ABSTRACT

Albendazole (ABZ) is the primary treatment for alveolar echinococcosis (AE); however, its limited solubility impacts oral bioavailability, affecting therapeutic outcomes. In this study, various ABZ-solubilizing formulations, including albendazole crystal dispersion system (ABZ-CSD), albendazole hydrochloride-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate composite (TABZ-HCl-H), and albendazole hydroxyethyl sulfonate-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate composite (TABZ-HES-H), were developed and evaluated. Physicochemical properties as well as liver enzyme activity were analyzed and their pharmacodynamics in an anti-secondary hepatic alveolar echinococcosis (HAE) rat model were investigated. The formulations demonstrated improved solubility, exhibiting enhanced inhibitory effects on microcysts in HAE model rats compared to albendazole tablets. However, altered hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes in HAE model rats led to increased ABZ levels and reduced ABZ-SO production, potentially elevating drug toxicity. These findings emphasize the importance of dose adjustments in patient administration, considering the impact of alveolar echinococcosis on rat hepatic drug metabolism.

KEYWORDS: alveolar echinococcosis, albendazole, hepatic drug-metabolizing enzyme

INTRODUCTION

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a zoonotic parasitic disease resulting from human infection by the larval stage of the alveolar tapeworm, Echinococcus multilocularis. This larval stage originates in the liver and possesses exogenous and invasive growth characteristics, infecting the entire liver over the course of 5–10 years, similar to a tumor. This leads to it sometimes being referred to as “worm cancer.” In addition, it can metastasize and spread, causing secondary lesions in other organs, with a high mortality rate if left untreated or treated incompletely (1, 2). The disease is primarily distributed in locations with extensive livestock farming, including Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and North America, exhibiting a local epidemic trend. China contributes approximately 91% of global infections, with high prevalence in Qinghai, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Sichuan, influencing the health and economic development of agricultural communities (3, 4).

The current treatment approaches for AE involve the surgical removal of lesions accompanied by oral administration of antiparasitic drugs. However, approximately only 30% of patients are eligible for radical excision, leading to a low overall rate of AE recovery. Therefore, treatment predominantly consists of benzimidazole drugs. Albendazole (ABZ) acts as the only effective drug for AE treatment (5, 6). However, its limited solubility and dissolution rate result in poor bioavailability (7), resulting in a high recurrence rate following treatment (8). Consequently, enhancing ABZ’s dissolution and pharmacology is a current priority for research (9). New ABZ formulations encompass micro or nanoparticles (10), chitosan microspheres (CS-MPS) (11), liposomes (12), synthetic polymer tablets (13), and albendazole nanocrystals (ABZ-NCS) (14).

Prior investigations by our research group demonstrated that crystal solid dispersion technology founded on a particle size reduction strategy and salt formation technology based on the supersaturation effect could effectively enhance ABZ’s solubility and pharmacokinetic performance in normal rats (15–17). However, given that AE originates exclusively in the liver, this primary disease may impact the activity and expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes in the liver. Thus, it is critical to elucidate the pharmacokinetic behavior and biological mechanisms of the formulations in model rats.

In our current study, we employed the previously documented albendazole crystal dispersion system (ABZ-CSD), albendazole hydrochloride-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate composite (TABZ-HCl-H), and albendazole hydroxyethyl sulfonate-hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate composite (TABZ-HES-H) as a foundation for investigating their formulation properties, pharmacology in hepatic in situ model rats, expression levels and activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes in normal rats and hepatic in situ model rats, and pharmacokinetic behavior across both animal models. This study aims to provide a theoretical base for the further application of albendazole-related formulations in patients.

RESULTS

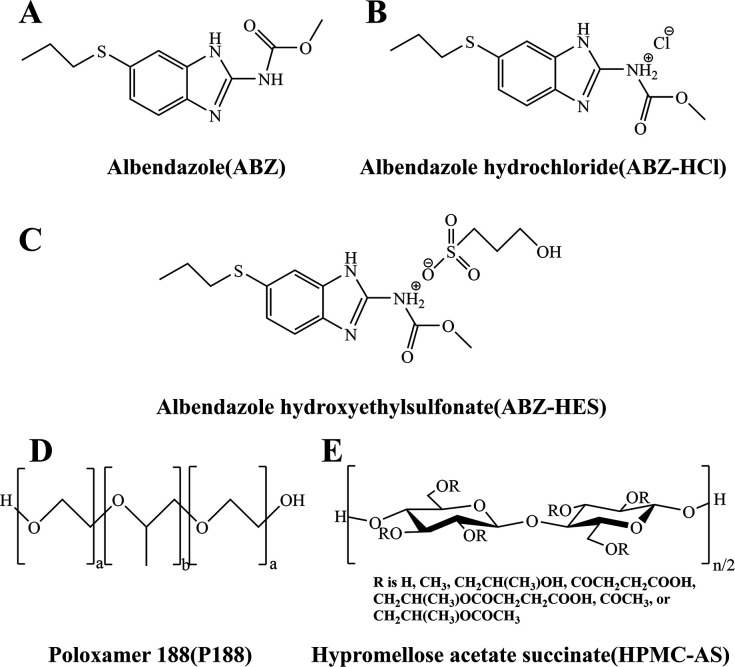

Physicochemical properties of the drug

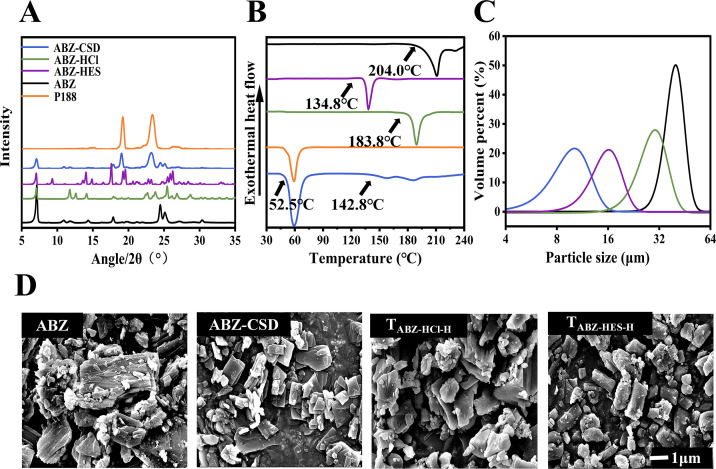

In our differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis, the melting temperature of pure ABZ was 204.0°C. ABZ-CSD exhibited three endothermic peaks, corresponding to Poloxamer 188 (P188), ABZ polymorph I, and ABZ polymorph II (18). The two polymorphs of ABZ may have undergone a polymorphic transformation throughout heating in the presence of P188. ABZ-HCl and ABZ hydroxyethyl sulfonate (ABZ-HES) exhibited melting temperatures of 183.8°C and 134.8°C, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Physicochemical properties of the drug formulations. (A) PXRD profiles for ABZ, P188, ABZ-CSD, ABZ-HCl, and ABZ-HES. (B) Thermal assessment of ABZ, P188, ABZ-CSD, ABZ-HCl, and ABZ-HES. (C) Particle size of ABZ, ABZ-CSD, ABZ-HCl, and ABZ-HES. (D) Scanning electron microscopy images of ABZ, ABZ-CSD, ABZ-HCl, and ABZ-HES.

