 is the target of PagMYB31, and PagMYB72 directly inhibits PagWOX4, PagVCM2, and PagPIN5. PagMYB31 also inhibits the expression of wall-modifying enzyme genes (PagEXPB3 and PL3) to repress cambial activity. During xylem development, PagMYB31 directly inhibits the wall-modifying enzyme genes (PagEXPB3, EXP15a, XTH10, XTH30b, and PL3) to repress cell expansion. PagMYB31 can bind to the promoters of TF genes regulating SCW biosynthesis (4 SND1s, 6 VNDs, MYB3/20, 2/21, and 74), but only PagSND1-A2, MYB3/20, 74, PagVND6-A2, B1, and C1 were upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the myb31-7 mutant. The numbers in pink and purple colors on the lines represent the log2 fold change of PagMYB31 direct target genes in the cambium and differentiating xylem, respectively, of the myb31-7 mutant.

Discussion

PagMYB31 negatively regulates SCW biosynthesis through directly inhibiting the expression of wood-forming regulators

In this study, the transcriptome profiling showed that SCW biosynthetic program was enhanced in the myb31 mutant and repressed in the PagMYB31-OE transgenic plants, showing that PagMYB31 negatively regulates SCW biosynthesis. ChIP and Y1H assays showed that PagMYB31 directly bound to the promoters of 4 PagSDN1s, 4 PagVND6s, and 5 MYB genes (PagMYB2/21, 3/20, and 74), and consistently the genes were all downregulated in the differentiating xylem of MYB31 and MYB31:SRDX transgenic plants. However, in the myb31 mutant, significant upregulation was only observed for PagMYB3/20, 74, PagVND6-A2, B1, C1, and SND1-A2 but not for other direct target genes (3 PagSND1s, MYB2/21, VND6-A1, B2, and C2). It is possible that the CaMV 35S promoter used for OE of PagMYB31 and PagMYB31:SRDX is strong enough to suppress all target genes. Among the 52 PagMYB31 target genes associated with secondary growth, PagMYB3 had the highest enrichment of ChIP DNA and also had more called peaks in its promoter than other PagMYB31 targets (Supplementary Data Set S3; Fig. 5A). We identified 2 binding sites in both PagMYB20 and 21 promoters, and the enrichment level in the 2 sites was different (Fig. 5A). PtrMYB2/21 and 3/20 differ in their ability to activate their target genes, which may be caused by the differential binding affinities of PagMYBs to the secondary wall MYB-responsive elements (SMREs) in the promoters of their target genes (McCarthy et al. 2010; Zhong et al. 2013). The results suggest different binding/repression ability of PagMYB31 on different binding motifs/genes, which could explain the upregulation of a subset of PagMYB31 target genes in the myb31 mutant. Through the integration of RNA-seq and ChIP-seq, we demonstrate that PagMYB31 suppresses SCW thickening mainly through directly inhibiting the expression of PagMYB3/20, 74, VND6-A2, B1, C1, and SND1-A2.

Among all the MYBs that have been identified as important regulators during wood formation, most are transcriptional activators and a few are transcriptional repressors (Wei and Wei 2024). In the yeast transactivation/repression assay, we detected a very low activation activity but did not detect the repressor activity of PagMYB31 (Supplementary Fig. S15), and effector–reporter assay showed that PagMYB31 could activate the promoter activity of PagWOX4, VCM2, and CLE47, which were direct targets of PagMYB31 according to ChIP and Y1H assays. However, the effector–reporter assays showed the promoter activity of other PagMYB31 targets was inhibited by PagMYB31, and consistently the expressions of these targets were upregulated in the mutant and suppressed in PagMYB31-OE transgenic plants. Both PagMYB31 and PagMYB31:SRDX transgenic plants showed reduced SCW thickness in fiber cells and vessels. Adding SRDX domain can turn an activator into a repressor or can enhance the inhibition activity of a repressor. The same phenotype in MYB31 and MYB31:SRDX transgenic plants supports the repressor function of PagMYB31. These results indicate that PagMYB31 may have both transactivation and repression ability at different developmental stages, and these abilities may need different cofactors.

