Abstract

Emerging consumer demand for safer, more sustainable flavors and fragrances has created new challenges for the industry. Enzymatic syntheses represent a promising green production route, but the broad application requires engineering advancements for expanded diversity, improved selectivity, and enhanced stability to be cost-competitive with current methods. This review discusses recent advances and future outlooks for enzyme engineering in this field. We focus on carboxylic acid reductases (CARs) and unspecific peroxygenases (UPOs) that enable selective productions of complex flavor and fragrance molecules. Both enzyme types consist of natural variants with attractive characteristics for biocatalytic applications. Applying protein engineering methods, including rational design and directed evolution in concert with computational modeling, present excellent examples for property improvements to unleash the full potential of enzymes in the biosynthesis of value-added chemicals.

Keywords: Protein engineering, Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CAR), Unspecific Peroxygenase (UPO), Directed evolution, Flavor and fragrance

1. Introduction

Flavors and fragrances are organic compounds that interact with our taste and olfactory senses to bring an overall enjoyment of the products.1-3 Since the introduction of vanillin and coumarin to the market in the 19th century, the global demand for flavors and fragrances has steadily increased, with an expected market value of $30.5 billion by 2024.4 This is driven by the rising demand for consumer products, e.g., food, beverages, personal care, and cosmetics, with enhanced tastes and aromas.1, 4 Most flavor and fragrance molecules belong to groups of compounds, including aromatics, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, fatty acids, esters, pyrazines, terpenes, and lactones (Figure 1A).5 Based on the origin, they can be categorized as natural, nature-identical, and artificial ones.3 Natural flavors and fragrances are directly isolated from natural resources, such as plants or animals. Nature-identical flavors and fragrances have the same chemical composition as the natural counterpart but are synthetically produced via chemical or biotechnological methods. Artificial flavors and fragrances are synthetic compounds which do not exist in nature.6 While the flavor and fragrance industry continues to develop novel aromas and tastes to meet consumer demand, there is an increasing concern about the potential adverse health and environmental effects of some chemically synthesized compounds. Many synthetic flavor and fragrances have unknown toxicological properties and may persist and accumulate in the environment.1 This has driven a shift in the market toward safer production methods that can emulate the cost efficiency and production volumes of chemical synthesis while reducing risks.5

Figure 1.

Protein engineering in the production of flavors and fragrances. (A) Main flavor and fragrance families. (B) Protein engineering overview.

Arising from natural evolution, enzymes accelerate essential chemical transformations in life processes.7, 8 They have also traditionally been used in the food industry to help unlock appealing flavors and tastes. With the development of modern biotechnology, enzymes are becoming indispensable catalysts for (bio)synthetic chemists due to their superior properties, including chemoselectivity, regioselectivity, stereoselectivity, mild reaction conditions, and reduced waste generation.9 Although native enzymes perform well under conditions relevant to the original hosts’ physiological conditions, they are limited in substrate scope, reaction rate, and stability in industrial applications. To overcome these issues, researchers have turned to protein engineering to generate enzymes with tailored substrate specificity, improved catalytic activity, as well as enhanced stability in organic solvents, raised temperature, and extended reaction time. (Figure 1B).8-12 In recent years, engineered enzymes have expedited the growth of the food industry. Several well-studied examples include lipases, proteases, alcohol dehydrogenases, and hydrolases.5, 9, 13, 14 This review summarizes progress in harnessing enzymes for flavor and fragrance synthesis, with a focus on two enzymes, i.e., carboxylic acid reductase (CAR) and unspecific peroxygenase (UPO). We start with a brief review of the current status of flavor and fragrance production, the background knowledge of the two enzymes’ structure, function, and applications, followed by an extensive discussion on recent engineering efforts to improve their industrial performance. We conclude the review with a summary and future perspectives on protein engineering and enzymatic for flavor and fragrance production applications.

2. Flavor and fragrance production through natural extraction and chemical syntheses

The vast majority of flavors and fragrances used in the market are either natural extractions or chemically synthesized.3 Direct extraction from natural sources like plants represents the original practice of producing natural flavors and fragrances. It has a long history of use throughout human civilization. Conventional techniques for capturing the target compounds utilize separation methods, including distillation, cold pressing, and solvent extraction.2 Due to the relatively low process efficiency and product yield, these traditional approaches are energy-intensive, time-consuming, and, most importantly, require immense quantities of raw materials, for which the availability is subjected to various risk factors, such as weather patterns, plant diseases, and trade restrictions.2, 3, 5, 13 Consequently, the industrial production of flavors and fragrances migrates to chemical synthesis methods for better economic outcomes.5, 15

Numerous organic synthesis routes are available to create aromatic and aliphatic compounds with flavor and fragrance properties. In addition, organic synthesis represents the most effective and cheaper approach for discovering novel compounds with unique olfactory and taste profiles, as it allows easy structural modifications.16, 17 However, chemical syntheses suffer from multiple issues that lead to increased production costs and adverse environmental impacts. For example, the lack of selectivity causes the formation of byproducts, which require extensive downstream separation and purification to isolate the target compound.3, 13 Moreover, many synthetic routes require toxic metal catalysts, use petrochemical feedstocks, generate hazardous wastes, and demand significant energy inputs.13, 15 One example is the processes of producing aromatic aldehydes and esters, which use hazardous reagents and generate a significant amount of waste.13, 18 Concerns over the environmental tolls from their large-scale application in industrial processes have grown in recent years. Consumers are also more conscious of the potential adverse health effects of impurities of chemically synthesized products.1, 19 The low sustainability profile and the consumer trend have stimulated research efforts into developing biotechnological methods for the green syntheses of flavor and fragrance molecules with low environmental impacts, improved product safety, and economic gain.3, 5

3. Enzymes in flavor and fragrance production

The production of flavors and fragrances is moving into more sustainable methods enabled by modern biotechnology. Compared to traditional extraction methods from natural sources, biocatalytic syntheses often produce products at higher yields from renewable or recycled starting materials.5, 20 Furthermore, biocatalytic approaches avoid the use of hazardous reagents, harsh reaction conditions, high pressure and temperature, and organic solvents.13, 19, 21 Currently, around 1.5% of the global market of flavor and fragrance molecules are produced through enzymatic synthesis.5 Prominent enzyme families in these applications include lipases, alcohol dehydrogenases, and proteases.5, 19, 21 Lipases catalyze the esterification of flavors from fatty acids and alcohols and often have broad substrate promiscuity. Consequently, they are widely used to produce isoamyl acetate (banana flavor), geranyl acetate (rose fragrance), and citronellyl acetate (lemon flavor).13, 19, 22 Alcohol dehydrogenases are gaining popularity for producing fatty aldehydes like hexanal (fruity fragrance) and monoterpene alcohols like geraniol (floral scent).15, 23 Proteases or proteolytic enzymes are commonly used to hydrolyze peptide bonds of protein sources to produce savory and meat-like flavors.24-26 These are well-characterized enzymes and have been reviewed extensively for their applications.5, 9, 13, 20 Here, we cover two types of oxidoreductases, i.e., carboxylic acid reductases (CARs) and unspecific peroxygenases (UPOs), which emerged recently as versatile biocatalytic enzymes but have received comparatively less attention for the flavor and fragrance production.

3.1. Carboxylic Acid Reductase (CARs)

CARs (EC 1.2.1.30), also known as aldehyde oxidoreductases,27 are large multi-domain enzymes found in both fungi and bacteria.28-30 They can reduce numerous carboxylic acids into the corresponding aldehydes. The unique catalytic capability, broad substrate specificity, and relaxed reaction conditions make CARs a valuable tool for organic synthesis, including the production of flavors and fragrances that would otherwise require toxic chemicals and harsh reaction conditions.30-32

3.1.1. Structure and function of CARs

CARs consist of three domains: an adenylation domain (A-domain), a phosphopantetheine carrier protein domain (PCP-domain), and a reduction domain (R-domain) (Figure 2A).28, 29 The A-domain resides at the N-terminus of CAR and shares homology with the ANL superfamily of adenylation enzymes. Like other members of the ANL superfamily, CAR’s A-domain consists of a static (Acore) and a mobile subdomain (Asub). While the Acore contains the binding pockets for ATP, Mg2+, and the substrate, the Asub changes conformation to accommodate the PCP-domain for thiolation.28, 33 The PCP-domain is located between the A-domain and the R-domain. It is post-translationally modified by attaching a phosphopantetheine moiety at a conserved serine residue by a phosphopantetheine transferase enzyme.34 Lastly, the R-domain is at the C terminus and shares homology with proteins belonging to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) superfamily. It contains the conserved NADPH binding motif of TGXXGXXG. CAR enzymes perform the direct and irreversible catalytic reduction of carboxylic acids into aldehydes.28, 30, 33 The catalytic cycle starts with the activation of the free acid by an ATP in the A-domain to form an acyl-adenylate intermediate (Figure 2B). During this process, Mg2+ serves as a Lewis acid to neutralize both ATP and the byproduct pyrophosphate (PPi). Following substrate adenylation, thiolation at the phosphopantetheine group leads to a covalent intermediate which is transferred to the reduction domain. Lastly, a NADPH-dependent reduction of the acyl-thioester yields the aldehyde product and NADP+. The structural and functional properties have been reviewed.29, 30, 33

Figure 2.