From the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern, characteristic peaks for ABZ were observed at 2θ values of 7.1°, 10.96°, 11.78°, 14.32°, 17.86°, 24.48°, 25.12°, 27.24°, and 30.38°; ABZ-HCl at 2θ values of 7.02°, 11.79°, 12.56°, 14.06°, 17.88°, 22.64°, 23.74°, 25.38°, 26.74°, and 28.66°; and ABZ-HES at 2θ values of 7.04°, 9.26°, 14.02°, 14.86°, 17.6°, 19.22°, 25.48°, 25.86°, and 26.18°. The findings indicated that the crystal forms of the three samples were completely different, indicating that ABZ was successfully prepared as a salt (Fig. 1A).

Laser particle size analysis results demonstrated that the average particle size of DV (0.5) was the smallest for ABZ-CSD (10.48 µm), followed by ABZ-HES (14.14 µm), ABZ-HCl (27.29 µm), and ABZ (45.31 µm) (Fig. 1C).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) uncovered that the raw ABZ possessed a broader particle morphology and rougher surface with diverse layers and mostly appeared in agglomerated chunks. Following the alteration of the formulation, the drug crystal morphology of ABZ-HCl, ABZ-HES, and ABZ-CSD, the crystal size decreased, and ABZ-CSD and ABZ-HCl were predominantly rhombic plate-shaped. It was clear that all three formulations changed the crystal structure and morphology of ABZ (Fig. 1D), consistent with the results of the laser particle size analyzer test.

Analysis of drug effects in a secondary HAE rat model

Microcyst morphology, size, and inhibitory effect

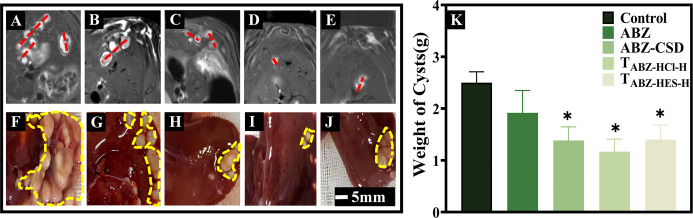

HAE model rats were randomly separated and marked, and drug treatment was administered over 4 weeks. Scans were performed using a small animal high-field MRI scanner. The control animals possessed more microcysts and larger volumes. Each treatment group exhibited a degree of inhibition in microcyst size and quantity, with relatively minor microcyst volumes and fewer microcysts (Fig. 2A through E). The control group livers had significant growth of E. multilocularis, with large volumes and multiple microcysts, many filled with cystic fluid. In the ABZ tablets group, the number of microcysts was lowered compared to the control group, with partial calcification. The ABZ-CSD group, TABZ-HCl-H group, and TABZ-HES-H group exhibited a significant reduction in microcyst numbers, with the majority presenting a hardened texture, noticeable calcification, and solidification (Fig. 2F through J). By removing the microcysts for weighing (Fig. 2K), the average wet weight was significantly lower in the ABZ-CSD group (1.36 ± 0.26 g), TABZ-HCl-H group (1.12 ± 0.21 g), TABZ-HES-H group (1.46 ± 0.24 g), and ABZ group (1.94 ± 0.43 g) compared to the control group (2.52 ± 0.20 g) (P < 0.05). The results indicated that all treatment groups inhibited the proliferation and growth of echinococcosis in infected rats, with the novel drug formulations demonstrating more obvious inhibitory effects, indicating that the improved ABZ formulation possessed improved therapeutic utility on HAE than historical drug ABZ Tablets.

Fig 2.

Morphology of hydatid microcysts in HAE rats in response to different drug treatments. MRI scans of rats with echinococcosis following the administration of (A) Control, (B) ABZ, (C) ABZ-CSD, (D) TABZ-HCl-H, and (E) TABZ-HES-H. Hydatid microcysts are indicated in red. Liver appearance post-treatment with (F) Control, (G) ABZ, (H) ABZ-CSD, (I) TABZ-HCl-H, and (J) TABZ-HES-H. Hydatid microcysts are depicted in yellow. (K) Microcyst weight across drug treatment groups (n = 6, each group). Compared to the ABZ group: *P < 0.05.

Pathological structure

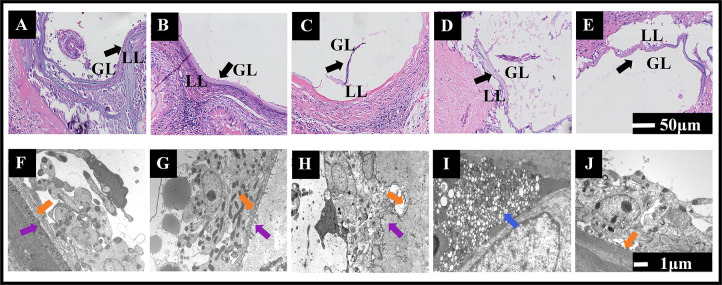

The microcyst wall of E. multilocularis comprises an interior germinal layer (GL) and an exterior laminated layer (LL). After staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), the control group exhibited a typical tissue structure emblematic of alveolar echinococcosis, with clear LL and GL, proliferating GL cells, many brood capsules or budding structures, and variable amounts of protoscoleces within the microcyst cavity. In the ABZ group, the GL was relatively intact, with only a low level of shedding, and the LL was densely arranged uniformly. In the ABZ-CSD, TABZ-HCl-H, and TABZ-HES-H groups, much of the E. multilocularis tissue structure was destroyed, with a thinner LL, degenerated, broken, shed, or absent GL, and no protoscoleces present in the microcyst cavity, with the most severe destruction identified in the TABZ-HCl-H group (Fig. 3A through E).

Fig 3.

Pathological and ultrastructural changes across hydatid tissues in response to treatment. H&E staining of hydatid tissues in HAE rats post-treatment: (A) Control, (B) ABZ, (C) ABZ-CSD, (D) TABZ-HCl-H, and (E) TABZ-HES-H. Transmission electron microscopy examinations of hydatid tissues post-treatment: (F) Control, (G) ABZ, (H) ABZ-CSD, (I) TABZ-HCl-H, and (J) TABZ-HES-H. Note:GL: germinal layer; LL: laminated layer; Syncytial bands (↑), Microvilli (↑), Necrosis (↑).

