Abstract

BACKGROUND

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common and distressing endocrine disorder associated with lower quality of life, subfertility, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. PCOS characteristics, its comorbidities, and its treatment can potentially influence sexual function. However, studies on sexual function in women with PCOS are limited and contradictory.

OBJECTIVE AND RATIONALE

The aim was to perform a systematic review of the published literature on sexual function in women with PCOS and assess the quality of the research and certainty of outcomes, to inform the 2023 International Guidelines for the Assessment and Management of PCOS.

SEARCH METHODS

Eight electronic databases were searched until 1 June 2023. Studies reporting on sexual function using validated sexuality questionnaires or visual analogue scales (VAS) in PCOS populations were included. Random-effects models were used for meta-analysis comparing PCOS and non-PCOS groups with Hedges’ g as the standardized mean difference. Study quality and certainty of outcomes were assessed by risk of bias assessments and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) method according to Cochrane. Funnel plots were visually inspected for publication bias.

OUTCOMES

There were 32 articles included, of which 28 used validated questionnaires and four used VAS. Pooled Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores in random-effects models showed worse sexual function across most subdomains in women with PCOS, including arousal (Hedges’s g [Hg] [95% CI] = −0.35 [−0.53, −0.17], I2 = 82%, P < 0.001), lubrication (Hg [95% CI] = −0.54 [−0.79, −0.30], I2 = 90%, P < 0.001), orgasm (Hg [95% CI] = −0.37 [−0.56, −0.19], I2 = 83%, P < 0.001), and pain (Hg [95% CI] = −0.36 [−0.59, −0.13] I2 = 90%, P < 0.001), as well as total sexual function (Hg [95% CI] = −0.75 [−1.37, −0.12], I2 = 98%, P = 0.02) and sexual satisfaction (Hg [95% CI] = −0.31 [−0.45, −0.18], I2 = 68%, P < 0.001). Sensitivity and subgroup analyses based on fertility status and body mass index (BMI) did not alter the direction or significance of the results. Meta-analysis on the VAS studies demonstrated the negative impact of excess body hair on sexuality, lower sexual attractiveness, and lower sexual satisfaction in women with PCOS compared to controls, with no differences in the perceived importance of a satisfying sex life. No studies assessed sexual distress. GRADE assessments showed low certainty across all outcomes.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS

Psychosexual function appears to be impaired in those with PCOS, but there is a lack of evidence on the related distress scores, which are required to meet the criteria for psychosexual dysfunction. Health care professionals should discuss sexual function and distress and be aware of the multifactorial influences on sexual function in PCOS. Future research needs to assess both psychosexual function and distress to aid in understanding the degree of psychosexual dysfunction in PCOS. Finally, more diverse populations (e.g. non-heterosexual and more ethnically diverse groups) should be included in future studies and the efficacy of treatments for sexual dysfunction should also be assessed (e.g. lifestyle and pharmacological interventions).

Keywords: polycystic ovary syndrome, sexuality, female sexual function, sex counselling, sexual satisfaction, sexual arousal

Graphical Abstract

Women with PCOS report lower sexual function and lower sexual satisfaction compared to control women, both overall and in subgroups based on fertility status and body mass index.

Introduction

With an estimated prevalence of 5–20% worldwide, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age (Azziz et al., 2016; Teede et al., 2018; Louwers and Laven, 2020; Joham et al., 2022). PCOS in adults is diagnosed when two out of three characteristics are present: oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, hyperandrogenism (biochemical or clinical), and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) (Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group, 2004). PCOS is a distressing disorder associated with obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, and subfertility. Furthermore, there is an increased risk for depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and a lower quality of life in PCOS compared to non-PCOS populations (Cooney et al., 2017).

Treatment of PCOS is complex and consists of lifestyle modification (e.g. losing weight, exercise, healthy diet) as first-line treatment. For women with subfertility who want to conceive, ovulation induction is often required (Louwers and Laven, 2020; Joham et al., 2022). Women without a desire to conceive are usually prescribed the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) (Teede et al., 2018). Both lifestyle changes and COCPs aim to improve endocrine features by either changing androgen levels directly or indirectly through weight change. Androgens play an important role in sexual function in both sexes. It is known that reduced androgen levels in women may affect sexual function (Zimmerman et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2016). However, the effect of supra-physiological androgen levels on sexual function in women is not clearly known.

Sexual function is a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon, as is PCOS, and can be affected by several factors. Androgen levels can influence sexual function and desire, although psychosocial factors should not be overlooked (Heiman et al., 2011; Maseroli and Vignozzi, 2022). Obesity is associated with lower sexual function and a higher risk of sexual dysfunction in women through direct effects of adipose tissue on sexual response, pathophysiological effects of obesity-related comorbidities, and the impact of psychological factors. Indeed, reducing weight has been shown to improve sexual function (Kolotkin et al., 2012; Rowland et al., 2017; Loh et al., 2022). Similarly, metabolic syndrome can adversely impact sexual function through vascular risk factors, whereas treating metabolic syndrome improves sexual function (Miner et al., 2012; Di Francesco et al., 2019). Infertile women report lower sexual function and satisfaction than fertile women, likely due to contributing factors such as timed intercourse, marital problems, and the psychological burden of infertility (Mendonca et al., 2017; Starc et al., 2019; Okobi, 2021). Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety influence sexual function negatively as an effect of the disease itself, but also as a side effect of prescribed medication (Brotto et al., 2016; McCabe et al., 2016). Finally, poor body image (Woertman and van den Brink, 2012; van den Brink et al., 2013; Brotto et al., 2016) and low self-esteem (Brotto et al., 2016; Sejourne et al., 2019) impair sexual function through heightened self-consciousness and negative cognitions during sexual activity. These factors are all commonly present in women with PCOS, suggesting that PCOS itself, its comorbidities, and its treatment interventions may potentially influence sexual function.

Research focusing on psychosocial aspects or sexual function in PCOS is fairly recent. Some studies suggest no differences in sexual function in women with PCOS (Murgel et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019), while others report more sexual problems in PCOS compared to their non-PCOS counterparts (Castelo-Branco and Naumova, 2020; Loh et al., 2020). In 2018, we published the first meta-analysis on sexual function in women with PCOS, which showed lower sexual function and lower sexual satisfaction in women with PCOS compared to control women (Pastoor et al., 2018). Since then, a number of studies on sexual function in PCOS have been published, recognizing the importance of the topic. Although meta-analyses (Murgel et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Loh et al., 2020) using the Female Sexual Function Index total scores have been conducted, these have included only a few studies (four to six in total); hence, an update of our previous review was deemed timely.

The aim of the current systematic review and meta-analysis is to present a comprehensive synthesis of the published literature on sexual function in women with PCOS and to evaluate the quality of the evidence and certainty of outcomes. Findings from this review and meta-analysis have directly informed the 2023 update of the International Evidence Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of PCOS, guiding the upcoming recommendations for assessing and managing sexual function in women with PCOS.

Methods

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from inception until 1 June 2023: Embase, Medline (via Ovid), Web-of-Science, Scopus, PsycINFO (via Ovid), Cinahl (via EBSCOhost), Cochrane CENTRAL (via Wiley), and Google Scholar (via Publish or Perish). The search was developed by an experienced biomedical information specialist (W.B.), together with the lead author (H.P.). Various relevant search terms (thesaurus terms and terms in title and/or abstract) concerning PCOS and sexual function were used. The search string did not include restrictions on date, type of publication, or language in order to capture as many publications as possible. To update the previous search from 2018, the Medical Library of Erasmus MC used the following method: first, all results that were obtained in the present search (from inception) were downloaded in Endnote and deduplicated. Second, the previous 2018 Endnote file was completely copied to the new EndNote file and the references were deduplicated again. By removing both duplicates, only the new references were present in the current Endnote file (Bramer and Bain, 2017).

