Abstract

Initiation of simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA replication is dependent upon the assembly of two T-antigen (T-ag) hexamers on the SV40 core origin. To further define the oligomerization mechanism, the pentanucleotide requirements for T-ag assembly were investigated. Here, we demonstrate that individual pentanucleotides support hexamer formation, while particular pairs of pentanucleotides suffice for the assembly of T-ag double hexamers. Related studies demonstrate that T-ag double hexamers formed on “active pairs” of pentanucleotides catalyze a set of previously described structural distortions within the core origin. For the four-pentanucleotide-containing wild-type SV40 core origin, footprinting experiments indicate that T-ag double hexamers prefer to bind to pentanucleotides 1 and 3. Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that only two of the four pentanucleotides in the core origin are necessary for T-ag assembly and the induction of structural changes in the core origin. Since all four pentanucleotides in the wild-type origin are necessary for extensive DNA unwinding, we concluded that the second pair of pentanucleotides is required at a step subsequent to the initial assembly process.

The protein-DNA interactions that take place at eukaryotic origins of DNA replication are poorly characterized. This situation reflects, in part, the failure to identify DNA sequences that constitute higher eukaryotic origins of replication (13). Moreover, there is limited structural information about the initiator proteins that recognize origins of replication (35, 67). Indeed, structural information is currently limited to the origin binding domains of initiators encoded by simian virus 40 (SV40) (45), bovine papillomavirus (33), and Epstein-Barr virus (1, 2).

In view of these limitations, a useful model for studies of the protein-DNA interactions that take place at eukaryotic origins is the binding of the virus-encoded T-antigen (T-ag) to the SV40 origin of replication. The well-characterized SV40 core origin is 64 bp long and consists of three separate domains (20, 21). The central region, termed site II (or pentanucleotide palindrome), contains four GAGGC pentanucleotides that serve as binding sites for T-ag (24, 69, 70). Site II is flanked by a 17-bp adenine-thymine (AT)-rich domain and the early palindrome (EP) (reviewed in references 4 and 29).

T-ag, a 708-amino-acid phosphoprotein, has been extensively studied (reviewed in references 4, 9, and 29). The structure of the T-ag domain that is necessary and sufficient for binding to the SV40 origin, T-ag-obd131-260, was solved by use of nuclear magnetic resonance techniques (45). When the structure was viewed in terms of previous mutagenesis studies of T-ag (65, 76), considerable insight into the mechanism of binding of T-ag to individual pentanucleotides was obtained. For example, it is now apparent that site-specific binding is mediated by a pair of loops (45), a common motif in protein-DNA interactions (9, 41). Additional insights into T-ag binding to individual pentanucleotides, based on the T-ag-obd131-260 structure, were described in a recent review (9). Related studies have provided additional insights into the T-ag–core interaction; for example, studies have demonstrated that T-ag residues 121 to 135 are important for interactions with the AT-rich region (14).

The initiation of SV40 replication depends upon not one but multiple protein-DNA interactions at the SV40 core origin. Initial studies demonstrated that in the absence of ATP, T-ag formed oligomers on the SV40 origin (8, 30, 31, 55). In subsequent studies, it was observed that the addition of ATP stimulated the binding of T-ag to the core origin 10- to 15-fold and induced the formation of a larger multimeric complex (6, 18, 22). With electron microscopy, it was determined that the multimeric complex was a bilobed structure (18, 19) and that each lobe contained six monomers of T-ag (48, 62). Models for double hexamer formation on the SV40 core origin have been proposed (4, 15, 48, 51, 58, 59), although they are based on limited experimental evidence.

Regarding the role of the pentanucleotides in origin recognition and initiation of replication, it is known that all four pentanucleotides are necessary for origin-dependent DNA unwinding (16, 58) and replication events (16). Furthermore, most previous studies have suggested that all four pentanucleotides are required for double-hexamer formation (for reviews, see references 4, 9, and 29). However, recent studies demonstrated that all four pentanucleotides were not simultaneously bound by T-ag-obd131-260 (37). Instead, these experiments demonstrated that only two of the four pentanucleotides were required for stable binding to the core origin. Additional studies indicated that only those pentanucleotides arranged in a head-to-head orientation and separated by about one turn of a DNA double helix could serve as binding sites for T-ag-obd131-260 (37). It was proposed that T-ag-obd131-260 binding to particular pairs of pentanucleotides may mimic the nucleation of T-ag double-hexamer formation (37). In view of these studies, we elected to examine the role of the pentanucleotides in the T-ag oligomerization process. The results of these experiments are presented here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Commercial supplies of enzymes, DNA, reagents, and oligonucleotides.

T4 polynucleotide kinase was purchased from Promega. T4 DNA ligase and HaeIII-digested φX174 replicative-form (RF) DNA were obtained from Gibco-BRL Life Technologies. Alkaline phosphatase (calf intestine) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, while restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England BioLabs. Reagents for the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting procedure were obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 394 DNA synthesizer at the protein chemistry facility at Tufts University. The oligonucleotides were purified by electrophoresis through 10% polyacrylamide–urea gels and isolated by standard methods (60).

Purification of T-ag.

SV40 T-ag was prepared by use of a baculovirus expression vector containing the T-ag-encoding SV40 A gene (56) and was isolated by immunoaffinity techniques with monoclonal antibody PAb 419 as previously described (27, 64, 75). Purified T-ag was dialyzed against T-ag storage buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2 μg of leupeptin per ml, 0.2 μg of antipain per ml, 10% glycerol) and frozen at −70°C until use. When analyzed on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels (15, 59), the T-ag preparations were found to contain approximately 80% monomers and 20% hexamers.

Band shift assays.

Double-stranded oligonucleotides were formed by incubating complementary pairs of oligonucleotides in hybridization buffer (38). The double-stranded oligonucleotides were 32P labeled by standard procedures (60). The labeled oligonucleotides were purified by electrophoresis on neutral 10% polyacrylamide gels (run in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE] [60] at ∼380 V and 25 mA), and the fragments of interest were removed; DNA fragments were then eluted in oligonucleotide extraction buffer (60). After extraction with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1), the labeled oligonucleotides were precipitated with 100% (vol/vol) ethanol, washed with 80% (vol/vol) ethanol, and resuspended in deionized H2O (25 fmol/μl).

Band shift reactions with T-ag and double-stranded oligonucleotides (18, 46, 53) were conducted under replication conditions (75). The reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP (or AMP-PNP, a nonhydrolyzable analog of ATP), 40 mM creatine phosphate (pH 7.6), 0.48 μg of creatine phosphate kinase, 5 μg of bovine serum albumin, 0.8 μg of HaeIII-digested φX174 RF DNA (∼2.5 pmol; used as a nonspecific competitor), 50 fmol of labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide, and either 3 or 6 pmol of T-ag (T-ag was the last component added to the reaction mixture). After a 20-min incubation at 37°C, glutaraldehyde (0.1% final concentration) was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for an additional 5 min. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 5 μl of 6× loading dye II (15% Ficoll, 0.25% bromophenol blue, 0.25% xylene cyanol [60]) to the reaction mixtures. Samples were then applied to 4 to 12% gradient polyacrylamide gels (19:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio) and electrophoresed in 0.5× TBE for ∼2 h (∼500 V and 20 mA). The gels were dried, subjected to autoradiography, and subsequently placed in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) cassette. Band shift reactions were quantitated with the PhosphorImager.

1,10-Phenanthroline–copper footprinting.

Single-stranded oligonucleotides (∼25 pmol) were 32P labeled at their 5′ termini (60) and then hybridized to their complementary strands. The asymmetrically labeled oligonucleotides were purified by the same procedures as those used to isolate the symmetrically labeled oligonucleotides for the band shift reactions.

To provide adequate counts for footprinting, the previously described band shift assay was scaled up fivefold. The gel retardation–1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting reactions were carried out as described by Kuwabara and Sigman (40). Briefly, the reaction products were separated on a 4 to 12% gradient polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE for ∼2 h (∼500 V and 18 mA); after electrophoresis, the gel was rinsed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). DNA cleavage reactions were performed by soaking the gel in 1,10-phenanthroline–CuSO4–3-mercaptopropionic acid (final concentrations, 0.17 mM, 38 μM, and 5 mM, respectively) for 20 min at room temperature. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (final concentration, 2.2 mM) for ∼2 min. The gel was rinsed in H2O, wrapped in plastic wrap, and subjected to autoradiography for ∼1.5 h at room temperature. Acrylamide gel slices containing either free DNA or T-ag double-hexamer–DNA complexes were excised and eluted overnight at 37°C in 550 μl of elution buffer (0.3 M sodium acetate [pH 5.2], 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10 mM magnesium acetate, 10 μg of proteinase K per ml). After removal of acrylamide gel fragments by centrifugation, DNA-containing solutions were subjected to phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extractions; DNA fragments were then precipitated with 100% (vol/vol) ethanol. DNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol (vol/vol), dried, and resuspended at ∼2,000 cpm/μl in a solution containing 80% (vol/vol) formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 0.1% xylene cyanol. Aliquots (5 μl) were boiled for 3 min and applied to a 14% polyacrylamide–urea gel in 1× TBE (∼2,000 V and 28 mA). Sequencing markers were obtained by conducting Maxam-Gilbert (49) G and G+A reactions on the appropriate asymmetrically labeled duplex DNA fragment. Finally, as a control, the gel retardation–1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting reactions were repeated with T-ag-obd131-260 and various oligonucleotides (at a protein/DNA ratio of 120:1) as described by Joo et al. (37).

