Abstract

Emerging adulthood shapes personal, professional, and overall well-being through identity exploration. This study addresses a gap in the minority identity literature by investigating how urban AI/AN emerging adults think about their identity and discussing challenges and protective factors associated with exploring their identity holistically. This mixed-methods study created a sampling framework based on discrimination experiences, cultural identity, social network support, mental health, and problematic substance use. We recruited 20 urban AI/AN emerging adults for interviews. We sought to gain deeper insights into their experiences and discussions surrounding identity formation and exploration. We provide descriptives for demographic characteristics and conducted a thematic analysis of the qualitative data from the interviews. Four themes emerged: a) being an urban AI/AN emerging adult means recognizing that one’s identity is multifaceted; b) a multifaceted identity comes with tension of living in multiple worlds; c) the trajectory of one’s identity grows over time to a deeper desire to connect with Native American culture; and d) understanding one’s Native American background affects one’s professional trajectory. Findings underscore the importance of developing programs to support well-being and identity development through cultural connection for urban AI/AN emerging adults.

Keywords: American Indian/Alaska Native, Emerging adults, Identity, Urban

Introduction

Understanding identity formation holistically is an important process that involves comprehensively examining the complex interplay of cultural, social, psychological, historical, and biological factors, providing comprehensive insight into an individual’s sense of self (Branje et al., 2021; Pfeifer & Berkman, 2018; Zhang & Qin, 2023). Failing to consider these diverse elements can result in an incomplete understanding of identity, hindering efforts to support personal development and navigate the complexities of human interaction. Identity formation is a pivotal process in an individual’s development, ideally enabling the cultivation of a coherent and authentic sense of self. This sense of self can help empower individuals to make informed decisions, set meaningful goals, and navigate life’s challenges with confidence and purpose (Branje et al., 2021). Emerging adulthood (ages 18-25 years) is considered a period of identity exploration and formation, involving the exploration of one’s background, values, interests, beliefs and aspirations, culminating in a unified self-concept that guides their interactions and experiences in the world (Forrest-Bank & Cuellar, 2018; Hardeman et al., 2016; Loyd et al., 2022; Stein et al., 2014). This exploration holds particular significance for individuals from multiracial or multicultural backgrounds as they may face unique challenges in developing a coherent sense of identity or in negotiating multiple identities (Gaither, 2015; Pauker et al., 2018).

Identity Formation and Social Identity

Social identity is a key aspect of self-concept shaped by belonging to social groups based on race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and occupation (Stets & Burke, 2000; Tajfel et al., 1979). This framework enables categorization and understanding of one’s place in society, which can foster self-worth (Stets & Burke, 2000). Racial and ethnic identity are specific forms of social identity that focus on affiliation with specific groups of people, with racial identity based on physical traits, and ethnic identity tied to shared cultural elements like language, religion, tradition, customs and a shared history or ancestry (Burlew & Smith, 1991; Chandra, 2006; Syed & Azmitia, 2008; Vargas & Kingsbury, 2016).

Understanding one’s overall identity (i.e., racial and ethnic identity, gender identity, religious/spiritual identity) during emerging adulthood is crucial for self-awareness, cultural navigation, and value alignment (Branje, 2022; Grilo et al., 2023; Woo et al., 2019). This foundation fosters a sense of belonging and purpose in a diverse world (Grilo et al., 2023). Additionally, cultivating and enhancing overall identity may help to protect against discrimination, help foster personal growth, and build resilience (Grilo et al., 2023; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) Identity

American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) identity encompasses social, racial and ethnic identity components, reflecting ancestry, heritage, and cultural affiliation to the North American Indigenous people. The diverse AI/AN population comprises over 580 recognized tribes, each with unique history and practices. Geographic, climatic, and ecological settings influence traditional lifestyles and economic activities. Moreover, historical events, including colonization, forced relocations, and policies like boarding schools have deeply shaped the unique identity of each community. As a result, this population is comprised of diverse and mixed ethnic and racial identities (Evans-Lomayesva & Lee, 2022). Social identity among AI/AN encompasses a wide array of factors, and is diverse, consisting of differences relating to cultural heritage, tribal affiliations, language, socioeconomic status, and historical experiences.

Historical events like the Federal Indian Boarding School Movement and the Dawes Act continue to impact affect AI/AN people leading to economic, physical, and social challenges (Adams, 2020; Carlson, 1978; Haag, 2007). Many AI/AN individuals sought had to seek opportunities in urban areas due to forced relocation, but they faced discrimination, geographical fragmentation, reduced community ties, loneliness, economic disadvantages, and struggles with substance use and suicidal ideations mental health (Espey et al., 2014; Herne et al., 2014; Kunitz et al., 2014; Urban Indian Health Commission, 2007; Yuan et al., 2014).

In both urban and non-urban settings, AI/AN individual’s face distinct cultural-historical challenges and protective factors. In urban environments, AI/AN people often face the challenge of maintaining their cultural identity (a sense of belonging, affiliation, and connection to the AI/AN culture including customs, traditions and values), in a diverse and fast-paced environment as they navigate exposure to mainstream influences, as well as negotiating multiple racial-ethnic and cultural identities (Brown et al., 2016; Markstrom, 2011; Marsella, 2012; Schwartz et al., 2008). Conversely, in non-urban areas, AI/AN emerging adults often have more direct access to traditional cultures, strengthening their connection to their heritage but may also have less access to different educational and employment opportunities and technology (Brown et al., 2023; Parkhurst et al., 2015; US Department of the Interior Indian Affairs, 2023). The cultural-historical context surrounding AI/AN emerging adults differs from those of other racial and ethnic groups due to unique historical burdens and the relationship with the US government through treaties and tribal sovereignty. These factors bring both challenges (e.g., discrimination, cultural disconnection, substance use, mental health) and strengths (e.g. cultural resilience, community support, spirituality) for AI/AN emerging adults that differ from those experienced by other racial and ethnic minority groups (Denham, 2008; Oré et al., 2016). In light of all of these factors, the identity development of AI/AN emerging adults today requires them to grapple with the complexities of historical traumas and ongoing challenges, while striving to cultivate a resilient and meaningful sense of self embracing a rich tapestry of cultures and traditions.

Identity Formation and Health

Numerous studies (Ahmmad & Adkins, 2021; Karaś et al., 2015; Lind et al., 2022; Matud et al., 2020; Schwartz et al., 2011; Spencer et al., 2021; Tanner et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2015) highlight the pivotal role of identity formation in emerging adulthood for health outcomes. For example racial and ethnic identity formation is often associated with experiences of discrimination and subsequent health disparities (Fisher et al., 2017; Reyes et al., 2022; Zapolski et al., 2017) whereby marginalized individuals may engage in risky practices such as risky sex and problematic substance use (Amaro et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2022). To address disparities among marginalized individuals, life course approaches need to focus on critical developmental stages such as emerging adulthood (Jones et al., 2019; Lee & O’Neal, 2022). Research has consistently shown, for example, how one’s identity can positively affect mental and physical health and overall well-being (Ai et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2017; Gaither et al., 2015; Reyes et al., 2022; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2020; Zapolski et al., 2019; Zapolski et al., 2017). This protective effect has also been found among AI/AN emerging adults and adolescents (Brown et al., 2021; Smokowski et al., 2014). Thus, it is critical to understand how individuals express their identities and how this expression can shape their experiences and health outcomes.

