Abstract

We mapped and cloned SKI6 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a gene that represses the copy number of the L-A double-stranded RNA virus, and found that it encodes an essential 246-residue protein with homology to a tRNA-processing enzyme, RNase PH. The ski6-2 mutant expressed electroporated non-poly(A) luciferase mRNAs 8- to 10-fold better than did the isogenic wild type. No effect of ski6-2 on expression of uncapped or normal mRNAs was found. Kinetics of luciferase synthesis and direct measurement of radiolabeled electroporated mRNA indicate that the primary effect of Ski6p was on efficiency of translation rather than on mRNA stability. Both ski6 and ski2 mutants show hypersensitivity to hygromycin, suggesting functional alteration of the translation apparatus. The ski6-2 mutant has normal amounts of 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits but accumulates a 38S particle containing 5′-truncated 25S rRNA but no 5.8S rRNA, apparently an incomplete or degraded 60S subunit. This suggests an abnormality in 60S subunit assembly. The ski6-2 mutation suppresses the poor expression of the poly(A)− viral mRNA in a strain deficient in the 60S ribosomal protein L4. Thus, a ski6 mutation bypasses the requirement of the poly(A) tail for translation, allowing better translation of non-poly(A) mRNA, including the L-A virus mRNA which lacks poly(A). We speculate that the derepressed translation of non-poly(A) mRNAs is due to abnormal (but full-size) 60S subunits.

The 5′ end of eucaryotic mRNA has a cap structure of the form m7G5′ppp5′Xp, while the 3′ end is polyadenylated. Both of these structures are essential for efficient translation and mRNA stability. The requirement for cap and poly(A) structure for messenger expression constitutes a handicap for RNA viruses whose mRNA is not made by the cellular machinery. L-A virus mRNA lacks both 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) structures (4, 52), and its cytoplasmic location makes it unlikely that it can use cellular enzymes to modify its mRNA. Indeed, translation plays a large role in the interactions of the L-A double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus with its host, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (reviewed in references 11, 22, 32, and 58). L-A has two overlapping open reading frames, gag, encoding the major coat protein, and pol, encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and packaging function. L-A uses a −1 ribosomal frameshift to make a Gag-Pol fusion protein, and the efficiency of this frameshift is critical for viral propagation (12–14).

Many viruses adopt a variety of tricks to acquire a cap or poly(A) structure. Influenza viruses and Bunyaviruses steal caps from cellular mRNAs; reoviruses, rhabdoviruses, and togaviruses encode their own capping enzymes; and Picornaviridae carry out cap-independent translation (15, 32). Picornaviruses, togaviruses, influenza viruses, and many other RNA viruses have an encoded sequence that is copied to produce mRNA with a 3′ poly(A) structure, while rhabdoviruses have no encoded poly(A) but add it enzymatically to their transcripts. However, reoviruses and many plant virus mRNAs lack a 3′ poly(A).

The apparent lack of 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) does not prevent L-A from being highly expressed. However, this lack of both structures makes L-A mRNA expression sensitive to chromosomal mutations affecting functions related to cap or poly(A). Accordingly, studies of L-A have secondarily brought insights into the roles of cap and poly(A).

For instance, the SKI genes (named SKI for superkiller) were identified by the superkiller phenotype of mutants (45, 53). The L-A particles can separately encapsidate a satellite dsRNA, called M dsRNA, encoding a secreted protein toxin (the killer toxin). ski mutants have higher copy numbers of M1 and L-A dsRNAs and so make more killer toxin (1). SKI1 later proved to be XRN1, encoding the 5′→3′ exoribonuclease specific for uncapped RNA and responsible for the major pathway of mRNA decay (21, 23, 37, 50, 51). It is evident how the uncapped L-A mRNA would be affected by this protein. To subvert the Ski1p/Xrn1p nuclease, the L-A major coat protein has a decapping activity which decapitates some cellular mRNAs to partially distract the nuclease from working on the capless L-A mRNA (2, 3, 31).

While SKI1 concerns RNA stability, SKI2, SKI3, and SKI8 encode a system that blocks the translation of non-poly(A) [poly(A)−] mRNA (31). ski2, ski3, or ski8 mutants translated electroporated C+ A− [Cap+ poly(A)−] mRNA nearly as well as C+ A+ mRNA. Both physical and functional stabilities of the electroporated mRNA showed little effect from these mutations. Ski3p is a 163-kDa nuclear protein (44), while Ski2p is an RNA helicase with a glycine-arginine-rich domain typical of nucleolar proteins and is homologous to a human nucleolar protein (7, 28, 61). Ski8p has two copies of the β-transducin (WD) repeat sequence but otherwise has no close homologs (33). This suggested to us that the effects of ski2 and ski3 (and ski8) on expression of poly(A)− mRNAs might best be explained by a function taking place in the nucleus.

Strains with mutations in any of more than 20 genes resulting in deficiency of 60S ribosomal subunits are defective in viral propagation (5, 41). Mutations in ski2, ski3, or ski8 suppress the effect of 60S subunit deficiency on viral propagation (31, 54). We adopted a model in which 60S interaction with poly(A) is a prerequisite for joining 40S subunits waiting at the initiator AUG (reviewed in reference 22), and these SKI products mediate this effect by a role in 60S subunit biogenesis (31, 41). This model explains why a deficiency of 60S subunits impairs viral propagation more than cell growth, why ski mutants show increased virus copy number and expression, and why ski mutations suppress mutations producing deficiency of 60S subunits.

SKI6 genetically resembles SKI2, SKI3, and SKI8 (45). Here, we show that SKI6 encodes an essential 246-residue protein homologous to several bacterial RNase PHs, an enzyme responsible for processing the 3′ end of pre-tRNAs. We find that ski6-2 results in derepression of translation of non-poly(A) mRNA and hypersensitivity to the antibiotic hygromycin. The ski6 mutation suppresses the effect of 60S subunit deficiency on viral propagation. Polysome gradients reveal a novel 38S particle in ski6-2 mutants which contains a fragment of 25S rRNA and lacks 5.8S rRNA. These findings provide direct evidence that Ski6p is involved in 60S ribosomal subunit biogenesis and, perhaps through this, affects translation of non-poly(A) mRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic mapping of SKI6.

M2 dsRNA is a killer toxin-encoding satellite of the L-A virus, meaning that its coat protein and replication proteins are encoded by L-A. At temperatures of 32°C or higher, M2 propagation depends on two genes, called MKT1 and MKT2 (maintenance of K2), which are not needed by M1 dsRNA (59, 60). Mutations in the SKI genes suppress this requirement of M2 for MKT genes (45). Many laboratory strains carry mkt1 mutations, and some have mkt2 mutations. We crossed mkt1 ski6 M2 strains with a set of multiply marked strains designed for genetic mapping (18) which proved to also be mkt1. We found ski6 tightly linked to ade3 (parental ditype = 58, nonparental ditype = 0, tetratype = 10, 7.3 centimorgans) on the right arm of chromosome VII.