Constructing the pSV01ΔEP pentanucleotide mutants.

The SV40 origin-containing EcoRII G fragment was removed from plasmid pSV01ΔEP (75) by EcoRI digestion, and the resulting 2,478-bp fragment was isolated from an 0.8% agarose gel with a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The 3′ recessed ends were filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I by standard techniques (60), and the 5′ ends were subsequently dephosphorylated with alkaline phosphatase (60).

Oligonucleotides were subcloned as follows. Upon purification, ∼100 pmol of a given oligonucleotide was hybridized to its complementary strand and treated with kinase (60). One picomole of the duplex oligonucleotide was then ligated to ∼50 fmol of the EcoRII-G-lacking pSV01ΔEP plasmid. After transformation into DH5α cells, plasmids (2,548 bp long) were isolated by standard techniques (60).

The pSV01ΔEP derivative containing the 64-bp core oligonucleotide was termed pSV01ΔEP(core). The pSV01ΔEP derivatives containing site II mutations were named according to the mutant pentanucleotides; for example, the pSV01ΔEP derivative containing the 2-4m oligonucleotide was termed pSV01ΔEP(2-4m). (The sequences of representative oligonucleotides are shown in Fig. 1B.) Dideoxy sequencing reactions were conducted to confirm the sequences of the constructs (61). Sequencing reaction mixtures (∼90,000 cpm of 35S-dATP/lane) were loaded on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea; the gels were electrophoresed and processed as described previously (60).

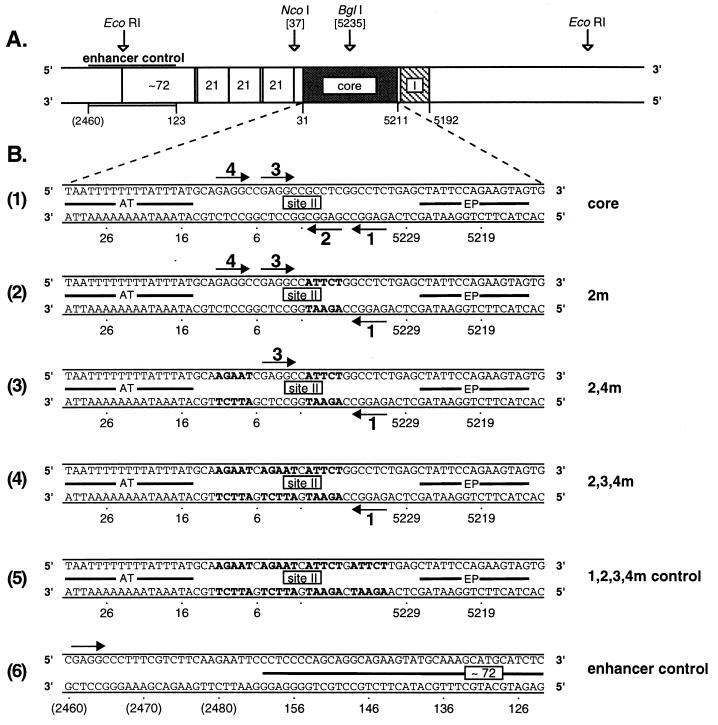

FIG. 1.

Map of the SV40 origin region and sequences of representative oligonucleotides used in this study. (A) The relative locations of the core origin (extending between nucleotides 5211 and 31) (20), T-ag binding site I, the 21-bp repeats, and a partial copy of one of the 72-bp enhancer elements are shown. Also indicated are the template positions from which the enhancer control oligonucleotide was derived (see below). SV40 nucleotides are numbered as described elsewhere (71). (This map is based on the SV40 origin sequences present in plasmid pSV01ΔEP [75].) (B) Representative oligonucleotides from the different pentanucleotide mutant classes are shown, along with the control oligonucleotides used in this study. Diagram D1 shows the DNA sequence of the 64-bp wild-type core origin. The arrows depict the four GAGGC pentanucleotide recognition sequences for T-ag within site II; the pentanucleotides are numbered as previously described (42). The locations of the AT-rich region and the EP region are also depicted. Diagram D2 shows a representative member of the single-pentanucleotide core origin mutations, 2m. Boldface letters, transition mutations replacing the GAGGC pentanucleotides. Additional members of this class had transition mutations in pentanucleotide 1, 3, or 4. Diagram D3 shows a representative member of the double-pentanucleotide core origin mutations, 2-4m (pentanucleotides 1 and 3 were intact). Five additional double-pentanucleotide mutations were synthesized (1-2, 1-3, 1-4, 2-3, 2-4, and 3-4). Diagram D4 shows a representative member of the triple-pentanucleotide core origin mutations, 2-3-4m. Three additional oligonucleotides, containing intact copies of pentanucleotides 2, 3, and 4, were also synthesized (1-3-4m, 1-2-4m, and 1-2-3m, respectively). Diagram D5 shows the sequence of an oligonucleotide used as a control in certain band shift assays (1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide). This DNA molecule contained transition mutations in all four pentanucleotides. Diagram D6 shows the 64-bp enhancer control oligonucleotide from the region depicted in panel A. The bar depicts DNA derived from the SV40 enhancer, while the location of a single GAGGC pentanucleotide is indicated by the arrow. The numbers in parentheses are non-SV40 sequences labeled according to the pSV01ΔEP numbering system (75).

KMnO4 footprinting.

Structural alterations in the core origin were monitored by use of the KMnO4 footprinting technique (7). Reaction mixtures (30 μl) contained 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 40 mM creatine phosphate (pH 7.6), 0.48 μg of creatine phosphate kinase, 5 μg of bovine serum albumin, 0.6 μg of HaeIII-digested φX174 RF DNA added as a nonspecific competitor, 320 ng of plasmid, and 1 μg of T-ag. After incubation of the reaction mixtures for 45 min at 37°C, 4 μl of 50 mM KMnO4 was added (final concentration, 6 mM), and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for an additional 4 min. The reactions were then quenched by the addition of 4 μl of β-mercaptoethanol, and the mixtures were diluted with 17 μl of water. Samples were purified by centrifugation over a Sephadex G-50 column preequilibrated in water.

For the primer extension reactions, oligonucleotide 1 (5′ TGAGCGGATACATATTTG 3′) (12) was 5′ end labeled with γ-32P-ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (60). The labeled primer was added to aliquots of the reaction mixtures (35 μl), and the plasmids were subsequently denatured by the addition of 4 μl of 50 mM NaOH (final concentration, 5 mM) and heating to 80°C for 2 min. The samples were neutralized with 4.5 μl of 10× extension buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.2], 10 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM DTT [final concentrations]). Oligonucleotide 1 was hybridized to the denatured plasmids by incubation at 52°C for 3 min, followed by a second incubation at 45°C for 3 min; the samples were allowed to cool to 35°C. dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP were each added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Each sample was moved to a 52°C bath, 1.0 U of Klenow fragment was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min. The reactions were quenched with EDTA (final concentration, 11 mM), and the DNA was precipitated by the addition of ammonium acetate to 0.75 M and an ∼3× volume of 100% (vol/vol) ethanol. After being washed with 80% (vol/vol) ethanol, the samples were electrophoresed on 7% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea for 3 h at 1,500 V and 40 mA. A dideoxy sequencing ladder with oligonucleotide 1 as a primer was used to establish the locations of the modified residues.

Unwinding assay.

T-ag-dependent unwinding assays with HeLa cell crude extracts were conducted according to the procedure of Bullock et al. (11). Reactions were performed under replication conditions (75), and reaction mixtures (60 μl) contained 30 μl of HeLa cell crude extracts (∼12.3 mg/ml), 2.0 μg of T-ag, and 0.75 μg of plasmid. The reaction mixtures were preincubated for 45 min at 37°C in the absence of T-ag and then further incubated for 15 min upon the addition of 2 μg of T-ag. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 6 μl of stop mixture (12 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.015 mg of tRNA per ml, 0.25 mg of N-laurylsarcosine per ml, 0.41 mg of proteinase K per ml [final concentrations]), and the reaction mixtures were further incubated at 37°C for 25 min. Proteins were removed by phenol-chloroform extraction, and the DNA was precipitated by the addition of an equal volume of 5 M ammonium acetate and 3 volumes of 100% (vol/vol) ethanol. DNA pellets were washed with 80% (vol/vol) ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.8)–1 mM EDTA–5 μl of gel loading buffer (20% [vol/vol] Ficoll, 0.1 M EDTA, 0.25% bromophenol blue, 0.25% xylene cyanol FF). Samples were electrophoresed through 1.8% agarose gels containing chloroquine (1.5 μg/ml) and Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (60) for 14 h at 2.8 V/cm. The gels were processed for photography as described previously (11).