Eligibility criteria using the Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome (PICO) framework, as well as the search strategy, are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following the electronic search, the screening and selection of publications were performed by two authors (H.P., H.B.) independently. They considered all studies addressing PCOS and sexual function for inclusion. First, selection on title and abstract and second, selection of full texts on in- and exclusion criteria was done. The following inclusion criteria were used: (i) participants aged 14 years and older; (ii) adequate diagnosis of PCOS (Rotterdam criteria; the former and current National Institutes of Health (NIH) definition; the Androgen Excess (AE) & PCOS Society definition; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology PCOS guideline 2018; American Society for Reproductive Medicine; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development); (iii) the use of validated sexuality questionnaires or visual analogue scales (VAS); (iv) inclusion of a control group without PCOS; and (v) adequate definition of sexual function (operationalized as: desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, frequency of intercourse, masturbation frequency, sexual dysfunction, sexual satisfaction, sexual self-image, sexual début, and sexual distress). To be included, studies had to be original studies and had to be available as full-text in the English language.

Excluded were studies unrelated to PCOS or PCOS induced by valproate use or PCOS in combination with other illnesses or diseases like diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Moreover, studies solely concerning health-related quality of life, quality of life or mental health and studies concerning idiopathic hyperandrogenism or hyperandrogenism caused by diseases other than PCOS were excluded. Finally, review articles, PhD theses, abstracts, and posters were also excluded. All discrepancies in choices were discussed to reach consensus. A complete overview of included and excluded studies can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from identified studies: study design, publication date, authors, country, setting, population, period of recruitment, sample size, intervention, outcome measures with corresponding data, and narrative summaries of key findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics for the included studies.

| Author, year, country | Setting (population) Period of recruitment PCOS diagnostic criteria | Study design | Sample size per group | Outcomes | Summary of findings | Other notes | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elsenbruch et al., 2003, Germany |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

VAS sexual function | PCOS: less satisfied with sexual life, less attractive, sex life is as important as for controls, body hair impacts sexuality negatively | Elsenbruch, Tan, Hahn, and Caruso used the same control group | Moderate |

| Hahn et al., 2005, Germany |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

VAS sexual function | PCOS: less satisfied with sexual life, less attractive, sex life is as important as for controls, body hair impacts sexuality negatively | Elsenbruch, Tan, Hahn, and Caruso used the same control group | Moderate |

| Drosdzol et al., 2007, Poland |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

ISS questionnaire sexual function | PCOS lower marital sexual function, more marital sexual dysfunction, hirsutism affects sexual function negatively than controls | Moderate | |

| Tan et al., 2008, Germany |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

VAS sexual function | PCOS reduced sexual satisfaction and sexual self-worth compared to controls |

|

Moderate |

| Caruso et al., 2009, Italy |

|

Prospective intervention |

|

VAS sexual function | Women with PCOS find themselves less sexual attractive. Body hair impacted sexual function and PCOS had an impact on social relations. |

|

Moderate |

| Mansson et al., 2011, Sweden |

|

Case control |

|

McCoy-FSQ | Despite having the same number of partners and about the same frequency of sexual intercourse, women with PCOS were generally less satisfied with their sex lives compared to the population-based controls. PCOS women scored numerically lower than controls on the McCoy total score, but this difference was not statistically significant. | Not included in MA for outliers see Pastoor et al. 2018 | NA |

| Gateva and Kamenov, 2012, Bulgaria |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | PCOS lower sexual function scores then obese controls. Obese PCOS women score better in FSFI than lean PCOS women. |

|

Moderate |

| Stovall et al., 2012, USA |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

CSFQ | PCOS lower orgasm score than controls, higher BMI related to worse orgasm scores, testosterone >1SD above mean better sexual function | Moderate | |

| Ercan et al., 2013, Turkey |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | No differences in sexual function, higher testosterone associated with higher total FSFI score | Low | |

| Ferraresi et al., 2013, Brazil |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | PCOS 50% below cut off FSFI, no significant differences in FSFI total score between PCOS and control | We used both the lean and obese data. | Moderate |

| Zueff et al., 2015, Brazil |

|

Case control |

|

SQ-F | No significant differences in total SQ-F scores | Moderate | |

| Benetti-Pinto et al., 2014, Brazil |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | PCOS lower score on FSFI scales except for desire and orgasm | Low | |

| Elkhiat et al., 2015, Egypt |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSDQ | PCOS lower scores on FSDQ scales except for solitary desire. Normal testosterone levels in PCOS associated with better sexual function. | Moderate | |

| Kowalczyk et al., 2015, Poland |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

MSQ | Both groups find sexuality equally important. PCOS rates themselves negatively as sexual partner. | Low | |

| Lara et al., 2015, Brazil |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | PCOS more sexual dysfunction at baseline, other scales similar scores between PCOS and controls | Intervention study, we used baseline scores only for this meta-analysis | Moderate |

| Noroozzadeh et al., 2016, Iran |

|

Cross-sectional population based |

|

FSFI | No significant differences between controls and PCOS on FSFI scores. | Low | |

| Shafti and Shahbazi, 2016, Iran |

|

Casual comparative study |

|

FSFI | No significant differences on FSFI scores between PCOS and controls | Moderate to high | |

| Diamond et al., 2017, USA |

|

Cross-sectional secondary data analysis with data from clinical trial |

|

FSFI |

|

|

NA |

| Basirat et al., 2019, Iran |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | No significant differences on FSFI scores between PCOS and controls | Low | |

| Glowinska et al., 2020, Poland |

|

Cross-sectional case control study |

|

SSS | No significant difference on this scale between PCOS and controls | We only used scores on the Physical satisfactions scale since we thought these were most comparable with FSFI satisfaction | Moderate |

| Deniz and Kehribar, 2020, Turkey |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | Controls have a significantly higher FSFI total score than women with PCOS | We only used data from PCOS fertile group | Low |

| Aydogan Kirmizi et al., 2020, Turkey |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | FSFI lubrication score was significantly higher in the PCOS group. Other scores were not significantly different. | We only used data from PCOS fertile group | Moderate |

| Akbari Sene et al., 2021, Iran |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | No significant differences were found between PCOS and controls | Low | |

| Mantzou et al., 2021, Greece |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | Women with PCOS scored significantly lower on FSFI domains arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction and on the FSFI total score | Low | |

| Taghavi et al., 2021, Iran |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | Women with PCOS scored significantly lower on all FSFI domains and the FSFI total score | Moderate | |

| Kałużna et al., 2021, Poland |

|

Case control |

|

SSQ | No significant difference between the groups in SSQ total score | PCOS infertile, control fertile | Moderate to high |

| Naumova et al., 2021, Spain |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | Women with PCOS scored significantly lower compared to the MFI control group on all FSFI domains except pain and on the FSFI total score | We only used data from the male factor infertility control group and the PCOS infertile group | Low |

| Karsten et al., 2021, The Netherlands |

|

Cross-sectional analysis of data from a follow up study after a multicentre RCT |

|

MFSQ | No significant differences between PCOS and controls were found on MFSQ scores. | Low | |

| Ashrafi et al., 2022, Iran |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | Infertile women with PCOS showed lower scores on all FSFI domains and the FSFI total score compared to women with male factor infertility. | We only used data from the male factor infertility control group | Moderate |

| Aba and Aytek Şik, 2022, Turkey |

|

Case control |

|

FSFI | Sex drive, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and averages of pain subscales and female sexual function index total score were significantly lower in the PCOS group than in the control group. | Moderate | |

| Çetinkaya Altuntaş et al., 2022, Turkey |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | No significant differences on the FSFI were found between the PCOS group and the control group. |

|

Low |

| Daneshfar et al., 2022, Iran |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | Women with PCOS reported a significantly lower total FSFI mean score then control women. |

|

High |

| Mojahed et al., 2023, Iran |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | PCOS Group scored significantly lower on all FSFI subdomains (except arousal) and the FSFI total score compared to the control group. | High | |

| Yildiz et al., 2017, Turkey |

|

Cross-sectional |

|

FSFI | In the normal BMI groups, the PCOS group scored significantly lower on all FSFI domains (except desire) and FSFI total score compared to the control group. | We only used the scores of the PCOS group with a normal BMI. | High |

