Abstract

Background

Invasive aspergillosis is a severe fungal infection that affects multiple organ systems including the CNS and the lungs. Isavuconazole, a novel triazole antifungal agent, has demonstrated promising activity against Aspergillus spp. However, data on the penetration of isavuconazole into the CNS and ELF and intracellular accumulation remain limited.

Materials and methods

We conducted a prospective single-centre pharmacokinetic (PK) study in 12 healthy volunteers. Subjects received seven doses of 200 mg isavuconazole to achieve an assumed steady-state. After the first and final infusion, plasma sampling was conducted over 8 and 12 h, respectively. All subjects underwent one lumbar puncture and bronchoalveolar lavage, at either 2, 6 or 12 h post-infusion of the final dose. PBMCs were collected in six subjects from blood to determine intracellular isavuconazole concentrations at 6, 8 or 12 h. The AUC/MIC was calculated for an MIC value of 1 mg/L, which marks the EUCAST susceptibility breakpoint for Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus.

Results

C max and AUC0-24h of isavuconazole in plasma under assumed steady-state conditions were 6.57 ± 1.68 mg/L (mean ± SD) and 106 ± 32.1 h·mg/L, respectively. The average concentrations measured in CSF, ELF and in PBMCs were 0.07 ± 0.03, 0.94 ± 0.46 and 27.1 ± 17.8 mg/L, respectively. The AUC/MIC in plasma, CSF, ELF and in PBMCs under steady-state conditions were 106 ± 32.1, 1.68 ± 0.72, 22.6 ± 11.0 and 650 ± 426 mg·h/L, respectively.

Conclusion

Isavuconazole demonstrated moderate penetration into ELF, low penetrability into CSF and high accumulation in PBMCs. Current dosing regimens resulted in sufficient plasma exposure in all subjects to treat isolates with MICs ≤ 1 mg/L.

Introduction

Aspergillosis is a severe and often fatal infection caused by Aspergillus fungi.1 Treating this infection is particularly challenging due to its ability to affect multiple organ systems, including the CNS and the lungs.2 Aspergillosis poses a significant public health threat, especially among immunocompromised individuals and patients receiving intensive care, with mortality rates surpassing 50%.3–5

Currently, effective treatment options available for aspergillosis are limited. Current treatments include azoles, echinocandins and polyenes, but their usefulness is limited by toxicity, drug interactions and poor penetration into infected tissues.6–8

Isavuconazole is a novel triazole antifungal agent that has demonstrated promising activity against aspergillosis in vitro and in vivo.9–11 In preclinical studies it has also shown good penetration into both lung and brain tissue, indicating its potential as a viable option for treating aspergillosis in the lung and brain.12

Nevertheless, the extent of isavuconazole penetration into the CNS and the ELF and its intracellular accumulation remain poorly elucidated. This is an important consideration, since the treatment’s capacity to reach these areas is crucial for its effectiveness.

The objective of this study was to investigate the single-dose and steady-state pharmacokinetics (PK) of isavuconazole in healthy volunteers, as well as its ability to reach the CNS and ELF, and to investigate its intracellular accumulation in PBMCs. These data are important to evaluate the potential of isavuconazole for treatment of aspergillosis in the brain and lungs.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The study was conducted at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines of the International Conference of Harmonization. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK-1704/202) and the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety and was registered under the EudraCT number 2020-002709-24. All subjects gave written and oral consent before inclusion.

Clinical trial design and study population

The present study was a prospective, single-centre pharmacokinetic study in 12 healthy volunteers. Isavuconazole concentrations were measured in plasma, following a single intravenous dose and at an assumed steady state, and in CSF and ELF under assumed steady-state conditions. Furthermore, intracellular concentrations in PBMCs were determined after multiple-dose infusions.

A screening visit took place within 14 days before the first study day. Before enrolment, subjects were informed about the objective and procedures of the study and any associated risks. Demographic data and medical history including any concurrent diseases and medication, weight, height and vital signs were recorded. Blood was collected for laboratory testing, including HIV and hepatitis B and C, and urine pregnancy tests were conducted for all female subjects.