Cloning of SKI6.

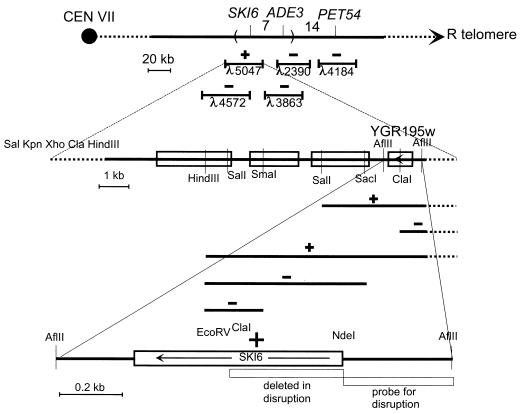

Strain RV493 (= MATa ura3 ade3 his− leu2 trp1 ski6-2 mkt1 L-A-HN M2) is stably K2+ at either 25 or 32°C, but if it becomes SKI+, then it will be K2− after growth at 32°C. Several λ clones of yeast DNA located around ADE3 (46) were tested by cotransformation of λ clone DNA and plasmid pBM2240 cut with EcoRI and XhoI (16). pBM2240 has homology with the arms of the λ clone, and the linearized plasmid can replicate only by recombining with the λ clone in such a way as to transfer the insert into the plasmid pBM2240 (16). The transformants were first isolated at 25°C, grown at 25 or 32°C, and then tested for killer activity. Only λ5047 gave recombinants which complemented ski6-2 (see Fig. 1). The pBM2240 derivative carrying the insert of λ5047 was isolated, and subclones were made by cleavage with HindIII and ligation to pRS316 cut with the same enzyme. One of these subclones, 5047H8, complemented ski6-2. 5047H8 was cut with SpeI, SacI, SalI, ClaI, or XhoI, followed by ligation. The ends of several of these clones were sequenced and found to be included in the 9-kb region sequenced by Guerreiro et al. (20). Only the SalI-cut and religated derivative of 5047H8 complemented ski6-2, suggesting that the open reading frame (ORF) designated YGR195w was SKI6 (see Fig. 1). This was confirmed by cloning the 1,283-bp AflII-AflII fragment (blunt ended with Klenow fragment) containing YGR195w from the SalI derivative of 5047H8 into pRS316 cut with SmaI and showing that the resulting plasmid, pSKI6, complements ski6-2 (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Cloning of SKI6. The location of SKI6 was determined on the linkage map, and genomic clones in this area were screened for complementation (see text). Complementation tests of subclones localized SKI6 to YGR195w. The region deleted in the ski6::HIS3 disruption and the probe used are shown.

Plasmid constructions.

To make a disruption of SKI6, the AflII-AflII fragment containing SKI6 was inserted in a Bluescript vector, making pSK+SKI6, and the HIS3 gene on a SmaI-PvuII fragment from pJJ215 (24) was inserted into pSK+SKI6 cut with NdeI (blunt ended with Klenow fragment) and EcoRV, replacing a 369-bp segment of SKI6 (Fig. 1). The resulting pSK+ski6::HIS3 plasmid was digested with NaeI and SacI and used to transform the diploid strain 2959 × 2966 (=MATa/MATα his3/his3 trp1/trp1 ura3/+ +/leu2 L-A-HN M2). To confirm the disruption, chromosomal DNA was isolated, digested with HindIII, blotted onto a nitrocellulose filter, and probed with the 353-bp AflII-NdeI fragment. The probe detected an 8.2-kb fragment in the normal sequence and a 2.4-kb fragment in the disrupted sequence. The disrupted diploid 2959 × 2966 ski6::HIS3 segregated two viable His+ spores with the undisrupted pattern to two inviable spores. Diploid disruptants showed both undisrupted and disrupted bands.

Expression of luciferase mRNAs.

The luciferase mRNA expression plasmids T7 LUC [poly(A)−] and T7 LUC50 [50-mer poly(A) tail] have been described previously (19). For RNA synthesis, T7 LUC was linearized with SmaI and T7 LUC50 was linearized with DraI. Transcripts were synthesized with the Ambion MEGAscript transcription kit in the presence or absence of the cap analog m7GpppG in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After DNase I treatment followed by precipitation with LiCl, RNAs were passed over G-50 columns (5 Prime-3 Prime Inc. SELECT-B). RNA was quantitated both by measuring the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) and by a comparison on agarose gels with known concentration standards.

RNA electroporation was done as described previously (17) with minor modifications. Cells for spheroplast preparations were grown in selective medium (H-Ura). After lyticase treatment, cells were incubated for 2 h in YPAD-sorbitol medium to make them metabolically active. Two micrograms of RNA was used for electroporation, and cells were assayed for luciferase activity after 2 h (or as indicated) of outgrowth at 30°C in YPAD-sorbitol medium. Luciferase activity was assayed as previously described (31) with a buffer containing coenzyme A.

Stability of electroporated RNA and luciferase accumulation.

The method for determination of stability of electroporated RNA and luciferase accumulation is identical to that described previously (31) except that collected spheroplasts were quickly washed twice with 0.5 ml of 1 M sorbitol, and resulting pellets were frozen in a dry ice-ethanol mix. For every time and strain, two samples were collected. One pellet was used for a luciferase assay, and the other was used to extract RNA.

Yeast extracts, polysome preparation, and analysis.

Cell lysis was done by a modification of a published protocol (40). Cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) was added to a 200-ml cell culture at 30°C in H-Ura at an OD600 of 0.4 or 0.5. For growth at the nonpermissive temperature, cells were grown first at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.05 to 0.1 and then at 39°C for 8 h. The culture was quickly cooled in ice water after cycloheximide was added and then centrifuged and washed in 20 ml of buffer A containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5 with KOH), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 100 μg of cycloheximide per ml (water was treated with diethylpyrocarbonate). After a quick centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 0.6 ml of buffer A. A 1.4-g amount of glass beads (Biospec Products) was added, and cell lysis was performed by bead beating twice for 30 s each time (with intermittent cooling) in a minibead beater (Biospec Products). After lysis, the cell extract was clarified for 5 min at full speed in a microcentrifuge. Twenty-five OD260 units of each lysate was centrifuged through 11 ml of 10 to 50% linear sucrose gradients containing buffer A without dithiothreitol or cycloheximide. For a plain polysome profile, gradients were centrifuged for 2.5 h at 39,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor at 4°C. To obtain better resolution of species around 40S, centrifugations at 27,000 rpm for 14 h were done. Gradients were run at 4°C through a UV ISCO type 6 monitor reading OD254.

Northern hybridization.