BMI, body mass index; CSFQ, Changes in Sexual Function Questionnaire; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; FSDQ, Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire; FSDQ, Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire; ISS, Index of Sexual Satisfaction; McCoy-FSQ, McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire; MSQ, Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SSS, Sexual Satisfaction Scales; SSQ, Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire; SQ-F, Sexual Quotient-Female; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Quality assessment and GRADE assessment

Two reviewers (H.P., H.B.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the study characteristics and quality appraisal templates, which were based on an adapted version of the ROBINS-I tool (Sterne et al., 2016), provided by the evidence team of the PCOS guideline update (A.M., C.T.T.). This included assessment of internal validity, based on selection bias (comparability of populations, case definition, control status assessment), performance bias (treatment of groups, validated and standard measurements, blinding, valid and reliable outcome measures, objective assessment of outcome), attrition bias (loss to follow up, exclusion in analysis), report bias (selective outcome reporting), confounding (comparability of cohorts), and other bias (conflicts of interest, power analysis, statistical analysis). Overall risk of bias, judged as low, moderate, or high, was assessed based on these criteria (Supplementary Table S4).

Visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry was performed to assess potential publication bias. The certainty of the evidence was independently assessed by two authors (H.P., A.M.) using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework, as per the Cochrane GRADE handbook guidelines (Schunemann et al., 2000). This included outcome-level assessment of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other biases (e.g. publication bias or observational study design).

Outcome measures

Sexual function was measured using validated questionnaires: Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (Rosen et al., 2000); Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ) (Clayton et al., 1997); Sexual Quotient-Female (SQ-F) (Abdo, 2006); McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire (MFSQ) (McCoy, 2000); Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ) (Goldhammer and McCabe, 2011); and Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire (MSQ) (Snell et al., 1993). Additionally, sexual satisfaction was assessed with several validated questionnaires: Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS) (Hudson et al., 1981); Sexual Satisfaction Scales (Davis et al., 2006); and Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (SSQ) (Nomejko and Dolińska-Zygmunt, 2014). For details on all questionnaires, see Supplementary Table S5.

Seven questions scored with VAS were available for analysis: (i) How important is a satisfying sex life for you?; (ii) How many sexual thoughts and fantasies did you have in the past 4 weeks?; (iii) Do you find yourself sexually attractive?; (iv) How much does excessive body hair impact your sexuality?; (v) Does your appearance make it difficult to engage in social contact?; (vi) How often did you experience pain during intercourse in the past 4 weeks?; (vii) How satisfied were you with your sex life in the past 4 weeks? (Elsenbruch et al., 2003; Hahn et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2008; Caruso et al., 2009).

Statistical methods and meta-analysis

Meta-analyses were performed in SPSS v28.0.1.0 (142) using random-effects models. Differences between PCOS and control women are expressed in Hedges’ g (Hg) with corresponding 95% CIs and presented in forest plots. Where intervention studies were included, only the baseline scores were used in the meta-analyses.

To perform the meta-analyses, we grouped the multiple scales and subscales into total sexual function, sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain, and sexual satisfaction. Scores for ISS were reversed by subtracting the mean score from the total score, before entering them in the analysis.

Meta-analyses for all questionnaires combined were performed, as well as the sensitivity analyses for FSFI only studies. Analyses were performed for the following subscales: total sexual function, sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain, and sexual satisfaction. To assess the influence of fertility status and BMI on the relationship between PCOS and sexual function, subgroup analysis for fertility status (as reported in the included studies) and BMI status (mean BMI as reported in the included studies) was performed and presented in forest plots.

Since no new studies used VAS, no additional studies with VAS were included and no new meta-analyses were performed. Results of meta-analyses for the VAS studies are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 and can also be found in Pastoor et al. (2018).

Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis were not previously registered. It was commissioned by the Centre for Research Excellence in Women’s Health in Reproductive Life (CRE-WHiRL), Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, to update the 2023 International Evidence Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of PCOS (Mousa et al., 2023).

Results

Search results

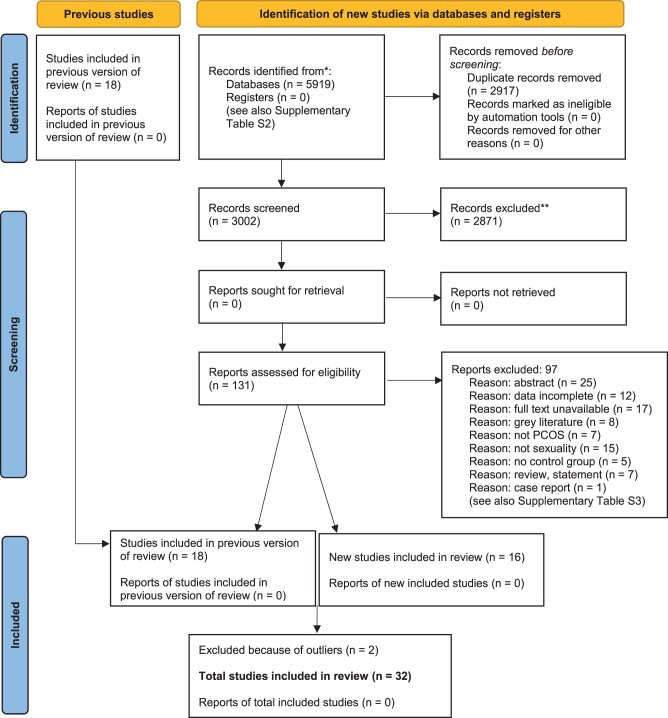

In Fig. 1, the results of the systematic literature search are presented. After screening, 34 articles were eligible. Two studies were then excluded because of outliers: the first for being an outlier on total sexual function, as well as for arousal and lubrication, most likely due to having a highly motivated participant group repeatedly instructed to have sexual intercourse at least twice a week (Diamond et al., 2017); the other for being an outlier for orgasm probably due to assessing orgasm differently than other scales did (Mansson et al., 2011). This resulted in a total of 32 included studies, of which 16 were newly added compared with our previous review (Pastoor et al., 2018).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Twenty studies used the FSFI (Gateva and Kamenov, 2012; Ercan et al., 2013; Ferraresi et al., 2013; Benetti-Pinto et al., 2014; Lara et al., 2015; Noroozzadeh et al., 2016; Shafti and Shahbazi, 2016; Yildiz et al., 2017; Basirat et al., 2019; Aydogan Kirmizi et al., 2020; Deniz and Kehribar, 2020; Akbari Sene et al., 2021; Mantzou et al., 2021; Naumova et al., 2021; Taghavi et al., 2021; Aba and Aytek Şik, 2022; Ashrafi et al., 2022; Çetinkaya Altuntaş et al., 2022; Daneshfar et al., 2022; Mojahed et al., 2023).

