Abstract

We describe the evolution of treatment recommendations for chronic hypertension (CHTN) in pregnancy, the CHTN and pregnancy (CHAP) trial, and its impact on obstetric practice. The US multicenter CHAP trial showed that antihypertensive treatment for mild CHTN in pregnancy (blood pressures [BP] <160/105 mmHg) to goal <140/90mmHg, primarily with labetalol or nifedipine, compared to no treatment unless BP were severe reduced the composite risk of superimposed severe preeclampsia, indicated preterm birth<35weeks, placental abruption, and fetal/neonatal death. As a result of this trial, professional societies in the United States recommended treatment of patients with CHTN in pregnancy to BP goal <140/90mmHg.

Keywords: chronic hypertension, pregnancy, antihypertensive treatment, CHAP trial

Introduction

Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy - Definition and Epidemiology

Chronic hypertension in pregnancy, defined as elevated blood pressures before pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation on 2 or more occasions at least 4 hours apart with systolic ≥140 and/or diastolic ≥90 mmHg, affects up to 2% of all pregnant patients (Vidaeff, 2019). Risk factors for chronic hypertension include increasing age, Black race, family history of chronic hypertension, obesity (which affects over 40% of reproductive aged people in the United States), excess alcohol and tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease (Whelton 2017; Creanga, 2022; Ananth, 2019). The 2017 American Collage of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) revised guidelines for the diagnosis of hypertension in the general population identified the new category of Stage 1 hypertension (systolic blood pressures 130–139 mmHg and/or diastolic 80–89 mmHg), some patients will present during pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension based on these criteria (Whelton et al. 2017).

Chronic hypertension in pregnancy increases maternal risks of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm delivery, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and short- and long-term cardiovascular risks of heart failure, pulmonary edema, stroke, renal failure and death. Fetal risks of chronic hypertension include miscarriage, fetal growth restriction, small for gestational age and perinatal mortality and morbidities (Garovic, 2021; Cunningham, 2018; Vidaeff, 2019).

Prevention and Treatment Strategies for Chronic Hypertension

Lifestyle measures, including weight loss, increased dietary potassium, reduced dietary sodium, consumption of diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and low in fat, and increased physical activity of 90–150 minutes per week are the recommended interventions to control chronic hypertension. In addition to lifestyle interventions, pharmacologic therapy is recommended for all people with blood pressure ≥140/90mmHg (ACC/AHA Stage 2) and those with BPs 130–139/80–89 mmHg (ACC/AHA Stage 1) only if their 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk is 10-percent or greater (Whelton, 2018). For pregnant patients with chronic hypertension, weight loss during pregnancy is not routinely recommended due to concern about increased fetal growth risk (Rasmussen, 2009) and low dose aspirin is recommended to reduce preeclampsia (ACOG 2018). In addition, prior to the Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) trial (see below), it was controversial whether pharmacologic therapy should be recommended for pregnant patients with non-severe or mild chronic hypertension (blood pressures <160/110 mmHg) (ACOG, 2019).

Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy

Treatment for severe hypertension in pregnancy is recommended, albeit based on extrapolations from the management and treatment of non-pregnant adults to reduce risks of acute maternal cardiac and cerebrovascular events with severe hypertension (ACOG, 2019).

Prior to May 2022, antihypertensive treatment was not routinely recommended in the United States for patients with mild to moderate chronic hypertension (BP 140–159/80–109mmHg). This was due to concerns regarding potential fetal harm and the absence of evidence of maternal or fetal benefit. The overarching fetal concern was that reduction in blood pressures would reduce placental perfusion leading to fetal growth disturbances and increase the risk of small for gestational-age and low birth weight infants. In an early randomized trial of 263 patients with mild chronic hypertension where 87 patients received methyldopa, 86 received labetalol and 90 were randomized to the control group, despite significantly lower BPs throughout pregnancy in patients receiving either medication compared to the control group, the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia (18.4%, 16.3% and 15.6%), preterm delivery (12.5%, 11.6% and 10%) or placental abruption (1.1%, 2.3% and 2.2%) did not differ between patients receiving methyldopa, labetalol or controls respectively (Sibai, 1990). Systematic reviews of antihypertensive treatment trials of patients with mild chronic hypertension suggested treatment reduced severe hypertension but had no definitive maternal or perinatal benefits and additional systematic reviews suggested that treatment may be associated with increased risks of small for gestational age and low birth weight (Magee, 1999; Magee, 2000; von Dadelszen, 2000, Bellos, 2020).