While gradients were read, fractions (0.5 ml) were collected and kept cool before an RNA extraction was performed. RNA was extracted by adding 50 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), vortexing, and adding 550 μl of phenol previously equilibrated in buffer AE (50 mM Na acetate [pH 5.3], 10 mM EDTA). After vortexing, the tubes were incubated at 65°C for 4 min and then frozen in a dry ice-ethanol mix, followed by a 6-min centrifugation at room temperature. A second extraction with 600 μl of phenol-Tris-EDTA-chloroform was performed, RNA from 400 μl of supernatant was precipitated with 40 μl of 3 M Na acetate (pH 5.3) and 2.5 volumes of ethanol and centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min, and the pellet was washed in 80% ethanol. From each RNA pellet resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-water, one-fifth was loaded on a 1.4% agarose gel containing formamide. The size-fractionated RNA was blotted onto a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham). Hybridization to end-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide probes was carried out at 30°C overnight in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–5× Denhardt’s solution–0.5% SDS–1 mM EDTA. The filters were washed successively at 30°C in 5× SSC–0.1% SDS and then in 1× SSC–0.1% SDS (and 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS if a background persisted).

Total RNA extracts were obtained from 30 ml of cell cultures (OD600 = 0.4) grown at 30°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 400 μl of buffer AE, and RNA was extracted as previously mentioned. Northern blot analysis was performed as described above, except that 30 μg of RNA for each strain was loaded on a 4% agarose gel (Nusieve GTG; FMC BioProducts). The probes used were p18S (5′CGTCCTATTCTATTATTCCATG3′), p5.8S (5′TTTCGCTGGGTTCTTCATC3′), p25S (5′GCCCGTTCCCTTGGCTGTG3′) (complementary to 25S rRNA bases 2359 to 2377), p25S5′ (5′GCGGGTACTCCTACCTGATTTGAGGTC3′) (complementary to 25S rRNA bases 5 to 31), and p25S3′ (5′CAGCAGATCGTAACAACAAGGCTACTCTAC3′) (complementary to bases 3336 to 3365).

Drug hypersensitivity test.

Isogenic wild-type and ski6 cells growing in selective medium (H-Ura) in log phase were diluted to OD600s of 0.15, 0.015, and 0.0015, and 5-μl aliquots were spotted on selective plates (H-Ura) with and without drug (the viabilities of both strains appeared to be identical and proportional to the measured OD on YPAD and H-Ura media). In the experiment shown, concentrations of hygromycin B, paromomycin, and cycloheximide of 50 μg/ml, 300 μg/ml, and 100 ng/ml (concentrations twofold higher prevented the growth of both strains), respectively, were used. The wild-type strain, 3221 (61), and an isogenic ski2 disruptant (ski2::HIS3) were tested in the same manner on YPAD plates with or without drug.

RESULTS

SKI6 is an essential gene, and Ski6p is homologous to tRNA- processing enzymes and to proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans and Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

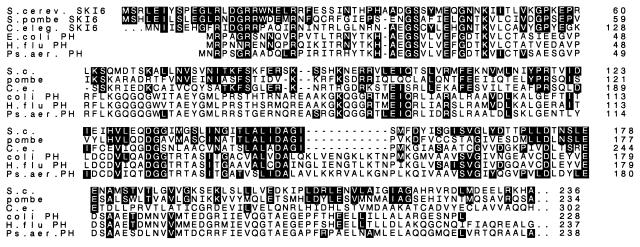

We genetically mapped SKI6, finding it tightly linked to ADE3 on chromosome VII. We obtained λ clones (46) including this small area and cloned the gene from one of them (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1). Since the gene complementing the ski6 mutation was obtained from DNA mapping close to ADE3, we have cloned SKI6 and not a suppressor. Sequence analysis shows that the 246-residue Ski6 protein is most closely related to proteins encoded by uncharacterized ORFs found in S. pombe and C. elegans (Fig. 2). These proteins are similar through most of their sequences except for the C. elegans SKI6 homolog, which has an N-terminal extension beyond the region of homology. Ski6p is also more distantly related to Mtr3p, a nucleolar protein required for mRNA export from the nucleus (25).

FIG. 2.

Ski6 protein is homologous to tRNA-processing enzymes of bacteria (9, 27) and proteins encoded by uncharacterized ORFs of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (pombe; GenBank accession no. D89141) (64) and Caenorhabditis elegans (C. eleg. or C. e.; EMBL accession no. Z49909) (62). S.c. or S. cerev., S. cerevisiae; coli or E. coli, Escherichia coli; H. flu, Haemophilus influenzae; Ps. aer., Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Ski6p also has homology to several tRNA-processing enzymes from bacteria, the RNase PH group. These are phosphate-dependent enzymes involved in the removal of the last few 3′ nucleotides from tRNA precursors (10, 26, 27). They are highly specific in their action and work together with other nucleases in trimming the 3′ end of the pre-tRNA molecule. They resemble polynucleotide phosphorylase in producing nucleoside diphosphates from RNA and phosphate and in their ability to synthesize RNA from nucleoside diphosphates (26). Ski6p has weaker similarity to Bacillus subtilis polynucleotide phosphorylase. We have not tested whether ski6 mutations affect tRNA processing, but we present evidence below that they do affect ribosome biogenesis.

A deletion-substitution mutation was produced by replacing the NdeI-EcoRV fragment of SKI6 extending from just upstream of the AUG to codon 122 with the HIS3 gene. The meiotic tetrads produced two viable His− spores:two inviable spores (15 of 16 tetrads examined), indicating that SKI6 is an essential gene. The ski6-2 mutant strains are temperature sensitive for growth at 39°C, and the temperature sensitivity is complemented by our clone of SKI6. In liquid culture, ski6-2 cells gradually stop growth after about three doublings, with no unique morphology of the arrested cells. Revertants do not appear on plating a ski6 mutant at 39°C on rich medium.

Thus, SKI6, whose mutation, like ski1, ski2, ski3, and ski8, increases expression of the uncapped, nonpolyadenylated viral mRNAs, is an essential gene with similarities to sequences corresponding to known 3′→5′ exonucleases. Ski6p might act on stability of mRNAs (on the Ski1p model) or on translation (like Ski2p, Ski3p, and Ski8p).

Ski6p blocks translation of non-poly(A) mRNA.

