Abstract

Objective

Medial opening‐wedge high tibial osteotomy (MOWHTO) is a surgical procedure to treat medial compartment osteoarthritis in the knee with varus deformity. However, factors such as patellar height (PH) and the sagittal plane's posterior tibial slope angle (PTSA) are potentially overlooked. This study investigated the impact of alignment correction angle guided by computer‐designed personalized surgical guide plate (PSGP) in MOWHTO on PH and PTSA, offering insights for enhancing surgical techniques.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients who underwent 3D‐printed PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO at our institution from March to September 2022. The paired t‐tests assessed differences in all preoperative and postoperative measurement parameters. Multivariate linear regression analysis examined correlations between PTSA, CDI (Caton–Deschamps Index), and the alignment correction magnitude. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis determined the threshold of the correction angle, calculating sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve.

Results

A total of 107 patients were included in our study. The CDI changed from a preoperative mean of 0.97 ± 0.13 (range 0.70–1.34) to a postoperative mean of 0.82 ± 0.13 (range 0.55–1.20). PTSA changed from a preoperative mean of 8.54 ± 2.67 (range 2.19–17.55) to a postoperative mean of 10.54 ± 3.05 (range 4.48–18.05). The t‐test revealed statistically significant changes in both values (p < 0.05). A significant alteration in patellar height occurred when the correction angle exceeded 9.39°. Moreover, this paper illustrates a negative correlation between CDI change and the correction angle and preoperative PTSA. Holding other factors constant, each 1‐degree increase in the correction angle led to a 0.017 decrease in postoperative CDI, and each 1‐degree increase in preoperative PTSA resulted in a 0.008 decrease in postoperative CDI. PTSA change was positively correlated only with the correction angle; for each 1‐degree increase in the opening angle, postoperative PTS increased by 0.188, with other factors constant.

Conclusion

This study highlights the effectiveness and precision of PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO, focusing on the impact of alignment correction on PH and PTSA. These findings support the optimization of PSGP technology, which offers simpler, faster, and safer surgeries with less radiation and bleeding than traditional methods. However, PSGP's one‐time use design and the learning curve required for its application are limitations, suggesting areas for further research.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Medial opening‐wedge high tibial osteotomy, Patellar height, Personalized surgical guide plate, Posterior tibial slope angle

The impact of PSGP‐assisted High Tibial Osteotomy on CDI and PTSA.

Introduction

High tibial osteotomy (HTO) is a surgical procedure to treat medial compartment osteoarthritis in the knee with varus deformity. 1 This surgery rectifies the varus misalignment, redistributing the lower limb's weight‐bearing line of the knee. This realignment offloads the medial compartment, alleviating pain and potentially promoting cartilage regeneration, improving joint function. 2 , 3

While HTO has successfully corrected knee varus, its primary focus has been addressing deformities in the coronal plane. However, factors such as patellar height (PH) and the posterior tibial slope angle (PTSA) in the sagittal plane are potentially overlooked. 4 Decreased PH can result in patellar baja, subsequently leading to patellofemoral osteoarthritis. As Weale et al. concluded that a minimal 4% decrease in CDI causes a 1 mm decrease in the patella tendon height, leading to a 10 decrease in knee flexion and increased risk of patellofemoral pain. 5 This can cause significant symptoms in patients with preexisting patellofemoral changes and patients with patella baja. An increased PTSA can intensify the tension on the anterior cruciate ligament and alter tibiofemoral joint contact pressures. According to the measurements by Black et al., 6 changes in PTSA result in alterations in the distribution of forces on the articular surface: an increase in PTSA by more than 5° in the medial compartment leads to a significant anterior shift in the pressure center, while the lateral compartment shifts significantly posteriorly. Additionally, increased PTSA increases tension on the anterior cruciate ligament, further accelerating knee joint degeneration. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 This finding was evident in medial opening‐wedge high tibial osteotomy (MOWHTO). 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Therefore, clarifying the impact of MOWHTO on PH and PTSA is of significant importance for improving surgical techniques and outcomes.

Recent years have witnessed the increasing adoption of digital orthopedic techniques in clinical practices. 17 Among these, the application of computer‐assisted design coupled with 3D‐printed osteotomy guides has enhanced surgical standardization, precision, and personalization while reducing surgical time, bleeding, and risk of complications. 18 , 19 , 20 Mao et al. 21 compared personalized surgical guide plate (PSGP) and conventional manual osteotomy in MOWHTO. The results showed that the PSGP group had shorter surgical times (37.8 min vs. 54.6 min, p < 0.05) and fewer intraoperative radiographic exposures (1.3 vs. 4.1 times, p < 0.05). Chaouche et al. 22 reported the results of 100 PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO cases, finding that applying PSGP significantly improved knee joint function and shortened the surgical learning curve. Subsequently, their team further demonstrated that PSGP improved distal femoral osteotomy correction accuracy. 23

The objectives of this study are: (i) to introduce the surgical technique of PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO; and (ii) to investigate the impact of the degree of correction on PH and PTSA in PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO.

Methods

This research was approved by our institutional review board and the patients gave their informed consent (protocol number2021‐013).

Patient Selection

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients who underwent PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO at our institution between March and September 2022. Patients selected for this procedure exhibited symptoms and indications of knee joint osteoarthritis. These patients had previously undergone conservative treatments and no significant improvement.

