Abstract

Host response to pathogens recruits multiple tissues in part through conserved cell signaling pathways. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) like DBL-1 signaling pathway has a role in the response to infection in addition to other roles in development and postdevelopmental functions. In the regulation of body size, the DBL-1 pathway acts through cell autonomous signal activation in the epidermis (hypodermis). We have now elucidated the tissues that respond to DBL-1 signaling upon exposure to two bacterial pathogens. The receptors and Smad signal transducers for DBL-1 are expressed in pharyngeal muscle, intestine, and epidermis. We demonstrate that expression of receptor-regulated Smad (R-Smad) gene sma-3 in the pharynx is sufficient to improve the impaired survival phenotype of sma-3 mutants and that expression of sma-3 in the intestine has no effect when exposing worms to bacterial infection of the intestine. We also show that two antimicrobial peptide genes – abf-2 and cnc-2 – are regulated by DBL-1 signaling through R-Smad SMA-3 activity in the pharynx. Finally, we show that pharyngeal pumping activity is reduced in sma-3 mutants and that other pharynx-defective mutants also have reduced survival on a bacterial pathogen. Our results identify the pharynx as a tissue that responds to BMP signaling to coordinate a systemic response to bacterial pathogens.

Innate immunity is the first line of defense against pathogens. Conserved cell signaling pathways are known to be involved in host-pathogen response, but how they coordinate a systemic response is less well understood.

In the nematode C. elegans, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling is required for survival on pathogenic bacteria. Using transgenic strains, the authors identify a major role for a specific organ, the pharynx, in BMP-dependent survival.

These findings demonstrate that an organ can serve as a pathogen sensor to trigger multiple modes of response to bacterial pathogens, include a barrier response and regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression.

INTRODUCTION

Animals encounter a diverse range of microorganisms in their environments, many of which can pose a risk for infection. This exposure has resulted in the development of immune networks to protect the host from pathogenic threats. Innate immunity provides an immediate response to infection and functions through highly conserved mechanisms. In humans, innate immunity involves physical barriers such as the skin, recruitment of phagocytic cells, and the release of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Expression of these AMPs is regulated by a number of signaling pathways and these mechanisms are conserved across metazoan species (Medzhitov and Janeway, 1998; Hoffmann et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2002; Schulenburg et al., 2004; Millet and Ewbank, 2004; Irazoqui et al., 2008; Partridge et al., 2010; Pukkila-Worley and Ausubel, 2012; Kim and Ewbank, 2018).

The soil-dwelling nematode Caenorhabditis elegans naturally encounters many pathogens, thus necessitating a functioning immune system to provide adequate protection. Pathogen response can be divided into behavioral avoidance responses, innate immunity (including barrier functions and AMP expression), and immune tolerance (mitigating the effect of infection rather than reducing infection; Yamamoto and Savage-Dunn, 2023). The initial point of contact for pathogens can be the cuticle, intestine, uterus, or rectum (Kim and Ewbank, 2018). In addition, defects in pharyngeal function can cause increased susceptibility to ingested microbes (Labrousse et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2002). Although the animals lack an antibody-based acquired immunity, C. elegans has served as a useful organism in which to study many of the conserved signaling pathways that are involved in innate immunity and how they regulate an antimicrobial response (Kim et al., 2002; Schulenburg et al., 2004; Millet and Ewbank, 2004; Irazoqui et al., 2008; Partridge et al., 2010; Pukkila-Worley and Ausubel, 2012; Kim and Ewbank, 2018).

One pathway involved in the C. elegans immune response is the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-like DBL-1 signaling pathway (Mallo et al., 2002). BMPs are members of the large conserved Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β) family of secreted peptide growth factors (Massagué, 1998). Members of the TGF-β family play critical roles in adaptive and innate immunity (Chen and ten Dijke, 2016). In C. elegans, the DBL-1 pathway (Figure 1A) is initiated through the neuronally expressed ligand DBL-1 (Suzuki et al., 1999; Morita et al., 2002). The receptors DAF-4 and SMA-6 along with the signaling mediators SMA-2, SMA-3, and SMA-4 are endogenously expressed in the epidermis (also known as hypodermis in C. elegans), the intestine, and the pharynx (Savage et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1999; Inoue and Thomas, 2000; Savage-Dunn et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2001; Mallo et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). DBL-1 signaling plays a significant role in body size regulation, male tail development, mesodermal patterning, and lipid accumulation (Attisano and Wrana, 1996; Savage et al., 1996; Heldin et al., 1997; Derynck et al., 1998; Padgett et al., 1998; Whitman, 1998; Suzuki et al., 1999; Inoue and Thomas, 2000; Savage-Dunn et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2002; Gumienny and Savage-Dunn, 2018; Clark et al., 2018) in addition to its role in the C. elegans immune response (Mallo et al., 2002). This pathway has been well studied in the C. elegans response to the Gram-negative bacterium Serratia marcescens, where it has been demonstrated that mutation in dbl-1 results in increased susceptibility to infection (Mallo et al., 2002). Our interest in this study was to determine the way in which DBL-1 signaling plays a broader role in the immune response against bacterial pathogens and the mechanisms through which this specific function is carried out.