Transmission electron microscopy ultrastructure

The microcyst wall structure of E. multilocularis in the control group was typical, with continuous uniform thickness, intact and clear inner cell structure, tightly arranged cells, and complete organelles. The syncytial band was continuous and uniformly thick, with abundant microvilli and thick flocculent material. In the ABZ group, microcyst wall inner cells were tightly arranged, with lipid droplets and vacuoles present in the cytoplasm, thinner and discontinuous syncytial bands, and sparser surface microvilli. In the ABZ-CSD group, the microcyst wall inner cells were sporadically arranged, and some cells underwent necrosis, with dissolved and vacuolated syncytial bands and limited microvilli. In the TABZ-HCl-H group, the majority of the inner cells of the alveolar echinococcosis microcyst wall underwent necrosis, and the structure had severely dissolved, with no obvious syncytial bands or microvilli. In the TABZ-HES-H group, the microcyst wall structure of E. multilocularis was relatively complete, with tightly grouped and clear inner cells, partially destroyed cell contents, thinner and uneven syncytial bands, and limited microvilli (Fig. 3F through J).

Pharmacokinetic analysis in normal and HAE model rats

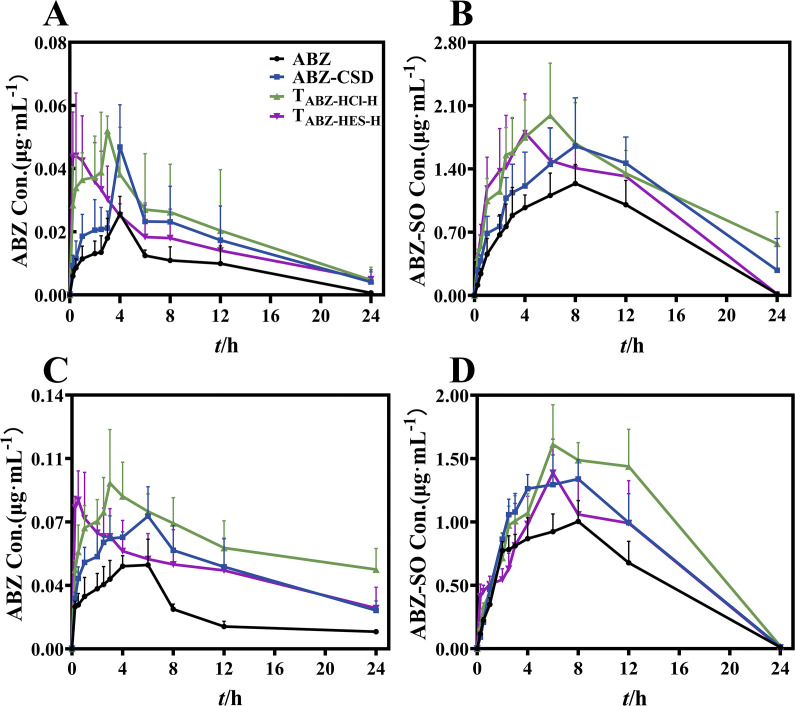

The blood drug concentration-time curve of rats following intragastric administration of various ABZ formulations is depicted in Fig. 4. Examination of the original drug (ABZ) and ABZ sulfoxide (ABZ-SO) in normal and HAE model rat groups exhibited that the maximum blood drug concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC0-t) of ABZ-CSD, TABZ-HCl-H, and TABZ-HES-H groups were increased compared to those in the ABZ Tablet group, with the most significant increase observed in the TABZ-HCl-H group.

Fig 4.

Average plasma concentration-time curve after intragastric administration of various ABZ preparations. (A) ABZ concentration-time curve for normal rats. (B) ABZ-SO concentration-time curve for normal rats. (C) ABZ concentration-time curve for HAE rats. (D) ABZ-SO concentration-time curve for HAE rats.

The original drug data evaluation demonstrated that in the HAE model rat group, the Cmax of the ABZ group was 1.6-fold higher than that of the normal group, and AUC0-t (0.49 ± 0.05 µg·h·mL−1) was 2.2 times that of the normal group (0.22 ± 0.04 ng·h·mL−1). The Cmax of the ABZ-CSD group was also 1.6-fold higher than that of the normal group, and the AUC0-t (1.06 ± 0.12 µg·h·mL−1) was 2.6 times that of the normal group (0.41 ± 0.07 µg·h·mL−1). The Cmax of the TABZ-HCl-H and TABZ-HES-H groups were 1.7 times that of the normal group, with the AUC0-t of TABZ-HCl-H group (1.44 ± 0.08 µg·h·mL−1) being 2.8 times that of the normal group (0.52 ± 0.13 µg·h·mL−1), and the AUC0-t of TABZ-HES-H group (1.04 ± 0.18 µg·h·mL−1) being 2.6 times that of the normal group (0.40 ± 0.10 µg·h·mL−1). This demonstrates a large accumulation of the parent drug in HAE model rats. After breakdown by hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes, ABZ-SO exhibited lower blood concentrations in HAE model rats than in the normal group. The results indicated that the Cmax of the ABZ group was 0.85 times that of the normal group, and the AUC0-t (13.62 ± 0.81 µg·h·mL−1) was significantly lower than that of the normal group (17.53 ± 1.37 µg·h·mL−1). The Cmax of the ABZ-CSD group was 0.74 times that of the normal group, and the AUC0-t (18.98 ± 1.23 µg·h·mL−1) was significantly lower than the normal group (25.76 ± 1.43 µg·h·mL−1). The Cmax of TABZ-HCl-H group was 0.76 times that of the normal group, and the Cmax of TABZ-HES-H group was 0.74 times that of the normal group. The AUC0-t of TABZ-HCl-H group (23.21 ± 2.31 µg·h·mL−1) and TABZ-HES-H group (17.43 ± 1.89 µg·h·mL−1) were lower than the normal group (27.61 ± 0.18 µg·h·mL−1) and (24.73 ± 1.50 µg·h·mL−1), respectively. This indicates that drug metabolism in HAE model rats is limited, and the production of ABZ-SO, the active ingredient for killing parasites, is reduced. Comprehensive analysis of the pharmacokinetic data of the two groups determined that the blood concentration and bioavailability of the parent drug in the HAE model rats were higher than the normal group, while the metabolic product ABZ-SO was lowered. This may be due to the influence of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes during the drug’s conversion process. The detailed findings of the pharmacokinetic parameters are outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of diverse ABZ dosage forms in normal and HAE rats

| Control | HAE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABZ | ABZ-CSD | TABZ-HCl-H | TABZ-HES-H | ABZ | ABZ-CSD | TABZ-HCl-H | TABZ-HES-H | ||

| ABZ | AUC(0-t)(μg· h·mL−1) | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.07a | 0.52 ± 0.13a | 0.40 ± 0.10a | 0.49 ± 0.05b | 1.06 ± 0.12ab | 1.44 ± 0.08ab | 1.04 ± 0.18ab |

| Tmax(h) | 3.80 ± 0.45 | 3.60 ± 0.89 | 2.4 ± 1.29 | 1.20 ± 0.76a | 4.60 ± 1.34 | 3.90 ± 1.95 | 2.60 ± 1.08 | 1.60 ± 1.08a | |