We used electroporation of luciferase mRNAs to study the effect of a ski6-2 mutation (Table 1). In a wild-type strain, cap+ poly(A)+ mRNA was translated 33 times better than cap+ poly(A)− mRNA (Table 1). In the isogenic ski6-2 strain, the poly(A)+ mRNA was translated only three times better than poly(A)− mRNA. Thus, the ski6-2 mutation increases the efficiency of translation of C+ A− mRNA 10-fold. A similar effect on C− A− mRNA translation was also seen, with an eightfold increase in translation in the ski6-2 strain (Table 1). In contrast, there is no effect of the ski6-2 mutation on translation of C− A+ mRNA (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Translation of electroporated luciferase mRNAsa

| Strain | Expt no. | Luciferase activityb for phenotype of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C+ A+ | C+ A− | C− A+ | C− A− | ||

| ski6-2 pSK16 (SKI+) | 1 | 39.5 | 1.22 | 9.05 | 0.46 |

| 39.6 | 1.07 | 9.22 | 0.38 | ||

| 39.8 | 1.14 | 9.15 | 0.37 | ||

| 2 | 39.6 | 1.35 | 11.0 | 0.43 | |

| 39.8 | 1.32 | 11.4 | 0.45 | ||

| 39.8 | 1.31 | 11.4 | 0.45 | ||

| 3 | 41.4 | 1.17 | 8.9 | 0.34 | |

| 42.5 | 1.23 | 9.2 | 0.32 | ||

| Avg | 40.4 | 1.22 | 9.8 | 0.39 | |

| ski6-2 pRS316 (ski6) | 1 | 32.9 | 9.3 | 11.1 | 2.31 |

| 33.1 | 9.3 | 11.1 | 2.29 | ||

| 33.1 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 2.20 | ||

| 2 | 29.4 | 10.5 | 14.3 | 2.26 | |

| 27.5 | 10.5 | 14.0 | 2.35 | ||

| 27.5 | 10.5 | 14.0 | 2.35 | ||

| 3 | 30.4 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 2.28 | |

| 31.2 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 2.31 | ||

| Avg | 30.6 | 9.6 | 11.7 | 2.29 | |

| ski6/SKI+ ratioc | 0.76 (1.0) | 7.9 (10.4) | 1.19 (1.56) | 5.9 (7.8) | |

Strain RV493 (K2−) carrying either pSKI6 (SKI+) or the vector pRS316 (ski6) was grown at 30°C in H-Ura and electroporated with 2 μg of luciferase mRNAs prepared with (C+) and without (C−) 5′ cap and with (A+) or without (A−) 3′ poly(A) as described in Materials and Methods.

Luciferase activity is expressed in light units per microgram of protein. The blank is <0.01 light unit.

This row of data shows the ski6/SKI+ ratio normalized on the assumption that this ratio is 1.0 for C+ A+ mRNA.

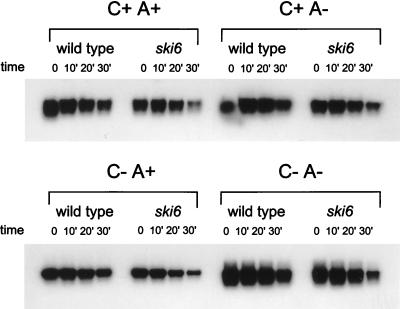

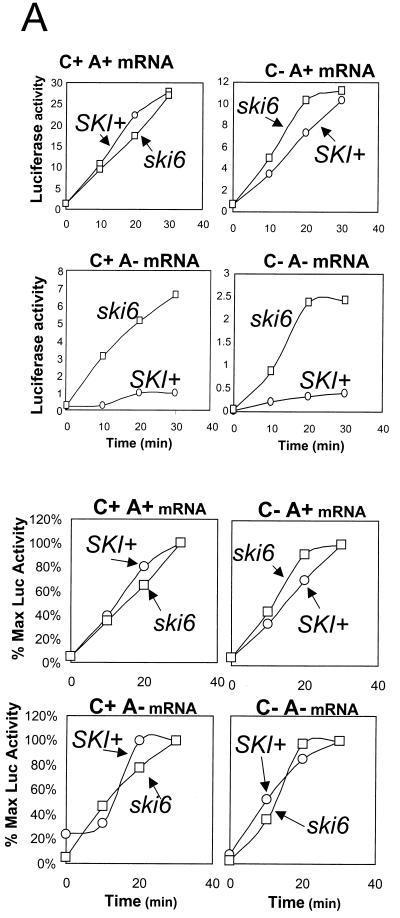

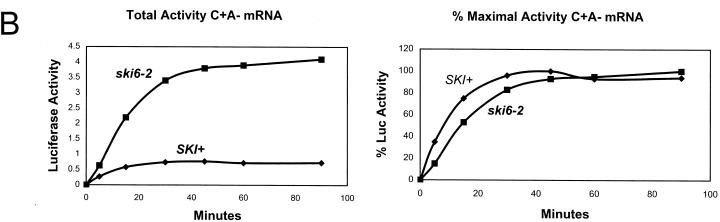

Since the poly(A) structure is important in both translation and stability (reviewed in reference 22), we examined luciferase mRNA stability by direct assay of both structural integrity (Fig. 3) and functional integrity (Fig. 4). Radiolabeled mRNAs were electroporated into cells and incubated as they were for translation, samples were taken periodically, the cells were washed, and RNA was extracted. The amount of intact mRNA remaining was determined by electrophoresis and autoradiography (Fig. 3). Quantitation of the autoradiograms showed that each form of the luciferase mRNA was, if anything, more stable in the wild type than in the ski6-2 mutant, suggesting that mRNA turnover was not the basis of better expression in the mutant. However, since we could not determine into what compartments the electroporated mRNAs had been delivered, we examined the functional integrity of the luciferase mRNAs by measuring the kinetics of luciferase synthesis with the same samples (Fig. 4). This tests the stability of those mRNA molecules with access to the translation apparatus. For the poly(A)+ mRNAs, the kinetics of synthesis by mutant and wild type were similar. For the mRNAs lacking poly(A), synthesis was greater in the ski6 strain from the earliest time points, indicating a difference in translation rather than in mRNA stability. Plotted as percent maximal activity, the wild-type strain showed the same pattern as did the ski6 strain. If mRNA instability in the wild type were the cause of the reduced expression of the non-poly(A) mRNAs, it would quickly reach 100% maximal expression and then stop, while the ski6 mutant would continue expression (19). This was not observed (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

SKI6 does not affect stability of electroporated luciferase mRNA. Labeled mRNA was electroporated into wild-type and ski6-2 cells. The kinetics of luciferase synthesis (Fig. 4) and mRNA degradation were determined on portions of the same samples taken at 0, 10, 20, and 30 min. Extracted RNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and autoradiography as described previously (31).

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of luciferase accumulation in ski6-2 and SKI+ cells indicates an effect on translation rather than mRNA degradation. (A) Kinetics of luciferase activity accumulation are plotted in the upper panels (luciferase activity in light units per microgram of protein), and percent maximal luciferase activity (% Max Luc Activity) is plotted in the lower panels. (B) Comparison of ski6-2 and SKI+ cells in translation of C+ A− mRNA over a 90-min time course. If accumulation were low in wild-type cells for C+ A− or C− A− mRNAs because of mRNA degradation, then activity would accumulate rapidly and stop at later time points. The plateau (100%) would be expected early. In fact, the kinetics as percent maximal activity are similar for SKI+ and ski6 strains for all types of mRNA. The differences in rates of accumulation must be due to differences in translation rate. The percentage was calculated as follows: 100 {[(value at time t) − (value at t = 0)]/[30-min value]}.

