Abstract

Objective

Few studies have investigated specific associations between insomnia and orofacial pain (OFP). The aim of this cross-sectional study was to examine relationships of insomnia with pain, mental health, and physical health variables among treatment-seeking patients with chronic OFP.

Methods

OFP diagnosis, demographics, insomnia symptoms, pain intensity, interference, and duration, mental health measures, and number of medical comorbidities were extracted from the medical records of 450 patients receiving an initial appointment at a university-affiliated tertiary OFP clinic. T-tests compared differences between patients with and without insomnia symptomatology, and between patients with different insomnia subtypes (delayed onset/early wakening).

Results

Compared to patients without insomnia, those with elevated insomnia symptomatology (45.1%) reported higher pain intensity (60.70 ± 20.61 vs 44.15 ± 21.69; P < .001) and interference (43.81 ± 29.84 vs 18.40 ± 23.43; P < 0.001), depression/anxiety symptomatology (5.53 ± 3.32 vs 2.72 ± 2.66; P < 0.001), dissatisfaction with life (21.63 ± 6.95 vs 26.50 ± 6.21; P < .001), and number of medical comorbidities (6.72 ± 5.37 vs 4.37 ± 4.60; P < .001). Patients with Sleep Onset Latency insomnia (SOL-insomnia) (N = 76) reported higher pain intensity (t = 3.57; P < 0.001), and pain interference (t = 4.46; P < .001) compared to those without SOL-insomnia. Those with Early Morning Awakening insomnia (EMA-insomnia) (N = 71) did not significantly differ from those without EMA-insomnia on any of the variables. Differences remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, primary OFP diagnosis, and pain intensity.

Conclusions

Insomnia is associated with pain outcomes and should be appropriately managed when treating patients with chronic OFP.

Keywords: insomnia, orofacial pain, delayed-sleep onset insomnia, early-awakening insomnia

A bidirectional relationship between chronic pain and poor sleep has been suggested, with longitudinal data indicating that sleep disturbances more strongly predict future pain intensity than pain intensity predicts future sleep disturbances.1,2 Sleep disturbances can be caused by several environmental and medical conditions, but primary insomnia emerges as one of the most common causes of persistent sleep disruption. While the prevalence of insomnia in the general population stands at 11.3%,3 it rises to up to 50% within chronic pain populations.2,4 Individuals with insomnia and non-cancer chronic pain (painful endometriosis, chronic lower back pain, migraine, etc) tend to report higher pain intensity compared to those without insomnia.5–7 However, only a few studies have examined sleep disorders in patients with orofacial pain (OFP).8–10 An association between self-reported OFP and high level of sleep disturbance was reported in a population-based study, conducted through mailed questionnaires,8 and a correlation has been described between poor sleep quality and fatigue in patients with some subtypes of OFP.9 A recent review suggested that insomnia treatment can improve chronic OPF.10 In summary, these studies suggest a vicious cycle wherein pain contributes to sleep difficulties that, in turn, further exacerbate OFP complaints. Yet to our knowledge, no study has examined how clinically significant insomnia symptomatology directly contributes to pain outcomes above and beyond pain intensity. Understanding how insomnia contributes to OFP is important, especially since patients with OFP commonly experience issues like sleep bruxism, emotional stress, anxiety/depression, all of which can contribute to sleep disruption. Furthermore, insights into insomnia within the context of OFP can highlight potential treatment targets, considering that cognitive behavioral therapy, a suggested first-line insomnia treatment for primary insomnia,11 has demonstrated efficacy in improving insomnia symptoms in chronic pain.12

Insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for developing new-onset temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and symptom flares in individuals with chronic pain.6,13 Diagnostic criteria for primary insomnia encompass difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early (among others), potentially leading to insomnia diagnosis even when sleep duration is not necessarily shortened (defined as <7 hours/night).14 Insomnia can be categorized into subtypes based on self-report specific criteria.15 Sleep Onset Latency insomnia (SOL-insomnia) is identified when there is a longer than 30 minutes SOL on 3 days per week for more than 1 month. Early Morning Awakening insomnia (EMA-insomnia) is defined by early morning awakenings lasting more than 30 minutes on 3 days per week for over 1 month. A combination of these subtypes is also possible.15 Different insomnia subtypes have been suggested to impact differently disease progression.15 For example, insomnia with shorter sleep duration is proposed as a more biologically severe disturbance,16 while SOL-insomnia may reflect a higher level of hyperarousal and stress-related sleep reactivity.17 However, the effects of insomnia subtypes on chronic OFP remain inadequately explored. Thus, comparing various insomnia subgroups within OFP patients can provide valuable insights into potential differences in biopsychological functioning.

Insomnia has also been linked with mental health problems such as anxiety/depression.18 As high as 80% of people with depression report insomnia symptomatology,19 and those with insomnia are at higher risk of developing new or exacerbating existing anxiety/depression episodes.20 Notably, insomnia treatments have been found to improve mood,21 and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) may be as or more effective in managing depression than conventional depression treatments.22 Finally, insomnia has been associated to increased risk of inflammatory23 and cardio-metabolic diseases,24 among other medical conditions.25 Given these associations, it is important to determine how insomnia symptoms may be specifically associated with mental/physical health symptoms in patients with chronic OFP.