PagMYB31 plays a role in coordinating xylem cell differentiation and wall thickening

GUS staining in the MYB31p:GUS transgenic plants showed that PagMYB31 had a wider expression pattern than SCW regulators that are expressed during xylem cell wall thickening (McCarthy et al. 2010; Ohtani et al. 2011). The consecutive expression of PagMYB31 in the cells within the cambial region and during xylem cell expansion and wall thickening indicate that PagMYB31 may be an upstream regulator of PagSND1s, VND6s, and MYB3/20. PagMYB31 mutation caused various phenotypes in xylem, including thinner walls, larger fiber cells, and larger vessels. The larger vessels, fibers, and pith cells suggest that PagMYB31 negatively regulates cell expansion. However, the longitudinal length of xylem cells displayed an opposite change to the radial length.

Xylem cell expansion occurs before wall thickening and determines the final cell shape and size. This process involves modifications of primary cell walls, which require the activity of expansins, XET/XEH, and PME (Rose and Bennett 1999; Mellerowicz and Sundberg 2008). Expansions are believed to disrupt hydrogen bonds between cellulose microfibrils and cross-linking glycans, such as xyloglucan or xylan, which loosens the cell wall (McQueen-Mason and Cosgrove 1994; Yennawar et al. 2006), and XET is speculated to affect xyloglucan rearrangement (Nishikubo et al. 2011). We observed that many wall-modifying genes were upregulated in the differentiating xylem of the myb31 mutant, including expansin genes PagEXPA4a/b, EXPA17, EXPA15a, and EXPB3; XET genes XTH9, XTH10, XTH28a/b, and XTH30a/b; PL genes PLL18, PL1, PL2, and PL3, indicating the participation of these genes in promoting xylem cell expansion. Glucanase genes PtrCel9A1/PtrKOR1, PtrCel9A6, PtrGH9B4, and PtrGH9C3 were upregulated, supporting the involvement of glucanases in cell expansion (Yu et al. 2013, 2018). We also observed that PagEXPA1, EXPA15b, XTH5, XTH15, XTH16, XTH33, PLL12, and PME3 were downregulated in the differentiating xylem of myb31 mutant. In hybrid aspen, PttPME1 can inhibit intrusive and symplastic cell growth of expanding wood cells (Siedlecka et al. 2008). The downregulation of PagPME3 may take effect for the larger vessels and fiber cells. Many wall-modifying enzyme genes are abundantly expressed in the secondary xylem, indicating that these enzymes have cooperative functions in cell wall expansion or function in different types of cells (Rose and Bennett 1999; Gray-Mitsumune et al. 2004). The OE of some wall-modifying enzyme genes shows different effects on the cell expansion between fiber cells and vessels. For example, PttEXPA1-OE causes increases in fiber cell diameter and vessel length (Gray-Mitsumune et al. 2008), and OE of a XTH gene PtxtXET16-34 promotes vessel growth but not fiber cell expansion (Nishikubo et al. 2011). With the successful CRISPR technique application in trees, these wall-modifying enzyme genes can be knocked out to study the roles of enzymes in the cell expansion of specific types of cells and to study which wall-modifying enzymes participate in cell expansion in longitudinal and radial directions.

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses showed that PagMYB31 could bind to the promoters of PagEXPB3, XTH10, EXPA15a, XTH30b, and PL3, and its mutation caused an upregulation of these 5 genes. PagMYB31 could not directly regulate PagXTH8, but ChIP assays showed that 3 PagMYB31 targets (PagMYB3, MYB158, and NAC127) could directly regulate PagXTH8, indicating a possible cooperative function of PagMYB31 and its target TFs on regulating cell expansion-associated genes. PagMYB31 could directly inhibit PagXCP2, which encodes a protein involved in vacuole autolysis and tonoplast implosion during PCD (Funk et al. 2002; Avci et al. 2008). In Arabidopsis, XCP2 is directly activated by VND7, implying that PagMYB31 can inhibit vessel PCD through antagonistic interaction with PagVNDs. The results showed that PagMYB31 may play an important role in coordinating xylem cell expansion and SCW thickening. The loss of function of PagMYB31 caused increased cell expansion, enhanced SCW deposition, and promoted PCD in vessels. This disturbed cell differentiation may be the reason why vessels were deformed (Fig. 2G).

