Abstract

Background

Pharmacokinetic data on high-dose isoniazid for the treatment of rifampicin-/multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (RR/MDR-TB) are limited. We aimed to describe the pharmacokinetics of high-dose isoniazid, estimate exposure target attainment, identify predictors of exposures, and explore exposure–response relationships in RR/MDR-TB patients.

Methods

We performed an observational pharmacokinetic study, with exploratory pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analyses, in Indonesian adults aged 18–65 years treated for pulmonary RR/MDR-TB with standardized regimens containing high-dose isoniazid (10–15 mg/kg/day) for 9–11 months. Intensive pharmacokinetic sampling was performed after ≥2 weeks of treatment. Total plasma drug exposure (AUC0–24) and peak concentration (Cmax) were assessed using non-compartmental analyses. AUC0–24/MIC ratio of 85 and Cmax/MIC ratio of 17.5 were used as exposure targets. Multivariable linear and logistic regression analyses were used to identify predictors of drug exposures and responses, respectively.

Results

We consecutively enrolled 40 patients (median age 37.5 years). The geometric mean isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax were 35.4 h·mg/L and 8.5 mg/L, respectively. Lower AUC0–24 and Cmax values were associated (P < 0.05) with non-slow acetylator phenotype, and lower Cmax values were associated with male sex. Of the 26 patients with MIC data, less than 25% achieved the proposed targets for isoniazid AUC0–24/MIC (n = 6/26) and Cmax/MIC (n = 5/26). Lower isoniazid AUC0–24 values were associated with delayed sputum culture conversion (>2 months of treatment) [adjusted OR 0.18 (95% CI 0.04–0.89)].

Conclusions

Isoniazid exposures below targets were observed in most patients, and certain risk groups for low isoniazid exposures may require dose adjustment. The effect of low isoniazid exposures on delayed culture conversion deserves attention.

Introduction

In 2021, the WHO estimated that there were 450 000 new cases of rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB) plus multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), defined as a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin. Only about one-third of new RR/MDR-TB cases were treated, with a success rate of 60% globally.1 Furthermore, the mortality rate is high (∼14%) among those treated for MDR-TB.2 These figures reflect complex patient pathways with diagnostic and treatment delays in health systems,3 the lack of access to effective drugs especially in low- and middle-income countries,4 and the long duration of conventional treatment with second-line drugs, which are less effective and more toxic than first-line drugs for drug-susceptible TB (DS-TB).2 Fortunately, the treatment of RR/MDR-TB is being optimized, now with the availability of a 6 month standardized all-oral regimen comprising bedaquiline, pretomanid and linezolid with or without moxifloxacin, a 9–11 month standardized all-oral bedaquiline-containing regimen, or longer individualized treatment regimens for 18–24 months.5 Yet, to prevent and overcome the threat of drug resistance, it remains important to keep on optimizing the dosing and application of existing antimycobacterial agents.6

Isoniazid (standard adult dose 5 mg/kg/day) is a cornerstone of anti-TB therapy because of its strong early bactericidal activity.7 High-dose isoniazid at 10–15 mg/kg/day is currently included by the WHO in a 9–11 month standard treatment regimen for RR/MDR-TB,8 which consists of bedaquiline, moxifloxacin, clofazimine, high-dose isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and ethionamide. The inclusion of high-dose isoniazid in this shorter treatment regimen assumes that it may be effective on M. tuberculosis strains with low- to medium-level resistance due to mutations in the inhA gene. On the other hand, high-level resistance due to a mutation in the katG gene cannot be overcome by high-dose isoniazid,9 but can be treated with ethionamide, which is the rationale for including both high-dose isoniazid and ethionamide in this standard regimen. Clinical evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the use of high-dose isoniazid for the treatment of MDR-TB, as it improves time to sputum culture conversion,10 early bactericidal activity11,12 and radiological features,10 especially among those with low- to medium-level resistance. In observational cohort studies, the use of shorter treatment regimens containing high-dose isoniazid for MDR-TB was associated with high treatment success rates (88%–89%).13–15

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of isoniazid at higher than standard doses and in the context of regimens used to treat RR/MDR-TB have not been fully characterized. Only a few studies have been performed to assess the PK of high-dose isoniazid for the treatment of RR/MDR-TB, either in adults12,16 or in children.17 In addition, data on the relationships between isoniazid concentrations at higher doses and treatment responses in RR/MDR-TB are limited. In this context, we aimed to describe the PK and exposure target attainment of high-dose isoniazid, and to explore the relationships between isoniazid exposures and treatment responses, including time to sputum culture conversion and end-of-treatment outcomes.

Patients and methods

Study setting and management of MDR-TB

The study was conducted at Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia, a referral hospital for patients with complex TB disease, including RR/MDR-TB. At this centre, all patients with possible MDR-TB underwent initial screening, which included physical and clinical examinations, medical history, blood biochemistry and haematology measurements, HIV testing, chest radiography and microbiological examinations. These included Xpert MTB/RIF assay, sputum smear microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB, at least grade 1+) using Ziehl-Neelsen staining, and culture for M. tuberculosis in liquid medium (BACTEC MGIT-960) along with drug susceptibility testing. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of isoniazid were determined phenotypically with the Sensititre MYCOTB plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the results were classified as low-, moderate- and high-level resistance for MICs of <1, 1.0–4.0 and >4.0 mg/L, respectively.18

