ABSTRACT

Quorum sensing is a type of cell–cell communication that modulates various biological activities of bacteria. Previous studies indicate that quorum sensing contributes to the evolution of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, but the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. In this study, we grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the presence of sub-lethal concentrations of ciprofloxacin, resulting in a large increase in ciprofloxacin minimal inhibitory concentration. We discovered that quorum sensing-mediated phenazine biosynthesis was significantly enhanced in the resistant isolates, where the quinolone circuit was the predominant contributor to this phenomenon. We found that production of pyocyanin changed carbon flux and showed that the effect can be partially inhibited by the addition of pyruvate to cultures. This study illustrates the role of quorum sensing-mediated phenotypic resistance and suggests a strategy for its prevention.

KEYWORDS: antimicrobial resistance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, quorum sensing, pyocyanin

INTRODUCTION

With the wide use of antibiotics in clinical, agricultural, and industrial settings, many bacteria have developed antimicrobial resistance rapidly over the past several decades. It has been estimated that antimicrobial resistance currently causes 700,000 deaths per year, and it will cause a 2%–3.5% reduction in Gross Domestic Product by 2050 (1). Therefore, the World Health Organization has declared antimicrobial resistance to be an important threat to human health and ecological safety (2).

The Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that often infects people with chronic wounds, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3). Recent years have witnessed an increasing prevalence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) P. aeruginosa, which accounts for up to one-third of P. aeruginosa infections. According to hospital data, MDR P. aeruginosa is the cause of 13% of severe healthcare-associated infections. The key priority for combatting P. aeruginosa resistance is to understand its mechanisms.

The well-described mechanisms of bacterial resistance include decreased outer membrane permeability, increased efflux of antibiotics, gain of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, mutations that resist the effect of antibiotics, acquisition of resistance genes, and biofilms that physically protect cells from antibiotic killing (4). Most studies of antibiotic resistance have been on genetic mechanisms of resistance, although there are studies describing other means by which bacteria become antibiotic-resistant, including a handful of links between P. aeruginosa quorum sensing and antibiotic resistance (5), but the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

P. aeruginosa engages in a cell-cell signaling system known as quorum sensing (QS) to coordinate group behaviors (6). P. aeruginosa has several intertwined QS circuits that together regulate the transcription of hundreds of genes (7). Two key circuits in P. aeruginosa respond to acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signals. In one, the signal synthase LasI generates the signal N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC12-HSL), the signal for LasR. Signal-bound LasR activates dozens of genes, including the one encoding another AHL receptor, RhlR, which binds to the signal N-butanoyl-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL), produced by the synthase RhlI. There is a third complete QS system called the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) system, which uses quinolone signals and interacts with RhlR QS (7). Together, these three major circuits regulate up to 10% of genes in P. aeruginosa (7, 8), regulating crucial biological activities such as production of shared “public goods” and virulence functions (9).

We are interested in how QS might contribute to antibiotic resistance in bacteria. In this study, we conducted an experimental evolution by passaging P. aeruginosa PAO1 in the presence of a sub-lethal concentration of ciprofloxacin (CIP). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of the evolved strains revealed the upregulation of QS and phenazine biosynthesis. The deletion of QS genes, pyocyanin synthesis genes, and a subsequent experimental evolution showed that the QS-regulated pyocyanin affects the antibiotic resistance of PAO1. By cross-comparing the resistance caused by pyocyanin and mutagenesis, we concluded that resistance caused by pyocyanin was critical to ciprofloxacin resistance of PAO1. Further experiments suggested that pyocyanin decreased the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) to resist high concentrations of antibiotics. Finally, we showed that pyruvate effectively delayed resistance evolution by reactivating bacteria carbon metabolism.

RESULTS

Bacterial quorum sensing contributes to antibiotic resistance evolution

Fluoroquinolones are the main class of antibiotics that are sufficient to treat P. aeruginosa. Among the fluoroquinolones, ciprofloxacin has the highest anti-pseudomonal activity (10). Concerningly, sub-lethal ciprofloxacin concentrations have been described to be frequent in various environmental settings (11). Therefore, we developed an interest into whether P. aeruginosa could evolve resistance to ciprofloxacin in the presence of sub-lethal ciprofloxacin concentrations.

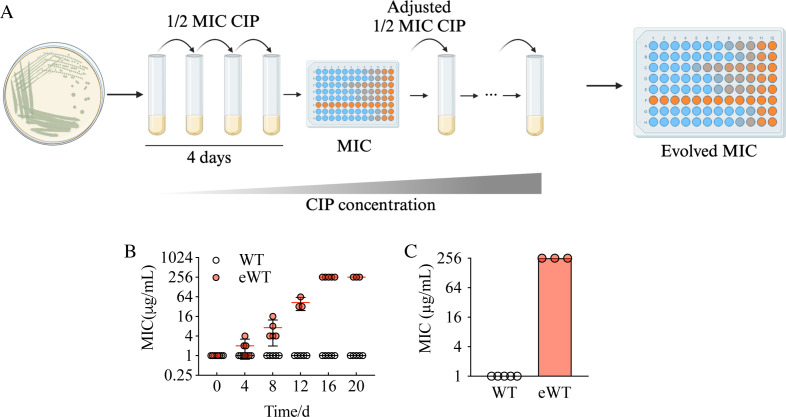

We conducted an evolution experiment with P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 grown in the presence of 0.5 μg/mL of ciprofloxacin, which is one-half of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Cultures were passaged daily, and to maintain a certain level of selective pressure, we maintained the concentration of ciprofloxacin at one-half of the current MIC, adjusting for increasing resistance throughout the experiment (Fig. 1A), a method inspired by Toprak et al. (12, 13). We measured the MIC of the evolving population to ciprofloxacin at 4-day intervals. By day 20 of the passage, the MIC increased to 256 μg/mL (Fig. 1C) from the initial 1 μg/mL. In cells grown in the absence of ciprofloxacin, there was no change in MIC (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig 1.