RESULTS

Pentanucleotide requirements for T-ag hexamer formation.

A diagram of the SV40 origin region is presented in Fig. 1A. The core origin is flanked by regions, including site I and the 21-bp repeats, that stimulate DNA synthesis in vivo (25); whether they also stimulate DNA synthesis in vitro is controversial (10). Nevertheless, the SV40 core origin is necessary and sufficient for the initiation of SV40 replication both in vivo and in vitro (10, 23, 26, 43, 54, 68). The sequence of an oligonucleotide containing the 64-bp SV40 core origin is presented in Fig. 1B (diagram 1). Site II contains four GAGGC pentanucleotides arranged as two pairs that are inverted relative to each other. Site II is flanked by the EP and AT-rich regions.

To establish the pentanucleotide requirements for hexamer and double-hexamer formation, oligonucleotides containing various subsets of the normal complement of four pentanucleotides were synthesized. A representative of the single-pentanucleotide mutant class of oligonucleotides, 2m, is presented in Fig. 1B (diagram 2). During the synthesis of this oligonucleotide, transition mutations were introduced at position 2 in both DNA strands. However, the remaining sequences were identical to those normally present in the wild-type core origin. In a second class of core origin mutants, transition mutations were introduced at different pairs of pentanucleotides (the six double-pentanucleotide mutants, 1-2m, 1-3m, 1-4m, 2-3m, 2-4m, and 3-4m). A representative of this class of oligonucleotides, 2-4m, is presented in Fig. 1B (diagram 3). A third set of 64-bp core origin mutants in which transition mutations were introduced at three of the four pentanucleotides was synthesized. A representative of these triple-pentanucleotide mutants, 2-3-4m, is presented in Fig. 1B (diagram 4). Figure 1B also presents two control oligonucleotides used in this study. In one molecule, 1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B [diagram 5]), all four pentanucleotides were mutated. The second 64-bp control oligonucleotide included a significant portion of the SV40 enhancer (Fig. 1A); therefore, this oligonucleotide was termed the enhancer control oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B [diagram 6]).

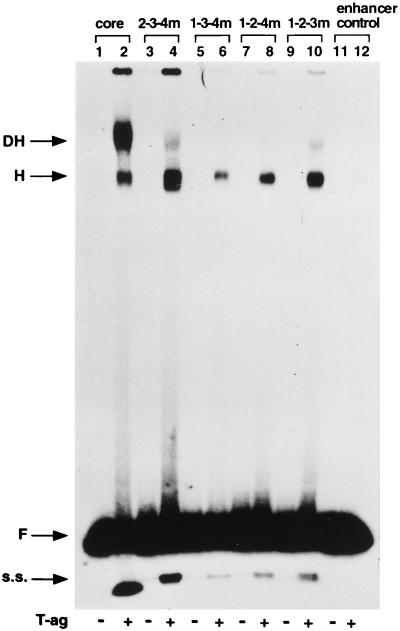

To examine oligomerization events on mutant origins containing single pentanucleotides, the four triple-pentanucleotide mutants (Fig. 1B [diagram 4]) were used in a series of band shift reactions conducted under replication conditions (Fig. 2). As a positive control, a band shift reaction was performed with T-ag and the wild-type 64-bp core oligonucleotide (Fig. 2, lane 2). The two products formed in this reaction were previously characterized (15, 59, 74); they include T-ag hexamers (faster-migrating complex labeled H) and double hexamers (slower-migrating complex labeled DH). These assignments were confirmed by native gel electrophoresis techniques (15, 44, 59) (data not presented). The products formed when the triple-pentanucleotide mutants were used in identical reactions are shown in Fig. 2, lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10. It is apparent that all four triple-pentanucleotide mutants supported the formation of T-ag hexamers. It is also apparent that the oligonucleotide containing pentanucleotide 1 supported the largest amount of hexamer formation (Fig. 2, lane 4) and that hexamer formation was weakest on pentanucleotide 2 (lane 6). Quantitation with a PhosphorImager of four identical experiments indicated that the relative abilities of the individual pentanucleotides to support hexamer formation were 1 > (4, 3) > 2. Moreover, oligonucleotides containing pentanucleotides 1 (Fig. 2, lane 4) and 4 (lane 10) also supported the formation of relatively small amounts of a species that comigrated with the double hexamers formed on the wild-type core origin (Fig. 2, lane 2 [discussed below]). The products formed in reactions containing the 64-bp enhancer control oligonucleotide are shown in Fig. 2, lane 12. (The products formed with the 1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide are shown in Fig. 3C.) Quantitation studies indicated that the amount of hexamer formed on the enhancer control oligonucleotide (data not shown) was ∼6.0% the amount of hexamer formed on 2-3-4m (Fig. 2, lane 4) and ∼20% that formed on 1-3-4m (lane 6). Finally, the odd-numbered lanes in Fig. 2 contained the products formed when the band shift experiments were conducted in the absence of T-ag. It was concluded that comparable levels of T-ag hexamers form on oligonucleotides containing either the wild-type core origin or mutant molecules containing single pentanucleotides present in otherwise complete core origins.

FIG. 2.

Representative gel mobility assay used to assess T-ag oligomerization on the triple-pentanucleotide mutants. As a positive control, a band shift reaction was conducted with T-ag (∼0.5 μg) and the 64-bp core oligonucleotide (lane 2). Reaction products formed with T-ag and 2-3-4m (pentanucleotide 1 intact), 1-3-4m (pentanucleotide 2 intact), 1-2-4m (pentanucleotide 3 intact), and 1-2-3m (pentanucleotide 4 intact) are presented in lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10, respectively. The products formed with the enhancer control oligonucleotide and T-ag are presented in lane 12. The products of band shift reactions conducted in the absence of T-ag and the indicated oligonucleotides are presented in the odd-numbered lanes. The arrows indicate the positions of T-ag hexamers (H), T-ag double hexamers (DH), free DNA (F), and single-stranded DNA (s.s.) generated as a result of the helicase activity of T-ag (17, 32, 66). The reactions were performed at a T-ag/oligonucleotide ratio of 120:1.

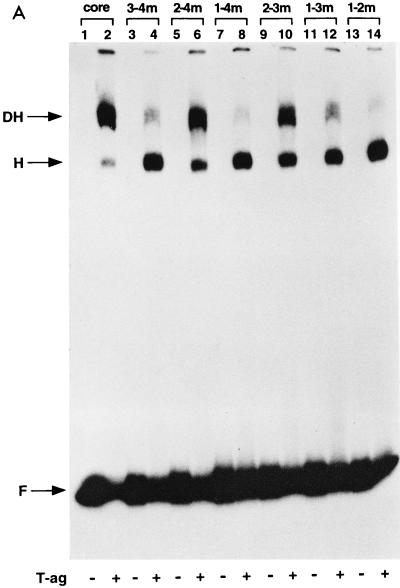

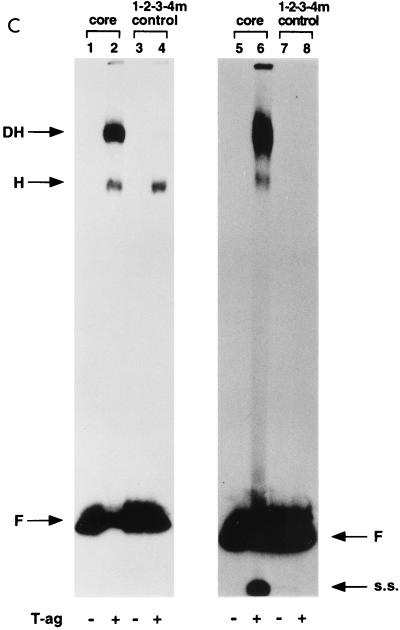

FIG. 3.