Main inclusion criteria comprised healthy men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 with a BMI between 19 and 30 kg/m2. Key exclusion criteria included allergy or hypersensitivity to any ingredients contained in the study medication, use of any prescription or non-prescription drugs, especially antibiotics and antimycotics, within 7 days before receiving the study drug, abnormal physical examination or laboratory results, any contraindication to receiving a lumbar puncture, or any acute or chronic illnesses considered clinically significant by the investigator. A final examination, which included the same procedures as the screening visit, was conducted 10 ± 1 days after the last administration of the study drug. All adverse events occurring during the study were recorded.

Study medication

Intravenous isavuconazole (Cresemba®, Pfizer Corporation Austria GmbH, Vienna, Austria) infusions were prepared according to the Summary of Product Characteristics.13 All subjects received a total of seven intravenous doses of 200 mg isavuconazole over 2 h. The first six loading doses were administered at an interval of 8 h and a single maintenance dose was administered 12 h after the last loading dose. This is in line with the recommended maintenance dose of 200 mg of isavuconazole once daily, starting 12 to 24 h after the last loading dose.13

Plasma sampling

On study day 1, two peripheral venous catheters were placed into either antecubital vein of each arm. One catheter was used to administer the study medication, while the other one was used for plasma sampling. Plasma samples were collected at baseline (before the first drug administration), 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 h after the start of the first infusion. In addition, further plasma samples were collected before and 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 240 h after the start of the seventh drug administration (i.e. the start of the first maintenance dose). Approximately 6 mL of venous blood was collected in lithium heparin tubes (Vacuette® lithium heparin) at each sampling time point. Venous catheters were rinsed with 0.9% physiological saline solution after each blood draw. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4°C and 2600 g for 10 min, within 15 min of sampling. Supernatant plasma was divided into two aliquots of approximately 1–2 mL and snap frozen at −20°C. Samples were transferred to −80°C by the end of the study day where they were stored until analysis.

Cerebrospinal fluid sampling

All subjects were equally assigned to undergo one lumbar puncture at either 2, 6 or 12 h after the start of the last drug infusion to obtain CSF samples. First, the lower back of the volunteers was disinfected. To reduce pain and discomfort caused by the insertion of the spinal needle, a 2% lidocaine solution was applied as local anaesthetic. A spinal needle was inserted into the lumbar spinal canal. Approximately 3 mL of CSF were collected in pre-cooled tubes (Vacuette® Z without addition). Subjects were instructed to rest in a lying position for at least half an hour to reduce the risk or the intensity of post puncture headache. All lumbar punctures were conducted by a board-certified neurologist. Samples were centrifuged within 30 min at 4°C and 2600 g for 10 min and divided into two equal aliquots snap frozen at −20°C. Samples were transferred to −80°C by the end of the study day and stored until analysis.

Epithelial lining fluid sampling

All subjects were assigned to undergo bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at either 2, 6 or 12 h after the start of the last drug infusion to obtain ELF samples. The allocation of time points was managed in a manner where interventions (i.e. either BAL or lumbar puncture) were not conducted simultaneously. A total of four samples were collected for all time points. Patients were advised to fast at least 6 h before the bronchoscopy.

In brief, subjects were placed in supine position with continuous monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, cardiac rhythm, respiratory rate and pulse oximetry. Patients were sedated with propofol under close monitoring of vital signs. Subsequently, after inspection of airways, a bronchoscope was wedged at the right or left lower lobe at the segments B8-B10. One 20 mL aliquot of saline was injected and subsequently gently recollected. All BALs were conducted by pulmonologists. The retrieved lavage fluid was gently mixed and filtered through a sterile gauze filter and then centrifuged at 4°C and 2600 g for 10 min. The supernatant was divided into two equal aliquots snap frozen at −20°C. Samples were transferred to −80°C by the end of the study day and stored until analysis.