Eight studies used different scales: the CSFQ (Stovall et al., 2012), the SQ-F (Zueff et al., 2015), the MFSQ (Karsten et al., 2021), the FSDQ (Elkhiat et al., 2015), the ISS (Drosdzol et al., 2007), the MSQ (Kowalczyk et al., 2015), Sexual Satisfaction Scales (Glowinska et al., 2020), and the SSQ (Kałużna et al., 2021).

Finally, four studies used VAS to assess sexual function and impact of clinical characteristics on sexual function (Elsenbruch et al., 2003; Hahn et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2008; Caruso et al., 2009). These are the same studies as in our analysis from 2018 (Pastoor et al., 2018). No new studies using VAS were found (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Study characteristics for all of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Quality assessment and grading

The quality assessment of the included studies showed that most studies were of low to moderate quality mostly due to selection bias and confounding (Table 1). GRADE assessments showed that all outcomes were of low quality mostly due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision (Table 2). There was no evidence of publication bias for any outcomes based on visual inspection of funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Table 2.

GRADE assessment and evidence profile.

| COMPARISON: women with PCOS versus controls | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality assessment |

No. participants |

|||||||||||

| No. studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other | PCOS | Control | Effect estimate: Hedges’ g [95% CI] | Favours | Certainty | Importance |

| Outcome: total sexual function | ||||||||||||

| 22 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1630 | 1684 | −0.66 [−1.20, −0.12] | Controls |

|

CRITICAL |

| Outcome: sexual desire | ||||||||||||

| 21 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1735 | 1977 | −0.21 [−0.39, 0.02] | Controls |

|

CRITICAL |

| Outcome: sexual arousal | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1577 | 1811 | −0.33 [−0.50, −0.16] | Controls |

|

CRITICAL |

| Outcome: lubrication | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1549 | 1801 | −0.50 [−0.74, −0.26] | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: orgasm | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1641 | 1780 | −0.35 [−0.52, −0.18] | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: satisfaction | ||||||||||||

| 24 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1962 | 2246 | −0.26 [−0.37, −0.15] | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: pain | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Serious2 | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1485 | 1732 | −0.36 [−0.59, 0.13] | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS sexual thoughts and fantasies | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Serious3 | None | 225 | 50 | NA | No difference |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS sex life satisfaction | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Serious3 | None | 225 | 50 | NA | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS importance of satisfying sex life | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Case control, cross-sectional | Serious1 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Serious3 | None | 225 | 50 | NA | No difference |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS pain during intercourse | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Case control, cross-sectional | serious1 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Serious3 | None | 105 | 50 | NA | No difference |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS body hair impact | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Case control, cross-sectional | serious1 | not applicable | not applicable | serious3 | none | 297 | 50 | NA | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS social contact impact | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Case control, cross-sectional | serious1 | not applicable | not applicable | serious3 | none | 297 | 50 | NA | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

| Outcome: VAS sexual attractiveness | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Case control, cross-sectional | serious1 | not applicable | not applicable | serious3 | none | 297 | 50 | NA | Controls |

|

IMPORTANT |

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; VAS, visual analogue scale; NA, not applicable.

Downgraded once due to most studies being of moderate risk of bias.

Downgraded once due to high statistical heterogeneity.

Downgraded once due to small sample size of control group and the same controls used across all studies.

Meta-analysis

Sexual function

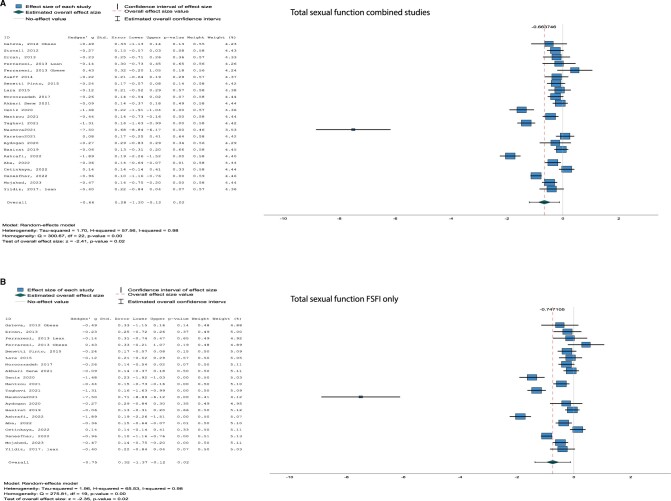

There were significant differences in total sexual function assessed with the combined questionnaires (Hg [95% CI] = −0.66 [−1.20, −0.12], I2 = 98%, P = 0.02) as well as with the FSFI only (Hg [95% CI] = −0.75 [−1.37, −0.12], I2 = 98%, P = 0.02), both being lower in women with PCOS compared to control women (Fig. 2A and B).

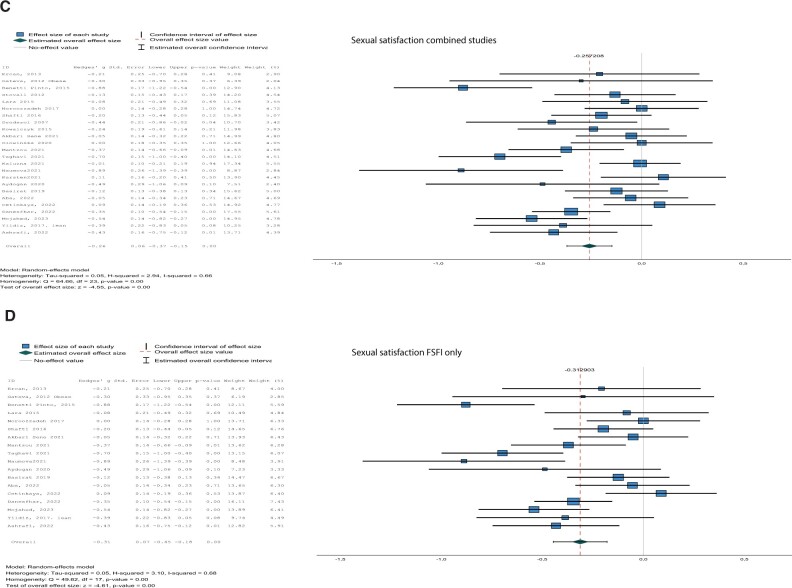

Figure 2.

Forest plots of questionnaires. Forest plots for total sexual function (A, B) and sexual satisfaction (C, D) both for all studies combined (A, C) and for studies using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (B, D) only.