Previous Studies on Emerging Adults Identity Formation

To date, there is ample research examining identity formation among Black, Hispanic, and Asian emerging adults; however, there is a notable gap in understanding identity formation among urban AI/AN emerging adults (Brown et al., 2023; Dickerson et al., 2022), particularly addressing the intricacies of tribal affiliation, origin stories, and AI/AN cultural practices. Previous studies with Black, Hispanic and Asian individuals suggest that those whose identity formation is primarily influenced by negative stressors without positive factors tend to report lower self-esteem, increased substance use, and poorer mental health outcomes (Ahmmad & Adkins, 2021; Forster et al., 2017; Meca et al., 2022; Myrie et al., 2022; Schwartz et al., 2011; Spencer et al., 2021). Conversely, individuals who engage in in-depth identity exploration and demonstrate resilience in the face of challenges tend to exhibit higher levels of well-being and maintain a positive and forward-looking outlook on the future (Karaś et al., 2015; Lind et al., 2022). Most importantly, these studies have revealed how racially and ethnically diverse emerging adults construct their identity being mindful of structural barriers, immigration experience, and discrimination, with the help of cultural support and parental guidance (Antman, 2022; Jones & Rogers, 2022, 2023; Myrie et al., 2022; Schwartz et al., 2017; Unni et al., 2022).

Scholars emphasize that urban AI/AN identity formation is a complex process extending beyond psychosocial stressors and ethnic identity (Markstrom, 2011). AI/AN identity formation theory highlights the multifaceted nature of identity as it encompasses ethnic-Indigenous identity, cultural connection, ancestral ties, land, and participation in cultural practices and spirituality (Kulis et al., 2013; Markstrom, 2011). Markstrom’s model of Indigenous identity emphasizes that identity formation of AI/AN individuals is shaped by the distinctiveness of their culture, history, experiences with American society, and their growing engagement with the global community (Markstrom, 2011).

Current Study

Understanding how urban AI/AN emerging adults navigate and express their identity holistically (including social, cultural, psychological, historical and biological aspects) is crucial for comprehending both their health risk (Ahmmad & Adkins, 2021; Lind et al., 2022) and increasing health equity among this population(Brown et al., 2016). This study addresses this gap by exploring how AI/AN emerging adults discuss their identity holistically and negotiate identity in different settings, including educational and work settings. Based on the identity literature, we hypothesized that AI/AN emerging adults with fewer experiences of discrimination, stronger cultural identity, and connection, as well as better mental health and lower substance use would likely undergo a smoother process of identity formation, compared to their peers facing higher levels of discrimination, weaker cultural identity and connection, poorer mental health, and greater substance use. This study addresses an important gap in minority identity research by specifically focusing on urban AI/AN emerging adults, a population that has been understudied. Our goal is to provide unique insight into the complexities of identity negotiation in urban environments among this population contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of minority identity development, which can help increase health equity by fostering positive identity development, potentially bolstering resilience within this historically marginalized population.

This study adds to the limited current literature on the association between AI/AN identity and discrimination (Galliher et al., 2011; Jaramillo et al., 2016; Kenyon & Carter, 2011) using a semi-structured ethnographic interviewing approach that allows AI/AN emerging adults to describe experiences of discrimination and their sense of self and identity in their own terms. As such, it is not closely tied to any specific theory of social, racial-ethnic, or cultural identity. Instead, our approach allowed discussions of identity to flow naturally from discussions of specific challenges to identity in the form of experiences of discrimination. This helps shed light on how identity may be experienced holistically in the lives of AI/AN emerging adults across different points in the life course and social settings.

Methods

Sampling and Recruitment

This study is part of a Health Equity Supplement funded by NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) and is part of a larger longitudinal clinical trial - Traditions and Connections for Urban Native Americans (TACUNA) (D’Amico, Dickerson, Rodriguez, et al., 2021). TACUNA is a culturally based substance use prevention intervention for AI/AN emerging adults (aged 18-25) who do not live on a reservation or tribal lands. Similar to our previous work (Brown et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2023; D’Amico, Dickerson, Brown, et al., 2021), we collaborated with our community partner, Sacred Path Indigenous Wellness Center, and our Elder Advisory Board (EAB) throughout the study, including garnering their feedback on interview protocols, tailoring recruitment approaches, interpreting results, and gauging community reactions.

Eligibility criteria for the TACUNA trial include: 1) ages 18 to 25; 2) living in an urban area in any state in the United States that is not on a rancheria or a reservation); 3) self-identification as AI/AN; 4) no opioid use disorder; and 5) English speaking. The study utilized Facebook and Instagram for recruitment. On both platforms, we set up a dedicated page for individuals to receive updates. Tailored advertisements on both platforms directed our target audience to the study page and screener. Participants completed an online screener, and eligible participants were contacted by staff from our Survey Research Group and consented to be part of the study. Participants completed a baseline survey and were randomized to receive either one virtual workshop or three virtual workshops and a Wellness Circle (D’Amico et al., 2021). Participants were also asked if they wanted to participate in qualitative interviews during baseline data collection. At the time of this paper, the baseline assessment had 125 participants. The focus of the health equity supplement was to recruit 20 participants from this larger sample to complete qualitative interviews. Procedures were approved by the author’s institution’s IRB and the project’s Urban Intertribal Native American Review Board. This study has been preregistered with Clinical Trials, registration NCT04617938, and has published the study protocol (D’Amico et al., 2021).

Sampling Profile Development

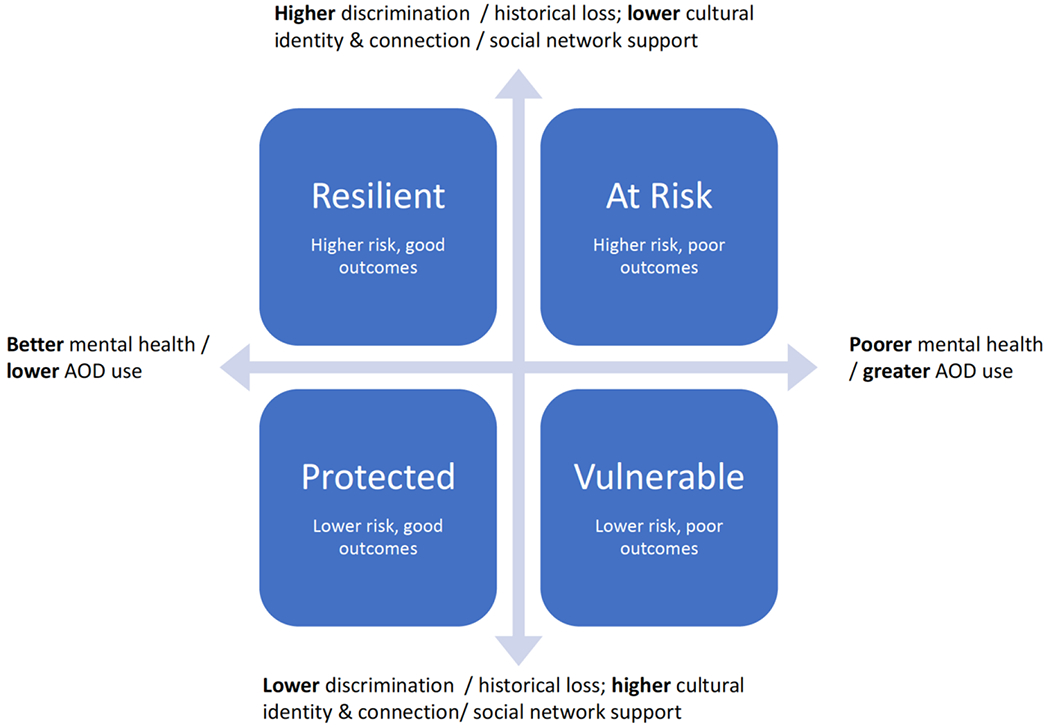

We recruited a subsample of 20 individuals from the randomized controlled trial to participate in additional qualitative interviews to understand AI/AN conceptualization of their identity and their experiences with discrimination. We recruited individuals experiencing 4 different types of circumstances (see figure 1) based on their answers to the following measures (see measures section): discrimination, cultural identity, mental health (PHQ-9 and GAD-7), and problematic substance use.

Figure 1.

