Abstract

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane review previously published in 2008. Smoking increases the risk of developing atherosclerosis but also acute thrombotic events. Quitting smoking is potentially the most effective secondary prevention measure and improves prognosis after a cardiac event, but more than half of the patients continue to smoke, and improved cessation aids are urgently required.

Objectives

This review aimed to examine the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease in short‐term (6 to 12 month follow‐up) and long‐term (more than 12 months). Moderators of treatment effects (i.e. intervention types, treatment dose, methodological criteria) were used for stratification.

Search methods

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 12, 2012), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and PSYNDEX were searched from the start of the database to January 2013. This is an update of the initial search in 2003. Results were supplemented by cross‐checking references, and handsearches in selected journals and systematic reviews. No language restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with CHD with a minimum follow‐up of 6 months.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial eligibility and risk of bias. Abstinence rates were computed according to an intention to treat analysis if possible, or if not according to completer analysis results only. Subgroups of specific intervention strategies were analysed separately. The impact of study quality on efficacy was studied in a moderator analysis. Risk ratios (RR) were pooled using the Mantel‐Haenszel and random‐effects model with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We found 40 RCTs meeting inclusion criteria in total (21 trials were new in this update, 5 new trials contributed to long‐term results (more than 12 months)). Interventions consist of behavioural therapeutic approaches, telephone support and self‐help material and were either focused on smoking cessation alone or addressed several risk factors (eg. obesity, inactivity and smoking). The trials mostly included older male patients with CHD, predominantly myocardial infarction (MI). After an initial selection of studies three trials with implausible large effects of RR > 5 which contributed to substantial heterogeneity were excluded. Overall there was a positive effect of interventions on abstinence after 6 to 12 months (risk ratio (RR) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 1.32, I² 54%; abstinence rate treatment group = 46%, abstinence rate control group 37.4%), but heterogeneity between trials was substantial. Studies with validated assessment of smoking status at follow‐up had similar efficacy (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.39) to non‐validated trials (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.35). Studies were stratified by intervention strategy and intensity of the intervention. Clustering reduced heterogeneity, although many trials used more than one type of intervention. The RRs for different strategies were similar (behavioural therapies RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.34, I² 40%; telephone support RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.30, I² 44%; self‐help RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.33, I² 40%). More intense interventions (any initial contact plus follow‐up over one month) showed increased quit rates (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.40, I² 58%) whereas brief interventions (either one single initial contact lasting less than an hour with no follow‐up, one or more contacts in total over an hour with no follow‐up or any initial contact plus follow‐up of less than one months) did not appear effective (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.12, I² 0%). Seven trials had long‐term follow‐up (over 12 months), and did not show any benefits. Adverse side effects were not reported in any trial. These findings are based on studies with rather low risk of selection bias but high risk of detection bias (namely unblinded or non validated assessment of smoking status).

Authors' conclusions

Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions are effective in promoting abstinence up to 1 year, provided they are of sufficient duration. After one year, the studies showed favourable effects of smoking cessation intervention, but more studies including cost‐effectiveness analyses are needed. Further studies should also analyse the additional benefit of a psychosocial intervention strategy to pharmacological therapy (e.g. nicotine replacement therapy) compared with pharmacological treatment alone and investigate economic outcomes.

Keywords: Aged, Female, Humans, Male, Middle Aged, Coronary Disease, Myocardial Infarction, Distance Counseling, Motivation, Obesity, Obesity/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risk Factors, Sedentary Behavior, Self Care, Smoking Cessation, Smoking Cessation/methods, Smoking Cessation/psychology, Telephone, Time Factors

Plain language summary

Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions help patients with heart attacks to quit.

Smoking is a risk factor for heart attacks and stopping smoking is recommended for patients after a heart attack. Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions like counseling can help such patients to stop smoking, if they are provided for over one month. Psychosocial interventions can help such patients to quit within 6 months but studies about the long term effects did not support the beneficial short‐term findings. Most trials used a mixture of different intervention strategies, therefore no single strategy showed superior efficacy.

Background

Description of the condition

Smoking is a major, and independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD). Compared to non‐smokers the odds ratio (OR) for myocardial infarction is about 2.5, and for cardiovascular diseases overall the OR is about 2 (Cook 1986; Jacobs 1999; Kawachi 1993; Kawachi 1994; Keil 1998; Njolstad 1996; Nyboe 1991; Prescott 1998; Shaper 1985; Tunstall‐Pedoe 1997; Willett 1987; Woodward 1999). Furthermore, after a cardiac event smokers are twice as likely to get restenosis or to die from a cardiovascular disease (Cullen 1997; Fulton 1997; Kawachi 1993; Kawachi 1994; Kuller 1991; Luoto 1998; Tverdal 1993; Willett 1987). A systematic review in patients with CHD estimated a reduction in mortality risk of 36% in 3‐5 years after quitting smoking (Critchley 2003). Non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI) also occurs less often in smokers who quit after their first cardiac event (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.83) (Barth 2007). Compared to persistent smokers, quitters after an acute coronary syndrome have at 6 months a lower risk ratio (RR) of 0.74 for MI/stroke/death (95% CI 0.53 to 1.02; P=0.0698) (Chow 2010). However, many smokers do not quit even after a CHD diagnosis (Critchley 2003) , or resume smoking after the initial "smoking‐free" acute cardiac event hospitalisation and it is critical to summarise available evidence on the effectiveness of different intervention strategies for smoking cessation in this patient group.

Available interventions for smoking cessation

Several intervention strategies in healthy people have shown encouraging results in systematic reviews. For self‐help interventions tailored materials were more efficacious than no intervention (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.42) but "standard materials" were also efficacious (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.39). Tailored materials are adapted to the situation of the client and to the specific support needs. Tailored materials might potentially be more effective due to additional patient contact whilst assessing individual patient needs (Noar 2007). Other reviews of smoking cessation using telephone support have suggested that continuous personal contact might improve cessation rate. Continuous telephone counselling was more effective than less intense interventions such as educational self‐help materials only (Stead 2013a). Self‐help interventions as "add‐ons" to counselling was shown to be not efficacious (Lancaster 2009). Telephone support as a single intervention increased quit rates by 37% (RR 1.37, CI 1.26 to 1.50). (Stead 2013a)

Different treatment providers also showed beneficial effects in smoking cessation counselling. Brief advice from a physician was effective for quitting (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.94) with somewhat larger efficacy in more intense interventions (RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.13) (Stead 2013b). Counseling by nurses was less effective but still showed positive results (RR 1.29, 95%CI 1.20 to 1.39) (Rice 2013).

Rigotti has demonstrated the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions for hospitalised patients (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.48) and stressed the importance of at least one follow‐up contact to maintain abstinence (Rigotti 2012). This finding is in line with the review on nursing interventions, which pointed out the need for follow up contacts as well (Rice 2013). The incorporated treatment strategies in these reviews can be summarised as psychosocial interventions and can be differentiated from psychopharmacological or substance replacement treatment strategies (e.g. antidepressants, nicotine replacement). For cardiac patients, such psychosocial interventions to quit smoking are recommended along with nicotine replacement therapies and bupropion (ACC/AHA 2002; ACC/AHA 2004; DeBacker 2003; Ockene 1997).The most recent European guidelines (ESC 2012; ESC 2013; ESC/EACPR 2012) underline the importance of assessing smoking status and offering adequate interventions for quitting smoking in cardiac patients.

Pharmacological interventions (e.g. NRTs and medication such as bupropion) are also established medical treatment for smoking cessation, which may be used in isolation or in conjunction with a psychosocial intervention. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and medication (especially Bupropion and Varenicline) are also established medical treatments for smoking cessation. NRT and Bupropion showed similar efficacy compared to placebo with an OR of 1.84 (95% CI 1.71 to 1.99) and an OR of 1.82 (95% CI 1.60 to 2.06) respectively (Cahill 2013). Varenicline improved cessation rates as well with an OR of 1.57 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.91) (Cahill 2013). No increase in adverse cardiac events for Bupropion was found (Stead 2012) but concerns about adverse cardiac events caused by Varenicline were raised (Singh 2011).

Why is it important to do this review

Our initial meta‐analysis of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions in CHD patients showed that they were effective in increasing abstinence at 6‐12 months provided the interventions were of sufficient intensity . However, studies with long‐term follow up were scarce and study quality of early studies was very limited. In an updated systematic review we incorporated more recent trials in order to increase the study pool and the robustness of our findings.

Objectives

This review aimed to evaluate psychosocial intervention strategies for smoking cessation in patients with CHD, with four specific objectives.

1. To examine the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease in short‐term (6 to 12 month follow‐up) and long‐term (more than 12 months). 2. To examine the efficacy of different psychosocial intervention types (e.g. telephone support) to stop smoking in patients with coronary heart disease. 3. To investigate the dose‐response relationship: Are brief interventions as effective as more intense interventions? 4. To examine methodological criteria which may moderate the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in patients with coronary heart disease (for example validation versus self‐report of abstinence).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials studying the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation in CHD patients with an assessment of smoking status at least 6 months after baseline assessment of smoking status.

In the control condition usual care or no specific intervention was delivered.

Types of participants

Patients with CHD ‐ myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (International Classification of Diseases 9 codes 410‐414). Studies including patients with other diseases were accepted if at least 80% of patients in the sample suffered from CHD. CHD patients with any co‐morbidities were included. Patients had to be smokers at baseline. Initial smoking status was assessed either by self‐report or by a validated measure. Studies on hospital populations with mixed somatic diagnosis (for example cancer and CHD) were excluded. Trials were also excluded if there was not sufficient information available about the patient's somatic diagnoses.

Types of interventions

The psychosocial intervention could be provided in two ways; either as a separate psychosocial intervention with a main focus on smoking cessation or as a part of a more comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programme targeting also other risk factors (e.g. obesity, inactivity). Any psychosocial intervention with the goal to change smoking behaviour in CHD patients was of interest. Psychosocial interventions use counselling, motivational support and advice, with or without provision of written educational materials about strategies for smoking cessation. We excluded studies, that used only a pharmacological treatment or nicotine replacement therapy. Other non pharmacological interventions like exercise or physiotherapy were not considered as psychosocial interventions due to the missing psychological ingredient of such interventions. Interventions could be delivered initially during hospital admission or after hospital admission to non acute patients during rehabilitation. The interventions could be provided in group or individual settings.