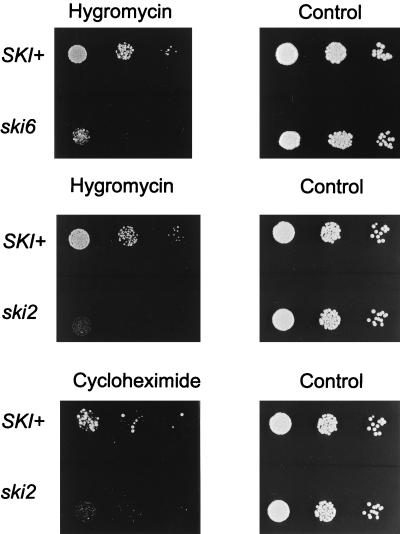

Antibiotic sensitivity of ski6 mutants.

Many mutations affecting components of the translation apparatus produce hypersensitivity to hygromycin B (6, 49) and other drugs that increase translational errors (30). We found that ski6-2 strains are hypersensitive to hygromycin B (Fig. 5), supporting the notion that they affect translation. We also found that ski2 strains are hypersensitive to hygromycin B and slightly hypersensitive to cycloheximide (Fig. 5). Neither ski2 nor ski6 mutants are hypersensitive to paromomycin (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Drug sensitivity assay. Different dilutions of log-phase cultures were tested for their sensitivities to hygromycin B or cycloheximide (see Materials and Methods).

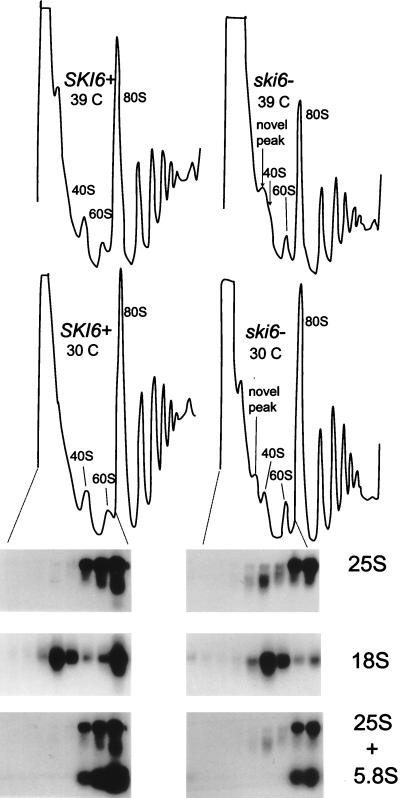

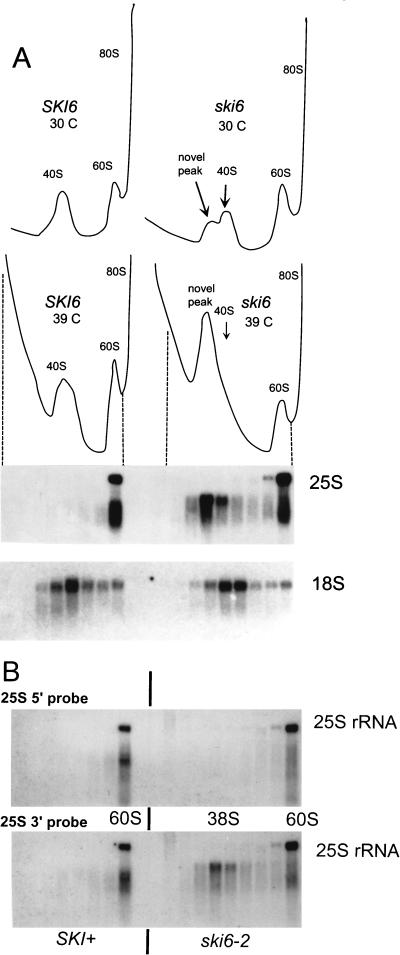

ski6 mutants have a novel 25S rRNA-containing particle.

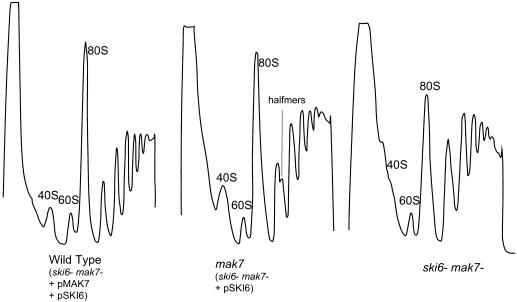

At 30°C, growth rates of the isogenic ski6 and wild-type strains are almost identical, although the ski6 mutant shows a greater delay in leaving stationary phase than does the wild type. The amount of polysomes in ski6 strains is consistently lower than that in the wild-type (Fig. 6). The normal growth rates imply that translation is proceeding at an essentially normal rate, although, as shown above, non-poly(A) mRNAs are more translatable in ski6 cells under these conditions. In cells grown at 30°C, the polysome gradients reveal the existence of an extra peak in the ski6 strain, sedimenting slightly slower than the 40S subunits (Fig. 6 and 7). This 38S extra peak is most clearly distinguished from the 40S ribosomal subunit in longer centrifugation runs (Fig. 7). The amount of this extra peak is increased by a shift of temperature to 39°C, the nonpermissive temperature, and the mutant stops growing after three more generations. The ratio of polysomes in ski6-2 cells to those in SKI+ cells is similar at 39°C to the ratio at 30°C (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

ski6-2 cells show a novel species of rRNA whose origin is 25S rRNA. Polysome profiles of ski6-2 (ski6−) and wild-type (SKI6+) cells grown at either 30 or 39°C are shown. The A260 is plotted on the vertical axis. Northern analysis of fractions from polysome profiles at 30°C were made by using probes for 25S (p25S), 18S (p18S), or 5.8S (p5.8S) rRNAs (see Materials and Methods).

FIG. 7.

(A) Long-term centrifugation on sucrose gradients allows a better separation of the novel 38S species from the usual 40S peak. The A260 is plotted on the vertical axis. Northern analysis of fractions from polysome profiles at 39°C was done by using probes against the 25S (p25S) and 18S (p18S) rRNAs (see Materials and Methods). The dashed lines show the points on the UV scan corresponding to the fractions analyzed by Northern hybridization. (B) Hybridization of the blots from panel A with probes specific for either the 5′ end (p25S5′) or 3′ end (p25S3′) of 25S rRNA.