In a 2015 report of an open label international (CHIPS) trial, 987 pregnant patients (736 [74.6%] of whom had chronic hypertension) were randomized to tight control (target diastolic BP of 85 mmHg) or less tight control (target diastolic BP of 100 mmHg). Although the frequency of severe hypertension was lower among patients in the tight control group, there were no significant differences in the incidence of the primary composite outcome of pregnancy loss or needing high level neonatal care for longer than 48 hours (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.77–1.35), or rates of serious maternal complications (OR 1.74, 95% CI 0.79–3.84) between groups. Notably the average BP achieved with tight control was 133/85mmHg. The incidence of small for gestational age <10th percentile was also not different between both groups (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.56–1.08) although the frequency appeared to be higher with tight control in the subgroup with chronic hypertension (Magee, 2015). A Cochrane review of 58 trials (5,909 women) also found that antihypertensive treatment reduced maternal mild-to-moderate hypertension (chronic or pregnancy-associated), but had no clear benefits on other maternal and fetal outcomes (Abalos, 2018). These studies suggesting uncertain benefits and potential risks of treatment of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy underscored the need for a large, adequately powered randomized trial to ascertain the benefits and safety of antihypertensive therapy for mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Thus, the Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) trial was designed, with the primary goal of identifying the benefits and safety of treating mild chronic hypertension during pregnancy to a blood pressure goal <140/90mmHg with antihypertensive therapy as compared with treatment only for severe hypertension.

The CHAP Trial

CHAP was an open label pragmatic randomized controlled trial conducted from September 2015 through March 2021 across >70 clinical sites in the United States. Pregnant patients with mild chronic hypertension were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive treatment with a first line antihypertensive agent (labetalol or nifedipine-extended release) to a blood pressure goal <140/90mmHg or usual care (no antihypertensive use unless BP≥160/105mmHg). The primary outcome was a composite of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features, indicated preterm birth <35 weeks’ gestation, placental abruption, and fetal or neonatal death. Included patients were at <23 weeks’ gestation with singleton pregnancies and a new or prior diagnosis of mild chronic hypertension. Patients who needed more than one blood pressure medication at randomization or had comorbidities requiring blood pressure treatment goals <140/90 mm Hg were excluded. The planned sample size was 2404.

A total of 29,772 patients were screened for eligibility and 27,353 excluded: the most frequent exclusions were low blood pressure while off treatment and advanced gestational age. A total of 2,408 randomized patients were included in the primary analysis. The mean age was 32 years, nearly 50% of included patients self-reported Black race and 56% had known chronic hypertension on oral anti-hypertensive medication.