Sampling Strategy

We constructed four profiles using data from measures of mental health (PHQ, GAD), problematic substance use (AUDIT-C, CUDIT-R Short Form), discrimination, and cultural identity. Mental health was divided into two groups: better mental health (negative screen on both PHQ and GAD) and poorer mental health (positive screen on at least one mental health measure). Problematic alcohol and other drug use (AOD) use was divided into two groups: low problematic AOD use (negative screen on both CUDIT and AUDIT-C) and high problematic AOD use (positive screen on at least one substance use measure). Discrimination was split into two groups: low reported discrimination (total score ≤5) and high reported discrimination (total score ≥ 7). Respondents were then categorized into four equal sized groups (5 participants per group) based on mental health, problematic AOD use, and discrimination. Given limited variability in MEIM scores, once binned, we examined MEIM scores within each bin to focus on lower versus higher cultural identity. The resulting 4 profiles were characterized as 1) Protected (better mental health, lower problematic AOD use, lower discrimination, higher cultural identity); 2) Resilient (better mental health, lower problematic AOD use, higher discrimination, lower cultural identity); 3) At-Risk (poorer mental health, higher problematic AOD use, higher discrimination, lower cultural identity); and 4) Vulnerable (poorer mental health, higher problematic AOD use, lower discrimination, higher cultural identity.

We determined this sampling strategy together with our Elder Advisory Board (authors CLJ, VAS and KS are members of the EAB). After extensive discussions with the EAB, we determined the best way to accurately represent the experiences of AI/AN individuals in these different profiles was via a continuum depicting the fluid nature of their circumstances (Figure 2). This continuum allows individuals to progress toward wellness depending on their evolving situation, providing a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of their lived realities. This framework emphasizes that individuals are not confined to a single quadrant, but have the capacity to transition across the spectrum. By incorporating this dynamic and responsive framework, we are better able to capture the full range of protective experiences and challenges faced by urban AI/AN emerging adults.

Figure 2.

Elder Advisory Board Recommended Illustration of the Profiles

Note: AOD = alcohol and other drug use

Measures

We used Flesch-Kincaid standards to ensure survey questions were at a 6th to 8th grade reading level. Our measures came from our work with the IRINAH (Intervention Research to Improve Native American Health) group (Crump et al., 2020) and the RAND Adolescent/Young Adult Panel Study (Ellickson et al., 2001; Tucker et al., 2003), which was carefully developed based on established items and scales from Monitoring the Future (Johnston et al., 2011) and DSM-V criteria.

Screening.

We screened participants to ensure that they did not need treatment for opioid use disorder using the RODS (Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen) (Wickersham et al., 2015).

Background measures.

Participants were asked to identify their age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity. Other demographic items included gender identification, sexual orientation, and migration history.

Mental health.

Participants completed questions about their mental health status using Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) 7-item questionnaire (Mossman et al., 2017) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001). Total sum scores were created for each scale and then dichotomized based on clinical thresholds for positive screen. Specifically, scores greater than 10 were coded as 1 to reflect a positive screen, and 0 for a negative screen.

Substance use.

Participants reported problematic substance usage with the 3-item AUDIT-C (Bush et al., 1998) for alcohol use disorder and the 3-item CUDIT – Short Form (Bush et al., 1998) for Cannabis use disorder. The AUDIT-C is scored on a scale of 0-12 (scores of 0 reflect no alcohol use). In men, a score of 4 or more is considered positive; in women, a score of 3 or more is considered positive. Generally, the higher the AUDIT-C score, the more likely it is that the patient’s drinking is affecting his/her health and safety. The three item CUDIT is scored on a scale of 0-12 (scores of 0 reflect no cannabis use). A cut score of 2 is used to reflect a positive screen for cannabis use disorder.

Risk factors.

Participants reported their experiences with discrimination with an 11-item scale measuring experiences of discrimination during the previous year across a spectrum of services and situational contexts (e.g., been called a racist name like Squaw, Red Skin or savage; experienced unfair treatment by the police or other law enforcement (e.g., FBI, INS) because you are Native). The response options were “Yes”, “I’m not sure but I think so”, and “No” (Walters, 2005). For this analysis we created a count of the types of discrimination experiences to which participants responded “yes” or “I’m not sure but I think so.”

Protective factors.

Ethnic identity was assessed with the 12-item Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) (a = .94), which shows exploration, commitment, and affiliation to one’s ethnic identity and focuses on pride and belonging (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Ponterotto et al., 2003). Our previous work (Brown et al., 2016) indicated that many urban (those who do not live on reservations or tribal lands) AI/AN emerging adults were of mixed ethnicity, so we modified MEIM items to focus on AI/AN heritage (e.g., “I have a clear sense of my AI/AN identity and what it means to me”) (D’Amico, Dickerson, Brown, et al., 2021). The 12 items are averaged for a final scale score.

Quantitative Data Analysis

We used SAS version 9.4 to generate means, standard deviations, and frequencies. We conducted t-tests were to compare mean scores of the discrimination and MEIM scales.

Qualitative Data Collection Procedures

We conducted one-hour interviews on Zoom with participants in the four profile categories following a semi-structured interview protocol. We asked about their diverse experiences of discrimination, cultural identity and connection, and social support. The protocol was structured using a matrix approach. Thus, we started the conversation with a grand tour question to elicit participants’ stories in their own words, followed by a grid of questions that were utilized depending on the comprehensiveness of the first response, how expansive their story was, and the direction of their story. For example, the grid contained questions by timeline of the discrimination event, behavior participant response to the discrimination, and thoughts and feelings relative to the event. Questions asked included “what does your Native American, heritage, family roots, and identity mean to you” and “what are some of your most important things in your life for you?” This approach offered us the freedom to then follow the respondents’ train of thought and probe accordingly. Table 1 contains the interview protocol. Participants received a $50 gift card for the interview.

Table 1.

Qualitative Interview Protocol

| Interview Questions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Warm up 1. Tell us a little about yourself. 2. What are some of your most important things in life for you? 3. What does your Native American heritage, family roots, and identity mean to you? | ||||

|

Grand Tour Question [Note: This question is meant to elicit the participants’ story in their own words. This question is followed below by a grid of follow-up questions that we may or may not have to ask, depending on how forthcoming a respondent is, how expansive the answer is, or on the direction of their story. This approach gives the interviewers the freedom to then follow the respondents’ train of thought, and probe accordingly.] Think about a time that you or someone you know experienced discrimination based on having a Native background. This can be major things or more minor ones, such as being ridiculed, or being made fun of. What happened? Tell me about it from start to finish. | ||||

| Life context immediately before discrimination event | Discrimination event | Immediate reaction to event | Consequences | |

| Actions & Behavior | Please help me understand what else was going on immediately before your experienced this event. Where were you and what were you doing? What else was going on nearby that might have led to the event taking place? PROBE IF THEY BRING UP RISKS LIKE MENTAL HEALTH, AOD USE: Tell me more about it. |

Tell me more about what happened. Who was involved? What aspects of your life did this event involve? What role, if any, did alcohol or drugs play in this – either for you or anyone else involved? |

What was your immediate reaction to this experience? What did you do? What did others around you do? |

What were the consequences of what you experienced, either short or long-term? |

| Thoughts & Feelings | Before this event, what were you thinking or feeling? Before this event, how did you feel about yourself? |

What were you thinking when this happened to you? How did you feel when this happened to you? What did you think those who discriminated against you were thinking? |

What were you thinking immediately afterwards? How did you feel immediately afterwards? |

How did this event affect how you think about yourself? How did this event affect your life goals, or how you think about your future? How has discrimination affected your mental health? |

| Native Background | Thinking about Native American losses, such as loss of land, loss of culture, loss of language…how have these losses affected your ancestors and your family? Before this event, were you engaging in Native American cultural practices or activities? |