The psychosocial interventions were categorised according to their ingredients into five non exclusive categories (behavioural therapy, phone support, self‐help, multirisk, specific intervention). Behavioural therapy is based on learning theory and applies strategies like coping with risky situations for smoking, incentives for abstinence and motivational issues (i.e. motivational interviewing). Phone support provide encouraging support via the telephone. Self‐help provides information on how to withdraw from smoking. These three intervention strategies are often used as combination. We additionally coded if the intervention focus on smoking (specific intervention) or if other risk factors were also adressed by the intervention (multirisk intervention). These two strategies are mutually exclusive.

The control conditions were either usual care (patients were allowed to seek support for smoking cessation but a structured referal was not done) or control conditions with unspecific interventions (such as educational material on health issues).

Types of outcome measures

Abstinence by self‐report or validated (e.g. carbon monoxide) measurement at a minimum of 6 months. The outcome is dichotomous (non smoker versus smoker). We did not extract data on the number of cigarettes smoked per day, as there is little evidence that smoking reduction alters the risk of future cardiac events or mortality.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Issue 12, 2012) on The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (OVID, 1950 to January week 1 2013), EMBASE (OVID, 1980 to 2013 week 1), PsycINFO (OVID, 1806 to January week 2 2013), Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S, 1990 to 11 January 2013) on Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) and PSYNDEX (1977 to June 2003). This is an updated search (see Appendix 1) of the initial search which was done in 2003 (see Appendix 2). The sensitivity maximising Cochrane RCT filter has been applied to the MEDLINE search and adaptations of it to EMBASE, PsycINFO and Web of Science (Lefebvre 2011).

Additionally we searched in The Cochrane Library for reviews on smoking cessation for primary studies (Issue 4, 2012).

Searching other resources

We searched for trials included in other reviews (Lancaster 2005; Rigotti 2007; Stead 2005; Stead 2006; Wiggers 2003) and hand‐searched relevant journals from 1998 to 2003 (Annals of Internal Medicine, Archives of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal, Psychology and Health, Health Psychology, Tobacco Control) for the initial selection of trials for the first version of this review.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and coding Data were independently extracted by two people (initially: JB and Corina Güthlin; update: TJ and ID). In case of differences between codings in the updated dataset a consensus was reached with a third rater (JB).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We coded four quality indicators according to the risk of bias tool from each study (see Cochrane Handbook). Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias (JB, TJ): Allocation concealment, sequence generation, completeness of outcome data, and validation of smoking status. Allocation concealment and sequence generation was coded according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration (see Cochrane Handbook). We extracted data on both an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and a completer analysis. In the first model we classified persons without information about smoking status at follow‐up as smokers (ITT analysis) (attrition bias). In the second model we included only participants with follow‐up information on smoking status (completer analysis) as presented by the authors. In ambiguous studies we classified the outcome data as completer analysis. If an ITT analysis from the study report was possible, we extracted the data from this information.

We coded biochemical validation of smoking status. If trials used cotinine levels in urine or other standardised procedures to assess smoking status we coded this as validated outcome assessment. In studies with self‐report or peer‐report outcome assessment we classified this as non‐validated outcome assessment.

Three quality indicators were not separately coded for each study. Blinding of treatment providers and patients is not possible in psychosocial interventions (performance bias). The assessment of study outcomes (i.e. validation) was used to rate the validity of smoking status (detection bias). However, an overall rating of blinding comprising both facets was not done. We were not able to rate the selective outcome reporting, since the majority of studies did not specify any primary or secondary outcomes in the publications or protocols. Therefore the category "unclear" reflects the available information.

Data about sample and intervention Data on setting, CHD diagnosis or procedure, number of subjects, sex, age, and length of follow up were extracted. Four types of intervention strategies were coded; behavioural therapeutic approaches ; phone support ; additional self‐help intervention ; multi‐risk factor interventions vs. specific interventions for smoking cessation (see Characteristics of included studies table). The number of patients is indicated by a small n and the number of trials for a specific analysis is indicated with a capitalised N. Data about treatment duration We assessed duration of treatment as in another review (Rigotti 2012) and coded this as follows:

1) Single initial contact lasting <= 1 hour, no follow‐up support; 2) One or more contacts in total > 1 hour, no follow‐up support; 3) Any initial contact plus follow‐up <=1 month; 4) Any initial contact plus follow‐up > 1 month and <= 6 month; and 5) Any initial contact plus follow‐up > 6 month.

A cut off of 3 was used to classify interventions as brief (categories 1 to 3) or as intense (4 and 5).

Measures of treatment effect

Risk ratios (RR) were calculated from abstinence rates after the intervention comparing the intervention group with the control group. A RR > 1 indicates superiority of the intervention group over the control group and vice versa.

Dealing with missing data

We used data from the conservative analysis (ITT) in preference, and only used data from the completer analysis if data from the ITT analysis was not available. As a sensitivity analysis, we performed a meta‐analysis with studies with ITT data only.

Data synthesis Risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the pooled estimates. A random‐effects model for pooling the studies was employed because of expected heterogeneity in the primary studies (DerSimonian and Laird method) (Deeks 1999). A forest plot presents the results of the overall analysis with all studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed by examining forest plots of trials, by calculating chi squared heterogeneity test, and I² statistics. The chi squared value tests for statistically significant heterogeneity between trials; higher I² values indicate greater variability between trials than would be expected by chance alone (range 0‐100%) (Higgins 2003).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed four sub‐group analyses according to risk of bias indicators:

Trials with adequate sequence generation were compared to trials with inadequate or unclear sequence generation

Trials with adequate allocation concealment were compared to trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment

Trials with validated smoking status were compared to non‐validated trials

Trials were grouped according to their procedure to deal with incomplete outcome data. As described above ITT analysis (adequate) and completer analysis (inadequate) were coded.

In addition to that we conducted sub‐group analysis according to intervention characteristics and length of follow‐up

Trials were grouped by type of intervention (i.e. behavioural therapy, phone support, self‐help, multirisk, specific intervention).

Trials with a treatment duration of less than 1 month (brief intervention) versus studies with an intervention of 1 month or more (intense intervention).

Intervention effects were measured in short‐term (6 to 12 months) and long‐term (more than 12 months).

Results

Description of studies

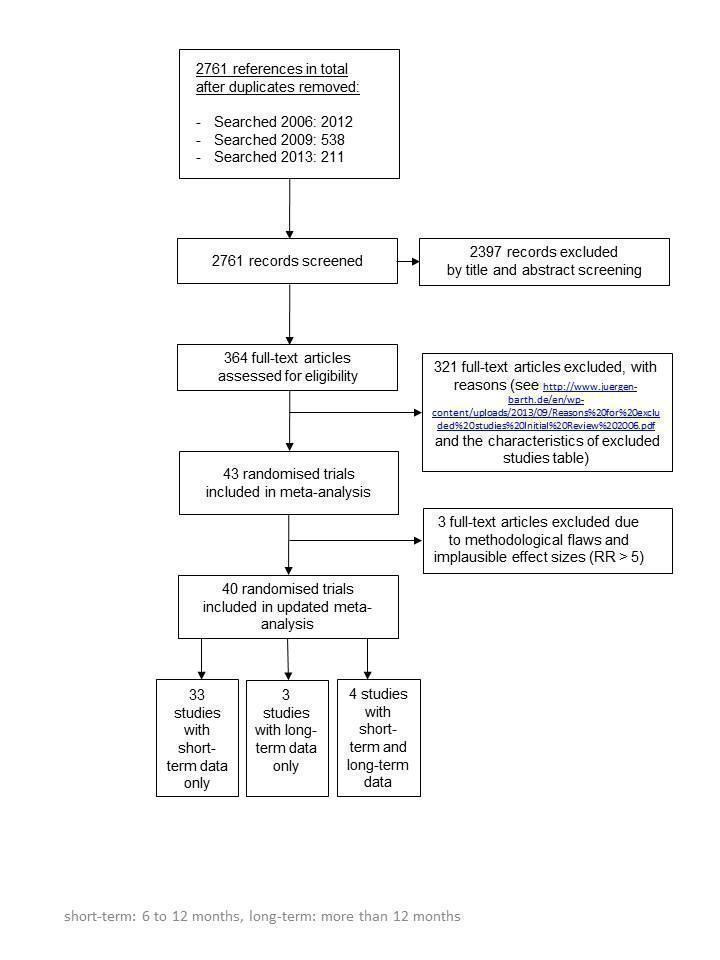

The combination of the electronic database searches and additional citations found by scanning references in relevant Cochrane Reviews, other meta‐analyses, and journals in 2006, 2009 and 2013 resulted in 2761 records (Appendix 4; see flowchart in Figure 1). After exclusions on the basis of title and abstract, 364 full‐text articles were assessed for inclusion. Of these a further 321 full‐text articles were excluded for reasons detailed in the characteristics of excluded studies table (Characteristics of excluded studies) and under http://www.juergen‐barth.de/en/wp‐content/uploads/2013/09/Reasons%20for%20excluded%20studies%20Initial%20Review%202006.pdf . Four papers are awaiting assessment as we could not access the papers and authors did not respond to PDF requests (Becker 2003; Boulay 2001; Enriquez‐Puga 2001; Puente‐Silva 1989).

1.

Flow chart of study selection

Forty trials (with short‐term and long‐term results) were included in the review (Allen 1996; Benner 2008; Blasco 2012; Bolman 2002a; Burt 1974; Carlsson 1997; CASIS 1992; Chan 2012; Cossette 2011; Costa e Silva 2008; DeBusk 1994; Dornelas 2000; Froelicher 2004; Gao 2011; Hajek 2002; Han 2011; Hanssen 2007; Hanssen 2009; Heller 1993; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Jiang 2007; Kubilius 2012; Mildestvedt 2007; Mosca 2010; Naser 2008; Neubeck 2011; Ortigosa 2000; Otterstad 2003; Pedersen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2003; Quist‐Paulsen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2006a; Reid 2003; Rigotti 1994; Sivarajan 1983; Smith 2009; Taylor 1990; van Elderen (group); van Elderen (phone); Zwisler 2008). Of those 40 trials 33 reported on short‐term results, 4 trials reported both short‐ and long‐term results and 3 trials reported on long‐term results only. In summary seven trials provided data on a long‐term follow up after 12 months (CASIS 1992; Froelicher 2004; Hanssen 2009; Mildestvedt 2007; Naser 2008; Otterstad 2003; Rigotti 1994). As a result of this update we identified 21 new trials, which contributed to this review. Five new trials contributed to long‐term results.