P. aeruginosa evolved a high level of ciprofloxacin resistance after experimental evolution. (A) The colonies were randomly selected from lysogen broth agar and grown in shaking test tubes. The suspension was transferred to a fresh tube every 24 h with 1/2 MIC of ciprofloxacin. The MIC was measured every 4 days, and the concentration of ciprofloxacin was adjusted accordingly. The experiment proceeded for 20 days, and the same procedure without added ciprofloxacin was used as a control. (B) The MIC of all lineages. WT represents the group cultured without ciprofloxacin. eWT represents the group cultured with ciprofloxacin. (C) The MIC of WT and eWT at day 20. MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

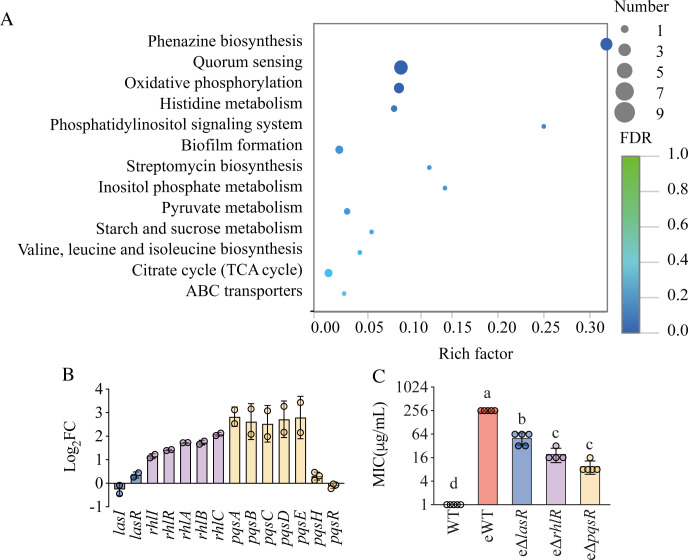

To determine if there was a role for QS in the evolution of ciprofloxacin resistance, we compared the transcriptome of evolved strains (eWT) to the parent PAO1. Using the edgeR statistical package (14) and a fold-change cutoff of 2, we found 1,268 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), of which 978 were upregulated, and 290 were downregulated. The top three enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (Fig. 2A) were for phenazine biosynthesis, QS, and oxidative phosphorylation. Among the genes encoding QS regulators, the expression of lasR increased by less than twofold, and the expression of lasI did not change (Fig. 2B). The genes of the RhlI/R circuit significantly increased in expression, and most genes of the PQS system increased approximately fivefold (Fig. 2B). These results were consistent with a prior report that QS was upregulated in resistant strains after sublethal ampicillin exposure (5). The increase in QS expression in the present study implied that QS may contribute to the resistance evolution of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin.

Fig 2.

Bacterial quorum sensing is responsible for antibiotic resistance evolution. (A) Plot of KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs (eWT vs WT). The x-axis shows the rich factor, defined as the number of DEG enriched in the pathway/number of all genes in the background gene set. The y-axis represents the enriched pathways. The color of the bubbles represents the false discovery rate (FDR). (B) The expression of QS-related genes of eWT compared with WT measured by RNA-seq. (C) The MIC of evolved QS-deficient strains after 20 days of sub-lethal ciprofloxacin exposure. Data are mean ± SD. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). eWT, evolved WT.

To test the role of QS in the evolution of antibiotic resistance, we knocked out the QS receptor genes independently and performed the same evolution experiments as described above. We reasoned that if QS was one of the drivers of resistance evolution, the evolved QS-deficient strains would exhibit less resistance to ciprofloxacin. In fact, deletion of lasR, rhlR, or pqsR resulted in dramatically lower MICs than PAO1 (Fig. 2C), with the pqsR deletion mutant exhibiting an MIC of only 8 μg/mL. We concluded that the PQS circuitry contributed most to the resistance.

QS-regulated pyocyanin contributes to bacterial resistance evolution

The result that PQS was the most important QS circuit for resistance development in the conditions of our experiments intrigued us because of the observation that pyocyanin production was also upregulated in the experiment. Pyocyanin is an important virulence factor of P. aeruginosa that causes inflammation and free radical damage (15). The main regulator of pyocyanin production is QS (7, 16). The LasI/R, RhlI/R, and PQS circuits all modulate the biosynthesis of pyocyanin and other phenazines (7, 16, 17), but PQS and RhlI/R are more important than LasI/R in regulating phenazine production (17). The upregulation of QS results in the overproduction of pyocyanin of evolved strains during experimental evolution, which was consistent with our observation.

Evaluating the contribution of QS to antimicrobial resistance is important as it offers the potential to mitigate antibiotic resistance using small molecules that might influence resistance. Previous studies provided several ways to inhibit resistance by modulating QS. These include the application of QS inhibitors such as acylase I (5), and the combination of QS inhibitors and antibiotics (18–20). However, the QS inhibitors are generally expensive and have to be dosed regularly, and disrupting the whole QS system could have unexpected off-target results. Therefore, the study of QS-regulated resistance mechanism is urgently needed.