To our knowledge, no study to date has specifically explored whether the presence of significant insomnia symptoms corresponds to specific measures of pain, mental, and physical health in patients with chronic OFP. That is, are patients with OFP and insomnia more likely to present higher pain intensity, higher pain-related interference with daily activities, higher likelihood of anxiety/depression, or more medical comorbidities than patients with OFP without insomnia? And if so, are these relationships explained by pain intensity? Finally, are different insomnia subtypes associated with different outcomes? Answers to these questions may suggest that insomnia treatment could improve pain, mental, and physical health in certain patients with chronic OFP. These data could impact the approach to screening insomnia in patients with OFP and contribute to developing more effective multidisciplinary interventions that address both sleep and pain, rather than solely pain management.

The primary aim of this study is to quantify the relationship between insomnia symptomatology and pain, mental, and physical health variables in a cross-sectional sample of treatment-seeking patients with chronic OFP. We will examine these relationships with and without controlling for pain intensity. We hypothesize that patients with OFP with insomnia will present with higher pain intensity and interference, worse mental health outcomes (depression/anxiety symptoms, satisfaction with life), and greater number of medical comorbidities than patients without significant insomnia symptomatology. Our secondary aim is to compare insomnia subtypes on the abovementioned variables. Specifically, we will compare variables between those with SOL-insomnia and EMA-insomnia as these subtypes have been previously linked to different pain outcomes.15,26 We hypothesize that patients with OFP with SOL-insomnia will present with worse outcomes than those without SOL-insomnia or with EMA-insomnia. Finally, because OFP disorders are heterogenous in nature, we will explore if the aforementioned relationships are different within each International Classification of Orofacial Pain (ICOP) diagnostic category.27 Because this aim is exploratory, we do not have any a priori hypotheses.

Methods

Procedures

As part of routine clinical care, all new patients seen at the OFP Clinic completed a battery of psychological and pain questionnaires and underwent a thorough clinical examination according to DC/TMD protocol.28 Patients were examined by an OFP resident, and OFP diagnoses were provided by an OFP specialist based on the ICOP classification,27 consisting of ICOP-code 1: Orofacial pain attributed to disorders of dentoalveolar and anatomically related structures; code 2: Myofascial orofacial pain; code 3: Temporomandibular joint pain; code 4: Orofacial pain attributed to lesion/disease of cranial nerves; code 5: Orofacial pains resembling presentations of primary headaches; and code 6: Idiopathic orofacial pain.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were adults between 18 and 80 years old, seeking treatment for an OFP complaint at an OFP Clinic, with a pain duration >3 months, able to speak English language, and willing to provide complete data at baseline. Subjects were excluded if they reported pain duration of <3 months, were <18 or >80 years of age (as questionnaires have not been validated in these age groups), or provided incomplete data in their baseline intake forms.

A retrospective medical chart review was conducted for all adult patients seen for an initial appointment at the university-affiliated tertiary OFP clinic between November 2020 and March 2023. This study was approved by the local IRB (IRB number 54563).

Outcomes

The following data were extracted:

Demographics consisted in age (years) and biological sex (male, female).

Insomnia symptomatology was assessed through the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a 7-item validated questionnaire referring to sleep difficulties in the prior 2 weeks. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0=“none” to 4=“very severe” for the first 3 questions; 0=“very satisfied” to 4=“very dissatisfied” for the remaining 4 questions). Summing all items yielded a total score of 0 to 28, with higher scores identifying increased insomnia symptomatology (α = 0.90). A cut-off of ISI ≥ 11 was used to suggest clinical insomnia symptoms.29 A value of 1 was assigned to those scoring ≥11 on the ISI, and a value of 0 was assigned to those scoring <11.

Patients with high insomnia symptomatology were classified based on self-reported symptoms of insomnia15 as SOL-insomnia (coded as 1) if they reported “severe” or “very severe” to the ISI-item assessing difficulty falling asleep (or as no SOL-insomnia, coded as 0, if they reported “none”, “mild” or “moderate” difficulty falling asleep). They were classified as EMA-insomnia (coded as 1) if they reported “severe” or “very severe” problems on the ISI-item assessing difficulty with waking up too early (or as no EMA-insomnia, coded as 0, if they reported “none”, “mild,” or “moderate” problem waking up too early).

Pain variables consisted of pain duration (months), pain intensity, and pain-related interference. Pain intensity and pain-related interference were assessed using the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) as recommended by DC/TMD protocol Axis II.28,30 A numeric pain scale for pain intensity ranged from 0=“no pain” to 10=“worst imaginable pain”. Patients were asked to provide values reflecting “pain right now,” “worse pain in the last 30 days,” and “average pain in the last 30 days.” Means of these 3 items were computed and multiplied by 10, thus obtaining a score indicating Characteristic Pain Intensity (CPI). CPI values ranged from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating greater pain intensity (α=0.88). Pain-related interference with “usual activities in the last 30 days,” “recreational, social and family activities in the last 30 days,” and “ability to work in the last 30 days” were assessed with a numeric pain scale, ranging from 0=“no interference” to 10=“unable to carry on any activities.” Means of the 3 items was computed and multiplied by 10, resulting in pain interference scores of 0 to 100. Higher values indicated higher pain interference (α = 0.95).