FIGURE 1:

DBL-1 Pathway R-Smad SMA-3 is required for survival on bacterial pathogen. (A) BMP signaling in C. elegans through the DBL-1 pathway. (B) Survival of sma-3(wk30) on S. marcescens. n values: Control (99), sma-3 (55). (C) Survival of sma-3(wk30) on P. luminescens. n values: Control (67), sma-3 (63). Survival analyses were repeated and results were consistent across trials. Statistical analysis was done using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test. *** P ≤ 0.001; **** P < 0.0001.

Here we show that DBL-1 signaling through the receptor-regulated R-Smad SMA-3 is required for protection against bacterial pathogen in C. elegans. We demonstrate that expression of sma-3 in pharyngeal muscle is sufficient to restore survival of sma-3 deficient animals. DBL-1 signaling regulates expression of AMPs ABF-2 (antibacterial factor related; Kato et al., 2002) and CNC-2 (Caenacin) (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009) and this regulation is through R-Smad SMA-3. We further show that pharyngeal expression of SMA-3 regulates ABF-2 and CNC-2 expression following pathogen exposure. Finally, we demonstrate that sma-3 mutants have a reduced pharyngeal pumping rate that could increase sensitivity to pathogens and that expression of sma-3 in pharyngeal muscle restores the pumping rate to control levels.

RESULTS

DBL-1 Pathway R-Smad SMA-3 is required for survival against bacterial pathogen

Canonical TGF-β signaling employs a Co-Smad that forms a heterotrimer with R-Smads (Massagué, 1998). In response to fungal infection with Drechmeria coniospora, DBL-1/BMP signaling provides host protection through a noncanonical signaling cascade that does not include a Co-Smad (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009). DBL-1 signaling activity is also required for C. elegans survival against infection by the Gram-negative bacterium S. marcescens (Mallo et al., 2002); which signaling components are required for this response was not determined. We therefore analyzed the survival phenotype of R-Smad mutant sma-3 on S. marcescens. Animals were transferred from Escherichia coli food to pathogenic bacteria at the fourth larval (L4) stage and survival on pathogen was monitored through adulthood until death. When we compare the survival of sma-3 mutant animals, we see that they display a significantly reduced survival compared with control animals when exposed to S. marcescens infection, thus indicating that SMA-3 is involved in the response to S. marcescens infection (Figure 1B). We similarly observed that sma-3 mutants have reduced survival when infected with the Gram-negative bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens (Figure 1C), a pathogenic bacterium that is more virulent than S. marcescens against C. elegans. We have previously shown that sma-3 mutants do not have a shortened lifespan on nonpathogenic bacteria (Clark et al., 2021). We conclude that SMA-3 plays a significant role in C. elegans survival against different bacterial pathogens.

Expression of sma-3(+) in pharyngeal muscle rescues survival of sma-3 mutants

DBL-1 pathway Smads – SMA-2, SMA-3, and SMA-4 – are endogenously expressed in the epidermis, the intestine, and the pharynx (Savage et al., 1996; Suzuki et al., 1999; Inoue and Thomas, 2000; Savage-Dunn et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2001; Mallo et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). We have previously used tissue-specific rescue of sma-3 mutants to address its focus of action for different biological functions. For body size regulation, expression of sma-3 in the epidermis alone is sufficient to rescue the body size phenotype in a sma-3 mutant background (Wang et al., 2002).

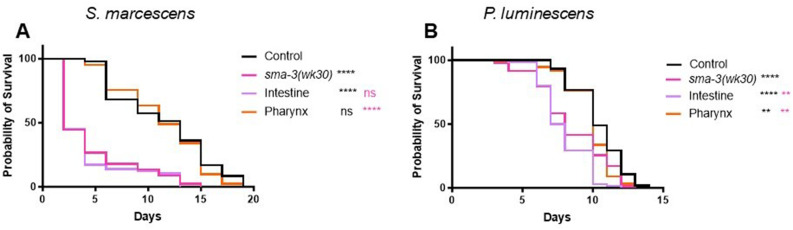

We now sought to address in which tissue(s) SMA-3 activity is required to provide protection against bacterial infection. We used transgenic C. elegans strains in a sma-3 mutant background to conduct these experiments. These strains have sma-3 expressed under the control of tissue-specific promoters (control using endogenous sma-3p promoter; intestinal expression using vha-6p; pharyngeal muscle expression using myo-2p; epidermal expression using vha-7p), allowing for expression of sma-3 in a tissue-specific manner. We hypothesized that intestinal SMA-3 would rescue survival, as the intestine is the main tissue in which an immune response to pathogenic bacteria has been described. Upon exposure to S. marcescens we found that expression of sma-3 in pharyngeal muscle but not in intestine resulted in rescue of the sma-3 mutant reduced survival phenotype. (Figure 2A). We repeated this experiment using P. luminescens and similarly found that pharyngeal expression of sma-3 alone was sufficient to rescue the sma-3 mutant survival phenotype (Figure 2B). Interestingly, on this pathogen, intestinal expression of sma-3 resulted in a worse survival outcome compared with sma-3 mutants. In initial trials it appeared that epidermal expression also rescued survival, but further examination revealed that the strain being employed had expression in additional tissues as well. We therefore repeated the survival experiments with a new, validated epidermal-specific strain (Supplemental Figure S1). In this strain, epidermal expression of sma-3 failed to rescue (Supplemental Figure S2). From these results we conclude that the pharynx plays a significant role for DBL-1 pathway activity in response to bacterial infection in C. elegans.