Representative gel mobility shift assays used to assess T-ag oligomerization on the double-pentanucleotide mutants. (A) This set of reactions was conducted in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable analog of ATP, AMP-PNP. As a positive control, a band shift reaction was conducted with the 64-bp core oligonucleotide and T-ag (lane 2). Reaction products formed with T-ag (∼0.25 μg) and mutants 3-4m (pentanucleotides 1 and 2 intact), 2-4m (pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact), 1-4m (pentanucleotides 2 and 3 intact), 2-3m (pentanucleotides 1 and 4 intact), 1-3m (pentanucleotides 2 and 4 intact), and 1-2m (pentanucleotides 3 and 4 intact) are presented in lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14, respectively. The products of band shift reactions conducted in the absence of T-ag and the indicated oligonucleotides are presented in the odd-numbered lanes. (B) These reactions are identical to those shown in panel A, except that they were performed in the presence of ATP rather than AMP-PNP. As in panel A, the reactions in the even-numbered lanes were conducted in the presence of T-ag, while those in the odd-numbered lanes were conducted in the absence of T-ag. The even-numbered lanes contained single-stranded (s.s.) DNA generated as a result of the helicase activity of T-ag (17, 32, 66). (C) Double-hexamer assembly in the absence of pentanucleotides was analyzed with the 64-bp 1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide. As in previous experiments, double-hexamer formation on the 64-bp core oligonucleotide served as a positive control (lanes 2 and 6). Band shift reactions conducted with T-ag and 1-2-3-4m are presented in lanes 4 and 8. The experiments presented in lanes 1 to 4 were conducted in the presence of AMP-PNP, while those in lanes 5 to 8 were conducted in the presence of ATP. Reactions presented in odd-numbered lanes were conducted in the absence of T-ag. The arrows indicate the positions of T-ag hexamers (H), T-ag double hexamers (DH), free DNA (F), and single-stranded DNA (s.s.). Finally, the reactions were conducted at a T-ag/oligonucleotide ratio of 60:1; however, nearly identical results were obtained at a ratio of 120:1.

Pentanucleotide requirements for T-ag double-hexamer formation.

In a related series of experiments, the double-pentanucleotide mutants (Fig. 1B [diagram 3]) were used in a series of band shift reactions. These reactions were performed at different protein/oligonucleotide ratios (e.g., 120:1 and 60:1) and under various reaction conditions (see below). Results from a representative experiment, conducted at a protein/oligonucleotide ratio of 60:1, are presented in Fig. 3A. To provide an accurate measure of hexamer and double-hexamer formation, these experiments were conducted in the presence of AMP-PNP; this nonhydrolyzable analog of ATP prevents the loss of T-ag–DNA complexes caused by the helicase activity of T-ag (17, 32, 66). As a positive control, a reaction was conducted with T-ag and the 64-bp core oligonucleotide; the products of this reaction, T-ag hexamers and double hexamers, are displayed in Fig. 3A, lane 2. The complexes formed in reactions with T-ag and the double-pentanucleotide mutants are shown in Fig. 3A, lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14. As with the triple-pentanucleotide mutants, it is apparent that the double-pentanucleotide mutants were capable of engendering the formation of T-ag hexamers (H). It is also apparent that certain double-pentanucleotide mutants (e.g., 2-4m [Fig. 3A, lane 6; pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact] and 2-3m [lane 10; pentanucleotides 1 and 4 intact]) supported T-ag double-hexamer (DH) formation at levels comparable to those formed on the core origin. Other pentanucleotide pairs supported intermediate levels of double-hexamer formation (e.g., 3-4m [Fig. 3A, lane 4; pentanucleotides 1 and 2 intact] and 1-3m [lane 12; pentanucleotides 2 and 4 intact]), while others supported the formation of double hexamers at very low levels (e.g., 1-4m [lane 8; pentanucleotides 2 and 3 intact] and 1-2m [lane 14; pentanucleotides 3 and 4 intact]). The odd-numbered lanes contained the products formed when the band shift experiments were conducted in the absence of T-ag.

The band shift experiments were repeated in the presence of ATP rather than AMP-PNP (Fig. 3B). The reaction products formed in the presence of T-ag and the core origin are displayed in Fig. 3B, lane 2, while those formed in reactions with the double-pentanucleotide mutants (Fig. 1B [diagram 3]) are shown in lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14. In all instances, the products formed were qualitatively very analogous to those formed in the presence of AMP-PNP. However, since single-stranded DNA is generated in the presence of ATP as a consequence of the helicase activity of T-ag (17, 32, 66), it is difficult to accurately measure the amounts of double hexamers formed under these conditions. As in Fig. 3A, the odd-numbered lanes contained the products of band shift reactions conducted in the absence of T-ag. The experiments presented in Fig. 3B confirmed that certain pentanucleotide pairs (e.g., pentanucleotides 1 and 3 [lane 6] and 1 and 4 [lane 10]) supported T-ag double-hexamer formation.

Under replication conditions, the triple-pentanucleotide and double-pentanucleotide mutants generated similar amounts of single-stranded DNA. In view of this result, it was concluded that a single hexamer is sufficient for this activity. However, the biological significance of this reaction is questionable, given that all four pentanucleotides are required for the unwinding of circular molecules (16) (see below). Moreover, it has been reported that the topological requirements for unwinding short linear DNAs are different from those for unwinding circular DNA molecules (76).

A previous study indicated that T-ag is capable of low levels of interaction with the EP (57). Therefore, the EP containing the 1-2-3-4m oligonucleotide was used to measure the amount of pentanucleotide-independent double-hexamer formation occurring under these reaction conditions. As a positive control, band shift reactions were conducted with T-ag and the core oligonucleotide in the presence of either AMP-PNP (Fig. 3C, lane 2) or ATP (lane 6). Inspection of Fig. 3C, lane 4, demonstrates that in the presence of T-ag and AMP-PNP, the 1-2-3-4m oligonucleotide supported hexamer formation; however, negligible levels of double hexamers were detected (for quantitation, see Table 1). The products formed in similar reactions with T-ag, ATP, and the 1-2-3-4m oligonucleotide are presented in Fig. 3C, lane 8. The presence of ATP reduced the amounts of hexamers and double hexamers formed in these reactions; however, since single-stranded DNA was not detected in Fig. 3C, lane 8, the reduction could not be attributed to the helicase activity of T-ag. As in previous examples, reactions in the odd-numbered lanes were conducted in the absence of T-ag. These studies demonstrated that the AT-rich and EP regions did not independently support double-hexamer formation.

TABLE 1.

Quantitation of T-ag double-hexamer formation on oligonucleotides containing the wild type or double-pentanucleotide mutantsa

| Oligonucleotide | AMP-PNP

|

ATP

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH (%) | DH (mutant)/ DH (core) | DH (%) | DH (mutant)/ DH (core) | |

| Core | 48 | 16 | ||

| 3-4m | 10 | 0.21 | 2.2 | 0.14 |

| 2-4m | 29 | 0.60 | 7.8 | 0.49 |

| 1-4m | 2.6 | 0.054 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

| 2-3m | 18 | 0.38 | 2.4 | 0.15 |

| 1-3m | 8.4 | 0.18 | 1.8 | 0.11 |

| 1-2m | 4.6 | 0.10 | 1.3 | 0.08 |

| Core | 48 | 25 | ||

| 1-2-3-4m control | 1.2 | 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

The experiments presented in Fig. 3A (performed in the presence of AMP-PNP), Fig. 3B (performed in the presence of ATP), and Fig. 3C (control reactions conducted in the presence of AMP-PNP and ATP) were quantitated with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Values presented for the first seven oligonucleotides for AMP-PNP were derived from Fig. 3A, those presented for these oligonucleotides for ATP were derived from Fig. 3B, and those presented for the last two oligonucleotides for AMP-PNP and ATP were derived from Fig. 3C. For a given lane in Fig. 3A to C, the percentage of total DNA present in the double-hexamer (DH) species was determined. The relative abilities of the double-pentanucleotide mutants to support DH formation were determined by dividing the values for the double-pentanucleotide mutants by the value for the wild type.

Results from PhosphorImager quantitation of the experiments presented in Fig. 3 are presented in Table 1. In the presence of either AMP-PNP or ATP, the relative abilities of the double-pentanucleotide mutants to support double-hexamer formation were 2-4m > 2-3m > 3-4m > 1-3m > 1-2m > 1-4m (pentanucleotides 1 and 3, 1 and 4, 1 and 2, 2 and 4, 3 and 4, and 2 and 3 intact, respectively). Pentanucleotides 1 and 3 were clearly the best at supporting double-hexamer formation (2-4m; in the presence of AMP-PNP, supporting 60% of the wild-type result). Conversely, other pentanucleotide pairs, such as pentanucleotides 2 and 3, were clearly defective in the formation of T-ag double hexamers (1-4m; in the presence of AMP-PNP, supporting only 5% of the wild-type result). As previously noted, the extent of double-hexamer formation in the presence of ATP was somewhat lower than that in the presence of AMP-PNP. This result can be explained, in part, by a reduction in the double-hexamer population caused by the ATP-dependent helicase activity of T-ag. Finally, although T-ag is known to interact with the EP in the absence of pentanucleotides (57), it is clear that, under these reaction conditions, double-hexamer formation on the 1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide was limited.

Footprinting studies of T-ag double hexamers assembled on the SV40 core origin.

Of considerable interest, T-ag hexamers formed on the four-pentanucleotide-containing core origin comigrated with hexamers formed on the single-pentanucleotide containing triple-pentanucleotide mutants (Fig. 2). Moreover, double hexamers formed on the core origin comigrated with those formed on the double-pentanucleotide mutants (Fig. 3A and B). These observations raised the possibility that even on the core origin, hexamers assemble on single pentanucleotides, while double hexamers assemble on selected pairs of pentanucleotides.