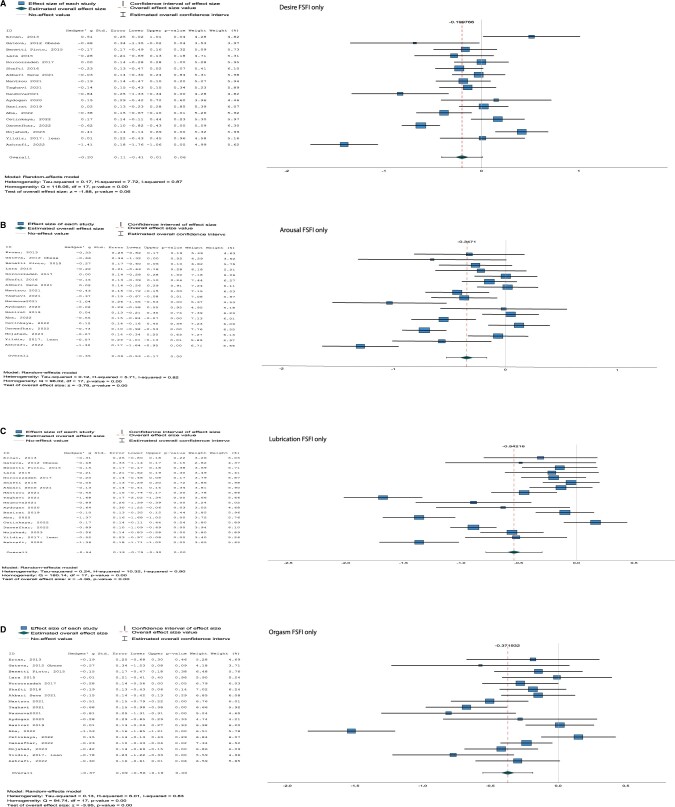

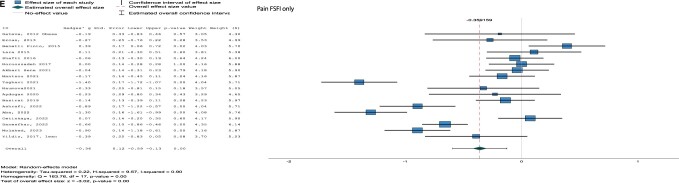

For all subdomains of sexual function, significant differences were found for desire (combined Hg [95% CI] = −0.21 [−0.39, −0.02], I2 = 87%, P = 0.03, arousal (combined Hg [95% CI] = −0.33 [−0.50, −0.16], I2 = 82%, P < 0.001; FSFI only Hg [95% CI] = −0.35 [−0.53, −0.17], I2 = 82%, P < 0.001), lubrication (combined [95% CI] Hg = −0.50 [−0.74, −0.26], I2 = 91%, P < 0.001; FSFI only Hg [95% CI] = −0.54 [−0.79, −0.30], I2 = 90%, P < 0.001), orgasm (combined Hg [95% CI] = −0.35 [−0.52, −0.18], I2 = 83%, P < 0.001; FSFI only Hg [95% CI] = −0.37 [−0.56, −0.19], I2 = 83%, P < 0.001), and pain (combined not applicable; FSFI only [95% CI] Hg = −0.36 [−0.59, −0.13], I2 = 90%, P < 0.001), with lower scores for women with PCOS compared to control women (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots for subdomains with only the studies using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). (A) Desire, (B) arousal, (C) lubrication, (D) orgasm, (E) pain. ID, included study; Std. error, standard error; Df, degrees of freedom.

No differences were found for sexual desire (P = 0.06) with the FSFI only analyses.

Sexual satisfaction

Women with PCOS reported lower sexual satisfaction compared to control women in the analysis with the different questionnaires combined (Hg [95% CI] = −0.26 [−0.37, −0.15], I2 = 66%, P < 0.001) as well as for the analysis with only FSFI studies (Hg [95% CI] = −0.31 [−0.45, −0.18], I2 = 68%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C and D).

Subgroup analyses

Fertility status

In subgroup analyses by fertility status, results remained significant for total sexual function in the group with unknown fertility status (Hg [95% CI] = −0.25 [−0.36, −0.13], I2 = 31%, P < 0.001), with lower scores in PCOS versus controls. For both the fertile (Hg [95% CI] = −0.89 [−2.07, 0.29], I2 = 91%, P = 0.14) and the infertile groups (Hg [95% CI] = −1.62 [−3.51, 0.27], I2 = 100%, P = 0.09), results were not significant, but still showed the same pattern (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Only a single study (Aydogan Kirmizi et al., 2020) was represented in the fertile subgroup for all subdomains of sexual function, including desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm and pain, and for sexual satisfaction. Hence, there were no pooled results to accurately assess differences by fertility status for these outcomes. All results can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3.

BMI category

In subgroup analyses by BMI, results remained significant for total sexual function in the subgroups Overweight/Obese (OW/O) (Hg [95% CI] = −0.59 [−1.15, −0.03], I2 = 95%, P = 0.04) and Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.52 [−0.94, −0.10], I2 = 89%, P = 0.02) (Supplementary Fig. S3). For sexual satisfaction, lower satisfaction in PCOS was significant in all BMI subgroups, mixed (Hg [95% CI] = −0.21 [−0.37, −0.05], I2 = 60%, P = 0.01), OW/O (Hg [95% CI] = −0.30 [−0.55, −0.04], I2 = 79%, P = 0.02), and Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.29 [−0.50, −0.09], I2 = 64%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S3).

For the subgroup analyses of sexual function subdomains by BMI status, the pattern of results remained the same with PCOS showing lower scores then controls. Significant results were found in the subgroups arousal OW/O (Hg [95% CI] = −0.42 [−0.82, −0.01], I2 = 91%, P = 0.04), arousal Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.46 [−0.60, −0.31], I2 = 0%, P < 0.001), lubrication OW/O (Hg [95% CI] = −0.21 [−0.90, −0.08], I2 = 92%, P = 0.02), lubrication Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.88 [−1.42, −0.34], I2 = 91%, P < 0.001), orgasm mixed (Hg [95% CI] = −0.22 [−0.42, −0.02], I2 = 68%, P = 0.03), orgasm OW/O (Hg [95% CI] = −0.21 [−0.32, −0.10]), I2 = 0%, P < 0.001), orgasm Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.75 [−1.18, −0.31], I2 = 87%, P < 0.001), and pain Lean (Hg [95% CI] = −0.71 [−1.24, −0.19], I2 = 91%, P = 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis analysed 32 original studies on sexual function in women with PCOS and introduced a sensitivity analysis by questionnaire type as well as subgroup analyses by fertility and BMI status. Results show impaired sexual function in women with PCOS relative to control women. Women with PCOS scored lower on the total sexual function score, all sexuality questionnaire subdomains and on sexual satisfaction. Sensitivity analysis by questionnaire type and subgroup analyses by BMI and fertility status (where possible) did not dramatically alter the results. The quality of the present studies was low or moderate with low certainty of evidence for all outcomes.

Comparing the present results to other meta-analyses shows similar significant results between women with and without PCOS for arousal and lubrication (Zhao et al., 2019) and for pain and satisfaction scores (Loh et al., 2020). However, other studies did not find significant results for total sexual function scores (Murgel et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019), including after subgroup analyses by BMI and diagnostic criteria (Rotterdam) (Loh et al., 2020). Notably, all previous meta-analyses included only a few studies (four to six in total) with two of the reviews (Zhao et al., 2019; Loh et al., 2020) also including a secondary analysis of a large infertility trial (Diamond et al., 2017). This infertility trial required sexual intercourse three times a week and may not accurately represent sexual function in women with PCOS in the general population. Given the large sample size of this trial and its relative weighting on results, meta-analyses incorporating data from this trial may have biased sexual function scores in PCOS. Therefore, in our current and 2018 meta-analyses (Pastoor et al., 2018), we excluded the data from this large infertility trial (Diamond et al., 2017) in order to mitigate this potential bias. The study by Mansson et al. (2011) was also excluded for being an outlier on the orgasm scale which may have been due to only being able to use the orgasm frequency score and the finding that more women with PCOS took initiative for sexual behaviour then control women.

The present study showed some interesting results. Most unexpected were the findings that lean women with PCOS showed significantly lower results for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and pain (with lower scores indicating worse pain) when compared to women with PCOS in OW/O or mixed BMI groups. This is contrary to the common belief that women with obesity report lower sexual function. An explanation might be that body image is confounding for sexual function results. Body image is known to affect sexual function and sexual satisfaction (Woertman and van den Brink, 2012; van den Brink et al., 2013; Brotto et al., 2016; van den Brink et al., 2018), with reports in women with PCOS showing that body dissatisfaction is significantly negatively associated with sexual function and satisfaction (Kogure et al., 2019). Although lean women might not present body dissatisfaction, they seem to be more concerned with appearance and presentation and prefer a smaller ideal body (Makarawung et al., 2023). Additionally, several studies show that women in the underweight or normal weight group often estimate their body weight to be higher than it actually is (Takasaki et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2006). Although the VAS studies (Elsenbruch et al., 2003; Hahn et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2008; Caruso et al., 2009) indicate that self-esteem and attractiveness are lower in women with PCOS, the included questionnaire studies did not assess body image and self-esteem. It is however an intriguing area for further exploration in this context.