From the studies with short‐term findings (N = 37), sixteen studies were carried out in Europe (1 Sweden, 2 United Kingdom, 3 Netherlands, 5 Norway, 2 Spain, 1 Lithuania, 2 Denmark), ten were from the USA, two from Australia, three from Canada, four from China, one from Brazil and one was a multinational study. The papers were mainly published in English, one was written in Spanish (Ortigosa 2000), one in French (Cossette 2011) and one in Danish (Pedersen 2005). All trials compared a specific smoking cessation intervention with a usual care condition, had comparable groups at study entry, had lower than 50% drop out rates and assessed smoking status before a cardiac event or procedure. 3830 patients were randomised to the usual care group and 3852 received a special psychosocial intervention. As expected, 70 to 90% of the patients were male, mean age was relatively young, 50 to 60 years.The patients suffered predominantly from myocardial infarction or had invasive interventions (bypass surgery, stent). The intervention strategies employed were behavioural therapeutic interventions (20 studies), and self‐help programmes (18 studies). Additional phone support was provided in 26 trials. Seventeen studies reported interventions aimed specifically at smoking cessation, 20 studies employed multi‐risk strategies. Behavioural therapeutic interventions were either provided in a group setting or as individual counselling. The aim was to identify cues related to smoking, or more generally stress reduction and relaxation techniques. Other components included preparation for relapse or specific motivational techniques based on the transtheoretical model (Prochaska 1986) or the strategy of motivational interviewing (Rollnick 1997). Self‐help interventions consisted of information booklets, audio‐ or videotapes. Information booklets which simply described risk factors were not considered self‐help interventions. No studies were available for the comparison of different psychosocial interventions or of psychosocial intervention with different intensity.

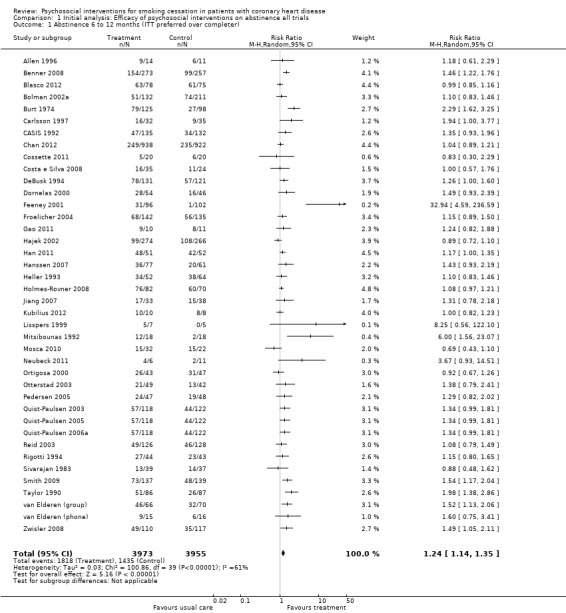

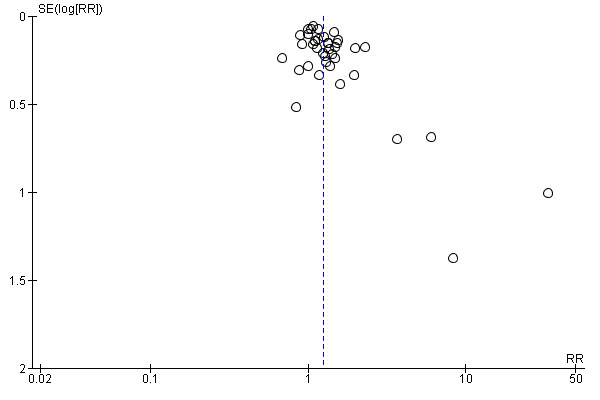

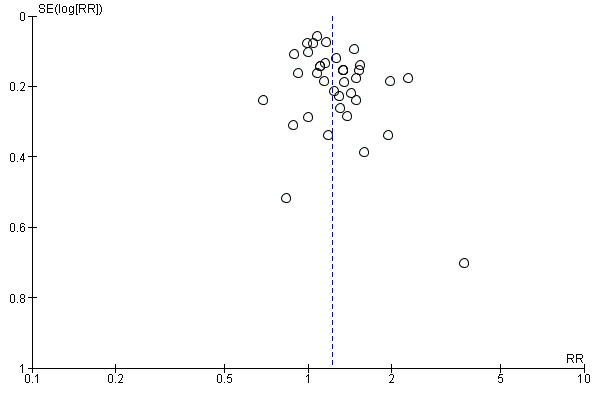

In an initial pooling of the short‐term results from 40 included trials we found a RR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.35, n = 7928, N = 40) indicating the efficacy of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions in CHD patients (Analysis 1.1). However, a funnel plot showed outliers with very large effect sizes (Figure 2). These outliers contributed to a large amount of heterogeneity, since we found in the initial analysis an I² of 61%. Therefore a further three studies were excluded using the post hoc exclusion criteria of an unrealistic treatment effect of an RR larger than 5. Feeney 2001 reported a RR of 32.94. Lisspers 1999 reported a RR of 8.25. Mitsibounas 1992 found an effect of RR = 6.00. These trials all had also very substantial methodological flaws. Excluding these three studies had only a small effect on the overall effectiveness of the intervention (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.32, n = 7682, N = 37) but achieved a more balanced funnel plot (Figure 3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Initial analysis: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence all trials, Outcome 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer).

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Initial analysis: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence (6 to 12 months; all trials), outcome: 1.1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence (6 to 12 months; all trials), outcome: 2.1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer).

Risk of bias in included studies

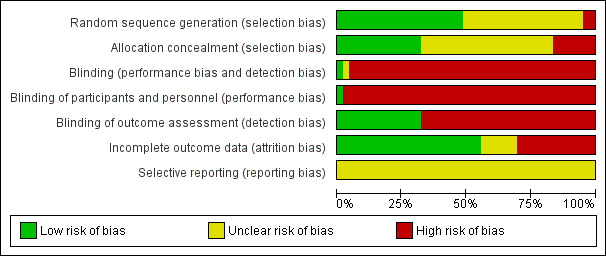

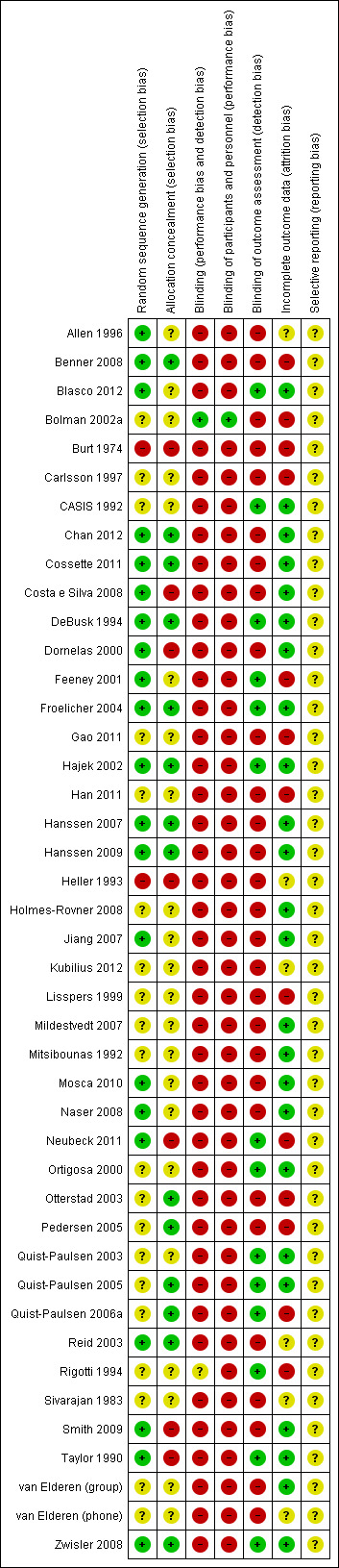

Out of 37 studies, 18 reported an adequate method for random sequence generation (Allen 1996; Benner 2008; Blasco 2012; Chan 2012; Cossette 2011; Costa e Silva 2008; DeBusk 1994; Dornelas 2000; Froelicher 2004; Hajek 2002; Hanssen 2007; Jiang 2007; Mosca 2010; Neubeck 2011; Reid 2003; Smith 2009; Taylor 1990; Zwisler 2008). Seventeen studies had unclear information concerning sequence generation (Bolman 2002a; Carlsson 1997; CASIS 1992; Gao 2011; Han 2011; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Kubilius 2012; Ortigosa 2000; Otterstad 2003; Pedersen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2003; Quist‐Paulsen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2006a; Rigotti 1994; Sivarajan 1983; van Elderen (group); van Elderen (phone)) and only Burt 1974 and Heller 1993 reported an inadequate method. Only 13 studies reported adequate allocation concealment (Benner 2008; Chan 2012; Cossette 2011; DeBusk 1994; Froelicher 2004; Hajek 2002; Hanssen 2007; Otterstad 2003; Pedersen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2006a; Reid 2003; Zwisler 2008). Sixteen studies reported unclear information (Allen 1996; Blasco 2012; Bolman 2002a; Carlsson 1997; CASIS 1992; Gao 2011; Han 2011; Jiang 2007; Kubilius 2012; Mosca 2010; Ortigosa 2000; Otterstad 2003; Rigotti 1994; Sivarajan 1983; van Elderen (group); van Elderen (phone)) and eight studies were inadequate concerning allocation concealment (Burt 1974; Costa e Silva 2008; Dornelas 2000; Heller 1993; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Neubeck 2011; Smith 2009; Taylor 1990). Blinding was inadequate in all studies, except in Bolman 2002a where it was adequate since the personnel were not blinded but this was unlikely to introduce bias because the whole hospital was randomised with significant difference between the two groups at the process evaluation. Concerning incomplete outcome data, 26 studies reported adequate information (Blasco 2012; Bolman 2002a; CASIS 1992; Chan 2012; Cossette 2011; Costa e Silva 2008; DeBusk 1994; Dornelas 2000; Froelicher 2004; Hajek 2002; Hanssen 2007; Holmes‐Rovner 2008; Jiang 2007; Mosca 2010; Ortigosa 2000; Otterstad 2003; Quist‐Paulsen 2003; Quist‐Paulsen 2005; Quist‐Paulsen 2006a; Reid 2003; Rigotti 1994; Sivarajan 1983; Smith 2009; Taylor 1990; van Elderen (group); Zwisler 2008). Eleven studies were either unclear or reported inadequate information about incomplete outcome data (Allen 1996; Benner 2008; Burt 1974; Carlsson 1997; Gao 2011; Han 2011; Heller 1993; Kubilius 2012; Neubeck 2011; Pedersen 2005; van Elderen (phone)). In 24 studies, smoking cessation was self‐reported and 13 studies validated self‐reported smoking cessation with measurements of cotinine in urine or saliva. Summary of risk of bias are found in Figure 4; Figure 5.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