To test this hypothesis, the gel retardation—1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion footprinting procedure was used (40); this technique permits protein-DNA complexes to be footprinted within the gel matrix. After purification, the resulting DNA fragments are resolved on sequencing gels. This technique was previously used to demonstrate that T-ag-obd131-260 does not simultaneously protect all four pentanucleotides in the wild-type core origin (37). These experiments also demonstrated that T-ag-obd131-260 prefers to bind to pentanucleotides 1 and 3 (37). Therefore, similar footprinting experiments were initiated to more clearly define the interaction of T-ag double hexamers with the core origin.

In one experiment, double hexamers formed on the 64-bp core oligonucleotide and the 2-4m oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B [diagram 3]; pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact) were analyzed. In both instances, the oligonucleotides were asymmetrically labeled (see Materials and Methods) at the 5′ termini of the top strands (Fig. 1B). As a control, band shift reactions were conducted with the same oligonucleotides and T-ag-obd131-260. Inspection of Fig. 4, lane 6, reveals that double hexamers formed on the 64-bp core oligonucleotide under replication conditions protected an ∼18- to 19-nucleotide region (roughly the distance spanning three pentanucleotides (Fig. 1B [diagram 1]). Surprisingly, a nearly identical region was protected by T-ag-obd131-260 (Fig. 4, lane 5). In both instances, the protected region extended between pentanucleotide 3 and a region containing sequences complementary to pentanucleotide 1. Regarding pentanucleotide 4, with T-ag-obd131-260 (Fig. 4, lane 5), the footprint did not extend over this region. Moreover, within the T-ag double hexamers (Fig. 4, lane 6), pentanucleotide 4 was largely unprotected. However, since this region was somewhat less intense than the corresponding region in Fig. 4, lane 5, limited protection of this pentanucleotide might occur as a result of double-hexamer formation.

FIG. 4.

In situ footprinting of T-ag double-hexamer–core origin complexes with the nuclease activity of 1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion. Lanes 1 and 4 contain the products of control reactions conducted with free DNA isolated from samples containing the 2-4m and 64-bp core oligonucleotides, respectively. Lanes 3 and 6 contain the products of footprinting reactions conducted with the same oligonucleotides but isolated from T-ag double-hexamer complexes. For comparison, lanes 2 and 5 contain the products of footprinting reactions conducted with T-ag-obd131-260 and the same pair of oligonucleotides. Size markers were generated by subjecting the indicated oligonucleotides to the G and G+A sequencing reactions described by Maxam and Gilbert (49). Flanking each panel is a map of the relative positions of the EP region, pentanucleotides 1 to 4 (arrows), and the AT-rich region. The arrows with the smaller heads represent the complementary sequences of a given pentanucleotide. The experiments were conducted at a 120:1 protein (either T-ag or T-ag-obd131-260)/oligonucleotide ratio. The oligonucleotides were asymmetrically labeled on the top strands (Fig. 1B).

Figure 4, lane 3, presents the DNA ladder obtained when the double hexamers formed on the 2-4m oligonucleotide (pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact) were analyzed via the gel retardation–1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion footprinting technique. When compared with Fig. 4, lane 6, it is apparent that nearly identical regions of site II were protected in the 2-4m and core origin oligonucleotides. It is also apparent that the DNA region containing the transition mutations in pentanucleotide 4 was not protected in the 2-4m oligonucleotide. Figure 4, lane 2, presents the DNA ladder obtained when T-ag-obd131-260 bound to 2-4m was analyzed via the gel retardation–1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion footprinting technique. A comparison of Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3, provides additional evidence that T-ag double hexamers and T-ag-obd131-260 protected very similar regions of DNA. Finally, control DNA reactions (i.e., oligonucleotides treated with 1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion and isolated from reaction mixtures lacking T-ag or T-ag-obd131-260) are presented in Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 4. As previously noted (37), incomplete cleavage of certain regions within the control DNAs might be related to a bias in the sequence preferences exhibited by 1,10-phenanthroline–copper (73).

The footprinting experiments were repeated with the same oligonucleotides asymmetrically labeled on the bottom strands (Fig. 1B) (data not presented). With the 64-bp core oligonucleotide, the footprint extended between pentanucleotide 1 and the complement of pentanucleotide 3. As with the top strands, protection over pentanucleotide 1 was incomplete; faint bands were detected in the EP-proximal region of pentanucleotide 1. Similar results were obtained with 2-4m. Additional studies demonstrated that, as with the top strands, the footprints obtained with T-ag-obd131-260 and T-ag double hexamers were very similar.

Collectively, the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion footprinting studies indicated that T-ag double hexamers do not simultaneously bind to all four pentanucleotides. This conclusion is based on the limited protection of pentanucleotide 4 and the observation that the presence or absence of pentanucleotide 2 had a negligible impact on the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper ion footprint. Moreover, they demonstrated that under replication conditions, both T-ag double hexamers and T-ag-obd131-260 preferentially occupied pentanucleotides 1 and 3; the same conclusion was drawn from previous studies with T-ag- obd131-260 (37).

Finally, with regard to the double-hexamer species detected at low levels on pentanucleotides 1 and 4 (Fig. 2), it is likely that they resulted from nonspecific protein-protein interactions with hexamers bound to individual pentanucleotides. Consistent with this proposal, 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting ion studies indicated that only a single pentanucleotide was protected in these double-hexamer complexes (65a).

Structural consequences of double-hexamer formation on particular double-pentanucleotide mutants.

Whether the double hexamers formed on particular pairs of pentanucleotides were active was addressed by determining if they catalyzed certain previously described DNA structural changes (7, 57). On circular templates containing the wild-type origin, the structural changes included an untwisting of the AT-rich tract (5, 7, 57) and melting of approximately 8 bp within one arm of the EP (7, 57). Therefore, KMnO4 oxidation assays (7) were used to detect these structural changes in plasmids containing the double-pentanucleotide mutants.

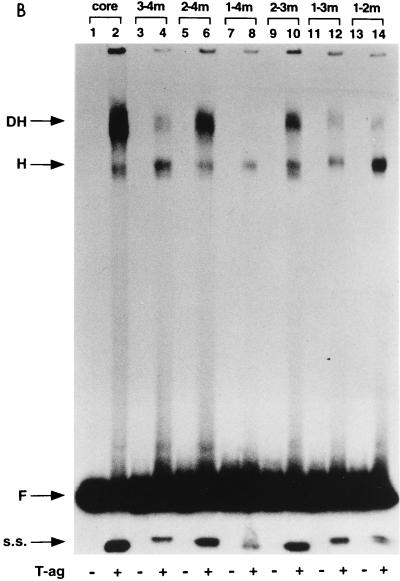

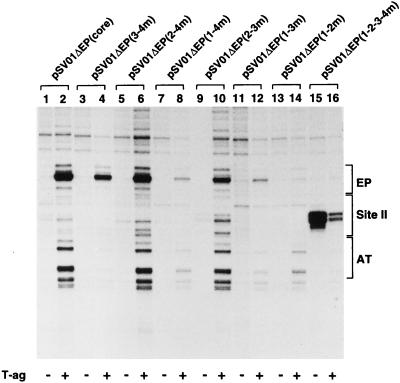

When plasmid pSV01ΔEP(core) was used in the KMnO4 assays, the previously described structural distortions in the AT-rich and EP regions were detected (Fig. 5, lane 2). The products of identical reactions conducted with pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide mutants are presented in Fig. 5, lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14. In certain instances, such as with pSV01ΔEP(2-4m) (Fig. 5, lane 6; pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact) and, to a lesser extent, pSV01ΔEP(2-3m) (lane 10; pentanucleotides 1 and 4 intact), a wild-type oxidation pattern was observed. In other instances, structural distortions were detected in only one of the flanking regions. For example, with pSV01ΔEP(3-4m) (Fig. 5, lane 4; pentanucleotides 1 and 2 intact), structural modifications were detected only over the EP region. Likewise, with pSV01ΔEP(1-2m) (Fig. 5, lane 14; pentanucleotides 3 and 4 intact), structural modifications were detected only over the AT-rich region. With other pentanucleotide mutants, such as pSV01ΔEP(1-4m) (Fig. 5, lane 8; pentanucleotides 2 and 3 intact) or pSV01ΔEP(1-3m) (lane 12; pentanucleotides 2 and 4 intact), there were limited structural distortions in the EP or AT-rich regions. The structural distortions observed with the plasmid containing the 1-2-3-4m control oligonucleotide, pSV01ΔEP(1-2-3-4m), are presented in Fig. 5, lane 16. Structural distortions in the AT-rich and EP regions were not detected with this molecule. However, a pronounced, T-ag-independent structural distortion was detected over the region containing the mutant pentanucleotides. The basis for the structural distortion over this region is not currently understood. The products of reactions conducted in the absence of T-ag are presented in the odd-numbered lanes. In summary, the structural distortions observed upon T-ag binding to plasmids containing the double-pentanucleotide mutants were complex (see Discussion). Nevertheless, it is clear that the double-pentanucleotide mutants that enabled significant levels of double-hexamer formation (Fig. 3A and B and Table 1) also supported nearly wild-type levels of structural distortions in the AT-rich and EP regions.