The inclusion criteria were: (i) medial compartment osteoarthritis with knee varus; (ii) patients having complete pre and post‐operative lateral and full‐length standing anteroposterior X‐rays; and (iii) Kellgren–Lawrence classification grade 2 or 3.

Patients who met any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: lost follow‐up, patellofemoral osteoarthritis, tri compartmental osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, Magnetic Resonance Imaging(MRI) evidenced knee ligament injuries, knee range of motion below 100°,flexion contracture exceeds 10°, secondary tibial varus due to rickets, and growth plate disorders.

Nowadays, an increasing number of people believe that, with the improvement of average health levels and the gradual increase in life expectancy, age should not be an absolute limiting factor for HTO. In our experiment, we conducted HTO surgeries on some elderly patients, achieving satisfactory therapeutic effects, provided that their physical conditions were allowed. Therefore, age is not considered a limiting factor in this study. 24 , 25 , 26

Preoperative Planning and Surgical Technique

All patients underwent bilateral lower limb scans under low‐dose CT, with a slice thickness of 0.625 mm. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format computed tomography (CT) images were imported into Mimics 21.0 software. Bone parameters were extracted using different thresholds, and segmentation of the femur, tibia, fibula, and patella was achieved.

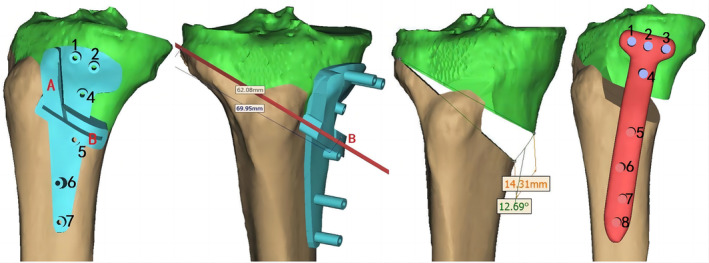

Preoperative anteroposterior full‐length standing view and CT‐scanning images of the knee joint were used to determine the anatomical characteristics of the lower extremity, including the hip center, ankle center, joint line, mechanical axis, cutting point, and lateral hinge. The target alignment, based on the Fujisawa point, involved performing simulated surgeries on a 3D model in Mimics 21.0. The generated intraoperative osteotomy data included osteotomy position, correction angle, weight bearing line percentage, distraction angle, sawing direction, depth, and screw sizes used (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The target alignment, based on the Fujisawa point, involved performing simulated surgeries on a 3D model in Mimics 21.0. The generated intraoperative osteotomy data included osteotomy position, correction angle, weight bearing line percentage, distraction angle, sawing direction, depth, and screw sizes used.

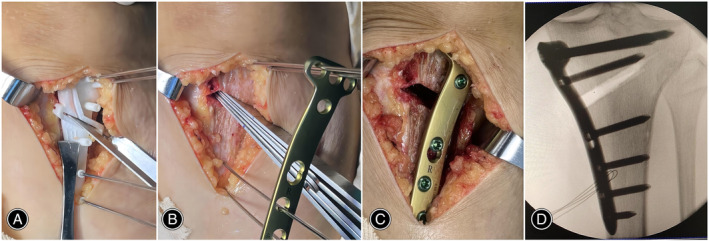

The surgical technique of the biplanar HTO using a 3D‐printed patient‐specific instrument was used for all included patients in this study. 19 , 21 Osteotomy guides were created using the Offset function and Boolean operations, with a groove matching the osteotomy plane. Surgeons finalized the position of the Kirschner wire and osteotomy plane. Finally, a patient‐specific plate was designed to fit the 3D correction model. Physical 3D models of the osteotomy guides were manufactured using 3D printing technology by SHILUOKE MEDICAL, Tianjin China (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Osteotomy guides were created using the Offset function and Boolean operations, with a groove matching the osteotomy plane. Surgeons finalized the position of the Kirschner wire and osteotomy plane. Finally, a patient‐specific plate was designed to fit the 3D correction model. After the osteotomy, the Tomofix locking plate is applied for fixation.

Surgery

A single surgeon performed all procedures.

Anesthesia and Positioning

The patient received either general anesthesia or lumbar epidural anesthesia. After satisfactory anesthesia, the prone position was chosen, and a tourniquet was applied to the limb.

Arthroscopy

Pre‐osteotomy diagnostic knee arthroscopy was conducted on patients to assess joint surfaces and meniscal conditions. This was followed by arthroscopic debridement if the patient had meniscus injury, loose bodies in the joint, or narrowing of the intercondylar notch.

Exposure

A medial longitudinal incision was made, starting proximally at the joint line level and ending 2 cm distal to the posterior inner aspect of the tibial tuberosity. The incision extended through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and deep fascia. The superficial layer of the medial collateral ligament was released, exposing the pes anserinus and appropriately freeing it.

Osteotomy

A 3D‐printed osteotomy guide was placed snugly against the bone surface, and four guide Kirschner wires were used to fix it to the bone surface. One Kirschner wire was inserted along the pre‐designed osteotomy plane on the guide. Intraoperatively, the position of the Kirschner wires was confirmed under fluoroscopy, ensuring satisfaction with the osteotomy plane and inclination angle. A Hoffman retractor was used to protect the posterior vessels, nerves, and muscular tissues of the tibia, and a biplanar‐plane osteotomy was performed along the gap of the guide plate using an oscillating saw.