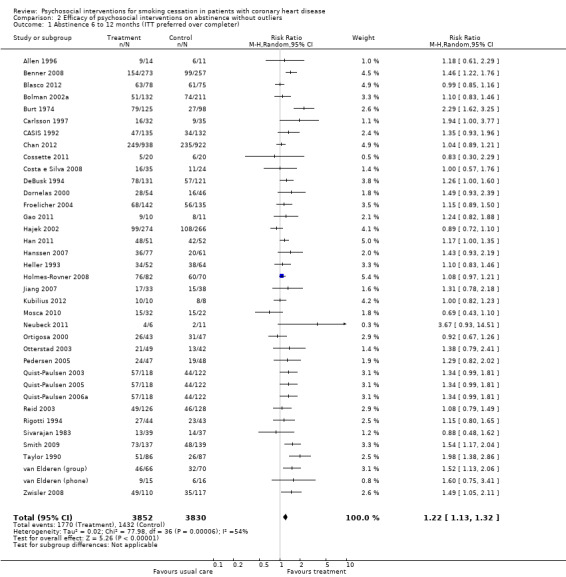

Effects of interventions

Psychosocial smoking cessation interventions were effective in achieving smoking abstinence in CHD patients (number of patients = 3852), compared with usual care (number of patients = 3830) (see Table 1). In all trials, patients receiving the specific psychosocial intervention had more than a 20% higher chance of quitting (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.32, n = 7682, N = 37). There was moderate heterogeneity between studies (chi² 77.98; df 36, P < 0.0001, I² 54%) (Analysis 2.1). Therefore the overall result should be interpreted with some caution. There were considerable differences between trials in the proportion of abstinent patients after the intervention: Kubilius 2012 achieved 100% abstinence in the intervention group, but Chan 2012 reports the lowest abstinence rate with 26.5%. These differences between trials in quit rates might also be responsible for some of the heterogeneity in findings. The pooled RR suggests that psychosocial interventions can increase the chance of quitting compared with usual care, but the heterogeneity in the results need further exploration. The quality of the trials may partly explain this heterogeneity and therefore a subgroup analysis according to risk of bias indicators was used.

1. Summary of findings short term.

| Analysis | Studies | Participants | Risk Ratio | Confidence Interval 95% | Heterogeneity I square |

| Overall analyses | |||||

| All studies (with outliers) | 40 | 7928 | 1.24 | 1.14‐1.35 | 61% |

| All studies (without outliers) | 37 | 7682 | 1.22 | 1.13‐1.32 | 54% |

| Stratified analyses by risk of bias indicators | |||||

| Sequence generation | |||||

| Adequate | 18 | 5046 | 1.21 | 1.07‐1.36 | 61% |

| Inadequate | 19 | 2636 | 1.24 | 1.12‐1.37 | 53% |

| Allocation concealment | |||||

| Adequate | 13 | 4784 | 1.21 | 1.09‐1.34 | 39% |

| Inadequate | 24 | 2898 | 1.24 | 1.11‐1.38 | 65% |

| Handling of incomplete outcome data | |||||

| Adequate | 26 | 6436 | 1.18 | 1.09‐1.28 | 46% |

| Inadequate | 11 | 1246 | 1.36 | 1.12‐1.65 | 72% |

| Validation of outcome | |||||

| Validated outcome measure | 13 | 2803 | 1.22 | 1.07‐1.39 | 60% |

| Non‐validated outcome measure | 24 | 4879 | 1.23 | 1.12‐1.35 | 52% |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence without outliers, Outcome 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer).

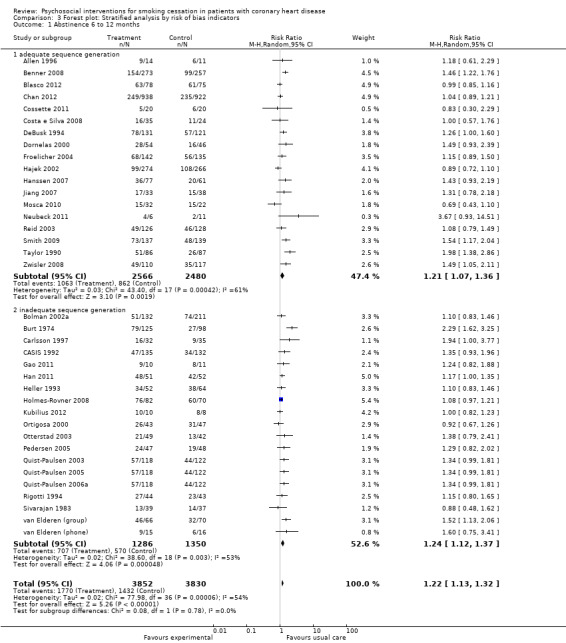

Sub‐group analyses according to risk of bias indicators:

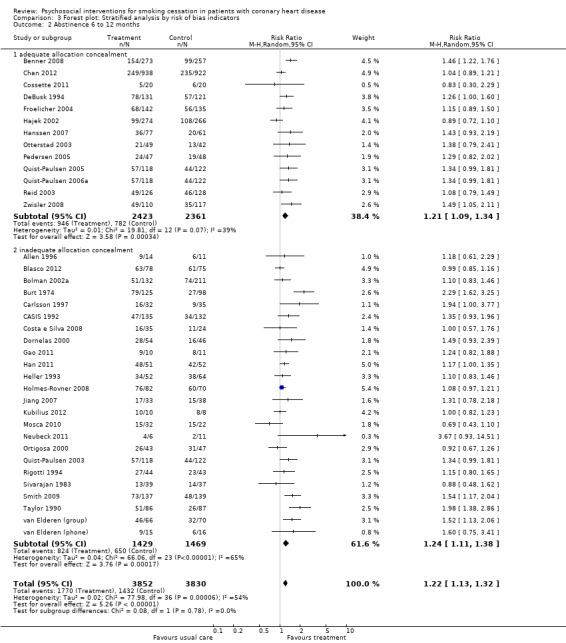

None of the quality indicators affected the effect estimates (all p values > 0.20). Trials with adequate sequence generation showed similar effects compared to trials with inadequate or unclear sequence generation. Trials with adequate sequence generation had a pooled RR of 1.21 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.36, n = 5046, N = 18); trials with inadequate or unclear sequence generation had a pooled RR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.37, n = 2636, N = 19) (Analysis 3.1). No reduction in heterogeneity was achieved by this stratification.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by risk of bias indicators, Outcome 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months.

We have a similar picture when we compared trials with adequate allocation concealment versus inadequate or unclear allocation concealment. The RR was 1.24 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.38, n = 2898, N = 24) for trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment, and 1.21 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.34, n = 4784, N = 13) for trials with adequate allocation concealment (Analysis 3.2). Heterogeneity in the subgroup of studies with adequate allocation concealment was considerably reduced (I² 39% compared to the initial analysis with an I² of 54%)

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by risk of bias indicators, Outcome 2 Abstinence 6 to 12 months.

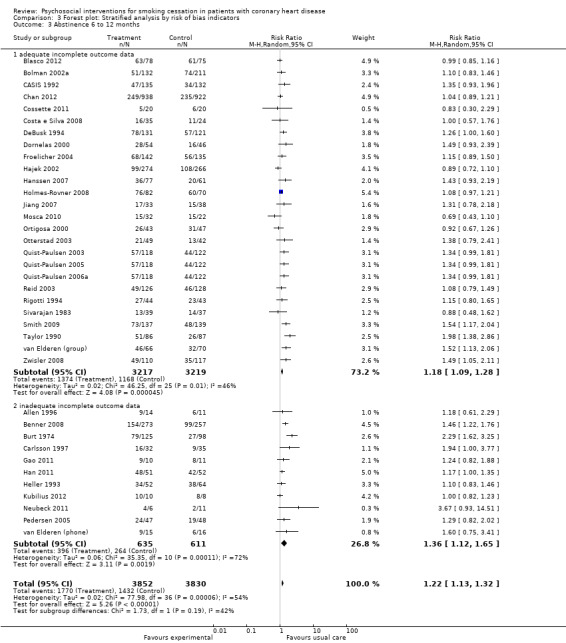

Trials with an adequate method to analyse incomplete outcome data (ITT) appeared less efficacious compared to trials with inadequate or unclear methods to analyse incomplete outcome data (completer analysis), but this difference was not statistically significant. Trials with completer analysis had a larger effect with a RR of 1.36 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.65, n = 1246, N = 11) (Analysis 3.3). Trials with ITT analysis found a reduced effect of 1.18 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.28, n = 6436, N = 26). Heterogeneity in the subgroup of studies with ITT analysis was slightly reduced (I² 46% compared to the initial analysis with an I² of 54%).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by risk of bias indicators, Outcome 3 Abstinence 6 to 12 months.

Trials which validated self‐reported smoking status showed similar efficacy to trials with non validated outcome assessment. Trials with validated abstinence reported a RR of 1.22 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.39, n = 2803, N = 13); non‐validated trials had a similar effect with a RR of 1.23 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.35, n = 4879, N = 24) (Analysis 3.4). Heterogeneity was not reduced.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by risk of bias indicators, Outcome 4 Abstinence at 6 to 12 months.