How do you think these historical losses are connected to the event that you experienced? | Help me understand how your involvement in traditional practices or your Native American community help you cope with the stresses that you experience, such as discrimination and historical loss? | What have been some of the consequences of these losses for you? What about your family? Your community? |

| Social Network | Did you talk to anyone about discrimination against Native Americans before you experienced it? Tell me about it. How does alcohol and other drug use in your network affect you? Are you connected to folks who live on the res or in rural areas far outside the city? If yes, how do you keep in touch with them? What has it been like for you to be Native American within an urban area, away from your tribe’s or family’s home reservation/village/rancheria? |

Thinking about your experience, who else was involved? What were they doing? How were they involved? How common do you think such experiences are among your peers? |

In what ways did your community help you overcome the experience you have had? How did your friends/family from the reservation / village /rancheria react when you told them about your experience? How did this compare to reactions from your peers in your urban community? |

How do you think your social relationships might help you deal with discrimination in the future? |

|

Compare and contrast

[Note: these questions will vary depending on their answers. The objective is to try to elicit aspects of resilience to discrimination] |

Thinking about your specific experiences, how were these different from others? Was this a typical experience? PROBES: If they say this happens all the time, then: Tell me about the last time it happened. PROBES: If they say it’s unusual, then: Tell me about the usual experience. Was there an experience that you were able to deal with and/or overcome? If yes, what helped you respond? |

|||

Reflexivity and Positionality

Two authors (AP and RB) conducted the interviews. Some were conducted jointly, and others were led by only one of them. The interviewers are trained in qualitative methods in behavioral science and health services research and extensive prior experience interviewing and analyzing qualitative data from urban-dwelling AI/AN populations. Both these interviewers are non-indigenous scholars with research foci in AI/AN populations and significant experience living among AI/AN populations and conducting field research on Native American lands, as well as visiting AI/AN reservations across the U.S. The research team has a long history of working with urban AI/AN communities to provide support and address health disparities. One of the principal investigators and author in this paper (DLD), along with three other contributors (CLJ, VAS & KS), are of AI/AN descent.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo, a software platform that facilitates management and analysis of qualitative data. The authors began by coding experiences of discrimination and noticed early in the coding process that much of the interview content centered on the complexity of negotiating AI/AN identity. Thus, initially guided by the research objectives of this study, the authors used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Clarke & Braun, 2017) to discover patterns in the data regarding AI/AN identity. A codebook was co-developed by three researchers (authors of this manuscript NM, AP, RB) through an iterative approach, beginning first with open coding, where sentences or paragraphs were examined and a descriptive label was attached to them (Braun & Clarke, 2012; Clarke & Braun, 2017). The team iterated and restructured the codebook as new findings emerged. Thematic analysis has shown to be an effective method for evaluating this type of qualitative data (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 1990). The team’s inter-rater reliability (a measure of consistency used to evaluate the extent to which different researchers agree in their assessment decisions) was 0.77, an acceptable level of reliability (McHugh, 2012). The intercoder reliability was conducted with NVivo using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The three researchers who had developed the codebook were joined by a fourth colleague (author in this manuscript PH), and all four coded the interviews and continued to meet as a team to discuss and summarize learnings within and across themes. To address coding disagreements, coders met and discussed code ambiguity which was helpful for understanding codes and refining codes. These discussions and resulting team decisions were reflected in changes to the coding rules document.

Due to small sample sizes (n=5) for each of the 4 profiles (protected, resilient, vulnerable, and at-risk), we conducted deeper data analysis by aggregating data based on outcomes to increase sample size comparison groups. Thus, we combined the protected and resilient profiles given that both reported good mental health and low problematic alcohol and other drug use, and we combined the at-risk and vulnerable profiles given both reported poor mental health and greater problematic alcohol and other drug use.

Results

Quantitative Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of our population are presented in Table 2 and are consistent with our overall sample for the study (D’Amico et al., 2023). Participants were mostly (85%) female; 55% identified as heterosexual/straight, and 45% identified as sexual or gender minority. We did not find significant differences on discrimination and MEIM scores for the at risk/vulnerable profiles and resilient/protected profiles (t18=0.49, p=0.63 and t18=−0.15, p=0.88, respectively).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics (n=20)

| All | At-Risk/Vulnerable | Protected/Resilient | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 18 | 10% | 0% | 20% |

| 19 | 15% | 10% | 20% |

| 20 | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| 21 | 15% | 20% | 10% |

| 22 | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| 23 | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| 24 | 15% | 30% | 0% |

| 25 | 15% | 10% | 20% |

|

| |||

| Sex at Birth | |||

| Male | 15% | 0% | 30% |

| Female | 85% | 100% | 70% |

| Intersex/other | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Man | 15% | 0% | 30% |

| Woman | 80% | 90% | 70% |

| Gender fluid | 5% | 10% | 0% |

| Something else | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Prefer not to say | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Straight/heterosexual | 55% | 40% | 70% |

| Gay | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Lesbian | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Bisexual | 20% | 30% | 10% |

| Questioning | 10% | 20% | 0% |

| Asexual | 5% | 0% | 10% |

| Something else | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Prefer not to say | 10% | 10% | 10% |

|

| |||

| % of Life in Urban Areas | |||

| 75 – 100% | 85% | 90% | 80% |

| 50 – 74% | 5% | 10% | 0% |

| 25 – 49% | 5% | 0% | 20% |

| 0 – 24% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||

| % of Life in Tribal Lands | |||

| 75 – 100% | 10% | 0% | 28.6% |

| 50 – 74% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 25 – 49% | 10% | 12.5% | 14.3% |

| 0 – 24% | 80% | 87.5% | 57.1% |

|

| |||

| Discrimination experiences M(SD)Range | 5.40 (3.55) 0 – 11 |

5.80 (3.33) 0 – 11 |

5.0 (3.89) 0 – 11 |

|

| |||

| Ethnic Identity (MEIM) M(SD)Range | 4.28 (0.58) 1 – 5 |

4.26 (.42) 1 – 5 |

4.30 (0.73) 1 – 5 |

Qualitative Results

We identified four themes from the qualitative interviews: a) being an urban AI/AN emerging adult means recognizing that one’s identity is multifaceted; b) a multifaceted identity comes with tension of living in multiple worlds; c) the trajectory of one’s identity grows over time to a deeper desire to connect with Native American culture; and d) understanding one’s Native American background affects one’s professional trajectory (Table 3). Within each theme, there were varied perspectives depending on an individual’s experiences and whether their profile was in the at-risk and vulnerable group or resilient and protected group.

Table 3.

Additional supporting quotes for each theme

| Theme 1: Being an urban AI/AN emerging adult means recognizing that one’s identity is multifaceted. | |

|---|---|

| At risk and vulnerable | Resilient and protected |

| Like we know we’re Native American but it’s like we’re very—I guess, for lack of a better word, like whitewashed, I guess. Like we don’t really know like much of the culture, but we have like quilts and stuff that are like—and a lot of turquoise. And I know about land that my family has in [state name], and I know some of the reservation stuff but a lot of the traditions, unfortunately, have gotten lost so that kind of makes me sad. – Female 20yr old |

I think more internal feelings when I visit family that are still on tribal lands or reservations out there, it’s just a feeling that “Oh, you’re not Indian enough because we’re still here. We’re farmers, we’re ranchers, we know how to ride horses, we do this every day, and you live in the city.” It’s somewhat of that mentality at times. I don’t think they mean to be malice or hateful, it’s just maybe they see that the problems that they’re facing where they are, the people that went to the cities or urban, I guess, is a copout, a way to forget it and that they’re forgetting their own heritage, and more of like a European-centric way. – Female 22yr old |

| Well, for a long time I had a hard time accepting, I guess, my culture, ‘cause being urban, I was always surrounded by a lot of white people and some Mexican people in my classes, so I was never really around my own culture for a while unless I went back up north during the summertime…But yeah, I guess in a way I kind of resented it for a while—I was just more so identified with my Mexican friends, since no one really would think I was Native American. – Female 19yr old |

