SUMMARY

Neutrophils are important innate immune cells with plasticity, heterogenicity, and functional ambivalency. While bone marrow is often regarded as the primary source of neutrophil production, the roles of extramedullary production in regulating neutrophil plasticity and heterogenicity in autoimmune diseases remain poorly understood. Here, we report that the lack of wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 5 (WNT5) unleashes anti-inflammatory protection against colitis in mice, accompanied by reduced colonic CD8+ T cell activation and enhanced splenic extramedullary myelopoiesis. In addition, colitis upregulates WNT5 expression in splenic stromal cells. The ablation of WNT5 leads to increased splenic production of hematopoietic niche factors, as well as elevated numbers of splenic neutrophils with heightened CD8+ T cell suppressive capability, in part due to elevated CD101 expression and attenuated pro-inflammatory activities. Thus, our study reveals a mechanism by which neutrophil plasticity and heterogenicity are regulated in colitis through WNT5 and highlights the role of splenic neutrophil production in shaping inflammatory outcomes.

In brief

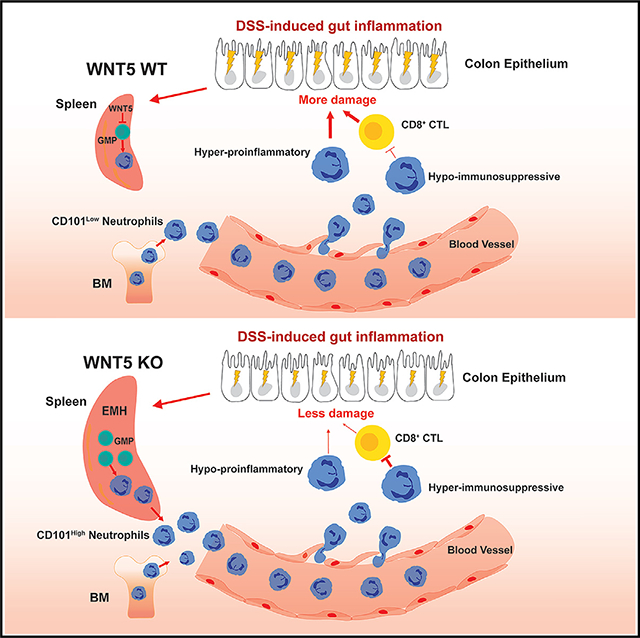

Luan et al. report that the absence of WNT5 proteins in mice increases, through splenic granulopoiesis, the production of CD101-high hyper-immunosuppressive and hypo-inflammatory neutrophils. These neutrophils protect the mice from DSS-induced colitis.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in human blood and the first to be recruited to the sites of inflammation.1–9 They play ambivalent roles in organismal well-being. While they are important for host defense against microbial infections, the products released by neutrophils upon activation can cause tissue damage. In addition, their immunosuppressive activity can be beneficial to some inflammation diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), although this activity can also promote tumor formation.10–13 The effects of neutrophils on disease outcomes are the summation of their detrimental vs. beneficial effects. This functional ambivalency of neutrophils is at least in part due to neutrophil plasticity and heterogenicity.1,2,6,14,15 Investigations on neutrophil plasticity and heterogenicity have been largely carried out in the context of tumor immunity.16–18 However, neutrophil plasticity and the functional roles of diverse neutrophil subpopulations in the context of non-tumor inflammation have been poorly investigated and understood.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, collectively known as IBD, are autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases. IBD affects millions of people worldwide, particularly in developed countries, and its etiology seems to be complex and attributed to a combination of environmental factors, defective immune responses, intestinal microbiota, and genetic susceptibility.19–21 The immune responses are important for the pathogenesis of the disease. Although CD4+ T cells play key roles in the initiation and progression of the disease, the conventional cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which have high granzyme B (GZMB) expression, primarily associate with mucosal damage and exacerbate pathogenesis during colitis.22–28 However, in different experimental models, subsets of CD8+ T cells that exhibit suppressive or regulatory roles within the immune system were also described. These CD8+ T cells have low GZMB expression but express anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and inhibitory receptors. These regulatory CD8+ T cells contribute to immune modulation and suppress or eliminate activated CD4 T cells.29–31 The neutrophil also plays an important role in human and mouse models of IBD.10,32,33 However, how neutrophils impact IBD is not well understood.

Wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 5 (WNT5) consists of two members, WNT5A and WNT5B, which share 90% amino acid sequence identity.34 These WNT5 proteins are involved in diverse physiological and pathological processes, including stem cell self-renewal, cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, adhesion, and polarity.35–37 Wnt5a gene knockout (KO) causes embryonic lethality with significant developmental defects in mice, whereas Wnt5b KO mice do not show strong phenotypes. While evidence indicates that WNT5A and WNT5B may have redundant roles in some developmental and physiological processes, including governing the break of left-right symmetry and neuronal specification, evidence also exists for them having distinct functions.36–40 The WNT5A protein has been linked to intestinal physiology and pathophysiology through multiple regulatory mechanisms. It is involved in crypt regeneration to re-establish homeostasis after intestinal injury41 and may promote the ability of intestinal dendritic cells (DCs) to facilitate the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into interferon-γ-producing CD4+ T helper type 1 (Th1) cells in a colitis model.42 It is not known if WNT5B plays a role in, or if WNT5A and WNT5B have a redundant role in, the regulation of intestinal biology and inflammation.

In this article, we found that double KO of WNT5A and WNT5B (WNT5 DKO) protected mice from dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. In addition, we found that the deficiency of WNT5 led to the production of neutrophils from the spleen with heightened suppressive activity toward CD8+ T cells and reduced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) upon colitis induction. Importantly, these neutrophils from the spleen were required for colitis protection of these Wnt5 DKO mice. Thus, the study revealed an unexpected role of WNT5 in the regulation of neutrophil plasticity and the importance of neutrophil plasticity in experimental colitis.

RESULTS

Wnt5 DKO mice are less susceptible to DSS-induced colitis

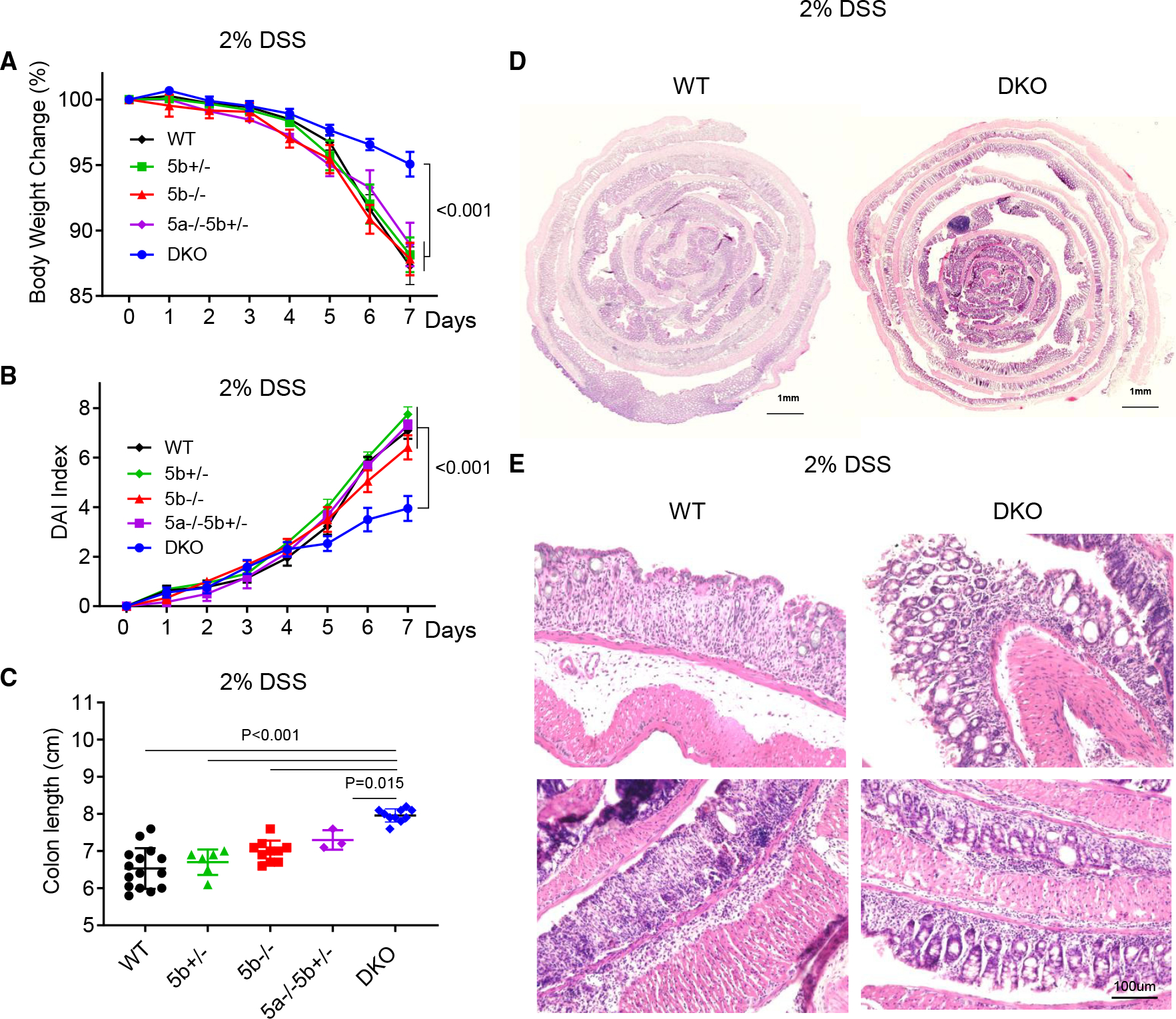

The wild-type (WT) mice, WNT5A and 5B DKO (Rosa26-CreERT2Wnt5aflox/floxWnt5b−/−, referred as Wnt5 DKO after the administration of tamoxifen) mice, and mice with various intermediate genotypes, including heterozygous WNT5B KO mice (Wnt5b+/−), WNT5B KO mice (Wnt5b−/−), WNT5A KO/WNT5B heterozygous mice (Rosa26-CreERT2Wnt5aflox/floxWnt5b+/−, referred to as Wnt5a−/−Wnt5b+/− after the administration of tamoxifen) were subjected to DSS-induced colon inflammation (Figure S1A). The DKO mice showed less weight loss than the WT control mice, whereas no significant differences were observed in weight loss among WT mice and mice with intermediate genotypes (Figure 1A). The other colitis phenotypes, including the disease activity index and colon length shortening, were also significantly milder in the Wnt5 DKO mice than those of WT mice and littermates with other intermediate genotypes, while there were no significant differences among WT mice and the mice with intermediate genotypes (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B). No difference was observed in colon length before DSS treatment (Figure S1C). Although WNT5 loss did not alter colon histological structure before DSS treatment, colon tissues in the Wnt5 DKO mice showed less damaged glands, goblet cells, mucosal architecture, and villa structures than those in the control mice after DSS treatment (Figures 1D, 1E, S1D, and S1E). These results together suggest that mice lacking both WNT5A and WNT5B are less susceptible to DSS-induced colitis. As the Wnt5 DKO mice showed much stronger resistance to colitis phenotypes than any of the intermediate genotypes, WNT5A and WNT5B are likely functionally redundant in colitis regulation.

Figure 1. Loss of WNT5 protects mice from DSS-induced colitis.

Wnt5a and Wnt5b double knockout (DKO) mice (n = 9) and various control mice (WT, n = 13; Wnt5b+/−, n = 7; Wnt5b−/−, n = 8; Wnt5b−/−Wnt5b+/−, n = 3) were treated with DSS in drinking water for 7 days. Body weight was monitored daily, and the percentage of body weight loss is shown in (A). Disease activity index was assessed daily and is shown in (B). Colons were collected and analyzed on day 7 of DSS treatment, and colon length is shown in (C). Representative sections of the Swiss rolls from the colons of WT mice and DKO mice stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) are shown in (D), and higher-magnification views of the colon are shown in (E). In (C), each datum represents one mouse. Results in (A)–(C) are presented as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed one-way ANOVA). Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates. See also Figure S1.