Anxiety/depression symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), a validated screening instrument to measure anxiety/depression symptomatology.31,32 The questionnaire consisted of 4 items on a 4-point Likert scale assessing frequency of anxiety and depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Scores ranged from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity (α = 0.86)

Satisfaction with life was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS),33 a 5-item questionnaire that assesses overall life satisfaction. Answers were provided on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). A total score between 5 and 35 was computed by summing all items, with higher values indicating greater life satisfaction (α=0.90).

Number of medical comorbidities was assessed by giving participants a checklist of 96 comorbidities and having them mark yes/no on whether they had those comorbidities or not. Marked comorbidities were confirmed by the dental residents with each patient during the examination. The number of medical comorbidities received prior to the appointment was extracted as continuous variable.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations were computed for all study variables. Bivariate correlations were computed to examine shared variance among continuous variables.

To test our primary aim, independent t-tests were used to compare patients with and without insomnia symptomatology on all study variables. Effect sizes between groups were computed using Cohen’s D. We reran significant models as ANCOVA to control for confounding factors of age, sex, and pain intensity (for models where pain intensity was not the dependent variable). If differences between those with and without insomnia symptomatology were found on pain intensity or pain interference, we ran regression models to test if this difference was explained by psychological factors. Specifically, we used a -step regression model with either pain intensity or pain interference as the dependent variable. We added the dichotomous group variable in the first step (0 = no insomnia, 1 = insomnia). In the second step we added the anxiety/depression symptom variable and the satisfaction with life variable. The outcome of interest was the standardized beta of the group variable in the second step.

To test our secondary aim, independent t-tests were used to compare patients with and without SOL-insomnia, and those with and without EMA-insomnia. Effect sizes between groups were computed using Cohen’s D and significant models were rerun as ANCOVA to control for confounding factors of age, sex, and pain intensity (for models where pain intensity was not the dependent variable).

To test our tertiary (exploratory aim), we repeated all analyses from Aims 1 and 2 6 times, once for each ICOP category.

P values for each test were determined by Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. Data were analyzed with SPSS (IBM SPSS, v27, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All missing data was handled using pairwise deletion (ie, we used all data available for each variable).

Results

Four hundred-fifty patients (82.2% females) were included, with a mean age 44.63 ± 15.98 years, mean pain duration 74.35 ± 106.33 months, and mean pain intensity 51.68 ± 22.73. Of them, 56.2% received a myofascial pain diagnosis, 22.9% an articular diagnosis, 10.9% neuropathic pain, 5.3% primary headache, 3.3% dentoalveolar pain, and 1.3% idiopathic orofacial pain. Table 1 shows demographic, pain, and psychological variables of the total sample. Two-hundred three patients (45.1%) presented with clinically elevated insomnia.

Table 1.

Demographics, anamnestic data, pain and psychological outcomes of the total sample (N = 450), and comparison between patients with (ISI ≥ 11) and without clinically elevated insomnia (ISI < 11).

| Total | Clinically elevated insomnia | Not clinically elevated insomnia | P value | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 450) | (N = 203) | (N = 247) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 44.6 ± 15.9 | 44.6 ± 15.3 | 44.6 ± 16.6 | .98 | −2.94, 3.01 | |

| Biological sex (N, %) | ||||||

| Female | 370 (82.2%) | 169 (83.3) | 201 (81.4) | .62 | −5.31, 8.87 | |

| Male | 80 (17.8%) | 34 (16.7%) | 46 (18.6) | |||

| Pain variables (mean, SD) | ||||||

| Pain intensity (GCPS) | 51.68 ± 22.73 | 60.70 ± 20.06 | 44.15 + 21.69 | <.001 | 12.57, 20.53 | 0.79 |

| Pain interference (GCPS) | 29.92 ± 29.37 | 43.81 ± 29.84 | 18.40 ± 23.43 | <.001 | 20.43, 30.40 | 0.95 |

| Psychological outcomes (mean, SD) | ||||||

| Anxiety/depression (PHQ-4) | 3.94 ± 3.27 | 5.52 ± 3.32 | 2.72 ± 2.66 | <.001 | 2.23, 3.39 | 0.93 |

| Satisfaction with Life (SWLS) | 24.36 ± 6.97 | 21.63 ± 6.95 | 26.50 ± 6.21 | <.001 | −6.17, −3.57 | 0.74 |

| General Health | ||||||

| Medical comorbidities (mean N, SD) | 5.43 ± 5.10 | 6.72 ± 5.37 | 4.37 ± 4.60 | <.001 | 1.43, 3.28 | 0.47 |

Significance is denoted by bolded font.

CI = Confidence Interval; GCPS = Graded Chronic Pain Scale; ICOP = International Classification of Orofacial Pain; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; N = Number; PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SD = Standard deviation; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Aim 1—Comparison between patient with and without clinically elevated insomnia in pain and psychological variables.