| Cmax(μg· h·mL−1) | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01a | 0.06 ± 0.01a | 0.05 ± 0.01a | 0.05 ± 0.01b | 0.08 ± 0.01ab | 0.10 ± 0.02ab | 0.09 ± 0.01ab | |

| t1/2(h) | 3.11 ± 1.86 | 5.05 ± 1.16 | 6.68 ± 2.23a | 6.61 ± 1.94a | 5.40 ± 2.66 | 11.47 ± 3.18a | 11.88 ± 3.13a | 10.35 ± 4.56 | |

| ABZ-SO | AUC(0-t)(μg· h·mL−1) | 17.53 ± 1.37 | 25.76 ± 1.43a | 27.61 ± 1.27a | 24.73 ± 1.50a | 13.62 ± 0.81b | 18.98 ± 1.23ab | 23.21 ± 2.31ab | 17.43 ± 1.89ab |

| Tmax(h) | 7.20 ± 1.10 | 6.80 ± 1.79 | 5.00 ± 1.41 | 3.90 ± 1.34a | 8.40 ± 2.19 | 7.20 ± 1.10 | 6.40 ± 0.89 | 5.00 ± 1.41a | |

| Cmax(μg· h·mL−1) | 1.29 ± 0.16 | 1.96 ± 0.38a | 2.24 ± 0.34a | 2.01 ± 0.34a | 1.10 ± 0.07b | 1.45 ± 0.17ab | 1.70 ± 0.25ab | 1.48 ± 0.16ab | |

| t1/2(h) | 2.77 ± 0.33 | 6.28 ± 4.81 | 8.17 ± 3.27a | 2.66 ± 0.61 | 2.57 ± 0.47 | 2.78 ± 0.41 | 2.89 ± 0.49 | 2.29 ± 0.17 | |

Note: Vs. ABZ group, *p < 0.05. Vs. The same drug dosage forms between the normal and the HAE rats.

p < 0.05.

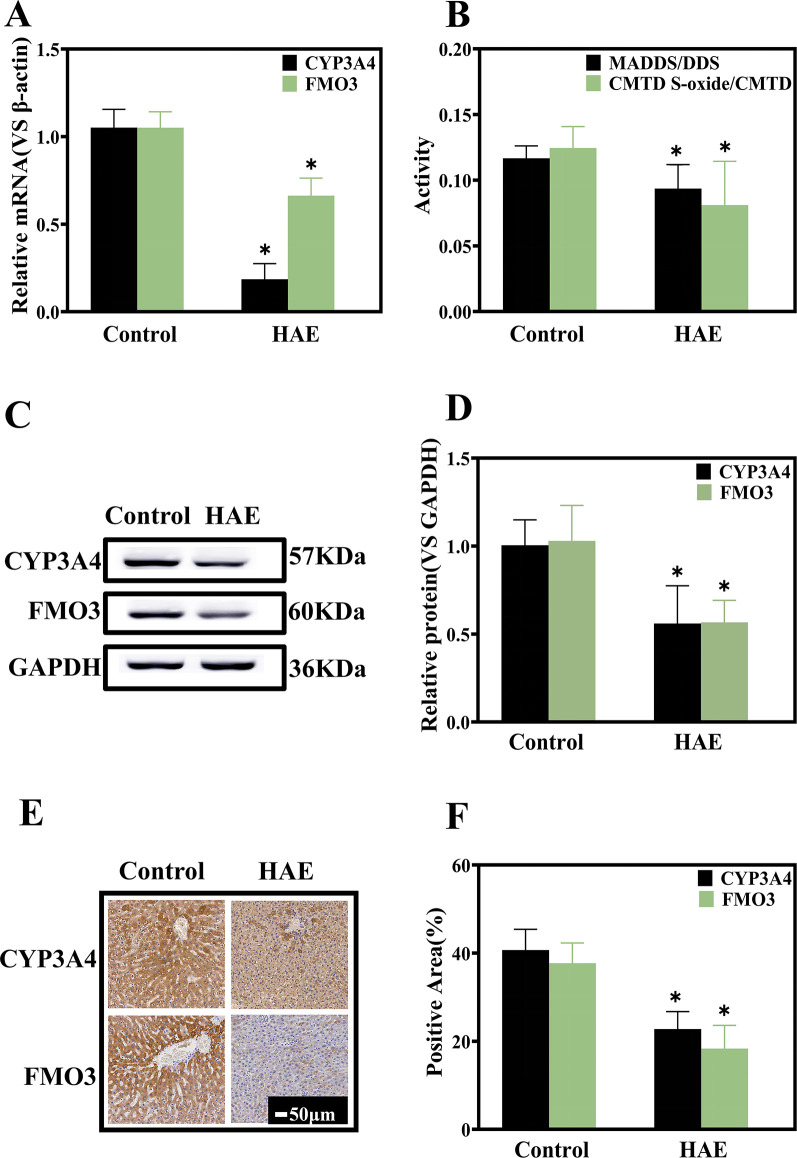

Characterization of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzyme expression levels and activities

ABZ enters the bloodstream and is transported to the liver, predominantly metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) and flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) into ABZ sulfoxide (ABZ-SO) and ABZ sulfone (ABZ-SO2) (19, 20), with ABZ-SO acting as the active anthelmintic component (21, 22). Studies have demonstrated that cytochrome P4503A4 (CYP3A4) and flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)subtypes are primarily associated with the metabolism of ABZ, with CYP3A4 participating in the metabolism of ABZ-SO enantiomer (+), while the ABZ-SO enantiomer (−) is primarily associated with FMO3 (23, 24). The expression levels of hepatic drug enzymes CYP3A4 and FMO3 were detected according to messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression. The results indicated that the expression of both CYP3A4 and FMO3 in the normal group was higher than in the HAE rat group (Fig. 5A, C, and D). The expression of these two enzymes in the liver was examined through immunohistochemistry. It was identified that the expression of CYP3A4 and FMO3 was significantly lowered in the HAE model rat group compared to the high expression in the normal group, consistent with the results of Western blot (WB) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 5E and F). In addition, we employed in vivo drug probe methods to characterize the enzyme activities of CYP3A4 and FMO3, with dapsone as the probe drug for the CYP3A4 enzyme and cimetidine as the probe drug for FMO3 (25, 26). The ratio of the concentration of the parent drug and metabolite was utilized to indicate enzyme activity. The results indicated that the activities of CYP3A4 and FMO3 in the HAE model rat group were lower than those of the normal group (Fig. 5B). This suggests that E. multilocularis infection can trigger a reduction in both the expression levels of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes and their activities, causing significant differences in the pharmacokinetic behavior of the drug in normal and model rats.

Fig 5.