Wnt5 DKO mice increase myeloid cell abundance and suppress cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in DSS-treated colons

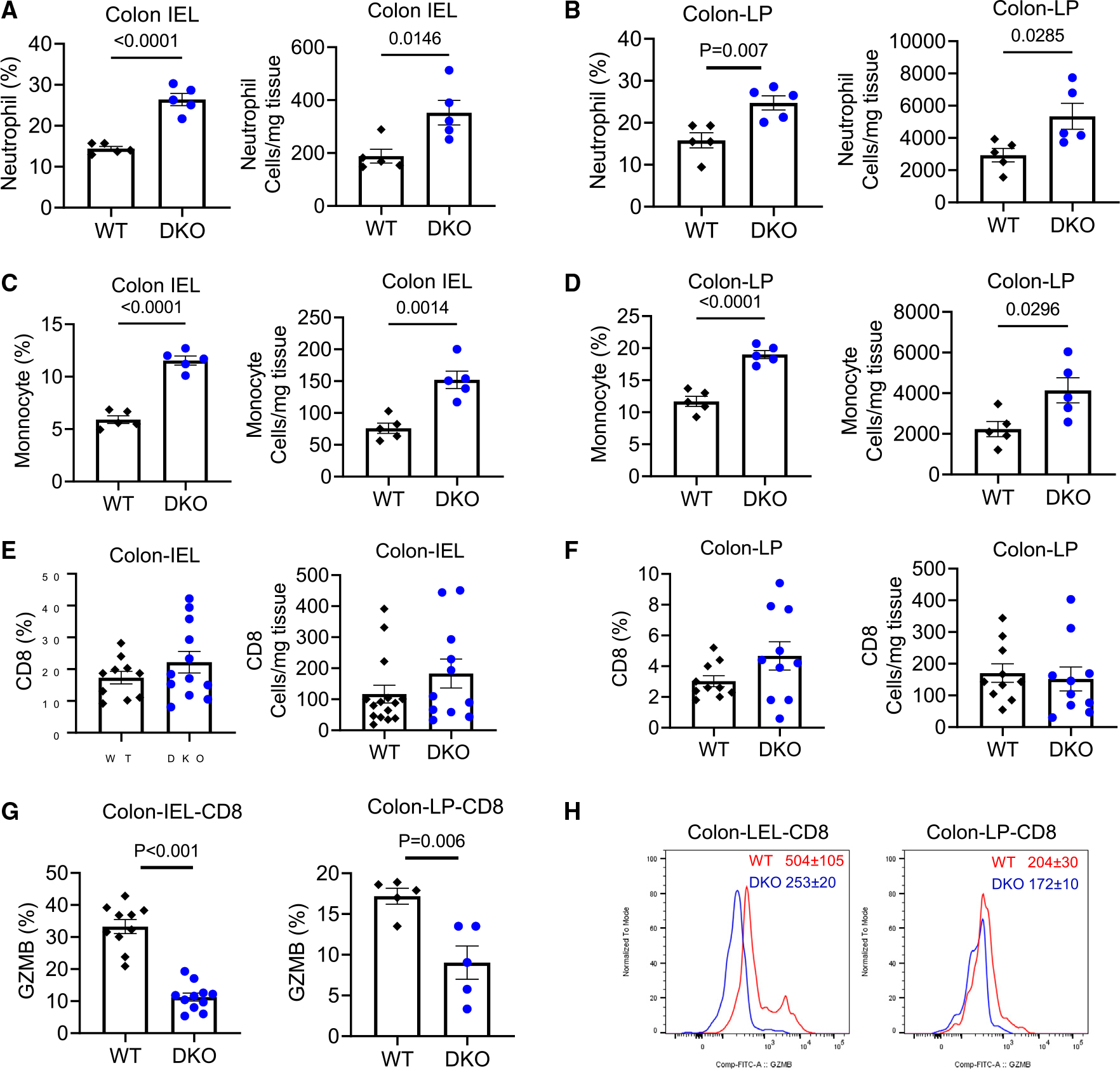

Immune cells are known to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of colitis. We therefore examined whether loss of the WNT5 protein altered immune cell composition during colitis (Figures S2A–S2C). Since WT mice and Wnt5b+/− mice showed similar colitis phenotypes, either WT or Wnt5b+/− littermates of the Wnt5 DKO mice were used as the controls. The percentages and total numbers of neutrophils and monocytes significantly increased in the colon intraepithelial layer and lamina propria of the Wnt5 DKO mice, while macrophages and DCs remained unchanged (Figures 2A–2D and S2D–S2G). The percentages and numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells, Th17 cells, and B lymphocytes were largely unaltered in the colons (Figures 2E, 2F, and S2H–S2Q). However, Wnt5 DKO mice significantly decreased GZMB expression in colonic CD8+ T cells (Figures 2G and 2H).

Figure 2. Loss of WNT5 results in myeloid cell expansion and suppression of GZMB+ CD8+ T cells in colitic colons.

The Wnt5 DKO mice and WT control mice were treated as in Figure 1. Cells were isolated from the colon intraepithelial layer (IEL) and laminae propria (LP).

(A–F) The percentages of leukocyte populations in the CD45+ population and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry.

(G and H) The percentages of GZMB+ in CD8+ T cells and mean fluorescence intensity of GZMB in CD8+ T cells together with representative flow cytometry charts are shown.

Data in (A)–(G) are presented as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed Student’s t test). Each datum point represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

See also Figure S2.

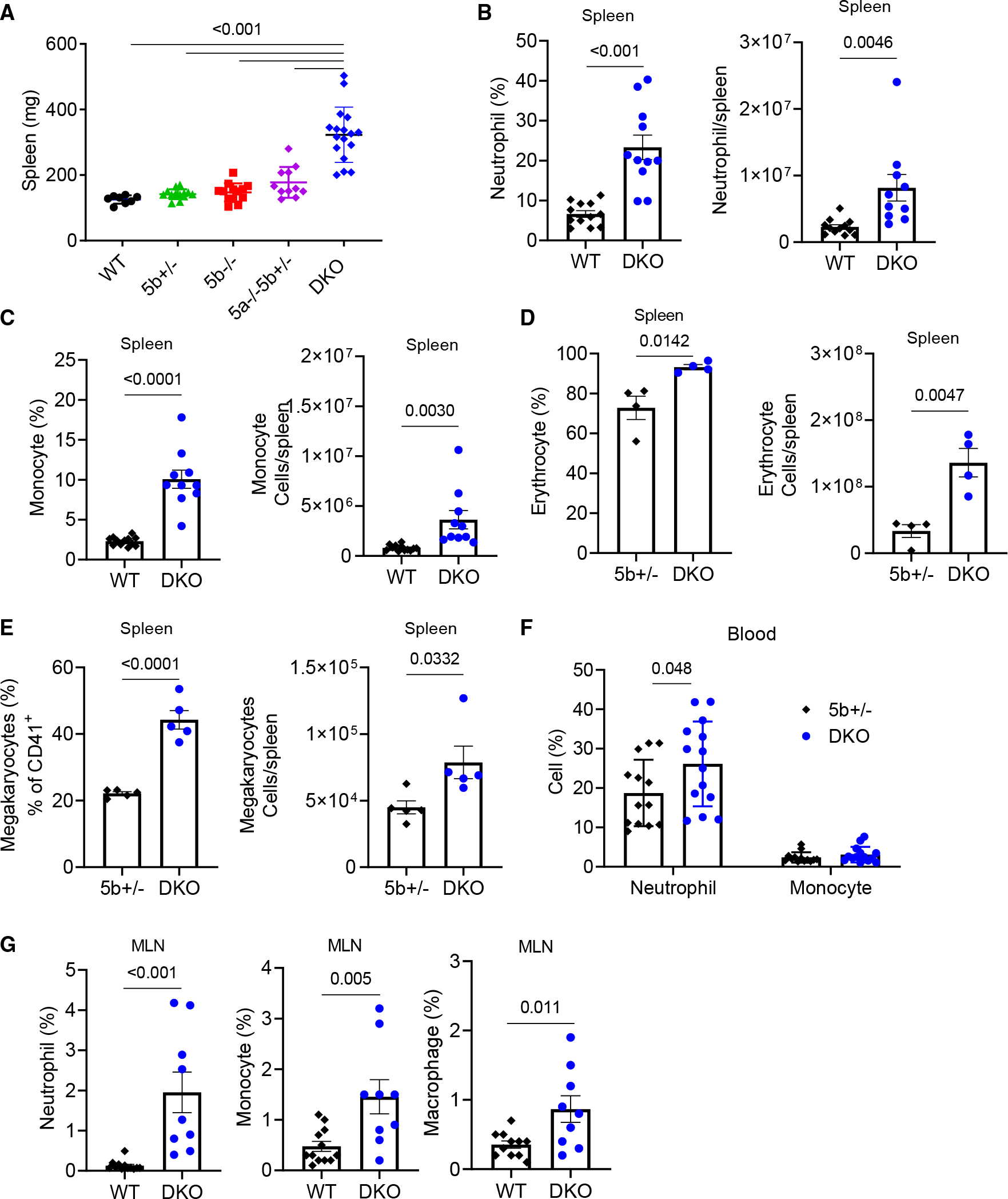

Colitic Wnt5 DKO mice develop splenomegaly

We also noticed that DSS-treated Wnt5 DKO mice had significantly enlarged spleens over the control mice (Figures 3A and S3A). Such a difference was not observed before DSS treatment (Figure S3B). The Wnt5 DKO spleens had significantly increased percentages and numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, erythrocytes, and megakaryocytes over spleens of control mice (Figures 3B–3E and S3C–S3E). Splenic macrophages showed trends of increases in the Wnt5 DKO mice in both percentage and cell number, whereas DCs, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells were largely unaltered by WNT5 deficiency (Figures S3F–S3J).

Figure 3. Colitic Wnt5 DKO mice develop splenomegaly.

Mice were treated as in Figure 1, and samples were collected on day 7 of DSS treatment.

(A) Spleen weight is shown.

(B and C) The percentages of neutrophils and monocytes in the CD45+ population and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry.

(D) The percentages of erythrocytes in the CD45− population and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry.

(E) The percentages of megakaryocytes in the CD45−CD150+CD41+ population and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry.

(F and G) The percentages of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages in the CD45+ population were determined by flow cytometry.

Data are presented as means ± SEM with p value (two-tailed one-way ANOVA for A; two-tailed Student’s t test for B–G). Each datum point represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

See also Figure S3.

The Wnt5 DKO mice also had increased percentages of neutrophils in the blood and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) (Figures 3F and 3G) but not in the bone marrow (Figure S3K). In addition, the Wnt5 DKO mice had increased percentages of monocytes and macrophages in the MLN (Figure 3G) but not in the blood or bone marrow (Figures 3F–3S3K). The percentages of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, or B cells in the blood, MLN, or bone marrow of the Wnt5 DKO mice did not show changes from those of the control mice (Figures S3L–S3N). Thus, upon DSS treatment, loss of WNT5 resulted in splenomegaly and a more pronounced expansion of myeloid cells in the spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood compared to the control mice, without obvious effects on other leukocytes.