Structure and function CARs. (A) Crystal structures of SrCAR. Color code: A-domain Acore, green; A-domain Asub, yellow; PCP-domain, red; R-domain, blue. (B) Schematic overview of CAR catalytic mechanism.

3.1.2. Applications of CARs

CARs have been exploited to produce flavor and fragrance molecules. Besides benzoic acid, which is taken as the native substrate, CARs demonstrate a broad substrate specificity for the syntheses of a wide variety of aromatic, aliphatic, hydroxylated, and long-chain fatty aldehydes that are highly valuable in the production of flavors, scents, and fragrances. Previous reports have shown that CARs can take modified benzoic acids as substrates and tolerate various functional groups on the phenyl ring to enable the synthesis of substituted benzaldehyde and heterocycle derivates, including flavor molecules vanillin, furan-2-carbaldehyde (furfural) and 4-methoxybenzaldehyde (p-anisaldehyde).31, 35, 36 Additionally, CARs can reduce aliphatic mono-, di- and tricarboxylic acids to generate fragrant compounds such as octanal, nonanal, and decanal.31, 37 Hydroxy acids like 6-hydroxyhecanoate and lactate also serve as CAR substrates, producing aldehydes as the precursors for the manufacturing of numerous industrial chemicals including flavors, fragrances, and pharmaceuticals.38 CARs can even reduce long-chain fatty acids containing up to 18 carbons to yield aldehydes with waxy and citric aromas.31, 37, 39, 40 Beyond single-enzyme reduction, CARs were also integrated into biotransformation cascade systems for biosynthesis. Complex compounds can be produced with excellent yields by combining CARs with various oxidases, dehydrogenases, transaminases, and cofactor regeneration enzymes. For example, CAR was combined with transaminases to produce 1,6-hexamethylenediamine, a key precursor for nylon synthesis, from adipic acid in a one-pot reaction.41 One significant challenge associated with the in vitro application of CARs is the requirement of expensive cofactors including ATP and NADPH. Several examples have demonstrated the successful cofactor recycling in CAR-catalyzed reactions. One used polyphosphate kinases/polyphosphate and glucose dehydrogenase/glucose to regenerate ATP and NADPH, respectively (Figure 2C).42 A recent report demonstrated a nanoconfined three-enzyme cascade consisting of ferredoxin, pyruvate kinase, and adenylate kinase for electrical and chemical energy-driven cofactor recycling.43 CARs have also been applied to whole-cell biosynthesis. For example, 3-hydroxytyrosol, an olive antioxidant, was synthesized from 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. The reduction of the acid starting material to the corresponding aldehyde was carried out by Escherichia coli cells overexpressing CAR and a phosphopantetheine transferase. Whereas the host cells’ endogenous reductase activity converted 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde to 3-hydroxytyrosol. The whole-cell system provides the advantage of supplying required cofactors through cellular metabolism (Figure 2C).44 Furthermore, individual domains of CARs can also function as biocatalysts to produce amides, esters, thioesters, and lactams from carboxylic acid, alcohols, and aldehydes.45-51 Overall, the ability to work in isolation or in concert with other enzymes, and the domain modularity of CARs make them exceptional tools for the sustainable bioproduction of compounds that are important in the flavor and fragrance industries.

3.2. Unspecific Peroxygenases (UPOs)

UPOs (EC 1.11.2.1) are a versatile class of fungal glycosylated heme-thiolate enzymes that catalyze the oxyfunctionalization reactions using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as the sole source of oxidizing equivalents and oxygen atoms.52 UPOs were first isolated from the edible mushroom Agrocybe aegerita.53 Based on the polypeptide chain length and structural features, UPOs are generally divided into two families: short UPOs (Family I) and long UPOs (Family II).54-57 UPOs perform cofactor-free, H2O2-dependent substrate hydroxylation, epoxidation, oxidative dealkylation, aromatic ring oxidation, ether cleavage, and one-electron oxidations across a wide range of compounds, including alkanes, ethers, aromatics, and heterocycles.52, 55, 57-64 The expansive substrate scope, simple co-substrate requirement, high turnover numbers, and often high selectivity make UPOs attractive biocatalysts for sustainable biosynthesis, including the production of flavors and fragrances.

3.2.1. Structure and function of UPOs

UPOs are extracellular enzymes secreted by fungal hosts. Since the discovery in 2004, several thousands of putative UPO sequences have been identified in databases, around 30 have been characterized, although their native biological functions remain unknown.57, 62, 63, 65, 66 UPOs contain heme as a prosthetic group, which is covalently linked to an axial cysteine residue through the iron.55 Short UPOs, with a mean size of 30 kDa, are predominately dimers that are connected by a disulfide bond.55, 60 One exception is a recently reported monomeric enzyme from Hypoxylon sp. EC38.67 In contrast, long UPOs, with mean size of 44 kDa, are monomeric proteins that contain an intramolecular disulfide bond for structural stabilization.55 The two UPO families share similar active site motifs as a reflection of similar catalytic mechanisms.60 A highly conserved - PCP-EHD-S-E- motif exists in short UPOs (Figure 3A), while long UPOs have a -PCP-EGD-S-R-E- motif (Figure 3A). The PCP motif features the thiolating cysteine residue with flanking prolines to ensure the exposure of the sulfhydryl group. A magnesium ion (Mg2+), which is proposed to stabilize the strained porphyrin system, is coordinated partially by the EHD-S or the EGD-S motifs (contributing residues are underlined). All structurally characterized UPOs have a glutamic acid residue (E) that acts as an acid-base catalyst in the heterologous cleavage of H2O2. This negatively charged residue is stabilized by a histidine (in the EHD motif) in the short UPOs, and an arginine (R) in the long UPOs.

Figure 3.

Structure and function of UPOs. (A) Structure of Marasmius rotula UPO (short UPO) (PDB ID: 5FUJ) and Agrocybe aegerita UPO (long UPO) (PDB ID: 2YP1). Active site motifs are shown as sticks. (B) Schematic overview of UPO catalytic mechanism.

Differences in amino acid composition of the heme access channels lead to divergent substrate scopes for the two types of UPOs. The channel in short UPOs is wider and lined with flexible aliphatic amino acids. As a result, short UPOs are capable of oxidizing bulky, hydrophobic compounds, such as cortisone, prednisone, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.68, 69 Meanwhile, long UPOs have longer but narrower channels due to bulky aromatic residues, limiting their substrates to small aromatic and linear substrates.55, 60 Taking AaeUPO as an example, its structure-function studies revealed restricted substrate scope to large aromatic hydrocarbons, such as pentacene and perylene, due to steric clashes with the enzyme’s active site residues.70

UPOs catalyze the oxidation of non-activated C-H, C-C, and C=C bonds following a peroxide ‘shunt’ pathway of the P450-type monooxygenases via an oxo-ferryl cation radical species known as compound I (Cpd I) (Figure 3B).60 Formation of Cpdl is initiated when the distal water ligand is replaced with H2O2 followed by deprotonation by the conserved glutamic acid to form a negatively charged ferric-peroxo complex, designated as compound 0 (Cpd0, Figure 3B), which undergoes an internal electron rearrangement to produce CpdI. The strong oxidant CpdI abstracts a hydrogen atom from the substrate to form a ferryl hydroxide complex (compound IIa, CpdIIa, Figure 3B) and an alkyl substrate radical, which quickly recombine to form the hydroxylated product and regenerate the resting state ferric heme cofactor.52, 55, 62 UPOs often possess unwanted peroxidase activities due to single-electron deprotonations of substrates by CpdI (CpdIIc, Figure 3B), which lead to the release of radicals that undergoes coupling or disproportionation reactions. Meanwhile, it was proposed that a ferryl alkoxy radical similar to CpdII (CpdIIb, Figure 3B) is formed in epoxidation reactions without subsequent hydrogen abstraction.71

The broad substrate scope of UPOs leads to diverse product formation. In general, aliphatic alkanes are hydroxylated to form alcohols, and small linear or branched alkenes are oxidized into epoxides. Meanwhile, the regioselectivity of an UPO is substrate-dependent. For example, the AaeUPO specifically oxidized propane and butane at the C2 position but produced both 2- and 3-alcohols when C5-C8 linear alkanes were provided as the substrates.72 In the cases of linear alkenes with terminal double bonds or cycloalkenes, formation of both alcohol and epoxide products were observed.71, 73 Besides hydroxylation and epoxidation of hydrocarbons, UPOs have also been shown to catalyze the O-dealkylation of ethers,55 N-dealkylation of amines,55 oxidation of sulfides into sulfoxides,74 and the oxidation of bromides into hypobromites.52 Structural and functional properties of UPOs have been extensively reviewed.52, 55, 60