PagMYB31 regulates cambial cell proliferation and expansion/growth

The activity of vascular cambia determines the lateral growth of trees. PagWOX4 is an important regulator downstream of hormones and peptide signaling pathways regulating cambial activity. Knockdown of PagWOX4a/b in P. alba × P. glandulosa caused a decrease of cambial activity, which is the same as the effect of WOX4 perturbation in other poplar species (Kucukoglu et al. 2017; Tang et al. 2022). RNA-seq of the phloem–cambium showed that PagWOX4 was downregulated significantly in the myb31-7 mutant, indicating that PagMYB31 mutation caused a decreased layer of cambial cells through inhibiting PagWOX4 expression.

Among the 12 TFs that have been identified as regulators of cambium activity, including 4 HD ZIP III proteins and 2 MADS-box proteins VCM1/2 (Du et al. 2009, 2011; Robischon et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2013, 2018; Hou et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2021), we observed that, besides PagWOX4b, 2 other TF genes, PagVCM2 and PagMYB199, were downregulated in the myb31-7 mutant. These 2 genes are involved in the auxin signaling in cambium. Auxin has a concentration gradient through the phloem, cambium to xylem, with a peak at the cambial region. OE of PtoARF7 improves cambial activity through direct regulation of PtoARF7 on WOX4 (Hu et al. 2022), and auxin suppresses the expression of PagMYB199, which negatively regulates vascular cambium activity (Tang et al. 2020), showing the role of auxin in cambial cell proliferation. In poplar, both VCM1 and VCM2 modulate subcellular homeostasis of auxin through directly regulating PIN5 (Zheng et al. 2021). We also observed downregulation for PagPIN5 and PagPIN6, consistent with the result that VCM activates PIN genes. However, poplar with OE of VCM1 displays fewer layers of cambial and xylem cells, showing that VCM1 negatively regulates cambial proliferation activity. The downregulation of PagVCM2 in the phloem–cambium of the mutant is not consistent with the decreased cambial activity. Similarly, the decreased cambial activity is not consistent with the downregulation of PagMYB199, a negative regulator of cambial cell proliferation. Through ChIP and transcriptome profiling, we have shown that PagMYB31 directly regulated PagMYB72, which could inhibit the expression of PagWOX4, PagVCM2, and PagMYB199, indicating that the downregulation of these 3 genes may be caused by the upregulation of PagMYB72 in the myb31 mutant. The MYB31-MYB72-WOX4 module regulates cambial activity in the opposite direction to MYB31-MYB72-VCM2/MYB199 modules, indicating that PagMYB31 both positively and negatively regulates cambial activity. PagMYB31 may play an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of cambial activity.

We also observed a downregulation of 2 CLAVATA3/ESR (CLE)-related protein genes PagCLE47 and PagCLE44 in phloem–cambium of the myb31-7 mutant (Supplementary Data Set S4). PttCLE47 is expressed in cambium and promotes cambial proliferation (Kucukoglu et al. 2020). CLE44 is mainly synthesized in phloem and moves to cambium to regulate WOX4 activity (Hirakawa et al. 2008); thus, the downregulation of PagCLE44 and PagCLE47 occurs in the phloem and cambium, respectively, and their downregulation in the myb31-7 mutant indicated inhibited TDIF/PXY signaling, which should play a role in inhibiting PagWOX4 expression. Compared to inhibition effects by the downregulation of PagWOX4, the effect of MYB72-VCM2/PIN5/MYB199 modules to promote cambial activity appears weaker. We speculate that the decreased cambial activity is mainly caused by the downregulation of PagWOX4. In the snRNA-seq analysis, PagWOX4b was downregulated in 2 cambium clusters, 7 and 13, while PagCLE47 and PagVCM2 were downregulated in Cluster 13 and Cluster 7, respectively, indicating that PagMYB31 regulates the TDIF and auxin signaling in different cells or different developmental stages of cambium development.