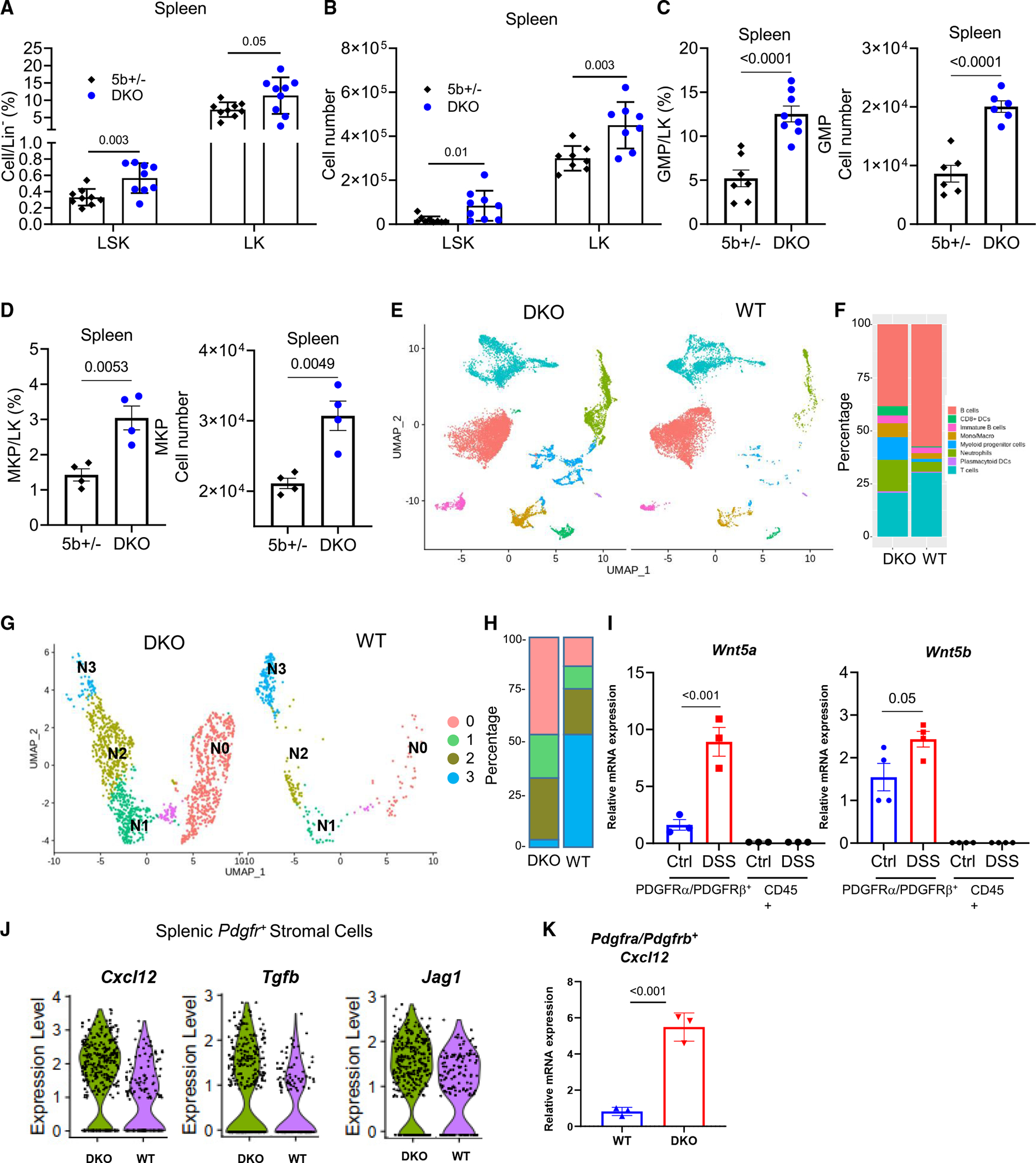

WNT5 deficiency enhances splenic EMH and myelopoiesis upon colitis induction

Splenomegaly is often the result of splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH). To investigate the hematopoiesis in the spleen, we examined hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the spleen. Indeed, the lack of WNT5 significantly increased the percentage and number of splenic stem cells (defined as Lineage−c-Kit+Sca-1+ [LSK] cells) and progenitor cells (defined as Lineage−Sca-1−c-Kit+ [LK] cells) (Figures 4A, 4B, and S4A) as well as granulocyte and monocyte progenitors (GMPs) and megakaryocytes progenitor cells (MKPs) (Figures 4C and 4D). By contrast, WNT5 deficiency reduced LSK cells, LK cells, GMPs, and MKPs in the bone marrow (Figures S4B and S4C).

Figure 4. Wnt5 DKO mice enhance splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis upon colitis induction.

(A–F) DKO mice and WT control mice were treated as Figure 1. The percentages of LK and LSK cells in Lineage− and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry (A and B). The percentages of GMPs and MKPs in LK and their absolute numbers were determined by flow cytometry (C and D).

(E) Uniform maniform approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of splenic CD45+ cells from DSS-treated Wnt5 DKO mice and WT mice.

(F) Percentages of the major cell types identified in (E).

(G) UMAP plots of the subclusters of cells expressing Ly6g+, S100a8+, and/or Cxcr2+ neutrophil markers from DSS-treated Wnt5 DKO mice and WT mice.

(H) Percentages of the subclusters identified in (G).

(I) WT mice were treated with normal water or DSS water for 7 days, and Wnt5a and Wnt5b mRNA expressions were determined by RT-qPCR in splenic CD45+ cells and CD45PDGFRα+PDGFRβ+ cells.

(J) WT mice and Wnt5 DKO mice were treated as in Figure 1. Spleen CD45− cells were collected and subjected to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Expressions of Cxcl12, Jag1, and Tgfb in the PDGFRα/PDGFRβ+ cells of WT mice and DKO mice are shown in (J).

(K) WT and Wnt5 DKO mice were treated as in Figure 1. Spleen CD45−PDGFRα+PDGFRβ+ cells were collected, and Cxcl12 mRNA expression was detected. Results in (A)–(D), (I), and (K) are shown as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed Student’s t test). Each datum point represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

We next sorted splenic CD45+ cells from DSS-treated WT mice and Wnt5 DKO mice and carried out single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Unsupervised clustering identified 16 cell clusters that belonged to 8 major cell populations based on lineage marker expression (Figures 4E, S4D, and S4E; Table S1). The percentage of myeloid cells, including neutrophils, monocytes, and their progenitor cells, markedly expanded in the DKO spleens over the WT spleens (Figure 4F). We next focused on cell clusters expressing neutrophil markers Ly6G, Cxcr2, and/or S100a8, which were partitioned into four subclusters, N0–N3 (Figure 4G). The N0–N3 subclusters represented the neutrophil differentiation trajectory based on the markers of bone marrow neutrophil development.43 The N0 subcluster expressed progenitor RNA markers (Elane, Mpo, Prtn3), cell cycle and proliferation markers (Mki67 and Cdc20), and higher ribosomal protein genes, therefore representing neutrophil progenitors. Expression of these N0 marker genes started to wane in the N1 subcluster, with further declines in the N2 and N3 subclusters. In contrast, mature neutrophil marker genes such as Cxcr2 and Ccl6 started to express in the N2 subcluster and were further elevated in the N3 subcluster (Figure S4F; Table S2). Compared to the WT spleen neutrophils, the Wnt5 DKO spleen neutrophils underwent a similar developmental trajectory but with substantially larger fractions of the continuum from N0 to N2 subpopulations and a drastically reduced N3 subpopulation (Figure 4H). These results together suggest that splenic granulopoiesis of both Wnt5 DKO and WT colitic mice closely resembles bone marrow granulopoiesis. The apparent enrichment of more immature neutrophils in the spleens of DSS-treated Wnt5 DKO mice suggests either retarded neutrophil maturation or accelerated release of mature neutrophils in these spleens compared to the control spleens.

Splenic-stromal-cell-derived WNT5 is the potential regulator of EMH in the spleen

Real-time qPCR and scRNA-seq analysis of spleen cells determined that Wnt5 expression was barely detected in CD45+ spleen cells but restricted to Pdgfrα+ and Pdgfrβ+ stromal cells, including Wt1+ fibroblast and Myh11+ smooth muscle cells (Figures 4I and S4G). DSS treatment significantly increased the Wnt5 expression in the splenic Pdgfrα+ and Pdgfrβ+ stromal cells (Figure 4I). Splenic stromal cells produce various niche factors that are important for EMH.44,45 Indeed, Wnt5 DKO mice increased the expression of Cxcl12, Tgfb1, and Jag1 in the Pdgfrα+ and Pdgfrβ+ stromal cells (Figure 4J). CXCL12 is a key niche factor for splenic EMH.46 The increase in the Cxcl12 mRNA in the spleen stromal cells of Wnt5 DKO mice was further confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 4K). Thus, splenic-stromal-cell-derived WNT5 may regulate splenic EMH via the regulation of the expression of hematopoietic niche factors including CXCL12.

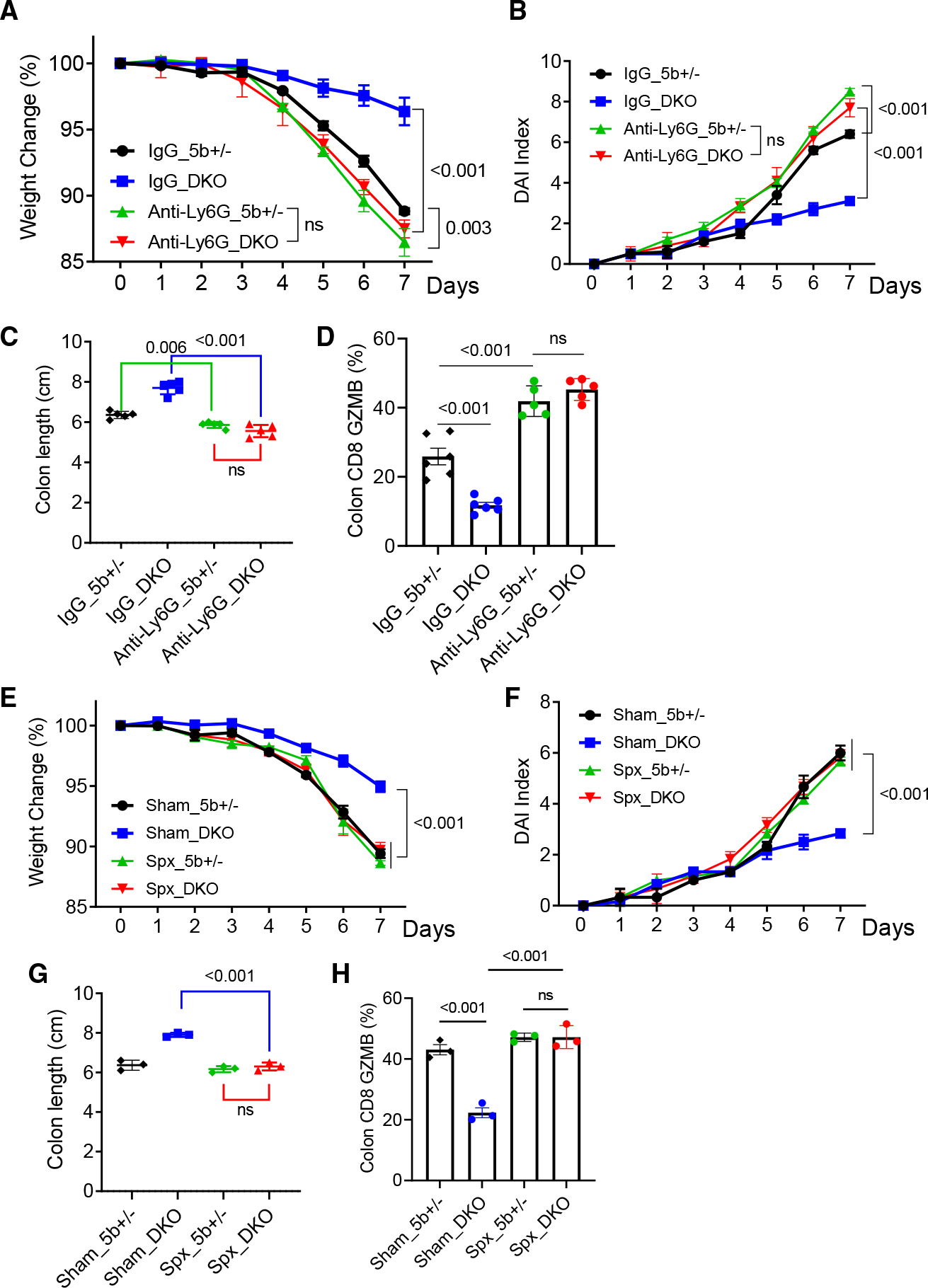

Colitis-protection phenotypes of Wnt5 DKO mice depend on splenic neutrophils

To examine if neutrophils might be responsible for the colitis-protection phenotypes, we performed neutrophil depletion using an anti-Ly6G antibody (Figure S5A), which effectively depleted neutrophils in the spleen, bone marrow, peripheral blood, and colon (Figure S5B). Depletion of neutrophils markedly exacerbated colitis phenotypes in the Wnt5 DKO mice and also significantly, but to a lesser extent, aggravated the colitis phenotypes in the control mice (Figures 5A–5C). Importantly, neutrophil depletion abrogated the differences in colitic phenotypes between the Wnt5 DKO mice and control mice (Figures 5A–5C). However, neutrophil depletion did not appear to affect enlarged spleens. This might be because neutrophil depletion did not affect the expansion of monocytes and erythroid cells in the DKO spleens (Figures S5C–S5E). While neutrophil depletion did not alter colonic CD8+ T cells and other lymphocytes (Figures S5F–S5H), it increased colonic GZMB+CD8+ T cells in both control and DKO mice, and importantly, it abrogated the differences in GMZB+CD8+ T cells between the DKO mice and control mice (Figure 5D). These data suggest that neutrophils play a moderate role in the resistance to DSS-induced colitis in the WT mice and that this role of neutrophils is greatly amplified in the absence of WNT5.