3.2.2. Applications of UPOs

Currently discovered UPOs display excellent substrate coverage and promiscuity, with nearly 400 oxidizable substrates identified, including aromatics and aliphatic (alkanes, fatty acids, fatty alcohols, and steroids) compounds that are important for the flavor and fragrance industry. The repertoire of oxygen transfer reactions catalyzed by UPOs is also extensive, encompassing epoxidation, bromide oxidation, sulfoxidation, N-oxidation, aromatic peroxygenation, aliphatic hydroxylation, and ether cleavage.52, 55, 57-64 For example, UPOs enable the hydrolytic cleavage of C4-C5 bonds in C8-C12 fatty acids, followed by a spontaneous lactonization to produce the corresponding γ- and δ-lactones which have fruit-like flavors.75 UPO has also been applied to the production of fragrances 3-hydroxy-α-ionone and 3-oxo-α-ionone through the hydroxylation of α-ionone and the oxidation of terpenes.76, 77 When incorporated into multi-enzyme systems, the versatile chemistry of UPOs can be leveraged to synthesize valuable compounds through cascade reactions with enhanced efficiency and selectivity.78 In comparison to P450 enzymes, which catalyze similar oxyfunctionalization reactions, UPOs do not require auxiliary flavoprotein and nicotinamide cofactor and therefore are easier to manipulate. In summary, the unique properties of UPOs render them promising biocatalysts for the synthesis of diverse value-added chemicals.

4. Enzyme engineering of CARs and UPOs

Enzymatic catalysis offers a selective and environmentally friendly approach to the synthesis of chemicals. However, its widespread industrial implementation still needs to overcome substantial barriers, such as low product yields, reduced selectivity, prolonged reaction times, particularly on nonnative substrates, reliance on expensive cofactors, and diminishing stability under process conditions that deviate from physiological temperature and pH.9 To improve the catalytic performance and expand the biocatalyst repertoire, advanced enzyme engineering techniques have been developed and applied.14, 79

4.1. Enzyme engineering methodology

Rational design and directed evolution are two major approaches in enzyme engineering. Rational design relies on the elucidated sequence-structure-function relationship to strategically target residues or regions that likely play essential roles in catalytic properties for mutagenesis (Figure 1B).8, 80 Structure-based rational design starts from solved enzyme crystal structures or computationally generated homology models to redesign the shape, chemical and electronic properties of the active site for improved binding and catalytic turnover. Successful implementation of the method requires extensive knowledge of the functionality of active site residues. It is often combined with computational simulations based on quantum/molecular mechanics to evaluate the effect of mutagenesis.8, 81 Sequence-based rational design is an alternate approach when the structural information is missing, but the sequence-function correlation is well defined. Through analyzing homologous enzyme sequences and experimentally validated functions, key functional residues are identified, and mutagenesis outcomes are predicted. Rational enzyme optimization builds small, focused mutant libraries are enriched with functionally improved variants and therefore substantially reduces the screening efforts for the identification of beneficial mutants.82

Directed evolution mimics the natural process of protein evolution by featuring iterative cycles of sequence diversification and mutant enzyme screening/characterization until the engineering goal is achieved (Figure 1B). Numerous methods that target local or global sequence randomization have been developed. 14, 80, 81 Error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling are two methods that were applied in the engineering of CARs and UPOs. Error-prone PCR introduces random nucleotide changes into a single gene template using low-fidelity DNA polymerases. DNA shuffling merges existing genes and creates new mutations by fragmentation and overlapping PCR to reassemble a collection of single-gene mutants or multiple related genes. Integrating multiple sequence diversification methods into a protein engineering project is proven to be a highly effective approach to generate beneficial mutations. In comparison to rational design, directed evolution has reduced or even no reliance on the target enzyme’s sequence-function and/or structure-function relationship. Without the constraints of prior knowledge, enzyme-directed evolution has profoundly expanded the repertoire of engineered biocatalysts with improved catalytic efficiencies, altered substrate, and cofactor specificities, and enhanced stability.10, 83

Combining rational design and directed evolution is a powerful approach in enzyme engineering that benefits from the available enzymology knowledge and explores large protein sequence space. The semi-rational design method relies on structural data and computational analyses to guide targeted random mutagenesis at sites that are predicted to impact catalysis. For example, active site residues can be subjected to saturation mutagenesis, randomizing their identities, while maintaining structural knowledge of the binding pocket.8 Additionally, lower-frequency random mutagenesis can be combined with site-saturation mutagenesis to raise the likelihood of integrating beneficial mutations at unpredictable loci alongside specified sites. Computational prescreening of designed mutants via molecular dynamics simulations or energy calculations also exemplifies semi-rational enzyme optimization.

For enzymes with multi-domain architectures, e.g., CARs, methods targeting the domain modularity have been developed to enhance or alter the natural properties.14 These tactics include generating chimeric enzymes with shuffled domain connectivity or truncating enzymes to remove unwanted domains. Domain manipulation is successfully applied to improve the catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, product selectivity, and thermostability of enzymes.

Besides serving as indispensable tools to improve the catalytic and physical properties of enzymes, protein engineering also contributes to fundamental studies of enzyme catalysis. Further investigation of the underlying mechanism(s) of altered performance led to valuable insights into catalytic mechanisms, structure-activity relationships, and the overall fitness landscape of numerous enzymes. Meanwhile, successful precedents have inspired the design of novel and more efficient enzyme engineering strategies.

4.2. Engineering of CARs

CARs have a broad substrate scope but often exhibit sub-optimal catalytic performance on less preferred substrates. Improving the reaction rate of a CAR is a common theme in the reported examples. One major obstacle in CAR engineering is its large protein size of over 110 kDa. Strategies to reduce library size and improve mutant screening/selection throughput significantly improve the efficiency of engineering efforts and lead to the facile identification of beneficial mutations.

4.2.1. Rational and semi-rational design

Structural data of the target enzyme often supports educated design rationales to achieve the engineering goal quickly. In the process to improve the poor activity of Mycobacterium abscessus CAR (MaCAR) towards succinic acid, Fedorchuk et al. studied the enzyme’s substrate binding pocket in the A-domain.84 They hypothesized that introducing bulky hydrophobic residues (Trp, Leu, and Phe) proximal to the distal end of the pocket could help reduce its size. Obtained variants L284W and T285W afforded a two-fold increase in activity towards succinic acid and decreased activity towards cinnamic acid. The mutations likely restrict the binding of aromatic substrates without hindering aliphatic dicarboxylates. Following a similar design, Hu et al. introduced bulky Trp substitutions into the A-domain of Mycobacterium marinum CAR (MmCAR) to restrict pocket size and tune the substrate specificity towards medium-chain fatty acids.40 When compared to the wild-type (wt) enzyme, variants Q302W and I303W afforded improved conversion rates of 37% and 61%, respectively. Given interests in the biocatalytic productions of industrial chemicals, Fedorchuk et al. applied structure-guided design to engineer CAR variants for a one-pot conversion of adipic acid into 6-aminocaproic acid and 1,6-hexanediamine in combination with transaminases.41 Crystallographic analysis selected 10 positions in the substrate binding pocket for site-directed mutagenesis in order to improve activity towards 6-aminocaproic acid. Screening assays revealed four mutants, L342E, L342Q, G418E, and G426W, showed increased activity. The best mutant, L342E, exhibited a 10-fold activity increase. The results suggest that the presence of ionic and/or hydrogen bond interaction facilitates the binding of 6-aminocaproic acid. When the L342E variant was used in the one-pot synthesis, up to 70% conversion of adipic acid to 6-aminocaproic acid and 30% conversion to1,6-hexanediamine were obtained.

Wang et al. seek to identify a general strategy to improve the catalytic rate of CAR enzymes. Based on the sequence alignments between CARs and other members of the ANL superfamily, the authors focused on a “hinge region” that potentially elicited conformational change in the catalysis process.36 In CAR proteins, this region consists of conserved amino acid sequence Asp-Arg-Arg-Asn (DRRN), whereas in other superfamily members, the conserved sequence is Asp-Arg-Lys-Lys (DRKK). Positions Arg505 and Asn506 in Mycobacterium smegmatis CAR (MsCAR) were therefore selected for mutagenesis studies. Among the panel of mutants screened at position 505, R505E, R505I, R505M, and R505Q displayed improved substrate binding affinity and increased activity. Meanwhile, a N506K mutant also showed enhanced catalytic turnover. When examining possible synergistic effects, the best mutant R505I/N506K showed around 6.5-fold improved catalytic efficiency over the wt enzyme. It was more active than either one of the single-site mutants. In order to investigate the mechanistic reasons for this change, the authors employed a virtual mutation strategy by applying a key distance-based metric (d1) as the descriptor to evaluate mutagenesis effect using molecular dynamics simulations. The efforts yielded eight additional mutants with higher activity than the wt and mutant R505F/N506G is the most active one. This research demonstrated the power of combining wet-lab and in silico screening for efficient engineering of CARs.