Additionally, in PCOS, insulin resistance is related to hyperandrogenism through multiple mechanisms including androgen production, binding, and bioavailability (Sarwer et al., 2018; Louwers and Laven, 2020). This may impact sexual function, however this is unclear as yet (Paulukinas et al., 2022). Although androgens play an important role in sexual function, the exact mechanisms by which they exert their influence and their relationship with female sexual function remain unclear (van Lunsen et al., 2018). Studies to date have been conflicting, with some reporting a relationship (Heiman et al., 2011; Islam et al., 2019; Maseroli and Vignozzi, 2022) while others not (Davis et al., 2005; Basson et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2020).

A second surprising finding was that fertility status did not seem to influence sexual function or satisfaction in the present results. Subgroup analyses did not change the results, with women with PCOS reporting lower sexual function then women without PCOS, irrespective of fertility status. Infertility is a common cause of sexual dysfunction and low sexual satisfaction in the general population (Starc et al., 2019), implying an additional effect of fertility status on sexual function. Since women with PCOS also often face subfertility (Louwers and Laven, 2020), the absence of an additional effect of fertility status might be explained by the fact that many PCOS characteristics and their comorbidities can influence sexual function, making it nearly impossible to establish the isolated effects of a single aspect. Moreover, a large number of the included studies did not clearly state the fertility status of their participants, leading to a single study in the fertile subgroup for most outcomes. This precluded accurate assessment of differences by fertility status, emphasizing the need for future studies to consider fertility status in their data collection and analysis protocols.

Finally, no differences in desire scores assessed with FSFI, the most used questionnaire in this meta-analysis, were found between women with and without PCOS, consistent with previous findings (Pastoor et al., 2018). The absence of a difference in desire suggests that women with PCOS, despite having lower sexual function on other domains, have as much sexual desire as women without PCOS. This corresponds with the low sexual satisfaction scores and might explain them. Also, this may indicate that perturbed endocrine function does not directly influence sexual desire as the relationship between androgen levels and sexual function is not yet fully understood. Studies assessing changes in androgen levels and their effects on sexual desire in women with PCOS further confirm no significant change in sexual desire or sexual thoughts after normalizing androgen levels using COCPs (Conaglen and Conaglen, 2003; Caruso et al., 2009; Steinberg Weiss et al., 2021) or metformin (Hahn et al., 2006; Gateva and Kamenov, 2012).

An important strength of this study is that it represents an extensive systematic quantitative analysis of the relationship between PCOS and sexual function including sensitivity and subgroup analyses. The studies included in this meta-analysis were carefully assessed for quality and the certainty across outcomes was assessed using the validated GRADE tool (Schunemann et al., 2000). Also, we included studies using all different PCOS diagnostic criteria to be able to report on the complete PCOS literature over time. Since these criteria are all similar to or based on the Rotterdam criteria, except for the NIH criteria, and we only used data for the complete PCOS group, we believe we have minimized any selection bias. Although all results pointed in the same direction, even after subgroup analyses, the certainty of evidence was low; hence, the evidence should be interpreted in light of this.

The main limitation of this study is that none of the included studies assessed true sexual ‘dys’ function, which relates to examining sexual distress stemming from low sexual function. Without assessing a distress score, it is difficult to interpret the meaning of the low sexual function scores for the women involved. Also, as is visible in the subgroup analyses, not all studies clearly stated the fertility status or BMI of their participants, making it difficult to interpret the effect of specific PCOS-related factors on sexual function scores. Additionally, not all ethnic populations (e.g. Asian) were represented which might limit generalization to the global PCOS population. Finally, we excluded non-English language studies and grey literature, hence publication bias cannot be ruled out. However, visual inspection of funnel plots did not give an indication of publication bias and sensitivity and subgroup analyses did not change the results.

To gain more reliable insights on the sexual function of women with PCOS, studies of higher quality are needed. Factors that could be improved include recruiting larger numbers of participants, using reliable assessments of PCOS diagnosis in both the PCOS and the control group, with clear inclusion criteria, comparable groups and assessment of sexual distress as a key outcome measure, alongside collection of key confounding variables including BMI, androgen status, and fertility status. Since sexual function as well as PCOS are biopsychosocial phenomena, study designs should incorporate a range of biopsychosocial assessments including questionnaires, endocrine measures, and genital response measures using psychophysiological tools. Ideally, the sexual function of partners and their relative distress should also be assessed.

To conclude, psychosexual function appears to be impaired in those with PCOS but there is a lack of evidence on the related distress scores which are required to meet the criteria for psychosexual dysfunction. Sexual distress seems to be high in women with PCOS as was shown in a recent study by our group, consequently leading to a high prevalence of sexual dysfunction (Pastoor et al., 2023). Health professionals should discuss sexual function and distress and be aware of the multiple factors that can influence psychosexual function in PCOS including infertility, excess weight, hirsutism, mood disorders, and PCOS medications. Psychosexual counselling has been shown to be effective in women with PCOS as well as in other populations (Golbabaei et al., 2019; Mashhadi et al., 2022; Tuncer and Oskay, 2022). Future research needs to assess both psychosexual function and distress concurrently before evidence-based clinical recommendations on routine assessment for psychosexual dysfunction can be made. Finally, future studies should include more diverse populations (e.g. non-heterosexual and more ethnically diverse groups) and focus on the range of different PCOS symptoms. Also, intervention studies on treatment effectiveness for sexual dysfunction (e.g. lifestyle and pharmacological interventions) are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr Reinier Timman, psychologist-methodologist (retired), Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, for performing the initial meta-analyses.

Contributor Information

Hester Pastoor, Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Aya Mousa, Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University and Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Hanneke Bolt, Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Wichor Bramer, Medical Library, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Tania S Burgert, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology, Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States.

Anuja Dokras, Penn Medicine, Penn Fertility Care, Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Chau Thien Tay, Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University and Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Helena J Teede, Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University and Monash Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Joop Laven, Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Human Reproduction Update online.

Data availability

This study uses secondary aggregate data from published studies; with no primary data collected for this study. All data underlying this article are available in the article tables and figures and in the online Supplementary Material.

Authors’ roles

H.P.: study design, execution of all parts of the study, critical discussion, writing and revising manuscript. A.M.: study design, performing meta-analyses and sensitivity and subgroup meta-analyses, GRADE assessments, critical revision of manuscript. H.B.: conducting systematic review, quality assessment of included studies, critical revision of manuscript. W.B.: design and execution literature search, critical revision of manuscript. T.B., A.D., C.T.T., H.J.T., J.L.: study design, critical revision of manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The funding was provided the Division of Reproductive Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands and the Centre for Research Excellence in Women’s Health in Reproductive Life (CRE-WHiRL), Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. A.M. and H.J.T. are supported by fellowships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia.

Conflict of interest

H.P., H.B., W.B., T.B., A.D., C.T.T., H.J.T.: none. J.L. received unrestricted research grants from the following companies (in alphabetical order): Ansh Labs, Ferring, Merck, and Roche Diagnostics. J.L. also received consultancy fees from Ansh Labs, Ferring, Gedeon Richter, and Titus Healthcare.