Figure 5. Colitic phenotypes of Wnt5 DKO mice depend on splenic neutrophils.

(A–D) Wnt5 DKO mice and the control mice were treated with DSS and subjected to neutrophil depletion as shown in Figure S5A (n = 5). Colitic phenotypes are shown in (A)–(C), and the percentages of GZMB+ in colon CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry (D).

(E–H) Wnt5 DKO mice and the control mice were subjected to splenectomy before being treated with DSS (n = 3). Colitic phenotypes are shown in (E)–(G). Percentages of GZMB+ in colon CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry (H).

Data are presented as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed two-way ANOVA). Each datum point in (C), (D), (G), and (H) represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

See also Figure S5.

We next tested the idea that the increase in splenic granulopoiesis is responsible for the colitis phenotypes of Wnt5 DKO mice by performing splenectomy right before DSS treatment. Splenectomy abrogated the differences in the colitis phenotypes between Wnt5 DKO mice and control mice by exacerbating colitis phenotypes in Wnt5 DKO mice (Figures 5E–5H, S5I, and S5J). Splenectomy also increased colonic CD8+ T cell GZMB expression in the Wnt5 DKO mice without significantly affecting that of control mice (Figures 5E–5H, S5I, and S5J). These data together provide strong support for the conclusion that neutrophils produced by the spleen are largely responsible for the colitis phenotypes of Wnt5 DKO mice.

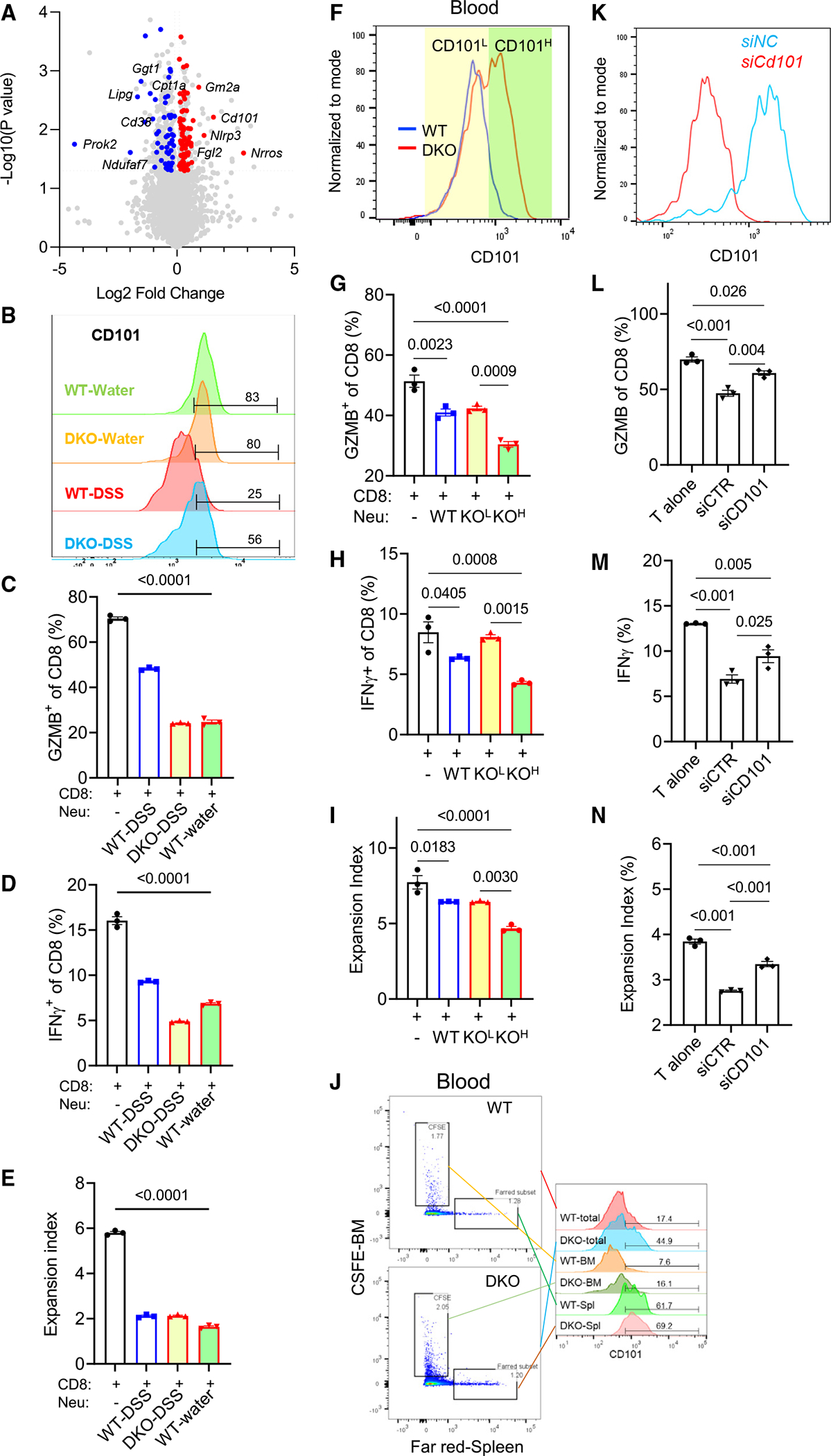

Colitic Wnt5 DKO mice produce CD101-high hyper-immunosuppressive neutrophils from the spleen

To understand how spleen-derived neutrophils in Wnt5 DKO mice control colonic inflammation, we performed scRNA-seq and proteomic analysis of Ly6G+ neutrophils from the blood of DSS-treated Wnt5 DKO mice and control mice, designated as DKO-DSS and WT-DSS, respectively. Differential gene expression (DEG) analysis of the scRNA-seq data identified 1,472 upregulated and 394 downregulated genes in circulating neutrophils when comparing DKO-DSS to the WT-DSS mice (Table S3). The proteomic analysis revealed 319 proteins significantly upregulated and 408 downregulated (Table S4). Among these proteins, 77 and 52 were also found to be upregulated and downregulated in the transcriptomic analysis, respectively (Figure 6A; Table S5). The pathway and Gene Ontology analyses indicated that the overlapping genes were significantly enriched in pathways related to neutrophil functions including the ROS metabolic process and T cell activation activities and pathways (Figures S6A–S6C; Table S6). Among the overlapping genes, the most differentially regulated one is CD101, whose expression correlates to T cell suppression and colitis.47,48

Figure 6. Colitic Wnt5 DKO mice produce CD101-high hyper-immunosuppressive neutrophils from the spleen.

DKO mice and WT control mice were treated as in Figure 1.

(A) Common upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes (log2 fold change > 0.1 or < −0.1, adjusted p value [p value adj] < 0.05) from transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of blood neutrophils from DKO mice and WT mice are denoted on the volcano plot.

(B) CD101 was detected by flow cytometry in blood neutrophils from DKO mice and WT control mice treated with water or DSS.

(C–E) CD8+ T cells were cocultured with blood neutrophils sorted from WT water, WT-DSS, and DKO-DSS mice for 72 h. GZMB, interferon γ (IFNγ), and T cell expansion were determined by flow cytometry.

(F–I) CD8+ T cells were cocultured with WT-DSS blood neutrophils and DKO-DSS CD101-low and DKO-DSS CD101-high blood neutrophils, respectively, for 72 h. GZMB, IFNγ, and T cell expansion were determined by flow cytometry. Colored shades denote fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) gating.

(J) CD101 expression was determined in blood Ly6G+CFSE+ and Ly6G+Far-Red+ cells by flow cytometry.

(K–N) Splenic neutrophils from WT-DSS mice and DKO-DSS mice were isolated by FACS and transfected with the Cd101 small interfering RNA (siRNA) for 48 h and then cocultured with CD8+ T cells for 72 h. The knockdown efficiency of Cd101 is shown in (K). GZMB, IFNγ, and T cell expansion were determined by flow cytometry.

Data in (C)–(E), (G)–(I) and (L)–(N) are presented as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed one-way ANOVA), and each datum point represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

While there was no difference in cell surface CD101 expression of blood neutrophils between WT mice and DKO mice without DSS treatment (Figure 6B), DSS treatment led to a marked suppression of CD101 expression of WT blood neutrophils (Figure 6B) compared to non-DSS treatment samples. Wnt5 DKO mice largely prevented CD101 downregulation after DSS treatment (Figure 6B). Importantly, when these blood neutrophils were isolated by cell sorting and cocultured with splenic CD8+ T cells, the suppressive activities of these blood neutrophils on CD8+ T cells largely correlated with neutrophil CD101 expression (Figures 6C–6E, S6D, and S6E). Additionally, the CD101-high neutrophils showed greater immunosuppressive activities than the CD101-low cells sorted from the same blood cells of DKO-DSS mice (Figures 6F–6I). Moreover, the CD101-low cells showed comparable immunosuppressive activities to the blood neutrophils from WT-DSS mice (Figures 6G–6I), whose CD101 expression was similar to that of CD101-low cells (Figure 6B). Therefore, the enhanced immunosuppressive activity of these CD101-high neutrophils may help to explain the strong suppression of CD8+ T cells observed in the DKO-DSS mice.

To test whether the spleen is the source of these circulating CD101-high neutrophils in the DKO-DSS mice, we performed a cell tracing experiment by injecting carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CSFE) dye into the bone marrow and the Far-Red dichloro dimethyl acridin one succinimidyl ester (DDAO-SE) dye into the spleen of WT-DSS and DKO-DSS mice, respectively (Figure S6F). Fractions of neutrophils stained either with CSFE or Far-Red were detected 2 h later in the blood, but those stained with both dyes were extremely rare (Figures 6J and S6G), suggesting that the dyes only stained cells within their tissue compartments where they were injected. Thus, CSFE+ cells in the blood were primarily released from the bone marrow, whereas Far-Red+ cells were primarily from the spleen. The blood Far-Red+ neutrophils, which were produced from spleens, showed high CD101 expression regardless of their WT or DKO origin, whereas the blood CSFE+ neutrophils showed low CD101 expression (Figure 6J). Concordantly, Far-Red-stained neutrophils in the spleen had high CD101 expression, whereas CSFE-stained neutrophils in the bone marrow had low CD101 expression (Figure S6G). Moreover, more spleen-originated neutrophils infiltrated into inflamed colon tissues of the Wnt5 DKO mice than bone-marrow-originated neutrophils (Figure S6H). Thus, these results, together with splenectomy reducing CD101 expression in the DKO-DSS blood neutrophils (Figure S6I), indicate that the CD101-high neutrophils are predominately released from the spleens and that spleen-originated neutrophils may have stronger infiltration ability than bone-marrow-originated ones into the inflamed colon.

CD101 directly contributes to CD8+ T cell suppression

We next investigated whether CD101 merely served as a marker for the subpopulation of neutrophils with heightened immunosuppressive activity or also directly contributed to T cell suppression. The Ly6G+ neutrophils sorted from the DKO-DSS spleens were transiently transfected with the SMARTpool ON-TARGETplus small interfering RNAs specific for Cd101. The knockdown of CD101 was confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure 6K). Importantly, CD101 knockdown significantly reduced the suppressive activities of the neutrophils on CD8+ T cells (Figures 6L–6N). Moreover, recombinant CD101 also strongly inhibited CD8+ T cell activation (Figure S6J). Therefore, the CD101 molecule itself directly contributes to CD8+ T cell suppression.