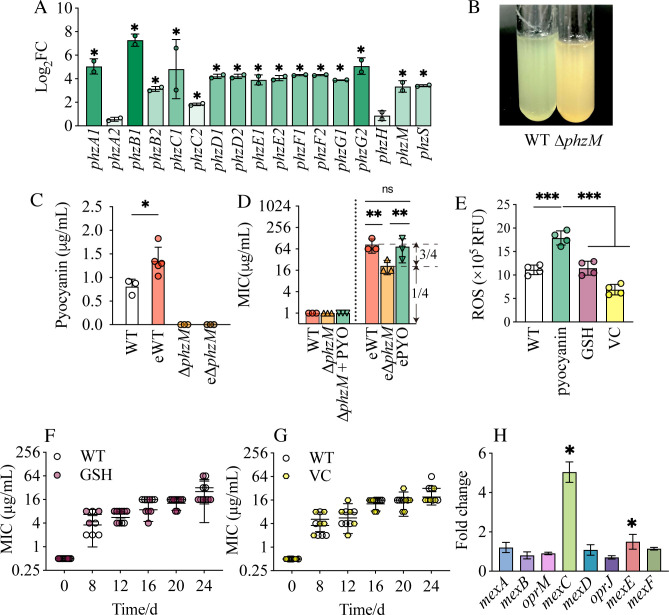

We noticed that phenazine production was also significantly upregulated (Fig. 2A) and controlled by QS (7, 16, 17). Pyocyanin is the most important phenazine in P. aeruginosa. Pyocyanin production is encoded by two loci, phzA1B1C1D1E1F1G1 (phz1) and phzA2B2C2D2E2F2G2 (phz2) (21). Both phz1 and phz2 code for proteins that produce phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA). Two other genes, phzM and phzS, code for a phenazine-specific methyltransferase and flavin-containing monooxygenase, respectively, and convert PCA to pyocyanin (21). In our RNA-seq analysis, we found that the 15 out of 17 genes of the phenazine biosynthesis pathway were significantly upregulated in evolved strains (Fig. 2A and 3A). phzB1 increased by 160-fold, and phzA1 increased by 35-fold compared to the wild type. The apparent and dramatic differences in phz1 and phz2 likely reflect an artifact of alignment of the RNA-seq pipeline as these operons are virtually identical in sequence. To address this issue, we re-analyzed the expression of genes within the operon by qRT-PCR (Fig. S1). This analysis showed no appreciable expression difference between the various genes of the operons. Expression of the other genes in the locus increased approximately 15-fold compared to the wild type. This finding was consistent with the increased level of pyocyanin, more than 1.35 µg/mL, in evolved resistant strains (Fig. 3C), which was significantly higher than that of the WT strains.

Fig 3.

QS-regulated pyocyanin contributes to bacterial resistance evolution. (A) Fold change of DEGs included in the phenazine biosynthesis pathway. Significant upregulated genes (compared to WT) are noted. (B) Pyocyanin production in WT (left) and ∆phzM (right) cultures. (C) The production of pyocyanin in WT and ∆phzM before and after evolution. (D) The MIC of WT, ∆phzM, and ∆phzM complemented with pyocyanin (PYO) before and after evolution. (E) The effect of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavengers glutathione (GSH) and vitamin C (VC) on intracellular ROS content. (F–G) MIC during a 20-day experimental evolution of PAO1 treated with GSH (F) and VC (G). (H) The expression of efflux pumps in eWT compared to that in the parent strain, analyzed using RNA-seq data. Data are mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. eWT, evolved WT; e∆phzM, evolved ∆phzM; ePYO, evolved ∆phzM complemented with pyocyanin; GSH, glutathione; VC, vitamin C.

We speculated that the QS-regulated pyocyanin may have an important role in the resistance to ciprofloxacin of evolved PAO1. To test this idea, we constructed a pyocyanin-deficient strain, ΔphzM. The deletion of phzM results in an inability to convert PCA to pyocyanin, and we confirmed that ΔphzM could not produce pyocyanin (Fig. 3B and C). We then repeated our experimental evolution again, this time including the ΔphzM strain. We hypothesized that if pyocyanin contributes to the emergence of resistance, a slower pace of resistance development would be observed in ΔphzM. In fact, there was a substantial difference between the MIC of evolved ∆phzM (e∆phzM) and eWT (Fig. 3D). The MIC of e∆phzM was approximately one-fourth of eWT (Fig. 3D). We then complemented the ∆phzM strain with exogenous pyocyanin and found that the MIC of evolved ∆phzM with pyocyanin (ePYO) was not different from that of eWT (Fig. 3D), providing support for our hypothesis that pyocyanin contributes to the evolution of ciprofloxacin resistance.

The resistance to ciprofloxacin conferred by pyocyanin is not by classic mechanisms

Pyocyanin is a virulence factor and a redox-active metabolite of P. aeruginosa (22) that may affect the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (23–26). Resistance to ciprofloxacin is primarily induced by mutagenesis in classic sites including gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE (27, 28). We isolated the evolved strains, including eWT, e∆phzM, and ePYO, and performed DNA sequencing. We detected mutations in gyrA in all isolates from all the strains and mutations in gyrB, parC, and parE in some isolates (Table S1). These mutations occurred in various combinations. Co-occurrence of mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE can cause an increase in MIC up to 64-fold (29–31).

To test whether the absence of pyocyanin would result in a different suite of mutations, we subsequently compared the mutations between e∆phzM and ePYO. As shown in Table S1, the mutations found are similar between e∆phzM and ePY, but their MIC differed (Fig. 3), indicating that the target site modification cannot explain the large difference in ciprofloxacin resistance between these two groups. Among the mutations detected, the parE I467S, parE S492T, and gyrB T510I have not been reported. Therefore, we constructed recombinant plasmids with these mutated genes (pAK1900-parEI467S, pAK1900-parES492T, and pAK1900-gyrBT510I) and transfected them into PAO1 by electroporation. The 90% inhibitory concentration of these strains was found to be higher than PAO1 and PAO1 containing pAK1900 only, but the differences were tiny, except that mutations in parE decreased the fitness of PAO1 (32) (Fig. S2). We concluded that these mutations do not account for all of the observed increase in resistance.

ROS production can cause mutations in other genes, which can also cause resistance. If so, the addition of ROS scavengers to cultures would inhibit resistance evolution. We selected two common ROS scavengers, glutathione and vitamin C, to test this hypothesis. When added to WT, both glutathione and vitamin C reduced ROS significantly (Fig. 3E). However, when we added these two scavengers separately to PAO1 cultures to perform experimental resistance, no differences in the ciprofloxacin MIC were found in any of the cultures (Fig. 3F and G). We concluded that the contribution of ROS to mutagenesis was not essential in promoting the evolution of resistance to ciprofloxacin.

Next, to test whether the expression of efflux pumps was different in eWT compared to WT, we returned to our RNA-seq analysis to assess the mRNA level of the genes encoding MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexAB-OprM, which are common efflux pumps for ciprofloxacin transport (31). We did not observe a significant increase in the expression of mexA, mexB, oprM, mexD, oprJ, or mexF (Fig. 3H). However, the expression of mexC and mexE was significantly upregulated. We conducted qRT-PCR and found that none of the genes was significantly upregulated (Fig. S3). Furthermore, the efflux pumps MexEF-OprN and MexCD-OprJ require upregulation of all components for increased pump activity. However, because the expression of mexD, oprJ, mexF, and oprN was not significantly different (Fig. 3H; Fig. S3), we concluded that the efflux pumps were not significantly upregulated and, therefore, unlikely to contribute to the increased resistance. Therefore, mutagenesis, ROS production, or overexpression of efflux pumps were not the crucial mechanisms by which pyocyanin was responsible for the increased resistance to ciprofloxacin.

