Abstract Page

Background

Primary Sjogren's syndrome (pSS) is an autoimmune exocrinopathy in which extraglandular signs of pSS are determinant for the prognosis. Involvement of both peripheral and central nervous system (CNS) are known to be among the sites of high systemic activity in pSS.

Case presentation

We, herein, report a case of a 57-year-old female patient with pSS presenting with typical Guillan-Barré syndrome (GBS), shortly followed by acute headaches accompanied by cortical blindness. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated T2 signal abnormalities on the occipital region with narrowing and irregularities of the cerebral arteries, suggestive of CNS vasculitis.

Subtle sicca symptoms occurring prior to neurological symptoms by 8 months together with immunological disturbances (anti-SSA, anti-SSB antibodies positivity, type II cryoglobulins positivity, and C4 hypocomplementemia) allowed us to retain the diagnosis of pSS. Recovery of motor symptoms was possible under the combined use of immunoglobulins and corticotherapy during the initial phase. A three-years follow-up confirmed progressive motor recovery and stabilization under 6-months cyclophosphamide cycles relayed by azathioprine therapy.

Conclusions

Neurological complications can be inaugural in lead to urgent investigations and treatment. Peripheral and central neurological manifestations can coexist. The approach should integrate careful clinical assessment, as well as radiological and immunological findings.

Keywords: Primary Sjogren syndrome, Guillan-Barré syndrome, Central nervous system, Vasculitis

1. Background

Sjogren's Syndrome is an autoimmune exocrinopathy. This syndrome can be primary (primary Sjogren's syndrome (pSS)) or secondary if associated with other connective tissue diseases. Systemic signs during pSS may inaugurate the disease or they may appear after sicca symptomatology. It can be involved all systems, and it is estimated that up to 75 % of patients exhibit extraglandular signs of variable severity [1].

Severe extraglandular manifestations of pSS are known to vary between 10 and 20 % and they habitually occur late in the disease course [2]. They are an important determinant for prognosis in pSS patients [3].

Involvement of peripheral nervous system (PNS) in pSS is well-established, and axonal sensoriomotor polyneuropathies are the most described manifestations [4]. However, the type and prevalence of central nervous system (CNS) manifestations of pSS are still controversial [5,6] including CNS vasculitis [6]. The pathogenesis and the characteristics of CNS involvement in pSS are varied and poorly-understood [7]. Both peripheral and CNS involvements have been reported among the sites of high systemic activity [8] with severe and life-threatening forms of the disease.

We, herein, report the case of a female patient presenting with typical Guillan-Barré syndrome (GBS), rapidly followed by bilateral cortical blindness related to CNS vasculitis. Careful anamnesis revealed that systemic symptoms shortly preceded neurological features.

2. Case description

A 57-year-old female patient with no significant past medical history, presented complaining of ascending weakness of four limbs, followed by speech and swallowing disorders for 15 days before admission. On examination, facial diplegia, impaired swallowing reflexes, and paralytic dysarthria were noted. Motor examination revealed symmetric flaccid quadriplegia with diffuse areflexia. The patient was apyretic and eupneic. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed hyperproteinorachia (0.67 g/l), normal glycorachia (2.8 mmol/l) and normal cytological findings (2 cells/mm3). A Nerve conduction study showed slowing of conduction velocity, and prolonged distal and F-wave latencies on the median and peroneal nerves bilaterally. Diagnosis of the acute inflammatory demyelinating form of GBS was retained. The patient was first treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (0.4 g/Kg weight) for 5 days. No improvement of the neurological symptoms was noted.

Twenty days after the onset of symptom, the patient developed sudden simultaneous headaches and bilateral blindness. On ophthalmic examination, visual acuity was limited to the perception of light bilaterally. The patient's pupil responses were normal with no afferent defect, which is, consistent with a cortical origin of symptoms. Careful anamnesis revealed that the patient exhibited mouth dryness and arthralgia of the large joints eight months before the current episode which was neglected by the patient. The idiopathic origin of GBS was therefore reconsidered.