Following confirmation of rifampicin resistance by Xpert MTB/RIF assay, all patients initiated RR/MDR-TB treatment with the standard 9–11 month regimen containing high-dose isoniazid as recommended by the WHO and national guidelines,8,19 pending phenotypic drug-susceptibility testing results. These patients received seven drugs, including bedaquiline (400 mg daily for the first 2 weeks followed by 200 mg three times per week), moxifloxacin (400 or 600 mg/day), clofazimine (100 mg/day), high-dose isoniazid (10–15 mg/kg/day), pyrazinamide (20–30 mg/kg/day), ethambutol (15–25 mg/kg/day) and ethionamide (15–20 mg/kg/day) for 4–6 months in the intensive phase, and then moxifloxacin, clofazimine, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for 5 months in the continuation phase.8,19 For a few patients who were diagnosed in 2020, when WHO recommendations to use all-oral treatment regimens for MDR-TB had not been incorporated into national guidelines in Indonesia, initial treatment included injectable kanamycin (15–20 mg/kg/day) instead of oral bedaquiline, with the same treatment duration of 9–11 months. All anti-TB drugs were WHO-prequalified from different manufacturers (e.g. Macleods for isoniazid). The drugs were taken under direct observation by family members or designated individuals, and treatment adherence was monitored by pill counts by the treating physicians/nurses during monthly follow-up visits.

Based on national and local guidelines, patients did not receive the high-dose isoniazid-containing regimen if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, HIV positive, had baseline alanine/aspartate aminotransferase (ALT/AST) > 5× the upper limit of normal (reference ranges for ALT: 16–63 U/L; and AST: 15–37 U/L), or if they had an estimated baseline glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Furthermore, if resistance to high-dose isoniazid was noted on drug-susceptibility testing (after 4–6 weeks of treatment), the initial treatment could be changed to an individualized regimen, without high-dose isoniazid, for 18–24 months,8,19 at the discretion of the treating physician.

PK study design and population

We performed a prospective observational PK study, with exploratory pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses among adults aged 18–65 years with pulmonary RR/MDR-TB diagnosed between August 2020 and January 2022 and treated with the standard regimen containing high-dose isoniazid. This study was reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia (approval number: 112/UN6.KEP/EC/2020). All eligible patients who provided written informed consent were consecutively enrolled in this study.

PK assessments

PK sampling was performed after ≥2 weeks of treatment. Prior to PK sampling, patients were allowed to have a light breakfast. Serial venous blood sampling using an indwelling catheter was performed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 8 h after directly observed dosing. Bioanalysis of isoniazid was performed at the Pharmacokinetic Laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universitas Padjadjaran using a validated UPLC method.20,21 PK parameters of isoniazid were assessed non-compartmentally with the PKNCA package (version 0.9.5) in RStudio for macOS. Main PK measures included area under the plasma concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h after dosing (AUC0–24) and peak concentration (Cmax).22 AUC0–24 was calculated based on the linear-up/log-down trapezoidal method. Cmax and the corresponding time to Cmax (Tmax) were derived directly from the concentration–time observations. Concentrations below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) before Tmax and the first LLOQ value after Tmax were set at half the LLOQ, with subsequent values estimated based on the first-order elimination rate constant. Detailed PK assessments are given in Appendix 1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online. Acetylator status was defined phenotypically based on isoniazid elimination half-life (t½), in which patients were categorized as slow (t½ > 2.2 h) and non-slow (combined rapid and intermediate; t½ ≤ 2.2 h) acetylator phenotypes.23

Follow-up and outcomes

Routine assessments during monthly follow-up visits included anthropometry, vital signs, blood biochemistry, haematology, smear microscopy and mycobacterial culture. Additional examinations, such as chest radiography and echocardiography were performed, if necessary. The safety endpoint included severe adverse events judged by attending physicians to be related to treatment, defined as any unwanted event that occurred after administration of at least one dose of the study drugs, and scored as grade 3–5 according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0).24 Efficacy endpoints included time to culture conversion and end-of-treatment outcomes. Sputum culture conversion was defined as at least two consecutive negative cultures with a positive baseline culture, collected at least 1 month apart. Delayed culture conversion was defined as a culture conversion after taking >2 months of treatment.25 End-of-treatment outcomes included cure, treatment completion, treatment failure, death and loss to follow-up, as defined by standard WHO guidelines.26

Statistical analysis

The current study was part of an ongoing descriptive PK study of clofazimine in RR/MDR-TB patients in Indonesia that included 40 patients. Of note, previous PK studies among DS-TB patients in Indonesia indicated that a minimum of 20 patients was sufficient to describe isoniazid PK,20,27 although in these studies acetylation status was not taken into account in the sample size calculation. Isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax values were log-transformed prior to statistical analyses. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between log-transformed AUC0–24 and Cmax. We assessed predictors of log-transformed AUC0–24 and Cmax using multivariable linear regression analyses, adjusted for dose and acetylator phenotype, and completed the models with variables having a P value of <0.2 in the univariable analysis. Given the small sample size of patients, only a maximum of four explanatory variables were included in the multivariable linear regression models. The overall AUC0–24 and Cmax estimates for high-dose isoniazid in this study were compared with the overall estimates for standard-dose isoniazid previously reported in Indonesian adults with DS-TB (AUC0–24: 15.6–16.4 h·mg/L; and Cmax: 4.5 mg/L).27,28 Next, considering isoniazid PK values associated with 90% of the maximum early bactericidal activity achieved in pulmonary DS-TB patients (AUC 10.5 h·mg/L and Cmax 2.19 mg/L),29 and assuming an MIC of ≤0.125 mg/L for DS-TB with WT distributions, an AUC0–24/MIC target of 85 and Cmax/MIC target of 17.5 were used.30 The proportion of patients achieving these PK/PD targets was assessed. The effects of isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax on delayed sputum culture conversion, treatment failure and unfavourable outcome (combined death, treatment failure and loss to follow-up) were assessed using multivariable logistic regression analyses. Due to the small sample size, our multivariable logistic regression models were adjusted for only three variables with a P value of <0.2 in the univariable analysis. All data were analysed in R for macOS (version 4.3.0), and statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 40 HIV-negative patients included in this study, 21 (52.5%) were male, 9 (22.5%) had diabetes mellitus, 27 (67.5%) had a low BMI, 4 (10.0%) had pulmonary cavities, 33 (82.5%) were treated with an all-oral bedaquiline-containing regimen, and 7 (17.5%) were treated with a regimen containing injectable kanamycin. The median (IQR) isoniazid dose was 11.2 (10.4–11.9) mg/kg (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of RR/MDR-TB patients included in high-dose isoniazid PK study