My dad’s side, that’s where I get my Native American heritage from. Now that I’ve had more of a curiosity about learning [my Native Culture] I’ve had conversations with my dad about our traditional foods or any of our traditions and what is a part of our culture, like our tribe. But I always grew up knowing I was Native. That was always told to me and to be proud of it, and I am. But yeah, it’s definitely hard sometimes just because I don’t know my own tribe. Now that I have more questions about it, my dad has been explaining more. I feel better about it. – Female 19yr old |

| Theme 2: A multifaceted identity comes with tension of being from multiple worlds. | |

| At risk and vulnerable | Resilient and protected |

| I have to do a lot of work and kind of try and navigate these really strange, unknown waters which also make me feel like I’m Native enough to be discriminated against, but then sometimes you feel not Native enough to actually engage in your customs, and your traditions, and to even sometimes claim your tribe. So, it’s like this really strange line that I feel like I’m skirting, where some days I feel Native enough and then other days, I don’t. – Female 24yr old |

I mean, growing almost everywhere you look you’ll find something with Hispanic, Latino culture on it, and that is what allowed me to sort of just mix in with the rest of the crowd. And so I guess that is what acted as a buffer for me personally, because I mean at home I knew I was Native. But outside the house, it was almost never acknowledged, even when we went over Native tribes. And so that just added to me being able to just sort of buffer away or hide my own personal identity and just hide behind my second identity, behind my Latino side. – Male 18yr old |

| It does affect you no matter what, because it’s like okay, just because I didn’t grow up on the reservation, you think less of me, almost? Like it was kind of hurtful in a way because…just because I didn’t get the chance to grow up on my reservation doesn’t mean that I didn’t want that experience or anything like that. So, it was just kind of hurtful in that way, and I felt like I had to try to prove myself even more. And then I was like no, I’m trying to be more involved and you know, like be there for the community even more and try to show myself like, hey, I’m doing this, this, and that to prove myself that I really love being Native American and love this heritage that I have. When in reality, I shouldn’t have to prove myself just because I didn’t grow up on the reservation. – Female 23yr old |

I’m mixed race, so sometimes I have a hard time just identifying with any of my races or feeling like I belong to any group. But living [at the reservation] really got me in touch with my Native heritage. And even though it wasn’t my own tribe, I still got to learn different customs and I grew up feeling like I was needed and like I belonged in that community…I just felt accepted. – Female 19yr old |

| Theme 3: The trajectory of one’s identity grows over time to a deeper desire to connect with their AI/AN culture. | |

| At risk and vulnerable | Resilient and protected |

| My dad used to teach me how to bead and stuff or tan deer hide. So, learning about that, that was more like [tribal name] type culture, ‘cause al his friends were, like, [tribal name] and stuff. But I don’t know, that was really nice, especially to have a sense of kind of spirituality at a younger age. And then also when I moved onto my reservation now, it’s learning about my tribe’s specific culture. Yeah, yeah, like dancing and beading and stuff. – Female 21yr old |

I really didn’t get to really know my culture, actually, a lot of my culture, until I went to college where I decided to major in human services, and I added Native American studies. Because at my college, it was really something I had a chance to learn about my culture, and I’m proud to say I took the [tribal name] 1 and 2 in college, too. – Female 25yr old |

| …that really began in college, in undergrad, learning more about my tribe and their customs and then starting to follow them more. Because my Native heritage, has always been…I’ve always been really proud of it. I just didn’t know much growing up because my mom also doesn’t know much about it. And so, when I became an adult, I started really trying to reconnect, and I’m still working on that. And now I bead weave and follow a lot of the traditional customs. So, it’s a really big part of my life, and I really enjoy taking part in a lot of the customs and traditions. And I try to wear a lot of traditional jewelry and things like that. I like to share my tribe’s story with people I meet. So, it is a big part of my life at the moment. – Female 24yr old |

Recently we sort of were trying to rekindle, I guess would be the appropriate word, that now we’re trying to regain that knowledge of our heritage and trying to find that connection to it so that we could all be closer again, not just be closer with each other, but also be closer to our heritage, to our roots. – Male 18yr old |

| So, I started kind of early on in my college career learning more about other tribes and how they’re different than mine and learning how they can all relate and the things that bring us together and also, the things that are different from us. And yeah, feeling disconnected from my traditional foods or my language and just realizing that that requires me to do extra work. That requires me to do research, that requires me to reach out to family members or elders or try my best to stay in the loop. Social media has been great in that aspect. My tribe has a Facebook page that they update all the time, and that’s how I get a lot of my news. So it just requires me to engage in a different way and I feel like if I wasn’t putting in that work, then I might not be so engaged or might not feel as connected. – Female 24yr old |

There was always vague hints of “Oh, yeah, we’re Native,” and I never really understood what that meant, especially ‘cause I was never in a Native environment, I was just in an urban environment, so I didn’t really fully grasp that concept. And it wasn’t till I was, like, 11 that I started kind of learning more about it and I started being more curious and asking my mom and asking my grandpa and stuff just more about, like, what the heck does that mean? And that’s kind of what kickstarted my journey into that. – Male 21yr old |

| Theme 4: Understanding that one’s Native American background affects one’s professional trajectory. | |

| At risk and vulnerable | Resilient and protected |

| So, I work at a college as a program coordinator, planning culturally relevant events and programs for the Native American undergrad and graduate students on our campus and to also educate the broader community on campus including non-Native students and staff, faculty, and expanding into the local community, as well. – Female 24yr old |

With my job—and this also goes back to that Catholic sense, I guess, that quote, if man does have dominion over the animals, then we have a responsibility. And same thing with the Native American heritage where we don’t own the earth, we’re just its helper—we guide it however we can, we nurture it, and then it provides back to us. So this, I guess, would be my way of giving back, either to the animals themselves through spay/neuters or even just caring for them and the people in the community who may not be able to afford those kind of things, or just—yeah. – Female 22yr old |

| I’m sociology major. So, I essentially want to be a therapist later on, but I want to help with social services, more particularly in the Native community. – Female 20yr old |

So actually, in particular my tribe, we have our water rights and so the river that goes through our tribe. So right now they’re trying to construct a dam, and so those plans right now, they’re still in the works and I have background in CAD, computer-aided designing, so I would like to get my degree and then eventually go back to my rez and be a part of that. Because yeah, they’re contracting people out and it’d be cool to have one of the tribal members be a part of that. – Female 25yr old |

| My mom actually—with her, she works at the clinic out here and she’s the one that’s kind of made me really want to be the nursing and stuff, go into it. So, I’ve definitely been wanting to do that and try to go on the reservation and then do one of the clinics there, because we have two clinics up here. So, I definitely want to be able to try—I’ve told my mom that my entire life, too, like no matter what I do when I grow up, I know I want to be involved with the Native community, no matter what. And she’s definitely on board with it. I’ve talked to the doctor there before and he’s actually paying for her schooling for her to go back to be a delivery nurse and everything, because she just has her certified nursing assistant right now and she wants to go get even more certifications and stuff. They’re actually trying to pay for it and trying to help her, put her through schooling and everything. So that definitely interests me and makes me want to try even harder to do that. – Female 23yr old |

I would say…I mean the reason I applied to the school I go to is because of their strong and vibrant Native American community and the respect and ties they have to the land that they’re on and the people who own that land. That was really the entire reason why I chose that school and that was incredibly important to me when choosing a more traditional higher education route; was to also have those cultural ties. So, I’m studying biomedical engineering and indigenous studies there. I’m the cultural programmer in the Native American House as well as the RA, and as far as goals go, I guess, for the future, right now I do a little bit in tribal health care and I’m hoping to progress on to work for the IHS and fully immerse myself in tribal health care, specifically in [tribal name] nations. – Female 20yr old |

Theme 1: Being an urban AI/AN emerging adult means recognizing that one’s identity is multifaceted.