FIG. 5.

Ability of pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide mutants to catalyze T-ag-dependent structural changes in the core origin. T-ag (1 μg) was incubated under replication conditions with pSV01ΔEP(core) (lane 2), pSV01ΔEP(3-4m) (lane 4), pSV01ΔEP(2-4m) (lane 6), pSV01ΔEP(1-4m) (lane 8), pSV01ΔEP (2-3m) (lane 10), pSV01ΔEP(1-3m) (lane 12), pSV01ΔEP(1-2m) (lane 14), or pSV01ΔEP(1-2-3-4m) (lane 16). (In all reactions, the T-ag/plasmid ratio was ∼60:1.) Reactions in odd-numbered lanes were conducted with the indicated plasmids in the absence of T-ag. After treatment with KMnO4, the sites of oxidation were probed by primer extension reactions with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide 1 (see Materials and Methods). The primer extension products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 7% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. The locations of the EP, site II, and AT-rich elements are shown on the right.

Determining the ability of pSV01ΔEP pentanucleotide mutants to support T-ag-dependent unwinding.

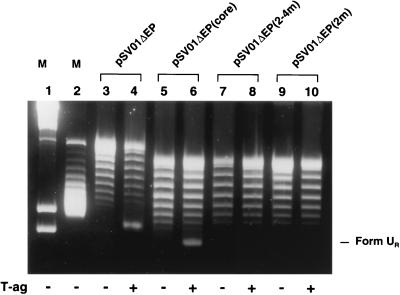

In view of the results obtained in the previous assays, it was of interest to determine whether T-ag-dependent unwinding could be detected with plasmids containing transition mutations in various pentanucleotides. Therefore, the pSV01ΔEP double- and single-pentanucleotide mutants were used in unwinding assays along with the control plasmids, pSV01ΔEP and pSV01ΔEP(core) (11, 17, 28). The topological isomers formed with these plasmids after 15 min of incubation in HeLa cell crude extracts under replication conditions (see Materials and Methods) are shown in Fig. 6, lanes 3 to 10. The formation of the previously described species, Form UR (11), with pSV01ΔEP and 2 μg of T-ag is shown in Fig. 6, lane 4. The extent of Form UR formation with pSV01ΔEP(core) is indicated in Fig. 6, lane 6. The similar levels of Form UR formation with these two plasmids confirm previous reports (10 and references therein) that, under these conditions, SV40 sequences flanking the core origin (e.g., site I, the 21-bp repeats, and the enhancer sequences [Fig. 1A]) do not promote DNA unwinding. The topological isomers formed when pSV01ΔEP(2-4m) was used in identical unwinding reactions are presented in Fig. 6, lane 8; it is clear that Form UR was not detected in this reaction. Identical results were obtained with pSV01ΔEP(3-4m) and pSV01ΔEP(1-3m) (data not shown). Additional studies were conducted with pSV01ΔEP single-pentanucleotide mutants. These experiments were initiated, in part, to determine whether asymmetric unwinding could be detected with three intact pentanucleotides. The topological isomers generated when pSV01ΔEP(2m) was used in an unwinding assay are presented in Fig. 6, lane 10. As with pSV01ΔEP(2-4m), no Form UR was detected with pSV01ΔEP(2m). Identical results were obtained with pSV01ΔEP(1m) (data not shown). The reactions in the odd-numbered lanes were conducted in the absence of T-ag with the indicated plasmids. It was concluded that under these reaction conditions, all four pentanucleotides are required for DNA unwinding.

FIG. 6.

Determination of the relative abilities of the pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide and pSV01ΔEP single-pentanucleotide mutants to support T-ag-dependent unwinding. Samples were analyzed by electrophoreses on a 1.8% agarose gel containing chloroquine (1.5 μg/ml); markers (lanes M) contained restriction fragments generated by cleavage of bacteriophage lambda with HindIII (lane 1; the lower fragment is 2,027 bp and the upper fragment is 2,322 bp) and Form I pSV01ΔEP (lane 2). The topological isomers produced after 15 min of incubation in HeLa cell crude extracts in the presence or absence of T-ag with pSV01ΔEP (lanes 3 and 4), pSV01ΔEP(core) (lanes 5 and 6), pSV01ΔEP(2-4m) (lanes 7 and 8), and pSV01ΔEP(2m) (lanes 9 and 10) are presented. Reactions in lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10 were conducted in the presence of T-ag (2 μg); those in lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9 were conducted in the absence of T-ag. The position of Form UR, formed in the reaction containing pSV01ΔEP(core), is indicated. The amount of Form UR generated by pSV01ΔEP(core) is the same as or near the amount produced by pSV01ΔEP. Unwinding reactions were conducted at T-ag/plasmid ratios of 60:1.

DISCUSSION

Since there are four pentanucleotides in the core origin and hexamer formation is supported by single pentanucleotides, one might predict that four hexamers assemble on the SV40 core origin. However, previous studies demonstrated that T-ag oligomerization on the SV40 core origin is limited to double-hexamer formation (47, 48, 59, 74). Moreover, in this study, we demonstrated that mutant origins containing particular pairs of pentanucleotides are sufficient for the assembly of T-ag double hexamers. One proposal consistent with these observations is that T-ag double hexamers do not simultaneously bind to the four pentanucleotides within the SV40 core origin.

This hypothesis is supported by the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting studies. Based on these experiments, it was concluded that under replication conditions, all four pentanucleotides in the core origin are not simultaneously occupied. These experiments also demonstrated that, upon oligomerization on the core origin in the presence of ATP, T-ag preferentially occupied pentanucleotides 1 and 3. Moreover, when bound to pentanucleotides 1 and 3, T-ag double hexamers protected a region of DNA quite similar to that protected by T-ag-obd131-260. These studies suggest that T-ag-obd131-260, either purified or in the context of a full-length T-ag molecule, makes very similar contacts with the core origin. This suggestion is surprising when one considers not only the size differences between these two molecules but also the differences in their posttranslational modifications. For example, a high percentage of T-ag molecules isolated from baculovirus expression vectors are phosphorylated at residues (e.g., Thr 124) (34) critical for unwinding (50, 52), while T-ag-obd131-260 molecules isolated from Escherichia coli are not phosphorylated.

Whether the double hexamers formed on particular pentanucleotide pairs were functional was addressed with the KMnO4 oxidation assay. These experiments demonstrated that the structural distortions in the AT-rich and EP regions were induced by T-ag binding to certain pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide mutants. Generation of the wild-type structural alterations depended on the pentanucleotide pairs being arranged in a head-to-head orientation and situated on opposite strands of DNA {e.g., pentanucleotides 1 and 3 intact [pSV01ΔEP(2-4m)] or pentanucleotides 1 and 4 intact [pSV01ΔEP(2-3m)]}. It is apparent that by these criteria, the T-ag double hexamers formed on particular pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide mutants were active. Furthermore, there was a direct correlation between the ability of individual pentanucleotide pairs to support high levels of double-hexamer formation (Fig. 3A and B and Table 1) and their ability to promote wild-type structural distortions in the AT-rich and EP regions in circular DNA molecules (Fig. 5).

Regarding the structural changes induced by T-ag binding to the pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide mutants that supported hexamer but not double-hexamer formation, those containing pentanucleotides arranged in a head-to-tail orientation (e.g., pentanucleotides 1 and 2 or pentanucleotides 3 and 4 [Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 14, respectively]) induced significant structural changes only in the proximal flanking element. Since pentanucleotide pairs arranged in a head-to-tail manner are on a single strand of DNA, the failure to alter the distal flanking element may reflect limited protein-DNA interactions with the second strand of DNA. While this possibility remains to be proved, it is clear from these studies that the alterations in the flanking sequences are independent events, a conclusion consistent with previous studies (3, 5, 58, 59).

Since particular double-pentanucleotide mutants were able to support both T-ag double-hexamer formation and the structural alterations in the AT-rich and EP regions (e.g., pentanucleotides 1 and 3), it was of interest to determine whether they also supported extensive DNA unwinding (11, 17, 28). The unwinding assays demonstrated that both the pSV01ΔEP double-pentanucleotide and the pSV01ΔEP single-pentanucleotide mutants were defective in their ability to support DNA unwinding. These experiments confirmed an earlier report that all four pentanucleotides are required for DNA unwinding and initiation of SV40 replication (16). Therefore, it is likely that the initially unoccupied pair of pentanucleotides in the SV40 core origin is required at a stage in the initiation process between double-hexamer formation and initiation of unwinding. What role is played by the second set of pentanucleotides during the initiation of DNA unwinding on circular DNA molecules is currently not known.