Fixation

After osteotomy, the guide was removed, and the Tomofix locking plate (Ruihe Medical, China) was placed with the Kirschner wires. The osteotomy area was spread open according to the preoperative design angle, and screws were sequentially drilled and inserted. The position of the plate and the length of the screws were confirmed again under fluoroscopy. Hemostasis was achieved upon tourniquet release, and the gap was spread open to insert allogeneic bone. After placing a drainage tube and washing the wound, it was closed and dressed. (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

(A) A 3D‐printed osteotomy guide was placed snugly against the bone surface, and four guide Kirschner wires were used to fix it to the bone surface. The biplanar‐plane osteotomy was performed along the gap of the guide plate using an oscillating saw. (B) After osteotomy, the guide was removed, and the Tomofix locking plate was placed with the Kirschner wires. (C) The osteotomy area was spread open according to the preoperative design angle, and screws were sequentially drilled and inserted. (D) The position of the plate and the length of the screws were confirmed again under fluoroscopy.

Key Technical Points

Clinical practitioners must have experience with conventional surgeries before adopting this technology or simulating the procedure on physical models for validation before operating. Clinicians should not unthinkingly follow the guidance of the templates during actual operations. Due to template strength and printing accuracy issues, timely adjustments should be made based on the actual situation, such as template breakage or needle entry point deviation occurs during surgery.

Postoperative Management

All patients began quadriceps femoris muscle exercises and ankle pump training immediately after anesthesia receded to prevent venous thromboembolism and muscle atrophy.

On the second day after surgery, patients performed knee flexion exercises under the guidance of a rehabilitation physician, with a requirement of achieving 90° of passive joint movement. Patients were allowed to walk with crutches on the ground with partial weight bearing.

Full weight‐bearing was typically allowed around 4–6 weeks postoperatively. During this period, joint mobility was encouraged to increase to the normal range.

Outcome Measures

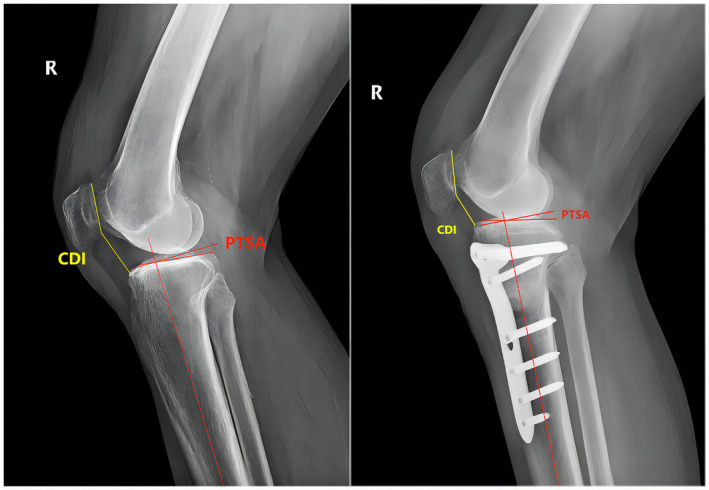

The Caton–Deschamps index (CDI) was utilized to measure PH. CDI is the ratio of the distance from the inferior pole of the patella to the anterior angle of the tibial plateau and the length of the articular surface of the patella. Typically, it ranges between 0.8 and 1.2. 27

The posterior tibial slope angle (PTSA) is the angle between the tibial plateau line and the vertical line to the tibial horizontal axis in the lateral X‐ray, which usually varies between 0 and 18 degrees 7 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The Caton–Deschamps index (CDI) is the ratio of the distance from the inferior pole of the patella to the anterior angle of the tibial plateau and the length of the articular surface of the patella. Typically, it ranges between 0.8 and 1.2. The posterior tibial slope angle (PTSA) is the angle between the tibial plateau line and the vertical line to the tibial horizontal axis in the lateral X‐ray, which usually varies between 0 and 18 degrees.

Two independent observers carried out all radiological measurements. Intra‐observer and inter‐observer reliabilities were expressed as intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICC), which range from 0 (totally inconsistent) to 1 (entirely consistent).

Clinical Assessment and Follow‐up

All patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. Follow‐up assessments included anteroposterior full‐length standing views of the lower extremities, and anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the knees.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data underwent a Shapiro–Wilk test using SPSS and the continuous quantities were normally distributed. Paired t‐tests were employed to assess differences in all preoperative and postoperative measurement parameters. Multivariate linear regression analysis assessed the correlation between PTSA, CDI, and the correction angle. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was utilized to determine the threshold of the correction angle and compute sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 107 patients were included in our study. The cohort included 38 males (35.5%) and 69 females (64.5%), with an average age of 61.9 ± 7.19, ranging from 36 to 76 years.

Clinical Outcomes and Complications

For all samples, osteotomy guides were successfully placed in put a planned locations on the tibia with good alignment; hence, all osteotomies were performed as planned.

All patients underwent arthroscopy once during the surgery. The operative time (including the arthroscopy times) averaged 66.5 ± 11.3, ranging from 43 to 96 min. Due to the application of a tourniquet, there was no significant bleeding during the operation. After removing the drainage tube 24 h postoperatively, the total drainage volume averaged 80 ± 30.8 mL, ranging from 20 to 150 mL. All participants underwent a minimum follow‐up of 1 year.