Structure-guided mutagenesis has also provided detailed understanding of the structure-function relationships and catalytic mechanisms of CAR enzymes. Gahloth et al. conducted the pioneering crystallographic study of CARs.28 To further elucidate the mechanistic details of the reduction step in Segniliparus rugosus CAR (SrCAR) catalysis, site-directed mutagenesis was performed at an Asp998 residue in the R-domain.28 When compared to the wt enzyme, a D998G variant showed modest but robust benzaldehyde reduction activity, which implicated that this residue played a critical role in maintaining the 2-electron reductase function. Comparing the apo and the holo forms of the D998G variants showed higher benzaldehyde reduction activity with the non-phosphopantetheinylated apo enzyme, suggesting the post-translational modification (PTM) inhibited the benzaldehyde reduction potentially through restricting its binding into the active site. The importance of the substrate phosphopantetheine was further established by mutating residues that provide interactions between the phosphopantetheine group and the R-domain. All the resulting mutants abolished activity. Meanwhile, the activity of a S702A mutant, which lost the serine residue subjected to the PTM, could be restored by the external addition of (R)-pantetheine. The results indicated that free pantetheine groups can bypass the lack of endogenous modification and participate in the catalytic cycle in the A-domain. Furthermore, the R-domain recognized benzoyl-pantetheine thioester as the substrate regardless of the lack of covalent linkage. Both conclusions have profound implications on the substrate binding mode in the active sites of CARs and laid the foundation for the engineering of individual CAR domains as standalone enzymes. Facilitated by computational modeling, Qu et al. also attempted to investigate the roles of key residues in the substrate binding pocket relating to the adenylation and thiolation events in SrCAR.85 Molecular dynamic simulation indicated two lysine residues, Lys629 and Lys 528, alternately acted as hydrogen bond donor during the adenylation and thiolation step. Substitution with alanine residues at each position abolished activity toward benzoic acid. Although above research does not have an engineering focus, obtained knowledge from structure-guided mutagenesis provided guidance for future engineering efforts.

Instead of introducing one specific amino acid, site-saturation mutagenesis thoroughly explores the effect of all 20 proteinogenic amino acids at the designated position on the property change of the target enzyme by providing a comprehensive sequence, structure, and function coverage. In their efforts to redesign SrCAR for enhanced benzoic acid reduction, Qu et al. selected 17 active site residues for site-saturation mutagenesis based on a molecular dynamics simulation study.86 Screening the library led to variants K524W and A937V, which achieved the highest activity enhancements for residues in the A-domain and R-domain, respectively. combining the two mutations led to the best mutant, K524W/A937V. To understand how these positions affect the catalytic activity, MD simulations were performed on the wt and the K524W variant. It was shown that the Lys residue engages in hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl oxygen atoms of the ribose scaffold of ATP. The authors hypothesized that the hydrogen bond may hinder the release of the AMP byproduct and replacing Lys with a hydrophobic Trp residue eliminated the H bond formation and led to faster turnover. The hypothesis was verified with a K524R mutant, which showed lower activity than the wt enzyme. Capitalizing on the engineered improvement, the K524W mutant was applied to a high-yield lactam production through the cyclization of ε-amino acid in a separate study.48 Compared with the wt enzyme, K524W showed ~96% conversion of amino acids into the corresponding lactam products. The results indicated that mutations in the cofactor binding pocket of CAR can afford a general improvement of the catalytic efficiency which is independent of the substrate structure. In another example, Hu et al. successfully pursued a site-saturation mutagenesis strategy to generate mutant CARs for the direct production of medium-chain fatty alcohols from fatty acids.40 Studies by Gahloth et al. have demonstrated that residues 983-985 in SrCAR adopted restricted conformation to prevent the further reduction of aldehyde product into alcohol.28 Hu et al. generated site-saturation mutant libraries by targeting the equivalent positions in MmCAR. One variant RF1 (C983P/D984H/M985L) was identified with a 2.4-fold enhancement for fatty alcohol production in comparison to that of the wt enzyme. The improved levels of desired fatty alcohol products highlight the utility of tailoring enzyme scaffold regions beyond the core catalytic region to optimize catalytic function.

Even though site-saturation mutagenesis has proven to be an exceptional tool in enzyme engineering, the relatively large library size, particularly when multiple sites are targeted, complicates the mutant screening efforts. To expedite the mutant identification process in CAR engineering, Kramer et al. devised a whole-cell NADPH recycling approach to enable a growth-coupled selection scheme.87 It used an Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain R-Δ2, which overaccumulated NADPH in glucose media due to the deletion of pgi and sthA genes (Figure 4A). The growth defect of R-Δ2 can be rescued when a NADPH-consuming enzyme, such as CAR, is introduced. Inspecting a homology model of the A-domain of Mycobacterium avium CAR (MavCAR) in complex with benzoate substrate, 10 residues lining the active site were identified for site-saturation mutagenesis using the NNK degenerate codons (Figure 4B). Obtained libraries were subjected to the growth-coupled selection for improved activities towards several substrates, including 2-methoxybenzoate and adipate. Selection with 2-methoxybenzoate as the substrate revealed 5 key residues in MavCAR, N276, M296, S299, N335, M389, which led to mutants with increased catalytic efficiency (Figure 4C). The best mutant, N335W, showed ~4.5-fold improvement. When using adipate as the selection substrate, the best mutant, N335R had an over 17-fold higher catalytic efficiency than the wt enzyme (Figure 4C). The improved kinetic performance was also translated to higher product formation when the mutant was employed in a whole-cell conversion from adipate to 1,6-hexanediol. This growth-coupled selection method can also be applied to the selection of mutant libraries that are generated in directed evolution experiments, which are expected to cover more sequence variants. In comparison to screening methods that rely on robotics system, the growth-coupled selection has higher throughput and is less resource- and labor-intensive.

Figure 4.

Growth-coupled NADPH recycling selection strategy. (A) Schematics of the selection design. (B) Homology model of the MavCAR active site. Catalytic His294 (red), position chosen for saturation mutagenesis (black). (C) Kinetic parameters of CAR variants.

4.2.2. Directed evolution

The iterative nature of a directed evolution experiment enhances the sequence coverage and improves the chance to overcome local energy minimal in order to obtain variants with optimal properties. Seeking to improve the catalytic profile of Nocardia iowensis CAR (NiCAR), Schwendenwein et al. performed directed evolution facilitated by a high-throughput screening assay that was based on amino benzamidoxime (ABAO)-enabled detection of aldehyde formation.88 Error-prone PCR was initially applied to generate libraries with randomized A-domain and R-domain, respectively. After screening 4500 clones of the A-domain and 1500 clones of the R-domain against 2-methoxybenzoate as the substrate, the variant Q283R was identified for the highest activity with a five-fold lower Km value when compared to that of the wt. The position was then subjected to site-saturation mutagenesis. The best hit, Q283P, led to a ~65% conversion of 2-methoxybenzoic acid to the corresponding aldehyde. In a whole-cell biotransformation, this variant showed 9-fold higher aldehyde yield. MD simulation indicated that position 283 could affect the substrate binding. In a separate study, Liu et al. showed that the same NiCAR Q283P mutant afforded the highest conversion of palmitic acid to its aldehyde (>40%).39

Hu et al. also applied random mutagenesis to improve the catalytic activity of MmCAR towards medium-chain fatty acids.40 To facilitate the efforts, a growth-coupled screening method was established in an yeast strain with POX1 and HFD1 deletion, which further sensitized the cells to the toxicity of medium-chain fatty acids. Expression of CAR enzyme had a detoxification effect and led to improved cell fitness. A full-length MmCAR library was generated by error-prone PCR and subjected to growth screening. The best mutant obtained, M150, contained three mutations, D241E, H454R, and L567M, with two in the A-domain and one between the A- and the PCP-domain. It led to an over 50% improvement (129 mg/L) in the production of medium-chain fatty alcohol compared to the wt MmCAR. Using M150 as the template, a second round of mutagenesis and screening was conducted. Although none of the three obtained mutants performed better than M150, two of them still afforded higher conversion than the wt enzyme. The authors further leveraged the power of combining random mutagenesis and rational design to improve enzyme properties. By combining a M150 with an I303W mutation, which was selected based on literature precedent, led to a further improved conversion (~175 mg/L). The results show that the ability to combine predictive rational design with evolution-selected mutations empowered the development of enhanced CAR mutants, highlighting the potential of combinatorial enzyme engineering beyond a single technique alone.