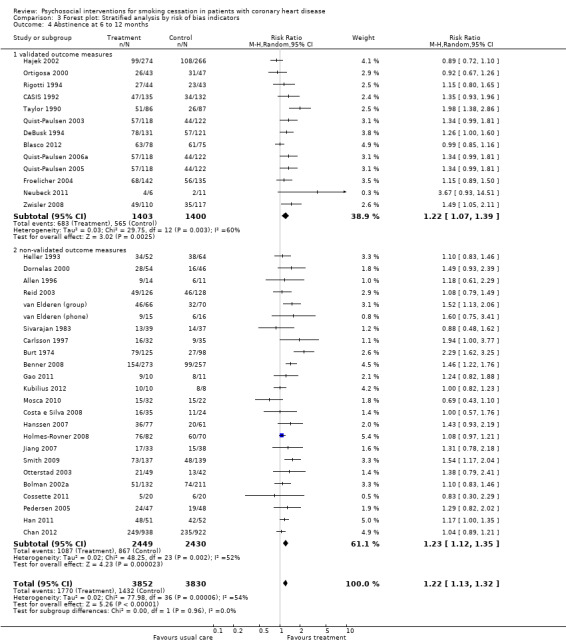

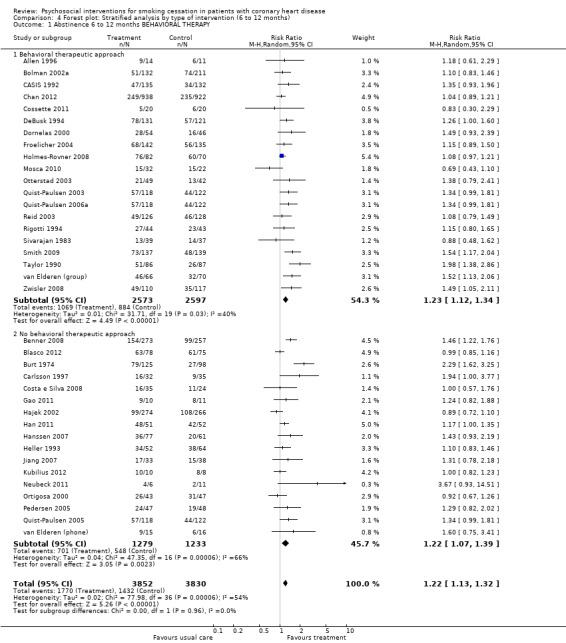

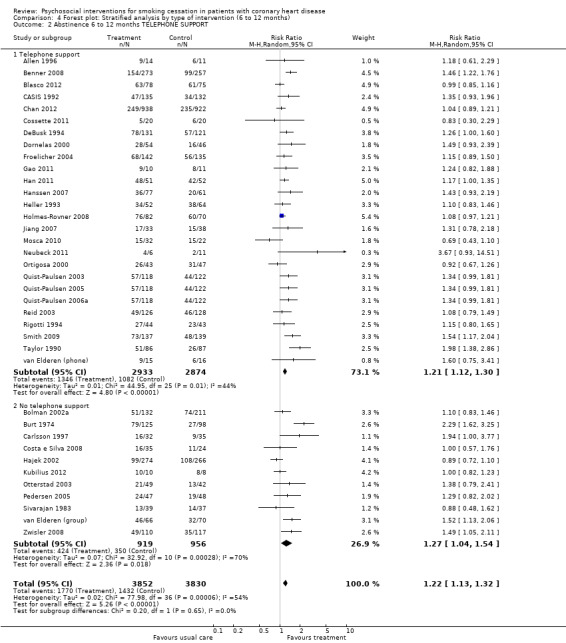

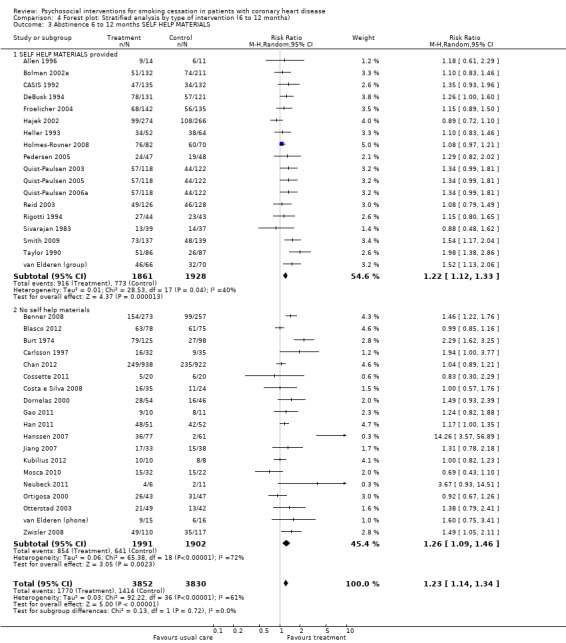

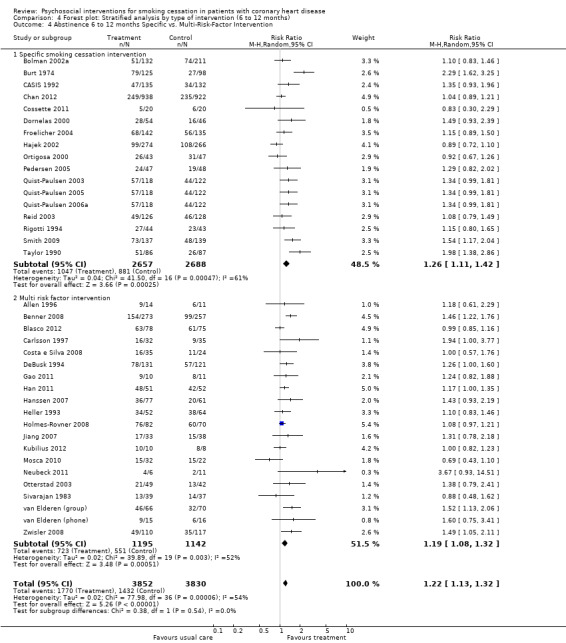

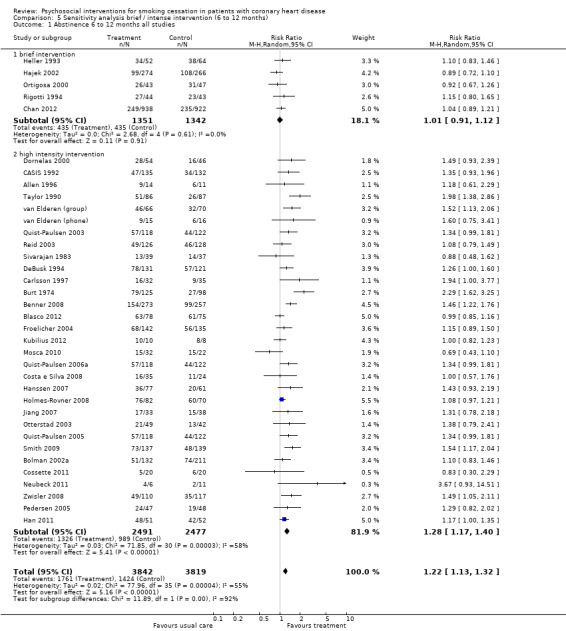

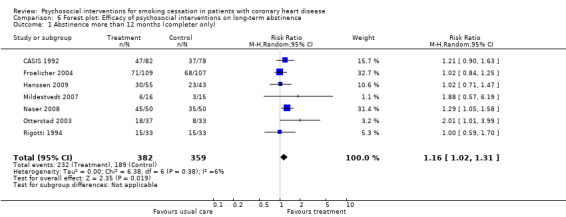

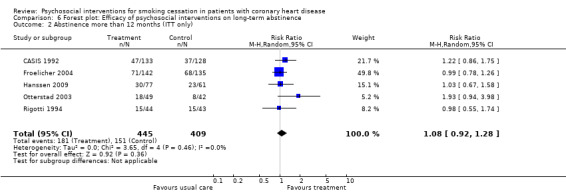

Types of intervention We found no clear evidence that any treatment strategy was more efficacious than others, but heterogeneity was reduced slightly within the intervention cluster. Behavioral therapeutic interventions showed a significant effect on abstinence (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.34, n = 5170, N = 20) with lower heterogeneity (I² 40%) (Analysis 4.1). Telephone support was also effective (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.30, n = 5807, N = 26) and trials more consistent (I² 44%) (Analysis 4.2). However, as most behavioural therapy trials also used telephone support as an intervention strategy, it is difficult to separate the effects of these two types of interventions. Five trials used solely a behavioural therapeutic approach without additional phone contacts (Bolman 2002a; Otterstad 2003; Sivarajan 1983; van Elderen (group); Zwisler 2008). Nine trials used telephone support without behavioural therapeutic techniques (Benner 2008; Blasco 2012; Gao 2011; Han 2011; Hanssen 2007; Jiang 2007; Neubeck 2011; Ortigosa 2000; Quist‐Paulsen 2005). Interventions using self‐help materials showed comparable effectiveness (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.33m n = 3789, N = 18) (Analysis 4.3). Stratification of trials using self‐help materials reduced heterogeneity (I² 40%). We also considered the specificity of the intervention (smoking cessation alone compared with a multi‐risk factor intervention). No meaningful difference was found between multi‐risk factor interventions (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.32, n = 2337, N = 20) and specific cessation intervention (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42, n = 5345, N = 17) (Analysis 4.4). Specific intervention showed highly heterogenous effects (I² 61%); likewise multi‐risk factor intervention effects differed substantially between trials (I² 52%). Duration of the intervention We found clear evidence that brief interventions (i.e. no follow‐up contact or within 4 weeks after initial intervention) were not effective (Chan 2012; Hajek 2002; Heller 1993; Ortigosa 2000; Rigotti 1994) (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.12, I² 0%, n = 2693, N = 5) (Analysis 5.1). When CHD patients were treated with interventions including follow‐up contacts after the initial period of 1 month, the chance of quitting increased substantially (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.40, I² 58%, n = 4968, N = 31) (Analysis 5.1). One study did not report on the duration of the intervention (Gao 2011). Long‐term follow‐up We found preliminary evidence from seven trials for the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in the long‐term (number of patients in the intervention group = 382; number of patients with usual care = 359) (see Table 2). Due to high drop‐out rates after 12 months, separate meta‐analyses for completer and ITT effects were done. In the completer analysis smoking cessation interventions were effective (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.31, n = 741, N = 7) however, this initial finding was not confirmed in the ITT analysis (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.28, n = 854, N = 5) (Analysis 6.1 and Analysis 6.2, respectively).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by type of intervention (6 to 12 months), Outcome 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months BEHAVIORAL THERAPY.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by type of intervention (6 to 12 months), Outcome 2 Abstinence 6 to 12 months TELEPHONE SUPPORT.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by type of intervention (6 to 12 months), Outcome 3 Abstinence 6 to 12 months SELF HELP MATERIALS.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Forest plot: Stratified analysis by type of intervention (6 to 12 months), Outcome 4 Abstinence 6 to 12 months Specific vs. Multi‐Risk‐Factor Intervention.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analysis brief / intense intervention (6 to 12 months), Outcome 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months all studies.