As in our other work (Brown et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2023), these urban AI/AN emerging adults who do not reside on a reservation or tribal lands described their identity as being multifaceted, specifically defined as having multiple parts to one’s identity made up of their race(s), ethnicity, sexual orientation, language, religion, family, neighborhood, and physical and mental ability and the interplay of all those aspects. For all four different profiles – at-risk, vulnerable, resilient, and protected, – identity was important, but how they discussed their identity differed depending on their profile group. For example, participants in the resilient and protected profile focused more on ways in which they learned about their various racial and ethnic identities and the perceptions others may have about them.

My family’s Native, but I’m also triracial because I’m Black, Mexican, and Native American. My dad’s Black, and my mom’s Native and Mexican. When I was in high school, that’s when I started getting more familiar with my tribe. I started going to the drums, the meetings, because I wanted to learn more because I never got the opportunity when I was younger. In college…I went to the Black [program] I was curious about that. Then there is the…I forgot what the Mexican one was called. Then there was a Native club, as well. So, I went to all three because I was curious about all three.

– Male 19 year old, RESILIENT & PROTECTED

Another participant said,

“I just took it upon myself to kind of teach myself these things because even still to this day, my grandma acknowledges, kind of, the fact that we’re [tribal name] and every now and then she’ll tell me random things… now it’s kind of become like I kind of carry the torch now in my family as far as reclaiming that and I’ve been teaching my little cousin a bunch of stuff, like cultural things and even language. I signed up to be part of the [tribal name] class—I’m really grateful that they have that online.”

- Male 21 year old, RESILIENT & PROTECTED

More exemplary quotes reflecting this theme are presented in Table 3. Participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles also wanted to learn more about their racial and ethnic identity; however, they did not discuss specific ways that they attempted to do this. In addition, they discussed ways in which they sought to identify with the part of their identity that was considered to be safer based on the communities they were living in. For example, one 19-year-old female participant discussed how they live in a predominately Mexican community and thus chose to present as Mexican “because there’s a lot of [Native] stereotypes that I just didn’t want to be a part of, and I just felt more comfortable [being known as Mexican] and sticking with my friends as close as possible.” Another participant also spoke about how they needed to present themselves a certain way because of concerns of discrimination:

I touched on it earlier, but I do have privilege of being enrolled in my tribe and I also have privilege in that I’m also white and I’m also Mexican, so I have kind of an ambiguous presence. But I present as white, so I don’t face discrimination in regards to how I present or how I look. Besides, “What are you,” is a weird question to get.

– Female 24 year old, AT-RISK & VULNERABLE

Theme 2: A multifaceted identity comes with tension of being from multiple worlds.

Many participants struggled with a tension of identity (Norman & Chen, 2020; Parker et al., 2015; Wilton et al., 2013). Similar to our previous work with urban AI/AN young people (Brown et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2021) and other work with multiracial groups(Mihoko Doyle & Kao, 2007; Yampolsky et al., 2013) our multiracial participants discussed being confronted with a unique challenges that involved navigating intricate nuances of multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds. They discussed that they often found themselves caught in a web of competing identities, struggling to reconcile different cultural, social, and historical factors that shaped their experiences. This resulted in a deep sense of tension whereby they felt as if they were from many worlds, but were never fully accepted by any one world. As a result, they spoke about working harder to forge a sense of belonging and find their place in society.

Individuals in the resilient and protected profiles spoke more about how they had to put forth effort to resolve complexities of identity compared to participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles. For example, participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles talked about the tension and their inability to resolve it, which was often related to lacking social support in addressing the tension.

To be honest, I broke down a couple of times because I wanted to know why being a little different was such a bad thing. I wanted to know why not communicating in the normal sense was so bad to not even have somebody to play with or even spend time with. But my great-grandma was there, she said, “It’s okay. You’ve just got to keep learning, you just have to keep trying, but don’t lose the [tribal] language, don’t lose what you grew up with.” And after she passed, I said, “You know what? This is all BS. I’m not going to do this anymore. I’m done, I’m just going to keep learning English because that’s all everybody talks.” And then I kind of stopped talking [tribal language].

– Female 24 year old, AT-RISK & VULNERABLE

In contrast, participants in the resilient and protected profiles often reported trying to have a deeper understanding of all aspects of their racial and ethnic identity through learning a language, living at their reservation, engagement in Native American traditions, and even found code-switching (the practice of alternative between two or more languages, behavior, and appearance to fit into the dominant culture) to be a protective mechanism to address the tension they felt. In addition, participants in the resilient and protected profiles reported that they had social support, which helped them think through how to best deal with the tension of coming from multiple worlds.

There were times where I just wondered if I really fit anywhere, ‘cause I couldn’t find common ground with people. I thought “Am I not Native enough for the people at powwows?” I just couldn’t mesh with people as easy. Like, some of the adults welcomed me and were kind of like my friends, but with kids my own age, the other teenagers were like “You’re talking too colonized. You’re talking too much like a city girl. You don’t even know this way right.” I’d just be like “This is the normal way I talk.” My sister at one point, was telling me, “You can just fake it, you know—just fake the rez accent. They’d like you more” …Sometimes I felt that I was performing for one people and then I’ve got to switch over and perform for a different person.

– Female 18 year old, RESILIENT & PROTECTED

Theme 3. The trajectory of one’s identity grows over time to a deeper desire to connect with their AI/AN culture.

There were no differences between the profiles in this theme. Results revealed that with time, all of the urban AI/AN emerging adults in this sample sought ways to engage more with their AI/AN culture because they recognized the value of being part of their culture. Participants in all four profiles discussed ways in which they tried to involve themselves more in their traditions. For instance, one participant in the resilient/protective profiles stated,

Before I left for college and my cousin left for the Navy, we had sort of a mini powwow where we just all got together and just had a celebration using traditional practices, and it was just us, the family and, close friends, and this was just all of us together trying to connect to our heritage in a way that we haven’t done in a long time, and my aunt was a big driving force for that.

– Male 18 year old, RESILIENT & PROTECTED

Participants also discussed how connecting with the AI/AN community, tradition, and culture helped them cope with AI/AN historical loss and trauma and/or their own personal or family loss and trauma, such as losing connection with the AI/AN community or dealing with the trauma of being discriminated for being AI/AN. Approximately 40% of participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles and the resilient and protected profile discussed the need to engage more with their AI/AN community to resolve historical loss and trauma. However, more participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles (70%) reported trying to resolve personal/family history loss and trauma than the resilient and protected profiles (50%). This participant described the process of how they went about coping over time with discrimination and loss.

…people want to make comments about my hair or moccasins or just something that really shows that I’m Native American and they use that to attack me…at first it really put me down because a lot of things I would hear about Native American stereotypes, I just kind of assumed that “Oh, there’s not really much that I can do in life.” It just made me have a lot of low expectations of myself and I thought, like, “What’s the point in going to college? There’s hardly any Natives at my college” or “People think I can’t do it.” There was a lot of barriers that I would have to go over and they were too hard, and I just wanted to just stay in the, I guess, stereotype that people would label me as. [But now] I get really sensitive because of how long it took me to accept who I was. But I take a lot of pride in my culture now, whereas back then I wouldn’t have really minded. You know, where I would’ve just been like “Oh, well, you’re wrong, I’m Mexican.” Now I put myself out there confidently, that I’m Native American.

– Female 23 year old, AT-RISK &VULNERABLE

This participant discussed how when they moved closer to a reservation, it helped them better understand their identity and how to cope with historical trauma.