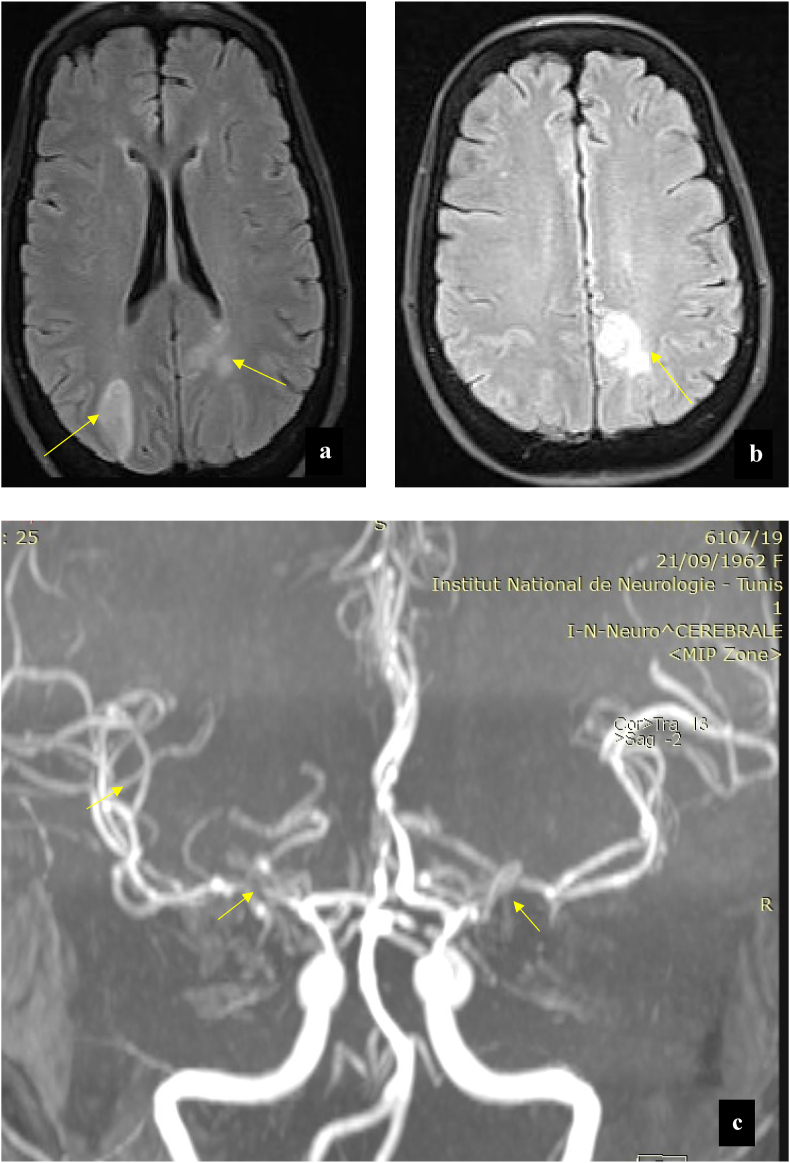

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated bilateral T2-weighted hyperintense signal lesions located in the cortical and subcortical regions of the temporal and occipital lobes (Fig. 1a,b). Sequence for MR angiography revealed segmental narrowing and irregularities of the cerebral arteries, suggestive highly CNS vasculitis (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

(a) Initial magnetic resonance (MRI) of the brain. The initial MRI scan showed hyperintenses white matter lesions involving right occipital regions and left subcortical occipital, periventricular regions in the axial T2 Flair ponderation (Arrows). (b) The initial MRI scan of the brain, axial T2 Flair ponderation showed hyperintense lesion involving the left parietal lobe (Arrow). (c) The initial Angio-MRI 3D-TOF (time-of-flight) showed the narrowing of the M 1 and M 3 segments of the right middle cerebral artery and M 1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (Arrows).