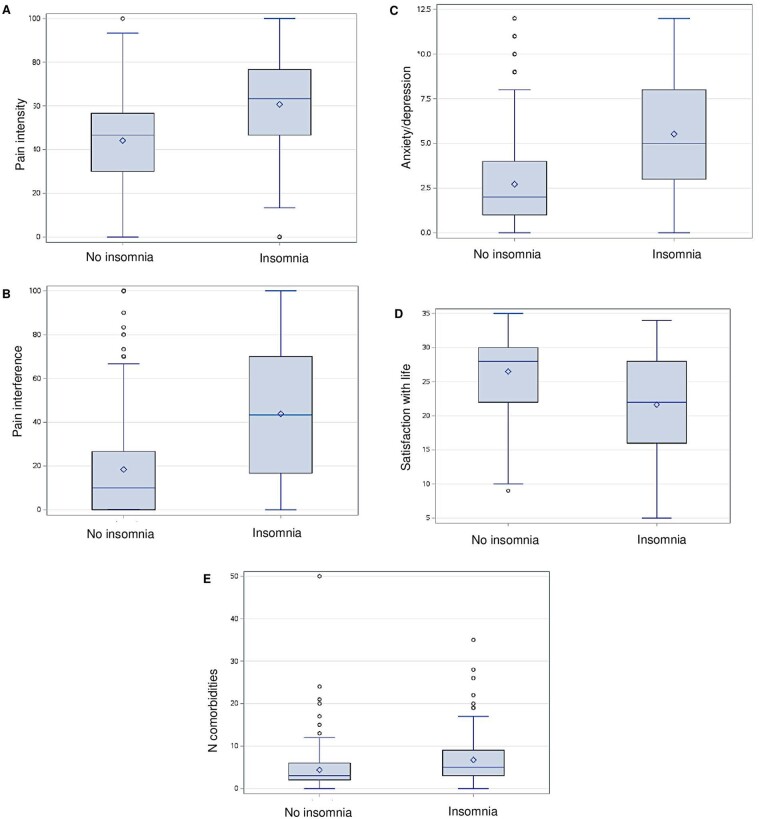

Table 1 shows the comparison between patients with and without clinically elevated insomnia. Patients with clinically elevated insomnia did not differ from those without clinically elevated insomnia in regard to age (44.6 ± 15.3 vs 44.6 ± 16.6, P = .98) or sex (83.3% vs 81.4% females, P = .62). Patients with clinically elevated insomnia presented with higher pain intensity (60.70 ± 20.61 vs 44.15 ± 21.69; t = −8.17; P < .001; Figure 1A), greater pain interference (43.81 ± 29.84 vs 18.40 ± 23.43; t = −10.02; P < .001; Figure 1B), greater anxiety/depression symptomatology (5.53 ± 3.32 vs 2.72 ± 2.66; t = −9.54; P < 0.001; Figure 1C), lower satisfaction with life (21.63 ± 6.95 vs 26.50 ± 6.21; t = 7.40; P < .001; Figure 1D), and a greater number of medical comorbidities (6.72 ± 5.37 vs 4.37 ± 4.60; t = −5.00; P < .001; Figure 1E) compared to those without insomnia. Pain duration did not significantly differ between the 2 groups (81.45 ± 110.80 vs 68.66 ± 102.49; t = −1.26; P = .33). Cohen’s D reveals that effect sizes between the groups were moderate to large (Table 1). Group differences remained significant after controlling for covariates of age and sex. The results on pain interference, anxiety/depression symptomatology, satisfaction with life, and medical comorbidities remained significant after controlling for pain intensity, and even after using a Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Additionally, after controlling for anxiety/depression symptoms and satisfaction with life, the group between those with and without insomnia remained significant for both pain intensity (β = 0.30, t = 5.74, P < .001) and pain interference (β = 0.31, t = 6.21, P < .001).

Figure 1.

Box plots display statistically significant differences between patients with (ISI ≥ 11) and without (ISI < 11) clinically elevated insomnia symptoms in pain intensity (A), pain interference (B), anxiety/depression (C), satisfaction with life (D), and number of medical comorbidities (E). [ISI = Insomnia Severity Index].

Aim 2—Comparison between different insomnia subtypes in pain and psychological variables.

Table 2 presents the differences in variables among different insomnia subtypes. Among patients with clinically elevated insomnia, those with SOL-insomnia (N = 76) presented with higher pain intensity (67.2 ± 20.2 vs 56.8 ± 19.0; t = 3.57; P < .001), pain interference (55.4 ± 24.7 vs 36.8 ± 28.4; t = 4.46; P < .001), anxiety/depression symptomatology (6.5 ± 3.2 vs 5.0 ± 3.2, t = 2.91; P = .004), and dissatisfaction with life (19.9 ± 7.5 vs 22.7 ± 6.4, t = 2.62; P = .010) compared to those without SOL-insomnia. The 2 groups did not differ in number of medical comorbidities (7.6 ± 6.1 vs 6.2 ± 4.8, t = 1.91; P = .058). Group differences remained significant after controlling for demographics and pain intensity. After applying Holm-Bonferroni correction, statistically significant differences in anxiety/depression symptoms and dissatisfaction with life were no longer significant.

Table 2.