FIGURE 2:

Expression of sma-3(+) in pharyngeal muscle rescues survival of sma-3 mutants. (A) Survival analysis of tissue-specific sma-3 expressing strains on S. marcescens. Tissue-specific strains have sma-3 expressed under the regulation of tissue-specific promotors in a sma-3(wk30) mutant background: vha-6p for intestinal expression and myo-2p for pharyngeal expression. n values: Control (47), sma-3 (45) Intestine (58), Pharynx (41). (B) Survival of tissue-specific sma-3 expressing strains on P. luminescens. n values: Control (102), sma-3 (82), Intestine (134), Pharynx (131). Survival analyses were repeated and results were consistent across trials. Statistical analysis was done using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test. ns P > 0.05; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001; **** P < 0.0001. Black asterisks show significance relative to control; magenta shows significance relative to sma-3 mutant.

DBL-1 regulates expression of AMPs abf-2 and cnc-2 through SMA-3

We next tested whether the protective nature of DBL-1 signaling against bacterial infection is due to induction of AMP expression. Because a transcriptional response to P. luminescens is detected after 24 h of exposure, while the transcriptional response to Serratia takes longer, we performed transcriptional assays in response to P. luminescens. We tested a panel of 12 immune response genes via qRT-PCR to determine whether DBL-1 signaling regulates their expression when animals are exposed to P. luminescens (Kato et al., 2002; Mallo et al., 2002; Alper et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2007; Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009; Gravato-Nobre et al., 2016) (Supplemental Figure S3). L4 animals were transferred from control plates to pathogen and collected as Day 1 adults following 24-h exposure to pathogen. From this analysis we found two genes that demonstrated the expression pattern we expected if their regulation was mediated through DBL-1. Both abf-2 and cnc-2 were significantly upregulated in control animals upon 24-h exposure to bacterial pathogen. Neither of these genes had a significant increase in expression in dbl-1 mutant animals under the same infection conditions (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3:

DBL-1 regulates expression of AMPs abf-2 and cnc-2 through SMA-3. (A) qRT-PCR results for abf-2 and cnc-2 expression in dbl-1(wk70) animals on control bacteria and P. luminescens. (B) qRT-PCR results for abf-2 and cnc-2 in sma-3(wk30) animals on control bacteria and P. luminescens. (C) Survival analysis of cnc-2(ok3226) animals on P. luminescens pathogenic bacteria. n values: Control (91), cnc-2 (74). Survival analysis was repeated and results were consistent across trials. Data for qRT-PCR represents repeated analyses from two biological replicates. Statistical analysis for qRT-PCR was done using One-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism 9. Error bars represent SD. Statistical analysis for survival was done using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test. ns P > 0.05; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; **** P < 0.0001.

ABF-2 is an antibacterial factor related protein that has been shown to be expressed in the pharynx of C. elegans and is involved in the response against bacterial infection (Kato et al., 2002). cnc-2 encodes a Caenacin protein previously shown to be involved in the C. elegans immune response to fungal infection, where it is regulated in epidermal tissue (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009). Our results suggest that both abf-2 and cnc-2 are regulated by DBL-1 signaling during the response to a bacterial pathogen.

We then used qRT-PCR to test whether sma-3 mutants demonstrate any change in abf-2 levels when exposed to bacterial pathogen. Following 24-h exposure to P. luminescens bacteria, sma-3 mutants demonstrated no increase in abf-2 levels as compared with control conditions. Additionally, sma-3 mutants expressed overall lower levels of abf-2 than control animals even in control conditions (Figure 3B). This observation indicates that SMA-3 plays a role in the regulation of antimicrobial peptide ABF-2. When we use qRT-PCR to assess the expression pattern of cnc-2 in sma-3 mutants, we find a similar pattern for cnc-2 expression. Control animals have a significant increase in cnc-2 expression under infection conditions while sma-3 mutants demonstrate no significant change in cnc-2 expression when exposed to bacterial pathogen (Figure 3B). From these data we conclude that DBL-1 signaling does regulate expression of known immune response genes and that loss of the signaling effector SMA-3 prevents induction of both abf-2 and cnc-2 expression.