In this study, the involvement of PagMYB31 during wood formation in poplar was revealed through gene perturbations (mutation and OE), and its functioning mechanism was studied by gene expression profiling and target identification. The number of DEGs identified by snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptome analyses was much less than the number identified by RNA-seq. This is caused by the low gene expression level in a single cell in the snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptome analyses, especially for TF genes. While for non-DEGs in the RNA-seq analysis, some were differentially expressed in snRNA-seq analysis, such as the upregulation of PagSND1-A2 and PagbHLH186 (direct target of PagMYB74) in Cluster 1 of the myb31-7 mutant (Fig. 4G), suggesting that the products of these 2 genes function in the early stage of SCW thickening and supporting that PagSND1-A2 is 1 direct target of PagMYB31. snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptome analyses are better for studying cell fate transition than traditional transcriptome analysis (Rodriguez-Villalon and Brady 2019).

We found that PagMYB31 is a coordinator regulating cambial proliferation, xylem cell expansion, SCW thickening, and PCD during wood formation. It has dual functions in wood formation, positively regulating cambial proliferation and negatively regulating xylem cell development (cell expansion and SCW thickening). Dual functions have been identified for several TFs in the coordination of cambial proliferation and xylem differentiation and in the coordination of cell expansion and wall thickening. For example, WOX4 may also regulate xylem differentiation in Arabidopsis, because the xylem network is largely interfered in wox4 mutant (Zhang et al. 2019). PagMYB199 is expressed in both vascular cambium and developing xylem, and it negatively regulates both cambial proliferation and SCW thickening (Tang et al. 2020). However, the upregulation of PagMYB199 in differentiating xylem and downregulation in phloem–cambium of the myb31-7 mutant is not consistent with the negative function of PagMYB199. PagMYB199 is one of genes affected by PagMYB31 perturbation, and the contributions of genes downstream of PagMYB31 may be different. Many genes associated with cambial activity maintenance, cell expansion, and SCW biosynthesis are direct targets of PagMYB31, suggesting the coordination of PagMYB31 in regulating these processes. PagMYB31 could also inhibit cambial cell expansion because mutation of PagMYB31 resulted in larger fusiform initials and ray initials, indicating that PagMYB31 can suppress cambial cell differentiation. PagMYB31 activated several cambium-specific target genes and also inhibited genes of TFs regulating SCW biosynthesis, as shown by effector–reporter assay, ChIP and Y1H. In a recent study, 4 class A-ARFs were identified as negative regulators of fruit initiation and positive regulators of fruit growth in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), through spatiotemporal regulation on different target genes (Hu et al. 2023). Our results show that PagMYB31 negatively regulates cell expansion and SCW thickening, through directly inhibiting wall-modifying enzyme genes and wood-forming regulator genes, respectively, while it regulates cambial activity through regulating PagWOX4 expression in multiple pathways. Its activity is required in the coordination of the consecutive developmental steps of wood formation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth environment

Populus alba × Populus glandulosa “84K” and N. benthamiana plants were grown in peat moss (Sphagnum) and maintained in a phytotron with a long-day condition (25 °C during the day and 23°C at night). The sterile P. alba × P. glandulosa plants were propagated through cuttings on 1/2 MS media (pH 5.8 to 6.0) supplemented with 30-g/L sucrose, 5-g/L agar, 0.05-mg/L indolebutyric acid, and 0.02-mg/L naphthylacetic acid.