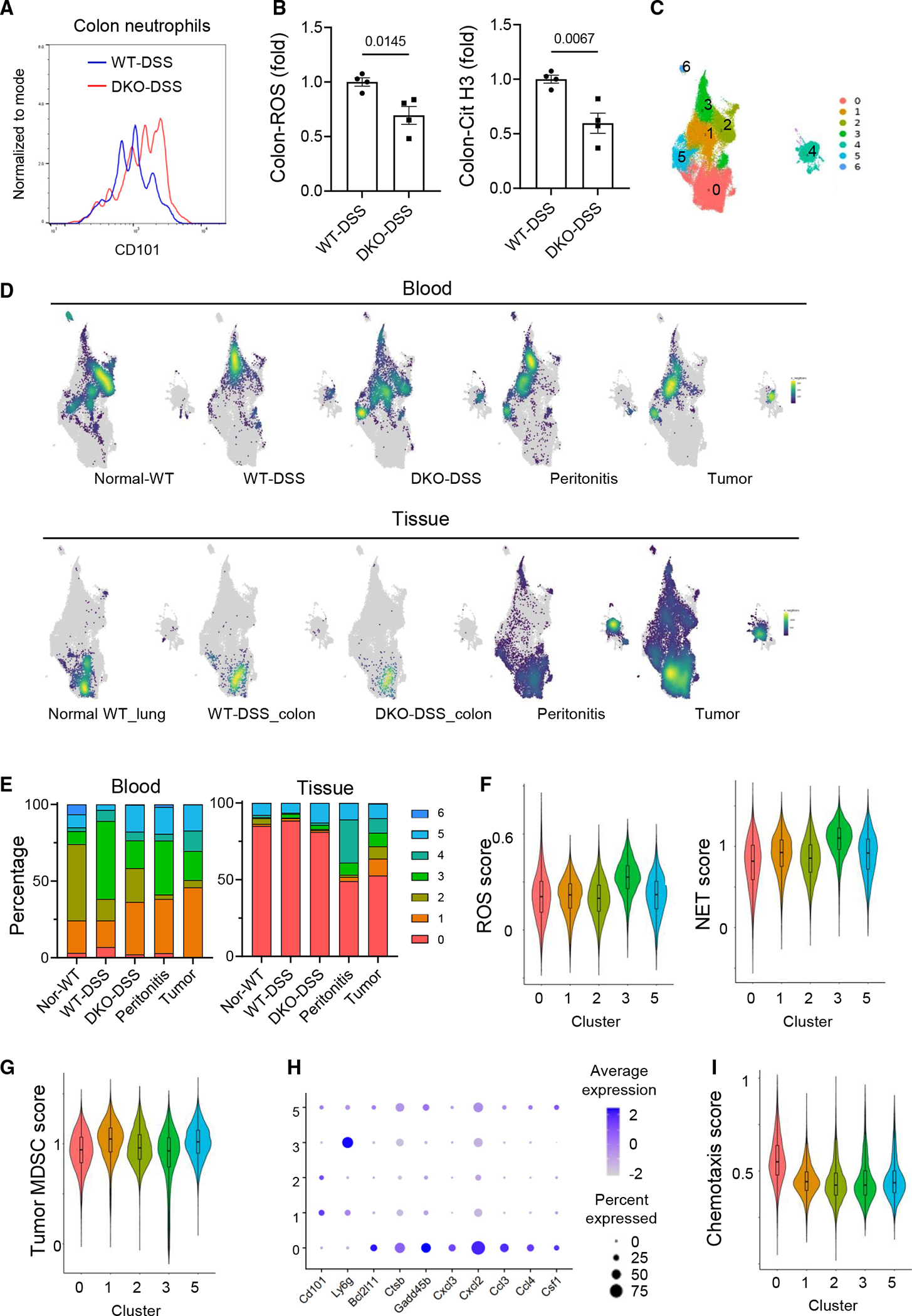

Transcriptomic profiles of blood neutrophils inform the functions of colon neutrophils

Flow cytometry analysis showed that colon-infiltrated neutrophils in DKO-DSS mice had higher levels of CD101 (Figure 7A) and lower citrullinated histone (NET formation marker) and ROS than those of WT-DSS mice (Figures 7B and S7A). However, the DEG analysis of scRNA-seq datasets of colon-infiltrated Ly6G+ neutrophils between DKO-DSS and WT-DSS mice identified only 30 upregulated and 22 downregulated genes (Table S7). Not only was the Cd101 RNA not among the DEGs, but also the pathway and Gene Ontology analyses of these DEGs did not implicate functional differences in ROS production or NET formation, whereas the analyses of DEGs of blood neutrophil did (Figures S6B and S6C; Tables S6 and S7). To understand why, we further analyzed the scRNA-seq data of colon and blood neutrophils from DKO-DSS and WT-DSS mice, together with published scRNA-seq data of neutrophils from untreated WT mice, peritonitis, and tumor-bearing mouse models.14,49–51

Figure 7. Transcriptomic profiles of blood neutrophils inform the functions of colon neutrophils.

(A) CD101 expression in the colon neutrophils of the WT-DSS mice and DKO-DSS mice was determined by flow cytometry.

(B) The ROS and citrullinated histone 3 (Cit-H3) contents in the colon neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry, and data are presented as means ± SEM with p values (two-tailed Student’s t test). Each datum point represents one mouse. Each independent experiment consists of at least three technical replicates.

(C) UMAP projection of subclusters of neutrophils aggregated from different scRNA-seq datasets.

(D) Point density-plot visualization of neutrophil distributions under different conditions. The color represents the density of overlapped neutrophils in local regions.

(E) Percentages of the subclusters under different conditions.

(F, G, and I) Violin plots of the ROS score, NET score, MDSC score, and chemotaxis score for the major subclusters.

(H) Expression of selected genes in the major subclusters.

Unsupervised clustering of these neutrophils revealed 7 major clusters (Figures 7C and S7B; Table S8). Blood neutrophils were primarily distributed in clusters 1, 2, 3, and 5 (Figures 7C–7E). The WT-DSS blood neutrophils were dominated by cluster 3 (~50%), with fewer cells in clusters 1 (17%), 2 (14%), and 5 (3%) (Figures 7C–7E). By contrast, the DKO-DSS blood neutrophils showed a substantial reduction in cluster 3 (18%) and a more balanced distribution among clusters 1 (34%), 2 (22%), 3 (18%), and 5 (17%) (Figures 7C–7E). In addition, the DKO-DSS blood neutrophils more closely resembled untreated WT ones that had a smaller fraction of cells in cluster 3 (8%) and occupied primarily clusters 2 (50%) with fewer cells also in clusters 1 (21%) and 5 (8%) (Figures 7C–7E). The gene expression profiles of the blood neutrophils from the peritonitis model and tumor-bearing mice appeared to be in between those of WT-DSS and DKO-DSS blood neutrophils (Figures 7C–7E). In contrast to blood neutrophils, tissue neutrophils were predominantly populated in cluster 0, regardless of the models or conditions (Figures 7C–7E). Consistent with a low number of DEGs between WT-DSS and DKO-DSS colon neutrophils, these colon neutrophils, largely occupying cluster 0, showed similar uniform manifold approximation and projection patterns (Figures 7C–7E). These results suggest that different mouse models or inflammation conditions are associated with more diverse gene expression profiles of circulating neutrophils than those of the tissue neutrophils.

We next compared the gene expression signature scores for ROS and NETs.14,52 WT-DSS blood neutrophils were dominant in cluster 3, which showed markedly higher scores of ROS and NETs than the other blood neutrophil clusters (1, 2, and 5), which were predominantly occupied by the DKO-DSS neutrophils (Figure 7F). Both WT-DSS and DKO-DSS colon neutrophils were populated in cluster 0 and thus have the same ROS and NET scores (Figure 7F). However, given that WT and DKO colon neutrophils showed different ROS and NET production experimentally (Figure 7B), the blood neutrophil gene expression functional scores aligned better with the experimental functional outcomes than the gene expression scores of colon neutrophils and may be better indicators of functional impacts of neutrophils.

We also compared the tumor myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) score based on previously published gene signatures.49 Concordantly, clusters 1 and 5, where the tumor blood neutrophils largely populated, showed higher MDSC scores than the other major clusters (Figure 7G). Consistent with the low immunosuppressive activity of WT-DSS blood neutrophils (Figure 6), cluster 3, where WT-DSS blood neutrophils occupied, had lower MDSC scores than clusters 1 and 5. Thus, in addition to CD101, which is important for immunosuppression in the context of colitis, some of the MDSC immunosuppressive mechanisms may also be involved in colitis. While the gene expression scores for ROS, NETs, and MDSCs (Figures 7F and 7G) and the expression levels of Cd101 and Ly6g RNA (Figure 7H) of colon neutrophils were on the low side compared to those of blood neutrophils, the chemotaxis score of the colon neutrophils is higher (Figure 7I). In addition, RNA expression of genes related to pro-apoptosis (Bcl2l11, Ctsb, and Gadd45b), neutrophil/monocyte recruitment, and macrophage function (Cxcl3, Cxcl2 Ccl3, Ccl4, and Csf1) was higher in cluster 0 than the blood neutrophil clusters (Figures 7H and S7B; full gene names of all gene symbols are listed in Table S9). These results suggest that the transcriptional activity of some neutrophil-function-related genes subsided once the neutrophils reached the colon, where the neutrophils progress into a different transcriptional state that seems to favor inflammation amplification and/or resolution. As protein content changes may lag RNA content changes, the differences in RNA expression of blood neutrophils may transit to protein content differences and subsequent functional differences in colon neutrophils. The better alignment of blood neutrophil CD101 RNA expression with CD8+ T cell suppression in the colon and the better alignment of ROS and NET scores of blood neutrophils with ROS production and NET content in colon neutrophils indicate that the RNA expression profiles of blood neutrophils are informative of the functional outcomes of colon neutrophils. Together with the observation that colon neutrophils expressed the highest CD101 among all of CD45+ leukocytes in the inflamed colons (Figure S7C), we conclude that these hyper-immunosuppressive and hypo-inflammatory characteristics of DKO-DSS neutrophils shape an anti-inflammatory environment in the inflamed colon (Figure S7D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we uncovered that WNT5A and WNT5B constituted a negative feedback mechanism for controlling splenic EMH and granulopoiesis during colitis. Their deficiency increased the production of CD101-high hyper-immunosuppressive and hypo-inflammatory neutrophils from the spleen to protect against colitic injury. These results not only support the role of spleen-derived neutrophils in providing anti-inflammatory protection against DSS-induced colitis but also suggest that, under autoimmune conditions, myeloid progenitors in the spleen and bone marrow are pre-programmed to give rise to neutrophils with different anti-inflammatory capacities.

Neutrophils are known to play complex roles in inflammation. Our present study revealed that the complex roles of neutrophils in IBD were at least in part due to their sources. In the context of gut inflammation, the spleen produces CD101-high neutrophils that are hyper-immunosuppressive and hypo-inflammatory, in contrast to those from the bone marrow, and exert more protective than tissue-damaging effects in the colon. We also revealed that WNT5 proteins were the important negative regulators of splenic granulopoiesis as well as EMH. EMH can be triggered by various conditions including chronic inflammatory conditions such as human and mouse IBD.53–57 However, little is known about how EMH is regulated or what actual roles EMH plays in various diseases. Given that WNT5 expression was upregulated by colitis, it constitutes a negative feedback mechanism for the regulation of splenic EMH, which often skews toward myelopoiesis and, hence, granulopoiesis. WNT5 likely regulates EMH via suppression of the expression of hematopoietic niche factors including CXCL12 in splenic stromal cells.