Biological investigations demonstrated lymphopenia (count: 0.9 × 109/l). The C-reactive protein level was 15 mg/l. Albuminemia was in normal range (40.52 g/l). The anti-nuclear antibody titer was 1/1600 and antibodies against DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) were absent. The extractable nuclear panel was strongly positive for anti-SSA antibodies (RO-52, 60) and anti-SSB (La). Screening for antiβ2 glycoprotein and anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG,IgM) was negative. Hypocomplementemia (of C4) was detected. Type II cryoglobulins were identified. The biopsy of the minor salivary glands (performed after initiating corticotherapy) did not reveal abnormalities. The Salivary gland scintigraphy revealed decreased function of the right parotid gland and the bilateral submandibular glands. Schirmer's test was positive (<5 mm [3] min in the two eyes). Based on the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for pSS [9].

Both GBS and CNS vasculitis (with both cerebral parenchymal and large-vessel involvement) were considered to be secondary to pSS. pSS disease activity was assessed on the basis of the EULAR Sjögren's Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI). The patient activity score was 12 (with high CNS domain score of 3).

Plasma exchange was initiated forty-five days after the first symptom. However, the patient presented breathing difficulties, forcing us to stop this treatment. Intravenous methylprednisolone (1 gr/day for 5 days) followed by oral corticosteroids (1 mg/kg/day) were therefore initiated. A gradual improvement in muscle strength and swallowing difficulties was noted. A check-up brain MRI, performed 22 days after the onset of corticotherapy, demonstrated repermeabilization of the medium and posterior cerebral arteries, despite the persistence of some arterial stenosis especially in the posterior circulation.

Moreover, as a complication of the immunosuppressive therapy, the patient developed a corneal abscess requiring specific antibiotic treatment and a rapid steroid tapering dose. A check-up ophthalmic examination revealed visual acuity limited to counting fingers in both eyes.

The patient was discharged on a treatment dose of 20 mg of prednisolone. A monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide cycle regimen was then initiated and it was maintained for 6 months. Immunosuppressive therapy was continued with 20 mg oral daily doses of azathioprine.

One year later, the patient had an important recovery of motor function. She was able to walk independently., severe visual loss persisted. A check-up electromyography was carried showing improvement of the latency responses and the conduction velocity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Motor Nerve Studies on check-up electromyography performed 1 year after hospital discharge (Abnormal results are shown in bold and the reference range in parentheses).

| Studied Nerves | Distal latency (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Conduction Velocity (m/s) | F-waves Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Median | 3.69 | 9.1 | 51.3 | 31 |

| (<3,7) | (>6) | (>48) | (<40) | |

| Right Ulnar | 3.67 | 7 | 49.6 | |

| (<3.2) | (>6) | (>48) | ||

| Right Tibial | 5.08 | 3.5 | – | 59.4 |

| (<5.5) | (>6) | (<40) | ||

| Left Tibial | 5.42 | 2.2 | 38.8 | 51.2 |

| (<5.5) | (>6) | (>42) | (<40) | |

| Right peroneal nerve | 4.17 | 1.72 | 32.9 | 58.1 |

| (<5) | (>3) | (>42) | (<40) |

3. Discussion

We, herein, report the case of a female patient presenting with aGBS, rapidly followed by cerebral large vessel vasculitis manifested by bilateral cortical blindness. Mild systemic symptoms shortly preceded GBS. A detailed work-up allowed us to retain the diagnosis of pSS with severe neurological features as the main extraglandular manifestations.

pSS is a complex systemic autoimmune disease primarily affecting the salivary and lachrymal glands. However, in some cases, extraglandular severe manifestations including, neurological manifestations may occur [2]. While the prevalence of PNS in pSS is estimated at about 20 %, the frequency of CNS involvement is widely variable [5]. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are also not fully understood [[10], [11], [12]]. A recent paper has suggested that cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis of the vasa nervosum is the most frequent neurologic manifestation of the PNS involvement (60–70 %). Axonopathy, mononeuritis multiplex and GBS have been also described (<1 %) [13].

In a French prospective cohort (ASSESS cohort) including 392 pSS patients, PNS involvement was identified in 16.1 % of the patients and only one patient, noticeably, presented a polyradiculoneuropathy [3].

Chronic polyradiculoneuropathy is rather reported when a demyelinating process is involved [14]. However, the acute form of polyradiculoneuropathy presenting during pSS was rarely reported before [10,12].