2. Summary of finding long term.

| Analysis | Studies | Participants | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Heterogeneity I square |

| Overall analysis | |||||

| All studies (completer data) | 7 | 741 | 1.16 | 1.02‐1.31 | 6% |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||||

| Studies with ITT analysis | 5 | 854 | 1.08 | 0.92‐1.28 | 0% |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Forest plot: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on long‐term abstinence, Outcome 1 Abstinence more than 12 months (completer only).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Forest plot: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on long‐term abstinence, Outcome 2 Abstinence more than 12 months (ITT only).

Out of seven studies, three reported an adequate method for random sequence generation (Froelicher 2004; Hanssen 2009; Naser 2008) and four had unclear information (CASIS 1992; Mildestvedt 2007; Otterstad 2003; Rigotti 1994). Only three studies reported adequate allocation concealment (Froelicher 2004; Hanssen 2009; Otterstad 2003) and four contained unclear information (CASIS 1992; Mildestvedt 2007; Naser 2008; Rigotti 1994). Blinding was coded as inadequate in all studies, however, blinding of treatment providers is not possible in psychosocial interventions. Concerning incomplete outcome data, five studies reported adequate information (CASIS 1992; Froelicher 2004; Hanssen 2009; Mildestvedt 2007; Naser 2008) and only two were inadequate (Otterstad 2003; Rigotti 1994).

A potential problem with all systematic reviews is publication bias. Our literature search was comprehensive, prepared and partly carried out by the Cochrane Heart Group (UK). Additionally, we investigated publication bias using a funnel plot. The results appear reasonably symmetric which is an indicator of a publication of the studies independent of the study result (Figure 5). There may be a slight tendency for larger trials to show smaller benefits; but larger studies may have interventions with shorter duration and hence smaller effect sizes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found support for the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions with more than 1 month duration, but brief interventions of less than 1 month without supporting contact over time were not effective. We were unable to determine the minimum number of contacts needed. There was no evidence for the efficacy in long‐term follow up studies (over 12 months) with high study quality. Only long‐term studies with completer analysis showed a beneficial effect of psychosocial smoking interventions.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Detailed conclusions about effective intervention strategies are obscured by the fact that a mixture of different interventions was included in many trials. Interventions using telephone support, behavioural therapies, and self‐help were all effective. Some interventions focused only on smoking cessation, but others addressed smoking as part of a multiple risk factor intervention programme (generally a 'cardiac rehabilitation programme'). There was no difference in the chance of quitting for multiple risk factor cardiac rehabilitation programmes, compared with interventions focusing on smoking cessation only. 'Cardiac rehabilitation' programmes may vary in their components, but generally include a graded exercise programme and may also include advice and support from a range of health professionals (such as dieticians, behavioural change specialists etc.). It is difficult to distinguish between the effects of the smoking cessation component of these programmes, and the general support and encouragement of a lifestyle change. Some trials employ nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) as additional cessation strategies, which we could not control for. In one trial, more patients in the psychosocial intervention group received NRT compared to the usual care group (DeBusk 1994) which might bias findings. Other trials did not report use of NRT or other medications to assist with quitting such as bupropion.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings confirm the magnitude of the effect of a smoking cessation intervention of about 30% as shown in other studies. However, the effect is much lower compared to an advice from a physician (about 70% increase in quit rates). This difference can be explained by the high quit rates in the control condition. In GP practices among predominantly healthy patients only about 1% of the population quit smoking without any specific intervention. The situation is completely different in patients with an acute or chronic medical condition. In the included studies of this review about two thirds of the studies reported an abstinence rate of more than 30% without any specific intervention and about half of the studies reported an abstinence rate of more than 50% in the control condition. Therefore, the number to treat statistics should be reported from psychosocial smoking cessation studies to allow health policy makers an appropriate evaluation of the effect of the intervention beyond statistical significance.

Interventions on an individual level should be accompanied by policy measures like smoke free legislation. Non‐smoking environment policy interventions were found to be associated with lower rates of myocardial infarction (Lin 2013). Web‐based interventions for smoking cessation have the advantage of good accessibility. Such interventions were also found to improve quit rates substantially in adult populations (Myung 2009; Civljak 2013) and randomised studies in cardiac patients should be done. The older age of CHD patients might limit the feasibility of web‐based interventions due to impaired vision, cognition and physical skills (Becker 2004).

Quality of the evidence

One possible threat to our results might be methodological flaws in the included primary studies which might overestimate the effectiveness of psychosocial smoking interventions in CHD patients. In the stratified analyses according to quality criteria no significant differences were found. However, the pattern showed larger effects in studies with methodological weaknesses. In particular, studies with an ITT analysis showed smaller effects compared to a "completer analysis". RCTs of smoking cessation should not be published without an ITT analysis as the primary outcome. Trial procedures and quality should be described in more detail, according to CONSORT guidelines (Schulz 2010). The overall reporting quality was very poor and the risk of bias was difficult to assess since no information was available in many cases. This leads to conclusions that many trials had a high risk of bias but this may be reflecting the limited quality of reporting rather than the intervention delivery. The validation of smoking status was not a standard procedure in the trials as only 14 out of 37 (38%) described using any measure of biochemical validation. However, there were no differences between trials with validated or self‐reported smoking status in this review. Some studies provide data to apply post hoc ITT analysis in addition to reported completer results. Since we used such an approach the number of trials with ITT data (26 of 37, 70%) is an overestimation of the quality in publications.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

After a cardiac event about 30% to 50% of smokers with CHD quit without professional help. Additional psychosocial interventions show a superior quitting rate compared to usual care in the short‐term. Long‐term follow‐up showed an attenuation in the benefit of psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation but psychosocial smoking cessation intervention are still a promising strategy. Interventions for smoking cessation in CHD patients should last for more than 1 month. Brief interventions were not effective. The overall effect of psychosocial smoking cessation interventions in CHD patients can be expressed by the number needed to treat statistics with a figure of twelve if a spontanous quitting rate of 30% is assumed. This means that about fifteen patients had to be treated for one person to be abstinent from tobacco after 1 year (NNT = 14.9, CI 11.1 to 24.3). For intense intervention the NNT is somewhat lower (NNT = 11.9, CI 9.6 to 16.7).

Implications for research.

We found that the intensity of psychosocial interventions is of crucial importance for their efficacy. Approaches with very low intensity were not promising. Also the most recent large study (published in 2012) with a brief intervention did not find a significant effect. Future trials should also compare the additional benefits of combining NRT (or other pharmacological interventions such as bupropion) and psychosocial interventions, compared with NRT or psychosocial interventions alone in CHD patients. This would allow a comprehensive evaluation, since psychosocial interventions might increase abstinence per se but might also increase the efficacy of NRT itself by an increase of motivation for treatment (Heckman 2010).

In general more details on the intensity of the intervention (total duration, number of sessions, numbers of pages in leaflets etc) and the underlying theoretical approach are needed. We did not find any difference in the efficacy of different psychosocial approaches. Treatment differences might be blurred by difficulties in classifying studies due to limited reporting of the interventions. However, this result is in line with other studies of non‐pharmacological intervention namely in psychotherapy outcome research, where different interventions strategies showed no differences in their efficacy beyond chance in a various disorders (Wampold 1997), which was also supported in a recent network meta‐analysis on depression (Barth 2013). It is impossible to decide which type of intervention is most promising since direct comparison studies of different interventions are generally unavailable and the intervention itself can often not be classified adequately.

We had not been able to incorporate studies on economic outcomes since studies did not report on that. Any future trials should include such cost‐effectiveness analyses to help decision making for health care professionals also according to this outcome.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 July 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The addition of 21 trials did not change the short‐term findings. Psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation might also be effective in long‐term, but evidence is weak. |

| 24 October 2013 | New search has been performed | Updated search in January 2013. |

History

Review first published: Issue 1, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 3 October 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

Used abbreviations AMI: acute myocardial infarction AP: angina pectoris

BT: behavioral therapeutic intervention BIOSIS: database on life science and biomedical research (www.biosis.org) CABG: coronary artery bypass graft CHD: coronary heart disease CI: confidence interval

CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials EMBASE: database with biomedical and pharmacological information (www.embase.com) ICD: International Classification of Diseases ITT: intention to treat analysis

I²: I square, heterogeneity from 0 to 100. Medline: database of the U.S. National Library of Medicine MI: myocardial infarction MeSH; medical subject heading

MR: multi‐risk factor intervention N: number of studies n: number of patients

NRT: nicotine replacement therapy OR: odds ratio

Ph: support by phone PsycINFO: database of the American Psychological Association PSYNDEX: database of the Center for Psychological Information and Documentation at the University of Trier, Germany PTCA: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

RR: relative risk

SH: self‐help intervention

UK: United Kingdom

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank for the support of the Cochrane Heart Group, especially Fiona Taylor, Theresa Moore, Margaret Burke and Shah Ebrahim for comments on the protocol of our review and assistance in literature search. Many thanks to Corina Güthlin for her assistance in extracting the data of the initial review. Thanks to Jürgen Bengel for his contribution on the first version of this review. Thanks also go to Anna Hirsbrunner and Petra Büchler for support in managing references and checking accuracy of data entry, as well as to Jingying Wang for the data extraction of a Chinese study.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy 2013