As previously noted, earlier work showed that cnc-2 is involved in the C. elegans response to fungal infection (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009). cnc-2 was shown to be upregulated in response to Serratia as well (Mallo et al., 2002), but that study did not test its function in survival. We therefore followed up these experiments with a survival analysis of a cnc-2 mutant on P. luminescens to determine whether cnc-2 plays a role in bacterial infection as well as fungal infection. We used cnc-2(ok3226) mutants, a likely null allele with a 509 bp deletion of the cnc-2 locus. cnc-2 mutant animals had a significantly reduced survival rate when exposed to P. luminescens as compared with control animals (Figure 3C). We therefore conclude that CNC-2 plays a role in bacterial infection, in addition to its known role against fungal pathogen (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009).

DBL-1 pathway mediated regulation of AMP expression requires pharyngeal SMA-3 activity

Bacterial infection such as that caused by S. marcescens or P. luminescens results in colonization in the intestine of the worm (Tan et al., 1999; Garsin et al., 2001; Mallo et al., 2002; Kurz and Ewbank, 2003; Sato et al., 2014). As our survival analyses demonstrated that intestine-specific sma-3 expression was not sufficient to ameliorate the sma-3 reduced survival phenotype, we next tested whether DBL-1 mediated regulation of antimicrobial factors depends on pharyngeal SMA-3. We performed qRT-PCR analysis to establish the expression patterns for abf-2 and cnc-2 after a 24-h exposure to P. luminescens bacteria. Consistent with our survival analysis results, which indicated significance for pharyngeal sma-3 expression in C. elegans survival, sma-3 expression in the pharynx was sufficient to cause an induction in abf-2 and cnc-2 transcript levels following P. luminescens exposure (Figure 4, A and B).

FIGURE 4:

Pharyngeal expression of SMA-3 mediates regulation of AMP expression. (A) qRT-PCR results for abf-2 in transgenic sma-3 expressing animals on control bacteria and P. luminescens. (B) qRT-PCR results for cnc-2 in transgenic sma-3 expressing animals on control bacteria and P. luminescens. Data for qRT-PCR represents repeated analyses from two biological replicates. Statistical analysis for qRT-PCR was done using One-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test, using GraphPad Prism 9. Error bars represent SD. ns P > 0.05; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Expression of sma-3 in pharyngeal muscle restores pumping rate in sma-3 mutants

We next investigated whether sma-3 expression in the pharynx resulted in any effect on the mechanical function of the pharynx, by assaying the pharyngeal pumping rate. To match the conditions of our survival and gene expression studies, we transferred L4 animals from control plates to plates seeded with pathogenic P. luminescens bacteria and measured pumping rates in Day 1 adults after 24 h of exposure to pathogen. We found that sma-3 mutants had a reduction in pumping rate as compared with control animals on pathogen. The pumping rate of sma-3 mutants was restored when sma-3 was expressed solely in the pharynx (Figure 5A), indicating potentially cell autonomous regulation of pumping rate by SMA-3. We also determined the pharyngeal pumping rate of sma-3 mutants on nonpathogenic E. coli, and found that it was similarly reduced compared with wild type (Figure 5B). This result indicates that the reduced pumping rate is an underlying property of sma-3 mutants, not a pathogen-induced alteration. Reduced pumping rate could potentially have two opposing effects; either lowering intake of bacteria, which would be expected to increase survival, or allowing intake of more intact, live bacteria, which would be more consistent with the observed reduced survival. To distinguish between these alternatives, we fed animals fluorescently tagged OP50-GFP (nonpathogenic E. coli) and imaged them after 24 h of exposure (Figure 5, C–F). As expected, wild-type N2 animals display no fluorescent bacteria in their intestinal lumens after 24-h exposure to OP50-GFP (Figure 5C). A small amount of fluorescent bacteria can be seen in the pharynx, where it is likely destroyed in the grinder. In contrast, a pharyngeal defective mutant, phm-2, displays a significant accumulation of bacteria in their intestinal lumens after 24-h exposure to OP50-GFP (Figure 5D), consistent with a failure to destroy bacteria in the pharynx. dbl-1 mutants have slightly more bacterial accumulation than wild type after 24-h exposure to OP50-GFP (Figure 5E). However, levels remain low compared with phm-2 mutants. This finding is consistent with the normal pumping rate of dbl-1 mutants on E. coli and P. luminescens (Ciccarelli et al., 2023). The slight accumulation of live bacteria is likely due to the innate immune defect of this mutant. Finally, sma-3 mutants display very high bacterial accumulation after 24-h exposure to OP50-GFP (Figure 5F), similar to that in phm-2 mutants, demonstrating the consequences of the grinder defect in sma-3 animals.

FIGURE 5:

SMA-3 controls pharyngeal pumping rate cell autonomously. (A.) Pumping rate in pumps/20 Seconds of sma-3(wk30) mutants and pharyngeal sma-3 rescue animals on P. luminescens bacteria. (B.) Pumping rate in pumps/20 s of sma-3(wk30) mutants and on E. coli bacteria. Ten worms per strain were counted and experiments were repeated on two to three separate biological replicates. Results were consistent across all trials. Statistical analysis was performed using One way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test, using GraphPad Prism 9. ns P > 0.05; **** P ≤ 0.0001. C–F. L4 animals of the designated genotypes were exposed to fluorescent OP50-GFP E. coli bacteria for 24 h and 10 or more animals imaged as Day 1 adults. The experiment was repeated in triplicate. All scale bars show 100 µm.