| Characteristics | Total (n = 40) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 37.5 (29.0–52.2) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 21 (52.5) |

| Body weight, kg, median (IQR) | 44.5 (41.0–52.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus comorbidity, n (%) | 9 (22.5) |

| Nutritional status, n (%) | |

| Normal weight (BMI ≥18.5) | 13 (32.5) |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 27 (67.5) |

| Pulmonary cavities, n (%) | 4 (10.0) |

| Bacterial load with Xpert MTB/RIF, n (%) | |

| High | 14 (35.0) |

| Medium | 17 (42.5) |

| Low to very low | 9 (22.5) |

| Drug-susceptibility pattern, n (%) | |

| Rifampicin and isoniazid resistance (MDR) | 31 (77.5) |

| Rifampicin resistance, isoniazid sensitive (RR) | 3 (7.5) |

| Only RR using Xpert MTB/RIFa | 6 (15.0) |

| Type of RR/MDR-TB, n (%) | |

| Primary disease | 13 (32.5) |

| Relapse after DS-TB treatment | 15 (37.5) |

| Retreatment after loss to follow-up | 4 (10.0) |

| Failed DS-TB treatment | 8 (20.0) |

| Type of treatment, n (%)b | |

| All-oral regimen | 33 (82.5) |

| Injectable kanamycin-containing regimen | 7 (17.5) |

| Blood test values at PK sampling day, median (IQR) | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.78 (0.65–0.89) |

| Bilirubin total, g/dL | 0.33 (0.26–0.40) |

| AST, IU/L | 26 (19–35) |

| ALT, IU/L | 25 (18–32) |

| Light breakfast meals before PK sampling, n (%) | 28 (70.0) |

| Isoniazid doses, mg/kg, median (IQR) | 11.2 (10.4–11.9) |

aPatients who never had a positive culture result from initial screening to the end of treatment.

bAll-oral regimen: bedaquiline, moxifloxacin, clofazimine, high-dose isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and ethionamide; injectable kanamycin-containing regimen: kanamycin, moxifloxacin, clofazimine, high-dose isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol and ethionamide.

PK of isoniazid and predictors of exposure

In total, 240 plasma samples of isoniazid were available, of which 27 samples (mostly at pre-dose) were below the LLOQ. The geometric mean (range) AUC0–24 and Cmax of isoniazid were 35.4 (8.2–117.3) h·mg/L and 8.5 (2.8–23.5) mg/L, respectively. Among 39 patients where isoniazid t½ could be estimated, 14 (35.9%) had a slow acetylator phenotype and 25 (64.1%) had a non-slow acetylator phenotype. The geometric mean AUC0–24 values in slow and non-slow acetylators were 68.7 and 23.7 h·mg/L, respectively (P < 0.001). Large inter-individual variabilities were observed in AUC0–24 and Cmax, even after stratification by acetylator phenotype. For instance, minimum and maximum values in all patients differed 14-fold for AUC0–24 and 8-fold for Cmax (Table 2). AUC0–24 values were highly correlated with Cmax values (r = 0.78, P < 0.001). Additional PK parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary PK parameters of high-dose isoniazid in Indonesian RR/MDR-TB patients by acetylator phenotypic status

| Total (n = 40) | Acetylator phenotypea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow (n = 14) | Non-slow (n = 25) | ||

| AUC0–24, h·mg/L | 35.4 (8.2–117.3) | 68.7 (24.9–117.3) | 23.7 (8.2–45.5) |

| C max, mg/L | 8.5 (2.8–23.5) | 11.3 (6.3–20.9) | 7.3 (2.8–23.5) |

| T max, h, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| Ke | 0.3 (0.1–0.7)b | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) |

| t ½, h | 2.1 (1.0–8.1)b | 3.7 (2.4–8.1) | 1.6 (1.0–2.2) |

| CL/F, L/h | 14.8 (5.1–54.7) | 7.7 (5.1–18.1) | 21.8 (10.6–54.7) |

| V d/F, L | 46.4 (20.1–99.6)b | 41.5 (25.1–81.9) | 49.3 (20.1–99.6) |

Data are presented as geometric mean (minimum–maximum range), unless otherwise stated. Ke, elimination rate constant; CL/F, apparent clearance; Vd/F, apparent volume of distribution.

aAcetylator status was determined phenotypically based on isoniazid t½ of >2.2 h (slow acetylators) or ≤2.2 h (non-slow acetylators).

bTotal n = 39.