Comparison between different patients with clinical insomnia (203 patients), evaluated by different insomnia subtypes: SOL (delayed sleep-onset) vs non-SOL; and EMA (early morning insomnia) vs non-EMA.

| SOL | Non-SOL | P value (95% CI) | Cohen’s d | EMA | Non-EMA | P value (95% CI) | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 76) | (N = 127) | |||||||

| (N = 71) | (N = 132) | |||||||

| Pain intensity (GCPS) | 67.2 ± 20.2 | 56.8 ± 19.0 | <.001 (4.65, 16.14) | 0.53 | 63.4 ± 21.9 | 59.2 ± 19.8 | 0.171 (−1.83, 10.18) | 0.20 |

| Pain interference (GCPS) | 55.4 ± 24.7 | 36.8 ± 28.4 | <.001 (10.37, 26.80) | 0.70 | 48.4 ± 31.8 | 41.4 ± 28.6 | 0.114 (−1.70, 15.74) | 0.23 |

| Anxiety/depression (PHQ-4) | 6.5 ± 3.2 | 5.0 ± 3.2 | .004 (.47, 2.47) | 0.47 | 6.2 ± 3.1 | 5.2 ± 3.4 | 0.057 (−0.03, 1.99) | 0.31 |

| Satisfaction with Life (SWLS) | 19.9 ± 7.5 | 22.7 ± 6.4 | .010 (−4.90, −.69) | 0.40 | 20.9 ± 7.5 | 22.0 ± 6.6 | 0.300 (−3.30, 1.02) | 0.16 |

| Medical comorbidities (mean N, SD) | 7.6 ± 6.1 | 6.2 ± 4.8 | .058 (−2.92, .12) | 0.26 | 7.4 ± 6.1 | 6.4 ± 4.9 | 0.230 (−2.55, 0.55) | 0.18 |

Significance was denoted by bolded font.

CI = Confidence Interval; GCPS = Graded Chronic Pain Scale; N = Number; PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SD = Standard deviation; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Conversely, those with EMA-insomnia (N = 71) did not significantly differ from those without EMA-insomnia on any of the variables.

Aim 3—Comparison among each OFP diagnosis.

Table 3 displays the difference between patients with and without insomnia in selected outcomes according to ICOP diagnoses. After adjusting for multiple corrections, among patients diagnosed with myofascial pain, articular pain, and neuropathic pain those with clinically elevated insomnia exhibited significantly higher pain intensity, pain-related interference, and anxiety/depression. Satisfaction with life was significantly lower in those with clinically elevated insomnia diagnosed with myofascial, articular pain, and primary headache. Among those with primary headache, those with clinically elevated insomnia had significantly greater pain-interference than those without. The number of comorbidities was significantly higher in patients with clinically elevated insomnia diagnosed with articular pain compared to those without clinically elevated insomnia. No other significant difference was seen between patients with and without insomnia according to ICOP diagnoses of dentoalveolar pain and idiopathic orofacial pain.

Table 3.

Difference in pain, psychological variables and anamnestic data between patients with (ISI ≥ 11) and without clinically elevated insomnia (ISI < 11) according to ICOP diagnoses.

| Outcome | Insomnia symptoms | Dentoalveolar pain | Myofascial pain | Articular pain | Neuropathic pain | Primary headache | Idiopathic orofacial pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ICOP 1) | (ICOP 2) | (ICOP 3) | (ICOP 4) | (ICOP 5) | (ICOP 6) | ||

| (N = 15) | (N = 253) | (N = 103) | (N = 49) | (N = 24) | (N = 6) | ||

| Pain intensity (GCPS) | Insomnia | 42.50 ± 29.49 | 59.46 ± 47.74 | 59.72 ± 21.33 | 66.40 ± 22.93 | 72.50 ± 14.57 | 53.33 ± 26.03 |

| No insomnia | 42.42 ± 28.44 | 47.74 ± 18.76 | 37.90 ± 22.08 | 41.74 ± 25.40 | 56.97 ± 17.73 | 43.33 ± 41.77 | |

| P value | 0.996 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.032 | 0.743 | |

| Pain interference (GCPS) | Insomnia | 35.00 ± 35.54 | 40.11 ± 28.60 | 41.94 ± 29.42 | 55.07 ± 34.12 | 70.83 ± 16.46 | 31.11 ± 20.09 |

| No insomnia | 30.91 ± 40.28 | 20.86 ± 23.88 | 11.43 ± 15.99 | 21.01 ± 26.04 | 21.51 ± 24.38 | 24.44 ± 39.49 | |

| P value | .861 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .807 | |

| Anxiety/depression (PHQ-4) | Insomnia | 6.00 ± 5.20 | 5.43 ± 3.20 | 5.32 ± 3.60 | 6.00 ± 3.68 | 5.92 ± 3.58 | 5.33 ± 1.53 |

| No insomnia | 1.91 ± 2.81 | 2.90 ± 2.54 | 2.64 ± 2.75 | 2.65 ± 2.96 | 1.70 ± 2.16 | 4.67 ± 3.21 | |

| P value | .084 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .004 | .762 | |