None of the patients experienced significant complications such as iatrogenic neurovascular injury, deep infections, wound dehiscence, pain syndrome, range of motion deficit, delayed bone union, loss of correction, as well as the need for revision or reoperation. One patient was found to have a superficial infection postoperatively, which was cured with non‐surgical treatment. Two patients underwent surgical treatment for deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs.

Radiological Outcomes

In this study, interobserver and intraobserver variability did not show clinically relevant differences in the measurement of PH either preoperatively or postoperatively (ICC 0.92).

The CDI shifted from 0.97 ± 0.13 preoperatively (0.70–1.34) to 0.82 ± 0.13 postoperatively (0.55–1.20). The PTSA changed from 8.54 ± 2.67 preoperatively (2.19–17.55) to 10.54 ± 3.05 postoperatively (4.48–18.05). Using the paired t‐tests, both sets of numerical changes showed statistical significance (p < 0.05) (Table.1).

TABLE 1.

Pre and postoperative radiological measurements.

| Radiological parameters | Preoperatively | Postoperatively | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDI | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.13 | 0.000 |

| PTSA (°) | 8.54 ± 2.67 | 10.54 ± 3.05 | 0.000 |

Note: The parameters were compare by independent t‐tests.

Abbreviations: CDI, Caton‐Deschamps Index; PTSA, posterior tibial slope angle.

All models presented a standard distribution scatter plot of the relationship between the z‐residual and residual predicted values, suggesting these values were independent and met the specific conditions for performing linear regression.

A multivariate regression analysis was conducted post‐CDI procedure with the postoperative CDI as the dependent variable. Independent variables included the correction angle, preoperative CDI, preoperative PTSA value, and the difference in PTSA value before and after surgery. The stepwise regression method was utilized to select independent variables. It was determined that the difference in PTSA value before and after surgery were not significantly different (p > 0.1) and were thus removed from the model.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielded a regression mean square of 0.349, a residual mean square of 0.009, and an F value of 46.540 (p < 0.05), indicating that the regression equation was significant. The collinearity diagnostics yielded variance inflation factors all less than 2. The R‐value was 0.759, and the Durbin–Watson statistic was 1.972. The results of multivariate linear regression analysis are present in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Multivariate linear regression analysis.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficient | t value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.499 | 5.866 | 0.000 |

| Preoperative CDI | 0.606 | 9.411 | 0.000 |

| Correction angle | −0.017 | −5.234 | 0.000 |

| Preoperative PTSA | −0.008 | −2.448 | 0.016 |

Note: The postoperative CDI as dependent variable.

Abbreviations: CDI, Caton‐Deschamps Index; PTSA, posterior tibial slope angle.

The postoperative PTSA value was used as the dependent variable, with the correction angle, preoperative PTSA value, preoperative CDI, and the difference in CDI before and after surgery as independent variables. The stepwise regression method was utilized to select independent variables. It was found that the preoperative CDI, and the difference in CDI before and after surgery showed no significant differences (p > 0.1) and were therefore excluded from the model.

ANOVA yielded a regression mean square of 176.466, a residual mean square of 6.067, and an F value of 29.087 (p < 0.05), indicating that the regression equation was significant. The collinearity diagnostics indicated variance inflation factors all less than 2. The R‐value was 0.599, and the Durbin‐Watson statistic was 0.770. The results of multivariate linear regression analysis are present in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate linear regression analysis

| Model | Unstandardized coefficient | t value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.439 | 3.198 | 0.002 |

| Preoperative PTSA | 0.634 | 6.996 | 0.000 |

| Correction angle | 0.188 | 2.033 | 0.045 |

Note: The postoperative PTSA as dependent variable.

All patients were split into two groups based on the postoperative presence or absence of patella baja (CDI <0.8) to investigate the threshold of correction angle for influencing PH in X‐ray images.

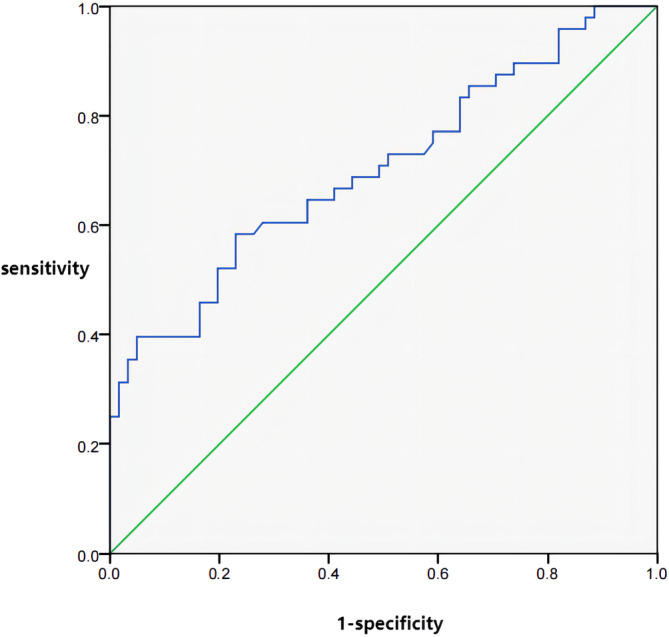

The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.702 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.602–0.803. Compared to the reference line, this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.000). In this case, the threshold of correction angle is 9.39, The sensitivity and specificity were 58.3% and 77%, respectively (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the correction angle. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.702 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.602–0.803. Compared to the reference line, this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.000). In this case, the threshold of correction angle is 9.39, The sensitivity and specificity were 58.3% and 77%, respectively.