To assess whether functionality of the pharynx contributes to survivability on pathogenic bacteria, we determined the survival patterns and pumping rates of two pharyngeal defect mutants. We used eat-2 and phm-2, both involved in pharyngeal grinder function, for these experiments. Mutations of eat-2 (Avery, 1993; Raizen et al., 1995; Lakowski and Hekimi, 1998; Avery and You, 2012) or of phm-2 (Avery, 1993; Kumar et al., 2019; Scharf et al., 2021) result in reduced grinder function and a reduced rate of pharyngeal pumping. Following exposure of either strain to P. luminescens bacteria for 24 h, there was a significant decrease in pharyngeal pumping rate (Figure 6, A and B), consistent with our expectations. Furthermore, both phm-2 and eat-2 mutants have a significantly reduced rate of survival compared with control animals when exposed to P. luminescens as well (Figure 6, C and D). Other studies have also demonstrated that both mutations result in sensitivity to bacterial infection, due to live bacteria reaching the intestine for colonization (Labrousse et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2002; Portal-Celhay et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2019; Scharf et al., 2021). Taking all of our results together with these prior studies suggests that disrupting pharyngeal function contributes to susceptibility to infection.

FIGURE 6:

Mutants with pharyngeal defects have reduced survival on P. luminescens bacteria. (A–B) Pharyngeal pumping rate in pumps/20 s for pharyngeal defect mutants phm-2(ad597) and eat-2(ad1116) on P. luminescens bacteria. Ten worms per strain were counted and experiments were repeated on two separate biological replicates. Results were consistent across all trials. Statistical analysis was performed using One way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparison test, using GraphPad Prism 9. (C–D) Survival analysis of phm-2(ad597) and eat-2(ad1116) on P. luminescens bacteria. N values: Control (81), phm-2 (99), Control (96), eat-2 (58). Statistical analysis was done using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test. **** P ≤ 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

The BMP-like ligand DBL-1 has previously been shown to play a significant role in the C. elegans immune response to bacterial pathogen (Mallo et al., 2002). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the DBL-1 pathway effector, R-Smad SMA-3 is involved in a noncanonical signaling response to fungal infection, in which it acts without SMA-2 or the Co-Smad SMA-4 (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009). A strength of the C. elegans system is the ability to ask questions about site of action in the context of the intact organism, shedding light on how systemic organismal responses may be generated. We had previously shown that sma-3 expressed solely in the epidermis is sufficient to restore normal body size in adult animals (Wang et al., 2002). In this study, we employed survival analyses to determine where SMA-3 acts in the C. elegans immune response to bacterial pathogens. We demonstrate that sma-3 expression in the intestinal site of infection does not have any measurable effect on survival against bacterial pathogen. However, expression of sma-3, and therefore pathway activity, in the pharynx, does restore survival towards that of control animals. Improved survival of pharynx-specific expressing strains as compared with sma-3 mutants suggests the cell nonautonomous activity of the DBL-1 pathway on immunity.

We also determined whether the effect of DBL-1 signaling on the immune response to bacterial pathogen is related to regulation of immune response related genes. Here we demonstrate through qRT-PCR analysis that DBL-1 signaling regulates the expression of abf-2 and cnc-2 transcripts upon exposure to pathogenic P. luminescens. We also show that this effect is regulated through R-Smad SMA-3 expression in the pharynx. This result supports the hypothesis that DBL-1 signaling to regulate AMP expression is both cell autonomous and cell nonautonomous. We note that expression levels in some of the sma-3 transgenic strains are higher than those seen in N2 control animals, which could be due to a higher level of expression of SMA-3 from the multicopy transgenes.

The antibacterial factor related peptide ABF-2 has previously been shown to play a role in the response to bacterial pathogen (Kato et al., 2002). abf-2 has a complex relationship with abf-1: the two genes are capable of being transcribed as a polycistronic operon transcript, but also as individual genes with different expression patterns. It will be interesting to determine whether SMA-3 acts at the level of transcription or posttranscriptionally to mediate regulation of these genes. In contrast, CNC-2 has been primarily correlated with fungal infection of the epidermis (Zugasti and Ewbank, 2009; Zehrback et al., 2017) and has not previously been associated with induction in response to P. luminescens infection. Previous investigations utilizing microarray and RNA-seq have only found decreases in cnc-2 upon P. luminescens infection, although this difference may relate to the different methodologies used (Wong et al., 2007; Engelmann et al., 2011). In light of this, we also looked to see how cnc-2 mutants survive on P. luminescens and found that cnc-2 mutant animals had a significantly reduced survival compared with control animals. This increased susceptibility is consistent with our findings by qRT-PCR and the results demonstrating that DBL-1 signaling regulates cnc-2 expression levels in response to bacterial pathogen exposure as part of the C. elegans immune response to P. luminescens infection.