| Satisfaction with Life (SWLS) | Insomnia | 23.25 ± 4.03 | 21.63 ± 7.58 | 21.41 ± 6.01 | 21.42 ± 6.31 | 20.17 ± 4.09 | 28.00 ± 2.65 |

| No insomnia | 28.09 ± 5.17 | 25.99 ± 21.63 | 27.14 ± 5.88 | 25.61 ± 5.56 | 31.11 ± 5.99 | 16.33 ± 5.01 | |

| P value | .116 | <.001 | <.001 | .012 | <.001 | .030 | |

| N medical comorbidities (mean, SD) | Insomnia | 7.5 ± 4.12 | 6.67 ± 5.80 | 6.76 ± 4.10 | 7.60 ± 5.50 | 5.42 ± 5.99 | 5.3 ± 3.21 |

| No insomnia | 3.80 ± 2.70 | 4.87 + 5.68 | 3.69 ± 3.37 | 4.33 ± 3.16 | 3.83 ± 3.10 | 6.00 ± 3.00 | |

| P value | .068 | .014 | <.001 | .007 | .232 | .806 |

Significance was denoted by bolded font. GCPS = Graded Chronic Pain Scale; ICOP = International Classification of Orofacial Pain; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; N = Number; PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire; SD: Standard deviation; SWLS: Satisfaction With Life Scale.

Discussion

Insomnia remains largely unstudied in OFP, particularly in treatment-seeking populations. We found that over 45% of patients presented with clinically elevated insomnia, and those who presented with elevated insomnia reported higher pain intensity, greater pain-related interference, higher anxiety/depression symptomatology, poorer satisfaction with life, and poorer general health (as indexed by greater medical comorbidities), when compared to those without clinical insomnia symptomatology. The insomnia group reported >15 points higher on pain intensity (on a 100-point scale), nearly 25 points higher on pain interference (on a 100-point scale), and nearly 3 points higher on anxiety/depression (on a 12-point scale) than the group without insomnia. The magnitude of these difference is very likely clinically significant and may be strongly influencing how patients with insomnia and chronic pain may function throughout the day. Our findings confirm the association between insomnia and pain intensity previously reported for other chronic pain conditions. However, the present study found a larger effect size compared to studies conducted in other pain populations,10 suggesting that the relationship between sleep and pain presents a similar nature,34 but may differ in magnitude depending on the type of pain, sample size, and type of examination. Initial-month increases in insomnia were associated with next-month increases in average daily pain in TMD.35 Other studies36 observed that primary insomnia was associated with reduced mechanical and thermal pain thresholds, suggesting that insomnia could be linked with central sensitivity.37 Others found that poor sleep predicted pain intensity and pain catastrophizing in those with TMD.38 Taken together, these studies corroborate our findings that poor sleep can influence how patients may be experiencing pain intensity and could possibly explain the finding that no statistically significant difference was observed in mean pain duration between patients with and without clinically elevated insomnia.

Similarly, the current study found that patients with insomnia reported on average three-time greater pain interference when compared to patients without insomnia, and these differences remained even after controlling for pain intensity. The mechanisms underlying these relationships remain unclear. One possibility is that poor sleep may be contributing to daytime sleepiness and/or fatigue that may be impairing ability to function,9 or that sleep may impact cognitive functioning which may then be leading to greater disability. It may also be the case that insomnia is exacerbating mental health symptoms, which may lead to greater interference.39,40 A recent review found that insomnia may be a risk factor and transdiagnostic symptom for many mental disorders including mood/anxiety disorders,41 and the current study found significant differences in anxiety/depression symptomatology between patients with and without insomnia. It may also be the case that other factors may influence both insomnia and pain interference. Considering the link between insomnia and psychological health, our results underscore the need for comprehensive assessment and interventions that address both sleep disturbances and psychological outcomes in patients with chronic OFP. Given that CBT-I is effective in improving insomnia symptoms across different subtypes and is also known to positively impact mood and overall health,42 it stands as a promising avenue for addressing the multifaceted impact of insomnia in chronic OFP. Insomnia and sleep disturbances are correlated to increased pain intensity in that they reduce pain threshold and magnify pain signal transmission. This leads to increased attention to pain and altered function, ultimately contributing to the reinforcement of negative emotions and psychological responses centered around pain.43 By changing maladaptive sleep-related behaviors and cognitions, it may potentially break the vicious cycle of pain that led to sleep difficulties, and vice versa.43

Our findings also suggested that patients with elevated insomnia exhibited greater number of medical conditions compared to those without clinical insomnia. This is in accordance with other studies where people with insomnia were more likely than those without insomnia to report comorbidities like cardiovascular, neurological, and respiratory disease, among others.4 Additionally, insomnia could worsen the symptomatology of people with chronic comorbidities, and insomnia has been suggested to impair immune function and brain health, thus further aggravating chronic conditions.44 Likely, there are multiple mechanisms by which insomnia may place people at risk for worse health, and these mechanisms should be further explored.

Not all insomnia is the same. After controlling for multiple correction, our data revealed that patients reporting SOL-insomnia presented with higher pain intensity and pain-related interference compared to those without SOL-insomnia. These data corroborate another study which found that delayed sleep-onset-latency was strongly associated with the risk of spinal pain,26 as well as with the finding that morning types are less sensitive to pain.45 The mechanisms underlying these findings are unknown, but it appears clear that not all insomnia is the same and that future studies should be conducted to better understand different insomnia subtypes.