4.2.3. Domain manipulation

Domain swapping and fusion methods have been successfully applied to the mechanistic study and engineering of multi-domain enzymes. Gahloth et al. first demonstrated the feasibility of generating hybrid CARs through domain exchange between parent enzymes. The authors successfully built functional chimeric enzymes by exchanging the adenylation domain between MmCAR and NiCAR.28 Kramer et al. subsequently undertook sequence alignment and structural analyses to guide the construction of hybrid CARs from four bacterial and one fungal enzyme.89 All the hybrid CARs were functional, albeit lower activities were observed in bacterial-fungal hybrids. Activity analysis revealed that chimeric enzymes harboring the natural PCP and R di-domain were more active than other combinations. Further mutagenesis studies targeting the interacting interface between the A-domain and the PCP-domain in hybrid CARs indicated that inter-domain interactions play an important role in the function of CAR enzymes. In another attempt by Hu et al. to engineer the direct reduction of medium-chain fatty acids into alcohols, chimeric enzymes were constructed by replacing the PCP-R di-domain or the R-domain of MmCAR with the corresponding domains from three non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) enzymes.40 Unfortunately, none of the chimeras was functional. The authors hypothesized that introducing foreign domain(s) might cause misfolding of the hybrid protein. The PCP-R di-domain was then supplemented to the full-length MmCAR as either separately expressed protein or C-terminal fusion using a flexible peptide linker GGGGS. Five out of six constructs led to the successful synthesis of fatty alcohols.

The creation of functional chimeric enzymes fully demonstrates the domain modularity of CARs and encourages enzyme truncation efforts to engineer individual CAR domains as standalone enzymes. When examining amide formation reactions catalyzed by CARs, Wood et al. developed a truncated MmCAR (Δ729-1175) containing only the A-domain.49 This mutant retained the adenylation activity but lacked reduction capacity. In the presence of a carboxylic acid and an amine, this mutant produced the amide compound ilepcimide with a 69% yield. Further truncation guided by structural data generated MmCARΔ647–1175 (MmCAR-A).45 This mutant remained active and showed a higher rate of amide formation than the full-length enzyme. MmCAR-A was further applied to the monoacylation of diamines, for which a relaxed substrate specificity of piperazine analogs and linear diamines was observed. In the presence of a polyphosphate kinase from Cytophaga hutchinsonii (CHU) for in situ ATP recycling, the truncated enzyme led to the synthesis of pharmaceutical precursors and active pharmaceutical ingredient, including a monoamine oxidase B inhibitor lazabemide, at 50-100 mL scale with 9-44% isolation yield.45 Furthermore, the utility of MmCAR-A was demonstrated in the successful synthesis of N-alkanoyl-N-methylglucamide (MEGA) surfactants through amidation.46 The commercial surfactant MEGA-8 was obtained with ATP recycling in 94% and 42% yields at small and 30 mL scale, respectively. Other MEGA surfactants from octanoic (C7), nonanoic (C8), decanoic (C9), and dodecanoic acid (C10) were also obtained with decent yields. In a recent report, the MmCAR-A was expressed as secreted protein by Komagataella phaffii and successfully applied to the synthesis of N-hexylbenzamide from benzoic acid and hexylamine.90

Following the same design principle, a truncated SrCAR containing only the A-domain (SrCAR-A) (Δ6589-1188) was constructed by Schnepel et al to catalyze the thioester formation.47 SrCAR-A maintained the broad substrate specificity of the full-length enzyme and was capable of using thiols including CoA-SH, pantetheine, and N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC). The acyl-S-CoA synthetase activity was further employed to regenerate acyl-CoA from CoA-SH and carboxylic acid in N-acyltransferase-catalyzed synthesis of amide. In one example, SrCAR-A was coupled with a lysine acetyltransferase p300 to achieve the acetylation of histone H4 peptide. Successful completion of the reaction was confirmed using [2H3]-acetate substrate, which was incorporated to the H4 peptide based on mass spectrometry analysis. Above examples demonstrated that the truncated A-domain of CARs catalyzes the formation of activated acyl-AMP, which can react with various nucleophiles to afford a diverse group of products.

Besides the A-domain, recent efforts were also directed to the engineering of the R-domain of CAR for biocatalytic applications. Daniel et al generated a truncated fungal CAR from Neurospora crassa that contained only the R-domain (NcCAR-R, Δ1–649).51 It was hypothesized that NcCAR-R was capable of catalyzing the reduction of thioesters to the corresponding aldehydes. To the authors’ delight, NcCAR-R was active toward N-acetylcysteamine thioester, affording a 43% conversion to its aldehyde product. The result showed initial evidence that the standalone R domain can reduce thioester substrates if phosphopantetheine mimicking moiety is attached. Furthermore, given the structural similarity between NcCAR R-domain and short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase, NcCAR-R was examined on ketone and aldehyde substrates. Interestingly, it reduced acetophenone at 73% conversion and benzaldehyde at 32% conversion. The second reactivity is more significant, because benzaldehyde is taken as the end product in the full-length NcCAR-catalyzed reduction of benzoic acid. These results showed that the standalone NcCAR-R domain can perform new chemistry that is distinctively different from the full-length protein.

4.2.4. Other approach

Thomas et al. employed ancestral sequence reconstruction to engineer thermostable CARs with enhanced tolerance against salt, solvents, and pH.91 The authors applied three marginal reconstruction algorithms with optimized likelihood scores to produce four ancestral CARs (AncCAR). All AncCARs retained 50% activity following incubation at temperatures higher than 65 °C. Among them, one variant derived from the Ancescon algorithm was the most thermostable CAR reported at the time. Moreover, the AncCAR-PF variants, which were derived from the PAML algorithm with gaps reconstructed by cross mapping from the FastML algorithm, showed high halotolerance at elevated temperatures and retained 50% activity in the presence of over 25% methanol. Meanwhile, all AncCARs retained 100% activity between pH 6.0 and 9.0, while two variants did not lose activity up to pH 10.0. The development of thermostable enzymes is an essential starting point for the industrial-scale applications. Liu et al. used these AncCARs for high-yield conversion of fatty acids into aldehydes in a cell-free system.39 After the biotransformation, 97% conversion to the product hexadecanal was obtained. These results show that the excellent stability of AncCARs makes them promising candidates for the biocatalytic productions of valuable chemicals.

4.3. Engineering of UPOs

UPOs have attracted great interests due to the ability to catalyze the oxyfunctionalization of non-activated C-H, C-C, and C=C bonds within diverse structural contexts by simply using H2O2 as the co-substrate without the need of extra coupling proteins and cofactor. These self-sufficient enzymes also exhibit excellent in vitro stability and afford large total turnover numbers (TONs). Meanwhile, applications of UPOs do suffer from several drawbacks, including the generally low levels of functional heterologous expression, the existence of undesired peroxidase activity, the oxidative inactivation by H2O2, possible product overoxidation, and sometimes low selectivity. Protein engineering efforts have been devoted to solving these issues and achieved success to different extents. For example, since the first demonstration of heterologous expression of a Coprinopsis cinerea UPO in Aspergillus oryzae,92 functional production of UPOs in other platform hosts, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris (P. pastoris), and E. coli, have been reported in peer-reviewed literature and patents.56 Key limiting factors such as leader signals for efficient secretion, heme incorporation, and post-translational modification including glycosylation are identified.56, 61 Titers higher than 200 mg/L have been reported in P. pastoris host under fed-batch fermentation conditions.93, 94 Besides cost-effective bioproduction of UPOs, successful heterologous expression in platform host strains also enabled enzyme discovery and engineering efforts due to readily available toolsets. Modifications of the heme channel were shown to be an effective approach to reduce the peroxidase activities in long UPOs.95, 96 To reduce the inactivation caused by H2O2 co-substrate, enzymatic,97, 98 electrochemical,99 and photocatalytic100 strategies have been developed for efficient in situ H2O2 delivery. Furthermore, the development of high-throughput screening assays led to successful directed evolution campaigns to improve the chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity of UPOs.95, 101-104 And the application of computational tools, such as FuncLib, has facilitated the design of functional enzyme variants for optimization.104, 105 Several excellent reviews provide comprehensive coverage on the engineering of UPOs for biotechnological applications.52, 55-64 Here, we will focus on a few recent examples that have not been covered.