Discussion

The findings of this study are as follows: (i) elucidating the superiority of PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO. In this study, all PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO surgery patients achieved satisfactory clinical outcomes. Osteotomies were performed as scheduled for all samples. None of the patients experienced significant complications or needed revision or reoperation; (ii) clarifying the impact of alignment correction magnitude in PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO on PH and PTSA. This study observed a notable change in PH when the correction angle was more significant than 9.39. Second, we observed a negative correlation between the change in CDI, preoperative PTSA, and corrective angle. Meanwhile, the change in PTSA only showed a positive correlation with the correction angle.

Advantages and Limitations of the Technology

In our study, all patients underwent surgery according to the preoperative plan and achieved satisfactory results. All participants underwent a minimum follow‐up of 1 year. None of the patients experienced significant complications.

The advantages of the surgical technique include improved surgical standardization, precision, and personalization. Using PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO allows for a more consistent and accurate surgical approach, leading to better patient outcomes. Additionally, the technique helps to reduce surgical time, bleeding, and the risk of complications.

However, there are also limitations to consider. One limitation is the inherent learning curve associated with this technique. Clinical practitioners must have experience with conventional surgeries before adopting PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO or simulating the procedure on physical models for validation. This ensures that the surgeon is proficient in the technique and can effectively navigate any challenges during surgery.

Another area for improvement is the strength and printing accuracy of the templates used in the procedure. Timely adjustments should be made based on the actual situation, such as if template breakage or needle entry point deviation occurs during surgery. This requires careful monitoring and adaptation during the surgical process.

Analysis of Radiological Outcomes

First, in this study, a notable change in PH was observed when the correction angle was more significant than 9.39. Second, we observed a negative correlation between the change in CDI and preoperative PTSA and corrective angle. Meanwhile, the change in PTSA only showed a positive correlation with the correction angle.

The factors influencing changes in PH are numerous, including the angle of correction angle, pre‐ and postoperative PTSA values, contracture of the patellar ligament caused by postoperative immobilization, and the choice of surgical technique. 28 , 29 , 30 In the current study, all patients underwent a MOWHTO with a biplane technique. As for the variance in PH changes, different authors have reported varying results. 12 , 16 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 Current studies suggest that when using a biplane technique for the osteotomy, the impact on PH can be minimized. 10 , 12 Furthermore, a meta‐analysis indicated that the choice of PH measurement method also affects the outcome. 16 This study found that the Blackburne–Peel index (BPI) and CDI significantly decreased post‐MOWHTO, whereas changes in the Insall–Salvati index (ISI) were not significant. The authors proposed that this is due to the measurement of ISI being dependent on the length of the patellar ligament, which is difficult to identify post‐HTO. Second, the measurement of BPI is reliant on the PTSA, which was an observed variable in this experiment; hence, we chose CDI as the criterion for this experiment.

In this study, we found that as the correction angle increased, PH decreased, which is consistent with the results of most previous studies. 12 , 16 , 31 , 34 , 35 Some authors believe that PH will not change if preoperative planning and surgical operations are appropriate. 28 , 32 Other authors have postulated a correlation between changes in PH and the difference in PTSA values pre‐and post‐surgery. 7 , 36 This study discovered that the change in PH was not only related to the correction angle but also to the preoperative PTSA level. This finding is seldom addressed in previous research. However, limited by our statistical methods, this result is obtained by ignoring other confounding factors. Applying the ROC results to all cases, which may be overgeneralized. In the future, we will need more in‐depth research to confirm this result.

Previous studies have not reported on the threshold of the correction angle impact on PH, but some biomechanical studies have suggested similar outcomes. Javidan et al. 16 conducted a biomechanical cadaver study on nine human cadavers, making corrections at 10 mm and 15 mm. When a more significant correction of 15 mm was made, significantly higher patellofemoral joint contact pressures were produced at all degrees of knee flexion. Stoffel et al. 37 obtained similar results under the same conditions (14 mm) and suggested that a distal tibial tubercle osteotomy should be chosen for patients with preoperative anterior knee pain. Several studies have identified the angle of correction as an independent predictor for the progression of patellofemoral joint arthritis after MOWHTO. Otakara et al. 38 conducted a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine the change in the medial proximal tibial angle greater than 10° post‐MOWHTO and biplane proximal tibial osteotomy associated with progressive patellofemoral compartment OA. Tanaka et al. 39 concluded that PF OA progression was observed post‐MOWHTO in patients with a change in DmpTA greater than 9° or a medial gap opening of 13 mm. Song et al.39 also found similar findings, with the correction angle for PF OA progression (DmpTA) being 10°. In this experiment, through ROC analysis, we determined that the threshold of correction angle is 9.39°, similar to previous research.

However, limited by our statistical methods, this result is obtained by ignoring other confounding factors. There is no direct evidence to prove the actual impact of this result on the patellofemoral joint. It is not advisable to decide on the use of infra‐tubercle osteotomy based on this result alone. In the future, further biomechanical research or three‐dimensional finite element simulations are required to validate this outcome.