When the analysis was repeated while controlling for ICOP diagnosis, all the outcomes remained significant among patients with myofascial and articular pain. It is well established that poor sleep predicts worse outcomes in patients with muscle pain, which our findings confirmed. However, what was somewhat unexpected was that patient with an articular and/or neuropathic diagnosis also reported significantly higher pain intensity (>20-point on a 100-point scale) in those with clinically elevated insomnia compared to those without. Similarly, significant differences were observed in pain interference (with a difference of 20–35 points on a 100-point scale), and anxiety/depression symptomatology (2.5 to 3.5 points on a 12-point scale). These results further support that assessing and effectively addressing insomnia symptoms across different OFP diagnoses can be beneficial for meaningful treatment. Conversely, we hypothesize that the lack of significant difference in the other OFP diagnoses may be attributed to the small sample size in those groups (N = 15 for ICOP 1, and N = 6 for ICOP 6). Therefore, these results should be validated with a larger sample size.

Strength and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze insomnia and pain comorbidities in a relatively large sample of treatment-seeking chronic OFP patients. The current study has some limitations. Most importantly, the cross-sectional design does not allow to draw any causal conclusions. Determining if insomnia is the cause of pain intensity, pain-related interference and all the other psychosocial variables assessed in this study would require longitudinal studies with within-person (ie, daily diary, actigraphy) components. Because the study was conducted only on individuals with chronic OFP, results may not generalize to patients with other chronic pain conditions. No data regarding other concomitant sleep comorbidities that could negatively impact sleep domain (eg, sleep apnea or periodic limb movements of sleep) were collected. Further studies with a more comprehensive sleep assessment are encouraged to better control for these potential comorbidities. Specifically, future studies should utilize more objective sleep measures (eg, actigraphy, polysomnography) as there are known discrepancies between subjective and objective sleep measures,46 and those with greater psychological distress may overreport subjective insomnia symptomatology.47,48 The sample was primarily females, reducing generalizability to males. Further studies with a more representative sample are needed. Finally, no information was extracted regarding medication use. Even though it would have been valuable to control for this factor, the lack of this information should not undermine the present results, given that our focus was on the subjective perception of sleep.

Despite these limitations the present study has considerable strengths. It reinforces the strong relationship between insomnia and chronic pain, presenting compelling data that not all insomnia is the same; rather, important subtypes of insomnia may be contributing to outcomes in OFP. Clinically, these results highlight the importance of insomnia screening in patients with OFP, and suggest that a new multidisciplinary-integrated approach is needed to increase the chances of success when managing patients with both pain and insomnia. This is particularly important given that behavioral treatments for insomnia (ie, CBT-I) are the gold-standard treatments and are usually short and effective.49,50 Utilizing these treatments to improve insomnia symptoms in patients with OFP has great potential to improve their overall quality of life. Although sleep disturbance in OFP had been investigated for decades, and the results largely support that sleep quality and quantity are related to pain and distress in OFP, to our knowledge no study has explicitly examined how clinically significant insomnia symptomatology directly contributes to pain outcomes above and beyond pain intensity. These data are important as insomnia screening is still not the standard of care in OFP, despite the findings that ISI questionnaire is a valid tool29 with several benefits. A wider understanding and screening of insomnia in OFP populations may lead to more effective multidisciplinary care targeting sleep and pain. Based on these results, we suggest for insomnia screening to be provided in all patients with OFP and for sleep disturbances to be addressed while treating pain conditions. This study also highlighted important variations based on the specific type of insomnia experienced, which could result in valuable insights to inform treatment considerations.

Contributor Information

Anna Alessandri-Bonetti, Division of Orofacial Pain, Department of Oral Health Science, University of Kentucky, College of Dentistry, Lexington, KY 40536, United States; Institute of Dental Clinic, A. Gemelli University Policlinic IRCCS, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Rome 00168, Italy.

Linda Sangalli, College of Dental Medicine—Illinois, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL 60515, United States.