Genome assembly and annotation

DNA library was prepared using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 and sequenced on PacBio Sequel II (PacBio, CA, USA). High-quality long-read sequences (HiFi reads) were assembled using the HiCanu (Koren et al. 2017). The “minlength,” “coverage,” and “genomesize” were set to 300, 50 and 900 Mb, respectively, and other parameters were set to default values. The assembly-stats tool (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/assembly-stats) was used to determine assembly statistics for the genome.

Annotation was conducted using MAKER (Cantarel et al. 2008). Transcript sequences (Huang et al. 2020) were provided to MAKER as EST evidence. Trinity was performed following the Trinity pipeline for paired-reads assembly using default parameters. Protein evidence was obtained from 8 species, including Populus trichocarpa (Tuskan et al. 2006), P. alba (Liu et al. 2019), Populus tremula (Ingvarsson and Bernhardsson 2020), shrub willow (Salix suchowensis and Salix purpurea) (Hirakawa et al. 2008) (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov), Arabidopsis (Berardini et al. 2015), grape (Vitis vinifera) (Jaillon et al. 2007), and rice (Oryza sativa) (Ouyang et al. 2007). For ab initio prediction, the gene predictor models of SNAP, AUGUSTUS, and GeneMark-ES were trained by the above transcript sequences and were used in the MAKER run. Finally, the transcript, homology, and ab initio gene sets were merged to form a comprehensive nonredundant gene set using EVM (EvidenceModeler) (Haas et al. 2008). Repetitive elements were identified using RepeatModeler (Flynn et al. 2020) and RepeatMasker (Tarailo-Graovac and Chen 2009).

RT-qPCR analysis

Different tissues, including leaves, roots, xylem, and phloem–cambium, were collected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. After the bark was peeled, differentiating xylem and phloem–cambium were scraped using single-edged razors from the xylem and bark sides, respectively. Total RNA was extracted using the CTAB method (Lorenz et al. 2010); 150-ng total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). qPCR was performed on the Roche Light Cycler 480 II with the Green Premix Ex Tag II (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Gene expression levels were determined as relative to the reference gene PagACTIN by the 2−ΔCT calculation. Each measurement was performed with 3 replicates and was repeated in 3 biological replicates. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data Set S6.

GUS assay

The GUS assay was performed as previously reported (Zhou et al. 2019). Stem cross sections (50 μm) from 1-mo-old trees were first placed in precooled 90% (v/v) acetone for 20 min to prevent the diffusion of GUS signals and then washed with washing buffer (20 mm NaHPO4, pH7.2, 1 mm K3Fe(CN)6, 1 mm K4Fe(CN)6, and Triton X-100) 3 times for 2 min each time. The samples were incubated in staining solution (1 mm X-Gluc in washing buffer) at 37 °C overnight (vacuum was applied to make sure samples were sunk). Samples were cleared in 70% (v/v) ethanol and observed under an Olympus DP74 digital camera (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

RNA-seq

RNA-seq library construction and sequencing followed a previous study (Huang et al. 2022). Gene alignment and annotation were carried out using the P. alba × P. glandulosa genome v.3.1 in this study. DEGs were analyzed using DESeq2 software with an adjusted P-value of <0.05. GO enrichment and KEGG analysis were performed at the omicshare website (https://www.omicshare.com/).

Subcellular localization

The coding region of PagMYB31 was cloned into PHG (WEIDI, Shanghai, China), generating 2 × 35S-PagMYB31:GFP. The construct was transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves via A. tumefaciens GV3101, and the signal was captured using a confocal microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss). The excitation wavelength and emission wavelength are 488 and 492 to 543 nm, respectively.