Urea was measured in corresponding plasma and BAL fluid samples using the Abnova Urea Assay Kit, which used the modified Jung method. The concentration of isavuconazole in the ELF was calculated by the urea diffusion method, using urea as an endogenous marker, as described elsewhere.14

Isolation of PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from the blood of six healthy volunteers. Two samples each were collected in Vacutainer® Cellular Preparation Tubes at 6, 8 and 12 h after the start of the last infusion. PBMCs were isolated through centrifugation, and manually counted using trypan blue staining. To obtain the average concentration of isavuconazole in PBMCs, the concentration measured in the sample was corrected for the total cell count and the cell volume as previously described.15

Sample analysis

Isavuconazole and d4-isavuconazole were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Plasma, CSF, ELF and PBMC sample concentrations were analysed by LC–MS/MS.

The LC–MS/MS method was validated according to the EMA guideline16 using LiHep plasma for the preparation of calibrators and quality controls (QC). Selectivity, carry over, lower limit of quantification, accuracy, precision, dilution integrity, matrix effect and stability (short term temperature-, long term temperature-, freeze–thaw cycle- and autosampler-stability) were investigated; all acceptance criteria were met. For the analysis of CSF and ELF samples, extra QCs were prepared using baseline samples (containing no analytes) and analysed against the plasma calibration curve. Accuracies for low QC, medium QC and high QC were 142, 94 and 92% for CSF, and 97, 83 and 82% for ELF, respectively.

Next, 25 µL of the sample material was spiked with 10 µL of internal standard solution (2.5 µg d4-isavuconazole/mL water); 200 µL of acetonitrile were added, vortexed and centrifuged at 20.800 g. Finally, 25 µL of supernatant were transferred into a LC-vial, diluted with a mixture of 800 µL of water and 600 µL of acetonitrile and injected into the LC system.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

PK outcome variables included the AUC0-24 and Cmax in plasma and Caverage in CSF, ELF and in PBMCs, the estimated AUC0-24 in CSF, ELF and in PBMCs under assumed steady-state conditions, the AUC0-8 and Cmax in plasma after a single intravenous infusion, and the t1/2, tmax, CL and volume of distribution (Vd) under assumed steady-state conditions in plasma. AUCs were calculated using the trapezoidal method. Plasma AUC0–24 was determined by extrapolation from 12 to 24 hours using the individually estimated terminal elimination rate constants, which were determined based on the 12 and 240 h time points of each subject. PK parameters were determined by non-compartmental analysis (NCA) using Phoenix WinNonLin, Certara, USA.

PK/PD and statistical analysis

The PK/PD index that correlates best with the effect of isavuconazole is AUC0-24/MIC. In an infection model with immunocompetent mice with invasive aspergillosis, in vivo efficacy was tested against four clinical A. fumigatus isolates. Here, plasma AUC0-24/MIC values of 24.7 and 33.4 were associated with 50% and 90% survival, respectively.17,18 AUC/MIC ratios were calculated for a MIC value of 1 mg/L, which is the EUCAST susceptibility breakpoint for Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus.19

Results

A total of 12 subjects were included in the analysis. One subject completed plasma sampling but did not undergo lumbar puncture at the 12 h time point. One subject dropped out of the study after single-dose sampling and was replaced with a new subject. Single-dose data of the dropped-out subject was incorporated into the analysis. Table 1 provides an overview of the subject characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristic of the study population (n = 12)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Sex, male | 9 (75) |

| Age, years | 28.5 (24–36) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 (2.6) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 12 (100) |

| Laboratory parameters | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 43.9 (2.9) |

| eGFRa (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 108.2 (11.2) |

| AE | |

| Mild | 26 (86.7) |

| Moderate | 4 (13.3) |

Data are shown as n (%), mean (SD) or median (IQR).

aEstimated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.