Pyocyanin affects carbon metabolism to increase resistance

To investigate how pyocyanin affects the resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin, we compared the transcriptome of e∆phzM and eWT using the same statistical approach as before. There were 249 DEGs, and the top three enriched KEGG pathways were the citrate cycle (TCA cycle), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and the HIF-1 signaling pathway (Fig. 4A). These three KEGG pathways are related to the carbon metabolism of P. aeruginosa, so we focused on the expression of carbon metabolism-related genes. We found that PA3416 and PA3417 exhibited a threefold higher expression in e∆phzM than in eWT (Fig. 4B). PA3416 and PA3417 encode the E1 component of the PDH complex, which works together with dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (E2) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3) to catalyze pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, CO2, and NADH (H+) (33). Acetyl-CoA then enters the citrate cycle, yielding ATP to provide energy for biochemical processes.

Fig 4.

Pyocyanin affects carbon metabolism to increase the ciprofloxacin resistance. (A) KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs in e∆phzM compared with eWT. (B) Relative expression of PA3416 (left, coding for beta chain of E1 PDH) and PA3417 (right, coding for alpha chain of E1 PDH) in eWT and e∆phzM. (C–E) The PDH activity (C), ATP production (D), and the percentage of antibiotic-resistant individuals (E) of evolved strains. (F–H) The PDH activity (F), ATP production (G), and the percentage of antibiotic-resistant individuals (H) of PAO1 treated with different concentrations of pyocyanin. The antibiotic-resistant individuals were defined as a group of bacteria that survived when exposed to a bactericidal drug concentration (5 × MIC). (I) The percentage of antibiotic-resistant individuals during the whole evolution. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means among groups. Data are mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). eWT, evolved WT; e∆phzM, evolved ∆phzM; ePYO, evolved ∆phzM complemented with pyocyanin.

If pyocyanin decreases carbon metabolism, then the PDH activity and ATP production will be higher in e∆phzM than in ePYO. We found that e∆phzM produced higher PDH activity and more ATP than ePYO (Fig. 4C and D). Decreased metabolic rates can reduce susceptibility to antibiotics (as the targets are less abundant, less active, or both) (34, 35). We defined the bacteria that survived when exposed to a bactericidal drug concentration (5 × MIC) as resistant individuals. We tested the percentage of resistant individuals in the following groups: WT, eWT, e∆phzM, and ePYO. In the WT PAO1, only 0.0023% survived treatment with 5 × MIC of ciprofloxacin, significantly lower than that in eWT, e∆phzM, and ePYO (Fig. 4E). Without pyocyanin, there were fewer resistance colonies in the e∆phzM population, matching well to low carbon metabolism but high resistance to antibiotics.

We next added 0, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 µM of pyocyanin into WT PAO1. The addition of pyocyanin decreased PDH activity and ATP production. Addition of 5 µM of pyocyanin significantly decreased PDH from ~17.2 to ~7.4 U/108 cells (Fig. 4F). Although the PDH activity did not decrease further with the additional increases of the pyocyanin concentration, 5, 10, 20, and 100 µM of pyocyanin significantly decreased PDH activity compared to the WT. Similarly, 5, 20, 50, and 100 µM of pyocyanin significantly decreased ATP from ~2.5 to 1.2–1.8 nmol/mL, but again, no dose-response effect was observed (Fig. 4G). Correspondingly, adding pyocyanin into WT PAO1 increased the percentage of resistant individuals from 0.09% to 5.9%, 12.0%, and 5.8% in groups treated with 50, 100, and 200 µM pyocyanin, respectively (Fig. 4H). We also tested the frequency of resistant individuals in eWT at days 4, 8, 16, and 20 and saw an increase over time in our experiment (Fig. 4I). Thus, we concluded that pyocyanin could inhibit carbon metabolism, which resulted in an increase in the number of antibiotic-resistant cells in the bacterial population.

Pyruvate hinders resistance evolution of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin

If pyocyanin did increase resistance evolution by favoring a metabolically inactive state, we reasoned that rescuing bacterium from this relative inactivity conferred increased susceptibility to the antibiotics. Compared to QS inhibitors, pyruvate is a simpler potential treatment as it is more accessible and affordable. Pyruvate can influence metabolism in two ways. Pyruvate is the end product of glycolysis, which can be converted to acetyl-CoA and enters the citric acid cycle (36). Pyruvate can also inhibit the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, which inactivates PDH (37). The addition of pyruvate should keep the bacteria in a metabolically active state. Once the metabolism is altered, it can substantially affect antibiotic resistance (34, 35).