The simplicity of co-substrate requirement motivates the biocatalytic applications of UPOs, but also presents a reaction engineering challenge in order to minimize oxidative inactivation by H2O2 while still maintains the enzyme’s optimal reaction rate. In situ delivery of H2O2 through photocatalytic approach has been explored as a viable solution. Inorganic catalysts, e.g., Au-TiO2106 and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4),107 and organic small molecules, e.g., flavin adenine mononucleotide (FMN),100 NADH/dye molecule,108 anthraquinone sulfonate (SAS),109 have been demonstrated to support UPO reactions under photo irradiation conditions. Püllmann and coworkers took a novel enzymatic approach for in situ H2O2 generation by directly fusing UPOs with hydrogen peroxide-producing bacterial flavin binding fluorescent proteins (FbFPs) as photosensitizers.110 Building upon a previously reported design for the functional expression of UPO fusion proteins,98 the authors generated and screened a protein variant library that contained permutations of different signal peptides, UPOs, linkers, and FbFP sequences. Two functional proteins, PhotUPO-I and PhotUPO-II, which contained Psathyrella aberdarensis UPO I or II (PabUPO I or II) and a Dinoroseobacter shibae FbFP, were identified based on a colorimetric 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (DMP) assay. Further functional testing showed that both enzymes displayed similar trends of activities in the presence of 17 sacrificial electron donors and the activities were only observed with the fusion protein but not with either the UPO or the FbFP component. Meanwhile, inclusion of superoxide dismutase or catalase led to increased or decreased reaction rate, which confirmed the formation of H2O2 as the co-substrate in UPO-catalyzed reaction. The stability of the two enzymes were examined under different irradiation condition with varied excitation wavelength and duration. PhotUPO-I was shown to be a more stable enzyme. It sustained high linear reaction rate for over 90 min, which was 40 min longer than PhotUPO-II. Interestingly, the PabUPO II portion of the PhotUPO-II fusion enzyme exhibited similar stability as PabUPO I in PhotUPO-I. It was hypothesized that the fusion conditions might contribute to the reduced stability. PhotUPO-I and II displayed different substrate scope and varied, sometimes opposite, enantioselectivity. Under optimized condition, PhotUPO-I catalyzed the sulfoxidation of methyl phenyl sulfide up to 24300 TON. The utility of the two enzymes were further demonstrated in scaled-up hydroxylation and sulfoxidation reactions. Complete or near complete conversion was observed for all reactions. Following prolonged irradiation, overoxidation was observed, which can be minimized by controlling the reaction time. Meanwhile, the observation also indicated that the PhotUPO enzymes were stable for 11-14 h under the preparative conditions.

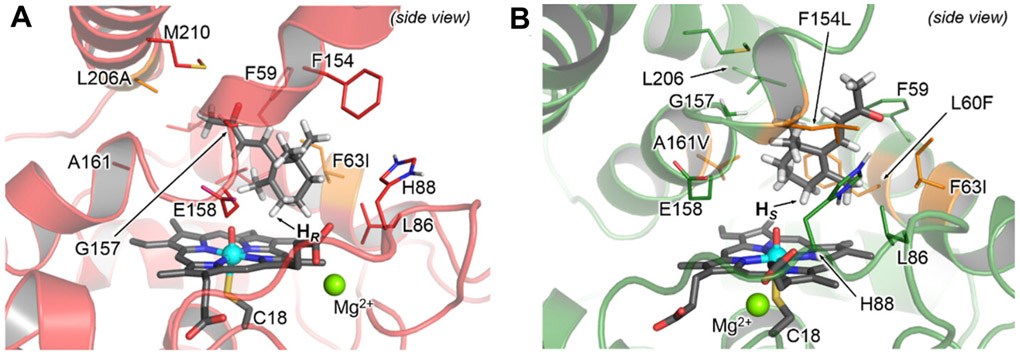

The enantioselectivity engineering of UPOs is a relatively less explored topic albeit its importance. In a recent study, Münch and coworkers reported the target-oriented engineering of a Myceliophthora thermophila (MthUPO) for enantioselective hydroxylation at the C4 position of β-ionone to produce 4-hydroxy β-ionone through directed evolution.111 Early screening efforts have shown that UPOs led to a diverse range of hydroxylation and epoxidation products with β-ionone substrate.76 The authors therefore started with MthUPO F63I, which showed an 88% regioselectivity towards the hydroxylation at C4 position and 4.5-fold higher product formation than the wt enzyme. A computational approach combining Density Function Theory (DFT) calculation and MD simulation was taken to assist with smart library design. A truncated model, which included the heme pyrrole core, a methyl thiolate to mimic the cysteine axial ligation, and the β-ionone substrate was applied in the DFT calculation. The model was validated by comparing computational predictions and experimental observations of the enzyme’s catalytic behavior. A restrained-MD simulation was then performed to identify residues for mutagenesis. To this end, the substrate was forced to explore a near-attack conformation for effective C4 hydroxylation while mimicking the geometry of transition states in the DFT calculation. Meanwhile, either the pro-R or the pro-S C4-H position was tethered close to CpdI in order to sample the two opposite enantioselectivities. The authors further hypothesized that mutating active site residues that exhibited strong steric interactions with the substrate better accommodated the substrate in desirable reactive conformations and destabilized alternate conformations that might result in diminished regio- and enantioselectivity. Eight residues were therefore selected for paired mutagenesis in order to explore potential cooperative effects. Libraries of 10 pairs were constructed based on a reduced amino acid alphabet to maintain a hydrophobic active site. Library screening relied on a previously reported multiple injection in a single experimental run (MISER) GC-MS scheme,112 which processed one 96-well plate in 48 min. Screening over 900 variants of the double mutation pairs led to the best variant R1A (F63I, L206A) with 2.0-fold higher activity and a TON of 28,000. Interestingly, without specific screening for enantioselectivity, this mutant displayed an enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) of 96.6:3.4, which is a significant improvement from the e.r. of the wt, 70.7:29.3. The result again demonstrated that an increased activity simultaneously affects the enantioselectivity of an enzyme. Above screening also identified mutants with reversed enantioselectivity. The best one R1B (F63I, L60F, A161V) had an e.r. of 3.3:96.7. The second round of evolution started from R1A and R1B as the parents and mutation sites were selected based on results from unrestrained MD simulations. No mutant with improved e.r. over R1A was identified, but a mutant R2B (F63I, L60F, A161V, F154L), which exhibited 2.0-fold higher activity than R1B, an e.r. of 99.7:0.3, and a TON of 41,000, was isolated. Further computational modeling provided insights into the molecular basis of the excellent enantioselectivity of R1A and R2B. For R1A, introducing the L206A mutation expanded the binding pocket to accommodate the α,β-unsaturated ketone chain, therefore enabled the placement of the pro-R C4-H in a favored position for the hydroxylation (Figure 5A). On the other hand, introduction of the A161V mutation into the same region reduced the binding pocket and forced the allylic ketone chain to point outwards. The altered orientation fitted into additional space created by the F154L mutation. As a result, C4-H was predisposed in a pro-S position (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

β-Ionone-binding modes characterized from MD simulations. (A) variant R1A (F63I/L206A, in red). (B) variant R2B (L60F/F63I/F154L/A161V, in green)111.

A robust high-throughput assay is the prerequisite for large-scale enzyme discovery and/or engineering campaign. Such design is particularly challenging when the enantioselectivity is the engineering target because often more complicate schemes are required to determine the products’ enantiomeric composition. The Kroutil lab recently reported an enzymatic approach for the facile estimation of the enantioselectivity, stereopreference, and activities of UPOs.113 The spectrophotometric assay was based on cascade reactions of UPOs and two highly stereospecific alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs), which catalyzed the oxidation of UPO reaction products, sec-alcohols, with concomitant NAD(P)H formation. One ADH was (R)-selective, i.e., Lacobacillus kefir (LkADH), and the other was (S)-selective, i.e., Rhodococcus ruber DSM44541 (ADH-A). By comparing the differences in fluorescence signal increase from NAD(P)H in the two parallel reactions, the ee value and the quantity of the products were inferred. Initial assay development showed that more robust and reliable results of enantiomeric excess (ee) determination were obtained when the fluorescence intensity at the endpoints rather than the initial rates of ADH reactions were used. Furthermore, maintaining a relatively low concentration of H2O2 at 200 μM was critical for maintaining the proper function of the coupling enzymes and the stability of NAD(P)H. A limit of quantification (LoQ) of 7.5 μM was reported for the assay. The assay was easily adapted to high-throughput format and applied to examine the enantioselectivity of 44 UPOs with 25 previously uncharacterized. Comparison of results from the assay and GC analysis showed an average deviation of ±11% (n = 25) in ee and a mean absolute error of 16% with the substrate conversion analysis. The major factor that caused the analytical error was attributed to possible overoxidation by UPOs. Besides benzylethane substrate in the proof-of-concept study, the assay was also successfully applied to UPO-catalyzed reactions of aliphatic substrate, e.g., n-octane, and fatty acid, e.g., n-octanoic acid. Using this assay, the authors successfully identified UPOs that catalyzed stereocomplementary reactions.