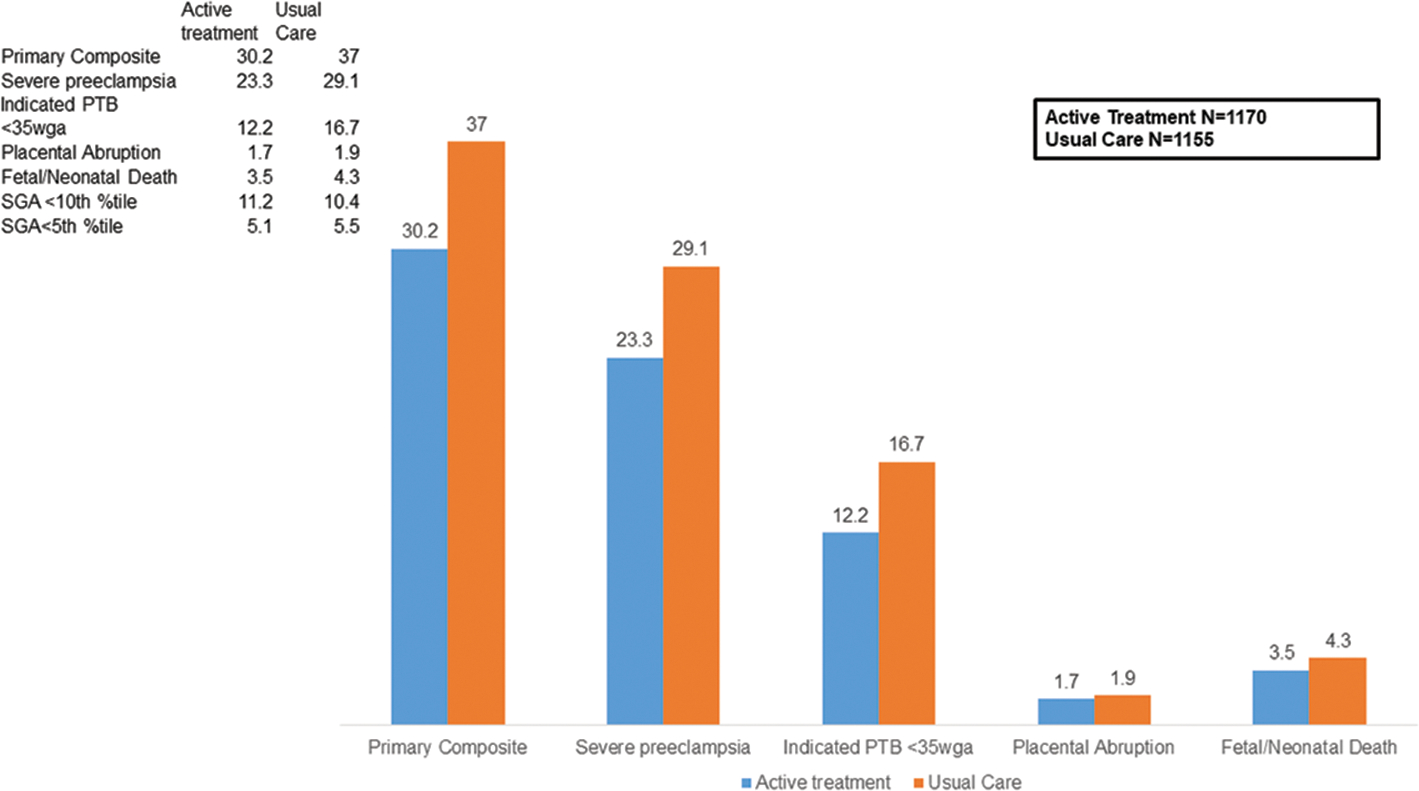

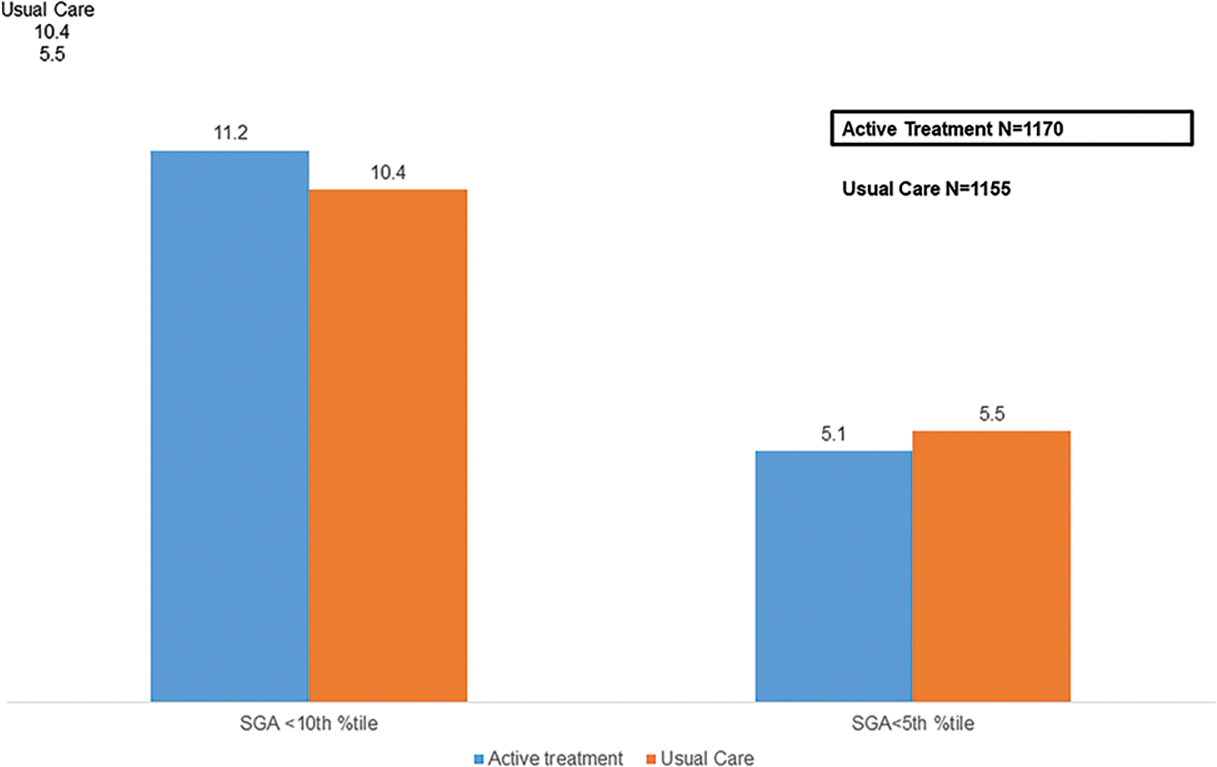

The main finding was an 18% reduction in the primary composite outcome (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.92) in those actively treated compared to those not treated. Treatment of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to BP goal <140/90 mmHg also reduced risks of severe preeclampsia (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.92), medically indicated preterm birth <35 weeks (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.60–0.89), and severe hypertension (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.90) [Figure 1]. Additionally, the risks of preterm birth (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.60–0.89) and low birth weight (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.71–0.97) were lower in the actively treated group (Tita, 2022). Notably, the risks of small for gestational age (SGA) were not significantly different between both groups (SGA <10th percentile RR 1.04, 95% 0.82–1.31) [Figure 2].

Figure 1: Outcomes of Active Treatment (vs. Usual Care) in Patients With Mild Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy.

Data are proportion/percentage

Figure 2: Incidence of Small for Gestational Age With Active Treatment (vs. Usual Care) of Mild Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy.

Data are proportion/percentage

Strengths of the trial include being powered to detect important maternal and neonatal outcomes- a significant limitation of prior studies, the diverse age and racial makeup of the study population which improved its generalizability to contemporary US patients, and early enrollment prior to 23wga that limited the study population to only patients with chronic hypertension, and not other forms of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Although a large number of screened patients were deemed ineligible for the trial, there were no differences in the characteristics between these patients and those enrolled into the trial. Importantly, the CHAP trial does not address the use of home blood pressure monitoring for the management of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy (ACOG, 2022; SMFM 2022).

Professional Societies’ Recommendations

Following the publication of the CHAP trial in May 2022, professional societies including the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology updated their clinical guidelines to recommend treatment of patients with mild chronic hypertension to BP goals of <140/90 mmHg in pregnancy. In addition to identifying treatment goals of <140/90mmHg, the trial results also clarified management of patients with chronic