Since there were no clear observable kinetic patterns in the concentration-time profiles of CSF, ELF and PBMCs, the average of all observations was calculated and multiplied by 24 to determine an AUC0-24. Concentrations measured under steady-state conditions were lowest in CSF (0.07 ± 0.03 mg/L, average ± SD), followed by ELF (0.94 ± 0.46 mg/L) and PBMCs (27.1 ± 17.8 mg/L). The estimated AUC0-24 in CSF, ELF and in PBMCs under steady-state conditions was 1.68 ± 0.72, 22.6 ± 11.0 and 650 ± 427 mg·h/L, respectively.

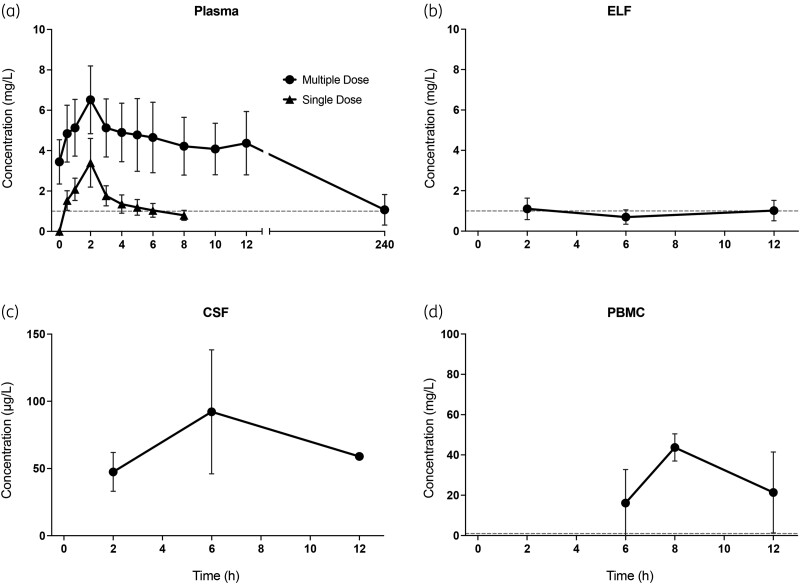

The pharmacokinetic parameters of isavuconazole in plasma, CSF, ELF and PBMC after single-dose infusion and under steady-state conditions, calculated by NCA, are summarized in Table 2. Cmax and AUC0-8 of isavuconazole in plasma after single-dose infusion were 3.3 ± 0.65 mg/L (mean ± SD) and 12.4 ± 3.57 mg·h/L, respectively. The drug's prolonged elimination half-life and limited sampling time period prevented the determination of t1/2, Vd, or CL following a single-dose administration. Cmax and AUC0-24 of isavuconazole in plasma under steady-state conditions were 6.57 ± 1.68 mg/L (mean ± SD) and 106 ± 32.1 mg·h/L, respectively. Figure 1 depicts the single-dose and steady-state concentration-time profiles. An increase in plasma concentrations was observed at the end of the steady-state sampling interval. The AUC0-24/MIC in plasma under steady-state conditions was 106 for an MIC of 1 mg/L.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters (mean ± SD values)

| Plasma single dose | Plasma multiple dose | CSF | ELF | PBMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C max (mg/L) | 3.3 ± 0.65 | 6.57 ± 1.68 | |||

| C average(mg/L) | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.46 | 27.1 ± 17.8 | ||

| AUC0-8/0-24 (mg·h/L)a | 12.4 ± 3.57 | 106 ± 32.1 | 1.68 ± 0.72b | 22.6 ± 11.0b | 650 ± 427b |

| AUC/MICc | 12.4 ± 3.57 | 106 ± 32.1 | 1.68 ± 0.72b | 22.56 ± 11.04b | 650 ± 427b |

| t max (h) | 2 | 2.83 ± 2.89 | |||

| t 1/2 (h) | d | 172 ± 170 | |||

| CL (L/h) | d | 2.13 ± 0.96 | |||

| V d (L) | d | 628 ± 776 |

aAUC0-8 refers to plasma concentrations after single dose, AUC0-24 refers to plasma concentrations after multiple dose; blank cells indicate that the parameter was not calculated.

bEstimated AUC0-24 based on extrapolation of Caverage.

cCalculated for a MIC value of 1 mg/L.

dNot calculated due to the drug's prolonged elimination half-life; ELF, epithelial lining fluid.