We examined the distribution of rRNAs by Northern blot analysis of gradient fractions (Fig. 6). Fractions containing the extra peak in the mutant, close to the 40S peak, give the expected signal with an 18S rRNA probe for both strains. A probe specific for 25S rRNA detects a species in the novel peak that is smaller than 25S rRNA and does not appear in the wild type (Fig. 6). A probe specific for 5.8S rRNA shows that this species is absent from this part of the gradient in both the mutant and wild type (Fig. 6). Longer centrifugation allows better separation of this extra peak (about 38S) from the 40S subunit peak and reduces contamination of free 60S subunits (Fig. 7A). Northern blot analysis confirms again in these fractions the presence of an RNA of about 20S, whose origin is the 25S rRNA. This 20S RNA might be a product of degradation of the 25S rRNA that is poorly protected in an incomplete 60S subunit. The ratio of 18S rRNA in the ski6 mutant to 18S rRNA in the wild type is 1.04, while the ratio of full-length 25S rRNA in the ski6 mutant to 25S rRNA in the wild type is 1.05. Thus, the ratios of free ribosomal subunits are similar.

Probing the rRNA in the 38S peak with probes specific for the 5′ end or the 3′ end of 25S rRNA shows that the 25S-related species lacks the normal 5′ end but has sequences close to the 3′ end (Fig. 7B). The 25S-related sequence in the 38S peak can be distinguished both by size and by hybridization specificity from breakdown products of 25S rRNA found in the 60S peak of both mutant and wild-type strains (Fig. 7B). The latter hybridizes with both 5′ and 3′ probes, suggesting that they are a mixture of randomly broken molecules, while the former hybridizes with the 3′ probe but not with the 5′ probe.

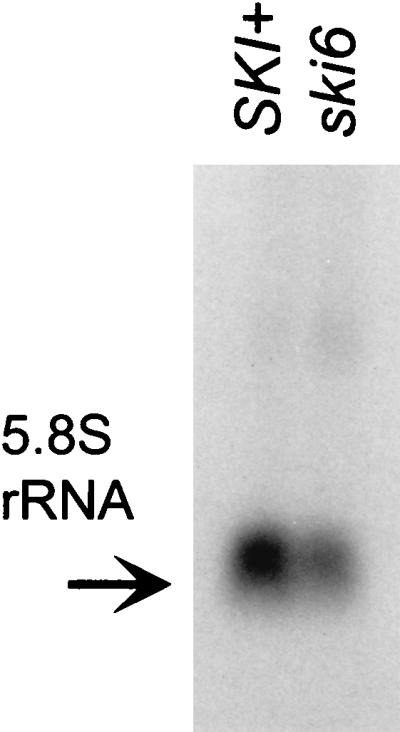

Comparison of total 5.8S rRNA in isogenic mutant and wild-type strains shows a 1.9-fold decrease in the ski6-2 mutant cells, with 18S rRNA as the control (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

A ski6-2 strain shows a deficiency in 5.8S rRNA accumulation. Northern blot analysis was done with 30 μg of total RNA extracted from cells grown at 30°C. The same blots were hybridized with 18S rRNA as a control (data not shown). Blots of each were quantitated by scanning.

ski6-2 suppresses the effect of 60S subunit deficiency on L-A mRNA translation.

The SKI genes were discovered based on their derepression of virus expression. Mutations in genes needed for 60S ribosome biogenesis, including 60S subunit protein genes, show reduced copy number of L-A dsRNA and loss of the killer toxin-encoding satellite M1 dsRNA (41). The mak7-1 mutation is deficient in ribosomal protein L4, has decreased free 60S ribosomal subunits, and shows halfmers, due to polysomes with a 40S subunit which is awaiting 60S joining (41). These mutants lose M1 dsRNA, but we find that ski6-2 mak7-1 double mutants propagate M1 normally. The mak7-1 ski6-2 strain 4566-2C (=MATa trp1 leu2 ura3 ski6-2 mak7-1 his− ade3) was transformed with either pSKI6 or pYRC50 (41) or both to make isogenic strains defective in one or both genes. Polysome profiles were obtained as described in Materials and Methods, and the ability of the double mutant to propagate M1 was examined. The mak7-1 strain lost M1, but the isogenic wild type and the ski6-2 mak7-1 double mutant propagate M1 normally. This indicates that translation of the L-A mRNA [which lacks poly(A)] is improved as a result of the ski6-2 mutation. Moreover, the halfmer peak is absent in polysome gradients of the double mutants (Fig. 9), suggesting an alteration in the 60S joining reaction.

FIG. 9.

ski6-2 suppresses mak7-1 without relieving the 60S ribosomal subunit deficiency of mak7-1 strains. The mak7-1 ski6-2 strain 4566-2C (=MATa trp1 leu2 ura3 ski6-2 mak7-1 his− ade3) was transformed with either pSKI6 or pYRC50 (41) or both to make isogenic strains defective in one or both genes. Polysome profiles were obtained as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Ski6p is involved in 60S ribosome assembly.

Mutations in ribosomal protein genes result in decreased rates and extents of ribosome assembly as expected from their being essential components of the final structure (36, 63). Other components that are not part of the finished product but are necessary for its construction have also been identified (29, 47, 55, 57).

Ski6p is clearly not one of the ribosomal proteins, but we show that a ski6 mutant, even at the permissive temperature, accumulates a novel particle that contains a fragment of 25S rRNA lacking the 5′ end of the normal 25S rRNA. This is likely to be either a misassembled 60S subunit or a misassembled and then partially degraded 60S particle. This particle lacks 5.8S rRNA, and the cells show some deficiency of total 5.8S rRNA in comparison to an isogenic wild-type strain. There is no change in the relative levels of free 60S or 40S particles. It is unlikely that the 38S particle carries out any of the reactions of protein synthesis since it lacks both 5.8S rRNA and part of 25S rRNA.

However, the ski6 mutants plainly do have alterations of the translation apparatus itself. They are hypersensitive to hygromycin B, a phenotype typical of mutants in components of the translation apparatus. ski2 mutants show the same phenotype. This suggests that, in addition to the 38S defective 60S ribosomal subunits that accumulate in ski6 strains, the normal-sized 60S subunits are probably also functionally abnormal, perhaps by containing improperly processed rRNA.

Mitchell et al. have found that Ski6p is in a complex with other RNA-processing exoribonucleases (34), suggesting that it has a similar function. One of these exoribonucleases, Rrp4p, is known to be involved in 5.8S rRNA processing (35), and ski6 (renamed rrp41) mutants are likewise defective in 5.8S rRNA processing (34).

Does Ski6p derepress translation of non-poly(A) mRNAs via alterations of full-sized 60S subunits?

Ski6p, like Ski2p, Ski3p, and Ski8p, is necessary for blocking the translation of non-poly(A) mRNAs, such as the viral mRNAs whose overexpression formed the basis of the original mutant isolations. The evidence points to translation, rather than mRNA turnover, as the basis of the derepressed expression of non-poly(A) mRNAs. The kinetics of luciferase accumulation and direct measurements of mRNA turnover show the pattern expected for a translation effect.