While similar, the pentanucleotide requirements for T-ag and T-ag-obd131-260 binding to the double-pentanucleotide mutants are not identical. For example, mutant origins containing pentanucleotides 1 and 4 supported double-hexamer formation (Fig. 3) but not stable binding of T-ag-obd131-260 (37). Moreover, whereas T-ag-obd131-260 readily bound to a mutant origin containing pentanucleotides 2 and 4, the same mutant origin was not a particularly good substrate for double-hexamer formation, particularly in the presence of ATP (Fig. 3B). While these differences in binding to the pentanucleotide mutants are not understood, protein-protein interactions may account for some of the differences. For example, owing to their size, T-ag molecules bound to pentanucleotides 1 and 4 may be able to make protein-protein contacts that cannot be made by T-ag-obd131-260 molecules bound to the same sites. Nevertheless, with these exceptions, the pentanucleotide requirements for T-ag double-hexamer formation and stable binding of T-ag-obd131-260 to site II are quite similar. Moreover, in contrast to the pentanucleotide mutants, both T-ag-obd131-260 and T-ag interact with the wild-type core origin in remarkably similar ways. For instance, under replication conditions, both preferentially associate with pentanucleotides 1 and 3 and protect similar regions of DNA.

In previous experiments, the interaction between T-ag and the SV40 core origin was probed by both enzymatic and chemical means. DNase I-based footprinting experiments demonstrated that in the presence of ATP, T-ag protected a region that extended over the entire core origin (6, 7, 22, 57, 58). The larger size of the DNase I footprint relative to the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprint may simply reflect a steric clash between DNase I and T-ag double hexamers. A related possibility is that regions of T-ag not in contact with site II may extend over the flanking regions and protect them from DNase I but not from the oxygen radicals generated by 1,10-phenanthroline–copper (72). Consistent with this proposal, previous studies with various chemical probes (e.g., dimethyl sulfate, diethyl sulfate, hydrazine, and formic acid) revealed that T-ag makes very few contacts with regions flanking site II (7, 36, 57, 63). Nevertheless, since all three core origin domains are important in the assembly of T-ag double hexamers (3, 59), the contacts made with the flanking regions are likely to be very important for oligomerization events.

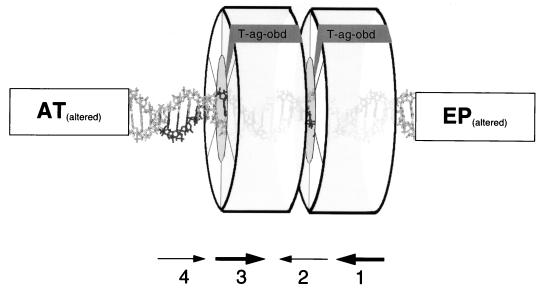

A model depicting the docking of two T-ag-obd131-260 molecules to the core origin was previously reported (37). According to this model, active pairs of pentanucleotides and molecules bound to these sites are on the same B-DNA face. It was suggested that the formation of T-ag double hexamers is nucleated, in part, by interactions between properly orientated T-ag-obd131-260 molecules (37). Results from the characterization of the interactions of T-ag with the core origin suggest an extension of the original model that is presented in Fig. 7. According to this model, under replication conditions, two T-ag monomers preferentially occupy pentanucleotides 1 and 3 via T-ag-obd131-260 molecules (Fig. 4). With T-ag, it is assumed that subsequent protein-protein interactions give rise to two T-ag hexamers that encircle the DNA. It was previously reported that T-ag assembly on the core origin is cooperative (e.g., see reference 53) and that hexamer assembly on the early half of the origin triggers cooperative assembly on the late half of the origin (59). Evidence that both strands are within the double hexamer include the observation that similar 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprints are detected on either strand of DNA. One consequence of T-ag double-hexamer formation is suggested by the model in Fig. 7; oligomerization may block further assembly events on unoccupied pentanucleotides (e.g., pentanucleotide 2), a suggestion consistent with the 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting studies.

FIG. 7.

Model depicting T-ag double-hexamer formation on the SV40 core origin. The band shift and 1,10-phenanthroline–copper footprinting experiments indicated that under replication conditions, T-ag double hexamers preferentially occupy pentanucleotides 1 and 3. (The pentanucleotides are symbolized by the arrows below the figure and by bold type in the DNA duplex.) Furthermore, the KMnO4 footprinting studies demonstrated that double-hexamer formation on pentanucleotides 1 and 3 (as well as pentanucleotides 1 and 4) induces the previously described structural alterations in the AT-rich and EP regions (7, 57). It is assumed that after an initial T-ag monomer interaction with a given pentanucleotide, via T-ag-obd131-260 (shown in gray), subsequent protein-protein interactions gave rise to mature hexamers.