Figure 1.

Concentration-time profiles (mean ± SD) after single and multiple-dose infusion, i.e. assumed steady state, in (a) plasma, and after multiple-dose infusion, in (b) ELF, (c) CSF and (d) PBMCs. ELF, epithelial lining fluid. The dashed horizontal lines represent an MIC of 1; Of note, the units of the y-axes are not uniform for all plots.

A total of 48 adverse events (AE) were observed, of which 31 were considered probably or possibly related to or related to the study drug. The most common reactions were irritation at the infusion site [11 of 12 (91.7%)] and headache [5 of 12 (41.7%)]. One subject developed moderate thrombophlebitis at the injection site and required treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin. Most common AEs considered unrelated to the study drug were headache after lumbar puncture [6 of 12 (50%)] and pain at the lumbar puncture site [3 of 12 (25%)].

Discussion

Although notable progress has been made in the treatment of aspergillosis, current therapeutic options are limited in their effectiveness due to concerns related to toxicity, drug interactions and unknown penetrability into affected tissues.8 Isavuconazole offers a promising treatment option for aspergillosis. However, its penetrability into tissues typically affected by aspergillosis have yet to be fully elucidated. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the PK of isavuconazole in CSF and in PBMCs, and adds to the body of knowledge regarding its ability to distribute into the ELF.

There are few data on the penetration of isavuconazole into ELF, CSF and PBMCs, mostly limited to case reports and animal studies. A recent study investigated concentrations in the ELF of lung transplant recipients under steady-state conditions and reported mean concentrations of 0.97, 2.14 and 2.8 mg/L at 2, 4 and 24 h post-infusion, thus they were comparable to the ELF levels observed in the present study (average concentration of 0.94 mg/L).20

Quantification of drug concentrations in PBMCs may be used be used to determine drug distribution into mononuclear cells, most importantly alveolar macrophages.21 Previous studies have reported high penetrability of voriconazole into human polymorphonuclear leucocytes.22 Similarly, in the present study, isavuconazole showed intracellular accumulation in PBMCs, resulting in concentrations about 7-fold higher than those in plasma. High intracellular accumulation might aid in combating lung infections since these cells, particularly macrophages, are involved in the immune response and migrate to inflammation sites, thus acting as drug carriers.23

A case series by Davis et al. investigated isavuconazole for treatment of refractory coccidioidal meningitis.24 Surprisingly, despite undetectability in CSF samples obtained from extraventricular drains in all patients, isavuconazole concentrations were quantifiable in samples collected from lumbar puncture in two of three patients. CSF concentrations were measured as 0.69 and 1.72 mg/L at corresponding plasma concentrations of 1.8 and 5.63 mg/L, respectively. By contrast, we observed significantly lower mean CSF concentrations of 0.07 mg/L, i.e. approximately 100-fold lower than corresponding plasma levels and markedly below target AUC0-24/MIC values. However, CNS infections may increase drug permeability through the blood–brain barrier and concentrations may thus be higher in infected patients than in healthy volunteers.25 Rouzaud et al. provided data on intracranial isavuconazole concentrations in a patient with cerebral aspergillosis following a daily maintenance dosage of 300 mg.26 Although undetectable in CSF, isavuconazole concentrations were 0.4 mg/L in healthy brain tissue samples, 2.62 mg/L in inflamed dura mater and 5.11 mg/L within a fungal abscess at a corresponding plasma concentration of 4.3 mg/L. Furthermore, the case report by Lamoth et al. found a high brain to plasma concentration ratio of about 0.9 in a tissue biopsy 6 hours after the start of an assumed steady-state infusion in a patient with cerebral aspergillosis.27 This data indicates that brain tissue concentrations may exceed those measured in CSF at specific time points and that penetrability into the CNS may be higher in patients with CNS infections than in healthy volunteers.