5. Conclusion and Future perspectives

The flavor and fragrance industry continues to expand rapidly. However, conventional chemical synthesis methods face increasing backlash due to environmental and human health concerns. In response, there is a shift towards safer, more sustainable biotechnological production strategies using enzymes. Well-known enzymes like lipases, proteases, alcohol dehydrogenases, and cytochrome P450s can catalyze numerous biosynthetic reactions with improved affordability and safety in comparison to traditional techniques. However, recently discovered enzymes like CARs and UPOs provide unique capabilities but are less studied. Both groups of enzymes have broad substrate scopes and perform chemistries that are challenging to chemical method. CARs are capable of direct reduction of carboxylic acids into the corresponding aldehydes without the need for a second enzyme for substrate activation. Their modular structural architecture further expands the repertoire of products to amide/lactam, ester/lactone, thioester, and alcohol through reactions catalyzed by individual domains. UPOs are self-sufficient mono peroxygenases that catalyze similar reactions as P450 enzymes but are easier to manipulate. Both enzymes have been employed for the synthesis of flavor and/or fragrance molecules. Their unique catalytic power would significantly expand the scope of these compounds that can be enzymatically produced. Despite their potential, industrial applications of CARs and UPOs remain elusive. In this review, we have presented enzyme engineering examples to demonstrate the possibility to alter and/or improve the catalytic performance, the selectivity, and the stability of these enzymes. The achievements are stepping stones towards the ultimate industrial synthesis using these enzymes. Furthermore, the engineering methods, strategies, and outcomes discussed here serve as excellent examples for future endeavors with these or other types of enzymes. Particularly, combining computational modeling and high-throughput screening has led to rapid success. Looking forward, the growing trend of integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning to protein engineering is expected to unleash the full potential of enzyme catalysis. We expect that protein engineering efforts will enable a rapid access to a greater selection of industrial-grade enzymes, which are the key to design new and/or improve current biosynthetic routes to meet the demand of the flavor and fragrance industry.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant 1805528 to W.N. and J.G.) and NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01GM147785 (to J.G. and W.N.), R35GM149322 (to J.G.), and P20GM113126 (to J.G. and W.N.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.K R R; Gopi S; Balakrishnan P, Introduction to Flavor and Fragrance in Food Processing. In Flavors and Fragrances in Food Processing: Preparation and Characterization Methods, American Chemical Society: 2022; Vol. 1433, pp 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger P; Plainfossé H; Brochet X; Chemat F; Fernandez X, Extraction of Natural Fragrance Ingredients: History Overview and Future Trends. Chem. Biodivers 2019, 16 (10), e1900424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga A; Guerreiro C; Belo I, Generation of Flavors and Fragrances Through Biotransformation and De Novo Synthesis. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2018, 11 (12), 2217–2228. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang H; Wang X, Biosynthesis of monoterpenoid and sesquiterpenoid as natural flavors and fragrances. Biotechnol. Adv 2023, 65, 108151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulino BN; Sales A; Felipe L; Pastore GM; Molina G; Bicas JL, Recent advances in the microbial and enzymatic production of aroma compounds. Curr. Opin. Food Sci 2021, 37, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik T; Rawat S, Biotechnological Interventions for Production of Flavour and Fragrance Compounds. In Sustainable Bioeconomy : Pathways to Sustainable Development Goals, Venkatramanan V; Shah S; Prasad R, Eds. Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp 131–170. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heckmann CM; Paradisi F, Looking Back: A Short History of the Discovery of Enzymes and How They Became Powerful Chemical Tools. ChemCatChem 2020, 12 (24), 6082–6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali M; Ishqi HM; Husain Q, Enzyme engineering: Reshaping the biocatalytic functions. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2020, 117 (6), 1877–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu S; Snajdrova R; Moore JC; Baldenius K; Bornscheuer UT, Biocatalysis: Enzymatic Synthesis for Industrial Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60 (1), 88–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold FH, Directed Evolution: Bringing New Chemistry to Life. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57 (16), 4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilvert D., Design of protein catalysts. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2013, 82, 447–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reetz M, Making Enzymes Suitable for Organic Chemistry by Rational Protein Design. ChemBioChem 2022, 23 (14), e202200049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SÁ AGA; Meneses A. C. d.; Araújo P. H. H. d.; Oliveira D. d., A review on enzymatic synthesis of aromatic esters used as flavor ingredients for food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol 2017, 69, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A; Gupta G; Ahmad T; Mansoor S; Kaur B, Enzyme Engineering: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Food Rev. Int 2021, 37 (2), 121–154. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribeaucourt D; Bissaro B; Lambert F; Lafond M; Berrin J-G, Biocatalytic oxidation of fatty alcohols into aldehydes for the flavors and fragrances industry. Biotechnol. Adv 2022, 56, 107787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armanino N; Charpentier J; Flachsmann F; Goeke A; Liniger M; Kraft P, What's Hot, What's Not: The Trends of the Past 20 Years in the Chemistry of Odorants. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59 (38), 16310–16344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Z; Huang B; Ouyang L; Zheng L, Synthesis of Cyclic Fragrances via Transformations of Alkenes, Alkynes and Enynes: Strategies and Recent Progress. Molecules 2022, 27 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X; Zhang Y; Cheng Y; Sun H; Bai S; Li C, Identifying environmental hotspots and improvement strategies of vanillin production with life cycle assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 769, 144771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poornima K; Preetha R, Biosynthesis of Food Flavours and Fragrances - A Review. Asian J. Chem 2017, 29 (11), 2345–2352. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michailidou F, The Scent of Change: Sustainable Fragrances Through Industrial Biotechnology. ChemBioChem 2023, 24 (19), e202300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shukla A; Girdhar M; Mohan A, Applications of Microbial Enzymes in the Food Industry. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong W; Qi Y; Ji L; Zhang Z; Lu Z; Nian B; Hu Y, Computer-Aided Tunnel Engineering: A Promising Strategy for Improving Lipase Applications in Esterification Reactions. ACS Catal. 2024, 14 (1), 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartsch S; Brummund J; Koepke S; Straatman H; Vogel A; Schuermann M, Optimization of Alcohol Dehydrogenase for Industrial Scale Oxidation of Lactols. Biotechnol. J 2020, 15 (11), 2000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamo J; Assefa F, The role of microbial aspartic protease enzyme in food and beverage industries. J. Food Qual 2018, 7957269/1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gimenes NC; Silveira E; Tambourgi EB, An Overview of Proteases: Production, Downstream Processes and Industrial Applications. Sep. Purif. Rev 2021, 50 (3), 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kale P; Mishra A; Annapure US, Development of vegan meat flavour: A review on sources and techniques. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100149. [Google Scholar]