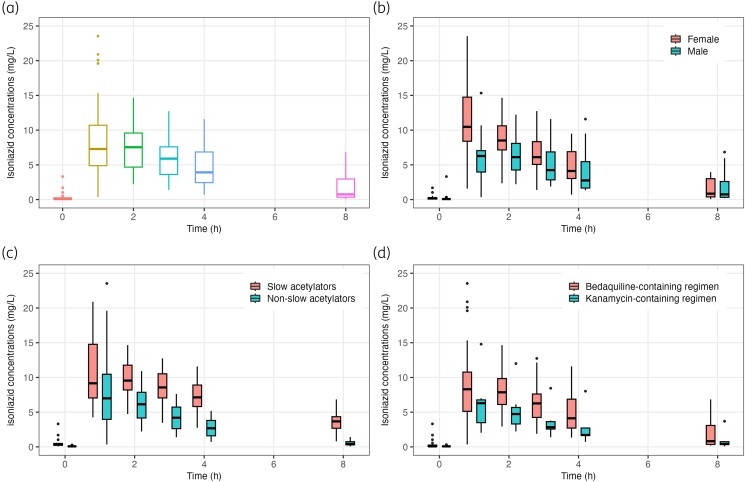

In univariable analyses for potential predictors (Table S1), only acetylator phenotype, concurrent kanamycin use, and type of disease were associated with isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax, with addition of sex, which was associated with isoniazid Cmax. In multivariable linear regression analyses (Table 3), isoniazid AUC0–24 values were 63.5% lower in non-slow acetylators (95% CI −72.4 to −51.7) and 40.0% lower in those treated with a kanamycin-containing regimen (95% CI −57.8 to −14.6). Furthermore, isoniazid Cmax values were 32.3% lower in non-slow acetylators (95% CI −49.0 to −10.2), 32.5% lower in those treated with a kanamycin-containing regimen (95% CI −52.7 to −3.7) and 34% lower in male patients (95% CI −49.7 to −13.4). For kanamycin versus bedaquiline use, no major imbalance of patient characteristics was found, making confounding from observed factors less likely (Table S2). Isoniazid dose in mg/kg was not significantly associated with exposures. PK profiles of isoniazid, stratified by key determinants of exposures are presented in Figure 1(a–d).

Table 3.

Factors associated with log-transformed AUC0–24 and Cmax of high-dose isoniazid in Indonesian RR/MDR-TB patients using multivariable linear regression analyses

| Geometric mean | Unadjusted percentage change (95% CI) | Adjusted percentage change (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–24 model | AUC0–24, h·mg/L | ||

| Drug dose, mg/kg | — | 14.6 (−8.3 to 43.1) | 7.1 (−6.3 to 22.5) |

| Sex, male/female | 31.2/40.6 | −26.2 (−52.6 to 14.9) | −18.8 (−38.0 to 6.3) |

| Kanamycin-containing regimen, yes/no | 20.5/39.7 | −47.4 (−69.7 to −8.8)* | −40.0 (−57.8 to −14.6)** |

| Acetylator phenotype, non-slow/slowa | 23.7/68.7 | −65.4 (−74.7 to −52.7)*** | −63.5 (−72.4 to −51.7)*** |

| C max model | C max, mg/L | ||

| Drug dose, mg/kg | — | 9.7 (−7.6 to 30.2) | 6.8 (−6.7 to 22.3) |

| Sex, male/female | 6.8/10.9 | −38.3 (−54.7 to −16.0)** | −34.0 (−49.7 to −13.4)** |

| Kanamycin-containing regimen, yes/no | 5.6/9.3 | −40.7 (−61.0 to −9.8)* | −32.5 (−52.7 to −3.7)* |

| Acetylator phenotype, non-slow/slowa | 7.3/11.3 | −35.7 (−53.9 to −10.4)* | −32.3 (−49.0 to −10.2)** |

Data are presented as median, as well as percentage change and 95% CIs, where applicable. Percentage change was calculated using the following equation: , where B is the regression coefficient. The total explained variance (R2) for the AUC0–24 model was 0.690 and for the Cmax model was 0.462. Drug dose in mg/kg was mean-centred by subtracting the mean from each datapoint, then standardized by dividing each point by the standard deviation. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. All potential factors associated with isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax in univariable analyses can be found in Table S1.

aAcetylator status was determined phenotypically based on isoniazid t½ of >2.2 h (slow acetylators) or ≤2.2 h (non-slow acetylators).

Figure 1.

PK profiles (plasma drug concentration versus time curves) of high-dose isoniazid in the total patients with RR/MDR-TB in Indonesia (a), stratified by sex (female versus male) (b), acetylator phenotype (slow versus non-slow acetylators) (c), and treatment regimen (injectable kanamycin-containing regimen versus oral bedaquiline-containing regimen (d). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Attainment of PK and PK/PD targets

Compared with overall estimates of isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax in Indonesian DS-TB patients, our overall estimates were approximately 2-fold higher, for both AUC0–24 (35.4 versus 15.6–16.4 h·mg/L) and Cmax (8.5 versus 4.5 mg/L). Isoniazid MIC data were available for 26 (65%) of 40 patients, ranging from 0.25 to >4 (assumed to be 4.125) mg/L. The geometric mean (range) AUC0–24/MIC and Cmax/MIC ratios for isoniazid were 22.2 (3.0–469.1) and 5.3 (0.9–59.1), respectively. Although the AUC0–24 and Cmax values for high-dose isoniazid were higher than for the standard dose, only a few patients in this study achieved the proposed targets for AUC0–24/MIC (n = 6/26; 23.1%) and Cmax/MIC (n = 5/26; 19.2%); all of these patients had low-level resistance with an MIC of 0.25–0.5 mg/L.

Treatment safety/tolerability

Of the 40 patients, 1 (2.5%) developed a severe adverse event (grade 3 morbilliform rash, possibly due to isoniazid, ethionamide and/or pyrazinamide) after 15 weeks of treatment, who then decided to permanently discontinue treatment. Isoniazid AUC0–24 and Cmax values in this patient were 25.8 h·mg/L and 7.0 mg/L, respectively. Severe drug-induced hepatotoxicity (ALT >5× the ULN) was not observed in any of the patients on high-dose isoniazid, whether slow or non-slow acetylator.