The ski2, ski3, ski6, and ski8 mutants translate non-poly(A) mRNAs nearly as well as they do poly(A)+ mRNAs (31; also this work), showing that the translation apparatus is inherently able to use non-poly(A) mRNAs. Indeed, it had already been shown that poly(A)-deficient mRNAs are found on polysomes in strains lacking the SKI1/XRN1 exoribonuclease that degrades uncapped mRNAs (21) and in a poly(A) polymerase temperature-sensitive mutant shifted to the nonpermissive temperature (43).

Elucidating the means by which Ski proteins block translation of non-poly(A) mRNA requires consideration of the role in translation of the 3′ poly(A) structure of eucaryotic mRNA, an area which remains controversial (reviewed in references 22 and 48). Translation of electroporated mRNAs is stimulated by the 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) structures by 12- and 200-fold, respectively (19, 56). The 3′ poly(A) structure is known to affect mRNA turnover (for an example, see reference 8), but the kinetics of reporter synthesis show that there is a substantial effect on synthesis, independent of mRNA stability differences (19).

One role suggested for poly(A) is to promote the joining of the 60S subunit to the 40S subunit waiting with associated initiation factors at the initiator AUG (38; for reviews, see references 22 and 39). This was proposed to occur by an interaction between the poly(A) and the 60S subunit, forming a circular mRNA, at least at the time of initiation. Our results support this model (31, 41; also this work). A deficiency of free 60S ribosomal subunits (in strains with mutations in any of 20 mak genes) results in poor translation of the viral mRNAs because they lack poly(A) and so compete poorly with the poly(A)+ cellular mRNAs for limiting free 60S subunits (41). Indeed, limitation of 40S or 60S subunits in a strain temperature sensitive for poly(A) polymerase showed greater discrimination against non-poly(A) mRNA when 60S subunits were limiting (42). Mutations in the ski2, ski3, ski6, and ski8 genes improve viral mRNA translation [since they improve the translation of all non-poly(A) mRNAs] and suppress the effect of 60S subunit deficiency (without restoring the levels of 60S subunits) (31; also this work). Another model for the role of poly(A) in translation involves the association of the poly(A) binding protein with eIF-4G (48). However, this model does not suggest an explanation of our data.

We suggested that the Ski2, Ski3, and Ski8 proteins prepare 60S subunits so that they have the requirement for interaction with the 3′ poly(A) structure before they will join with the 40S subunit waiting at the AUG (31, 41, 58). We had no direct evidence that these proteins have these effects by altering 60S biogenesis besides the fact that Ski3p is nuclear (44) and that Ski2p is highly homologous to the mammalian Ski2p (28, 61) which has been localized to the nucleolus (28). In the case of ski6, we have shown directly that 60S subunits are altered.

Conclusions.

We find that SKI6 encodes a homolog of bacterial tRNA-processing enzymes and is necessary for a system that specifically blocks translation of non-poly(A) mRNA. We see a novel species in ski6 mutants that includes a fragment of 25S rRNA but lacks 5.8S rRNA, suggesting that in these strains 60S subunits are not properly formed. Hygromycin B hypersensitivity and suppression of halfmers in a mutant deficient in the ribosomal protein L4 also support the idea that a subtle modification exists in the functional ribosomes and suggests that this modification bypasses the requirement of a 3′ poly(A) for translation.