Vector construction and plant transformation

The full-length coding region of PagMYB31 was PCR amplified from P. alba × P. glandulosa xylem cDNA and cloned into pBI121-35S-SRDX (Wang et al. 2021) by Exnase II-mediated recombination (ClonExpressII One Step Cloning Kit, Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), generating pBI121-35S-PagMYB31:SRDX. For OE of flag-tagged PagMYB31, 3 × flag was amplified from pCAMBIA1307-Flag:HA (Li et al. 2015) and cloned into pBI121-2 × 35S-miR408 to produce pBI121-2 × 35S-3 × flag. PagMYB31 was cloned into this vector using ExnaseII, generating pBI121-2 × 35S-3 × Flag:PagMYB31. The promoter (2.0 kb) of PagMYB31 was amplified from genomic DNA and inserted into pBI121 vector using Exnase II, generating pBI121-PagMYB31p-GUS for gene expression analysis. The PagMYB31 knockout mutant (myb31) was generated by the CRISPRCas9 system (Ma et al. 2015). The sgRNA sequences were designed using CRISPR-P2.0 (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/). Primers used in vector constructions are listed in Supplementary Data Set S6. Constructs were transformed into A. tumefaciens GV3101. For the transformation in P. alba × P. glandulosa, injured leaves were used as explants (Zhou et al. 2019) for transgene (PagMYB31:SRDX, 3 × Flag:PagMYB31, and PagMYB31p:GUS) OE, and callus was used as explants (Chai et al. 2014) for generating the knockout mutant.

Histological analyses

Stem cross sections of 50-μm thickness were prepared from the 5th, 10th, and 15th internodes of 1.5-mo-old P. alba × P. glandulosa using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S, Nussloch, Germany), stained with 0.05% (w/v) toluidine blue O (TBO), and observed under an Olympus DP74 digital camera (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Xylem width was measured using ImageJ software from 3 independent plants. The debarked stem of the 10th internode of the myb31-7 mutant and WT was cut into pieces of 1 cm long and was macerated to dissociate xylem cells as previously described (Huang et al. 2022). The materials were stained with TBO and observed under a light microscope (Olympus BX51), and measurements were taken from 50 cells from 3 plants for each line.

SEM analysis

Stem cross sections of 50-μm thickness were prepared from 1.5-mo-old P. alba × P. glandulosa trees and fixed in 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde overnight. After rinsing in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and gradient dehydration, critical point drying was conducted for about 2 h. The samples were coated with gold at 10 mA for 120 s and observed under a Thermo Fisher Quanta FEG 450 SEM. Cell size and wall thickness were measured using ImageJ software in at least 50 cells from 3 independent plants.

Wood composition analysis

Stem tissue below the 13th internode from 7-mo-old plants was collected and dried at 55°C to constant weight. The wood was ground to 40 to 60 mesh. The chemical composition was determined according to the previous study (Lu et al. 2021), with 3 independent measurements for each sample.

NI analysis

The stem portions with a diameter of >1 cm were collected from 7-mo-old trees, and bark was removed. After natural drying, a sloping (45°) apex with an area of about 1 mm was polished with a diamond knife to acquire an ultrasmooth surface (Ultracut, Leica, Germany). Before testing, the polished sample was placed in the NI sample chamber for at least 4 h to achieve equilibrium with the conditions of the sample chamber. NI tests were performed on a nanomechanical test instrument (TI 950 TriboIndenter, Hysitron Inc., USA) equipped with a 3-sided pyramid diamond indenter tip (Li et al. 2023). Indentation was executed in a load-controlled mode of a 3-segment load ramp (loading/holding/unloading in 5/2/5 s) with a peak force of 40 μN. Three different locations in each sample were selected for testing, and about 20 valid values for each cell from WT and mutant were determined to obtain the elastic modulus (Er) and hardness (H), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S16.

Antibody production and western blotting

The full-length coding sequence of PagMYB31 was amplified with primers (Supplementary Data Set S6) and cloned into pET32a vector (Novagene, USA). IPTG (1 mg/mL) was used to induce protein expression, and recombinant proteins were purified using Ni-NTA-Beads-6FF and were used to inject a mouse for monoclonal antibody production (Shanghai Abmart Inc., China).