Sputum culture conversion

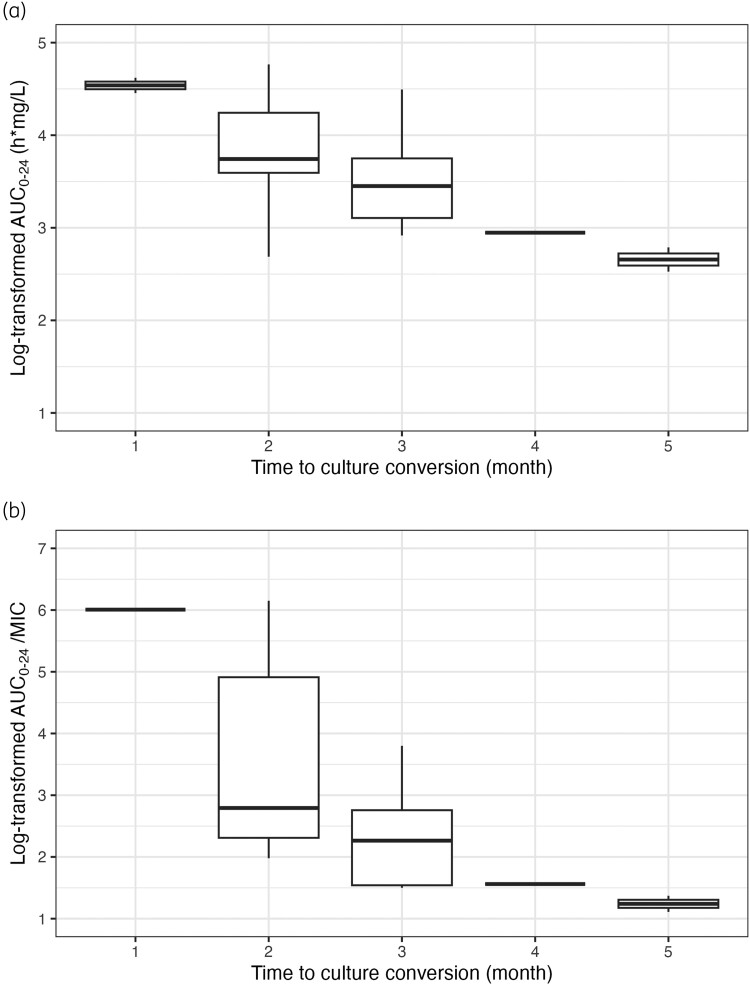

Of the 40 patients, 22 (55%) had culture conversion within 2 months of treatment, 10 (25%) had culture conversion after ≥3 months, 1 (2.5%) had no culture conversion during treatment, and 6 (15%) never had a positive culture result from initial screening to the end of treatment. In general, patients with longer time to culture conversion had lower isoniazid AUC0–24 and AUC0–24/MIC values (Figure 2). In multivariable logistic regression analyses, we found that patients with delayed/no culture conversion had significantly lower isoniazid AUC0–24 values [adjusted OR 0.18 (95% CI 0.04–0.89)] compared with those without delayed culture conversion (Table 4). Of these 11 patients whose culture conversion was delayed or absent during treatment, 8 (73%) failed to achieve PK/PD targets for isoniazid AUC0–24/MIC and Cmax/MIC, and 3 (27%) had missing AUC0–24/MIC and Cmax/MIC data. Lower isoniazid Cmax, AUC0–24/MIC and Cmax/MIC values tended to be associated with delayed culture conversion but were not statistically significant (P < 0.1) (Table S3).

Figure 2.

Log-transformed AUC0–24 (a) and AUC0–24/MIC (b) values of isoniazid presented based on time to sputum culture conversion in patients with RR/MDR-TB in Indonesia.

Table 4.

The effects of AUC0–24 and Cmax of high-dose isoniazid on delayed sputum culture conversion in liquid MGIT medium among Indonesian RR/MDR-TB patients using multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Delayed culture conversion (n = 11) | No delayed culture conversion (n = 22) | cOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–24 model | ||||

| Log AUC0–24, h·mg/L | 3.0 (2.8–3.6) | 3.8 (3.6–4.3) | 0.14 (0.02–0.55)* | 0.18 (0.04–0.89)* |

| Age, years | 35.0 (24.0–38.0) | 41.0 (33.5–54.5) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01)# | 0.93 (0.86–1.01)# |

| Treatment regimen | ||||

| Bedaquiline-containing regimen | 7 (63.6) | 20 (90.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Kanamycin-containing regimen | 4 (36.4) | 2 (9.1) | 5.71 (0.91–48.40)# | 4.08 (0.36–45.88) |

| C max model | ||||

| Log Cmax, mg/L | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | 2.3 (2.1–2.5) | 0.20 (0.03–1.00)# | 0.30 (0.04–1.70) |

| Age, years | 35.0 (24.0–38.0) | 41.0 (33.5–54.5) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01)# | 0.93 (0.86–1.00)# |

| Treatment regimen | ||||

| Bedaquiline-containing regimen | 7 (63.6) | 20 (90.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Kanamycin-containing regimen | 4 (36.4) | 2 (9.1) | 5.71 (0.91–48.40)# | 4.74 (0.53–54.86) |

Data are presented as number (percentage) or median (IQR), where applicable. Effect estimates are presented as crude and adjusted ORs (cOR and aORs, respectively) along with 95% CIs. In these multivariable logistic regression models, patients who had delayed sputum culture conversion (≥3 months after treatment initiation) and who had no culture conversion during treatment (total n = 11) were compared with those with time to culture conversion ≤2 months after treatment initiation (n = 22). Due to the limited power of each regression model, only AUC0–24 or Cmax, and two explanatory variables having a P value of <0.2 in the univariable analysis were included in each multivariable model. Hosmer–Lemeshow test results: AUC0–24 model (P = 0.117) and Cmax model (P = 0.546). Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves: AUC0–24 model (0.855) and Cmax model (0.789). *P < 0.05; #P < 0.1.