Hepatic drug enzyme expression levels and activity assays. (A) Relative mRNA expression of CYP3A4 and FMO3 (n = 5, each group). (B) Enzyme activity of CYP3A4 and FMO3 (n = 5, each group). (C) Representative Western blot and (D) quantification (n = 5, each group). (E) Immunohistochemical examination and (F) quantification of CYP3A4 and FMO3 (n = 4, each group). Vs. Control group, *P < 0.05

DISCUSSION

ABZ acts as a broad-spectrum anthelmintic drug from the benzimidazole class, widely employed to treat nematode, cestode, trematode, and protozoan infections. The drug enters the body and inhibits the aggregation of β-tubulin, inhibiting glycogen uptake and causing cell death (27). The absorption rate of oral ABZ is approximately 1% to 5%, related to its limited water solubility and rapid liver metabolism, leading to insufficient therapeutic effects (28). To overcome this challenge, our research group prepared ABZ nanocrystals and ABZ salt-polymer material composites to increase oral bioavailability and pharmacodynamics (15–17). However, in our prior pharmacokinetic studies, we used normal rats for experiments without evaluating the pharmacokinetic behavior of the drug in secondary model rats. It is well established that ABZ exerts its pharmacological effects by being converted to ABZ sulfoxide (ABZ-SO) under the action of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes. Therefore, whether liver infiltration by alveolar echinococcosis affects drug metabolism is an area requiring investigation, and whether it is due to the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes or their activities. It was determined that the three modified new formulations could elevate the drug’s blood concentration and improve the bioavailability of ABZ. The AUC0-t and Cmax of the parent drug were higher in the HAE model rat group than in the normal group, while the AUC0-t and Cmax of the metabolic product ABZ-SO were reduced in the HAE model rat group compared to the normal group. This indicates that the metabolism of ABZ in HAE model rats is slower than in the normal group, with lower production of the active component ABZ-SO and more residual parent drug.

For clinical treatment of echinococcosis infection, long-term and high-dose administration of ABZ is necessary, causing toxic effects and side effects in the liver, gastrointestinal system, and other organs, with the most widespread symptoms being jaundice, anorexia, vomiting, increased liver transaminases, and neutropenia due to bone marrow suppression, which can be reduced by stopping the medication (27, 29, 30). Related studies have demonstrated that ABZ has higher cytotoxicity compared to its metabolites, and drug metabolism can cause detoxification (31). This study determined that the metabolism of ABZ in HAE model rats was significantly reduced. The expression levels and activities of the liver enzymes CYP3A4 and FMO3 in HAE model rats were significantly lower compared to normal rats, resulting in reduced reaction with ABZ, a substantial accumulation of the parent drug in the body, and a possible elevation in toxicity. In clinical applications, while considering elevated drug blood concentration, the toxic effects of drugs on the body after increasing the concentration should be considered. The use of liver drug-metabolizing enzymes or dosing adjustment can be applied to optimize drug utilization in the body.

During E. multiloculari infection animal model construction, most methods involve intraperitoneal inoculation of protoscoleces (32, 33). However, this approach causes significant parasite proliferation in the abdominal cavity of the animal after 6 weeks of modeling, with limited effects on the liver (34). In this study, secondary hepatic AE infection rats were developed by directly inoculating protoscoleces into the liver. Successful modeling resulted in the development of multiple microcysts on the liver lobes of the rats, with only a few cases of metastasis to the lungs, spleen, or abdominal cavity. This simulates the primary infection in the liver, followed by the spread through lymph nodes or blood circulation to other tissues and organs. This study assessed the success rate of modeling by integrating ultrasound and small animal magnetic resonance imaging. The use of small animal magnetic resonance imaging limited animal injury relative to a random selection of animal models for macroscopic observation. It proved more effective than ultrasound in visualizing the size, shape, and boundaries of microcysts in the lesion area (35). Given that this study predominantly evaluated the therapeutic effects, the use of small animal magnetic resonance imaging to characterize successful HAE infection in rats was more advantageous.

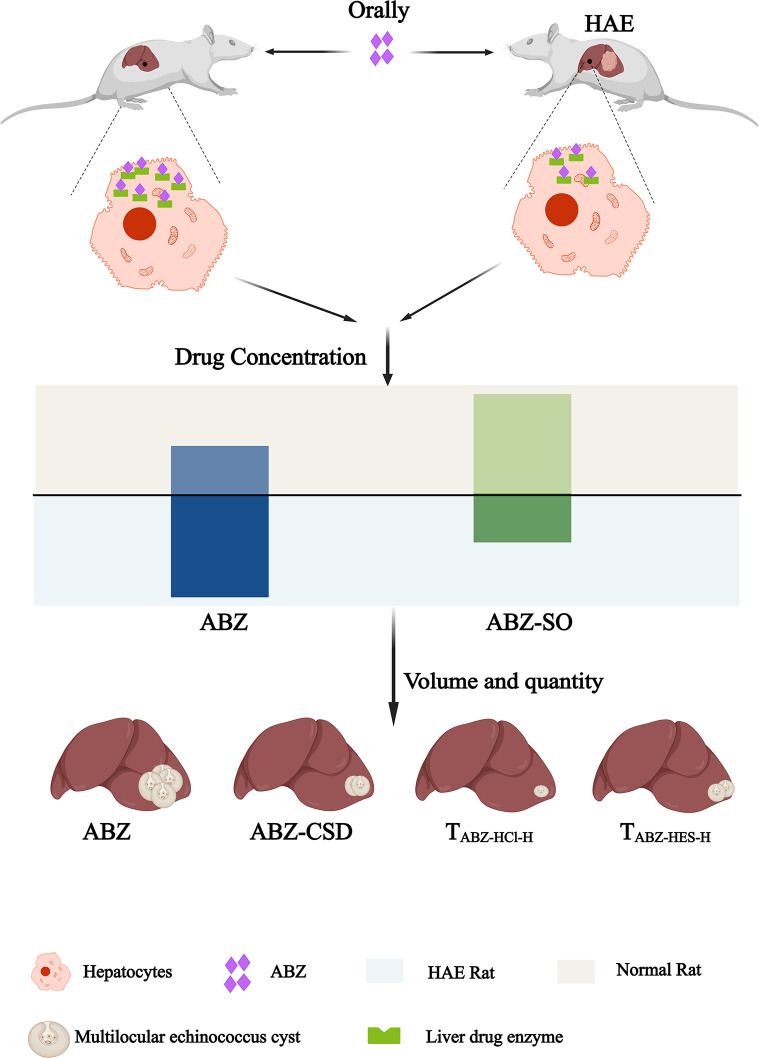

In summary, this study demonstrated that the ABZ-CSD, TABZ-HCl-H, and TABZ-HES-H groups exhibited improved results with respect to drug metabolism kinetics and anti-echinococcosis capability compared to commercially available ABZ tablets. Further analyses and evaluation regarding toxicity, immune system, and drug side effects are required. The expression levels and activities of liver drug-metabolizing enzymes CYP3A4 and FMO3 were lowered in HAE model rats compared to normal rats, causing impaired ABZ metabolism, excessive accumulation of the parent drug in the body, and potentially increased toxicity. To enhance the therapeutic effect of ABZ in alveolar echinococcosis-infected hosts without exacerbating toxicity, future patient treatment should consider changes in dosage form and drug dose adjustments as well as interventions targeting liver drug-metabolizing enzymes to more effectively enhance the bioavailability of ABZ (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Diagram summarizing the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