hypertension on medications prior to pregnancy-specifically, that continuing antihypertensive medication for this group of patients is preferred to discontinuing medications unless severe hypertension develops. Importantly, the trial does not identify an ideal lower blood pressure cut-off for patients with chronic hypertension in pregnancy, rather it identifies an upper threshold blood pressure goal at or above which treatment is beneficial to pregnancy (SMFM, 2022; ACOG, 2022).

Emerging questions and follow up studies post-CHAP

Long term follow-up for cardiovascular outcomes for mothers who were treated to lower BP goals in pregnancy in the CHAP trial is ongoing. In addition, follow up of infants and children to evaluate cardiometabolic and neurodevelopment is also planned.

An emerging area of interest concerns the ACC/AHA 2017 Stage 1 chronic hypertension threshold applied to pregnancy - blood pressures ≥130/80mmHg on more than one occasion (Whelton, 2018). During pregnancy however, despite numerous studies that demonstrate increased risks of preeclampsia, preterm birth and small for gestational age in patients with new stage 1 CHTN (BP 130–139/80–89mmHg), professional societies recommend the use of BPs >140/90mmHg for the treatment of chronic hypertension in pregnancy (Norton, 2021; Xiao, 2021; Li, 2021; Wu, 2020). If antihypertensive treatment to blood pressure <130/80mmHg is proven safe and further reduces pregnancy risks, an opportunity to unify diagnostic and treatment thresholds and management recommendations for chronic hypertension in- and outside of pregnancy may be less confusing for patients. A secondary analysis of CHAP raises the hypothesis that treatment to the lower threshold may be beneficial (Bailey, 2023). A treatment trial targeting stage 1 chronic hypertension thresholds in pregnancy as compared with the threshold of 140/90 may further refine clinical care.

Both first line recommended antihypertensive agents in pregnancy in the United States (labetalol and nifedipine) appear to be safe and equally effective in reducing pregnancy risks, however, labetalol may be better tolerated compared to nifedipine (Sanusi, 2023). Whether there are small differences in outcomes between medications is an area for future investigation.

Conclusion

The CHAP trial has led to significant changes in obstetric practice in the United States with Level 1 evidence now supporting the treatment of pregnant patients with mild chronic hypertension to blood pressures of <140/90mmHg. The effect on the primary outcome was modest and additional innovations in care are needed to reduce adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes of chronic hypertension in pregnancy.