Current knowledge on the regulation of neutrophil heterogeneity and functional diversity has largely come from studies of neutrophils or MDSCs in the context of tumor immunity. Spleens were also shown as a source of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice,58,59 but neutrophils undergo further remodeling or reprogramming once they reach the tumors, leading to additional diversity.1,2,6,16–18,49,50,58,60–66 Colon-infiltrated neutrophils appeared to be less diverse in their RNA expression profiles than tumor-infiltrated neutrophils or even their precursors, the blood neutrophils (Figures 7C and 7D). ROS is a key mediator for the immunosuppressive action of MDSCs in the context of tumor immunity.60 However, the blood DKO-DSS neutrophils had lower ROS gene expression signature scores and the colon DKO-DSS neutrophils had less ROS activity than the WT-DSS counterparts. Thus, ROS may not be responsible for the increased immunosuppression of DKO-DSS neutrophils over WT-DSS ones. Instead, we demonstrated that CD101 may contribute to enhanced immunosuppression of these cells. This is consistent with the observation that the loss of CD101 expression in mouse myeloid cells is associated with exacerbated colitis.47 The inverse correlation of CD101 expression with the severity of the IBD in humans47,48 highlights the relevance of our findings to human IBD pathogenesis. Future studies are needed to further determine the contribution of neutrophil-mediated cytotoxic CD8+ T cell suppression to DKO mice colitis phenotypes relative to other mechanisms, including neutrophil ROS and NET production, as well as possible effects of DSS-DKO neutrophils on other immune cells.

Limitations of the study

While our study effectively demonstrates that the loss of WNT5 protects mice against DSS-induced colitis by enhanced splenic granulopoiesis, it is essential to acknowledge that the beneficial impact of WNT5 deficiency on colitis onset may involve additional mechanisms. This consideration arises from the fact that WNT5 is expressed not only in splenic cells but also in various other cell types within the colon. Our findings highlight the reduction in colon inflammation achieved through the generation of neutrophils from Wnt5 DKO spleens during colitis. These neutrophils exhibit the capability to suppress cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and reduced ability to produce ROS and NETs. However, due to the intricate nature of colitis pathology and the complexity of the colon microenvironment, it remains unclear which specific aspects play a more predominant role in mediating the observed protective effects and whether other immune cells also play secondary roles. In addition, this study focuses on the acute injury phase of colitis. The WNT5 proteins may have additional roles in the recovery phase of the disease.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dianqing Wu (dianqing.wu@yale.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Proteomics data have been deposited at ProteomeXchange database (ProteomeXchange: PXD048613). To review the dataset please go to https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/login and use the following login details: Username: reviewer_pxd048613@ebi.ac.uk; Password: wZ1f6cRb). The data of Single-cell RNA-seq has been submitted to the NCBI GEO: GSE255409. They are publicly available as of the date of publication.

This paper does not report the original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Animal

Wnt5aflox/flox, Wnt5b−/−, and Rosa26CreERT2 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. The Wnt5 DKO (Genotype: Rosa26-CreERT2Wnt5aflox/floxWnt5b−/−) mice were generated by crossing Rosa26-CreERT2 mice with Wnt5aflox/flox and Wnt5b−/− mice. All mice had been backcrossed into the C57Bl background prior to the intercrosses. All mice were age- (8 weeks old at the start of experiments) and sex-matched (both male and female mice were used). Littermate controls were used where appropriate. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free animal facilities at Yale University. The mice were housed under 12-h light/dark cycles with free access to food and sterile water. All experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University.

METHOD DETAILS

DSS-induced colitis

To generate the Wnt5 DKO mice, 100 mg/kg mouse body weight Tamoxifen (Sigma T-5648) dissolved in corn oil (Sigma C-8267) was delivered to mice at 8 weeks old through i.p injection. To induce colitis, 2% DSS (MP Biomedicals) was then delivered to mice in drinking water for 7 days at 13 weeks old. Body weight loss as a clinical sign of colitis was recorded daily. The disease activity index including the presence of blood in stool, stool consistency, and rectal prolapse was calculated daily as has been previously described.67 Colonic lengths were measured immediately after colons were excised.

Colon histology

H&E staining of colon tissues was performed at the Comparative Pathology Research core at Yale School of Medicine. Briefly, colons were excised, flushed with PBS, opened longitudinally, arranged in swiss rolls, and fixed in 4% buffered formalin overnight. They were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 μm), and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) according to standardized protocols. Slides were imaged using an Aperio eSlide Scanner (Leica Biosystems).

Neutrophil depletion in vivo

Depletion of Ly6G+ neutrophils was performed by i.p. injection of the anti-Ly6G mAb (1A8, BioXCell BE0075) at a dose of 500 μg in 200 μL PBS per mouse. Anti-Ly6G mAb was delivered every day starting from day −1 to day 6 of DSS treatment. Control mice received corresponding isotype mAb (BioXCell BE0089).

In vitro T cell suppression assay

CD8+ T cell preparation: Splenocytes were freshly isolated from mice. Red blood cells were lysed using Red Blood Cell lysis buffer (RBC lysis buffer, R7757, Sigma) before being magnetically sorted using the CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Catalog # 130-096-543, Miltenyi Biotec). Neutrophil preparation: Splenocytes and blood cells were freshly isolated from mice. Red blood cells were lysed using red blood cell lysis buffer (RBC lysis buffer) before being magnetically sorted using the Anti-Ly6G MicroBeads UltraPure kit (Catalog # 130-120-337, Miltenyi Biotec). T cells were distributed into CD3/CD28 (5ug/ml/1ug/ml) mAb-coated round bottom 96 well plates at 3000 cells per well. Neutrophils were seeded with T cells at a concentration of 4:1. 72 h after co-culture, T cell activation was measured by flow cytometry.

Splenectomy surgery

The surgery was performed three days before DSS treatment. The mice were under anesthesia and the abdominal cavity was opened. The spleen was carefully removed before splenic vessels were cauterized. For sham surgery, the abdomen was opened but the spleen was not removed.

Preparation of Single Cell suspension from tissues

Preparation of mouse colonic cells

Mouse colons were surgically excised, flushed with PBS, then opened longitudinally, and cut into approximately 0.5 cm-long pieces. The colon tissue was washed again with 10 mL PBS followed by incubation in 20 mL HBSS buffer containing 2% FBS, 1mM EDTA, and 1mM DTT in 50 mL canonical tube, at 37°C with constant shaking at 180 rpm for 20 min to release epithelial cells. The colon tissues were then washed with 10 mL HBSS buffer before being digested in 10 mL 1640 buffer containing 2% FBS, collagenase type II (2 mg/ml), collagenase D (0.5 mg/ml), DispaseII (3 mg/ml) and DNase I (0.1 mg/ml) at 37°C with constant shaking at 180 rpm for 30 min in a 15mL tube. After digestion, the digested cells and remaining tissue fragments were vortexed intensely for 20 s before being passed through a 40 μm cell strainer. The filtered cell suspension was centrifuged at 600g, 4°C for 5 min, then resuspended in 1 mL Facs buffer (2% FBS, 2mM EDTA in DPBS).

Preparation of mouse splenocytes, bone marrow cells, and blood cells

Splenocytes were collected by mashing the spleen by using the plunger end of the syringe in 1 mL Facs buffer. Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femur and tibia bones. Peripheral blood (600–800μL) was collected by retro-orbital bleeding into tubes (BD 365965). Cells were then filtered through a 40μm cell strainer. Cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 500g. The red blood cells were then lysed with RBC lysis buffer for 3 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, cells were washed twice with Facs buffer and resuspended in Facs buffer. For the digestion of spleen CD45− cells, the spleen capsule was cut into ~1 mm3 fragments using scissors and then digested in spleen digestion solution (200 U/ml DNase I, 250 μg/mL LiberaseDL, 1 mg/mL collagenase, type 4 (Roche) and 500 μg/mL collagenase D (Roche) in HBSS plus Ca2+ and Mg2+). After a brief vortex, the spleen fragments were allowed to sediment for ~3 min and the supernatant was transferred to another tube on ice. The sedimented (undigested) spleen fragments were subjected to a second round of digestion. The two fractions of digested cells were pooled and filtered through a 100μm nylon mesh.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were analyzed or sorted according to standard protocols using a BD FACS LSRII and BD FACS Aria III (BD Bio-sciences). Flow cytometry was performed as previously described.68 Cells in single-cell suspension were stained with live-Dead dye (ThermoFisher L34957) for 20 min on ice in the dark. Cells were then fixed with 2% PFA (Santa Cruz, sc-281692). After being washed with a flow cytometry staining buffer (eBioscience, 00-4222-26), cells were first stained with Fc block (BD) for 10 min (except for GMP staining) followed by antibodies for cell-surface markers for 1 h on ice in the dark. The cells were then washed, pelleted, and resuspended in the flow cytometry staining buffer for flow cytometry analysis. The absolute number of cells was counted by using CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Invitrogen C36950), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Data were analyzed by flowjo.

Single-cell RNA-Sequencing and analysis

Viable cells were used for sequencing following the 10× Genomics protocol. Libraries were prepared using the Single Cell 5′ Library Kit V2 (10× Genomics). Transcriptome profiles of individual cells were determined by 103 Genomics-based droplet sequencing and libraries were sequenced with paired-end reads on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina).

The sequencing reads of the single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) was mapped to mouse reference (mm10) followed by quantification of transcript expression using cellranger V7.0.0. The single-cell RNA-seq data analysis was performed using Seurat v4.0.1 R package, including cell type stratification and comparative analyses between different experimental conditions (DKO, WT).69 In the quality control (QC) analysis, poor-quality cells with <250 (likely cell fragments) or >5,000 (potentially doublets) unique expressed genes were excluded. Cells were removed if their mitochondrial gene percentages were over 10% which indicates poor cell viability. The doublets from the scRNA-seq data were evaluated by DoubletFinder and were removed in the downstream analyses.70 The data was first merged, normalized, and scaled with default settings in Seurat, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction. We retained 30 leading principal components for further visualization and cell clustering. The Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) algorithm was used to visualize cells on a two-dimensional space. Subsequently, the share nearest neighbor (SNN) graph was constructed by calculating the Jaccard index between each cell and its 20-nearest neighbors, which was then used for cell clustering based on Louvain algorithm (with a resolution of 0.3). Each cluster was screened for marker genes by differential expression analysis based on the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Based on checking the expression profile of those cluster-specific markers, we identified 8 distinct cell types (including T cells, neutrophils, Mono/Macro, myeloid progenitor cells, two types of B cells, and two types of DCs). In the downstream analysis, we focused on the neutrophil populations which consists of four subclusters. Similarly, we examined the marker profiles of each subcluster to distinguish the functional roles of different neutrophil subtypes. We then specifically identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among each sample. Top representative DEGs were visualized using heatmaps or volcano plots. For the analysis of splenic CD45+ cells, 21745 cells were included in our analysis with an average of 1561 genes per cell profiled, resulting in a total of 21373 mouse genes detected in all cells After quality-control processing.

Public data collection and integration

Two independent tumor spleen neutrophil scRNA-seq datasets: GSE139125, GSE163834, and tumor infiltration neutrophil scRNA-seq dataset: GSE213861 were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Raw sequencing reads were processed and analyzed using cellranger as mentioned above. Seurat was utilized for the down-stream analysis. Batch effect caused by the datasets were assessed and removed using harmony package in R71. DEGs among the clusters were identified using FindAllMarker function in Seurat package, where the dataset or batch was regarded as a covariate and was then adjusted. Over-representative pathways of the DEG in the clusters were evaluated by ShinyGO (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/). Pathway or gene set scores were calculated by AddModuleScore function in Seurat package.

Mass spectrometry sample preparation and data procession

The cell lysis buffer 10 M urea containing the cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, #11697498001) was used for protein extraction. A VialTweeter device (Hielscher-Ultrasound Technology)72,73 was used for sonication at 4 °C for two cycle (1 min per cycle), and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 1 h to remove the insoluble materials. To break the disulfide bridge and “cap” the cystine, the reduction and alkylation were conducted with 10 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 h at 56°C and then 20 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in dark for 45 min at room temperature. The samples were diluted by 100 mM NH4HCO3 and digested with trypsin (Promega) at ratio of 1:20 (w/w) overnight at 37°C. The digested peptides purification was performed on C18 column (MarocoSpin Columns, NEST Group INC) and 1 μg of the peptide was injected for mass spectrometry analysis.