Regarding the impact of MOWHTO on PTSA, there is some contention in the results of different studies. Most research indicates that PTSA increases post‐MOWHTO. 10 , 11 , 14 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 Others assert that PTSA does not change significantly with proper operative techniques. 35 , 46 , 47 Generally, these differences are thought to be related to surgical techniques and the placement of the implants. 44 , 47 , 48

Some authors have successfully mitigated these effects through careful preoperative planning and precise intraoperative techniques, 18 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 and other technical adjustments to minimize changes in PTSA include intraoperative monitoring of tibial slope with Kirschner wires, ensuring complete osteotomy of the posterior cortex, adequately releasing soft tissues, and maintaining an anterior–posterior cortical gap ratio of 1:2. 46 , 49 , 50 LaPrade et al.'s research indicates that when internal fixation is placed anteriorly, PTSA increases by 4.3°, whereas when internal fixation is posteriorly placed, PTSA only increases by 1°. 48 However, in this study, the postoperative change in the tibial slope angle remained positively correlated with the correction angle. However, there is no conclusive evidence suggesting that this has a significant impact on the actual surgical outcomes. As reported by Kyung et al. 51 PTSA value changes of up to 5° have no clinical significance. Savarese et al.63 propose that during HTO surgery, the extent of PTSA change should be <8°, which may compromise the stability of the anterior cruciate ligament. Further research is needed to confirm these findings.

Regrettably, in our study, PSGP did not show significant changes in PH and PTSA compared to traditional techniques. The advantage of PSGP lies in its precision and efficiency. Compared to conventional methods, it can better avoid errors and reduce the number of intraoperative X‐ray exposures and operation time.

In this experiment, by understanding the impact of PSGP on PH and PTSA, we can better plan preoperatively to avoid potential postoperative complications such as patella baja and excessive PTSA, thereby reducing the failure rate of the surgery. In future research, we plan to refine the surgical technique further to mitigate the impact of MOWHTO on PH and PTSA.

Clinical Application Prospect

Compared with traditional surgery, applying PSGP can simplify surgical procedures, shorten operation time, and reduce intraoperative radiation exposure and bleeding while ensuring surgical safety and precision. However, the individualized design of PSGP makes it a disposable item, unable to be reused, leading to resource wastage. Additionally, research indicates that PSGP technology still requires a particular learning curve.64 Therefore, clinicians should not unthinkingly follow the guidance of the templates during actual operations.

Concurrently, with the ongoing development of digital orthopedic technology, we anticipate witnessing more innovations and optimized surgical approaches to meet patient needs better and improve treatment outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is that it elucidates the reliability of PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO and clarifies the impact of alignment correction magnitude in PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO on PH and PTSA. By understanding the effect, we can better plan preoperatively to avoid potential postoperative complications such as patella baja and excessive PTSA.

However, this study has certain limitations. First, being a single‐center retrospective study, it is difficult to avoid the influence of confounding factors altogether, and its persuasiveness may need to be stronger. Such as, we determined that the threshold of the correction angle is 9.39°, this is also a result obtained by ignoring other confounding factors. Second, the focus of this study was primarily on changes in imaging indicators and did not delve into the impact on the actual functional aspects of patients. Last, the follow‐up duration in this study was relatively short, and further in‐depth research is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusion

The most significant finding of this study is that it elucidates the reliability of PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO and clarifies the impact of alignment correction magnitude in PSGP‐assisted MOWHTO on PH and PTSA. In this study, we observed a negative correlation between the change in CDI and preoperative PTSA and correction angle, with PH showing significant changes when the correction angle exceeds 9.39°. Conversely, the change in PTSA is only positively correlated with the correction angle. This conclusion provides theoretical support for further optimizing PSGP‐assisted technology. Compared with traditional surgery, applying PSGP can simplify surgical procedures, shorten operation time, and reduce intraoperative radiation exposure and bleeding while ensuring surgical safety and precision. However, the individualized design of PSGP makes it a disposable item, unable to be reused, leading to resource wastage. Additionally, research indicates that PSGP technology still requires a particular learning curve.

Author Contributions

Chang Liu, Jianxiong Ma, and Xinlong Ma contributed in the conception and design of study. Haohao Bai, Bin Zhao, and Songqing Ye contributed to the execution of the experiments. Fei Xing and Xuan Jiang contributed in data acquisition. Chang Liu and Wei Luo analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors are in agreement with the manuscript.

Funding Information

This work was supported in part by Central Guided Local Science and Technology Development Funds of China (grant Nos. 22ZYJDSY00110), and in part by Tianjin Municipal Health Science and Technology Project (grant Nos. TJWJ2022MS025).

Conflict of Interest Statement

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the clinical and experimental support provided by the Digital Orthopedics Department of Tianjin Hospital. We are also grateful for the technical support provided by the Biomechanics Labs of Orthopedics Institute of Tianjin Hospital.

Chang Liu and Wei Luo contributed equally to this study and should be considered co‐first authors.