The results presented here and previously (31) suggest that the default for translation is efficient translation of mRNA independent of poly(A) and that, in a wild-type cell, the specificity for poly(A) mRNA is accomplished (by the Ski2, Ski3, Ski6, and Ski8 proteins) by repressing translation of poly(A)− mRNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball S G, Tirtiaux C, Wickner R B. Genetic control of L-A and L-BC dsRNA copy number in killer systems of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1984;107:199–217. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc A, Goyer C, Sonenberg N. The coat protein of the yeast double-stranded RNA virus L-A attaches covalently to the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3390–3398. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanc A, Ribas J C, Wickner R B, Sonenberg N. His-154 is involved in the linkage of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae L-A double-stranded RNA virus Gag protein to the cap structure of mRNAs and is essential for M1 satellite virus expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2664–2674. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruenn J, Keitz B. The 5′ ends of yeast killer factor RNAs are pppGp. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3:2427–2436. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.10.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll K, Wickner R B. Translation and M1 double-stranded RNA propagation: MAK18 = RPL41B and cycloheximide curing. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2887–2891. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2887-2891.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouzet M, Izgu F, Grant C M, Tuite M F. The allosuppressor gene SAL4 encodes a protein important for maintaining translational fidelity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1988;14:537–543. doi: 10.1007/BF00434078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dangel A W, Shen L, Mendoza A R, Wu L-C, Yu C Y. Human helicase gene SKI2W in the HLA class III region exhibits striking structural similarities to the yeast antiviral gene SKI2 and to the human gene KIAA0052: emergence of a new gene family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2120–2126. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker C J, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–1643. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher M P. Ribonucleases, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase and the 3′ processing of tRNA. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:209–240. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60628-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deutscher M P, Marshall G T, Cudny H. RNase PH: an Escherichia coli phosphate-dependent nuclease distinct from polynucleotide phosphorylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4710–4714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinman J D. Ribosomal frameshifting in yeast viruses. Yeast. 1995;11:1115–1127. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinman J D, Icho T, Wickner R B. A −1 ribosomal frameshift in a double-stranded RNA virus of yeast forms a gag-pol fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:174–178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinman J D, Ruiz-Echevarria M J, Czaplinski K, Peltz S W. Peptidyl-transferase inhibitors have antiviral properties by altering programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting efficiencies: development of model systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6606–6611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinman J D, Wickner R B. Ribosomal frameshifting efficiency and gag/gag-pol ratio are critical for yeast M1 double-stranded RNA virus propagation. J Virol. 1992;66:3669–3676. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3669-3676.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrenfeld E. Initiation of translation by picornavirus RNAs. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 549–573. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson J R, Johnston M. Direct cloning of yeast genes from an ordered set of lambda clones in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by recombination in vivo. Genetics. 1993;134:151–157. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everett J G, Gallie D R. RNA delivery in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using electroporation. Yeast. 1992;8:1007–1014. doi: 10.1002/yea.320081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaber R F, Culbertson M R. Frameshift suppression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. IV. New suppressors among spontaneous co-revertants of the group II his4-206 and leu2-3 frameshift mutations. Genetics. 1982;101:345–367. doi: 10.1093/genetics/101.3-4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallie D R. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2108–2116. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerreiro P, Silva A M E, Barreiros T, Arroyo J, Garcia-Gonzalez M, Garcia-Saez M I, Rodrigues-Pousada C, Nombela C. The complete sequence of a 9000 bp fragment of the right arm of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VII contains four previously unknown open reading frames. Yeast. 1995;11:1087–1091. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu C L, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5′→3′ exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5′ cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–4835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson A. Poly(A) metabolism and translation: the closed-loop model. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 451–480. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson A W, Kolodner R D. Synthetic lethality of sep1 (xrn1) ski2 and sep1 (xrn1) ski3 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is independent of killer virus and suggests a general role for these genes in translation control. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2719–2727. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones J S, Prakash L. Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae selectable markers in pUC18 polylinkers. Yeast. 1990;6:363–366. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadowaki T, Schneiter R, Hitomi M, Tartakoff A M. Mutations in nucleolar proteins lead to nucleolar accumulation of polyA+ RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1103–1110. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.9.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly K O, Deutscher M P. Characterization of Escherichia coli RNase PH. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17153–17158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly K O, Reuven N B, Li Z, Deutscher M P. RNase PH is essential for tRNA processing and viability in RNase-deficient Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16015–16018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S-G, Lee I, Kang C, Song K. Identification and characterization of a human cDNA homologous to yeast SKI2. Genomics. 1994;25:660–666. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80008-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee W C, Zabetakis D, Melese T. NSR1 is required for pre-rRNA processing and for the proper maintenance of steady-state levels of ribosomal subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3865–3871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu R, Liebman S W. A translational fidelity mutation in the universally conserved sarcin/ricin domain of 25S yeast ribosomal RNA. RNA. 1996;2:254–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masison D C, Blanc A, Ribas J C, Carroll K, Sonenberg N, Wickner R B. Decoying the cap− mRNA degradation system by a double-stranded RNA virus and poly(A)− mRNA surveillance by a yeast antiviral system. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2763–2771. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathews M B. Interactions between viruses and the cellular machinery for protein synthesis. In: Hershey J B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 505–548. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto Y, Sarkar G, Sommer S S, Wickner R B. A yeast antiviral protein, SKI8, shares a repeated amino acid sequence pattern with beta-subunits of G proteins and several other proteins. Yeast. 1993;8:43–51. doi: 10.1002/yea.320090106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Tollervey D. The exosome, a conserved eukaryotic RNA processing complex containing multiple 3′→5′ exoribonucleases. Cell. 1997;91:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Tollervey D. The 3′ end of yeast 5.8S rRNA is generated by an exonuclease processing mechanism. Genes Dev. 1996;10:502–513. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moritz M, Paulovich A G, Tsay Y F, Woolford J L. Depletion of yeast ribosomal proteins L16 or RP59 disrupts ribosome assembly. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2261–2274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muhlrad D, Decker C J, Parker R. Turnover mechanisms of the stable yeast PGK1 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2145–2156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munroe D, Jacobson A. mRNA poly(A) tail, a 3′ enhancer of translation initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3441–3455. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munroe D, Jacobson A. Tales of poly(A): a review. Gene. 1990;91:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson R J, Ziegilhoffer T, Nicolet C, Werner-Washburne M, Craig E A. The translation machinery and 70 kDal heat shock protein cooperate in protein synthesis. Cell. 1992;71:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90269-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtake Y, Wickner R B. Yeast virus propagation depends critically on free 60S ribosomal subunit concentration. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2772–2781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proweller A, Butler J S. Ribosome concentration contributes to discrimination against poly(A)− mRNA during translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6004–6010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proweller A, Butler J S. Efficient translation of poly(A)-deficient mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2629–2640. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhee S K, Icho T, Wickner R B. Structure and nuclear localization signal of the SKI3 antiviral protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1989;5:149–158. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ridley S P, Sommer S S, Wickner R B. Superkiller mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae suppress exclusion of M2 double-stranded RNA by L-A-HN and confer cold sensitivity in the presence of M and L-A-HN. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:761–770. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riles L, Dutchik J E, Baktha A, McCauley B K, Thayer E C, Leckie M P, Braden V V, Depke J E, Olson M V. Physical maps of the six smallest chromosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae at a resolution of 2.6 kilobase pairs. Genetics. 1993;134:81–150. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ripmaster T L, Vaughn G P, Woolford J L. DRS1 to DRS7, novel genes required for ribosome assembly and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7901–7912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandbaken M G, Lupisella J A, DiDimenico B, Chakraburtty K. Protein synthesis in yeast: structural and functional analysis of the gene encoding elongation factor 3. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15838–15844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevens A. Purification and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae exoribonuclease which yields 5′ mononucleotides by a 5′→3′ mode of hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3080–3085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevens A, Maupin M K. A 5′→3′ exoribonuclease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: size and novel substrate specificity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;252:339–347. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiele D J, Hannig E M, Leibowitz M J. Genome structure and expression of a defective interfering mutant of the killer virus of yeast. Virology. 1984;137:20–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toh-e A, Guerry P, Wickner R B. Chromosomal superkiller mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1978;136:1002–1007. doi: 10.1128/jb.136.3.1002-1007.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toh-e A, Wickner R B. “Superkiller” mutations suppress chromosomal mutations affecting double-stranded RNA killer plasmid replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:527–530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tollervey D, Lehtonen H, Jansen R, Kern H, Hurt E C. Temperature-sensitive mutations demonstrate roles for yeast fibrillarin in pre-rRNA processing, pre-rRNA methylation and ribosome assembly. Cell. 1993;72:443–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90120-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasilescu S, Ptushkina M, Linz B, Muller P P, McCarthy J E. Mutants of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF-4E with altered mRNA cap binding specificity reprogram mRNA selection by ribosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7030–7037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venema J, Tollervey D. Processing of pre-ribosomal RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1995;11:1629–1650. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickner R B. Double-stranded RNA viruses of yeast. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:250–265. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.250-265.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wickner R B. Killer systems in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: three distinct modes of exclusion of M2 double-stranded RNA by three species of double-stranded RNA, M1, L-A-E, and L-A-HN. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:654–661. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.4.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickner R B. Plasmids controlling exclusion of the K2 killer double-stranded RNA plasmid of yeast. Cell. 1980;21:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Widner W R, Wickner R B. Evidence that the SKI antiviral system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae acts by blocking expression of viral mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4331–4341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilson R, Ainscough R, Anderson K, Baynes C, Berks M, Bonfield J, Burton J, Connell M, Copsey T, Cooper J, Coulson A, Craxton M, Dear S, et al. 2.2 Mb of contiguous nucleotide sequence from chromosome III of C. elegans. Nature. 1994;368:32–38. doi: 10.1038/368032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woolford J L, Warner J R. The ribosome and its synthesis. In: Broach J R, Pringle J R, Jones E W, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: genome dynamics, protein synthesis and energetics. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1991. pp. 587–626. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshioka, S., K. Kato, and H. Okayama. Unpublished data.