ABZ (ABZ, CAS No.: 54965–21-8, purity 98.0%) and Poloxamer 188 (P188, CAS No.: 691397–13-4) were purchased from Beijing Ouhe Technology Co., Ltd. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate (HAPMC-AS, CAS No.: 71138–97-1) was purchased from Henan Wokas Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. ABZ standard (ABZ, purity 98.0%), ABZ sulfoxide standard (ABZ-SO, CAS No.: 54029–12-8, purity 96.1%), and mebendazole standard (MBZ, CAS No.: 31431–39-7, purity 98.1%) were obtained from Chemtek Company. ABZ Tablets (approval number: H12020497) were purchased from Sino-American Tianjin Smith Kline Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. CYP3A4 and FMO3 antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Company. Methanol was chromatographic grade, while other reagents were analytical grade. The chemical structures of the drugs and polymer materials employed in the experiment are depicted in Fig. 7.

Fig 7.

Chemical structures of (A) ABZ, (B) ABZ hydrochloride, (C) ABZ hydroxyethyl sulfonate, (D) Poloxamer 188, and (E) hypromellose acetate succinate.

Animals

The Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University approved all animal protocols (Ethics approval No. P-SL-2019054). Healthy male SD rats, with an average weight of 200 ± 20 g, were obtained from the Beijing Vital River Experimental Animal Technology Co., Ltd [License number: SCXK (Beijing) 2016-0011]. After all experiments, animals were placed in a small animal carbon dioxide inhalation euthanasia box. Carbon dioxide was administered into the box at a rate of 30% to 70% of the volume of the euthanasia box per minute and maintained for a minimum of 1 minute after the cessation of breathing, according to the American Veterinary Association (AVMA) euthanasia guidelines.

Drug preparation

ABZ and P188 were combined in a 3:7 ratio and dissolved in chloroform. Following rotary evaporation and drying, ABZ-CSD was acquired, and ABZ and P188 were purified through chloroform rotary evaporation. ABZ-HCl was acquired by dissolving concentrated HCl and ABZ in tetrahydrofuran, stirring continuously at 30°C for 24 hours, filtering, rinsing with acetone three times, and vacuum drying overnight. ABZ-HES was acquired by dissolving HES and ABZ in tetrahydrofuran, stirring continuously at 30°C for 72 hours, filtering, rinsing with acetone three times, vacuum drying overnight, and sealing.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Continuous scanning was conducted using an X'pert Powder X-ray Diffractometer (D-max 2500 PC, Rigaku, Japan) at a scanning speed of 1°·min−1, scanning range 2θ = 5° to 35°, and a scanning step size 0.01°·2θ−1.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Samples of the various ABZ formulations (5.0–10.0 mg) were placed in aluminum pans within a thermal analyzer (STA449F3-DSC200F3, Netzsch, Germany) under a nitrogen flow rate of 50 mL·min−1, heating rate 20°C·min−1, and a temperature range of 25°C to 250°C.

Scanning electron microscopy

Samples were evenly dispersed on a sample holder with a conductive adhesive. The loose powder was blown away using a rubber bulb. Images were obtained and observed using a scanning electron microscope (JEM-IT700 HR, JEOL Ltd., Japan).

Laser particle size analyzer

Particle size was assessed using a laser particle size analyzer (MASTERSIZER SIZER2000, Shandong Nike, China) utilizing the dry measurement method. Parameters were established as follows: refractive index 1.674, dispersion medium refractive index 1.00, sample detection duration 10 seconds, background time 12 seconds, dispersion pressure 2.0 Bar, sample loading speed 50%, slit width 1.5 mm, obscuration rate 1.0% to 5.0%.

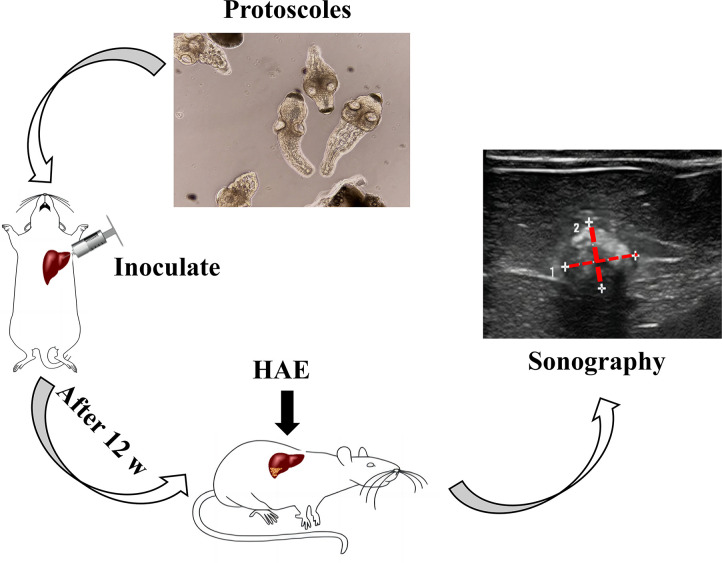

Establishment and confirmation of secondary HAE infection in rats

Aseptically collected protoscoleces from the abdominal cavity of infected gerbil individuals were suspended in a 2000·mL−1 suspension. Sixty SD rats were inoculated with 0.2 mL of the suspension through direct visual hepatic puncture under laparotomy. After 90 days post-infection, color Doppler ultrasound (ZS3, Mindray, China) was employed for screening, and positive rats were chosen for subsequent experiments. To enhance the clarity of the HAE modeling and screening process, a schematic diagram illustrating the rat modeling process (Fig. 8) was created. It should be noted that this diagram does not depict any qualitative or quantitative results. In selecting an ultrasonic image, we aimed to present a representative B-mode image of a successfully modeled rat. However, given that the rat’s liver possesses three-dimensional characteristics, it is important to acknowledge that B-mode ultrasound can only display two-dimensional images through echo detection. Hence, we trimmed and marked the most prominent abnormal echo area to emphasize the location of the liver cysts.

Fig 8.

Establishment and ultrasound assessment of HAE.

Metabolic kinetics of drugs in rats

A total of 20 normal SD rats and 20 HAE model rats were randomly separated into ABZ, ABZ-CSD, TABZ-HCl-H, and TABZ-HES-H groups, each containing five rats. The right internal jugular vein catheter model was constructed in rats prior to administration (36). The corresponding drug formulations were administered orally at doses of 25.0 mg·kg−1. Blood samples of approximately 500 µL were obtained from the jugular vein (37) after 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours following administration and incubated with EDTA-2Na for plasma separation. Plasma was combined with methanol at a 1:2 ratio and centrifuged, and the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of a mebendazole (MBZ) internal standard solution. After filtration through a 0.22-µm membrane, samples were examined using a previously established detection method and conditions (UPLC-MS/MS) with a Fourier Transform Ultra High-Resolution Liquid Mass Spectrometer (*-Thermo Q Exactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific, America). The pharmacokinetic data were analyzed using DAS 2.0 software.