Acute motor axonal neuropathy in the absence of sicca signs and positivity to SSa and GM1 gangliosides antibodies were described in a young patient [10]. Mochizuki et al. [12] reported motor dominant axonal GBS form concomitant with cervical edematous myelitis as inaugural for both CNS and SNP manifestations of pSS with anti-SSA antibodies positivity. Tanaka et al. [11] speculated that GBS is a trigger factor for multiple mononeuropathy in the included pSS patient and that a pre-existing pSS related neuropathy could explain the severity of the clinical and electrophysiological findings [11].

To explain the observed GBS in our patient based on the aforementioned data, it is possible to speculate that a subclinical neuropathy in a pSS patients could be a worsening factor of GBS in this specific population [11], which could explain the severity of PNS features in our report.

CNS manifestations, including acute onset of headaches and cortical blindness, following the initial GBS signs by 3 weeks.

In the ASSESS cohort, cerebral vasculitis was reported to be one aspect of CNS involvement in pSS [15,16]. It manifested, among others, by headaches, optic neuritis, and multiple lesions on cerebral MRI [3]. Bilateral optic neuropathy as an initial symptom of pSS with significant improvement under cyclophosphamide was reported [17]. Homonymous hemianopsia associated with sensory polyneuropathy was described in one of the 16 patients included in the original cohort reported by Alexander et al. [18], focusing on CNS manifestations along with the presumed role of anti-SSA antibodies. On the other hand, Jeong et al. [19] described posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a young female patient with pSS with identified T2-weighted disturbances in the frontal and occipital lobes. This diagnosis could be discussed in the present case given the cortical blindness, parenchymal occipital involvement, and narrowing of the cerebral arteries. However, rapid artery repermeability visualized on the second cerebral MRI, performed only 3 weeks after the appearance of CNS symptoms, argued against the diagnosis.

Large-vessel cerebral-related vasculitis is another particularity in the present case. This was indeed rarely reported [6]. Unnikrishnan et al. [20] proposed the detection of wall thickening using high-resolution MRI vessel technique as a non-invasive method to detect cerebral vasculitis in pSS [21]. Large-vessel cerebral-related vasculitis has been reported in patients with high levels of anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, but an etiologic linkage between the two entities cannot be demonstrated yet. To date, data suggest that the inflammatory invasion, stimulated by an unknown trigger, starts from the adventitia at the level of vasa vasorum and continues to the intima leading to occlusion, located stenosis, and aneurysm formation [13].

Another study found that cerebrovascular events in pSSwere significantly associated with a anti-SSA positivity and high CNS domain of the ESSDAI [22].

The precise degree of CNS involvement in pSS is not fully outlined [20]. The reported frequency ranges from 0.3 to 48 % [5]. In an Italian series involving 120 patients, headaches were the most common feature of CNS involvement, followed by cognitive and psychiatric disturbances. Focal CNS signs were less observed in their study [20].

Notably, lung involvement is more observed in CNS-pSS patients and it is the strongest risk factor for CNS involvement [23]. This is consistent with the clinical findings in the present case.

The immunological disturbances observed in the present case were significant with low C4 serum levels, detection of anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies, and the presence of cryoglobulinemia type II.

Antibodies to SSA and SSB are associated with long disease duration, systemic manifestations (including vasculitis), and type II cryoglobulins [24]. They play a pathogenic role in pSS through direct tissue damage. In addition to antibodies to SSA and SSB, our patient also presented lymphopenia. This is in accordance with the early reported association of antibodies to SSA and SSB positivity with, among others, lymphopenia [25]. In 1994, Alexander et al. [23] demonstrated a significant association between the presence of antibodies to SSA response and both the clinical CNS active pSS involvement disease and the radiological abnormalities, including T 2 signal and/or cerebral angiograms abnormalities consistent with cerebral angiopathy [23]. A high prevalence of anti-SSA and SSB antibodies in pSS patients with neurological involvement was subsequently confirmed. In the study of Delalande et al. [26], among pSS patients with neurological involvement, these antibodies were detected in 43 % of the cohort during a mean follow-up of 10 years [27].

Massara et al. [5], demonstrating a direct and independent correlation between decreased C4 levels and CNS involvement in pSS.