References

- Aba YA, Aytek Şik B.. Body image and sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2022;68:1264–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdo HCN. Development and validation of female sexual quotient—questionnaire to assess female sexual function. (Elaboracao e validacao do quociente sexual—versae feminina: uma escala para avaliar a funcao sexual da mulher). RBM Rev Bras Med 2006;63:477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari Sene A, Tahmasbi B, Keypour F, Zamanian H, Golbabaei F, Amini-Tehrani M.. Differences in and correlates of sexual function in infertile women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Fertil Steril 2021;15:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi M, Jahangiri N, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Mirzaei N, Gharagozloo Hesari N, Rostami F, Mousavi SS, Zeinaloo M.. Does prevalence of sexual dysfunction differ among the most common causes of infertility? A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2022;22:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydogan Kirmizi D, Baser E, Onat T, Demir Caltekin M, Yalvac ES, Kara M, Gocmen AY.. Sexual function and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: is it associated with inflammation and neuromodulators? Neuropeptides 2020;84:102099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azziz R, Carmina E, Chen Z, Dunaif A, Laven JS, Legro RS, Lizneva D, Natterson-Horowtiz B, Teede HJ, Yildiz BO.. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basirat Z, Faramarzi M, Esmaelzadeh S, Abedi Firoozjai SH, Mahouti T, Geraili Z.. Stress, depression, sexual function, and alexithymia in infertile females with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Int J Fertil Steril 2019;13:203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson R, Brotto LA, Petkau AJ, Labrie F.. Role of androgens in women’s sexual dysfunction. Menopause 2010;17:962–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetti-Pinto CL, Ferreira SR, Antunes A Jr, Yela DA.. The influence of body weight on sexual function and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;291:451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer W, Bain P.. Updating search strategies for systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 2017;105:285–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, Rosenbaum T, Abdo C, Byers ES, Graham C, Nobre P, Wylie K.. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med 2016;13:538–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso S, Rugolo S, Agnello C, Romano M, Cianci A.. Quality of sexual life in hyperandrogenic women treated with an oral contraceptive containing chlormadinone acetate. J Sex Med 2009;6:3376–3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo-Branco C, Naumova I.. Quality of life and sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive review. Gynecol Endocrinol 2020;36:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çetinkaya Altuntaş S, Çelik Ö, Özer Ü, Çolak S.. Depression, anxiety, body image scores, and sexual dysfunction in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome according to phenotypes. Gynecol Endocrinol 2022;38:849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ.. The Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ): development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33:731–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaglen HM, Conaglen JV.. Sexual desire in women presenting for antiandrogen therapy. J Sex Marital Ther 2003;29:255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney LG, Lee I, Sammel MD, Dokras A.. High prevalence of moderate and severe depressive and anxiety symptoms in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1075–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshfar Z, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Jahangiri N.. Comparison of sexual function in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed 2022;20:761–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Shaver PR, Widaman KF, Vernon ML, Follette WC, Beitz K.. “I can’t get no satisfaction”: insecure attachment, inhibited sexual communication, and sexual dissatisfaction. Pers Relationsh 2006;13:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell RJ.. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA 2005;294:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SR, Worsley R, Miller KK, Parish SJ, Santoro N.. Androgens and female sexual function and dysfunction—findings from the Fourth International Consultation of Sexual Medicine. J Sex Med 2016;13:168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz A, Kehribar DY.. Evaluation of sexual functions in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Niger J Clin Pract 2020;23:1548–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Francesco S, Caruso M, Robuffo I, Militello A, Toniato E.. The impact of metabolic syndrome and its components on female sexual dysfunction: a narrative mini-review. Curr Urol 2019;12:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, Alvero R, Robinson RD, Casson PA, Christman GM, Huang H, Hansen KR, Baker V, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Reproductive Medicine Network. Sexual function in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome and unexplained infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosdzol A, Skrzypulec V, Mazur B, Pawlińska-Chmara R.. Quality of life and marital sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2007;45Suppl 1:S93–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkhiat Y, Zedan A, Mostafa M, Elhalwagi A, Alhosini S.. Sexual desire in a sample of married Egyptian women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Hum Androl 2015;5:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Hahn S, Kowalsky D, Offner AH, Schedlowski M, Mann K, Janssen OE.. Quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5801–5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan CM, Coksuer H, Aydogan U, Alanbay I, Keskin U, Karasahin KE, Baser I.. Sexual dysfunction assessment and hormonal correlations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Impot Res 2013;25:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraresi SR, Lara LAS, Reis RM, de Sa Rosa e Silva ACJ.. Changes in sexual function among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. J Sex Med 2013;10:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateva A, Kamenov Z.. Sexual function in patients with PCOS and/or obesity before and after metformin treatment. ASM 2012;02:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Glowinska A, Duleba AJ, Zielona-Jenek M, Siakowska M, Pawelczyk L, Banaszewska B.. Disparate relationship of sexual satisfaction, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression with endocrine profiles of women with or without PCOS. Reprod Sci 2020;27:432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbabaei F, Jamshidimanesh M, Ranjbar H, Azin SA, Moradi S.. Efficacy of sexual counseling based on PLISSIT model on sexual functioning in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Maz Univ Med Sci 2019;29:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhammer DL, McCabe MP.. Development and psychometric properties of the Female Sexual Desire Questionnaire (FSDQ). J Sex Med 2011;8:2512–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S, Benson S, Elsenbruch S, Pleger K, Tan S, Mann K, Schedlowski M, van Halteren WB, Kimmig R, Janssen OE.. Metformin treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome improves health-related quality-of-life, emotional distress and sexuality. Hum Reprod 2006;21:1925–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S, Janssen OE, Tan S, Pleger K, Mann K, Schedlowski M, Kimmig R, Benson S, Balamitsa E, Elsenbruch S.. Clinical and psychological correlates of quality-of-life in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;153:853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Takimoto H, Yoshita K, Yoshiike N.. Perceived body size and desire for thinness of young Japanese women: a population-based survey. Br J Nutr 2006;96:1154–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman JR, Rupp H, Janssen E, Newhouse SK, Brauer M, Laan E.. Sexual desire, sexual arousal and hormonal differences in premenopausal US and Dutch women with and without low sexual desire. Horm Behav 2011;59:772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC.. A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res 1981;17:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Islam RM, Bell RJ, Green S, Page MJ, Davis SR.. Safety and efficacy of testosterone for women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trial data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:754–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joham AE, Norman RJ, Stener-Victorin E, Legro RS, Franks S, Moran LJ, Boyle J, Teede HJ.. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022;10:668–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kałużna M, Nomejko A, Słowińska A, Wachowiak-Ochmańska K, Pikosz K, Ziemnicka K, Ruchała M.. Lower sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and metabolic syndrome. Endocr Connect 2021;10:1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten MDA, Wekker V, Groen H, Painter RC, Mol BWJ, Laan ETM, Roseboom TJ, Hoek A.. The role of PCOS in mental health and sexual function in women with obesity and a history of infertility. Hum Reprod Open 2021;2021:hoab038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure GS, Ribeiro VB, Lopes IP, Furtado CLM, Kodato S, Silva de Sa MF, Ferriani RA, Lara L, Maria Dos Reis R.. Body image and its relationships with sexual functioning, anxiety, and depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Affect Disord 2019;253:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolotkin RL, Zunker C, Ostbye T.. Sexual functioning and obesity: a review. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:2325–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk R, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Nowosielski K, Lew-Starowicz Z.. Sexuality in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Ginekol Pol 2015;86:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara LAS, Ramos FKP, Kogure GS, Costa RS, Silva de Sá MF, Ferriani RA, dos Reis RM.. Impact of physical resistance training on the sexual function of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Sex Med 2015;12:1584–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh HH, Shahar MA, Loh HS, Yee A.. Female sexual dysfunction after bariatric surgery in women with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Surg 2022;111:14574969211072395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh HH, Yee A, Loh HS, Kanagasundram S, Francis B, Lim LL.. Sexual dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hormones (Athens) 2020;19:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwers YV, Laven JSE.. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). In: Petraglia F, Fauser BCJM (ed). Female Reproductive Dysfunction. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Makarawung DJS, Boers MJ, van den Brink F, Monpellier VM, Woertman L, Mink van der Molen AB, Geenen R.. The relationship of body image and weight: a cross-sectional observational study of a Dutch female sample. Clin Obes 2023;13:e12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansson M, Norstrom K, Holte J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E, Landen M.. Sexuality and psychological wellbeing in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with healthy controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;155:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzou D, Stamou MI, Armeni AK, Roupas ND, Assimakopoulos K, Adonakis G, Georgopoulos NA, Markantes GK.. Impaired sexual function in young women with PCOS: the detrimental effect of anovulation. J Sex Med 2021;18:1872–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maseroli E, Vignozzi L.. Are endogenous androgens linked to female sexual function? A systemic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2022;19:553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashhadi ZN, Irani M, Ghorbani M, Ghanzafarpour M, Nayyeri S, Ghodrati A.. The effects of counseling based on PLISSIT model on sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Health Med Sci 2022;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, Atalla E, Balon R, Fisher AD, Laumann E, Lee SW, Segraves RT.. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction among women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016;13:153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy NL. The McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2000;9:739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca CR, Arruda JT, Noll M, Campoli PMO, Amaral WND.. Sexual dysfunction in infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;215:153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner M, Esposito K, Guay A, Montorsi P, Goldstein I.. Cardiometabolic risk and female sexual health: the Princeton III summary. J Sex Med 2012;9:641–651; quiz 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojahed BS, Ghajarzadeh M, Khammar R, Shahraki Z.. Depression, sexual function and sexual quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and healthy subjects. J Ovarian Res 2023;16:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa A, Tay CT, Teede H.. Technical Report for the 2023 International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Murgel ACF, Simoes RS, Maciel GAR, Soares JM, Baracat EC.. Sexual dysfunction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2019;16:542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumova I, Castelo-Branco C, Casals G.. Psychological issues and sexual function in women with different infertility causes: focus on polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci 2021;28:2830–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomejko A, Dolińska-Zygmunt G.. The Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire—psychometric properties. Pol J Appl Psychol 2014;12:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Noroozzadeh M, Tehrani FR, Mobarakabadi SS, Farahmand M, Dovom MR.. Sexual function and hormonal profiles in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based study. Int J Impot Res 2016;29:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okobi OE. A systemic review on the association between infertility and sexual dysfunction among women utilizing female sexual function index as a measuring tool. Cureus 2021;13:e16006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastoor H, Both S, Laan E, Laven J.. Sexual dysfunction in women with PCOS: a case control study. Hum Reprod 2023;38:2230–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastoor H, Timman R, de Klerk C, Bramer WM, Laan ET, Laven JS.. Sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2018;37:750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulukinas RD, Mesaros CA, Penning TM.. Conversion of classical and 11-oxygenated androgens by insulin-induced AKR1C3 in a model of human PCOS adipocytes. Endocrinology 2022;163:bqac068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R.. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 2004;19:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland DL, McNabney SM, Mann AR.. Sexual function, obesity, and weight loss in men and women. Sex Med Rev 2017;5:323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwer DB, Hanson AJ, Voeller J, Steffen K.. Obesity and sexual functioning. Curr Obes Rep 2018;7:301–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A.. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using GRADE Approach. Cochrane. 2000. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html [Google Scholar]