The samples were measured by data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry method as described previously.74–76 The Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) instrument coupled to a EASY-nLC 1200 systems (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) was used. The data acquisition was performed with 150-min gradient and 300 nL/min flow rate with the temperature controlled at 60°C using a column oven (PRSO-V1, Sonation GmbH, Biberach, Germany). All the DIA-MS methods consisted of one MS1 scan and 33 MS2 scans of variable isolated windows with 1 m/z overlapping between windows. The MS1 resolution is 120,000 at m/z 200. The MS1 full scan AGC target value was set to be 2E6 and the maximum injection time was 50 ms. The MS2 resolution was set to 30,000 at m/z 200 and the normalized HCD collision energy was 28%. The MS2 AGC was set to be 1.5E6 and the maximum injection time was 50 ms. The default peptide charge state was set to 2. Both MS1 and MS2 spectra were recorded in profile mode. DIA-MS data analysis was performed using Spectronaut v1677–79 with directDIA algorithm by searching against the SwissProt downloaded mouse fasta file. The oxidation at methionine was set as variable modification, whereas carbamidomethylation at cysteine was set as fixed modification. Both peptide and protein FDR cutoffs (Qvalue) were controlled below 1% and the resulting quantitative data matrix were exported from Spectronaut. All the other settings in Spectronaut were kept as Default.

Knockdown of CD101 in neutrophils

Splenic neutrophils were sorted by the Anti-Ly-6G MicroBeads UltraPure kit (Catalog# 130-120-337, Miltenyi Biotec). Transient transfection of neutrophils was done as previously described.80 In brief, three million neutrophils were electroporated with 300 nM of SMARTpool ON-TARGETplus siRNA which combines four gene-specific siRNAs into a single reagent pool using the P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit (Lonza, Switzerland) under human monocyte nucleofection program with an Amaxa electroporation system. The cells were then cultured for 48 h in the medium supplied with the kit containing 10% FBS and 30 ng/mL recombinant G-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ).

CD101 recombinant protein suppression assay

Splenic CD8+ T cells were sorted using the CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Catalog # 130-096-543, Miltenyi Biotec). T cells were allocated to round bottom 96-well plates coated with CD3/CD28 (5ug/ml/1ug/ml) monoclonal antibodies, with recombinant CD101 protein (8.4ug/ml, R&D 3368-CD) or corresponding control protein (8.4ug/ml, R&D 4460-MG-100), at a density of 3000 cells per well. 72 h after co-culture, T cell activation was measured by flow cytometry.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were isolated from cells with the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNAs were synthesized from the RNAs with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitative PCR was done with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The primer sequences are mouse Wnt5a forward: 5′-GGAACGAATCCACGCTAAGGGT-3’; mouse Wnt5a reverse: 5′-AGCACGTCTTGAGGCTAC AGGA-3’. mouse Wnt5b forward: 5′-GCTACCGCTTTGCCAAGGAGTT-3′ mouse Wnt5b reverse: 5′-CATTTGCAGGCGACATCAGCCA-3′ mouse Actin forward: 5′-CATTGCTGACAGGATGCAGAAGG-3′ mouse Actin reverse: 5′-TGCTGGAAGGTGGACAGTGAGG-3′ mouse Cxcl12 forward: 5′-GGAGGATAGATGTGCTCTGGAAC-3′ mouse Cxcl12 reverse: 5′-AGTGAGGATGGAGACCGTGGTG-3’

Cell tracing assay

For intra-bone marrow injection, the mice were anesthetized and the hair in the region between the inguen and knee joint was removed using a razor, and a 5-mm incision was made on the thigh. The knee was then flexed to 90°, and the proximal side of the tibia was pulled anteriorly. Next, a 26-gauge needle was inserted through the patellar tendon and into the joint surface of the tibia. The needle was then carefully guided into the bone marrow cavity. To mark the cells, a microsyringe (Hamilton company) containing 40uM of the CFSE dye (Invitrogen) was used to inject 100 μL of dye into the bone marrow cavity via the bone hole. For intra-spleen injection, a left subcostal incision was made to access the peritoneal cavity and expose the spleen. Using a microsyringe (Hamilton company), 50μL of DDAO-SE Far-red dye (40uM) was injected into the spleen. Five different injection sites were carefully chosen to ensure adequate distribution of the dye throughout the spleen. The abdominal muscle and skin were then closed separately using sutures and wound clips, respectively. 2 h after dye injection, mice were sacrificed and bone marrow, blood and spleen cells were collected for flow cytometry analysis. Colon tissue was collected 8 h after dye injection. Before collecting the colon, PE-CD45 antibody was injected through iv 3 min before transcardial perfusion. For flow cytometry analysis of colon infiltrated dye-labeling neutrophils, PE-CD45 positive cells were excluded to eliminate the contamination of circulating cells.81

ROS and NET detection in colon neutrophils

ROS and NET were measured by flow cytometry. Colonic single-cell suspensions were obtained from WT mice and DKO mice after DSS treatment. To detect ROS, cells were stained with H2DCFDA ROS dye (Invitrogen) in PBS at 37°C for 15 min, along with a neutrophil marker. For NET detection, cells were first labeled with neutrophil marker dye, then permeabilized using methanol, followed by staining with Cit-Histone3 (abcam ab5103) antibody for 2 h at 4°C, and subsequently stained with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Comparisons of means between two groups and multiple groups were tested by unpaired, two-tailed t test and Two-way ANOVA-test using Prism 9.2.0 software (GraphPad). Statistical tests used biological replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 were all considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Anti-mouse Ly6C | BioLegend | Cat#128008; RRID:AB_1186132 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G | BioLegend | Cat#127612; RRID:AB_2251161 |

| Anti-mouse B220 | BioLegend | Cat#103208; RRID:AB_312993 |

| Anti-mouse MHCII | Thermo Scientific | Cat#48-5321-80; RRID:AB_1272241 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c | BioLegend | Cat#117307; RRID:AB_313776 |

| Anti-mouse CD64 | BioLegend | Cat#139315; RRID:AB_2566555 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b | BioLegend | Cat#101207; RRID:AB_312791 |

| Anti-mouse CD45 | BD Biosciences | Cat#564279; RRID:AB_2651134 |

| Anti-mouse TCR alpha/beta | Biolegend | Cat#109211; RRID:AB_313434 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a | BD Biosciences | Cat#563786; RRID:AB_2732919 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 | BioLegend | Cat#100534; RRID:AB_493374 |

| Anti-mouse TCR gamma/delta | ThermoFisher | Cat#12-5711-81; RRID:AB_465933 |

| Anti-mouse Granzyme B | Biolegend | Cat#515403; RRID:AB_2114575 |

| Anti-mouse IFNgamma | ThermoFisher | Cat#12-7311-82; RRID:AB_466193 |

| Anti-mouse Foxp3 | ThermoFisher | Cat#11-5773-82; RRID:AB_465243 |

| Anti-mouse IL17 | BioLegend | Cat#506916; RRID:AB_536017 |

| Anti-mouse Lineage cocktail | BioLegend | Cat#133310; RRID:AB_11150779 |

| Anti-mouse CD117 | BioLegend | Cat#105815; RRID:AB_493472 |

| Anti-mouse Sca-1 | BioLegend | Cat#108107; RRID:AB_313345 |

| Anti-mouse CD16/32 | BioLegend | Cat#101317; RRID:AB_2104156 |

| Anti-mouse CD34 | Thermo Scientific | Cat#50-0341-80; RRID:AB_10609352 |

| Anti-mouse CD150 | BioLegend | Cat#115903; RRID:AB_313682 |

| Anti-mouse CD41 | BioLegend | Cat#133903; RRID:AB_2129746 |

| Anti-Ly6G mAB depletion antibody | Bio X Cell | Cat##BE0075-1; RRID:AB_1107721 |

| InVivoMAb rat IgG2a isotype control | Bio X Cell | Cat#BE0089; RRID:AB_1107769 |

| Ultra-LEAF™ Purified anti-mouse CD28 Antibody | Biolegend | Cat#102116; RRID:AB_2810333 |

| Cit-Histone3 antibody | Abcam | Cat#Ab5103; RRID:AB_304752 |

| Ultra-LEAF™ Purified anti-mouse CD3e Antibody | Biolegend | Cat#100340; RRID:AB_2616674 |

| Anti-mouse F4/80 | Thermo Scientific | Cat#17-4801-82; RRID:AB_2784648 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| DSS | MP Biomedicals | Cat#0216011080 |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T5648 |

| Recombinant G-CSF | PeproTech | Cat#250-05 |

| Recombinant Mouse IGSF2/CD101 Fc Chimera Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat#3368-CD-050 |

| Recombinant Mouse IgG2A Fc Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat#4460-MG-100 |

|

| ||

| Critical commercial assays | ||

|

| ||

| Corn oil | Sigma-Aldrich | Ca#C8267 |

| Red blood cell lysis buffer | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#R7757 |

| CD8+ T cell isolation kit | Miltenyi Biotech | Cat#130-096-543 |

| Anti-Ly6G MicroBeads UltraPure | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-120-337 |

| DPBS without Calcium and Magnesium | Fisher Scientific | Cat#14-190-250 |

| 1X HBSS no Ca Mg phenol red | Thermo Fisher | Cat#14175-103 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum, Qualified, Heat Inactivated | Thermo Scientific | Cat#10438026 |

| Gibco™ RPMI 1640 Medium | Fisher Scientific | Cat#11-875-119 |

| Collagenase type II | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#17-101-015 |

| Collagenase D | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#11088866001 |

| EDTA, 0.5M SOLUTION, PH 8.0 | AmericanBio | Cat#AB00502-01000 |

| DTT | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#646563 |

| Dispase II | Sigma-Aldrich | Ca#04942078001 |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#11284932001 |

| Live-Dead dye | Thermo Scientific | Cat#L34957 |

| Flow cytometry staining buffer | eBioscience | Cat#00-4222-26 |

| Purified Rat Anti-Mouse CD16/CD32 Fc block | BD Bioscience | Cat#553142 |

| CountBright™ Absolute Counting Beads | ThermoFisher | Cat#C36950 |

| SMARTpool: ON-TARGETplus Mouse CD101 siRNA | Horizon Discovery Biosciences | Cat#L-076576-01-0005 |

| P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector® X Kit | Lonza | Ca#V4XP-3024 |

| RNeasy Plus mini kit | Qiagen | Cat#74134 |

| iScript cDNA synthesis kit | Bio-rad | Cat#1708891 |

| iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix | Bio-rad | Cat#1725121 |

| CFSE dye | ThermoFisher | Cat#C34554 |

| DDAO-SE Far-red dye | ThermoFisher | Cat#C34564 |

| H2DCFDA ROS dye | ThermoFisher | Cat#D399 |

| Liberase™ DL | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#05401160001 |

| 4% buffered formalin | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-281692 |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| Single cell RNA seq | This manuscript | ProteomeXchange: PXD048613 |

| MS analysis | This manuscript | GEO: GSE255409 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

|

| ||

| Mouse: Wnt5aflox/flox | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain #:026626 |

| Mouse: Wnt5b−/− | International Mouse Strain Resource | Komp #:14908 |

| Mouse: Rosa26-CreER(T2) mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain #:008463 |

|

| ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

| ||

| Primers for PCR and RT-qPCR | Integrated DNA Technologies | listed in the STAR Methods |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| GraphPad Prism 9.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| ImageJ | National Institutes of Health | https://imagej.net/ij/ |

| FlowJo | FlowJo, LLC | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

Highlights.