The presence of both anti-Ro and anti-La in pSS have a prognostic value since they can alert to the possible association with systemic manifestations, including vasculitis and peripheral neuropathy [28].

In summary, this report reminds that when confronted to a patient with GBS, the first step is to thoroughly evaluate the condition by a careful anamnestic medical history and a systemic examination. While GBS is idiopathic in the majority of cases; in rare conditions, the etiology can be a life-threatening dysimmune disturbance. In such situations, GBS is in fact the first clinical sign of pSS and more broadly of an autoimmune condition. Rapid symptoms progression especially if associated with CNS or vascular signs, can point out a possible clinical picture caused by a vasculitis mechanism. This is important to consider because it allows an adapted rapid work-up and early initiation of appropriate therapy.

4. Conclusions

The present case illustrates a rare but a life-threatening neurological complication of pSS. First, it emphasizes that acute polyradiculoneuropathy can be an initial manifestation of pSS and that a careful evaluation should be performed to rule out any associated systemic condition. Secondly, even with severe clinical presentation, associated CNS involvement can rapidly respond to an early immunosuppressive therapy. Thirdly, the present case highlights that clinicians must take into consideration the immunological disturbances associated, which are thought to be involved in the pathogenic process of neurological involvement during pSS. This is helpful to plan the therapeutic approach and to improve estimates of prognosis for such serious condition.

Remarks concerning care the checklist.

Item 5d: no relevant past interventions for this patient.

Item 7: the chronological evolution of symptoms are well described in the abstract and clinical findings section of the present manuscript.

Item 8b: no difficulties concerning the diagnosis tools for this patient.

Item 12: it was not planified during the preparation of the present work.

Fundings

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Has data associated with your study been deposited into a publicly available repository?: No.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Dr Z.S.], upon request.

Consent statement for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient involved in this report. Our ethical local comities approved this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zakaria Saied: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Rania Zouari: Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation. Amine Rachdi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Fatma Nabli: Visualization, Resources. Samia Ben Sassi: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and her family for allowing us to present this case as a tool for education and learning.