Treatment outcomes

After 9–11 months of shorter treatment, 22 (55%) of 40 patients were cured, 4 (10%) completed treatment, 1 (2.5%) died, 1 (2.5%) was lost to follow-up and 12 (20%) failed treatment (including 1 who discontinued treatment due to a severe adverse event and 11 who had their treatment modified for longer regimens of 18–24 months). Of these 12 patients who failed shorter treatment, 3 (25%) had initial culture conversion, then later had AFB smear or culture reversion to positive (these 3 patients eventually died during longer treatment). Neither isoniazid AUC0–24, Cmax, AUC0–24/MIC nor Cmax/MIC values were found to be significantly associated with treatment failure and unfavourable outcome (Tables S4 and S5).

Discussion

Although high-dose isoniazid is part of a 9–11 month standardized RR/MDR-TB regimen and could be used in longer individualized treatments, PK and PK/PD data of high-dose isoniazid are limited, making it a priority to describe PK and PK/PD of this drug in the RR/MDR-TB population. Our study presents important information on plasma exposure to high-dose isoniazid in adults treated for RR/MDR-TB in Indonesia. We observed much higher exposures compared with those recorded in Indonesian DS-TB patients on the standard-dose isoniazid.27,28 However, considering susceptibility of the Mycobacterium,30 isoniazid exposures in this study were below targets in the majority of patients, with only <25% of patients achieving the targets for isoniazid AUC0–24/MIC (n = 6/26; 23%) and Cmax/MIC (n = 5/25; 19%). All of these patients harboured M. tuberculosis with low-level resistance to isoniazid. Non-slow acetylator phenotype, male sex and kanamycin-containing regimen were found to be important determinants for lower isoniazid exposures. Moreover, lower isoniazid exposures had a significant effect on delayed sputum culture conversion, which may have implications for ongoing TB transmission. High-dose isoniazid was not associated with severe hepatotoxicity.

Only a few published PK studies of high-dose isoniazid are available. Compared with a previous study in adults with MDR-TB in South Africa given 10 mg/kg doses, plasma isoniazid exposures in our study are slightly lower, both for AUC0–24 (geometric mean 35.4 versus mean 45.7 h·mg/L) and Cmax (geometric mean 8.5 versus mean 9.4 mg/L).12 As noted in a recent systematic review, this phenomenon might be explained by the high frequency of the fast acetylator phenotype in people originating from specific geographical regions, notably East Asia (including Indonesia), compared with those from Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and West Europe, who are the main carriers of the slow acetylator status,31 although this finding is not confirmed in some studies in sub-Saharan Africa, where ∼60% of patients demonstrate the intermediate/fast acetylator phenotype.23,29

Dose in mg/kg is known to be an important determinant of isoniazid exposure.32 In a previous modelling study among MDR-TB patients in South Africa, isoniazid at higher doses was found to exhibit non-linear PK.16 In the current study, however, doses were not found to be significantly associated with isoniazid exposures. This might be explained by the small range of mg/kg doses used in the study (IQR 10.4–11.9 mg/kg), which may have obscured the true relationship. Aside from dose in mg/kg, acetylator status based on N-acetyltransferase 2 genotypes or other phenotyping methods has been described as a strong determinant of isoniazid exposure, either in DS-TB patients32,33 or in MDR-TB patients.11,16,17 As confirmed by our study, acetylator status is indeed an important determinant of isoniazid exposure, with non-slow acetylators showing a 63% decrease in AUC0–24 compared with slow acetylators. Male sex was also found in this study to be significantly associated with lower isoniazid exposures. However, it should be noted that our linear model did not include allometric scaling by fat-free mass, which has been reported in previous non-linear mixed-effects models to account for most sex effects on PK parameters of first-line anti-TB drugs.16,34,35

Interestingly, our study showed that patients treated with a kanamycin-containing regimen had significantly lower isoniazid exposures than those treated with a bedaquiline-containing regimen. To our knowledge, no previous studies have reported interactions between isoniazid and kanamycin that could lead to a reduction in isoniazid exposure. We acknowledge that there was a major temporal effect in this study, given that all early patients received kanamycin (n = 7), and after 2020 all received bedaquiline (n = 33). Although we were unable to identify confounding from measured factors, confounding from unmeasured factors seems still very likely. Of note, bedaquiline is not known to cause a significant increase in isoniazid AUC0–24, although a slight increase (∼7%) is expected.36 In a study conducted in South Africa among children mainly treated with regimens containing amikacin (a semisynthetic analogue of kanamycin), plasma exposure to high-dose isoniazid was also found to be significantly lower (median AUC0–24: 13.1 h·mg/L) than in children receiving high-dose isoniazid for MDR-TB preventive therapy without amikacin (median AUC0–24: 78.1 h·mg/L).17 The reason was also unclear in the study, but the authors postulated that one of the accompanying anti-TB drugs, in particular terizidone (a structural analogue of cycloserine), was likely to interfere with isoniazid absorption and has led to a reduction in isoniazid exposures.17,37

Our result on the effect of lower isoniazid exposures on delayed sputum culture conversion is in agreement with other studies among DS-TB patients.38,39 These studies showed that lower exposures to first-line drugs, especially isoniazid and rifampicin, and lower AUC/MIC ratios, were associated with delayed sputum culture conversion.38,39 This delay in culture conversion may have implications for ongoing TB transmission in the household and community, particularly in the context of high-incidence and low-income countries such as Indonesia, where most patients are not isolated in specialized hospitals during RR/MDR-TB treatment.