Because the focus of action of SMA-3 in innate immunity is the pharynx, we considered whether DBL-1 signaling activity in the pharynx influences the physical function of the pharynx. The pharynx itself is an early site of exposure for C. elegans, as ingestion of bacteria brings pathogen through the pharynx before intact bacteria can be passed to the intestine. Typically, the pharyngeal grinder functions to break down these bacterial cells mechanically, inhibiting live bacteria from entering the intestine, preventing infection, and providing nutritional support. However, in instances of reduced pharyngeal pumping/grinder activity or exposure to more pathogenic bacteria, elevated levels of live bacteria in the intestine result in proliferation and infection (Kurz et al., 2003; Gravato-Nobre and Hodgkin, 2005).

We used pharyngeal pumping rate as a method for measuring the effect of sma-3 on pharyngeal mechanical action (Raizen et al., 2012). We found that sma-3 mutant animals have a reduced pharyngeal pumping rate as compared with control animals and that this reduction can be rescued with expression of sma-3 in pharyngeal muscle. Similarly, pharyngeal function mutants phm-2 and eat-2 have reduced survival on P. luminescens. We demonstrated that sma-3 mutants and phm-2 mutants accumulate fluorescent E. coli in the intestine, demonstrating that reduced pharyngeal pumping can lead to diminished physical disruption of bacteria. In the case of pathogens, increased levels of live bacteria entering the intestine can cause pathological harm. In summary, we have identified the pharyngeal muscle as a critical responder to BMP signaling to generate a system organismal response to pathogenic bacteria. R-Smad SMA-3 in the pharynx is sufficient to rescue multiple defects, including reduced survival, loss of induction of AMPs, and altered pharyngeal pumping. Although most work on the C. elegans immune response to bacteria has focused on the intestine, the pharynx is an earlier point of contact for exposure to bacteria and may play a more important role than previously recognized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Request a protocol through Bio-protocol.

Nematode Strains and Growth Conditions

C. elegans were maintained on E. coli (DA837) at 20°C on EZ worm plates containing streptomycin (550 mg Tris-Cl, 240 mg Tris-OH, 3.1 g Bactopeptone, 8 mg cholesterol, 2.0 g NaCl, 200 mg streptomycin sulfate, and 20 g agar per liter). The N2 strain was used as a control unless otherwise specified. In tissue-specific sma-3 experiments, the strains used were: CS152 qcIs6[GFP::sma-3 + rol-6(su1006)], CS640 sma-3(wk30); qcIs53[myo-2p::GFP::sma-3 + rol-6(su1006)], CS619 sma-3(wk30); qcIs59[vha-6p::GFP::sma-3 + rol-6(su1006)], CS215 sma-3(wk30); him-5(e1490); qcEx55[vha-7p::GFP::sma-3 + rol-6(su1006)], CS635 sma-3(wk30); qcIs62[rol-6(su1006)]. Remaining strains used in this study were: sma-3(wk30), cnc-2(ok3226), sma-6(wk7), sma2(e502), dbl-1(wk70), phm-2(ad597), eat-2(ad1116). All mutations employed are strong loss-of-function or null alleles. In particular, the sma-3 allele wk30 contains a premature termination codon.

Bacteria

Control bacteria used in all experiments was E. coli strain DA837, cultured at 37°C. S. marcescens strain Db11 cultured at 37°C and P. luminescens (ATCC #29999) cultured at 30°C were used for pathogenic bacteria exposure. Serratia (Db11) was seeded on EZ worm plates containing streptomycin and grown at 37°C. P. luminescens was seeded on EZ worm plates with no antibiotic and grown at 30°C.

Survival Analysis

Survival plates were prepared at least one day before plating worms. Each plate was seeded with 500 µl of pathogenic bacteria. FuDR (5-Fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine) was used to prevent reproduction, at a concentration of 50 µM per plate. This treatment was done to reduce the incidence of matricide by internal hatching of embryos during survival analysis. All survival experiments were carried out at 20°C. All survival analyses were repeated. All graphs were made using GraphPad Prism software and statistical analysis performed using Logrank/Mantel Cox test.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Worms were synchronized using overnight egg lay followed by 4-h synchronization. When animals reached L4 stage, they were washed and moved to experimental plates for 24-h exposure to P. luminescens. Animals were collected and washed after 24-h exposure and RNA was extracted using previously published protocol (Yin et al., 2015) followed by Qiagen RNeasy miniprep kit (Catalogue. No. 74104). cDNA was generated using Invitrogen SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix (Catalogue. No.11756050). qRT-PCR analysis was done using Applied Biosystems Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Catalogue. No. 4367659). Delta Ct analysis was done using Applied Biosystems and StepOne software. All qRT-PCR analysis was repeated on separate biological replicates. All graphs were made using GraphPad Prism software and statistical analysis was performed using One-way ANOVA with Multiple Comparison Test, as calculated using the GraphPad software.

Pumping Rate Experiments

Pumping rate experiments were done with animals exposed at L4 stage for 24 h on P. luminescens bacteria. Pharyngeal pumps were counted over 20 s timespan (Raizen et al., 2012). All pumping experiments were repeated. Graph made using GraphPad Prism software and statistical analysis performed using One-way ANOVA with Multiple Comparisons Test, as calculated using the GraphPad software.