CENTRAL

#1 MeSH descriptor Heart Diseases explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Coronary Artery Bypass explode all trees #3 angina* #4 cabg #5 coronary near bypass* #6 (coronary near disease*) or chd #7 (myocard* near infarct*) or (heart near infarct*) #8 (cardiac next disease*) or (heart next disease*) #9 acs #10 ami #11 cardiac near/2 inpatient* #12 cardiac near/2 in‐patient* #13 cardiac near/2 patient* #14 heart near/2 patient* #15 heart near/2 inpatient* #16 heart near/2 in‐patient* #17 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16) #18 MeSH descriptor Smoking Cessation, this term only #19 smok* near cessation #20 smok* near cease* #21 smok* near quit* #22 antismoking #23 anti‐smoking #24 smok* near giv* #25 smok* near stop* #26 (#18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25) #27 (#17 AND #26)

MEDLINE OVID

1. exp Heart Diseases/ 2. exp Coronary Artery Bypass/ 3. angina*.tw. 4. cabg.tw. 5. (coronary adj6 bypass*).tw. 6. (coronary adj6 disease*).tw. 7. (myocard* adj6 infarct*).tw. 8. (heart adj6 infarct*).tw. 9. chd.tw. 10. (heart adj disease*).tw. 11. (cardiac adj disease*).tw. 12. acs.tw. 13. ami.tw. 14. (cardiac adj2 inpatient*).tw. 15. (cardiac adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 16. (cardiac adj2 patient*).tw. 17. (heart adj2 patient*).tw. 18. (heart adj2 inpatient*).tw. 19. (heart adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 20. or/1‐19 21. Smoking Cessation/ 22. (smok* adj6 cessation).tw. 23. (smok* adj6 cease*).tw. 24. (smok* adj6 quit*).tw. 25. antismoking.tw. 26. anti‐smoking.tw. 27. (smok* adj6 giv*).tw. 28. (smok* adj6 stop*).tw. 29. or/21‐28 30. 20 and 29 31. randomized controlled trial.pt. 32. controlled clinical trial.pt. 33. randomized.ab. 34. placebo.ab. 35. drug therapy.fs. 36. randomly.ab. 37. trial.ab. 38. groups.ab. 39. 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 40. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 41. 39 not 40 42. 30 and 41 43. (20* not (2000* or 2001* or 2002*)).ed. 4. 42 and 43

EMBASE OVID

1. heart disease/ 2. coronary artery bypass graft/ 3. angina*.tw. 4. cabg.tw. 5. (coronary adj6 bypass*).tw. 6. (coronary adj6 disease*).tw. 7. (myocard* adj6 infarct*).tw. 8. (heart adj6 infarct*).tw. 9. chd.tw. 10. (heart adj disease*).tw. 11. (cardiac adj disease*).tw. 12. acs.tw. 13. ami.tw. 14. (cardiac adj2 inpatient*).tw. 15. (cardiac adj2 patient*).tw. 16. (heart adj2 patient*).tw. 17. (heart adj2 inpatient*).tw. 18. (heart adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 19. (cardiac adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 20. or/1‐19 21. smoking cessation/ 22. (smok* adj6 cessation).tw. 23. (smok* adj6 cease*).tw. 24. (smok* adj6 quit*).tw. 25. antismoking.tw. 26. anti‐smoking.tw. 27. (smok* adj6 giv*).tw. 28. (smok* adj6 stop*).tw. 29. or/21‐28 30. 20 and 29 31. random$.tw. 32. factorial$.tw. 33. crossover$.tw. 34. cross over$.tw. 35. cross‐over$.tw. 36. placebo$.tw. 37. (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. 38. (singl$ adj blind$).tw. 39. assign$.tw. 40. allocat$.tw. 41. volunteer$.tw. 42. crossover procedure/ 43. double blind procedure/ 44. randomized controlled trial/ 45. single blind procedure/ 46. 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 47. (animal/ or nonhuman/) not human/ 48. 46 not 47 49. 30 and 48 50. (20* not (2000* or 2001* or 2002*)).em. 51. 49 and 50

PsycINFO

1. exp heart disorders/ 2. angina*.tw. 3. cabg.tw. 4. (coronary adj6 bypass*).tw. 5. (coronary adj6 disease*).tw. 6. (myocard* adj6 infarct*).tw. 7. (heart adj6 infarct*).tw. 8. chd.tw. 9. (heart adj disease*).tw. 10. (cardiac adj disease*).tw. 11. acs.tw. 12. ami.tw. 13. (cardiac adj2 inpatient*).tw. 14. (cardiac adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 15. (cardiac adj2 patient*).tw. 16. (heart adj2 patient*).tw. 17. (heart adj2 inpatient*).tw. 18. (heart adj2 in‐patient*).tw. 19. or/1‐18 20. smoking cessation/ 21. (smok* adj6 cessation).tw. 22. (smok* adj6 cease*).tw. 23. (smok* adj6 quit*).tw. 24. antismoking.tw. 25. anti‐smoking.tw. 26. (smok* adj6 giv*).tw. 27. (smok* adj6 stop*).tw. 28. or/20‐27 29. 19 and 28 30. random$.tw. 31. factorial$.tw. 32. crossover$.tw. 33. cross‐over$.tw. 34. placebo$.tw. 35. (doubl$ adj blind$).tw. 36. (singl$ adj blind$).tw. 37. assign$.tw. 38. allocat$.tw. 39. volunteer$.tw. 40. control*.tw. 41. "2000".md. 42. or/30‐41 43. 29 and 42 44. (20* not (2000* or 2001* or 2002*)).up. 45. 43 and 44

Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) on Web of Science

#29 #28 AND #27 #28 TS=(random* or blind* or allocat* or assign* or trial* or placebo* or crossover* or cross‐over*) #27 #26 AND #18 #26 #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 #25 TS=(smok* SAME stop*) #24 TS=(smok* SAME giv*) #23 TS=anti‐smoking #22 TS=antismoking #21 TS=(smok* SAME quit*) #20 TS=(smok* SAME cease*) #19 TS=(smok* SAME cessation) #18 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 #17 TS=(heart SAME in‐patient*) #16 TS=(heart SAME inpatient*) #15 TS=(heart SAME patient*) #14 TS= (cardiac SAME patient*) #13 TS=(cardiac SAME in‐patient*) #12 TS=(cardiac SAME inpatient*) #11 TS=ami #10 TS=acs #9 TS="heart disease*" #8 TS="cardiac disease*" #7 TS=chd #6 TS=(heart SAME infarct*) #5 TS=(myocard* SAME infarct*) #4 TS=(coronary SAME disease*) #3 TS=(coronary SAME bypass*) #2 TS=cabg #1 TS=angina*

Appendix 2. Search strategy 2003

CENTRAL

#1 HEART DISEASES (exp MeSH) #2 CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS (exp MeSH) #3 angina* #4 cabg #5 (coronary near bypass*) #6 (coronary near disease*) #7 MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (exp MeSH) #8 (myocard* near infarct*) #9 (heart near infarct*) #10 chd #11 (heart next disease*) #12 (cardiac next disease*) #13 acs #14 ami #15 (cardiac next inpatient*) #16 (cardiac next patient*) #17 (heart next patient*) #18 (heart next inpatient*) #19 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9) #20 (#10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18) #21 (#19 or #20) #22 SMOKING CESSATION (exp MeSH) #23 (smoking near cessation) #24 (smoking near cease*) #25 (smoking near quit*) #26 antismoking #27 (anti next smoking) #28 (smoking near giv*) #29 (smoking near stop*) #30 (#22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29) #31 (#21 and #30)

MEDLINE, Pre‐MEDLINE, BIOSIS and Journals@Ovid

#1 (HEART DISEASES ) in KW,MESH,PS #2 (coronary artery bypass) in KW,MESH,PS #3 angina* #4 cabg #5 coronary near bypass #6 coronary near disease #7 (myocardial infarction) in KW,MESH,PS #8 myocard* near infarct* #9 heart near infarct* #10 chd #11 heart next disease* #12 acs #13 ami #14 cardiac next inpatient* #15 cardiac next patient* #16 heart next patient* #17 heart next inpatient* #18 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 #19 (smoking cessation) in KW,MESH,PS #20 smoking near cease* #21 smoking near cessation #22 smoking near quit #23 antismoking #24 anti next smoking #25 smoking near giv* #26 smoking near stop* #27 #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 #28 #18 and #27

EMBASE

#1 HEART DISEASES (exp MeSH) #2 CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS (exp MeSH) #3 angina* #4 cabg #5 (coronary near bypass*) #6 (coronary near disease*) #7 MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (exp MeSH) #8 (myocard* near infarct*) #9 (heart near infarct*) #10 chd #11 (heart next disease*) #12 (cardiac next disease*) #13 acs #14 ami #15 (cardiac next inpatient*) #16 (cardiac next patient*) #17 (heart next patient*) #18 (heart next inpatient*) #19 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9) #20 (#10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18) #21 (#19 or #20) #22 SMOKING CESSATION (exp MeSH) #23 (smoking near cessation) #24 (smoking near cease*) #25 (smoking near quit*) #26 antismoking #27 (anti next smoking) #28 (smoking near giv*) #29 (smoking near stop*) #30 (#22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29) #31 (#21 and #30)