It means a lot, because when I was younger, I didn’t understand it. I was never really shown my traditional ways because I grew up way far away from my reservation. But [later on I lived] near a reservation so the [tribal name] ended up kind of showing me a couple of really nice things and they kind of took me under their wing through like a Native program. They showed me a lot of ways to cope with the generational trauma that’s kind of been bestowed upon all young Native Americans, and especially those who’ve been displaced and kind of tossed to the side. Because we do fall through a lot of the social services cracks, whether it be law enforcement, whether it be social services or just everyday health care.

– Female 23 year old, PROTECTED & RESILIENT

Theme 4. Understanding that one’s Native American background affects one’s professional trajectory.

Participants in all four profiles explained that the more they learned about their AI/AN history and culture, the more that knowledge propelled them to pursue professions where they saw that AI/AN people were not represented or to be part of professions in which they could leverage their identities to help others. One participant in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles talked about how they wanted to use their education for their community:

It [being bullied as a Native in STEM] makes me want to do more things in computer science and math, and it makes me want to like help more people, because I also have that finance background/economic background, and so it makes me want to do more for the community.

– Female 22 year old, AT-RISK &VULNERABLE

Another participant in the protected and resilient profiles discussed how their current job helps them try to improve things for other Native American people.

[In] a Native program in elementary through middle school…they showed me a lot of ways to cope with the generational trauma that’s kind of been bestowed upon all young Native Americans, … so I work in social services due to the impacts of lasting trauma that has really hit me and my family, especially like the generational trauma and things of that nature. Now I’m working in enhanced shelter. So, it’s really just trying to improve the system and all the cracks in the system, because I know that one person can’t fix the system, but if there’s a lot of people fixing the cracks in the system, we can make a difference.

– Female 23 year old, PROTECTED & RESILIENT

Discussion

The current study addresses a significant gap in the literature by providing an understanding of how urban AI/AN emerging adults discuss and interpret their identities holistically (including social, cultural, psychological, historical, and biological aspects) in the present day and exploring how they navigate their identity in various settings such as living on or off the reservation, pursuing education or entering the workforce. To better understand the role that factors such as discrimination, substance use, mental health and culture played, we categorized participants into four profiles (at-risk, vulnerable, resilient, and protected) and examined their thoughts on navigating their identity in an urban setting.

A Multifaceted Identity

Overall, findings highlight that urban AI/AN emerging adults have a multifaceted understanding of their identity, which encompasses various aspects of their racial and ethnic composition, tribal affiliation, cultural practices, and language. These aspects align with Markstrom’s model of Indigenous identity, which describes AI/AN ethnic identity as formed through the identification of ethnic-Indigenous identity, connection to kinship, or tribe, genealogy or ancestry, land or place, and involvement in traditional cultural practices and spirituality (Markstrom, 2011). The multifaceted understanding of identity among urban AI/AN emerging adults reflects the complex effects of historical and contemporary factors, which have necessitated the preservation and adaptation of tribal affiliation and cultural practices that have contributed to the resilience of AI/AN individuals over time(Brown et al., 2023; Markstrom, 2011; Oré et al., 2016). Although multifaceted identity is not novel, the intricate dimension of identity among AI/AN emerging adults diverges from what is commonly observed in the literature describing Black, Hispanic and Asian identity development (Antman, 2022; Jones & Rogers, 2022, 2023; Myrie et al., 2022; Schwartz et al., 2017; Unni et al., 2022). Current findings are novel in that they highlight the significance of the AI/AN holistic identity as encompassing connection to specific tribes, traditional foods, and cultural practices rooted within their tribe, as pivotal elements shaping their identity. Markstrom’s model of Indigenous identity underscores the significance of one’s tribe within the broader AI/AN culture for identity development(Markstrom, 2011); however, our results discern a heightened emphasis on this aspect shedding new light on how tribal identity takes on a more nuanced and central role in shaping the identity formation process of AI/AN emerging adults. Findings underscore the importance of acknowledging and respecting the complexity and richness of identity formation among urban AI/AN emerging adults, highlighting the need for future endeavors to be mindful of this complexity when working with this population.

The Tension of Competing Identities

One important theme that urban AI/AN emerging adults expressed was their experience of identity tension as a result of competing identities within a society that often expects them to conform to a single racial or cultural category. The tension of being multiracial/multicultural can have significant effects on identity formation of emerging adults as they must navigate the complexities of reconciling and integrating multiple racial identities into their self-concept (Cardwell et al., 2020; Gaither, 2015; Markstrom, 2011). Not resolving this tension can lead to unstable identity formation with an individual identifying with one of their racial/cultural groups over others or an individual maintaining multiple, separate identities within themselves (Mihoko Doyle & Kao, 2007; Yampolsky et al., 2013). The urban AI/AN emerging adults in this study emphasized the important process of exploration and negotiation as they sought to find a sense of belonging and acceptance within their various racial communities, while also grappling with the social and cultural expectation and stereotypes associated with each of their racial backgrounds. This conflict of identities has also been described as identity denial; managing two or more distinct identities in a monoracial society can be challenging, leading individuals to cope by denying one or some aspects of their identity(Jones & Rogers, 2023). However, this can result in internal tension. Research has shown that identity tension is associated with greater stress and slower cortisol recovery which can lead to depressive symptomatology, memory impairment, compromised immune function and development of chronic disease (Albuja, Gaither, et al., 2019; Caplin et al., 2021; Franco et al., 2021). This tension and its effects could potentially explain why many multiracial individuals exhibit greater risk of poor health behaviors and outcomes when compared to monoracial individuals (Iwai, 2019; Miller et al., 2019; Subica et al., 2017). Studies comparing non-urban and urban residents’ identity formation are limited, but findings indicate that individuals in non-urban settings experience lower levels of identity-related tension. In fact, individuals in non-urban settings often form stronger bonds with their community, leading to heightened feeling of membership and pride, which serve as a buffer against prejudice and discrimination (Belanche et al., 2021; Zhang, 2018). Findings therefore highlight the importance of programs and interventions that can assist urban AI/AN emerging adults to find ways to explore and link their multiple cultural/racial identities. For instance, these efforts can utilize theories like social identity complex theory, which explores varying degrees of overlap in individual’s identities, or the multiple self-aspect framework, which suggests that people’s identities consist of multiple roles that can be integrated or compartmentalized(Albuja, Sanchez, et al., 2019; McConnell, 2011; Roccas & Brewer, 2002).

AI/AN Future Career Trajectory Connected to Identity

Interviews also indicated that urban AI/AN emerging adults’ pursuit to connect with their cultural heritage was not only part of their identity exploration but was also a way to address the trauma and loss experienced by their community due to forcible removal from ancestral lands and other historical injustices. Many participants felt that by reconnecting with traditional practices, language, and spiritual beliefs, they could gain a sense of self, purpose and community that was disrupted by generations of trauma. Reconnecting with culture has been shown to build resilience, foster empowerment, decrease rates of substance use, and improve mental, physical, and emotional health (Brown et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2023; Dickerson et al., 2022; Freeman, 2017; Gidgup et al., 2022; Hatala et al., 2020). Connection with culture can also promote a sense of healing and reconciliation as individuals work to restore practices and values that have been suppressed or lost over time (Dennis & Minor, 2019; Freeman, 2017).

Participants also discussed the importance of adjusting their education and career trajectory so that they could contribute more to the AI/AN community. Findings align with recent literature emphasizing the critical role of cultural connection among Native American people in providing a sense of belonging and shaping education and career pathways of AI/AN individuals (Palimaru et al., 2023; Schweigman et al., 2011). Studies suggest that a strong cultural identity can enhance a sense of belonging and foster persistence, key factors in achieving success in education and the workforce (Chow-Garcia et al., 2022; McMahon et al., 2019). Our study provides additional evidence that identity exploration can encourage individuals to align their educational and career trajectories with a deeper cultural connection, fostering a sense of purpose and fulfillment as they contribute meaningfully to the AI/AN community.