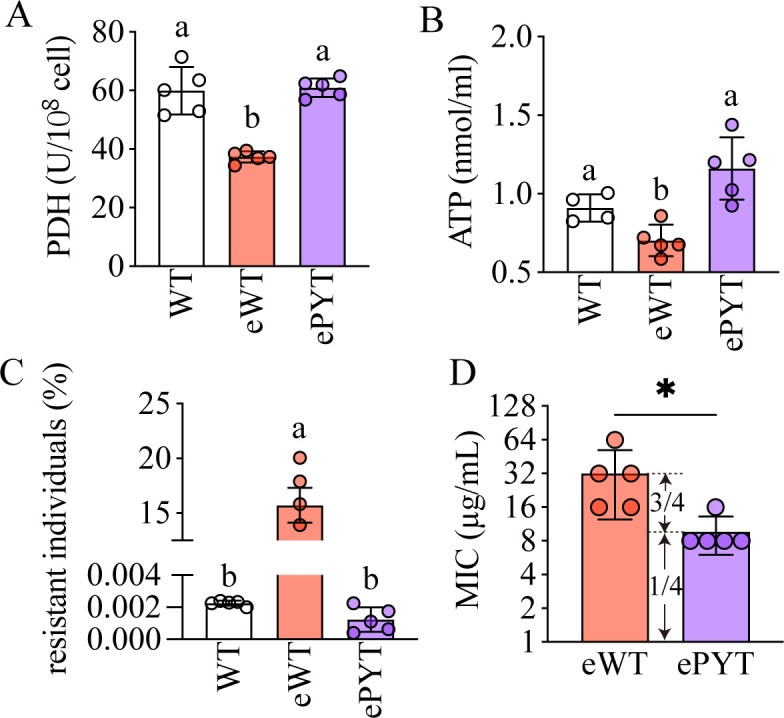

Thus, our strategy was to supplement cultures with pyruvate, the substrate of PDH. We performed another experimental evolution using either WT or WT supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL of pyruvate (ePYT). As we anticipated, the PDH activity in eWT (37.3 U/108 cells) was significantly lower than that in ePYT (61.0 U/108 cells) (Fig. 5A). We also measured the production of ATP and found it significantly higher in ePYT than in eWT (1.2 ± 0.2 vs 0.7 ± 0.1 nmol/mL) (Fig. 5B), all consistent with the data we observed in the ∆phzM background. As a result, there were significantly fewer individual bacteria in the ePYT population that were resistant to ciprofloxacin: 0.0011% in ePYT, similar to the level of WT (0.0023%), and significantly lower than that of eWT (15.90%) (Fig. 5C). After 24 days, the MIC of eWT increased to 32 µg/mL, while the MIC of bacteria grown in the presence of pyruvate (ePYT) was only 8 µg/mL, one-fourth of the eWT (Fig. 5D), which is consistent with the decrease in MIC after phzM depletion (Fig. 3D). Therefore, pyruvate hindered the resistance to ciprofloxacin induced by pyocyanin. Overall, inhibition of metabolism leads to resistance, and activation of metabolism results in susceptibility.

Fig 5.

Pyruvate activates carbon metabolism and inhibits resistance evolution. (A–C) The PDH activity (A), ATP production (B), and percentage of antibiotic-resistant individuals (C) in WT, eWT, and ePYT. (D) The MICs of evolved WT treated with or without pyruvate in a separate experiment from the data presented in Fig. 1. eWT, evolved WT; ePYT. evolved WT treated with pyruvate. All experiments had at least three replicates. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means among groups. Data are means ± SD; *P < 0.05. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

To date, studies of antimicrobial resistance have been mostly focused on resistance caused by genetic changes, with non-inherited resistance, or phenotypic resistance, understudied. In this study, we show that phenotypic resistance is an important component of antimicrobial resistance and the evolution of resistance. When treated with sub-lethal ciprofloxacin for 20 days, the MIC of P. aeruginosa increased significantly (Fig. 2), but the target site mutations only accounted for one-quarter of the increase. We found that this phenomenon was attributable to the production of pyocyanin. We showed that a pyocyanin production-deficient strain, ∆phzM, had a lower MIC than the wild type when grown in the presence of sub-lethal ciprofloxacin and that the addition of exogenous pyocyanin increased resistance (Fig. 3). This change in resistance occurred despite similar gene mutations in both groups. We also showed that the addition of pyocyanin to WT PAO1 resulted in an increased percentage of bacteria resistance to high concentrations (5×) of ciprofloxacin (Fig. 4), consistent with our hypothesis.

Previous studies have demonstrated a role for QS in antimicrobial resistance and resistance evolution, but the mechanisms remain unclear. There are some hints: QS has been shown to affect antibiotic resistance determinants (38). Mutations of LasR can enhance susceptibility to some antibiotics, such as tobramycin (39). The addition of C4-HSL, the RhlR signal, increases the expression of the efflux pump MexAB-oprM (40), increasing the tolerance of bacteria to certain antibiotics. The combination of antibiotics and QS inhibitors (QSI) can change bacterial susceptibility to certain antibiotics (18, 19).

Our prior work has explored the contribution of the RhlI/R circuit to the emergence of resistance in P. aeruginosa and showed that the inhibition of QS increases the susceptibility of bacteria to antibiotics (5). In the present study, we have expanded to study the contribution of the PQS system to antibiotic resistance. We showed that lasR-, rhlR-, and pqsR-deficient strains slowed the evolution of antimicrobial resistance compared to the WT, and the MIC of a pqsR-deficient strain was the lowest (Fig. 2C), indicating the important role of this circuit in the emergence of resistance evolution. This finding provides potential new targets and perspectives for future studies.

The methods that have been used to prevent resistance evolution are generally of two types: (i) using antibiotics with resistance-inhibiting compounds and (ii) using selection inversion between antibiotic combinations, making bacteria susceptible to one of the two drugs (37). Fast switching between homogenous antibiotics also results in increased killing of P. aeruginosa (41). However, these methods can increase the use of antibiotics, and the long-term consequences are unpredictable, so more precise methods are needed.

We discovered, by exploring the possible mechanisms of pyocyanin, that pyruvate addition could inhibit the emergence of resistance to ciprofloxacin. Compared to QS inhibitors, pyruvate is a simpler potential treatment as it is more accessible and affordable. Some studies found that metabolic mutations caused the lowered basal respiration to prevent metabolic toxicity, therefore increasing the resistance to antibiotics (42). Other studies showed that glucose negatively regulates the cAMP/CRP complex to inhibit the change from tolerance to resistance during evolution (43). Others reported that decreasing ATP levels promoted the survival of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus when exposed to antibiotics due to the decreased activity of ATP-dependent antibiotic targets (44, 45). In studies focusing on the resistance to aminoglycosides, carbon metabolites, such as glucose, mannitol, fructose, arabinose, ribose, fumarate, and gluconate, can enhance the killing of antibiotic-resistant cells (46–49). These compounds induced the proton-motive force, thus increasing the uptake of aminoglycosides (46, 47, 50, 51). They also increased the susceptibility of the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus to tobramycin through a mechanism that relates to the phosphotransferase system (52). Our work provides an easy and accessible method to hinder resistance evolution when P. aeruginosa is exposed to sub-lethal concentrations of ciprofloxacin, for example, in wastewater and soils, where pyruvate can be easily delivered. When P. aeruginosa exists as a biofilm in infectious contexts, pyruvate could also be applied in conjunction with biofilm-inhibiting drugs.

Our work demonstrated that pyocyanin promotes resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin. Our study is complemented by the work by Meirelles et al., who discovered using a Tn-seq approach that genes that confer self-tolerance to pyocyanin overlap with those that confer resistance to ciprofloxacin (23).

Although the mutations that were observed in the WT and ∆phzM strains in our studies were similar, it is possible that the order in which they occurred was different—that there is an “evolutionary landscape” (53) created by the presence of pyocyanin that results in a different sequence of beneficial mutations. It is additionally possible that the order of mutations matters for the overall fitness of the bacteria and that the new mutations we identified (Table S1) may have unexpected effects in combination with other mutations (54). It is also quite likely that the higher number of resistant individuals in the presence of pyocyanin leads to a larger pool from which beneficial mutations can be selected. Our study was not designed to address these possibilities, but they are interesting avenues for future research.