References

- 1.Vidaeff A, Espinoza J, Simhan H, Pettker CM. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019;133(1):E26–E50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):E13–E115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creanga AA, Catalano PM, Bateman BT. Obesity in Pregnancy. Longo DL, ed. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):248–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMRA1801040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananth CV, Duzyj CM, Yadava S, Schwebel M, Tita ATN, Joseph KS. Changes in the prevalence of chronic hypertension in pregnancy, United States, 1970 to 2010.Hypertension. 2019; 74:1089–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garovic VD, Dechend R, Easterling T, Karumanchi SA, McMurtry Baird S, Magee LA, Rana S, Vermunt JV, August P; American Heart Association Council on Hypertension; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, Kidney in Heart Disease Science Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Stroke Council. Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2022. Feb;79(2):e21–e41. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000208. Epub 2021 Dec 15. Erratum in: Hypertension. 2022 Mar;79(3):e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, et al. Chronic Hypertension. In: Williams Obstetrics, 25e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1160785622 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, In stitute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: Low-Dose Aspirin Use During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e44–e52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):e26–e50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibai BM, Mabie WC, Shamsa F, Villar MA, Anderson GD. A comparison of no medication versus methyldopa or labetalol in chronic hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162(4):960–967. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91297-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arias F, Zamora J. Antihypertensive treatment and pregnancy outcome in patients with mild chronic hypertension. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1979;53(4):489–494. Accessed September 17, 2022. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy3.lhl.uab.edu/440653/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magee LA, von Dadelszen P, Rey E, Ross S, Asztalos E, Murphy KE, et al. Less-tight versus tight control of hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):407–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1404595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Fortnightly review: management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ. 1999;318(7194):1332–1336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7194.1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magee LA, Elran E, Bull SB, Logan A, Koren G. Risks and benefits of beta-receptor blockers for pregnancy hypertension: overview of the randomized trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;88(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00113-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Dadelszen P, Ornstein MP, Bull SB, Logan AG, Koren G, Magee LA. Fall in mean arterial pressure and fetal growth restriction in pregnancy hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08049-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellos I, Pergialiotis V, Papapanagiotou A, Loutradis D, Daskalakis G. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral antihypertensive agents in pregnant women with chronic hypertension: a network metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):525–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Gialdini C. Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD002252. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002252.pub4. Accessed 13 September 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, Dugoff L, Sibai B, Lawrence K, et al. Treatment for Mild Chronic Hypertension during Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. Published online April 2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Publications & Guidelines | SMFM.org - The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.smfm.org/publications/439-smfm-statement-antihypertensive-therapy-for-mild-chronic-hypertension-in-pregnancy-the-chap-trial

- 20.Clinical Guidance for the Integration of the Findings of the Chronic Hypertension and Pregnancy (CHAP) Study | ACOG. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2022/04/clinical-guidance-for-the-integration-of-the-findings-of-the-chronic-hypertension-and-pregnancy-chap-study [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton E, Shofer F, Schwartz H, Dugoff L. Adverse Perinatal Outcomes Associated with Stage 1 Hypertension in Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Perinatol. Published online November 2021. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Y, Liu J, Teng H, Ge W, Han B, Yin J. Stage 1 hypertension defined by the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and neonatal outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2021;25:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Zheng L, Gu Y, Jiang D, Wang G, Li J, et al. Early pregnancy stage 1 hypertension and high mean arterial pressure increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in Shanghai, China. J Hum Hypertens. Published online March 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00523-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu DD, Gao L, Huang O, Ullah K, Guo MX, Liu Y, et al. Increased Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Associated With Stage 1 Hypertension in a Low-Risk Cohort: Evidence From 47 874 Cases. Hypertension. 2020;75(3):772–780. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey EJ, Tita ATN, Leach J, Boggess K, Dugoff L, Sibai B, Lawrence K, Hughes BL, Bell J, Aagaard K, Edwards RK, Gibson K, Haas DM, Plante L, Metz TD, Casey BM, Esplin S, Longo S, Hoffman M, Saade GR, Foroutan J, Tuuli MG, Owens MY, Simhan HN, Frey HA, Rosen T, Palatnik A, Baker S, August P, Reddy UM, Kinzler W, Su EJ, Krishna I, Nguyen N, Norton ME, Skupski D, El-Sayed YY, Ogunyemi D, Galis ZS, Harper L, Ambalavanan N, Oparil S, Kuo HC, Szychowski JM, Hoppe K. Perinatal Outcomes Associated With Management of Stage 1 Hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2023. Sep 28. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005410. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanusi A, Tita AT. Outcomes of nifedipine versus labetalol for oral treatment of chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(1):S16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]