Importance of Fostering Resiliency

Our study employed a sampling strategy centered on experiences of urban AI/AN emerging adults who were grouped into four distinct profiles. Although no differences were observed among the groups regarding their connection to AI/AN cultural heritage and how this connection influenced their pursuit of careers that benefit their community, there were notable differences in the way they discussed their identity. Specifically, resilient and protected individuals spoke more about specific efforts they made to explore their identities compared to those in the at-risk and vulnerable groups. Moreover, resilient and protected participants described receiving support as they worked to address identity tension by learning languages and participating in cultural activities, whereas at-risk and vulnerable participants often cited a lack of social support and inability to resolve identity tension. Furthermore, those in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles reported poorer mental health and greater AOD use compared to resilient and protected individuals. This is particularly significant because mental health and AOD use can greatly influence the process of identity formation during emerging adulthood as young adults experiencing mental health challenges and with greater AOD use may struggle with feelings of self-doubt, uncertainty, and confusion about their identities (Rodriguez & Smith, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2015; Wilson & Stock, 2019). They also may feel disconnected from their peers, families, and society, which can exacerbate their health and substance use symptoms (Rodriguez & Smith, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2015; Wilson & Stock, 2019).

Overall, findings highlight the importance of programming for urban AI/AN emerging adults that promotes well-being and fosters a sense of connection with their community as this may particularly help those in the at-risk and vulnerable groups move along the profile continuum (Figure 2) to increase protective factors and overall resilience. Such programming is also important given the challenges (e.g., discrimination, loneliness) that AI/AN people in urban areas have faced (Espey et al., 2014; Herne et al., 2014; Kunitz et al., 2014; Urban Indian Health Commission, 2007; Yuan et al., 2014). In fact, our previous work has shown that providing cultural resources and having cultural support from social networks can help decrease the chances that urban AI/AN adults and young people use substances (D’Amico et al., 2020; D’Amico et al., 2023). In addition, community based programs that integrate culture into their services have been shown to increase overall well-being among urban AI/AN families (Johnson et al., 2021).

It is important to note that participants in the at-risk and vulnerable profiles were all female whereas the protected and resilient profiles had a majority of 70% females, highlighting a potential gender disparity within these different profiles, although with the small sample we couldn’t examine whether this is statistically significant. One contributing factor could be that females are more likely than males to internalize emotions (from discrimination, geographical fragmentation & reduced connection), which results in poorer mental health and increased alcohol use – characteristics of at-risk and vulnerable individuals(Cauffman et al., 2007; Eaton et al., 2012; Ferraro & Nuriddin, 2006; Hare Duke, 2017). In addition, among the females categorized as at-risk and vulnerable, 50% identified as a sexual gender minority, whereas only 28% of females identified as a sexual gender minority in the protected and resilient profiles. This finding reinforces previous studies that have demonstrated higher rates of substance use and mental health issues among individuals who identify as sexual gender minorities (Dunbar, Siconolfi, Rodriguez, Seelam, Davis, Tucker, & D’Amico, 2022; Dunbar, Siconolfi, Rodriguez, Seelam, Davis, Tucker, & D’Amico, 2022) highlighting the need for services to address all aspects of identity (Wilson et al., 2021).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, findings come from a convenience sample of urban AI/AN emerging adults and therefore they may not be representative of the broader AI/AN population. Additionally, the small sample size precludes a deeper investigation of other factors such as sexual or gender minority identification that may contribute to the heterogeneity of the sample and its role on identify formation. Utilizing social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram for recruitment may also introduce bias by potentially overlooking individuals who have limited digital connectivity, particularly those in remote or underserved areas with restricted internet access. Nonetheless, this study made concerted efforts to mitigate these biases by recruiting from a wide array of locations, resulting in participants hailing from 37 different states across the nation. It is also important to note that we had mostly females in our study, which limited our ability for further gender analysis. However, current research with this age group typically has higher participation from females (Reed et al., 2022). Future research with larger samples is needed to address these limitations.

Conclusion and future directions

Despite limitations, this study represents a significant first step in understanding how urban AI/AN emerging adults discuss and interpret their identity. Results highlight the multifaceted nature of AI/AN identity among those living in urban areas, which can often create tensions for those who identify as multiracial/multicultural. Notably, results also reveal that those urban AI/AN emerging adults in the resilient and protected profiles experience identity formation differently compared to those who are at-risk and vulnerable. Resilient and protected individuals actively engage in discussions and openly share their thoughts, striving to find solutions to challenges often associated with being multiracial/multicultural. They demonstrated higher levels of confidence and comfort, which likely contribute to their reduced susceptibility to substance use and mental health issues. Additionally, interviews highlighted that they are more likely to develop stronger connection to their community and lead a more balanced and healthy life. Conversely, interviews with the at-risk and vulnerable individuals emphasized that these individuals are not discussing ways that they can learn about their culture, are often lacking support and guidance to navigate their identity and are more focused on trying to resolve personal/family history loss. Overall, findings underscore the importance of developing programs to support well-being and improve identity development through cultural connection for urban AI/AN emerging adults. Future work needs to explore why and how these profiles may emerge among urban AI/AN emerging adults living in urban areas and identify ways to increase protective factors and resilience during this important developmental period.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer Parker, Keisha McDonald, and Mel Borstad of the Survey Research Group for their help in recruiting participants. They thank their Elder Advisory Board for their continued input on the project and approval of this article. Note that authors Carrie L. Johnson, Kurt Schweigman, and Virginia Arvizu-Sanchez are members of our Elder Advisory Board.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL (Helping End Addiction Long-Term Initiative under award number UH3DA050235 (PIs D’Amico & Dickerson). This study was conducted as part of a Health Equity Supplement. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, its NIH HEAL Initiative, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the RAND Institutional Review Board and our Urban Intertribal Native American Review Board.

REFERENCES

- Adams DW (2020). Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. Revised and Expanded. University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmad Z, & Adkins DE (2021). Ethnicity and acculturation: Asian American substance use from early adolescence to mature adulthood. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(19), 4570–4596. [Google Scholar]

- Ai AL, Aisenberg E, Weiss SI, & Salazar D (2014). Racial/ethnic identity and subjective physical and mental health of Latino Americans: An asset within? American journal of community psychology, 53, 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuja AF, Gaither SE, Sanchez DT, Straka B, & Cipollina R (2019). Psychophysiological stress responses to bicultural and biracial identity denial. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1165–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Albuja AF, Sanchez DT, & Gaither SE (2019). Identity denied: Comparing American or White identity denial and psychological health outcomes among bicultural and biracial people. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(3), 416–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Sanchez M, Bautista T, & Cox R (2021). Social vulnerabilities for substance use: Stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Neuropharmacology, 188, 108518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antman F (2022). Multi-Dimensional Identities of the Hispanic Population in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Belanche D, Casaló LV, & Rubio MÁ (2021). Local place identity: A comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Branje S (2022). Adolescent identity development in context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje S, De Moor EL, Spitzer J, & Becht AI (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Dickerson DL, & D’Amico EJ (2016). Cultural identity among urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth: Implications for alcohol and drug use. Prevention Science, 17, 852–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Dickerson DL, Klein DJ, Agniel D, Johnson CL, & D’Amico EJ (2021). Identifying as American Indian/Alaska Native in urban areas: Implications for adolescent behavioral health and well-being. Youth & Society, 53(1), 54–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palimaru AI, Dickerson DL, Etz K, Kennedy DP, Hale B, Johnson CL, & D’Amico EJ (2023). Cultural Dynamics, Substance Use, and Resilience Among American Indian/Alaska Native Emerging Adults in Urban Areas. Adversity and resilience science, 4(1), 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, & Smith LR (1991). Measures of racial identity: An overview and a proposed framework. Journal of Black Psychology, 17(2), 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA, & Project ACQI (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of internal medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]