- 27.He A; Li T; Daniels L; Fotheringham I; Rosazza JPN, Nocardia sp. carboxylic acid reductase: cloning, expression, and characterization of a new aldehyde oxidoreductase family. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2004, 70 (3), 1874–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gahloth D; Dunstan MS; Quaglia D; Klumbys E; Lockhart-Cairns MP; Hill AM; Derrington SR; Scrutton NS; Turner NJ; Leys D, Structures of carboxylic acid reductase reveal domain dynamics underlying catalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13 (9), 975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winkler M., Carboxylic acid reductase enzymes (CARs). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 43, 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basri RS; Rahman RNZRA; Kamarudin NHA; Ali MSM, Carboxylic acid reductases: Structure, catalytic requirements, and applications in biotechnology. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2023, 240, 124526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finnigan W; Thomas A; Cromar H; Gough B; Snajdrova R; Adams JP; Littlechild JA; Harmer NJ, Characterization of Carboxylic Acid Reductases as Enzymes in the Toolbox for Synthetic Chemistry. ChemCatChem 2017, 9 (6), 1005–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkitasubramanian P; Daniels L; Rosazza JPN, Biocatalytic reduction of carboxylic acids: mechanism and applications. In Biocatalysis in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, Patel RN, Ed. CRC Press LLC: 2007; pp 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gahloth D; Aleku GA; Leys D, Carboxylic acid reductase: Structure and mechanism. J. Biotechnol 2020, 307, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venkitasubramanian P; Daniels L; Rosazza JPN, Reduction of carboxylic acids by Nocardia aldehyde oxidoreductase requires a phosphopantetheinylated enzyme. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282 (1), 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J; Lee H-S; Oh J; Joo JC; Yeon YJ, A highly active carboxylic acid reductase from Mycobacterium abscessus for biocatalytic reduction of vanillic acid to vanillin. Biochem. Eng. J 2020, 161, 107683. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L; Sun Y; Diao S; Jiang S; Wang H; Wei D, Rational hinge engineering of carboxylic acid reductase from Mycobacterium smegmatis enhances its catalytic efficiency in biocatalysis. Biotechnol. J 2022, 17 (2), 2100441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akhtar MK; Turner NJ; Jones PR, Carboxylic acid reductase is a versatile enzyme for the conversion of fatty acids into fuels and chemical commodities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110 (1), 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer L; Hankore ED; Liu Y; Liu K; Jimenez E; Guo J; Niu W, Characterization of Carboxylic Acid Reductases for Biocatalytic Synthesis of Industrial Chemicals. ChemBioChem 2018, 19 (13), 1452–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y; Liu W-Q; Huang S; Xu H; Lu H; Wu C; Li J, Cell-free metabolic engineering enables selective biotransformation of fatty acids to value-added chemicals. Metab. Eng. Commun 2023, 16, e00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Y; Zhu Z; Gradischnig D; Winkler M; Nielsen J; Siewers V, Engineering carboxylic acid reductase for selective synthesis of medium-chain fatty alcohols in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117 (37), 22974–22983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fedorchuk TP; Khusnutdinova AN; Evdokimova E; Flick R; Di Leo R; Stogios P; Savchenko A; Yakunin AF, One-Pot Biocatalytic Transformation of Adipic Acid to 6-Aminocaproic Acid and 1,6-Hexamethylenediamine Using Carboxylic Acid Reductases and Transaminases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (2), 1038–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strohmeier GA; Eiteljorg IC; Schwarz A; Winkler M, Enzymatic One-Step Reduction of Carboxylates to Aldehydes with Cell-Free Regeneration of ATP and NADPH. Chemistry – A European Journal 2019, 25 (24), 6119–6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Megarity CF; Weald TRI; Heath RS; Turner NJ; Armstrong FA, A Nanoconfined Four-Enzyme Cascade Simultaneously Driven by Electrical and Chemical Energy, with Built-in Rapid, Confocal Recycling of nAdP(H) and ATP. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (15), 8811–8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Napora-Wijata K; Robins K; Osorio-Lozada A; Winkler M, Whole-Cell Carboxylate Reduction for the Synthesis of 3-Hydroxytyrosol. ChemCatChem 2014, 6 (4), 1089–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lubberink M; Schnepel C; Citoler J; Derrington SR; Finnigan W; Hayes MA; Turner NJ; Flitsch SL, Biocatalytic Monoacylation of Symmetrical Diamines and Its Application to the Synthesis of Pharmaceutically Relevant Amides. ACS Catalysis 2020, 10 (17), 10005–10009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lubberink M; Finnigan W; Schnepel C; Baldwin CR; Turner NJ; Flitsch SL, One-Step Biocatalytic Synthesis of Sustainable Surfactants by Selective Amide Bond Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, 61 (30), e202205054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnepel C; Perez LR; Yu Y; Angelastro A; Heath RS; Lubberink M; Falcioni F; Mulholland K; Hayes MA; Turner NJ; Flitsch SL, Thioester-mediated biocatalytic amide bond synthesis with in situ thiol recycling. Nat. Catal 2023, 6 (1), 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin Z; Zhang X; Sang X; Zhang W; Qu G; Sun Z, Carboxylic acid reductases enable intramolecular lactamization reactions. Green Synthesis and Catalysis 2022, 3 (3), 294–297. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wood AJL; Weise NJ; Frampton JD; Dunstan MS; Hollas MA; Derrington SR; Lloyd RC; Quaglia D; Parmeggiani F; Leys D; Turner NJ; Flitsch SL, Adenylation Activity of Carboxylic Acid Reductases Enables the Synthesis of Amides. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed 2017, 56 (46), 14498–14501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pongpamorn P; Kiattisewee C; Kittipanukul N; Jaroensuk J; Trisrivirat D; Maenpuen S; Chaiyen P, Carboxylic acid reductase can catalyze ester synthesis in aqueous environments. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 133 (11), 5813–5817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel B; Hashem C; Leithold M; Sagmeister T; Tripp A; Stolterfoht-Stock H; Messenlehner J; Keegan R; Winkler CK; Ling JG; Younes SHH; Oberdorfer G; Abu Bakar FD; Gruber K; Pavkov-Keller T; Winkler M, Structure of the Reductase Domain of a Fungal Carboxylic Acid Reductase and Its Substrate Scope in Thioester and Aldehyde Reduction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (24), 15668–15674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hofrichter M; Ullrich R, Oxidations catalyzed by fungal peroxygenases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 19, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ullrich R; Nueske J; Scheibner K; Spantzel J; Hofrichter M, Novel haloperoxidase from the agaric basidiomycete Agrocybe aegerita oxidizes aryl alcohols and aldehydes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2004, 70 (8), 4575–4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kellner H; Luis P; Pecyna MJ; Barbi F; Kapturska D; Küger D; Zak DR; Marmeisse R; Vandenbol M; Hofrichter M, Widespread occurrence of expressed fungal secretory peroxidases in forest soils. PLoS One 2014, 9 (4), e95557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hofrichter M; Kellner H; Pecyna MJ; Ullrich R, Fungal Unspecific Peroxygenases: Heme-Thiolate Proteins That Combine Peroxidase and Cytochrome P450 Properties. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp 341–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kinner A; Rosenthal K; Lütz S, Identification and Expression of New Unspecific Peroxygenases - Recent Advances, Challenges and Opportunities. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 705630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beltran-Nogal A; Sanchez-Moreno I; Mendez-Sanchez D; Gomez de Santos P; Hollmann F; Alcalde M, Surfing the wave of oxyfunctionalization chemistry by engineering fungal unspecific peroxygenases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2022, 73, 102342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bormann S; Gomez Baraibar A; Ni Y; Holtmann D; Hollmann F, Specific oxyfunctionalizations catalyzed by peroxygenases: opportunities, challenges and solutions. Catal. Sci. Technol 2015, 5 (4), 2038–2052. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y; Lan D; Durrani R; Hollmann F, Peroxygenases en route to becoming dream catalysts. What are the opportunities and challenges? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 37, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hofrichter MK, Harald; Herzog Robert; Karich Alexander; Liers Christiane; Scheibner Katrin; Kimani Virginia Wambui; Ullrich Rene, Fungal Peroxygenase: A Phylogenetically Old Superfamily of Heme Enzymes with Promiscuity for Oxygen Transfer Reactions. In Grand challenges in fungal biotechnology, Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology, Nevalainen H, Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp 369–403. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hobisch M; Holtmann D; Gomez de Santos P; Alcalde M; Hollmann F; Kara S, Recent developments in the use of peroxygenases – Exploring their high potential in selective oxyfunctionalisations. Biotechnol. Adv 2021, 51, 107615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hofrichter M; Kellner H; Herzog R; Karich A; Kiebist J; Scheibner K; Ullrich R, Peroxide-Mediated Oxygenation of Organic Compounds by Fungal Peroxygenases. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (1), 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Monterrey DT; Menés-Rubio A; Keser M; Gonzalez-Perez D; Alcalde M, Unspecific peroxygenases: The pot of gold at the end of the oxyfunctionalization rainbow? Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem 2023, 41, 100786. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sigmund M-C; Poelarends GJ, Current state and future perspectives of engineered and artificial peroxygenases for the oxyfunctionalization of organic molecules. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3 (9), 690–702. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ebner K; Pfeifenberger LJ; Rinnofner C; Schusterbauer V; Glieder A; Winkler M, Discovery and Heterologous Expression of Unspecific Peroxygenases. Catalysts 2023, 13 (1), 206. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Faiza M; Lan D; Huang S; Wang Y, UPObase: an online database of unspecific peroxygenases. Database 2019, baz122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rotilio L; Swoboda A; Ebner K; Rinnofner C; Glieder A; Kroutil W; Mattevi A, Structural and Biochemical Studies Enlighten the Unspecific Peroxygenase from Hypoxylon sp. EC38 as an Efficient Oxidative Biocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (18), 11511–11525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karich A; Ullrich R; Scheibner K; Hofrichter M, Fungal Unspecific Peroxygenases Oxidize the Majority of Organic EPA Priority Pollutants. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ullrich R; Poraj-Kobielska M; Scholze S; Halbout C; Sandvoss M; Pecyna MJ; Scheibner K; Hofrichter M, Side chain removal from corticosteroids by unspecific peroxygenase. J. Inorg. Biochem 2018, 183, 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piontek K; Strittmatter E; Ullrich R; Grobe G; Pecyna MJ; Kluge M; Scheibner K; Hofrichter M; Plattner DA, Structural Basis of Substrate Conversion in a New Aromatic Peroxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288 (48), 34767–34776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peter S; Kinne M; Ullrich R; Kayser G; Hofrichter M, Epoxidation of linear, branched and cyclic alkenes catalyzed by unspecific peroxygenase. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2013, 52 (6–7), 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]