- Sejourne N, Got F, Solans C, Raynal P.. Body image, satisfaction with sexual life, self-esteem, and anxiodepressive symptoms: a comparative study between premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women. J Women Aging 2019;31:18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafti V, Shahbazi S.. Comparing sexual function and quality of life in polycystic ovary syndrome and healthy women. J Fam Reprod Health 2016;10:92–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Fisher TD, Walter AS.. The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire: an objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Ann Sex Res 1993;6:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Starc A, Trampus M, Pavan Jukic D, Rotim C, Jukic T, Polona MA.. Infertility and sexual dysfunctions: a systematic literature review. Acta Clin Croat 2019;58:508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Weiss M, Roe AH, Allison KC, Dodson WC, Kris-Etherton PM, Kunselman AR, Stetter CM, Williams NI, Gnatuk CL, Estes SJ. et al. Lifestyle modifications alone or combined with hormonal contraceptives improve sexual dysfunction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2021;115:474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovall DW, Scriver JL, Clayton AH, Williams CD, Pastore LM.. Sexual function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Sex Med 2012;9:224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi SA, Aramesh S, Azizi-Kutenaee M, Allan H, Safarzadeh T, Taheri M, Salari S, Khashavi Z, Bazarganipour F.. The influence of infertility on sexual and marital satisfaction in Iranian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2021;26:2. [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki Y, Fukuda T, Watanabe Y, Kurosawa T, Shigekawa K.. Ideal body shape in young Japanese women and assessment of excessive leanness based on allometry. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci 2003;22:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Hahn S, Benson S, Janssen OE, Dietz T, Kimmig R, Hesse-Hussain J, Mann K, Schedlowski M, Arck PC. et al. Psychological implications of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2008;23:2064–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven J, Dokras A, Moran LJ, Piltonen TT, Costello MF, Boivin J, Redman LM, Boyle JA, et al. ; International PCOS Network. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018;38:1655–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuncer M, Oskay UY.. Sexual counseling with the PLISSIT model: a systematic review. J Sex Marital Ther 2022;48:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink F, Smeets MA, Hessen DJ, Talens JG, Woertman L.. Body satisfaction and sexual health in Dutch female university students. J Sex Res 2013;50:786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink F, Vollmann M, Smeets MAM, Hessen DJ, Woertman L.. Relationships between body image, sexual satisfaction, and relationship quality in romantic couples. J Fam Psychol 2018;32:466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lunsen RHW, Zimmerman Y, Coelingh Bennink HJT, Termeer HMM, Appels N, Fauser B, Laan E.. Maintaining physiologic testosterone levels during combined oral contraceptives by adding dehydroepiandrosterone: II. Effects on sexual function. A phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Contraception 2018;98:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woertman L, van den Brink F.. Body image and female sexual functioning and behavior: a review. J Sex Res 2012;49:184–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz Ç, Karakuş S, Bozoklu Akkar Ö, Şahin A, Bozkurt B, Yanik A.. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome adversely affects the female sexual function assessed by the female sexual function index: a case-control study. Arch Rheumatol 2017;32:123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Wang J, Xie Q, Luo L, Zhu Z, Liu Y, Luo J, Zhao Z.. Is polycystic ovary syndrome associated with risk of female sexual dysfunction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2019;38:979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Islam RM, Skiba MA, Bell RJ, Davis SR.. Associations between androgens and sexual function in premenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8:693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman Y, Eijkemans MJ, Coelingh Bennink HJ, Blankenstein MA, Fauser BC.. The effect of combined oral contraception on testosterone levels in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:76–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zueff LN, Lara LAdS, Vieira CS, Martins WdP, Ferriani RA.. Body composition characteristics predict sexual functioning in obese women with or without PCOS. J Sex Marital Ther 2015;41:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study uses secondary aggregate data from published studies; with no primary data collected for this study. All data underlying this article are available in the article tables and figures and in the online Supplementary Material.