Loss of WNT5 protects mice from colitis by promoting splenic granulopoiesis

WNT5 proteins constitute negative feedback control of splenic granulopoiesis during colitis

Splenic granulopoiesis produces hyper-immunosuppressive and hypo-pro-inflammatory neutrophils

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants (R01HL145152 to W.T. and 5R35HL135805 to D.W.). We thank Andres Hidalgo for valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.113934.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ng LG, Ostuni R, and Hidalgo A (2019). Heterogeneity of neutrophils.Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 255–265. 10.1038/s41577-019-0141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolás-Ávila JÁ, Adrover JM, and Hidalgo A (2017). Neutrophils in Homeostasis, Immunity, and Cancer. Immunity 46, 15–28. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolaczkowska E, and Kubes P (2013). Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 159–175. 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, and Jaillon S (2011). Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 519–531. 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan C (2006). Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 173–182. 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burn GL, Foti A, Marsman G, Patel DF, and Zychlinsky A (2021). The Neutrophil. Immunity 54, 1377–1391. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soehnlein O, Steffens S, Hidalgo A, and Weber C (2017). Neutrophilsas protagonists and targets in chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 248–261. 10.1038/nri.2017.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ley K, Hoffman HM, Kubes P, Cassatella MA, Zychlinsky A, Hedrick CC, and Catz SD (2018). Neutrophils: New insights and open questions. Sci. Immunol. 3, eaat4579. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat4579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauseef WM, and Borregaard N (2014). Neutrophils at work. Nat. Immunol. 15, 602–611. 10.1038/ni.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wera O, Lancellotti P, and Oury C (2016). The Dual Role of Neutrophilsin Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 5. 10.3390/jcm5120118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier BM, and Parkos CA (2012). The role of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 5, 354–366. 10.1038/mi.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quail DF, Amulic B, Aziz M, Barnes BJ, Eruslanov E, Fridlender ZG, Goodridge HS, Granot Z, Hidalgo A, Huttenlocher A, et al. (2022). Neutrophil phenotypes and functions in cancer: A consensus statement. J. Exp. Med. 219, e20220011. 10.1084/jem.20220011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedrick CC, and Malanchi I (2022). Neutrophils in cancer: heterogeneous and multifaceted. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 173–187. 10.1038/s41577-021-00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie X, Shi Q, Wu P, Zhang X, Kambara H, Su J, Yu H, Park SY,Guo R, Ren Q, et al. (2020). Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1119–1133. 10.1038/s41590-020-0736-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoyratty TE, Ai Z, Ballesteros I, Eames HL, Mathie S, Martín-Salamanca S, Wang L, Hemmings A, Willemsen N, von Werz V, et al. (2021). Distinct transcription factor networks control neutrophil-driven inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 22, 1093–1106. 10.1038/s41590-021-00968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ager A (2023). Cancer immunotherapy: T cells and neutrophils working together to attack cancers. Cell 186, 1304–1306. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschhorn D, Budhu S, Kraehenbuehl L, Gigoux M, Schröder D, Chow A, Ricca JM, Gasmi B, De Henau O, Mangarin LMB, et al. (2023). T cell immunotherapies engage neutrophils to eliminate tumor antigen escape variants. Cell 186, 1432–1447.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gungabeesoon J, Gort-Freitas NA, Kiss M, Bolli E, Messemaker M, Siwicki M, Hicham M, Bill R, Koch P, Cianciaruso C, et al. (2023). A neutrophil response linked to tumor control in immunotherapy. Cell 186, 1448–1464.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang JT (2020). Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2652–2664. 10.1056/NEJMra2002697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham DB, and Xavier RJ (2020). Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 578, 527–539. 10.1038/s41586-020-2025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adolph TE, Meyer M, Schwärzler J, Mayr L, Grabherr F, and Tilg H (2022). The metabolic nature of inflammatory bowel diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 753–767. 10.1038/s41575-022-00658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casalegno Garduño R, and Däbritz J (2021). New Insights on CD8(+) T Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Immunol. 12, 738762. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.738762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corridoni D, Antanaviciute A, Gupta T, Fawkner-Corbett D, Aulicino A, Jagielowicz M, Parikh K, Repapi E, Taylor S, Ishikawa D, et al. (2020). Single-cell atlas of colonic CD8(+) T cells in ulcerative colitis. Nat. Med. 26, 1480–1490. 10.1038/s41591-020-1003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nancey S, Holvöet S, Graber I, Joubert G, Philippe D, Martin S, Nicolas JF, Desreumaux P, Flourié B, and Kaiserlian D (2006). CD8+ cytotoxic T cells induce relapsing colitis in normal mice. Gastroenterology 131, 485–496. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JC, Lyons PA, McKinney EF, Sowerby JM, Carr EJ, Bredin F, Rickman HM, Ratlamwala H, Hatton A, Rayner TF, et al. (2011). Gene expression profiling of CD8+ T cells predicts prognosis in patients with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4170–4179. 10.1172/JCI59255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boschetti G, Nancey S, Moussata D, Cotte E, Francois Y, Flourié B, and Kaiserlian D (2016). Enrichment of Circulating and Mucosal Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cells Is Associated with Postoperative Endoscopic Recurrence in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 10, 338–345. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins D, Seth R, Kummer JA, Scott BB, Hawkey CJ, and Robins RA (2000). Differential levels of granzyme B, regulatory cytokines, and apoptosis in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis at first presentation. J. Pathol. 190, 184–189. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kappeler A, and Mueller C (2000). The role of activated cytotoxic T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Histol. Histopathol. 15, 167–172. 10.14670/HH-15.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Zaslavsky M, Su Y, Guo J, Sikora MJ, van Unen V, Christophersen A, Chiou SH, Chen L, Li J, et al. (2022). KIR(+)CD8(+) T cells suppress pathogenic T cells and are active in autoimmune diseases and COVID-19. Science 376, eabi9591. 10.1126/science.abi9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishra S, Srinivasan S, Ma C, and Zhang N (2021). CD8(+) Regulatory T Cell - A Mystery to Be Revealed. Front. Immunol. 12, 708874. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.708874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koh CH, Lee S, Kwak M, Kim BS, and Chung Y (2023). CD8 T-cell subsets: heterogeneity, functions, and therapeutic potential. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 2287–2299. 10.1038/s12276-023-01105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arosa L, Camba-Gómez M, and Conde-Aranda J (2022). Neutrophils in Intestinal Inflammation: What We Know and What We Could Expect for the Near Future. Gastrointestinal Disorders 4, 263–276. 10.3390/gidisord4040025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drury B, Hardisty G, Gray RD, and Ho GT (2021). Neutrophil Extra-cellular Traps in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Translation. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 321–333. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavin BJ, McMahon JA, and McMahon AP (1990). Expression of multiple novel Wnt-1/int-1-related genes during fetal and adult mouse development. Genes Dev. 4, 2319–2332. 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastelaro de Rezende M, Zenker Justo G, Julian Paredes-Gamero E, and Gosens R (2020). Wnt-5A/B Signaling in Hematopoiesis throughout Life. Cells 9, 1801. 10.3390/cells9081801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers S, and Scholpp S (2022). Vertebrate Wnt5a - At the crossroads of cellular signalling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 125, 3–10. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suthon S, Perkins RS, Bryja V, Miranda-Carboni GA, and Krum SA (2021). WNT5B in Physiology and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 667581. 10.3389/fcell.2021.667581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agalliu D, Takada S, Agalliu I, McMahon AP, and Jessell TM (2009). Motor neurons with axial muscle projections specified by Wnt4/5 signaling. Neuron 61, 708–720. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minegishi K, Hashimoto M, Ajima R, Takaoka K, Shinohara K, Ikawa Y, Nishimura H, McMahon AP, Willert K, Okada Y, et al. (2017). A Wnt5 Activity Asymmetry and Intercellular Signaling via PCP Proteins Polarize Node Cells for Left-Right Symmetry Breaking. Dev. Cell 40, 439–452.e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessenbrock K, Smith P, Steenbeek SC, Pervolarakis N, Kumar R, Minami Y, Goga A, Hinck L, and Werb Z (2017). Diverse regulation of mammary epithelial growth and branching morphogenesis through non-canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 3121–3126. 10.1073/pnas.1701464114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyoshi H, Ajima R, Luo CT, Yamaguchi TP, and Stappenbeck TS (2012). Wnt5a potentiates TGF-beta signaling to promote colonic crypt regeneration after tissue injury. Science 338, 108–113. 10.1126/science.1223821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato A, Kayama H, Shojima K, Matsumoto S, Koyama H, Minami Y, Nojima S, Morii E, Honda H, Takeda K, and Kikuchi A (2015). The Wnt5a-Ror2 axis promotes the signaling circuit between interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma in colitis. Sci. Rep. 5, 10536. 10.1038/srep10536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evrard M, Kwok IWH, Chong SZ, Teng KWW, Becht E, Chen J, Sieow JL, Penny HL, Ching GC, Devi S, et al. (2018). Developmental Analysis of Bone Marrow Neutrophils Reveals Populations Specialized in Expansion, Trafficking, and Effector Functions. Immunity 48, 364–379.e8. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crane GM, Jeffery E, and Morrison SJ (2017). Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 573–590. 10.1038/nri.2017.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comazzetto S, Shen B, and Morrison SJ (2021). Niches that regulate stem cells and hematopoiesis in adult bone marrow. Dev. Cell 56, 1848–1860. 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, and Nagasawa T (2006). Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 25, 977–988. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wrage M, Kaltwasser J, Menge S, and Mattner J (2021). CD101 as an indicator molecule for pathological changes at the interface of host-microbiota interactions. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 311, 151497. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2021.151497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schey R, Dornhoff H, Baier JLC, Purtak M, Opoka R, Koller AK, Atreya R, Rau TT, Daniel C, Amann K, et al. (2016). CD101 inhibits the expansion of colitogenic T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 1205–1217. 10.1038/mi.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alshetaiwi H, Pervolarakis N, McIntyre LL, Ma D, Nguyen Q, Rath JA, Nee K, Hernandez G, Evans K, Torosian L, et al. (2020). Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaay6017. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veglia F, Hashimoto A, Dweep H, Sanseviero E, De Leo A, Tcyganov E, Kossenkov A, Mulligan C, Nam B, Masters G, et al. (2021). Analysis of classical neutrophils and polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients and tumor-bearing mice. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201803. 10.1084/jem.20201803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim R, Hashimoto A, Markosyan N, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Kar G, Fu S, Sehgal M, Garcia-Gerique L, Kossenkov A, et al. (2022). Ferroptosis of tumour neutrophils causes immune suppression in cancer. Nature 612, 338–346. 10.1038/s41586-022-05443-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gullotta GS, De Feo D, Friebel E, Semerano A, Scotti GM, Bergamaschi A, Butti E, Brambilla E, Genchi A, Capotondo A, et al. (2023). Age-induced alterations of granulopoiesis generate atypical neutrophils that aggravate stroke pathology. Nat. Immunol. 24, 925–940. 10.1038/s41590-023-01505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caiado F, Pietras EM, and Manz MG (2021). Inflammation as a regulator of hematopoietic stem cell function in disease, aging, and clonal selection. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201541. 10.1084/jem.20201541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernández-García V, Gonzá lez-Ramos S., Martín-Sanz P., Castrillo A., and Boscá L. (2020). Contribution of Extramedullary Hematopoiesis to Atherosclerosis. The Spleen as a Neglected Hub of Inflammatory Cells. Front. Immunol. 11, 586527. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.586527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawashima K, Onizawa M, Fujiwara T, Gunji N, Imamura H, Katakura K, and Ohira H (2022). Evaluation of the relationship between the spleen volume and the disease activity in ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. Medicine (Baltim.) 101, e28515. 10.1097/MD.0000000000028515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim CH (2010). Homeostatic and pathogenic extramedullary hematopoiesis. J. Blood Med. 1, 13–19. 10.2147/JBM.S7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, and Vijay-Kumar M (2014). Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 104, 15.25.1–15.25.14. 10.1002/0471142735.im1525s104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C, Ning H, Liu M, Lin J, Luo S, Zhu W, Xu J, Wu WC, Liang J, Shao CK, et al. (2018). Spleen mediates a distinct hematopoietic progenitor response supporting tumor-promoting myelopoiesis. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3425–3438. 10.1172/JCI97973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, Rauch PJ, Chudnovskiy A, Berger C, Ryan RJH, Iwamoto Y, Marinelli B, Gorbatov R, et al. (2012). Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2491–2496. 10.1073/pnas.1113744109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veglia F, Sanseviero E, and Gabrilovich DI (2021). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 485–498. 10.1038/s41577-020-00490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Veglia F, Perego M, and Gabrilovich D (2018). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 19, 108–119. 10.1038/s41590-017-0022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]