References

- 1.Alunno A., Carubbi F., Bartoloni E., Cipriani P., Giacomelli R., Gerli R. The kaleidoscope of neurological manifestations in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019;37(118):192–198. 3. PMID: 31464676 [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldini C., Pepe P., Quartuccio L., Priori R., Bartoloni E., Alunno A., et al. Primary Sjogren's syndrome as a multi-organ disease: impact of the serological profile on the clinical presentation of the disease in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology. 2014;53(5):839–844. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvajal Alegria G., Guellec D., Mariette X., Gottenberg J.E., Dernis E., Dubost J.J., et al. Epidemiology of neurological manifestations in Sjögren’s syndrome: data from the French ASSESS Cohort. RMD Open. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobón G.J., Pers J.O., Devauchelle-Pensec V., Youinou P. Neurological disorders in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/645967/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massara A., Bonazza S., Castellino G., Caniatti L., Trotta F., Borrelli M., et al. Central nervous system involvement in Sjögren’s syndrome: unusual, but not unremarkable--clinical, serological characteristics and outcomes in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology. 2010;49(8):1540–1549. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasiloglu Z.I., Albayram S., Tasmali K., Erer B., Selcuk H., Islak C. A case of primary Sjögren’s syndrome presenting primarily with central nervous system vasculitic involvement. Rheumatol. Int. 2012;32(3):805–807. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1824-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ging K., Mono M.L., Sturzenegger M., Zbinden M., Adler S., Genitsch V., et al. Peripheral and central nervous system involvement in a patient with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2019;13(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2086-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flores-Chávez A., Kostov B., Solans R., Fraile G., Maure B., Feijoo-Massó C., et al. Severe, life-threatening phenotype of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: clinical characterisation and outcomes in 1580 patients (GEAS-SS Registry) Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2018;36(Suppl. 112):121–129. 3. PMID: 30156546 [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiboski C.H., Shiboski S.C., Seror R., Criswell L.A., Labetoulle M., Lietman T.M., et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;69(1):35–45. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210571. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awad A., Mathew S., Katirji B. Acute motor axonal neuropathy in association with Sjögren syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(5) doi: 10.1002/mus.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka K., Nakayasu H., Suto Y., Takahashi S., Konishi Y., Nishimura H., et al. Acute motor-dominant polyneuropathy as Guillain-Barré syndrome and multiple mononeuropathies in a patient with Sjögren’s syndrome. Intern. Med. 2016;55(18):2717–2722. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mochizuki H., Kamakura K., Masaki T., Hirata A., Nakamura R., Motoyoshi K. Motor dominant neuropathy in Sjögren's syndrome: report of two cases. Intern. Med. 2002:142–146. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argyropoulou, OuraniaD.; Tzioufas, AthanasiosG. Common and rare forms of vasculitis associated with Sjögren's syndrome. DOI: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000668.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Perzyńska-Mazan J., Maślińska M., Gasik R. Neurological manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Reumatologia. 2018;56(2):99–105. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.75521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori K., Iijima M., Koike H., Hattori N., Tanaka F., Watanabe H., et al. The wide spectrum of clinical manifestations in Sjögren’s syndrome-associated neuropathy. Brain J. Neurol. 2005;128(Pt 11):2518–2534. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gøransson L.G., Herigstad A., Tjensvoll A.B., Harboe E., Mellgren S.I., Omdal R. Peripheral neuropathy in primary sjogren syndrome: a population-based study. Arch. Neurol. 2006;63(11):1612–1615. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Béjot Y., Osseby G.V., Ben Salem D., Beynat J., Muller G., Moreau T., et al. Bilateral optic neuropathy revealing Sjögren’s syndrome. Rev. Neurol. 2008;164(12):1044–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander G.E., Provost T.T., Stevens M.B., Alexander E.L. Sjögren syndrome: central nervous system manifestations. Neurology. 1981;31(11):1391–1396. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong H.N., Suh B.C., Kim Y.B., Chung P.W., Moon H.S., Yoon W.T. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as an initial neurological manifestation of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Auton. Res. 2015;25(4):259–262. doi: 10.1007/s10286-015-0305-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unnikrishnan G., Hiremath N., Chandrasekharan K., Sreedharan S.E., Sylaja P.N. Cerebral large-vessel vasculitis in Sjogren's syndrome: utility of high-resolution magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging. J. Clin. Neurol. 2018;14(4):588–590. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morreale M., Marchione P., Giacomini P., Pontecorvo S., Marianetti M., Vento C., et al. Neurological involvement in primary Sjögren syndrome: a focus on central nervous system. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zippel C.L., Beider S., Kramer E., Konen F.F., Seeliger T., Skripuletz T., et al. Premature stroke and cardiovascular risk in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1048684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander E.L., Ranzenbach M.R., Kumar A.J., Kozachuk W.E., Rosenbaum A.E., Patronas N., et al. Anti-Ro(SS-A) autoantibodies in central nervous system disease associated with Sjögren’s syndrome (CNS-SS): clinical, neuroimaging, and angiographic correlates. Neurology. 1994;44(5):899–908. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moutsopoulos H.M., Zerva L.V. Anti-Ro (SSA)/La (SSB) antibodies and Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin. Rheumatol. 1990;9(1 Suppl. 1):123–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02205560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harley J.B., Alexander E.L., Bias W.B., Fox O.F., Provost T.T., Reichlin M., et al. Anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B) in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(2):196–206. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delalande S., de Seze J., Fauchais A.L., Hachulla E., Stojkovic T., Ferriby D., et al. Neurologic manifestations in primary Sjögren syndrome: a study of 82 patients. Medicine. 2004;83(5):280–291. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000141099.53742.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos-Casals M., Solans R., Rosas J., Camps M.T., Gil A., del Pino-Montes J., et al. Primary Sjögren syndrome in Spain: clinical and immunologic expression in 1010 patients. Medicine. 2008;87(4):210–219. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318181e6af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scofield R.H., Fayyaz A., Kurien B.T., Koelsch K.A. Prognostic value of Sjögren’s syndrome autoantibodies. J. Lab. Precis Med. 2018;3 doi: 10.21037/jlpm.2018.08.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Has data associated with your study been deposited into a publicly available repository?: No.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Dr Z.S.], upon request.