Altogether, this study demonstrates the contribution of the PQS system to the evolution of ciprofloxacin resistance by P. aeruginosa. We show that PQS-regulated pyocyanin affects resistance by altering carbon metabolism and that exogenous pyruvate can hinder resistance evolution, providing new avenues to exploring resistance evolution and the application of compounds that might impair the development of resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

Five P. aeruginosa strains were used for this study: the wild-type PAO1 (WT), ΔphzM, ΔlasR, ΔrhlR and ΔpqsR. Knockout strains were generated by homologous recombination. In detail, DNA fragments flanking ΔphzM, ΔlasR, ΔrhlR and ΔpqsR were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and confirmed by sequencing. The DNA fragments were cloned into pEXG2. The competent Escherichia coli S17 was the receptor of pEXG2 derivative. Transconjugants were selected step by step by Vogel–Bonner minimal medium plate containing 30 µg/mL of gentamicin, non-salt lysogeny broth (LB) plate with 15% (wt/vol) sucrose, PIA plate, and LB plate containing 50 µg/mL of gentamicin. Knockout of genes was confirmed by PCR and sequencing (TsingkeBiotechnology, Beijing, CN).

Experimental evolution

Colonies of P. aeruginosa strains were randomly picked from LB agar and grown in 4 mL of LB medium at 37°C, shaking at 250 rpm for 12 h. The suspension was transferred to a fresh tube of LB with 0.5 μg/mL of ciprofloxacin to start the experiment. The initial optical density at 600 (OD600) was 0.005. The culture was transferred to fresh LB broth with a setting concentration of ciprofloxacin every 24 h. The concentration of ciprofloxacin was changed every 4 days, retaining 1/2 MIC to provide enduring stress to the strains. The process was repeated until the MIC was stable. The same evolution of WT lineages cultured without ciprofloxacin was set as controls. In the evolution of ePYO, 2mg/mL of pyocyanin was added to analyze the role of pyocyanin. The evolution of WT treated by either 2 mg/mL of glutathione or 0.5 mg/mL of pyruvate was conducted to find a reductant to relieve resistance evolution.

MIC measurement

The MIC was detected according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. Briefly, the cultures were grown overnight in LB broth at 37°C, 250 rpm, then diluted to a density of 106 cells/mL. Bacterial suspension in LB was seeded to a 96-well plate at 100 µL per well, and the twofold-diluted ciprofloxacin was also added into the wells, with final concentrations of 1,024, 512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, and 0 μg/mL of ciprofloxacin in the culture. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. SpectraMax i3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used to measure bacterial growth by the optical density at 600 nm. The concentration that inhibited bacterial growth by 95% was considered as the MIC. The initial MICs of WT and ΔphzM to ciprofloxacin were 1 μg/mL.

DNA sequencing

We randomly selected 25 isolates from eWT, 10 from eΔphzM, and 10 from ePYO. Three colonies from WT agar plate were picked as the control. Genomic DNA was extracted by TIANamp Bacteria DNA kit (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, CN). The gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes were amplified by PCR using Eppendorf MastercyclerNexus Thermal Cycler (Fisher Scientific, New Hampshire, USA). Primer synthesis and sanger sequencing were performed by Tsingke Biotech (Beijing, CN).

Transcriptome analysis

Colonies were randomly selected from WT agar, eΔphzM agar, and eWT agar containing 128 μg/mL ciprofloxacin. These colonies were cultured to the OD600 of 2.0 and centrifuged to collect cells. RNA was extracted using TruSeq RNA sample preparation Kit (TransGen, Beijing, CN). The transcriptome library was constructed by TruSeqTM Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit (TransGen, Beijing, CN). Samples were sequenced using Illumina Hiseq X through double-ended sequencing (Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology, Shanghai, CN). The sequences either shorter than 25 bp in length or containing 10% N were cut to obtain high-quality clean data. High-quality reads in every sample were mapped to the reference genome (GCF 000006765.1) with Bowti2. The analysis for RNA sequencing was performed using the online Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). FPKM method was used to calculate the expression level. Differential expression analysis was performed using edgeR package, and the P-values were adjusted using Bonferroni and false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Genes with a P-value < 0.05 was defined as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). KOBAS 2.0 was used to identify enriched KEGG pathways (P-value < 0.05) using Fisher’s exact test.

Pyocyanin measurement

Pyocyanin concentrations were measured using the method of Kurachi (55). Briefly, cultures were grown at 37°C, 250 rpm to stable phase, then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatants were collected and mixed with an equal volume of chloroform (vol/vol = 1:1) and vortexed. After centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000 rpm, 1 mL of the blue underlayer was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 1 mL of 0.2 M HCl. The absorbance at 520 nm of the mixture was measured by SpectraMax i3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). The concentration of pyocyanin was 12.8 times the A520 (mg/L).

ROS measurement

The intracellular ROS was measured by the Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, CN). Pyocyanin, glutathione, and vitamin C were added into PAO1 at the early stationary phase (OD600 = 1.0). The culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 3 min to collect cells. Then, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate was added into the sample with a final concentration of 10 mmol/L. Cells were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 min, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. A SpectraMax i3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) was used to measure the fluorescence with an excitation wavelength at 488 nm and a detection wavelength at 525 nm.

PDH measurement

One milliliter of overnight culture was collected, and cell counts were calculated by OD600. The culture was mixed with reagents for ultrasonication. The sample was centrifuged at 11,000 g, 4°C for 10 min. The supernatants were collected for the measurement of PDH. The PDH activity was measured by reducing 2,6-dichlorophenol indiophenol according to the instructions (BC0385, Solarbio Lifesciences, Beijing, CN). Of the supernatant, 50 µL was reacted with 900 µL of the working solution. The optical density of the mixture was measured at 605 nm immediately and after 1 min of reaction. ΔA was defined as the difference value of the optical density before and after 1 min of reaction. One unit of PDH activity was determined as 1 g of cells producing 1 nmol of 2,6-dichlorophenol indiophenol every 1 min.

ATP measurement

An ATP assay kit (S0027, Beyotime, Shanghai, CN) was used to measure the intracellular ATP levels. Of the overnight culture, 1 mL was collected and added with 200 µL of lysis buffer, then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min to collect the supernatant. Supernatant, 20 µL, was added with 100 µL of working solution. A SpectraMax i3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) was used to measure the luminescence.