Double hexamers formed on appropriately arranged pentanucleotide pairs catalyze the structural alterations in the AT-rich and EP regions; however, they do not support extensive DNA unwinding. These findings indicate that occupancy of the second pair of pentanucleotides is necessary for the progression of unwinding initiated in the EP (4). Future studies will address the role of the second pair of pentanucleotides in the unwinding mechanism. It may be of interest to determine whether SV40 transcriptional regulation (29) also depends upon selective occupancy of particular pentanucleotide pairs. Finally, additional experiments will establish whether the assembly of initiator proteins at other origins of replication (39) requires only a subset of the available binding sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Borowiec and D. Simmons for advice on the KMnO4 assays and X. Luo and Li Wang for help with computer modeling.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (9RO1GM55397).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bochkarev A, Barwell J A, Pfuetzner R A, Bochkareva E, Frappier L, Edwards A M. Crystal structure of the DNA-binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus origin-binding protein, EBNA1, bound to DNA. Cell. 1996;84:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochkarev A, Barwell J A, Pfuetzner R A, Furey J W, Edwards A M, Frappier L. Crystal structure of the DNA-binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus origin-binding protein EBNA1. Cell. 1995;83:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowiec J A. Inhibition of structural changes in the simian virus 40 core origin of replication by mutation of essential origin sequences. J Virol. 1992;66:5248–5255. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5248-5255.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowiec J A, Dean F B, Bullock P A, Hurwitz J. Binding and unwinding—how T antigen engages the SV40 origin of DNA replication. Cell. 1990;60:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowiec J A, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. Differential induction of structural changes in the simian virus 40 origin of replication by T-antigen. J Virol. 1991;65:1228–1235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1228-1235.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borowiec J A, Hurwitz J. ATP stimulates the binding of the simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen to the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:64–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borowiec J A, Hurwitz J. Localized melting and structural changes in the SV40 origin of replication induced by T-antigen. EMBO J. 1988;7:3149–3158. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley M K, Griffin J D, Livingston D M. Relationship of oligomerization to enzymatic and DNA-binding properties of the SV40 large T antigen. Cell. 1982;28:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock P A. The initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:503–568. doi: 10.3109/10409239709082001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullock P A, Joo W S, Sreekumar K R, Mello C. Initiation of SV40 DNA replication in vitro: analysis of the role played by sequences flanking the core origin on initial synthesis events. Virology. 1997;227:460–473. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bullock P A, Seo Y S, Hurwitz J. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro: pulse-chase experiments identify the first labeled species as topologically unwound. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3944–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullock P A, Tevosian S, Jones C, Denis D. Mapping initiation sites for simian virus 40 DNA synthesis events in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5043–5055. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burhans W C, Huberman J A. DNA replication origins in animal cells: a question of context? Science. 1994;263:639–640. doi: 10.1126/science.8303270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Joo W S, Bullock P A, Simmons D T. The N-terminal side of the origin-binding domain of simian virus 40 large T antigen is involved in A/T untwisting. J Virol. 1997;71:8743–8749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8743-8749.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean F B, Borowiec J A, Eki T, Hurwitz J. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14129–14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dean F B, Borowiec J A, Ishimi Y, Deb S, Tegtmeyer P, Hurwitz J. Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen requires three core replication origin domains for DNA unwinding and replication in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8267–8271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean F B, Bullock P, Murakami Y, Wobbe C R, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. Simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA replication: SV40 large T antigen unwinds DNA containing the SV40 origin of replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:16–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dean F B, Dodson M, Echols H, Hurwitz J. ATP-dependent formation of a specialized nucleoprotein structure by simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen at the SV40 replication origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8981–8985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean F B, Lee S H, Kwong A D, Bullock P, Borowiec J A, Kenny M K, Seo Y S, Eki T, Matsumoto T, Hodgins G, Hurwitz J. SV40 DNA replication in vitro. UCLA Symp Mol Cell Biol New Ser. 1989;127:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deb S, DeLucia A L, Baur C-P, Koff A, Tegtmeyer P. Domain structure of the simian virus 40 core origin of replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1663–1670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deb S, Tsui S, Koff A, DeLucia A L, Parsons R, Tegtmeyer P. The T-antigen-binding domain of the simian virus 40 core origin of replication. J Virol. 1987;61:2143–2149. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2143-2149.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deb S P, Tegtmeyer P. ATP enhances the binding of simian virus 40 large T antigen to the origin of replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3649–3654. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3649-3654.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLucia A L, Deb S, Partin K, Tegtmeyer P. Functional interactions of the simian virus 40 core origin of replication with flanking regulatory sequences. J Virol. 1986;57:138–144. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.138-144.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLucia A L, Lewton B A, Tjian R, Tegtmeyer P. Topography of simian virus 40 A protein-DNA complexes: arrangement of pentanucleotide interaction sites at the origin of replication. J Virol. 1983;46:143–150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.1.143-150.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DePamphilis M L. Eukaryotic DNA replication: anatomy of an origin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiMaio D, Nathans D. Cold-sensitive regulatory mutants of simian virus 40. J Mol Biol. 1980;140:129–146. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dixon R A F, Nathans D. Purification of simian virus 40 large T antigen by immunoaffinity chromatography. J Virol. 1985;53:1001–1004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.3.1001-1004.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodson M, Dean F B, Bullock P, Echols H, Hurwitz J. Unwinding of duplex DNA from the SV40 origin of replication by T antigen. Science. 1987;238:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.2823389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanning E, Knippers R. Structure and function of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fanning E, Nowak B, Burger C. Detection and characterization of multiple forms of simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Virol. 1981;37:92–102. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.1.92-102.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gidoni D, Scheller A, Barnet B, Hantzopoulos P, Oren M, Prives C. Different forms of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen varying in their affinities for DNA. J Virol. 1982;42:456–466. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.2.456-466.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goetz G S, Dean F B, Hurwitz J, Matson S W. The unwinding of duplex regions in DNA by the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen-associated DNA helicase activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegde R S, Grossman S R, Laimins L A, Sigler P B. Crystal structure at 1.7 A of the bovine papillomavirus-1 E2 DNA-binding domain bound to its DNA target. Nature. 1992;359:505–512. doi: 10.1038/359505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Höss A, Moarefi I, Scheidtmann K H, Cisek L J, Corden J L, Dornreiter I, Arthur A K, Fanning E. Altered phosphorylation pattern of simian virus 40 T antigen expressed in insect cells by using a baculovirus vector. J Virol. 1990;64:4799–4807. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4799-4807.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacob F, Brenner S, Cuzin F. On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1963;28:329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones K A, Tjian R. Essential contact residues within SV40 large T antigen binding sites I and II identified by alkylation-interference. Cell. 1984;36:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joo W S, Luo X, Denis D, Kim H Y, Rainey G J, Jones C, Sreekumar K R, Bullock P A. Purification of the simian virus 40 (SV40) T-antigen DNA binding domain and characterization of its interactions with the SV40 origin. J Virol. 1997;71:3972–3985. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3972-3985.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kadonaga J T, Tjian R. Affinity purification of sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5889–5893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman & Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuwabara M D, Sigman D S. Footprinting DNA-protein complexes in situ following gel retardation assays using 1,10-phenanthroline-copper ion: Escherichia coli RNA polymerase-lac promoter complexes. Biochemistry. 1987;26:7234–7238. doi: 10.1021/bi00397a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon H J, Tirumalai R, Landy A, Ellenberger T. Flexibility in DNA recombination: structure of the lambda integrase catalytic core. Science. 1997;276:126–131. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewton B A, DeLucia A L, Tegtmeyer P. Binding of simian virus 40 A protein to DNA with deletions at the origin of replication. J Virol. 1984;49:9–13. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.9-13.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J J, Peden K W C, Dixon R A F, Kelly T. Functional organization of the simian virus 40 origin of DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1117–1128. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorimer H E, Reynisdottir I, Ness S, Prives C. Unusual properties of a replication-defective mutant SV40 large T-antigen. Virology. 1993;192:402–414. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo X, Sanford D G, Bullock P A, Bachovchin W W. Structure of the origin specific DNA binding domain from simian virus 40 T-antigen. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:1034–1039. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lusky M, Hurwitz J, Seo Y-S. Cooperative assembly of the bovine papilloma virus E1 and E2 proteins on the replication origin requires an intact E2 binding site. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15795–15803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mastrangelo I A, Bezanilla M, Hansma P K, Hough P V C, Hansma H G. Structures of large T antigen at the origin of SV40 DNA replication by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J. 1994;66:293–298. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80800-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mastrangelo I A, Hough P V C, Wall J S, Dodson M, Dean F B, Hurwitz J. ATP-dependent assembly of double hexamers of SV40 T antigen at the viral origin of DNA replication. Nature (London) 1989;338:658–662. doi: 10.1038/338658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maxam A M, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McVey D, Ray S, Gluzman Y, Berger L, Wildeman A G, Marshak D R, Tegtmeyer P. cdc2 phosphorylation of threonine 124 activates the origin-unwinding functions of simian virus 40 T antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:5206–5215. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5206-5215.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McVey D, Woelker B, Tegtmeyer P. Mechanisms of simian virus 40 T-antigen activation by phosphorylation of threonine 124. J Virol. 1996;70:3887–3893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3887-3893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moarefi I F, Small D, Gilbert I, Hopfner M, Randall S K, Schneider C, Russo A A R, Ramsperger U, Arthur A K, Stahl H, Kelly T J, Fanning E. Mutation of the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation site in simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen specifically blocks SV40 origin DNA unwinding. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;67:4992–5002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4992-5002.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murakami Y, Hurwitz J. DNA polymerase α stimulates the ATP-dependent binding of simian virus tumor T antigen to the SV40 origin of replication. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11018–11027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myers R M, Tijan R. Construction and analysis of simian virus 40 origins defective in tumor antigen binding and DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6491–6495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myers R M, Williams R C, Tjian R. Oligomeric structure of a simian virus 40 T antigen in free form and bound to DNA. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:347–353. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Reilly D R, Miller L K. Expression and complex formation of simian virus 40 large T antigen and mouse p53 in insect cells. J Virol. 1988;62:3109–3119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.9.3109-3119.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parsons R, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Three domains in the simian virus 40 core origin orchestrate the binding, melting, and DNA helicase activities of T antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:509–518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.509-518.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parsons R, Tegtmeyer P. Spacing is crucial for coordination of domain functions within the simian virus 40 core origin of replication. J Virol. 1992;66:1933–1942. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1933-1942.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parsons R E, Stenger J E, Ray S, Welker R, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Cooperative assembly of simian virus 40 T-antigen hexamers on functional halves of the replication origin. J Virol. 1991;65:2798–2806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2798-2806.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.San Martin M C, Gruss C, Carazo J M. Six molecules of SV40 large T antigen assemble in a propeller-shaped particle around a channel. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:15–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.SenGupta D J, Borowiec J A. Strand and face: the topography of interactions between the SV40 origin of replication and T-antigen during the initiation of replication. EMBO J. 1994;13:982–992. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simanis V, Lane D P. An immunoaffinity purification procedure for SV40 large T antigen. Virology. 1985;144:88–100. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simmons D T, Upson R, Wun-Kim K, Young W. Biochemical analysis of mutants with changes in the origin-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:4227–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4227-4236.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65a.Sreekumar, K. R., and P. A. Bullock. Unpublished data.

- 66.Stahl H, Droge P, Knippers R. DNA helicase activity of SV40 large tumor antigen. EMBO J. 1986;5:1939–1944. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stillman B. Replicator renaissance. Science. 1993;366:506–507. doi: 10.1038/366506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stillman B, Gerard R D, Guggenheimer R A, Gluzman Y. T antigen and template requirement for SV40 DNA replication in vitro. EMBO J. 1985;4:2933–2939. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tegtmeyer P, Lewton B A, DeLucia A L, Wilson V G, Ryder K. Topography of simian virus 40 A protein-DNA complexes: arrangement of protein bound to the origin of replication. J Virol. 1983;46:151–161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.1.151-161.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tjian R. The binding site on SV40 DNA for a T-antigen related protein. Cell. 1978;13:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tooze J. DNA tumor viruses. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tullius T D. Physical studies of protein-DNA complexes by footprinting. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1989;18:213–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Veal J M, Rill R L. Sequence specificity of DNA cleavage by bis(1,10-phenanthroline) copper(I) Biochemistry. 1988;27:1822–1827. doi: 10.1021/bi00406a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Virshup D M, Russo A A R, Kelly T J. Mechanism of activation of simian virus 40 DNA replication by protein phosphatase 2A. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4883–4895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.4883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wobbe C R, Dean F, Weissbach L, Hurwitz J. In vitro replication of duplex circular DNA containing the simian virus 40 DNA origin site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wun-Kim K, Upson R, Young W, Melendy T, Stillman B, Simmons D T. The DNA-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen has multiple functions. J Virol. 1993;67:7608–7611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7608-7611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]