Our study is among the few studies evaluating the PK and PK/PD of high-dose isoniazid for the treatment of RR/MDR-TB. Our intensive PK sampling enabled us to obtain a close approximation of total drug exposure in plasma. Additionally, we incorporated MIC values in our analyses. Our study also has limitations. Firstly, performing a line-probe assay could be of value to detect isoniazid resistance by identifying mutations in the katG and inhA genes, but this assay was not part of routine diagnostic procedures for RR/MDR-TB in our setting. Secondly, MIC data for isoniazid were not available for some patients, owing to difficulties in obtaining sputum samples with a positive mycobacterial culture result; additionally, the phenotypic method used in this study was unable to determine MICs above 4 mg/L. Thirdly, our study was not designed to evaluate specific drug–drug interactions with isoniazid, and our finding regarding possible interactions of kanamycin in reducing isoniazid exposures should be interpreted with caution. Given that kanamycin is no longer recommended for RR/MDR-TB, this finding also requires confirmation using amikacin in future rescue regimens. Lastly, our study has a limited power to assess isoniazid exposure–response relationships, and therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Despite the small sample size, our logistic regression models on the relationships between isoniazid exposures and delayed culture conversion fitted the data well using Hosmer–Lemeshow tests. Future randomized controlled trials comparing the PK, safety/tolerability and efficacy of higher than currently recommended doses of isoniazid for the treatment of RR/MDR-TB are warranted.

In conclusion, high-dose isoniazid results in much higher exposures than the standard dose, as expected. Nevertheless, plasma exposures to high-dose isoniazid are below PK/PD targets in the majority of patients treated for RR/MDR-TB in Indonesia, especially among those with intermediate- to high-level resistance to isoniazid. Certain subgroups with a higher risk of suboptimal exposures to isoniazid, notably non-slow acetylators and male patients, may require dose adjustments or individualized therapeutic drug monitoring. Designing more optimal dosing strategies to ensure adequate concentrations of this drug and to balance treatment safety and efficacy is warranted, especially among specific risk groups observed in this study. Although the exposure–response analyses in this study lacked statistical power, the effect of lower isoniazid exposures on delayed sputum culture conversion deserves attention and requires further investigation, as it has implications for ongoing TB transmission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the director of Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, for accommodating the research. We would also like to thank Claudia Selviyanti, Agnesya, Rhea Veda Nugraha, Nurul Annisa, and all the staff at the MDR-TB clinic of the Hasan Sadikin Hospital for their help with patient follow-up and data recording, and all the patients for participating in this study.

Contributor Information

Vycke Yunivita, Division of Pharmacology and Therapy, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; TB Working Group, Research Center for Care and Control of Infectious Diseases, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Fajri Gafar, Division of Pharmacology and Therapy, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; Respiratory Epidemiology and Clinical Research Unit, Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, 5252 Boulevard de Maisonneuve Ouest, Office 3D.21, Montreal, Quebec H4A 3S5, Canada; McGill International TB Centre, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Prayudi Santoso, Division of Respirology and Critical Care, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran and Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia.

Lidya Chaidir, TB Working Group, Research Center for Care and Control of Infectious Diseases, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; Division of Microbiology, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Arto Y Soeroto, Division of Respirology and Critical Care, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran and Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia.

Triana N Meirina, Pharmacokinetic Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Lindsey Te Brake, Department of Pharmacy, Radboud Institute for Medical Innovation, Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Dick Menzies, Respiratory Epidemiology and Clinical Research Unit, Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, 5252 Boulevard de Maisonneuve Ouest, Office 3D.21, Montreal, Quebec H4A 3S5, Canada; McGill International TB Centre, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Rob E Aarnoutse, Department of Pharmacy, Radboud Institute for Medical Innovation, Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Rovina Ruslami, Division of Pharmacology and Therapy, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; TB Working Group, Research Center for Care and Control of Infectious Diseases, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia; McGill International TB Centre, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the internal research grants of the Universitas Padjadjaran, including the Academic Leadership Grant awarded to R.R. (grant number: 3855/UN.C/LT/2019) and the RPLK grant awarded to V.Y. (grant numbers: 1427/UN6.3.1/LT/2020 and 1959/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2021).

Transparency declarations

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

R.R. was the principal investigator of the study. V.Y., P.S., L.C., A.Y.S., L.t.B., R.E.A. and R.R. contributed to the conception and design of the study. V.Y. and T.N.M. performed PK sampling and bioanalysis of isoniazid under the supervision of R.R. The attending physicians at the MDR-TB clinic at Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung were P.S. and A.Y.S., and they contributed to the enrolment and follow-up of patients. L.C. assisted in the examination of microbiological samples. F.G. performed all data analyses and created tables and figures. V.Y., F.G., P.S., L.C., A.Y.S., T.N.M., L.t.B., D.M., R.E.A. and R.R. interpreted the results. F.G. and V.Y. drafted the manuscript under the supervision of R.E.A., D.M. and R.R. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission for publication.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary data

Appendix 1 and Tables S1 to S5 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. WHO . Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729.

- 2. Ahmad N, Ahuja SD, Akkerman OW et al. Treatment correlates of successful outcomes in pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 392: 821–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31644-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lestari BW, McAllister S, Hadisoemarto PF et al. Patient pathways and delays to diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in an urban setting in Indonesia. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2020; 5: 100059. 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bélard S, Janssen S, Osbak KK et al. Limited access to drugs for resistant tuberculosis: a call to action. J Public Health (Oxf) 2014; 37: 691–3. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO . Rapid Communication: Key Changes to the Treatment of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UCN-TB-2022-2.