Enumeration of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Bacterial strains were grown to the logarithmic growth phase at 37°C and 250 rpm. One milliliter of the culture was serially diluted and plated on agar, growing at 37°C for 10–12 h to determine the initial CFU. The rest of the culture was challenged with 5 × MIC of ciprofloxacin for 12 h. The culture was washed with PBS two to three times to reduce ciprofloxacin concentration. Then, the cell was centrifuged, resuspended in 100 µL of PBS and serially diluted in a 96-well plate. The diluted cells were plated on the LB agar and incubated for 10–12 h at 37°C. The number of colonies was counted on both plates, and the percentage of antibiotic-resistant cells was calculated as (CFUafter/CFUbefore) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 9.0 (CA, USA). Statistical significance was analyzed using Student’s t-test when comparing two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used when comparing more than two groups. Data were means ± SD as indicated in the figure legend. P < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22122607, 22076167, U21A20292, 82370006, 82241046, and 82200052) and the Qianjiang Distinguished Scholar Program from Hangzhou City.

L.X. and Y.L. contributed equally to this work. L.X. contributed to the following: investigation, methodology, data analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing (leading), writing-revision (leading), and visualization. Y.L. contributed to the following: investigation, methodology, data analysis, and writing-original draft. Y.W. contributed to the following: formal analysis and methodology, writing-revision (supporting). H.Z. contributed to the following: writing-revision (supporting). A.A.D. contributed to the following: supervision and writing-revision (leading). F.X. contributed to the following: supervision, funding acquisition, and writing-revision (supporting). M.W. contributed to the following: project administration, funding acquisition, resources, conceptualization, writing-revision (leading), and supervision.

AFTER EPUB

[This article was published on 25 March 2024 with authors Meizhen Wang and Feng Xu listed in the incorrect order in the byline. The byline was corrected in the current version, posted on 15 April 2024.]

Contributor Information

Meizhen Wang, Email: wmz@zjgsu.edu.cn.

Feng Xu, Email: xufeng99@zju.edu.cn.

Laurent Poirel, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The filtered clean data were uploaded to the NCBI SRA database under accession number PRJNA1081479.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00118-24.

Table S1; Fig. S1 to S3.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. O’Neil J. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. In Rev Antimicrob resist. Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antimicrobial resistance. Available from: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