OP50-GFP Assay

Antibiotic-free plates were each seeded with 500 µl of OP50-GFP and incubated overnight at 37°C. Twenty L4 animals were picked onto each OP50-GFP plate. After 24 h, worms were prepared for imaging. Worms were picked into a droplet of M9 on a regular OP50 plate and allowed to crawl out of the droplet. This removed any surface fluorescent bacteria left on the animal, which may interfere with imaging. Worms were mounted on 2% agarose pads containing a 5 µl drop of 2.5 mM levamisole for immobilization. A small hair was used to align the animals. Images were taken on a Zeiss Axioskop with Gryphax software and a 10X objective. Experiment was repeated in triplicate.

Imaging GFP Reporter Strains

L4 animals were mounted on 2% agarose pads containing a 5 µl drop of 2.5 mM levamisole for immobilization. Images were taken on a Zeiss ApoTome 3 with Zen Pro software and a 20X objective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health awards R15GM112147 and R21AG075315, and by a Professional Staff Congress – City University of New York grant to C.S.D. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is supported by the National Institute of Health - Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). The cnc-2(ok3226) strain was generated by the C. elegans Gene Knockout Project at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium. Genetic data from WormBase (Davis et al., 2022) were critical to the execution of this project. This work was carried out in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree from the Graduate Center of City University of New York (E.J.C. and K.K.Y.).

Abbreviations used:

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- L4

fourth larval stage

- N2

nematode 2, the wild-type Bristol strain of C. elegans

- ns

not significant

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SD

standard deviation

- Smad

sma- and Mad-related

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E23-05-0185) on February 21, 2024.