Mean plasma concentrations measured in our study after single- and multiple-dose infusions align well with previously published data. Previous studies showed Cmax values of 2.2–5.4 and 3.6–11 mg/L after administration of 200 mg of isavuconazole as a single dose and multiple dose, respectively.28,29 Similarly, the AUC0-24 of 106 mg·h/L documented in the present study aligns well with values reported in previous literature.30 Substantial variability in isavuconazole PK has been observed in former studies.29–31 Our analysis revealed a considerable range of AUC0-24 values (41.5–158 mg·h/L). As depicted in Figure 1, an increase in plasma concentrations was observed approximately 10 h after the initiation of the last infusion, a phenomenon consistent with previous observations.28,29,32–34 This pattern may be associated with the process of enterohepatic reabsorption, where a drug is secreted into the intestinal lumen and subsequently reabsorbed into systemic circulation resulting in fluctuations, peaks and prolonged apparent half-life in pharmacokinetic profiles.35,36 Enterohepatic circulation of isavuconazole has been observed in studies in rats, and the EMA public assessment report on Cresemba® notes peaks in the plasma concentration-time profiles around 6–12 hours post-dose, possibly coinciding with meals.37

Previous studies investigating the in vivo efficacy of isavuconazole in an immunocompetent murine model of invasive aspergillosis against four clinical A. fumigatus isolates proposed total-drug AUC0-24/MIC values of 24.7 and 33.4 to achieve 50% and 90% survival rates (EI50/90).18 The AUC0-24/MIC in plasma under assumed steady-state conditions was 106 for an MIC of 1 mg/L, which is the EUCAST clinical breakpoint for Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus. The EI90 target value was attained in all subjects, suggesting adequate plasma exposure at assumed steady state using current dosing regimens. When considering the epidemiological cut-off of 2 mg/L, the EI90 target value was still achieved for 11 of the 12 subjects.19 AUC0-24/MIC values for ELF and PBMCs for an MIC value of 1 mg/L amounted to 22.6 and 650.4, respectively. Hence, the index value for ELF lies in the realm of the EI50 target and the index value for PBMCs greatly surpasses the EI90 target. By contrast, the PK/PD index value for CSF was below the EI50 target in all participants.

Isavuconazole was tolerated moderately well. Thirty-one AEs related or possibly related to the study drug were observed in 12 subjects. Reflecting the drug’s known adverse reactions, 11 of the 12 subjects experienced infusion site pain.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, plasma sampling under steady-state conditions did not include a 24 h time point post-dose, whereas the dosing interval for maintenance doses is once daily. Hence, the derived AUC0-24 values were computed using extrapolation. Additionally, owing to the pattern of increases and decreases within a single sampling interval, the long half-life of isavuconazole and the limited observation period, only the 12 and 240 h time points were used to determine the terminal half-life within our sample. Nevertheless, the observed half-life aligns with previously reported data.30 Third, translating data regarding isavuconazole’s penetration rate and absolute tissue concentrations from healthy subjects to critically ill patients with aspergillosis may be inappropriate and could yield unreliable results. Finally, due to feasibility constraints, drug concentrations in PBMCs were measured only in six subjects.

Conclusion

In summary, the currently recommended clinical dosing strategy involving six doses of 200 mg isavuconazole every eight hours, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 200 mg, resulted in adequate steady-state plasma exposure in healthy volunteers. Isavuconazole demonstrated moderate penetration into the ELF, whereas penetration into the CSF was notably low, with concentrations approximately 100-fold lower than in plasma. Conversely, isavuconazole exhibited significant accumulation in PBMCs, with concentrations about 7-fold higher than plasma levels. In the absence of specific PK/PD breakpoints for compartments other than plasma, further studies are warranted to optimize dosing regimens of isavuconazole in the treatment of pulmonary infections and to evaluate efficacy in the treatment of CNS infections.