- 6. Mouton JW, Ambrose PG, Canton R et al. Conserving antibiotics for the future: new ways to use old and new drugs from a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic perspective. Drug Resist Updat 2011; 14: 107–17. 10.1016/j.drup.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Donald PR, Sirgel FA, Botha FJ et al. The early bactericidal activity of isoniazid related to its dose size in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156: 895–900. 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9609132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO . WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment, 2022 Update. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129. [PubMed]

- 9. Rivière E, Whitfield MG, Nelen J et al. Identifying isoniazid resistance markers to guide inclusion of high-dose isoniazid in tuberculosis treatment regimens. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 1332–7. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katiyar SK, Bihari S, Prakash S et al. A randomised controlled trial of high-dose isoniazid adjuvant therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008; 12: 139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gausi K, Ignatius EH, Sun X et al. A semimechanistic model of the bactericidal activity of high-dose isoniazid against multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: results from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 204: 1327–35. 10.1164/rccm.202103-0534OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dooley KE, Miyahara S, Von Groote-Bidlingmaier F et al. Early bactericidal activity of different isoniazid doses for drug-resistant tuberculosis (INHindsight): a randomized, open-label clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 1416–24. 10.1164/rccm.201910-1960OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Deun A, Maug AKJ, Salim MAH et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 684–92. 10.1164/rccm.201001-0077OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuaban C, Noeske J, Rieder HL et al. High effectiveness of a 12-month regimen for MDR-TB patients in Cameroon. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 517–24. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piubello A, Harouna SH, Souleymane MB et al. High cure rate with standardised short-course multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in Niger: no relapses. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18: 1188–94. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gausi K, Chirehwa M, Ignatius EH et al. Pharmacokinetics of standard versus high-dose isoniazid for treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 77: 2489–99. 10.1093/jac/dkac188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winckler JL, Schaaf HS, Draper HR et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose isoniazid in children affected by multidrug-resistant TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2021; 25: 896–902. 10.5588/ijtld.20.0870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Getahun M, Blumberg HM, Ameni G et al. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of rifampin and isoniazid among multidrug and isoniazid resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ethiopia. PloS One 2022; 17: e0274426. 10.1371/journal.pone.0274426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. Petunjuk Teknis Penatalaksanaan Tuberkulosis Resistan Obat di Indonesia [National Guidelines for the Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Indonesia]. 2020. https://tbindonesia.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TBRO_Buku-Juknis-Tuberkulosis-2020-Website.pdf.

- 20. Ruslami R, Gafar F, Yunivita V et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety/tolerability of isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide in children and adolescents treated for tuberculous meningitis. Arch Dis Child 2022; 107: 70–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yunivita V, Meirina TN, Dewi AP et al. Partial validation of ultra performance liquid chromatography method for quantification of isoniazid-pyrazinamide in human samples. J Pure Appl Chem Res 2021; 10: 175–81. 10.21776/ub.jpacr.2021.010.03.600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alffenaar JWC, Gumbo T, Dooley KE et al. Integrating pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in operational research to end tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70: 1774–80. 10.1093/cid/ciz942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parkin DP, Vandenplas S, Botha FJH et al. Trimodality of isoniazid elimination—phenotype and genotype in patients with tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155: 1717–22. 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf.

- 25. Assemie MA, Alene M, Petrucka P et al. Time to sputum culture conversion and its associated factors among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Eastern Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 98: 230–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO . Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis—2013 Revision. 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/79199. [PubMed]

- 27. Yunivita V, te Brake L, Dian S et al. Isoniazid exposures and acetylator status in Indonesian tuberculous meningitis patients. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2024; 144: 102465. 10.1016/j.tube.2023.102465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saktiawati AMI, Sturkenboom MGG, Stienstra Y et al. Impact of food on the pharmacokinetics of first-line anti-TB drugs in treatment-naive TB patients: a randomized cross-over trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 703–10. 10.1093/jac/dkv394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donald PR, Parkin DP, Seifart HI et al. The influence of dose and N-acetyltransferase-2 (NAT2) genotype and phenotype on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of isoniazid. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 633–9. 10.1007/s00228-007-0305-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alsultan A, Peloquin CA. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of isoniazid in patients with intermediate resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017; 21: 121–3. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gutiérrez-Virgen JE, Piña-Pozas M, Hernández-Tobías EA et al. NAT2 global landscape: genetic diversity and acetylation statuses from a systematic review. PLoS One 2023; 18: e0283726. 10.1371/journal.pone.0283726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gafar F, Wasmann RE, McIlleron HM et al. Global estimates and determinants of antituberculosis drug pharmacokinetics in children and adolescents: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2023; 61: 2201596. 10.1183/13993003.01596-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hong B-L, D’Cunha R, Li P et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of isoniazid pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers and patients with tuberculosis. Clin Ther 2020; 42: e220–41. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Denti P, Wasmann RE, van Rie A et al. Optimizing dosing and fixed-dose combinations of rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide in pediatric patients with tuberculosis: a prospective population pharmacokinetic study. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75: 141–51. 10.1093/cid/ciab908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chirehwa MT, McIlleron H, Wiesner L et al. Effect of efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy and high-dose rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics of isoniazid and acetyl-isoniazid. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 139–48. 10.1093/jac/dky378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Heeswijk RPG, Dannemann B, Hoetelmans RMW. Bedaquiline: a review of human pharmacokinetics and drug–drug interactions. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 2310–8. 10.1093/jac/dku171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Early J. Cycloserine. In: Enna SJ, Bylund DB, eds. xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference. Vol 88. Elsevier, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rockwood N, Pasipanodya JG, Denti P et al. Concentration-dependent antagonism and culture conversion in pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 1350–9. 10.1093/cid/cix158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sekaggya-Wiltshire C, Von Braun A, Lamorde M et al. Delayed sputum culture conversion in tuberculosis-human immunodeficiency virus-coinfected patients with low isoniazid and rifampicin concentrations. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 708–16. 10.1093/cid/ciy179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.