Pharmacological study of HAE model rats

Rat grouping and magnetic resonance identification: Model rats were separated into five groups, each containing six rats. The control group was administered a suspension of 0.9% saline +P188 +HAPMC-AS, acting as the infection control. The ABZ group received a suspension of crushed ABZ Tablets, while the ABZ-CSD, TABZ-HCl-H, and TABZ-HCl-H groups received the corresponding suspensions at an oral dose of 25 mg·kg−1·d−1. Following 4 weeks of administration, the rats underwent scanning on a 7-Tesla small animal high-field magnetic resonance scanner (PharmaScan70/16, RK, America) to examine the lesion volume and location (2). Observation of liver lesion structure and measurement of microcyst wet weight: The livers of experimental rats were dissected, rinsed with PBS, and photographed to identify the lesion site. The intracystic lesions were excised and weighed to determine the average wet weight and standard deviation (x̄ ±s) (3). H&E staining: Liver tissue from experimental group rats underwent fixing in 10% formalin, dehydrated, infiltrated with paraffin, embedded, sectioned, and stained. After counterstaining with hematoxylin, sections were dehydrated and cleared, and coverslips were applied with neutral gum. The cystic area was viewed under an optical microscope (4). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM): Liver tissue containing AE lesions from experimental group rats was pre-fixed using 3% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a series of acetone, embedded in Ep812, and sectioned. After staining using uranyl acetate and lead citrate, the sections were observed using a FLASH transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400, JEOL, Japan) to characterize the microcyst wall and cell structure.

Identification of CYP3A4 and FMO3 expression levels

qPCR assay: Total RNA was isolated from rat liver samples using Trizol and reverse-transcribed into cDNA based on the instructions of the reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America). CYP3A4 and FMO3 were amplified using the TB Green Premix Ex Taq II reagent kit, with β-actin used as an internal reference. The primer sequences are outlined in Table 2. The program was established as follows: 95°C for 2 minutes; 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 34 seconds (40 cycles); 95°C for 10 seconds; 60°C for 1 minute; 50°C for 30 seconds, in a total reaction volume of 15 µL (2). Western blot (WB): Rat liver tissues underwent lysis with RIPA/PMSF (100:1) to extract total protein. The protein concentration was quantified using a BCA protein concentration determination kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America). Equal concentrations of protein were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking with skim milk for 1 hour, the membranes were incubated with diluted primary antibodies against CYP3A4 (1:4,000) and FMO3 (1:1,000) at 4°C overnight. The following day, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies, developed, and subjected to densitometric analysis. GAPDH was employed as the loading and analysis control (3). Immunohistochemistry: Liver tissues were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Following dewaxing, antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, and serum blocking was conducted for 20 minutes. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies against CYP3A4 (1:500) and FMO3 (1:500) at 4°C overnight. The following day, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 minutes, developed with DAB, counterstained, and mounted. Images as well as the percentage of positive area across each image were characterized using a panoramic tissue cell quantitative analysis system (*Tissue FAXS, TG, Austria). Hematoxylin-stained nuclei appeared blue, while DAB-positive expression appeared brownish-yellow.

TABLE 2.

Primer sequences utilized for real-time PCR

| Gene | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | TCTGTGCAGAAGCATCGAGTG | TGGGAGGTGCCTTATTGGG |

| FMO3 | TCAGGAGCCAGGAACGCCATC | ACAAGGAACAAAGCAATGAGCACTG |

| β-actin | CGCTTGGGTGCTTGCTATAAATTCG | CTGCTATTGCTCCTGCCTCTGAAC |

Activity detection of CYP3A4 and FMO3

The in vivo drug probe approach was employed to characterize the activity of hepatic drug enzymes. Ten normal SD rats and ten HAE model rats were randomly separated into two groups, with five rats per group. Rats in the two groups for the detection of CYP3A4 activity were intraperitoneally injected with the probe drug Dapsone at 10 mg·kg−1 (38), and those in the two groups for the detection of FMO3 activity received oral cimetidine at 20 mg·kg−1. Blood samples (500 µL) were obtained from the jugular vein 2 hours following administration. The UPLC-MS/MS approach was used for analysis, with metronidazole employed as an internal standard. The ratio of the concentration of the resulting metabolites relative to the concentration of the corresponding probe drug was computed as an indicator of enzyme activity in vivo.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 was employed for statistical analysis of the data. Measurement data were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ±s). One-way ANOVA was utilized for multiple-group comparisons, an Uncorrected Fisher’s LSD method was employed for intergroup comparisons, and a t-test was used for two-group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Qinghai Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Project No. 2019-SF-131), Qinghai Key Laboratory of Economics Research, Department of Science and Technology of Qinghai Province (Project No.2020-ZJ-Y01), and The Science and Technology of Qinghai Province (No. 2022-QY-201)

Contributor Information

Chunhui Hu, Email: chunhuihu@qhu.edu.cn.

Haining Fan, Email: fanhaining@medmail.com.cn.

Audrey Odom John, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This research met the ethical requirements and was reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (approval No. P-SL-2019054).