REFERENCES

- Alper S, McBride SJ, Lackford B, Freedman JH, Schwartz DA (2007). Specificity and complexity of the Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response. Mol Cell Biol 27, 5544–5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Wrana JL (1996). Signal transduction by members of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 7, 327–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L (1993). The genetics of feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 133, 897–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, You YJ (2012). C. elegans feeding. WormBook: The online review of C. elegans biology. Available at: www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_feeding/feeding.html (accessed 16 January 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen W, ten Dijke P (2016). Immunoregulation by members of the TGFβ superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 723–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli EJ, Wing Z, Bendelstein M, Johal RK, Singh G, Monas A, Savage-Dunn C (2023). TGF-β ligand cross-subfamily interactions in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to bacterial pathogens. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2023.05.05.539606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JF, Meade M, Ranepura G, Hall DH, Savage-Dunn C (2018). Caenorhabditis elegans DBL-1/BMP regulates lipid accumulation via interaction with insulin signaling. G3 (Bethesda) 8, 343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JF, Ciccarelli EJ, Kayastha P, Ranepura G, Yamamoto KK, Hasan MS, Madaan U, Meléndez A, Savage-Dunn C (2021). BMP pathway regulation of insulin signaling components promotes lipid storage in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 17, e1009836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P, Zarowiecki M, Arnaboldi V, Becerra A, Cain S, Chan J, Chen WJ, Cho J, da Veiga Beltrame E, Diamantakis S, et al. (2022). WormBase in 2022-data, processes, and tools for analyzing Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 220, iyac003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang Y, Feng XH (1998). Smads: transcriptional activators of TGF-beta responses. Cell 95, 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann I, Griffon A, Tichit L, Montañana-Shanchis F, Wang G, Reinke V, Waterston RH, Hillier LW, Ewbank JJ (2011). A comprehensive analysis of gene expression changes provoked by bacterial and fungal infection in C. elegans. PLoS One 6, e19055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, Qin X, Singh KV, Murray BE, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM (2001). A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 10892–10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravato-Nobre MJ, Hodgkin J (2005). Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for innate immunity to pathogens. Cell Microbiol 7, 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravato-Nobre MJ, Vaz F, Filipe S, Chalmers R, Hodgkin J (2016). The invertebrate lysozyme effector ILYS-3 is systematically activated in response to danger signals and confers antimicrobial protection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog 12, e1005826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumienny TL, Savage-Dunn C (2018). TGF-β signaling in C. elegans. WormBook: The online review of C. elegans biology. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19692/ (accessed 16 January 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P (1997). TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 390, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA, Kafatos FC, Janeway CA, Ezekowitz RA (1999). Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 284, 1313–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Thomas JH (2000). Targets of TGF-β signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans dauer formation. Dev Biol 217, 192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irazoqui JE, Ng A, Xavier RJ, Ausubel FM (2008). Role for beta-catenin and HOX transcription factors in Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian host epithelial-pathogen interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 17469–17474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Aizawa T, Hoshino H, Kawano K, Nitta K, Zhang H (2002). abf-1 and abf-2, ASABF-type antimicrobial peptide genes in Caenorhabditis elegans . Biochem J 361, 221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Ewbank JJ (2018). Signaling in the innate immune response. WormBook: The online review of C. elegans biology. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19673/ (accessed 16 January 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, Emerson FE, Garsin DA, Inoue H, Tanaka-Hino M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Tan MW, et al. (2002). A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297, 623–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Egan BM, Kocsisova Z, Schneider DL, Murphy JT, Diwan A, Kornfeld K (2019). Lifespan extension in C. elegans caused by bacterial colonization of the intestine and subsequent activation of an innate immune response. Dev Cell 49, 100–117.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ (2003). Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging genetic model for the study of innate immunity. Nat Rev Genet 4, 380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz CL, Chauvet S, Andrès E, Aurouze M, Vallet I, Michel GPF, Uh M, Celli J, Filloux A, de Bentzmann S, et al. (2003). Virulence factors of the human opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens identified by in vivo screening. EMBO J 22, 1451–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse A, Chauvet S, Couillault C, Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ (2000). Caenorhabditis elegans is a model host for Salmonella typhimurium. Curr Biol 10, 1543–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S (1998). The genetics of caloric restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 13091–13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallo GV, Kurz CL, Couillault C, Pujol N, Granjeaud S, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ (2002). Inducible antibacterial defense system in C. elegans. Curr Biol 12, 1209–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J (1998). TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 67, 753–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway CA (1998). Innate immune recognition and control of adaptive immune responses. Semin Immunol 10, 351–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet ACM, Ewbank JJ (2004). Immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Opin Immunol 16, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Flemming AJ, Sugihara Y, Mochii M, Suzuki Y, Yoshida S, Wood WB, Leroi AM, Ueno N (2002). A Caenorhabditis elegans TGF-β, DBL-1, controls the expression of LON-1, a PR-related protein, that regulates polyploidization and body length. EMBO J 21, 1063–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett RW, Das P, Krishna S (1998). TGF-β signaling, Smads, and tumor suppressors. Bioessays 20, 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge FA, Gravato-Nobre MJ, Hodgkin J (2010). Signal transduction pathways that function in both development and innate immunity. Dev Dyn 239, 1330–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal-Celhay C, Bradley ER, Blaser MJ (2012). Control of intestinal bacterial proliferation in regulation of lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Microbiol 12, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM (2012). Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol 24, 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen D, Song BM, Trojanowski N, You YJ (2012). Methods for measuring pharyngeal behaviors. WormBook: The online review of C. elegans Biology. Available at: www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_measurepharyngeal/measurepharyngeal.html (accessed 15 September 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raizen DM, Lee RY, Avery L (1995). Interacting genes required for pharyngeal excitation by motor neuron MC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 141, 1365–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Yoshiga T, Hasegawa K (2014). Activated and inactivated immune responses in Caenorhabditis elegans against Photorhabdus luminescens TT01. Springerplus 3, 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage C, Das P, Finelli AL, Townsend SR, Sun CY, Baird SE, Padgett RW (1996). Caenorhabditis elegans genes sma-2, sma-3, and sma-4 define a conserved family of transforming growth factor beta pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 790–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Dunn C, Tokarz R, Wang H, Cohen S, Giannikas C, Padgett RW (2000). SMA-3 Smad has specific and critical functions in DBL-1/SMA-6 TGFβ-related signaling. Dev Bio 223, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf A, Pohl F, Egan BM, Kocsisova Z, Kornfeld K (2021). Reproductive aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: from molecules to ecology . Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 718522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg H, Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ (2004). Evolution of the innate immune system: the worm perspective. Immunol Rev 198, 36–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MP, Laws TR, Atkins TP, Oyston PCF, de Pomerai DI, Titball RW (2002). A liquid-based method for the assessment of bacterial pathogenicity using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 210, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Yandell MD, Roy PJ, Krishna S, Savage-Dunn C, Ross RM, Padgett RW, Wood WB (1999). A BMP homolog acts as a dose-dependent regulator of body size and male tail patterning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 126, 241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM (1999). Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 715–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tokarz R, Savage-Dunn C (2002). The expression of TGFbeta signal transducers in the hypodermis regulates body size in C. elegans. Development 129, 4989–4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman M (1998). Smads and early developmental signaling by the TGFbeta superfamily. Genes Dev 12, 2445–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D, Bazopoulou D, Pujol N, Tavernarakis N, Ewbank JJ (2007). Genome-wide investigation reveals pathogen-specific and shared signatures in the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to infection. Genome Biol 8, R194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto KK, Savage-Dunn C (2023). TGF-β pathways in aging and immunity: lessons from Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Genet 14, 1220068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Madaan U, Park A, Aftab N, Savage-Dunn C (2015). Multiple cis elements and GATA factors regulate a cuticle collagen gene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genesis 53. 278–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Morita K, Mocchi M, Ueno N (2001). Hypodermal expression of Caenorhabditis elegans TGF-beta type I receptor SMA-6 is essential for the growth and maintenance of body length. Dev Biol 240, 32–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehrbach A, Rogers A, Tarr D (2017). An investigation of the potential antifungal properties of CNC-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Nematol 49, 472–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zugasti O, Ewbank JJ (2009). Neuroimmune regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression by a noncanonical TGF-beta signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans epidermis. Nat Immunol 10, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]