Two grams of differentiating xylem were ground in liquid nitrogen. The powder was put in 2-mL precooled lysis buffer (20 mm Tris–HCl, pH7.5, 20 mm KCl, 2 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 250 mm sucrose, 25% [v/v] glycerol, and 5 mm DTT). The mixture was filtered through miracloth and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet was transferred into a new tube and suspended in 20-mL precooled NRBT buffer (20 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 25% [v/v] glycerol, and 0.2% [v/v] Triton X-100). After centrifugation, the pellet was washed with precooled NRBT buffer 4 times. Western blotting was performed with either anti-PagMYB31 antibodies (1:750 dilution, overnight hybridization) or anti-FLAG (peptide sequence DYKDDDDK) antibodies (CW0287, CWBIO, 1:1,000 dilution), for 4 h. After hybridization with the secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, CW010, CWBIO, 1:1,000 dilution) for 2 h, the signals were detected using the Immobilon Western-HRP Substrate Luminol Reagent (Millipore).

Immunohistochemistry analysis

The IHC analysis was conducted according to a previous study with some modifications (Tang et al. 2022). The stems at the base internode of tissue-cultured WT and myb31-7 plants were cut into 20-μm thick sections using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S, Nussloch, Germany) and then fixed with acetone. Blocking solution (PBS with 0.5% [v/v] normal goat serum and 1% [w/v] BSA) was applied to the sections for 1.5 h. The sections were then incubated in PBS buffer containing anti-PagMYB31 antibodies (1:200 dilution) for 1 h, rinsed in PBS for 10 min, and transferred to PBS buffer containing goat anti-mouse IgG(H + L)/HRP-conjugated antibodies (A0216, Beyotime, China) (1:2,000 dilution) for 2 h. The sections were then stained with BCIP/NBT and observed under an Olympus DP74 microscope equipped with a digital camera (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

snRNA-seq analysis

After bark was peeled, differentiating xylem and phloem were scraped from xylem and bark sides using single-edged razors. Two samples were mixed in equiweight, and nuclei were isolated following previous references (Conde et al. 2021; Sunaga-Franze et al. 2021). snRNA-seq library construction and sequencing were performed as described previously (Li et al. 2021). A total of 10,516 nuclei were obtained from the WT sample, with an average sequencing depth of 43,792 reads per cell, and 9,553 nuclei were obtained from the myb31-7 sample, with an average sequencing depth of 47,652 reads per cell (Supplementary Data Set S2). Bioinformatic analysis was performed using Omicsmart, a real-time interactive online platform for data analysis (http://www.omicsmart.com). The P. alba × P. glandulosa V3.1 genome was used to align the snRNA-seq reads, and gene expression levels were identified by cellranger. Further analysis was conducted using the Seurat software (Butler et al. 2018). Clusters were identified using the Seurat function FindClusters with resolution = 0.5 and visualized by UMAP (Milošević et al. 2022). Cluster marker genes (cluster-enriched genes) were identified using FindAllMarker, with the settings “min.pct = 0.25” and “log2fc.threshold = 0.36” (Satija et al. 2015).

Spatial transcriptome analysis

Stem fragments of 5 mm long at the 9th internode from 2-mo-old trees were embedded in cold optimal cutting temperature compound and cryosectioned. The cDNA library was constructed according to the manufacturer's instructions on the 10× Visium platform, and the 10× Genomics platform was used for the library sequencing. We used our assembled V3.1 genome to align the seq data and official 10× Genomics software Space Ranger for data comparison and gene quantification. At the same time, based on the quantitative results identified by the Space Ranger, the data were subsequently analyzed using Seurat software (Satija et al. 2015). Based on the sequencing data of each sample, the detected spots in each sample were grouped and identified by the spatial transcriptome RNA-seq data analysis process, and the types of spots were identified. Each sample was normalized using the SCTransform algorithm in Seurat (Zheng et al. 2017). UMAP algorithm was used for data visualization, and gene expression changes were finally visualized via SpatialFeaturePlot (Milošević et al. 2022).

ChIP-seq analysis