Contributor Information

Felix Bergmann, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria; Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Michael Wölfl-Duchek, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria; Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Anselm Jorda, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Valentin Al Jalali, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Amelie Leutzendorff, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria; Department of Infectiology and Tropical Medicine, University Clinic of Internal Medicine I, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Maria Sanz-Codina, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Daniela Gompelmann, Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Karin Trimmel, Department of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Maria Weber, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Sabine Eberl, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Wisse Van Os, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Iris K Minichmayr, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Birgit Reiter, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Gürtel 18-20, Vienna, Austria.

Thomas Stimpfl, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Gürtel 18-20, Vienna, Austria.

Marco Idzko, Division of Pulmonology, Department of Internal Medicine II, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Markus Zeitlinger, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, 1090, Vienna, Austria.

Funding

This work was an investigator-initiated study and was supported by and received funding from Pfizer Inc. The design of the study, data collection and analysis, and preparation of the manuscript were performed by the investigators.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

F.B., M.W.D. and M.Z. designed the study. F.B., M.W.D., A.J., V.a.J., A.L., M.S.C., D.G., K.T., M.W., S.E., W.v.O., I.K.M., B.R., T.S., M.I. and M.Z. performed the study. B.R. and T.S. performed the sample analysis. F.B. and M.W.D. wrote the original draft of the manuscript and created the tables and figures. M.W. managed study documentation and material preparation. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication.

References

- 1. Brahm A, Segal H. Aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1870–84. 10.1056/NEJMra0808853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanaujia R, Singh S, Rudramurthy SM. Aspergillosis: an update on clinical spectrum, diagnostic schemes, and management. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2023; 17: 144–55. 10.1007/s12281-023-00461-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bergmann F, Jorda A, Blaschke A et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Fungi 2023; 9: 315. 10.3390/jof9030315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Latgé JP, Chamilos G. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis in 2019. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020; 33: e00140-18. 10.1128/CMR.00140-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beltrame A, Stevens DA, Haiduven D. Mortality in ICU patients with COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. J Fungi 2023; 9: 689. 10.3390/jof9060689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cadena J, Thompson GR, Patterson TF. Aspergillosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2021; 35: 415–34. 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aruanno M, Glampedakis E, Lamoth F. Echinocandins for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis: from laboratory to bedside. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e00399-19. 10.1128/AAC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyer J, Feys S, Zsifkovits I et al. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis: how it’s going, where it’s heading. Mycopathologia 2023; 188: 667–81. 10.1007/s11046-023-00727-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kohno S, Izumikawa K, Takazono T et al. Efficacy and safety of isavuconazole against deep-seated mycoses: a phase 3, randomized, open-label study in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2023; 29: 163–70. 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guinea J, Peláez T, Recio S et al. In vitro antifungal activities of isavuconazole (BAL4815), voriconazole, and fluconazole against 1,007 isolates of zygomycete, Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Scedosporium species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 1396–400. 10.1128/AAC.01512-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 760–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01159-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee A, Prideaux B, Lee MH et al. Tissue distribution and penetration of isavuconazole at the site of infection in experimental invasive aspergillosis in mice with underlying chronic granulomatous disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e00524-19. 10.1128/AAC.00524-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Medicines Agency . Cresemba, Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics. EMA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rennard SI, Basset G, O’donnell KM et al. Estimation of volume of epithelial lining fluid recovered by lavage using urea as marker of dilution. J Appl Physiol 1986; 60: 532–8. 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.2.532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nibbering PH, Zomerdijk TPL, Corsèl-Van Tilburg AJ et al. Mean cell volume of human blood leucocytes and resident and activated murine macrophages. J Immunol Methods 1990; 129: 143–5. 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90432-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) . Guideline on Bioanalytical Method Validation. EMA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buil JB, Brüggemann RJM, Wasmann RE et al. Isavuconazole susceptibility of clinical Aspergillus fumigatus isolates and feasibility of isavuconazole dose escalation to treat isolates with elevated MICs. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 134–42. 10.1093/jac/dkx354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seyedmousavi S, Brüggemann RJM, Meis JF et al. Pharmacodynamics of isavuconazole in an Aspergillus fumigatus mouse infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 2855–66. 10.1128/AAC.04907-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anon . Isavuconazole: Rationale for EUCAST Clinical Breakpoints, Current Version 2.0 4. 2020. Available at: http://www.eucast.org.