Ian A Boggero, Division of Orofacial Pain, Department of Oral Health Science, University of Kentucky, College of Dentistry, Lexington, KY 40536, United States; Department of Psychology, University of Kentucky, College of Dentistry, Lexington, KY 40536, United States; Department of Anesthesiology, University of Kentucky, College of Medicine, Lexington, KY 40536, United States.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DE031807. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Chang JR, Fu S-N, Li X, et al. The differential effects of sleep deprivation on pain perception in individuals with or without chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;66:101695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT.. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aernout E, Benradia I, Hazo JB, et al. International study of the prevalence and factors associated with insomnia in the general population. Sleep Med. 2021;82:186-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, et al. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30(2):213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Souza RJ, Vilella NR, Pinho Oliveira MA.. The relationship between pain intensity and insomnia in women with deep endometriosis, a cross-sectional study. Sleep Breath. 2022;27(2):441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCracken LM, Iverson GL.. Disrupted sleep patterns and daily functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(2):75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravyts SG, Dzierzewski JM.. Pain experiences in individuals with reported and suspected sleep disorders. Behav Med. 2022;48(4):305-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Macfarlane TV, Worthington HV.. Association between orofacial pain and other symptoms: a population-based study. Oral Biosci Med. 2004;1(1):45-54. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boggero IA, Pickerill HM, King CD.. Fatigue in adults with chronic arthralgia/myalgia in the temporomandibular region: associations with poor sleep quality, depression, pain intensity, and future pain interference. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2022;36(2):155-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Almoznino G, Haviv Y, Sharav Y, Benoliel R.. An update of management of insomnia in patients with chronic orofacial pain. Oral Dis. 2017;23(8):1043-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edinger JD, Arnedt JT, Bertisch SM, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):263-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Coryell VT, Smith MT.. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia and chronic pain. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9(2):261-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanders AE, Akinkugbe AA, Bair E, et al. Subjective sleep quality deteriorates before development of painful temporomandibular disorder. J Pain. 2016;17(6):669-e677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data-and-statistics/Adults.html#:∼:text=Short%20sleep%20duration%20is%20based,than%207%20hours%20for%20adults

- 15. Bjorøy I, Jørgensen VA, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B.. The prevalence of insomnia subtypes in relation to demographic characteristics, anxiety, depression, alcohol consumption and use of hypnotics. Front Psychol. 2020;11:527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, Bixler EO.. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(4):241-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, Drake CL.. Identifying at-risk individuals for insomnia using the ford insomnia response to stress test. Sleep. 2016;39(2):449-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K.. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):e1160-e1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Asarnow LD, Manber R.. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in depression. Sleep Med Clin. 2019;14(2):177-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gebara MA, Siripong N, DiNapoli EA, et al. Effect of insomnia treatments on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):717-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carney CE, Edinger JD, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Cognitive behavioral insomnia therapy for those with insomnia and depression: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2017;40(4):zsx019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE.. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(1):40-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan MS, Aouad R.. The effects of insomnia and sleep loss on cardiovascular disease. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(2):167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dikeos D, Georgantopoulos G.. Medical comorbidity of sleep disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(4):346-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skarpsno ES, Mork PJ, Marcuzzi A, Nilsen TIL, Meisingset I.. Subtypes of insomnia and the risk of chronic spinal pain: The HUNT study. Sleep Med. 2021;85:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st edition (ICOP) . Cephalalgia. 2020;40(2):129-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. ; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research, Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain (2014) Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H.. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF.. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B.. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1-2):86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S.. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson KG, Watson ST, Currie SR.. Daily diary and ambulatory activity monitoring of sleep in patients with insomnia associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 1998;75(1):75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quartana PJ, Wickwire EM, Klick B, Grace E, Smith MT.. Naturalistic changes in insomnia symptoms and pain in temporomandibular joint disorder: a cross-lagged panel analysis. PAIN. 2010;149(2):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith MT, Wickwire EM, Grace EG, et al. Sleep disorders and their association with laboratory pain sensitivity in temporomandibular joint disorder. Sleep. 2009;32(6):779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Brien EM, Waxenberg LB, Atchison JW, et al. Intraindividual variability in daily sleep and pain ratings among chronic pain patients: bidirectional association and the role of negative mood. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(5):425-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buenaver LF, Quartana PJ, Grace EG, et al. Evidence for indirect effects of pain catastrophizing on clinical pain among myofascial temporomandibular disorder participants: the mediating role of sleep disturbance. Pain. 2012;153(6):1159-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1-3):10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Soehner AM, Harvey AG.. Prevalence and functional consequences of severe insomnia symptoms in mood and anxiety disorders: results from a nationally representative sample. Sleep. 2012;35(10):1367-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palagini L, Hertenstein E, Riemann D, Nissen C.. Sleep, insomnia and mental health. J Sleep Res. 2022;31(4):e13628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu JQ, Appleman ER, Salazar RD, Ong JC.. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with psychiatric and medical conditions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1461-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vitiello MV, Rybarczyk B, Von Korff M, Stepanski EJ.. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(4):355-362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sangalli L, Boggero IA.. The impact of sleep components, quality and patterns on glymphatic system functioning in healthy adults: a systematic review. Sleep Med. 2023;101:322-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jankowski KS. Morning types are less sensitive to pain than evening types all day long. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(7):1068-e1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Boggero IA, Schneider VJ, Thomas P, Nahman-Averbuch H, King CD.. Associations of self-report and actigraphy sleep measures with experimental pain outcomes in patients with temporomandibular disorder and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 2019;123:109730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Biddle DJ, Robillard R, Hermens DF, Hickie IB, Glozier N.. Accuracy of self-reported sleep parameters compared with actigraphy in young people with mental ill-health. Sleep Health. 2015;1(3):214-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rimmel K, Eder HG, Böck M, et al. The (mis)perception of sleep: factors influencing the discrepancy between self-reported and objective sleep parameters. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(5):917-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Selvanathan J, Pham C, Nagappa M, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whale K, Dennis J, Wylde V, Beswick A, Gooberman-Hill R.. The effectiveness of non-pharmacological sleep interventions for people with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;1123(1):440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]