- 3. Eklöf J, Sørensen R, Ingebrigtsen TS, Sivapalan P, Achir I, Boel JB, Bangsborg J, Ostergaard C, Dessau RB, Jensen US, Browatzki A, Lapperre TS, Janner J, Weinreich UM, Armbruster K, Wilcke T, Seersholm N, Jensen JUS. 2020. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and risk of death and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an observational cohort study of 22053 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 26:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin TJ, Cheng Z. 2019. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv 37:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li Y, Xia L, Chen J, Lian Y, Dandekar AA, Xu F, Wang M. 2021. Resistance elicited by sub-lethal concentrations of ampicillin is partially mediated by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Int 156:106619. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. 2012. Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:11. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee J, Zhang L. 2015. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 6:26–41. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0100-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. 2003. Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol 185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Whiteley M, Diggle SP, Greenberg EP. 2017. Progress in and promise of bacterial quorum sensing research. Nature 551:313–320. doi: 10.1038/nature24624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walker RC, Wright AJ. 1991. The fluoroquinolones. Mayo Clin Proc 66:1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62477-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han J, Xu Y, Xu D, Niu Y, Li L, Li F, Li Z, Wang H. 2023. Mechanism of downward migration of quinolone antibiotics in antibiotics polluted natural soil replenishment water and its effect on soil microorganisms. Environ Res 218:115032. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.115032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toprak E, Veres A, Michel JB, Chait R, Hartl DL, Kishony R. 2011. Evolutionary paths to antibiotic resistance under dynamically sustained drug selection. Nat Genet 44:101–105. doi: 10.1038/ng.1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zlamal JE, Leyn SA, Iyer M, Elane ML, Wong NA, Wamsley JW, Vercruysse M, Garcia-Alcalde F, Osterman AL. 2021. Shared and unique evolutionary trajectories to ciprofloxacin resistance in Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. mBio 12:e0098721. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00987-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hall S, McDermott C, Anoopkumar-Dukie S, McFarland AJ, Forbes A, Perkins AV, Davey AK, Chess-Williams R, Kiefel MJ, Arora D, Grant GD. 2016. Cellular effects of pyocyanin, a secreted virulence factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Toxins (Basel) 8:236. doi: 10.3390/toxins8080236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lau GW, Hassett DJ, Ran H, Kong F. 2004. The role of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Trends Mol Med 10:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin J, Cheng J, Wang Y, Shen X. 2018. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS): not just for quorum sensing anymore. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:230. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sikdar R, Elias MH. 2022. Evidence for complex interplay between quorum sensing and antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0126922. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01269-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brackman G, Cos P, Maes L, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. 2011. Quorum sensing inhibitors increase the susceptibility of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2655–2661. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00045-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brackman G, Breyne K, De Rycke R, Vermote A, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Meyer E, Van Calenbergh S, Coenye T. 2016. The quorum sensing inhibitor hamamelitannin increases antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms by affecting peptidoglycan biosynthesis and eDNA release. Sci Rep 6:20321. doi: 10.1038/srep20321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Delaney SM, Soule MJ, Phillips G, Thomashow LS. 2001. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 183:6454–6465. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6454-6465.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jayaseelan S, Ramaswamy D, Dharmaraj S. 2014. Pyocyanin: production, applications, challenges and new insights. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30:1159–1168. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1552-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meirelles LA, Perry EK, Bergkessel M, Newman DK. 2021. Bacterial defenses against a natural antibiotic promote collateral resilience to clinical antibiotics. PLoS Biol 19:e3001093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dietrich LEP, Price-Whelan A, Petersen A, Whiteley M, Newman DK. 2006. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signaling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 61:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rada B, Gardina P, Myers TG, Leto TL. 2011. Reactive oxygen species mediate inflammatory cytokine release and EGFR-dependent mucin secretion in airway epithelial cells exposed to Pseudomonas pyocyanin. Mucosal Immunol 4:158–171. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LEP, Newman DK. 2007. Pyocyanin alters redox homeostasis and carbon flux through central metabolic pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J Bacteriol 189:6372–6381. doi: 10.1128/JB.00505-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rehman A, Patrick WM, Lamont IL. 2019. Mechanisms of ciprofloxacin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new approaches to an old problem. J Med Microbiol 68:1–10. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruchmann S, Dötsch A, Nouri B, Chaberny IF, Häussler S. 2013. Quantitative contributions of target alteration and decreased drug accumulation to Pseudomonas aeruginosa fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1361–1368. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01581-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rehman A, Jeukens J, Levesque RC, Lamont IL. 2021. Gene-gene interactions dictate ciprofloxacin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and facilitate prediction of resistance phenotype from genome sequence data. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e0269620. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02696-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao L, Wang S, Li X, He X, Jian L. 2020. Development of in vitro resistance to fluoroquinolones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9:124. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00793-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cabrera R, Fernández-Barat L, Vázquez N, Alcaraz-Serrano V, Bueno-Freire L, Amaro R, López-Aladid R, Oscanoa P, Muñoz L, Vila J, Torres A. 2022. Resistance mechanisms and molecular epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with bronchiectasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 77:1600–1610. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkac084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rajer F, Sandegren L. 2022. The role of antibiotic resistance genes in the fitness cost of multiresistance plasmids. mBio 13:e0355221. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03552-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel MS, Nemeria NS, Furey W, Jordan F. 2014. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes: structure-based function and regulation. J Biol Chem 289:16615–16623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.563148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martínez JL, Rojo F. 2011. Metabolic regulation of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35:768–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zampieri M, Enke T, Chubukov V, Ricci V, Piddock L, Sauer U. 2017. Metabolic constraints on the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Mol Syst Biol 13:917. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arjunan P, Nemeria N, Brunskill A, Chandrasekhar K, Sax M, Yan Y, Jordan F, Guest JR, Furey W. 2002. Structure of the pyruvate dehydrogenase multienzyme complex E1 component from Escherichia coli at 1.85 A resolution. Biochemistry 41:5213–5221. doi: 10.1021/bi0118557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baym M, Stone LK, Kishony R. 2016. Multidrug evolutionary strategies to reverse antibiotic resistance. Science 351:aad3292. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hernando-Amado S, Sanz-García F, Martínez JL. 2019. Antibiotic resistance evolution is contingent on the quorum-sensing response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Biol Evol 36:2238–2251. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abisado-Duque RG, Townsend KA, Mckee BM, Woods K, Koirala P, Holder AJ, Craddock VD, Cabeen M, Chandler JR. 2023. An amino acid substitution in elongation factor EF-G1A alters the antibiotic susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasR-null mutants. J Bacteriol 205:e0011423. doi: 10.1128/jb.00114-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maseda H, Sawada I, Saito K, Uchiyama H, Nakae T, Nomura N. 2004. Enhancement of the mexAB-oprM efflux pump expression by a quorum-sensing autoinducer and its cancellation by a regulator, MexT, of the mexEF-oprN efflux pump operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1320–1328. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1320-1328.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Batra A, Roemhild R, Rousseau E, Franzenburg S, Niemann S, Schulenburg H. 2021. High potency of sequential therapy with only β-lactam antibiotics. Elife 10:e68876. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lopatkin AJ, Bening SC, Manson AL, Stokes JM, Kohanski MA, Badran AH, Earl AM, Cheney NJ, Yang JH, Collins JJ. 2021. Clinically relevant mutations in core metabolic genes confer antibiotic resistance. Science 371:eaba0862. doi: 10.1126/science.aba0862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang M, Su Y-B, Ye J-Z, Li H, Kuang S-F, Wu J-H, Li S-H, Peng X-X, Peng B. 2023. Ampicillin-controlled glucose metabolism manipulates the transition from tolerance to resistance in bacteria. Sci Adv 9:eade8582. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade8582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shan Y, Brown Gandt A, Rowe SE, Deisinger JP, Conlon BP, Lewis K. 2017. ATP-dependent persister formation in Escherichia coli. mBio 8:e02267-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02267-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Conlon BP, Rowe SE, Gandt AB, Nuxoll AS, Donegan NP, Zalis EA, Clair G, Adkins JN, Cheung AL, Lewis K. 2016. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat Microbiol 1:16051. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allison KR, Brynildsen MP, Collins JJ. 2011. Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 473:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barraud N, Buson A, Jarolimek W, Rice SA. 2013. Mannitol enhances antibiotic sensitivity of persister bacteria in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS One 8:e84220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Su Y, Peng B, Han Y, Li H, Peng X. 2015. Fructose restores susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Edwardsiella tarda to kanamycin. J Proteome Res 14:1612–1620. doi: 10.1021/pr501285f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koeva M, Gutu AD, Hebert W, Wager JD, Yonker LM, O’Toole GA, Ausubel FM, Moskowitz SM, Joseph-McCarthy D. 2017. An antipersister strategy for treatment of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00987-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00987-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peng B, Su YB, Li H, Han Y, Guo C, Tian YM, Peng XX. 2015. Exogenous alanine and/or glucose plus kanamycin kills antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Cell Metab 21:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meylan S, Porter CBM, Yang JH, Belenky P, Gutierrez A, Lobritz MA, Park J, Kim SH, Moskowitz SM, Collins JJ. 2017. Carbon sources tune antibiotic susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via tricarboxylic acid cycle control. Cell Chem Biol 24:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Prax M, Mechler L, Weidenmaier C, Bertram R. 2016. Glucose augments killing efficiency of daptomycin challenged Staphylococcus aureus persisters. PLoS One 11:e0150907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nahum JR, Godfrey-Smith P, Harding BN, Marcus JH, Carlson-Stevermer J, Kerr B. 2015. A tortoise–hare pattern seen in adapting structured and unstructured populations suggests a rugged fitness landscape in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:7530–7535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410631112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abisado RG, Kimbrough JH, McKee BM, Craddock VD, Smalley NE, Dandekar AA, Chandler JR. 2021. Tobramycin adaptation enhances policing of social cheaters in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e0002921. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00029-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kurachi M. 1958. Studies on the biosynthesis of pyocyanine. (II): isolation and determination of pyocyanine, Vol. 36, p 174–187. Bulletin of the Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1; Fig. S1 to S3.

Data Availability Statement

The filtered clean data were uploaded to the NCBI SRA database under accession number PRJNA1081479.