- 20. Caballero-Bermejo AF, Darnaude-Ximénez I, Aguilar-Pérez M et al. Bronchopulmonary penetration of isavuconazole in lung transplant recipients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023; 67: e0061323. https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/aac.00613-23. 10.1128/aac.00613-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Motta I, Calcagno A, Baietto L et al. Pharmacokinetics of first-line antitubercular drugs in plasma and PBMCs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 83: 1146–8. 10.1111/bcp.13196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ballesta S, García I, Perea EJ et al. Uptake and intracellular activity of voriconazole in human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 55: 785–7. 10.1093/jac/dki075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liang T, Zhang R, Liu X et al. Recent advances in macrophage-mediated drug delivery systems. Int J Nanomedicine 2021; 16: 2703–14. 10.2147/IJN.S298159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davis MR, Chang S, Gaynor P et al. Isavuconazole for treatment of refractory coccidioidal meningitis with concomitant cerebrospinal fluid and plasma therapeutic drug monitoring. Med Mycol 2021; 59: 939–42. 10.1093/mmy/myab035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010; 23: 858–83. 10.1128/CMR.00007-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rouzaud C, Jullien V, Herbrecht A et al. Isavuconazole diffusion in infected human brain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e02474-18. 10.1128/AAC.02474-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lamoth F, Mercier T, André P et al. Isavuconazole brain penetration in cerebral aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 1751–3. 10.1093/jac/dkz050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cornely OA, Böhme A, Schmitt-Hoffmann A et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole as antifungal prophylaxis in acute myeloid leukemia patients with neutropenia: results of a phase 2, dose escalation study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 2078–85. 10.1128/AAC.04569-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu X, Clancy CJ, Rivosecchi RM et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous isavuconazole in solid-organ transplant recipients. Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy 2018; 62: e01643-18. 10.1128/AAC.01643-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Desai A, Kovanda L, Kowalski D et al. Population pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole from phase 1 and phase 3 (SECURE) trials in adults and target attainment in patients with invasive infections due to Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 5483–91. 10.1128/AAC.02819-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kovanda LL, Desai AV, Lu Q et al. Isavuconazole population pharmacokinetic analysis using nonparametric estimation in patients with invasive fungal disease (results from the VITAL study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4568–76. 10.1128/AAC.00514-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shirae S, Ose A, Kumagai Y. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of single and multiple doses of isavuconazonium sulfate in healthy adult Japanese subjects. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2022; 11: 744–53. 10.1002/cpdd.1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Desai A, Helmick M, Heo N et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of isavuconazole administered as isavuconazonium sulfate intravenous solution via nasogastric tube or orally in healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021; 65: e0044221. 10.1128/AAC.00442-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Townsend RW, Akhtar S, Alcorn H et al. Phase I trial to investigate the effect of renal impairment on isavuconazole pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017; 73: 669–78. 10.1007/s00228-017-2213-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ibarra M, Trocóniz IF, Fagiolino P. Enteric reabsorption processes and their impact on drug pharmacokinetics. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 5794. 10.1038/s41598-021-85174-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roberts MS, Magnusson BM, Burczynski FJ et al. Enterohepatic circulation physiological, pharmacokinetic and clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002; 41: 751–90. 10.2165/00003088-200241100-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) . Cresemba, Assessment Report. EMA, 2015. [Google Scholar]