References

- 1. Jeong SH, Samuel LT, Acuna AJ, Kamath AF. Patient‐specific high tibial osteotomy for varus malalignment: 3D‐printed plating technique and review of the literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2022;32:845–855. 10.1007/s00590-021-03043-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magnussen RA, Lustig S, Demey G, Neyret P, Servien E. The effect of medial opening and lateral closing high tibial osteotomy on leg length. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1900–1905. 10.1177/0363546511410025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu X, Chen Z, Gao Y, Zhang J, Jin Z. High Tibial osteotomy: review of techniques and biomechanics. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:8363128. 10.1155/2019/8363128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He M, Zhong X, Li Z, Shen K, Zeng W. Progress in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis with high tibial osteotomy: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2021;10:56. 10.1186/s13643-021-01601-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weale AE, Murray DW, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE. The length of the patellar tendon after unicompartmental and total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:790–795. 10.1302/0301-620x.81b5.9590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Black MS, D'Entremont AG, Mccormack RG, Hansen G, Carr D, Wilson DR. The effect of wedge and tibial slope angles on knee contact pressure and kinematics following medial opening‐wedge high tibial osteotomy. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2018;51:17–25. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brouwer RW, Bierma‐Zeinstra SM, van Koeveringe AJ, Verhaar JA. Patellar height and the inclination of the tibial plateau after high tibial osteotomy. The open versus the closed‐wedge technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1227–1232. 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.15972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giffin JR, Vogrin TM, Zantop T, Woo SL, Harner CD. Effects of increasing tibial slope on the biomechanics of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:376–382. 10.1177/0363546503258880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hohmann E, Bryant A, Imhoff AB. The effect of closed wedge high tibial osteotomy on tibial slope: a radiographic study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:454–459. 10.1007/s00167-005-0700-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaper BP, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Macdonald SJ. Patellar infera after high tibial osteotomy. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:168–173. 10.1054/arth.2001.20538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu L, Lin J, Jin Z, Cai X, Gao W. Comparison of clinical and radiological outcomes between opening‐wedge and closing‐wedge high tibial osteotomy: a comprehensive meta‐analysis. PloS One. 2017;12:e171700. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Portner O. High tibial valgus osteotomy: closing, opening or combined? Patellar height as a determining factor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3432–3440. 10.1007/s11999-014-3821-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tabrizi A, Soleimanpour J, Sadighi A, Zare AJ. A short term follow up comparison of genu varum corrective surgery using open and closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. Malays Orthop J. 2013;7:7–12. 10.5704/MOJ.1303.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gaasbeek RD, Nicolaas L, Rijnberg WJ, van Loon CJ, van Kampen A. Correction accuracy and collateral laxity in open versus closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. A one‐year randomised controlled study. Int Orthop. 2010;34:201–207. 10.1007/s00264-009-0861-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee O, Ahn S, Lee Y. Changes of sagittal and axial alignments of patella after open‐ and closed‐wedge high‐Tibial osteotomy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Knee Surg. 2018;31:625–634. 10.1055/s-0037-1605561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stoffel K, Willers C, Korshid O, Kuster M. Patellofemoral contact pressure following high tibial osteotomy: a cadaveric study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1094–1100. 10.1007/s00167-007-0297-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li Z. Digital orthopedics: the future developments of orthopedic surgery. J Pers Med. 2023;13:292. 10.3390/jpm13020292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosso F, Rossi R, Neyret P, Śmigielski R, Menetrey J, Bonasia DE, et al. A new three‐dimensional patient‐specific cutting guide for opening wedge high tibial osteotomy based on ct scan: preliminary in vitro results. J Exp Orthop. 2023;10:80. 10.1186/s40634-023-00647-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu Y, Jin X, Zhao X, Wang Y, Bai H, Lu B, et al. Computer‐aided Design of Distal Femoral Osteotomy for the valgus knee and effect of correction angle on joint loading by finite element analysis. Orthop Surg. 2022;14:2904–2913. 10.1111/os.13440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H, Park J, Park K, et al. Evaluation of accuracy of a three‐dimensional printed model in open‐wedge high Tibial osteotomy. J Knee Surg. 2019;32:841–846. 10.1055/s-0038-1669901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mao Y, Xiong Y, Li Q, Chen G, Fu W, Tang X, et al. 3D‐printed patient‐specific instrumentation technique vs. conventional technique in medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy: a prospective comparative study. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1923172. 10.1155/2020/1923172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaouche S, Jacquet C, Fabre‐Aubrespy M, Sharma A, Argenson JN, Parratte S, et al. Patient‐specific cutting guides for open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy: safety and accuracy analysis of a hundred patients continuous cohort. Int Orthop. 2019;43:2757–2765. 10.1007/s00264-019-04372-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacquet C, Chan‐Yu‐Kin J, Sharma A, Argenson JN, Parratte S, Ollivier M. More accurate correction using "patient‐specific" cutting guides in opening wedge distal femur varization osteotomies. Int Orthop. 2019;43:2285–2291. 10.1007/s00264-018-4207-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goshima K, Sawaguchi T, Sakagoshi D, Shigemoto K, Hatsuchi Y, Akahane M. Age does not affect the clinical and radiological outcomes after open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:918–923. 10.1007/s00167-015-3847-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yabuuchi K, Kondo E, Kaibara T, Onodera J, Iwasaki K, Matsuoka M, et al. Effect of patient age on clinical and radiological outcomes after medial open‐wedge high Tibial osteotomy: a comparative study with 344 knees. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11:961805283. 10.1177/23259671231200227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ding T, Tan Y, Tian X, Xue Z, Ma S, Hu Y, et al. Patellar height after high Tibial osteotomy of the distal Tibial tuberosity: a retrospective study of age stratification. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:7193902. 10.1155/2022/7193902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Genin P, Weill G, Julliard R. La pente tibiale. Proposition pour une méthode de mesure [The tibial slope. Proposal for a measurement method]. J Radiol. 1993;74(1):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Longino PD, Birmingham TB, Schultz WJ, Moyer RF, Giffin JR. Combined tibial tubercle osteotomy with medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy minimizes changes in patellar height: a prospective cohort study with historical controls. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2849–2857. 10.1177/0363546513505077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shim JS, Lee SH, Jung HJ, Lee HI. High tibial open wedge osteotomy below the tibial tubercle: clinical and radiographic results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:57–63. 10.1007/s00167-011-1453-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bito H, Takeuchi R, Kumagai K, Aratake M, Saito I, Hayashi R, et al. Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy affects both the lateral patellar tilt and patellar height. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:955–960. 10.1007/s00167-010-1077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang JH, Lee SH, Nathawat KS, Jeon SH, Oh KJ. The effect of biplane medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy on patellofemoral joint indices. Knee. 2013;20:128–132. 10.1016/j.knee.2012.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee YS, Lee SB, Oh WS, Kwon YE, Lee BK. Changes in patellofemoral alignment do not cause clinical impact after open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:129–133. 10.1007/s00167-014-3349-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bin SI, Kim HJ, Ahn HS, Rim DS, Lee DH. Changes in patellar height after opening wedge and closing wedge high Tibial osteotomy: a meta‐analysis. Art Ther. 2016;32:2393–2400. 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chae DJ, Shetty GM, Lee DB, Choi HW, Han SB, Nha KW. Tibial slope and patellar height after opening wedge high tibia osteotomy using autologous tricortical iliac bone graft. Knee. 2008;15:128–133. 10.1016/j.knee.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Esenkaya I, Unay K. Proximal medial tibial biplanar retrotubercle open wedge osteotomy in medial knee arthrosis. Knee. 2012;19:416–421. 10.1016/j.knee.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Javidan P, Adamson GJ, Miller JR, Durand P Jr, Dawson PA, Pink MM, et al. The effect of medial opening wedge proximal tibial osteotomy on patellofemoral contact. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:80–86. 10.1177/0363546512462810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Otakara E, Nakagawa S, Arai Y, Inoue H, Kan H, Nakayama Y, et al. Large deformity correction in medial open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy may cause degeneration of patellofemoral cartilage: a retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14299. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanaka T, Matsushita T, Miyaji N, Ibaraki K, Nishida K, Oka S, et al. Deterioration of patellofemoral cartilage status after medial open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1347–1354. 10.1007/s00167-018-5128-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Song SJ, Yoon KH, Park CH. Patellofemoral cartilage degeneration after closed‐ and open‐wedge high Tibial osteotomy with large alignment correction. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48:2718–2725. 10.1177/0363546520943872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bae DK, Song SJ, Kim HJ, Seo JW. Change in limb length after high tibial osteotomy using computer‐assisted surgery: a comparative study of closed‐ and open‐wedge osteotomies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(1):120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ducat A, Sariali E, Lebel B, Mertl P, Hernigou P, Flecher X, et al. Posterior tibial slope changes after opening‐ and closing‐wedge high tibial osteotomy: a comparative prospective multicenter study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:68–74. 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. El‐Azab H, Halawa A, Anetzberger H, Imhoff AB, Hinterwimmer S. The effect of closed‐ and open‐wedge high tibial osteotomy on tibial slope: a retrospective radiological review of 120 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(9):1193–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schaefer TK, Majewski M, Hirschmann MT, Friederich NF. Comparison of sagittal and frontal plane alignment after open‐ and closed‐wedge osteotomy: a matched‐pair analysis. J Int Med Res. 2008;36(5):1085–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hoell S, Suttmoeller J, Stoll V, Fuchs S, Gosheger G. The high tibial osteotomy, open versus closed wedge, a comparison of methods in 108 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125(9):638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ji S, Gao Y, Zhang J, Pan F, Zhu K, Jiang X, et al. High tibial lateral closing wedge and opening wedge valgus osteotomy produce different effects on posterior tibial slope and patellar height. Front Surg. 2023;10:1219614. 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1219614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sahanand KS, Pandian P, Chellamuthu G, Rajan DV. Effect of ascending and descending medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy on patella height and functional outcomes—a retrospective study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2023;34:499–505. 10.1007/s00590-023-03693-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Laprade RF, Oro FB, Ziegler CG, Wijdicks CA, Walsh MP. Patellar height and tibial slope after opening‐wedge proximal tibial osteotomy: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:160–170. 10.1177/0363546509342701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Weale AE. The length of the patellar tendon after unicompartmental and total knee replacement. Murray DW. Ackroyd CE: Newman JH; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hinterwimmer S, Beitzel K, Paul J, Kirchhoff C, Sauerschnig M, von Eisenhart‐Rothe R, et al. Control of posterior tibial slope and patellar height in open‐wedge valgus high tibial osteotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:851–856. 10.1177/0363546510388929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kyung HS, Lee BJ, Kim JW, Yoon SD. Biplanar open wedge high Tibial osteotomy in the medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee joint: comparison between the Aescula and TomoFix plate. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7:185–190. 10.4055/cios.2015.7.2.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Savarese E, Bisicchia S, Romeo R, Amendola A. Role of high tibial osteotomy in chronic injuries of posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:1–17. 10.1007/s10195-010-0120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]