REFERENCES

- 1. Vuitton DA, Mantion G, Million L, Bresson-Hadni S. 2020. Échinococcose alvéolaire. Rev Prat 70:754–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xu K, Ahan A. 2020. A new dawn in the late stage of alveolar echinococcosis "parasite cancer. Med Hypotheses 142:109735-38. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bresson-Hadni S, Spahr L, Chappuis F. 2021. Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. Semin Liver Dis 41:393–408. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woolsey ID, Miller AL. 2021. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato and Echinococcus multilocularis: a review. Res Vet Sci 135:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, Li J, Vuitton DA, Zhang W, McManus DP. 2019. Echinococcosis: advances in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00075-18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00075-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao CH, Wang JY, Shi F, Steverding D, Wang X, Yang YT, Zhou XN. 2018. Field evaluation of an immunochromatographic test for diagnosis of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Parasit Vectors 11:311. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2896-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siles-Lucas M, Casulli A, Cirilli R, Carmena D. 2018. Progress in the pharmacological treatment of human cystic and alveolar echinococcosis: compounds and therapeutic targets. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wangda K, Kumar N, Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Rizvi I, Uniyal R, Pandey S, Malhotra KP, Verma R, Sharma PK, Parihar A, Jain A. 2023. Value of whole-body MRI for the assessment of response to albendazole in disseminated neurocysticercosis: a prospective follow-up study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 117:271–278. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trac097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu X, Qian X, Gao C, Pang Y, Zhou H, Zhu L, Wang Z, Pang M, Wu D, Yu W, Kong F, Shi D, Guo Y, Su X, Hu W, Yan J, Feng X, Fan H. 2022. Advances in the pharmacological treatment of hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: from laboratory to clinic. Front Microbiol 13:953846. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.953846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Albalawi AE, Alanazi AD, Baharvand P, Sepahvand M, Mahmoudvand H. 2020. High potency of organic and inorganic nanoparticles to treat cystic echinococcosis: an evidence-based review. Nanomaterials (Basel) 10:2538–2555. doi: 10.3390/nano10122538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang S, Wang S, Wang W, Dai Y, Qiu Z, Ke W, Geng M, Li J, Li K, Ma Q, Li F. 2021. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of albendazole chitosan microspheres with intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the treatment of spinal echinococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e0079521. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00795-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang H, Zhao J, Chen B, Ma Y, Li Z, Shou X, Wen L, Yuan Y, Gao H, Ruan J, Li H, Lu S, Gong Y, Wang J, Wen H. 2020. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution study of liposomal albendazole in naturally Echinococcus granulosus infected sheep by a validated UPLC-Q-TOF-MS method. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1141:122016. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2020.122016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansuri S, Kesharwani P, Tekade RK, Jain NK. 2016. Lyophilized mucoadhesive-dendrimer enclosed matrix tablet for extended oral delivery of albendazole. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 102:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pensel P, Paredes A, Albani CM, Allemandi D, Sanchez Bruni S, Palma SD, Elissondo MC. 2018. Albendazole nanocrystals in experimental alveolar echinococcosis: enhanced chemoprophylactic and clinical efficacy in infected mice. Vet Parasitol 251:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu C, Liu Z, Liu C, Li J, Wang Z, Xu L, Chen C, Fan H, Qian F. 2019. Enhanced oral bioavailability and anti-echinococcosis efficacy of albendazole achieved by optimizing the "spring" and "parachute”. Mol Pharm 16:4978–4986. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu C, Liu Z, Liu C, Zhang Y, Fan H, Qian F. 2020. Improvement of antialveolar echinococcosis efficacy of albendazole by a novel nanocrystalline formulation with enhanced oral bioavailability. ACS Infect Dis 6:802–810. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu C, Zhang F, Fan H. 2021. Improvement of the bioavailability and anti-hepatic alveolar echinococcosis effect of albendazole-isethionate/hypromellose acetate succinate (HPMC-AS) complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e0223320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02233-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Calvo NL, Arias JM, Altabef AB, Maggio RM, Kaufman TS. 2016. Determination of the main solid-state form of albendazole in bulk drug, employing Raman spectroscopy coupled to multivariate analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal 129:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Capece BPS, Virkel GL, Lanusse CE. 2009. Enantiomeric behaviour of albendazole and fenbendazole sulfoxides in domestic animals: pharmacological implications. Vet J 181:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miró V, Lifschitz A, Viviani P, Rocha C, Lanusse C, Costa L, Virkel G. 2020. In vitro inhibition of the hepatic S-oxygenation of the anthelmintic albendazole by the natural monoterpene thymol in sheep. Xenobiotica 50:408–414. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2019.1644390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saraner N, Özkan GY, Güney B, Alkan E, Burul-Bozkurt N, Sağlam O, Fikirdeşici E, Yıldırım M. 2016. Determination of albendazole sulfoxide in human plasma by using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1022:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pandya JJ, Sanyal M, Shrivastav PS. 2017. Simultaneous densitometric determination of anthelmintic drug albendazole and its metabolite albendazole sulfoxide by HPTLC in human plasma and pharmaceutical formulations. Biomed Chromatogr 31:1–27. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wagmann L, Meyer MR, Maurer HH. 2016. What is the contribution of human FMO3 in the N-oxygenation of selected therapeutic drugs and drugs of abuse?. Toxicol Lett 258:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rawden HC, Kokwaro GO, Ward SA, Edwards G. 2000. Relative contribution of cytochromes P-450 and flavin-containing monoxygenases to the metabolism of albendazole by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 49:313–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00170.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma W, Wang W, Huang X, Yao G, Jia Q, Shen J, Ouyang H, Chang Y, He J. 2020. HPLC-MS/MS analysis of Aconiti lateralis radix praeparata and its combination with red ginseng effect on rat CYP450 activities using the cocktail approach. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020:8603934. doi: 10.1155/2020/8603934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cashman JR. 2000. Human flavin-containing monooxygenase: substrate specificity and role in drug metabolism. Curr Drug Metab 1:181–191. doi: 10.2174/1389200003339135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chai JY, Jung BK, Hong SJ. 2021. Albendazole and mebendazole as anti-parasitic and anti-cancer agents: an update. Korean J Parasitol 59:189–225. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2021.59.3.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dayan AD. 2003. Albendazole, mebendazole and praziquantel. review of non-clinical toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Acta Trop 86:141–159. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Piloiu C, Dumitrascu DL. 2021. Albendazole-induced liver injury. Am J Ther 28:e335–e340. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Atayi Z, Borji H, Moazeni M, Saboor Darbandi M, Heidarpour M. 2018. Zataria Multiflora would attenuate the hepatotoxicity of long-term albendazole treatment in mice with cystic echinococcosis. Parasitol Int 67:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Radko L, Minta M, Jedziniak P, Stypuła-Tręba S. 2017. Comparison of albendazole cytotoxicity in terms of metabolite formation in four model systems. J Vet Res 61:313–319. doi: 10.1515/jvetres-2017-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xin Q, Li H, Yuan M, Song X, Jing T. 2022. Effects of Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes infection and drug treatment on the activities of biotransformation enzymes in mouse liver. Parasitol Int 89:102563. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2022.102563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weingartner M, Stücheli S, Jebbawi F, Gottstein B, Beldi G, Lundström-Stadelmann B, Wang J, Odermatt A. 2022. Albendazole reduces hepatic inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum-stress in a mouse model of chronic Echinococcus multilocularis infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 16:e0009192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Charbonnet P, Bühler L, Sagnak E, Villiger P, Morel P, Mentha G. 2004. Long-term followup of patients with alveolar Echinococcosis. Ann Chir 129:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.anchir.2004.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang G, Mou Y, Fan H, Li W, Cao Y, Bao H. 2022. 7T small animal MRI research for hepatic alveolar Echinococcosis. Top Magn Reson Imaging 31:53–59. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shiels RG, Hewage W, Vidimce J, Pearson AG, Grant G, Wagner KH, Bulmer AC. 2021. Pharmacokinetics of bilirubin-10-sulfonate and biliverdin in the rat. Eur J Pharm Sci 159:105684. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Avedissian SN, Pais GM, Pham M, Liu J, Chang J, Hlukhenka K, Prozialeck W, Griffin B, Gulati A, Joshi MD, Mu Y, Scheetz MH. 2022. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in a pregnancy rat model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0005622. doi: 10.1128/aac.00056-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Y, Li X, Yang C, Tai S, Zhang X, Liu G. 2013. UPLC-MS-MS method for simultaneous determination of caffeine, tolbutamide, metoprolol, and dapsone in rat plasma and its application to cytochrome P450 activity study in rats. J Chromatogr Sci 51:26–32. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bms100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.