PsycINFO

#1 TI coronary artery bypass Or AB coronary artery bypass Or MJ coronary artery bypass #2 TI angina Or AB angina OrMJ angina #3 TI cabg Or AB cabg Or MJ cabg #4 TI coronary Or AB coronary Or MJ coronary #5 TI bypass Or AB bypass Or MJ bypass #6 TI myocard Or AB myocard Or MJ myocard #7 TI myocard Or AB myocard Or MJ myocard #8 TI diseas* Or AB diseas*Or MJ diseas* #9 TI heart* Or AB heart* Or MJ heart* #10 TI chd Or AB chd OrMJ chd #11 TI acs Or AB acs Or MJ acs #12 TI ami Or AB ami Or MJ ami #13 TI cardiac Or AB cardiac Or MJ cardiac #14 TI patient* Or AB patient* OrMJ patient* #15 TI inpatient* Or AB inpatient* Or MJ inpatient* #16 TI smok* Or AB smok* Or MJ smok* #17 TI cessation Or AB cessation Or MJ cessation #18 TI cease* Or AB cease* Or MJ cease* #19 TI quit Or AB quit Or MJ quit* #20 TI anti Or AB anti Or MJ anti #21 TI giv* Or AB giv* Or MJ giv* #22 TI stop* Or AB stop* OrMJ stop* #23 (S5 And S4) #24 (S8And S4) #25 (S7 And S6) #26 (S9And S7 #27 (S14 And S13) #28 (S15 And S13) #29 (S14 And S9) #30 (S15 And S9) #31 (S30 Or S29 Or S28 Or S27 Or S26 Or S25 Or S24 Or S23 Or S15 Or S14 Or S13 Or S12 Or S11 Or S10 Or S9 Or S8 Or S7 Or S6 Or S5 Or S4 Or S3 Or S2 Or S1) #32 (S17 And S16) #33 (S18 And S16) #34 (S19 And S16) #35 (S20 And S16) #36 (S21 And S16) #37 (S22 And S16) #38 (S37 Or S36 Or S35 Or S34 Or S33 Or S32 Or S22 Or S21 Or S20 Or S19 Or S18 Or S17 Or S16) #39 (S37 Or S36 Or S35 Or S34 Or S33 Or S32) #40 (S13 Or S12 Or S11 Or S10 Or S9 Or S8 Or S7 Or S6 Or S5 Or S4 Or S3 Or S2 Or S1) #41 (S39 and S40)

PSYNDEXplus

#1 HEART DISEASES #2 CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS #3 angina* #5 coronary near bypass* #6 coronary near disease* #7 MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION #8 myocard* near infarct* #9 heart near infarct* #10 chd #11 heart next disease* #12 cardiac next disease* #13 acs #14 ami #15 cardiac next inpatient* #16 cardiac next patient* #17 heart next patient* #18 heart next inpatient* #19 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 #20 SMOKING CESSATION #21 smoking near cessation #22 smoking near cease* #23 smoking near quit* #24 antismoking #25 anti next smoking #26 smoking near giv* #27 smoking near stop* #28 #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 #29 herz #30 herzinfarkt #31 kardiovaskulaer* #32 KHK #33 myokard* #34 koronar* #35 bypass #36 #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 #37 raucherentwoehnung #38 tabakabstinenz #39 tabak near abstinenz #4 cabg #40 rauchen near abstinenz #41 rauchen near aufhoeren #42 #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 #43 #19 or #36 #44 #28 or #42 #45 #43 and #44

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Initial analysis: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence all trials.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer) | 40 | 7928 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.14, 1.35] |

Comparison 2. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on abstinence without outliers.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months (ITT preferred over completer) | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

Comparison 3. Forest plot: Stratified analysis by risk of bias indicators.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 1.1 adequate sequence generation | 18 | 5046 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.07, 1.36] |

| 1.2 inadequate sequence generation | 19 | 2636 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.12, 1.37] |

| 2 Abstinence 6 to 12 months | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 2.1 adequate allocation concealment | 13 | 4784 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.09, 1.34] |

| 2.2 inadequate allocation concealment | 24 | 2898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.11, 1.38] |

| 3 Abstinence 6 to 12 months | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 3.1 adequate incomplete outcome data | 26 | 6436 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [1.09, 1.28] |

| 3.2 inadequate incomplete outcome data | 11 | 1246 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [1.12, 1.65] |

| 4 Abstinence at 6 to 12 months | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 4.1 validated outcome measures | 13 | 2803 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.07, 1.39] |

| 4.2 non‐validated outcome measures | 24 | 4879 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [1.12, 1.35] |

Comparison 4. Forest plot: Stratified analysis by type of intervention (6 to 12 months).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months BEHAVIORAL THERAPY | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 1.1 Behavioral therapeutic approach | 20 | 5170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [1.12, 1.34] |

| 1.2 No behavioral therapeutic approach | 17 | 2512 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.07, 1.39] |

| 2 Abstinence 6 to 12 months TELEPHONE SUPPORT | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 2.1 Telephone support | 26 | 5807 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.12, 1.30] |

| 2.2 No telephone support | 11 | 1875 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.04, 1.54] |

| 3 Abstinence 6 to 12 months SELF HELP MATERIALS | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [1.14, 1.34] |

| 3.1 SELF HELP MATERIALS provided | 18 | 3789 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.12, 1.33] |

| 3.2 No self help materials | 19 | 3893 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.09, 1.46] |

| 4 Abstinence 6 to 12 months Specific vs. Multi‐Risk‐Factor Intervention | 37 | 7682 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 4.1 Specific smoking cessation intervention | 17 | 5345 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.11, 1.42] |

| 4.2 Multi risk factor intervention | 20 | 2337 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.08, 1.32] |

Comparison 5. Sensitivity analysis brief / intense intervention (6 to 12 months).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence 6 to 12 months all studies | 36 | 7661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.13, 1.32] |

| 1.1 brief intervention | 5 | 2693 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.91, 1.12] |

| 1.2 high intensity intervention | 31 | 4968 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.17, 1.40] |

Comparison 6. Forest plot: Efficacy of psychosocial interventions on long‐term abstinence.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence more than 12 months (completer only) | 7 | 741 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.02, 1.31] |

| 2 Abstinence more than 12 months (ITT only) | 5 | 854 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.92, 1.28] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Allen 1996.

| Methods | Completer Analysis | |

| Participants | 138 women who underwent first‐time CABG at a hospital. IG: 14 smokers CG: 11 smokers | |

| Interventions | Usual care: patient education and instructions for exercise. Psychosocial intervention: nurse‐directed multimodal behavioural program based on social cognitive theory (videotape, workbook, counselling). Started with discharge from hospital, two updates 1 and 2 months later (BT, Ph, SH, MR, Intensity 4) | |

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 12 months (abstinence self report) | |

| Notes | IG: Completer = 64.3% CG: Completer = 54.5% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerized schema that achieved a balanced allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear information available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

Benner 2008.

| Methods | Completer Analysis | |

| Participants | patients with an increased cardiovascular risk, not necessarily CHD in all cases. IG: 273 smokers CG: 257 smokers |

|

| Interventions | Usual care: predicted Framingham 10‐year risk of CHD was calculated but was not communicated to either the physician or the patient until the final visit Psychosocial intervention: patients were advised according to a CHD risk evaluation and communication programme. They received a Heart Health Report and had three follow‐up phone calls by a physician or study nurse and the patients completed a "Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior" (KAB) questionnaire. (Ph, MR, Intensity 4) |

|

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 6 month (abstinence self‐report) | |

| Notes | IG: Completer = 56.4% CG: Completer = 38.5% |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐based algorithm |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Random permutation of 100 numbers |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | No data on ITT available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

Blasco 2012.

| Methods | ITT | |

| Participants | 203 acute coronary syndrome patients IG: 78 smokers CG: 75 smokers |

|

| Interventions | Usual care: written recommendations and verbal information about CVD prevention only Psychosocial intervention: written recommendations and verbal information about CVD prevention. Patients received an automatic sphygmomanometer, a glucose and lipid meter and a cellular phone. Results were sent through their mobile phones and a cardiologist then sent individualised short messages with recommendations to the patients during the 12‐month follow‐up period. (Ph, MR, Intensity 5) |

|

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 12 month (validation by 1‐step cotinine immunoassay in urine) | |

| Notes | IG: ITT = 80.8% CG: ITT = 81.3% |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Two different randomisation lists |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

Bolman 2002a.

| Methods | Completer Analysis, ITT | |

| Participants | Hospitalised smokers with multiple coronary disorders IG: 132 smokers CG: 211 smokers |

|

| Interventions | Usual care: no systematic attention was given to smoking Psychosocial intervention: C‐Mis which consisted of stop‐smoking advice by the cardiologist followed by 15‐30min of standardised individual counselling and the provision of self‐help material by the ward nurse and aftercare by the cardiologist. After that more in‐depth counselling, which was attuned to the patient's stage of change. (BT, SH, Specific, Intensity 4) |

|

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 3 and 12 months (abstinence self‐report) | |

| Notes | IG: Completer = 58.0% ITT = 38.6% CG: Completer = 45.4% ITT = 77.3% |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The whole hospital was randomised with significant difference between the two groups at the process evaluation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | No data on ITT available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

Burt 1974.

| Methods | Completer Analysis | |

| Participants | 280 men in a coronary care unit with AMI IG: 125 smokers CG: 98 smokers | |

| Interventions | Usual care: conventional advice to stop smoking by physician. Psychosocial intervention: information about the effects of smoking by physician and nurse, reinforced by a booklet about coronary‐risk factors. Continued in follow‐up clinic and through a community nurse. (Specific, Intensity 5) | |

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 12 months (abstinence self‐report) | |

| Notes | IG: Completer = 63.2% CG: Completer = 27.5% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation according to the day of admission |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | The group allocation can be foreseen from the day of admission |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | No data on ITT available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

Carlsson 1997.

| Methods | Completer | |

| Participants | 168 patients with AMI admitted to the coronary care unit at Malmö General Hospital IG: 32 smokers CG: 35 smokers | |

| Interventions | Usual care: two visits to general practitioner. Psychosocial intervention: nurse‐directed secondary prevention unit after the usual follow‐up schedule: education and counselling (individual and group sessions) about smoking, exercise, nutrition for about 9 hours and exercise training 2‐3 times per week. Visits to cardiologist after 2, 3, 6 months and to nurse after 3, 5, 6, 9, 12 months. (MR, Intensity 5) | |

| Outcomes | Follow‐up at 12 months (abstinence self‐report) | |

| Notes | IG: Completer = 50% CG: Completer = 25.7% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding in general not possible in psychosocial interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemically validated outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | No data on ITT available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Always rated as unclear, since no protocol information was available in any study |

CASIS 1992.

| Methods | Completer, ITT | |

| Participants | 267 smokers with CAD of 3 hospitals who scheduled for coronary arteriography IG: 135 smokers CG: 132 smokers | |

| Interventions | Usual care: brief advice from physician to stop smoking. Psychosocial intervention: intervention provided by trained behaviorally oriented health educators: inpatient counselling session (30 min), outpatient counselling visits and telephone calls (at 1and 3 weeks, abstinent smokers at 3 months, relapsed smokers at 2 and 4 months), outpatient group program, self‐help materials. (BT, Ph, SH, Specific, Intensity 4) | |